Doug Lemov's Blog, page 17

July 28, 2021

A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt: Warm/Strict

To make up for the delay in the publication of TLAC 3.0, I’m trying to post excerpts that readers will find useful. Here’s part of the discussion of the technique Warm/Strict:

In Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, Zaretta Hammond describes the critical importance of teachers who are what she calls “warm demanders”: those who combine personal warmth with high expectations and “active demandingness,” which, she writes, “isn’t defined as just a no-nonsense firmness with regard to behavior but an insistence on excellence and academic effort.”

The magic lies in the correlation, in being the person who can say I believe in you and I care about you and therefore I will not accept anything but your best.

The magic lies in the correlation, in being the person who can say I believe in you and I care about you and therefore I will not accept anything but your best.But warm demanders can be rare because so many people perceive high expectations, firmness, and relentlessness about academic content and firm discipline to be something you do, not because you love young people, but because, somehow, you don’t. You are one or the other: caring or demanding. They are opposites. But of course this is an illusion. The magic lies in the correlation, in fact, in being the person who can be both at the same time, who can say I believe in you and I care about you and therefore I will not accept anything but your best. You must rewrite the paragraph, complete the homework, apologize to a peer you have wronged—because you are worthy of as much.

To do that is to push a student to be their very best.

You can get a glimpse of how those two apparently contradictory ideas live in harmony in watching a video we also saw in Chapter 11: Trona Cenac: Register Shifts. The video is shot on one of the first days of school and Trona is in the hallway, setting norms and expectations before students come into class. You can sense right away how glad she is to see her students and how glad they are to see her. She’s warm, gracious, and caring—full of smiles and reassurance.

But she’s also really clear about what’s expected of them and what they need to do to be successful. They need to come in, take a seat, and get started on their work with urgency. There’s work to be done. It’s not optional. Within this single interaction she tells students she cares about them and expects a lot from them—essentially at the same time.

A teacher like Trona includes the come in, take a seat, get started right away part because she cares deeply about her students. Being willing to do so is part of what adults who care for and about young people do. Certainly it would be easier for her not to shift into the we have work to do, please sharpen up mode, but to merely be adoring and adored. Her students might like her even more, at least for a while, if she did. It would be easier to let them saunter in and get settled on their own time, start class only when they seemed ready, teach for 45 instead of 52 minutes per day, and show movies sometimes just because a movie is a nice break. It would be easier to give almost everyone an A on every paper or better yet not grade papers at all, the better to never have anyone resent you or argue a grade.

Hammond has a name for this type of teacher: the sentimentalist. The sentimentalist is willing to reduce standards for students—either to be more liked by them or, as Hammond writes, “out of pity or because of poverty or oppression.” The sentimentalist “allows students to engage in behavior that is not in their best interest.” The sentimentalist means well but loves to be loved; needs to be needed too much, or chooses the short-term benefits to herself of satisfying personal relationships over the ways strong relationships can foster long-term success for students. Sentimentalism is an occupational hazard. It’s better to name it so that we can all check ourselves as we move through the journey of teaching. Am I too often doing what is easy because I want students to like me? Or am I pushing them—and myself—in a loving way that expects the best of all of us?

For me the technique of learning to be able to be both warm and strict at exactly the same time and finding the optimal balance of those things based on how it affects student learning is called Warm/Strict. It’s learning to be caring, funny, warm, concerned, and nurturing—but also strict, by the book, relentless, and sometimes uncompromising with students. It means establishing the importance of deadlines and expectations and procedures and, yes, rules.

But Warm/Strict does not mean being unreasonable or inhumane. It does not mean never making an exception; rather, it means making such decisions not based on popularity, but based on long-term commitment to your students’ growth.

“In society we don’t get very far if we are rude, if we talk back, if we talk over others, if we don’t listen,” writes UK Headteacher and author Jo Facer. “In schools we need to escape the idea that teaching children how to behave is teaching them ‘obedience,’ a word that for many has connotations of oppression and fear.” Children who treat others poorly are not going to “magically transform themselves,” Facer goes on to point out. They rely on adults, ideally in partnership in and outside the classroom, to steer them towards behaviors that not only allow schools to function well but, more importantly, prepare them to be successful and valued members of society and community down the road.

I want to say a bit about the word “strict” specifically. It’s a fraught word for some but I think it is worth using because it reminds us of something important: A teacher sets limits and expectations for and on behalf of a group, a culture. Young people with whom we are strict may not always be happy with those limits in the moment, but they also usually recognize in the long run that being held accountable by someone who cares about you is an important part of learning to make your way in the world. They are especially likely to arrive at this realization when the adult who is strict shows them that they care—deeply.

The world will penalize a person who cannot meet deadlines. The caring teacher is not the one who allows a young person to make a habit of missing them again and again. The caring teacher says you have an immense capacity for excellence but deadlines matter and I want you to get this in on time. The caring teacher may even work with the student for whom this is a struggle, setting benchmarks, texting a reminder the night before. But in the end the teacher may also have to set limits. If the work is late, there should be a penalty. You prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child.

There are caveats, of course. Sustaining strictness in the long run requires caring and warmth; students have to trust your intentions to do what is best for them even if they don’t always like each decision. And ideally they should feel the caring most in the moments you set limits. A reset on expectations is a good time to smile. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from studying teachers as a parent it is that if you said you’d give a consequence, you give the consequence, but you are also quick to tell the person you care about them and can’t wait for things to be back to normal; for example, You’ll have to serve your detention, Michael, but I look forward to seeing you back in class tomorrow. As Jo Facer puts it, “Having strict rules means you love children and want the best for them. Make sure you communicate that with your face and body language.”

Consider this interaction between Hasan Clayton and one of his students, a fifth grader whom I’ll call Kevin, after Hasan noticed Kevin sleeping during a remote lesson (in 2020, that is). After class Hasan asked Kevin to stay on the call after his classmates left.

Hasan: I noticed you were sleeping in class, Kevin.

Kevin: (Long pause. No answer.)

Hasan: Am I correct? Or am I wrong?

Kevin: You’re correct.

Hasan: Why were you sleeping in class?

Kevin: I don’t know. I thought I got a good sleep yesterday, but I still got tired.

Hasan: That’s not good. Do you know how much material you’re missing when you’re sleeping?

Kevin: Yes.

Hasan: Do you know how it makes me feel when you’re sleeping?

Kevin: It makes you feel sad.

Hasan: It makes me feel like you don’t think what we’re doing in class is important.

Kevin: So during independent practice today, what if I redo the lesson.

Hasan: Yes, I would appreciate you doing that, going back and answering all the questions and then turning it in. We have to think about how our actions are affecting ourselves and our community.

Kevin: OK.

Hasan: All right, Kevin, I hope to see you later. If not, I’ll see you tomorrow.

Some notes:

• Throughout the conversation Hasan never raised his voice or sounded angry. He also never sounded sweet or apologetic. I would describe him as composed. This is important. His goal was to cause Kevin to reflect on the cost of sleeping in class, not distract him with thoughts about whether Mr. Clayton was angry at him or induce defensiveness because he was being shouted at. Emotional Constancy was the order of the day.

• Hasan required that Kevin acknowledge the fact that he was sleeping. When Kevin didn’t respond to his initial statement I noticed you were sleeping in class, Hasan didn’t say anything for a full six or seven seconds! He refused to bail Kevin out by chattering through the awkward silence with “It’s OK. Everyone gets tired sometimes.” After the silence, Hasan persisted: “Am I correct or am I wrong?” He tacitly required Kevin to take ownership of his actions by acknowledging them.

• Once Kevin acknowledged his actions, Hasan’s tone lightened ever so slightly and he asked: Why were you sleeping? He was still reserved. There’s no baby talk—you could imagine a teacher using a Why were you so-o-o sleepy? approach here—but his tone reacts subtly to the degree to which Kevin owns the issue.

• When Kevin describes what’s wrong with sleeping in class, Hasan does not excuse the action. He explains the problem and pauses again. His economy of language is noticeable. Adding extraneous verbiage makes the interaction more casual, but Hasan wants formality here.

• Hasan focuses on depersonalizing the interaction and stressing Purpose Over Power rephrasing Kevin’s assertion that he might have made Hasan “sad” to focus on learning—It makes me feel like you don’t think what we’re doing in class is important.

• Kevin suggests a consequence and Hasan agrees to it. A lot of teachers might say, “That’s OK,” but Hasan accepts Kevin’s proposed consequence because the consequence will help Kevin remember and allow Kevin to make a gesture of resolution—this is an important step in resolution and closure. Hasan tells Kevin he appreciates his solution and then, a bit warmer, reminds him that he looks forward to seeing him back in class.

The post A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt: Warm/Strict appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 27, 2021

Notes on Memory and Pi (Which My Daughter is Memorizing)

My daughter is memorizing Pi. Apparently it started on a car ride over the weekend and for no particular reason. By the time I sat down next to her on the couch this morning she was up to 42 digits. When I left for work she was at 50.

We chatted about it a bit as she worked on it and this let me explain to her a bit more about what her brain was doing while she memorized- but it also prompted a few questions and observations of my own- giving me a few things to wonder about from a memory development POV.

She’s using an app where you key in the sequence and this struck me right away. It accelerated the process by allowing her to use constant low-stakes assessment more efficiently: self-quizzing, rather than just repeating and trying to remember. What’s the difference? She was getting instant feedback on every digit she keyed in and also was continually retrieving from Long Term Memory into working memory rather than trying to remember by attending deeply to what was already in working memory. Readers of books like Make it Stick will instantly recognize the difference.

Then I noticed how fast she was going through the initial digits in the sequence. Speed was part of her strategy and watching her I suddenly understood why. She’d get to 42 digits and then try to remember the next two or three. This information she’d have to try to hold in her working memory while she repeated the 42 digit sequence from the beginning. She was trying to go fast specifically to try to not think consciously about the parts she’d memorized and thus reduce the degree to which they entered her working memory. If they did she’d forget the new digits by the time she got to the end.

She was also ‘chunking’: that’s the name for linking pieces of information and remembering them as a single piece of information. I could basically see her ding this in the pace of her fingers as she typed the digits. At first 3.14159 is six digits and six pieces of information but after enough practice it’s a single piece of information- the first sequence. It’s name is threepointonefouronefivenine.

Chunking hacks working memory and allows us to use it to do (or perceive) more so it was obvious that she was chunking as she worked. I explained what chunking was to her and she instantly understood. “Yeah,” she said, her fingers racing through the digits. ‘That’s a chunk. And that’s a chunk,” she said after pieces of the sequence. She was aware of the sections she’d chunked and where she’d done her linking up. There were almost always sequences of 4 or 5 digits.

She also thought the physical movement of typing in the digits helped her. I think she was dual coding here- hacking the moments when her working memory was maxed out by supporting the abstract memory of the digits with the visual memory of where she moved next int he sequence. There’s some evidence that working memory limits are additive for visual and abstract information.

She also mentioned that she’d had to cast aside some mnemonic tools. At first there was a song she sang to remind her of the first few digits. This helped her to remember but after she’d gotten them really down she found it distracting. Basically, she now knew the digits better than the song she’d used to link them at first. That was kind of fascinating too.

Anyway, I have no purpose or lesson from this other than to share how i thin her brain was working as she memorized and why she was so successful at it. I mean she can’t remember to put her dishes in the sink when she’s done with them but by the time i get home from work she’ll probably be at 99 digits of Pi. And apparently this will not cause her to be any more or less likely to remember her chores. The capacity of long-term memory, most cognitive scientists apparently think, is unlimited.

The post Notes on Memory and Pi (Which My Daughter is Memorizing) appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 26, 2021

A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt: Joy Factor

Joy Factor is the last, but certainly not the least, technique in Teach Like a Champion. Like everything else in the book, I’ve rewritten it in the latest version and tried to make connections to what research tells us clearer and more direct. Here’s a snippet:

We often feel the greatest joy when we feel belonging. This perhaps is why singing, in particular choral singing, is part of practically every culture on earth and specifically a feature of worship in those cultures. When we sing together, we affirm that we all know the words, literally and metaphorically.

Done even briefly this can have a profound effect on us, which is especially worth remembering given that ours in the most individualistic society in the world. The wholeness and joy of belonging that our evolutionary self requires is something that our rational self is most likely to overlook or even scorn.

This is something we can unlock in the classroom. Watch the joy in the faces of Nicole Warren’s students as they start their class signing a math song they know by heart in Nicole Warren: Keystone. It involves many of the things we are socialized to dismiss: rote, ritual, memorized, familiar to the point of repetitive. And yet the students are ecstatically happy. Note that the gestures emphasize the belonging of the experience—people love to “know the moves,” and here knowing the moves is visible. Our own math song is even better than one lots of people know; we can voice in unison something other people don’t know about. Knowing things others don’t know or aren’t aware of is a key to belonging.

Music can be a source of joy even when it is not choral. It is unclear why, but every culture on earth sings and creates music. They use those things to define themselves. Some evolutionary biologists suggest that singing predated language as we know it—that before we had words we had music, which allowed us to express emotion and urgent information over distance. We sang ourselves into battle or into comfort afterwards, and this is wired into us. We have evolved with a proclivity for music, so we can assume it had evolutionary benefit in some way and that we evolved to take pleasure in it.

You can hear snippets of song throughout some of the videos in this book, such as Summer Payne in Cold Call singing, “individual tur-urns listen for your na-ame.” Christine Torres in Format Matters singing, “Don’t talk to the wall ‘cuz the wall don’t care.” And every time you use Call and Response you are in fact using a sort of simple chanting: together in one voice, you are saying, we all belong.

So singing, especially shared songs, can be a source of joy. But it can also remind us of how profound coordinated activity is to building a sense of belonging. Even sharing the experience together of hearing a text read aloud or reading a text aloud together as a group (see technique 24, FASE Reading), taking turns and bringing a whole to life through our efforts as individuals can awaken this feeling—the construction of a whole in which we subsume our individuality briefly and emerge gratified and infused with a sense of belonging and meaning.

Several pages back, I mentioned “flow” and this too is critical to understanding the difference between joy and fun: We like to lose ourselves in a challenging activity that sweeps us up in its momentum. We are often happiest when this happens. Any coach will tell you that one of the biggest teaching challenges in a sports setting is breaking the flow. You blow the whistle to talk about how the defense should be positioned and after a few seconds you start to see a gradual lurking frustration: We want to play, Coach; please stop talking so we can play. This reminds us that the core activity and its design are critical and that when they are well designed, joy is powerful because it is sprinkled in small moments—playful, silly, absurd, expressing belonging—that come and go quickly enough to augment and work in synergy with the sense of flow.

Consider: Christine Torres drops quick humorous comments into her lesson—the vocabulary word is “caustic”: the Turn and Talk asks students to engage an inside joke: “Imagine Ms. Torres is a contestant on American Idol; what’s a ‘caustic’ remark a judge might make about her singing?” Don’t be silly, she adds, he would never make a caustic remark about Ms. Torres’s epic singing. Maybe you see the belonging cues there: Ms. Torres’s talent as a singer is an ongoing motif, a sort of inside joke you would only ‘get’ if you were in her class. But also note the speed of it. It’s a quick laugh that preserves the sense of flow. The joy students feel comes as much from their engaged study of the vocabulary as it does from the joke. Christine’s humor sits off stage and comments amusingly on the main action; the lesson is still the star.

This, I think, is another reason why it’s important to differentiate joy from fun. We can play Jeopardy! to review during class today and that will be fun but, interestingly, it may not also be joyful unless we engineer it well so that it is designed for flow. We can all recall the “fun” activity we designed that sparked no joy because the flow wasn’t there or because the group dynamics didn’t work well. And while we’re at it, please recognize that the word “fun” can distract us. Most young people have fun when they play video games—though interestingly I am not sure they are joyful, perhaps because the degree of connection and belonging is missing. You can refer to “having fun” by itself but you don’t “have joy” by itself. You take joy or feel joy in doing something. “Joy” is clearer on purpose than “fun.” It has meaning and engagement.

The risk is that we forget that the fun is there to serve the learning. Happily it is not only possible to do both, but the goals are synergistic. People generally like learning things. So don’t play Jeopardy! unless it is rigorous enough to support learning, but also know that if it is challenging and engaging, joy will be more likely to arise from it.

Let me apply the conversation about flow and belonging to an additional source of classroom joy: humor is immensely beneficial to creating joy—we almost always smile when we laugh, and we often remember the joke forever (see the text note for an example). But small recurring inside jokes are especially powerful because of the way they maximize belonging and flow: Christine Torres joking about her excellent singing; a nickname for a character in history (one teacher called Orsino is Twelfth Night “wet wipe” because he was so spineless compared to the female leads in the play); or consider my high school history teacher, Mr. Gilhool, who was the master of the inside joke: he (and soon we) always referred to the city of “Amsterdarn” to civilize its “vulgar” name; he dramatized Count von Schlieffen on his deathbed advising Bismarck “to keep the West strong” and afterwards anytime anyone mentioned World War I military tactics, Gilhool would remind us of von Schlieffen’s words with a brief dramatization (except in cases where we remembered to do it first).

These jokes all happened in less than a second. That was part of the fun. Mr. Gilhool was also teaching with substance and pace while the inside jokes were coming at you fast, so you had to be paying attention or you’d miss the moment when he made a brief motion like he was weighing something on scales when he mentioned any philosopher’s name, which was why everyone around you was laughing. (See the next note for an explanation of why.) Part of what made Mr. Gilhool great was that we were learning a ton and part of it was getting the joke. These things were synergistic; so too the memory aspects. I still sometimes say “Amsterdarn” to this day and more importantly I still remember the Schlieffen Plan. Humor is powerful, especially when it is used in the service of learning via small recurring inside jokes.

The post A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt: Joy Factor appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 19, 2021

Quotes and Quotability: A Brief Notes on a Lost Idea

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseasedOn the reading front, I’m currently finishing Leo Damrosch’s The Club: Johnson, Boswell and the Friends Who Shaped and Age. It’s a group biography of Samuel Johnson, James Boswell and their circle, which included Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, Joshua Reynolds, Hester Thrale and David Garrick.

Damrosch’s description of Johnson’s death is both poignant and interesting. Johnson is surrounded by friends and knows he’s dying even though the doctors try to tell him otherwise. And so much of his communication is epigrammatic: couched in quotations from texts that Johnson knows well and knows his friends also know well.

A doctor comes to see Johnson and Johnson quotes from Macbeth:

Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased

Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow

Raze out the written troubles of the brain…

The lines are Macbeth’s- incongruously asking his own doctor to minister to his mind not his body when he (Macbeth) is being driven to madness and illness by guilt. Johnson, plagued by depression all his life, is alluding to his own psychological angst amidst (and contributing to?) an ailing body. He is referencing the ‘diseased’ mind’s inevitable downward pull on the body, his own sense of despair and the universality of this feeling (given that Shakespeare wrote about it and so many have thought about those famous lines). In other words being able to quote the play makes him able to evoke the scene and allude to far more than just the words say. It allows him to communicate in stories in a sense. Simply being able to communicate all of this gives Johnson comfort.

But the doctor goes one better. He replies in kind to Johnson using the words of the doctor replying to Macbeth in the play

“Therein,” he says, “the patient must minister to himself.”

He is affirming his understanding of Johnson’s plight and affirming the value of the things Johnson values even while he reminds him that the answer is no. Johnson, Boswell notes, “expressed himself much satisfied” with the doctor’s response.

The doctor by affirming his knowledge of the quotation says: we know the same stories, you and I, we speak the same language. And this is enough to both comfort and please Johnson and to affirm that they have communicated on an enriched basis.

Quotations served this purpose throughout the lives of citizens of the 18th century. To quote a text was to borrow wise words and allude to a context in a well-known story and affirm a connection among individuals: we have shared stories between us; this makes us kindred. They were profoundly important and people quoted to each other constantly.

Which of course we hardly ever do today–some younger folk do a version of this by quoting movie lines to one another, which I think serves many of the same purposes–and one reason we don’t is because we don’t know any quotes. The last thing on Earth most English teachers would do would be to ask students to memorize a few passages from the books they read. But oddly doing so would be profoundly powerful. The quotation evokes the context and the argument and brings the whole thing to life even if just in your inner dialogue. And from a student’s perspective there’s not much more powerful you can do in writing a paper than quote an author and allude to a scenes and context more broadly.

In our Reading Reconsidered English Curriculum we often insert a handful of key quotations in the Knowledge Organizer for exactly this reason. Knowing a memorable quote allows you to allude to the themes and ideas from a great book in a rich and tidy way–to yourself and to others.

Much like Johnson and his doctor.

The post Quotes and Quotability: A Brief Notes on a Lost Idea appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 18, 2021

On Cold Call and ‘Voice Equity,’ a TLAC 3.0 Excerpt

There are few things more inclusive you can do than to ask for someone’s opinion or input, especially when they do not yet know whether their voice is important in a room. To ask a student who has not volunteered, “What do you think?” is to tell them their voice matters.

There are few things more inclusive you can do than to ask for someone’s opinion or input, especially when they do not yet know whether their voice is important in a room. To ask a student who has not volunteered, “What do you think?” is to tell them their voice matters. As many readers know, the release of TLAC 3.0 has been delayed by a few weeks. As a result I’m going to spend much of August sharing useful pieces of the manuscript on line. This section is from the discussion of the purposes of Cold Calling, the first of which may surprise you.

In the previous section, I discussed principles for how to Cold Call, but it’s also important to know why you are Cold Calling so you can make adaptations accordingly. I can think of at least four purposes for the technique.

Purpose 1: Voice Equity

Let me begin by describing a recent Cold Call of my own, one you might not think of as a Cold Call at first but one that I hope will frame the conversation about it in a new light.

I have three children and at dinner recently the discussion was dominated by my two older children. Their voices were confident. Of course, we would want to know what happened to Aijah and Jane in math class or Nilaan and Derrin at soccer practice. My littlest sat quietly at the end of the table tracking the conversation with her eyes. Her brother and sister are five and seven years older, so perhaps she wondered: Were her stories from the day also relevant to the discussion? Would they meet with approval from her older siblings? When and how might she break in to try?

So I Cold Called her, turning to her at a tiny break in the discussion, and saying, “What about you, Goose? Are you still doing astronomy in science?”

She had not volunteered to join the conversation but I wanted her to know her voice mattered, and that her contributions were important. I wanted to show her the importance of her voice to the conversation. If she felt nervous, I wanted to break the ice for her.

There are few things more inclusive you can do than to ask for someone’s opinion or input, especially when they do not yet know whether their voice is important in a room. To ask a student who has not volunteered, “What do you think?” is to tell them their voice matters. This idea is called “voice equity” and I first began to use it after a conversation with some colleagues who trained teachers for the Peace Corps in sub-Saharan Africa.

In many parts of the countries where they worked, “Girls are not called on,” one of the team, Becky Banton, noted. There’s an unspoken gender norm and girls often do not speak up readily. Sometimes the norm comes from their families and sometimes despite their families. The expectation is transmitted invisibly, socially, mysteriously—but inexorably. “They sit quietly in the back of the room knowing the answers but not actively participating, not raising their hands, not going to the board,” Becky noted.

“When our teachers Cold Call, especially when they know a girl has a good idea by having circulated first and they say, ‘Come forward. Tell us your thinking,’ the girls answer and they succeed and you see it in their faces,” said Audrey Spencer. “It’s so fast. In the space of a single class. It builds their confidence and then we see an increase in their achievement.”

When there is a norm or an expectation that a student should not or cannot speak in class, be it societal (girls should be passive) or personal (there are three kids who volunteer; I am not one of them), the Cold Call breaks the norm for the student, absolving her of the responsibility for the violation of what is or appears to be a social code and perhaps even causing the student to see the code as a false construct.

Cold Call can remind a student that their voice matters and, often, that they are capable of participating credibly. In that sense it is a reminder that part of a teacher’s responsibility is to reinforce everyone’s right, legitimacy, and sometimes, just maybe, responsibility, to speak—for the sake of their own learning and to contribute to the classroom community.

In fact, a recent study suggests just how powerful Cold Call is in shaping students’ beliefs and expectations about their own participation. The study, by Elisa Dallimore and colleagues, tested the effect of Cold Call on voluntary participation by assessing what happened over time to students in classes where Cold Call was frequently used by the teacher as compared to classes in which it was not used.11 What they found was that “significantly more students answer questions voluntarily in classes with high cold-calling, and that the number of students voluntarily answering questions in high cold-calling classes increases over time.”

There is a double effect, in other words. Not only do more students participate in classes where the teacher Cold Calls because of the Cold Calls directly, but also because afterwards—perhaps because they experience success or perceive the norm of universal participation more strongly—they begin to participate more by choice. Further the effect the authors describe “also increases over time”: the more the Cold Calling becomes part of the fabric of class the more profoundly it causes students to choose to raise their hands. Finally, students’ affective response to class discussion changed. The authors found that students’ comfort in participating also increased. Being Cold Called didn’t cause stress; it caused comfort and confidence.

The post On Cold Call and ‘Voice Equity,’ a TLAC 3.0 Excerpt appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 16, 2021

On Culture and Belonging: An excerpt From the Preface to TLAC 3.0

Scene from a lesson in Denarius Frazier’s classroom. Note the students giving affirmative eye contact and positive nonverbal signals to the speaker. These tell her, We are listening; we respect your idea; it interests us; keep raising your hand.

Scene from a lesson in Denarius Frazier’s classroom. Note the students giving affirmative eye contact and positive nonverbal signals to the speaker. These tell her, We are listening; we respect your idea; it interests us; keep raising your hand.As many of you know, the release of TLAC 3.0 has been pushed back a few weeks. In the interim I’m going to try to share some useful pieces of the new version of the book here.

The book begins with an important new Preface that discusses some of the reasons and rationales for the techniques in the book, grounded in cognitive and social sciences and the larger discussion of equity and social justice in schools. In this section I discuss why I continue to think that nonverbal social cues among students–for example tracking the speaker–are so critical to the classrooms young people deserve.

Yet another field of study that has been influential to me in writing this book is Evolutionary Biology, the net on which is that the humans who won out in the struggle for evolution won by coordinating in groups and have evolved to be exceptionally responsive to what is required for inclusion in the group—it is of the highest importance from an evolutionary point of view.

We are creatures of culture first, supremely responsive to social norms, and every young person deserves to step into a classroom where social norms are as positive and constructive as possible.

Let me explain what I mean by describing a moment in the life of a student. We’ll call her Asha. She is sitting in Biology class and has just had an idea. It’s half developed—a notion still—but she wonders if she has thought of something that others have not. Maybe this is something smart. She’s a bit scared to share what she’s thinking. Her idea could be wrong or, just as bad, obvious already to everyone else. Maybe no one else cares much about DNA recombination and the fire it has suddenly lit in her mind. Maybe saying something earnest about DNA recombination makes you that kid—the one who raises her hand too often, who tries too hard, who breaks the social code. These sorts of thoughts have heretofore led her to adhere to a philosophy that counsels Keep it to yourself; don’t let anyone see your intellect; take no risks; fit in.

But somehow in this moment the desire to voice her thought overcomes her anxiety. She raises her hand and her teacher calls on her.

What happens next is critical to Asha’s future: Will her classmates seem like they care about her idea? Will she read interest in their faces? Will they nod and show their appreciation? Ask a follow-up question? Jot down a phrase in their notes?

Or will they be slouched in their chairs and turned away, checking their phones literally or metaphorically, their body language expressing their indifference? Oh, did you say something? Smirk. Will the next comment ignore her idea? Will there even be a next comment, or will her words drift away in a silence that tells her that no one cared enough to acknowledge or even look at her after she spoke?

These factors are Stations of the Cross in Asha’s journey. They will influence the relationship she perceives between herself and school and her aspirations. She is a vibrant soul, full of ideas she does not ordinarily share and wondering quietly if maybe someone like her could become a doctor. She doesn’t know anyone who’s done that, but she finds herself thinking about it sometimes.

Obviously, those dreams don’t all come down to this moment, but we would be foolish to dismiss its relevance. It could be the first tiny step on the path to medical school. Or it could be the last time she raises her hand all year.

Yes, it matters whether her teacher responds to her comment with encouragement—but perhaps not as much as what the social environment, the rest of Asha’s peers, communicate. If her teacher praises Asha’s comment amidst scorn and resounding silence from her peers, the benefit will be limited. The teacher’s capacity to shape norms in Asha’s classroom matters at least as much as her ability to connect individually with Asha. Relationships matter, but the social norms we create probably matter more.

That’s a hard thing to acknowledge. It removes us from the center of the story a little bit. But it’s a powerful thing to recognize as well. In many classrooms there is no model for what the social norms should communicate while Asha speaks or after she has spoken and her words hang in the air. Or perhaps there is a model, but it is mostly words—her teacher and maybe her school do not believe that what happens then is within their control.

Is it really their business whether students show an interest in what their classmates say? Imagine what a headache it would be to try to make that happen with hundreds of students, many of whom “just don’t care”? In the end, what happens in this moment and a thousand like it will most likely be an accident: lucky or unfortunate, supportive or destructive, with immense consequences for Asha and her classmates.

Something close to optimal culture, where Asha’s classmates are communicating with eye contact and body language: we are listening; we respect your idea; it interests us; keep raising your hand, does not occur naturally or by accident. It occurs when adults cause it to happen.

The post On Culture and Belonging: An excerpt From the Preface to TLAC 3.0 appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 15, 2021

Teach Like a Champion 3.0 Will Be Available September 14

Soon… I Promise…

Soon… I Promise…A few weeks ago I shared with readers that the new and dramatically improved Teach Like a Champion 3.0 would be out later in the summer, with early August the target date.

Since then, many of you have asked about its arrival and even pre-ordered copies, for which I am grateful.

It’s been hard work to make sure the new version is the best book it can be, and encouragement from readers has kept me going through much of the process!

Unfortunately, the last stages of the copyediting process revealed a handful of errors- enough that I could not reconcile myself to its release without further review. Along with the publishing team at John Wiley and Sons, I’ve made the difficult decision to delay the book so that when you finally have it in your hands, it is the best version it can be, worthy of your time and money and a book that serves you as a teacher for years to come.

So the bad news is that the new release date for Teach Like a Champion 3.0 is now September 14th. It’s important that you hear this from me and understand why. I know this is going to be disappointing for many of you, especially with school starting up before that date, but I have every reason to believe that the process will be smooth from here on out and you’ll have to book in your hand soon.

That said this decision is not without its silver linings. First, I’ll be using the Field Notes blog to share key excerpts of new and revised sections of the book in advance. I know how critical the weeks before school are for planning so I’m going to be sharing a lot in advance of September 14. Second, I’ll be sharing some additional videos and reflections that aren’t in the book to try to make up for the delay. So watch this space!

If you have pre-ordered version 3.0 already, thank you again for your support. I’m grateful for your faith in the book. You will likely receive a notice from the retailer you purchased from that there is a new date for the book, and they will ask if you would like to keep the order or cancel it. It is my sincere hope that you will keep your order- again this new edition is worth the little bit of an extra wait.

If you haven’t pre-ordered it, I hope you will consider doing so at your favorite retailer.

A bit more about what’s inside the 3.0 version. The book is dramatically revised to include:

Extensive discussions of research connecting the techniques more explicitly to cognitive and social sciences,Extensive discussions and reflections on the book’s place in classrooms and schools where diversity, equity, and inclusion are critical issues.A dozen new techniques (e.g Exemplar Planning, Retrieval Practice, Knowledge Organizers, Means of Participation)All of your standby technique, revise, refined, improved and sometimes renamed for clarity.More than a dozen “keystone” videos- longer running clips that show ten minutes or so of a teacher’s lesson, relatively uncut, so you can see how the techniques fit together and build a larger ethos of love and rigor.A full (new) chapter on Lesson Preparation and another of Mental Models.More than 100 new videos

So… thank you for everything you do on behalf of students and their families, especially now, in the midst of perhaps the hardest year for teachers (and students) in memory. I’m proud of how this version turned out and believe you will love it as well and that it will serve you well at the time students need us most.

Best,

Doug

The post Teach Like a Champion 3.0 Will Be Available September 14 appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 25, 2021

Our Recent SEL conversation with Wendy Amato and the Dean of Students Curriculum

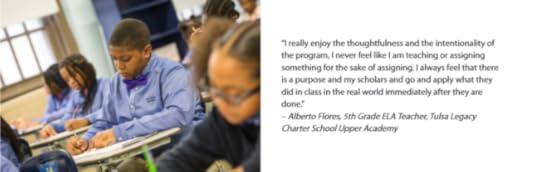

In our latest podcast interview with Wendy Amato from The Teaching Channel, Hilary Lewis and I discussed practical ideas about providing social emotional support to students and teachers alike as we head back to school. (Kudos to Wendy for raising the issue!)

Throughout the episode, you will hear us discuss what we hope are specific and actionable actions teachers can take to build connections with their students through content and classroom routines. Additionally, Hilary and I share a few lessons learned from this pandemic year as we prepare to return to the classroom.

You can listen to the podcast episode here: https://www.teachingchannel.com/blog/podcast-41?hs_preview=ivgEYGHa-48549856866.

During the discussion you;ll probably note that Hilary mentions Teach Like a Champion’s Dean of Students Curriculum. In January 2021, we launched this brand new tool, with support from the Kern Family Foundation, to help principals, teachers, and deans strengthen students’ character when they encounter challenging situations. In many ways, student lives and behaviors are unpredictable; however, the DOS Curriculum strives to make the unpredictable predictable by exploring common issues students may face in school and providing educators with resources to address those behaviors. For example it’s almost assured that we’ll have students who struggle with impulse control or who treat their classmates thoughtlessly at times. If we know those behaviors will occur, why not prepare for them with rich lesson plans that help them to reflect and learn more productively from the situations that occur in their lives?

To learn more about the DOS Curriculum please visit: https://teachlikeachampion.com/dean-of-students-curriculum/.

The post Our Recent SEL conversation with Wendy Amato and the Dean of Students Curriculum appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 9, 2021

Erica Woolway: Changes to Our New Online Workshops

Our team has been busy at work preparing our content for our upcoming workshops on Engaging Academics and Building Strong School Culture that kick off, via zoom, next week. Last year at this time, we were preparing to deliver our content for the first time remotely. After a year of leading training online we’ve been to discover that, while we’ll always prefer to be in-person, we are still able to create vibrant professional cultures online that leverage practice in breakout rooms. We’ve learned a ton about building engaging and rigorous PD culture online—and about the fact that we can help a wider range of schools when they don’t have to get on a plane and fly to Nashville or Charlotte for two full days to train with us.

This year, we are especially excited to share our updated content, reflecting our team’s updated learnings, captured in Teach Like a Champion 3.0 which will be coming out in the fall. We’ll be posting a series of blogs about this content, but in advance of our workshops next week, we’d like to share a few of these differences that you’ll see in the training.

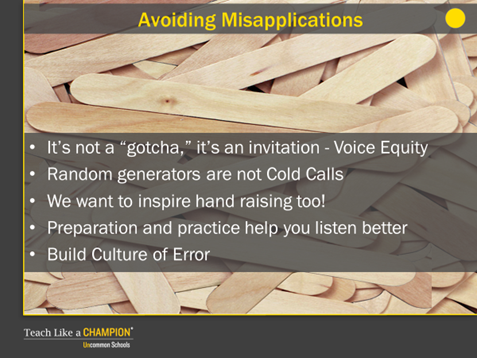

First, both in the new book and in our workshops, we are now much more explicit in calling out the risk of misapplication of the techniques. Here’s an example from Cold Call.

In the past we’ve consistently named that Cold Calling is not intended as a gotcha, but now we double down on the importance of using it positively. In the book and in our new set of workshops, to give another example, we explicitly describe that while using random generators like popsicle sticks can be quite useful at times, it is not to us an example of Cold Calling. It’s often beneficial to communicate intentionality to students. For example, to say: “David, what are you thinking?” tells David that you value his unique opinion and are thinking about his perspective at that moment. To use sticks is to say ‘Anyone can go next. It’s all about the same to me.’ The message of inclusiveness—your voice matters— and voice equity is not communicated by randomness.

We also clarify that while sometimes you may choose to intentionally use Hands Down Cold Calling, that one of the purposes of Cold Calling is actually to inspire hand raising, so if you only use Cold Call with hands down, you miss out on what of its greatest purposes which is in motivating to students to participate.

Importantly, Cold Call, like almost all of the techniques in Teach Like a Champion, benefit from teacher planning and preparation. An awkward and hesitant lead-in to the Cold Calling by the teacher makes students awkward and hesitant, and as a result, Cold Calling is therefore much less likely to build a positive and inclusive culture. Scripting your Cold Call questions in advance (or embedding your Means of Participation into your lesson plans) and briefly practicing a few times before class can help teachers to be more themselves when they use the technique. And of course when you’re thoroughly prepared, it frees your working memory and allows you to listen better to student responses.

A second important shift in our workshops and in 3.0, is the incorporation of cognitive and social science, and DEI research. Again, you’ll be seeing examples of this on our blog over the next few months, but here are examples of how these show up in our workshops:

In our discussion of Wait Time, we allude to Zaretta Hammond’s cognitive research that tells us “students need the cognitive time and space to process.”

And this slide around the importance of lesson preparation:

Throughout our workshops and in the new version of 3.0, there is an increased overall emphasis on lesson preparation which is also reflected in the research. We’ve even added a session in our Engaging Academics workshop that is dedicated to lesson preparation. While much of what Doug wrote about in the second edition focused on how to plan an effective lesson, 3.0 includes a chapter that “endeavors to shine a light on the methods my team and I have observed teachers use as they prepare to teach their lessons, instead…What’s the difference, you might ask, and why the change?”

Preparation is universal. Not everyone writes their own lesson plan every day. Many teachers use a plan written by a colleague or a curriculum provider. Some reuse a plan they wrote previously. But everyone prepares (or, I argue, should prepare) their lesson before they teach it. If a lesson plan is a sequence of activities you intend to use, lesson preparation is deciding how you will teach it. Those decisions can determine the lesson’s success at least as much as the sequence of activities it uses, but because planning and preparation are readily confused, it’s easy to overlook the latter and think once the plan’s done, you’re ready to roll.

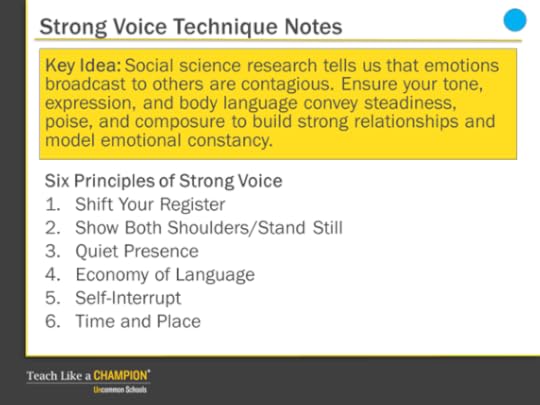

And finally, you’ll notice a shift in some of our language that reflects both the research and risk of misapplication. Here’s our updated notes on Strong Voice for example:

First, you’ll see how the Strong Voice technique is first and foremost embedded in the social science research and how the framing above is different from previous iterations of how we trained on the technique.

What you’ll hopefully also notice above is both what has stayed the same, and what has changed about the language in the techniques. Most notably, while Strong Voice is a critical technique for teachers to master, it is also one that is easily misunderstood, so we begin with some important notes on the purpose and even the name of the technique, which, we almost changed for 3.0, in part because “strong voice” has always been a bit of a misnomer. It is a technique as much about body language as about voice, for example. More importantly, the strength implied is in most cases about steadiness and self-control, about maintaining poise and composure, especially under duress. We describe the chain of reactions that begins with how people read our tone, expression, and body language is long and complex. Strong Voice helps you attend to signals communicated by such factors in your communication as a teacher and use them to increase the likelihood that students will react productively and positively to the things you ask of them. Aligning your tone, expression, and body language signals to the rest of our communication helps you to build stronger relationships, ensure productivity and, especially, avoid the sorts of showdowns that can spiral into negativity.

When we’re conversing, we’re not merely exchanging ideas, we’re often shaping the listener’s mindset and emotions. Researchers have found that emotions can spread between individuals even when their contact with each other is entirely nonverbal for example. In one study, three strangers were observed facing one another in silence. Researchers found that an emotionally expressive person transmitted his or her mood to the other two without uttering a word.

What we do with our voice, words, and body language can cause others to shift into modes of communication more like our own and this phenomenon has a name, “mirroring,” which refers to the way in which we unconsciously synchronize our emotional state to match that of another person’s during an interaction. One implication for teachers is that if we can keep our composure, or even noticeably recompose ourselves as things get tense, others are likely to follow. And of course if we lose our composure others are more likely to as well.

When we train on Strong Voice, our coaching often involves helping teachers avoid risk of misapplication and not to come on so “strong” with their Strong Voice—to be calmer and quieter, to appear self-assured, not loud. One potential reason people might try to be more forceful in tone and body language than necessary is the name itself: something called Strong Voice must be about being overpowering, right? Wrong. A composed teacher makes it more likely that students will maintain their composure, will focus on the message, and not be distracted by how it was delivered. Being more aware of your body language and tone of voice and keeping them purposeful, poised, and confident helps you and your students.

So while we toyed with the idea of renaming Strong Voice, we have kept it for continuity’s sake—and chosen instead to add framing to help make sure the purpose is clear. You will notice however, that the language of several of the sub-techniques has changed. Do Not Engage and Do Not Talk Over have been replaced with “Time and Place” and “Self-Interrupt” to better reflect our own guidance by giving clear directions about what to do, as opposed to what not to do. And Quiet Power has been replaced with “Quiet Presence” – better capturing what we mean about the importance of getting quieter and slower when you need students’ attention. Raising your voice will increase the sense of tension in the classroom, especially if you are speaking at a faster pace, too. So, developing your Quiet Presence is an important tool in helping maintain emotional constancy and therefore better build relationships and trust with your students.

So this is just a sampling of some of the changes that we are excited to share in our workshops next week. We have a few seats left if you’re able to join us remotely. If not, we hope to share this content again later this summer so that teachers and leaders feel prepared for the school year ahead. If you’re interested in our training your entire staff remotely in this content, you can also fill out a request form here. We also hope to be traveling soon, so in person trainings may also be an option in the months ahead!

–Erica Woolway

The post Erica Woolway: Changes to Our New Online Workshops appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 13, 2021

For Coaches: John Barnes Teaches a Group of Players How to Dribble

Some time a while ago, someone sent me a grainy cell phone video of England great John Barnes coaching an ad hoc group of young players in an improvised session. I don’t actually remember who sent it and why. At first it seems almost an accident- like Barnes was on vacation or something and got asked to “come and teach the boys something.” It has a very spur of the moment no-shirts and no-shoes feel to it.

But it’s also brilliant and so revealing. I am trying to think of a way not to call it a “master class” because I hate that phrase, but really it’s a bit of a master class.

Here it is:

What’s remarkable is Barnes’ assumption that learning to dribble starts not with a bunch of moves but with understanding the perceptive cues that tells you how to get past an opponent.

Most people start by gathering players and having them learn a bunch of moves–a step-over, a scissors, an inside cut–then players try to use them in the game. But they’re often unclear on how and when. The purpose, players think, is to use the move. Or to “fool” the opposition… but fooling the opposition is different from getting by them, quickly. The result is often seven touches when two will do. Barnes’ lesson starts with position: “If I want to go there…” this is how I get there.

The curriculum at John Barnes FC is not so much a gallery of moves but a series of signals to look at and read. He starts by training their eyes.

Perhaps that will require a scissors or a step-over, but it’s just as likely to result in players who can beat an opponent more simply and quickly. Like Barnes himself did. Which raises the question: How aware are most coaches of perceptive cues? How central are they to our teaching?

The post For Coaches: John Barnes Teaches a Group of Players How to Dribble appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers