Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 108

December 27, 2015

Two Public Choice Questions, by Bryan Caplan

3. Local governments provide free public education to

residents' children, regardless of the taxes they pay or family size.

T, F, and Explain: This is NOT what the Tiebout model predicts.

6. Suppose voters were rational and the Self-Interested Voter Hypothesis

were true.

T, F, and Explain: Democracies would spend a

higher share of their budgets on genuine public goods.

P.S. Citing past EconLog posts is perfectly acceptable.

(16 COMMENTS)

December 22, 2015

Labor Econ Versus the World: Ecumenical Edition, by Bryan Caplan

Yes and no. Of course college class should provide a balanced discussion of the issues. But if students arrive with a bunch of silly preconceptions, changing the way students see the world is a precondition for balanced discussion. Take evolution. Of course, a good class in evolution provides a balanced discussion of the issues. But if students arrive as committed creationists, the professor can't teach them until creationism has been thoroughly critiqued.

But are they really any popular preconceptions in labor economics as ludicrous as creationism? I say there are, starting with what I called Tenet #1 of our secular religion: "The main reason today's workers have a decent standard of living is that government passed a bunch of laws protecting them." How do we know it's false? Most obviously, because even if you assume zero disincentive effects, equally dividing premodern incomes still yields absolute poverty. More subtly, because employers treat most workers far better than the law requires; competition's the only credibly explanation. How do we know Tenet #1 is popular? Because it's ubiquitous; until you study economics, it's virtually the only story you hear.

I'm well-aware that many - perhaps most - labor economists - consider labor regulation on balance helpful for workers. Not critical, just helpful. Even if they're right, they should still spend ample time dissecting Tenet #1. Why? Because you can't have a reasonable discussion of the costs and benefits of labor regulation until you root out all the silly hyperbole students bring to the table.

Think about how few successful politicians of either party openly favor

the abolition of the minimum wage. A few support the minimum wage because they're

convinced labor demand is highly inelastic. All the rest just rely

on our secular religion: passing "pro-worker" laws is a clear-cut way to

dramatically help the common man.

My fellow labor economists' mistake: Since they weigh the merits of labor regulation for a living, they forget that non-economists can't even imagine what the downsides might be. If professors fail to spell them out in gory detail, students will remain oblivious to the downsides for the rest of their lives.

(8 COMMENTS)

December 21, 2015

Labor Econ Versus the World: Further Thoughts, by Bryan Caplan

1. In my youth, I saw Industrial Organization as the heart of our secular religion. My history textbooks loudly and repeatedly decried "monopoly"; teachers, peers, and parents echoed their complaints. Since the late-90s, however, such complaints have faded from public discourse. The reason isn't that plausible examples of monopolies have vanished. If anything, firms that look like monopolies - Amazon, CostCo, WalMart, Starbucks, Uber, Facebook, Twitter - are higher-profile than ever. But the insight I preached in my youth - the main way firms obtain and hold monopoly on the free market is reliably giving consumers great deals - is almost conventional wisdom. What modern consumer fears Amazon or Starbucks?

2. Another reason Industrial Organization has faded from our secular religion: Thanks to e-commerce and internet reviews, it's now indisputable that reputation impels firms to treat their customers well. When people want to buy with confidence, almost no one asks, "Does the government regulate this?" Instead, they scrutinize the seller's reputation.

3. Since moderns are satisfied with markets as consumers, it's only natural that our secular religion focuses on producers. For the vast majority of us, "producer" means "employee."

4. The main lesson of labor econ is that markets for labor closely resemble markets for other goods. Why then are people so eager to believe that unregulated labor markets are terrible? Part of the reason is that the little differences are occasionally traumatic. Wages don't adjust like stock market prices, so involuntary unemployment is a real and frightening prospect.

5. Another important reason, though, is that markets where people trade vaguely-defined products for cash tend to be acrimonious. When products are vague, the side paying cash often feels ripped off, and the side receiving cash often feels insulted. In most markets, sellers strive to standardize products to preempt this acrimony. In labor markets, however, this is inherently difficult because every human is unique. As a result, employers often lash out at workers because they feel cheated, and employees often resent employers because they feel mistreated.

6. These problems are amplified by the fact that our jobs are central to our identities. So when we feel mistreated by a boss (or by co-workers the boss fails to control), we experience it as a serious affront. This in turn leads people to demonize employers as a class.

7. Once you demonize employers, it's natural to (a) look to government for salvation from current ills, and (b) imagine that existing "pro-labor" laws explain why the demons in our lives don't already treat us far worse. This isn't just the root of our secular religion. If you take the demonization of employers and salvation by government literally, you end up with Marxism or something like it.

(9 COMMENTS)

December 20, 2015

Labor Econ Versus the World, by Bryan Caplan

What are these "central tenets of our secular religion" and what's wrong with them?

Tenet #1: The main reason today's workers have a decent standard of living is that government passed a bunch of laws protecting them.

Critique: High worker productivity plus competition between employers is the real reason today's workers have a decent standard of living. In fact, "pro-worker" laws have dire negative side effects for workers, especially unemployment.

Tenet #2: Strict regulation of immigration, especially low-skilled immigration, prevents poverty and inequality.

Critique: Immigration restrictions massively increase the poverty and inequality of the world - and make the average American poorer in the process. Specialization and trade are fountains of wealth, and immigration is just specialization and trade in labor.

Tenet #3: In the modern economy, nothing is more important than education.

Critique: After making obvious corrections for pre-existing ability, completion probability, and such, the return to education is pretty good for strong students, but mediocre or worse for weak students.

Tenet #4: The modern welfare state strikes a wise balance between compassion and efficiency.

Critique: The welfare state primarily helps the old, not the poor - and 19th-century open immigration did far more for the absolutely poor than the welfare state ever has.

Tenet #5: Increasing education levels is good for society.

Critique: Education is mostly signaling; increasing education is a recipe for credential inflation, not prosperity.

Tenet #6: Racial and gender discrimination remains a serious problem, and without government regulation, would still be rampant.

Critique: Unless government requires discrimination, market forces make it a marginal issue at most. Large group differences persist because groups differ largely in productivity.

Tenet #7: Men have treated women poorly throughout history, and it's only thanks to feminism that anything's improved.

Critique: While women in the pre-modern era lived hard lives, so did men. The mating market led to poor outcomes for women because men had very little to offer. Economic growth plus competition in labor and mating markets, not feminism, is the main reason women's lives improved.

Tenet #8: Overpopulation is a terrible social problem.

Critique: The positive externalities of population - especially idea externalities - far outweigh the negative. Reducing population to help the environment is using a sword to kill a mosquito.

Yes, I'm well-aware the most labor economics classes either neglect these points, or strive for "balance." But as far as I'm concerned, most labor economists just aren't doing their job. Their lingering faith in our society's secular religion clouds their judgment - and prevents them from enlightening their students and laying the groundwork for a better future.

(6 COMMENTS)

December 16, 2015

All Politicians Lie: The Empirics, by Bryan Caplan

We don't check absolutely everything a candidate says, but focus on what catches our eyeHere's what they find for today's presidential hopefuls, plus Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

as significant, newsworthy or potentially influential. Our ratings are

also not intended to be statistically representative but to show trends

over time.

[...]

[J]ournalists regularly tell me their media organizations have started

highlighting fact-checking in their reporting because so many people

click on fact-checking stories after a debate or high-profile news

event. Many readers now want fact-checking as part of traditional news

stories as well; they will vocally complain to ombudsmen and readers' representatives when they see news stories repeating discredited factual claims.That's

not to say that fact-checking is a cure-all. Partisan audiences will

savage fact-checks that contradict their views, and that's true of both the right and the left. But "truthiness" can't survive indefinitely in a fact-free vacuum.

I admire the effort. Though partisans will predictably cry foul, I trust Politifact more than partisans. Still, the fact-checking isn't literal enough for my taste. Example: I checked out Obama's "Pants on Fire" lies. This one grabbed me:

"What I have done -- and this is unprecedented ... is I've said to eachPolitifact scores this as "Pants on Fire" because Bush I and Clinton also took this "unprecedented" move.

agency ... 'look at regulations that are already on the books and if

they don't make sense, let's get rid of them.'"

(Obama, 2011)

Dean Baker, a liberal economist and co-director of the Center forWhile I agree that Obama's pants are indeed on fire here, it's not because previous presidents have also tried to eliminate the regulations that "don't make sense." It's because no president has ever earnestly done so. To eliminate senseless regulations, regulators would have to go through existing regs one-by-one, abolishing everything without a solid argument behind it. In legalese, regulations would at minimum have to survive "intermediate scrutiny" in order to stay on the books:

Economic and Policy Research, called Obama's comment a "nonsense claim."

"I would question whether President Obama has done more in re-examining

existing regulations than prior presidents, and if he has I would ask

why he wasted the resources," Baker told us via e-mail. "Whatever it is

called, presidents are always reviewing regulations to eliminate ones

that impose unnecessary burdens."

In fact, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report

on July 16, 2007, states that, "Every president since President Carter

has directed agencies to evaluate or reconsider existing regulations."

In order for a law to pass intermediate scrutiny, it must:

Serve an important government objective, andBe substantially related to achieving the objective.

Still, I don't want to make the best the enemy of the good. Though PolitFact's standards strike me as lax, leading politicians still fall very short of honesty. And that's a fact.

(17 COMMENTS)

December 15, 2015

Assimilation and Immigration Restriction, by Bryan Caplan

I was struck, then, to read Mark Krikorian's Congressional testimony on Syria refugees, because he says precisely the opposite:

While the UN doesn't track the statistic, the likelihood that refugeesI think he's right. Syrian refugees and their children will assimilate to their new and radically different society. But why on Earth would he make this concession? Because in our strange political context, it bolsters his case against immigration. As I explain in "Misanthropy By Numbers":

who've been resettled on the other side of the world will ever move back

is small. It's not just that the physical distance is greater, though

that is a factor. In addition, the acclimation to developed-world

standards of living and norms of behavior and the assimilation of

children into a new and radically different society make it vanishingly

unlikely that those brought here, as opposed to those given succor in

their own region, will ever choose to go home.

The ideal approach, though, is to twist positives into negatives. IfFrustrating, but there is a silver lining. Mark's claims about immigrant assimilation are now on the record. If he ever complains about immigrants' failure to assimilate, we can quote his own words back to him - and ask him to explain the discrepancy. Immigrant assimilation can't be low when high assimilation strengthens the case for immigration AND high when low assimilation strengthens the case for immigration.

the maligned group is hard-working, call them "coolies" or "helots." If

they're respectful, call them "slavish" or "docile." If they're

frugal, call them "greedy" or "cheap." If they raise property values,

say "They're making housing unaffordable." This makes lazy listeners

feel like you've covered all your bases, and deprives your opponents of

their best arguments.

(9 COMMENTS)

December 14, 2015

Demography and Decency, by Bryan Caplan

Truth be told, I think the racism card usually fits. But there's a much better response. Unlike most complaints about immigration, demographic ills can clearly be remedied with more immigration! Non-white immigration is messing up America? Then let in enough white immigrants to keep the white share constant. Non-Christian immigration is destroying our religious heritage? Then let in enough Christians to keep the Christian share constant. Non-Anglophones are turning English into a minority language? Then let in enough English-speakers to balance them out. Low-IQ immigration is making us dumb? Then let in enough high-IQ immigrants to keep up smart.

This is certainly a viable solution given current levels of immigration. The world has hundreds of millions of whites, Christians, English-speakers, and IQs>100. At least tens of millions of each group would love to permanently move to the U.S. Why haven't they? Because it's illegal, of course. If the U.S. selectively opened its borders to these groups, it could reverse decades of demographic change in a matter of years. In fact, the U.S. could admit vastly more Third World immigrants without changing overall demographics a bit - as long as it concurrently welcomed First World immigrants to balance them.

So why not? Most people - perhaps even including some supporters of open borders - will recoil at the thought of pandering to racism. But this puts symbolism over substance. If white and non-white foreigners should be free to move here, opening the doors to white foreigners is a big step in the right direction. Furthermore, nullifying demographic objections to immigration helps keep the door to other kinds of immigration open.

But what about the people who fear demographic change? I could be wrong, but I suspect they too will recoil at my proposal.* Sure, admitting tons of the people they like cures whatever demographic ills they lament. But it raises the status of immigration in general, and fails to put resented out-groups in their place. In other words, they too put symbolism over substance.

People who oppose immigration for demographic reasons will probably object that they're just pursuing the path of least resistance. Cutting the quota for undesirable immigrants is a lot easier than raising the quota for desirable immigrants. But they're wrong. This is a classic Nixon-goes-to-China situation. If die-hard critics of immigration fervently urge, "Let's let in more immigrants from Europe," who will gainsay them? Sure, you could decry the supporters of European immigration as "racists," but the accused suddenly have a great defense: "How so? We support just as much non-white immigration as you do." Imagine if Mark Krikorian, head of the Center for Immigration Studies, had eagerly lobbied to admit all Christian victims of ISIS, instead of predictably looking for an excuse to exclude them. "Even Krikorian says we should let them in" is far more convincing than "Once again, Krikorian says we should keep them out."

Balancing allegedly bad immigration with good immigration is a keyhole solution. It takes anti-immigration arguments at face value, then tries to address them as cheaply and humanely as possible. If demographic shifts frighten you, there is no need to abandon common decency, to lash out at desperate foreigners searching for a better life. Just welcome the immigration we're getting - plus all the extra immigrants required keep our demographics steady.

* There is a prominent lobby for high-skilled immigration, which covertly amounts to lobbying for high-IQ immigration. But prominent proponents of high-skilled immigration almost always rhetorically focus on labor and fiscal effects, not demographics.

(15 COMMENTS)

December 13, 2015

No Plan for What Comes After, by Bryan Caplan

My elder sons got the first four seasons of Game of Thrones for their thirteenth birthday, so I get to watch the whole series again. Season 2, Episode 4 is even more pacifistic than I remember. Crucial scene: Talisa, the battle surgeon, handily exposes the shallowness of the honor of Robb Stark, King in the North.

Talisa: That boy lost his foot

on your orders.

Robb: They killed my father.

Talisa: That boy did?

Robb: The family he fights for.

Talisa: Do you think he's friends

with King Joffrey?

He's a fisherman's son

that grew up near Lannisport. He probably never held a spear

before they shoved one in his

hands a few months ago.

Robb: I have no hatred

for the lad.

Talisa: [sighs]

That should help

his foot grow back.

Robb: You'd have us surrender,

end all this bloodshed. I understand. The country would be at peace

and life would be just

under the righteous hand

of good King Joffrey.

Talisa: - You're going to kill Joffrey?

Robb: If the Gods give me strength.

Talisa: And then what?

Robb: I don't know. We'll go back

to Winterfell. I have no desire to sit

on the Iron Throne.

Talisa: So who will?

Robb:

I don't know.

Talisa: You're fighting

to overthrow a king,

and yet you have no plan

for what comes after?

Robb: First we have

to win the war.

Only fiction? Think again. Robb's a typical politician: too obsessed with winning to dwell on whether the game is morally permissible, much less worth playing.

(7 COMMENTS)

December 10, 2015

The Meaning of Mood, by Bryan Caplan

Tyler Cowen often inveighs against the Fallacy of Mood Affiliation:

It seems to me that people are first

choosing a mood or attitude, and then finding the disparate views which match

to that mood and, to themselves, justifying those views by the mood. I

call this the "fallacy of mood affiliation," and it is one of the most underreported

fallacies in human reasoning. (In the context of economic growth debates,

the underlying mood is often "optimism" or "pessimism" per se and then a bunch

of ought-to-be-independent views fall out from the chosen mood.)

Mood affiliation is indeed a pervasive intellectual problem. But Tyler misses half the story. Yes, the desire to feel any specific mood can lead people into error. At the same time, however, some moods are symptoms of error, and others are symptoms of accuracy.

When someone expresses his views with a calm mood, you consider him more reliable than when he expresses his views with an hysterical mood. We give more credence to someone who discusses alleged war crimes somberly than if he does so flippantly. As far as I can tell, this is justified. One of the main reasons I've never bothered to investigate Holocaust denial is that the Holocaust deniers I've encountered think that genocide is hilarious.

Now consider my favorite passage from Alex Epstein's The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels:

[A] proper reaction to a major danger from fossil fuels would be sorrow. Think about it: If

the energy that runs our civilization has a tragic flaw, that is a

terribly sad thing. It would be even worse, say, than if wireless

technology caused brain cancer. The appropriate attitude would be

gratitude toward the fossil fuel companies for what they had done for

us, combined with recognition that we would have to suffer a lot in the

years ahead, combined with the commitment to the best technologies that I

mentioned earlier [hydro and nuclear].

While Tyler might accuse Epstein of fallacious mood affiliation, Epstein makes a deep point. Namely: A reasonable person who was convinced that fossil fuels posed a major danger would feel a specific package of moods:

1. Sadness that a crucial resource has terrible side effects.

2. Gratitude for all the wonders the resource brought us in the past.

3. Resignation that mankind must forego many of these wonders.

4. Determination to salvage as many wonders as possible by using the best available substitutes for fossil fuels.

When an opponent of fossil fuels evinces none of these moods, it strongly suggests he isn't reasonable. It doesn't mean he's wrong, but we should definitely be suspicious of whatever comes out of his mouth. If virtually every opponent of fossil fuels lacks these moods, similarly, it strongly suggests that the whole movement is unreasonable. It doesn't mean the movement's wrong, but we should definitely be suspicious of its central tenets. The same goes for any other position: You can learn a lot by comparing the mood reasonable proponents would hold to the mood actual proponents do hold.

Of course, if you have the expertise and time to directly evaluate someone's claims, you don't need to use their moods to triangulate their credibility. Then you'd just review the facts and forget the moods. Otherwise, though, mood is a valuable clue. Appropriate mood suggests credibility. Credibility suggests truth. It's a fallible heuristic, but we all use it and we're wise to do so.

Question: What's the best relevant psychological research on the correlation between mood and accuracy?

(15 COMMENTS)

December 9, 2015

The Most Educated Poor in History, by Bryan Caplan

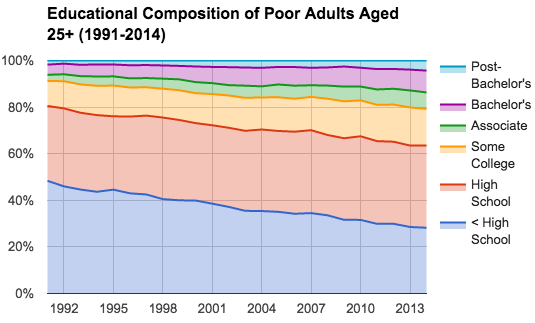

1. "As the adults migrated up the educational bins, they took the poverty into the higher educational bins with them:"

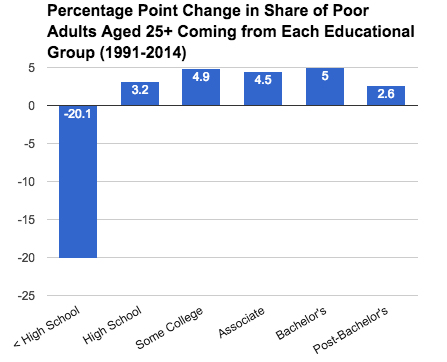

2. "Over this period, the share of poor adults with "less than high

2. "Over this period, the share of poor adults with "less than high school" education plummeted 20.1 points from 48.3 points to 28.2 points.

Every other educational bin saw share gains of 2.6 to 5 points."

In sum:

Diagnosis:Adults these days are as educated as they have ever been, but poverty

is no lower than it was in 1991. This is not because the few lingering

people with "less than high school" have soaked up all the poverty.

Quite the contrary: poverty has simply moved up the educational scale.

The poor in 2014 were the most educated poor in history.

My only caveat is that Matt's first and third points hinge on his second point - which, not coincidentally, is the heart of the book I'm now wrapping up, The Case Against Education . If extra education really did transform people from bad workers into good workers, employers would have a strong incentive to create more good-paying jobs. Profit-maximization, not "magic," would make it happen. The same goes for non-workers. If school sharply increased the productivity of the young, old, disabled, parents, and the unemployed, employers would be more interested in hiring them. These issues wouldn't literally "go away," but employers are a lot more willing to accommodate good workers than bad ones.First, handing out more high school and college

diplomas doesn't magically create more good-paying jobs. When more

credentials are chasing the same number of decent jobs, what you get is

credential inflation: jobs that used to require a high school degree now

require a college degree; jobs that used to require an Associate degree

now require a Bachelor's degree; and so on...

Second, having more education does not necessarily

increase people's productive capacity. Those in the know will identify

this as the old "signaling v. human capital" point. The short of it is

that, even if jobs did automatically pop into existence to match

people's level of productive ability, it's not at all clear that college

education necessarily does a lot to increase people's productive

ability. Instead, what college education does (at least in part) is

signal to employers that you have a certain level of relative "quality"

over others in society. As more people get degrees, the value of this

signal declines, but more importantly, the point is that the degree was

always a signal, not a productivity enhancer.

Third, poverty is really about non-working people:

children, elderly, disabled, students, carers, and the unemployed. The

big things that cause poverty for adults over the age of 25 in a

low-welfare capitalist society--old-age, disability, unemployment, having

children--do not go away just because you have a better degree. These

poverty-inducing circumstances are social constants that could strike

anyone of us and do strike many of us at some point in our lives...

Question for Matt: Are you willing to join me in calling for lower education spending to roll back credential inflation? If not, why not?

HT: Nathaniel Bechhofer

(10 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers