Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 97

June 26, 2016

Outline for Poverty: Who To Blame, by Bryan Caplan

Since I've yet to start seriously reading for this project, much less writing, the time is especially ripe for constructive criticism and reading recommendations...

(4 COMMENTS)

June 24, 2016

Hanson's Predictions: A 5-Page Age of Em Robustness Test, by Bryan Caplan

p.189:

We have many reasons to expect an em economy to grow much faster than does our economy today. As mentioned in Chapter 13 , Competition section, the em economy should be more competitive in the sense of more aggressively and more easily replacing low-efficiency items and arrangements with higher-efficiency versions.Seems reasonable. Indeed, if I'm correct to think ems will be "robot-like," this just makes Robin even more right. As I've stated, however, I interpret "much faster" to be a few extra percentage-points of growth per year, not a monthly doubling time.

Reduced product variety and spatial segmentation of markets help innovations to spread more quickly across the economy.With robot-like ems and fabulously wealthy humans, I'd expect the opposite: more variety, more spatial segmentation as the typical human enjoys global travel and multiple residences.

Stronger urban concentration should also help promote innovation (Carlino and Kerr 2014).In an em world, it's not clear what even counts as urban concentration in the relevant sense.

The fact that more productive em work teams can be copied as a whole should make it much easier for more productive em firms and establishments to rapidly displace less productive firms and establishments.Agree.

Most of the research that aids innovation is "applied" as opposed to "basic" research. Thus we expect most of this better and faster em innovation to consist of many small innovations that arise in the context of application and practice.If, as Robin argues, ems are based on a small number of humans, why wouldn't we expect this pattern to reverse due to the homogeneity of the innovators?

p.216:

An em economy might further reduce the costs of crime and disease, and increase the gains from innovation. After all, well-designed computers can be secure from theft, assault, and disease.On standard human definitions of "theft, assault, and disease," this makes sense. But why should we think ems are less vulnerable to the cyber-analogs of these problems than humans are to the conventional versions? Why couldn't computer viruses bedevil ems as germs bedevil us?

More important, traffic congestion costs could be much lower in an em city because most transport of ems could be done via communication lines, and most virtual meetings within a city do not require the movement of em minds at all. As congestion costs now limit city sizes, this increase in virtual meetings could plausibly tip the balance toward much larger em cities.Telecommuting hasn't done much on this front so far. So why think ems will lead to "much larger" em cities? Furthermore, doesn't being a virtual being vitiate most of the social reasons to live near others?

Thus instead of today's equal distribution of people across all feasible city sizes, most ems might instead be found in a few very large cities. Most ems might live in a handful of huge dense cities, or perhaps even just one gigantic city. If this happened, nations and cities would merge; there would be only a few huge nations that mattered.With robot-like ems, this might lead to free-trade zones, but not national mergers. This is especially true if, as Robin claims, the Age of Em only lasts a couples of years.

Larger em cities could allow great increases in social complexity.Very vague, but ok.

p.241:

Similarly, mass-market ems can be comforted to know that most disturbing life events were part of the clan's plan.If I'm right, ems will primarily be "distubed" by doing a bad job for their human creators, not by "life events."

When an em clan supplies workers to a very large mass labor market, there must be at least as many members of that clan as there are workers who serve that labor market, times the market share of that clan. Because this number will sometimes be larger than the total number of members in a small clan, clans who supply very large labor markets must also be large. This may create a correlation between clan size and mass-market work; larger clans may tend more to supply mass labor markets, while smaller clans more often serve niche labor markets.If ems are robot-like, I don't see why they would form into "clans" in the first place. They'll be part of their human owners' teams, not their own.

While ems that serve mass markets could more easily be copied as a part of large teams that retain most of their familiar friends and context, such copied teams could not as easily bring along copies of large shared community spaces such as city neighborhoods or parks. For very large spaces this is not a problem, as the different copies of the team can just share the same original space, and only rarely meet in the large space. For smaller spaces, however, ems must choose between moving to a new "parallel world" space, which can of course still look a lot like the old space, or sharing the old space and dealing with the prospect of meeting more often and mixing with similar members of other teams.I think I'd have to read a lot of background information just to know what this means.

In sum, the lives of both mass-market and niche-market ems differ substantially from our lives, but in different ways.Very vague, but ok.

p.304:

Ems from large clans should be less aware of, and feel more secure in their identifying with a personal combination of personality, style, and early life history. They know there is in effect a whole "planet" out there of perhaps billions of ems just like them, "super-twins" to whom they can talk at any time, or ask for help. Thus when around ems from other clans, ems might feel more like expatriates, that is, emissaries from a foreign land.If ems are robot-like, they'll identify primarily with the owners' interests, and simply won't have a lot of "personality" in a human sense.

As discussed in Chapter 19, Managing Clans section, ems who made a plan and then split into many copies to execute that plan are likely to feel that they and their copies are the "same" person, while copies who openly disagree with each other are likely to see themselves more as different people. In an attempt to unify their members, clans may discourage open disagreement, focus more on the fact that they have a shared mental style and shared memories of early life, and focus less on recent opinions and memories. After all, those recent opinions and memories often differ.Again, in my scenario I see little role for em disagreement or self-organization.

When doing physical jobs, ems could use interchangeable bodies. Virtual ems could also easily change their virtual bodies at any time. Thus em identities need tie less to details of a particular body. However, to create a vivid memorable identity that is easily remembered by other clans, each clan may still create and stick close to a consistent visual style.See above.

People today stay loyal to product brands over surprisingly long periods (Bronnenberg et al. 2012). This weakly suggests that ems will also stay loyal to brands for long times. Brand owners are eager to offer deep discounts to young ems with promising futures. While the em world has few children, each child has on average a great many descendants. On the other hand, collective purchasing by clans makes for better-informed consumers, and such consumers tend to have a weaker attachment to brands (Bronnenberg et al. 2014).Very vague, but ok.

Today, our physical illnesses give us excuses to escape social pressures and expectations. If we don't want to do something, we can pretend to be sick. Ems, who never get physically sick, lack this excuse. Perhaps ems will expand their expectations of temporary mental illness to compensate.Given Robin's discussion of "software rot," I'm puzzled by these claims. In any case, robot-like ems won't be inclined to make excuses for anything.

p.336:

Because ordinary humans originally owned everything from which the em economy arose, as a group they could retain substantial wealth in the new era. Humans could own real estate, stocks, bonds, patents, etc. Thus a reasonable hope is that ordinary humans become the retirees of this new world. We don't today kill all the retirees in our world, and then take all their stuff, in part because such actions would threaten the stability of the legal, financial, and political world on which we all rely, and in part because we have many direct social ties to retirees. Yes we humans all expect to retire today, while ems don't expect to become human, but em retirees are vulnerable in similar ways to humans. So ems may be reluctant to expropriate or exterminate ordinary humans if ems rely on the same or closely interconnected legal, financial, and political systems as humans, and if ems retain many direct social ties to ordinary humans.As my earlier critique explained, Robin's analysis strongly suggests this amicable human-em relationship will end in an objective year or two. With robot-like ems, however, it's basically right.

Few ordinary humans can earn wages in competition with em workers, at least when serving em customers. The main options for humans to earn wages are in direct service to other humans. Thus individual ordinary humans without non-wage assets, thieving abilities, private charity, or government transfers are likely to starve, as have people throughout history who lacked useful assets, abilities, allies, or benefactors.Agree.

In our world, financial redistribution based on individual income has the potential problem of discouraging efforts to earn income, and thereby reduce the total size of the "pie" available to redistribute. In an em economy, however, where most all humans are retired, this problem goes away; there are fewer incentive problems resulting from financial redistribution between retired humans.In Robin's scenario, I don't see why humans wouldn't tax ems, leading to standard disincentive effects (or perhaps non-standard Malthusian effects).

Ordinary humans are mostly outsiders to the em economy. While they can talk with ems by email or phone, and meet with ems in virtual reality, all these interactions have to take place at ordinary human speed, which is far slower than typical em speeds. Ordinary humans can watch recordings of selected fast em events, but not participate in them.Do CEOs "participate" in their firms? Of course; though they don't have time to follow the details, they're ultimately in control. I've argued the same holds for humans in the Age of Em.

Although the total wealth of humans remains substantial, and grows rapidly, it eventually becomes only a small fraction of the total wealth, because of human incompetence, impatience, inattention, and inefficiency. Being less able than ems, humans choose worse investments. Being more impatient, they spend a larger fraction of their investment income on consumption.In my scenario, humans hold 100% of wealth regardless of their incompetence, impatience, inattention, and inefficiency. Humans own ems, ems own nothing.

Is Robin really wrong 90% or more of the time? I don't know quite how to score this five-page dissection, but I'm open to readers' suggestions. After performing this exercise, I'm more inclined to say Robin's only 80% wrong. By any measure, however, his forecast accuracy seems low. My main complaint is that his premises about em motivation are implausible and crucial. But in several cases his reasoning from his own premises seems shaky as well.

(0 COMMENTS)

Brexit Bet Comment, by Bryan Caplan

(5 COMMENTS)

June 22, 2016

Ancestry, Long-Run Growth, and Population-Weighting, by Bryan Caplan

Instead of looking at the long-run effects of places' traits, they look at the long-run effect of tribes'The more I explored this paper, however, the more I realize that the world's three most populous countries - China, India, and the United States - are big outliers. The people of China and India have great scores for state history and agriculture, but remain poor. The people of the United States have mediocre scores for state history and agriculture, but remain rich. If these three outliers were Grenada, Slovakia, and Botswana, I wouldn't demur; outliers have ye always. But the fact that the three countries with the most people manifestly deviate from Putterman-Weil is troubling to say the least.

traits. They focus on two measures: state history and years of

agriculture. State history measures how long a country "had a

supratribal government, the geographic scope of that government, and

whether that government was indigenous or by an outside power."

Following previous work, they massage this measure: "The version used by

us, as in Chanda and Putterman (2005, 2007), considers state history

for the fifteen centuries to 1500, and discounts the past, reducing the

weight on each half century before 1451-1500 by an additional 5%."

Years of agriculture, in contrast, is not massaged. It's simply the

"the number of millennia since a country transitioned from hunting and

gathering to agriculture."

[...]

Now for the punchline: Migration-adjusted measures are much more

predictive of modern GDP than raw measures. "Not surprisingly, given

previous work, the tests suggest significant predictive power for the

unadjusted variables. However, for both measures of early development,

adjusting for migration produces a very large increase in explanatory

power. In the case of statehist, R2 goes from .06 to .22, whereas in the

case of agyears it goes from .08 to .24. The coefficients on the

measures of early development are also much larger using the adjusted

than the unadjusted values."

The obvious remedy, as my last post explained, is to run a weighted regression, to place heavier weight on more populous countries, and lighter weight on less populous countries. GMU econ prodigy Nathaniel Bechhofer volunteered to do all the legwork, and David Weil confirmed the accuracy of his output. Specifically, Bechhofer did the following for Putterman-Weil's Table 4, columns (2) and (6).

1. Replicate the original results.

2. Re-do the original specifications with year-2000 population weights.*

You can access Bechhofer's unabridged results here, here, and here. For now, though, let's walk through the basic findings.

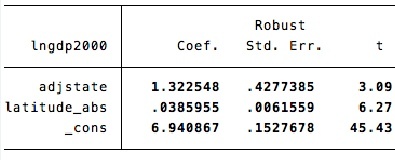

Putterman-Weil's original output for the effect of ancestral state history and absolute latitude on modern per-capita GDP:

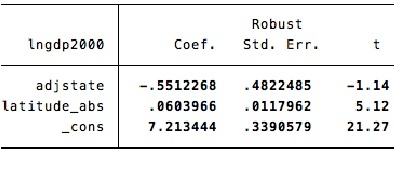

The same output, with countries weighted by population:

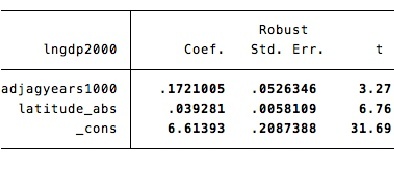

Putterman-Weil's original output for the effect of ancestral agriculture and absolute latitude on modern per-capita GDP:

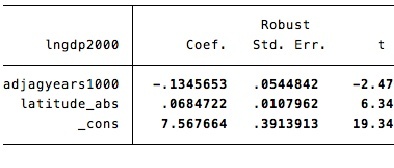

The same output, with countries weighted by population:

In both cases, the original coefficients imply huge positive effects of ancestral development on modern living standards. And in both cases, these huge coefficients actually turn negative after weighting for population. For agricultural history, a large statistically significant positive effect transmutes into a large statistically significant negative effect. Reviewing all of Bechhofer's results, the signs on ancestral development are not uniformly negative, but Putterman-Weil's dramatic positive results never re-emerge.

In stark contrast, the measured effects of sheer geography withstand population-weighting with ease. Absolute latitude continues to have a huge positive effect. So, to a slightly lesser extent, does being land-locked. (See the unabridged results).

What does this all mean? At minimum, the apparent effects of ancestral development on modern living standards are not robust. They don't proverbially "leap out of the data"; they hinge on the debatable assumption that every country on Earth, no matter how small, is equally informative about the causes of economic development.

Personally, I'd go further: Despite its ubiquity in growth regressions, the equal-weighting assumption is silly. China, India, and the United States obviously teach us more about human societies than Grenada, Slovakia, or Botswana. And what they teach us is that ancestral greatness is not vital for modern prosperity.

* Bechhofer also tried year-1500 population weights, with very similar results.

(1 COMMENTS)

June 19, 2016

Cross-Country Regressions and Population Weighting, by Bryan Caplan

Is my intuition econometrically sound? Bill Dickens, my Econ 1 teacher, has a paper subtitled "Is It Ever Worth Weighting" (Review of Economics and Statistics, 1990) - and originally subtitled "Why It's Never Worth Weighting." This apparent absolutism prompted me to send Bill the following hypothetical:

Someone is doing a cross-country regression, counting

each member of the European Union as a single data point. A critic says,

"Bill Dickens showed that it is never worth weighting. We should just

treat the whole EU as one data point despite its huge population."

In your framework, how is the critic wrong? Why then

wouldn't he be arguably wrong for any large, diverse country?

In conversation, Bill's response was modest: His paper only addressed a very different rationale for population weighting. For cross-country regressions, population weighting might be entirely suitable.

Last year, Solon et al. published a more comprehensive piece on the topic, entitled "What Are We Weighting For?" (Journal of Human Resources, 2015). While they raise multiple technical issues, their advise is straightforward: When population-weighting matters, researchers should alert their readers and reflect on the source of the contrast.

[W]e recommend reporting both the weighted and unweighted estimates because the contrast serves as a useful joint test against model misspecification and/or misunderstanding of the sampling process.

Who cares? Early this year, I spent weeks reviewing research on ancestry and economic performance. In this research, the three most populous countries on Earth - China, India, and the United States - are major outliers.

This led me to wonder, "What would happen if we weight the results by population?," but I felt the need to review the econometrics first. Since it now looks like population-weighting is technically acceptable as well as intuitively plausible, I'm now ready to share the results. What's the bottom line? Stay tuned.

(0 COMMENTS)June 15, 2016

My Answers for Robin, by Bryan Caplan

Relative to tenured professors of social science who were hypotheticallyMy answer: If you want to forecast the Age of Em, simple standard academic theories are not enough to even get started. The entire analysis hinges on which people get emulated, and there is absolutely no simple standard academic theory of that. If, as I've argued, we would copy the most robot-like people and treat them as slaves, at least 90% of Robin's details are wrong. That's low accuracy even by academic standards; I'd put it at the 20th percentile of overall accuracy.

given my task, and considering average accuracy relative to simple

standard academic theories, what do you estimate to be my percentile

rank in 1) overall accuracy, and 2) the number (or amount) of forecasts?

However, by Robin's second criteria - number of forecasts - he's off the charts. I'd put him at the 99th percentile, or even the 99.9th percentile. But I wish he'd spent vastly more time getting the foundations right, or at least carefully defending his foundational assumptions against the alternatives. That's what Robin did in his stupendous piece on futarchy in the Journal of Political Philosophy, and that's what I wish he did in The Age of Em.

(1 COMMENTS)

Pre-Brexit Bet Clarification, by Bryan Caplan

If any current EU member with a population over 10 million peopleBefore the June 23 Brexit referedum happens, I want to clarify that a majority vote for "Leave" is not sufficient for official withdrawal. I will happily concede defeat if and when (a) the European Union officially removes Britain from its list of members, or (b) the British government officially announces a unilateral withdrawal.

in 2007 officially withdraws from the EU before January 1, 2020, I will

pay you $100. Otherwise, you owe me $100.

If any of my betting partners objects, I am willing to defer to a mutually acceptable arbiter.

(1 COMMENTS)

June 14, 2016

Deregulation, Voodoo, and Krugman, by Bryan Caplan

In "Notes on Brexit" (June 12, 2016), Krugman scoffs at the pro-growth power of deregulation:

Pay no attention to claims that Britain, freed from EU rules, couldIn "Cities for Everyone" (April 4, 2016) however, Krugman sings an utterly different tune:

achieve spectacular growth via deregulation. You say to-mah-to, I say

voodoo, and it's no better than the US version.

OurI expect that Paul will protest, "Leaving the EU won't deregulate British housing." That's probably right. But then Paul shouldn't dismiss deregulation in general as "voodoo." Instead, he should declare, "Some deregulation has enormous growth potential, but Britain can pursue this deregulation just as well within the EU as without."

big cities, even New York, could comfortably hold quite a few more

families than they do. The reason they don't is that rules and

regulations block construction. Limits on building height, in

particular, prevent us from making more use of the most efficient public

transit system yet invented - the elevator.Now,

But

I'm not calling for an end to urban zoning...

building policies in our major cities, especially on the coasts, are

almost surely too restrictive. And that restrictiveness brings major

economic costs. At a national level, workers are on average moving, not

to regions that offer higher wages, but to low-wage areas that also have

cheap housing. That makes America as a whole poorer than it would be if

workers moved freely to their most productive locations, with some estimates of the lost income running as high as 10 percent.

So why not say that, Paul? You could even blame the Republicans while you do it: "Republicans are great fans of deregulation as a slogan, but when specific deregulation promises enormous economic gains - especially for the poor - Republicans lack the attention span and follow-through to make deregulation a reality. Even when they're right, they're wrong."

(4 COMMENTS)

June 13, 2016

3 Answers from Robin, by Bryan Caplan

Let me emphasize yet again that I present myself in the

book as an expert on facts, not on values, so my personal values should

not be relevant to the quality of my book.The fact that you ask #3 suggests you seek an integral over the value

of the entire future. In which case I guess I need to interpret #1 as

no age of em or any form of AI ever appearing, and it is hard to

interpret "hell" as I don't know how many people suffer it for how long.

But if 0 is the worst case and 10 is the best case, then humans

continuing without any AI until they naturally go extinct is a 2, while

making it to the em stage and therefore having a decent chances to

continue further is a 5. Biological humans going extinct a year later

is 4.9.

This is as I expected and feared. Given Robin's values, The Age of Em's disinterest in mankind makes perfect sense. But to be blunt, treating imminent human extinction as a minor cost of progress makes Robin's other baffling moral views seem sensible by comparison.

In practice, I'm sure Robin would be horrified to see robots wipe out everyone he knows. Why he sees no need to reconcile his near-horror with his far-optimism is a deep mystery to me.

To be clear, I'm not even slightly worried about robots wiping out mankind. But if it happened, it would be the worst thing that ever happened, and an infinite population of ems would not mitigate this unparalleled disaster.

(2 COMMENTS)June 12, 2016

3 Questions for Robin, by Bryan Caplan

1. Earth as it currently exists?

2. The Age on Em as you describe it?

3. The Age of Em if it ends in human extinction within one objective year?

Inquiring minds want to know!

(0 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers