Doug Lemov's Blog, page 23

July 31, 2020

Denise Karratti’s Online Classroom: Great Systems, Great Culture

We expect to be inspired by Hawaii but this is serious….

We expect to be inspired by Hawaii but this is serious….We’ve been working with Hawaii DOE and a group of ace teaches there to develop good models of online teaching and yesterday I got to see some of the early footage. It’s pretty fantastic and I wanted to share a few exceptional moments from Denise Karratti’s 6th grade math lesson at Chiefess Kamakahelei Middle School.

In particular I’d like to highlight a few of her systems (i.e. consistent procedures familiar to all students) which are fantastic and which help her to build a great classroom culture–even online.

As the clip opens, Denise is teaching a synchronous session with her kiddos. (We can’t see them, unfortunately but as you’ll see they’re there).

She wants them to reflect in writing on a question that requires some thought: How are fractions and percents related? She doesn’t want students to race to answer and, because she is Checking for Understanding, doesn’t want kids who know right away to give the answer away too readily for kids who might struggle.

So she uses a “Wait Question”: a question where they write their answers in the chat but don’t share until she tells them. This allows her to slow them down.

[Aside: This is also a great example of one of our rules of thumb for online learning: Give students something active to do within the first 3 minutes so the message this will be active learning! is clear.]

What’s even better about her use of the Wait Question though is that you can see some key steps in the process for how she establishes a system like this where kids reliably know how to do a “Wait Question.”

She’s clearly explained it already but she offers a reminder of the expectation in the most gracious of ways. If you weren’t here last week I’ll just remind you that a Wait Question is where I ask you a question and you’re going to start typing your answer in the chat BUT…. you’re not going to press send until I tell you to… Perfect what to do directions, warmly offered. Her goal here is to make sure every student gets the system right so she doesn’t expect her installation to happen in just one iteration. You can see her warm loving persistence.She also gives the why, so students understand why she has this system: “That way everyone can write down their ideas without seeing other people’s ideas yet, and then we’ll take a look.”Asking thumbs up if you understand is a great little detail to add. It reconnects the attention and accountability loop and reinforces the biggest ‘system’ of all: the understanding that we are always attentive and will be constantly interacting.Then she sets a minute for them to write. They don’t have to rush. In fact, this signals to them the level of depth she expects. If she didn’t make the wait time transparent here they might write quickly for fear she’d say “press send” in just a few seconds. By specifying that they get a full minute, she makes it much more likely they will slow down and think.Her warmth and excitement are so palpable when she says, “Go ahead and press enter. Let’s see it!” Who wouldn’t want to do their best work?She also explains how to do the second part of the system–look at and listen to other people’s ideas. You don’t just sit idly, “While we’re doing that go ahead and see everybody’s [ideas] popping up. Check out what they wrote. See if you have the same idea as anybody. Maybe you have new ideas that you didn’t think about.“Then she calls out some things that students wrote to show she reads them carefully and cares. Now they’re even more vested in following through on chat writes.

Now here’s a second clip from her session where she’s using the technique “Show Me” from TLAC to Check for Understanding online. They convert a fraction to decimal and hold their answer up to their camera where Denise then scans the answers to assess where the class is.

You could do this with paper or with whiteboard and we love it because it’s such a simple and familiar system…. ‘tech light’… she’s chosen the simplest tools to allow her to assess, and even better, it gets kids writing pen to paper (or board)–a nice break from all that screen-based work and they are likely to remember better what they write versus what they type.

As with the previous clip, she’s always attentive to reinforcing the procedure. “Raffi a little closer; and to your right..”

There’s such appreciation for all the kids who do the work and she’s also reinforcing how carefully she looks.

And in fact, maybe that’s one of our biggest takeaways. Because Denise’s procedures work so well and so seamlessly she can spend her time building culture: reinforcing kids for their effort and hard work and showing them how much she cares.

Denise: Thanks for sharing with us. What amazing work!

The post Denise Karratti’s Online Classroom: Great Systems, Great Culture appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 30, 2020

‘Semi-synchronous-ness’ is our new favorite thing

Sometimes “sort of synchronous” is best…

Sometimes “sort of synchronous” is best…I’ve been writing a lot here lately about the synergies between synchronous and asynchronous lessons- about how they balance each other out and how a good lesson could actually be a hybrid, moving back and forth between synchronous and asynchronous activities…. it needn’t be one or the other.

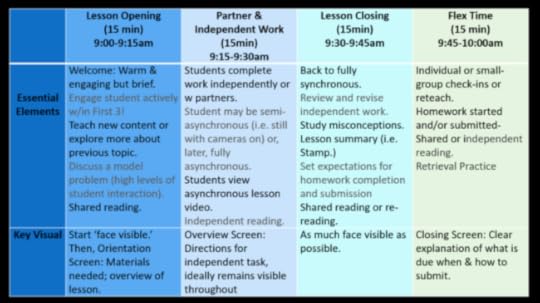

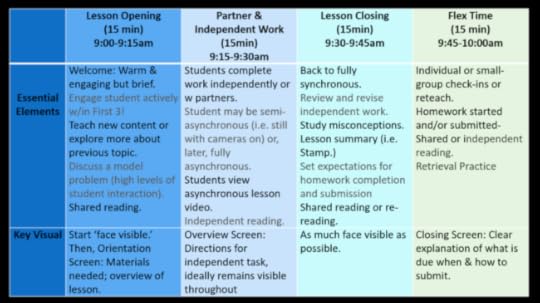

After Darryl Williams put together an amazing lesson template,

I started watching footage of teachers transitioning from synchronous Lesson Openings to asynchronous Independent Work…

And then suddenly I realized that I was wrong. That what we were looking at when teachers did independent work online was not actually a transition from synchronous to asynchronous teaching but from synchronous to semi-synchronous teaching, where students did work on their own but with ‘cameras on’ and a sort of passive safety net in place. What was working so well was in fact a third category all together,

I put together a video with two examples of what I’d call semi-synchronous lesson activities:

Eric Snider and Knikki Hernandez are the two teachers. Both lessons start synchronously and then transition to block of time where students are working on their own and but Eric and Knikki are still passively present to offer support benign accountability… they help students to maintain their task concentration and that can answer questions if needed.

Some similarities:

Both Eric and Knikki give students a specific amount of time to work on a task for. Both teachers ask students if they need more time. Attending to time is critical. Too short and the task doesn’t get completed. Too long and student attention fades.

Both teaches then bring students back from the independent work and review immediately.

The tasks require students to use paper and pencil (or to read a book) in other words they are not looking at a screen. This is hugely important. Massive doses of screen time are hard on the brain. These moments offer refreshing breaks.

Both teachers use the transition out of synchronous teaching to ensure that students understand the task. Eric posts the directions on his screen so students can refer to it throughout while they work. Knikki very deliberately checks for understanding of the task–what are we doing? where are we writing? She asks via Cold Call. It is the only time she uses English.

Students… no, people.. are inherently more distracted and distractable online. “Learning to concentrate is an essential but ever more difficult challenge in a culture where distraction is omnipresent,” writes Maryanne Wolf. Both teachers here are socializing sustained periods of work that reinforce strong attention and they are able to hold students lovingly accountable for maintaining that attention.

The post ‘Semi-synchronous-ness’ is our new favorite thing appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 28, 2020

Darryl Williams’ Framework for Online Lessons

My colleague Darryl Williams leads our partnership work, where we work directly with schools to help them achieve their vision of high-quality equitable instruction in every classroom.

Because he spends so much time working directly with schools as they implement, he’s often the first to propose solutions to emerging challenges, and with COVID-mandated online learning on everyone’s mind, his recent work with a group of our schools is no exception.

Darryl put together a draft framework for what the structure of online lessons could look like across a school. He was building off one of our observations that the biggest challenge of both synchronous and asynchronous instruction is the same: fatigue, tuning out, exhaustion. We know students need face-to-face interactions. But even for adults, hours of Zoom time can be brutal. And asynchronous learning can also be exhausting and isolating. Thus the framework: a fairly brilliant bit of distillation on his part of how to balance the two types of instruction to make online learning both productive and sustainable.

First here’s an overview of what he proposed:

I should note that the idea is that this model is not a mandate…. it would be adapted differently by each school and probably routinely adapted by teachers. But it sets a general structure that’s productive and sustainable and brings some necessary predictability and consistency to what teaching could look like.

In the Lesson Opening, students and teacher are present synchronously. We want a lot of interaction so students feel connected and included and accountable. They should see a smiling face and be asked to do something active–respond to a question in the zoom chat, say–within the first three minutes. And there should be an ‘orientation screen’ near to the beginning so students know what’s coming, and what materials they need to participate. And, as I discussed here, they should be able to see that things are planned and time is important. You might imagine a fusion of these two openings… The way Knikki gets started right away and involves everybody. How both she and Sean have a great Opening Screen with materials needed and activities described… And maybe you could mix in some of Sean’s humor and connected-ness (even though his video is asynchronous):

After ten or fifteen minutes of all of us together, connected and accountable, then maybe it’s time for some independent work. We love the idea of it being ‘semi-asynchronous’… that is, with cameras still on so you can support and check in with kids as Eric does, brilliantly, here. (Notice how seen and supported his kids feel even though they’re reading independently. And notice that the directions are up on his screen the whole time in case they forget.) Over time this could be fully asynchronous.

After a bit of independent work maybe it’s time to come back to a synchronous setting to check for understanding, process the independent work, and make sure students were productive on their own. That might look at bit like this clip of Ben Esser’s lesson, which again is highly interactive… there’s a great writing prompt that everyone completes. There are loving Cold Calls. There are breakout rooms (and Ben drops in to one to see how it’s going) etc.:

Then maybe the lesson shifts again to what we call Flex Time… students get some or all of their homework done. There’s time for you to check in with individuals or small groups who need more support. Darryl notes it’s a great time to offer targeted support for students who require accommodations or special education services… and the fact that the time is relatively predictable makes it easier for them to provide support. Kids might get to do a little reading. But you’d also want to be really clear: what work is due when? Submitted how?

When Darryl shared this I just thought it was tremendously useful as a tool to manage and sustain attention and focus, to balance formats in a relatively predictable way to get the most out of online lessons. Hope it’s helpful to you as well.

The post Darryl Williams’ Framework for Online Lessons appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 27, 2020

An Excerpt from The Coach’s Guide to Teaching, Chapter 5: Building Culture

The Coach’s Guide to Teaching, my book for sports coaches on developing athletes through better teaching, hits the shelves this winter. Meanwhile I’m trying to get the manuscript buttoned up. I’ve shared examples from some of the other chapters here, here and here. This excerpt is from the beginning of the chapter on Building Culture which features a deep dive into some of the magic of Jesse Marsch’s systems to connect his teams and build a strong mindset. You won’t get to read that part here, alas but maybe I’ll share that next…

Getting closer to reality…

Getting closer to reality…Several years ago I observed Chris Apple training a group of boys at Empire United’s Development Academy in Rochester, NY. Chris is also men’s soccer coach at University of Rochester. I’ve learned a lot from him in a variety of settings over the years, but that particular session was especially memorable. He saw and taught the hidden sides of the game more than almost any coach I’d observed. His guidance and his stoppages were almost always about what was happening away from the ball, for example. And, when I asked him why he’d chosen to work on pressing during so much of the session, he replied with a phrase I’ve thought about frequently since: “The great majority of coaches spend the great majority of their time on the offensive side of the ball.” His coaching focused what players did in the moments away from the spotlight. Compared to that, what they did with the ball was easy.

Fittingly, then, what turned out to be the most significant takeaway from the session was also away-from-the-spotlight. It was an interaction I noticed almost by chance and jotted in my notebook as an after-thought. I didn’t ask Chris anything about it at the time.

And then, a few years later, I was asked an unexpected question during a workshop for the US Soccer Academy Directors course. A coach wanted to know how he could help players to forget more effectively- to put mistakes behind them and focus on the next moment. The question caused me to remember that moment from Chris’ training and a few days later I asked him about it. His answer revealed a great deal about culture—arguably the single most important aspect in determining a club’s outcomes on the field and in players’ lives.

Here’s

the interaction I’d seen at that practice: After technical work and a series of

exercises on pressing, Chris’ session ends with a chance for the boys to play,

full-field and relatively uninterrupted. The quality of play reflects the

culture of Chris’ team more broadly: intense and competitive. In the waning

minutes of practice, the game is deadlocked, and you can feel the tension.

And then suddenly there’s a clear chance for one of the strikers. He finds himself in the center of the box, with a bit of space and the ball arriving at his feet. No one but the keeper to beat; it’s a sitter. His first touch is perfect; two defenders lunge desperately to close but it’s hopeless. He leans into the shot and … fires four feet over the bar. A bad, bad miss, and infuriating to most coaches.

But Chris, on the sideline shouts nothing, says nothing. The sound of the ball slamming against the wall echoes inside the training facility. The player jogs slowly back, head down and a teammate jogs nearer. “Next play, kid. Get it back,” he says.

In

retrospect I’m not sure why I bothered to describe that in my notes. I suspect

I was stuck by the contrast between Chris’ response and the counter-productive

things I had heard so many coaches yell in similar situations:

“Caleb, you

gotta make that!” [Pretty sure Caleb knows that, coach.] “Aw, get over

the ball, Caleb!” [True, though it doesn’t help much now, unfortunately] Or, turning

to the players on the bench in exasperation: “What is he doing?”

Coaches make statements like that in response to player errors in part to protect their own ego, suggests Stu Singer, a consultant who works with coaches to develop their mindfulness and self-discipline. “The statement lets everybody know: I taught him better. It’s about protecting the self instead of responding to the athlete.”

Chris didn’t remember the specific play when I described it to him but there had been a hundred like it since. So many that Chris had a working theory on what to communicate in such moments.

“He

knows he missed and me pointing it out adds insult to injury,” he said. “It’s

the last play of a scrimmage he really wanted to win; he’s upset, angry, maybe

feeling he let his team down, maybe trying to break into the starting 11 and

feels he just blew it. He’ll be thinking about that play the entire car

ride home. If anything, I could have told him to shake it off or remind him of

the three he scored that day.”

I’m

careful about the term mindfulness. It means a

lot of things to a lot of different people, with varying degrees of rigor, but

the versions of the idea I am drawn to involve intentional decisions about what

to pay attention to, particularly in moments of distraction and emotion, and

Chris’ response strikes me as being especially mindful. He was able to see

past his own emotional response and focus on the player, the long-term goal and

most of all the culture of the team. What does he need now? What will

make him better? What do I want the rest of the team to think about his

mistake and what it will mean to make a similar one? “You have to respond

versus react,” Singer advises. “Emotion is ok. But the question for a coach is

always: did you choose it, or did it choose you?”

Culture

is built in a thousand smaller moments when we’re not fully aware that we’re

building it. The aggregate message of those moments is at least as influential as

the moments when we are aware that we are building culture: talks before

or after games or before the season when we discuss how as a team we want to

interact and what our mindset should be. Those aren’t irrelevant. But culture

really is the thousand unacknowledged half second interactions in which our

response communicates mindset and relationship. For Chris it was:

when you make a mistake I will stand by you; therefore play fearlessly and embrace accountability

rather

than

when you make a mistake I will seek to establish blame; therefore play self-consciously and be ready to point the finger at others.

The difference between responding and reacting is worth some consideration. Much of athletic performance, as I discussed in chapter one, is about honing the brain’s fast systems so we can react in the fractions of a second before we can engage conscious thought. Coaching, by contrast, is often about slowing down, about giving ourselves just a fraction of a second in which to respond intentionally. Reaction is instantaneous. Response is slower-often only by a fraction of a second though sometimes by an hour or a day—and lets the brain’s more advanced centers of planning and logic—the prefrontal cortex—take precedence over its instinctual ones—the amygdala. Even a second’s delay can allow a coach to think about the larger context in which athletes play- culture, in other words.

Chris’

response was memorable because he had chosen not to say anything. He gave the

player a bit of space. Over time Chris had found himself thinking about the

importance of the things he should not say. This also communicated culture. Saying

less gave players more space and autonomy and ownership. If he commented on

everything his players did, they would never learn to judge for themselves. In fact they would hear him more when it

mattered if he chose more carefully when to speak. He would earn their trust

and appreciation if he do not seek to judge every action.

It had not always been that way. “Early in my career, I was abysmal at this,” Chris noted. “I’m not sure I was even conscious of it. I coached everything. Imagine your boss was looking over your shoulder and correcting every error. Not fun, not sure how much I’d learn, pretty sure how resentful I’d become.” Learning to coach for Chris had been learning to be intentional about when to remain silent, to let the story play out, to focus, in the drama of the moment, on long-term relationships. Over the years Chris had given a name to this idea: Coaching by not coaching.

* * *

Culture, the topic of this chapter, has been written about extensively in a thousand settings. In part because culture is so powerful. “Culture eats strategy for lunch,” the management guru Peter Drucker said. Want to run a successful organization? Take everything you do and “multiply by culture,” says Harvard Business School professor Frances Frei.

“Group

culture is one of the most powerful forces on the planet,” writes Daniel Coyle

in The Culture Code. The introduction to his book is called ‘when two

plus two equals ten,’ an allusion to the idea that a team that inspires people

to give their all, causes them to work together, and brings out their best,

will win out over one that lacks cohesion and unity, often even if it has a better

game plan or superior talent. You can get a lot wrong if you get culture right.

It’s

interesting to note how strongly we are drawn to the idea that culture is the

ultimate source of strength, and that cohesion and unity will beat talent. We

desire above all things for that to be true. How many movies can you think of

that tell the story of underdogs who manage to come together and triumph through

camaraderie, collaboration, and self-sacrifice? In those tales the opposition

are never another group of cast offs who manage to build a positive shared culture.

They are always more favored by life: usually demonstrated by their being enormously

large and having nicer uniforms and snobby attitudes. Count, by contrast, the

number of movies about the under-matched group who win because they prepare

better, study hard, and learn to to understand the subtleties of the game. They

like each other well enough mostly but they generally keep to themselves. Still

their knowledge is deep and profound, and, in the end, they win because of

their abiding respect for the game. Not one movie tells that tale. The story we

want to be told again and again is the story of culture triumphant.

It’s almost as if some deep truth has been demonstrated in the triumph of the group over superior talent based on “chemistry” and principles of shared culture. And no wonder. Humankind’s triumph as a species is, as Hollywood might describe it, the story of a bunch of underdogs who must learn to work together despite their differences. In learning to value the group as much as themselves, they win out over fangs and claws and other superior evolutionary talent. The opposition in the story of evolution is not teams called the Lions, the Tigers and the Bears, it really is lions and tigers and bears- superior species in their physical attributes whom we out-competed by understanding the nuances of working together. The triumph of culture is the story of our species, but it’s not a simple one.

It’s

worth hearing how an evolutionary scientist describes it. The sociobiologist

Edward Wilson describes the success of humans as being the result of two parallel forms of natural selection,

one that rewarded strength and intelligence among individuals and another that

rewarded coordination and cooperation among groups,. “The strategies of the

game were written as a complicated mix of closely calibrated altruism,

cooperation, competition, domination, reciprocity, defection and deceit… Thus

was born the human condition: selfish at one time, selfless at another, the two

impulses often in conflict.” A weaker

individual in a stronger group might be more likely to survive through the eons

of prehistory than would a stronger individual in a weak group, in other words,

but everyone was always noticing that the best case of all was to be the strong

individual within a strong group and this creates a constant tension. The

desires and needs we have evolved for as individuals conflict with the needs of

the group we have also evolve to pursue. We are all of us jockeying for

position within the group even as we want to ensure that it remains empowering.

Individuals come together to form groups that are greater than the sum of their

parts, but not easily. The natural state, Wilson is telling us, is one of

tension created by deep seated and conflicted instincts. Building culture is

the story of how we reconcile that tension as we seek to achieve things.

The post An Excerpt from The Coach’s Guide to Teaching, Chapter 5: Building Culture appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 24, 2020

Thoughts on Teaching Methods and Schedules Online

It’s all about the blend, friends…

It’s all about the blend, friends…A colleague who’s in charge of a large district wrote me recently to ask about scheduling teacher and student time this fall with her district most likely going online.

At first I almost said, “Honestly, I just don’t know.”

Because really I don’t. I don’t run schools directly and therefore don’t have to weigh all the factors or make the hard calls. It’s important to recognize when you don’t know enough to advise.

But as I was about to hit send on the email I realized that there’s a related topic I’ve been thinking quite a bit about that’s relevant to scheduling decisions, and while I’m cautious about sharing it with people much closer than me to a difficult problem, how teachers teach informs what scheduling options a school can consider and what decisions are optimal. So perhaps it’s relevant.

First I’ve been thinking for some time about pacing and time allocation … how brutal a day full of zoom calls is even for adults for example, and what a ten year old looks like stumbling out of 4 straight hours on Zoom. But then again how necessary face to face contact is to learning … and how beneficial routines and consistency are. Those things are hard to marry. And there are other factors like how fatiguing it can be to be working alone without contact on assignments communicated via an increasingly blurry stream of asynchronous videos.

In our workshops we often start by listing the benefits and limitations of synchronous and asynchronous instruction. ‘Fatigue” is on the list of limitations for both. A steady stream of either can be grueling. There’s plenty of research on how fatiguing online interactions are.

The good news is that my team have increasingly been observing synergies between synchronous and asynchronous learning environments that just maybe can help address the challenges of pacing, timing and attention that can limit scheduling options. For example, most people (I think) view synchronous/asynchronous as an either/or choice for a lesson but we’ve been watching a lot of video of what I would describe as hybrids…

Let’s say it’s a math lesson. It’s scheduled from 9-9:50AM. At 9 the teacher might come on and do a ten minute synchronous mini-lesson, working hard to involve every student and achieve full active engagement through everybody writes, zoom chats, and cold calls while she explains the concept—let’s say it’s adding fractions w unlike denominators—and they complete model problem or two together. Then maybe the teacher says. “Ok, here are a few more problems to work on your own… you have 15 minutes to work on them.” But perhaps she adds “Keep your cameras on so you can chat me with questions and I can see how you’re doing while you’re working.”

This allows for a change of pace. Students are looking down at their paper instead of staring at a screen. They can self-pace—the fast moving fast and the more deliberate moving slower. But again there’s that scaffold of support. Maybe later in the year kids can sign off entirely to do the problem set but for now they are semi-asynchronous… Sort of like what Eric Snider does in this clip. He can warmly and gently hold them accountable to sustain focus and provide support to those who need it. As they work he says, “I see you working Elisa. I see you working Juwaun.” Students are seen and appreciated for doing the work and can reach out to Eric if they struggle. And of course he can check in to see how much time they need. And he keeps the assignment visible on his screen in case they forget. Knikki Hernandez does something similar here: 3-plus minutes of camera-on independent work in the middle of a synchronous lesson.

Maybe 15 minutes later

the lesson ends with the teacher bringing students back together for ten mins

of synchronous review and five minutes to start your homework.

Perhaps over time this middle section—the semi-asynchronous one–becomes an ‘office hours’ model, especially with older students. Class is scheduled for an hour. We are together for ten mins of it at the beginning and also maybe at the end but in the middle you work on your own and can even sign off the call while the teacher remains avaiable for “office hours” where those who need help or have questions can opt back in (or be asked to opt back in) to a smaller as-needed zoom call. The hour might end with the class coming back together for a brief recap or it might just end with students turning in what they’ve done via email at 9:50. A mix in the pacing and modes on engagement keeps it a bit more refreshing.

Anyway I think a regular daily time for classes probably makes sense—things work best when they’re consistent. Math is 9-9:50 everyday. But teachers should not think that means they should use the full time for live (or taped!) lessons every day. Doing that would be death by zoom for even the most committed student. Sometimes it might be all independent work done asynchronously except that it’s due at 10am via email so students are accountable for working during that time. They have to vary the setting and context not only between lessons but within them while also assuring gentle loving accountability.

In the end, then, options for how a schools structures time become viable based on how teachers use that time…ideally when they use a blend of synchronous and asynchronous structures in the same lesson.

The post Thoughts on Teaching Methods and Schedules Online appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 15, 2020

Tips for Online Show Call from Jeff Li’s Lesson

After a bit of a hiatus for other projects, my team and I are back to studying video of teachers working online this week.

Yesterday we watched video of Jeff Li, who’s an outstanding math teacher at KIPP in NYC and who has been a guest blogger here before.

Jeff was teaching as part of the National Summer School Initiative, which is attempting to address the crisis created by the disruptions in instruction created by schools being closed due to pandemic. NSSI hired some of the best teachers in the country to be mentor teachers. They videotaped these mentor teachers leading a daily with a small group of their own students. The videos are intend to serve as models to guide and support other teachers who were teaching the same content in hundreds of other schools during the summer. They’re a treasure chest of great teaching and I’ll definitely be sharing lots of examples.

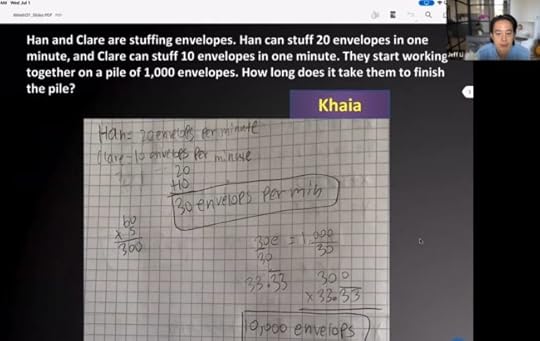

Anyway we were really struck by some things Jeff did with Show Calling.

The first thing we noticed was something simple but brilliant about the design of his materials: Jeff Show Called by using a slide on which he had superimposed the question and the answer onto the same slide. (!!) This allowed students to see both question and answer clearly at the same time (and to continuously refresh their working memory of both) without having to toggle back and forth. This freed up working memory so that students could focus all of their thinking on analyzing the math: a tiny change but a huge one in help students focus their working memory on what’s important.

Here’s what it looked like

Honestly, I’m tempted to end this post right here. It’s such a profound but useful design decision. If that’s all you get from this post, I’m happy. But Jeff’s teaching deserves a bit more discussion so I will go on…

The next thing we noticed was that Jeff built his lesson around Show Call. Students had completed a problem the night before. Jeff started the lesson by showing one student’s response. “Take a moment to remind yourself of the problem and then have a look at Khaia’s work,” he said.

One of Jeff’s students in responding to Khaia’s work disagreed with what she’d done. “I think she’s wrong,” he said, observing that her answer–33.33 minutes–was wrong because it the time had to be expressed in whole minutes, which is not correct.

Jeff did two things really nicely in response. First he managed his tell and withheld the answer. That is he did not reveal intentionally or through his affect whether the second student, Miguel, was right. He merely said: “Great let’s take a look at your work, then.” THis maintained everyone’s focus. No students though–“Oh yeah i got this” and checked out. The suspense remained.

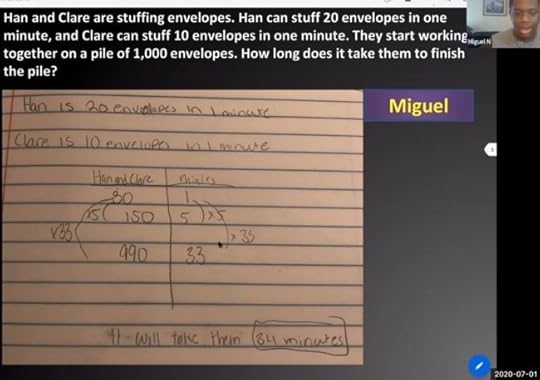

And then Jeff shuffled through a few slides and projected Miguel’s answer. In other words he had examples of all of his student’s answers ready for easy study. Now, this was easy for Jeff because his model class had only four students, but in a real class of 30 you wouldn’t have to have every student’s work ready to show call. You could just have common answers and errors and say, “Great let’s take a look at someone who did what Miguel is talking about…” The point is that he’d planned his lesson around a ‘deck’ of show call images that allowed him to make student work the center of his classroom.

A s students made points he could quickly shuffle and Show Call and example of what they were talking about. With the work always visible to students, he could let them engage in meta- problem solving–that is reflecting on and critiquing their initial problem solving strategies.

That’s high level work and to do it you need one thing above all. To solve a problem you have to be looking at the problem, and Jeff’s Show Call deck allows him to do that.

The post Tips for Online Show Call from Jeff Li’s Lesson appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 1, 2020

The TLAC Summer Guide to Movies: Science Fair

It’s going to be a long summer if the TLAC Blog is your sole source of movie recommendations, but I do want to highly recommend one film: Science Fair.

It offers so much to think about for society and schools… the amazing science teacher at Jericho High, Serena McCalla, with sky-high expectations; Myllena and Gabriel from rural Brazil doing ten times as much as the average kid with a fraction of the resources. But especially, especially the story of Kashfia Rahman.

When the film was made she was a high school student in Brookings, South Dakota where, essentially, she and her dreams of science are invisible and irrelevant to the institution.

Her interests are in neuroscience and psychology and she does amazing research on the biochemical changes that come from persistent risk-taking behavior among teenagers. The film ends with her winning a huge prize at the insanely competitive International Science and Engineering Fair. It’s profound work for a teenager. For anyone. Three years later you can see her TED talk on the topic. In the epilogue we find out that she’s since gone on to Harvard.

But through no fault of her school.

At the beginning of the movie Kashfia takes the camera for a tour of her school- the three gyms, the massive trophy cabinet. Is there a lab you can use? her interlocutor asks. She laughs. She couldn’t find a teacher to sponsor her work so she asked the football coach. He said yes which was nice though it seems like he offered more encouragement than scientific support. There’s footage of them talking about her work and he appears to be thinking, in the most decent way possible, I wish I knew what you were talking about.

As she nears the finals of perhaps the most prestigious science competition in the country the film-makers ask students in the school about it. No one knows about her work. No one even knows who she is. They don’t even know she goes to the school. Even after she wins a huge prize, the school never thinks to honor her work or announce her results or to try to find ways to make it easier for kids like her to do more work like that. She’s not even a happy anomaly. Just an anomaly.

A brief aside: In my first year of teaching I had a student named Leonard L. Lovely kid. A good student but maybe not great . He was my advisee. Met with Dad, who had gone to school in his native Taiwan and wanted Leonard to be a great student and to want to do great things.

Dad said: “I don’t understand. There have been three pep rallies for sports this year. Where are the pep rallies for academics?” For years I thought that story was quaint. Funny even. I told it at parties. I don’t think it’s funny any more. I see, now that I’m a dad, that the question wasn’t a critique of the school (which is how I heard it then, in my twenties) so much it was a plea for culture: he wanted the school to bring the best out of his son. He wanted it to help make him more likely to aspire to more.

(Aside to my aside: Mr. L. please know that one of the first things I did when I became a school leader was to add pep rallies for academics).

At Kashfia’s school, like at most schools, culture is mostly an afterthought. To the degree that there is an intentional culture, it’s about school pride not achievement and knowledge. If some kids choose academics; good for them. But most schools don’t see it as their job to actively foster that. The school I worked at was always trying to undercut the Mr L.’s frankly. The staff thought they put pressure on kids. Their ardent aspirations were quietly mocked by the sophisticated members of the faculty.

Kashfia’s parents are immigrants from Bangladesh. She wears a hijab. She doesn’t appear to care much about what her peers in school think. She’s quiet but strong and motivated by her parents’ sacrifices. She goes about her business in with graciousness and quiet drive. She was by far my two daughters’ favorite kid in the film.

But her unique strength and drive are also the problem. How many kids would and could do so much more except that they lack strength of character and vision to doggedly pursue what no one cares about and what is quietly snickered at in order to achieve things that benefit not just themselves but society.

Her HS is like most American schools. It doesn’t really see it as its job to shape culture, especially not academic culture. To go out of its way to make the world safe and encouraging for academic endeavor. To metaphorically speaking or perhaps literally have pep rallies for academics.

And find me a college–I can speak from experience here– that doesn’t denigrate the Kashfia’s of the world in the admissions process. It’s an article of faith for them to tell you: we’re not a school for ‘one dimensional’ kids who like to spend their time in the library or the lab (read: Kashfia). As if Khasfia would be so much more well-rounded, such a better applicant, if she only played lacrosse instead of all that ground breaking research. Colleges tell students this because they understand the market. They are speaking mostly to lacrosse players who come from schools that think lacrosse is more important than lab science, and the colleges want those kids to apply, so they talk their talk. But also maybe they have started to believe it. I took a tour of an elite college two years ago (mean SAT 1415, acceptance rate 23%). The tour guide was describing the requirement of a single quantitative course. “Don’t worry though,” he told the elite scholars standing before him. “Almost anything counts as a quantitative course. You don’t really have to do any math or anything.” I spent a few minutes imagining top universities in Europe or Africa or Asia apologizing for asking students to take a math class.

The story ends happily for Kashfia. She’s off to Harvard. But maybe the ending’s not so happy for the hundreds of thousands of kids who go to schools that just don’t think academics are all that hugely important. Nor for the parents who, like Leonard’s dad, want schools that are a bit more serious about bringing out the best in their kids, who want teachers like Serena McCalla to push them. Many such parents, unlike Leonard’s dad, haven’t been successful in school themselves. They can’t offer chemistry experiments at home, as Leonard’s dad was ultimately driven to do. They failed at school or were failed by school and paid the price–pay it everyday in many cases. The school their child attends is their one chance to change the game for their child. It’s one reason why Robert Pondiscio’s book How the Other Half Learns is so profound. Read it all closely but read the paragraphs where the parents speak about this twice.

What they want is a school that will not stand idly by and let what could happen or what mostly happens happen to their kids. They want a school that will share their dreams and do everything it can to help every kid unlock the scholar within them. We should ask ourselves every day if those are our schools.

Finally the movie makes a pretty clear statement about immigration and the gift that Kashfia’s family brought to this country in moving here. She is driven to create value for the world around her with a grace and decency that exceed her years. She’s everything we should be seeking to be. But her family being here, her success in school- they are as much despite and because of the policy things we do as a nation. To watch this film and contemplate the idea that somehow we don’t have room for families like Kashfia’s who want to come here and do worthy things among us, that we shouldn’t be grateful to them for coming- that, to me, is mystifying.

Anyway, I highly recommend the film.

The post The TLAC Summer Guide to Movies: Science Fair appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 19, 2020

Marine Academy Plymouth’s Jen Brimming Models Implicit Accountability

True…. but not complete…

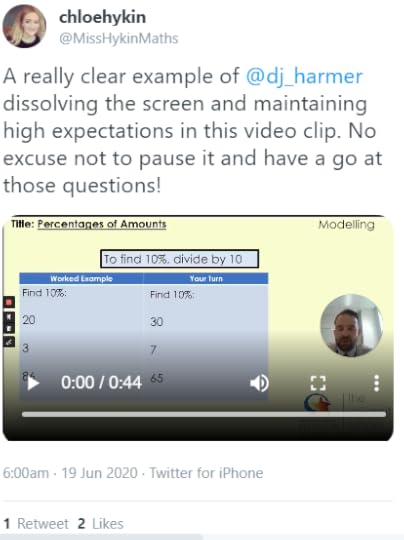

True…. but not complete…Yesterday I blogged about one of Chloe Hykin’s lessons at Marine Academy Plymouth. Not only was it really well designed and implemented but it was clearly part of an intentional school-wide effort to produce consistent and high-quality Lessons.

Her response on Twitter was to share all of her peers’ work to share the credit.

In fact the whole gang at Marine Academy seem intent upon shining a light upon the work of their peers and showing how much the appreciate them. It’s one of the things I love most about teachers and schools, honestly.

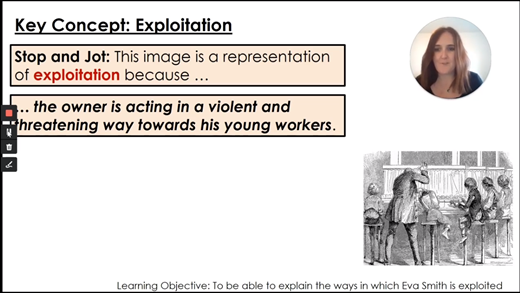

Anyway, one of the lessons Chloe shared a clip of was this spectacular example her colleague Jen Brimming bringing a bit of what she called “Right is Right” to her lesson … and which I think is just as profound an example of implicit accountability–socializing students to self-assess against a model during online instruction. It’s both a necessity in asynchronous instruction and an opportunity to perhaps build student ownership of the learning process. But it’s hampered by the Dunning-Kruger Effect… novices don’t realize what they don’t realize. So if you say: “If your answer looked something like this, give yourself a check-mark,” the students whose answers look nothing like yours are likely to fail to perceive the difference. They’re likely to say, “Yup, that’s what I wrote.”

Anyway, Jen does a beautiful job of anticipating error and planning with that potential for mis-perception in mind. Here’s what she does:

When she asks students to self-assess, she says, “Let’s have a read of an answer I think some of you may possibly have written.” On her screen, she displays a response that she thinks students are likely to have come to—a solid start, but not a complete answer.

She says, “While this answer, I think, is mostly right, if we want to be on the path to university, we want it to be right right, so let’s have another look at the definition [of exploitation].” Instead of displaying the correct answer, like many teachers do in implicit accountability loops, Mrs. Brimming has chosen to highlight her anticipated student response, an answer that is on the right track, but doesn’t quite meet her exemplar. This allows her to give targeted feedback for revision, ensuring that students who have written something similar recognize the gap in their response.

Then, she rereads the definition of exploitation to

students again, emphasizing both parts of the definition, and gives feedback

for revision. She says, “So if you have an answer like this, you’ve done well

in explaining how this factory owner is treating these workers in an unfair

way, but we’ve maybe missed out how this would then benefit himself. So what

we’d need to do to make this answer right right is to add something like this.”

Then, she adds a second idea to her first response, a clear visual reminder of

the importance of revision.

By breaking down the exemplar response into these two parts, she ensures that students who may have missed the second, subtler element can clearly see the gap in their understanding, and have the opportunity to revise their work and close that gap. She ends the review with an opportunity to rewrite, saying “If your answer doesn’t quite match that, get your green pens out and check that it covers both parts of that definition about treating people unfairly in order to benefit yourself. Pause the video now and have a check of your answer.” Revision is built into the class’s structure (there’s even a designated revision pen), creating a culture of self-assessment and student accountability.

Thanks again to everyone at Marine Academy for such thoughtful work. I’ve learned a lot from you all this week.

The post Marine Academy Plymouth’s Jen Brimming Models Implicit Accountability appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

June 18, 2020

Tiny Little Post on Perception, Batting Practice & Goalkeeping

Probably not helping that much

Probably not helping that muchHad the opportunity yesterday to spend an hour taking with a group of female soccer coaches from around the country who are part of a mentoring program put together by Columbus State coach Jay Entlich.

The theme of the session was perception and one of the things we discussed was how to coach players in settings where they had to make decisions faster than the conscious brain could process (usually about 6 tenths of a second).

One comparison we looked at was major league baseball players. The average pitch arrives at home plate in four tenths of a second, so in order to succeed, batters must read cues from an opposing pitcher’s delivery before the ball’s release: arm channel, angle of shoulder, hip rotation. A batter makes an unconscious link between perception and action. Batters are hitting the pitcher as much as they are the ball.

Several coaches on the call were goalkeeping coaches and they were for obvious reasons especially interested in the analogy.

After we hung up I remembered something a friend who works with a major league baseball club told me a few weeks ago. Let’s call it The Pitching Machine Problem

“They [a group of coaches] secretly think BP [i.e. batting practice but not vs live pitching] is a waste of time. They let hitters do it because they are used to doing it and because it gives them psychological comfort. But unless the visual cues are the same as what they’re going to face in the game, from a hitting perspective it’s useless. The pitching machine is a waste of time. The 50 year old coach throwing half speed? Same. You might be able to use it to groove a new swing but it won’t really help you hit… it won’t help your OPS.”

That’s the Pitching Machine Problem. For any reactive action that has to happen at the limits of conscious processing speed, unless the visual cues replicate the game, the practice probably won’t help that much.

Q: Whatcha lookin’ at, Bernd?

Q: Whatcha lookin’ at, Bernd? A: The shooter, not the ball

Anyway it struck me that goalkeeping coaches–and a lot of others–sometimes spend a lot of time training goalkeepers by throwing the ball to them to simulate a shot. Or having athletes field shots that come at them in some manner that does not involve reading cues before the shot. There’s some value in that–confidence; flexibility, honing the fluidity a new movement; making sure hand position is correct–but under pressure, goalkeepers are reading the shooter not the shot, so once the fundamentals are in place, the value of such activities may drop off quickly.

Which I was thinking about on the treadmill this morning (watching a series of Bernd Leno saves against Man City) and just thought I’d share.

The post Tiny Little Post on Perception, Batting Practice & Goalkeeping appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

‘The Level 2 Video’ & Other Lessons from Chloe Hykin & Her Colleagues at Marine Academy Plymouth

I’m happy to post another really useful example of a video with some good ideas for online instruction.

This one comes from Chloe Hykin and her colleagues at Marine Academy Plymouth, in Plymouth, England.

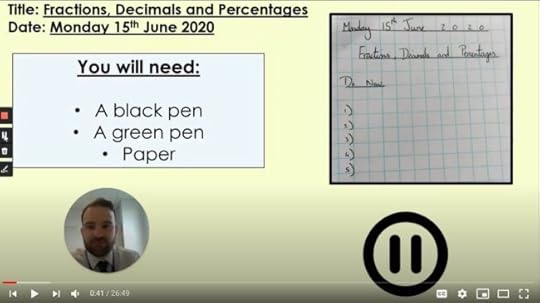

The opening of Chloe’s asynchronous lesson is a really well executed example of some things we’ve been describing on this blog:

Warm, face visible greeting that actively tries to ‘dissolve the screen’–connect with students around the work. This segues into an energetic and engaging demeanor.

Excellent use of a clear and helpful ‘materials screen’ to help students prepare consistently for class (and to allow their parents to help more too). Glory points to Chloe for adding a hand-written example of what the student’s hand written note page should look like. Just the other day we were discussing this at TLAC Towers… how we often say “make your paper look like mine” but “mine” is a PPT slide. Chloe really can use that phrase! We also loved the way Chloe planned out where her own face would be on the screen so she can point to the various places where models are found on the screen.

Finally her slides do a really nice job of sharing and organizing what’s important without including extraneous and distracting materials. This is one of the key points Daisy Christodoulou makes in her new book.

But there were other things we liked about Chloe’s lesson and they were things we haven’t seen as often. The thing we liked best perhaps was the mention she makes several times of a level two video. Chloe is constantly pushing her students to self-assess and to not be afraid to calmly acknowledge, yes I’m struggling. I mean, why not when there’s a handy review video that Mr. Hamer has produced that they can go watch.

We’ve written here about implicit accountability–socializing students to self-assess against a model during online instruction. It’s both a necessity–in asynchronous instruction–and an opportunity–to perhaps build student ownership of the learning process. But offering a real concrete action students can take to solve the problem–there are move videos; it’s just a matter of your choosing to use them–takes it to a new level. For now I’m going to call this idea of embedding contingency and choice in asynchronous video CYOA [i.e. Choose Your Own Adventure]

There are five warm-up questions for students to start with. Chloe does just ask students to do them but she’s actively building culture… “I want to see you having a go at every question, pushing yourself at the extension when you finish,” she says. Message: The quality of your effort online matters to me. There is a difference between done barely and done well.

We’ve written previously about “Pause Points” as well. They help you to make asynchronous lessons interactive. But the risk is the roll-through. Students either accidentally roll through the pause and fail to do the work or they deliberately do so because, well, I would have too at 14.

Anyway Chloe’s videos–and the rest of the videos her colleagues at Marine Academy Plymouth have produced–think carefully about this problem. There’s a bright clear reminder to “Press pause and have a go at your Do Now” but you’ll also notice that she often leaves a real time pause in there… she extends the dead time as a tacit reminder to students that they should be pausing. It’s like watching newscasters during a commercial break. It snaps you to attention a bit. And for kids who are slow to respond., well, they’re less likely to roll through by accident.

Also love the expectations expressed in the answer reveal: ‘ticking your answers there for me.’ Again, she’s doing everything she can to socialize follow-through and active engagement from her pupils.

Here’s a bit more of the opening from Chloe’s lesson:

Her discussion of the objective is nice in three ways. 1. She expresses genuine excitement for it and for the fact that it’s challenging. The good part is that it’s difficult. Cue Carol Dweck. 2. She reminds students about the resource video they can go to if they struggle. 3. She moves fast and is impeccably planned but like Joshua Humphrey not so planned that she sounds scripted. It’s warm and engaging but purposeful and we get to work quickly.

Finally we loved the fact that the lesson started with retrieval practice. It’s doubly important in an online environment where student attention can be hard to sustain to make sure learning is embedded in long-term memory and that key background knowledge is activated before a lesson. And of course there’s a great reminder–the third one so far!–that the level two video is there for students if they need it. It’s the most normal thing in the world.

Last note. Here’s a screen shot of her colleague Mr Hamer, he of the level two lesson. What do you notice?

Yup, me too! Absolute consistency. For a student who does decide to go back and forth between teachers nothing could be simpler because the visual environment and learning procedures are exactly the same.

Thanks to Chloe and everyone at Marine Academy Plymouth. They have a TON more great videos you can watch here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLc1Uh-Lm7CtoKE1c6NcqlKF8k5kKIC9Sr and their work is a real gift for teachers so I hope you’ll check it out.

The post ‘The Level 2 Video’ & Other Lessons from Chloe Hykin & Her Colleagues at Marine Academy Plymouth appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers