Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 105

February 10, 2016

Betting Rules, by Bryan Caplan

I think this episode is a good example of what is wrong with betting on ideas. Betting tends to lock people into positions, gets them rooting for one outcome over another, it makes the denouement of the bet about the relative status of the people in question, and it produces a celebratory mindset in the victor. That lowers the quality of dialogue and also introspection, just as political campaigns lower the quality of various ideas -- too much emphasis on the candidates and the competition. Bryan, in his post, reaffirms his core intuition that labor markets usually return to normal pretty quickly, at least in the United States. But if you scrutinize the above diagram, as well as the lackluster wage data, that is exactly the premise he should be questioning.Let's analyze this point-by-point.

I think this episode is a good example of what is wrong with betting onI think this episode is a good example of what is right with betting on ideas.

ideas.

Betting tends to lock people into positions,Tyler's not wrong. Betting "locks people into positions" in the laudable sense that it makes them clearly state what their positions are. Once positions have been spelled out, though, betting spurs the opposite of dogmatism. The clarity of the resolution fortifies right people and disconcerts wrong people. That's progress toward truth.

...gets them rootingIndeed. But unless either party has the power to change the outcome for the worse, what difference does it make what they're rooting for?

for one outcome over another,

...it makes the denouement of the bet aboutPartly, but this is all for the good. The loser had a theory with a prediction he was willing to bet on. He was wrong. This isn't conclusive proof his theory was wrong or his judgment is poor, but it is an ironclad reason to reduce confidence in the theory and the judgment of the person who held it.

the relative status of the people in question,

...and it produces aI fail to see why this is a problem. The possession of demonstrable insight is worth celebrating. But if victory laps are bad, they are a far lesser evil than what pervades the betless badlands: the eternal celebratory mindset of pundits who refuse to specify in advance what counts as victory.

celebratory mindset in the victor.

That lowers the quality of dialogue and also introspection, just asThere's a world of difference between elections and bets. Elections are popularity contests. Bets are cognitive contests. The electoral mistake is to conflate the two: To think ideas are right because they're popular. I've never known a victorious better to make the parallel mistake - to think that because they've won a bet, the political system will heed their wisdom. I personally expect nothing of the sort.

political campaigns lower the quality of various ideas -- too much

emphasis on the candidates and the competition.

Bryan, in his post, reaffirms his core intuition that labor marketsI'm happy to admit there are broader questions here, though Noah Smith, not Tyler, has the right of it. But when a bet lets us make progress on narrower questions, we shouldn't rush to change the subject. Instead, we should pause, reflect, and be grateful that we genuinely learned something. Betting rules.

usually return to normal pretty quickly, at least in the United States.

But if you scrutinize the above diagram, as well as the lackluster wage

data, that is exactly the premise he should be questioning.

(2 COMMENTS)

February 9, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Spolaore and Wacziarg, by Bryan Caplan

Summary

Spolaore and Wacziarg survey a broad literature on long-run growth, paying special attention to measures of ancestry. They begin by surveying the evidence on the strong long-run effects of geography: absolute latitude and islands are good for prosperity, tropics and being landlocked are bad. They then cover and critique Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson's famous "reversal of fortune" paper. According to SW, ARJ's results are fragile:

[W]hen Europe is included in the sample, any evidence for reversals of fortune disappears: the coefficient on 1500 population density is essentially zero for the broadest sample that includes the whole world (column 1). For countries that were not former European colonies, there is strong evidence of persistence, with a positive significant coefficient on 1500 density. The evidence of persistence is even stronger when looking at countries that are populated mostly by their indigenous populations (the evidence is yet stronger when defining "indigenous" countries more strictly, for instance requiring that more than 90 percent of the population be descended from those who inhabited the country in 1500).This in turn leads SW into the work this Read Club has already covered. But rather than simply cite them, SW tweak their regressions and report the results. Log per capita income in 2005 is the dependent variable.

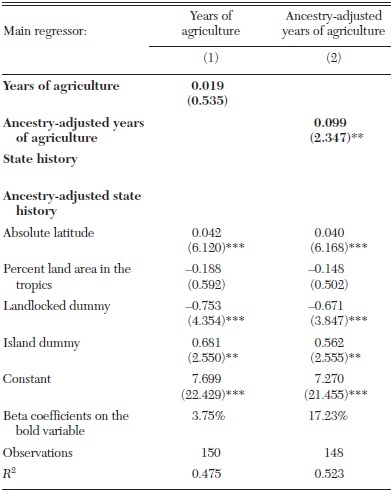

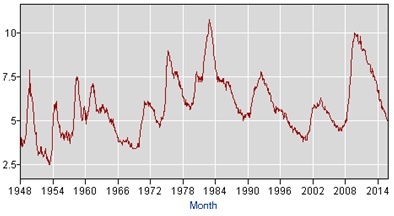

First, agricultural measures:

Second, state history measures:

Both sets of regressions reinforce the lessons of Putterman and Weil: ancestry and geography are both big deals. If I'm correctly applying SW, though, they find a smaller effect of ancestry and a larger effect of geography, presumably because they add the "Island" variable. An extra 10,000 years of ancestral agriculture boosts expected per-capita income by 269%. But moving 25 degrees from the equator has the same effect. And moving from a landlocked country to an island at the same latitude boosts per-capita income by 343%!

For ancestral state history, similarly, going from the min to the max raises per-capita income by 337%. But moving 26 degrees from the equator does the same, and moving from a landlocked country to an island at the same latitude boosts per-capita income by 288%.

SW then move into their own work on genetic distance. What's genetic distance?

Genetic distance is a summary measure of differences in allele frequencies between populations across a range of neutral genes (chromosomal loci). The measure we used, FST genetic distance, captures the length of time since two populations became separated from each other. When two populations split apart, random genetic mutations result in genetic differentiation over time. The longer the separation time, the greater the genetic distance computed from a set of neutral genes. Therefore, genetic distance captures the time since two populations have shared common ancestors (the time since they were parts of the same population), and can be viewed as a summary measure of relatedness between populations.Genetic distance from the United States turns out to be another highly-predictive ancestry measure - though, as usual, geography also matters enormously.

SW close the paper with a lengthy discussion of where the results come from and what they mean. Most notably, they ponder the distinction between "direct" and "barrier" effects of long-run forces:

One possibility is that intergenerationally transmitted traits have direct effects on productivity and economic performance. A slow-changing cultural trait developed in early history could be conducive directly to high incomes in modern times if it is transmitted from parents to kids within populations, either behaviorally or through complex symbolic systems (e.g., by religious teaching). For example, a direct effect stemming from cultural transmission would be Weber's (1905) argument that the Protestant ethic was a causal factor in industrialization (a recent critical reassessment of this hypothesis has been provided by Becker and Woessmann 2009).SW close by trying to prevent misinterpretation of the research. Yes,

As we discussed in the previous section, another possibility is that human traits act to hinder development through a barrier effect. In this case, it is not the trait itself that directly affects economic performance. Rather, it is differences in inherited characteristics across populations that create barriers to the flow of technological and institutional innovations, ideas, etc., and, consequently, hurt development. Historically rooted differences may generate barriers--e.g., via cultural, racial, and ethnic bias, discrimination, mistrust, and miscommunication--hindering interactions between populations that could result in a quicker diffusion of productivity enhancing innovations across populations...

Taking the recent literature seriously implies acknowledging the limits faced by policymakers in significantly altering the wealth of nations when history casts a very long shadow. A realistic understanding of the role of historical factors is essential for policy assessment. One could obtain misleading conclusions about the effects of specific policies and institutions when not taking into account the role of long-term variables.But the fraction of variance explained by long-run forces is way below 1, and many countries have broken out of bad long-run trajectories.

Critical Comments

1. Overall, I have less to say about SW because most of my earlier critical comments transfer over. Besides introducing the economics profession to a lot of interesting research, SW's main value-added is providing outside verification that ancestry regressions are robust. All the main results we've reviewed hold up: ancestry matters a lot, even controlling for geography, but geography is also greatly important, controlling for ancestry.

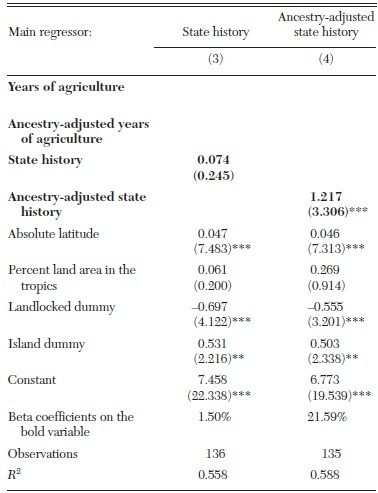

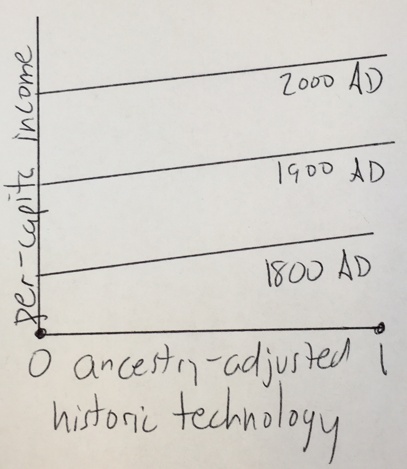

2. SW's caveats are understated. All their regressions - and as far as I can tell, all the research they discuss - try to explain why some countries are richer than others. None of them even whisper that some countries are doomed to absolute poverty. The amazing economic history of the last two centuries shows the opposite. While relative performance is fairly stable, absolute performance has skyrocketed. Remember last week's graph:

The same holds if we put any of the key ancestry measures on the x-axis: In any given year, countries with more successful ancestors do better. Over time, however, the whole success curve is rapidly shifting up.

To be fair, SW are writing in an intellectual environment where the basic facts of exploding global prosperity are well-known. But non-economists who read SW are dangerously likely to embrace a misguided fatalism.

3. Once again: If we take all of SW's results seriously - ancestry and geography - the case for free migration gets stronger, not weaker. Global economic growth will end absolute poverty eventually, but all this research confirms that moving the world's poor to rich countries is an amazing short-cut.

(0 COMMENTS)

February 8, 2016

A Simple Proof Not All Markets Work Well, by Bryan Caplan

Libertarians love to preach the virtues of markets. Yet in thePerhaps Jerry's only being poetic, but I see a deep truth within: However you cut it, all markets don't work well. Consider these three premises:

"marketplace of ideas," their bundled product has been regularly and

thoroughly rejected for over a century. Until libertarians acknowledge

that market verdict and re-think either what they're selling, how

they're selling it, or both, they will remain on the margins of American

political life.

1. All markets work well.

2. If the market for ideas works well, truth will largely win out.

3. The market for ideas strongly rejects the view that "All markets work well."

It's easy - and appropriate - to throw this argument in the face of the dogmatic libertarian. "All markets work well? Then how come the market rejects your ideas?" But the thoughtful libertarian should reject dogma in favor of some combination of the following:

1'. Most markets work well, but the market for ideas doesn't. Why not? Because ideas have massive externalities. The market for pollution works poorly because strangers bear almost all the cost of your pollution. The market for ideas, similarly, works poorly because strangers bear almost all the cost of your irrationality. This is the heart of my argument in The Myth of the Rational Voter .

2'. Truth doesn't largely win out in a well-functioning market for ideas, because consumers primarily seek not truth, but comfort and entertainment. Look at the market for religion. No matter what your religious views, it's hard to claim truth prevails, because even the generously-defined market leader has less than half the market. The same goes for political ideas.

Like Jerry, I reject dogmatic libertarianism. And I'm all for better marketing of libertarian ideas. But no matter how true libertarianism is, we shouldn't expect it to be popular. Why not? Because it tells people an ocean of things they deeply resent. Better marketing can soften the blow, but can't turn it into a pat on the head. While this is no excuse for having a bad attitude, few markets are more perverse than the market for ideas. Treating its verdict as a test of truth is a terrible mistake.

(1 COMMENTS)

February 7, 2016

I Win My Long-Term Unemployment Bet with Tyler, by Bryan Caplan

...U.S. unemployment will never fall below 5% during the next twentyUnemployment has been stalled at 5.0% for months. But this January, the rate slipped to 4.9%. I have therefore won the bet with almost 18 years to spare.

years. If the rate falls below 5% before September 1, 2033, he

immediately owes me $10. Otherwise, I owe him $1 on September 1, 2033.

Per my Bettor's Oath, I commend Tyler for having the courage to publicly bet on his pessimism. (Unlike some people). But it's not out of line to observe that his extreme confidence was extremely out of place. Where did he go wrong? My port mortem: Like most news junkies, Tyler refuses to admit the near-insignificance of current events. He loves the idea that the latest headlines reveal the latest deep truths. I, in contrast, take the far view. I form my views on the basis of long-run basic facts, and regard news as near-noise.

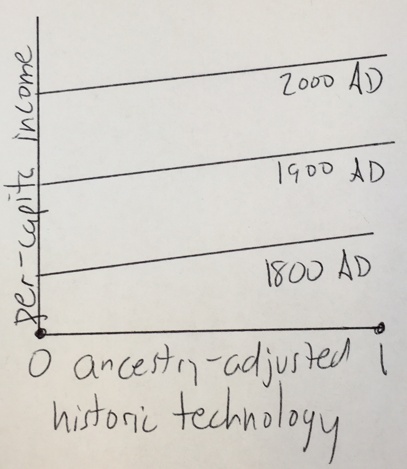

The far view that guided my bet is rooted in the following graph for U.S. unemployment rate from 1948-2016.

There's a strong pattern: While unemployment spikes fairly unpredictably, it reliably falls by about 1 percentage-point per year after it peaks. So while I wasn't confident about how high unemployment would go, I strongly expected it to recede at about its usual rate. Since it peaked at 10% around January 2010, I expected it to get back to 5% by January 2015. In the end, it took six years instead of five, but well within historic bounds.

My deeper incredulity, to be sure, was Tyler's extreme (10:1!) confidence that unemployment had entered a durably high natural level. This has happened in the past, but very rarely for a full two decades. Furthermore, there were no dramatic warning signs the last time we entered the era of high unemployment, just as there were no dramatic advance warning signs we were exiting that era. Here, as elsewhere, claims to gnosis do not impress me.

Did I get lucky? I'm happy to restart the bet the next time a recession hits.

(1 COMMENTS)

February 3, 2016

The Equator in Comin, Easterly, and Gong, by Bryan Caplan

So suppose you move the population of a landlocked equatorial country to a coastal country at 45 degrees latitude. 45 degrees latitude corresponds to a "distance from the equator" score of .5. CEG's results in column (3) therefore predict their log per-capita GDP will rise by .5*1.68 + .25*1.063+.646=1.75. That almost exactly equals the effect of having ancestors with a tech score of 0 (the minimum) and ancestors with a tech score of 1 (the maximum).

The comparison for columns (1) and (2) is even more lopsided. If you think CEG provides a clear-cut rationale for restricting Third World immigration, you're suffering from confirmation bias.

(0 COMMENTS)

February 2, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Comin, Easterly, and Gong, by Bryan Caplan

Summary

We've already seen what happens if we try to predict nations' current economic conditions using measures of early political organization and agriculture. As long as we measure nationality by ancestry rather than location, historical precocity predicts modern prosperity. What happens if we measure early technology in the same way? Comin, Easterly, and Gong construct a data set on societies' technologies in 1000 BC, 0 AD, and 1500 AD. Measured by location, these technology measures are mildly predictive. Measured by ancestry - using Putterman-Weil's migration matrix - these technology measures are highly predictive.

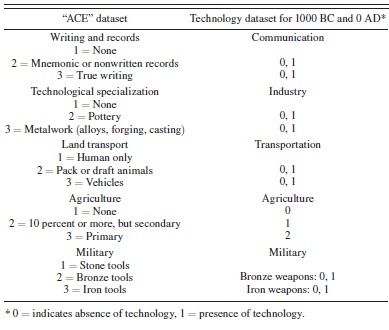

What historic technologies do CEG consider? For 1000 BC and 0 AD, the basics:

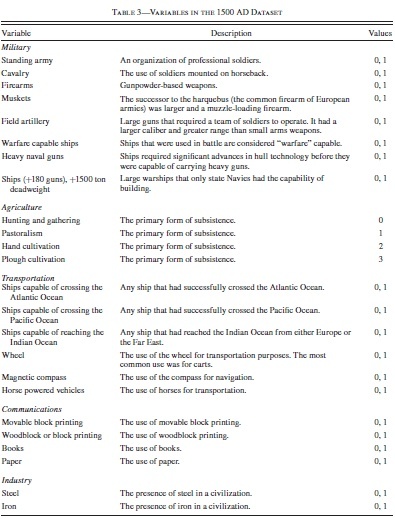

For 1500 AD, measured techs are far more advanced.

Finally, here is how CEG measure current technology.

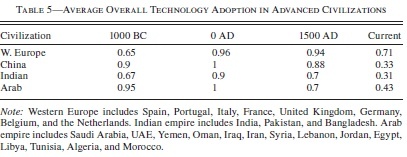

This measure captures (one minus) the average gap in the intensity of adoption of ten major current technologies with respect to the United States. These technologies are electricity (in 1990), Internet (in 1996), PCs (in 2002), cell phones (in 2002), telephones (in 1970), cargo and passenger aviation (in 1990), trucks (in 1990), cars (in 1990), and tractors (in 1970) all in per capita terms.What are the basic facts of technological development over time? Here's a fun table.

More specifically, for each technology, Comin, Hobijn, and Rovito (2008) measure how many years ago the United States last had the usage of technology "x" that country "c" currently has. We take these estimates and normalize them by the number of years since the invention of the technology to make them comparable across technologies, take the average across technologies and multiply the average lag by minus one and add one to obtain a measure of the average gap in the intensity of adoption with respect to the United States, whose adoption level is one, by construction.

In 1000 BC, China and the Arab world were the pinnacle of civilization; Western Europe and India lagged well behind. By 0 AD, all four were almost maxed out. By 1500 AD, Western Europe took the lead, with China close behind. Today, Western Europe dominates (though it's still way behind the United States), followed by the Arab world, with China and India at the bottom. Despite these contrarian findings, CEG find it necessary to remark:

Why do our historical rankings differ from the view that ancient Europeans were barbarians, while China and the Middle East/Islamic civilizations were well in the lead for most of our sample period and produced most of the useful inventions? Basically, it is because what we are measuring is the adoption of technologies rather than the invention...As long as "ancient" means "1000 BC," though, CEG confirm the "ancient European barbarians" stereotype.

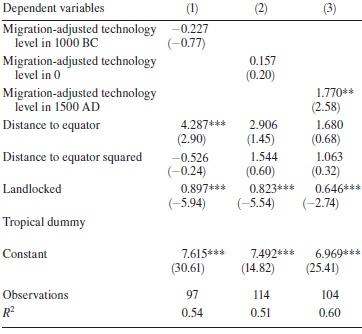

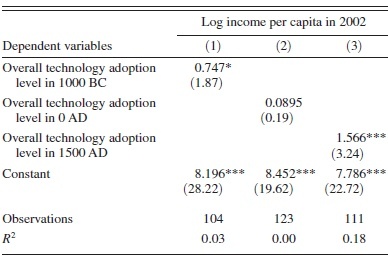

After several intervening sections, CEG estimate the effect of historical technology on modern conditions. Unadjusted for migration, the results are only mildly impressive.

Effect sizes are big for 1000 BC and 1500 AD, but not for 0 AD. The statistical significance for 1000 BC, however, is frail. And this is before adding a single control variable.

Adjusting for ancestry, however, dramatically pumps up the estimates. How do CEG do this? By following the yellow brick road laid out in last week's paper, where Putterman and Weil remarked:

The

[ancestry] matrix can be used as a tool to adjust historical data to

reflect the status in the year 1500 of the ancestors of a country's

current population. That is, we can convert any measure applicable to

countries into a measure applicable to the ancestors of the people who now live in each country.

Here's what CEG find in the Emerald City:

Takeaway: "Our key 1500 AD result implies large magnitudes. Regressing income today on the migration-weighted index for 1500 AD, a coefficient of 3.261 implies that a movement from 0 to 1 is associated with an increase in per capita income today by a factor of 26.1. The log difference in per capita income today between Western Europe and sub-Saharan Africa is 2.59 (a factor of 13.3). This income difference is usually attributed to the post-1500 slave trade, colonialism, and post-independence factors in sub-Saharan Africa."

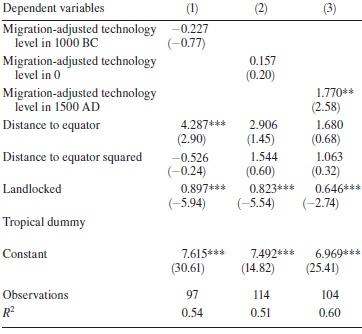

CEG handily show that in a horse-race, ancestry-adjusted measures of technology crush location-based measures. But how do the results for log per-capita income hold up in the face of well-established geographic controls?

Overall, pretty poorly. Adjusting for ancestry, adding standard geographic controls reverses the sign of technology in 1000 BC, leaves a barely statistically significant effect of technology in 0 AD, and reduces the coefficient on 1500 AD tech by almost 50%. Since we're predicting log income, that's an even bigger downward revision than it looks. Moving from 0 to 1 now yields a increase of 590%, not 2,610%. (By the way, if you're puzzled by the benefits of being landlocked, so was I. When I checked with Easterly, he confirmed those positive landlocked coefficients are typos; all should be negative). Note further that the lack of statistical significance on distance from the equator probably stems from the inclusion of a linear and squared term; if CEG stuck with a linear specification like Putterman and Weil, absolute latitude would have its usual clear-cut payoff.

CEG wrap up the paper with further robustness tests. As far as I can tell, they don't explicitly answer the question, "Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 BC?" But their data say No.

Critical Comments

1. This is another very impressive paper. While there's plenty to debate in the history of technology, CEG make a serious effort to code the basic facts. If I re-did their work, I'd expect a correlation of at least .8 between their measures and mine. And it's great to see CEG extend PW's ancestry matrix to a new and plausibly important variable.

2. A careful reading shows that CEG is widely misread. They don't show that events thousands of years ago matter today - even adjusting for ancestry! After adding standard controls, tech in 1000 BC doesn't matter. Neither does tech in 0 AD. Tech in 1500 AD definitely seems important. But since only one out of three measures of tech works as expected, the wise interpretation is unclear.

3. Suppose CEG found a much larger effect of tech in 1000 BC. Would this really show "the wealth of nations was determined in 1000 BC"? Only if you interpret the wealth of nations in relative terms: the most advanced countries in the past are the richest countries in the present. This emphatically does not mean, however, that countries that were technologically backward in 1000 BC are doomed to absolutely poor today. Worldwide economic growth over the last two centuries means that holding the past fixed, the present is dramatically improving. Graphically:

Does this graph show per-capita income is "determined by historic technology"? At any point in time, yes. But the overall function is still dramatically shifting up over time. My point: Contrary to some, CEG provide no support for fatalism. Frankly, they should have tried harder to prevent that misreading.

4. Does CEG show low-skilled immigration is bad? No more than Putterman-Weil did. In both cases, you need to remember all the results. Yes, countries inhabited the descendants of more advanced civilizations do better - and you can't change your ancestors. But CEG, like PW, also detect enormous long-run benefits of geography. And you can effectively change geography by letting people to move to the parts of the globe most hospitable to prosperity. Contrary to popular opinion, this is not a great "national sacrifice." Since migration dramatically increases productivity, migrants enrich themselves by enriching their customers - starting with their new neighbors.

5. While CEG's results are interesting and important, they're noticeably weaker than PW's. In a three-way race between State History, Agriculture, and Technology - Garett Jones' "SAT score" - State History and Agriculture are roughly on par, but Technology lags behind. Why isn't anyone doing a standard econometric horse race with all three explanatory variables in the same regression? My best guess is that they're too correlated to disentangle. If I learn more, I'll post it here.

(0 COMMENTS)

Putterman's Commentary, with My Replies, by Bryan Caplan

I just wanted to offer one

correction and one further quick comment.

You wrote: "How could one

even begin to construct such a matrix? Whenever possible, P&W use

actual genetic data, then supplements genetics with history." For better

or worse, this isn't really the case. We rely heavily on heroic assumptions

that unless identified by sources like the ones mentioned in our appendix such

as Everyculture.com, Countriesquest.com, Encyclopaedia Britannica, World

Christian Encyclopedia, etc., people living in a country conventionally assumed

to be fairly ethnically homogeneous, e.g. France or Spain, are descended from

people of that same country. The sources do mention migrants, for instance

Algerians in France, but there may well be an undercount of mobility of the

presumptively French population, who could well have ancestors who crossed what

is now a border with Germany, Italy, Spain, or even a couple of borders (from,

say, Poland) sometime in the 500 years ending in 2000. (We have to hope that

such migration doesn't make a big difference, as descendants will in the

meantime have perhaps become for all practical purposes like those with only

ancestors within current French boundaries during that half millennium.) We

used sources based on genetic studies only to get estimates of the regional

ancestries of populations described as being of mixed origin, e.g.

"mestizos", in those same sources, and only for countries having a

large share of such people, 30% or more, for instance Mexico. The method is

described on p. 1632 of our paper, and I think I can see how your misunderstanding

might have arisen based on the first sentence on that page: "whenever

possible we have used genetic evidence as the basis for dividing the ancestry

of modern mixed groups that account for large fractions of their country's

population." As you can see from a closer reading, we do this only for

mixed groups such as "mestizo" "mulatto" etc. and only when

they are a large fraction. The extant DNA studies mainly attempt to pick up

differences between long separated populations, such as sub-Saharan Africans

and Europeans, but not between members of populations that haven't been as

separated, like Germans and Italians.

My other comment is that you

write that "civilized migration - where people voluntarily move to a new

country to peacefully improve their lives - is an extreme historical

rarity." We don't take any definite position on that, but off hand it

seems wrong and we didn't mean to suggest it. Although there was a lot of

forced movement of Africans to the New World early on, there was overall even

more voluntary movement to the Americas, mostly of people from Europe but also

ones from other regions, and likewise large parts of the overall migration to

places like Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Singapore, and Taiwan was

voluntary on the parts of the migrant. Whether these arrivals were

welcomed by the original inhabitants (Native Americans, indigenous Australians

and Taiwan indigenous peoples, etc.) is a whole other story.

By the way, regarding state

history working well with 5% discounting, I believe we tested a bit and found

it relatively insensitive, so we used the discount that had been applied in

other papers. It does turn out that if one lacks back to years before 1 CE,

some results become more sensitive to discounting. Borcan, Olsson and I have a

working paper in which we report state history for roughly the same number of

countries, but going back to the first states, in Mesopotamia before 3,000 BCE.

We find that current GDP is concave in this longer-term state history

especially when using a low discount like 1% so that the more ancient periods

still get non-negligible weight; by concave, I mean that the oldest states such

as Iraq are predicted to have lower GDP than "middle aged" ones like

England and Germany.

-

Louis

My replies:

1. I did indeed overstate PW's reliance on genetic data. My mistake.

2. I included the word "peaceful" in my definition of "civilized

migration" to exclude migrants who took the land (and often lives) of the

existing inhabitants. Voluntary on the part of the migrant isn't

enough. Of course, there's a continuum. But European colonization

was largely predicated on military conquest, unlike immigration as we usually conceive it today.

3. Thanks for the details on the state history discounting.

(0 COMMENTS)

Two Election Bets, by Bryan Caplan

2. Nathaniel Bechhofer bets $40 at 2:1 that Hillary Clinton wins the 2016 presidential election. I bet against.

My reasoning, in both cases, is that betting markets are more accurate than the people I eat lunch with.

(8 COMMENTS)

February 1, 2016

ADHD Reconsidered, by Bryan Caplan

disguised as diagnoses, and with coercions justified as treatments." I realize this is an unwelcome view, but I do have a whole paper defending it, and I stand by it.

My general claim:

[A] large

fraction of what is called mental illness is nothing other than unusual

preferences - fully compatible with basic consumer theory. Alcoholism

is the most transparent example: in economic terms, it amounts

to an unusually strong preference for alcohol over other goods. But

the same holds in numerous other cases. To take a more recent addition

to the list of mental disorders, it is natural to conceptualize

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as an exceptionally

high disutility of labor, combined with a strong taste for

variety.

Consider how economists would respond if anyone other than a

mental health professional described a person's preferences as

'sick' or 'irrational'. Intransitivity aside, the stereotypical economist

would quickly point out that these negative adjectives are thinly disguised

normative judgments, not scientific or medical claims. Why should mental health professionals be exempt from economists'

standard critique?

This is essentially the question asked by psychiatry's most vocal

internal critic, Thomas Szasz. In his voluminous writings, Szasz

has spent over 40 years arguing that mental illness is a 'myth' -

not in the sense that abnormal behavior does not exist, but rather

that 'diagnosing' it is an ethical judgment, not a medical one. In

a characteristic passage, Szasz (1990: 115) writes that:

Psychiatric diagnoses are stigmatizing labels phrased to resemble medical diagnoses,The American Psychiatric Association's (APA) 1973 vote to take

applied to persons whose behavior annoys or offends others. Those who

suffer from and complain of their own behavior are usually classified as 'neurotic';

those whose behavior makes others suffer, and about whom others complain, are

usually classified as 'psychotic'.

homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses is a microcosm of the

overall field (Bayer 1981). The medical science of homosexuality

had not changed; there were no new empirical tests that falsified

the standard view. Instead, what changed was psychiatrists' moral

judgment of it - or at least their willingness to express negative

moral judgments in the face of intensifying gay rights activism.

Robert Spitzer, then head of the Nomenclature Committee of the

American Psychiatric Association, was especially open about the

priority of social acceptance over empirical science. When publicly

asked whether he would consider removing fetishism and voyeurism

from the psychiatric nomenclature, he responded, 'I haven't given

much thought to [these problems] and perhaps that is because the

voyeurs and the fetishists have not yet organized themselves and

forced us to do that' (Bayer 1981: 190). Even if the consensus view

of homosexuality had remained constant, of course, the 'disease'

label would have remained a covert moral judgment, not a valuefree

medical diagnosis.

Although Szasz does not use economic language to make his

point, this article argues that most of his objections to official

notions of mental illness fit comfortably inside the standard economic

framework. Indeed, at several points he comes close to

reinventing the wheel of consumer choice theory:

We may be dissatisfied with television for two quite different reasons: because theMy analysis of ADHD specifically:

set does not work, or because we dislike the program we are receiving. Similarly,

we may be dissatisfied with ourselves for two quite different reasons: because our body does not work (bodily illness), or because we dislike our conduct (mental

illness). (Szasz 1990: 127)

4.2. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Substance abuse is a particularly straightforward case for economists

to analyze, since it involves the trade-off between (1) one's

consumption level of a commodity and (2) the effects of this consumption

on other areas of life. But numerous mental disorders

have the same structure. One way to be diagnosed with ADHD, for example, is to have six or more of the symptoms of inattention

shown in Table 2.

Overall, the most natural way to formalize

ADHD in economic terms is as a high disutility of work combined

with a strong taste for variety. Undoubtedly, a person who dislikes

working will be more likely to fail to 'finish school work, chores or

duties in the workplace' and be 'reluctant to engage in tasks that

require sustained mental effort'. Similarly, a person with a strong taste for variety will be 'easily distracted by extraneous stimuli' and

fail to 'listen when spoken to directly', especially since the ignored

voices demand attention out of proportion to their entertainment

value.

A few of the symptoms of inattention - especially (2), (5) and (9),

are worded to sound more like constraints. However, each of these is

still probably best interpreted as descriptions of preferences. As the

DSM uses the term, a person who 'has difficulty' 'sustaining attention

in tasks or play activities' could just as easily be described as

'disliking' sustaining attention. Similarly, while 'is often forgetful

in daily activities' could be interpreted literally as impaired

memory, in context it refers primarily to conveniently forgetting

to do things you would rather avoid. No one accuses a boy diagnosed

with ADHD of forgetting to play videogames.

What about all the contrary scientific evidence? It's not really contrary. The best empirics in the world can't resolve fundamental questions of philosophy of mind.

Another misconception about Szasz is that he denies the connection

between physical and mental activity. Critics often cite findings

of 'chemical imbalances' in the mentally ill. The problem with these

claims, from a Szaszian point of view, is not that they find a connection

between brain chemistry and behavior. The problem is that

'imbalance' is a moral judgment masquerading as a medical one.

Supposed we found that nuns had a brain chemistry verifiably different

from non-nuns. Would we infer that being a nun is a mental

illness?

A closely related misconception is that Szasz ignores medical evidence

that many mental illnesses can be effectively treated. Once

again, though, the ability of drugs to change brain chemistry and

thereby behavior does nothing to show that the initial behavior

was 'sick'. If alcohol makes people less shy, is that evidence that shyness

is a disease? An analogous point holds for evidence from behavioral

genetics. If homosexuality turns out to be largely or entirely

genetic, does that make it a disease?

Bottom line: My use of the term "ADHD" was indeed problematic because the concept itself is problematic. Then why use it? Because you can grasp my original point without sharing my broader perspective - and if I started with my broader perspective, it would drown out my original point.

(7 COMMENTS)

January 31, 2016

ADHD Shall Save Us, by Bryan Caplan

The median American is no Nazi, but he is a moderate national socialist -Since then, popular yearning for national socialism has grown even more pronounced. But I still don't expect policies to get too much worse. The same psychological force that thwarted the masses' wishes before 2012 continues to shield us. What is that force? For want of a better term, ADHD - Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Populist policy preferences go hand-in-hand with intellectual laziness and intellectual impatience. As a result, populist voters fail to hold their leaders' feet to the proverbial fire - allowing wiser, elitist heads to prevail.

statist to the core on both economic and social policy. Given public

opinion, the policies of First World democracies are surprisingly

libertarian.

Take protectionism. Keeping imports out of our country is perennially popular. Never mind centuries of economics classes on the wonders of comparative advantage; the masses are convinced that cheap foreign products make us poorer. Given public opinion, then, it's amazing that trade barriers are as low as they are. What's particularly striking is that presidential candidates routinely make protectionist noises to curry favor with the masses. Once elected, however, they get convenient amnesia.

Why would vote-seeking politicians show so little follow-through? Because talking about foreign trade, titillating at first, gets old fast. And actually measuring the change in trade barriers bores the masses instantly. As a result, protectionist promises are cheap to break. The masses delight to hear politicians vow to get "tough on China," but they don't want to have to think about Chinese imports months after the election, much less monitor their leaders' concrete efforts to cut China down to size.

The same goes for the War on Terror. Americans were quick to back the Afghanistan and Iraq wars in their early stages. After all, they were angry. But after a year or two, their minds wandered. If they combined their anger with determination and follow-through, we'd now be well into World War III. Millions would be dead, and American soldiers would occupy most of the Middle East, fending off ten thousand guerrilla armies. ADHD spared us these horrors.

Emotionally, I look down on the public's ADHD. When I get an idea into my head, it stays there until someone (possibly myself) argues me out of it. I'm a puritan. Once convinced something is true, I tenaciously act on it. But I'm the first to admit that these are conditional virtues. If you've genuinely figured out the right thing to do, determination and follow-through are wonderful. Otherwise, though, they're a menace.

Mankind can and should shape up across the board, but it won't. I'll bet on it. And since mankind won't discover a passion for rationality anytime soon, we should be thankful its ADHD isn't going away either.

(2 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers