Nate Silver's Blog, page 148

September 30, 2015

Chat: How Much Damage Has The Email Scandal Done To Hillary Clinton?

Our question for this week’s politics Slack chat is probably one Joe Biden and his advisers are mulling over. As always, the transcript below has been lightly edited.

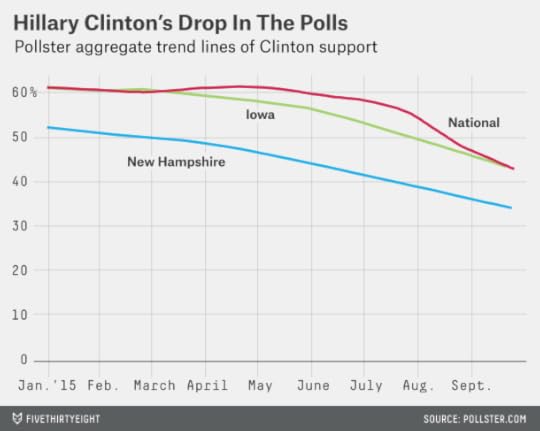

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): How much damage has the e-mail controversy done to Hillary Clinton’s candidacy? And I mean both her primary and general election prospects, but let’s start with the primary. Her polls:

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Oh god — I’ve been trying to avoid this question for six months. Because I think it’s really hard to answer.

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): I mean, let’s be real here: Clinton’s primary numbers have dropped. The horse-race numbers, as the chart indicates, show her declining. But at the same time, her favorability numbers are still pretty darn solid. And she is still cruising in the endorsement primary. No one is even close to her there, and I generally believe (based upon prior primaries) that is most predictive.

micah: Extra points to Harry for plugging our endorsement tracker.

natesilver: Wait — Harry didn’t answer the question.

hjenten-heynawl: Harry says: damage minimal in primary.

faraic (Farai Chideya, senior writer): The email controversy actually splits two ways among some people I’ve spoken with. Some likely Democratic voters view her as untrustworthy; others view her as take-no-prisoners (and no s**t). There are several nested questions with the emails. 1. How important was it that she used her own servers? (i.e., the question of security, federal policy, propriety.) 2. How has she disclosed or not disclosed the information — (the “drip, drip, drip”) of the decisions she made? And 3. What possible cross-pollination/cross-contamination of her role as secretary of state and private/Clinton Foundation life do the emails show? On that last point: here.

micah: Yeah, part of Clinton’s problem is how layered this story is. There’s a lot for opponents to play with.

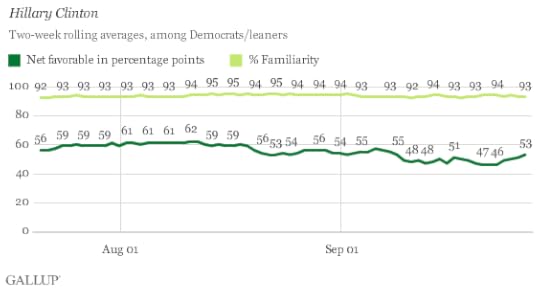

hjenten-heynawl: Let’s just look at the fact that Gallup has her net favorable at +53 among Democrats. That’s better than it was eight years ago in Gallup polling (+50). We obviously don’t know how it would look without the email scandal. But in terms of primary voters’ perceptions of her, she’s doing just as well. Which shouldn’t be surprising given that she is pretty much universally known.

micah: But, Harry, haven’t her favorables gone down?

hjenten-heynawl: This year? Sure — as she hit the campaign trail and stopped being a diplomat and started becoming a politician again. But over the last few months, Gallup has her stable.

micah: hmmm

natesilver: hmmm

hjenten-heynawl: That is among Democrats.

natesilver: On the one hand, it seems clear that the press cherry-picks bad polls for Clinton. And, furthermore, that it underappreciates how her favorability ratings have not deteriorated much with Democrats. But I’m not sure that I buy that they haven’t declined. It seems clear that they have. Even among Democrats.

hjenten-heynawl: But the question for this chat is: “Has the email scandal hurt Clinton’s chances?”

micah: (Nate still hasn’t answered that.)

natesilver: Her numbers are down. It’s a question of cause and effect. Or not even cause and effect, exactly, but what her numbers would be in a world where she didn’t have a private email server.

faraic: Articles like this one — a recent update on questions about when and how she used the server — get back to the question of whether this is a slow-drip that will hurt or one that will pass. Is it OK for me to say, “I don’t know”? I do think, in general, that she is built to withstand this type of scrutiny.

natesilver: Getting sustained negative media coverage can matter, especially when it’s reinforced by declining polls, even if voters don’t care that much about the details of the scandal itself. We’re at a phase of the election where the tone of media coverage is just about at its most important. Voters are tuning in, but only along the margins; they aren’t getting a comprehensive picture.

But can I repeat my question from before? What would her numbers be now in a world where she didn’t have a private email server?

hjenten-heynawl: I think we know the answer to this question. Knowing nothing else — nothing else — I’d have assumed she would fall back to her 2008 numbers, and those numbers have been fairly stable when she’s been in the political arena.

faraic: Nate, I’d say her favorability numbers would be 5-10 points higher — not so much from the email scandal itself but the sense of a prolonged “drip, drip” and the fatigue it provokes.

natesilver: Maybe. Or maybe the press would be focusing on the Clinton Foundation instead? Or her paid speeches? Or doing more digging into other (real or alleged) scandals?

hjenten-heynawl: Press needs a story … always does.

natesilver: So a few years ago, I developed a five-pronged “test” for whether a scandal would resonate:

Can the scandal be reduced to a one-sentence sound bite (but not easily refuted/denied with a one-sentence sound bite)?Does the scandal cut against a core element of the candidate’s brand?Does the scandal reify/reinforce/“prove” a core negative perception about the candidate, particularly one that had henceforth been difficult to articulate (but not one that has become so entrenched that little further damage can be done)?Can the scandal readily be employed by the opposition, without their looking hypocritical/petty/politically incorrect, risking retribution, or giving life to a damaging narrative?Is the media bored, and/or does the story have enough tabloid/shock value to crowd out all other stories?natesilver: It’s not especially empirical — just a way to focus the discussion a bit.

The first question is whether the scandal can be explained in a one-sentence sound bite. And I don’t think the email scandal does particularly well by that test. “Clinton maintained a private email server” is not all that sexy unto itself.

“Clinton threatened national security and/or broke the law by maintaining a private email server” is better, but less self-evident.

That’s part of why I’ve been skeptical that the details of the scandal mattered all that much to voters. It doesn’t have much sex appeal.

However.

Some of the other parts of the five-pronged test would argue for the scandal being important. In particular, No. 3: “Does the scandal reify/reinforce/‘prove’ a core negative perception about the candidate?” Also No. 2: “Does the scandal cut against a core element of the candidate’s brand?” It makes it harder for Clinton to talk about her time as secretary of state in a positive light, which could otherwise be a real strength for her.

faraic: Devil’s advocate: Couldn’t you say the sound bite is “Hillary Rodham Clinton kept classified information improperly.” Well, that’s not sexy either but … it’s an argument.

natesilver: It’s not “the president had sex with a White House intern” exactly.

faraic: Speaking of sex — I’m really going to digress here. This is a video of Lena Dunham (“Girls”) joking with Clinton about Lenny Kravitz’s “wardrobe malfunction” in an effort to be “likable.” Or millennial-friendly. It’s actually quite funny.

hjenten-heynawl: I don’t play these analyses games too well, but here’s what I do know: What I had generally expected heading into the campaign is that Clinton’s numbers would come back to where they were in 2008. Her favorable ratings have been a bit worse, but she is polling at the same level as the generic Republican (Jeb Bush), which matches up with what you’d expect given the generic presidential ballot and Obama’s approval rating.

natesilver: The email scandal could also matter if it motivates Biden to enter. Even if that reflects an overreaction on Biden’s behalf. He has to make a decision in an environment of uncertainty.

faraic: I don’t believe Biden is going in.

natesilver: I’m skeptical that Biden will run too, but it would be really helpful to Clinton right now to have a few weeks without a further revelation in the email story. And the “drip, drip, drip” nature of the story has made that difficult.

That might be a sixth prong we’ll need to add to the acid test we described earlier: Does the scandal continue to produce news, or is it one-hit-and-you’re-done, in a way that allows you to apologize and move on? (The American public can be real softies when politicians apologize for misbehavior.)

micah: OK, let’s say Clinton makes it out of the primary: Does the email stuff have a different effect in the context of a general election?

faraic: In a general election, Clinton will get the full mud-cannon blast of attacks — past and present, real and completely made up. But unlike, say, John Kerry, she may well be equipped to deal with both, Clinton’s equivalent of Kerry’s Swiftboat attack and questions that are more on-target.

I also think the email’s longest-lasting attack value would be to undermine her tenure as secretary of state.

natesilver: In a very big picture sense: News moves the polls less in the context of a general election. Voters already have a lot of information to weigh. And not that many of them are up for grabs. There’s reasonably strong reversion to the mean on the basis of the “fundamentals.” On the other hand, general elections tend to be closer than nomination races, so small changes in public opinion can potentially matter more.

hjenten-heynawl: I’m just thinking to myself, “Does this thing have the legs to go another one year and one month?”

faraic: Do we?

hjenten-heynawl: Because Clinton is likely winning this primary, and if she does, then it’s the general that matters

natesilver: I agree that if there were zero further news on the email scandal between now and next November, it might not matter very much at all by next year. Could be something like the Jeremiah Wright thing, which seemed like a HUGE deal at the time but probably didn’t hurt Obama much in the end. Once we get to the general-election phase of the campaign — if she makes it that far — we’ll see Clinton fighting back a little bit more. For one thing, she’ll have more reflexive support from Democratic elites and Democratic-leaning media outlets, some of whom are rooting for Sanders right now.

We could also see a phenomenon where Republicans are piling on Clinton in every which way, which could increase the amount of sympathy for her. I think the GOP has been pretty smart about not overplaying its hand with the email scandal so far, BTW.

tl;dr: The dynamics are pretty different in the general election than in the primaries.

faraic: Clinton certainly will not live or die politically by the email issue. But it’s definitely taking focus from her campaign. Though not as much as the Bush campaign is grappling with remaining out of the top three candidate tier …

natesilver: Yeah, every single one of the Republican candidates would trade places with Clinton right now. At least in terms of their chances of winning their party’s nomination.

hjenten-heynawl: Here’s my general thought: I think the email scandal has brought Clinton’s numbers down somewhat. It has certainly reminded the public of Clinton’s minuses faster than may have happened otherwise. But Clinton has plenty of baggage. She’s been in the public eye for 25 years. The party hasn’t abandoned her. And in this day and age of polarized politics, it would take something truly special for Clinton to be anything but a generic Democrat.

faraic: Agreed for the most part — but not “generic.” Establishment. IMHO.

natesilver: Some of the risk to Clinton is if there IS another shoe to drop. Let’s say there’s some midlevel scandal that ordinarily wouldn’t have all that much resonance, but it’s enough to get five or six news cycles’ worth of negative headlines for Clinton. In the current environment, that might be enough to trigger some panic among Democratic elites.

hjenten-heynawl: Sure, I mean if another shoe drops. … But this has been the summer of bad news for Clinton, and she is still ahead. What’s going to be the next bad news cycle? It turns out that her dislike of the amount of calories in pumpkin spice lattes hasn’t made her stop drinking them after all?

faraic: I think some of the Democratic elites are annoyed, but panic is far from the emotional state.

natesilver: Maybe it’s not so linear though, Harry?

hjenten-heynawl: You think there’s a cliff? There could be — where it just becomes too much.

natesilver: The primary is a consensus-building process, and consensus-building processes are full of feedback loops and often nonlinear. (Wow. That was a geeky sentence.)

micah: That was very Malcolm Gladwell-y. (Friend of the site.)

faraic: I think the correct form is “Gladwellian” … and the consensus candidate is still Clinton.

hjenten-heynawl: Right. Who is the consensus candidate here, though, besides Clinton?

natesilver: I know where you’re going with that: The primary could be thrown into disarray — and Clinton could wind up the winner anyway.

micah: So let’s consider the extreme case: What do you think the story would have to become for the email stuff to force Clinton out of the race?

faraic: At this point, I’m assuming all the data on the server has been secured. I may be wrong. But I think the likeliest right hook would come from something that seemed like an impropriety for the secretary of state to be doing — influence trading, for example — and not the security of the data itself.

That’s a hypothetical, BTW.

natesilver: If there’s a Sony-style hack in which highly sensitive national security information from Clinton’s email gets revealed publicly somehow, she’s presumably toast. I have no idea whether the chances of that are 0.2 percent or 2 percent or 20 percent.

hjenten-heynawl: I can only say that more needs to come out. This alone won’t do it.

micah: To close, Nate, answer the question that we started with: “How much damage has the e-mail controversy done to Hillary Clinton’s candidacy?”

natesilver: It’s hard to know. Very probably not as much as the media consensus holds, especially if you account for the fact that they’d undoubtedly find other negative Clinton stories to write about. The incentives to create a dramatic Democratic race are really high.

However, I don’t think Clinton is invincible.

September 28, 2015

Republicans Were More United Than Ever Under John Boehner

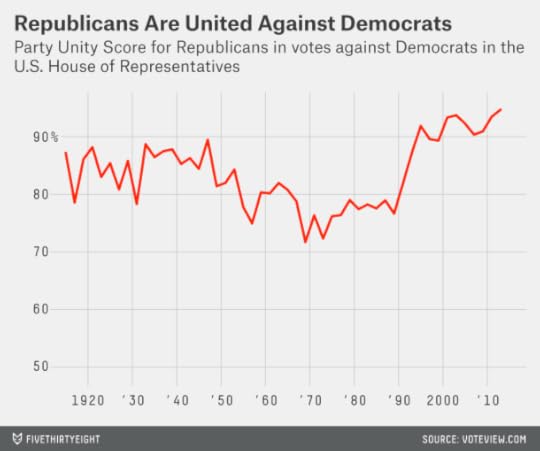

John Boehner’s tenure as speaker of the House, which will end with his resignation next month, is striking because of a seeming contradiction. By statistical measures, it featured an extraordinary degree of party unity among Republicans in the House. At almost no point in history have such a large majority of Republicans voted together so often, especially when they stood in opposition to Democrats.

And yet, Boehner was brought down by division within the Republican ranks: His decision to resign was motivated by a group of dissident, highly conservative Republicans, the Freedom Caucus, who had threatened a no-confidence vote in his speakership. Meanwhile, Republicans have had trouble reaching consensus in many other respects during Boehner’s years as speaker: most notably, in choosing a candidate in the current presidential race.

So are Republicans a party united or divided? To a historic degree they are both. They are united against Democrats and deeply divided as a group.

The rest of this article will rely on data from Voteview.com, a website published by political scientists Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal and Christopher Hare. Voteview tracks roll call voting in Congress and publishes statistics such as DW-Nominate, an algorithm that rates members of Congress on a liberal-conservative scale. One Voteview statistic is called the Party Unity Score, which measures the unanimity of voting within one party when it stands in opposition to the other party.1 In the 113th Congress, which served under Boehner from January 2013 to January 2015,2 Republicans had a Party Unity Score of 94.6 percent, the highest ever for the GOP.3

Revealingly, however, Republicans were more united when voting against Democrats than when voting with them. On issues where Republicans voted in the opposite direction from Democrats, the GOP had a Party Unity Score of 94.6 percent, as I mentioned. But when the parties took the same side on a vote, fewer Republicans — 90.4 percent — joined the GOP majority. Put another way, Boehner had an easier time getting Republicans to agree with one another when they disagreed with Democrats. This might seem obvious, given the hyperpartisan politics of Congress today, but by this statistical measure it’s fairly unusual historically.

It also helps to explain the dynamics of the last couple of congresses. The 112th and 113th Congresses were among the least productive ever as measured by the number of bills passed into law. But that doesn’t mean Boehner left the House to twiddle its thumbs. Instead, he scheduled a lot of votes: The 112th Congress took about 1,600 roll call votes and the 113th took about 1,200, according to Voteview’s data, high figures by historical standards.

Many of those votes were like the dozens that Boehner scheduled to defund Obamacare or Planned Parenthood. The legislation under consideration had no chance to become law so long as Democrats controlled the presidency (and, until this year, the Senate). It’s not that these votes served no purpose, however. Instead, they may have been more like bonding rituals — a way for Boehner and congressional Republicans to reassert their partisan loyalty, both to one another and to the donor base at home.

Republicans may have needed a few of those feel-good moments because, as we’ve seen in the presidential race, there are quite a few ideological divisions within the party. We at FiveThirtyEight usually prefer to think of these divisions as existing along multiple dimensions — for instance, there can be some Republicans who are moderate on social policy but conservative on fiscal policy, or vice versa. But they also show up in DW-Nominate, an algorithm that tries to explain as much congressional voting behavior as it can along a single, left-right axis.4

GOP lawmakers have steadily become more conservative, according to the system. DW-Nominate scores run on a scale from roughly -1 (extremely liberal) to +1 (extremely conservative), where 0 represents a centrist, and the median House Republican in the 92nd Congress, which served from 1971 to 1973 under President Richard Nixon, had a DW-Nominate score of +0.193, only very slightly to the right of center. By the 113th Congress, the median score had increased to +0.732, which is extremely conservative. The most conservative Republicans in the House 25 or 30 years ago would be among the most liberal members now, says DW-Nominate.

But, while there are few truly moderate Republicans left in Congress,5 there are meaningful differences between highly conservative, anti-establishment groups like the Freedom Caucus and pro-establishment, mainline conservative groups like the Main Street Partnership. In fact, according to DW-Nominate, these differences have expanded over time. In the 113th Congress, the gap in DW-Nominate scores between the most conservative flank of the GOP and the most moderate flank6 was the highest ever for the modern Republican Party:

When Republicans stand in opposition to Democrats, these differences don’t matter all that much. According to DW-Nominate, the most liberal Republicans in Congress are now to the right of the most conservative Democrats. But when the Republican Party is working on its own, choosing strategies, legislative priorities and candidates for office, they can reveal considerable dissent within the party. Should Republicans win the White House next year, they’ll probably have unified control of government.7 That might prove trickier for Republicans to manage than you might think, and now they’ll have to do it without Boehner at the helm.

Read more:

The Hard-Line Republicans Who Pushed John Boehner Out

September 24, 2015

It’s Time For Drew Brees And The Saints To Break Up

If there’s still a good NFL team lurking in Louisiana, it’s hiding. Since a gritty win in Philadelphia in the divisional playoffs on Jan. 4, 2014, the New Orleans Saints have gone 7-12, despite playing one of the NFL’s easiest schedules. According to our Elo ratings, they’ve suffered the sharpest decline of any NFL franchise since the start of the 2014 regular season. And after an 0-2 start this year, they have just a 15 percent chance of making the playoffs.

Once upon a time, this would have been no big deal: The Saints have had a mostly miserable history, and they still rank 28th out of the 32 active NFL franchises in lifetime winning percentage. But we’d grown used to something different. Under quarterback Drew Brees, the Saints won a Super Bowl and were consistently in the championship conversation. Despite the occasional hiccup, they maintained a league average Elo rating (1500) or higher for more than six consecutive seasons, from Nov. 24, 2008, through Dec. 7, 2014.

What happens when a franchise declines suddenly after such a sustained period of success? Can it sometimes be a false alarm? Can it replace a few parts and return to contention? Or is it doomed to years in the wilderness?

The short answer: yes, yes and yes. It depends. It depends mostly on the quarterback situation and how the franchise manages it.

I searched our all-time Elo ratings database for cases similar to the Saints’: teams that were very good for at least five consecutive seasons but then declined fairly quickly. (See the official criteria in the footnotes.1) There have been 14 of them since the AFL-NFL merger in 1970, including some of the fabled dynasties of the modern NFL.

In the table below, I’ve also named the team’s incumbent quarterback — or quarterbacks, in the event of a controversy — at the time the 1500-plus Elo streak was broken.2 Finally, I’ve listed how long it took the team to recover to contender status, which I define as having an Elo of 1600 or higher.

TEAMHIGH-ELO STREAKQB AT END OF STREAK (AGE)YEARS TO RECOVER TO CONTENDER STATUSColts1963-72Domres (25), Unitas (39)3.1Chiefs1965-74Dawson (39, injured)7.0Cowboys1966-86White (34, injured)5.0Vikings1968-78Tarkenton (38)9.0Dolphins1980-87Marino (26)3.049ers1981-99Young (38, injured)2.1Raiders1982-87Wilson (30), Hilger (25)3.2Broncos1984-90Elway (30)1.1Bears1984-89Harbaugh (26), Tomczak (27)0.9Rams1999-04Bulger (27)10.8+Eagles2000-05McNabb (29)3.0Colts2002-11Manning (35, injured)3.1Steelers2004-13Roethlisberger (31)1.3Saints2008-14Brees (35)??At first glance, this list doesn’t look all that bad for the Saints. The median team took 3.1 years to recover to contender status; the average team3 took 4.1 years.

But the average looks better than it otherwise would be because of a series of teams that had a stud quarterback in the prime of his career. Dan Marino’s Dolphins, John Elway’s Broncos, Donovan McNabb’s Eagles and Ben Roethlisberger’s Steelers each endured a rough patch. But those QBs were between 26 and 31 when the slump began, leaving their teams with plenty of time to adjust around them.

Brees, by contrast, was 35 when the Saints’ Elo streak was broken last season. Past teams like the 1974 Chiefs, 1978 Vikings and 1986 Cowboys that held on to their aging QBs a year or so too long (sometimes through intermittent injuries) took longer to recover — and it was only once a new quarterback replaced the veteran that they did.

The 2011 Colts, with Peyton Manning, and the 1999 49ers, with Steve Young, appear to be exceptions — both franchises rebounded pretty quickly after miserable seasons. But Young and Manning were injured so severely that their teams were forced to contemplate life without them — or at least had a convenient excuse to move on. Both had already played their last games for their clubs4 at the time their Elo streaks ended, it turned out.

Brees is in the all-time inner circle of franchise quarterbacks: Only five others (Manning, Brett Favre, Marino, Elway and Tom Brady) have accumulated more passing yards with a single club. The problem is that a quarterback who’s been good for as long as Brees can obscure deterioration in the team around him. ESPN’s QBR includes a calculation of how much a quarterback is worth to his team in each game, relative to an average or replacement-level QB. This allows us to estimate how often a replacement QB would swing a game from a win to a loss, or vice versa. For instance, if the Saints win by 7 points and QBR estimates that Brees was worth 8.2 points, that’s a game where the quarterback made the difference.

SAINTS’ RECORD WITH …YEARDREW BREESAVERAGE QB (PROJECTED)REPLACEMENT QB (PROJECTED)200610-610-68-820077-97-96-1020088-88-87-9200913-311-510-6201011-58-86-10201113-310-69-720127-95-113-13201311-511-56-1020147-95-114-1220150-20-20-2Total87-5975-7159-87Basically, we’re looking for cases in which a quarterback plays really well in a close win.5 Brees has had a lot of those clutch wins.6 Since 2006, his first year with the Saints, the team is 87-59 in the regular season.

But with a replacement-level QB, they’d be 59-87 instead, according to this method. And the last few years would have been especially awful: The Saints would have gone 3-13 in 2012, 6-10 in 2013 and 4-12 in 2014 with Mark Sanchez or Brandon Weeden or some other replacement-level QB at the helm.

Or … maybe not, since the Saints would have had a lot more money to invest elsewhere in the roster. Brees’s contract counts for $26.4 million against the salary cap this year, making it the biggest cap hit in the league. Because the top NFL quarterbacks are probably underpaid relative to the disproportionate value they can provide to their clubs, that’s not even all that terrible a contract so long as Brees is among the top half-dozen quarterbacks in the league — as he was until this season. But the minute Brees gets hurt, or reverts to league average (or worse) because of age, the Saints are left with a rotting carcass of a roster and a salary cap crisis.

In fact, for all their irrationality in other areas, NFL teams have usually been able to anticipate these problems and have been remarkably unsentimental in parting ways with aging franchise quarterbacks in the salary-cap era. The first signs were in 1993, when Joe Montana was traded.7 Then came Phil Simms — who, after a somewhat miraculous comeback season in 1993, was unceremoniously released the next spring. Troy Aikman might have retired anyway because of injuries, but he was ushered out the door. The same goes for Young, who was not welcome back in San Francisco. Warren Moon was passed around like a joint at a Phish concert toward the end of his career. Kurt Warner was benched. McNabb endured a fate worse than being benched: He was dealt to Washington. Favre had a reality-TV-style mess of a divorce from the Packers. Manning was let go once the Colts knew they had an opportunity to draft Andrew Luck.

These NFL teams have generally recognized that it’s better to break up with an aging quarterback a year too early than a year too late. And almost none of those decisions look bad in retrospect.8 Brees may still have something left — quite possibly enough to lead another franchise somewhere to a deep playoff run — but it’s probably time for he and the Saints to move on from each other.

Check out our NFL predictions for odds on every Week 3 game.

Who Does Scott Walker’s Exit Help?

We called the FiveThirtyEight politics team together in Slack — including a new member! — to reassess the GOP field now that Scott Walker has quit the race. Below is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

micah (Micah Cohen, senior editor): It’s been a few days now since Scott Walker dropped out, and the conversation is moving from “What went wrong with Walker?” to “Who does this help?” And that’s our question for today. … But before we get to that, let’s welcome Farai Chideya, who just joined FiveThirtyEight as a senior writer and is going to be covering — among other things — the 2016 campaign.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Welcome, Farai!

hjenten-heynawl (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Shalom, Farai. Welcome to the no-spin zone. Oh wait.

faraic (Farai Chideya, senior writer): I’ve covered every election since 1996 in some way, shape or form and am excited to do it the FiveThirtyEight way.

micah: As the newest member of these chats, Farai, you get first crack at the question: Who do you think Walker dropping out benefits?

faraic: Well, let’s start with the patronizing. In June, Walker kept harping on how he wanted Marco Rubio for veep. Rubio said in turn: “Walker-Rubio ticket may be fine, but it’s got to be in alphabetical order.”

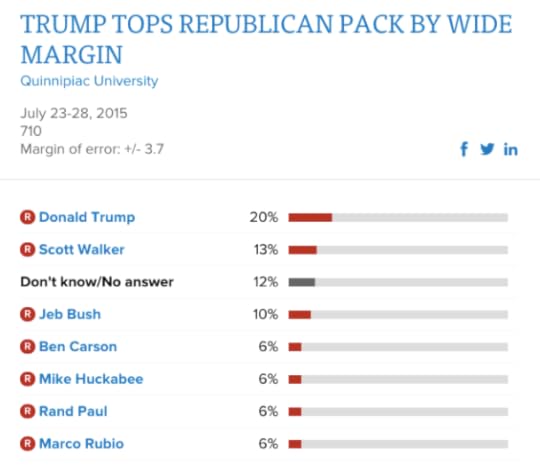

Walker was extremely cocky, but he had the polls going for him at that time. From Politico:

But now I think Rubio is the biggest winner.

natesilver: Yeah, Rubio seems to be the default answer. They’re fairly similar ideologically. They each have some credibility with both the establishment and the grassroots — or at least, they were supposed to. And we’ve already seen reporting on how a number of ex-Walker staffers are defecting to Rubio.

micah: You concur, Harry?

hjenten-heynawl: I mean, Rubio is the easy answer. He has already grabbed a bunch of Walker’s fundraisers, and they are both folks elected in the 2010 tea party wave with one foot in the establishment and one in the grassroots.

But again, this is tricky stuff. Jeb Bush has also grabbed some of Walker’s backers, and we know that voters placed Walker closer to Ted Cruz than Rubio ideologically.

micah: So unpack this a little more. … Does Walker being gone help Rubio because they were competing for the same voters?

faraic: I think there is some voter overlap; more funders freed up; but also it’s the astronauts-in-a-capsule situation. There’s only so much oxygen in the capsule. A certain number of the astronauts — or candidates — are bound to asphyxiate.

I know it’s a grim metaphor, but Rubio just got a lot bigger share of oxygen.

natesilver: OK, since the purpose of the chats is (among other things) to check our priors, let me bring up a contrarian point of view. A devil’s advocate case. Let’s say you run a small business, and you wake up in the morning and find that your closest competitor has gone out of business. Is that good news or bad news?

faraic: I know this is a trick question, Nate! I plead the fifth!

micah: So could Rubio have the same problem Walker did?

natesilver: I’m just saying that’s a line of argument: If Walker failed to bridge the divide between the establishment and the base — despite not having done anything all that obviously and egregiously wrong as a candidate — maybe Rubio could have trouble too? Maybe the business model failed, in other words, instead of the business.

hjenten-heynawl: We’re jumping around the issue here. Walker had two main problems: 1. He didn’t raise enough hard money — Rubio doesn’t appear to have that problem so far. And 2. Walker didn’t have good debates to keep his polling up, to get more money — Rubio’s debate performances have gotten good grades.

faraic: A new Florida poll shows Rubio is now ahead of Bush in their home state.

natesilver: Look, I’m still on the Rubio bandwagon. Like I said in last week’s chat, I sometimes feel with Rubio like he’s the contestant on a reality show where it’s totally obvious that he’s eventually going to win, but the network needs to create dramatic subplots for 17 weeks before it happens.

faraic: Ha! Rubio has great hair. If the election was a hair-stakes, I’d vote for him for sure.

hjenten-heynawl: Let me say, I sent an email to a Democratic pollster last night with the subject line “It will be Rubio. I think. Unless of course, it isn’t. ”

micah: All right, so why not Cruz?

hjenten-heynawl: Because he’s too conservative and says things off the cuff that shouldn’t be said.

natesilver: He’s not very popular with his colleagues.

hjenten-heynawl: He pisses off the establishment with this government shutdown stuff.

faraic: As someone who has spent time being awkward on camera, I can also say his robotics on camera in the debate made him look like an advanced android. But that is not why he will not get the nomination. But just sayin’.

micah: But Walker dropping out helps Cruz, right? He may not win, but this gets him a little closer?

hjenten-heynawl: Sure. But his chances jump from 4 percent to 6 percent, or something like that. Walker quitting doesn’t get Cruz that much closer to the nomination.

faraic: Cruz is just too loathed by too many GOP insiders.

natesilver: I mean, there’s an absence of candidates who are both 1. establishment-approved and 2. reliably conservative, at least by the current GOP standard where you need to be very conservative indeed.

micah: Interesting …

hjenten-heynawl: Walker was that person, supposedly.

micah: Who meets those standards now?

natesilver: After Rubio, you have … I dunno. Bobby Jindal?

micah: So Cruz fails on No. 1.

faraic: Carly Fiorina is way ahead of Jindal. And ahead of Cruz.

hjenten-heynawl: Jindal has tremendous problems back at home. Most observers would regard that governorship as one that didn’t bring people together.

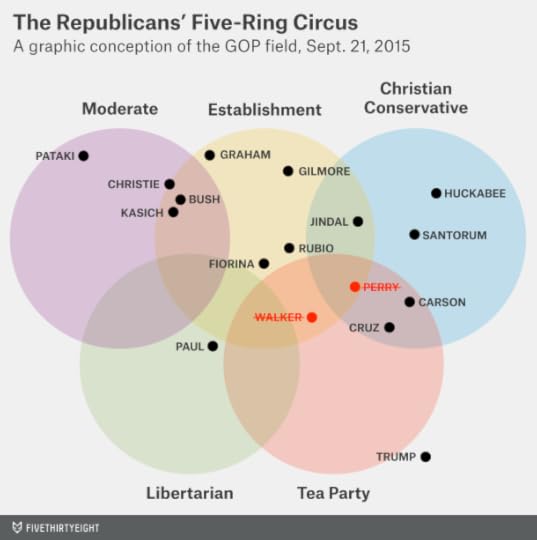

natesilver:

Sleeper pick to benefit from Walker dropout: Jindal

— Nate Cohn (@Nate_Cohn) September 22, 2015

hjenten-heynawl: But let me throw this in on Jindal: His net favorability in Iowa is quite high — at or slightly ahead of Cruz, depending on the poll.

natesilver: From the Des Moines Register:

Jindal’s held more events in Iowa than anyone but Rick Santorum, and his numbers were pretty similar to Walker’s in Iowa. Granted, Walker’s numbers in Iowa were no longer so good. But … there’s this huge question now of whether an establishment candidate can win Iowa.

micah: Jindal seems like the type of candidate who could win Iowa: socially conservative, Southern, etc. — Huckabee-esque.

natesilver: I’m sure Rubio’s campaign was doing high-fives when they found out that Walker dropped out, for example. But they were sort of tiptoeing around the question of whether they would “compete” (i.e., raise the media’s expectations) in Iowa. Now they might need to take that more head on.

faraic: I still think Rubio is playing a long game for 2020 or 2024. But if things accelerate, well, who is he to say no?

micah: Yeah, Rubio is young and potential VP material.

natesilver: It’s a little unpredictable because historically the best way to forecast how much of a bounce you’ll get out of Iowa is how well you do relative to your polls.

But my guess is that Rubio would get mostly good press if he were the top establishment-y candidate in Iowa and finished somewhere in the top three.

micah: So what about Fiorina then? As Farai said, couldn’t Walker leaving help Fiorina? Nate, you’ve said before that she’s weirdly both establishment and outsider.

hjenten-heynawl: She has two congressional endorsements now, but I still think her record at Hewlett-Packard is awful by most people’s standards — and that if anything, her performance in the 2008 campaign as a McCain spokesperson and in 2010 in her own Senate campaign shows that the more people get to know her, the worse she tends to do. But in the short-term: Sure, why not.

faraic: Fiorina is marvelously composed, but/and she does not exude populism. And when she comes into contact with the Trump-populism-from-a-billionaire fans, I’m curious how and if she will adjust her message.

natesilver: In some ways, Fiorina is the opposite of Cruz. She’s nominally an outsider, but in establishment packaging. He’s nominally part of the establishment, but in outsider packaging.

micah: Which could prevent her from moving in on the grassroots/outsider space vacated by Walker?

faraic: Walker himself was an interesting insider/outsider — someone who ran for and got into office in order to downsize the state. I think Fiorina could make a plausible argument she’d be willing to do that. But again, how would that help the fearful voters who worry about jobs?

She’s not willing to go as nativist as Trump is.

natesilver: Fiorina may have particular experiences that help her in debates. Being a CEO in the tech world, which is so male-heavy, she’s in the top 0.0001 percent in terms of knowing how to get her message across in a room full of men with giant egos. But the debates are just one element of the campaign.

hjenten-heynawl: As we learned with Joe Biden and Mike Huckabee in 2008.

natesilver: The two endorsements Fiorina has gotten in the past three weeks are more than anyone else in the GOP field over that period. No one else has more than one!

natesilver: There’s also the question Harry raised about her background at HP. I guess I’d say it’s hard to know if that will blow up into a campaign-defining issue or not. It depends a lot on whether the media thinks it’s a sexy story. Or inside baseball. Or old news.

hjenten-heynawl: It blew up on her in the California Senate race in 2010 (not saying it will now).

natesilver: But more to the point: It depends on how the establishment feels about Fiorina. If there’s a world in which a successful-CEO-type like, oh, Mitt Romney sends out signals suggesting he likes Fiorina, that could matter a lot. If he says she was a failure, that could matter too.

micah: Mitt Romney, kingmaker! (or queenmaker, in this case).

natesilver: OK, Harry, since I guess I’m more on the Fiorina bandwagon than you: Was 2010 really such a failure for Fiorina?

hjenten-heynawl: Depends on what your definition of a “failure” is:

She lost. That’s a fail.She outperformed Romney in California. That’s a win.She lost steam as the campaign went on. That’s a fail.natesilver: She won a fairly tough primary. And losing to a three-term Democratic incumbent by “only” 10 percentage points in California is not so bad.

hjenten-heynawl: A fairly unpopular incumbent in a fairly good Republican year.

micah: Farai, if you were Fiorina … Walker drops out … there’s a little more room now, do you try to consolidate your appeal to the establishment, to the grassroots, or do you try and thread the needle and appeal to both?

faraic: Fiorina could do well — not saying she will do this — by triangulating Hillary Clinton (only in terms of a strong woman/first female president card), Mitt Romney (in his compassionate conservative guise), and the ghost of Scott Walker (smaller government).

I think in this case: Go for more campaign cash, slick ads and the establishment.

natesilver: Yeah, I agree. I think there’s a window of opportunity here. Or maybe not. But if Fiorina has a chance, she’s going to need some establishment support and a fair bit more cash. Now’s as good a time as any for her to find out about those things.

hjenten-heynawl: Triangulating can work brilliantly or fail miserably. It failed for Walker.

faraic: Populism is probably not a good look for her and arguably doesn’t fit that easily on Clinton either.

micah: OK, so if you’ll allow me to summarize and oversimplify: It seems like we think Walker dropping out helps Rubio > Cruz > Jindal > Fiorina > Everyone else.

natesilver: I’d put Rubio in the first tier and then Cruz, Jindal and Fiorina in the second tier.

micah: Let’s do lightning round — helps/hurts/push — on a couple of more people:

Jeb!

hjenten-heynawl: Helps (probably).

faraic: Agreed, but only marginally.

natesilver: Let me point something out. When a strong contender gets knocked out of the field — like a No. 1 seed in the NCAA tourney — it almost always helps everyone else. It helps some more than others, like if they’re on your side of the bracket. But it’s only in pretty weird circumstances where it actually hurts you.

micah: Right — I guess in this case we mean above and beyond the fact that there’s one less contender.

natesilver: But, anyway, sure, there’s a chance it helps Bush.

micah: Jim Gilmore … just kidding … Ben Carson: helps/hurts/push?

natesilver: It was interesting how Walker mentioned in his statement about how it was important for the establishment to rally around a candidate and for others to drop out.

micah: Nate, you’re not grasping the core concept of the lightning round.

natesilver: OK, only one-word answers from me on out: Carson. Helps? Iowa.

hjenten-heynawl: Agreed.

faraic: Yup (I feel like Walker was such an asterisk at the end that everyone gets 1/15 of a tiny, tiny pie).

micah: Mike Huckabee?

faraic: No.

micah: Huckabee is beyond help?

faraic: Kinda. Carson stole his demo.

hjenten-heynawl: It seemed to me like Walker didn’t appeal too much to evangelicals in Iowa, so he wasn’t competing with Huckabee for voters. And with Walker out, it may raise the percentage needed to win in Iowa because the vote will be split among fewer candidates. So Walker quitting may, in fact, hurt Huckabee.

natesilver: Helps? Iowa.

micah: John Kasich.

faraic: Helps.

natesilver: Helps? Midwest.

hjenten-heynawl: I’ll go with the crowd here.

micah: Chris Christie.

hjenten-heynawl: Push.

faraic: Ditto.

natesilver: Helps? Boredom.

micah: Rand Paul.

faraic: Helps.

hjenten-heynawl: Hurts. Raises percent needed to win in Iowa.

natesilver: Is 0>0?

micah: Donald Trump.

faraic: Push.

natesilver: OK, I’m going to violate my one-word rule. I think it probably doesn’t matter much to Trump, but Walker dropping out is one sign that the “party is deciding,” as I was about to say when Micah so rudely interrupted me earlier. It’s also possible that Trump will decline for reasons that don’t have much to do with Walker.

hjenten-heynawl: Donald Trump is who he is, no matter who is in the race. #Trump2016

micah: All right — closing question: How would you sum up the Walker campaign in three words or less?

faraic: “Wasn’t my money.”

September 22, 2015

Podcast: Nate Silver On The Power Of Elo

Welcome to this week’s episode of Hot Takedown, our podcast where the hot sports takes of the week meet the numbers that prove them right or tear them down. On this week’s show (Sept. 22, 2015), Nate Silver joins for a special one-on-one discussion with Chadwick Matlin (Neil Paine and Kate Fagan are out of town). Nate and Chad talk about a Boston University report that raised an alarm about long-term brain injury in NFL players and what it says about sample size. Then, Nate offers a defense of Elo, the power rating we use at FiveThirtyEight to rank teams and athletes in nearly every sport. What is Elo? How does it work? Are the 2007 New England Patriots really the best NFL team of all time despite not winning the Super Bowl?

And to close out the show, a Significant Digit on a new accomplishment by U.S. soccer midfielder Carli Lloyd.

Stream the episode by clicking the play button, or subscribe using one of the podcast clients we’ve linked to above. Below is a video excerpt and links to some of what we discussed on the show:

Concussion watch: ESPN’s list of injuries in the NFL.The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Boston University announced that 87 out of 91 former NFL players who donated their brains for testing after their deaths tested positive for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).The 2007 Patriots have the highest Elo rating of any team in the history of the NFL.Significant Digit: 5 x 5. Carli Lloyd’s hat trick in Sunday’s U.S. women’s national team win over Haiti makes her the fifth American with five international hat tricks.How can the 2007 Patriots be the best NFL team ever when they didn’t even win the Super Bowl?If you’re a fan of our podcasts, be sure to subscribe on iTunes and leave a rating/review. That helps spread the word to other listeners. And get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments. Tell us what you think, send us hot takes to discuss and tell us why we’re wrong.

September 21, 2015

Scott Walker May Have Been A Terrible Candidate — Or An Unlucky One

If you’ve been following FiveThirtyEight’s election coverage, you’ll know we’ve been bullish about two Republican candidates throughout the campaign. One is Marco Rubio, who’s done reasonably well so far and is rising in the polls after two solid debate performances. The other is Scott Walker, who just called it quits.1

We liked Rubio and Walker for pretty much the same reason: They seemed to have the best claims in the field for balancing conservatism with electability, historically a sweet spot for Republican nominees. Rubio’s policy positions are close to the mean of Republican elected officials — which is to say, they’re quite conservative without being “extreme.” But Rubio’s also a disciplined politician and potentially has the charisma to connect with a broader group of voters (hailing from a swing state like Florida and being Latino doesn’t hurt his electability case, either).

Walker is slightly more conservative than Rubio — perhaps slightly “too” conservative for a general election candidate.2 But he had a genuinely impressive electability record in his favor, having been elected three times in four years (including a recall election) in a blue-leaning swing state, Wisconsin.

Put another way, it looked like Walker could potentially be the best of both worlds for Republicans — bridging the gap between the establishment and the insurgent wings of the party by being a credible nominee with both groups.

But any time a new product is billed as the best of all possible worlds, it could wind up being the worst of all possible worlds instead. A certain type of tablet computer might be advertised as a perfect substitute for both a laptop and a smartphone, for example. But it could turn out to be worse than a laptop at laptop things and worse than a smartphone at smartphone things, leaving pretty much no one satisfied.

Likewise, Walker seemed to be nobody’s first choice — to the point that he polled at an asterisk (less than 1 percent of the vote) in CNN’s most recent poll after the second Republican debate. Voters craving a political outsider had shinier objects to chase down — most notably, Donald Trump. But Walker wasn’t doing all that well with the establishment either, having received just one endorsement from Republican governors or members of Congress since April, having (reportedly) had trouble balancing his campaign’s budget, and having developed a reputation for being gaffe-prone on the campaign trail.

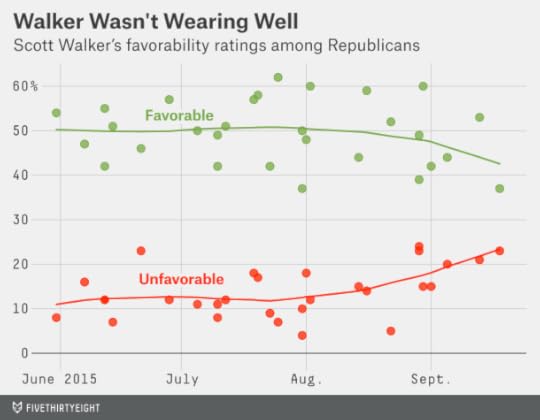

Nate Silver and Harry Enten on Scott Walker’s early exitAnd yet, Walker still had a couple of things going for him. He had been polling well in Iowa for much of the campaign and was still a plausible winner there. And his favorability ratings — sometimes a better indicator of who could be a broadly acceptable nominee — were reasonably good among Republican voters, at an average of about 45 percent favorable and 20 percent unfavorable in the most recent polls.

One problem for Walker is that those favorability ratings had been falling, slightly. But more strikingly, he was having trouble making much of an impression at all with voters. In June, his combined favorable and unfavorable rating among Republicans was 60 percent. As of now, it’s only about 65 percent. Walker’s name recognition — or at least, the number of voters who know him enough to have an opinion about him — hasn’t increased very much at all.

Many people will compare Walker to Tim Pawlenty, who similarly had trouble differentiating himself from the field (in 2011, I described Pawlenty as the RC Cola of candidates). The comparison mostly works, though with a few qualifications. On the one hand, Walker began the race with a higher national profile than Pawlenty — and a signature political accomplishment in having fought public-sector unions in Wisconsin and then winning a recall election contested on that issue. On the other hand, there’s even more of a premium on differentiation in a 17-candidate field than in the one Pawlenty faced four years ago.

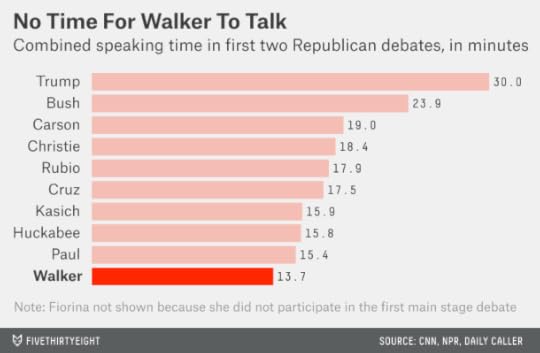

But for all the inevitable second-guessing about Walker’s campaign — and to their credit, some observers including Alec MacGillis have been questioning Walker’s political acumen to begin with — it’s also possible that he got unlucky in some senses. Walker was mediocre in the debates, but he had fewer than 14 minutes in both debates combined to speak to voters: the least for any candidate on the main stage for both events.

And while Walker had some missteps on the campaign trail — such as implying that the U.S. should consider building a border wall with Canada — they don’t seem to be much worse than the gaffes other candidates have committed.

But Walker was caught in something of the same vicious cycle as Hillary Clinton. There were some genuine but not obviously mission-critical problems with his campaign; there were some poor polling numbers; and there was increasingly negative media coverage. All of these tended to feed back upon and accentuate one another, making his situation worse. Unlike Clinton, however, who (probably) has the resources to pull herself out of the spiral — and who benefits from the lack of competition on the Democratic side — Walker won’t get a second chance to make a first impression.

Check out all of our 2016 election coverage.

September 16, 2015

Hillary Clinton Is Stuck In A Poll-Deflating Feedback Loop

It’s the candidates who play the long game, and play by the establishment’s rules, who usually win presidential nominations. Political parties have lots of ways to influence the race in favor of these candidates, from how they appoint superdelegates to how they schedule debates. Hundreds of millions of dollars are spent on advertising, meanwhile, and the bulk usually favors establishment candidates. And voters have a lot of time to make their decisions and can amend them as they go along — an insurgent candidate who wins Iowa or New Hampshire won’t necessarily have staying power if they’ve failed to build a broad coalition of support.

The short run is different. The short run can be crazy. Feedback loops can produce self-reinforcing (but usually temporary) booms and busts of support. For instance, a candidate who has some initial spark of success, such as by doing well in a debate, can receive more favorable media coverage. That, in turn, can beget more success as voters jump on the bandwagon and his poll numbers go up further.

Candidates can just as easily get caught — or entrap themselves — in self-reinforcing cycles of negative media attention and declining poll numbers. Hillary Clinton looks like she’s stuck in one of these ruts right now.

The Washington Post’s David Weigel recently observed that voters were hearing about only three types of Clinton stories, all of which have negative implications for her. First are stories about the scandal surrounding the private email server she used as secretary of state. Next are stories about her declining poll numbers. And third are stories about how Vice President Joe Biden might enter the Democratic presidential race.1

Weigel isn’t exaggerating: For roughly the past two months, voters have heard almost nothing about Clinton apart from these three types of stories. I went through the archives of the news aggregation website Memeorandum, which uses an algorithm to identify the top U.S. news stories of the day. I tracked whether there was a Clinton-related headline in one of the top three positions at 11 a.m. each morning and, if so, what the subject was.2 You can see the results below:

Since Friday, July 24 — I’ll talk about the significance of that date in a moment — there have been 13 mornings when Clinton’s email server was a major story, seven mornings when her bad polling numbers were a major story,3 and seven mornings when speculation about Biden running was a major story. There have also been two other mornings when there were some miscellaneous negative headlines for Clinton, like this one about Bill Clinton’s paid speeches. That’s a total of 29 days of negative coverage in just over seven weeks. Clinton’s campaign has had a lot of bad mornings.

By contrast, I identified just one morning since July 24 when a favorable headline for Clinton gained traction on Memeorandum (the endorsement of Clinton by former Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin), along with four other mornings when there was an ambiguous Clinton-related story making news, like this one about her comments on Jeb Bush.

This differs from earlier in the summer. From June 14 — the Sunday after Clinton’s first big campaign speech (on Roosevelt Island in New York) — through mid-July, Clinton wasn’t making all that many headlines. And when she did, there was a fairly even mix of negative and positive stories.

What changed? July 24 was the morning after The New York Times reported that “a criminal investigation” had been launched into whether Clinton had “mishandled sensitive government information” on her email account. That report turned out to be mostly erroneous; the Times later appended an editor’s note to the article, which is about as close as a newspaper will get to retracting a story. Still, the email story was back in the news after several months when there hadn’t been much reported about it. And subsequent stories about the investigation into Clinton’s email server, from the Times and other news outlets, have proved to be better-reported than the Times’s initial misfire.

Meanwhile, that was also about the time that speculation about a late Biden entry ramped up, particularly beginning with an Aug. 1 story by Maureen Dowd of The New York Times.4 A lot of the Biden stories have a Groundhog Day feel to them; they contain relatively little hard evidence about his intentions, and Biden continues to postpone his decision about whether to run. But Biden and his confidants may be deliberately keeping his name in the news to test Democrats’ appetite for a Biden bid. Whenever there’s a lull in the news cycle, Biden’s name seems to pop up again.

Then, of course, there are the stories about Clinton’s poll numbers. The media can, and sometimes will, cherry-pick polls to reinforce its preferred narrative about the campaign, even when the data doesn’t support it. Lately, however, they haven’t needed to cheat: There have been some genuinely poor results for Clinton in the polls. She’s fallen behind Sanders in most polls in New Hampshire and some polls in Iowa, and she increasingly also trails Republicans in hypothetical head-to-head matchups.

No one of these stories is necessarily all that damaging to Clinton on its own. But together, they potentially enhance and reinforce one another. Biden is being included in most polls of the Democratic race, and his numbers have improved as the media has given more coverage to his potential campaign, with most of that support coming from Clinton. Furthermore, the various Clinton scandals — past, present and future — are one of the principal rationales for Biden to run, whether or not he says so explicitly. It’s hard to prove whether the email scandal itself is directly responsible for driving down Clinton’s numbers, and it’s possible that the patina of negative associations generated by the story matter more than the details.5 But it certainly isn’t helping her.

So then: Clinton is toast? Probably not. In the assessment of betting markets, she’s still a reasonably heavy favorite for the Democratic nomination. That’s my assessment too. There are a number of ways the spiral of negative stories could end:

New news stories could disrupt the cycle.6Biden could opt out of the race and possibly also endorse Clinton.The trickle of new revelations on the email story could stop — as it largely did from April through June.Clinton could lift her poll numbers, perhaps temporarily, with an aggressive advertising spend.Clinton could hit some bedrock of support — her most loyal voters — beyond which her poll numbers wouldn’t decline much further.7Clinton could fall far enough that the “Clinton comeback” story becomes more compelling to the media than the “Clinton in disarray” story, as happened late in the 2008 Democratic primary campaign.Usually, the biggest risk to candidates in a rut like Clinton’s is that the streak of negative news, even if it’s temporary, can lead to irrevocable effects. It might be silly to count out Scott Walker on the Republican side, for instance: Other candidates, such as John Kerry in 2004 and John McCain in 2008, have come back from roughly similar positions to win their party’s nomination. But if Walker’s fundraising dries up, or if his staff defects to other candidates, or his potential supporters rally around another candidate, that could be harder to overcome.

Clinton has fewer such risks given how she’s pre-empted so much of her potential competition from running in the first place and how late it would be for anyone else to enter. In fact, she’s already received the endorsements of the majority of Democrats in Congress.

But Biden has to make his decision soon. My previous thinking had been that he would beat Clinton only if there were another shoe to drop — i.e., another wrinkle in the email story or a new scandal of some kind. But perhaps if the timing were right, he could take advantage of a full-blown panic among Democratic elites even without such a catalyst?

Perhaps. But it would also take a lot of work and entail a lot of embarrassment to unwind the establishment’s support from Clinton. These party elites would have a lot of explaining to do to Democratic voters about what had changed and why they were revoking their support for the first potential woman president in favor of a septuagenarian white guy — and not the septuagenarian white guy from Vermont whom the Democratic grassroots is excited about.

Check out our live coverage of the second Republican debate.

September 10, 2015

September 9, 2015

Stop Comparing Donald Trump And Bernie Sanders

A lot of people are linking the candidacies of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump under headings like “populist” and “anti-establishment.” Most of these comparisons are too cute for their own good — not only because it’s too early to come to many conclusions about the campaign, but also because Trump and Sanders are fundamentally different breeds of candidates who are situated very differently in their respective nomination races.

You can call both “outsiders.” But if you’re a Democrat, Sanders is your eccentric uncle: He has his own quirks, but he’s part of the family. If you’re a Republican, Trump is as familial as the vacuum salesman knocking on your door.

Consider the following. We’ll start with some of the more superficial differences between Sanders and Trump and work our way to the more important ones.

1. Trump is “winning” (for now), and Sanders isn’t. There are lots of reasons to suspect that Trump will fall from his position atop the GOP polls sooner or later, but he’d be a favorite to win a hypothetical national primary held today. Sanders, by contrast, trails Hillary Clinton by about 20 percentage points in national polls that include Joe Biden, and by 30 points in polls that don’t.

2. Sanders is campaigning on substantive policy positions, and Trump is largely campaigning on the force of his personality. I’m not sure this assertion requires a lot of proof, but if you need some, check out the candidates’ websites. Sanders’s lists dozens of specific policy proposals across a wide range of issues; Trump’s details his position on just one, immigration.

3. Sanders is a career politician; Trump isn’t. Let’s not neglect this obvious one. Bernie Sanders has been in Congress since 1991, making him one of the most senior members of Congress; Trump has never officially run a political campaign before.

4. Trump is getting considerably more media attention. Trump is a perpetual attention machine who gets a disproportionate amount of media coverage — as much as the rest of the GOP field combined. Sanders hasn’t been ignored by the press, which wants a horse race between Sanders (or Biden, or anyone!!!) and Clinton. Still, Sanders’s media coverage has been paltry compared with Trump’s. According to Yahoo News, Trump has received about 35,000 media “hits” in the past month, compared with about 9,000 for Sanders. For comparison, Clinton has had 18,000 hits over the same period, and Jeb Bush has had 14,000.

5. Sanders has a much better “ground game.” Trump, in addition to his ubiquity on television, has some semblance of a campaign operation. But Sanders’s organization is much larger and more experienced.

6. Sanders holds policy positions of a typical liberal Democrat; Trump’s are all over the place. While Sanders doesn’t officially call himself a Democrat — a fact that might annoy Democratic elites — he takes policy positions that are consistent with those of Democrats in Congress. In the previous Congress (113th), Sanders voted the same as liberal Democratic senators Barbara Boxer, Cory Booker, Kirsten Gillibrand and Sherrod Brown 95 percent of the time or more.1 He voted with party leader Harry Reid 91 percent of the time and the expressed position of President Obama2 93 percent of the time. He also voted with Clinton 93 percent of the time when the two were in the Senate together.

Here are the senators Sanders voted with most and least often in the 113th Congress, according to Voteview.org:

SENATORMOST OFTENSENATORLEAST OFTENBoxer (CA)96.2%Manchin (WV)82.1%Markey (MA)95.9Baucus (MT)87.4Booker (NJ)95.8Pryor (AR)87.6Cantwell (WA)95.8Donnelly (IN)89.9Leahy (VT)95.7Hagan (NC)90.0Gillibrand (NY)95.7Heitkamp (ND)90.2Brown (OH)95.7Lautenberg (NJ)90.6Hirono (HI)95.4Tester (MT)90.6Menendez (NJ)95.4Landrieu (LA)90.6Stabenow (MI)95.4Reid (NV)91.4Trump’s positions are harder to pin down — and he doesn’t have a voting record to evaluate — but he has far more profound potential differences with the Republican orthodoxy on major issues ranging from taxation to health care to reproductive rights.

7. Sanders’s support divides fairly clearly along ideological and demographic lines; Trump’s doesn’t. So far, Sanders has won a lot of support from white liberals — which helps him in Iowa and New Hampshire — but not so much from white moderates or non-white Democrats. Each of these groups represents about a third of the Democratic primary electorate nationally, so this makes Sanders’s path to the Democratic nomination fairly easily to analyze; he’ll be viable only to the extent that he gains support among the other two groups.

Trump’s support, by contrast, is fairly evenly spread across a range of demographic and ideological groups that appear in Republican polls. He doesn’t do especially well (or especially poorly) with “tea party” voters, for instance. There are a variety of ways to interpret this — perhaps, even, the “Trumpen proletariat” is a group all its own.

8. Sanders’s candidacy has clear historical precedents; they’re less obvious for Trump. Even the most formidable-seeming front-runners haven’t won their nominations without some semblance of a fight. Clinton’s position relative to Sanders is analogous to the one Al Gore held against Bill Bradley in the 2000 Democratic primary. Sanders’s campaign also has parallels to liberal stalwarts from Howard Dean to Eugene McCarthy; these candidates can have an impact on the race, but they usually don’t win the nomination.

Trump has some commonalities also: to “bandwagon” candidates like Newt Gingrich and Herman Cain; to media-savvy, factional candidates like Pat Buchanan; and to self-funded candidates like Steve Forbes. None of those candidates, however, was as openly hostile to their party as Trump is with Republicans.

9. Trump is running against a field of 16 candidates; Sanders is running against one overwhelming front-runner. Trump is also in new territory in another respect. There’s never been a Republican nomination race — or for that matter a Democratic one — with so many declared candidates. Most of the Republicans are not tokenish candidates either. All but Trump, Ben Carson and Carly Fiorina have served as senators or governors before, many of them in highly populous states.

This unprecedented volume of candidates helps Trump in various ways. For instance, it increases the value of differentiating yourself from the field. Unorthodox or even unpopular policy positions may help you win a faction of the Republican electorate, even if it makes you less popular within your party overall. That faction may be enough to carry the plurality in polls, leading to favorable media coverage and then creating a virtuous cycle that attracts some bandwagon voters.

Meanwhile, the abundance of candidates seems to have resulted in the Republican establishment holding off on throwing its support to any one candidate, either through endorsements or in the money race.

The Democratic establishment, by contrast, has never been so united behind any non-incumbent candidate as they are with Clinton.

10. Trump is a much greater threat to his party establishment. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that Sanders is as threatening to the Democratic establishment as Trump is to the Republican one. Sanders’s policy positions, as I’ve mentioned, are about 95 percent the same as those of a typical liberal Democrat in Congress. And where they diverge, they push Democrats further to the left in a fairly predictable way,3 acting as a “supersized” or slightly exaggerated version of the Democratic agenda. Indeed, while Sanders lacks support from elected Democratic officials, he has some backing from other influential constituencies within the party, such as some labor unions and liberal media outlets.

Why, then, have so few Democrats officially endorsed Sanders? First, because Clinton is extremely popular with both elite and rank-and-file Democrats. Her relative lack of competition is a sign of strength, not weakness — she won the “invisible primary” stage of the campaign. Second, because Democrats are right to be concerned about the general election prospects for Sanders, a 74-year-old self-described socialist. Third, because Sanders’s agenda is hostile to moneyed interests within the Democratic Party.

But if Sanders eventually overtook Clinton, the establishment might resign itself to the prospect of nominating him. There are some loose precedents for candidates like Sanders winning their nominations, especially George McGovern in 1972 and Barry Goldwater in 1964. If you’re going to sacrifice a presidential election — and Sanders would be unlikely to prevail next November4 — you’d at least like to shift the window of discourse in your party’s preferred direction.

A Trump nomination would be more of an existential threat to the Republican establishment. He bucks the establishment’s consensus on issues as fundamental to the GOP as taxation and health care, and he’s wobbly on abortion. Splitting with the party on any one of those issues might ordinarily disqualify a candidate. Trump potentially destabilizes the Republicans’ “three-legged stool”: The coalition of fiscal, social and national security conservatives have dominated the party since 1980 or so. But on the issue on which Trump is most conservative — immigration — establishment Republicans worry that he might be so reactionary as to cause long-term damage to the party brand.

Meanwhile, Trump has picked fights with sacred cows like the Club for Growth and Fox News. Most of the conservative media — from the National Review to RedState to Glenn Beck — is anti-Trump.

In certain respects, Trump is engaged in an attempted “hostile takeover” of the Republican Party. Because the downside of nominating him might be so enormous — lasting beyond a single election — the GOP establishment may fight to the death to prevent him from being chosen, even at the price of a brokered convention and a fractured party base.

What Sanders and Trump have in common is they’re both unlikely to be nominated. (If I were laying odds, I’d put either one at something like 15-1 or 20-1 against.) But it’s for different reasons. Sanders is losing now, but if he eventually overtakes Clinton — and if Biden fails to come to the establishment’s rescue — his position might become more viable. Trump is nominally winning, but the GOP race is much more volatile. And if he doesn’t lose steam on his own accord, the Republican establishment will use every tool at its disposal to stop him.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers