Doug Lemov's Blog, page 3

January 8, 2025

The Power of Laura Brettle’s “Active Observation” + Hope to See You in Miami

“Shea, you mentioned the word “equal”…

In a few weeks I’ll be in Miami with my colleague Hannah Solomon talking about techniques to Check for Understanding (There’s still room to join us: info and registration here).

One of the things we’ll talk about is the power of Active Observation–the idea that building systems to harvest data and observations about student thinking during independent work is one of a teacher’s most powerful tools.

Here’s a great example of what that looks like and one reason why it can be so powerful, courtesy of Laura Brettle, a Year 6 (5th grade) teacher at Manor Way Primary in Halesowen, England.

Laura starts by giving her students the task of describing the relationship between two fractions, which are equivalent.

They’ve got two minutes to answer in a “silent solo stop and jot.” Here Laura is cue-ing a familiar routine. Whenever students think in writing it’s called a stop and jot. Having a name for it reminds them that it’s a familiar routine and familiarity is important- when a procedure is familiar to the point of routine, students can complete the task with no additional load on working memory. All their thinking is on the math, rather than the logistics of what Laura has asked them to do.

But Laura has some great routines here too! As her students write she circulates and takes careful notes on her clipboard. She’s able to spot students who need a bit of prompting and to take note of students whose work is exemplary. Because she has notes on what many of her students think, she’ll be able to start the discussion intentionally.

“During the active observation,” my colleague Alonte Johnson-James noted when we watched the video with our team, “Laura monitors student thinking/writing in her first lap. As she launches into the second lap she begins to drop in feedback. First, to push a student to make their answer better and more precise. Additionally, she challenges students who might have finished early to push their thinking to identify additional equivalent fractions. She also recognizes where students struggle and uses intentional, appreciative Cold Calls of Shea and Joanna to explain how and why 5/6 and 10/12 are equivalent.”

And of course she does that in the most appreciative of ways.

First she asks students to track Shea: “Shea, you mentioned the word equal.” In doing so she’s let Shea know that the Cold Call is a result of her good work– she’s done well and this is her reward. And she also tells Shea what part of her answer she wants her to talk about. It’s a great way to honor students and make them feel seen for their hard work and to make Cold Call fell like an honor.

But you can see that Laura’s notes were really comprehensive. She also credits Finn for using the word double in his answer too.

Side note for one of my favorite moves–she magnifies the positive peer to peer symbol of the hand gestures students give to show they agree–“I can see people appreciating…” this helps Shea to see how much her peers approve of her good work!

Next Laura goes to Joanna. “What I liked about your answer is that you showed the calculation…. we know it’s double but what calculation did you use?”

Another super-positive Cold Call that makes a student feel honored for her work. And a very efficient discussion of the problem in which Jen has let students discuss the key points but avoided wasting any time.

We often refer to this as “hunting not fishing”: while students work, Laura “hunts” for useful answers and tracks them. When she calls on students she can be ultra-strategic and efficient, rather than calling on students and “fishing” for a good answer: that is, merely hoping that they’ll have something on-point to say.

Here simple but beautifully implemented systems for gathering data during independent work allow her to work efficiently and honor the best of student thinking.

If you’re as inspired by Laura’s work as we are (Thank you, Laura!!) please come join us in Miami to study this and other techniques for getting the most out of your classroom!

The post The Power of Laura Brettle’s “Active Observation” + Hope to See You in Miami appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 19, 2024

Student Achievement Through Staff Culture: An Interview with Max Wakeman

School leadership gold in this interview with Max

Over the past year we’ve been learning from 40 schools in Walsall and Sandwell England. These schools, located outside of Birmingham in areas of unusually high economic deprivation, were chosen to participate in a Priority Education Improvement Areas (PEIA) grant to increase self-regulation and meta-cognition (and therefore academic and social outcomes) in students.

Windsor Academy Trust, the visionary and organizer of the program, reached out to us to provide a training and support, and we’re thrilled to have been a part of it and thrilled to share that the initial results have been really encouraging.

Together with local education leaders, we’ve had the opportunity to visit all 40 schools, train leadership teams on Engaging Academics and Check for Understanding techniques, and study video of teachers implementing the techniques in their classrooms. From the video study alone, we’ve been lucky enough to cut 17 videos that we’ve been using in training, several of which you’ve read about on this blog here here and here for example.

In June, we started our second round of visits, to assess growth in meta-cognition and self-regulation, and we were delighted that of the 16 schools we visited, 13 of them were implementing techniques to positive effect. Obviously the real evidence will be in the form of assessment outcomes, which we are very optimistic about (there are lots of very promising leading indicators, including Goldsmith Primary School, part of Windsor Academy Trust being named an Apple Distinguished School, one of 400 schools chosen internationally) but in the meantime we’ll be writing more about what we’ve learned, and we couldn’t wait to share this interview with Max Wakeman, the Head Teacher at Goldsmith, where we taped two of the outstanding lessons we shared above.

In this interview, Max reflects on his school’s success in our work together, he talks about the importance of creating a strong Culture of Error for his teachers – and about showing love for students by holding them to the highest of expectations.

TLAC team-member Hannah Solomon had so much fun talking to Max here – we know you’ll enjoy learning from him as much as we did!

nbsp;

The post Student Achievement Through Staff Culture: An Interview with Max Wakeman appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 15, 2024

We Wire How We Fire: An Excerpt on Attention from Our Forthcoming Book on Reading

“Decentering the book.” Thanks but no thanks.

This week I’ve been posting excerpts from the forthcoming book on reading I’ve been writing with Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway–it’s tentatively going to be called The Teach Like a Champion Guide to the Science of Reading. Today I’m sharing the first few pages of our chapter on Attention, which is of the most important factors teachers of reading and English have to consider, especially now...

If you want to find out more, sooner, please join us for our Nashville workshop Dec 5 and 6.

Chapter 2: Attending to Attention

The universal adoption of smartphones and other digital devices has changed the life of every young person we teach.

The changes wrought have been at times promising and at times foreboding; sometimes both things at once. Sometimes, given the pace and complexity of the changes, it’s hard to even say what they mean and what their consequences will be.

And, of course, we experience a version of those changes alongside our students. As we write this, for example, we note that we are shortening our sentences. We are told that readers will be far less likely to persist in reading this if the sentences are too long and complex.

The decline of attentional skills associated with time spent in a digital world of constant distraction means that both we and our students find tasks that require sustained concentration—like making sense of a long-ish sentence—a little harder. And when it comes to harder things, we are a little less likely to persist than we once were.

Spare a thought for poor Charles Dickens. The mark of his craft was the intertwining of multiple ideas and perspectives within a single, complex sentence. The resulting sentences could be 30 or 40 words in length. With writing like that, he’d struggle to find readers in the 21st century. In fact, in most classrooms he does struggle—and for exactly that reason.

The fact that his books are long used to be a positive attribute. He was the 19th century’s most popular English-language writer, not so much despite his lengthy writing but because of it. Picking up David Copperfield (1024 pages) was, to a 19th century audience armed with the stamina to read without interruption for hours at a time, more or less like binge-watching a Netflix series today. You built your evenings around it.

Today long, like complex, is not a virtue. There is internet slang for this: tl;dr (too long; didn’t read), which the Cambridge dictionary glosses as: “used to comment on something that someone has written…: If a commenter responds to a post with ‘tl;dr,’ it expresses an expectation to be entertained without needing to pay attention or to think.”

Even in university settings, tl;dr is in the zeitgeist. “Students are intimidated by anything over 10 pages and seem to walk away from reading of as little as 20 pages with no real understanding,” one professorrecently wrote.

“Fewer and fewer are reading the materials I assign. On a good day, maybe 30 percent of any given class has done the reading,” wrote another.

Yet another professor notes “I’ve come to the conclusion that assigning students to read more than one five-page academic-journal article for a particular class session is, in sum, too much.”

In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari chats with a Harvard professor who struggles to get students “to read even quite short books” and so now offers them “podcasts and YouTube clips … instead.”

And in an Atlantic piece on “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” a first-year student at Columbia University told her required great-books course professor that his assignments of novels to be read over the course of a week or two were challenging because “at her public high school, she had never been required to read an entire book. She had been assigned excerpts, poetry, and news articles, but not a single book cover to cover.”

Reading, increasingly, is too hard, too long, too tedious to minds attuned to the arrival of novel stimulus every few seconds—or at least it is if we make no effort to rebuild attention. We’ll talk about some ways to do that in the classroom in this chapter, but consider for now one of the simplest ways to do this:,to give reading checks or quizzes at the start of each lesson: five to seven questions that are easy to answer if you’ve read carefully and hard to answer if you’ve read a summary or skimmed a bit here and there, and that will help train your students in what to pay attention to in a text.

Then again, we could ask: is this just moral panic? The judgment of every generation that the subsequent one is lacking? It’s an important question to ask, but the answer is: Probably not. There’s a lot of science to suggest measurable changes to attention.

Research tells us that your nearby cellphone, even turned off and face down on a table, distracts you. A 2023 study by Jeanette Skowronek and colleagues assessed how students performed on a test of “concentration and attention” under two conditions: when a phone was visible nearby but turned off, or when it had been left in another room. They found that “participants under the smartphone presence condition show significantly lower performance … compared to participants who complete the attention test in the absence of the smartphone.” In other words, “the mere presence of a smartphone results in lower cognitive performance.”

Similarly, University of Texas professor Adrian Ward and colleagues found that even unused, “smartphones can adversely affect… available working memory capacity and functional fluid intelligence.” Part of the reason for this is that it takes cognitive resources to inhibit the impulse to look at it as soon as you are aware of its presence.

You see a device and it triggers a desire to find out what’s become new in the past fraction of a minute. While it doesn’t even need to be turned on to have this effect, it usually is, of course. And turned on—almost always on and constantly attended to—means an attractive distraction from a difficult task pushed into your consciousness every few seconds. For those of us exposed to screens—including many of the teens we see in our classrooms—this has rewired not only the ways they think when their phones are in-hand but the ways they think, period.

While this surely demands greater reflection among schools, most relevant to this book are the particular implications those changes have for reading and reading teachers.

The Book is Dying

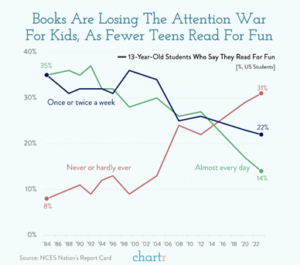

Consider the fact that far fewer students read for pleasure compared with just a few years ago. For time immemorial, we teachers have cajoled, encouraged and prodded students to read on their own. But even multiplying our efforts tenfold now won’t get us back to baseline reading rates of, say, 2005. The numbers of students who read outside of school and the amount of reading they do have fallen through the floor.

Take data gathered by San Diego State professor Jean Twenge. She has studied responses by about 50,000 nationally representative teens to a survey that has been administered since 1975, enabling broadscale changes over time to be easily observed and tracked.

In 2016, Twenge found that 16 percent of 12th grade students read a book, magazine or newspaper on their own regularly.

That’s about only half of the 35% of students who reported doing so as recently as 2005.

The survey also found that the percentage of 12th graders who reported reading no books on their own at all in the last year nearly tripled since 1976, reaching one out of three by 2016.

This is dispiriting in its own right, but doubly so because 2016 was a long time ago, technology-wise—the salad days practically, before the precipitous rise in social media use post-2020 and the advent of the most recent wave of especially addictive social media platforms like TikTok.

And, of course, any type or amount of reading shows up just the same in the survey, whether it’s 100 pages of Dickens or a short article on Taylor Swift’s latest outfit. In other words, even a “yes” on the survey still belies changes.

“This is not just a decline in reading on paper—it’s a decline in reading long-form text,” Twenge noted.

Other studies of young people’s reading behavior are consistent with Twenge’s findings.

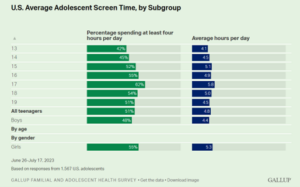

The 2023 American Time Use Survey found that teens aged 15 to 19 spent 8 minutes a day reading for personal interest. Compare that to the “up to 9 hours per day” the American teenager spends on screen time. Teens in that age group reported spending, on average, roughly 5 hours per day on screens in the 2023 Gallup Familial and Adolescent Health Survey.

Data from the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress show that the percentage of 13-year-old students who “never or hardly ever” read has increased four-fold since 1984, to 31 percent, while the percentage of students who read “almost every day” has dropped by 21 percent from that time, to 14 percent.

As recently as 2000, classrooms were comprised of three to four times as many daily readers as non-readers. Now these numbers are reversed. There are now typically less than half as many students who read regularly outside of class as there are students who never do so.

Let’s hope, then, that they are reading books cover to cover inside our classrooms, because they almost certainly are not outside it.

What does it mean for our actions in the classroom if students are increasingly likely to be attentionally challenged, yet sustained reading is among the most attentionally demanding activities in which we can engage?

What are the implications for text selection in a world where the only books many students read will be the ones we assign?

What are the implications for fluency and vocabulary that they are less and less likely to read beyond the classroom walls?

What does it mean to assign nightly reading when we cannot assume that students will go home and read, when doing so requires them to resist the pull of a bright and shiny device far more compelling in the short run and always within reach?

What does it mean that even those students who go home and pull out the book as assigned read in a different cognitive state than we might hope or imagine, again with a phone likely competing for their attention?

Consider: One of us—we won’t say which—has a teenager whom we require to read regularly. We wish this teenager chose to read every day, but he doesn’t, and we love him and know that whether he reads is too important to leave to chance—or the version of “chance” in which the cards are stacked against him actually reading by behemoths of technology spending billions of dollars to fragment and commercialize attention. So, we’ve mandated he read three hours a week.

He read when he was 12, by the way—voraciously. Sometimes now he remembers the feeling it gave him and he sets out with the intention of reading again. He knows it’s good for him. He knows he loved it then and might love it again. But then, on the way to his room or the couch or the patio with a book in one hand, he glances at the phone in his other. The snapchats are rolling in. The Instagram notifications. There’s a feed of tailored videos—his favorite comedian; his favorite point guard.

Suddenly 20 minutes have passed. Then 40. The book has lost again.

But let us share this picture of him on one of his reading days: reclined on the couch with a copy of The Boys in the Boat held aloft—briefly!—but also with his cellphone resting on his chest.

Every few seconds the reverie he might have experienced, the cognitive state he might have been immersed in where the book transported him to the world of Olympic athletes, is interrupted.

Perhaps for a moment he imagines himself in a scull on a lake at dawn as he…

Bzzzz. Dude! Sup?

Is interrupted by every manner of trivial and alluring distraction…

Bzzzzz. U coming over? We at B’s.

… which results on net in a different type of engagement with the book. There is no getting lost in…

Bzzzz. That new point guard. Peep this vid. Filth, bro!

…a different world or context. The level of empathetic connection to the protagonist…

Bzzzz. When U gonna text Kiley from math class. Think she digs you!

…is just not the same.

The experience of reading a book with fractured concentration is qualitatively different.

Bzzzz.

So there is both a “less reading” problem and a “shallow reading” problem. And, as we will see, reduced application of focused attention over time can become reduced ability to pay attention.

We have written about the broader effects of smartphones and the ubiquitous digital world elsewhere. So have others—often far more insightfully. Here, we will skip over here profoundly important issues of welfare and mental health: anxiety, depression and the inexorable dismantling of community and institutions of connection and belonging.

Instead, we will deal with what research can tell us about two specific consequences of technology that are critical to understanding the path forward for those of us who teach the five-thousand-year-old craft of reading: less reading and shallow reading.

We remind you that these forces affect practically every student and adult, regardless of whether they have a phone, and often regardless of their individual behavior in terms of their phone. Reading is a social behavior, something we do as we do in part, at least, because we learn it from others around us and see it reinforced by them. In this way, even students below the (steadily lowering) age-of-first-device are impacted. Are their older siblings shaping their behaviors by curling up with a book like they once might have? Are their parents?

Plus, while the phone is the primary tool technology companies use to fracture attention, the digital world is always encroaching. Think, for example, of when a five-year-old is handed an iPad in response to a bit of restiveness in the ten slow minutes before food arrives at a café, when they might otherwise have been handed a beloved book or been engaged in conversation with their family.

In the classroom—especially the reading classroom—these changes present us with a choice. We can, on the one hand, accede to them, accept that they are inevitable, and try to reduce the attentional and cognitive demands in the classroom in response. We can present text in shorter, simpler formats, and we can use more video and graphic formats too, as the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) has proposed, and as the Harvard professor Hari interviewed had done, replacing written texts as a source of learning and knowledge.

It’s certainly easier in many ways to choose this approach. We could tell ourselves to do the best we can with the students we get–it’s not our responsibility to try to change them. It would be reasonable simply to decide to adapt ourselves to a brave new world.

We are not yet ready to concede, however. There is too much at stake, we think, in accepting a reduction for our young people—and soon enough adults—in the ability to sustain focus and attention in text. We think the idea that only specialists might be able to read, say, Dickens, or the founding documents of our governments, or the journal articles that herald scientific discovery, to be problematic, to say the least. We don’t think that an impulsive body politic that requires instant gratification or is not adept at sustaining attention is a good thing.

We agree with the New York Times columnist Ross Douthat when he wrote that “the humanities need to be proudly reactionary in some way, to push consciously against the digital order in some fashion, to self-consciously separate and make a virtue of the separation.” English or literature classrooms are best positioned to build the conscious alternative to digital society precisely because of the great books that we think ought to form the bulk of our classroom reading material. We’ve spent several hundred years stocking the war chest, so to speak, with great things to read—books that, once engaged, give students the experience of saying “yes” to something other than the digital world. If we give up on books, we give up on the best antidote we may have to the allure of the digital.

Along those lines, we also don’t want to concede because books are a medium that hold a unique key to strengthening attentional skills—one of the gifts that schooling should give to young people. Reading—deeply and with focus—offers not only a privileged form of access to knowledge but a profound form of enjoyment that is unique and, in many ways, more nourishing than more instantly accessed forms of gratification.

What attracts us in the short run—the constant roll of new information and novel stimulation—is not actually what gives us pleasure in the long run. Far more people—yes, even teens—look back at an evening of scrolling or idle watching with more regret than pleasure. You are drawn to it in the moment but waylaid by your own attention: you later wish you’d gone to the gym, practiced the guitar, read a book. You wish you’d accomplished something, true, but also that you had been doing something that felt meaningful afterwards.

In fact, one of the most pleasurable states a human can experience is something called the “flow” state, extensively studied by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Flow state is the mindset you enter into when you lose yourself in a task that interests you. You become less self-conscious, less aware of almost everything else, even the passage of time. It is essentially a state of deep and unbroken attention.

Perhaps you have felt this playing a sport you love or, as Csikszentmihalyi first studied, while engaging in a form of creative expression like playing a musical instrument or drawing.

Flow is gratifying even if it requires effort—perhaps because it requires it. “The more flow you experience the better you feel” notes Hari. And, he adds, “one of the simplest and most common forms of flow that people experience in their lives is reading a book.”

If phones have ruptured our students’ attention spans by rewarding them with brief flashes of shallow pleasure, books can provide an antidote: helping our students retrain their attention spans, with the reward of deeper, longer-lasting pleasure.

The trick, of course, is getting students to pick up and engage with a book for long enough to actually experience this.

This chapter, then, provides a road map for those of us who choose not to give in to reduced attention but to seek to create in our classrooms an environment where we enrich reading. We begin by presenting a key principle that can guide us in how to improve attention and other capacities that are critical to developing young people who regularly engage in sustained and meaningful thought; then we share three ways to enact that principle in the classroom.

We Wire How We Fire

Because our brains wire how we fire, how we read consistently affects our neurological capacity for future reading. This means we can shape students’ reading experiences in classrooms, taking advantage of the social nature of reading, to develop our students into more attentive and deeper readers—and ones who enjoy it more. .

We begin with the most important phrase in this chapter: We wire how we fire.

The brain is plastic. As we noted in chapter 1, the act of reading is a rewiring of portions of the cortex originally intended for other functions. We are already re-wiring when we read, and how we read shapes how that wiring happens, how we can, and probably will, read.

If we read in a state of constant half-attention, indulging and anticipating distractions, and therefore always standing slightly outside the world a text offers us, our brains learn that is what reading is—they wire for a liminal, fractured state in which we only partially think about the protagonist and his dilemma or the meaning embedded in the Founding Fathers’ chosen syntax.

But thankfully that key phrase, we wire how we fire, cuts both ways. If we build a habit in which reading is done with focus and concentration and even, to go a step further, with empathy and connectedness, and if we do that regularly for a sustained period of time, our brains will get better at reading that way—more familiar with and attuned to such attentional states. We are likely to do less searching for distraction and novel stimulus as we read. We’re also less likely to drift on the surface of a text, but instead to read deeply and to comprehend more fully. And because we are understanding better and are less distracted, we are more likely to persist.

In other words, we can re-build attention and empathy in part by causing students to engage in stretches of sustained and fully engaged reading. One thing this implies is more actual reading in the classroom with more attention paid by teachers to HOW that reading unfolds. Attending to how we read—thinking of the reading we do in the classroom as “wiring”—gives us an opportunity to shape the reading experience intentionally for students. Those who read better, richer, more gratifyingly, more meaningfully, more socially, will read more and get more out of what they read.

A colleague of ours advised—a few years ago and with the best of intentions—that there should be very little actual reading in English classrooms. “The reading happens at home and the classroom is about discussion,” he opined. We love discussion and see plenty of room for it in the classroom, but we think text-centered reading classrooms are strong ones. Our argument then is more urgent now. We are for making the text itself and the act of reading central to the daily life of classroom. Even if we weren’t at a time when it’s clear that without classroom reading, very little reading is done at all, we would still advocate for this practice. We think the science supports us.

Reading with students in the classroom allows us to shape the experience cognitively and socially. We can ensure blocks of sustained focus and that students connect with each other through the shared experience of the story.

In fact they were serialized- meaning that they were—like a Netflix series—released in installments that occasionally dragged out the plot and caused readers to yearn for the next part to arrive.

Theologian Adam Kotsko. https://slate.com/human-interest/2024/02/literacy-crisis-reading-comprehension-college.html

[https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-36256-4.

The presence of smartphones—even unused–may “impair cognitive performance by affecting the allocation of attentional resources, even when consumers successfully resist the urge to multitask, mind-wander, or otherwise (consciously) attend to their phones—that is, when their phones are merely present. Despite the frequency with which individuals use their smartphones, we note that these devices are quite often present but not in use—and that the attractiveness of these high-priority stimuli should predict not just their ability to capture the orientation of attention, but also the cognitive costs associated with inhibiting this automatic attention response.” https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/691462

Another attribute of Twenge’s survey instrument is that she and colleagues ask students about behaviors and attitudes across a wide spectrum of topics so questions about reading are embedded among questions about a dozen other topics. Most studies of reading behaviors rely on self-report—necessarily—and so if students, who mostly know they ‘should read more’ know they are primarily being surveyed about their reading behaviors, specifically, they’re perhaps more likely to round up a bit—they know they really should be doing more of it.

“almost everyday”… see iGen https://www.amazon.com/iGen-Super-Connected-Rebellious-Happy-Adulthood/dp/1501151983

See Doug and his co-author’s discussion in Reconnect of the near doubling of screen time among teenagers during and post-pandemic.

https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx If you’re wondering, the data on reading for adults over 15 was 15.6 minutes a day (in 2018). That number was down 28% in just 15 years. It was almost 22 minutes per day in 2003.

https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ltt/reading/student-experiences/?age=13

Someone somewhere is wondering about their child’s capacity to sustain a state of obsessive attention while playing video games. Isn’t this driving him (he is statistically highly likely to be male) to build his attentional capacity? It is not—at least not to low-stimulus events. He is learning to lose himself in a world that constantly offers maximum immediate stimulation and gratification. If you wish for him to sustain attention while reading a medical chart, a novel of historical importance or the Constitution of the United States, you will be disappointed.

Shamefully, we think, they have come out in favor of “decentering the text”: “The time has come to decenter book reading and essay writing as the pinnacles of English language arts education,” they wrote in a recent position statement. “It behooves our profession, as stewards of the communication arts, to confront and challenge the tacit and implicit ways in which print media is valorized.” By contrast, we think it’s actually the job of teachers to valorize reading and writing.

Stolen Focus 57

Adaptation of the phrase “neurons that fire together wire together” coined by the Neuropsychologist Donald Hebb in 1949

The post We Wire How We Fire: An Excerpt on Attention from Our Forthcoming Book on Reading appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 13, 2024

The Science of Reading: It’s About Knowledge not “Transferable Skills”

Casaubon: Well meaning but hopelessly wrong…

Recently, I shared an overview of the topics in the forthcoming book on reading I’m writing with Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway: seven key principles of reading instruction that should inform what we do in k-12 classrooms. (Note we’ll be discussing these principles at our Nashville workshop Dec. 5 & 6)

Today, I’m going to share a bit more about the another of those principles, the idea that once students are fluent, background knowledge is the most important driver of understanding and comprehension. A common misunderstanding about reading comprehension is that it involves transferable skills like making inferences that once learned can be applied to other texts. Unfortunately there is little evidence that the skill translates and significant evidence that the skills happen naturally when readers have sufficient background knowledge to disambiguate texts.

One of the themes of Middlemarch, George Elliott’s classic 19th century novel, is Mr. Casaubon’s fruitless pursuit of a concept he refers to as “the key to all mythologies.” A scholar, he imagines a single understanding that will illuminate the true meaning of every tale. He spends his life toiling at the task of finding this universal key.

It’s hopeless of course. The novel reveals his delusions. When he dies, his admiring wife, Dorothea, at last reads his papers and can see that the project was absurd from the start, but the reality proved all but impossible to acknowledge because the dream was so beautiful. It was a ‘chimera,’ something so alluring the believer desperately wants it to exist even when the facts are telling him it cannot be so.

The belief in transferable skills is perhaps the most common chimera among teachers of reading. Imagine a handful of universal tools we could teach students and in so doing allow them to understand every text they read. Who wouldn’t seek out “the key to all inferences,” for example, knowing that once mastered this skill would allow them to unlock what was unspoken in every story? Or the “key to main ideas’ which would allow our students after a bit of diligent study to grasp the gist of any passage we put in front of them for the rest of their lives. Who among us would not dream such a beautiful dream?

The problem of course is that for all the beauty of the dream, the evidence is squarely against it. While we make inferences constantly while reading, and while doing so clearly assists with comprehension, practicing strategies like making inferences doesn’t help much and there’s no evidence that the ability to make inferences well transfers from one book to another. The opposite in fact.

“People don’t decide that they’re going to make these inferences, the mind just makes them happen,” Daniel Willingham writes. This is perhaps one reason why “practice brings no benefit to reading-comprehension strategy use.” Summarizing the finding of recent studies, he writes beyond a very small amount of introduction to the idea: “There was no evidence that increasing instructional time for comprehension strategies—even by 400 percent!—brought any benefit.”

The reason for this is that our ability to inference is a function of our prior knowledge.

Here’s an example from a third-grade classroom we recently visited. The class was reading Charlotte’s Web when they came across this scene:

“But Charlotte,” said Wilbur, “I’m not terrific.”

“That doesn’t make a particle of difference,” replied Charlotte. “Not a particle. People believe almost anything they see in print. Does anybody know how to spell terrific?”

“I think,” said the gander, “It’s tee double ee double rr double rr double eye double see see see see see.”

“What kind of acrobat do you think I am?” said Charlotte in disgust.

The teacher paused and asked why Charlotte was disgusted. Two students responded. The first said because the gander always talked too much. The second because the gander always said everything three times. Both of which are true and both of which are wrong if the goal is to explain why Charlotte was disgusted.

Perhaps students didn’t understand how to infer a character’s point of view from her words. This would be the assumption in a lot of classrooms and the result would be a lesson (or a series of lessons) on the “skill” of inferencing.

But the source of the problem was revealed when the teacher asked: Who knows what an acrobat is?

There was a smattering of two or three hesitant hands. A boy who’d raised his responded: “It’s a little bit like a magician, I think.”

Charlotte, for those who haven’t read Charlotte’s Web, is disgusted because she intends to write the word in a spider web and the gander’s very long spelling of the word implies lots of work hanging precariously from a web for her. But if you don’t know what an acrobat is, you cannot know that. The problem was not a skill problem. Knowledge cues an inference and without it, no further explanation of how to make an inference or what an inference is will help much.

That the knowledge enables the inference is an inconvenient fact. It means we can’t just explain and practice and have students get better at inferencing. There is no Casaubon-like short cut. We instead have to go the long way around and make sure students have the background knowledge they need to make better sense of what they read.

As Dylan Wiliam writes in Creating the Schools Our Children Need, “The big mistake we have made in the United States is to assume that if we want students to be able to think, then our curriculum should give our students lots of practice thinking. This is a mistake because what our students need is more to think with.”

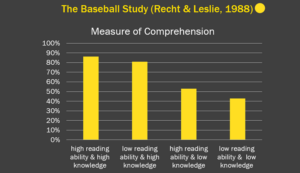

A classic study by Recht and Leslie and known as The Baseball Study demonstrates this.

The authors divided 64 7th and 8th grade students into two groups based on their reading levels: weak readers and strong readers. But they also divided those groups again, based on whether the students knew a lot about baseball. Now they had four groups. Good readers who knew a lot about baseball; good readers who knew very little about baseball; weak readers who knew a lot about baseball; and weak readers who knew very little about baseball.

They gave them a passage to read. Here are the first few lines:

Churniak swings and hits a slow bouncing ball toward the shortstop. Haley comes in, fields it, and throws to first, but too late. Churniak is on first with a single…

After students read the passage, the researchers tested the four groups of students to see how much of the passage they understood. Some of the results were exactly what you’d expect:

The students with high reading ability and strong knowledge of baseball had no trouble with the passage. They got almost all of the answers correct. By contrast the weak readers with weak knowledge of baseball really struggled. They got less than half the questions right, scoring little above the level you’d expect them to get if they were merely guessing.

The surprise was in the two middle groups. The students with low reading ability but strong knowledge of baseball did better than the high ability readers with little knowledge of baseball. Quite a lot better in fact- they were a few points behind the top group and scored almost 30% better than the students who were “better” readers but knew less about the topic of the passage.

It’s a study that has been repeated many times with students reading about different topics, and it demonstrates quite elegantly that you read well and successfully when and because you have background knowledge of what you are reading about. To return to Dylan Wiliam’s point: if we want students to understand and think more deeply about what they read we should focus on knowledge and not waste time trying to teach them abstract skills like making inferences or finding the main idea.

The reason why this is the case has to do with what you might call the inherent ambiguity of every text. As Daniel Willingham recently pointed out, every sentence is to some degree ambiguous. An author never tells you everything. If he or she did, reading would be incredibly tedious and meaning making would become nearly impossible.

Here’s an example. We’ve rewritten the previous sentence to eliminate ambiguity and ensure your accurate comprehension of our exact point regardless of background knowledge:

An author of a book, article, poem, treatise or other example of a written text in English or any other language never tells you—in this case the reader but also people like the reader who might also be reading or be imagined to be reading said text—everything that he or she intends to communicate in that text because if he or she did reading would become incredibly tedious due to the overwhelming loads of marginally relevant information jammed into the sentence in order to clarify every possible misunderstanding or gap in perception and in the end every text would read like a dense contract between two massive corporate entities seeking to eliminate any possible gray area to their transaction.

Authors by necessity always make assumptions about what readers know and assume they will fill in gaps. This is always true, even when they aren’t deliberately leaving blanks and ambiguities for stylistic or artistic reasons. Understanding any text always involves “disambiguating” it.

Here’s a very short text, the ambiguities of which make an interesting case study:

The wooden box was massive. She placed her bear on the ground. It was going to be hard to carry.

The ambiguities are probably not even apparent to you at first because you resolved them simply and easily with inferences you didn’t know you made. One ambiguity is that her “bear” is not a real bear but a teddy bear. There’s no way she’d be carrying a real bear. As a result you probably inferred that “she” was a child. Another ambiguity involves resolving what noun the pronoun “it” refers in the second sentence. Grammatically it’s just as plausible for it to refer to the teddy bear as the box. But you knew that it referred to the box. It doesn’t make sense for a teddy bear to be hard to carry but a wooden box, yes. Especially for a child. You disambiguated because you had knowledge–the weights of common things; that someone with a teddy bear is probably a child–the author assumed you would have.

But what if the author assumes you know something you don’t. Like in this sentence:

For pudding she allowed herself some cake.

If you’re a reader in England, where “pudding” means roughly the same thing as “dessert” does to an American, the sentence is easily disambiguated. She ordered cake after dinner. It was a small indulgence. This is implied by the phrase “she allowed herself.”

But if you lack that background knowledge, the sentence is nonsensical, even if you are a very good reader.

Your working memory is busy wrestling with what seems like a riddle—for pudding she had cake? How could she have cake for pudding? Does the author mean “instead of pudding” maybe? (If you are English imagine the sentence “For custard she had cake” to get the general sense for how an American might experience the text). You not only failed to understand the first part, you might not have even noticed or perceived the subtle implications of the word allowed which tells you quite a bit about the “she” in the sentence and the small indulgence which perhaps she wouldn’t ordinarily consider, of permitting herself a piece of cake: perhaps she is conscious of her weight. Perhaps she is conscious of money. When your working memory is overloaded wrestling with something you don’t immediately understand, your perceptiveness of other details is also degraded. Meaning is interrupted everywhere. There is no ‘story’ in the sentence for readers who don’t have background knowledge about what “pudding.”

Comprehension, this is to say, is knowledge-based. We make better inferences, we perceive more, we have working memory to think more deeply, when we know more about what the author assumes we know enough about. We can’t do those things when we don’t.

In a 2020 review of the literature, Reid and collegues “consistently found that higher levels of background knowledge enable children to better comprehend a text. Readers who have a strong knowledge of a particular topic, both in terms of quantity and quality of knowledge, are more able to comprehend a text than a similarly cohesive text for which they lack background knowledge. This was evident for both skilled and low skilled readers.”

“Controlling for other factors, knowledge plays the largest role in comprehension. The more a reader knows about a topic, the more likely they are to successfully comprehend a text about it,” Literacy specialist Jennifer Walker of Youngstown State writes, again summarizing the broader literature on the topic.

In fact, the connection between knowledge and all types of high-order thinking is clear if often overlooked. “Data from the last 30 years lead to a conclusion that is not scientifically challengeable: thinking well requires knowing facts…The very processes that teachers care about most—critical thinking processes like reasoning and problem solving [and reading!]—are intimately intertwined with factual knowledge that is in long-term memory,” Daniel Willingham writes. “Most people believe that thinking processes are akin to those of a calculator. A calculator has a set of procedures available (addition, multiplication, and so on) …. If you learn a new thinking operation (for example, [how to make inferences]), it seems like that operation should be applicable to all [settings]. The human mind does not work that way. The critical thinking processes are tied to the background knowledge.”

Somehow this fact does not seem to be getting through to schools. Perhaps it’s the chimerical nature of skills-based instruction. We just can’t let go of how beautiful it would be if we could just give students a super-skill, a universal key and the hours we spend chasing that dream is time taken from far more productive tasks.

Again, we don’t blame teachers for this. Even at the highest levels of policy, even in schools of education, the misconception prevails.

In his book Why Knowledge Matters E.D. Hirsch tells the story of France, which had among the best and most equitable school systems in Europe before the French replaced their knowledge-rich curriculum with a skills-intensive approach. Results declined steeply overall and gaps between rich and poor students expanded. Scotland followed suit a few years later. It “downgraded the status of knowledge and adopted a competence-based approach, emphasizing the development of transferable skills and interdisciplinary learning,” Sonia Sodha wrote in the Guardian. The results? Scottish students lost an average of about 6 months progress in reading on the 2022 PISA while inequality increased. The lowest-status group fell twice as fast (a drop of 20 points) as in the highest-status group,” Lyndsay Paterson, a professor of education at the University of Edinburgh observed.

You can find a thousand voices on the internet telling us to choose less knowledge and more skills, but even asking what the right balance is between skills and knowledge is the wrong question, Daisy Christodoulou has observed. It is like asking what the right balance is between ingredients and cake.he ingredients become the cake; the knowledge becomes the skill. If you want deeper thinking, if you want better reading, start by building students’ knowledge. You can do quite a bit of that if you don’t spend hours explaining what an inference is.

https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/beyo...

Increasing over a bare minimum of a few minutes, this is to say. In other words everything you need to know about what an inference is can be taught in less than a single lesson. Beyond that you are wasting your time.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1988-24805-001. Also described here: https://www.coreknowledge.org/blog/ba...

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02702711.2021.1888348

https://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Literacy/Literacy-Academy/2023-Literacy-Academy/Language-Comprehension-Components-Necessary-for-Reading-Comprehension.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US. Walker refers to Cromley & Azevedo, 2007; Ozuru, Dempsey & McNamara, 2009 among other studies.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentis...

https://reformscotland.com/2023/12/pi...

The post The Science of Reading: It’s About Knowledge not “Transferable Skills” appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 12, 2024

On Fluency: The Hidden Barrier to Comprehension

Most fluent readers cannot look at this sign & NOT read it. They process the words faster than they can decide not to attend to them.

Yesterday I shared an overview of the topics in the forthcoming book on reading I’m writing with Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway: seven key principles of reading instruction that should inform what we do in k-12 classrooms. (Note we’ll be discussing these principles at our Nashville workshop Dec. 5 & 6)

Today, I’m going to share a bit more about the first of those principles, the idea that fluency is an chronic and overlooked barrier to reading success at all grade levels.

Summary: Fluency is the ability to read words quickly and easily as soon as they are encountered. The quickly and easily are important because they imply the lack of reliance on working memory. If the reading itself requires conscious thought, the process will crowd out other more advanced cognitive activities that are required to make meaning of text.

The simplest definition of reading fluency is ‘the ability to read at the speed of sight.’ We take this definition from Mark Seidenberg’s book of that title. It refers to the ability to absorb the meaning of written text as soon as you look at it- to decode not only individual sounds but words and phrases as soon as you perceive them.

Fluent readers rarely have to hesitate to think about what the words they are reading say or how they link together. Of course there are times–with an especially complex text or when your attention has drifted–when even fluent readers may have to re-read a passage to make sense of it, but for the most part meaning accrues as words are glimpsed. There is no discernible delay and little conscious effort.

When you can read effortlessly, without having to think about it, your working memory, that critical part of your brain for creating memories and understanding, is free to do other things like think about the meaning of the text or perceive details within it. When the first parts of reading are automatic, conscious thought and attention are freed up and can be used elsewhere. For this reason, fluency is a prerequisite to comprehension. If you cannot read at the speed of sight, your ability to understand, think about and remember what you have read will be limited.

In fact in most cases a fluent reader can’t not read a piece of text in their native language. You see a road sign and have processed that it says “No Parking” as soon as you’ve perceived the words. The reading happens so quickly, effortlessly and automatically that you do not have time to decide not to read it. Making a conscious decision takes about half a second and by then you would have read the words. Only if you were highly distracted could you look at the sign and NOT read it.

If you are a fan of Duolingo say or have experience trying to learn a foreign language, particularly as an adult, you have probably experienced the sort of effortful reading that is common for dysfluent readers. You read and must pause to consciously remember words and decipher phrases. You can often figure them out within a few seconds, but only through conscious effort and by the time you’ve done that you then have to circle back and read the sentence again, possibly several times, to figure out what it means. When listening or reading, you can keep up for a sentence or two but your working memory is soon overloaded and you lose the ability to sustain meaning-making. It’s a lot of cognitive work and you tire quickly. As long as you have to extend effort to decipher the words, you are not yet able to read in the fullest sense of the word.

In fact, fluency requires three distinct things at once.

First, it requires accuracy. You must reliably read the sounds and the words correctly. While decoding is the name of this process for speech sounds, orthographic mapping is the name for the process by which each unique sequence of letters becomes “glued” in your mind as a word. You see it and recognize the word nearly simultaneously and no longer need to fully decode it.

But fluency also requires automaticity, which is accuracy at speed. Reading rate is an important precursor to reading comprehension. Faster isn’t always better but a certain level of rapidity is almost always required. Many researchers posit 110 words per minute as a baseline rate. For example, in a 20xx study, 91% of students who had oral reading fluency scores at or above 110 words per minute also scored proficient (level 3 or above) on the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test. Students who did not score 80 words per minute correct were almost assured to do poorly on the FCAT. Students who cannot read accurately and quickly are at high levels of risk for reading failure.

Finally, fluency requires prosody, which is “appropriate expression or intonation coupled with phrasing that allows for maintenance of meaning” (Kuhn, Schwanenflugel, & Meisinger, 2010). Prosody enables us to invest the words we are reading with meaningful expression so they sound like they might if they were spoken aloud. Prosody allows us to emphasize a certain word in a sentence or to link the words in a phrase together. It is meaning made audible.

Accuracy plus automaticity plus prosody is the fluency formula, and multiple studies have demonstrated its deep connection to comprehension as well as the fact that far fewer students have mastered it than you might expect.

Generally, most studies find that about half of demonstrated reading comprehension is predicted by reading fluency. David Paige and his colleagues at the Northern Illinois University found, in a study of sixth- and seventh-grade students, that oral reading fluency explained between 50% and 62% of differences in reading comprehension (Paige 2011a). Sabatini, Wang and O’Reilly (2019) studied the connection between fluency and overall scores on the 2002 NAEP reading assessment and found that “the strongest predictor of NAEP comprehension scores was reading rate.” Bloomquist (2017) found that 45% of the variation in reading comprehension levels among 4th and 5th grade students in Colorado was attributable to oral reading fluency. It’s likely that the predictiveness of fluency declines slightly as students age but Schatschnieder and colleagues found that reading fluency accounted for about a third (32%) of reading comprehension scores among 10th graders. Even that late in a student’s career, the connection remains strong.

“Slow, capacity draining word recognition processes require cognitive resources that should be allocated to comprehension. Thus reading for meaning is hindered,” Keith Stanovich and Anne Cunningham summarized in their 1998 analysis What Reading Does For the Mind, but they also outlined a secondary effect of dysfluency: “Unrewarding reading experiences multiply.” Struggling to understand and reading without learning much make reading appear to have less value. Place this alongside the greater cost in terms of effort required for dysfluent readers and the value calculus tips away from reading. “Practice is avoided or merely tolerated,” it is done “without real cognitive involvement.” Dysfluent readers stop wanting to read or experience reading as not being especially meaningful and so the gaps between them and their classmates widen.

Though research into the scale of dysfluency is limited, studies suggest that it is a wide-scale problem. Analyzing the data from Sabatini’s study of more than 1700 4th graders, for example, Paige notes that “41.7% of 4th grade students—almost half—appear to have reading fluency issues,” and that such issues are “strongly associated with poor performance on the NAEP.” A 1995 report by the National Center for Education Statistics found similarly that just “55 percent of fourth graders were considered to be fluent,” and that after reading a passage twice silently, only about 13 percent of the fourth-graders in a NAEP study “could read with expressive interpretation and consistent preservation of the author’s syntax.”

Moreover, fluency remains a pervasive issue among older students. Paige found gaps in fluency and a strong correlation to comprehension among sixth and seventh grade students, well beyond the years where most schools remain attentive to fluency and in Schatschneider’s study of Florida students, more than half of tested 10th graders demonstrated fluency rates below proficient.

And the effects are of course not limited to testing. A study of Italian students, found that “Reading fluency predicted all school marks in all literacy-based subjects [we’d argue that all subjects are literacy-based!], with reading rapidity being the most important predictor.” The authors added, “School level did not moderate the relationship between reading fluency and school outcomes, confirming the importance of effortless and automatized reading even in higher school levels.”

Two findings jump out from that statement- first the simple importance of rapid reading specifically and second that fluency matters at all grade levels- though it is least likely to be assessed and therefore recognized among older students. (The students in this study were in grades 4-9).

Despite this data, “fluency has been relatively neglected beyond the elementary grades,” Paige observes. There is, he writes, “little instruction occurring…to improve reading fluency” beyond the mid elementary years and by middle and high school, teachers are more likely to “employ work-arounds so students don’t have to read text” during class.

Research suggests that fluency poses a hindrance to comprehension for close to half of students even into high school in other words. “At the end of the day, my hunch is that 40% to 50% of middle school students do not have proper reading fluency,” Paige told us. “In schools where students generally struggle with academic attainment, this percent is likely closer to 80%.”

Given that the texts students are expected to read become more complex and therefore demanding from a fluency standpoint, there is little reason to suspect there are not large numbers of students in high school and even college for whom reading fluency is a massive and hidden barrier to reading comprehension. And when that is the case, were are less and less likely to know about it. When was the last time the average 9th grader’s oral reading fluency was assessed?

A colleague of ours observed that not only did she as a teacher rarely ask older students to read aloud and so know little about their fluency, but that she did the same with her own children. “I never ask them to read aloud anymore,” she said of her middle school-aged children. “I suddenly realized that it has been years since I had even an intuitive sense for their fluency.”

She’s right to be worried, especially given that almost all of the existing research data was conducted before the precipitous rise of the smart phone and social media which have dramatically reduced independent reading outside of school among American teenagers to a fraction of what it once was (see page #). The problem is almost assuredly worse now.

Hecotr Ruiz Martin notes, in How Do We Learn, the physical act of “reading is procedural knowledge , and as such, it is impossible to avoid doing it when we see words (if we are expert readers).

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-3...

https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/vi...

53% was attributable to the the different but less-frequently assessed skill of silent reading fluency

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED...

Interview with David Paige by the authors 12.11.23

https://nces.ed.gov/pubs95/web/95762.asp

We note here that English is more orthographically complex than Italian. This is to say it’s less predictable and consistent in spellings and sounds. It’s harder to read fluently and so we might conjecture that Bigozzi’s findings would be even more stronger manifested among subjects reading in English.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28261...

Interview with the authors, 12.11.23

The post On Fluency: The Hidden Barrier to Comprehension appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

November 11, 2024

What the Science of Reading Says “Post-Phonics” & Meeting Up in Nashville

Bringing the Book Back to Life

It’s exciting times at TLAC Towers in terms of reading.

Colleen Driggs, Erica Woolway and I are finishing the manuscript of a new book about translating the science of reading into classrooms. We’re really excited about it and will be sharing some of our new insights at our Reading Reconsidered workshop in Nashville December 5 and 6. In the meantime I’ll be sharing some excerpts from the draft manuscript here.

The book describes seven key arguments that we think tell us what should happen in reading classrooms “post phonics,” and we can probably best capture what we mean by that phrase with a diagram.

The green portion of the diagram below represents time spent teaching systematic synthetic phonics in the early grades. It is job one. It cannot be over-looked. The science behind its importance, as you hopefully know, has been ignored for too long and reflects a culture in schools that is not as responsive to the science as it should be.

But… systematic synthetic phonics shouldn’t be the only thing students do in the primary grades even if it’s the most important. How else should they spend their time.

And even more importantly, there’s the question of what should happen after the primary grades, assuming students have mastered decoding.

In that area we think there is a massive amount of science that tells us pretty clearly what we should do. And it’s not what generally happens in reading and English classes. So the book tells the story of the blue areas on the chart: what the research in each of seven key areas says and how we should apply it.

So for starters here are our seven key Research-Backed Arguments About ‘Post Phonics’ Reading

1) Fluency is a prerequisite to reading comprehension at all grade levels.

Fluency is the ability to read words quickly and easily as soon as they are encountered. The quickly and easily are important because they imply the lack of reliance on working memory. If the reading itself requires conscious thought, the process will crowd out other more advanced cognitive activities that are required to make meaning of text. The number of dysfluent students in your classroom is almost assuredly far higher than you think!

2) Once students are fluent, background knowledge is the most important driver of understanding and comprehension.

A common misunderstanding about reading comprehension is that it involves transferable skills like making inferences that once learned can be applied to other texts. Unfortunately there is little evidence that the skill translates and significant evidence that the skills happen naturally when readers have sufficient background knowledge to disambiguate texts.

3) Vocabulary is the single most important form of knowledge (but is often taught as if it were a skill)

Knowledge of words—both deep and broad—is a particular and particularly important form of background knowledge but it is often taught in ways that do not reflect how it is acquired and used.

4) Attention is central to every learning activity especially reading, and building attention is a necessary step in effective reading instruction

Attention is the currency of learning-in almost any task. But reading, especially, relies on and requires states of sustained focus and concentration. If the smartphone has taught us one thing it’s that people’s attention is malleable. But this also means we can intentionally build student’s capacity to attend to what they read.

5) Intentional writing development can play a critical and synergistic role in developing better readers

Done carefully, writing in response to reading can both assist in memory formation and also help students develop mastery of the same code that reading relies on. Short exercises that can be easily and quickly revised and that intentionally develop students’ control of syntactic forms are especially useful.

6) The ability to read complex text is the gate keeper to long term success

Exclusively giving students texts to read that are easily accessible to them can seem easy and engaging in the moment but in the long run students must earn to read challenging text and become comfortable with the struggle implicit in texts they will read in their schooling and careers.

7) Books are the optimal text format through which to build understanding and comprehension

Books package information and ideas in a unique form to which our brains are especially receptive from a learning stand point and that creates arguments of depth and nuance in a ways that is critically important in a digital society. Moreover books create the best opportunity to create for students the sort of shared social experience that is critical to their sense of belonging in schools.

Over the next few days and weeks I’ll be sharing more detail on these seven arguments so check back to read some key pieces of the argument. Or join us in Nashville to study classroom videos and practice teaching tools with us. If that’s of interest, here’s the link:

The post What the Science of Reading Says “Post-Phonics” & Meeting Up in Nashville appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 25, 2024

Seven Details from Matthew Tipton’s use of Everybody Writes

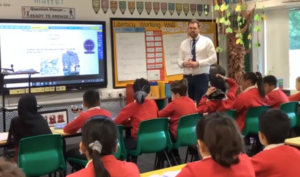

Matthew and his class discussing “The Magician’s Nephew”

I’ve been posting a lot recently (here and here for example) about the power of writing to boost Ratio in the classroom- how writing among other things can cause every student to answer a question instead of just a few who volunteer to speak and how the desirable difficulty writing create facilitates learning and memory.

So I thought I’d share this outstanding example from Matthew Tipton’s classroom at Caldmore Primary Academy in Walsall, England.

Matthew’s students are reading The Magician’s Nephew and Mathew wants them to recognize and reflect on an echo of the Bible in C.S. Lewis’ text.

He uses the Everybody Writes technique beautifully to do that.

Here are seven details I really appreciated about how Matthew employs the Everybody Writes technique here:

1)I love the placement of the writing: immediately after they’ve finished reading a section of the book and while the chapter they’ve read is still fresh in their memory. The writing becomes a tool to process and make sense of the book. Matthew is socializing his students to use writing to reflect as they read.

2) I love the way Matthew voices the question to students. His tone in asking them “How does this story link to the Bible story of Adam and Eve?” is thoughtful and reflective. His delivery is slow and thoughtful. He is mirroring in the way he asks the question the sort of thoughtfulness he’d like them to use in writing and setting the tone.

3) I really appreciate they way Matthew gives students a few moments of wait time to gather their thoughts before he sends them off the write. This makes it more likely that they will all engage the writing immediately and see their peers busily engaged in writing because they will have already started to develop their first thoughts.

4) The task design is really nice: 3 minutes feels perfect–not too short and not too long–and i am a big fan of the phrase “stop and jot” as the name for the activity. Giving it a name makes it a recognizable procedure that students know how to complete but the formative nature of it–the word jot especially–lowers the stakes and makes it feel to students like they don’t have to know everything before they start writing.

5) I love that the prompt is so knowledge-rich–connecting the book to the story or Adam and Eve.

6) Coming out of the stop and jot Matthew does a great job of “narrating hands”–counting and acknowledging the students who’ve volunteered to speak and encouraging more. His narration makes the enthusiasm of many students more visible to their classmates. By making the norm of hand-raising more visible he helps students to participate themselves.

7) He gets a lovely and thoughtful answer from the first student he calls on. If anything too lovely. She has a LOT to say–in a good way–but sometimes from a discussion dynamics stand-point an answer that’s too long can be a challenge and cause other students to tune out. So when students give you the “kitchen sink”… ie everything they can think of in response to a question–saying something like, “Pause there. Lisa has spoken about the evil in the garden. Who is the evil here?” or “Pause there. What an important phrase ‘evil in the garden’ is. That’s lovely, Lisa. Can anyone build on that phrase?” is a great way to honor the eager student and also bring his or her peers into the conversation.

The post Seven Details from Matthew Tipton’s use of Everybody Writes appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 13, 2024

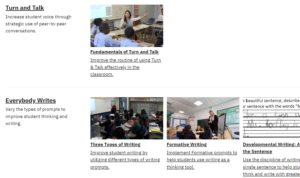

Announcing Amazing New Modules at TLAC Online

TLAC Online is Teach Like a Champion’s platform for teachers to learn and practice our techniques. This summer we nearly doubled the Engaging Academics content! We added five five new modules to help increase student engagement in your classroom.

Ratio : Improve the level of student engagement and thinking in your classroom with this reflection activity. Turn and Talk : Increase student voice through strategic use of peer-to-peer conversations. Three Types of Writing : Improve student writing (and thinking!) by utilizing different types of prompts. Formative Writing : Implement Formative prompts to help students use writing as a thinking tool. Lesson Preparation : Set yourself and your students up for success by taking these steps before class even starts.

The modules are designed for self-study, though they can also be used as a coaching tool, and each takes between 15 and 20 minutes to complete.

If you’re interested in experiencing a module yourself, check out our Positive Cold Call module, which is always available to the public.

We’ve learned a ton about how to get the most out of the modules from fantastic partners who have used TLAC Online in a variety of different ways. Check out a few of their stories below:

Capital Prep Public Schools in New York City and Connecticut have been assigning the modules for teachers to complete independently after observations. This year they will also use the videos as a way of launching their coaching meetings so teachers have a clear model for their action steps.Shout out to Southern Cross Campus in Auckland New Zealand who have used the modules for the past year to bring TLAC not only to their campus, but to their country! Southern Cross led two school-wide trainings using our Plug and Plays and have been assigning a group of teachers modules to continue their learning.Thank you to our TLAC Fellows, Dr. Rene Claxton and Dr. Robert Arnold, who have been using the videos and technique notes from the modules to train medical educators at University of Pittsburgh and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine. They plan to use them with faculty at Sinai School of Medicine this fall.Achieve Excellence New Mexico has used the modules for several years to support their new-to-career teachers. Every participating teacher is given an account and meets regularly with a mentor teacher who guides their process and provides opportunities for reflection.And one of our oldest clients, Waller Elementary in Bossier, Louisiana, has teachers complete the modules together in Professional Learning Communities who select the topics that interest them the most and then reflect and implement together.

If you have a great story for how you’ve used the modules either yourself, for your team, or across your campus, we’d love to hear from you!! Email us at hsolomon@teachlikeachampion.org.

With a subscription purchase, you get full access to all 46 of our modules, each of which includes multiple videos and opportunities to practice, as well as best practice tips for implementing the techniques. If you’re interested in purchasing a license for the modules, please click here.

The post Announcing Amazing New Modules at TLAC Online appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 4, 2024

Strong Procedures and Routines for Participation: The Critical Role of Teacher Practice

Probably the smartest investment you could make…

Recently, I wrote about Means of Participation– how at the beginning of the year it’s critically important to design and optimize and make a habit out of the way students answer questions–with attention to the details.

I shared a video of Sadie McCleary’s Turn and Talk/Cold Call procedures and how they deepened and broadened student participation.

And I mentioned that preparation and practice by teachers was a key to achieving that kind of success.

You can see Eric snider and Kirby Jarell doing that in this video:

Kirby and Eric are practicing their Turn and Talks and building their own routine—how will they give directions so they are clear and productive?

Their goal is to give those directions consistently to send student into the task using similar language every time. That way the cue is part of the routine. But also making sure the directions are clear the first times you do it so behaviors are optimal.

But of course each teacher will want to do that slightly differently. Kirby and Eric are both great teachers but they are also slightly different.

So notice that they not only talk about what they should say but they practice as well. Kirby wants to use some of Eric’s suggested language but 1) not all of it and 2) she wants it to sound and feel like herself. So she rehearses–multiple times, making slight changes, until it feels right and she’s internalized the language she likes in a way the feels like the teacher that she is.

It only takes five minutes. But the rewards they get in clear and productive classroom culture will be worth it a thousand times over.

The post Strong Procedures and Routines for Participation: The Critical Role of Teacher Practice appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

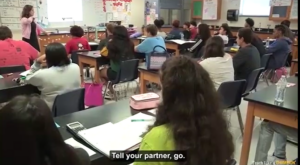

Step One for a Productive and Positive Classroom: Strong Procedures and Routines for Participation

The beginning of the year is the time to be installing strong procedures and routines in the classroom.

It’s one of the most important things you can do to set yourself up for a productive and positive year of learning.

When there’s a right way to do a task and it’s familiar to the point of habit, it “hacks working memory”- that is, it allows students to complete the task with working memory focused exclusively on the content and not the details of the task.

Further familiar procedures oddly build a sense of belonging. Every faith sings or worships in unison. When we all do something the same it signals that we are parts of a greater whole.

Consider Turn and Talk. In this short clip, Sadie McCleary asks her students to discuss the characteristics of a gas and the room crackles to life. Students are thinking about elasticity and temperature, not: “Wait who am I talking to?” “Will they really want to talk about chemistry with me?” and “What will happen afterwards?”

And of all the procedure and routines in an effective classroom the most important are for the things students do most frequently and that most effect learning. And the most common thing students do that most effects their learning is: answer the teacher’s questions.

If there’s a strong procedure for Turn and Talk and everyone knows it cold, then learning and thinking can be maximized and–as Sadie does here–a sense of “flow” can often be created in the classroom–students are busy and active throughout and more likely to lose themselves in the content.

In fact you’ll notice that there is more than one familiar-procedure-for-answering-questions-made-a-habit in Sadie’s classroom. In addition to Turn and Talk, Sadie uses Cold Call as well. Students give strong answers in part because they use the Turn and Talks optimally; they know they might be accountable to discuss their thinking afterwards. This part too is predictable.

There are in fact a relatively finite number of productive ways that students can answer a question in class… perhaps five:

They can raise their handsThey can respond when the teacher cold calls them.They can answer by turning and talking briefly with a classmateThey can write their answer briefly in a notebook say or on a white boardThey can answer chorally

When we write or present about this idea my colleagues and I call it Means of Participation:

How you answer the question is as important as the question itself.Intentionally design the process for how students will do each of these.Use them frequently and consistently right away so they become routine.Cue students clearly so they know which routine you are using.Then students can participate optimally and you can ensure deep and broad participation among your class like Sadie does.

And as we will see in part 2, designing and building these routines responds to preparation and practice….