Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 104

February 22, 2016

I Win My Bush-Trump Bet with Tim Kane, by Bryan Caplan

(2 COMMENTS)

February 21, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Concluding Thoughts, by Bryan Caplan

1. If you want to understand why some countries are rich and others are poor, ancestry research is a major advance. Like it or not, countries inhabited by the descendants of relatively economically successful societies tend to remain relatively economically successful today. Transplanting advanced civilizations has proven easier than transforming backwards civilizations.

2. Still, ancestry research has weighty shortcomings. Overall, Europeans have been far more successful than their ancestry predicts. Their SAT scores are mediocre, but European civilization has economically conquered the globe. Ancestry scores don't explain the leading role of the United States, or the lingering poverty of China and India. And you can't credibly dismiss the three most populous countries on Earth as irrelevant "outliers." Any theory that badly fits China, India, and the U.S. has serious problems.

3. In 1950, Asia and Africa were both desperately poor. An ahistorical thinker would therefore expect the two regions to remain in their unfortunate situation. An historical thinker, knowing the two regions' radically different SAT scores, would make a rather different prediction: Asia will regain its former glory, but Africa will stay poor because it has little former glory to regain. Both historically-informed stories have proven strikingly accurate.

4. But: In 1950, an historical thinker would also have predicted the economic resurgence of the Middle East, the cradle of civilization. Oil aside, this didn't remotely happen. For the Middle East, it's the ahistorical thinker who wins, hands down. Given the antiquity of Middle Eastern civilizations and the size of the region, this is a deep failing for ancestry research.

5. As far as I know, Garett is the only thinker who openly uses ancestry research to justify immigration restrictions. It's not clear any of the authors of the papers we covered draw any connection at all. But on the surface, it's the natural interpretation of their results - especially if, like most humans, you're a nationalist at heart. If I were Garett, I wouldn't be swayed by the original researchers' reticence. Hyper-cautiously refusing to explore the broader implications of your research is a classic academic failure - especially if the broader implications offend left-wing sensibilities.

6. Garett is nevertheless deeply mistaken to base his case against low-skilled immigration on ancestry research. Basic fact: The people of the United States are below the world average for both state and agricultural history. The people of Europe are better, but not by that much. As a result, the regressions Garett emphasizes literally predict that open borders will be even more productive than its fans previously calculated.

7. An added problem: ancestry research treats all migration as equivalent. It doesn't matter how national ancestry changes as long as it does. On the surface, though, it's hard to believe that conquest, genocide, transportation of slaves, differential fertility, and what I call "civilized migration" have equivalent long-run cultural effects, holding ancestry constant. When people voluntarily move from backwards to advanced countries to peacefully create new lives for themselves, they typically leap to a new and better equilibrium. The immigrants largely escape the dysfunctional hand of the countries of origin; their children escape it almost entirely.

Garett may call this wishful thinking, but these are hard, happy facts most of have directly experienced - or lived. My wife, for example, migrated from Romania to the United States when she was 7. Culturally, this made her 95% American, and our children 99.5% American. I've see the same transformation in virtually every immigrant family I've ever known - including many hundreds of immigrant students I've taught at GMU. Insisting that their ancestry remains a worrying concern frankly seems silly - even though I expect their home countries to continue on their generally disappointing ancestral trajectories.

8. But what about what Garett calls the "Open Borders Sacrifice" - the possibility that open borders will impoverish your descendants while enriching mankind? For starters, the moral subtext is absurd. Ending state-imposed discrimination against blacks wasn't a "sacrifice" for U.S. whites; it was minimal decency. The same goes for ending state-imposed discrimination against foreigners. Even a moral relativist should appreciate the parallel.

9. Moral subtext aside, though, are Garett's fears credible? Distribution is tricky, but if you buy the ballpark prediction that open borders will double global GDP, its nearly impossible to believe any sizable group will lose on net. Oil consumers may gain more than 100% of the benefit of increased oil production, but that hinges on highly inelastic supply and demand for oil. When migration dramatically increases global production virtually across the board, there is every reason to think the benefits will be broadly shared. Unconvinced? When was the last time a sharp rise in global production made the average American poorer? Non-economists may point to the rise of China, but they'll struggle to find an economist who backs them up.

10.Now that I've finished my intellectual journey through ancestry research, one thing deeply puzzles me: Why did Garett appeal to the power of ancestry, instead of focusing on his own research on national IQ? Convincing people ancient history matters is an uphill battle. And since the ancient history of Americans' ancestors is nothing special, it's a red herring anyway. It would have made a lot more sense for Garett to focus on intelligence, where people of European stock are near the top - a smidge below Eastern Asians - and the people of Latin America, India, Africa, and almost the whole Muslim world do very poorly. Why he didn't take this route to immigration restriction is a great mystery to me. In a few months, perhaps I'll try to solve it.

(2 COMMENTS)

February 19, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Chanda Comments, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan

Thanks for choosing to discuss

our paper and for your positive reaction.

A few observations.

(a) In your view technology is

the most preferable variable followed by population density and urbanization,

with agricultural history and state antiquity coming last. Further, you observe

that technology does "well" in capturing persistence, while your least

preferable variables do the best, with density and urbanization doing worst.

The fact that urbanization and

density may not do as well is, because we believe that they are poorly

measured. Furthermore, for urbanization the small sample size makes matters

worse.

Moving on to the other three

variables, you prefer technology the most but note that your least preferred

variables do better. Having re-examined our results, my own reading is that

technology performs at least as well as, if not better, than state antiquity

and millennia since agriculture. Note that the simple correlations in our

paper indicate that technology, state history and agriculture are very strongly

correlated (compared to their correlations with urbanization and population

density).

I should also clarify that state

history is a "stock" variable that aggregates a measure of the existence of the

state over 50 year periods from 1CE to 1500CE. We apply a 5% decay for past

values. In other words, it is a stronger indicator of the presence of a state

in the centuries closer to 1500, than a 1000 years earlier.

(b) You doubt the Malthusian

theory of limited GDP per capita differences and suggest that slavery is an

indication that living standards are likely to have been above subsistence.

Slavery was not uncommon in pre-industrial times though it did vary by country

or empire. It would be hard to say how much it would be reflected in GDP

per capita differences. If most of the population was still engaged in

livelihoods that only provided a subsistence income, this may not have mattered

so much. In any case, at least indirectly, variations in the existence of

slavery should reflect differences in the power and organization of the state,

or the technology that helped capture and retain slaves. In that sense, I think

variables such as technology and state history are useful measures when GDP per

capita is not available.

Having said, that I now shameless

plug my earlier research with Louis that was published in the Scandinavian

Journal of Economics in 2007. In that paper, we extrapolated GDP per capita in

1500 based on population density and urbanization. Needless to mention, it is

certainly worth exploring further by adding state history and the measure of

technology.

Thanks

again for choosing to cover the series of papers on ancestry and long run development.

(0 COMMENTS)

February 18, 2016

Prove-Me-Wrong Prizes, by Bryan Caplan

The idea is simple. Suppose I claim "Joe Blow cheats on his wife, and I won't pay you a penny if I'm proven wrong." If you have an ounce of common sense, you're dismiss my lame accusation. If however I announce, "Joe Blow cheats on his wife, and if I'm proven wrong according to well-known Arbitrator X, I will pay you $10,000." Now you have a good reason to take me seriously, right?

The main problem with our current libel/slander regime: Pronouncing the solitary sentence, "Joe Blow cheats on his wife," is functionally equivalent to "Joe Blow cheats on his wife, and I won't pay you a penny if I'm proven wrong." But most people don't treat them as functionally equivalent!

Why don't they? Many reasons, but perhaps the most important is that we're not used to Prove-Me-Wrong prizes. If such prizes were common, you'd practically have to offer such prizes to be taken seriously when talking smack. In such a society, vicious lies would primarily discredit the speaker rather than his target.

So why not?

(2 COMMENTS)

February 17, 2016

The Question I Didn't Ask Nate Silver, by Bryan Caplan

In the show Orange Is the New Black, you're named as a living, breathing embodiment of human rationality. Are you? If not, why aren't you?Happy to post Nate's answer if he sees this. :-)

(0 COMMENTS)

February 16, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Chanda, Cook, and Putterman, by Bryan Caplan

The authors data is here.

Summary

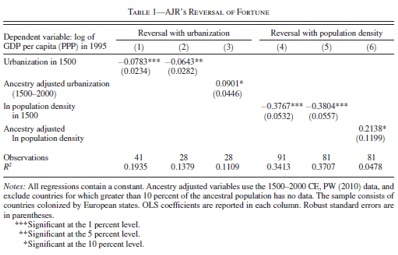

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (AJR) famously argued that the world's former colonies have seen a great "reversal of fortune." On average, the more advanced such countries were in 1500, the poorer they are today. In this week's paper, Chanda, Cook, and Putterman (CCP) argue that AJR omitted a mighty confounding variable: ancestry. While nations' fortunes reversed to some extent, peoples' fortunes persisted. Countries inhabited by the descendants of relatively successful tribes in 1500 remain relatively successful today.

CCP begin by applying the Putterman-Weil World Migration Index to AJR's measures of initial development: urbanization and population density. Ancestry adjustment easily re-reverses AJR's reversal.

Then CCP replace AJR's measures of early development with the "SAT scores" (state history, agricultural history, and technological history) we've seen in earlier installments of this reading club. Unadjusted for ancestry, these measures marginally confirm AJR's reversal; the signs are right, but none are statistically significant. Adjusted for ancestry, all three measures predictably show strong persistence of fortune.

CCP then move on to a host of robustness checks. As usual, geographic controls dramatically cut the measured effect of ancestry. Results for urbanization and population density are fragile, but SAT scores are robust. I leave the multitude of other robustness checks to the reader; clearly the authors wanted to cover their bases.

"Persistence of Fortune" then argues AJR were too quick to claim victory for "institutions" over "human capital" stories of development. The big lesson:

We find no evidence of an important subset of national groups converting themselves from relatively "backward" to relatively "advanced" by adopting better institutions. The AJR (2002) reversal is instead associated with people from places hosting societies that were relatively socially and technologically sophisticated in 1500 migrating to places that had been relatively backward and that accordingly had relatively low population densities (which were further diminished by absence of resistance to Old World diseases). The most straightforward explanation of the reversal of fortune for territories, then, would be that the connecting of "old" (Eurasia plus Africa) with "new" (Americas, Oceania, and other islands) worlds that began in the fifteenth century led to population transfers in which (inter alia) the technological and social advantages of peoples from the most advanced civilizations sank new roots in previously backward lands.Critical Comments

1. This is an extremely convincing piece. AJR's "reversal" evidence was always pretty thin. While CCP are basically able to replicate the reversal, AJR's results are sensitive to mild tweaks. Adjusting all the results for ancestry, in contrast, dramatically changes the picture.

2. Suppose you knew none of AJR or CCP's results. You have five measures of early development: urbanization in 1500, population density in 1500, millennia of agriculture, state history, and technology in 1500. A priori, which measures most credibly capture "initial success" that might or might not be reversed? To my mind, technology in 1500 comes in first, followed by a two-way tie between urbanization and population density. State and agricultural history seem least relevant. If a society was barbarous in antiquity but visibly successful in 1500, poverty in 2000 shows reversal, not persistence.

3. If you buy my ranking, CCP's results are somewhat puzzling. Persistence works well for the best measure (technology), but only slightly for the two runner-ups - urbanization and density. For the least plausible measures, it works best. While it's tempting to paint whatever measures predict most strongly as the "truest" measures of ancestral development, that's not good science.

4. While we're on the subject, none of the papers we've examined try to measure early per-capita GDP or use it to predict modern economic performance. They have a standard theoretical excuse: Early economies were Malthusian, stuck at subsistence, so we shouldn't expect early per-capita GDP to predict current per-capita GDP.

I've long been suspicious of this whole story. First, while no pre-modern societies were rich by our standards, their living standards certainly varied. Second, the very existence of slavery shows human beings earned more than their subsistence since antiquity. There's little point owning a person who eats as much value as he makes. Third, if early per-capita GDP did predict current per-capita GDP, economists would clearly treat this fact as relevant - as they should. By basic Bayesian logic, the alleged failure of early per-capita GDP to predict current per-capita GDP should tip our mental scales in the opposite direction.

Coming up: A general assessment of the ancestry and long-run growth literature, especially as it relates to the case for immigration and open borders, followed by an Ask Me Anything.

(2 COMMENTS)

February 15, 2016

Praise: Substitution versus Income Effects, by Bryan Caplan

Why the chasm? The real story, I suspect, is emotional rather than strategic. Parents praise or withhold because that's what feels right to them. The charitable story, though, is that strategy is central. The two archetypes factually disagree about the effect of praise on performance, and act accordingly.

The pro-praise story: Praise is a form of reward. The greater the rewards of success, the more effort kids exert.

The anti-praise story: Yes, praise is a form of reward. But the more rewards kids rack up, the more satisfied they feel. The more satisfied they feel, the less effort kids exert.

Framed this way, the pro- and anti-praise debate boils down to the intermediate micro analysis of the substitution and income effects. Does paying people more (or taxing them less) make them work more or less? The strange but true answer is: It depends. "The greater the rewards, the greater the effort" makes sense. But so does, "The more rewards you have, the less you crave further rewards." The great "to praise or not to praise" debate fits elegantly into this framework.

Or does it? Consider: Touchy-feel parents also typically avoid shaming their kids. Old-school parents, in contrast, shame freely. Here, then, old-school parents seem to rely on the substitution effect - the greater the cost of bad behavior, the smaller the quantity. Touchy-feely parents, in contrast, seem to tacitly appeal to the income effect: A shamed kid will act even worse because he has so little left to lose.

Personally, my parenting style embraces the substitution effect in both directions. I happily praise good behavior, and sternly (though not angrily) criticize bad behavior. That's definitely more consistent than either of the classic archetypes, and seems to work well for my kids. But perhaps that's an illusion - or an outlier. From a bird's eye view, which view of praise and blame has the facts on its side?

(5 COMMENTS)

February 14, 2016

Hopeless Excuses, by Bryan Caplan

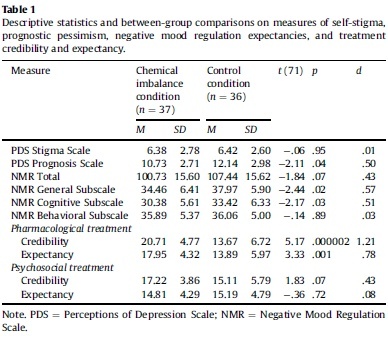

In "Effects of a Chemical Imbalance Causal Explanation on Individuals' Perceptions of Their Depressive Symptoms," (Behavioral Research and Therapy, 2014), Kemp, Lickel, and Deacon run a fascinating on-point experiment. How does belief in the "chemical imbalance" theory of depression actually affect depression? The set-up: Researchers started with a sample of students who had experienced depression, then:

Participants were randomly assigned to the chemical imbalance condition or the control condition. Following informed consent and collection of demographic information, participants were administered the "Rapid Depression Test" (RDT). The RDT was described as a test of neurotransmitter levels whose results would allow participants to determine whether or not their depressive episode(s) were caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain. Participants were led to believe the purpose of the study was to improve understanding of how individuals respond to learning the cause of their depression, before release of the RDT into clinical practice. The test procedure entailed swabbing the inside of the participant's cheek with a sterile cotton swab and placing the cotton swab into a sterile collection container. Next, the experimenter (a male undergraduate research assistant wearing a lab coat) instructed participants that he was leaving the experiment room to take their saliva sample to the lab and run the test. The experimenter returned 10 min later with the condition-specific results of the RDT. In the chemical imbalance condition, participants were informed that test results indicated their current or past depression to be caused by an imbalance in the neurotransmitter serotonin. Participants were presented with a bar graph of their test results (see Fig. 1) depicting very low serotonin levels relative to levels of other neurotransmitters, all of which were in the normal range. In the control condition, participants were told their past/current depression was not the result of a chemical imbalance, based on purported test results (and a corresponding bar graph) indicating that all neurotransmitter levels were in the normative range.Qualitative version of the experimental results:

[C]hemical imbalance test feedback increased prognostic pessimism, lowered negative mood regulation expectancies, and led participants to view pharmacotherapy as more credible and effective than psychotherapy. These effects were not offset by reduced stigma, as chemical imbalance feedback had no effect on self-blame. Overall, the present findings suggest that providing individuals with a chemical imbalance causal explanation for their depressive symptoms does not reduce stigma and activates a host of negative beliefs with the potential to worsen the course of depression and attenuate response to treatment, particularly psychotherapy.

While none of these effects are huge, we shouldn't expect a brief experimental treatment to deeply sway people's psychiatric worldviews. It's entirely plausible, though, that a whole-hearted conversion to the "chemical imbalances" view would do many times the damage ("iatrogenic effects") of a marginal change in the same direction. Intuitively, moreover, the results make sense. Feeling helpless is a high price to pay for feeling blameless.

To repeat, none of this shows the chemical imbalances view is false. But it does show that accusing Szaszian skeptics of lack of empathy for human suffering is unfair. Telling troubled people, "Your bad brain chemistry is beyond your control, it's not your fault" may sound compassionate, but they seem to hear a bleaker message.

(2 COMMENTS)

February 12, 2016

Putterman-Weil Data, by Bryan Caplan

February 11, 2016

Two Fun Facts from Putterman-Weil, by Bryan Caplan

Fact 1: The U.S. does better on both measures than the average country.

For ancestry-adjusted state history, the U.S. scores .57, versus .44 for the average country.

For ancestry-adjusted agriculture, the U.S. scores .59, versus .55 for the average country.

Qualitatively, of course, this is just what Garett has emphasized. Quantitatively, though, it's underwhelming. Americans' historical background is nothing special.

Fact 2: The U.S. does worse on both measures than the world as a whole.

The world's most populous countries - China and India - both outscore the U.S. on both measures. Which made me wonder: What happens if we weight countries' scores by their populations? Results:

For ancestry-adjusted state history, the U.S. scores .57, versus .62 for the world.

For ancestry-adjusted agriculture, the U.S. scores .59, versus .68 for the world.

Yes, by PW's metrics, Americans come from subpar stock. Deal with it.

Now consider: World GDP per capita is about $13,000; U.S. per capita GDP is around $53,000. According to basic arithmetic, if everyone on Earth enjoyed current U.S. per-capita GDP, world GDP would roughly quadruple.

So what? Taken literally, Putterman-Weil predicts that U.S. per-capita GDP would rise if the entire world population - warts and all - immigrated here. World GDP would be more the four times its current height. Personally, I think this is highly unlikely. But if you prefer regressions over common sense, Michael "Double GDP" Clemens look like a pessimist.

(1 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers