Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 112

October 18, 2015

Where Superforecasters Start, by Bryan Caplan

The first thing [superforecasters] would do is find out what percentage of American households own a pet.As far as I recall, I've yet to lose a bet I publicly blogged. What's my secret? I doggedly take the outside view. When long-run trends say X, and the "latest news" says Y, I go with X. When Democrats won big in 2008, I saw good luck, not a new political regime. That's why, in 2009, I bet my former co-blogger Arnold Kling that the Republicans would regain control of one branch of the federal government by 2017. I won in 2010. During the Great Recession, I saw a bad business cycle, not a "new normal." That why, in 2013, I bet Tyler Cowen that unemployment will fall below 5% by 2033. I am very close to winning already. When anyone forecasts any specific major disaster, I scoff. Disasters do happen, but almost all specific predictions of major disasters do not come to pass. And that's why I am eager to bet against such predictions.

Statisticians call that the base rate - how common something is within a broader class. Daniel Kahneman has a much more evocative visual term for it. He calls it the "outside view" - in contrast to the "inside view" which is the specifics of a particular case. A few minutes with Google tells me about 62% of American households own pets. That's the outside view here... Then I will turn to the inside view - all those details about the Renzettis - and use them to adjust that initial 62% up or down.

It's natural to be drawn to the inside view. It's usually concrete and filled with engaging detail we can use to craft a story about what's going on. The outside view is typically abstract, bare, and doesn't lend itself readily to storytelling.

I sometimes joke that "news melts your brain." What I really mean is that news amplifies our misguided impulse to take the inside view of things. To be a superforecaster, of course, you have to use the news to tweak the outside view. But most people would be better forecasters if they ditched the news and relied on base rates alone.

(5 COMMENTS)

October 15, 2015

Superforecasting on Epistemic Bait and Switch, by Bryan Caplan

[F]ew things are harder than mental time travel. Even for historians, putting yourself in the position of someone at the time - and not being swayed by your knowledge of what happened later - is a struggle. So the question "Was the IC's judgment reasonable" is challenging. But it's a snap to answer "Was the IC's judgment correct?" As I noted in chapter 2, a situation like that tempts us with a bait and switch: replace the tough question with the easy one, answer it, and then sincerely believe that we have answered the tough question.As far as I know, Tetlock is not a pacifist, but this is still intriguingly consistent with my common-sense case for pacifism. I'll know more Monday, when I finally get to meet him in person. If you see me there, please say hi.

This particular bait and switch - replacing "Was it a good decision" with "Did it have a good outcome?" - is both popular and pernicious. Savvy poker players see this mistake as a beginner's blunder... Good poker players, investors, and executives all understand this...

So it's not oxymoronic to conclude, as Robert Jervis did, that the intelligence community's conclusion was both reasonable and wrong. But - and this is the key - Jervis did not let the intelligence community off the hook. "There were not only errors but correctable ones," he wrote about the IC's analysis... Would that have made a difference? In a sense, no. "The result would have been to make the intelligence assessments less certain rather than to reach a fundamentally different conclusion."... This may sound like a gentle criticism. In fact, it's devastating, because a less-confident conclusion from the IC may have made a huge difference: If some in Congress had set the bar at "beyond a reasonable doubt" for supporting the invasion, then a 60% or 70% estimate that Saddam was churning out weapons of mass destruction would not have satisfied them...

But NIE 2002-16HC didn't say 60% or 70%. It said, "It has..." "Baghdad has..." Statements like these admit no possibility of surprise. They are the equivalent of "The sun rises in the east and sets in the west." At a White House briefing on December 12, 2002, the CIA director, George Tenet, used the phrase "slam dunk." He later protested that the quote had been taken out of context, but that doesn't matter here because "slam dunk" did indeed sum up the IC's attitude.

(8 COMMENTS)

October 14, 2015

Superforecasting: Supremely Awesome, by Bryan Caplan

I'm already an unabashed Tetlock fanboy. But his latest book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (co-authored with Dan Gardner but still written in the first person) takes my fandom to new levels. Quick version: Philip Tetlock organized one of several teams competing to make accurate predictions about matters we normally leave to intelligence analysts. Examples: "Will the president of Tunisia flee to a cushy exile in the next month? "Will an outbreak of H5N1 in China kill more than ten in the next month? Will the euro fall below $1.20 in the next twelve months." Tetlock then crowdsourced, carefully measuring participants' traits as well as their forecasts. He carefully studied top 2% performers' top traits, dubbing them "superforecasters." And he ran lots of robustness checks and side experiments along the way.

Quick punchline:

The strongest predictor of rising into the ranks of superforecasters is perpetual beta, the degree to which one is committed to belief updating and self-improvement. It is roughly three times as powerful a predictor as its closest rival, intelligence.But no punchline can do justice to the richness of this book. A few highlights...

An "obvious" claim we should all internalize:

Obviously, a forecast without a time frame is absurd. And yet, forecasters routinely make them... They're not being dishonest, at least not usually. Rather, they're relying on a shared implicit understanding, however rough, of the timeline they have in mind. That's why forecasts without timelines don't appear absurd when they are made. But as time passes, memories fade, and tacit time frames that seemed so obvious to all become less so.The outrageous empirics of how humans convert qualitative claims into numerical probabilities:

In March 1951 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) 29-51 was published. "Although it is impossible to determine which course of action the Kremlin is likely to adopt," the report concluded, "we believe that the extent of [Eastern European] military and propaganda preparations indicate that an attack on Yugoslavia in 1951 should be considered a serious possibility." ...But a few days later, [Sherman] Kent was chatting with a senior State Department official who casually asked, "By the way, what did you people mean by the expression 'serious possibility'? What kind of odds did you have in mind?" Kent said he was pessimistic. He felt the odds were about 65 to 35 in favor of an attack. The official was started. He and his colleagues had taken "serious possibility" to mean much lower odds.A deep finding that could easily reverse if widely known:

Disturbed, Kent went back to his team. They had all agreed to use "serious possibility" in the NIE so Kent asked each person, in turn, what he thought it meant. One analyst said it meant odds of about 80 to 20, or four times more likely than not that there would be an invasion. Another thought it meant odds of 20 to 80 - exactly the opposite. Other answers were scattered between these extremes. Kent was floored.

How can we be sure that when Brian Labatte makes an initial estimate of 70% but then stops himself and adjusts it to 65% the change is meaningful? The answer lies in the tournament data. Barbara Mellers has shown that granularity predicts accuracy: the average forecaster who sticks with tens - 20%, 30%, 40% - is less accurate than the finer-grained forecaster who uses fives - 20%, 25%, 30% - and still less accurate than the even finer-grained forecaster who uses ones - 20%, 21%, 22%. As a further test, she rounded forecasts to make them less granular... She then recalculated Brier scores and discovered that superforecasters lost accuracy in response to even the smallest-scale rounding, to the nearest .05, whereas regular forecasters lost little even from rounding four times as large, to the nearest 0.2.More highlights coming soon - the book is packed with them. But if any book is worth reading cover to cover, it's Superforecasting.

(13 COMMENTS)

October 13, 2015

They Scare Me, by Bryan Caplan

The church apparently approves of the show enough to buy three full

page ads in the Playbill program each theatergoer gets: Each page is a

close-up photo of an attractive young person with a quote such as "The

book is always better" and a refer to thebookofmormon.org."I can

appreciate that it got people talking," Brooks said. "I think it makes

people even more curious to learn about what Mormons believe."

Occasionally, though, I wonder: What would happen if Mormons were a solid majority of the U.S. population? Maybe they'd be as wonderful as ever, but I readily picture a sinister metamorphosis. Given enough power, even Mormons might embrace a brutal fundamentalism. Despite my lovely experiences with Mormons, they scare me.

To be fair, they're hardly alone. You know who else scares me? Muslims, Christians, Jews, Hindus, and atheists. Sunnis, Shiites, Catholics, and Protestants. Whites, blacks, Asians, Hispanics, and American Indians. Democrats, Republicans, liberals, conservatives, Marxists, and reactionaries. Even libertarians scare me a bit. Why? Because given enough power, there's a serious chance they'll do terrible things. Different terrible things, no doubt. But terrible nonetheless.

If you're afraid of every group, though, shouldn't you support whatever group has the minimum chance of doing terrible things once it's firmly in charge? Not at all. There's another path: Try to prevent any group from being firmly in charge. In the long-run, the best way to do this is to make every group a small minority - to split society into such small pieces that everyone abandons hope of running society and refocuses their energy on building beautiful Bubbles. As Voltaire once put it:

If one religion only were allowed in England, the Government would very

possibly become arbitrary; if there were but two, the people would cut

one another's throats; but as there are such a multitude, they all live

happy and in peace.

When people lament the political externalities of open borders, they're usually picturing an influx of a group with a bad track record of being in charge. In a sense, these critics understate their case; numerical superiority can turn even the nicest groups into a mortal danger. But critics also overlook the open borders remedy: Diaspora dynamics notwithstanding, welcoming everyone is a great way to turn everyone into a minority. And while that hardly guarantees safety, it's less menacing than the status quo.

Don't believe me? Picture the group of humans that currently scares you the most. They're still only x% of the world's population, where x is probably less than 25%. Now imagine what would happen if your scariest group were x% of every country's population. Even if its individual members stayed equally scary, they'd become far less globally dangerous than they are now. But that's not all. Once the members of the group that scares you the most loses all hope of running the show, most will calm down. In time, they too might be nice as Mormons.

Still don't believe me? Walk around the campus of George Mason University. Whatever group scares you the most is well-represented. But before long, you won't be scared. Every group is too small to run the show - and every group knows it. And when you see it with your own eyes, you'll know it too.

October 12, 2015

Missing Links, by Bryan Caplan

1. Me on open borders in TIME.

2. Alex Tabarrok on open borders in The Atlantic.

3. Scott Alexander on me on mental illness.

Oh, and I forgot:

4. The Chronicle of Higher Education on Tetlock's Superforecasters.

(9 COMMENTS)

October 6, 2015

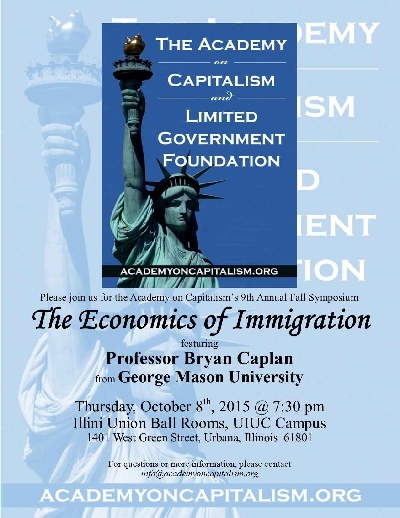

Open Borders Comes to Illinois, by Bryan Caplan

October 5, 2015

Home Schooling Questions: Economists vs. the Public, by Bryan Caplan

1. What makes you think you're qualified to teach them?

2. Who are you to decide what your kids should study?

3. What about socialization?

4. How come you're not teaching [insert pet subject here]?

5. Won't this hurt your kids later in life?

6. Aren't you hurting your kids' development right now?

7. When will they interact with girls?

8. Isn't there more to life than academics?

9. Aren't you undermining social cohesion?

10. Why are you turning your kids into brainwashed freaks?

Questions economists ask when I tell them I'm homeschooling my sons:

1. Doesn't it take a lot of time?

(26 COMMENTS)

October 4, 2015

What I Learned from Gordon Tullock, by Bryan Caplan

(1 COMMENTS)

October 1, 2015

My Simplistic Theory of Left and Right, by Bryan Caplan

There are many prominent candidates, like:

1. Leftists care more about equality, rightists care more about efficiency.

2. Leftists care more about the poor, rightists care more about the rich.

3. Leftists are more secular, rightists are more religious.

To my mind, though, all these theories overintellectualize Left and Right. Neither ideology is a deduction from first principles. Not even close. What binds Leftists with fellow Leftists, Rightists with fellow Rightists, is not logic, but psycho-logic . Feelings, not theories.

What's my alternative? This:

1. Leftists are anti-market. On an emotional level, they're critical of market outcomes. No matter how good market outcomes are, they can't bear to say, "Markets have done a great job, who could ask for more?"

2. Rightists are anti-leftist. On an emotional level, they're critical of leftists. No matter how much they agree with leftists on an issue, they can't bear to say, "The left is totally right, it would be churlish to criticize them."

Yes, this story is uncharitable and simplistic. But clarifying. Communists and moderate Democrats are vastly different, but they have something in common: Free markets get on their nerves. Nazis and moderate Republicans are vastly different, but they too have something in common: Leftists get on their nerves. Within each side, the difference between moderates and extremists is the intensity of their antipathy, not the object of their antipathy.

To see my point, imagine two grand conventions. The first is for all self-identified Leftists. The second is for all self-identified Rightists. Now imagine a grand Compromise Statement able to command the assent of 80% of the attendees. I say the Left's Compromise Statement will consist in a bunch of complaints about markets. And I say the Right's Compromise Statement will consist in a bunch of complaints about Leftists.

To be clear, my theory of Left and Right is tentative. If you know of relevant evidence one way or the other, I'm listening.

(37 COMMENTS)

September 30, 2015

Betting, Liberty, and the Status Quo, by Bryan Caplan

Not really. In the modern world, economic growth is the norm. So as long as government's absolute size stays fixed, economic growth steadily erodes government's role in society. And over time, every new industry that the government failed to foresee is at most lightly regulated.

Furthermore, entrepreneurs and scofflaws are constantly looking for clever ways to circumvent existing laws. As long as regulations stay fixed, their practical impact naturally shrinks year after year. Imagine what the United States would look like today if governments stopped passing new laws in 1970. Airline and trucking regulation would still be on the books, but they'd be pretty easy to dodge with the help of the internet. It wouldn't be Libertopia, but it would be a lot more libertarian than our status quo.

So does the betting norm favor the status quo or liberty? Both. It favors the legal status quo. Over time, however, a stagnant legal status quo naturally decays into de facto laissez-faire.

(6 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers