Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 102

March 31, 2016

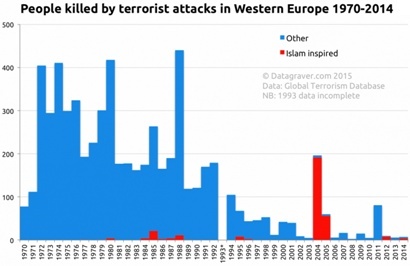

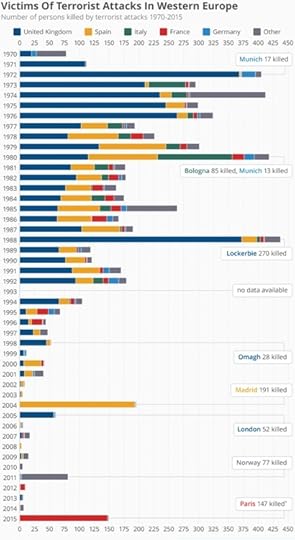

Two Terror Graphs, by Bryan Caplan

From Datagraver:

From Statista:

(8 COMMENTS)

March 30, 2016

The Case Against Education: Forthcoming from Princeton University Press, by Bryan Caplan

(0 COMMENTS)

March 29, 2016

So Far: My Response on Unfriendly AI, by Bryan Caplan

Eliezer Yudkowsky asks: "Well, in the case of Unfriendly AI, I'd ask which of the following statements Bryan Caplan denies." My point-by-point reply:

1. Orthogonality thesis - intelligence can be directed toward anyI agree AIs are not "automatically nice." The other statements are sufficiently jargony I don't know whether I agree, but I assume they're all roughly synonymous.

compact goal; consequentialist means-end reasoning can be deployed to

find means corresponding to a free choice of end; AIs are not

automatically nice; moral internalism is false.

2. Instrumental

convergence - an AI doesn't need to specifically hate you to hurt you; a

paperclip maximizer doesn't hate you but you're made out of atoms that

it can use to make paperclips, so leaving you alive represents an

opportunity cost and a number of foregone paperclips. Similarly,

paperclip maximizers want to self-improve, to perfect material

technology, to gain control of resources, to persuade their programmers

that they're actually quite friendly, to hide their real thoughts from

their programmers via cognitive steganography or similar strategies, to

give no sign of value disalignment until they've achieved near-certainty

of victory from the moment of their first overt strike, etcetera.

Agree.

3. Rapid capability gain and large capability differences - under

scenarios seeming more plausible than not, there's the possibility of

AIs gaining in capability very rapidly, achieving large absolute

differences of capability, or some mixture of the two. (We could try to

keep that possibility non-actualized by a deliberate effort, and that

effort might even be successful, but that's not the same as the avenue

not existing.)

Disagree, at least in spirit. I think Robin Hanson wins his "Foom" debate with Eliezer, and in any case see no reason to believe either of Eliezer's scenarios is plausible. I'll be grateful if we have self-driving cars before my younger son is old enough to drive ten years from now. Why "in spirit"? Because taken literally, I think there's a "possibility" of Eliezer's scenarios in every scenario. Per Tetlock, I wish he'd given an unconditional probability with a time frame to eliminate this ambiguity.

4. 1-3 in combination imply that Unfriendly AI is

a critical Problem-to-be-solved, because AGI is not automatically nice,

by default does things we regard as harmful, and will have avenues

leading up to great intelligence and power.

Disagree. "Not automatically nice" seems like a flimsy reason to worry. Indeed, what creature or group or species is "automatically nice"? Not humanity, that's for sure. To make Eliezer's conclusion follow from his premises, (1) should be replaced with something like:

1'. AIs have a non-trivial chance of being dangerously un-nice.

I do find this plausible, though only because many governments will create un-nice AIs on purpose. But I don't find this any more scary than the current existence of un-nice governments. In fact, given the historic role of human error and passion in nuclear politics, a greater role for AIs makes me a little less worried.

March 28, 2016

So Far: Unfriendly AI Edition, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan Caplan

issued the following challenge, naming Unfriendly AI as one among

several disaster scenarios he thinks is unlikely: "If you're

selectively morbid, though, I'd like to know why the nightmares that

keep you up at night are so much more compelling than the nightmares

that put you to sleep." (http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/.../morbid_thinking_1.html)

Well, in the case of Unfriendly AI, I'd ask which of the following statements Bryan Caplan denies:

1. Orthogonality thesis - intelligence can be directed toward any

compact goal; consequentialist means-end reasoning can be deployed to

find means corresponding to a free choice of end; AIs are not

automatically nice; moral internalism is false.

2. Instrumental

convergence - an AI doesn't need to specifically hate you to hurt you; a

paperclip maximizer doesn't hate you but you're made out of atoms that

it can use to make paperclips, so leaving you alive represents an

opportunity cost and a number of foregone paperclips. Similarly,

paperclip maximizers want to self-improve, to perfect material

technology, to gain control of resources, to persuade their programmers

that they're actually quite friendly, to hide their real thoughts from

their programmers via cognitive steganography or similar strategies, to

give no sign of value disalignment until they've achieved near-certainty

of victory from the moment of their first overt strike, etcetera.

3. Rapid capability gain and large capability differences - under

scenarios seeming more plausible than not, there's the possibility of

AIs gaining in capability very rapidly, achieving large absolute

differences of capability, or some mixture of the two. (We could try to

keep that possibility non-actualized by a deliberate effort, and that

effort might even be successful, but that's not the same as the avenue

not existing.)

4. 1-3 in combination imply that Unfriendly AI is

a critical Problem-to-be-solved, because AGI is not automatically nice,

by default does things we regard as harmful, and will have avenues

leading up to great intelligence and power.

If we get this far

we're already past the pool of comparisons that Bryan Caplan draws to

phenomena like industrialization. If we haven't gotten this far, I want

to know which of 1-4 Caplan thinks is false.

But there are further reasons why the above Problem might be

*difficult* to solve, as opposed to being the sort of thing you can

handle straightforwardly with a moderate effort:

A. Aligning

superhuman AI is hard to solve for the same reason a successful rocket

launch is mostly about having the rocket *not explode*, rather than the

hard part being assembling enough fuel. The stresses, accelerations,

temperature changes, etcetera in a rocket are much more extreme than

they are in engineering a bridge, which means that the customary

practices we use to erect bridges aren't careful enough to make a rocket

not explode. Similarly, dumping the weight of superhuman intelligence

on machine learning practice will make things explode that will not

explode with merely infrahuman stressors.

B. Aligning superhuman

AI is hard for the same reason sending a space probe to Neptune is hard

- you have to get the design right the *first* time, and testing things

on Earth doesn't solve this because the Earth environment isn't quite

the same as the Neptune-transit environment, so having things work on

Earth doesn't guarantee that they'll work in transit to Neptune. You

might be able to upload a software patch after the fact, but only if the

antenna still works to receive the software patch - if a critical

failure occurs, one that prevents further software updates, you can't

just run out and fix things; the probe is already too far above you and

out of your reach. Similarly, if a critical failure occurs in a

sufficiently superhuman intelligence, if the error-recovery mechanism

itself is flawed, it can prevent you from fixing it and will be out of

your reach.

C. And above all, aligning superhuman AI is hard for

similar reasons to cryptography being hard. If you do everything

*right*, the AI won't oppose you intelligently; but if something goes

wrong at any level of abstraction, there may be cognitive powerful

processes seeking out flaws and loopholes in your safety measures. When

you think a goal criterion implies something you want, you may have

failed to see where the real maximum lies. When you try to block one

behavior mode, the next result of the search may be another very similar

behavior mode that you failed to block. This means that safe practice

in this field needs to obey the same kind of mindset as appears in

cryptography, of "Don't roll your own crypto" and "Don't tell me about

the safe systems you've designed, tell me what you've broken if you want

me to respect you" and "Literally anyone can design a code they can't

break themselves, see if other people can break it" and "Nearly all

verbal arguments for why you'll be fine are wrong, try to put it in a

sufficiently crisp form that we can talk math about it" and so on. ( https://arbital.com/p/AI_safety_mindset/ )

And on a meta-level:

D. These problems don't show up in qualitatively the same way when

people are pursuing their immediate incentives to get today's machine

learning systems working today and today's robotic cars not to run over

people. Their immediate incentives don't force them to solve the

bigger, harder long-term problems; and we've seen little abstract

awareness or eagerness to pursue those long-term problems in the absence

of those immediate incentives. We're looking at people trying to solve

a rocket-accelerating cryptographic Neptune probe and who seem to want

to do it using substantially less real caution and effort than normal

engineers apply to making a bridge stay up. Among those who say their

goal is AGI, you will search in vain for any part of their effort that

spends as much effort trying to poke holes in things and foresee what

might go wrong on a technical level, as you would find allocated to the

effort of double-checking an ordinary bridge. There's some noise about

making sure the bridge and its pot o' gold stays in the correct hands,

but none about what strength of steel is required to make the bridge not

fall down and say what does anyone else think about that being the

right quantity of steel and is corrosion a problem too.

So if we

stay on the present track and nothing else changes, then the

straightforward extrapolation is a near-lightspeed spherically expanding

front of self-replicating probes, centered on the former location of

Earth, which converts all reachable galaxies into configurations that we

would regard as being of insignificant value.

On a higher level

of generality, my reply to Bryan Caplan is that, yes, things have gone

well for humanity so far. We can quibble about the Toba eruption and

anthropics and, less quibblingly, ask what would've happened if Vasili

Arkhipov had possessed a hotter temper. But yes, in terms of surface

outcomes, Technology Has Been Good for a nice long time.

But

there has to be *some* level of causally forecasted disaster which

breaks our confidence in that surface generalization. If our telescopes

happened to show a giant asteroid heading toward Earth, we can't expect

the laws of gravity to change in order to preserve a surface

generalization about rising living standards. The fact that every

single year for hundreds of years has been numerically less than 2017

doesn't stop me from expecting that it'll be 2017 next year; deep

generalizations take precedence over surface generalizations. Although

it's a trivial matter by comparison, this is why we think that carbon

dioxide causally raises the temperature (carbon dioxide goes on behaving

as previously generalized) even though we've never seen our local

thermometers go that high before (carbon dioxide behavior is a deeper

generalization than observed thermometer behavior).

In the face

of 123ABCD, I don't think I believe in the surface generalization about

planetary GDP any more than I'd expect the surface generalization about

planetary GDP to change the laws of gravity to ward off an incoming

asteroid. For a lot of other people, obviously, their understanding of

the metaphorical laws of gravity governing AGIs won't feel that crisp

and shouldn't feel that crisp. Even so, 123ABCD should not be *that*

hard to understand in terms of what someone might perhaps be concerned

about, and it should be clear why some people might be legitimately

worried about a causal mechanism that seems like it should by default

have a catastrophic output, regardless of how the soon-to-be-disrupted

surface indicators have behaved over a couple of millennia previously.

2000 years is a pretty short period of time anyway on a cosmic scale,

and the fact that it was all done with human brains ought to make us

less than confident in all the trends continuing neatly past the point

of it not being all human brains. Statistical generalizations about one

barrel are allowed to stop being true when you start taking billiard

balls out of a different barrel.

But to answer Bryan Caplan's

original question, his other possibilities don't give me nightmares

because in those cases I don't have a causal model strongly indicating

that the default outcome is the destruction of everything in our future

light cone. Or to put it slightly differently, if one of Bryan Caplan's

other possibilities leads to the destruction of our future light cone, I

would have needed to learn something very surprising about immigration;

whereas if AGI *doesn't* lead to the destruction of our future

lightcone, then the way people talk and act about the issue in the

future must have changed sharply from its current state, or I must have

been wrong about moral internalism being false, or the Friendly AI

problem must have been far easier than it currently looks, or the theory

of safe machine learning systems that *aren't* superhuman AGIs must

have generalized really surprisingly well to the superhuman regime, or

something else surprising must have occurred to make the galaxies live

happily ever after. I mean, it wouldn't be *extremely* surprising but I

would have needed to learn some new fact I don't currently know.

March 24, 2016

So Far, by Bryan Caplan

1. Industrialization. So far, industrialization has launched mankind from the ubiquitous poverty of the farmer age to the amazing plenty of the modern age.

2. Population growth. So far, population growth has greatly improved living standards by increasing the total number of idea creators, and hence the global rate of innovation.

3. Computers. So far, computers have made human existence not only markedly richer, but much more entertaining.

4. Nuclear physics. So far, nuclear physics has allowed the creation of cheap, clean energy. And it's far from clear that the net body count of the nuclear bomb even exceeds zero. A conventional conquest of Japan probably would have exceeded the body counts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

5. Immigration. So far, immigration - especially from poor countries to rich countries - has lifted hundreds of millions of people and their descendants out of poverty, with no clear harm to host countries' institutions.

Still, in each case, the "so far" proviso sounds ominous. Anyone given to morbid thinking can imagine that these so-far-wonder-working social forces are leading to utter disaster. Let the nightmares begin! Industrialization could lead to environmental apocalypse or global totalitarianism. Population growth could lead to mass famine. Computers could lead to ultra unfriendly Artificial Intelligence - the Terminator scenario. Nuclear physics could lead to all-out nuclear war. Immigration could destroy First World institutions, making the whole world into the Third World.

For the numerate, of course, the mere ability to weave nightmare scenarios is no reason to lift a finger. Probabilities are essential. How can we estimate these probabilities? In practice, most of us pick out a few "serious" nightmares on ideological grounds, and dismiss the rest as too silly to entertain. But that hardly seems like a reliable way to proceed.

How should we ballpark disaster probabilities? Think like superforecasters.

First step: Remember the base rate. Disasters are inherently rare. As I put it a decade ago:

The fact that we've gotten as far as we have shows that true disaster must be extremely rare.Second step: See how long the observed range has lasted. Centuries of success deserve heavy weight.

Unless fears almost always failed to materialize, we'd already be back

in the Stone Age, or plain extinct. It's overwhelmingly unlikely that

we've gotten lucky a million times in a row.

Third step: See how historically prevalent doom-saying about X has been. Why does this matter? Because it measures humans' topic-specific propensity for paranoia. If everyone thought industrialization was fine until ten years ago, we should be more worried than if industrializationphobes started squawking in 1750.

Not good enough? If you're morbid across the board, I've got nothing more to say - though I'm eager bet you. If you're selectively morbid, though, I'd like to know why the nightmares that keep you up at night and so much more compelling than the nightmares that put you to sleep.

(5 COMMENTS)

March 22, 2016

Get a Compound, by Bryan Caplan

On the surface, it's a plausible story. I've always been weirdly individualistic. I never fit in with my classmates or neighborhood kids. Even Princeton's Ph.D. econ program wasn't nerdy enough for me. If you're a lifelong outsider, libertarianism sounds very nice. For everyone else, however, it sounds like a threat to the meaning of life.

The more I think about this story, though, the weaker it seems. The million-dollar question: If people really crave a sense of deep belonging, how come almost no one voluntarily lives in "compounds" - also known as "intentional communities"? If you're a Christian, why not live in an all-Christian apartment block? If you're a Green, why not live in an all-Green commune? If you're an American nationalist, why not live in an all-American-nationalist housing development?

Yes, it's conceivable your restrictive covenants will face some legal hurdles. But where there's a will, there's usually a way. If you want to live on a compound, your main problem isn't that you'll get sued by hostile elements trying to crash your party. Your main problem is that you'll search in vain for like-minded people who want to join you. Indeed, suppose a compound of like-minded people were already up and running. How much extra rent would you be willing to pay per month to experience "deep belonging"?

Critics will probably dismiss this economic reductionism. But that's hardly fair. When people rent apartments or buy homes, they're happy to shell out extra money to live in richer areas, safer areas, more interesting areas. Property developers strive to accommodate not only these common desires, but more obscure preferences for golf communities, 55-and-better communities, pristine communities, and much more. Why then do developers deliver so few deep-belonging communities? The nigh-inescapable answer: Because there's little demand for them. When deciding where to live, psychologically normal humans spend dollars like individualists.

True, most people aren't rhetorically individualistic. But actions speak louder than words. When people talk like collectivists but spend like individualists, Social Desirability Bias is the natural explanation. The prevalence of communitarian talk shows normal people want to sound like communitarians. The absence of compounds shows people want to live like individualists. Governments deliver what people pretend to want. Free markets deliver what they actually want.

Disagree? Then get a compound, raise your identity flag high, and count yourself lucky. Communitarians can get most of the community they lack by by convincing a room-full of like-minded folks to a join them. Individualists can't get the freedom they lack unless they miraculously convince the world's communities to leave them alone.

(7 COMMENTS)

March 20, 2016

My Simplistic Theory of Left and Right, 2016 Edition, by Bryan Caplan

1. Leftists are anti-market. On an emotional level, they're critical ofBut even I'm shocked by how well my simplistic theory fits the 2016 election. On the Republican side, Trump has steamrolled the competition. How? Though his concrete policy proposals are few and fluid, he's expressed minimal interest in free-market ideas. How then has Trump won over the rank-and-file? By doing everything in his power to spite the left: teasing, trolling, ribbing, and scaring feminists, Hispanics, Muslims, protestors, and so on. In a sense, Trump's main campaign promise is to keep liberals awake at night - and he's already fulfilling it.

market outcomes. No matter how good market outcomes are, they can't

bear to say, "Markets have done a great job, who could ask for more?"

2.

Rightists are anti-leftist. On an emotional level, they're critical of

leftists. No matter how much they agree with leftists on an issue,

they can't bear to say, "The left is totally right, it would be churlish

to criticize them."

On the Democratic side, matters are slightly more complicated. Anti-market ideologue Bernie Sanders has pulled anti-market pragmatist Hillary Clinton noticeably to the left, but Hillary's going to win. How does this fit with my view that antipathy toward markets is the driving motive of the left? Because much of Clinton's support is strategic. It's very plausible that 20% of Hillary voters actually prefer Sanders. They're voting for her despite their sympathies because they think she's more likely to win the general election. In contrast, almost no one who prefers Hillary is voting for Sanders because they think he has better prospects in the general election. In polls, the Clinton/Sanders/other breakdown is roughly 50%/40%/10%. So if 20% of Hillary voters and 0% of Sanders voters are strategic, the sincere breakdown is 40%/50%/10%. Sanders really is the soul of the Democratic Party.

And what does Sanders' soul say? Markets are rotten, leading to misery and injustice across the board. Sanders doesn't say that markets do a lot of good, but wise government policy can help them do even better. Instead, he paints lurid pictures of free-market horrors that only government can remedy. His Twitter feed naturally includes a lot of horse-race posts. But on substantive policy, 90% of Sanders tweets are outraged complaints about the evils of the market.* That includes the evils of free international labor markets: "What right-wing people in this country would love is an open-border

policy. Bring in all kinds of people, work for $2 or $3 an hour, that

would be great for them. I don't believe in that." And Sanders has a long history of admiring socialist dictatorships whose only clear accomplishment is suppression of the hated market.

I know plenty of people on left and right with better motives than my simplistic theory predicts. That's to be expected; it is a simplistic theory, after all. But even these noble exceptions tend to sugarcoat the ugly truth instead of admitting their side is sick at heart.

* Yes, I've heard Sanders doesn't fully handle his own Twitter. But I see no reason to think his Twitter comrades are misrepresenting his views.

(6 COMMENTS)

March 17, 2016

The Freedom-Loving Case for Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

Here's my opening statement from Wednesday's Open Borders Debate with Mark Krikorian, sponsored by America's Future Foundation.

Robert Nozick famously criticized

government for forbidding "capitalist acts between consenting adults." If an employer wants to hire you and you want

to work for him, government should leave you alone. If a landlord wants to rent to you and you

want to rent from him, government should leave you alone. The right of consenting individuals to be

left in peace by the government is the heart of freedom. It doesn't matter if the individuals are white

or black, men or women, Christian or atheist; consenting adults of all stripes

have the right to engage in consensual capitalist acts.

The case for open borders begins with a follow-up

question: If race, gender, and religion don't matter here, why should

nationality? Suppose I want to hire a

Chinese citizen to work in my factory, and he wants to work in my factory. Or suppose I want to rent my apartment to a

Romanian citizen, and she wants to accept my offer. It seems like government should leave us alone, too. If it did, open borders - a world where every

non-criminal is free to live and work in any country on earth - would result.

The main principled objection to this

position is that countries are their citizens' collective property. Just as parents can legitimately say, "My

house, my rules," countries can say, "Our house, our rules." Though even many libertarians sympathize with

this argument, it undermines everything they think about human freedom. The idea that countries collectively belong to

their citizens has a name - and the name is socialism. If your dad can mandate, "As long as you live

under my roof, you'll go to church, refrain from swearing, work in my

restaurant, and stay away from that girl I don't like," why can't countries make

comparably intrusive demands "As long as you live within our borders"? Authoritarians may bite this bullet, but

freedom-lovers must reject the premise: America is not the collective property of the American people, but the private

property of American property-owners.

This brings us to the long list of pragmatic objections to open

borders. We're short on time, so I'll

make two sweeping points.

First sweeping point: Immigration

restrictions aren't just another impoverishing trade barrier; they are the

greatest and most impoverishing trade barrier on earth. According to standard estimates, open borders

would roughly DOUBLE the production of mankind by moving human talent from

countries where it languishes to countries where it flourishes. Picture an upscale version of the

migration-fueled economic growth that's modernizing China and India. Every advance hurts someone - see Uber - but open

borders is not trickle-down economics; it's Niagara Falls economics. This enormous increase in wealth - greater

than all other known policy reforms combined - far outweighs almost any

downside of immigration you can imagine - or all of them combined.

Second sweeping point: Immigration

restrictions are not a minor inconvenience we impose on foreigners for the

greater good. To legally relocate to the

United States, you need close relatives, incredible talent, or a winning

lottery ticket. Since every country has

similar policies, almost everyone who "chooses" to be born in the Third World

is stuck there - and being stuck there is very bad. How is their plight our problem? Because without our laws against capitalist

acts between consenting adults, the global poor could pull themselves up by

their own bootstraps in the global labor market.

Freedom-loving people often fret that

immigrants don't love freedom enough to come to the land of the free. They have a point: most immigrants don't love

freedom. But they're missing a larger

point: most native-born Americans don't love freedom either. See the 2016 election if you're in doubt. The real question is, "Do immigrants love

freedom even less than native-born Americans?"

I've seen the data, and the answer is, "Maybe a little, but immigrants

don't vote much anyway." Sometimes

sacrificing a little freedom now brings much greater freedom in the

long-run. But for immigration restrictions,

the opposite is true: They're a never-ending, draconian violation of human

freedom where the long-run payoff is hazy at best.

(2 COMMENTS)

March 16, 2016

Retroactive Krikorianism, by Bryan Caplan

Who should get in? Three types of people:

1. Spouses and minor children of U.S. citizens.

2. "Einsteins." Mark tentatively suggests a minimum IQ of 140, but the core principle is admitting people at the "tops of their fields on the planet."

3. Humanitarian cases, "very strictly limited" - about 50,000 per year.

1. How many of your immigrant ancestors would have met any of the Krikorian Criteria?

Personally, all of my

immigrant ancestors would probably have fallen short; I've

heard they were smart, but no "geniuses." Most of Mark's ancestors wouldn't have made his cut either. You could dismiss this as special pleading, or even a sign of Mark's integrity. But Mark and I are hardly weird cases. I doubt more than 5% of current Americans could honestly claim all their immigrant ancestors would have gained entry under the Krikorian Criteria. Given Mark's rules, then, almost none of us would be here today. Indeed, most Americans have at least one ancestor who would only have been admitted under something approaching open borders.

Next question:

2. Would this country be a better place today if Mark's criteria had kept these immigrant ancestors out?

You could say, "Under Retroactive Krikorianism, far fewer people would enjoy life in the United States. But at least life would be markedly better for the descendants of the original colonists." But the latter clause is hard to believe. Consider: The U.S. has close to the highest standard of living in

the world. It's the center of global innovation. It's the heart of global

culture. It's easy to imagine far fewer people enjoying this bounty, but very hard to imagine that sharply

curtailing immigration would have made the bounty per-person noticeably greater than it already is.

My point: Though the Krikorian Criteria appeal to many Americans looking forward, they would appeal to virtually no American looking backwards. Open borders, in contrast, scares Americans looking forward, even though most of them wouldn't even be here to enjoy America if something close to open borders hadn't prevailed in the past. True, times change.* But it's better to base policy on massive benefits that really happened rather than hypothetical disasters that have failed to materialize for centuries.

Happy Belated Open Borders Day!

* Anti-immigration arguments, in contrast, barely change with the times. How many of the arguments now featured on the CIS website would be any less relevant in 1850 or 1900? At tonight's debate, Mark told me his The New Case Against Immigration spells out the radical differences between historic and modern immigration, but if he really eschewed the timeless complaints about immigration, it would be a very short book.

(7 COMMENTS)

The Glorious Lasting Accidental Liberalization, by Bryan Caplan

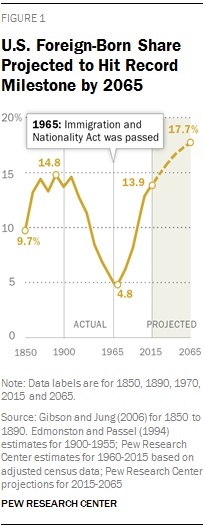

It's hard to believe most Americans in 1965 wanted anything like what happened. So how did this major liberalization come to pass? In A Nation of Nations (highly recommended) Tom Gjelten provides a topsy-turvy play-by-play.

It all started with the Johnson administration's desire to abandon the explicit racism of the old national origins quotas. Wouldn't that lead to lots of non-white migration? No:

Johnson administration officials, however, didn't ask members to set aside their stereotypes and prejudice regarding non-European immigrants. Apparently thinking that such an argument would fall flat, the officials chose to stick with their insistence that changing the criteria for admitting immigrants would have no consequential effect on the ethnic makeup of the immigrant population. In the coming years, when their official predictions were shown to have been wildly inaccurate, a debate arose over whether Johnson administration officials were misleading in their presentations to Congress or simply mistaken.Political cynics like myself naturally assume chicanery. But the plot thickens when nativist Congressman Michael Feighan enters the stage.

By the summer of 1965, the battle to eliminate the national origin quota system was largely won. In the House, Feighan had agreed to support most of the administration's reform proposal, though he insisted on two key changes. First, he wanted a ceiling imposed on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, a provision the Johnson administration opposed as inconsistent with a "good neighbor policy." Second, Feighan wanted to rearrange the "preferences" under which immigrant visas would be distributed. The administration's bill had given priority to visa applicants considered "advantageous" to the nation because of their skills and training, with up to half the available slots reserved for applicants meeting that criterion. Relatives of U.S. citizens and legal residents were next in line under the administrative plan. Feighan wanted to reverse those priorities, with the unification of divided families becoming the top priority. His amended version of the administrative proposal set aside up to three categories for married and unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens... The largest number of visa slots - 24 percent of the total available - would be set aside for brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens, a far more generous allocation for that group than the administration bill provided.What was Feighan up to?

Feighan had for years strongly supported the national origin quota system as a way to preserve the racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. population. Recognizing that the existing quota system was doomed, he concluded that the same demographic result could be achieved by making family unification the paramount goal of U.S. immigration policy. If priority were given to visa applicants whose relatives were already in the United States, he figured, the existing profile of the U.S. population would be unchanged. [emphasis added]Feighan's arguments won over many fellow nativists. The case of the American Legion:

Two Legion representatives, in an article full of praise for Feighan's legislative work, said that by redesigning the administration's immigration reform proposal to emphasize family reunification, he "devised a naturally operating national-origins system." Giving priority to immediate relatives, the Legion representatives argued, would actually bring about the result the quotas were meant to produce. "Nobody is quite so apt to be of the same national origins of our present citizens as are members of their immediate families," the Legion representatives wrote, "and the great bulk of immigrants henceforth will not merely hail from the same parent countries as our present citizens, but will be their closer relatives... Asiatics, having far fewer immediate family members now in the United States than Southern Europe, will automatically arrive in far fewer numbers."As expected, there was some anti-racist pushback:

[Feighan's] argument was so persuasive that some of the fiercest critics of the old national origins approach were dismayed that its hated nationality bias could resurface under the proposed reform. The Japanese American Citizen League pointed out that Asians constituted just one half of one percent of the total U.S. population, so the number of Asians who would qualify for immigrant visas for family unification would be small. "Thus," the league complained, "it would seem that, although the immigration bill eliminated race as a matter of principle, in actual operation immigration will still be controlled by the now discredited national origins system..."But pro-immigration politicians decided to accept Feighan's offer. Perhaps they knew it was a Trojan horse, but Gjelten reports no such sign:

Supporters of immigration reform, including Kennedy and Celler, accepted Feighan's reversal of the preference categories, lowering the number of slots reserved for high-skill applicants and increasing the set-aside for family unification purposes...Punchline:

Perhaps the most important factor explaining [the 1965 Act's] relatively easy passage was that both the immigration reformers and the immigration restrictionists managed to convince themselves and each other that the legislation would not change the immigration picture all that much. In future years, the advocates of tighter immigration controls would look back at the passage of the 1965 Act as a major cause of the immigration wave that followed, with millions of Asians, Africans, Middle Easterners, and Latin Americans moving to the United States. The administration officials who insisted that no such inflow would occur were proved wrong, but they were not alone. Ironically, it was Congressman Michael Feighan, a long-time supporter of the national origins quotas and a close ally of the immigration restrictionists, who was most responsible for opening the United States to more non-European foreigners... Fifty years later, about two thirds of all immigrants entering the United States legally were family members of U.S. citizens or permanent residents, and the 1965 law was even known in some quarters as "the brothers and sisters act."But if all this is true, why has the 1965 Act remained the law of the land decades after its rationale proved false? Institutional and psychological status quo bias.

Institutionally, a simple majority is not enough to overturn the 1965 Act. If the House or the Senate or the President opposes reform, reform doesn't happen. Psychologically, the fact that the 1965 Act is the law of the line inclines fence-straddlers to support it - especially given the mental effort required to grasp the causal chain from family unification to chain migration to non-European migration.

The 1965 Act wasn't just a glorious accidental liberalization; it was a glorious lasting accidental liberalization. As an advocate of open borders, I strive to win hearts and minds. But if history is any guide, maneuvering for another glorious legislative accident could well be the more fruitful approach.

(2 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers