Doug Lemov's Blog, page 5

May 1, 2024

My England Travelogue Part 3: A Really Wonderful CFU Workshop in London

Participants discussing a video at our London workshop…What an amazing group!!

Last week I shared two blog posts here and here about my week-long trip to England the week prior, in which I visited two really fascinating schools.

The week ended with a two-day workshop in London on the topic of Checking for Understanding, co-sponsored by Ark Schools (thank you Victor Voutov, the king of workshop logistics!). My co-facilitator was the outstanding Jen Rugani, on whose behalf I can confidently say: We loved leading this workshop!

Participants’ level of insight, knowledge and commitment to student outcomes was equaled only by their willingness to enthusiastically engage in practice and learning.

A couple of my own personal takeaways from the workshop

The Power of Double Practice for Reflection

Jen and I tested out a new model of practice that we call ‘double practice.’ We used it when practicing the skill of cueing our Means of Participation… that is, reliably signaling to students how we wanted them to answer a given question. The “double” part refers to the idea that we each went twice with a bit of reflection in between.

So, when we modeled the practice Jen started, practicing cueing students to an Everybody Writes prompt, for example, after which I did the same. But then before we went on to practicing cueing a new MOP, we added another round where we practiced again and before hand would each reflect on 1) how we were going to try to practice differently the second time around (“this time I want to try adapting it for a little more of a challenging prompt so I’m going to be attentive to my tone of voice and try to make it sound interested and curious”) or 2) what we wanted to take or steal from the other person’s practice (“I really liked the way you said we’d hear from a variety of voices” afterwards which let me know you might be cold calling. I’m going to try to steal that.”) Then we’d practice again.

It took a bit longer—both in our model of the activity and in the time we had to allocate to it in the workshop–but we felt really strongly that it was worth it because it socialized participants to be attentive to adaptation: what and why and how am I changing or adapting what I am doing to the context or the question. It caused people to practice decision-making and meta-cognition and reduced the risk of more mechanical practice.

It’s worth noting that we were able to do this because the group was advanced and skilled at the basics already. With a group of NQTs we might have done something more straightforward, at least at first.

One participant offered this reflection, which helped us to see additional benefits:

“REALLY loved the double deliberate practice. I think it lowers the stakes because you know if your first one is weird or rubbish, you can immediately try and do better. It’s just better for your learning too, to have more opportunities to try it. Also love the flex that more expert teachers could try things multiple ways/try their usual way v a new way etc. – will help to maintain buy in from our TLAC old-timers!”

So we’re sold on this slightly deeper dive into practice with each participant practicing, reflecting on adaptation and then practicing again.

The ‘Benefits and Limitations’ Reflection

Another activity that we used in a new way was something we call “benefits and limitations.” This is an activity in which, after discussing one or more techniques, we ask participants to reflect on what value they add and how they are limited. It’s designed again to cause maximum reflection on what technique why and when. I think this applies to almost any technique. The risk of having a hammer is that you suddenly think everything is a nail. And so it’s a really useful exercise.

We applied it to mini whiteboards specifically.

To be clear, I really like mini-whiteboards and think they can be an excellent tool. So when we discussed their benefits, we talked about how easy they made it to check for understanding with a large group, how they could allow you to do so while maintaining the pace of instruction, how something about their use felt formative and low stakes in nature. Hooray for all that.

But a beneficial tool overused can be a liability and I must honestly say that I have seen mini-whiteboards occasionally overused.

For example, because they are so easy to use and they involve all students (or can!) they are often the easiest way for a hesitant teacher to cause a plausible level of interaction. And so, arguably, they can become a little bit of a crutch. Because they are easy and achieve a basic level of engagement, they can allow you not to use the higher risk moves of Turn and Talk or hand raising or Cold Call that a teacher would ideally also use.

Or consider that the writing on MWBs is disposable. It is erased as soon as it is done, and that’s fine sometimes but for something important (a key definition; a summary of a discussion) I might want students to be able to refer back to it or even re-write it. So the disposability also has downsides.

So too does the fact that it often socializes scrawling… fast slightly less attentive writing as compared to slower deliberate more memory building writing. Even the boards themselves, which are sometimes so well-used that they are more mini gray boards than mini white boards, as in the picture below, can make them feel hasty and the writing less than fully important.

Again this is the flip side of the formative low-stakes benefits.

The idea is not that MWBs are inherently good or bad but that they have benefits and limitations and I want to be aware of them so I can match them to the context.

The benefits and limitations activity does that and our group in London was brilliant in their insights.

Other Moments of Insight from the Workshop.

A teacher at the workshop had a really interesting observation about Do Nows… he noted that what starts out as a short intro to the lesson often becomes the lesson–that is it lasts 20 minutes–when it reveals misunderstandings. He observed that this was less likely to happen when the Do Now was 1) on a topic separate from the main lesson and 2) a review of previous errors (as you are describing here).

By choosing and planning for the error you’re less likely to be caught off guard for it and try to think up a solution in the moment. You can keep your do now to 5-7 minutes because you’ve planned the error and your re-teach already. And you know it’s coming.

Anyway I thought that was a great observation.

Another participant was reflecting on disincentives to Check for Understanding. If you asked really substantive questions she noted, you were likely to uncover big misconceptions or gaps in understanding. This would require a large fix and perhaps some psychological distress. The incentives for many teachers then were to ask simpler smaller CFU questions along the theme of be careful of asking questions you’re not prepared to deal with the answers of.

And I’m not sure I know the solution—other than consciousness of the issue itself possibly being mildly curative—but I thought it, like so much of what we talked about with our lovely colleagues, was deeply insightful.

Next Up: Bristol

Anyway our next England-based workshop will be in June, in Bristol https://www.olympustrust.co.uk/News/Teach-Like-a-Champion-Conferences-24-25-June-2024/ and we hope you can join us.

The post My England Travelogue Part 3: A Really Wonderful CFU Workshop in London appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

How Scott Wells Checks for Understanding as His Students Read (with Video)

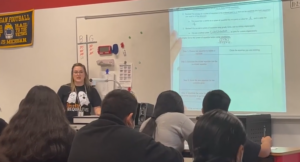

Scott in action…

We recently shot an amazing round of video in Scott Wells’ classroom at Goldsmith Primary Academy in Walsall…. We generated clip after clip of masterful teaching several of which we’ve already begun sharing in workshops.

In fact I had the pleasure of showing a clip of Scott Checking for Understanding to participants at a session for ConnectED, which is a PD collaboration between The Two Counties Trust and Beckfoot Academies Trust, yesterday evening.

Thought I’d take it as an opportunity to share this outstanding clip with the rest of you.

Scott is reading The Firework Maker’s Daughter with his year 5s (4th grade in the US), and as they read aloud together (hooray!) he pauses to check for understanding.

You can see he’s planned this moment carefully because he’s chosen the exact sentence he thinks students might misunderstand and he’s prepared to project it to the class.

“When I say go, I want you to take three minutes to jot down your thoughts. Why might Lalchand not be worried?”

A couple of key details:

First I love the midstream CFU–in the course of reading–and I love that he is assessing students’ understanding directly from the text, ie before they have talked about it. A common pitfall of checking for understanding in reading classes is that the CFU comes after students have talked about the text and heard their fellow students’ insights. Once you’ve sat in on the discussion it’s pretty easy to describe the events in the book in a way that makes it appear that you read it successfully. Believe me I know… I did that more than a few times as a student (!). But whether they understand the book is a different question from whether they are able to generate meaning from it directly from the reading. This is an insight that is useful beyond reading classes, I think:

In science class you look at a data set. You talk about it. Then you ask to check for understanding: What does the data tell us? That’s a great move. I want students to be able to incorporate insights from the class into their own understanding. But I also want to make sure they can make sense of data directly and on their own without the support of peers as they will sometimes be asked to do. I could imagine something similar reading primary texts in history.

Scott’s language in releasing students to the writing task is aces, in my book. There are phrases that deliberately lower the stakes and signal that we are still in a formative place where understanding is developing. “Jot down” your thoughts (versus “write them” or “explain them”); Why might Lalchand not be worried (versus why “is” Lalchand worried). These make students feel like they don’t have to have everything figured out yet.

In the session with ConnectEd, participants reflected quite a bit on the tension between speed and thoroughness in Checking for Understanding. Scott wants data on the thinking of as much of the class as possible but he needs to move quickly and not bog down the whole lesson in the process of checking.

He does an A+ job of that. The fact that students write allows him to circulate and read over their shoulders… he’s taking notes as he goes… so within those few minutes he’s seen just about everyone’s work and he knows what the common misunderstandings are. But because he has such strong routines for common tasks installed… as soon as he says “go” everyone is writing… they are familiar with the task so their working memory is focused on the book… and there’s no time lost… and by looking and taking notes he is able to find and use a student, Ilya, to voice a model answer.

Then when they’ve discussed it a bit, Scott does something simple but important. He sends them back to revise the work. They don’t just hear the answer from a classmate and the teacher. They re-write their own answers to make sure they’ve got it down.

Great work from Scott—more video of his class to come so watch this space!–and thanks to everyone at yesterday’s session for their insights.

The post How Scott Wells Checks for Understanding as His Students Read (with Video) appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

April 30, 2024

How Madi B. Puts Error Analysis At The Center Of Student Learning

Engineering student success.

In this second post on our work on math achievement with schools in the Memphis School Leadership Collaborative (MSLC), Joaquin Hernandez shares some of our learning from one of the champions of the MSLC, 8th grade teacher and instructional coach at Memphis Rise Academy, Madi Bienvenu.

Closing Gaps Via the Do Now

The centerpiece of our work with teachers and leaders within the Memphis School Leader Collaborative is a research-informed Lesson Delivery Model (LDM). We define this as a content-specific pedagogy document that defines how a math lesson should unfold. The Math LDM we developed follows a gradual release model, which is informed by Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, as well as findings from Cognitive Load Theory, such as the Expertise Reversal Effect.

In our experience, math curricula often provide teachers with an Exit Ticket, or similar end-of-lesson formative assessment. However, teachers are also left without much direction on where and how to address misconceptions from the previous lesson. So, as part of our LDM, we codified guidance on how MSLC teachers can prepare and execute a variety of Do Now activities—such as retrieval practice, fluency, or Error Analysis—that are responsive to formative data like Exit Tickets or quizzes. Throughout this post, we’ll share how one MSLC teacher leveraged our guidance for Error Analysis Do Nows to address common errors that surfaced on Exit Tickets.

See It in Action: Madi Bienvenu

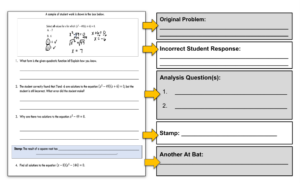

To kick off our exploration of Error Analysis Do Nows, we’d like to spotlight Madi Bienvenu, an 8th-grade Algebra I teacher and instructional coach at Memphis Rise Academy. In 2023, Madi achieved the third highest proficiency rate on the Tennessee state exam out of 69 Algebra I teachers across Memphis Shelby County Schools. In this clip, you’ll see Madi lead an Error Analysis Do Now, in which she has students analyze a common incorrect answer from a recent Exit Ticket. As they study the work, students are prompted to explain in writing what’s correct in the work and, importantly, what’s incorrect and why. What follows is a brief discussion of the error, a stamp that ensures kids capture the key takeaway from the error, and another at-bat with a similar problem.

With that, here’s Madi’s classroom:

There were a few things we loved about Madi’s teaching in this clip:

Culture of Error: Madi makes it safe for students to study and learn from this mistake through her tone and words. For example, Madi acknowledges that the work they’re studying contains a common mistake, which normalizes error. When discussing the error, she exudes calm and warmth, signaling to students that errors should not be a source of anxiety or frustration. In her eyes, they are a normal–and even valuable–part of learning. What’s more, Error Analysis is not a one-time activity, it’s a routine part of Madi’s lessons. This is why students don’t seem phased by it: they engage actively and earnestly in the discussion without defensiveness or hesitation. Finally, Madi’s use of universal language like “we” or “our” further normalizes error and emphasizes that learning from mistakes is a shared endeavor.Study Why: Madi asks students to identify the error and explain why it’s incorrect (“Why is -7 also a part of the solution?”). This helps students who initially got it wrong to better understand their error, which in turn helps them avoid making the same mistake next time. It also causes students who did get it right to deepen their understanding through elaboration and explanation. This deepens students’ learning and makes it more durable (Siegler, 2002). Means of Participation: Before students discuss the work, Madi first gives them an opportunity to independently study and process it in writing. This elevates the quality and breadth of student participation during discussion. In addition to Everybody Writes, Madi maximizes academic engagement with techniques like Turn and Talk, Volunteers, and Cold Call. We also noticed that she intentionally sends kids into a Turn and Talk to identify the error (Question #2). This is critical, as students won’t be able to engage in a productive discussion of the error if they don’t perceive it.Active Observation: As Madi circulates, she observes students’ work, collects data on student thinking, and plans who she’ll Cold Call to support the discussion. Examining students’ work also allows her to check whether students are on the right track, so she can intervene with timely feedback if they aren’t.Stamp the Learning: Madi asks students to distill the key takeaway from the discussion into one tidy, written statement with the prompt “Remind me….” This helps students avoid making the same mistake when they encounter similar problems (like the very next one!). Additionally, the simple act of having students write the stamp helps them encode it into their long-term memory and equips them with a resource they can refer back to when they encounter similar problems. Finally, we appreciated how she had students fix their work, ensuring they also leave the discussion with an accurate solution.Additional At-Bat: Madi immediately follows the stamp with an opportunity for students to apply their learning to a similar problem. This allows Madi to assess whether she successfully closed the gap, help students cement their improved understanding, and give students a chance to ultimately get it right.

Engineering Materials For Student Success

In studying classrooms like Madi’s, we realized that one of the hidden—and often unheralded—drivers of successful lessons is intentionally designed student-facing materials. As you’ll see below, Madi carefully designed this Do Now to maximize engagement, rigor, and mastery. Here were some of our biggest takeaways from how she structured it:

One of the biggest potential impediments to the success of Error Analysis is a finding from Cognitive Load Theory known as the Transient Information Effect. This occurs when students are temporarily presented with information, say in the form of text or written work, and then asked to try to recall it from memory. By embedding the problem and response directly in students’ Do Now, Madi avoids overloading students’ limited working memory, and instead enables them to devote precious cognitive resources to actually analyzing the response. This is also why we love how she includes the “stamp” and “at bat” in close proximity to the incorrect work. By keeping all of these components together on the same page, Madi makes it easy for students to do the thinking work that’s required and to successfully apply their learning.

While the content of Madi’s Error Analysis Do Nows changes from lesson to lesson, she holds the following elements constant (below):

After sharing this Do Now structure with MSLC leaders, educators at Leadership Preparatory Charter School in Memphis created a template their teachers could use to plan daily Error Analysis Do Nows. We love this resource because it helps teachers ensure that the essential components of a successful Error Analysis Do Now are always present, regardless of the gap they’re addressing.

A Coda On Error Analysis

As we saw on display in Madi’s video, one best practice that our team codified and shared with MSLC teachers and leaders is Error Analysis, which we define as an activity that teachers use to help students study, unpack, and correct a common error from a recent Exit Ticket or formative assessment. This practice is rooted in research from Cognitive Load Theory on the benefits of asking math students to study Worked Examples or fully “worked out” solutions to problems. What’s more, research has revealed that it’s not only beneficial for students to study correct work, but also to study and explain errors in incorrect work. Specifically, Error Analysis has been shown to:

Lead to deeper learning and to improve students’ performance with similar problems (Siegler, 2002)Strengthen students’ conceptual and procedural understanding, as well as their equation-solving abilities (Booth et al., 2013; Barbieri et al., 2020)Increase students’ long-term retention of knowledge (Rushton, 2018)Enhance transfer and improve students’ performance on application problems (Corral et al., 2020)

Another research-based variation of Error Analysis that teachers have had success with involves asking students to compare two Worked Examples—one that’s correct and one that’s incorrect. MSLC teachers have found that this can help students more efficiently notice the difference(s) between the two responses, which takes advantage of a phenomenon known as the law of comparative judgment. This exercise is a natural springboard for engaging class discussions about which answer students think is correct and why.

A Few Keys to Success

As Madi demonstrates, Error Analysis can be a powerful tool for addressing misconceptions and building a classroom in which students feel safe revealing and learning from mistakes. Here are some key conditions that can help teachers make the most of them:

At the “Sweet Spot”: Error Analysis works best at the “sweet spot” of difficulty. On one hand students must have enough cognitive schema to be able to engage productively in discussion. If they don’t, they may leave the discussion even more confused about what the correct method or answer even was. On the other hand, if the vast majority of the class already arrived at a correct answer, then students may disengage and little learning will likely take place. One way to strike this balance is to identify a problem that a significant percentage of the class understood the concept but made a crucial mistake in the process. It’s also important to note that if most of the class had great difficulty with a problem, or there is no clear error trend, it can often be more beneficial for a teacher to re-model how to solve it, while narrating their reasoning as they go.Low-Stakes: Error Analysis can’t be a one-time event, or something you only do to address errors from high-stakes, cumulative assessments. It works best when you use it consistently and universally. Consistency is what builds psychological safety and increases students’ openness to reflection and feedback. Balanced With Other Types: Error Analysis Do Nows are just one type that teachers should have at their disposal. In our experience, they work best when they’re used strategically, and in balance with other Do Now activities, such as retrieval practice, analysis of correct Worked Examples, mixed review, fluency practice, and more.Avoid Hiding the Ball. As we’ve noted above, students can’t analyze an error they can’t perceive. That’s why, when you’re first using this activity, it can be helpful to narrow students’ focus to the most relevant aspects of the response that you want them to analyze. Instead of starting with a prompt like “What’s incorrect?” you might consider highlighting the particular step where the mistake occurred, naming the part that’s correct so students focus just on what’s incorrect (without naming the error), or even naming the error before prompting them to explain why that’s a mistake. As students build competence and confidence with Error Analysis, and develop mastery of the skills, you may choose to remove these scaffolds. By narrowing the focus to what’s relevant, you can help ensure that this activity is both productive and efficient.

A Final Note of Gratitude

We think Madi’s classroom is a great illustration of why, as legendary coach John Wooden put it, “the most crucial task of teaching is knowing the difference between ‘I taught it’ and ‘they learned it.’” By analyzing student work and being responsive to trends with routines like Error Analysis, she ensures her middle school students experience the satisfaction of grappling and succeeding with rigorous, high-school level content. We’re incredibly grateful to be able to learn from Madi, and so many teachers like her from Memphis and around the country. Thank you, Madi, for sharing your work!

The post How Madi B. Puts Error Analysis At The Center Of Student Learning appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

April 29, 2024

Research Into Practice: The Crisis in Math Scores and Our Journey to Understand What Drives Learning

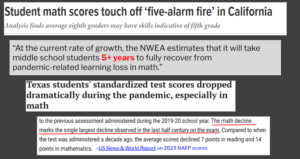

A Math Crisis: In the offing long before it made headlines…

A lot of what we do on our team boils down to wiring ourselves for learning: confronted with a teaching and learning problem, we try to assemble the right people and design the right processes to find solutions. One way we do this is though multiyear partnerships. This allows us to learn alongside school partners for a sustained period of time in which we jointly pursue solutions that improve outcomes for students.

One of the most fruitful and promising of these partnerships is our Memphis School Leader Collaborative (MSLC). Designed and led by three members of our team—Joaquin Hernandez, Jack Vuylsteke and Teneicesia White, alongside two amazing school-based leaders—Rebecca Olivarez of Memphis Rise Academy and Denarius Frazier of Uncommon Schools– the collaborative allows us to work with 13 high-quality schools and networks in Memphis.

In the first two posts of this series, Joaquin shares some highlights on how this partnership has helped us begin addressing challenges in math achievement which have subsequently become national headlines.

Background

In the wake of the global pandemic, schools across the country saw steep declines on a wide range of state and national assessments in reading and math, with the effects on math performance particularly pronounced.

In a June of 2023, article titled, “U.S. Teens’ Reading and Math Scores Feature Largest Declines Ever,” U.S News and World Reports noted, in math scores, “the single largest decline observed in the last half century.” Headlines like the ones above were everywhere. Even more troubling is that the impact on math proficiency exacerbated inequities, leaving socioeconomically disadvantaged students even further behind their more affluent peers.

The situation is urgent but its roots go back further. As the controversy surrounding California’s ill-advised and poorly researched math framework reminds us, math instruction was often poorly designed even prior to the disruptions of the past few years. And even when math programs are well designed, materials are often difficult for teachers to use.

Members of the TLAC team have been working alongside school partners for the better part of three years now to better understand what effective math instruction should look like and what the barriers are that prevent optimal implementation. We’ve studied the design, planning and delivery of math lessons in dozens of schools to connect evidence-based practices to real world challenges and have used cycles in which we filmed teachers and studied the resulting student work study to better understand how research, curriculum and pedagogy can come together to cause far greater rates of student success and achievement.

Better Together: The Memphis School Leader Collaborative

Like the rest of the country, schools in Memphis saw post-pandemic declines in math performance. To address this, coaches and math educators from the Memphis community collaborated with TLAC to form the Memphis School Leader Collaborative (MSLC). Together, we engaged in a deep study of evidence-based best practices for planning and delivering high-quality math instruction. We also coupled this training for teachers with robust support and professional development for instructional coaches. Through the generous support of the Hyde Family Foundation, Memphis Education Fund, and an anonymous donor, we grew the collaborative to 13 schools and networks this year, to collectively impact 3,800 students across Memphis.

Impact Data: On The Right Track

While the year isn’t over, mid-year data suggests we are on the right track. As of February 2024

10% more students in MSLC schools were projected to be on track to meet/exceed state grade level proficiency, equating to 117% growth in MSLC schools’ results over last year. That improvement is an estimated 360-380 additional students projected to reach state grade level proficiency targets in math. We are also solidly in range of achieving our ambitious Success Rate Goal of helping 75% of math classrooms achieve Annual Measurable Objectives (AMO), which are state proficiency goals set by Tennessee’s Department of Education. Retention data also indicates that 83% of MSLC teachers and 100% of coaches report that they plan to return to their schools next year, and a majority of those educators explicitly cited the impact of the PD and support they received around math instruction.

Schools are complex environments with many variables at play, so it’s hard to attribute results to just one intervention. That being said, we’re proud of the hard work of MSLC teachers and coaches and the academic growth they’re seeing across their math departments.

Upcoming Posts:

Over the next series of posts, we will share what our team is learning from our experience training and supporting teachers and leaders in implementing research-informed best practices. Specifically, we will:

Spotlight the work of Madi Bienvenu, an 8th grade Algebra I teacher at Memphis Rise Academy, who has participated in MSLC for the past two years, and who has helped her students achieve standout results on state exams. Explore the benefits we see from helping educators establish and implement a shared mental model for how a math lesson can unfold and the planning and preparation (with curricular materials) that drives it.Share the benefits we are seeing from bringing schools together for content-specific collaboration and the practices we are using to facilitate learning across different schools and networks.The post Research Into Practice: The Crisis in Math Scores and Our Journey to Understand What Drives Learning appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

April 25, 2024

My England Travelogue Part 2: Blaise High School, Bristol

Nabarro: Re-setting a culture is no small thing.

A few days ago I started a blog travelogue about my week in England with a summary of my trip to Ark Soane Academy in London.

The next day, Wednesday, I was in Bristol to visit Blaise High School which is a fascinating and impressive case study in turnaround. When the current leadership Greenshaw Learning Trust took over it had a minus 1.4 Progress 8 score. Lessons were constantly disrupted. It was hard to teach and it wasn’t a safe or supportive environment for students.

In the span of under two years they’ve brought Progress 8 scores to .-2.

Obviously the goal is to turn the cultural turnaround into even stronger academic outcomes and interestingly that often requires a different set of moves and priorities. Now that real teaching is happening that’s a legitimate goal. I think they’ll do it.

But first let me reiterate what should be obvious but isn’t, somehow: how nearly impossible it is to make academic progress when the culture is broken; how incredibly difficult cultural turnaround is—it’s much easier to start a school than to fix one.

There were so many details of how this was accomplished. Morning arrival is a good example.

Teachers were stationed outside the school. Not just inside the school’s gates but out on the pavement in the areas where students approached. Teachers would greet students warmly and by name (you are known here; we care about you) but would also often “fix” small problems with uniform or a reminder about phones, say, or just check in with students who looked “off” emotionally.

The result was that when students entered the school grounds they were already on the upswing. Their phones were away, they had already been reminded that the school cared about them and that expectations were a little higher inside those gates. This also gave school staff the opportunity to greet and talk to parents both their own and, interestingly, those from the local primary who often walked by as well. When those students enroll it will feel like a much more welcoming place.

Inside the gates a bright digital clock, visible from far away, was mounted on the wall of the school so it was easy to meet the expectation of punctuality. There was a room off the entry court where students who needed a belt or shoes or a tie for their uniform could get one simply and easily before school started. Unless it was a chronic issue school head Nat Nabarro said, the items were simply given to students without sanction. “We care about you but we expect things of you here.”

During this time students mingled freely and chatted inside the gates. Then, on signal, they lined up by class. Teachers worked the rows greeting students and ensuring they were ready for the day. Some of the teachers were simply masterful at striking just the right balance. You want to show warmth and caring but you are not their friend. You speak for the school and what the school does is very, very important.

A teacher then addressed each year group with greetings (it was the first day back from half term) encouragement and reminders. The school provided them with small stools to step up on so they could see and be seen (and heard) more clearly. First time I’ve ever seen that detail. Brilliant.

Each of these small pieces might seem tiny but together they add up to a cultural sea change and a coherent message. Especially (well, only) when they are matched by similar intentionality inside the school building.

It’s been a massive turnaround already and we should never dismiss or underrate how hard this is to accomplish.

Now the question is what comes next.

One thing we talked about was letting the students who are more bought in—those who (often) silently appreciate the change in culture to one that values their time and their learning and makes them safe–show their buy-in a bit more and a bit more intentionally.

The start of lessons is a great example. You could argue that the start of a lesson is almost always a norm-setting or -reinforcing moment. We signal or remind people of what the norms are. And as Peps McCrea points out the individual’s perception of the peer norm is the greatest single influence on behavior and motivation.

So the start of class is important for the social signals students send to each other.

In an environment where behavior is uncertain and can easily go off the rails, you might start class very carefully, with direct instruction a fair number of cold calls and perhaps more limited opportunities for student interaction. The primary mode of student interaction might be mini-whiteboards, say.

Nothing wrong with this but the mini white board is safe—the safest way to ask students to be involved in lessons—and quiet. It’s easy to come to rely on it. So too cold calling.

But when culture shifts, a school might want to set a norm of more active and willing engagement in lessons.

In a vibrant Turn and Talk where the room crackles to life when the question is asked, for example, participating students send a message to their peers—I am all-in for this class—and when the majority of the class does it, it becomes a norm shaping moment.

Similarly Cold Call- an excellent but also lower-risk way to involve students. Teachers should use it. But also recognize that a moment when lots of pupils raise their hands is a norm-signaling moment.

To raise your hand sends a signal to the teacher—I’d like to speak—but also to one’s peers—I care about this topic and my learning enough to want to answer. When you sit in a classroom and see a sea of hands you get a very strong norm signal. We are all all-in.

Interestingly it is often, in my experience, the more experienced teachers, the ones who’ve been a part of the previous culture, who know what can go wrong, who are most cautious about the change. They know what they risk losing if they go too far.

Blaise has been really thoughtful about the process of managing this transition. There were some exceptional lessons and some very good but slightly more cautious lessons.

But I saw some beautiful examples of teachers challenging themselves to immediately incorporate ideas from professional development. The prior week’s focus had been Active Observation and I observed as Nancy Jessiman not only taught a brilliant and rigorous lesson that students willingly engaged in, but immediately put the contents of PD to work. Asking students to write the definition of a scientific term, she had them write in their notebooks rather than on MWBs and then circulated, making comments as she went that both reinforced learning (“Excellent, John”; “Don’t for get to use the term oscillation, Sarah”) and built relationships with pupils.

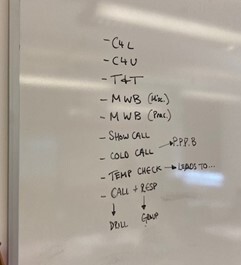

And one other tiny moment that stuck with me. On the back board in Josh Mazar’s maths class I noticed this:

It’s his “show flow”—the means of participation he intends to use in the course of his lesson. It’s a thing of beauty in my mind. First it shows preparation. He’s thought through in advance not just what content he’ll cover and what questions he’ll ask but how he’ll ask students to answer: a turn and Talk followed by two uses of mini white boards and then a Show Call, for example. Second he’s made this visible to himself throughout the lesson. Could there be a better way to remind himself of what he wants to do and to help him manage the load on his working memory.

One of my biggest personal takeaways from my new life on zoom, which started during the pandemic but is now part of all of our lives, was the power of small icons. I put them at the bottom of my slides to remind myself when to use the chat function or cold call or, as this icon reminds me, to use break out rooms:

It’s such a calming support to always know what move I’d planned. I can just glance at it to be reminded. Almost no one else knows what it means-it’s in code—but even if they did, so what.

The show flow on the back board is a brilliant version of the same idea for inside the classroom. It’s on the bac wall where he’ll see it easily as he looks at students. They can’t see it because they are looking at him but even if they did it’s mostly in code. And so it’s easy for him to stay on plan. Which makes building a plan more worth the time.

As a side not and small digression there are lots of similar ways teachers can use the back wall for coded reminders to themselves: a smiley face to remind yourself to smile, say. Or the letters NTP if you’re trying to remember to narrate the positive. Coded visual reminders in the classroom are gold for a teacher whose got a complex task and a room full of 30 students to manage.

Anyway, my visit to Blaise was a pleasure and a reminder of how critical it is to invest in getting the culture right. And then not be afraid ot make changes when you’ve begun to win that challenge.

Thanks to Nat and his amazing staff for opening their doors so completely.

The post My England Travelogue Part 2: Blaise High School, Bristol appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

April 23, 2024

My England Travelogue, Part 1: Ark Soane Academy

A bright and lovely place…

I’ve just returned a week in England in which I visited schools, talked teaching, led a workshop and learned many useful things.

I’ve decided to string together a series of posts in a sort of mini-travel-log. Starting with my visit on Tuesday to Ark Soane Academy in Acton where Pritesh Raichura was my primary host—and everybody was gracious and great conversations abounded.

It’s a lovely, lovely school. Bright and tidy; orderly, positive and caring; so intentional about teaching (very high quality) and the scaffolding of knowledge.

One of my reasons for going was my hope to be inspired. I’ve visited so many once-good schools this year that have been all but undone by their own anxiety about orderliness- a broad confusion that authority is authoritarian. I wanted to see that schools could still make culture work—ie positive and inclusive but also orderly and capable of instilling the sorts of values so most parents care deeply about- honesty, hard work-consideration for others. And that was all very evident at Ark Soane, and Principal Matt Neuberger and his staff have done such a great job building positive culture carefully and intentionally.

I also had a great chat with Pritesh about “Phases of Questioning” in a typical lesson. Lessons at Soane are designed around the three phases.

Every lesson starts with a first phase of questions designed to maximize student attention, to cause them to participate frequently early in the lesson as a matter of habit.

The teacher might make an instructional point—that the author of Animal Farm is George Orwell, say. And then ask:

“Who is the author of Animal Farm, class?”

The class would respond chorally: “George Orwell.”

“Yes. And the takes place on a farm book but it is an allegory—a story with two layers of meaning—so it is also about the Russian Revolution.

“Class an allegory is a story with what?”

Choral Response: “Two layers of meaning.”

What kind of story is it, Kylie?

“An allegory.”

Yes and where does it take place, Nika?

“On a farm”

And who wrote Animal Farm? Kevin?

“George Orwell.”

The purposes of this sort of exchange are participation, accountability and pace. The teacher is reminding students that they will be active and busy throughout the lesson, and doing so right away. He or she is also signaling accountability to pupils: You must pay attention and attend to the content—it’s worth noting that students could participate without thinking explicitly about the content and in that case they could be unlikely to learn. But if students are paying attention, these initial questions should be readily answered. The third purpose is to build pace. One thing for sure about lessons at Ark Soane is that they move, and this is important. While the mode of teaching is primarily direct instruction, for pupils they feel very dynamic because they are active and on their toes so frequently. It can have the effect of creating a sort of flow sate where students are so busy they almost lose track of time. Being in a such a state, it is worth noting, is extremely pleasurable for most people.

A second phase of questioning was focused on rehearsal and thinking but the number of questions I saw that were simply about rehearsal was interesting- in many ways the most interesting idea that teaching at Ark Soane proposed: the purpose of answering many of the questions asked in class was simply to cause students to say and remember something multiples times in hopes of building memory. This often manifested in very short turn and talks. “Remind your partner what the name of the force we are talking about is.” “Tell your partner of the formula we use here to find the sum of the angles.” Sometimes this information might be on the board or in students’ notes, sometimes it asked for a summary of a much larger body of information but the idea was to get them to rehearse it or explain it to build memory and fluent recall.

The last phase of questioning was about Checking for Understanding. These came later in the lesson with the purpose of assessing whether students understood the thing the teacher was explaining or modeling. Mini whiteboards among other tools were often used for this.

Training and support materials at the school discuss not only how to execute these various phases of questioning but potential pitfalls and dangers. For phase two questions (rehearsal and thinking), for example, teachers were warned to be careful of “excessive parroting and little thinking”; “rehearsing the wrong things—not the core knowledge; not making the most important links”; or, with frequently used turn and talks, one dominant partner developing.

The result of this approach was indeed fast-paced and energetic execution of direct instruction – a combination that’s often hard to achieve- and a high level of attentiveness by teachers to intentional memory building.

There was a clear model for teaching—a working theory on what would cause learning to happen grounded in cognitive science—and the model was consistently used across classes which made it predictable to students as well. I love the idea of including potential pitfalls in instructional guidance, especially pitfalls derived from experience in and specific to the school’s own model. It reflects a culture of very careful self-reflection and self-study among the staff to always ask: what’s working? what goes wrong? why?

The memory building questions in particular were especially thought-provoking. We (people? educators?) are so apt to overlook memory. We assume remembering will happen on its own even though it doesn’t. So the idea that I would ask questions merely to cause occasional rehearsal of key points during the lesson to facilitate students remembering is really interesting. Not only because it helps students to remember and to understand the importance of memory building but because it implicitly teachers them how to study better on their own later on.

It’s probably the single idea I’d be most interested to borrow and adapt from my visit. If I were going to do that, I might think about times when teaches could make the purpose explicit to students: “Tell your partner the formula so you can remember it.” I might argue for doing that at times because 1) students should know that memory is important and different from thinking or understanding and 2) sometimes the answers to memory-building questions can seem quite obvious to students. You just told us that. Why are you asking us to repeat it when we know it? Answering obvious questions could seem demeaning and odd unless you understood why you were doing it. The purpose here is different from encoding or exploring an idea; the purpose is remembering. So I think teachers reminding or telling students that is a good idea. I also might separate rehearsal questions from thinking questions as the pitfalls strike me as both the purposes and pitfalls seems potentially different. So just possibly I might argue for four phases. But I also could be wrong. Pritesh and the staff at Soane developed the idea and know a lot more about it than me. And for certain the model is a really intriguing and promising way of engineering the teaching that happens during direct instruction, specifically to make that form of teaching successful (and aligned to research.)

All In all was a lovely and thought-provoking visit that also restoring my faith that strong and positive cultures were still out there.

Next, it was on to Blaise High School in Bristol…. But for that you’ll have to wait until tomorrow.

The post My England Travelogue, Part 1: Ark Soane Academy appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

March 6, 2024

Memo Sifuentes’ Halftime Framework for Young Athletes

Memo Sifuentes

Memo Sifuentes coaches the u14s (and formerly the u12s) at Austin FC’s Youth Academy. I always find him incredibly thoughtful and intentional about the teaching part of his job.

We’ve been talking a bit over the past year about game day coaching: what to do to maximize long-term learning at halftime, in pregame talks, during the match, and afterwards.

After one of our discussions, Memo put together a ‘framework’ so there was a clear model for how things were supposed to go at halftime with his team.

I’ve outlined it, and a few of Memo’s reflections, below.

The Framework

At half time Memo’s goal is to the limit the amount of feedback players receive to manageable amounts and to delegate clear roles and responsibilities among coaches.

1. Half ends: Players getting water. Coaching staff goal: “touch every player” i.e. make them feel connected, important, supported: high five, hand on shoulder, hand shake. Divided among coaches and staff so we get to everyone.

2. Head and assistant (and other present staff) meet for 3-4 minutes.

“Intentionally regulate each other emotionally so we are prepared to talk to players.”Share notes and observations among coaches/staffDecide three priority coaching points to be shared with team. [“Usually it’s 1 attacking, one defending, and one lineup/tactical change but it also might be 2 attacking and one defending point 4) decide who will have responsibility to discuss each point with team [“Usually I do attack and my assistant does defending but but not always”].Decide together what tone we want to strike with team and what root value we want to couch it in. eg “collective” mentality. Think about the people who support you to make your success possible.

3. While coaches are meeting players in groups talking about their play – With the Under 12s, we generally divided the players into 2 groups. One group consisting of back 5 and the other of the front 5. Goalkeepers would typically join the back 5. (U12 is 9v9 and we would play 1-4-3-1) Substitutes would join the group the position they were assigned for that game. We would ask the groups to discuss and rate a game principle to help guide the player discussion.

4. Circle up. Coaches deliver three key teaching points.

5. End with “common focal point”: one clear thing we want to try to do during the first five minutes of the second half. E.g. We want ten shots; When we build let’s try to play to the right center back first…. It’s more actionable and focused and less controlling to try to shape it for just five minutes, gives players a clear goal to change behavior but then autonomy to adapt. Staff’s coaching style is dependent on if the focal point has been trained or if the focal point is ‘new’ to the team. For example, established and familiar focal point=more questioning and guided discovery; less familiar more directive.

Questions for Memo:

How’s the routine changed over time?

It felt a bit forced at first. You’re building a habit of self-discipline. It’s hard. You have to be aware of why you’re doing it. But it’s helpful and also creates a habit for the players, including their “walk to the locker room” as they self-regulate and discuss the first half. For staff, it creates important roles and responsibilities.

Can you give an example of self-regulating.

Against FC Dallas there was a yellow card to one of our players. The ref had been really inconsistent, and we got a little too caught up in it. We reminded ourselves: Focus on what we control. Control the controllables. If we focus on the ref so will the players.

When is it most challenging?

Tournaments, especially. During the season, it’s typically my assistant, S&C staff member or trainer, and at times our GK coach. During tournaments, staff increases and everyone is there to help and so they want to share their thoughts. It’s all good information but it would be too much for the kids to process. So in this case the assistant circulates five minutes before half to gather everyone’s feedback. That way we make sure the staff meeting during half time stays within those 3-4 minutes and players get manageable loads of feedback.

The post Memo Sifuentes’ Halftime Framework for Young Athletes appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

March 4, 2024

Lesson Delivery Models and Lesson Prep

In our previous three posts, we described lessons learned from our partnership with Harmony Public Schools as they endeavored to strengthen a culture of Lesson Preparation across their 60 campuses.

Our team defines Lesson Preparation as consisting of 3 core practices:

Plan the ExemplarPlan for ErrorPlan the Means of Participation

(For more on these core practices, check out previous TLAC posts on Lesson Prep here and here).

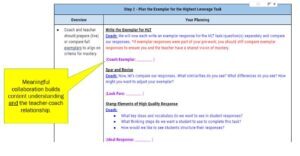

We think the three practices can be flexibly and productively applied across all grades and content areas. However, to realize the full potential of Lesson Preparation, school systems need to provide teachers and leaders with examples of the three practices embedded within a Lesson Delivery Model – a clear, content-specific vision for the instructional sequence of a typical lesson.

Lesson Delivery Models Defined

We define a Lesson Delivery Model (LDM) as a guidance document that explicitly names the vision for how a lesson in a specific content area unfolds from start to finish. Unlike the core practices of Lesson Preparation, LDMs need to be content specific because how a strong math lesson unfolds is not the same as how a literature lesson or a biology inquiry lab unfolds. LDMs make explicit the student and teacher actions that, when prepped effectively via Lesson Preparation, allow students to experience rigorous, engaging, and responsive lessons.

As part of our work with Harmony we worked with the Curriculum Directors of Harmony’s Curriculum Department to support them in defining how lessons should unfold in their respective content areas–and then codify it in a Lesson Delivery Model.

An Example LDM

One of the leaders we worked with closely is Elvia Rimer, Curriculum Director for Literacy, K-2. In the Spring of 2022, Elvia created a K-2 ELA-R Lesson Delivery Model that outlined how a K-2 literacy block should unfold. Her LDM articulated:

Core components of the literacy block with critical pacing notesThe purpose behind each component for student learningKey teacher and student actions that should be observed within each component

For Professional Development support, Elvia prioritized phonics instruction as the focus area to ensure more students within Harmony were finishing the year on or above grade-level. Working from the defined LDM, Elvia was able to live model in PD the phonics routine from start to finish so that teachers and leaders could experience the LDM they’d begun to process on paper.

With a clear understanding of the flow of a Phonemic Awareness and Phonics lesson in mind, Elvia then led teachers and leaders to analyze the lesson preparation she engaged in to support her model lesson. Teachers could then understand (via example) how Plan the Exemplar, Plan for Error, and Plan for Means of Participation worked together to support the execution of a strong Phonics lesson.

The clarity of the Phonics LDM led Harmony’s students to experience more success in the ‘22-’23 school year. Harmony’s K-2 literacy data:

Increased the number of students reading on or above grade level by 18% from Beginning of the Year (BOY) to End of the Year (EOY)Decreased the number of students needing Tier 3 support by 13%

Our work with Elvia along with other Harmony Curriculum Directors (Tiffany Ekarius, Elementary Math Director, Ismail Savruk, Secondary Math Director, Farjana Yasmin, Biology Director) provided us one of the key learnings we had in the second year of our partnership: Teachers need to see strong content and curriculum specific examples of Lesson Preparation in order to link preparation to execution effectively.

LDMs Make Lesson Preparation More Effective

Why are Lesson Delivery Models critical in the context of lesson preparation? In the absence of a Lesson Delivery Model, teachers and the coaches who support them may be operating from entirely different mental models for how the lesson unfolds–or the experienced coach may be working from a mental model of much higher clarity and precision.

In some of the early Lesson Prep coaching we observed, coaches and teachers engaged earnestly in preparing the exemplar, planning for error, and planning the means of participation but it didn’t translate into an engaging lesson that ensured success for all students. Why? The teacher didn’t have a clear understanding for how the work they had just done fit into a larger vision of instruction in their content area. Additionally, teachers and coaches, without realizing it, may be operating from different definitions of what constitutes a “successful lesson.” Situating a collaborative study of Plan the Exemplar within the defined sequence of a LDM ensures that teachers and coaches are working towards a shared understanding of success.

To return to the final lesson we named at the outset of this series: A single year of training investment does not move a system to mastery. Harmony is sustaining a multi-year commitment to internal capacity building at all levels of their organization. That level of commitment is often rare, and for us, inspiring. We are deeply grateful to Harmony Public Schools for allowing us to contribute and be partners on their journey.

The post Lesson Delivery Models and Lesson Prep appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

March 1, 2024

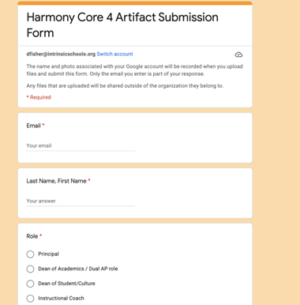

Seeing Change: Harmony’s Artifact Study System

Studying implementation with network leaders

As we’ve shared in our first and second posts, we were fortunate to partner with Harmony Public Schools as they endeavored to deliver high quality professional development systems focused on Lesson Preparation for 300+ instructional leaders across 60 campuses. In this post Dan Cotton and Dillon Fisher discuss how they worked with Harmony to develop and refine systems to constantly assess how professional development was shaping outcomes in the classroom:

One key to successful organizational change (in organizations both small and large) is to build strong systems for studying progress. Successful professional development is more than a sequence of events; it also has to include a process for self-study and learning.

For example, school leaders need to be able to answer:

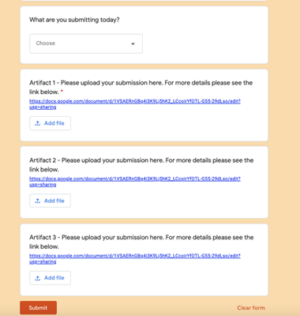

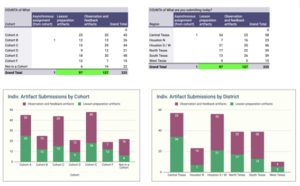

What’s going well? What are the opportunities?Where are early Bright Spots that can be used to set the bar and build momentum? What are we learning about what it takes to make change in our organization?One key action we undertook with the help of some incredible leaders at Harmony, was to co-build an Artifact Study System to provide us with this source of feedback. We’ve broken down our analysis of this tool into two pieces: 1) the Artifact Collection System itself 2) lessons learned from studying artifacts leaders submitted.

Artifact Collection System

Before Harmony could study the reality of Lesson Preparation, they first needed an effective way to gain regular access to the preparation and execution of their leaders without visiting 60 campuses each month. The Artifact Collection Form is a digital form that allows instructional leaders to submit their meeting preparation, a video of the coaching meeting, and the final Lesson Preparation that they co-produced with their teacher. Here are three lessons we learned about the system itself:

Keep Artifact Collection Predictable: Instructional leaders at Harmony were regularly engaging in Lesson Preparation coaching meetings but remembering to film and submit them was a new practice. Harmony built a Scope & Sequence at the beginning of the year to keep submissions predictable and clear for leaders. One set of artifacts, due monthly, seemed to be a cadence that felt possible for leaders. How do we know? A sample month led to 734 submissions.Make The Process As Simple As Possible For The People Submitting: While the number of artifacts turned in monthly means the system was large and complex, Harmony succeeded by keeping the process as simple as possible for leaders submitting their work. When it was time to share evidence of their implementation, instructional leaders accessed a simple Google Form that asked leaders for their name, campus, and role, and then an upload button to help them connect the leader preparation, video, and teacher lesson prep from their Google Drive to the form. It looked like this:

Make It Accessible for Senior Leaders: While the form appeared simple for instructional leaders, each month the form collected as many as 800 artifacts into one large spreadsheet. We learned quickly that if the system creates more work than the value it creates. you have a problem! Stavroula Rojo, a system-leader on Harmony’s Performance Reporting team, added filters to make it easy for senior leaders to access what they needed: Assistant Superintendents could filter by region, Principals could filter by campus, Curriculum Directors could filter by content area, etc. All of this made it easy to find what one needed quickly to study artifacts. Additionally, Stavroula was able to create a data-tracking tool that supported accountability and follow-up across the district.

Study & Respond:

As the artifacts rolled in, Harmony shifted to the most important part of the process: How can we effectively study the evidence of implementation to accelerate progress? It was relatively easy to ensure organization-leaders had access to the evidence of Lesson Preparation execution, but figuring out how to best use the system to drive action was a learning process. Our work with Harmony helped distill two lessons we think are widely applicable:

Collaborative Study is Critical: When embarking on a new instructional practice (or a newly prioritized one), system-wide leaders can’t expect to drive change on their own. The goal of gathering data is to enable meaningful collaboration. With Harmony, we co-led bi-monthly “Study Meetings” with Assistant Area Superintendents (who were responsible for coaching principals). We utilized these meetings to collaboratively study 2-3 videos and artifacts from different regions that exemplified common and high-leverage challenges. Assistant Area Superintendents used these meetings to build shared understanding of effective implementation, further refine their shared vision for Lesson Preparation coaching and to practice developing specific praise and narrow action steps they could share with leaders to accelerate their practice. The collaboration was critical: often Assistant Area Superintendents left those meetings with shared tools (ex: Feedback Cheat Sheets, checklists for studying video) that allowed them to be more effective as coaches-of-coaches. Additionally, we were able to spot trends that informed the focus areas of upcoming leader development sessions so that sessions consistently felt responsive and relevant.Feedback Drives Buy-In: Perhaps most importantly, we witnessed how much leaders crave feedback when they submit evidence of their hard work. Campus leaders, just like system-leaders, were invested in Harmony’s goals and wanted to be as effective as possible. The more feedback they received, the hungrier they became to improve and show evidence of their growth. Of course, “winning” on individual feedback when there are 700+ artifacts is no easy feat. Harmony focused on a coaching-of-coaches model: Assistant Area Superintendents gave feedback to principals, principals gave feedback to instructional coaches, and all leaders were in role-specific Professional Learning Communities that leveraged peer-feedback (with feedback cheat sheets to support strong feedback) on a bi-monthly cadence.

The Artifact Collection System was central to our success. Following the launch of the Harmony project, we have replicated the use of an Artifact Collection System in other TLAC projects to give our team and our school partners a window into implementation and a source for uplifting bright spots. We’d encourage any school or school system launching a new initiative or a new curriculum to build and use a similar system.

The post Seeing Change: Harmony’s Artifact Study System appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

February 14, 2024

The Protocol Paradox: Scaling Effectiveness and Authenticity at Harmony Public Schools

This is the second of four posts on the challenges of achieving lasting change in instructional leadership at-scale via professional development. The series is based on our work with Harmony Public Schools in Texas. In this post Dan Cotton and Dillon Fisher address an important theme: that consistency is necessary to success at-scale and, perhaps unexpectedly, can also enhance authenticity.

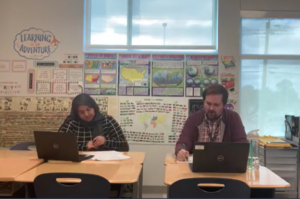

Harmony colleagues–teacher and coach–at work.

In our first post, we gave an overview of lessons learned from our 30 month partnership with Harmony Public Schools. A central element was building the coaching capacity and curriculum systems to execute Lesson Preparation across Harmony’s 60 campuses.

Scaling invites a challenge. In the drive to execute a clear, consistent vision for Lesson Preparation across many leaders, must an organization sacrifice authenticity and genuine relationships in coaching conversations? We think the lesson from Harmony–counterintuitively–is no. Consistency actually can enhance authenticity.

The Need for Consistency

Harmony serves 46,000+ students through a staff of over 5,000 employees. 300 of those are instructional leaders whose development we supported through our partnership. As Harmony began to build a culture of Lesson Preparation, the need for consistency became clear. Michael Dies, a District Instructional coach (and the creator of the guide featured below) described the challenge:

“Before the lesson prep coaching structure…each district coach would try to support teachers with lesson planning and preparation, but every coach had a different approach. With everyone approaching this coaching support differently, it was hard for coaches to collaborate on resource creation, it was hard for coaches to reflect and give one another actionable feedback, and it was hard to train teachers on how to best tackle this work on their own outside of a coaching meeting.”

As Michael illuminates, when all coaches were approaching lesson preparation uniquely, there was no practical way to learn from who was being most effective, to support each other efficiently, and to replicate success reliably.

When a school system decides to invest in instructional coaching–whether it’s Lesson Prep, observation and feedback, or student-work/data analysis– it must commit to providing clarity about what the intended outcome of a coaching session is, and how that looks and sounds during each step. The importance of clarity is particularly acute for large organizations who (through growth and/or turnover) face the need to replicate success with significant numbers of new leaders and teachers. When the vision is clear, coaching can be effective at-scale.

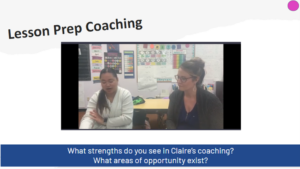

One of Harmony’s solutions to scaling consistency is its Lesson Prep Coaching Planning Guide (SY24). The coaching guide translates Harmony’s vision into replicable leader actions, enabling all leaders (particularly those new to the role) to have a meaningful impact on the quality of teachers’ lesson execution.

As the full guide and the annotated images above show, the strengths of this guide were multi-faceted: leaders had a clear understanding of the shared outcome of Lesson Preparation meetings, teachers and leaders experienced a consistent structure that valued teacher-time and, most importantly, the structure reliably led teachers to feel more confident and better prepared for their upcoming lessons.

The Protocol Paradox

One of our worries as we worked through iterations of the coaching guide alongside Harmony’s leaders was the possibility that systemizing Harmony’s approach to Lesson Preparation, especially through scripted leader prompts, might inhibit authentic coaching. Would consistent language leave teachers feeling that their development was on “auto-pilot?” Would these meetings unintentionally feel robotic and strip away a necessary authenticity to leader-teacher relationships? Would coaches be responsive to teacher ideas and the nuances of content? As we studied Lesson Preparation meetings alongside Harmony leaders, we found the opposite: Consistency actually enhanced authenticity. Two reasons we think that’s true:

Consistency Frees Up Working Memory: With the Lesson Preparation Guide in hand, leaders were able to focus more on the most effective process of Lesson Preparation and less on determining how to support their teachers or transition from one component to the next. Leaders and teachers knew what to expect and thus were able to spend their working memory digging more deeply into the lesson itself: What will excellence on the key task look and sound like? Why? Where might my individual students get stuck and how can I support them? How will students engage with the content individually and with their peers?Consistency Enables Better Listening: Similarly, without having to worry about what to say next or how to word it clearly, the Lesson Preparation Guide freed leaders’ working memory (as we know from the cognitive science research) to truly listen, and thus respond, to the ideas, questions, and challenges of the educator in front of them. In the countless videos we studied, we watched leaders and teachers spar on ideas about essay organization, laugh warmly through different attempts to resolve imagined misconceptions, and engage freely in practice that supported clarity for students.

Rather than degrading collaboration, systematizing lesson preparation with a clear protocol, including scripted prompts, actually accelerated it.

A consistent protocol benefited not just the individual teacher-coach conversations, but enhanced collaboration among leaders: Leaders could study video of colleagues executing the same protocol they use, peers and supervisors could give more targeted feedback that accelerated leader growth, and Harmony had greater clarity into how lesson preparation impacted teacher delivery of lessons.

Harmony continues to make responsive adjustments to its Lesson Prep protocol but the essential framework remains consistent. Such consistency–of common language, of approach, of expectations–advances leader development, teacher development and ultimately student engagement and success.

The post The Protocol Paradox: Scaling Effectiveness and Authenticity at Harmony Public Schools appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers