Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 110

November 17, 2015

A Swarm of Thoughts on Hive Mind, by Bryan Caplan

1. At the individual level, IQ is much more highly correlated with job performance than income. So while national IQ has a bigger effect on national income than personal IQ does on personal income, it's less clear that national IQ has a bigger effect on national productivity than personal IQ does on personal productivity.

How could income and productivity two diverge? Imperfect information could arguably do the trick, but a stronger story is that egalitarian norms compress pay within countries, but not between countries. This needn't make Garett's mechanisms irrelevant, but it would imply that what he calls the "IQ paradox" is markedly smaller than it looks.

2. Quite a few economists, most notably Hanushek, emphasize the social benefits of raising academic test scores. Garett's IQ-centric story is far more credible. It's easy to see how an across-the-board increase in intellectual prowess would have far-reaching social benefits. It's much harder to see how better math skills would have such effects. After all, most people already use far less math on the job than they learned in school.

3. Garett reviews a lot of evidence on the determinants of the global IQ gap, but as far as I can tell never references what seems like the most probative evidence: IQ studies of transnational adoptees. This especially relevant for Third World IQ. How much of the IQ gap reflects Third World deprivation? Just compare the IQs of adoptees born in the Third World to the IQs of their non-adopted biological siblings. True, this understates the environmental effect because even adoptees endure a subpar Third World prenatal environment, but it's still a compelling lower bound.

When I asked Garett about this, he assured me that such research exists. But nothing great pops up on Google Scholar. So what are the best studies, and what do they conclude?

4. I can easily imagine Hive Mind inspiring a wave of IQ NIMBYism. I can also imagine it reinvigorating Soviet-style emigration restrictions to fight "brain drain." This doesn't mean Garett's wrong, any more than nuclear war would invalidate Einstein's theory of relativity. But it's a sobering thought - and Garett doesn't seem sobered by it.

5. While Garett shies away from moral judgment, he could easily filter his results for an array of moral perspectives: utilitarian, nationalist, Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, egalitarian, etc. Even for the nationalist, this is more complicated than it sounds: If Congo's national IQ rises by 10 points, the beneficiaries including Congo's trading partners as well as Congo itself. But if the book's worth writing, this complicated question is worth tackling. I've discussed these ideas with Garett for years and read his book carefully. But if you asked me, "What would a cosmopolitan Jonesian think?," my answer remains hazy at best.

6. Some of Garett's mechanisms - like the political effects of IQ - seem like genuine externalities. Others - like the effects of IQ on savings - don't. In terms of standard welfare economics, how does Garett classify each of his channels? Inquiring minds want to know.

7. The last question comes from my three-year-old daughter: "Is it a bee book?" Well? :-)

Bonus Question: Whenever I see growth regressions, I routinely ask, "What happens if you weight by population?" 1.3B high-IQ, low-income Chinese seem like they could be a big fly in the ointment. Are they?

(7 COMMENTS)

Take This Ideological Turing Test, by Bryan Caplan

November 16, 2015

The Architecture of Hive Mind, by Bryan Caplan

My debate partner and former co-blogger Garett Jones' Hive Mind: How Your Nation's IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own is finally out. It's a wonderful book in both substance and style - peak Garett. He instinctively hews to my seven guidelines for writing worthy non-fiction. Guideline-by-guideline:

1. Pick an important topic. "Why are some countries rich and other countries poor?" is perennial. "Why does national IQ have a bigger effect on national income than personal IQ does on personal income?" may not seem earth-shaking on the surface, but Garett powerfully argues that IQ is an elephant in the room.

2. Learn a lot

about your topic. Garett's read widely in macro, development, psychology, experiment econ, and beyond. You can also tell he's traveled the world with his eyes open.

3. Keep telling yourself: "Once I perfect

the organization of my book, it will practically write itself." Garett breaks his book down into a gripping introduction and ten pithy chapters. The introduction shines a blinding spotlight on the key facts about national IQ and national prosperity. Having piqued your interest, he then tries to get every reader on the same page. Chapters 1-3 target reach out to IQ skeptics, and explain the saga of the Flynn Effect. Chapters 4-8 explain the most plausible mechanisms behind IQ's macroeconomic effects. Chapter 9 explores the implications for immigration so fairly I found myself nodding throughout. Chapter 10 wraps it all up. Elegant!

4.

Never preach to the choir. Garett earnestly tries to reach not only the typical IQ-apathetic economist, but the typical IQ-phobic intellectual. While I'm often saddened by Garett's Twitter-tone, Hive Mind is a sociologically Mormon book - thoroughly intellectually friendly.

5. When in doubt, write like Hemingway. Hive Mind is probably the most beautifully written book ever produced by a GMU economist. Flip to a random page, and you will find great sentences. For example, here's what I found when I randomly flipped to page 143:

The lawyers working on a billion-dollar corporate merger are probably working with an O-ring technology, in which one typo can mean a $100 million lawsuit down the road, and if you're having open heart surgery it's probably a good idea to have the best nurses, the best cardiologists, and the best anesthesiologists together in the same room. On a routine appendectomy you'll rarely see that combination: we all say we want "the best doctor," but the best doctor's time is scarce, and it's probably best for his time to be spent working on crucial surgeries as part of a high-quality team.And:

In Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the Enterprise is trying to escape another Federation ship. Scotty, the engineer of the Enterprise, had been on the pursuing ship a little earlier. When the Enterprise jumps to warp speed, the pursuing ship tries to do the same, but sputters to a halt. Back on the Enterprise, Scotty pulls some electronic gadget out of his pocket and turns to Captain Kirk: "The more they overthink the plumbing, the easier it is to stop up the drain." The longer the chain of production, the easier it is to break the links.

6.

Treat specific intellectual opponents with respect, in print and

otherwise, even if they don't reciprocate. But feel free to ridicule

ridiculous ideas. Garett is especially effective at undermining defensive statistical illiteracy: "Every person we meet, every nation we visit, is an exception to the rules - but it's still a good idea to know the rules."

7. Don't keep your cards close to your chest. While Garett strives to be friendly, being understood is his top priority. He knows that many readers won't like the idea that poor countries are poor to a large degree because their inhabitants are cognitively slow. But he says it anyway. If you've watched my debate with Garett, you may be tempted to object that Garett kept even more controversial claims out of the book. But when you have as many cards as Garett, you've got to avoid information overload.

(9 COMMENTS)

November 12, 2015

Reflections on the Caplan-Jones Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

1. Garett neatly boils down research on migration-adjusted measures of "deep history." I'll blog the papers later, but one key finding is that countries now inhabited by the descendants of historically advanced civilizations do much better than countries now inhabited by descendants of historically backwards civilizations. How do they measure "advanced" and "backward"? Several ways, especially state history (S), dawn of agriculture (A), and technology in 1500 AD (T). Garett, going for a double entendre, calls this the SAT score.

2. Garett was coy about the immigration policies that he does favor. But his talk suggested - and grilling confirmed - that he has no objection to open borders with countries with high SAT scores - including China and India! That's billions of people. Thus, while opponents of immigration might like Garett's tone, he offers no argument against radically more open immigration than currently exists. Indeed, it's fair to say that Garett is about halfway between the mainstream American view and me.

3. Garett opened his statement by claiming that economists urge us to focus on the very long-run - the consequences of policies a century or more in the future. He's mistaken. The essence of the economic approach to intertemporal choice is not focusing on the distant future, but relying on a consistent social discount rate. Economists tend to favor relatively low discount rates or 2-3%. But that still implies that we should largely ignore consequences a century or more in the future. With a 2.5% discount rate, $1 in 2125 is only worth $.08 today.

Garett could reply that we should use a much lower social discount rate - say 1%. But this has all sorts of bizarre implications. It implies, for example, that governments are investing too little in almost everything. Government should dramatically curtail our current consumption to enrich our great-grandchildren. At minimum, governments should heavily raise taxes, and use the money to invest in sovereign wealth funds. Earning more than 1% a year is easy. As far as I know, Garett has never advocated such policies.

Rhetorically, Garett did a good job of selling the importance of the future by reminding audience members to think of their "children and grandchildren." But he didn't mention that people who care about their descendants needn't rely on government policy. Anyone who wants to help their children and grandchildren can simply spend less money, invest the savings, then provide a bigger inheritance. If you aren't already doing this, you don't actually care very much how your descendants will be doing a century hence. Nor should you - there's every reason to think they'll be a lot richer than you are.

4. Why is there such a chasm between Garett's tone and his substance? I'm

frankly baffled. In person, Garett is one of the nicest people I know,

so I'd expect him to at least stand up for the billions of immigrants

that - in his own view - the First World brutally excludes for no good

reason. But he chooses to leave them hanging.

What's my least-bad guess about Garett's thinking? Well, it's no secret that he's a meta-ethical moral relativist.

Speculation: As a result of this position, Garett is (a) uncomfortable

making moral judgments, (b) disinclined to make his own moral judgments

internally consistent, and (c) reluctant to condemn positions that

intuitively seem deeply evil. Logically speaking, of course, a

meta-ethical moral relativist could be an enthusiastic moralist. But

psychologically speaking, moralizing weighs on the conscience of a

relativist.

P.S. Garett's Hive Mind is now in stores. It's a wonderful book in every way, Garett at his very best.

(14 COMMENTS)

November 8, 2015

Caplan-Jones Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

The debate is open to the public, and will be held in the Griswold Lecture Hall. And it interestingly happens the night before the official release of Garett's new book, Hive Mind: How Your Nation's IQ Matters So Much More Than Your Own .

I'll be blogging this important, careful, thought-provoking, and earnest book in coming weeks, but Garett tells me he won't be emphasizing its thesis in the debate.

(5 COMMENTS)

November 5, 2015

Humane Canada, by Bryan Caplan

Have you or any of your immediate family had any serious health problems?Most will no doubt take it for granted that a single serious health problem disqualifies an entire family. But to me, it's a Monty Python , "Come and see the violence inherent in the system!" moment.

No

Yes - not eligible

The health exclusion clearly isn't about contagion; it's about socialized medicine. Canadians don't want to pay for foreigners' health care. Why not admit the sick, subject to the proviso that their health care is their own problem? Unthinkable! By the twisted logic of the welfare state, Canadians have to pay for the health care of anyone within their borders. Thanks to these odd qualms, foreigners endure sickness and poverty at home instead of sickness and prosperity in Canada. And who knows, maybe a First World job would let foreigners pay for the health care they or their loved ones need, allowing them to enjoy health and prosperity without burdening Canadian taxpayers?

Canadians are hardly alone, so why single them out? Because their blatant exclusion of sick foreigners directly contradicts their stellar international reputation for compassion and common sense. As usual, the welfare state isn't about helping the poor and desperate. It's about helping relatively poor and desperate members of your tribe while keeping absolutely poor and desperate human beings comfortably out of sight. Sick.

(13 COMMENTS)

November 4, 2015

Gonzalez on the Multicultural Threat, by Bryan Caplan

In my talk, I underlined the point that another friend, Niger Innis,

always makes: Even if we were to shut the immigration doors completely,

the next president will have to start reversing the social engineering

of the past five decades.

If he or she doesn't, we will end up with another country, and not a

better one. Bryan Caplan is a nice guy, but he's wrong; multiculturalism

is taking root and reordering society.

At risk of compromising my "nice guy" status, Mike's evidence is underwhelming. Why should we think identity politics is winning in America? First, a little sensational journalism:

It is there in small ways. For example, when the principal at a San Francisco middle school cancels the student government election

because too many white students won--and cluelessly defends abrogating

the student's choice by saying, "I want to make sure the voices are all

heard!"

It is also there when Salon writes the umpteenth brainless blog post (of the morning) decrying how there are not sufficient cast members of this group or that on any given TV show.

The whole new environment has left Peggy Noonan pining for Joe Biden, because the vice president reminds her of Democrats of old.

Second, a little history of thought:

[M]ulticulturalism builds on the works of Marxist European thinkers

such as Herbert Marcuse and Antonio Gramsci, whose "Critical Theory" has

greatly influenced American progressives.As my colleague John Fonte and I wrote recently

in The Weekly Standard, multiculturalism inherits from Critical Theory

the idea that society is "divided along racial, ethnic, and gender lines

into a dominant group (white males) and 'marginalized' groups (ethnic,

racial, linguistic, and sexual minorities). The goal of politics should

be first to 'delegitimize' the ideas of the American system and second,

to transfer power from the dominant group to the 'oppressed' groups."

Read the whole piece; I don't see anything else resembling evidence. If that's all one of the most prominent opponents of multiculturalism has to offer, I shall sleep easier than ever. What would count as evidence? Some basic facts from public opinion would be a great start. I'm only a dabbler here, but if we'd really endured five decades of social engineering, you'd think it would show up in the General Social Survey. Most of the most pertinent questions were only asked in 1994, but here's what Americans thought after what Mike paints as thirty years of strident multicultural indoctrination.

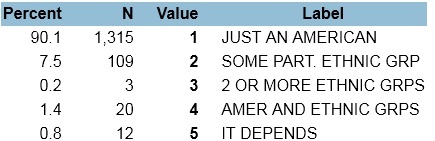

Question: "When you think of social and political issues, do you think

of yourself mainly as a member of a particular ethnic, racial,

or nationality group or do you think of yourself mainly as just

an American?

Answers:

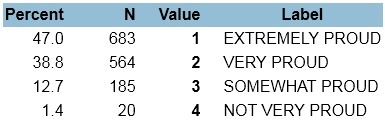

Question: "How proud are you to be an American?

Answers:

What about longer-run trends? This was asked in 1996, 2004, and 2014: "Some people say the following things are important for

being truly American. Others say they are not important. How

important do you think each of the following is... g. To feel

American."

Answers:

If I were Mike, I'd be tempted to hail the big decline from 2004 to 2014. But the change from 1996 to 2014 is barely visible. The simplest explanation is that 2004 was the tail-end of the post-9/11 rally-round-the-flag effect.

The best evidence for Mike's view: If you regress these responses on age, you do indeed see that younger respondents have a more multicultural orientation. The size of the difference, though, is minute - in the ballpark of one year of age making answers on a 1-4 or 1-5 scale a hundredth of a point more multicultural. On the implausible assumption that multicultural propaganda explains all of this generational shift, it's still chicken feed.

I freely concede that I'm only doing a fly-by of the relevant public opinion evidence. Feel free to add to my efforts in the comments. But Mike's the one claiming the damage of a half-century of multicultural social engineering is all around us. I don't see it.

Where does Mike go wrong? Like most intellectuals, he takes ideas seriously. An admirable trait, but it blinds him to the fact that most people don't take ideas seriously. Whatever their pseudo-intellectual pretensions, normal humans are lazy, forgetful, and compartmentalized. Putting multiculturalism in a history textbook does little harm because most students - and plenty of teachers - don't even read the textbook. The identity politics activists that Mike decries aren't America. In fact, there's little sign that most Americans know these activists are alive.

(13 COMMENTS)

November 3, 2015

Cochrane's Questions About Inequality, by Bryan Caplan

More puzzling, why are critics on the left so focused on the 1% in the

US, when by many measures we live in an era of great leveling?

Earnings inequality between men and women has narrowed drastically, as Kevin Murphy reminded us. Inequality across countries,

and thus across people around the globe, has also been shrinking

dramatically even as income inequality within advanced countries has

risen. One billion Chinese were rescued from totalitarian misery, and a

billion Indians sort-of-rescued from British-style license-Raj

socialism. These are wonderful events for human progress as well as,

incidentally, for global inequality. Sure, these countries have many

political and economic problems left, but the "its' all getting worse"

story just aint' so...

Look at Versailles. Nobody, not even Bill Gates, lives like Marie

Antoinette. And nobody in the US lives like her peasants. In 1960, Mao

Tse-Tung waved his hand and 20 millions died. In 1935, Joseph Stalin

did the same. Neither reported a lot of income to tax authorities for

economists to measure "inequality." It is preposterous to claim that,

even the citizens of Ferguson Mo., with all their problems and

injustices, are less equal now than they were in 1950. Or 1850.

Why does it matter at all to a vegetable picker in Fresno, or an

unemployed teenager on the south side of Chicago, whether 10 or 100

hedge fund managers in Greenwich have private jets? How do they even know

how many hedge fund managers fly private? They have hard lives, and a

lot of problems. But just what problem does top 1% inequality really

represent to them?

A striking tension:

Some wise cynicism in the spirit of Gordon Tullock:

I've been reading Piketty, Saez, Krugman, Stiglitz, the New York Times

editorial pages to find the answers. They all recognize that inequality

per se is not a persuasive problem, so they must convince us that

inequality causes some other social or economic ill.

Here's one. Standard and Poors economists wrote a recent summary report on inequality, (earlier post here) perhaps as penance for downgrading the US debt, and wrote

As income inequality increased before the crisis, less affluent

households took on more and more debt to keep up--or, in this case,

catch up--with the Joneses....

In Vanity Fair, Joe Stiglitz wrote similarly that inequality is a problem because it causes

a well-documented lifestyle effect--people outside the top 1 percent

increasingly live beyond their means....trickle-down behaviorism

Aha! Our vegetable picker in Fresno hears that the number of hedge fund

managers in Greenwich with private jets has doubled. So, he goes out and

buys a pickup truck he can't afford. Therefore, Stiglitz is telling

us, we must quash inequality with confiscatory wealth taxation... in order

to encourage thrift in the lower classes?

If this argument held any water, wouldn't banning "Keeping up with the

Kardashians" be far more effective? (Or, better, rap music videos!) If

the problem is truly overspending by low income Americans, can we not

think of more directed solutions? For example, might we not want to

remove the enormous taxation of savings that they face through social

programs?

Another example. The S&P report moved on to a new story: Inequality

is a problem because rich people save too much of their money, and poor

people don't. So, by transferring money from rich to poor, we can

increase overall consumption and escape "secular stagnation."

I see. Now the problem is too much saving, not too much consumption. We

need to forcibly transfer wealth from the rich to the poor in order to

overcome our deep problem of national thriftiness.

I may be bludgeoning the obvious, but let's point out just a few ways

this is incoherent. If Keynesian "spending" and "aggregate demand" are

the problems behind low long-run growth rates - and that's a big if -

standard Keynesian answers are a lot easier solutions than confiscatory

wealth taxation and redistribution. Which is why standard Keynesians

argued for monetary and fiscal policies, not confiscatory

anti-inequality taxation, until the latter became politically popular.

In a series of recent blog posts, (see coverage here)

Paul Krugman offers evidence that people vastly underestimate how

wealthy the rich are, bemoans how they live separate lives -- my fry

cook has, in fact, no idea of their lifestyle -- and argues for

confiscatory taxation to eliminate the "externality" of their excessive consumption. Well, I'm glad logical consistency isn't holding back these arguments.

P.S. When I die, I hope the conference volume in my honor is half as good as this one!

The most common argument is that we have to reduce income inequality to

avoid political instability. If we don't redistribute the wealth, the

poor will rise up and take it. As a cause-and effect claim about human

affairs, this is dubious amateur political science, one that would look

especially amateurish to the political scientists and historians at this

Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. Maybe the poor should

rise up and overthrow the rich, but they never have. Inequality was

pretty bad on Thomas Jefferson's farm. But he started a revolution, not

his slaves.

(26 COMMENTS)

November 2, 2015

The Punchline of Labor Market Regulation, by Bryan Caplan

Last night, while rewatching the classic Simpsons "Saddlesore Galatica," I came across a great pedagogical moment that even Homer Economicus: The Simpsons and Economics misses. In the episode, an abusive horse trainer flees from the state fair, leaving his mistreated equine behind. Hilarity ensues:

Officer Wiggum: I'm afraid this horse is going

to the dog food factory.

Homer: Good luck getting a horse

to eat dog food.

Bart: You can't do that to Duncan. It's not his fault that his owner was a sleaze.

Officer Wiggum: Look. I just want the horse to have

a good home or be food. If you want to take him, fine with me.

Though the Simpsons writers almost surely didn't intend this as a critique of labor market regulation, the shoe fits. Imagine Officer Wiggum on...

The minimum wage: "Look. I just want the worker to make $15 an hour or be unemployed."

Health insurance mandates: "Look. I just want the worker to have free medical care or be unemployed."

Firing restrictions: "Look. I just want the worker to have complete job security or be unemployed."

Could legally imposing these stark ultimatums be good strategy for pro-worker policy-makers? Anything's possible. The point is that stark ultimatums are a double-edged sword, not a no-brainer. A devoted horse-lover really could sensibly favor an option in between "good home" and "food." A friend of the workers really could sensibly oppose the minimum wage. It all depends on something almost no human being even understands, much less measures: elasticities.

(8 COMMENTS)

October 29, 2015

The Danger of Economics, by Bryan Caplan

This thought is frequently thrown at me and other advocates ofAnd:

laissez-faire, such as when protectionists allege that our endorsement

of unilateral free trade ignores "market imperfections" and other

"complexities" that aren't discussed in econ-principles courses. Ditto

for our opposition to minimum-wage legislation. ("Don't you know that

real-world markets aren't as perfect as they are in ECON 101

textbooks?!") Ditto, indeed, for almost every endorsement issued by an

economist for laissez-faire policies.It's this thought that I wish here to discuss.

This thought - that serious discussions of real-world policies often

require more than knowledge of a freshman-level economics course - can

be interpreted to be trivially true...But it does not follow - from the above rather trite, if true, concession - that a knowledge of only principles

of economics is "dangerous." My strong sense, from having carefully

observed public-policy making and public-policy discussion for nearly 40

years now, is that what is dangerous is a lack of knowledge of

principles of economics. The problem is not that most politicians and

pundits take economic principles too literally; the problem is that most

politicians and pundits are utterly ignorant even of these principles.The typical politician does not oppose free trade because he took an

advanced econ course and learned there that, under just the right

combination of real-world circumstances, an optimally imposed tariff can

be justified on economic grounds. No. The typical politician opposes

free trade because he doesn't understand the first thing about

economics. He doesn't understand that the purpose of trade - any trade - is to enrich people as consumers and not to enrich people as producers. He doesn't understand that exports are a cost and

that imports are a benefit; he thinks that it's the other way 'round.

He doesn't understand that the specific jobs lost to imports are not

the only employment consequences of trade; he doesn't understand that

trade also 'creates' jobs in the domestic economy. He doesn't

understand that domestic producers protected by government from

competition have diminished, rather than intensified, incentives to

improve efficiencies of their operations. He, in short, doesn't

understand the first damn thing about the economics of trade. And nor

do most of his constituents. If these constituents understood basic

economics and basic economics only, they would better understand that

this politician's policies are economically harmful and that his policy

statements are malarky.The typical politician doesn't support minimum-wage legislation

because she has concluded, after careful study, that employers of

low-skilled workers have sufficient amounts of monopsony power in the

labor market (as well as monopoly power in their output markets) to

nullify the prediction of basic supply-and-demand analysis and, instead,

to create real-world conditions that enable a scientifically set

minimum wage actually to improve the welfare of most low-skilled workers

without reducing the employment prospects of any of them. No. She

supports minimum-wage legislation because she believes that raising the

minimum wage will result simply in all low-skilled workers getting the

stipulated pay raise without any negative consequences befalling these

workers. And most of her constituents - even those low-skilled workers

whose jobs are put at risk by the minimum wage - share her economically

uninformed belief.

The claim that I see many people (mostly on the political left) making is something like the following: "Oh,

principles of economics is too simplistic. Reality is so complex that,

when one learns advanced economics, the policy prescriptions that a

student takes from his or her principles course are typically shown to

be faulty. Here are some examples. The Minimum wage: Econ principles

show that it destroys jobs for low-skilled workers, but advanced

economics shows that it can be good for those workers. FDA regulation:

Econ principles show that it prevents consumers from gaining access to

pharmaceuticals that can benefit consumers, but advanced economics shows

that such regulation can be good for consumers. Workplace-safety

regulation: Econ principles show that competition for workers obliges

firms to supply optimal levels of safety, but advanced economics shows

why this conclusion is mistaken."

If claims such as these are generally true, then what is being taught as economic principles would be anti-principles.

If claims such as these are generally true, then what is being taught

as economic principles would be, at best, simplifications of reality so

extreme that they misinform students rather than inform them. If claims

such as these are generally true, then the typical econ-principles

student should demand a refund of his or her tuition and compensation

for being defrauded by his or her college.

But, instead, if what is taught in (good) principles of

economics classes (such as I am sure are featured at George Mason

University) is in fact solid principles of economics, then

principles-of-economics students are better informed about reality at

the end of the semester than they were at the semester's start. Such

students can use these principles as a generally reliable, if not

infallible, guide to understand reality and to predict the general

consequences of typical government interventions such as price controls

and trade restrictions.

Put differently, suppose that the knowledge conveyed to students of,

say, good introductory physics courses were analogous to the knowledge

of what people who disparage principles of economics believe is

conveyed to students of introductory economics course. In that case,

then the likes of Newton's Laws of Motion and Boyle's Law would be

downright misleading when used to understand most instances of

observed reality. Of course, in reality these basic laws of physics are

not misleading, although they also are understood not to reveal all

relevant details of the reality that they are used to describe.

Related: Me on "Who Loves Bastiat and Who Lives Him Not."

(10 COMMENTS)Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers