Doug Lemov's Blog, page 4

August 5, 2024

Introducing Our School Culture Curriculum for High School Students

A sample page from the curriculum…

Are you looking for a curriculum to help students engage more positively in school and to support students’ character development? Look no further! We are thrilled to announce the release of our School Culture Curriculum for high school students!

Our high school curriculum can be used proactively in an advisory or homeroom block, responsively to address specific student needs when classroom behavior is counter-productive, or in one-on-one or group sessions aligned with student support services. Our student-facing lessons cover a range of important topics including Exploring Emotions, Goal Setting, Succeeding Academically, and more.

The School Culture Curriculum for high school students includes six unique chapters that aim to:

Help students reflect on challenging situations, analyze their actions, and learn replacement behaviors for counterproductive actions.Foster an understanding of how students’ actions impact both themselves and others.Proactively teach virtues and values to support character development among students.Cultivate critical thinking, writing skills, and character development through meticulously curated activities organized by topic.

One of the key features of our curriculum is its focus on teaching students as part of behavior change. Students engage constantly through reading and writing, enhancing their knowledge—for instance, learning how slowing down decision-making can reduce impulsiveness. This allows them to have richer discussions and a deeper understanding of the challenges of being a teenager. Just watch Tiana Solis, a Guidance Counselor at Achievers Early College Prep Charter School in Trenton, New Jersey. Tiana is using a lesson from our “Succeeding Academically” chapter titled “How Do We Learn” with a small group of 9th-grade students she sees monthly.

Tiana incorporates various means of participation to engage her students. As students engage in Everybody Writes, Tiana circulates and actively observes what they are writing. She then prompts students to turn and talk, even partnering up with a student who is without a partner. After the turn and talk she invites students into the conversion using cold call, encouraging students to share their thoughts and ideas.

We are excited for you to experience the School Culture Curriculum for high school students and believe that it will support you in your efforts to impact students’ character development and academic success. Click the link below to get access to a subscription today!

Tiana incorporates various means of participation to engage her students. As students engage in Everybody Writes, Tiana circulates and actively observes what they are writing. She then prompts students to turn and talk, even partnering up with a student who is without a partner. After the turn and talk she invites students into the conversion using cold call, encouraging students to share their thoughts and ideas.

We are excited for you to experience the School Culture Curriculum for high school students and believe that it will support you in your efforts to impact students’ character development and academic success. “Click here to get access to a subscription today!”

(By the way, if you’re interested in the Middle School version, you can find it here.)

The post Introducing Our School Culture Curriculum for High School Students appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 29, 2024

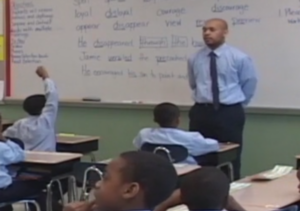

Scott Wells Models the Foundations of a Successful Cold Call

In our workshops on Cold Call we often provide a summary of four key things teachers can do while Cold Calling to ensure that the experience is positive, productive and successful.

They are:

1) Preparation. Giving students time to prepare answers before a Cold Call helps them to develop quality ideas and often rehearse them in a small group before sharing them with the large group. Ideally then, letting students write their ideas first (Stop and Jot) or Turn and Talk with a classmate or both is a great way to ensure both success (from a student POV) and higher quality answers.

2) Honor the work. Using the preparation time to look for useful answers and often narrating that that Cold Call is a result of quality work during the preparation ensures that you get quality answers that make students feel successful. We call it “hunting not fishing” when a teacher circulating during the Stop and Jot Turn and Talk and finds answers that are ideal to start with- either because they are interesting or because they allow the teacher to bring a student who might be quieter into the conversation. You can often make this process legible by saying, “Juan, i love what you wrote about X. Can you tell us a bit about that?” Now the student feels like the Cold Call is an honor.

3) Formative language. Cold Calling a student with language that reminds him or her that he or she doesn’t need to be perfect is another way to lower the stakes. “Juan, can you get us started talking about…” implies to Juan that his ideas don’t have to be perfect. And it reminds the rest of the class that you’ll probably ask them to develop Juan’s initial idea. (And tells Juan that when they do so this is normal and what you expected t have happen rather than a judgment on his answer.

4) Post-answer referencing. One of the most important signals to a student that their contribution was valuable to his or her peers is whether they talk about it afterwards. Peer to peer signals of interest are crucial to academic culture. Sure you can say: “Interesting, Juan. Thank you.” But even better is if Juan hears his peer talk with interest about what he said and show that they thought it was important.

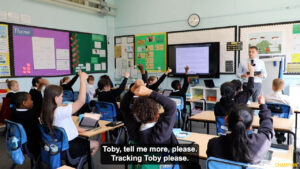

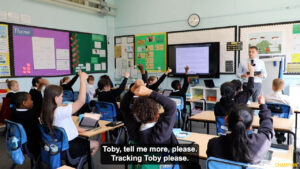

You can see all of those elements in this excellent example from Scott Wells’ classroom at Goldsmith Primary Academy in Walsall, England.

Scott”s using our Reading Reconsidered curriculum and his students have read a nonfiction article about the medical condition that afflicts the narrator of Wonder, August. He wants his students to weigh in: Would August agree or disagree with this statement?

First, he gives them time to write out their thoughts in a quick Stop and Jot. Then they Turn and Talk. By now everyone has thought through the question twice. And they’ve heard someone else’s answer. Preparation. Check.

During the Turn and Talk you can see Scott linger by one of his students, Lucas, whose a bit on the quiet side. Scott notices he has a strong answer. It’s an ideal time to invite him into the conversation. Honor the work. Check.

“Lucas, Start us off please…” Scott says. Formative language. Check.

As Lucas speaks his classmates are attentive and appreciative (see: Habits of Attention).

Then Scott asks the class to “agree, disagree or build.” They show their intention with a hand signal and Lucas can see that lots of students agree with him and others want to add on and “build” off of his thinking. (See image below).

Toby and Nathan weight in extensively, showing Lucas that his comments were worthwhile to them. Post-answer referencing. Check.

Note that while Toby has raised his hand, Nathan has not. Another Cold Call. But note the formative language: “Nathan, what are your thoughts?” It’s inviting and open and shows appreciation for Nathan. And it’s a hard question to get wrong. Just share your thoughts.

One of the key pieces of research on Cold Calling (Dallimore et al. 2013) found that “students in classes with high cold-calling answer more voluntary questions than those in classes with low cold-calling.” That is, when you are cold called and feel successful you find it’s not so scary to participate. And you come to believe you are important to the class, perhaps.

A good Cold Call like Scott’s makes the classroom more inclusive.

The post Scott Wells Models the Foundations of a Successful Cold Call appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 23, 2024

Using Writing in The (Reading) Classroom–The Amazing Success of First Year Teacher Emily Fleming

Great task; great directions; great results

Last week I had the pleasure of joining Kristen McQuillan, Natalie Wexler and Julia Cooper on a webinar sponsored by the Knowledge Matters campaign. Topic: The critical role of writing in reading comprehension.

You can watch the webinar here: https://knowledgematterscampaign.org/...

Meanwhile I thought I’d share a lovely video of a teacher using writing in really dynamic and effective ways in the classroom. And as if that’s not exciting enough the video is of a teacher completing her very first year in the classroom! It’s definitely inspiring.

The teacher is Emily Fleming who teaches year 4 (5th grade for us) at Goldsmith’s Primary Academy in Walsall, England. FWIW the school has some of the highest levels of economic deprivation in England among it’s students.

The first thing you might observe is when Emily’s students write: In the midst of reading. Her writing is, as I discussed on the webinar, frequent and formative. Her students write multiple times, in the midst of reading and thinking about text, with the purpose of discovery. Formative writing is, to my team, writing where students use the experience to discover what they think more clearly, rather than to explain or justify what they already know.

Another key aspect of the writing here is that it comes before student discussion. This has a powerful effect on the discussion that comes after. Students are eager to participate and have lots to say because they have all had time to think deeply about the question. Writing about it is more effortful than just talking about it… this creates desirable difficulty which facilitates learning and memory. But it also incentivizes and democratizes participation in the discussion that comes after. You can see how it effects students in watching their reaction to the turn and talk. It literally crackles to life.

Notice also how brilliantly Emily’s students are able to talk to instead of past one another. They constantly make reference to previous speakers and build off of their ideas. One reason they do this so well is that Emily has installed Habits of Discussion. She has taught them how to make a comment that connects to those of previous speakers. But another reason is because they have all written their ideas down. Now their working memory is free to actually listen rather than to sit and rehearse, while a classmate is talking, what they wanted to say so they don’t forget it. If we want students to listen, letting them write down their ideas frees their working memory to do this.

Next you’ll notice that while students are discussing, Emily is tracking the conversation in a discussion box. This discussion box is both on the front board and on their tablets. They are mirror images of each other. So Emily is modeling the sort of note-taking she wants her pupils to do.

But she’s also tracking the key ideas from the discussion because she wants her students to do more than just have a lovely and mutually supportive conversation. She wants them to use the discussion to generate ideas to revise and improve their writing.

One of the biggest benefits of shorter writing prompts is that we can have students revise and improve them right away-either incorporating new ideas from peers, as Emily does here, or based on feedback, much as Emily’s colleague at Goldsmith’s, Scott Wells does here:

Write. Study. Point out ways to get better. Rewrite and apply.

It’s pretty amazing stuff.

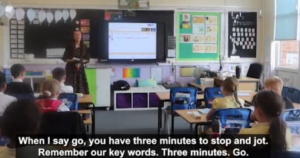

One last point. One thing that surely explains Emily’s incredible success as a first year teacher is how good she is at something we call the What To Do Cycle: Give a clear and observable direction. Scan to see whether students do it and let them see you scanning so they know it matters. Positively reinforce to let students know you see and care when they do the right thing. Correct as necessary- and as non-invasively as possible.

Again and again Emily does this with aplomb, as in, “When I say go, you have three minutes to stop and jot. Remember our key words. Three minutes. Go!”

In addition to all the other ways having this level of happy productiveness among students makes her classroom better, it means that when she sends them off to write, everyone’s pencil is moving within seconds. When she asks them to be writing everyone–every single kid–is writing. Almost right away.

So: some great examples of how to sue writing in the classroom, especially to support reading and a really inspiring portrait of a first year teach on the road to success!

The post Using Writing in The (Reading) Classroom–The Amazing Success of First Year Teacher Emily Fleming appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 13, 2024

Better Questioning for Athletes Starts with Clear Principles of Play

I’m prepping this weekend to narrate the audiobook version of The Coach’s Guide to Teaching… which basically means reading my own book. Obviously that means noticing a lot of small things I’d like to change. But also noticing some passages that, as I learn more, I see even more value in.

Here’s one, from the chapter on decision-making. It starts with the observation that in a group invasion game players should be familiar with either a game model or a set of principles of play that describe what we are trying to accomplish. I made some light edits to it to improve it’s clarity:

Once players know their principles of play [or the elements of a clear game model]… they can be used to make questioning more efficient and more focused on solving specific problems.

For example, let’s say a U16 team has divided its principles of play into four parts. They have three principles for transition to offense (having just won the ball):

■ Play immediately away from pressure

■ Spread the field—fast (to stretch the defense)

■ Find numerical advantage in as few passes as possible

A coach could then use these principles to help players make and understand effective decisions during training with short sequences of questioning like this:

Pause. Boys, we’ve just won the ball. What’s our first principle in transition?“Play away from pressure.”Ok. So Carlos has won the ball for us. Where’s the pressure.From Kevin and Paul.So a good first pass would be?To Matty?Because?It’s away from pressure.And Matty what are you looking for when you get it?Play where we’ve got numbers up.Good. Let’s see if we can do that. Play again from Carlos. Go!

Or:

Pause. Boys, we’ve just won the ball. What’s our first principle in transition?“Play away from pressure.”Ok but what about those of us who don’t have the ball?“Stretch the defense”So Matty and Jose what could your movement look like here.[They model movements to create width and depth.]Ok. Now we’re ready for transition. Play!Or

What phase are we in, Byron?We just won the ball.OK, so assess our decision as a team there.We sort of played back into pressure.OK, what’s a way to fix that?Or:

Our first principle is to play away from pressure. Look at how we were positioned. Why were we unable to accomplish that goal?

The key here is that principles of play make questioning productive and efficient because they reduce guessing.

If I did not have principles of play and I said, “We just won the ball, what do we want to do here?” players would likely guess (and guess wrong) which wastes time and dilutes focus from the real problem-solving of figuring out execution.

Another way of thinking about principles is that they shift the emphasis of player thinking from what to do to how to do it.

Some coaches may not like this. The idea of allowing players to discover principles has many advocates. And I think there is legitimacy to allowing players to occasionally derive principles for themselves.

But generally speaking, the intellectual challenges of the game have more to do with implementing a shared idea once you know it than deriving the idea itself.

We know we want to press. The whole team is pressing. I don’t want my players to derive a new defending strategy or to define a different role for themselves within the press.

The problem-solving I want is “How do I react when I am pressing and the opposing goalkeeper is good with the ball at his feet or when my own teammate reacts slowly?”

It may be useful to spend 30 minutes having players “discover” that they should play away from pressure but really learning how to play away from pressure under a variety of circumstances is a more productive.

Having shared principles accelerates that process.

The post Better Questioning for Athletes Starts with Clear Principles of Play appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

July 8, 2024

Advocacy Partnerships: Stories of Growth and Impact Part II

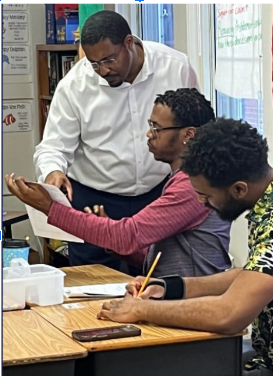

Our team’s extensive work in the education sector involves several advocacy partnerships—organizations we work with simply because we believe in their mission and purpose. One of the longest standing partnerships is with Man Up Memphis. In this blog post, Director of Advocacy and Partnerships, Brittany Hargrove, provides an update on what we’ve learned supporting their work in attracting and, more germanely, sustaining men of color in the teaching profession.

The education sector continues to face a significant challenge: between February 2020 and May 2022, the Wall Street Journal reported that more than 300,000 public school teachers and other education-related staff left their jobs citing heavy workloads, staff shortages, safety issues, low salaries, and burnout.

For the past few years, schools across the country facing staffing shortages and have worked to attract and retain exceptional educators, especially educators of color. Through our advocacy partnerships with Man Up Memphis, National Fellowship for Black and Latino Male Educators, and Teach Brother Teach, we’ve tried to study and better understand how schools were not only able to attract educators of color, but what support, including mentoring and training, is necessary for educators of color to thrive in their school communities.

One partner we’re excited to highlight for their outstanding support for new and novice male educators of color is Man Up Memphis. They are a shining example of what’s possible when male educators of color are provided opportunities to develop their capacity in a supportive and responsive school community. During the 2022-2023 school year, an impressive 92% of Man Up Memphis Fellows were retained in their roles. What’s driving this high retention rate? It’s the sense of connection and belonging that the Fellows experience. Dr. Patrick Washington, founder and CEO of Man Up Memphis, reflects on the transformation he has seen from Fellows, saying, “the belief system is changing in these guys. Brothers are walking different, moving different, winning again.”

Man Up Memphis excels in fostering a supportive environment, especially for teachers and leaders new to their roles, that goes well-beyond achieving an increase in representation of educators of color in schools. Their programming is grounded in the belief that educators of color must be positioned to develop their knowledge and competencies so they can impact change and outcomes within the school communities they serve. Core to Man Up’s mission is the belief that every child must have access to an exceptional teacher and leader, and investing in educators of color must be part of that mission. Director of Teaching and Learning at Man Up Memphis, Camile Melton Brown and fellow coaches Jonathan Humphrey, Vaughn Thompson, and Mike Brown, play a crucial role in this success. With the support from Managing Director Sarah Isenhart and Director of External Partnerships, Nicole Lytle, they all ensure that Fellows feel celebrated and supported by maintaining regular communication, acknowledging their achievements, and being readily available for any needs. This approach has resulted in a strong sense of community and drive among the Fellows.

Man Up Memphis excels in fostering a supportive environment, especially for teachers and leaders new to their roles, that goes well-beyond achieving an increase in representation of educators of color in schools. Their programming is grounded in the belief that educators of color must be positioned to develop their knowledge and competencies so they can impact change and outcomes within the school communities they serve. Core to Man Up’s mission is the belief that every child must have access to an exceptional teacher and leader, and investing in educators of color must be part of that mission. Director of Teaching and Learning at Man Up Memphis, Camile Melton Brown and fellow coaches Jonathan Humphrey, Vaughn Thompson, and Mike Brown, play a crucial role in this success. With the support from Managing Director Sarah Isenhart and Director of External Partnerships, Nicole Lytle, they all ensure that Fellows feel celebrated and supported by maintaining regular communication, acknowledging their achievements, and being readily available for any needs. This approach has resulted in a strong sense of community and drive among the Fellows.

When we’ve interviewed and surveyed Man Up fellows on what conditions or factors made it likely they would remain within their school community, a few common themes emerged. First, fellows reported feeling most successful and likely to stay when they were provided consistent opportunities for professional learning, including ongoing PD and feedback, in core competencies that helped them impact student learning.

Second, many fellows, especially in their first year of teaching, highlighted a desire to learn and grow in an environment that felt safe, nurturing, and accountable. Teaching is hard and school leaders who made it safe to make mistakes in practice, encouraged fellows to ask for support, and remained consistent in their efforts to invest in their development via impactful professional learning, were more likely to retain their fellows.

And finally, many responses from fellows reminded us that we all have an inherent desire to belong to a group or community that values the assets we contribute to it. A sense of belonging, or feeling a deep connection to their work, colleagues, and the larger school community, was a primary factor cited for returning to their school communities. Fellows want to remain in school communities where they are valued, welcomed, and seen as an essential part of the community. The factors we’ve outlined above are key for increasing job satisfaction, and the likelihood educators of color will experience professional growth that best positions them to impact key performance indicators in their schools for years to come.

Actions Schools Can Take

Based on our learning from Man Up Memphis, here are some replicable actions schools can consider taking to build or enhance connection and belonging among their staff, thereby improving retention:

Foster a Supportive Community: Create a culture where all staff feel celebrated and supported. Regularly acknowledge achievements, both big and small, and maintain open lines of communication. Use emails, newsletters, and meetings to highlight successes and milestones. This might take place publicly at a PLC or PD or perhaps goes out in weekly communication to your school team.Provide Professional Development Opportunities: Offer regular, meaningful professional development sessions, ensure these sessions address their real needs and challenges. Consider uplifting bright spots on your staff that are meeting and exceeding on the strategic priorities of your school. Promote Connection and Collaboration: Encourage collaboration among staff. Create opportunities for teachers to work together during school hours. Uplift the voices and best practices of staff you collaborate regularly. Ensure Accessibility of Leadership: Make sure school leaders are approachable and available. Being just a phone call or text away can make a significant difference in how supported staff feel.Address Workload and Mental Health: Take proactive steps to manage workloads and support the mental health of your staff. This could include hiring additional support staff, offering wellness programs, and creating a positive work environment.

By implementing these actions, schools can create a nurturing environment where educators feel connected, supported, and valued. This, in turn, will help retain dedicated and passionate educators, ensuring a brighter future for our students.

The post Advocacy Partnerships: Stories of Growth and Impact Part II appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 22, 2024

A Quiet Presence Montage–And How To Find Out More

Help students listen by going low and slow with your voice and adopting a formal posture.

“Quiet Presence” is the idea that going lower and slower with your voice is the best way to help students focus optimally, especially in those moments when their attention is just beginning to fray.

In some ways that’s the opposite of what you might expect. It’s a common mistake in the early years of teaching to get louder and faster to demand attention. Often that increases the potential for student distraction–students might wonder if you are getting anxious and why; a few might find the indication that you are as a bit of a challenge; in doing so you often inadvertently show a willingness to talk over a certain amount of student noise.

Quiet Presence is the skill of sustaining students focus on your directions by getting lower, quieter, slower. A master teacher will often shift tones very clearly so students “hear” the difference. They will often adopt a more formal pose. And then when students have responded they’ll get on with the teaching.

You can see those things playing out in this montage of teachers demonstrating Quiet Presence both correctively (at the first hints of distraction) or preventatively (as a habit to ensure that it’s easy for students to attend to directions in the first place.

One of the things we love about this clip is how each teacher does it a bit differently, but that the themes endure: low and slow; shift your tone observably; match that to a shift to a more formal physical pose. Then when students respond get on with the teaching.

We’ll be talking about skills like Quiet Presence and many others–with LOTS more great video!–at our upcoming workshop in Bristol England on June 24 and 25.

Registration and details here:

https://www.olympustrust.co.uk/News/Teach-Like-a-Champion-Conferences-24-25-June-2024/

Thanks to Olympus Trust for co-sponsoring.

The post A Quiet Presence Montage–And How To Find Out More appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 17, 2024

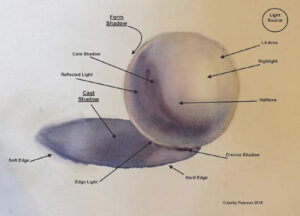

Alexander Lisman Checks for Understanding in his Visual Arts Class

Just because you taught it does not mean they learned it…

We’ve had quite a few requests lately for examples of Teach Like a Champion techniques in Arts classes so it’s my pleasure to share this clip of Eagle Ridge Academy (Brighton, Colorado) art teacher Alexander Lisman’s Checking for Understanding in which he uses Active Observation and intentional feedback.

Let’s set the scene. Alexander’s students are working on drawings… or, well, that’s how a lot of teachers might have framed it, even to students. And if the objective is an activity–to ‘complete a drawing’–it’s hard to give feedback that teaches much. “Good job.” “I like it.” Keep going.” Those are lovely things but they don’t help students improve their skills. Much better to teach a technique and then help students see how to apply it as they create. The objectives here are clear.

In fact what we love most is how Alexander tells his students the three key things he’s looking for as he walks around and gives feedback:

he’s looking at the whether their line drawing correctly includes a horizon line and a vanishing point;he’s looking at correct pencil usage, using a range of pencils properly to create shadow and line;he’s looking at shading, at a combination of form shadow, cast shadow and highlights.

We love the way he spells them out to students: Here’s what I’ll be looking for. This directs their attention as they draw and causes them to focus on the skills even before he gives any feedback. Not only is his class now an exercise in focused mastery of technique, but Alexander has created a structure that reminds himself of what to give students feedback on.

And we love how disciplined he is to look for those things!

As he walks around you’ll notice how all of his feedback is about the things he’s been teaching. You can tell because my colleague John Costello color coded the subtitles (brilliant!) to show how the feedback Alexander gives aligns to his learning objectives.

This not only helps his students to focus on intentionally applying the things they’ve learned but it causes HIM to pay attention to them and to be more aware of their mastery of those skills. In fact just after this video ended he stopped class to suggest that students draw an arrow on their paper to remind them of the direction of light so their shadowing was more effective.

So much of his feedback is positive but it’s not just vaguely positive–good job–but tells them what they did well so they understand it: your deep shadows are really dark. Nice job. He aligns his feedback and his praise clearly to the objective.

I should also note that today’s clip is an example of a growing aspect of our work — helping schools capture and study, via video, examples of how they implement their PD and coaching priorities. In collaboration with Eagle Ridge , our Consulting & Partnership team led by Hilary Lewis, Rob Richard, and Jen Rugani spend multiple days sharing techniques and helping the school tape and study their work. This clip is just one of many highlights.

The post Alexander Lisman Checks for Understanding in his Visual Arts Class appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 16, 2024

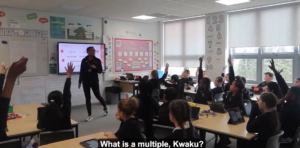

How Charlotte Pottinger Uses Retrieval Practice and Top Flight Means of Participation to Start Class

Maths with Ms. Pottinger: Everybody is all-in!

In this post, I’m going to share a video of Charlotte Pottinger’s classroom at Rivers Primary Academy in Walsall. I’ve been looking forward to sharing it because it’s so lovely on so many levels.

I’m going to call it a Retrieval Practice clip because that’s her main purpose–to start her Maths lesson by making sure students build their long-term memory of key terms and ideas. But there’s so much else to appreciate here… especially Charlotte’s brilliant Means of Participation–her clarity with students about how they should answer each question, her intentionality about which Means of Participation she uses, the degree to which she’s made each of those a well-installed routine, and how familiarity with those routines allows Charlotte’s students to participate with energy, verve and confidence.

Here’s the clip:

Some notes:

Charlotte starts class with her first question right away. “Ok, let’s refresh our memories and go through some of our key star words,” she says, cueing her students that they will be doing Retrieval Practice. Then she adds: “Talk to your partner. What is a multiple?”

Notice that she signals to them deliberately before she asks the question how she’ll want them to answer it. Adam Boxer calls this frontloading. A well-oiled routine clearly signaled. Result: the room crackles to life, creating a Norm Signal… every student in the room showing all the other students how engaged and eager they are to be involved. “Norms are the unwritten rules that govern the behaviour and attitudes of a group(such as a society or school). They are so powerful that they tend to override more formal rules or policies,” Peps McCrea has written. You can see here how early magnification of the norm of engaged positive participation cascades through Charlotte’s class.

At :23 you can see the response. Every hand eagerly in the air! If Charlotte has one challenge in this clip, it’s that her pupils are all so eager to raise their hands that Cold Calling might be tricky.

I also love her Turn and Talk at :51. Keaton has identified that an integer is a positive or negative [whole] number. Charlotte asks: “What does he mean by positive? If he’s talking about a positive number, he means what? [Pause] Tell you partner.”

She might have said, “If I am talking about a positive number what do I mean?” but her phrasing gives Keaton a lovely bit of credit for his previous answer. The slight pause before the Turn and Talk gives students enough wait time to think of the answer so that when she cues the Turn and Talk, the room again practically explodes.

But then cleverly she keeps her Turn and Talk very short! She’s getting data that students likely know the answer. The purpose is to get them to rehearse it. But it’s a short answer. Once they’ve done that, the purpose of the Turn and Talk has been achieved. If she let it go too long students would have talked it out already and would have less energy for answering in the whole group after. A Turn and Talk that is a little too short is better than one that is a little too long. It causes students to practice always being fully engaged during Turn and Talks. And it keeps the class pace-y and engaging. That feeling makes students feel happy and motivated at the start of class.

The class is off to a flying start but at 1:10 Charlotte slows it down slightly, switching her Means of Participation from Turn and Talk to Everybody Writes. Being able to define a fraction takes a little more thought. And it’s really important to the upcoming lesson. Asking students to write it 1) ensures that everyone gets the benefit of the retrieval–they all have to answer the question–and 2) causes a bit more desirable difficulty. That is, student work a little harder to get the definition into writing and this will cause them to remember it better.

Note again how well-oiled the routine of brief episodes of formative writing is. Her name for it–Silent Solo–reminds them of the familiar expectations for how to complete the task.

One more benefit of writing: Charlotte circulates and quickly spots a few students whose answers need elaboration or clarity. You can see her doing this at 1:38 in the video.

Freddie’s answer is lovely… and almost right. But Charlotte has prepared by writing down exactly what answer she hopes she’ll get–it’s on her clipboard!–and so she quickly spots that, as she puts it, Freddie has the right words in the wrong order. Instead of “rounding up” and telling Freddie what the answer might have been, she goes back to him to let him improve the answer himself. This is called “Right is Right” and among other things it lets Freddie feel fully successful.

As the clip ends you can see Charlotte is beginning to transition from Retrieval Practice to a new activity–they are starting to learn about hundreds–but the energetic positive norms she set while causing every student to review key concepts has carried over into the heart of her lesson.

Maybe that’s the biggest takeaway: how happy and fully engaged the students as a result of her careful planning and strong routines. They are all-in for learning.

The post How Charlotte Pottinger Uses Retrieval Practice and Top Flight Means of Participation to Start Class appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 6, 2024

Matt Lawrey and the Effort to Help Athletes Learn to Watch Better

Teaching David to watch more intentionally

A few weeks ago I spent a day at Atlanta United’s Academy with Matt Lawrey, one of my favorite coaches and talent developers.

In the afternoon we joined Will Bates, who was coaching the U15s, to experiment with a few ideas we are both interested in.

We’ve talked in the past about trying to socialize players to watch better and more intentionally so they learn more during “down times” in training.

We both think this is an untapped area for development. Consider how much time players spend watching. You are rotating three teams through an 8v8 game for example. Are the 8 players who are “off” watching what’s happening on the field? Are they watching passively or with their attention specifically tuned to things that are maximally useful? How much do they watch for the technical details and off the ball movements?

What about the players during a match? Are they watching to see what tactical decisions your team or the opponents are making or are they watching to see who wins? Are they watching actions away from the ball?

Watching presents an especially beneficial opportunity to watch and learn in those areas specifically.

So one goal was to socialize better watching habits.

We’ve also talked about using an ipad to show players themselves in practice so they could learn by watching themselves and just maybe seeing what their coaches or teammates see.

We were particularly interested in areas of the game that don’t provide “implicit feedback.” For example, you get much better implicit feedback for actions when you are on the ball. If your pass was good or your shot dangerous, you tend to know it. You can see the result. The outcome tends to reinforce what you’ve done in a mostly logical and reliable way.

But in other areas of the game the implicit feedback process is less reliable. Your movement off the ball for example: you are less likely to realize that your movement could have been sharper or created more space for a teammate. Or you might make an excellent movement but still not get the ball and therefore not know that you’d done well.

On a previous visit, then, with U17 coach Steve Covino, we’d experimented with videotaping players off the ball and gathering them to show them their movements off the ball on the ipad… asking them to evaluate the quality and timing of their movements. Could we make a relatively invisible part of players’ lives more visible to them to help them learn?

Will’s session featured significant work on defending so Matt decided to try applying these two ideas to see if he could help players see their defensive body position and movements more clearly. To learn to watch for them more in this practice and ideally in the future.

In this video Matt is standing with Dulani, who is about to take his turn in a short field transition game.

His goal is to initiate a conversation with Dulani and cause him to watch the defender who is playing the role he is about to play with more intentionality and attentiveness to key cues.

Notice how relaxed Matt’s questioning style is. How much space he leaves for Dulani to observe. How he makes it relaxed and safe. Notice also how much of the conversation is about cues—what Dulani should be looking for in other situations like these. And how much Dulani grows into the conversation. First he’s just answering Matt’s questions but soon enough he’s initiating the discussion, describing things he sees unprompted and even orienting his body to rehearse proper body position.

In the first video Matt was trying to socialize players to watch well during down time and arming them with cues.

In this next video Matt is now using an ipad to show players their own actions in an individual defending exercise. Before they play again Matt shows them their last round and asks them to analyze.

In this clip, Matt’s first question is: What do you think? This allows him to assess what Josh knows and attends to in observing defensive actions. notice how much the player, Josh, starts to spontaneously narrate what he sees. He’s narrating back each of his actions. In a couple of cases “What’s the timing of your step?” “What’d you do right after?” to help remind Josh of the key principles of defending but Josh seems to know. Still its so powerful to see himself taking the actions and succeeding. He’s building a mental model of what his body should do. Lastyl notice how fast the interaction is. Matt doesn’t belabor it. He wants Josh to see and watch attentively and then get back to playing.

In this last clip Matt is working with David.

I love this clip because you can see how deftly Matt uses the video to play the sequence David is studying over for him multiple times, slowly, repeating, letting him look at it carefully and notice details in key moments. First he orients David to look for his body positioning. After pointing out an area for improvement he asks about something David did well (timing of tackle) so he can replicate it. And then he tells him to watch again but orients his attention so he notices something he did well: “This time watch your feet.” It’s so important to use feedback to help players see what it looks like when they do things right so they keep doing it!

And then as before, David goes right back out and tries to use what he’s learned.

Thanks to Matt and Will, their players and everyone at Atlanta United!

The post Matt Lawrey and the Effort to Help Athletes Learn to Watch Better appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

May 3, 2024

More Ace Footage from Scott Wells’ Classroom

Scott and his students…

Earlier this week I posted a clip of Scott Wells of Goldsmith Primary Academy as he Checked for Understanding with his students. Justifiably, the clip got rave reviews in a recent workshop and online as well. No surprise that- you can see how sharp it is (and some of the highlights from my perspective at least) here.

Given the response, I thought I’d take the time to post a few more clips of Scott in action.

One of Scott’s strengths is his “Smart Start”: his classes swing into action right away, often with a quick writing exercise. You can see him doing that here.

Again you can see how crisp and familiar the routines for participation are in his class. This is Scott’s Smart Start from the same lesson- it’s the first task he asks students to do. At “go” they are off and running with their working memory focused on the task rather than the process.

There are a lot of consistencies between this clip and the one I previously shared. Perhaps most notably how carefully Scott circulates, reading and assessing his students’ work as he goes. Each student feels seen and knows their work is important to Scott. And Scott ends the observation with a clear sense for who understands what.

One difference between this clip and the previous one is that, here, Scott “Show Calls” one student’s work for the class to study. It’s a pretty high level task he’s asked of them to evaluate what their classmate has done well and Scott lets Toby feel his classmates’ admiration in their praise … but he also finds an example of something both Toby and other class members could do to take their writing up a notch.

By projecting a student’s writing and ensuring that it remains in view to the class as they discuss it, Scott is again leveraging a critical corollary of Cognitive Load Theory- the idea that if something we want learners to analyze disappears from view, the learners will have to use a significant portion of their working memory simply to remember it. This is called the Transient Information Effect. But when student’s analyze Toby’s work it remains in their view. They can refresh their memory of it with ease and this ensures that their analysis will be more robust and their memory of it better.

But of course Scott also ensures that their memory of the exercise will be strong by asking each student to go back and revise their original sentence based on what they’ve learned from reading Toby’s work.

Top level stuff.

But let’s move from the sublime to the (equally important) mundane.

In this next video from the same lesson, you can see that Scott’s students are always crystal clear on the task they are being asked to complete.

They follow through readily and easily so their attention is carefully focused. Building such an orderly attentive environment accelerates learning and helps students to feel more successful. And one of the ways Scott causes that to happen is by planning and preparing his directions.

His directions always describe clear and concrete specific actions for students to take. There are always a small number of steps so working memory is not overwhelmed. After he gives those directions, he is reliably attentive to telling students whether and when he sees them following through (“I can see every single pencil moving”) and when necessary gets students back on track and non-invasively and quickly as possible. So much of the positive and productive culture in Scott’s classroom, this is to say, starts with his consistent attention to the mundane and oft-overlooked art of giving super-clear directions and letting students know he sees and cares whether they follow-through on them- a concept we call the What To Do Cycle.

With a little luck there’s be more of Scott to come… one of the best things about his lesson was how much time his students spent reading aloud- building fluency and bringing the text to life. Stay tuned but for now thanks and kudos to Scott.

The post More Ace Footage from Scott Wells’ Classroom appeared first on Teach Like a Champion.

Doug Lemov's Blog

- Doug Lemov's profile

- 112 followers