Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 116

August 18, 2015

Let's Bet on the West, by Bryan Caplan

I say Western civilization is a hardy weed. Contrary to most of its avowed friends, Western civilization keeps gaining market share - grotesque atavisms notwithstanding.

Still, the fact that the media inevitably paints a bleak picture doesn't prove that the picture isn't bleak. The best way to face such questions, to repeat myself repeatedly, is betting. Refine vague questions into testable propositions, publicly agree to odds and a time frame, then see what happens.

Consistent with my hardy weed position, I'm happy to bet that Western civilization will advance globally by any reasonable measure. But I'm hazy on what metrics plausibly count as "reasonable." Bleg: Name some reasonable measures of global Westernization. I'll ponder your suggestions, then propose betting terms open to anyone on Earth willing to prepay me.

HT: Inspired by the great Garett Jones.

(18 COMMENTS)

The truth is that Western civilization is taking over the globe. InDoesn't the news tell us differently, day after day? Sure, because the news trumpets the worst things that happened yesterday on a planet with seven billion people. Heeding the daily news slowly melts even the strongest statistical mind.

virtually any fair fight, it steadily triumphs. Why? Because, as fans

of Western civ ought to know, Western civ is better. Given a choice,

young people choose Western consumerism, gender norms, and

entertainment. Anti-Western governments from Beijing to Tehran know

this this to be true: Without draconian censorship and social

regulation, "Westoxification" will win.

Still, the fact that the media inevitably paints a bleak picture doesn't prove that the picture isn't bleak. The best way to face such questions, to repeat myself repeatedly, is betting. Refine vague questions into testable propositions, publicly agree to odds and a time frame, then see what happens.

Consistent with my hardy weed position, I'm happy to bet that Western civilization will advance globally by any reasonable measure. But I'm hazy on what metrics plausibly count as "reasonable." Bleg: Name some reasonable measures of global Westernization. I'll ponder your suggestions, then propose betting terms open to anyone on Earth willing to prepay me.

HT: Inspired by the great Garett Jones.

(18 COMMENTS)

Published on August 18, 2015 22:23

August 17, 2015

Separation and Dr. Pangloss, by Bryan Caplan

A widely-quoted bit from Louie CK:

Now imagine how we'd react if an economist said:

1. What's good for one side need not be good for both sides. There are mutual break-ups and mutual job separations, but plenty are one-sided.

2. The summed effect for both sides doesn't have to be good either. With zero transactions costs, we could at least say that the economic gain to the winner must exceed the economic loss to the loser. Otherwise, the loser would bribe the winner not to separate. But transactions costs aren't zero - and net economic effect is distinct from net hedonic effect.

3. A good effect for "both sides" doesn't have to be a good effect for society. Even if both parties are better off - or at least better off in sum - separation can be bad because outside parties lose even more than the gainers gain. For divorce, the obvious sufferers are the kids. Your parents' divorce won't ruin your life, but it's still usually sad for children to experience. The same goes on the job.

4. People make mistakes. One of the main motives for separation is the perception that you can do better. Since people overrate themselves, this perception is often wrong. And don't forget focusing illusion - the all-too-human tendency to overrate whatever's on our minds.

If you think these are strange points for a free-market economist to make, please read my short essay on the grave evil of unemployment. More generally: If you can admit that divorce is sad without favoring government programs to curtail divorce, you can admit that firing is sad without favoring government programs to curtail firing. Either way, the Panglossian take on separation - in the family or in the firm - is blind to obvious facts.

(3 COMMENTS)

Divorce is always good news. I know that sounds weird, but it's trueYou could dismiss this as mere clowning, but I suspect that many listeners find this an airtight argument for the optimality of divorce.

because no good marriage has ever ended in divorce ... That would be sad.

If two people were married and they... just had a

great thing and then they got divorced, that would be really sad. But

that has happened zero times.

Now imagine how we'd react if an economist said:

Firing is always good news. I know that sounds weird, but it's trueSounds awfully dogmatic, does it not? There's a kernel of truth in both statements, but both Panglossian claims have a long list of potential flaws. Namely:

because no good worker has ever gotten fired ... That would be sad.

If a firm employed a worker and they... just had a

great thing and then the worker got fired, that would be really sad. But

that has happened zero times.

1. What's good for one side need not be good for both sides. There are mutual break-ups and mutual job separations, but plenty are one-sided.

2. The summed effect for both sides doesn't have to be good either. With zero transactions costs, we could at least say that the economic gain to the winner must exceed the economic loss to the loser. Otherwise, the loser would bribe the winner not to separate. But transactions costs aren't zero - and net economic effect is distinct from net hedonic effect.

3. A good effect for "both sides" doesn't have to be a good effect for society. Even if both parties are better off - or at least better off in sum - separation can be bad because outside parties lose even more than the gainers gain. For divorce, the obvious sufferers are the kids. Your parents' divorce won't ruin your life, but it's still usually sad for children to experience. The same goes on the job.

4. People make mistakes. One of the main motives for separation is the perception that you can do better. Since people overrate themselves, this perception is often wrong. And don't forget focusing illusion - the all-too-human tendency to overrate whatever's on our minds.

If you think these are strange points for a free-market economist to make, please read my short essay on the grave evil of unemployment. More generally: If you can admit that divorce is sad without favoring government programs to curtail divorce, you can admit that firing is sad without favoring government programs to curtail firing. Either way, the Panglossian take on separation - in the family or in the firm - is blind to obvious facts.

(3 COMMENTS)

Published on August 17, 2015 22:16

August 16, 2015

Who Really Cares About the Poor?: A Socratic Dialogue, by Bryan Caplan

Glaucon: Can you believe all these rich jerks who refuse to help the poor?

Socrates: I'm puzzled, Glaucon. You're rich, but I've never seen you help the poor.

Glaucon: I gave five gold pieces this year. But I'm not talking about charity, Socrates. I'm talking about last night's vote in the Assembly.

Socrates: Sorry, I didn't attend. What did I miss?

Glaucon: And you call yourself a philosopher! Fine, I'll tell you. The democratic faction - to which I happen to belong - proposed a new law to give ten gold pieces a year to every poor Athenian.

Socrates: From the public treasury?

Glaucon: Yes, from the public treasury. Anyway, we democrats called a vote - and the aristocratic faction voted us down. How can they be so uncaring?

Socrates: Why do you assume the aristocrats voted No because they were uncaring? Did they say, "I'm voting No because I don't care about the poor"?

Glaucon: Of course not. No one admits such things.

Socrates: So, what objections did the aristocrats voice?

Glaucon: Oh, the usual. They said our meager program would turn poor and rich alike into lazy bums. The poor wouldn't want to work if they got free money, and the rich wouldn't want to work if they had to pay the taxes required to fund the program.

Socrates: Sounds overstated. Divide by ten, and they're right. Any other argument?

Glaucon: Yes. Many also insisted that, "It's my money." They earned it, so they shouldn't have to share it.

Socrates: And they're wrong?

Glaucon: Of course they're wrong! We're a community, we all depend on each other and we're all obliged to take care of each other. If they had an ounce of compassion for disadvantaged Athenians, they would have voted Yes.

Socrates: Then I have good news for you.

Glaucon: Good news? What in Greece are you talking about?

Socrates: The good news is that you - and your fellow democrats - can still fulfill your obligations despite the aristocrats' resistance.

Glaucon: What, revolution?

Socrates: No. Just tell me this: What is your annual income?

Glaucon: A rude question, Socrates.

Socrates: Is it? If I recall, your poverty law would have required everyone to tell the Assembly their income.

Glaucon: I seem to recall you claimed ignorance of our proposal. Very well. I make 1000 gold pieces a year.

Socrates: Glad to know you're prospering. And what do you need to avoid hunger and homelessness?

Glaucon: I've got three kids, so 100 gold pieces a year.

Socrates: Seems high, but let's run with it. You make 1000 gold pieces a year, but only need 100. That leaves 900 gold pieces a year.

Glaucon: I can do arithmetic, Socrates.

Socrates: Most rich men can. Here then is my advice: Give your extra 900 gold pieces to the poor. Urge your fellow democrats to do the same.

Glaucon: Charity?! Your cure for Athenian poverty is to impoverish me? Surely you jest.

Socrates: I know you can't personally cure poverty, Glaucon. But you can save a dozen poor families from their plight. And when you're done, you'll still live comfortably.

Glaucon: Why should I?

Socrates: Unlike the aristocratic faction, you care about the poor, do you not?

Glaucon: Absolutely.

Socrates: If you have the means to help people you care about, shouldn't you help them?

Glaucon: Sure, if it would do any good.

Socrates: It seems like your 900 gold pieces would do a great deal of good.

Glaucon: Wouldn't cure poverty.

Socrates: Granted, but so what? Imagine a father has ten children, but only enough food to keep one alive. If he cares about his children, what will he do?

Glaucon: [sigh] Pick one child and give him the food.

Socrates: Indeed. If you truly care for the Athenian poor, you will heed his example.

Glaucon: My poverty law would have helped vastly more than I ever could.

Socrates: Perhaps. But your path remains clear. Give your extra 900 gold pieces to the poor. Then explain your reasons to your fellow caring democrats.

Glaucon: Why should we be singled out for suffering?

Socrates: If you're as caring as you say, you'll suffer more if you keep your money.

Glaucon: Funny, I hadn't noticed I was suffering.

Socrates: Could a caring father eat a feast while his children starved?

Glaucon: [sigh] No.

Socrates: Why not?

Glaucon: Because every bite would remind him that people he cares about need it more.

Socrates: Indeed. By the way, I don't mind if we continue this conversation tomorrow.

Glaucon: Do you have someplace to be?

Socrates: No, but I thought you might want to run home and donate the 900 gold pieces. It's hard to talk philosophy when desperate people you care about await your assistance.

Glaucon: If you're going to mock me, go join your aristocratic friends and mock us at the next Assembly.

Socrates: They're not my friends. Democrats and aristocrats alike sin against philosophy.

Glaucon: Look, why should the aristocrats get to free ride? They should contribute to solve the problem of poverty just like everyone else.

Socrates: If they're as uncaring as you say, how are they "free riding"?

Glaucon: Don't they benefit from the knowledge that every Athenian has a decent standard of living?

Socrates: Caring people like you benefit from such knowledge, no doubt. But your heartless aristocratic opponents will take small comfort from this realization.

Glaucon: They may be aristocrats, but they're still human.

Socrates: Hmm, that's the first kind word you've ever had for them, so far as I recall. I concur. Aristocrats, like democrats, are not bereft of compassion.

Glaucon: Many even give to charity.

Socrates: According to my friend in the Bureau of Athenian Economic Statistics, aristocrats actually give a higher share of their income than democrats.

Glaucon: Well then! So they do care and they are free riding after all!

Socrates: Perhaps. But now I'm more puzzled than ever.

Glaucon: What is it now?

Socrates: When an aristocrat gives 100 gold pieces to the poor, what does it cost him?

Glaucon: 100 gold pieces.

Socrates: Right. When an aristocrat votes for a measure that raises his taxes by 100 gold pieces, what does that cost him?

Glaucon: 100 gold pieces, again.

Socrates: Does it? Was last night's proposal decided by a single vote?

Glaucon: No, the final tally was 555 to 450.

Socrates: So if one aristocrat had switched his vote, the final tally would have been 554 to 451?

Glaucon: Correct.

Socrates: And your measure still would have lost?

Glaucon: We are a democracy, Socrates. So yes.

Socrates: Then it's hard to see how an aristocrat saved any money by voting against your measure. Whether he voted Yes or No, his taxes stayed the same.

Glaucon: Your point being?

Socrates: Your opponents didn't vote No because they were "uncaring," because any one of them could have switched his vote without paying one copper piece extra.

Glaucon: Maybe they voted No because they foresaw a tiny probability of tipping the election.

Socrates: Perhaps. But what about all the No voters who donate to charity? Why would someone willing to hand the poor money out of his own pocket be so eager to guard against a small chance of paying extra taxes to help them?

Glaucon: Don't make me guess. Just tell me.

Socrates: Very well. The simplest explanation is that the aristocrats sincerely believe the reasons they stated. They're worried about disincentives - and they think that whoever earned his money deserves to keep it.

Glaucon: Bah. If they're so wonderful, they'd happily donate all their surplus riches to the poor, right?

Socrates: I don't remember discussing whether anyone was "wonderful." But yes, if they deeply cared about the poor, they would give away all their extra income.

Glaucon: But almost no one does that.

Socrates: Then almost no one deeply cares about the poor.

Glaucon: So your point is that democrats and aristocrats are equally bad?

Socrates: A question for another day. But at least on the issue we're discussing, my point is that you democrats are worse.

Glaucon: Worse? How could we possibly be worse than them?

Socrates: They live up to their stated principles. You don't live up to yours.

Glaucon: [huffs]

Socrates: The aristocrats say that people who earned their money deserve to keep it. That's perfectly consistent with voting against last night's proposal. And it's perfectly consistent with their failure to give away all the income they don't need.

Glaucon: And we democrats?

Socrates: You say we're obliged to care for all our fellow Athenians. That's arguably consistent with the way your side voted last night - though you really should look more closely into those disincentive effects. But your principle is inconsistent with your failure to give away all the income you don't need.

Glaucon: Nobody's perfect.

Socrates: Indeed. But please remind me, how much did you actually give to charity this year?

Glaucon: Five gold pieces.

Socrates: Then your deviation from your stated principle is extreme. You should have given 900. You only did 5/900ths of your duty, leaving 895/900ths undone.

Glaucon: Funny, I don't feel like an awful person.

Socrates: I've never thought so. But if your moral principles are correct, an awful person is what you are.

Glaucon: Why do I keep arguing with you, Socrates? There's no need to be rude.

Socrates: I've tried to make my points with utmost civility. All I'm saying is this: Your principles and your behavior can't both be right. Change one, and I'll include the aristocrat of your choice to my next dialogue.

And don't worry, I'll treat him with utmost civility.

(3 COMMENTS)

Socrates: I'm puzzled, Glaucon. You're rich, but I've never seen you help the poor.

Glaucon: I gave five gold pieces this year. But I'm not talking about charity, Socrates. I'm talking about last night's vote in the Assembly.

Socrates: Sorry, I didn't attend. What did I miss?

Glaucon: And you call yourself a philosopher! Fine, I'll tell you. The democratic faction - to which I happen to belong - proposed a new law to give ten gold pieces a year to every poor Athenian.

Socrates: From the public treasury?

Glaucon: Yes, from the public treasury. Anyway, we democrats called a vote - and the aristocratic faction voted us down. How can they be so uncaring?

Socrates: Why do you assume the aristocrats voted No because they were uncaring? Did they say, "I'm voting No because I don't care about the poor"?

Glaucon: Of course not. No one admits such things.

Socrates: So, what objections did the aristocrats voice?

Glaucon: Oh, the usual. They said our meager program would turn poor and rich alike into lazy bums. The poor wouldn't want to work if they got free money, and the rich wouldn't want to work if they had to pay the taxes required to fund the program.

Socrates: Sounds overstated. Divide by ten, and they're right. Any other argument?

Glaucon: Yes. Many also insisted that, "It's my money." They earned it, so they shouldn't have to share it.

Socrates: And they're wrong?

Glaucon: Of course they're wrong! We're a community, we all depend on each other and we're all obliged to take care of each other. If they had an ounce of compassion for disadvantaged Athenians, they would have voted Yes.

Socrates: Then I have good news for you.

Glaucon: Good news? What in Greece are you talking about?

Socrates: The good news is that you - and your fellow democrats - can still fulfill your obligations despite the aristocrats' resistance.

Glaucon: What, revolution?

Socrates: No. Just tell me this: What is your annual income?

Glaucon: A rude question, Socrates.

Socrates: Is it? If I recall, your poverty law would have required everyone to tell the Assembly their income.

Glaucon: I seem to recall you claimed ignorance of our proposal. Very well. I make 1000 gold pieces a year.

Socrates: Glad to know you're prospering. And what do you need to avoid hunger and homelessness?

Glaucon: I've got three kids, so 100 gold pieces a year.

Socrates: Seems high, but let's run with it. You make 1000 gold pieces a year, but only need 100. That leaves 900 gold pieces a year.

Glaucon: I can do arithmetic, Socrates.

Socrates: Most rich men can. Here then is my advice: Give your extra 900 gold pieces to the poor. Urge your fellow democrats to do the same.

Glaucon: Charity?! Your cure for Athenian poverty is to impoverish me? Surely you jest.

Socrates: I know you can't personally cure poverty, Glaucon. But you can save a dozen poor families from their plight. And when you're done, you'll still live comfortably.

Glaucon: Why should I?

Socrates: Unlike the aristocratic faction, you care about the poor, do you not?

Glaucon: Absolutely.

Socrates: If you have the means to help people you care about, shouldn't you help them?

Glaucon: Sure, if it would do any good.

Socrates: It seems like your 900 gold pieces would do a great deal of good.

Glaucon: Wouldn't cure poverty.

Socrates: Granted, but so what? Imagine a father has ten children, but only enough food to keep one alive. If he cares about his children, what will he do?

Glaucon: [sigh] Pick one child and give him the food.

Socrates: Indeed. If you truly care for the Athenian poor, you will heed his example.

Glaucon: My poverty law would have helped vastly more than I ever could.

Socrates: Perhaps. But your path remains clear. Give your extra 900 gold pieces to the poor. Then explain your reasons to your fellow caring democrats.

Glaucon: Why should we be singled out for suffering?

Socrates: If you're as caring as you say, you'll suffer more if you keep your money.

Glaucon: Funny, I hadn't noticed I was suffering.

Socrates: Could a caring father eat a feast while his children starved?

Glaucon: [sigh] No.

Socrates: Why not?

Glaucon: Because every bite would remind him that people he cares about need it more.

Socrates: Indeed. By the way, I don't mind if we continue this conversation tomorrow.

Glaucon: Do you have someplace to be?

Socrates: No, but I thought you might want to run home and donate the 900 gold pieces. It's hard to talk philosophy when desperate people you care about await your assistance.

Glaucon: If you're going to mock me, go join your aristocratic friends and mock us at the next Assembly.

Socrates: They're not my friends. Democrats and aristocrats alike sin against philosophy.

Glaucon: Look, why should the aristocrats get to free ride? They should contribute to solve the problem of poverty just like everyone else.

Socrates: If they're as uncaring as you say, how are they "free riding"?

Glaucon: Don't they benefit from the knowledge that every Athenian has a decent standard of living?

Socrates: Caring people like you benefit from such knowledge, no doubt. But your heartless aristocratic opponents will take small comfort from this realization.

Glaucon: They may be aristocrats, but they're still human.

Socrates: Hmm, that's the first kind word you've ever had for them, so far as I recall. I concur. Aristocrats, like democrats, are not bereft of compassion.

Glaucon: Many even give to charity.

Socrates: According to my friend in the Bureau of Athenian Economic Statistics, aristocrats actually give a higher share of their income than democrats.

Glaucon: Well then! So they do care and they are free riding after all!

Socrates: Perhaps. But now I'm more puzzled than ever.

Glaucon: What is it now?

Socrates: When an aristocrat gives 100 gold pieces to the poor, what does it cost him?

Glaucon: 100 gold pieces.

Socrates: Right. When an aristocrat votes for a measure that raises his taxes by 100 gold pieces, what does that cost him?

Glaucon: 100 gold pieces, again.

Socrates: Does it? Was last night's proposal decided by a single vote?

Glaucon: No, the final tally was 555 to 450.

Socrates: So if one aristocrat had switched his vote, the final tally would have been 554 to 451?

Glaucon: Correct.

Socrates: And your measure still would have lost?

Glaucon: We are a democracy, Socrates. So yes.

Socrates: Then it's hard to see how an aristocrat saved any money by voting against your measure. Whether he voted Yes or No, his taxes stayed the same.

Glaucon: Your point being?

Socrates: Your opponents didn't vote No because they were "uncaring," because any one of them could have switched his vote without paying one copper piece extra.

Glaucon: Maybe they voted No because they foresaw a tiny probability of tipping the election.

Socrates: Perhaps. But what about all the No voters who donate to charity? Why would someone willing to hand the poor money out of his own pocket be so eager to guard against a small chance of paying extra taxes to help them?

Glaucon: Don't make me guess. Just tell me.

Socrates: Very well. The simplest explanation is that the aristocrats sincerely believe the reasons they stated. They're worried about disincentives - and they think that whoever earned his money deserves to keep it.

Glaucon: Bah. If they're so wonderful, they'd happily donate all their surplus riches to the poor, right?

Socrates: I don't remember discussing whether anyone was "wonderful." But yes, if they deeply cared about the poor, they would give away all their extra income.

Glaucon: But almost no one does that.

Socrates: Then almost no one deeply cares about the poor.

Glaucon: So your point is that democrats and aristocrats are equally bad?

Socrates: A question for another day. But at least on the issue we're discussing, my point is that you democrats are worse.

Glaucon: Worse? How could we possibly be worse than them?

Socrates: They live up to their stated principles. You don't live up to yours.

Glaucon: [huffs]

Socrates: The aristocrats say that people who earned their money deserve to keep it. That's perfectly consistent with voting against last night's proposal. And it's perfectly consistent with their failure to give away all the income they don't need.

Glaucon: And we democrats?

Socrates: You say we're obliged to care for all our fellow Athenians. That's arguably consistent with the way your side voted last night - though you really should look more closely into those disincentive effects. But your principle is inconsistent with your failure to give away all the income you don't need.

Glaucon: Nobody's perfect.

Socrates: Indeed. But please remind me, how much did you actually give to charity this year?

Glaucon: Five gold pieces.

Socrates: Then your deviation from your stated principle is extreme. You should have given 900. You only did 5/900ths of your duty, leaving 895/900ths undone.

Glaucon: Funny, I don't feel like an awful person.

Socrates: I've never thought so. But if your moral principles are correct, an awful person is what you are.

Glaucon: Why do I keep arguing with you, Socrates? There's no need to be rude.

Socrates: I've tried to make my points with utmost civility. All I'm saying is this: Your principles and your behavior can't both be right. Change one, and I'll include the aristocrat of your choice to my next dialogue.

And don't worry, I'll treat him with utmost civility.

(3 COMMENTS)

Published on August 16, 2015 22:09

August 12, 2015

Treatment: A Little Cost-Benefit Analysis is a Dangerous Thing, by Bryan Caplan

Suppose you discover that a medical procedure genuinely reduces your risk of dying this year. When you look further, however, you learn that your risk of dying only falls from 10-in-1000 to 9-in-1000. Here are three reactions in order of sophistication.

1. Sheer innumeracy. Many non-economists will say, "Eh, that's virtually the same. Why bother?"

2. Elementary cost-benefit analysis. Many economically literate people will rebuke to the innumerate with, "Dying is really bad. Like, $10 million bad. Multiply that $10M by 1-in-1000 - the change in the probability of dying - and you've got an expected benefit of $10,000. As long as the treatment costs less than $10,000, do it!"

3. Sophisticated cost-benefit analysis. Thoughtful analysts will realize this isn't just about quantity of life versus dollar cost. Quality of life is also key. Most medical treatments are unpleasant; many are downright ghastly. Obvious issues include: How much pain does the treatment impose? How much time does it take? Will it prevent me from doing my favorite activities? Limit my diet? Once you monetize quality of life effects, they can readily swamp modest quantity of life effects. Example: What would someone have to pay you to endure one day of extreme pain? $1000? Then even with free medical care, the preceding treatment is a bad deal if it imposes 11 days of extreme pain. And if the side effect lasts for the rest of your life, even a modest daily cost justifies inaction.

Observation: In most medical debates, elementary cost-benefit analysis contends against innumeracy. Innumeracy ends up looking very stupid. But this doesn't make the innumerate conclusion stupid. Paying a large amount of money for a little extra quantity of life makes sense as long as quality of life stays the same. Paying a large amount of money for a small increase in quantity of life paired with even a small decrease in quality of life is pretty foolish. A little cost-benefit analysis is a dangerous thing.

(16 COMMENTS)

1. Sheer innumeracy. Many non-economists will say, "Eh, that's virtually the same. Why bother?"

2. Elementary cost-benefit analysis. Many economically literate people will rebuke to the innumerate with, "Dying is really bad. Like, $10 million bad. Multiply that $10M by 1-in-1000 - the change in the probability of dying - and you've got an expected benefit of $10,000. As long as the treatment costs less than $10,000, do it!"

3. Sophisticated cost-benefit analysis. Thoughtful analysts will realize this isn't just about quantity of life versus dollar cost. Quality of life is also key. Most medical treatments are unpleasant; many are downright ghastly. Obvious issues include: How much pain does the treatment impose? How much time does it take? Will it prevent me from doing my favorite activities? Limit my diet? Once you monetize quality of life effects, they can readily swamp modest quantity of life effects. Example: What would someone have to pay you to endure one day of extreme pain? $1000? Then even with free medical care, the preceding treatment is a bad deal if it imposes 11 days of extreme pain. And if the side effect lasts for the rest of your life, even a modest daily cost justifies inaction.

Observation: In most medical debates, elementary cost-benefit analysis contends against innumeracy. Innumeracy ends up looking very stupid. But this doesn't make the innumerate conclusion stupid. Paying a large amount of money for a little extra quantity of life makes sense as long as quality of life stays the same. Paying a large amount of money for a small increase in quantity of life paired with even a small decrease in quality of life is pretty foolish. A little cost-benefit analysis is a dangerous thing.

(16 COMMENTS)

Published on August 12, 2015 22:01

August 11, 2015

Is Breast Cancer Screening Worthless? The Fact Box Speaks, by Bryan Caplan

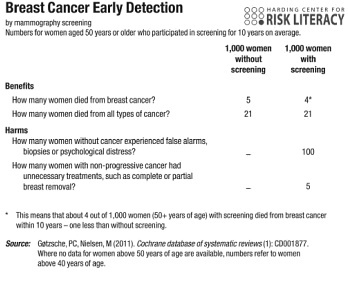

Gigerenzer's Risk Savvy also presents transparent statistical evidence against routine mammograms. The presentation slightly changes, relying on a "fact box" rather than an icon box. But the idea remains the same: Clearly summarize outcome frequencies from women randomly assigned to either screening or no screening. Results:

At first glance, screenings save the life of one women in a thousand. On closer look, however, screenings only alter the kind of cancer that kills you, not overall cancer mortality. Whether they're screened or not, 21-in-1000 women died of cancer within ten years.

Details on the benefits:

(11 COMMENTS)

At first glance, screenings save the life of one women in a thousand. On closer look, however, screenings only alter the kind of cancer that kills you, not overall cancer mortality. Whether they're screened or not, 21-in-1000 women died of cancer within ten years.

Details on the benefits:

First, is there evidence that mammography screening reduces my chance of dying from breast cancer? The answer is yes. Out of every one thousand women who did not participate in screening, about five died of breast cancer, while this number was four for those who participated. In statistical terms that is an absolute risk reduction of one in one thousand. But if you find this information in a newspaper or brochure, it is almost always presented as a "20 percent risk reduction" or more.Details on the costs:

Second, is there evidence that mammography screening reduces my chance of dying from any kind of cancer, including breast cancer? The answer is no...

In plain words, there is no evidence that mammography saves lives. One less women in a thousand dies with the diagnosis breast cancer, but one more dies with another cancer diagnosis. Some women die with two or three different cancers, where it's not always clear which of these caused death.

First, women who do not have breast cancer can experience false alarms and unnecessary biopsies. This happened to about a hundred out of every thousand women who participated in screening... Second, women who do have breast cancer, but a nonprogressive or slowly growing form that they would never have noticed during their lifetimes, often undergo lumpectomy, mastectomy, toxic chemotherapy, or other interventions that have no benefit for them...Furthermore, since diagnosis typically leads to treatment, the fact that more-diagnosed women don't live longer is striking evidence that breast cancer treatments are, on average, ineffective. Hansonian medical skepticism may be overstated, but it is firmly grounded in fact.

(11 COMMENTS)

Published on August 11, 2015 22:07

August 10, 2015

Is Prostate Screening Worthless? The Icon Box Speaks, by Bryan Caplan

Gerd Gigerenzer's

Risk Savvy

is strikingly consistent with Hansonian medical skepticism. One striking example: his cost-benefit analysis of prostate screening. His key analytical tool is the icon box.

That's right. Statistically speaking, prostate cancer screening is worthless. Over the course of ten years, 1-in-100 men dies of prostate cancer regardless of screening. 20-in-100 die for any reason, regardless of screening. The only difference: 2-in-100 screened men - and screened men alone - endure hellish treatments, and another 18-in-100 endure milder torments and a false alarm.

Details on the illusory benefits:

When faced with scary medical problems, retreating to "I have to trust my doctor" is very tempting. What Gigerenzer shows, though, is that this trust is misplaced. Relying on doctors is unreliable. Trust transparent statistics instead.

(21 COMMENTS)

An icon box brings transparency into health care. It can be used to communicate facts about screening, drugs, or any other treatment. The alternative treatments are placed directly next to each other in columns and both benefits and harms are shown. Most important, no misleading statistics such as survival rates and relative risks are allowed to enter the box. All information is given in plain frequencies.Here's what you get if you construct an icon box for prostate screening based on "all medical studies using the best evidence from randomized trials." Each dot represents 1% of men 50 years and older over the course of ten years.

That's right. Statistically speaking, prostate cancer screening is worthless. Over the course of ten years, 1-in-100 men dies of prostate cancer regardless of screening. 20-in-100 die for any reason, regardless of screening. The only difference: 2-in-100 screened men - and screened men alone - endure hellish treatments, and another 18-in-100 endure milder torments and a false alarm.

Details on the illusory benefits:

[I]s there any evidence that early detection reduces the number of deaths from prostate cancer? The answer is no: There was no difference... [I]s there evidence that detecting cancer at an early stage reduces the total number of deaths from any cause whatsoever? Again no.Details on the grotesque costs:

There are two kinds of harms: for men without prostate cancer and for men with prostate cancer that is nonprogressive. When a man without cancer repeatedly has a high PSA level, doctors typically do a biopsy. But unlike a mammogram, a PSA test does not tell the doctor where to inject the needle. As a result, men are often subjected to the nightmare of multiple needle biopsies in search of a tumor that is not there in the first place. These false alarms occur frequently because many men without cancer have high PSA levels...Gigerenzer actually understates his case. Since 1-in-100 die of prostate cancer either way, we have to conclude that either (a) positive biopsies don't lead to treatment, or (b) the treatments do not, on average, work. Since (a) is clearly wrong, (b) is the logical inference. If you have terminal prostate cancer, modern medicine won't help you. It will however still hurt you during treatment, and quite possibly make you incontinent and/or impotent for your remaining years.

Men with nonprogressive prostate cancer suffer even more. If a biopsy showed any signs of cancer, most were pushed into unnecessary treatments, such as prostatectomy and radiation therapy... Between 20 and 70 percent of men who had no problems before treatment ended up incontinent or impotent for the rest of their lives.

When faced with scary medical problems, retreating to "I have to trust my doctor" is very tempting. What Gigerenzer shows, though, is that this trust is misplaced. Relying on doctors is unreliable. Trust transparent statistics instead.

(21 COMMENTS)

Published on August 10, 2015 22:26

August 9, 2015

A Waste of Paper?, by Bryan Caplan

Last week I walked the stacks of GMU's Fenwick Library with my elder sons. Their presence was clarifying. As we three perused the books, my main emotion was embarrassment. I'm an academic. A university library is supposed to be a warehouse of great thoughts. But the vast majority of the books seemed literally indefensible. Lame topics, vague theses, and godawful writing abounded. Titles withheld to protect the guilty.

The indefensibility was clearest for the humanities, where many books seemed doubly pointless: A History of Literary Criticism of a Minor Genre. But most of the social science was in the same ballpark. 90% of the books screamed, "If writing stuff like this wasn't a ticket to tenure, no one would write it."

You could dismiss me as a philistine, but that seems unfair. On any conventional test of cultural literacy, I'd at least make the 95th percentile. I have very broad interests. I've heavily explored economics, philosophy, psychology, political science, history, sociology, education, genetics, evolution, and the history of music and film. The fact that most of the books failed to minimally pique even my interest reflects poorly them.

Could the problem be my lack of expertise? Perhaps if I were an expert on Emily Dickinson, I'd see the value in most of the volumes written about her. But I doubt it. The obvious test: Do I see greater value in the median work in the areas where I have attained expertise? Only to a slight degree. And that small effect is readily explained by selection bias: You should expect me to be more favorable toward academic literatures I chose to carefully explore.

My question for anyone who's wandered the stacks of a university library: Do you really think that most of the books were worth writing? What fraction of the collection literally isn't worth the paper it's printed on?

Bonus question: What lessons do you draw about the social value of academia?

(3 COMMENTS)

The indefensibility was clearest for the humanities, where many books seemed doubly pointless: A History of Literary Criticism of a Minor Genre. But most of the social science was in the same ballpark. 90% of the books screamed, "If writing stuff like this wasn't a ticket to tenure, no one would write it."

You could dismiss me as a philistine, but that seems unfair. On any conventional test of cultural literacy, I'd at least make the 95th percentile. I have very broad interests. I've heavily explored economics, philosophy, psychology, political science, history, sociology, education, genetics, evolution, and the history of music and film. The fact that most of the books failed to minimally pique even my interest reflects poorly them.

Could the problem be my lack of expertise? Perhaps if I were an expert on Emily Dickinson, I'd see the value in most of the volumes written about her. But I doubt it. The obvious test: Do I see greater value in the median work in the areas where I have attained expertise? Only to a slight degree. And that small effect is readily explained by selection bias: You should expect me to be more favorable toward academic literatures I chose to carefully explore.

My question for anyone who's wandered the stacks of a university library: Do you really think that most of the books were worth writing? What fraction of the collection literally isn't worth the paper it's printed on?

Bonus question: What lessons do you draw about the social value of academia?

(3 COMMENTS)

Published on August 09, 2015 22:05

August 6, 2015

The Unfair Labor Training Act, by Bryan Caplan

John Bishop's "What We Know About Employer-Provided Training" alerted me to the existence of some obscure but plausibly very harmful labor regulations. Suppose your employer provides free job training every Saturday. Compared to regular schooling, this is a great deal. The firm gives you a "full scholarship"; you pay only the opportunity cost of your time. But this great deal is normally forbidden. Bishop:

(7 COMMENTS)

Labor Department regulations implementing the Fair Labor Standards Act make it very difficult for firms to ask workers to contribute towards the cost of their training by taking training classes during unpaid time. They specify that:The piece is from 1996, but as far as I can tell these regulations remain the law of the land. Bishop's analysis:Sec. 785.27 --- Attendance at ... training programs ... need not be counted as working hours if the following four conditions are met:

a) Attendance is outside the employee's regular working hours;

b) Attendance is in fact voluntary;

c) The course, lecture or meeting is not directly related to the employee's job; and

d) The employee does not perform any productive work during such attendance....

Sec. 785.29 --- The training is directly related to the employee's job if it is designed to make the employee handle his job more effectively as distinguished from training him for another job, or to a new or additional skill.

Sec. 785.30--...if an employee on his own initiative attends an independent school, college or trade school after hours, the time is not hours worked for his employers even if the courses are related to his job. (Bureau of National Affairs, Wages and Hours, p. 97:3208).

These regulations present employers with the following dilemma: either (a) don't provide training in general skills like reading or word processing that will improve a worker's productivity in their current job or (b) provide such training and pay all of its costs-instructional costs and trainee time costs. Thus, no matter how general the skill nor how voluntary the decision to take training, if it raises productivity in one's current job and is provided by the employer, the worker must be paid while engaged in training. Workers and employers are prohibited from cutting the following deal--the company will provide instructors, classrooms and certification, while the worker will commit uncompensated time to learning general skills that enhance productivity (Bureau of National Affairs 1993, 97:3208). Schools can offer such a deal, employers cannot.These regulations have three pernicious effects: they discourage employers from organizing formal training in general skills, they induce them to ration the training programs that they do offer and they force workers who seek such training to get it at a school. Since school based training of adults not paid for by their employer has no effect on wage rates, the regulations effectively push many workers into a type of training that does not appear to raise their wages. This constraint on how workers and employers share the costs of general training provided at the workplace is probably a very important source of market failure in the training market.If Bishop's right, this would of course be a prime case not of "market failure" but of government failure: Markets are perfectly able to train workers once government gets out of the way. But why can't markets circumnavigate the law by hiring workers-in-search-of-training at lower hourly wages?

The other way workers can share the costs of general training is by accepting lower wage rates during the training period. Under current regulations this is not really possible for short intermittent spells of training voluntarily undertaken by individual workers. For new hires, however, flexibility is greater because wages customarily rise with tenure on the job. In some low wage jobs, however, the minimum wage constraint is binding. Young inexperienced workers are, in effect prevented from bidding for training opportunities by offering to work for a low wage.The minimum wage aside, another snag that Bishop doesn't consider is that most low-skilled workers are too short-sighted, impatient, or distrustful to accept lower pay in exchange for training. As a result, these regulations may, like a banana subsidy, do great harm that would be child's play for thoroughly rational agents to avoid.

(7 COMMENTS)

Published on August 06, 2015 22:06

August 5, 2015

Ghost World and Zombieland, by Bryan Caplan

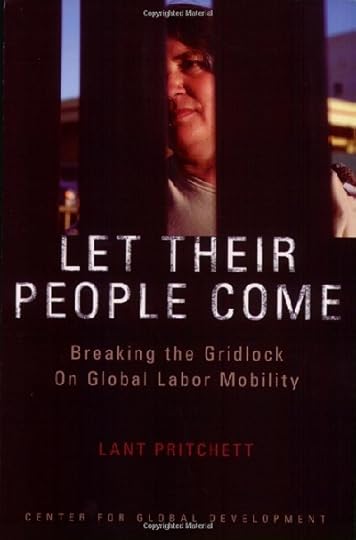

I'm embarrassed to admit that I only recently got around to reading Lant Pritchett's Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility. The full text is free and packed with goodness, but I learned the most from Pritchett's chapter on "ghost" versus "zombie" economies. Key idea:

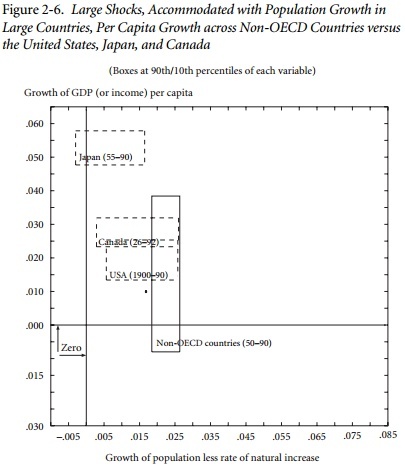

Large and persistentGraphically:

declines in labor demand in a region, perhaps because of technical

changes in agriculture or changes in resources, create two possibilities, which

I call "ghosts" or "zombies." If labor is geographically mobile and hence labor

supply is elastic, then large declines in labor demand will lead to large outward

migration--the process that created "ghost towns" in the United States.

However, if labor demand falls in a region and labor is trapped in that region,

by national boundaries for instance, the labor supply is inelastic and all the

accommodation has to come out of falling wages. A region that cannot

become a ghost (losing population) becomes a zombie economy--the economy

might be dead, but people are forced to live there.

Is this a big deal in the real world? Yes!

There are three sources of evidence, which together suggest that there are typically large shifts in the desired populations of regions. Though it is extremely difficult to separate out which of these are shifts in just an "unconstrained desired" population (due to remediable factors like policies, or, optimistically, institutions) and which are shifts in "optimal" populations, there is some evidence from comparing regions of countries (which share many policies and institutions) that some large fraction of the shifts in desired populations are also shifts in optimal population. These shifts in desired population are accommodated differently depending on the conditions for labor mobility. The three empirical examples are (1) regions of the United States, (2) comparisons of within-country versus cross-country variability of population and output per person growth rates, and (3) population versus output variability in history.Peek at evidence on (1):

I have assembled five regions of the United States, which, since I createdPeek at evidence on (2):

them, I will name: Texaklahoma (Northwest Texas and Oklahoma), Heartland

(parts of Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska), Deep South (parts of

Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama), Pennsylvania Coal and Great Plains

North (parts of Kansas and South Dakota). Even with the constraint of contiguity

and (mostly) convexity, one can assemble large territories that have seen

substantial absolute population decline. The Great Plains North is a territory

larger than the United Kingdom, and its population declined 28 percent from

1930 to 1990. Its current population is only a bit more than a third the population

it would have been if its population growth had been at the rate of natural

increase. The Texaklahoma region is bigger than Bangladesh and is now

only 31 percent the population size it would have been in the absence of outmigration.

Peek at evidence on (3):

The nineteenth century was truly an "age of mass migration" (Hatton andBottom line: If you can believe that huge areas within many countries are optimally empty (or nearly empty), the same could be true for entire countries. Ghost countries, like ghost towns, won't look pretty. But this is a classic case of "Is a place still ugly if nobody sees it?" Immigration restrictions turn ugliness few people ever see into ugliness millions experience every day.

Williamson 1998), because many of the "areas of recent settlement" had open

borders with respect to immigrants (at least with certain ethnic and national

origins). It was also an era of rapid reductions in transport costs and shifts

toward freer trade in goods, open capital markets, and massive movements in

capital--the first era of globalization. Hence, this period is an interesting

example of the question: "How would we expect geographically specific

shocks to be accommodated in a globalizing world?" Comparing Ireland to

Bolivia highlights the obvious: that nearly all developing countries with negative

shocks have seen their populations continue to expand rapidly, while

when there was freer labor mobility in the international system, labor movements

accommodated negative shocks

(6 COMMENTS)

Published on August 05, 2015 22:02

August 4, 2015

Student Loans and Bankruptcy, by Bryan Caplan

One of the main things I learned while writing

The Case Against Education

: Contrary to almost everyone, student loans are virtually the least objectionable government subsidy for college. Why? As you know, I firmly subscribe to the view that - from a social point of view - Americans spend far too long in school. Student loans are benign because they do almost nothing to increase schooling.

The key facts I learned:

1. While the federal government originates over a hundred billion dollars worth of loans each year, most of the loan is not a subsidy. The highest-quality estimate of the average 2010-2020 subsidy is 12% of the face value of the loan. Not 12-percentage points per year, mind you, but 12% of the face value total. On an annual basis, that's 4% of all government subsidies for higher education. In 2011, that comes to merely $13 billion a year.

2. Contrary to the credit market imperfections story, loan subsidies have about as much effect per dollar on college attendance as tuition cuts. The reason, on reflection, is pretty obvious: "Giving" people money for tuition isn't very motivating if they know they'll eventually have to repay what they received. Loan subsidies sweeten the deal, but knowing you'll effectively have to repay 88% of what you borrow is only slightly more enticing than knowing you'll have to repay 100% of what you borrow.

But isn't it awful that student loans survive bankruptcy? It's definitely awful for unemployed college graduates - and even worse for dropouts. For society, however, it's for the best. If borrowers could escape student debt via bankruptcy, taxpayers would make up the difference. This would probably substantially raise the implicit loan subsidy. And if I'm right about the social value of education, that's bad.

Still, as long as policy-makers ignore all the complaining about social loans and bankruptcy, the complaining serves a useful social function. I strongly suspect that few 18-year-olds fully realize how hard it is to weasel out of their student loans. The more often they hear pundits moan, "You can't escape student loans with bankruptcy! How terrible!" the scarier borrowing gets - and the less likely kids are to borrow or attend.

It's great that education reformers are talking about student loans and bankruptcy. Our goal, however, should not be to change bankruptcy law, but to publicize it.

(10 COMMENTS)

The key facts I learned:

1. While the federal government originates over a hundred billion dollars worth of loans each year, most of the loan is not a subsidy. The highest-quality estimate of the average 2010-2020 subsidy is 12% of the face value of the loan. Not 12-percentage points per year, mind you, but 12% of the face value total. On an annual basis, that's 4% of all government subsidies for higher education. In 2011, that comes to merely $13 billion a year.

2. Contrary to the credit market imperfections story, loan subsidies have about as much effect per dollar on college attendance as tuition cuts. The reason, on reflection, is pretty obvious: "Giving" people money for tuition isn't very motivating if they know they'll eventually have to repay what they received. Loan subsidies sweeten the deal, but knowing you'll effectively have to repay 88% of what you borrow is only slightly more enticing than knowing you'll have to repay 100% of what you borrow.

But isn't it awful that student loans survive bankruptcy? It's definitely awful for unemployed college graduates - and even worse for dropouts. For society, however, it's for the best. If borrowers could escape student debt via bankruptcy, taxpayers would make up the difference. This would probably substantially raise the implicit loan subsidy. And if I'm right about the social value of education, that's bad.

Still, as long as policy-makers ignore all the complaining about social loans and bankruptcy, the complaining serves a useful social function. I strongly suspect that few 18-year-olds fully realize how hard it is to weasel out of their student loans. The more often they hear pundits moan, "You can't escape student loans with bankruptcy! How terrible!" the scarier borrowing gets - and the less likely kids are to borrow or attend.

It's great that education reformers are talking about student loans and bankruptcy. Our goal, however, should not be to change bankruptcy law, but to publicize it.

(10 COMMENTS)

Published on August 04, 2015 22:06

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.