Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 117

August 3, 2015

The Ethics of Terminus, by Bryan Caplan

In zombie survival sensation The Walking Dead, the protagonists are captured by a community of hipster cannibals. The community is called Terminus; its members, Terminants. Their business model:

1. Lure human survivors to their compound with radio and billboard messages along the lines of: "Sanctuary for all. Community for all. Those who arrive survive."

2. Welcome the survivors, disarm them, then imprison them.

3. Eat them.

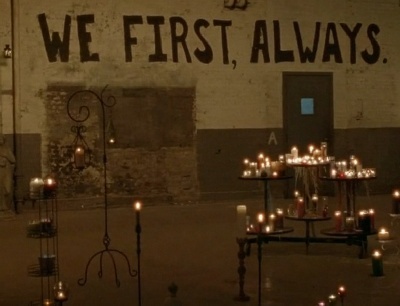

The victims naturally regard the Terminants as evil. Almost everyone who sees the show does the same: Yes, the Terminants are scared and hungry, but that doesn't justify murder. The Terminants, however, are self-righteous. They even have an elaborate shrine (pictured above) that honors the dead members of their community and proudly displays their catechism. They're self-conscious citizenists: "We first, always." Therefore, cannibalism.

Is it fair to use Terminus as a reductio ad absurdum of citizenism? Maybe. The more interesting question to my mind, though, is whether - faced with conditions as dire as The Walking Dead's - most people would adopt the ethics of Terminus.

Frankly, I suspect they would. It wouldn't happen the day after the disaster, or even the month after the disaster. But as the cost of ethical behavior rose people would gradually shed their universalistic scruples. Would they convert to ethical egoism? Unlikely. Human beings are naturally social. Awful circumstances would quickly build strong new group identities - leading members to embrace new scruples. Like: "We have a duty to do whatever it takes to protect our group." Sliding down the slippery slope from "protection" to "getting food" to "stealing food from outsiders" to "making outsiders food" wouldn't take too long.

This is especially clear if you picture how most people would respond if most people in their group turned to cannibalism. The initial reaction might be, "That's horrible." They might even skip a few meals rather than eat people. But in an extremely dangerous world, few people would leave the tribe. Once they decide to stay in a group with cannibals, most people would eventually come around to, "Well, it's okay to eat the meat as long as I don't personally murder anyone." After a few months of eating out of the cannibals' hands, justifying cannibalism with "We have a duty to do whatever it takes to protect our group" would sound pretty good.

To my mind, it doesn't morally matter that most people would ultimately embrace the ethics of Terminus. Human weakness is all around us. Murder might be morally permissible when the benefits massively outweigh the costs, but "That innocent man could feed all ten of us for a week" certainly doesn't qualify. What we learn from Terminus, rather, is not merely that most people are citizenists at heart, but that most people are only one complete disaster away from extreme citizenism. It's not only fair to ask explicit citizenists, "What's wrong with Terminus?" It's fair to ask almost anyone.

Question for discussion: How evil are the Terminants, really? Please show your work.

(16 COMMENTS)

Converting Ordinary Language to Probabilities: CIA Edition, by Bryan Caplan

Dear Prof. Caplan,

Your recent attempt at a wager on Iran's nuclear progress,

and the subsequent exchange with the author about why you wanted 10:1 odds

reminded me that the CIA tried to quantify what certain claims meant:

100% Certainty

The General Area of Possibility

93%

give or take about 6%

Almost certain

75%

give or take about 12%

Probable

50%

give or take about 10%

Chances about even

30%

give or take about 10%

Probably not

7%

give or take about 5%

Almost certainly not

0% Impossibility

It's from a 50-year old CIA proposal.

It's interesting to me that "Almost certain" was

only 93%. I think the CIA would have argued that you should have been asking

for even longer odds given the original claim.

Cheers, Todd

Proebsting

(11 COMMENTS)

July 28, 2015

Nuclear Iran Bet Update, by Bryan Caplan

@bryan_caplan I'll bet you but why such long odds?

-- John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) July 28, 2015

.@jpodhoretz I propose long odds because you claim very high confidence ("effectively ensures"). I don't.

-- Bryan Caplan (@bryan_caplan) July 28, 2015

@bryan_caplan Already hedging your bet and there isn't even one! Bock bock bock!

-- John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) July 28, 2015

.@jpodhoretz I'm not too chicken to admit my ignorance. Are you?

-- Bryan Caplan (@bryan_caplan) July 28, 2015

@bryan_caplan I'm too bored to play Twitter with you

-- John Podhoretz (@jpodhoretz) July 28, 2015

My offer remains open. And I'm happy to negotiate the terms. O ye of great knowledge, come take my money!.@jpodhoretz Betting is a great substitute for fruitless argument. Sign here and the bet is on.

-- Bryan Caplan (@bryan_caplan) July 28, 2015

(2 COMMENTS)

Nuclear Iran Bet, by Bryan Caplan

The United States and its allies have struck a deal with Iran thatSuch supreme confidence cries out for a bet. Draft terms: John gives me 10:1 odds that Iran possesses a nuclear weapon by July 31, 2025 according to (a) any major U.S. newspaper (NYT, WSJ, up to three others of John's choice) or (b) any major international agency (Atomic Energy Commission, U.N., up to three others of John's choice). If this happens, I immediately owe him $100. Otherwise, he owes me $1000 on August 1, 2025.

effectively ensures that it will be a nuclear state with ballistic

missiles in 10 years, assuming Iran adheres to the deal's terms, which

is a very large assumption.

I'm happy to make the same bet with any prominent individual on their honor, or with anyone willing to prepay me. (When the bet starts, PayPal me whatever you owe me if you lose. If you

win, I refund your money + whatever I owe you + some interest if you

like).

(13 COMMENTS)

July 27, 2015

Party in the Street: A Tale of Three Movements, by Bryan Caplan

[T]he antiwar-Democratic relationship is an intermediate case among these three party-movement pairs. The antiwar movement was more closely connected with the Democratic Party than was the Occupy movement, but it was considerably less bonded than were the Tea Party and the Republican Party. Thus, we believe that it is reasonable to conclude that our conception of the party in the street extends beyond the antiwar-Democratic case...The generality of the protest cycle:

When compared with the Tea Party and Occupy movements, the antiwar movement had an intermediate degree of overlap with its closest major-party ally. At the peak of party-movement synergy after the 2006 congressional midterm elections, slightly more than 50 percent of antiwar activists identified as members of the Democratic Party (see Figure 4.3). The results of our interviews with Tea Party and Occupy activists reveal that the Tea Party had a somewhat higher level of partisan fidelity (58 percent), while Occupy had a

lower level of fidelity (30 percent). The antiwar movement differed notably from Occupy in that the antiwar movement embraced lobbying and electoral involvement, whereas Occupy did not. The antiwar movement could be considered to be roughly on par with - if not superior to - the Tea Party movement with respect to lobbying and legislative work. The Tea Party and antiwar movements both sparked the creation of legislative caucuses, sponsored grassroots lobby days, hired professional lobbyists, and championed signature legislation (which mostly failed to become law). In the electoral arena, the antiwar movement and the Tea Party can each reasonably claim to have helped to swing the balance of power in one congressional election (2006 for the antiwar movement and 2010 for the Tea Party movement).

The Tea Party was unambiguously more aggressive than the antiwar movement in sponsoring candidates and attempting to influence party primaries. There are several notable cases of antiwar-movement-inspired candidates - Ned Lamont's attempt to unseat incumbent Democrat Joe Lieberman in the 2006 U.S. Senate election in Connecticut (Pirch 2008), Cindy Sheehan's bid to defeat Democrat Nancy Pelosi in the 2008 election for California's 12th district of the U.S. House of Representatives (Ewers 2008), and various antiwar candidates who sought the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 2004 and 2008 (e.g., Howard Dean, Dennis Kucinich, Barack Obama). Yet, antiwar electoral efforts do not compare to the pervasive attempt by the Tea Party to remake the Republican Party through the primary process. Tea Party-affiliated organizations endorsed at least 201 Republican candidates in the 2010 Republican primaries, of whom 74 percent were nonincumbents (Bailey, Mummolo, and Noel 2012, p. 773). Tea Party organizations made across-the-board moves to become players in the Republican Party in ways that the antiwar movement never did in the Democratic Party.

The protest cycle of the antiwar movement (see Chapter 2) bore some similarity to the protest cycle of the Tea Party. Both the antiwar movement and the Tea Party saw grassroots participation in their causes plummet after congressional elections that appeared to respond to their concerns. In both cases, the removal of a partisan threat served to pacify the movements. Antiwar protests, however, persisted somewhat longer than did Tea Party protests. While the Tea Party grass roots were appeased by a congressional victory alone, antiwar protests did not abate fully until a Democrat was elected president. We can only speculate as to the reasons for this difference. It could be the antiwar movement was fixated on President Bush - as the commander in chief of the armed forces - while the Tea Party was more content to stop the progress of new legislation, which was closer to their substantive grievances (on taxes, spending, debt, and health care). The Occupy movement, on the other hand, appears to have had little correspondence with partisan rhythms. The mobilization of the antiwar movement post 2008 somewhat resembles Occupy. This correspondence may result from a rise in antipartisanship in the antiwar movement after 2008 (see Figure 4.3), which placed the antiwar and Occupy movements on par with respect to this factor.Heaney and Rojas never cite Robin Hanson, but Party in the Street is definitely a Hansonian book. They could easily have titled their conclusion "Politics is not about policy." Indeed, they could have titled the whole book "Movements are not about moving."

The evolution of the antiwar movement similarly follows an intermediate path when compared to Occupy and the Tea Party. If we were to regenerate Figure 7.5 to include party-movement associations for the antiwar movement and the Democratic Party from January 2003 through December 2006, we would find that the antiwar movement tracked the Tea Party in the early months of its existence but then followed the Occupy movement as the movement evolved beyond its first year.12 As is the case for the Tea Party and Occupy, antiwar-Democratic associations trended upward in the first year of the movement. After thirteen and fourteen months, antiwar-Democrat associations in newspaper articles rose to an average of 60 percent, matching Tea Party levels at that stage of the movement and far surpassing the highest threshold reached by the Occupy movement. Nevertheless, antiwar-Democratic associations settled into an average of about 28 percent in the second through fourth years. This level was below the rate of Tea Party-Republican association, but above the rate of Occupy-Democratic association.

P.S. I'll be away the rest of the week, attending GenCon in beautiful Indianapolis. If you see Team Caplan there, please say hi. :-)

(4 COMMENTS)

Finishing an Econ Ph.D.: The Basic Facts, by Bryan Caplan

[Larger-print version of the table here]

Key observations: Completion rates vary heavily by school rank. In top-6 programs, 33% finish in five years, and 75% finish in 8. In programs ranked 7-15, rates are almost as high: 32% in five years, 71% in eight. Outside of the top-15, rates crash. Much but not all of the completion gap appears in the first two years of the program.

Of course, if you're contemplating a Ph.D. in economics, you won't be satisfied with simple bivariate results. What happens if you regress completion probabilities on a wide range of traits? The results are extremely messy. There are so many independent variables and sufficiently few observations that almost nothing has statistically significant effects on completion - including school ranking.

At least in my view, however, Stock et al. controlled for so many program characteristics - including "program-level two-year attrition rare"! - that it's hard to interpret this result. I would have rather seen regressions that controlled for program tier (or precise rank), student characteristics, and that's it.

In the absence of such regressions, here's how I'd interpret the results: If you're good enough to get into a top program, but choose a lower program, your odds of completion probably remain high. But if, like most Ph.D. students, you plan to attend the best program that accepts you, Table 1 provides good estimates of your prospects. Caveat emptor.

(2 COMMENTS)

July 23, 2015

Law School: No News Is Bad News, by Bryan Caplan

You can find a version of each school's employment statistics on the ABA's website. In addition, a school should have even more detailed employment and salary numbers for its most recent classes on its own webpage. (If a school doesn't publish this information in a way that allows you to fairly evaluate how well its graduates are doing, do not apply to it.Again, with feeling:

Here again you should apply a bright line rule: Do not consider applying to any school that does not publish reasonably comprehensive data regarding the salaries obtained by its graduates. "Reasonably comprehensive" means the following: the school must reveal the percentage of graduates in a class for which it has such data, along with the distribution of salaries in terms of medians, means, and percentiles.Third time pays for all:

Here's a simple rule: if a school won't share some piece of information you need to help you understand what its graduates end up doing, and how much they're paid to do it, don't apply.Confession of a professor of something other than law: As far as I can tell, B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. programs make law schools look transparent my comparison.

(0 COMMENTS)

Sadie Hawkins Rant, by Bryan Caplan

[T]he practical basis of Sadie Hawkins Day is one of simple gender role-reversal.Nowadays, gender roles are pretty flexible. Ideological roles, in contrast, seem more rigid than ever. Hence, the main role reversal I'd like to see: For just one day, criticize people on "your" ideological side instead of "their" ideological side. All day. Full sincerity. No irony. No mischief. No Strauss. Just candid independent fault-finding, written as politely as you usually address your ideological opponents.

Women and girls take the bold initiative by inviting the man or boy of

their choice out on a date--almost unheard of before 1937--typically to a

dance attended by other bachelors and their assertive dates.

Maybe like this.

(6 COMMENTS)

July 22, 2015

My Enthusiastic Support for Open Borders, by Bryan Caplan

1. When Noah describes the economic benefits of immigration, he makes it sound redistributive: Our GDP goes up because we gained people, which presumably means the sending countries' GDP goes down by the same amount because they lost people. At least that's the natural way to read this passage:

The point I'm confident Noah grasps, but fails to communicate: Due to vastly higher labor productivity in the U.S., U.S. GDP would rise more than sending countries' GDPs would fall.* Any chance you can write a followup explaining this, Noah? Please please please.The way to get 4 percent growth is open-borders immigration policy.

Gross domestic product is simply the product of output per person and

the number of people. The more people in your country, the higher the

output. That's why China, whose output per person is only about a

quarter of the U.S.'s, is now the largest economy on the planet. It just has more bodies.The

growth numbers you usually hear about in the news are total GDP growth

numbers, not per capita figures. To boost those numbers, get more

population. For example, when Great Britain conquered India, the GDP of

the British Empire went way up. If the U.S. really wanted to supercharge

its GDP numbers, it has a much better option than military conquest --

it could simply invite tons of immigrants to move here.

2. Noah generously hands me some free publicity, but what he says isn't quite right.

Exactly this sort of open borders immigration policy has received enthusiastic supportActually, I believe in open borders for both reasons, and many others. Yes, I have a moral presumption against regulation in general. But regulations that impoverish billions are much worse than regulations slightly harm hundreds.

from a dedicated core of libertarian economists, notably Bryan Caplan

of George Mason University. These economists believe in relaxed

immigration rules not because they want higher GDP growth, but because

of principle -- they view national borders themselves as an unacceptable

form of government intervention in the economy.

Noah continues:

The open bordersHere's what I previously said about Vivek:

crusaders are so zealous that moderate supporters of increased

immigration, such as tech entrepreneur Vivek Wadhwa, are often the targets of their ire. University of Chicago economist John Cochrane has also voiced support for the open borders idea.

I'm glad the world has moderately pro-immigration thinkers like Vivek. IThat's zeal? That's ire?

don't think the heretic is worse than the infidel. Even baby steps

towards open borders are steps in the right direction.

* This is true even though U.S. per-capita GDP would go down! Under open borders, both current residents and new arrivals would be richer. The

composition of the population would however heavily shift toward low-skilled

workers.

Example: Suppose initially, a country has 100% high-skilled

natives earning $40,000 a year. Low-skilled foreigners earn $1000 a

year in their home countries. After open borders, the U.S. population

shifts to 50% high-skilled natives earning $50,000 a year, 50%

low-skilled foreigners earning $10,000 a year. All individuals are

richer. But U.S. per-capita GDP just fell from $40,000 (1*$40,000) to $30,000 (.5*$50,000 + .5*$10,000).

(17 COMMENTS)

July 21, 2015

What's Wrong With Law Professors, by Bryan Caplan

It's not merely that it's common for a law professor to have never tried a case, or negotiated a deal, or drafted a real-life version of the sorts of documents he's discussing in a Contracts, or Corporations, or Wills and Trusts class - it's that legal academics almost never know anything about the business side of legal practice. The two most important practical skills that any lawyer working in private practice must possess are the ability to acquire clients, and to get them to pay their bills, which happen to be two things that most legal academics have never done in their lives.Rule of thumb: The more you know about any specific kind of "vocational" education, the less vocational it looks.

(7 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers