Doug Lemov's Blog, page 21

October 15, 2020

Heather Pirolli Models an Online Show Call.

Show Call involves posting an example of a common student error…

Show Call involves posting an example of a common student error…

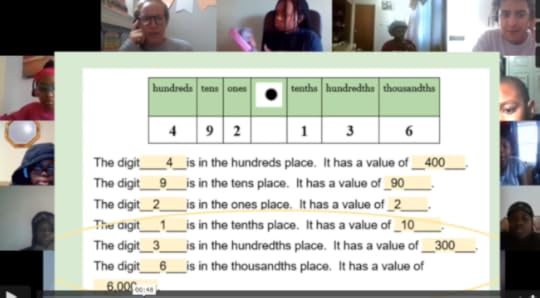

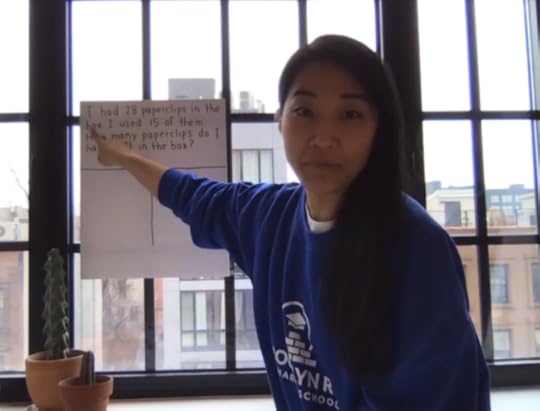

Show Call is one of our favorite classroom techniques on Team TLAC. It involves choosing a student’s work and projecting it to the class, whereupon it gets studied–lovingly but with rigor–especially if it includes a common error that everyone can learn from.

It’s a technique that translates well into an online setting, so I thought I’d share a really nice example. It comes from Heather Pirolli’s 5th grade ‘classroom’ at Uncommon’s Ocean Hill Collegiate.

Heather starts by projecting the common error to her students, making it clear that many of them struggled with the issue-if that included you, there’s no reason to worry or feel singled out. Her tone–warm, engaging and supportive–reinforces this. And she does a nice job of pointing out that much of the work is correct.

Then she asks students to type their analysis of the mistake into the Colab board. Crucially, everyone answers the critical question, what’s wrong here?, and Heather gets to see all the answers.

Heather does a great job of shining a light on an exemplary answer by one student, reading it to the class and celebrating it. (Great work, Jy!)

But she also notices that many students’ answers are vague or incorrect. So she continues checking for understanding by giving them a new example to try to answer: “Write in the value of the 6 in the tenth’s place….”

Here again, everyone does the work and she can see and evaluate their thinking. She chooses to Show Call again, sharing Catherine’s work, this time as an example of what correct work should look like.

The sequence ends with Belle’s perfect summary of what Catherine got right.

It’s a double Show Call and an example of exemplary Checking for Understanding that puts student work at the center of the classroom.

Side note: Heather uses Nearpod and Collaboration Board here but there’s no reason you couldn’t accomplish the same thing with simple screen share and chat.

Thanks to Heather and her kiddos for their great work!

The post Heather Pirolli Models an Online Show Call. appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

October 4, 2020

Cameras On: A Response to the Outrage

A week or so ago I posted a tweet that argued that having ‘cameras on’ should be the norm in classrooms. My point was that students need to be actively engaged in order to learn, and that people don’t participate fully and actively when their community is a series of blank screens representing people they can’t see. People don’t share something honest or vulnerable–“what happened to Jonas in this chapter made me angry”–to a group of people who are hidden to them.

My tweet recirculated widely a few days ago resulted in all sorts of outrage. There were some legit concerns and questions but there was also no shortage of people accusing me of wanting to police children, wanting to discriminate against the most vulnerable and believing that children shouldn’t be allowed to go to the bathroom etc.

So here is my response… an explanation of why ‘cameras on’ is so important. Ironically it’s all about building a loving and supportive culture that is equitable and inclusive, which I believe this will post will make clear to those who are are not deliberately seeking to distort what I am arguing.

I’m going to make the case in part with video of teachers who are doing outstanding work. I’m sure not everyone reading this will agree with what I write, and I know better than to expect civility in the replies. But please have the decency to not target your animus at these outstanding teachers who are working hard to do great things for kids and who have generously shared video their teaching. I shouldn’t have to say that. Sadly, I do.

A Clarification: When I say ‘cameras on’ should be the expectation I mean it has to be the expectation of teachers that they will foster as much of it as they can in their classrooms. I get that this is difficult. I understand that many districts prevent mandatory cameras-on. Fine. You can still socialize your students to do it. You can encourage them to turn their cameras on and remind them why it is important and follow up when they don’t. You can and should work hard at it, in other words. And of course this does not mean you should not make logical exceptions because, say, your connection has gone glitchy… or everyone’s suddenly has, or a student is taking care of a sibling at home or needs to use the bathroom or any of a thousand things. Of course you make logical and humane exceptions. The point is that community is very, very important in classrooms and deeply lacking for young people right now. Teachers should do everything in their power to build community so students feel like they are an important part of something and so they learn more. Cameras on is the single best way to foster those things

Context: That last point is deeply important. The percentages of kids who are NOT logging on and who are simply not going to school or are barely attending school are staggering. Every chance we get to make young people feel seen and necessary to the classroom is a step towards bringing them into the fold. It’s important to understand that online learning is a terrible facsimile of the real thing. It’s awful to have to say that because everyone is working so hard to make it work, but the early data suggest that learning losses are massive and that they are magnified for less privileged students. This is a national catastrophe unfolding. Kids aren’t just not learning. Often they’re not even present. as Alec MacGillis described in the New Yorker there are a lot of reasons why … many kids can’t get to class online… but many kids come and don’t persist. They fade away because they feel invisible and distant and disconnected. And these issues are exacerbated by financial hardship. As a top official at LAUSD pointed out, many families “may lack the ability to provide full-time support at home for online learning, which is necessary for very young learners.” There are a lot of parents forced to go off to work and leave their kids to do the best they can at school-from-home everyday without an adult present. And even with one there, it’s easy to disengage. So when you tell me your culture is ‘great’ in your classroom with students you can’t see, I ask you about the kids most likely to drop off the fringes of the screen. The most marginal and at-risk kids. Is it great for them? You sure?

Example: Here’s a video of a teacher named Shelby starting class.

My God what a gift to be in a class like this. Students are greeted by name and feel seen and important and loved—one is called “birthday girl.” Seeing them enables Shelby to do that. She notes to one student that she sees him holding up all his materials with pride. They feel connected to her. She sends them love and they send it back. Belonging is a powerful thing and Shelby does this by making them know they are seen: literally and figuratively. But Shelby is also setting them up for success. Making sure every student has the things they need to be successful at the outset. Cameras help with that too. Regardless of whether there’s an adult nearby to make sure they’ve got everything they need, they’ve got Shelby to help them along. Yes, there are a couple of kids in Shelby’s class who don’t have cameras on- internet issues? Something going on at home? Sure. But the expectation is ‘cameras on’ unless there’s some reason otherwise. And the result is a collective belonging. Community, inclusion and support for kids to make sure they’re successful.

Another Example: Now here’s video of a teacher named Denise starting class.

It shows you more ways ‘cameras on’ can make a profound difference. Like Shelby, Denise greets her students warmly. You can greet a blank screen too, I suppose, but you can’t smile at it as she does and say nice to see you and say something nice about your t shirt etc. You can’t really make someone feel seen and relevant unless you can actually see them. Then she lovingly asks for cameras on. It helps her to teach and connect and build community. There are ways to ask that are loving as Denise and Shelby prove. You just have to be willing to imagine them. Denise’s lesson is dynamic and draws students in with its momentum. Part of that is because kids understand her procedures. Being able to see them helps her do that: “thumbs up if you understand” is one example. But she can also see them working and see whether they look engaged. Without cameras on, this loving, positive and productive class doesn’t happen.

Did it require work and persistence for teachers like Shelby and Denise to get those cameras on? Yes. But thank God they did it.

More Context: There’s an immense amount of data out there on how we engage online. [I’m not going to cite it here but start with Cal Newport Deep Work if you want to know more.] Our attention is immediately degraded when we’re online. We are more prone to distraction and more distraction is available. (You can see how easily distracted some of Shelby’s kiddos are; they need her to steer them towards focus). This is a bad combination even for adults: the great majority of our online interactions are done in a state of partial attention. Think for a moment of yourself and the meetings in which you turn off your own screen. Why do you do it? Because other people are doing it, which suggests that if they didn’t you wouldn’t either, and because it’s ok to, but also because you want to be free to send a few emails and take care of some other tasks and get up and walk away from your computer and generally be less attentive and accountable. In a few cases there are other reasons—child care—but these are the most common. Your students are no different. They would prefer not to have cameras on. It would be nice to only partially engage and be only partially accountable. Suffice it to say their parents probably feel otherwise. I’ll return to that in a moment.

Another Example: In the meantime here’s Eric’s classroom.

He sends his kids off to read for ten mins on their own out of a real book—One Crazy Summer, one of my favorites–God bless him. Before he does that he can tell his students are deeply engaged he can SEE how his students are bought in. They are listening. They are entranced. They have the book out. They are ready. They are ready because he is holding them lovingly accountable for being focused on the book. And they can see each other doing this on their screen. Each student looking at another student holding a book says: everyone is focused on reading. Independent, self-paced work like this is a gift to students but we also should realize that when we assign it, distraction is only a click away. Through the camera, Eric builds a loving safety net. He tells students how much he appreciates them working hard. Tacitly they know he’s noticing whether they stay engaged. His doing so is warm and loving: Mostly he’s telling them how much he appreciates their focus and efforts. They feel seen and important and they are socialized to remain engaged, to resist the temptation to click away. The temptations for distraction online are engineered by some of the smartest people in society to addict young minds to compulsive clicking. He would be a fool to give away one of his best tools to fight back on their behalf: his ability to narrate positive effort. He can tell them that he sees and appreciates them when they work hard because he can see them. This causes them to work hard. It’s accountability sure but it’s loving benevolent purposeful accountability. That’s what teachers do.

Quick digression. Accepting that we have authority is our responsibility as teachers. Parents transfer their authority to us and that authority is not authoritarianism. Authority is what parents have entrusted us with. To do what’s best for their children even if it’s challenging and even when their students are not initially inclined to do it. Many of them have migrated here at great danger to themselves from places where opportunity is scarce or rule of law does not reliably exist in order to give their children a better chance. Many of them are working multiple jobs or thankless and exhausting jobs or multiple thankless and exhausting jobs to try to give their children a chance to follow their dream. They give their authority to us to cause their children to do what is most beneficial for them and their chances rather than what is easy. They are counting on us being like Eric.

Final Example: So far I’ve shown you examples of how critical ‘cameras on’ is to building inclusive classrooms and attentive classrooms. But there’s more. Here’s Susie.

Her kids are reading the Jungle by Upton Sinclair. It’s a very difficult book and she needs to know if her students understand it. She Cold Calls one young man—you can’t ask a question simply and easily of someone you can’t see and whom you don’t even know is sitting at their desk… the awkward wait and unclear outcome—is he there??—kills momentum and reminds students that at lot of people are barely listening. The question, importantly, reveals confusion about the text and ‘cameras on’ has made it a lot easier for her to find out. Next, she knows to call on Angel because she can see he has raised his hand. He knows the answer. But also he’s only raising his hand because he perceives himself to be part of a community. He responds directly to Darius because he can see Darius listening back to him. He sees his present classmates and knows he can talk to them comfortably. Their faces looking back at him show they care about what he’s saying. After the reveal—thanks to Angel!– she sees the class’s surprise. This lets her adapt her teaching. She sends them to a breakout room to talk to each other. The peer to peer interaction—kids talking to kids about a book—happens because she can see them and they can see each other: imagine dropping a kid into a breakout room with a blank screen.

‘Cameras on’ is not only a critical tool for making kids feel included and important. It empowers you to understand how they are progressing in their learning. To see them struggle or progress happily or reluctantly. It lets you ‘read’ their responses and tech better as a result. Cameras on allows you to make things move along with energy and pace so classes are interesting and engaging.

Look, I know it’s hard. And I know we often can’t mandate cameras on. But we sure can ask for it like Denise and Shelby to. And then make kids feel the difference like Susie and Eric do. And when kids don’t want to turn on their cameras you can message them and say “is everything ok? I notice your camera’s not on” and if they say “I just don’t feel like it,” you say, “well I’d really like to see you today” and if she says “I’m home alone and taking care of my baby brother” you say “Of course I understand. I love you for being so helpful and can we check after class so I can make sure you didn’t miss anything?”

If You See This As Policing: To the people tweeted to say that encouraging cameras is a means of policing kids and part of some larger effort to ‘control’ them: If the primary thing that comes to mind for you when you imagine teachers and kids seeing each other is ‘policing’; if your first thought is not of course cameras on will let us understand our students, smile at them, see their learning journey, and let us lovingly ensure they are on task and on their way to success, but rather oh the teachers probably have adversarial relationships with their students; they probably won’t try to use this tool to do foster positive interactions then you have lost the plot. If the primary action you conceptualize when teachers can see and interact with their students is coercion, in other words, the problem has nothing to do with cameras and a lot to do with how you conceive of relationships.

Finally re: the frequently suggested idea that we can’t ask kids to turn their cameras on (and therefore help them learn more) because some will be embarrassed by their surroundings- I think this assumption deserves questioning. Why would we assume that people are embarrassed by their home because they are not wealthy? Most people, regardless of their economic status, take pride in their dwelling. It is theirs and simple or complex, they have put expressions of themselves within it. Honestly, it bothers me that people suggest there is something people of lesser means have to be embarrassed about, that not having money is something to be embarrassed about. To start with that conception is problematic.

In the few cases where the home setting poses problems—a kid sitting in a hallways outside his apartment comes to mind… kids from Muslim families where turning on the camera means all the females in the house have to cover up–let’s start with the assumption that families can solve those problems. They have agency and insight and wisdom. Most likely they can find a way to position their camera or use a background that addresses the problem. If not you can devise a solution for your students directly or in consultation with parents or caregivers.

One of the hardest things about teaching is that it asks us, requires us, to do difficult things. And sometimes when smart people are asked to do difficult things that they are not sure they can accomplish the temptation is to rationalize why they shouldn’t do that difficult thing at all… why that difficult but important thing is actually not a good thing at all but a bad thing. This is easier than taking the risk of struggling to do what‘s right.

It’s a very hard time to be a teacher but it’s a much harder time to be a student. Or it’s a hard time to be successful as a student. Many, many students will lose opportunities and suffer lifelong consequences because adults have allowed them or enabled them to do what feels easy in the short run. Of course you won’t be able to get every camera on. Some days you may get none. But your kids deserve what happens when you do so you owe it to them to try.

The post Cameras On: A Response to the Outrage appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 30, 2020

Online Turn & Talk with Ben Esser

Thinking about breakout rooms as Turn & Talks helps us leverage their long and happy history in our classrooms

…

Thinking about breakout rooms as Turn & Talks helps us leverage their long and happy history in our classrooms

…

Turn & Talk is a key tool for building Participation Ratio in a bricks and mortar classroom. It’s not too different online where the use of breakout rooms allows us to replicate it with decent fidelity.

Even though it involves the use of breakout rooms we still call the technique Turn & Talk because we think it’s helpful to use the same terminology as we use in physical classrooms. Doing so helps create continuity for students–it reminds them that the activity is highly analogous to something they know well–and reminds us to use what we know about it from physical classrooms in our online lessons.

This short video of Achievement First East New York MS’s always thoughtful and impressive Ben Esser:

A couple of things we love:

It’s quick. Turn and Talks give students the opportunity to test and rehearse ideas before a fuller discussion, but (we think) they should be a preliminary to a subsequent activity since they include lots of good ideas and probably a fair number of erroneous ones. If we know they are preliminary we want to ride what we call the “crest of the wave“: we want students to come out of them still eager to talk as opposed to having tapped out all their ideas and ready to move on. “Five minutes in breakout rooms”? Uh, probably not.

Ben “manages turns.” One risk of Turn and Talks is that verbal kids talk and quiet kids don’t. Giving students a rule for who goes first makes it more likely that quieter kids will get their chance as well. It also makes it easier for students to start their conversations quickly and thus get more value out of the Turn and Talk.

Ben’s students wrote about the question before they talked about it. (You can hear this in Brandon’s answer where he is partially talking extemporaneously and partially reading his answer). This ensures that they have lots to say during the Turn and Talk.

Ben takes volunteers after the Turn and Talk rather than Cold Call. Cold Call is also great but given all the time he’s given students to prep their ideas it’s a good time to bet on volunteers. Notice how many hands he gets. And notice how critical “cameras on” is to his being able to see them.

We love the way he calls on Saraya to “build” on Brandon’s answer. Ben is stressing those critical “Habits of Discussion” that remind students that listening as important as speaking.

Ben, thank you as always for sharing your classroom.

The post Online Turn & Talk with Ben Esser appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 29, 2020

The ‘Chat’ Chronicles: Shelby Daley & Mika Salazar Make Students Feel Seen…and so Appreciated

Wait till you see what Shelby and Mika do with this…

Wait till you see what Shelby and Mika do with this…

“The Chat” is one of the key tools available to teachers in online… and one of the best tools for building dynamic, active and inclusive learning environments. You might even call it a ‘silver lining’: a small thing that works better online even if the, overall context of online learning is not nearly as good as a real classroom. Using the chat involves asking students to respond to a question in whatever meeting platform you are using. It’s primary benefits are its speed, visibility and simplicity. Students can write without having to open a new window or toggle to a new place so they can be writing withing seconds and you can bring pace and energy to your classes. And students can see that their peers are writing, which reinforces for them the normalcy, even the universality of active participation.

So: A great chat allows you to build participation ratio and to surface ideas worth developing. We say “surface” because it tends not to illicit writing of depth and permanence. It’s a starter that leads to some other activity.

So what does a great chat look like? I’m happy to share two super examples.

First, check out Shelby Daley, a 6th grade English teacher at Uncommon Schools’ Ocean Hill Collegiate:

Shelby is trying to surface ideas in anticipation of a further activity (reading) and to build and value active participation and deep thinking.

Her tone is lovely; so sincere and engaged: “Can you drop your answer in the chat? I’m really curious to see what you’re thinking cause this is so different from how we celebrate birthdays in our community,” she says. “So inviting of student ideas” is how one colleague described her style.

Interestingly she doesn’t resolve the question (yet). The goal is to surface ideas and value reflection and participation so she merely shares a series of students thoughts read lovingly from the chat while telling them (and showing) how interesting she thinks they are.

Cleverly she cuts off the chat after letting students weigh in. This allows her to copy and paste it right then and there so she’ll know later s who actually participated and can follow up with anyone who didn’t, but she’s also thinking about focus and attention. “Scholars love the chat feature so I close it during direct instruction to ensure they are focused,” she told us. She doesn’t want them to love the chat so much that they’re talking to one another all lesson long.

Finally, Shelby transitions from the chat directly into reading and a bit of pencil to paper reflection. This is wonderful. Pencil-to-paper writing is still important, even online, and it’s great opportunity for kids to get to use writing in that format to develop their thoughts privately.

Now here’s her colleague Mika Salazar, a 7th grade science teacher. She’s using the chat for retrieval practice (hooray!) to make sure that students are learning gets encoded in long term memory.

We loved the playful way she made the activity feel fun and like a game show by having students get their fingers ready on the key board. Great narrate the positive to make sure they with her too, by the way.

Similar sunny, upbeat, and engaging tone as to what we saw in Shelby’s room. She narrates the chat back to students too, showing them that she appreciates every answer even when the first question is easy and everyone gets it.

The second question takes it up a notch. First cold calling students to read the question is a great way to make sure they stay engaged, focused and involved. She breaks her question apart into four shorter answers so it feels faster and more lively. Again as soon as students engage actively they can feel the appreciation coming from Mika: “I see those fingers typing. Thank you, Dillon, Thank you Naomi. Excellent Shalimar…”

Then she stretches them a bit. When they all get that A is the crest of the wave she asks them to chat again: “What’s another word I could use for crest.”

We’re two minutes into class and already sailing, the lesson dynamic and engaging and everyone feeling important to the flow of the lesson

Great stuff, Shelby and Mika …. and thanks to you both for sharing

The post The ‘Chat’ Chronicles: Shelby Daley & Mika Salazar Make Students Feel Seen…and so Appreciated appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 28, 2020

How Jena Staley and Kevin Mooney use ‘Linked Sheets’ In their Online Classrooms

Great things afoot in Hagerstown

Great things afoot in HagerstownThere are three primary ways students can be asked to write in an online classroom. They can use the chat function in whatever meeting platform you use, they can write pencil to paper wherever they are sitting–what we call Everybody Writes–or they can write in a ‘linked sheet‘–a google doc, say–that they toggle over to; this can be shared–everyone using the same document–or individual–one per kid.

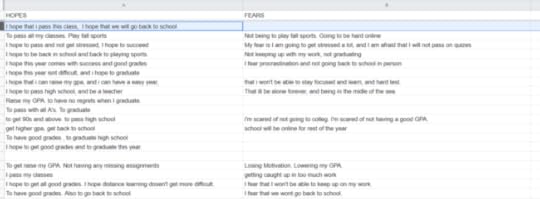

In a later post I’ll reflect a bit more on some benefits and limitations for these three ways students can be asked to write but today I’m going to share examples of the third type of writing, linked sheets, that two colleagues in at North Hagerstown High School in Maryland, Jena Staley and Kevin Mooney, have been using in their AP Stats classes. They’ve been using shared linked sheets where the whole class participates in the same place and have done a really nice job of modeling different design decisions. Here are three examples.

EXAMPLE #1:

Jena and Kevin used this sheet on the first day of class to build culture, which is to say normalize participation and establish a bit of openness and psychological safety so everyone feels safe sharing. They asked students to share their responses to a really simple question that everyone could answer–share one hope and one fear for the class. But cleverly, they privately assigned each student a row so that they students knew where to answer and they–the teachers–knew who was who, but thoughts appeared anonymously to their peers. Feels fair for the first day–the goal after all is to make participation feel positive and normal.

Here’s what that looked like:

I asked Jena and Kevin a few questions afterwards:

How did the kids respond? The students were forthcoming, open and respectful.

Did anything surprise you? Yes. There were many more responses than are normally generated when we do this in the classroom as a chalk talk on the white board. The responses were just as open and honest as they normally are. We also have the benefit of having a record of what each student said, which we wouldn’t if this were a chalk talk.

Any other applications you see for anonymizing? Yes. This would be a great way to determine student questions or confusion about a concept or upcoming assessment. Anytime when you think you get false negatives – because the kids would be afraid to share with their peers.

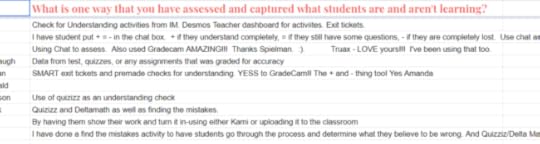

Example #2:

Later, they asked students to answer a question during classwork that was designed to assess whether students could determine the correct Alternative Hypothesis from a given a Null Hypothesis- and perhaps reveal a bit more about their errors. A google sheet was a really efficient tool. As you can see I’ve trimmed the names for privacy purposes but students in this case identified themselves as they answered.

“It’s such a paradigm shift as to how we are used to getting, seeing and analyzing student responses,” Jena and Kevin observed. “Even if we go through and grade all the “Column B”‘s first – we can’t keep them all in our working memory. This is an extremely easy way to see where all your kids are on everything at almost a glance.”

Example #3:

Finally as with so many good things in the classroom Kevin and Jena applied them in a meeting with colleagues and the adults too found sharing their thoughts in writing on a shared sheet useful. You can see them commenting on and appreciating one another’s ideas.

Thanks a ton to Jena and Kevin for sharing their work!

The post How Jena Staley and Kevin Mooney use ‘Linked Sheets’ In their Online Classrooms appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 21, 2020

Dan Willingham’s Workarounds for Online Teaching: Some Video Examples

There’s gotta be a workaround…

There’s gotta be a workaround…The Cognitive Psychologist Daniel Willingham had a useful Op-Ed in the LA Times last week in which he discussed the ways that online learning is cognitively strange (my phrase; blame me if you don’t like it)–that is, it asks us to interact socially in ways we aren’t used to and haven’t evolved for and that are therefore less productive and more fatiguing. Eye tracking is a good example. We’ve evolved to track other people’s eyes during conversation to see what they’re looking at. When they’re out of sync in time–glitchy internet–or spatially–you’re looking at me on the screen but I am to the left of your camera so it looks like you’re not actually looking at me–it feels unnatural and these are probably some of the reasons we find interacting via video conference fatiguing.

Willingham also offers a few useful fixes for the difficulties of online learning and as I read, I thought: “Hey, I’ve got an example of that!”

I thought I’d share some here.

“Gestures aid student comprehension,” Willingham writes, “but they’re usually absent from videoconferencing. Teachers sit near the computer to control their keyboard and mouse, which means students only see their faces.” This is a basic but profound observation. On the TLAC team we noticed this as well and realized how much of the communication potential of a teacher is cut off when he or she becomes merely a ‘talking head” because we saw this amazing video of Rachel Shin.

It was the first time we’d seen a teacher get up from her table/desk, move away from the camera and stand up to teach online.

From an engagement stand point the result is breathtaking, especially if you are a first grader. Not only are the tools available for communication expanded but the setting, to a student, suddenly echoes typical human interaction. The student sees and hear things that look and sound like the classroom they know: the teacher is standing at the anchor chart sing-song-ing the phrase ‘underline my un-its‘… and suddenly it all feels reassuring.

Rachel, standing, gesturing, a person not a merely a face

Rachel, standing, gesturing, a person not a merely a faceIn the picture above Rachel is gesturing and that, according to Willingham, is a big deal. But gestures are tricky online, especially when we can’t do as Rachel is doing here… after all the reason we tend to not stand up is because it’s often impractical.

But Willingham observes, “Overcoming these obstacles is usually possible. If I can’t point with my finger, I’ll point “verbally”: If I want students to look at a large, blue section of a graph, I can say, “Look at the big blue section.”” Devising such ‘workarounds,’ Willingham notes, is becomes more and more important the longer we spend on screen.

Reading that I was reminded of this video of Joshua Humphrey teaching. He does a great job of guiding students eyes through a review of a Do Now (at about 1:00 in the video) and of a section of notes he calls a reference sheet (at about 2:30). He’s pointing graphically, using colored highlights to direct students to focus on the most important information and making the presentation more lively by tacitly suggesting that the key area of focus is always changing. He’s “pointing with graphics” Willingham might say.

The post Dan Willingham’s Workarounds for Online Teaching: Some Video Examples appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 18, 2020

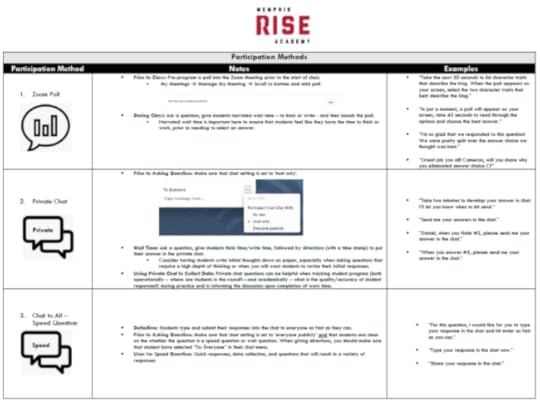

How Memphis Rise Helps Teachers Build Vibrant Online Culture

Simple little things of value

Simple little things of valueMeans of Participation is our phrase for a set of consistent procedures that describe clearly to students HOW they should participate in class at any given moment.

When the Means of Participation is ambiguous–i.e. left unclear by the teacher–the results are mostly one of the following:

Crickets: No one will violate the unspoken code of silence so there’s a long awkward silence

That Kid: The one highly verbal kid who always answers will answer yet again to save everyone the awkwardness or because he or she has a habit of calling out.

When you don’t make it clear how to participate–when you haven’t thought through the ideal way for students to participate–you get students’ best guess about how to participate, or the lowest risk option. And sometimes very little participation at all.

What you don’t get is ‘voice equity’- the opportunity for everyone to be heard. If you get the same kid voicing his answers over and over right away, kids who are slower and possibly more thoughtful never get to speak.

What you also don’t get is an culture that is designed to optimally support learning and intellectual risk-taking, that makes everyone feel lovingly accountable.

When it’s clear how to participate, when those means of participation vary, when they draw everyone in to participation, and when the Turn and Talks and Cold Call become familiar and known routines, they “can help reinforce academic mindsets such as “I belong” and “I can do this,”” as Zaretta Hammond writes in Culturally Responsive Teaching.

This is true in Bricks and Mortar classrooms. It is true times 100 in Online classrooms where the Norm of Passivity is STRONG. Even adults will turn off the cameras and fade into the isolating reaches of the internet if allowed to. Vibrant classroom culture has to be built online. If we do it we get community. If we don’t we get isolation.

The first step to vibrant online culture, then, is defining the Means of Participation you will use and sharing details on execution. What are the options and how can teachers do them well?

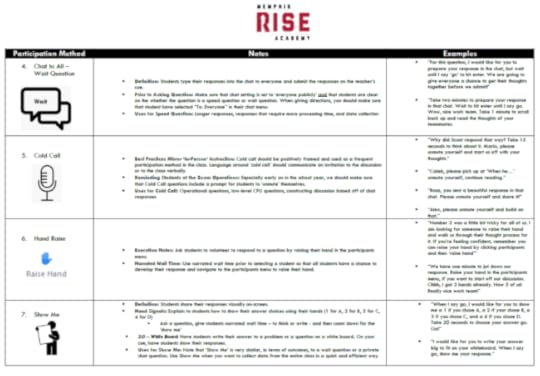

That’s why this excellent document from Memphis Rise Academy in Memphis, TN is so valuable. The school–working with my partner and colleague Darryl Williams–has defined the Means of Participation its teachers can use, named them, outlined details of how to do them well. They’ve even included model phrases teachers can employ in using them:

But they’ve gone a step further too. The icons on the left get used by teachers in their materials–lesson plans and slide decks if they use them–to remind themselves of which method they’ve planned to use when.

We–Team TLAC–do this in our own workshops. These little icons for example remind me that on this slide I’m asking participants to chat and then I’m Cold Calling someone whose ideas I appreciated from the chat.

With this visible reminder i have more working memory free to really listen to people.

If i keep at it i hope my sessions will be as good as some of the amazing classes I’ve seen at Memphis Rise.

The post How Memphis Rise Helps Teachers Build Vibrant Online Culture appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 3, 2020

Reading Online with Stephanie Le

I wanted to share this great little video of Stephanie Le’s classroom at Libertas College Prep in Los Angeles. She does a good job of maintaining a dynamic pace to her lesson while keeping students engaged and on their toes through a variety of forms of participation.

The video starts out with her reading aloud with her class. This is an important thing to do in an online classroom- it allows Stephanie to bring the book to life so students are engaged in subsequent discussions and so they can hear what the prose should sound like when they read sections on their own. Notice her really lovely expressive reading and the way she punches words like “torn” to give them extra emphasis. hared discussion of it.

Coming upon the mention of a minor character (but one who will prove important later) she pauses to make sure students are straight on who he is by asking them to answer in the chat. She validates students who got the answer–“MJ, Manuel, you’re right but does anyone remember what happened to Jerry?” This both shows that she values their participation and also pushes them to “stretch it” a bit.

“MJ” gets rewarded with a cold call–“Go ahead and share…”– but still Stephanie wants more detail–“but why though, Guadelupe?” Another Cold Call… the Cold Calling here really enables her to keep the pacing swift. She wants to engage kids and reinforce this key point but not spend too much time on a minor topic.

Stephanie then reinforces that Jerry will become important later and they pick up again with the reading, in this case by asking a student to read.

All in all a great job of keeping high energy and fast pace but also making sure her kiddos are locked in.

The post Reading Online with Stephanie Le appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Sharing Keila Fernandez’ Orientation Screen for First Graders

Easy to be prepared when you’re a first grader!

Easy to be prepared when you’re a first grader!

How should an online lesson begin? Generally with a warm and gracious greeting and a teacher’s smiling face. Students should feel seen and cared about. They should see their teacher’s face and also be seen.

Then we should get down to learning. And the first step in that is often making sure students have everything they need to be prepared.

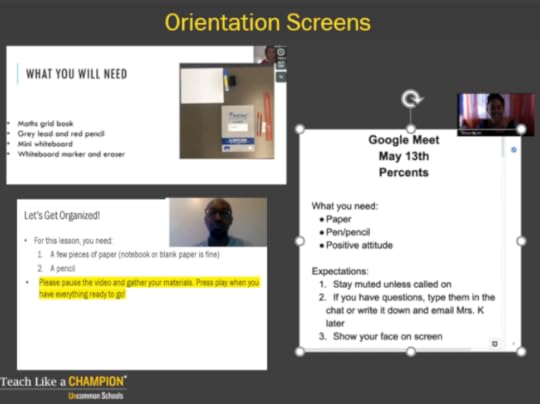

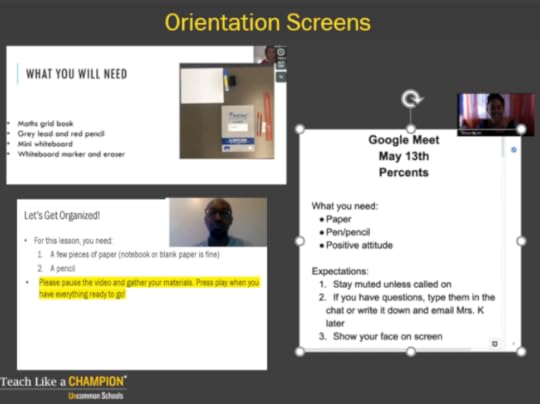

An “Orientation Screen” is a great way to do that; it lets students know what they’ll need to have ready to engage in the lesson it sets them up for success. It takes the key first steps in preparation and makes them both visual and verbal so they are easier for students to follow.

Here are some examples:

Alonzo Hall’s, on the lower left, is a particular favorite. He tells students to pause the video to make sure they have everything ready. But he also establishes that key directions will be highlighted in yellow. If it’s in yellow it’s crucial; if i need to find what’s most important i should scan for the yellow.

But what does an “Orientation Screen” look like when students are little and can’t reliably read the level of text such a screen requires?

This video of Keila Hernandez beginning a math lesson with her first graders at Uncommon’s Ocean Hill Elementary School in Brooklyn provides some answers:

Notice her Orientation Screen is all pictures and no words. Nicely spaced. Simple and easy to follow. Brightly colored but with no extraneous or distracting information. Most first graders could self-manage getting their materials ready based on this screen.

Notice also that there’s a tracker they’ll be using. Keila has sent it in advnace and she’s planned it carefully. That the primary work of the session is paper to pencil is important too. Students remember far more when they read and write in ‘hard copy.’ Looking down at work on paper is a great break from the screen.

Keila’s pacing is also great. She’s efficient but she doesn’t rush.

We also like the simplicity of her images all the way through…. we want an image to have all the right information but nothing extraneous to distract students and take up working memory.

Ideally after this clip students would also get to see her smiling face again through as much of the lesson as possible. That might be one thing to add if you steal some of Keila’s great work.

The post Sharing Keila Fernandez’ Orientation Screen for First Graders appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Sharing Keila Hernandez’ Orientation Screen for First Graders

Easy to be prepared when you’re a first grader!

Easy to be prepared when you’re a first grader!

How should an online lesson begin? Generally with a warm and gracious greeting and a teacher’s smiling face. Students should feel seen and cared about. They should see their teacher’s face and also be seen.

Then we should get down to learning. And the first step in that is often making sure students have everything they need to be prepared.

An “Orientation Screen” is a great way to do that; it lets students know what they’ll need to have ready to engage in the lesson it sets them up for success. It takes the key first steps in preparation and makes them both visual and verbal so they are easier for students to follow.

Here are some examples:

Alonzo Hall’s, on the lower left, is a particular favorite. He tells students to pause the video to make sure they have everything ready. But he also establishes that key directions will be highlighted in yellow. If it’s in yellow it’s crucial; if i need to find what’s most important i should scan for the yellow.

But what does an “Orientation Screen” look like when students are little and can’t reliably read the level of text such a screen requires?

This video of Keila Hernandez beginning a math lesson with her first graders at Uncommon’s Ocean Hill Elementary School in Brooklyn provides some answers:

Notice her Orientation Screen is all pictures and no words. Nicely spaced. Simple and easy to follow. Brightly colored but with no extraneous or distracting information. Most first graders could self-manage getting their materials ready based on this screen.

Notice also that there’s a tracker they’ll be using. Keila has sent it in advnace and she’s planned it carefully. That the primary work of the session is paper to pencil is important too. Students remember far more when they read and write in ‘hard copy.’ Looking down at work on paper is a great break from the screen.

Keila’s pacing is also great. She’s efficient but she doesn’t rush.

We also like the simplicity of her images all the way through…. we want an image to have all the right information but nothing extraneous to distract students and take up working memory.

Ideally after this clip students would also get to see her smiling face again through as much of the lesson as possible. That might be one thing to add if you steal some of Keila’s great work.

The post Sharing Keila Hernandez’ Orientation Screen for First Graders appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers