Doug Lemov's Blog, page 24

June 15, 2020

Three Takeaways from Daisy C.’s Outstanding “Teachers vs Tech”

To the battlements, comrades…

To the battlements, comrades…I’ve just finished reading Daisy Christodoulou’s new book Teachers vs Tech: The Case for an Ed Tech Revolution.

It is, as everything Daisy writes seems to be, outstanding: clear in untangling complex issues; profound in unexpected ways; grounded in logic and research.

Here are three ideas I found profoundly useful from it:

1: To understand how to use technology start by understanding cognitive science.

Her primary argument is that as a profession we misunderstand or undervalue the science available to us about how learning works. This includes the critical importance of attention, background knowledge and the ways in which working memory, long-term memory, and perception interact, (e.g. cognitive load theory). Because of this, our efforts to employ technology to improve education go awry.

If you do not understand how knowledge shapes learning you will overvalue discovery learning which presumes erroneously that teacher expertise and student background knowledge are relatively unimportant; your goal will be to immerse students in rich and unstructured technological environments without prepping them with background knowledge and without mediation of a teacher on the premise that this will help them learn. It is unlikely to and what learning does occur is likely to have a disparate impact.

Technology accelerates. You cannot use it well if you are using it to accelerate faulty conceptions of learning. Start by understanding the brain.

2. The most useful applications are often less visible

Daisy is not a technophobe. Hers is a book about using technology not fighting it, and she has some really useful suggestions. One of her simplest and best is the use of flashcard apps to aid students in studying and building memory through retrieval practice. One of the smartest things a teacher or school could do would be to build a set of bespoke flashcards for students to use in reviewing and studying on their devices. These might be aligned to a knowledge organizer if you have one, perhaps, or upgraded regularly with key course insights.

Another great suggestion (pages 84-91, sports fans) is about design rules for visual information… visuals and videos are far more prevalent and can add immense value but combining words and images effectively is a science. Eliminate all extraneous information from the visual. Cut the text up into small chunks and insert it into the visual (video or image) to explain it in small manageable, sequential chunks. Basically it’s a section on how to do what you’re already doing much better.

3. It’s a battle for attention

The most powerful part of Daisy’s book for me was her discussion of the research on attention and distraction.

One thing that is obvious but that I hadn’t really thought of is that in the current world of remote teaching, students almost always have BOTH a laptop and a phone accessible in their learning environment. This is relevant because 1) people use phones and laptops differently and 2) it allows them to ‘multitask’ [in quotes for a reason… see below] even more.

My littlest described this to me over the dinner table last week. “I look at the screen during my zoom calls and I can see the blue light shining up at so many of [my classmates’] faces. It’s so obvious they’re on their phones but my teachers don’t (or can’t) look closely enough to see it.”

Anyway, the book provides a summary of some of the research on attention:

“In a 2016 study by Carter, Greenberg and Walker, students were allowed to bring devices to some sections of their course, but not to others. They did better in the sections with no devices.”

“In a 2018 study by Glass and Kang, students were randomly split into two lecture groups. One group were allowed to bring devices to their lectures…the others… could not bring a device to the lecture. Students in the no device class did better on the final assessment…”

“When undergraduates at the University of Texas were asked to do a series of cognitive tests. They did better if they left their phones in another room and worse if the phones were on the desk in front of them. The effect held even if the phones were turned off.”

And multitasking:

”The research suggests we are not capable of true multitasking. Instead what we end up doing is task switching, that is, switching our attention back and forth between the two tasks in a way that makes performance on both slower and more error prone…. Even the websites and applications [eg zoom] that aren’t trying to distract you are part of an ecosystem that is. It’s clear too that this kind of distraction is bad for learning as it promotes multitasking (or task-switching) and reduces the working memory resources going toward the topic being studied.”

More data:

“Other studies have asked students to place screen recording

software on their laptops and monitored their media use during lectures [these

are undergrads]: 94% of them used email during the lecture and 61% used instant

messaging. Another similar study found that in a 100 minute lecture on average

students spent 37 minutes on non-course-related websites.”

“Another study from 2017 showed that in their general daily

use of their laptops, undergraduates switch on average from one window to

another in their browsers every 19 seconds.”

On Net: “When we use a connected device, we are using a device that is plugged in to a distraction engine.” We should do that with caution. One of the other wise suggestions she makes–beyond the control of teachers alas–is the development of context-specific devices, designed for schools that would limit access to the distractions that mean an instant downside to the introduction of any connected device.

The post Three Takeaways from Daisy C.’s Outstanding “Teachers vs Tech” appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 10, 2020

Announcing New Upgrades to our TLAC Online Training Modules

Five new modules…and check out the link at the bottom of the post to sample our new site architecture…

Five new modules…and check out the link at the bottom of the post to sample our new site architecture…Our online TLAC modules just moved to a new home and we think this represents a significant upgrade… at just the right time.

As many of you know, we’ve been experimenting with how to

bring our teacher training content to an online setting for several years- a

lucky head start given the sudden urgency of online training in the COVID era.

That said, our work designing online training has been informed

all along by a healthy skepticism. We’re only interested in putting training online

if we’re sure it will really help teachers improve their craft, and we knew

from the outset that would only happen if the modules were dynamic,

practice-based and interactive.

Our first modules of TLAC Online, developed with colleagues from TogetherEd, were a pleasant surprise. We made them knowing we’d pull the plug if they didn’t measure up but we screened the final project and thought to our own surprise: Yeah, that will work.

Now we’re happy to offer an upgraded version, just when

schools are clamoring for more and better online training materials.

So what’s in the upgrade?

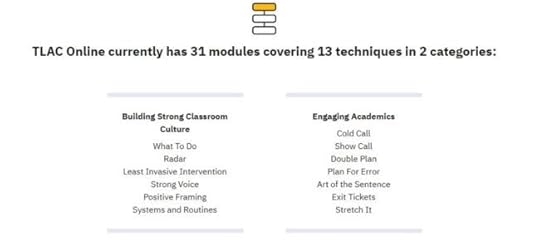

First, we’ve just added 5 new modules on building strong Systems and Routines in classrooms. This brings TLAC Online to 31 modules covering 13 techniques.

Each of the modules remains organized in 4 parts. Watching video, studying the details of the technique, trying it out via several rounds of practice, and then self-study- watching back your practice and/or sharing it with colleagues—at your discretion—for further feedback.

The second major upgrade is our site architecture. With insight from first-generation users, we’ve changed the interface to an airy, streamlined, intuitive design that makes the time you spend studying the craft online even more enjoyable.

We invite you to spend some time in our free “sample” module: Positive Cold Call. We are excited to hear what you think and how you use the modules in your schools and learning communities.

The post Announcing New Upgrades to our TLAC Online Training Modules appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 9, 2020

Putting It All Together: Scenes from Joshua Humphrey’s Asynchronous Math Lesson

The reference sheet is gold; the simple animations are gold; but Joshua’s ability to ‘dissolve the screen’ is the best part of all…

The reference sheet is gold; the simple animations are gold; but Joshua’s ability to ‘dissolve the screen’ is the best part of all… Just finished watching footage of Joshua Humphrey, who teaches math at KIPP St. Louis High School. Joshua’s lesson was full of great moves that I thought others would benefit from watching as much as I did.

Background: The footage I’m sharing is of an asynchronous lesson. Joshua’s students watch two short asynchronous lessons per day and then complete a brief assessment which they send to him where they apply the skills he’s teaching them. Just the idea of keeping asynchronous lessons short and dividing them in half was a really good takeaway, in and of itself. We’ve all been on a 90 minute zoom call and felt our focus fading. Dividing up the on-screen tasks into shorter chunks with an off-screen task in between seems likely to help students sustain their pace during the day and maintain better focus. Pacing matters. This lesson was about 12 minutes! Short and sweet. That said, there was so much good stuff in there that I had to break the highlights from that 12 minutes into three chunks.

Section 1

This is from the very beginning of the lesson. Joshua is talking about the objectives and transitioning into the Do Now.

Some of the things that struck me:

We’ve used the phrase “dissolve the screen” a lot on this blog to describe how teachers make students feel connected and like they’re in the same room with the teacher in the way they talk about the work. I keep having to remind myself as I watch this that Joshua is sitting alone in his living room as he tapes this. It feels so personalized. He’s carefully prepared but not over scripted. It feels like he’s talking to just you and that answers a question that’s wroth asking: Why bother with asynchronous lessons at all? Why not just send kids to Khan Academy? The answer, Joshua’s teaching reminds us, is at least in part: Even asynchronously, relationships matter. Joshua’s decision to restate the objectives in “human” terms… so you’ve gotta tell me about all the parts [of a polynomial] ok? What do they means… is a powerful example. It’s so humanizing- the sort of thing you’d do if you were really in the room with students.

But also notice Joshua’s pacing. Even though he’s brilliant at dissolving the screen, Joshua is also all about value. He’s not wasting time. Love the way he moves right to the Do Now and gets students down to it. One of the things we advise teachers to do is to have students actively engaged in doing an active task within three minutes of the start of class. If you start with a lot of talk you risk sending a clear message about the passive nature of online learning.

Side note: Love that Joshua recalls the setting students are familiar with “Just like any other class you all have a Do Now…” Love is really clear What To Do Directions. “Pause it right now.” Love that he smiles so often and seems happy to be there!

Section 2

We’re picking up after the Do Now here as Joshua reviews the answers.

First, this is a good example of implicit feedback. For pacing purposes it is often necessary online. Implicit feedback says: “Here are the answers, compare yours to mine.”

I loved that Joshua used very simple animations that highlight the answers visually as he goes through the problems. This helps to maintain students’ focus on what he’s talking about and maintain their attention during implicit feedback.

The challenges of implicit feedback are that 1) students can skip doing the work or 2) students can believe their answers are the same as the correct answers we show when in fact they’re not. The Dunning-Kruger Effect is the name for the tendency of people with lower skills at something to also not perceive the things they did wrong. We say: “If you said something like this you got it correct.” Students look at their answer and say: “Yeah, I said something like that,” whereas we would look at their answer and say: “Whoops still missing a few things.”

That why I loved his decision on problem #3 to lead not with the answer but with a discussion of a common error–also highlighted in red. It’s a smart way to make sure students aren’t breezing through the answers saying “yup got that!” etc. And obviously it gives him the opportunity to do a bit of common error analysis, which is one of the most valuable parts of Checking for Understanding… even in an asynchronous setting.

Finally Joshua is just so animated and engaging as he talks through the common error. It’s so easy to fall into the trap of seeming wooden online, like a talking head, especially when we’re just taping ourselves. His expressiveness–gestures, voice inflection–his easy going way of lowering the stakes.

Section 3

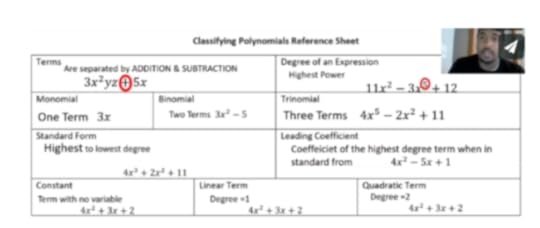

Now to the heart of the lesson. Joshua kicks it off with this AMAZING knowledge-organizer.

This is such a brilliant tool to kick the unit off with. An easy all-in-one-place reference sheet to define all the terms students will need. He again uses super-simple animations to focus students on what he’s explaining as he works through the terms.

And you can feel the benefits of Joshua’s dissolving the screen again as he moves on the the practice: “Ok, I got you.” He’s constantly reducing students’ potential anxiety through his own relaxed demeanor. So compelling!

Thanks to Joshua and the team at KIPP St. Louis for sharing your work with us!

The post Putting It All Together: Scenes from Joshua Humphrey’s Asynchronous Math Lesson appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 27, 2020

(A)synchrony In Action: Eric Snider’s Hybrid Lesson

Sometimes a hybrid is just what you need….

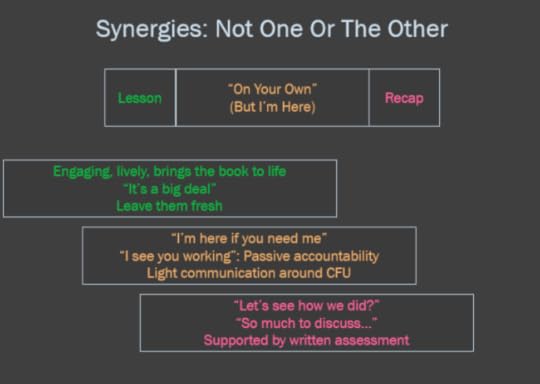

Sometimes a hybrid is just what you need….By now most people are familiar with the terms synchronous and asynchronous… and with the benefits and limitations of each type of online teaching.

Synchronous teaching lets us check for understanding, build habits of engagement and accountability, and gives us the chance to build connections with students. But it’s limited in the depth of the work you can assign. Some students don’t have reliable technology. And it’s exhausting. Four zoom calls a day would make a even a yogi shudder.

Asynchronous teaching can allow students to work at their own pace on deeper assignments. But it’s hard to know how they’re doing and whether they need help. And it can be a drain on energy too.

For these reasons we’ve been talking a lot about ways to maximize the synergies between the two models, and this video of Eric Snider’s class is a great example of what might be a ‘best of both worlds’ model.

The idea is that you could kick off class with a short synchronous lesson of say 20 sharp and very engaging minutes.

Then you could assign work for students to complete asynchronously. But you could have them “remain on the line” while they worked. That is, they could been on zoom with you still but working independently with you occasionally checking in with individuals or simply saying “I’m here if you need me.” Like live office hours. You could let students turn their cameras off or you could provide some soft accountability–as you’ll see Eric do–so they know you see them working by having hem leave them on.

Then at the end you could bring everyone back together to discuss what they did or review answers.

Here’s how Eric did that, most impressively, I might add, in a recent lesson on Rita Williams-Garcia’s One Crazy Summer:

Some notes:

The video starts with Eric playing the audiobook version of the novel over zoom to his students. You could do that–pretty engaging–but no reason you couldn’t read the text yourself.

I love the way Eric sets up the independent work: ‘it’s the climactic moment’ and he’s full of questions that make it seem fascinating (“Why does Fern keep barking?”) and like a big deal (“Get ready for a plot twist as you now read on your own…”).

Also like the clear-as-a-bell task directions that remain on the screen for students.

Love the moment when Eric reinforces kids who are focused and attentive to their reading “I see Armani..”

Love the way he asks them to “shoot him a chat” if they need more time… really taking advantage of his ability to assess where they are in real time.

Anyway I think there’s lots to reflect on here in watching Eric use this hybrid model. Hope it’s useful!

The post (A)synchrony In Action: Eric Snider’s Hybrid Lesson appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 26, 2020

Checking For Understanding Online with Eric Snider

Checking for Understanding is one of the biggest challenges in teaching; online you can multiply that tenfold. It’s like trying to assess how well your class is doing while looking in through the keyhole.

That’s why I found this video of Eric Snider’s so profound. He’s teaching Rita Williams-Garcia’s One Crazy Summer (adapting the book unit from our curriculum, actually, I’m happy to say) and does a great job of constantly assessing where his students are.

Here’s the clip:

What I love about it:

WHEN Eric Checks for Understanding. CFU with reading is a two-step process. First we need to understand that students can generate meaning directly from the text without support from others–which is often tacitly often provided by the discussion after the reading… oh! that’s what was going on! Then, later, we need to make sure they understand the full interpretive context based on input from others. And it’s to easy to assume that kids who can do 2 could do 1. Not so. Often they are able to use subsequent discussion to fill in the gaps in what they missed while reading. So it’s brilliant that Eric checks right away here, before the discussion.

What a great use of the Chat to gather real time data. There aren’t many ways that online teaching is better than in-class but one benefit is that it’s easy and simple to gather data like this. it would be harder to do in the classroom.

Eric checks twice! It would be so easy to assume that once you’d explained, “Delphine is ashamed of the creases not the rally,” students would instantly get it. It seems that way to us because we are expert readers and we perceive easily. But it turns out even after explanation #1 students are still confused.

Also what a beautiful culture of error. “We’re pretty split and it looks like we might be a little bit confused…” Eric says. No judgment. It’s safe to be wrong.

Love, love, love the way he narrates the positive: “Thanks Lisa, Thanks Juwaun” He makes students feel seen when they work hard and he normalizes active engagement by helping students see it all around them.

Finally, there’s Solari and the lesson she teaches us. She’s answering from the back seat of her car, for goodness sake … and she crushes it. Yes, this is really, really hard. But kids are resilient. They can do it when we ask for their best and give them ours.

Onward, friends.

The post Checking For Understanding Online with Eric Snider appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 22, 2020

Excerpt: The Coach’s Guide to Teaching

Teaching is knowing the difference between ‘I taught it’ and ‘They learned it.’

Teaching is knowing the difference between ‘I taught it’ and ‘They learned it.’I’m closing in on my manuscript deadline on my new book, The Coach’s Guide to Teaching. The sense of urgency–some might call it desperation–is palpable. But I’ve just finished Chapter 4, which is about Checking for Understanding. Here’s an excerpt to whet your appetite. Hope you enjoy

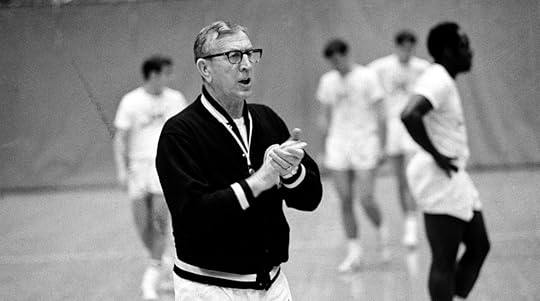

John Wooden was among the greatest coaches of the 20th century. No doubt he was among the winningest, but he remains among the most admired and most quoted, too. Wooden’s stories, aphorisms and principles are often afforded nearly canonical status and retold like parables from the gospel:

The story of how he began the UCLA season by instructing his players in how to put on their socks reveals that we should begin at the beginning- and perhaps that the beginning starts earlier than we think.

The tale of his response to Bill Walton’s announcement that he didn’t want to cut his hair in accordance with team rules–Wooden praised Walton for standing up for his convictions before adding, “and we’re sure going to miss you around here, Bill”—reminds us that the test of our principles is whether we apply them to our best players and when they result in our losing games.

Perhaps because he was a teacher before

he became a coach, his wisdom about the teaching side of the craft is

practical, wise and so far, mostly, timeless. Of all his adages and sayings,

the one I find most useful is his definition of coaching (and teaching). Teaching,

he said, was knowing the difference between “I taught it” and “They

learned it.” No matter the setting,

bridging the gap between those two ideas is at the core of what teachers do and

often the greatest challenge of the job.

Certainly it is in coaching sports.

Any teacher seeks to present a

concept for study as well as she can—clearly, memorably so that as many students

understand as much of it as possible–but no matter how good the initial

instruction, learning will break down. Gaps will emerge. Often our first

response is to try to establish whose fault that is, but mostly it is what

happens when people try to teach and learn things, especially when they try to

teach and learn things that are challenging and complex. Quite possibly the

greatest insight from Wooden’s adage is its calm presumption that the gap is

inevitable. It is not a question of whether it exists but how we deal with it. Teaching,

he proposed, is not eliminating the gap; it is understanding it. It is the

coach’s job not to offer a perfect initial explanation but to seek out and

anticipate the ways athletes will struggle. To be a great coach is not just to

have a deep knowledge of the zone press, not just to be able to translate it to

players, but to see what goes wrong as they try to learn it. This process is called

Checking for Understanding and is as challenging to master as it is important.

Among other things it requires coaches to shift how they prepare to teach and

even how they observe when athletes are training.

The Trials of Looking

In chapter 1 I discussed the

critical role perception plays in decision making for athletes. To perceive

well is not only necessary to good decision-making, in many cases the line

between perception and decision blurs. An athlete reads the first incipient

cues that suggest how her opponent will move and is already acting on them in

real time—we call it anticipation; it is as if she knew what her opponent might

do–and she succeeds. Or, alternatively, her eyes are elsewhere when the

critical information—they are pressing!– emerges and so she fails to react. The

perception and the decision are hard to separate. Athletes can be lucky once or

twice but in the long run their decisions can never be better than their

capacity to see and understand what is happening around them.

It is the same for coaches. A

coach’s ability to teach and develop athletes is limited by his or her ability

to perceive what they are doing during training- a task that is far from

simple. We presume that seeing is all but mechanical–you direct your eyes toward

an event and become aware of what is happening–but in fact this couldn’t be farther

from the truth. Seeing is technical, challenging, and subjective, a skill you

might argue, certainly a cognitive process far more than a physiological one. All

of which is especially important to recognize because the ability to see

accurately is a coach’s first skill.

Here’s a tiny example of what I

mean: a stoppage at a recent training led by a very good young coach. He was

using passing patterns to familiarize his players with common movements in buildup

play and he noticed that girls were often static when waiting to receive a

pass. He paused them briefly and,

standing next to a central midfielder, said, “Girls, when you see the outside

back receiving the ball, you know that you are going to be one of her primary

options, so you don’t just have to be ready to receive the ball, you

have to create separation so that you make an opportunity. That means a

movement like this [he demonstrated checking away] to take your defender

away-and then come back to the ball. As we work on these patterns, I want to

see you making movements like that. Every time. Check away, then come back for

the ball. Go!”

By the basic rules of feedback (see

chapter 3) his feedback was strong. He explained one idea, demonstrated and described

the solution clearly and quickly then gave athletes a chance to try it right

away. But he failed to do something so simple that most coaches don’t even

realize when they fail to do it. He failed to observe. He positioned himself

well afterwards to watch for their follow-through, he looked at the girls

cycling through the patterns, but after he said ‘go,’ eight out of the next ten

girls receiving the ball failed to make a movement like the one he had described,

and somehow he did not notice. He was looking but not seeing; perhaps he simply

assumed they were doing it and was only half-looking. Perhaps he was thinking

about something else. But for whatever reason, play went on without correction,

and his next stoppage addressed a new detail.

He had taught it, but they had not

learned it. Or even done it really, and it’s not hard to imagine a Saturday,

not to far down the road, where at halftime he would say with some urgency, and

perhaps even frustration, edging into his voice, “Girls, we’re static.

We’ve talked about using our movements to create space to receive. We’ve got to

be creating space.” In that moment he will

be describing John Wooden’s gap to them: Girls I taught you how to create space,

but you have not learned it.

There are a wide range of reasons why athletes would not be able to execute something they did in practice in a game, and I have tried to discuss many of them elsewhere in this chapter and this book. There could have been insufficient variation and spacing of retrieval practice so that athletes forgot what they did a few times in training on game day. The training environment might have never progressed to a complex enough setting to prepare athletes to execute under performance conditions. Athletes might have failed to read perceptive cues telling them it was the right time to execute a skill they know how to do. But in this example I am describing something much simpler to make a point about the perils of observation for coaches. A coach asks players to do something, athletes fail to do it, right then and there, and the coach fails to see it.

To remediate the learning gap the coach might have said something like: “Girls, I didn’t see the sorts of movement we discussed there. Let’s try again.” Perhaps he might have added, “I’ll watch ten of you now and shout “yes” or “no” to show whether I see a movement away and back.” Perhaps he might have said, “Girls, we’re struggling to make those movements and I suspect it’s because we’re trying to make them too late. Try to start them a little earlier and see if that helps.” Perhaps something else. But a coach can only respond to errors that he sees. First you have to perceive the error, and surprisingly, that is the step where the process breaks down far more often than almost anyone would suspect.

In fact if there is one thing I can offer in this chapter to help you teach better it is to urge you to resist the temptation to judge this coach. Some version of this story has undoubtedly played out in one of your recent trainings whether you coach 7-year-olds or professional athletes, whether you are a new coach or an established and respected veteran. There is a part of you that does not believe this, but I am 100% certain it is true. This is the remarkable part of the story. With some regularity the athletes you train simply do not do what you have asked them to do, and you fail to see it. If someone showed you a video afterwards, they could easily point it out to you. You asked for the combination to end with crosses on the ground. Count the number of crosses on the ground. Or, you asked them to practice using both feet. Count how often they use their left foot. What was hidden in the moment you were coaching would now be obvious. Players were not striking crosses on the ground. Almost nobody used their left foot. You fail to see what was right in front of you, therefore to fail to understand your athletes and their struggle to learn. We all do this. We are all, with some frequency, the coach I have just described. The only question is whether we will have the humility to accept this. Only then can we take steps to change it.

Science tell us that we see only a fraction

of what’s right before our eyes and there are a variety of reasons for this. One

is attention. We miss things because we’re not concentrating on looking. We’re

looking passively. Observing carefully to see what 16 athletes are actually doing

at a complex activity is hard work, and the brain is designed to only work hard

when it must, when we force it to. What’s more ‘observing’ doesn’t feel like

coaching so we may be unlikely to focus on making the effort it requires if we

don’t see it as a critical task. Much of the time we should be observing

intensely, we feel like we should be saying something or at least setting up

some cones. Instead of really looking we’re thinking about what we’re going to

say or do next or who’s going to start on Saturday. But looking well takes

single-minded concentration. We have to see it as a task. We have to force out

minds to do it actively.

There are technical problems to

overcome as well. Your optic nerve connects to the back of your eye in a spot

about fifteen degrees to the side of your center of vision, for example. There

are no receptor cells there. Your cortex receives an incomplete picture of the

world around you. To compensate, it fills in the gaps with what it thinks it’s

likely to have seen in the blind spot. It uses other sources of information— your

other eye, what you saw when your eyes looked in the space you cannot see a few

moments ago. The brain does this so

seamlessly that most people never even know the blind spot is there[2]

but it is shockingly large. We often say

that we see the world as we imagine it to be and mean that metaphorically, but it

is often literally true as well. What we think is there is different from a

person standing beside us.

Our perception is subjective and immensely

fallible. We just don’t want to believe it’s true. As Chabris and Simons put

it, “We are aware of only a small portion of our visual world at any moment” but

“the idea that we can look but not see is flatly incompatible with how we

understand our own minds.” We can only fix the first part if we fix the second.

If we want to be better at developing athletes, we have to take the task of

seeing them as they learn far more seriously.

Let’s return for a moment to the

session where the girls failed to make the checking movement their coach had

asked them to make. The technical name for not seeing what is right before our

eyes is ‘inattentional blindness,’ and one reason I saw what the coach did not is

that, I had been discussing the

challenges of observation with a group of coaches just the day before. I walked

in the door expecting it to happen. I saw it not because I am especially

perceptive—I am as likely as anyone else to miss what is right before my

eyes—but because I was prepared, and this Chabris and Simons tell us is the key

to seeing better. “There is one proven way to eliminate inattentional blindness,” they write. “Make

the unexpected object or event less unexpected.”

[2]

Any cognitive scientist can prove it’ presence in seconds https://www.eyemichigan.com/what-is-a-blind-spot-how-do-i-find-it/

The post Excerpt: The Coach’s Guide to Teaching appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 13, 2020

Means of Participation Online with Ben Esser

How to Play…

How to Play…As you know we’ve been watching and posting a ton of video of great online teaching.

We posted this great clip of Alonzo Hall and Linda Fraser’s A+ procedures and routines.

We posted this great clip of Ben Esser ‘dissolving the screen.’

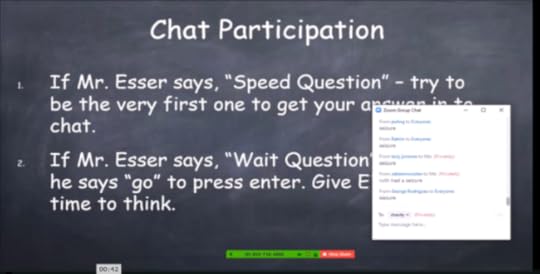

Today I want to share another clip of Ben, here taking a page from Alonzo and Linda’s playbook- but with arguably the most important system of all: Means of Participation, which is being explicit about different ways for students to participate.

We’ve posted on Means of Participation in bricks and mortar classrooms a few times.

Here Ben makes it really clear for his students: What are the procedures for answering verbally? What are the procedures for answering a question in writing? In fact there are two different ways, depending on Ben’s purposes. Here’s the video. I’m sure you’ll love it as much as we did here at team TLAC.

The post Means of Participation Online with Ben Esser appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 11, 2020

Dissolving the Screen

“I see the work you do and I value it. It connects us…”

“I see the work you do and I value it. It connects us…”Distance learning leaves teachers less connected to students and students less connected to teachers. Ideally, then, the way we approach online learning would address that challenge by not only making our students feel more connected but by making them feel connected to us specifically by the work we do together. That is, we would send the message that when you engage in the work of learning it connects us- because I notice it and value it and just maybe find happiness in it too.

My colleague Jen Rugani gave the name “Dissolving the Screen” to this idea, and last week I posted a great video of Achievement First’s Ben Esser doing that. People really seemed to like it so I thought I’d post a few more examples. These are from Sean Reap, Linda Fraser, Rachael Shin and Deb Gravina.

Sean’s opening brings To Kill a Mockingbird to life and remind students of how much they’ll have to talk about when they’ve read it too. Linda subtly notes that she “can’t wait to see who can solve” a challenging problem. Rachael lets students who do strong daily work feature in the next story problem, and Deb reminds students that she’s always available to talk about their work as they engage in it.

The message is: doing the work connects us and I see and value all your efforts.

Hope you’re able to borrow one of these ideas as you work with your students.

The post Dissolving the Screen appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 10, 2020

Perception, Learning and Expertise: Anton McCafferty’s Online Sessions

Last week I posted a couple of videos made by colleagues of mine at New York Red Bulls as they worked remotely with young athletes to develop their perceptive skills. In the videos, a coach asked players to watch for, study and analyze one very focused topic in a sustained way.

Today I want to share two more examples of the same task. These are fascinating for similar and different reasons, one of which connects to a key finding in the science of learning and I believe this makes it relevant to all educators, as opposed to just coaches.

Here’s the first video. The coach is Anton McCafferty and I think you can glimpse what is evident throughout his session: he is a master of culture-building. His sessions are safe and inclusive and playful but also serious, rigorous and stress accountability.

The clip starts with Anton showing the girls a very short video of a professional player making his first touch in receiving the ball. Anton has given them five topics to think about and he sets them to writing about it right away.

You’ll notice that he’s put a circle around the player in question to make sure that his students watch the right moment. I am going to come back to this later because it reflects his awareness of something deeply important: experts–like Anton–see differently from novices–like his students. If he said, “Watch the player who’s about to receive the ball,” it would be obvious to him based on the location of the ball and the positions of the players who that was. But it is NOT obvious to novices.

After giving his students the opportunity to think in writing about the question before discussing–which ensures that everyone answers, and increases their comfort in participating–he Cold Calls a student. But his technique is perfect. In a warm, easy-going voice he asks her, “Do you have an answer?” There’s no wrong answer to the question and his phrasing opens the opportunity for her to voice misgivings–“I’m not really sure” or “I didn’t see it very well”–or ask a question–“Can I see it again?”

He’s set her up to be successful, however–clear task; time to think; safe and warm tone–and her answer is good, so Anton ties it back to their shared vocabulary. What she is describing is an example of “awareness” he tells her. He’s pushing the team to speak the same language.

Later as she begins to struggle, he asks his students, “Can anybody elaborate on that?” He’s careful to honor the first answer by insisting they build off of it. This socializes his athletes to listen to another. And again we see his playful warmth. “Go on then. Talk to me…” It’s rigorous work but the tone is light and the feeling inclusive. You can see these themes play out for the rest of the clip. Challenging questions, accountable culture. Thea is Cold Called. Then Ingrid Cold Called and asked merely to respond: rigor in a warm, safe, and even playful environment. Glory points to Anton.

Now here’s a second clip from his session–it’s fascinating for a totally different reason:

In this video we see more of the same beautiful learning culture Anton’s built. This clip is slightly different in terms of task though because he is asking his students to predict what the player in the video might do with his first touch rather than analyze retrospectively what he did do.

He calls on Gia. “I’m confused,” Gia says. “What player are we talking about again?” This is a massive victory for Anton and his technique. If he doesn’t Cold Call, she just sits silently in her confusion. He’s brought the misunderstanding to light. But there’s such a feeling of safety that she is comfortable exposing her lack of clarity. And Anton responds “That’s alright, Love. We’re talking about this player here. What I’ll do is I’ll go to somebody else and I’ll come back to you…” [Which he does]

But notice the signal that’s starting to come in. Anton doesn’t realize it until later but most of the girls who share their thinking from this point on in the video have made a fundamental perceptive error. The black team is attacking and playing right to left. But they think they are defending and playing left to right. So when Sophie says she’d take a touch forward “between those two players,” she’s referring to the players to the right of the circled players. But for Anton, who is an expert, and who therefore perceives more accurately, it’s hard to recognize this mistake.

After all, he’s just shown them the white goal keeper playing out of the back and the black team intercepting. But then again what was obviously the white team playing back to their own keeper in the first seconds of the video was not obvious to them. They perhaps thought this was the white team attacking. At some point they became confused. Almost all of them. And so they spend several minutes in an apparently rich discussion in which their fundamental perception is wrong.

This is an outstanding example, in other words, of one of the biggest challenges of teaching. Teachers are experts and so it is very very difficult for them to realize the perceptive differences between themselves and novices. They say: ‘look at the problem’ and presume that students see a similar problem. They do not. And this tells us a lot about their receptiveness to discovery-based environments. Asked to learn from being presented with a real-world problem to study, experts “use deep…principles to categorize and solve problems whereas novices use superficial features,” Paul Kirschner and Karl Hendrick point out in How Learning Happens. Your level of knowledge determines your ability to perceive signal versus noise. So while learning to perceive is one of the most powerful things students can do–it’s what Anton is developing here–they are likely to learn from it in correlation to their degree of knowledge. And this means doing two things: investing intentionally in background knowledge first and checking for understanding constantly to make sure we know and can guide players eyes to the right things.

Interestingly, Anton has done both of those things here. He’s given his players five things to look for in assessing first touch. He’s circled the player they’re analyzing on the screen to ensure their proper focus. And yet they still mis-perceive. Which is just a reminder that despite great teaching students will always be at risk of basic perceptive errors that teachers as experts will struggle to recognize.

The post Perception, Learning and Expertise: Anton McCafferty’s Online Sessions appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 9, 2020

On Thinking and Learning

I read them, I cherish them and I remember almost nothing about them…

I read them, I cherish them and I remember almost nothing about them…Thinking is not learning. Thinking is part of the learning process but not all of it. Just striving for lots of thinking or even deep thinking in classrooms won’t necessarily result in learning. Maybe that’s obvious to you. It wasn’t to me for a long time and I suspect in that regard I’m not unique among educators.

I’ve spent a few hours over the last week watching video of teaching with a group of colleagues I respect and admire. The goal is to figure out the moves their teachers can use to boost rigor and ratio. In video of their classrooms I see an immense amount of thinking: thought-provoking questions from teachers and hard-working students striving to answer. They run very good schools, my friends do. But I worry that the thinking their students do is not turning into learning or mastery.

There are, I think, two possible reasons why. The first I’ve written about before: not enough background knowledge. You can’t think deeply about something you don’t know a lot about. Or better put, you CAN think deeply about it but you won’t learn much. “Why is the sky blue?” Without background knowledge, you could think deeply about this all day long and come up with a dozen theories comprised of magical thinking, guessing, myth-making and plausible sounding logic. Societies did this for eons. They thought about the color of the sky. Without knowledge there was nothing learned.

The other reason why thinking does not amount to learning is that there’s no prioritization, review and memory building afterwards. This is a lesson I have had to learn over and over in my own life. I love and value reading and my shelves are stocked with books that have awakened in me the deepest thoughts and reflections. They caused hours of thinking which, whether it was profound to anyone else or not, certainly pushed the limits of what I was capable of. Now I look at those books and remember, mostly, how much I loved them. That’s about it. I read deeply but remember almost nothing. This sadly is true for many of the cherished classes took as a student as well. I loved them. The thinking was profound. I remember the feeling of it. But what else do I remember? Only the warm glow and a hazy detail or two. I thought but I did not learn much.

One change I made recently is to keep a commonplace journal. In it I write down short passages and quotations from books I read. This keeps the ideas alive; prioritizes them and makes them available for easy review. Just choosing what’s important and writing it out long-hand helps but every few weeks I flip through the book and review over a cup of coffee the five or ten most memorable ideas from the books I’ve read over the past year or so. I find I remember even parts I didn’t write down. Suddenly my books are less like museum pieces to remind me of thoughts I loved but can no longer access. I have learned something from them.

Which raises a question for classrooms: to turn thinking into learning: 1) engage in knowledge-building first to make the thinking powerful. 2) Do memory work afterwards–prioritizing, writing, retrieving. This is no after-thought, no coda. It is as crucial as the thinking. As the cognitive psychologists Kirschner, Sweller and Clark put it: “The aim of instruction is to change long-term memory. If nothing has been changed in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.”

The post On Thinking and Learning appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers