Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 99

May 17, 2016

A Story of Signaling, by Bryan Caplan

Hello,

I am a French journalist living in

London and - more relevant for the purpose of this email - an avid listener of

Econtalk.

I enormously enjoyed all your

appearance on that show and was recently reminded of the last one while re-reading

a passage from the autobiography of the French philosopher Jean-Fran��ois Revel.

This anecdote, I feel, vividly

illustrates your ideas on education as signalling.

A few words of context first: in

1943 Revel, aged 19, was admitted to France's elite Ecole normale sup��rieure.

He also joined a resistance network as a part-time courier. The next

spring the commander of his partisan group urged him to take his end-of-year

exams ("I don't want to be responsible for ruining your

studies.") But by June, the world was collapsing around Revel.

The Nazis had arrested most of the network, and he had to flee to the relative

safety of Lyon.

But he had one last oral exam to

take at the Sorbonne before leaving. To expedite his exit, he left his suitcase

a nearby restaurant (called Capoulade) so that he could head straight to the

Gare de Lyon afterwards.

So on 6 June 1944, he sits down

for his philosophy oral; his examiner, a then-prominent professor named ��tienne

Souriau, asks him: "Is matter capable of thinking?"

"I found it difficult

not to giggle (...) As we were talking, Allied and German forces were

slaughtering each other on Normandy beaches and our future depended on that

battle; Grappin [his partisan commander] and other friends were being

interrogated by the Gestapo; I could hear the distant sound of bombs falling,

probably on Villeneuve-Saint-Georges, a railway hub the Royal Air Force was

destroying every few days (ending all chances of a swift departure for

Lyon). And in those times of tribulation and fear, I was being asked

whether matter was capable of thinking! I succeeded in silencing my own

amusement, summoned all the resources of my verbal and intellectual virtuosity,

and improvised a frenetic monologue in which philosophers were slugging it out,

from Hegel to Democritus, Helvetius, Spinoza, Engels, Empedocles and...

Souriau. For historical objectivity demanded, in an exam, to always

remember to mention the contribution to universal thought made by the maestro

quizzing you (...) In the hours following my summing-up, I successively

picked up a good mark, an honorable mention, and my suitcase at

Capoulade."

(Jean-Fran��ois Revel, Le Voleur dans la maison vide,

Plon, 1997, pp. 117-118)

The signalling nature of Revel's

education is put into stark relief here. The skills he was able to

demonstrate were not just useless in the short term: the act of demonstrating

them increased the risk of catastrophic capture. Yet in the long

run the signalling effect proved effective. Being an alumnus of the ENS

meant being recognised as part of France's intellectual elite; ultimately

his formidable rhetorical talents and encyclopaedic knowledge would earn him

fame.

Incidentally Revel - who died 10

years ago - was France's most pro-American thinker since Tocqueville. He

is the author of Without Marx or Jesus (1970) and Anti-Americanism

(2002).

Regards,

Henri Astier

London

(0 COMMENTS)

May 16, 2016

Price Controls and Economic Literacy: Colonial Edition, by Bryan Caplan

By the end of 1775, Congress had already increased the nation's money supply by 50 percent in less than a year, and state paper issues had already begun in New England. The Congressional Continental bills followed what was to become a sequence all too familiar in the western world: runaway inflation. As paper money issues flooded the market, the dilution of the value of each dollar caused prices in terms of paper money to increase; since this included the prices of gold, silver, and foreign currencies, the value of the paper money declined in comparison to them. As usual, rather than acknowledge the inevitability of this sequence, the partisans of inflationary policies urged further accelerated paper issues to overcome the higher prices and searched for scapegoats to blame for the price rise and depreciation. The favorite scapegoats were merchants and speculators who persisted in doing the only thing they ever do on the market: they followed the push and pull of supply and demand. In another familiar attempt to deal with the problems of inflationary intervention, they outlawed the depreciation of paper, or the rise of prices.The consequences:

State and local governments presumed to know what market prices of the various commodities should be, and laid down price regulations for them. Wage rates, transportation rates, and prices of domestic and imported goods were fixed by local authorities. Refusing to accept paper, accepting them for less than par, charging higher prices than allowed, were made criminal acts, and high penalties were set: they included fines, public exposure, confiscation of goods, tarring and feathering, and banishment from the locality. Merchants were prohibited from speculating, and thereby from bringing the needed scarce goods to the public. Enforcement was imposed by zealots in local and nearby committees, in a despotic version of the revolutionary tradition of government by local committees.What fascinates me, though, is the contemporary intellectual reaction. You'd expect Rothbard, cheerleader for the radical Jeffersonian wing of the American Revolution, to exonerate his team. But he totally doesn't:

Price controls made matters far worse for everyone, especially the hapless Continental Army, since farmers were thereby doubly penalized: they were forced to sell supplies to the army at prices far below the market and they had to accept increasingly worthless Continentals in payment. Hence, they understandably sold their wares elsewhere; in many cases, they went "on strike" against the whole crazy-quilt system by retiring from the market altogether and raising only enough food to feed themselves and their own families. Others reverted to simple barter.

Contrary to a general impression, opinion for or against price controls was determined far more by the state of the person's economic understanding than by his social class, or, for that matter, by his generally conservative or radical views. It is simply not true that radicals favored price controls and conservatives opposed them; the pros and cons cut across both ideological as well as occupational lines. Thus, while the conservative James Wilson denounced price controls in Congress-- "There are certain things, Sir, which absolute power cannot do"--the reactionary Samuel Chase defended controls on the ground of necessity.All of this makes Rothbard's enduring enthusiasm for the American Revolution even more puzzling. Yes, there's all the high-level libertarian rhetoric. But if the American revolutionaries took their rhetoric literally, price controls would have blown their minds. The violation of libertarian principle would have been not only self-evident, but traumatic. The only debate would have been on "wartime necessity" - and that debate would have taken the collateral damage of price ceilings for granted.

Pennsylvania provided the sharpest model of conservative-radical cleavage on this issue. Robert Morris joined Wilson in opposing controls, and the Pennsylvania radicals, in their hatred for these two, were driven to supporting controls. It must be noted, however, that the radical price control leaders included such wealthy and eminent merchants and lawyers as Gen. Daniel Roberdeau, William Bradford, and Owen Biddle. Furthermore, among the radical leaders, Tom Paine, seeing the ill effects of price controls, shifted sharply and permanently in late 1779 from supporting price controls to a strong opposition to them.

Those radicals who favored price controls also justified this sharp deviation from their commitment to liberty and property rights by alleged wartime necessity, much as the Jacobins would do in France over a decade later. Thus, Gen. John Armstrong, a highly respected jurist and engineer and a leading Pennsylvania radical (though an early patron of James Wilson), was the most inveterate and zealous advocate of price controls in Congress. He pleaded that necessity required this exception to the laissez faire rule.

In a sense, the proponents of price controls had no economic arguments. Their views were purely superficial and ad hoc: "Prices are going up, they shouldn't, ergo outlaw price rises," was the argument form. In contrast was the sophisticated economic understanding of the opposition. Leading the opponents of controls was the New Jersey libertarian theorist, the Reverend John Witherspoon. He accurately and prophetically warned Washington that the army's severe price and wage controls on the commodities and services it purchased would only aggravate the shortages and lead to starvation for the army. No man, declared Witherspoon, can be forced to supply goods in the market at prices he considered unreasonable; and his concept of what is reasonable is the price "proportioned to demand on the one side, and the plenty or scarcity of goods on the other." And this price that clears supply and demand can only be set on the market by the voluntary interactions of buyers and sellers, not by any outside politician or government official, it being impossible for any authority to know all the nuances and variations that enter into supply and demand and hence into price. Price control, in fact, could only hobble commerce and thereby make commodities scarce and more costly than ever. The prices of regulated goods, Witherspoon pointed out, had already risen faster than those of the nonregulated.

The moderate Dr. Benjamin Rush was an able student of political economy, and he pointed both to economic theory and to the lessons of economic history. Previous price control efforts had always failed because the true cause of the price rise was not, as the unthinking believed, the wickedness or Tory proclivities of the merchants, monopolizers, or

speculators. The cause, he declared, "was the excessive quantity of our money." Only a decrease in the quantity of money, he pointed out, and a rise in the rate of interest, would end the disastrous price increases, and bring value back to the country's money. John Adams was also highly knowlegeable and forthright in monetary matters, and he too pointed to the historic failures of price controls. As early as 1777, he urged a radical and libertarian cure for the inflation: redeeming notes in gold and silver and ending paper money issue.

The lesson to draw: In the 1700s as today, popular opposition to big government was skin deep at best. Like almost all wars of independence, the American Revolution was fundamentally tribal: "We'll be free when our tribe is ruled by members of our tribe, because that's what freedom is." Even if you embrace the "Liberty or Death" slogan (which you shouldn't), literal liberty was never on the American Revolutionaries' agenda. But as always in war, literal death was.

(1 COMMENTS)

May 13, 2016

The Specter of Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

[T]he specter of truly open borders is such an obvious specter forIndeed, the nativists I've privately and publicly encountered routinely claim we're already in a world of open borders, and insist I'm just a more honest version of Obama or Merkel. As I explained after arguing with Mark Krikorian, head of the Center for Immigration Studies:

nativists to raise that proponents of more liberal immigration laws had

better have something sensible to say about it.

Mark paid me a nice compliment, calling me an "honest man" willing toThe sad reality is that mainstream pro-immigration thinkers favor moving from our current world of 98% closed borders to maybe 97% closed borders. But xenophobia is so rampant that even these tepid reforms sound like the end of the world to at least a quarter of American natives.

unreservedly defend mass immigration. But he paired this compliment

with harsh words for mainstream pro-immigration thinkers. Mark seems to

think that they secretly agree with me, but aren't honest enough to

admit it.

What evidence does Mark have for his conspiratorial

view of his mainstream opponents? None that I've seen. He's just

imputing fanciful hidden motives to people he barely knows. Why

fanciful? Well, I've talked with plenty of mainstream pro-immigration

thinkers. If anything, my presence inclines them to exaggerate their

support for immigration. Still, they're sadly unfamiliar with the case

for open borders, and almost as quick to reject the idea as Mark.

(0 COMMENTS)

Consols Contra the Liquidity Trap, by Bryan Caplan

Step 1: The Treasury refinances the entire national debt with perpetual bonds, better known as consols. As you know, such bonds pay a fixed coupon every year, and never mature. The coupon divided by the asset price equals the interest rate.

Step 2: The central bank uses standard open market operations to bid up the price of consols until nominal GDP starts rising at the desired rate.

Notice: With regular bonds, the difference between 1% interest and .1% interest seems trivial. With consols, it's massive. A fall from 1% to .1% multiplies the sale price of a consol by a factor of ten! There is an even bigger difference between a 1% interest rate and a .01% interest rate. That multiplies the sale price a hundred-fold. Can we really imagine that this massive increase in the public's net worth won't translate into higher consumption and investment? And if not .01%, how about .00001%?

The only limit, as far as I can tell, is that the central bank might inadvertently retire its national debt. When the bond price gets high enough, everyone sells. But this seems like a remote possibility.

If raising nominal GDP despite a liquidity trap is your goal, what's wrong with this approach?

(0 COMMENTS)

May 12, 2016

Emigration and Revolution, by Bryan Caplan

The eminent historian Robert R. Palmer has offered a critically important comparison of the degree of radicalism in the American and French revolutions: the number of emigres who felt compelled to flee the country during the revolution. The French Revolution created 129,000 exiles out of a total population of about 25 million: an emigre ratio of 5 per 1000. The American Tory emigres amounted to what Palmer very conservatively sets at 60,000 in a population of about 2.5 million: 24 emigres per 1,000. But at least half a million of the American population were slaves, who could hardly be considered in the same category as other inhabitants of the colonies. A more likely estimate for Tory emigration in the Revolution is 100,000. At this corrected rate, 50 Americans out of every 1,000 were emigres during the Revolution, a rate fully tenfold of the exile rate in the supposedly more radical French Revolution.I've found discrepancies in Rothbard's historical citations before, but I tracked down his source (Robert Palmer's Age of Democratic Revolutions ) and everything checks out. You could say that moving from the U.S. to Canada was a lot easier than moving from France to any neighboring country, but that's hardly clear. Most obviously, French counter-revolutionaries could move to Belgium without learning a new tongue. And transportation was probably a lot better in France than colonial America. So while it's tempting to dismiss reports of anti-Tory atrocities as isolated incidents, the Tories' emigration rate tells a truly frightening story.

(7 COMMENTS)

May 10, 2016

The Observational/RCT Correlation, by Bryan Caplan

(3 COMMENTS)

May 9, 2016

Dementia, Antihistamines, and Cost-Benefit Analysis, by Bryan Caplan

Despite my generic skepticism of the media's coverage of science, I realized that if anyone was at risk, it was me. Now that I've finished the penultimate version of The Case Against Education , I decided to track down the original research. Here's the full text of Gray et al.'s "Cumulative Use of Strong Anticholinergics and Incident Dementia" (JAMA Internal Medicine, 2015), and here's the technical appendix. (All notes omitted).

Where the data come from:

This population-based prospective cohort study was conducted withinMeasuring dementia:

Group Health (GH), an integrated health-care delivery system in the

northwest US. Participants were from the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT)

study and details about study procedures have been detailed elsewhere.

Briefly, study participants aged 65 years and older were randomly

sampled from Seattle-area GH members. Participants with dementia were

excluded... Participants were assessed at study entry and

returned biennially to evaluate cognitive function and collect

demographic characteristics, medical history, health behaviors and

health status. The current study sample was limited to participants with

at least 10 years of GH health plan enrollment prior to study entry to

permit sufficient and equal ascertainment of cumulative anticholinergic

exposure... Of the 4,724 participants enrolled in ACT, 3,434 were eligible

for the current study...

The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) was used to screenMeasuring drug use:

for dementia at study entry and each biennial study visit.

CASI scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better

cognitive performance. Participants with CASI scores of 85 or less

(sensitivity 96.5%; specificity 92%)

underwent a standardized dementia diagnostic evaluation, including a

physical and neurological examination by a study neurologist,

geriatrician or internist, and a battery of neuropsychological testing.

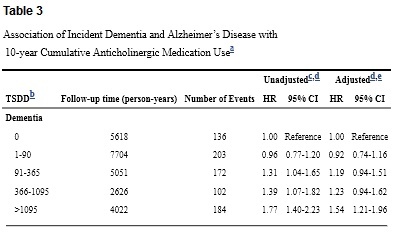

Here are the results for all-cause dementia, both raw and adjusted for cohort, age, sex, education, BMI, smoking, exercise, self-rated health, and a bunch of specific ailments. HR is the risk ratio; 1.31 indicates 31% elevated risk.Medication use was ascertained from GH

To create our

computerized pharmacy dispensing data that included drug name, strength,

route of administration, date dispensed, and amount dispensed for each

drug. Anticholinergic use was defined as those medications deemed to

have strong anticholinergic activity as per consensus by an expert panel

of health care professionals...

exposure measures, we first calculated the total medication dose for

each prescription fill by multiplying the tablet strength by the number

of tablets dispensed. This product was then converted to a standardized

daily dose (SDD) by dividing by the minimum effective dose per day

recommended for use in older adults according to a well-respected

geriatric pharmacy reference (eTable 1). For each participant, we summed the SDD for all anticholinergic

pharmacy fills during the exposure period to create a cumulative total

standardized daily dose (TSDD).

Overall, this is an impressive study. Yes, it only looks at seniors. Yes, there's potential reverse causation. Yes, there are wide confidence intervals. But as far as observational studies go, it would be hard to do much better. And at least for me, the results are scary. Daily use for 3 out of 10 years puts you in the top category, with dementia risk elevated by over 50%.

As an economist as well as a Gigerenzer fan, I'm know risk ratios are a poor guide to action. I'd gladly increase my risk of being struck by lightning by 54% in exchange for one good ice cream cone. Why? Because the normal risk of being struck by lightning is minuscule. For dementia, sadly, the opposite is true. Almost one-quarter of seniors in the study ended up with dementia. But what about those big confidence intervals? They show the

danger could be much lower or much higher, but that's all. The high

point estimates remain a reasonable guide to action.

Many will respond, "So you're pretty likely to get dementia either way," but that's terrible economic reasoning. Raising the risk of losing your mind by roughly 10 percentage-points is awful - regardless of whether you're raising the risk from 0% to 10%, 20% to 30%, or 90% to 100%. See the Allais Paradox if you're still in doubt.

My two main initial doubts about the study:

1. While the authors brag about their dose-response function, it's none too neat. The point estimates for low doses are negative. The point estimates for moderate doses - 95-1095 doses - are almost flat. Only the top category features a big jump. And what's the point of these discrete categories, anyway? Why not log dosage (or dosage +1 so non-users remain in the sample), or include linear and quadratic terms? (If anyone gets the data and runs these regressions, I'll gladly blog the results).

2. While this seems a high-quality study, publication bias is endemic; dramatic results sell. So I suspect the true effects are markedly smaller than the reported coefficients.

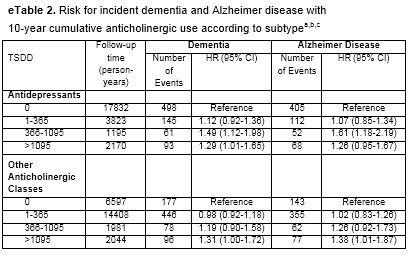

Reviewing the technical appendices added to my doubts. Splitting the results between antidepressants and all other anticholinigerics matters greatly. (Table reformatted for readability; all results adjusted for aforementioned controls).

With this partition, moderate use of antidepressants looks less dangerous than heavy use. And other anticholinergics just look notably safer than in the baseline results.

Patterns in eTable 5, which sub-divides results for past, recent, and continuous users, are also odd. You'd expect continuous users to do the worst, but they actually do the best. Confidence intervals are large, but still.

Given everything I've learned, what will I do? I definitely won't return to my early decades of hellish allergies. Popular write-ups advise switching to second-generation drugs like Claritin. But, Claritin seems ineffective for me - and the research I've seen leaves its side effects unassessed.

Instead of doing anything drastic, I'm applying marginal thinking. Since serious effects aren't evident at high doses, I'm cutting back - testing how low I can go without distress. Now that early spring is over, I'm almost asymptomatic without using any antihistamines at all. My tentative plan, then, is to limit my use to the worst allergy weeks of the year. If you've got better advice, please share.

P.S. Shouldn't a Szaszian deny the reality of dementia? No. As I've often explained, Szaszianism is best interpreted as an empirical claim. The best way to delimit its applicability is measuring responsiveness to incentives:

The distinction between constraints andLike mental retardation, and unlike alcoholism and symptoms of personality disorder, dementia seems highly unresponsive to incentives. So while I have zero worry of suddenly becoming an alcoholic, dementia really could happen to me. And I really don't want it to...

preferences suggests an illuminating test for ambiguous cases: Can

we change a person's behavior purely by changing his incentives?

If we can, it follows that the person was able to act differently all

along, but preferred not to; his condition is a matter of preference,

not constraint. I will refer to this as the 'Gun-to-the-Head Test'. If

suddenly pointing a gun at alcoholics induces them to stop drinking,

then evidently sober behavior was in their choice set all along.

Conversely, if a gun-to-the-head fails to change a person's behavior,

it is highly likely (though not necessarily true) that you are literally

asking the impossible.

(2 COMMENTS)

May 5, 2016

The Value of History, by Bryan Caplan

But that's hardly the whole story. After all, we could have done other A.P.s instead. So why history? To be blunt: While I think history is a waste of time for 99% of people, I think my sons are in the other 1%. They aren't just highly intelligent; they're good students. More specifically:

1. Unlike almost everyone, my sons are interested in being social scientists. And while the historically ignorant certainly can succeed in social science, you can't be a good social scientist without broad, deep historical knowledge. Can't!

2. As you age, you lose your ability to master and retain large bodies of facts. The best way to durably learn history - a like foreign language - is to learn is young. I acquired 90% of my historical knowledge between the ages of 10 and 20. So age 13 seems like an ideal time for this task.

3. Unlike almost everyone, my sons genuinely enjoy learning about history. (I was the same way). As I've argued elsewhere, this is the crucial ingredient that transforms otherwise useless learning into a merit good.

4. The APUSH is a fantastic exam. If a test can teach a person "how to think," the APUSH is such a test. If you've got 195 minutes to spare, take it.

5. To be honest, I'm not convinced any test actually can teach anyone how to think. That's why #4 says If. Nevertheless, I am convinced that people who will ultimately learn how to think can learn how to think sooner. How? By practicing intellectually demanding tasks. Since my sons are in the select category of people who will ultimately learn how to think, I have sped them toward their potential.

Is this all delusional nepotism? Normally, I'd offer to bet, but not here. However they actually do on the test, I am immensely proud of my boys. End of story.

(1 COMMENTS)

May 4, 2016

Lip Service, by Bryan Caplan

I agree that most individualists are psychologically oblivious. But so is almost everyone. The problem is not individualists, but psychology. The replication crisis notwithstanding, psychology is a tough and subtle subject. We can't directly observe anyone's psychology but our own - and our self-descriptions are corrupted by our desire to impress others. Each person's intimate familiarity with his own psychology helps, but also misleads because we're so quick to generalize from our person to all mankind.

Assertions about humans' intense craving for community and belonging are a case in point. The surface problem: The humans who energetically defend these claims tend to be exceptionally communitarian. That's why they're so outspoken on the topic. The fundamental problem, though, is that "community" and "belonging" sound good, leading to rampant lip service.

How can I say that? By noting the stark contrast between how much people say they care about community, and how lackadaisically they try to fulfill their announced desire. I've long been shocked by the fraction of people who call themselves "religious" who can't even bother to attend a weekly ceremony or speak a daily prayer. But religious devotion is fervent compared to secular communitarian devotion. How many self-styled communitarians have the energy to attend a weekly patriotic or ethnic meeting? To spend a few hours a week watching patriotic or ethnically-themed television and movies? To utter a daily toast to their nation or people? Indeed, only a tiny percentage of people who claim to love community find the time for communitarian slacktivism.

You could argue that coordination costs explain the curious shortage of intentional communities. But nothing stops secular communitarians from matching the time commitment of suburban Catholics. Well, nothing but their own apathy.

The lesson: While individualists do tend to neglect mankind's craving for community, they err on the side of truth. Actions really do speak louder than words. And actions reveal that people are far less communitarian than they claim.

(4 COMMENTS)

May 2, 2016

Exploring the Place Premium, by Bryan Caplan

[I]nformation is available to form reasonable qualitative priors about the fraction of the place premium that arises from policy barriers. To begin with, most people outside the United States are prohibited by default from entering the country and working there unless they acquire a special license from the federal government, a visa. This includes citizens of all 42 countries we study. Such policy barriers have large effects on migration flows... Many U.S. visas are tightly rationed, with waiting periods measured in decades. The United States government spends more on enforcing its immigration restrictions than it spends on all other principal federal law-enforcement agencies combined--including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (Meissner et al. 2013, p. 22)... These suggest a reasonable starting prior that the fraction of the wage gap R related to policy is nonzero, even substantial.Not do-able, but:

An ideal natural experiment to isolate policy costs would require countries that are highly similar to the 42 countries studied above, but do not face policy barriers on U.S. immigration. There are no areas so similar in all other respects as to allow precise decomposition of the 'policy' portion and 'natural' portion of the place premium.

There do exist territories free of policy barriers that are nevertheless similar in some respects to foreign countries. People from Puerto Rico and Guam hold U.S. citizenship and can live and work at will to any part of the United States. It is illustrative to estimate Rc for these territories.Bottom line: Contrary to friends of immigration restrictions, enforcement is already draconian. Contrary to enemies of immigration restrictions, existing laws "work" in the sense that they drastically reduce migration.

Table 8 carries out the same exercise in Table 1 for Puerto Rico and Guam... The estimates of Rc for these areas without policy barriers lie in the range 1.3-1.5, substantially above unity... But Puerto Rico and Guam are not exceptional. It is difficult to find labor markets anywhere on earth that sustain real wage differentials Rc much above 1.5 across geographic areas in the absence of policy restrictions on migration. Kennan and Walker (2011, p. 245- 6) find that by age 34, men who are free to migrate between U.S. states have exhibited a "home premium" disutility of migration that would typically be offset if their wage in destination states were higher by a factor of 1.14. Burda (1995, p. 3) finds that Rc between West Germany and East Germany collapsed to 1.3 in the years after policy barriers to migration were eliminated and migration flows spiked. Real wage differentials between metropolitan France and French overseas departments/territories, which exhibit no policy barriers to migration, fall in the range 1.2-1.4.

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers