Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 106

January 28, 2016

An Ivy League Admissions Officer Speaks, by Bryan Caplan

My post on elite high schools and college admission led an Ivy League admissions officer to email me. Here's what he wrote, with his kind permission. Name and school redacted.

Bryan,

Your post on TJ caught my eye, as

last year I read admissions files from NOVA for [redacted Ivy League school]

(along with an actually qualified admissions officer), including those from TJ.

Feel free to share any of this, though for reasons of discretion (and being

junior faculty!) please don't include my name/exact institution.

Much of what you wrote rings true

from my experience, but I'm not sure I'd reach the same conclusion you

did.

We definitely held students from

TJ to a higher standard than those from less prestigious schools. In fact, if

memory serves they were held to the highest standard by any NOVA students by a

decent margin.

Why? From our perspective, mainly

knowing that students there get lots of encouragement/coaching to do the kinds

of things that look good on an application, so a student from TJ that looks

equally good on paper as someone from another school (setting aside class rank)

is probably less good of a student. Also, there was some desire to give

students who had fewer opportunities a leg up, though this effect probably

wouldn't help the children of a professor even if they went to a less

prestigious school.

On the other hand, we also

certainly accounted for the strength of the school when interpreting class

rank. I don't remember exact numbers, but I think we gave students from TJ a

close look in the 2nd and even 3rd decile while this would be a kiss of death

from most other schools.

From a parent/student

perspective, the question is whether the boost in application quality from

being surrounded by high achievers and resources/opportunities students don't

get elsewhere outweighs the fact that they will face a higher bar when

admissions officers read their file. Theoretically, I would think that

causal effect of going to TJ on chances of admissions is probably neutral to

somewhat positive. To the extent that admissions officers care about getting

talented students who are prepared for an elite college, even if they fully

filter out the better preparation at schools like TJ when making inferences

about talent, they will still appreciate the better preparation in and of

itself. Nothing in my empirical observations led me to think this theoretical

expectation is wrong.

(Of course this sets aside the

impacts outside of chances of admission to an elite school, like what they

actually learn or how they might be harmed by the pressures of going to such a

school!)

Hope this is of interest,

[redacted]

(3 COMMENTS)

January 27, 2016

My Future of Freedom Foundation Interview, by Bryan Caplan

(0 COMMENTS)

January 26, 2016

Ancestry and Long-Run Growth Reading Club: Putterman and Weil, by Bryan Caplan

Summary

Putterman and Weil start by noting that - at least by some measures - economic success is persistent over the centuries. Countries that were advanced in the distant past tend to be richer today. But should we think of countries as locations or peoples? Economists routinely do the former, but maybe they shouldn't.

[T]he further back into the past one looks, the more the economic history of a given place tends to diverge from the economic history of the people who currently live there. For example, the territory that is now the United States was inhabited in 1500 largely by hunting, fishing, and horticultural communities with pre-iron technology, organized into relatively small, pre-state political units. In contrast, a large fraction of the current U.S. population is descended from people who in 1500 lived in settled agricultural societies with advanced metallurgy, organized into large states. The example of the United States also makes it clear that, because of migration, the long-historical background of the people living in a given country can be quite heterogeneous.To surmount this problem, P&W laboriously construct a country-by-country matrix of ancestry:

We construct a matrix detailing the year-1500 origins of the current population of almost every country in the world. In addition to the quantity and timing of migration, the matrix also reflects differential population growth rates among native and immigrant population groups. The matrix can be used as a tool to adjust historical data to reflect the status in the year 1500 of the ancestors of a country's current population. That is, we can convert any measure applicable to countries into a measure applicable to the ancestors of the people who now live in each country.How could one even begin to construct such a matrix? Whenever possible, P&W use actual genetic data, then supplements genetics with history. What does their matrix look like?

The matrix has 165 rows, each for a present-day country, and 172 columns (the same 165 countries plus seven other source countries with current populations of less than one half million). Its entries are the proportion of long-term residents' ancestors estimated to have lived in each source country in 1500. Each row sums to one. To give an example, the row for Malaysia has five nonzero entries, corresponding to the five source countries for the current Malaysian population: Malaysia (0.60), China (0.26), India (0.075), Indonesia (0.04) and the Philippines (0.025).The resulting matrix exposes two basic facts.

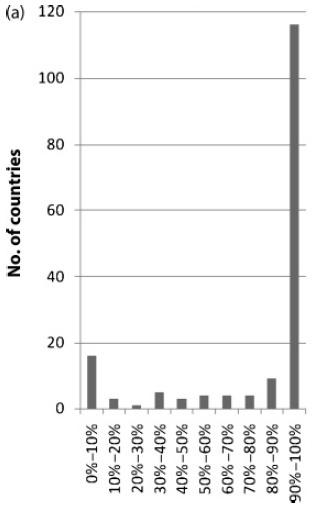

1. Long-distance migration is rare. Most modern countries are almost entirely populated by the descendants of earlier inhabitants of the region.

2. Long-distance migration is bimodal. When countries aren't almost entirely populated by the descendants of earlier inhabitants of the region, those earlier inhabitants usually have almost no descendants left in the country.

Check out the Distribution of Countries by Proportion of Ancestors from Own or Immediate Neighboring Country:

Here's the Distribution of World Population by Proportion of Ancestors from Own or Immediate Neighboring Country:

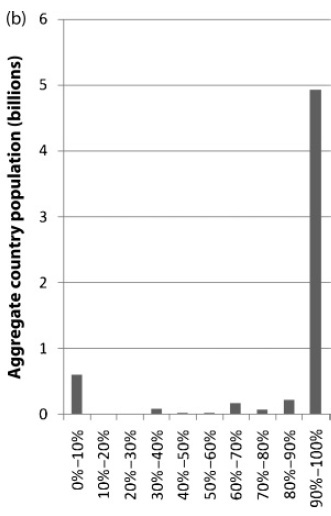

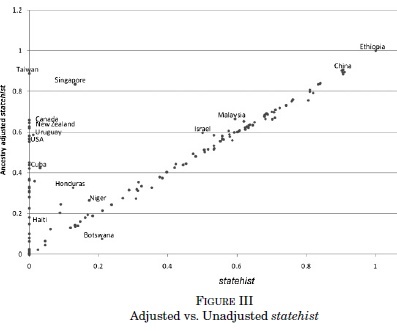

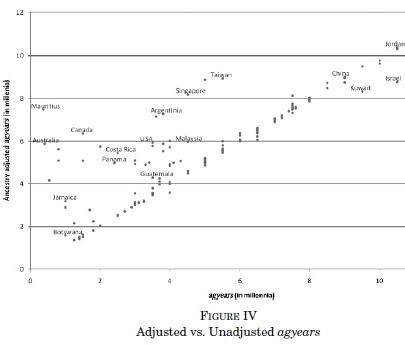

P&W now revisit earlier research on long-run growth, using their matrix to transform the key variables. Instead of looking at the long-run effects of places' traits, they look at the long-run effect of tribes' traits. They focus on two measures: state history and years of agriculture. State history measures how long a country "had a supratribal government, the geographic scope of that government, and whether that government was indigenous or by an outside power." Following previous work, they massage this measure: "The version used by us, as in Chanda and Putterman (2005, 2007), considers state history for the fifteen centuries to 1500, and discounts the past, reducing the weight on each half century before 1451-1500 by an additional 5%." Years of agriculture, in contrast, is not massaged. It's simply the "the number of millennia since a country transitioned from hunting and gathering to agriculture."

Since migration history is bimodal, adjusting these measures for migration has a bimodal effect. Most countries are near the 45-degree line, but a few radically diverge. Here's state history by location versus people:

Here's agricultural history by location versus people:

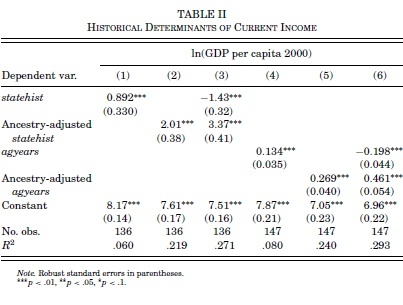

Now for the punchline: Migration-adjusted measures are much more predictive of modern GDP than raw measures. "Not surprisingly, given previous work, the tests suggest significant predictive power for the unadjusted variables. However, for both measures of early development, adjusting for migration produces a very large increase in explanatory power. In the case of statehist, R2 goes from .06 to .22, whereas in the case of agyears it goes from .08 to .24. The coefficients on the measures of early development are also much larger using the adjusted than the unadjusted values." Regression tables:

P&W try an array of robustness tests. The most notable challenge they address, however, is "What about geography?" Earlier researchers have found strong effects of latitude and being landlocked. Correcting for these factors, the effects of migration-adjusted history crash, but remain absolutely large.

After further checks, P&W switch gears to analyze how ancestry matters for current inequality. Punchline:

[T]he heterogeneity of a country's population in terms of the early development of its ancestors as of 1500 is strongly correlated with income inequality. We also show that heterogeneity with respect to country of ancestry or with respect to the ancestral language does a better job than does current linguistic or ethnic heterogeneity in predicting income inequalities today.Critical Comments

This is an awesome paper. While I'm sure Putterman and Weil made countless judgment calls in constructing their migration matrix, I'd bet that if I re-did their work, my matrix would have at least a .8 correlation with theirs. This is a classic "obvious once you think about it" paper, because rich non-Eurasian countries are now largely inhabited by Eurasians. It is also a courageous paper. As far as I know, P&W were not tarred and feathered for racism, but they sure could have been. All political correctness aside, though, what is the reasonable way to interpret their results?

1. While Garett Jones sees ancestry research as very damaging to the case for free migration, Putterman and Weil acknowledge that most historical migration was anything but free. Indeed, demographic change largely reflects conquest, genocide, and slavery.

Conquest, colonialism, migration, slavery, and epidemic disease reshaped the world that existed before the era of European expansion. Over the last 500 years, there have been dramatic movements of people, institutions, cultures, and languages among the world's major regions.In other words, civilized migration - where people voluntarily move to a new country to peacefully improve their lives - is an extreme historical rarity. While this doesn't prove that civilized migration has better long-run effects than conventionally brutal migration, it is plausible that dramatic long-run differences exist. Most obviously, civilized migration is an effective way to sincerely culturally "convert" people - and their children. Enslaving them, not so much.

2. P&W also detect a surprising benefit of ancestral heterogeneity:

We find that, holding constant the average level of early development, heterogeneity in early development raises current income, a finding that might indicate spillovers of growth-promoting traits among national origin groups.3. While it doesn't affect their case, P&W use extremely low populations for the New World in 1500. Is 1491 - and all the research upon which it builds - wrong? According to Wikipedia's summary of current research, P&W are off by a factor of three or more.

4. The time discounting of state history is worrisome. Putterman and Weil use Chanda and Putterman's 5% per half-century discount rate, but was this rate cherry-picked to make the results come out right?

5. On Twitter, Garett has been using the literature P&W jump-started to dissuade Western countries from admitting Syrian refugees. But by Putterman and Weil's agricultural measure, Syrians (and every else in the Fertile Crescent) are the most awesome people on the planet. Here's who the Syrians are, in case you're curious:

The vast majority of Syria's population is Arab, and is assumed to be indigenous to the country. There are also some Palestinian (2.8%) and Lebanese (0.5%) refugees living in the country (NE, WCD). Some Kurds (4%) have lived in the country for generations, but others (4%) came from Turkey in the early 20th century (LC, EV). The majority of Syria's Armenians (0.2%) and Turks (0.3%) also came from Turkey during the first half of the 20th century as refugees (LC, EV,WCD). The Bedouin Arabs (7.4%) are believed to have emigrated from the interior of the Arabian peninsula between the 14th and 18th centuries; thus, the ancestors of about two-fifths of the Bedouins are treated as having lived in Saudi Arabia (3%), which constitutes the vast majority of the peninsula. There is also a small population of Azerbaijanis (0.7%) whose ancestors are assumed to have lived in present-day Azerbaijan (WCD).6. P&W are writing in a field where the effects of geography are well-established. They aim to show that ancestry matters even controlling for geography - and they succeed. But geographic variables remain highly potent. Who cares, when you can't change geography? Well, you can't change the geography of places, but you can change the geography of people. How? Migration!

Estimate:

Azerbaijan: 0.7%

Israel/Palestine: 2.8%

Lebanon: 0.5%

Saudi Arabia: 3%

Syria: 88.5%

Turkey: 4.5% (4% as ancestors of Kurds, 0.2% as ancestors of Armenians)

Look at column (6) of their Table IV above. State history ranges from 0-1. Moving from the minimum to the maximum state history score predicts a +1.24 change in log GDP - an increase of about 350%. But you can get the same bonanza by moving 37 degrees away from the equator. If you go from a landlocked country to a non-landlocked country, a 20 degree move suffices.

Results for agriculture are similar. The variable ranges from 0-10.5. Moving from the minimum to the maximum agriculture score predicts a +1.61 change in log GDP - an increase of about 500%. You can get the same bonanza by moving 40 degrees away from the equator - or 26 degrees if you journey from a landlocked country to a non-landlocked country.

Taking P&W's results literally, then, this is a radically pro-immigration paper. Let mankind move away from the tropics and toward the coasts, and the predicted net effect is cornucopian. This would be true even if all migrants' ancestors were complete savages in 1500 AD. And if you look at P&W's numbers, you'll learn that even sub-Saharan Africans were well-above the minimum by 1500 AD, with state history scores around .2 and agriculture scores around 2. The implied long-run payoff from relocating humanity from poor countries to rich countries is plausibly even higher than the "double global GDP" estimate Michael Clemens popularized in "Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk."

7. P&W seems to imply a NIMBY result for immigration. Sure, migration enriches mankind, but doesn't it reduce per capita GDP in receiving countries? Taken literally, their full results imply the opposite, but P&W are skeptical:

The coefficients also have the unpalatable property that a country's predicted income can sometimes be raised by replacing high statehist people with low statehist people, because the decline in the average level of statehist will be more than balanced by the increase in the standard deviation. For example, the coefficients just discussed imply that combining populations with statehist of 1 and 0, the optimal mix is 86% statehist = 1 and 14% statehist = 0. A country with such a mix would be 41% richer than a country with 100% of the population having a statehist of 1...Econometrics aside, per-capita GDP is a dreadful measure of national welfare when migration is high. As I often point out, immigration can enrich everyone in a country while reducing per-capita GDP. In any case, the NIMBY inference depends on the size of the receiving country. If Belgium doubles its production via migration, most of the extra production will spill over onto the rest of the world. But if the EU doubles its production via migration, most of the extra production will probably be enjoyed by people in the EU.

Although our regression result reflects the fact that population heterogeneity has not detracted from economic development in the first group of countries, it seems best not to infer from it that "catch up" by homogeneous Old World countries would be speeded up by infusions of low statehist populations into existing high statehist countries.

8. Overall, this is an amazingly edifying paper. If your main reaction is name-calling, you don't belong in the world of ideas. If the paper showed that my crusade for open borders was misguided, I would just have to live with that unwelcome conclusion. But it shows nothing of the kind. Immigration critics looking for intellectual foundations will have to keep looking - or ignore half the paper's results.

(1 COMMENTS)

January 25, 2016

An Educational Challenge, by Bryan Caplan

[S]ome people cut their schooling short so as to pursue more

immediately lucrative activities. Sir

Mick Jagger abandoned his pursuit of a degree at the London School of Economics

in 1963 to play with an outfit known as the Rolling Stones... No less impressive,

Swedish ��p��e fencer Johan Harmenberg left MIT after 2 years of study in 1979,

winning a gold medal in the 1980 Moscow Olympics, instead of earning and MIT

diploma. Harmenberg went on to become a

biotech executive and successful researcher.

These examples illustrate how people with high ability - musical,

athletic, entrepreneurial, or otherwise - may be economically successful

without the benefit of an education.

This suggests that... ability bias, can be negative as easily as positive.

My challenge: Outliers aside, name any measured ability that on average falls as education rises. I'm looking for simple averages, nothing fancy.

(8 COMMENTS)

Ponnuru's Corollary to Hanlon's Razor, by Bryan Caplan

Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained byI suspect economists and evolutionary psychologists with demur, but this rings true. Our modern environment is so unlike our adaptive environment that acting on impulse is usually folly.

stupidity. This sound aphorism may have a less pithy political

corollary: Never attribute to strategy what can be explained by emotion.

(1 COMMENTS)

Means-Testing Social Security: The Cohen-Friedman Debate, I, by Bryan Caplan

Cohen twice rejects means-testing on political economy grounds. In his main statement, he claims the following without evidence or even explanation:

I also oppose any wholesale substitute for the social security system, whatever its name (such as a negative income tax, a guaranteed income or what have you) that makes payments only to the poor. A program for the poor will most likely be a poor program.But in his rebuttal, at Cohen fleshes out his story.

...Mr. Friedman attacks the idea that American social security is primarily a system of redistribution of income to middle income people. Actually I think he is probably right about that. But, that is part of the system's political sagacity. Since most of the people inYou'd think these admissions would generate massive cognitive dissonance in Cohen. His view really does amount to, "Trickery is the only way to provide for the needy. Social Security is popular because voters simple-mindedly focus on their gross benefits, instead of their net benefits." But Cohen is perfectly fine with this trickery - or, as he calls it, "rhetoric."

the United States are in the middle income, middle class range, social security is a program which appeals to them. Anyhow, to the extent that he is right that there is a transfer of money from low income people to middle income people, the situation could be improved by certain changes in the financing. You don't have to do away with the entire social security system to rectify that.

But let me emphasize that the reason why the Office of Economic Opportunity and other such programs don't get appropriations, don't get support from the taxpayer, is simply that they do not appeal to the middle class, middle income person. True, if you are an economist, you may exclude all matters of politics from your thinking. But to do so is not reality, Milton. [Laughter.]

And so I say that the essence of social security, with its appeal to middle income people, is desirable and those things that are legitimately criticized about the system could easily be remedied by certain changes. My major objection to the negative income tax as a complete substitute for social security is that I am convinced that, in the United States, a program that deals only with the poor will end up being a poor program. There is every evidence that this is true. Ever since the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, programs

only for the poor have been lousy, no good, poor programs. And a program that is only for the poor-one that has nothing in it for the middle income and the upper income-is, in the long run, a program the American public won't support.

Mr. Friedman calls a lot of the things he doesn't like about social security rhetoric. And that gets me to a point I want to stress. My point is that economists do not determine all of the choices and options and attitudes prevailing in this nation. People do live by rhetoric. You can't understand what goes on in the United States if you don't understand something aboutIn any case, Cohen is just factually wrong about the sustainability of expensive, means-tested programs. The American public supports vast spending on programs that target the poor, and has done so for decades. Medicaid alone costs hundreds of billions of dollars a year. And if you're inclined to pardon Cohen for mistakenly forecasting the future, remember that when he spoke, plenty of expensive means-tested programs had been around for decades.

rhetoric. And think of all the people in this audience who would be out of a job if we didn't have such a thing as rhetoric. [Laughter.]

I believe in rhetoric because it makes a lot of things palatable that might be unpalatable to economists. [Laughter.]

I rarely criticize economists for underestimating the American voter. But Cohen forces my hand. Trickery does sustain universal social programs, but transparently selective social programs can and do flourish at the same time. As former HEW secretary, he must have known this, so I guess we should interpret his mistakes as "rhetoric."

(2 COMMENTS)

January 24, 2016

The Ambitious Case Against T.J., by Bryan Caplan

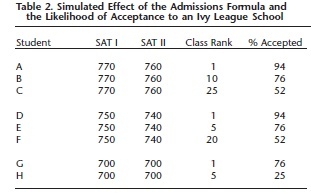

What's really going on? Stuyvesant graduate Ben Lanier recently pointed me to Paul Attewell's eye-opening "The Winner-Take-All High School" (Sociology of Education, 2001). Bottom line: Correcting for student quality, elite high schools hurt students' prospects for elite college admission. Why? Because colleges put heavy weight on high school class rank:

[F]ormulas used by elite colleges in the admissions process, especially an emphasis on class rank in high school, create a higher hurdle for students who are educated in public high schools where there is a high concentration of talented young people in one school. Students who have excellent test scores and high grade point averages (GPAs) from rigorous courses but are not at the top of their class are downgraded by these formulas. For such students, entry into elite colleges from star public schools requires higher test scores than entry from elsewhere.Attewell begins by using Dartmouth's published admissions algorithm to run some simulations, noting that "there is a high degree of agreement between admissions decisions using this method and decisions made by other highly selective colleges that use the same basic inputs but in a slightly different way."

The formula calculates an AI by combining three components: SAT I scores, SAT II scores, and the student's class rank in his or her particular high school.Illustrative results:

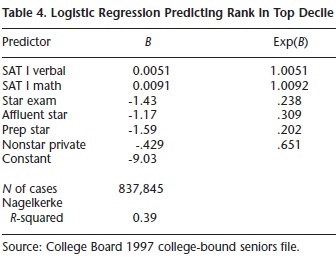

To complete the argument, Attewell shows that class rank works in the obvious way. Being the biggest fish in the biggest pond is hard.

Translation:

The odds of being in the top decile for a student in an exam star public school was only 24 percent of the odds of a student with the same SAT scores from a nonstar public school (the reference category). The odds of a student from a nonexam star public school being in the top decile was 30 percent of the odds of an equivalent-scoring student in a nonstar public school.Attewell covers a range of other fascinating issues, including elite high schools' perverse efforts to discourage their locally-mediocre-but-absolutely-outstanding students from taking Advanced Placement courses. Don't just read the whole thing. Rethink your children's educational strategy. I know I am.

(8 COMMENTS)

January 21, 2016

Forgetting How to Drive in the Snow, by Bryan Caplan

Related thought: At first glance, snow driving is a physical skill, which would normally decay at a relatively slow rate. But on second thought, it's mostly cognitive. Remembering to drive slowly and leave buffer zones is a matter of concentration, not dexterity.

HT: Dan Lin

DC handles one-inch of snow with the same efficiency that it uses for running the country pic.twitter.com/YDYGDIdeyF

-- Daniel Lin (@DLin71) January 21, 2016

(12 COMMENTS)

January 20, 2016

Forgetting: The Basic Facts, by Bryan Caplan

Skill decay refers to the loss or decay of trained or acquired skills (or knowledge) after periods of nonuse. Skill decay is particularly salient and problematic in situations where individuals receive initial training on knowledge and skills that they may not be required to use or exercise for extended periods of time.So what's known about skill decay? Common sense checks out.

1. Time matters. "There is an increase in the amount of skill decay as the length of the nonpractice interval increases."

2. Physical skills decay slower than cognitive skills. "[P]hysical tasks display less skill decay than cognitive tasks, and the difference in decay is close to half a standardized unit... across all retention intervals."

3. Speed tasks decay more slowly than accuracy tasks. "Across all retention intervals, the amount of skill decay for accuracy tasks was over three times higher than that of speed tasks (i.e., [effect size] = -1.00 and -0.32, respectively)." Learning to do something rapidly stays with you longer than learning to do something correctly.

4. Ability to transfer knowledge decays faster than mere retention. "[S]kill decay [is] negatively associated with the level of similarity between the original learning and retention contexts."

Big takeaway:

[T]he amount of skill loss ranges from a d [effect size] of -0.1 immediately after training (less than one day) to a d of -1.4 after more than 365 days of nonuse. That is, after more than 365 days of nonuse or nonpractice, the average participant was performing at less than 92% of their performance level before the nonpractice interval.And:

The results of this study suggest that the similarity of the training (acquisition) and work (retention) environments plays a major role in the retention of skills and knowledge over periods of nonuse or nonpractice, providing additional support for a basic tenet in training-program design - that is, to enhance retention, trainers should try to ensure the functional similarity of both the training device (acquisition) and actual job equipment (retention) and the environment in which both are performed.The authors don't connect their findings to pedagogical reform, but I'm happy to pick up the slack. If you really want kids to acquire a cognitive skill, don't just teach it to them and move on. You have to maintain the skill not just with practice, but with distributed practice. The iconoclastic flip side: Cognitive skills that aren't worth endlessly practicing probably aren't worth learning in the first place.

P.S. Don't forget these facts. They're important!

(0 COMMENTS)

January 19, 2016

The Missing Moods, by Bryan Caplan

Yes, the desire to feel any specific mood can lead people into error. At the same time, however, some moods are symptoms of error, and others are symptoms of accuracy.In sum:

When

someone expresses his views with a calm mood, you consider him more

reliable than when he expresses his views with an hysterical mood. We

give more credence to someone who discusses alleged war crimes somberly

than if he does so flippantly. As far as I can tell, this is justified.

You can learn a lot by comparing the mood reasonable proponents would hold to the mood actual proponents do hold.How important is this insight in the real world? Very. For many popular positions, the reasonable mood is virtually invisible. For your consideration...

1. The hawk. Modern warfare almost always leads to killing lots of innocents; if governments were held to the same standards as individuals, these killings would be manslaughter, if not murder. This doesn't mean that war is never justified. But the reasonable hawkish mood is sorrow - and constant yearning for a peaceful path. The kind of emotions that flow out of, "We are in a tragic situation. After painstaking research on all the available options, we regretfully conclude that we have to kill many thousands of innocent civilians in order to avoid even greater evils. This is true even after adjusting for the inaccuracy of our past predictions about foreign policy."

I have never personally known a hawk who expresses such moods, and know of none in the public eye. Instead, the standard hawk moods are anger and machismo. Ted Cruz's recent quip, "I don't know if sand can glow in the dark, but we're going to find out" is typical. Indeed, the hawks I personally know don't just ignore civilian deaths. When I raise the issue, they cavalierly appeal to the collective guilt of their enemies. Sometimes they laugh. As a result, I put little weight on what hawks say. This doesn't mean their view is false, but it is a strong reason to think it's false.

2. The immigration restrictionist. Immigration to the Third World to the First World is almost a fool-proof way to work your way out of poverty. The mechanism: Labor is more productive in the First World than the Third, so migrants generally create the extra riches they consume. This doesn't mean that immigration restrictions are never justified. But the reasonable restrictionist mood is anguish that a tremendous opportunity to enrich mankind and end poverty must go to waste - and pity for the billions punished for the "crime" of choosing the wrong parents. The kind of emotions that flow out of, "The economic and humanitarian case for immigration is awesome. Unfortunately, there are even larger offsetting costs. These costs are hard to spot with the naked eye, but careful study confirms they are tragically real. Trapping innocents in poverty because of the long-run costs of immigration seems unfair, but after exhaustive study we've found no other remedy. Once you see this big picture, restriction is the lesser evil. This is true even after adjusting for the inaccuracy of our past predictions about the long-run dangers of immigration."

I have met a couple of restrictionists who privately express this mood, and read a few who hold it publicly. But in percentage terms, they're almost invisible. Instead, the standard restrictionist moods are anger and xenophobia. Mainstream restrictionists hunt for horrific immigrant outliers, then use these outliers to justify harsh treatment of immigrants in general.

3. The proponent of labor market regulation. Labor regulation obviously isn't the main reason why workers receive decent treatment from employers; after all, most workers receive notably better conditions than the law requires. And labor regulation has a clear downside: Forcing employers to treat their employees better reduces the incentive to employ them. This doesn't mean that labor market regulation is never justified, but the reasonable pro-regulation mood is humility about the size of the gains plus wonder that even modest gains are on the table. The kind of emotions that flow out of, "Of course worker productivity, not labor market regulation, is the most important determinant of workers' standard of living. And of course regulation has some disemployment effect. But strangely, that disemployment effect turns out to be small - even in the long-run. As a result, labor market regulation usually makes workers better off even taking the downside into account. The evidence is so strong that it overcame our initial presumption that the downside was serious, especially in the long-run."

This mood is essentially non-existent among non-economists, and rare among pro-regulation economists. The latter, to their credit, take the downsides seriously enough to try to measure them.* But their mood does not inspire trust. They don't sound surprised that the law of demand coincidentally breaks down just when they hoped it would, or stressed that they might have failed to account for long-term damage. This doesn't prove they're wrong, but even the intellectually strongest proponents of labor market regulation are hard to take at face value.

As you can tell, I'm not a hawk, an immigration restrictionist, or supporter of labor market regulation. Are there any "missing moods" that put my views in a negative light? Absolutely. While I'm a pacifist, I'm sad to say that many avowed pacifists actively sympathize with evil regimes they don't want to fight. Similarly, while I think libertarian policies are great for the truly poor, I've often heard libertarians privately sneer at the poor, without even a token effort to distinguish the deserving from the undeserving. The prevalence of these moods doesn't prove pacifism and libertarianism false, but both are bona fide reasons for people to distrust pacifists and libertarians. So what? Again: If you have good reason to distrust the messenger, you have good reason to doubt the message.

* But not seriously enough.

(1 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers