Doug Lemov's Blog, page 16

September 10, 2021

The First Days (of Cold Call) with Bradi Bair

About a week ago I posted a clip of Bradi Bair Cold Calling with her math students at Memphis Rise Academy in Memphis, TN. I wrote about how she observed which students had the best answers and used that to make her Cold Call an honor. This was a great way to build a positive culture around Cold Call that would last the whole year, I argued.

About a week ago I posted a clip of Bradi Bair Cold Calling with her math students at Memphis Rise Academy in Memphis, TN. I wrote about how she observed which students had the best answers and used that to make her Cold Call an honor. This was a great way to build a positive culture around Cold Call that would last the whole year, I argued.

Today I’d like to show a bit more of Bradi’s Cold Calling, again focusing on some things she’s doing that are particularly useful to make Cold Call succesful at the beginning of the year. This video shows more examples of Bradi Cold Calling from the same class i showed before. Each example is a little different.

Bair.CCMontage.mp4 from TLAC Blog on Vimeo.

The first clip begins with Bradi reminding her class, “When we are looking for the Greatest Common Factor of the variables, we are looking for the one with the smallest exponent.” She then pauses. She hasn’t Cold Called yet. In fact she hasn’t even asked a question but before she asks Vanessa what the smallest exponent is, she gives the class ten seconds of Wait Time to study the sample problem and think about what the answer might be. Giving everyone lots of time to think makes them more likely to be successful answering. Especially when she intimates with a calm and soothing tone that she might be getting ready to Cold Call. You might ask what I mean by the idea that she “intimates that she might Cold Call,” and by that I mean is her body position. She strikes a pose… let’s call it “thoughtful” that she usesagain and again during the lesson. Each time happens a bit before she Cold Calls. It cues perceptive students to get ready. It looks like this:

It reminded me of something Denarius Frazier does right at the beginning of this video:

“Take a second to look at this diagram,” Denarius says, “and get ready for some questions.” As he says this, a warm but slightly puckish smile breaks across his face. The smile (accompanying the phrase “get ready for some questions”) tells his students that Cold Calls are coming and that he thinks they are a good thing. He intimates that it’s coming and combines that with lots of Wait Time so students can get ready. Of course, Bradi is teaching with a mask on so she can’t smile to cue her students that the Cold Call is coming, so that pose is a great substitute. It communicates thoughtfulness and a bit of warmth.

Note also that after Vanessa gets it right, Bradi causes lots of positive energy to shine down on her student. There’s snapping from classmates–a signal of approval and support–and Bradi says, “Yeah, I like how she said that’s not just X, that’s X to the first power,” calling out something specifically effective and knowledgeable about her answer. She’s keeping all the rigor of the Cold Calling but making sure her students feel their success.

The second example of Cold Calling is a bit subtler. The key comes from the first thing Bradi says: “The first one it seems like we were all…pretty much in agreement.” She’s observed carefully and knows everyone has it right. But rather than skipping it she uses it as a chance to let Rosa “dunk” by getting it right in response to the Cold Call. Again you can hear those snaps of support–Bradi asks for them explicitly here–“Snaps if you also got 3x,” Bradi is creating opportunities for students to see themselves succeeding at Cold Call and to know whey can rise to the challenge.

On the third Cold Call Bradi’s body language is again key. Before she Cold Calls Beanna, you can see her in her “thoughtful” pose again. As Beanna starts to answer, Bradi “sends magic”… that’s the movement she’s making with her fingers. It’s a way she’s taught her students to show support to a classmate when the work is hard and she uses it herself sometimes too. She’s reminding her student that she wants her to succeed when she Cold Calls her.

In the last segment she Cold Calls Powell. “If we’re multiplying two numbers to make a negative Powell, what does that mean about one of my numbers?” Powell hesitates. Bradi deftly defuses any tension by saying, “I might have asked it a little weird.” Then she asks again: “If we’re trying to multiply to make a negative what does that mean about those numbers?” Now Powell gets it. “Yeah one of them has to be negative,” Bradi repeats in a cheery voice and classmates snap along to punctuate the success.

My point here is not just that Bradi is effective with her Cold Call but how carefully she designs it at the beginning of the year to build students comfort and familiarity with it (she Cold Calls again and again in this lesson) and to ensure that their interactions via Cold Call help them to feel the value of it: it keeps them on their toes; it challenges them but they in turn are mostly successful. And you can feel the engaged and positive energy in her classroom as the video fades out on her Turn and Talk. Her students, no surprise, are highly engaged in the task.

The post The First Days (of Cold Call) with Bradi Bair appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

September 3, 2021

What I Told My Kids About Doing Well In College/University

This is an odd post… more personal and covering not what I usually write about. I’m not sure how useful or interesting it will be to readers. But here goes.

When I first started writing about teaching my own kids were tiny, but time flies and I now have two college/university age students. They were good students in high school, but college is a bit different: it requires more time management; the amount of reading is different not to mention the portion of what you learn that comes from the reading; the teaching is different too- as are relationships with professors.

What to tell them about learning at the next level as they went off the make their way in the world? I tried to limit my advice to a few practical things that would make the greatest difference.

It struck me that other people might find it helpful too. So here it is: What I Told My Own Kids About Doing Well in College (or if you’re in the UK: University)

Don’t miss class: When your alarm goes off and you were out late you will say: “I’ll just do the reading.” But if you go to class, the reading becomes a form of retrieval practice. It elaborates on and connects to and reviews what you discussed in class. It helps to create long term memory. Get up and go to class. Take a nap after if you need to.Take notes by hand during class. You remember more of it if you write it out physically than if you type it. And you can’t go quite as fast so you have to be more selective. You can supplement what you write with diagrams. You are more likely to look up from the page (versus the screen) to look at the professor and thus increase your own attentiveness to what she’s saying. If possible re-type your notes later to process them and create a version you can study from.Read in hard copy; always. Underline and annotate in pencil or pen, not a highlighter. You remember more and can interact more actively when you read in hard copy. And not having your computer in front of you reduces distractions. So you are also more likely to be in a generally more attentive state of mind.Don’t wait til the night before to start readings/assignments/papers; weekdays when you’re not in class are key: schedule regular times to get work done ideally during the day when you’re not tired.Go see the professor. Even if you’re not sure you need to. Build a relationship. Practice talking to a professional about an area of study informally. Practice asking good questions.

That’s it. Now you know what I know. As I write this I realize I probably didn’t stress self-quizzing as the best means of studying enough… I guess that’ll be next.

Also there’s one more pet theory I had in college that I’ve been reminded of and still believe in: Whenever possible choose classes based on the professor. A good teacher will make anything interesting.

The post What I Told My Kids About Doing Well In College/University appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 31, 2021

Bradi Bair’s Cold Calling Models Positivity and Rigor

I’ve spent much of this week watching the first batch of video from school year 2021-22 classrooms. Watching classrooms with everyone masked is a bit disconcerting at first but it’s remarkable how quickly things feel closer to normal. Familiar interactions and relationships don’t take long to seem… well… familiar. And already there’s so much to learn.

I’m going to share a clip today from Bradi Bair’s math classroom at Memphis Rise Academy in Memphis, TN- one of our very favorite schools. In particular i wanted to highlight some really useful things about how Bradi uses Cold Call- how she establishes the positivity of the technique and how she uses it strategically to surface useful comments.

Let’s start with that idea, which you can see in the clip:

You’ll notice her Cold Call starts with a quick (just 30 seconds!) Everybody Writes. This is useful because it causes everyone to answer the question, boosting the Think Ratio, and ensures that anyone she calls on has time to be, and feel, prepared.

But just as importantly it gives her time to look … and to learn, to spot (and correct) common errors and Cold Call a student because she knows her answer is especially useful, rather than guessing or hoping what the student will say. (In TLAC 3.0, I call this Hunting, Not Fishing).

In this case she knows–as you can see from the appreciation she shares while circulating–that Vanessa has nailed it. That if she wants someone to talk about inverse operations she’s the one to call on. But when she says, “I want to go to Vanessa. Vanessa’s got a really strong answer for us,” she’s also establishing something about Cold Call that will stand for the rest of the year- that when you get Cold Called it’s just as likely because you’ve done something really worthy. It’s a good thing. An honor. You’re invited into the conversation specifically because you have so much to add.

But as you can see Vanessa seems a little hesitant at first. Maybe she’s a bit shy. an important thing to notice then is how Bradi tries to keep it positive. She doesn’t rush Vanessa. And she makes her words seem important by writing them down and calling them “crucial.”

But she also does something you might miss.  Remember, it’s early in the year so she’s working to build culture around Cold Call so notice that Bradi makes a subtle sending magic gesture… that’s what she’s doing when she points her fingers subtly wiggles them. Sending magic (left) is a way of saying, I know you can do it. I am supporting you. This is doubly useful so when you are masked and students can’t see you smiling!

Remember, it’s early in the year so she’s working to build culture around Cold Call so notice that Bradi makes a subtle sending magic gesture… that’s what she’s doing when she points her fingers subtly wiggles them. Sending magic (left) is a way of saying, I know you can do it. I am supporting you. This is doubly useful so when you are masked and students can’t see you smiling!

One other thing to be aware of is that the more often you do something the more normal it becomes. I counted more than a dozen Cold Calls in Bradi’s class. All of them with a cheery positive voice and lots of Wait Time… often with a Turn and Talk or an Everybody Writes before them. Interestingly though, she was doing mostly name. pause. question rather than the default question. pause. name . The reason I think might be that later in the year you don’t want students to know who’s getting the Cold Call but perhaps at the beginning of the year giving them a little more of a heads up, a bit more time to get ready and learn the rhythms of the technique is ok too.

Thanks, Bradi and Memphis Rise for sharing your great teaching with us!

The post Bradi Bair’s Cold Calling Models Positivity and Rigor appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 25, 2021

Joe Mazzulla’s NBA-Level Positive Framing

Over the past year or two I’ve had the pleasure of working occasionally with Joe Mazzulla. Joe is an assistant coach with the Boston Celtics and this summer was the head coach of their NBA Summer League Team. He also wrote two really great side bars in The Coach’s Guide to Teaching.

The NBA’s summer league is mostly about player development–both in terms of skills and mindsets–but of course everyone wants to win.

You can see Joe steering his players focus to the long term habits of success in this amazing video shot at a time out during the summer league championship game. It’s an exceptional example of using language to frame challenges positively and build productive mindsets.

As the clip opens Joe tells players in the huddle that “the whole point of summer league is to gain experience in hard situations.” Yes, it’s a challenge. That’s a good thing. It’s your opportunity to learn to be a professional. Embracing the difficult moments is why you’re here and how you grow. The (growth) mindset of an athlete at the elite level has to be: oh good, a difficult situation in which to test myself against the best.

“You’re playing against other great NBA players,” Joe continues, “Now you have to have ownership. If you let him get going, you’ve got to shut him down. It’s a great opportunity….” I love that language. A challenge is an opportunity to better yourself. That’s the mindset. Even in the midst of the championship game. It’s a beautiful example of a coach focusing on the long-term for his players.

Joe spoke more about this when I asked him about the clip. The Celtics had won their first four games and were now in the final. “At that timeout I felt like it was the first sign of adversity we’d hit during summer league. As much as we wanted a championship I felt our guys were so results oriented. I tried to shift their minds back to the process, to what summer league was about.” That included developing the ability to focus on “what was going wrong for us and how we could change it,” which is to say taking ownership and relishing the chance to do so.

I want to note here that having watched a few of Joe’s summer league practices, his emphasis on being able to ‘shut players down’ is not something he is simply players they have to know how to do. He’s taught its many pieces and they’ve practiced it. Over and over. He is focusing on the psychological side of one of the two or three technical things he’s emphasized most and preparing them to trust and use what they know, rather than telling them they have to know how to do something without embracing the responsibility himself of showing them how. “The psycho-social is always with us as coaches”, Dan Abrahams said to me recently. But it’s most useful to talk about mindset after we’ve done our homework as coaches on the teaching side.

The last thing Joe says is my favorite though. It’s a great example of talking aspirations (part of Positive Framing). “Every one of you guys is going to have to check into an NBA game and guard somebody…so let’s go.” He’s connecting his feedback to their aspirations… . It’s a reminder that he is pushing and challenging them because he understands where they are trying to go. Because of that even when he is telling them to step up the message that he believes in them is clear.

The ‘positivity” in Positive Framing, I wrote in the 3.0 version of TLAC, is “the delivery of information

students [or athletes] need in a manner that motivates, inspires, and communicates our belief in their capacity.” That positivity so clear, even when Joe is pushing players to be better.

The post Joe Mazzulla’s NBA-Level Positive Framing appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 24, 2021

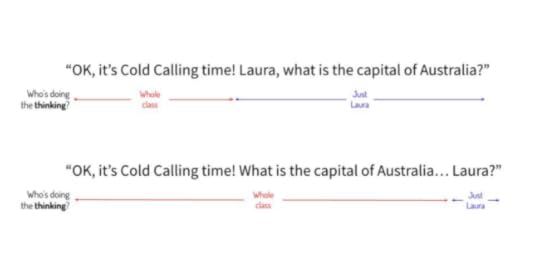

A Graphic Representation of Timing the Name in Cold Call

A few days ago I came across the above outstanding illustration created by Luke Tayler, a geography teacher in Bahrain. It captures in graphic form the power of timing the name during Cold Call.

The basic idea is that when students know you might Cold Call and you use a structure of question-pause-name for your question, you cause all of the students in the class to answer the question in their heads.

When you use the structure name-pause-question then you’re less likely to have everyone doing the cognitive work. There are of curse times when you might choose to use name-pause-question but as Luke’s elegant graphic makes clear, the default should be question pause name.

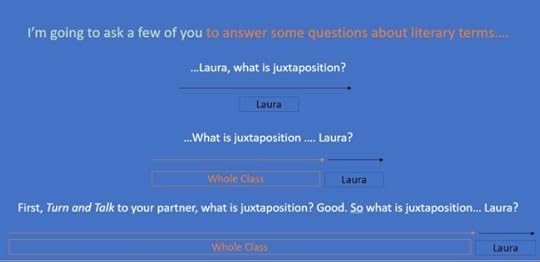

This morning over coffee I was mucking around with the idea of representing Cold Call graphically because others also seemed to find the image really compelling. I tried to put together a derivative graphic that captured the duration of student thinking that could be added by a Cold Call preceded by a Turn and Talk when (as the phrase “I’m going to ask a few of you” implies) students know the Cold Call is coming.

Similarly this version, which puts the Turn and Talk after the Cold Call and asks a harder question captures the desirable difficulty we can create. Not just who’s thinking but how hard:

There’s lots more you could do with this idea of representing the thinking graphically… unfortunately my mucking around with ideas time is done for the day. Thanks to Luke for the inspiration (and Kate Jones for sharing Luke’s work).

There’s lots more you could do with this idea of representing the thinking graphically… unfortunately my mucking around with ideas time is done for the day. Thanks to Luke for the inspiration (and Kate Jones for sharing Luke’s work).

The post appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 23, 2021

Woolway: Making Writing Part of the Thinking Process

TLAC Chief Academic Office Erica Woolway has been reflecting on the role of writing… in classrooms and in learning. She shared this reflection:

Writing is incredibly important to us- as educators and parents but also as learners ourselves. We are constantly struck by how much we use writing as part of the thinking process. And our belief in writing impacts not just the advice we give teachers for their classrooms but how we run our own meetings. Anytime we pose a question to each other for discussion we inevitably ask people to write first: “Take one minute to write and then we’ll discuss (or brainstorm).”

We were reminded of this at a recent remote workshop on writing, and the take aways that participants had specifically on the power of Formative Writing—writing specifically designed to support thinking. They reflected on how powerful the Formative Writing opportunities were in our workshop and how little they ask their own students to write formatively throughout class, too often focusing on the summative writing that comes at the end of class (and is often squeezed out due to time).

So we wanted to share a few excerpts on the three types of writing from 3.0 that help inform this approach. These ideas were informed by Judith Hochman’s The Writing Revolution, in Reading Reconsidered, and are a driving force behind our ELA curriculum (which you can learn more about here):

“Formative Writing is writing in which students seek to decide rather than explain what they think. The purpose is to use writing as a tool to think: to develop and discover new insights rather than to justify an opinion they already have. In contrast, the purpose of summative writing is to explain or justify the writer’s opinion and often to include evidence to create a supporting argument. Summative writing says: Here is what I think and why. To complete a summative writing task, students must already know what they think and be ready to marshal evidence and select an appropriate structure to make a cogent argument.

Summative writing is probably the most common form of analytical writing done in schools, in part because it looks like—and therefore (we often think) must prepare—students for the sorts of questions they are asked on assessments.

Again, in summative writing you have to know what you think before you start; in formative writing the purpose is to find out.”

Here’s a gallery of summative and formative prompts from different subjects that we share in our Engaging Academics workshops (click here for our calendar of upcoming workshops!), placed side-by-side for comparison:

Formative PromptsSummative PromptsELAWhat might be the figs be symbolic of

in this chapter?

What are some reasons

they keep appearing?

Explain the symbolism of the figs in thechapter and explain what Munoz-Ryan

was attempting to accomplish with this

symbol. Make reference to at least three

occasions in which the figs appear.

MathTry to describe the relationship between the two pairs of lines. Give it a go.What is the relationship between parallel and perpendicular lines?ScienceLet’s think in writing. Would you expect neurons to have a high or low surface area to volume ratio? Why?Explain how neurons function. Be sure to reference specific details about their cellular design.HistoryWhat events might the founders have been nervous about when they built the system of checks and balances?Explain how the founders’ vision of checks and balances influences our governmental structure.EarlyElementary

How might Paddington be feeling in this moment? Why?Based on this story, what are two character traits that describe Paddington? Support your answer with details from the text.ArtsTake a stab at this question: What suggests the farmer is important in the painting?Explain how the use of color and light show that the farmer is the central figure in the painting.

In our workshops, we ask participants to reflect on the two types of writing and how teachers might think about balancing to the two in order to maximize ratio. Here are some reflections on that from 3.0:

Formative Prompts and Summative Prompts

“One thing you’ve probably noticed is the openness of the formative prompts. They ask for “some reasons” rather than “the reason” or “the reasons”—all of them, presumably. The change encourages students to consider more than one possible answer and implies that it’s hard to say how many reasons there might be. They ask questions for which it is hard to be wholly wrong as long as you are diligent and thoughtful, as in: “What strikes you about . . .” Perhaps the most important word in many formative prompts is the word “might.” What might the figs be symbolic of? Rather than: What are the figs symbolic of? Or: What ideas might the artist be attempting to convey with his choice of colors? “Might” makes it clear that goal is to explore, not to prove; the stakes are lowered.

The lowering of stakes can be powerful with writing. Putting words to page is intimidating, so it is understandable that many students may have trouble beginning the process. “I don’t know how to start,” they tell us. Often, perhaps, that’s because summative prompts set the bar so high. “Explain your opinion about X or Y.” There are Xs and Ys in the world I have been thinking about for years and still have not fully arrived at an opinion about. I hereby propose that the ability to think without deciding too early is a very good thing intellectually. A formative prompt lets you start with maybe. Maybe one reason is . . .

A few years ago, we discussed the idea of formative writing with Ashley LaGrassa, then an eighth-grade English teacher at Rochester Prep in Rochester, New York, and she decided to give it a try. After all, eighth grade might be one of the toughest years for getting students to open up in writing.

“The idea that a simple change of format might make my classroom feel safer for students, leading them to take risks and engage more deeply, was too alluring to pass up,” Ashley said, “and the result was one of the most joyful lessons of the year. My eighth graders jumped in to wrestle with challenging questions, pregnant with the possibility of multiple ‘right’ answers.” Afterwards she reflected on what worked and why.

The lesson focused on Alice Walker’s “Beauty: When the Other-Dancer is the Self ” and began with formative writing as part of the Do Now: “How might Alice Walker’s experiences have influenced her writing?”

“My hope in including the word “might” was to help students feel safe jumping in with thoughts rather than comprehensive answers,” she said. Students jumped in and she was happily surprised to see “twice as many hands as usual” offering to share their answers. On a later question, Reflect on the role of gender in Walker’s experience, she again found that “students went right to work. There was no flipping through the packet or rewriting of the question to pass time. Students began quickly jotting down their thoughts; seemingly, the sense of possibility within the question made students feel more comfortable with risk.”

The subsequent discussion too crackled to life. “Within moments, students were deeply analyzing the impact a scar discussed in the text had on Walker in light of her gender, moving from her specific experience to a message about society at large. By asking students for their reflections, the question invited students to share all thoughts and suggested a validity in a variety of responses. This encouraged them and prepared them to take the risks.”

Formative questions made writing a “low-risk adventure” in which students “didn’t always have to have a final argument about the theme to discuss the story.” You can see this play out in the video Arielle Hoo: Keystone. Arielle asks her students to write their “conjectures” to start their reflection on a problem. She is suggesting “We’re just thinking and experimenting with ideas at this point.” She says go and the class springs into action.

Ironically, students are more likely to have a strong final argument about the theme if they’d had time to wrestle with the idea formatively first. In other words, the argument isn’t that formative writing is “better” than summative writing, because it isn’t. Both are important and students need to be able to do both. Rather the argument is that formative writing is also necessary—if more likely to be overlooked—and that the two types of writing are synergistic in a dozen ways. For example, formative writing helps students engage in and care about the text so that they feel more vested in any argument they then decide to defend or explain in summative writing . . . which in turn helps them to understand what things they should seek to understand or figure out through formative writing.”

We believe in the power of Joan Didion’s quote – “I write to know what I think.” When you ask your class to write, you are therefore asking all of your students to think, and of course the same is true of adult learners. We therefore rely heavily on Formative Writing with the hope that in modeling techniques for teachers and leaders to experience them as adults, that they will experience the impact of the techniques on their own learning and be more likely to bring them to the classroom.

The post Woolway: Making Writing Part of the Thinking Process appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 20, 2021

TLAC 3.0: Using Turn & Talk to Make Your Classroom ‘Crackle to Life’

Just a few more weeks now til TLAC 3.0 drops. But of course the new school year is already underway so I’ve been trying to share excerpts in advance. Here’s the beginning of the write-up on Turn and Talk, with amazing video of BreOnna TIndall and Sarah Wright’s classrooms.

Turn and Talk—a short, contained pair discussion—is a common teaching tool used in thousands of classrooms and it offers a lot of benefits.

Among others:

It boosts Participation Ratio. You say “Why is Scout afraid? Turn and Talk to your partner for thirty seconds. Go!” and suddenly fifteen voices are going at once instead of just one. In a short time you’ve allowed almost everyone the chance to share an answer.It can increase reluctant students’ willingness to speak in larger settings. A student rehearses an idea she might not offer in front of thirty people, and finds it comes out well or earns admiration from her partner. She becomes more willing to share her idea with the whole group.

It’s a great response when the class appears stuck. You ask a question, get only a smattering of hands or perhaps none at all, and respond: “Hmmm. No one seems quite sure. Turn and Talk with your partner for thirty seconds. See if you can come up with some ideas. Go!” Suddenly you have a workaround for explaining the answer.

It can allow you to listen in on conversations and choose valuable comments to start discussion with, as in, “Maria, would you mind sharing what you and Justine talked about?”

But there are challenges to go with the benefits. Because it can result in fifteen people talking at once does not mean it will, and a disengaged Turn and Talk where there’s little turning and even less talking is a culture killer. And there are a variety of accountability challenges:

Conversations may wander off the assigned topic and may never even address the topic at all. (It is, after all, exciting to have the chance to chat with your friend in the middle of class.)

There is the risk that students in a Turn and Talk listen poorly—that their partner is merely a target for their own words and not a source of insight.

Even if everyone is on topic and listening their hardest, erroneous information could still spread. Billy Knowsforsure tells Tammy Tendstobelieve that to take the square root of something means to divide it by two; she nods, begins committing it to memory, and you never know it.

Education researcher Graham Nuthall, carefully observing students during lessons, found that students frequently persuaded their classmates that erroneous information was true. The most credulous were likely to be those with the weakest knowledge on a topic.

So used frequently does not always imply used well. The details of execution are critical. BreOnna Tindall’s execution of her Turn and Talk in the video BreOnna Tindall: Keystone provides a road map. Students have read a short passage about the idea of “blind justice” and have been asked to discuss whether the idea of justice being blind is supposed to be a positive or a negative symbol. BreOnna gives a direction: “One minute to Turn and Talk. Share out your response with your face partner. Go!” Suddenly, the room crackles to life.

Her success starts with the directions. They are crisp and clear, without an extraneous word, economy of language exemplified. The speed and energy of the transition capped off by the cue to action “Go!” means that everyone starts at exactly the same time. No one has time or incentive to glance around and see if their peers are really doing it. In these ways her directions exemplify technique 28, Brighten the Lines.

Of course it’s critical that Turn and Talk is a familiar procedure. BreOnna has taught her students how to do Turn and Talk well and they’ve practiced it. You can see their familiarity with it in the video. They know who their partner is without having to ask; they start their conversations comfortably and naturally; they speak at the appropriate volume. And perhaps most of all, the practice has taught them that since everyone is going to join in the Turn and Talk with energy and enthusiasm, they can safely do the same. This lack of hesitation is one of the main reasons why just seconds after the prompt, the room crackles to life.

Interestingly, it’s not just one procedure. As the phrase “Turn and Talk with your face partner” implies, there are face partners and also shoulder partners. BreOnna can keep things fresh by shifting which partner students talk to. Her room layout is designed around Turn and Talk!

And don’t overlook her phrase “share out your response” as it implies something important. Of course, they have plenty to say. Students have written first and are sharing what they wrote. As with whole group discussions, writing first means a more substantive and inclusive partner discussion (see technique 40, Front the Writing). As we will see, Turn and Talk works best when designed for synergy with what happens before and after.

Finally, BreOnna tells her students they will have (just) one minute to talk. This helps them gauge the appropriate length of their comments. And, ironically, keeping the Turn and Talk short maximizes its value. It’s a preliminary to the larger class discussion, so BreOnna wants students to have more to say, still, when it’s over. She doesn’t want them to say everything yet.

You can see many of the same themes in the video Sarah Wright: Keystone.

First, Sarah asks a question: “Imagine you are Tio Luis [in Pam Muñoz-Ryan’s novel Esperanza Rising], what would you say?” This is a reiteration of a question they have already responded to in writing, and now they get to share their brilliance. There are hands in the air. Lots. Students are eager to talk so this might seem like a surprising moment to choose a Turn and Talk. One of its best uses, I noted earlier, is to help build engagement when students are hesitant. But here it’s useful for the opposite reason. When you have lots of eager hands, Turn and Talk can be a great way to let everyone get to talk and to minimize the I had a great answer and didn’t get to share it frustration.

Like in BreOnna’s classroom, Sarah’s directions are crisp and clear with no extra words. They end in a consistent in-cue—the same as Breonna’s, “Go!”—and again the room crackles to life. You can then see Sarah circulating, listening to answers, sharing her appreciation, and also perhaps deciding whom to call on.

But again, not every Turn and Talk looks like these. How does a teacher build this level of energy and productivity?

The first step is ensuring that students feel responsible for doing the task in front of them to the best of their ability. Once you’ve done that, you can begin to design the activity for maximum rigor. This “all in” attitude is achieved mostly through intentional habit-building.

In the videos, neither BreOnna nor Sarah tells their students, “Be attentive; be active; do your best, and talk about the topic at hand.” Those things are understood. Students do them automatically, which means they are carefully taught and reinforced until they become routine.

Build the Routine

A Turn and Talk is a recurring classroom procedure; a common means for students to engage ideas. The more frequently something recurs in the classroom, the more important to make it a routine—to map the steps of the procedure, then rehearse and repeat it until it happens smoothly and with almost no drain on working memory. You can read more in Chapter Ten about installing routines but some specific aspects of the Turn and Talk routine deserve specific comment.

“My Turn and Talks actually used to be pretty ineffective,” BreOnna shared. “[Students] would not talk—or they would talk about something else.” Now, though, she builds in “an extensive rollout where I explain ‘this is what I’m expecting [active on-topic conversations; asking questions of each other], this is the type of language I want to hear [academic vocabulary]. I want to see these actions [nodding; facing each other; showing your partner you’re listening].’ It could seem a little Type A but I honestly think kids just don’t know how to have an academic conversation in a way that brings out the best in their partner. I try to make sure they have all the tools before they need them.”

The post TLAC 3.0: Using Turn & Talk to Make Your Classroom ‘Crackle to Life’ appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 11, 2021

Hernandez: The Time is Now for Understanding Learning, Forgetting & Retrieval Practice

After eighteen months, schools are at last welcoming students back to classrooms. But even as it feels like we’re approaching some semblance of classroom normalcy, questions about how we can help students catch up academically after a year of virtual/hybrid instruction loom large. Although it can be hard to precisely quantify the academic impact of this past school year, a recent report published by Curriculum Associates and McKinsey & Co. estimates that students in grades 1-6 are returning to classrooms an average of five months behind in math and four months in reading. Even more troubling is that the academic effects of this past year have been inequitable, leaving students of color and from low-income households even further behind than their white and more affluent peers.

Although there’s no silver bullet solution, we think a smart bet is to look to cognitive science to guide us. Over the past 25 years, cognitive science has revolutionized our understanding of how students learn, but much of that research hasn’t influenced teachers’ practice. In fact, one common definition of “learning,” that some cognitive scientists use is, “a change in long-term memory.” That’s a provocative definition. Part of us resists it. It has to be more than that. But it that pushes us to understand some of the gaps in how we teach. If students understand something during a lesson, but not a few days later, it’s hard to argue they’ve truly learned it.

In the following post, I’ll unpack snippets from Doug Lemov’s forthcoming Teach Like A Champion 3.0, which offers practical advice on how teachers can implement one of the most potent research-backed tools for improving student learning: Retrieval Practice.

–Joaquin Hernandez

Why Forgetting is So Key to Learning

In Teach Like A Champion 3.0, Doug begins his chapter on Retrieval Practice by describing a scene from the life of every teacher:

On Tuesday you are confident in your students’ skill and knowledge. They’re solid on the what, why, and how. But when you assess them a week and a half later, it’s as if Tuesday’s lesson never happened. Then, Rodrigo completed five complex area problems with ease; now you glance over his shoulder and see that he has gotten even simpler problems wrong.

As educators, we’ve all felt the disappointment of this moment. But as Doug points out, ironically there’s a silver lining to this endemic challenge:

“The process of forgetting contains the seeds of its own solution. If you ask students to recall what they learned yesterday about the area of polygons or juxtaposition in Romeo and Juliet they will strain to remember but if successful, that struggle will more deeply encode the material in their long-term memories. They will remember a little more and forget a little less quickly.”

What Doug’s reflections help illustrate is how it can often feel like we’re fighting a losing battle against forgetting. But cognitive science suggests there are tools that can both interrupt and guard against this. One of the most powerful of these is Retrieval Practice, a research-backed practice that Doug defines as “the process of causing students to recall information they’ve learned after a strategic delay.” As teachers, we use Retrieval Practice whenever we ask students to pull information from long–term memory. On this practice, the science is unequivocal: the simple act of retrieving helps students remember more, for longer, and with greater accuracy. Every time we ask students to retrieve, we make it easier for them to recall this this knowledge when they need it, strengthen its connections to previous learning, and apply it in different contexts

When I first heard about Retrieval Practice, I thought it sounded like a fancy term for something teachers already do: asking students to recall stuff they learned. As it turns out, the apparent banality of this practice is part of its power. Although it’s a common practice in classrooms, many of are using it at a fraction of its potential. With a few simple, evidence-based tweaks, we can amplify the positive effects of Retrieval Practice on our students’ learning.

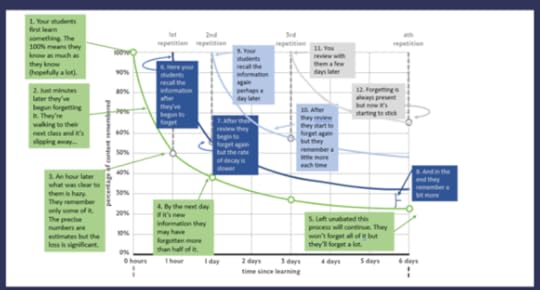

To help illustrate how forgetting works, and the role Retrieval Practice can play in interrupting it, Doug includes a graph of Hermann Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve (which he later annotated blogged about here). As Doug explains:

“If you graphed the process of retrieval practice it might look something like this, with each repetition along the top axis an iteration of retrieval practice and the percentages on the y-axis representing how much of a given body of content students remember.”

See it in Action: Retrieval Practice

To show what this technique looks like in action, Doug points us to the first half of this Keystone video from Christine Torres, an ELA teacher from Springfield Prep. In it, we see Christine asking students to engage in Retrieval Practice of some key terms they just learned.

https://vimeo.com/562266066/0fee9e6637

Christine’s textbook implementation of Retrieval Practice illustrates many of the principles that are borne out by the research. Here are just a few:

After a Brief Delay. Christine understands that the best time to retrieve something is once you’ve begun to forget it. Since forgetting starts right away, she doesn’t wait long before she initiates some Retrieval Practice. They start retrieving the content shortly after they’ve learned it. And as Doug notes: “Christine will be sure to follow up the next day and/or a few days later—and again a few days after that—with more fun and engaging questions to retrieve and apply their knowledge of their vocabulary words.”Full Engagement: Christine makes sure that every student wrestles with almost every question. She uses Turn and Talks (see technique 42). For retrieval, we can’t just take hands from volunteers or let a few highly verbal kids call out answers. We need to cause everyone to retrieve and apply newly learned knowledge.Low Stakes. Christine’s Retrieval Practice is truly practice. Students aren’t graded for accuracy or shamed for forgetting. This allows students to focus on recalling and applying the knowledge, notMeaning-Centered. As Dan Willingham notes in his outstanding 3rd edition of Why Students Don’t Like School, students remember more of what they are learning if they are required to think about meaning. Christine does a beautiful job of demonstrating this by asking students to respond to questions that cause them to consider different shades of meaning for key words with depth and richness.Immediate Feedback. Students immediately receive feedback for their responses. This is powerful in two ways: first, it clarifies demonstrate appropriate use of the vocabulary and which don’t, ensuring students encode the former and not the latter; second, it lets students know what they know and don’t know yet, allowing them to make smarter decisions about what to prioritize when studying and practicing.Routine. In Christine’s class, students routinely engage in Retrieval Practice after they learn new vocabulary. They know practice is coming, so there’s no “gotcha” when she calls on students to share answers. What’s more, Retrieval Practice—and the knowledge this helps students encode—has compounding effects over time. The more regularly you ask students to retrieve what the learn, the more deeply students encode what they in memory. Over time, this allows Christine’s students to acquire more knowledge faster, accelerating her students’ gains in learning and their ability to make meaning from complex texts.

Christine’s Retrieval Practice also helps dispel a common misconception, which is that it’s only about “rote memorization” and “simple recall.” As Doug writes:

“Notice the richness of the questions Christine asks…Christine asks her students to apply the vocabulary words they’re learning in different ways and new settings. That’s important because words work differently in different settings. To truly understand a word, you’d want students to constantly encounter it in all its nuanced shades of meaning. Christine asks students to know the definition, but also to apply the word in challenging and interesting ways. It’s both simple and more elaborated retrieval.”

With that said, there’s still tremendous power in simple recall. In fact, the memorization of seemingly trivial facts provide the building blocks that are needed for critical thinking and creativity. Practice strengthens neuronal connections and cements learning, providing students with a “springboard” to the holy grails of teaching: critical thinking and creativity.

Other Methods of Retrieval Practice

A common misconception is that Retrieval Practice always looks like oral drill or a written quiz. In fact, retrieval occurs whenever students engage in any activity that cause them to retrieve something from long-term memory. Common methods include: studying with flashcards, answering checks for understanding, engaging in a Turn and Talk, stop and jots, weekly cumulative quizzes, retrieve-taking (teacher pauses periodically during lecture to allow students to capture notes on what they just said), and brain dumps (where students write down everything they can recall about a topic). Whatever methods you use, a helpful tip is to vary them. Practicing in different ways increases students’ ability to transfer what they learn to new contexts.

Although it’s important to mindful of the classroom activities that qualify as Retrieval Practice, it’s important to distinguish them from those that don’t. For instance, rereading a passage, or looking back at one’s notes is not considered Retrieval Practice. True retrieval should be “closed book.” Simply rereading, highlighting, or looking back at a resource does will not encode new knowledge into long-term memory. It merely shows how well students can immediately recall something they just read from working memory. Effective retrieval should be effortful; it’s the struggle that comes with trying to recall something—without the help of a memory aid—that results in learning that lasts.

Using “Spacing” to Enhance Retrieval Practice

One of the most powerful ways we can enhance Retrieval Practice is by spacing it out over time. After a bout of learning, neuroscientists have found that the brain needs time—hours or even days—to consolidate and cement this new knowledge in long-term memory. What’s more, with each round of retrieval, students remember information for longer, which means students can go for longer between each round of retrieval. As Dan Willingham notes in his 3rd edition of Why Don’t Students Like School?, spacing can help students learn something with less practice than if they tried to bunch together their practice. In other words, spacing can help you save instructional time and even accelerate student learning.

It also helps to build retrieval into your lessons so you use it becomes a routine part of your class. Try making it a regular part of your lesson cycle, incorporating it into such activities like the Do Now, independent practice, or even in homework. Although there’s no “right” way to do this, we’d like to share a sampling of suggestions from educators we admire:

From Peps McCrea’s Memorable Teaching: “Make every third question in a problem set on a previous topic. Build regular cumulative quizzes into your teaching.” (page 83)From Uncommon Sense Teaching (by Dr. Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky, and Terrence J. Sejnowski): “Make every two problems on your homework from today’s lesson, two problems from the previous lesson, and two problems from earlier in the unit.” (page 153).

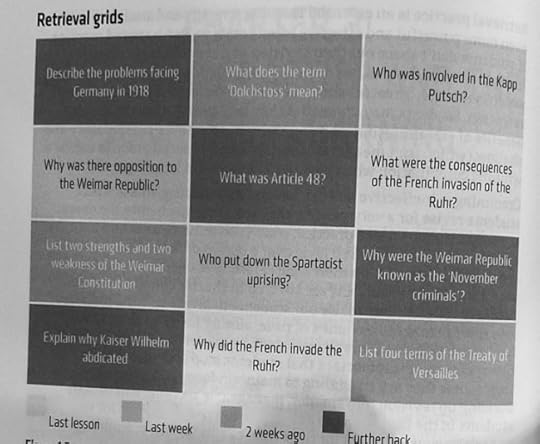

Inspired by Alex Laney: In 2017, Alex Laney shared some beautifully designed Do Nows, which sparked our team’s thinking about how teachers might incorporate Retrieval Practice and spacing in their Do Nows. As you can see in the image pictured here, one idea we had was to include tasks or questions on content or topics separated by increasingly longer intervals of time.

From Kate Jones’s Retrieval Practice: Research and Resources for Every Classroom: Among many useful strategies, Kate recommends something she calls a “retrieval grid.” Each grid features a different question, which is then color coded by how long ago students first learned that topic or concept. As Kate shares in her book, her students enjoy the challenge of trying to complete the gird, especially the darkest squares (which require them to recall information from further back).

Key Takeaways

1. We define learning as a process that results in a change(s) to long-term memory.

2. Retrieval Practice is “the process of causing students to recall information they’ve learned after a strategic delay.”

3. We begin forgetting something as soon as we learn it. Regular retrieval is the best way to curb this process.

4. Retrieval Practice works best when it’s low stakes. Use it as a tool to help students better remember what they are learning, not to measure what they did learn.

5. Spacing out Retrieval Practice helps students remember more, for longer, and with less practice. But don’t wait too long: ask students to recall after a little forgetting.

6. Retrieval Practice should be effortful, causing students to recall knowledge without the help of a memory aid. It should not be “open book.”

The post Hernandez: The Time is Now for Understanding Learning, Forgetting & Retrieval Practice appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 9, 2021

New Video: Jill Murray Models What To Do, Anonymous Individual Correction and Radar

Schools and classrooms are opening across the country in the coming weeks and amidst the uncertainty about masks and the like, there’s the enduring question that takes on double-weight after pandemic disruptions: How do we create vibrant positive and productive classroom cultures that harvest attention and help students succeed?

With that in mind I’m happy to share this short but instructive video of Jill Murray, who teaches at Sacred Heart Elementary, part of Partnership Schools, which runs parochial schools in NYC and Cleveland.

In the clip you can see Jill quite beautifully link three foundational techniques that make for successful classroom cultures.

1) She gives a very clear What to Do directions. One of the most common reasons why students are not engaged productively in classroom tasks is because our directions aren’t clear. But Jill’s are direct and clear. “Move your board to the side,” she says in a warm voice, identifying a concrete and observable action. And then she doesn’t say anything else. If she did she might distract students from the task or dilute their focus. As students follow the direction she adds: “And then all eyes on me.” Again, concrete and observable. One thing at a time.

2) She then scans for follow-through after the direction. Prevention is always better than correction and one reason students might not follow through on a clear direction is that the teacher doesn’t communicate that it’s important to do so by looking to see whether students have or not. But you can see Jill here lift her chin slightly and scan back and forth across the room to show that she cares and notices whether students are doing what’s required of them. This makes it far more likely that they will. Now and n the future.

3) Turns out a couple of students are a bit slow to follow-through. It’s important to notice this and to set higher expectations but in a humane and thoughtful way. So Jill uses an Anonymous Individual Correction. “Waiting for two…” she says, making it clear that a couple of students need to move a bit faster but preserving their anonymity. They know she’s aware that they need to work harder to keep up but also that she is keeping that struggle private. She’s setting expectations without calling anyone out. When the students catch up she says ‘thank you,’ which expresses civility and cordiality but also makes it clear that the students have, in fact, successfully caught up. Now everyone is with her and away they go.

It’s lovely work. So simple and so elegant and so effective in making sure that every student stays with the class, expectations remain high and learning time is honored.

The post New Video: Jill Murray Models What To Do, Anonymous Individual Correction and Radar appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

August 6, 2021

Building a Culture of Error: A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt

Here’s another excerpt from the soon-to-be-released TLAC 3.0. The topic is building a Culture of Error and this portion deals with how this technique includes but is also broader than establishing psychological safety.

In a recent article about his development as a musician, the pianist Jeremy Denk observed a hidden challenge of teaching and learning: “While the teacher is trying to . . . discover what is working, the student is in some ways trying to elude discovery, disguising weaknesses in order to seem better than she is.”

His observation is a reminder: If the goal of Checking for Understanding is to bridge the gap between I taught it and they learned it, that goal is far easier to accomplish if students want us to find the gap, if they are willing to share information about errors and misunderstandings—and far harder if they seek to prevent us from discovering them.

Left to their natural inclinations, learners will often lean toward the latter. Out of pride or anxiety, sometimes out of appreciation for us as teachers—they don’t want us to feel like we haven’t served them well—students will often seek to “elude discovery” unless we build cultures that socialize them to think differently about mistakes.

A classroom that has such a culture has what I call a Culture of Error. Those teachers who are most able to diagnose and address errors quickly make Check for Understanding (CFU) a shared endeavor between themselves and their students. From the moment students arrive, they work to shape their perception of what it means to make a mistake, pushing them to think of “wrong” as a first, positive, and often critical step toward getting it “right,” socializing them to acknowledge and share mistakes without defensiveness, with interest or fascination even, or possibly relief—help

is on the way!

The term “psychological safety” is often used to describe a setting in which participants are risk-tolerant. Certainly psychological safety is a critical part of a classroom with a Culture of Error, but I would argue that the latter term goes farther: it includes both psychological safety—feelings of mutual trust and respect and comfort in taking intellectual risks—and appreciation, perhaps even enjoyment, for the insight that studying mistakes can reveal. In a classroom with a Culture of Error, students feel safe if they make a mistake, there is a notable lack of defensiveness, and they find the study of what went wrong interesting and valuable.

You can see this happening in the video Denarius Frazier: Remainder. Gathering data through Active Observation (technique 9), he spots a consistent error. As students seek to divide polynomials they struggle to find the remainder. Fagan is one of many students who have made the mistake. Denarius takes her paper and projects it to the class so they can study it. His treatment of this moment is critical. There is immense value in studying mistakes like this if teachers can make it feel psychologically safe. Unfortunately, it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to picture the moment going wrong—badly wrong. The student could feel hurt, offended, or chastened. Her classmates could snicker. Perhaps you are imagining the phone call that evening: Let me see if I have this right, Mr. Frazier. You projected my daughter’s mistakes on the overhead for everyone to see?

But in Denarius’s hands, the moment proceeds beautifully and, more importantly, as if it were the most normal thing in the world to acknowledge a mistake and study it. How does he do it?

First, notice his tone. Denarius is emotionally constant. He is calm and steady. There’s no suggestion of blame. He sounds no different whether he is talking about success or struggle. Next, he uses group-oriented language to make it clear that the issue they’ll study is common among the class. “On a few of our papers, I’m noticing that we’re getting an incorrect remainder . . .” he says. The mistake is ours; it’s relevant to and reflective of the group, not just the individual. There’s no feeling that Fagan has been singled out.

Another important characteristic of classrooms like Denarius’s has to do with how error itself is dealt with. It is best captured in a phrase math teacher Bob Zimmerli uses in the video Culture of Error Montage: “I’m so glad I saw that mistake,” he tells his students. “It’s going to help me to help you.” His phrase suggests that the error is a good thing. He calls the class to attention to show it is a worthy and serious topic, but he simultaneously normalizes the error through tone and word choice.

This is different from—the opposite of in many ways—pretending it is not really an error. Notice that Bob explicitly identifies the mistake as a mistake. His goal is to make it feel normal and natural, not to minimize the degree to which students felt they had erred.

I mention this because sometimes teachers struggle with this distinction. In workshops we occasionally ask teachers to write phrases that they could use to express to students the idea that it is normal and useful to be wrong. They sometimes suggest responses like “Well, that’s one way you could do it,” or “Let’s talk about some other ways,” or “OK, maybe. Good thinking!” These phrases blur the line between correct and incorrect or avoid telling students they are wrong. There are, of course, times when it’s useful to say, “Well, there’s no right answer, but let’s consider other options.” But that is a very different moment from the one in which a teacher should say something like “I can see why you’d think that but you’re wrong, and the reasons why are really interesting,” or “A lot of people make that mistake because it seems so logical, but let’s take look at why it’s wrong.”

You can see another example of this in the Culture of Error Montage. Mathew Gray, like Denarius, is sharing a mistake—this one made by a student named Elias (a Show Call, technique 13). He notes this right away: “Elias has made a mistake,” but he notes that this is not a surprise because he made the question difficult and that others have made the mistake as well. Then crucially he adds, “It’s a mistake that I made when I first read the poem.” He is the teacher and he, too, has struggled to understand. What could more fully contradict the idea that being an expert somehow means that one does not make mistakes? The idea is not to forestall defensiveness by making students believe they are correct, in other words, but to forestall defensiveness by helping students to see that the experience of making a mistake is normal and valuable.

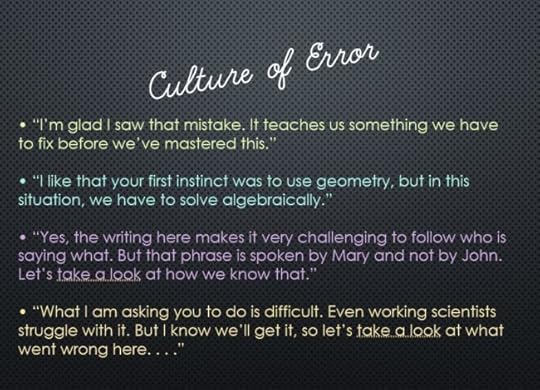

Here are some other phrases that do that:

• “I’m glad I saw that mistake. It teaches us something we have to fix before we’ve mastered this.”

• “I like that your first instinct was to use geometry, but in this situation, we have to solve algebraically.”

• “Yes, the writing here makes it very challenging to follow who is saying what. But that phrase is spoken by Mary and not by John. Let’s take a look at how we know that.”

• “What I am asking you to do is difficult. Even working scientists struggle with it. But I know we’ll get it, so let’s take a look at what went wrong here. . . .”

It’s worth noting that the statements are different. The first flips student expectation; the teacher is glad to have seen the mistake. The second gives credit to the student’s understanding of the mathematical principles—but makes it clear that she’s come up with the right answer for a different setting. The third and fourth acknowledge that the task is not the sort of thing you try just once and get right. They normalize struggle. As this Culture of Error is created, students become more likely to want to expose their mistakes. This shift from defensiveness or denial to openness is critical. As a teacher you can now spend less time and energy hunting for mistakes and more time learning from them. Similarly, if the goal is for students to learn to self-correct—to find and address errors on their own—becoming comfortable acknowledging mistakes is a critical step forward.

The post Building a Culture of Error: A TLAC 3.0 Excerpt appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers