Nate Silver's Blog, page 146

November 16, 2015

If Donald Trump Is The Problem, Mitt Romney Isn’t The Solution

It was only a few weeks ago that Vice President Biden ended months of misguided speculation by affirming that he wouldn’t run for president. But now there’s rumor of another possible last-minute bid, this time on the Republican side.

“[S]ome in the party establishment are so desperate to change the dynamic that they are talking anew about drafting [Mitt] Romney,” reported the Washington Post’s Philip Rucker and Robert Costa on Friday. “Friends have mapped out a strategy for a late entry to pick up delegates and vie for the nomination in a convention fight, according to the Republicans who were briefed on the talks, though Romney has shown no indication of reviving his interest.”

Mitt Romney’s making a comeback? Errrr, probably not. Historically, rumored eleventh-hour bids like these have almost never come to fruition. It’s not just Biden: Until quite late in the 2012 campaign cycle, there were reports that various candidates — Chris Christie, Paul Ryan, Jeb Bush, etc. — might enter the race to challenge Romney. None of them did.

But forget that for a second. (Also forget that when candidates like Fred Thompson and Wesley Clark have launched their bids late, they’ve tended to crash and burn — and that Romney’s bid would be even later than theirs.) Instead, let’s play along.

Unlike Biden, whose quasi-candidacy never had a coherent rationale except as a hedge against a major Hillary Clinton scandal, Romney would be entering a race without a dominant frontrunner. Donald Trump and Ben Carson remain atop the polls. Marco Rubio appears to be in the best position of any establishment candidate, but that’s like having the closest seat to the buffet table at an offensive lineman’s wedding; there’s still a lot of jostling to go before anyone gets their grub.

The only thing the GOP establishment seems to agree upon is that it doesn’t want Trump or Carson to be the nominee. So if the GOP wants to minimize the chance of one of them being nominated, does it make sense to support a Romney campaign?

The answer depends on your theory of why Trump and Carson are leading in the polls. If the GOP has chosen the wrong theory, then throwing its support behind Romney could backfire.

(I’m assuming, by the way, that candidates like Rubio and Jeb Bush wouldn’t instantly drop their bids just because Romney entered the race. Romney would begin with a foothold of establishment support, but would have to fight to win the rest of it.)

Theory No. 1: “It’s just a phase”This theory holds that the polls showing Trump and Carson ahead don’t mean very much. After all, polls historically haven’t been very reliable at this stage of the campaign; just ask past frontrunners like Howard Dean, Rudy Giuliani and Herman Cain.

Furthermore, the theory (which heavily overlaps with “The Party Decides” hypothesis that we discuss frequently at FiveThirtyEight) implies that there’s no need for the GOP establishment to panic since it will probably win in the end. There are lots of campaigns that look chaotic until the first few states vote, but don’t wind up being all that close. Establishment-backed candidates such as John Kerry in 2004 and John McCain in 2008 rocketed into a strong position after the first few states voted and never really looked back. So did Romney in 2012, after a couple of bumps in the road.

If this theory is right, there are already several credible establishment candidates in the race, so there isn’t really need for another one. Thus, supporting Romney would be superfluous at best. And at worst, it would risk backtracking for an establishment that is increasingly coming to a consensus around Rubio and has several backup options (like Bush and Christie) should Rubio falter.

Theory No. 2: “This time is different”This theory is just the opposite; it posits that those polls showing Trump and Carson ahead are the latest sign that Republicans are in disarray and that the Republican grassroots is rejecting the establishment’s ambitions.

If this is the case, the establishment might be screwed no matter what it does, but it certainly wouldn’t help to divide what remaining juice it has. Instead, the establishment would want to gird itself for a long and nasty fight. And it would want to go to battle not with a porcelain figurine of the establishment like Romney or Bush, but instead with someone who had some crossover potential: Rubio, for instance, who once was thought of as a tea party candidate, or even Ted Cruz, who for all his beefs with the GOP establishment might represent a more acceptable choice to them than Carson or Trump.

Theory No. 3: “Republicans just haven’t met the right guy/girl yet”Under this theory, there isn’t anything systematic going on. Rather, the failures of the current establishment candidates reflect their failings as individuals. Bush is too moderate and a rusty, “low-energy” campaigner, the theory might hold. John Kasich, despite having good credentials, has adopted an ill-advised strategy that has him running too far to the left. Scott Walker was a gaffe machine whose retail skills didn’t translate beyond Wisconsin’s borders. Rubio? The jury’s still out, but he may be too young (read: too much like Barack Obama) and his support for immigration reform could come back to haunt him.

In this case, Romney would make some sense. He’s already shown he has the stuff to win a Republican nomination, after all. And he retains a reasonably good image with the party, with a 74 percent favorable rating among Republicans in a poll conducted late last year.1

The problem with this theory is that it’s the least plausible of the four, statistically. Sure, some candidates with good credentials on paper — Ed Muskie or Phil Gramm, for example — prove to be duds on the campaign trail. Imagine that 50 percent of otherwise-well-qualified candidates are duds.2 How likely is it that Bush and Kasich and Rubio and Walker and Chris Christie and Bobby Jindal and Rick Perry are all duds simultaneously? (Not to mention all the other plausible establishment contenders in the GOP’s historically deep and well-qualified field.) Not very likely at all; it would be equivalent to flipping “tails” on a fair coin seven times in a row, the probability of which is 1-in-128.

Furthermore, it’s not as though Romney is a once-in-a-generation political talent along the lines of Bill Clinton or Ronald Reagan. Instead, his performance against Obama was no better than might be expected (and perhaps a bit worse) on the basis of economic conditions, and Republicans were constantly fretting about his political skills four years ago.

So to recap: So far we have two theories under which a Romney campaign would be somewhere between pointless at best and counterproductive at worst. And we have a third theory which relies on an implausible reading of the evidence. It’s not looking very good for the Mittster.

But there’s a fourth theory under which Romney could possibly help the GOP.

Theory No. 4: Chaos TheoryI’m going to get a little philosophical here. Both journalists and academics tend to prefer deterministic explanations of presidential campaigns. Sure, their outcomes might not be so easy to predict ahead of time. But, this position holds, that only reflects our imperfect knowledge of the initial conditions; once we observe the outcome, we know that the campaign was destined to turn out as it did.

But what if campaigns are not merely hard to predict but are actually a little random? Or perhaps even a lot random? Change one small thing just slightly — a debate moderator allows a follow-up response instead of nixing one; a candidate gets food poisoning on the eve of an important primary — and the outcome winds up being not just a little bit different but potentially way different.

I don’t think this idea holds up so well for general elections, where a good percentage of voting can be explained by partisanship, incumbency, economic conditions and other “fundamental” factors. But nomination races are different; they may literally3 be a bit chaotic. Timing and momentum can matter a lot: In 2012, for instance, Rick Santorum may have benefited from a lucky poll that triggered favorable media coverage and helped him to break his deadlock with other conservative candidates and win the Iowa caucus. That Iowa showing, in turn, helped to make Santorum the principal alternative to Romney, and he remained in the race until April. Absent that poll, Santorum might have been out of the race as fast as Michele Bachmann.

The more candidates who are running, the more potential for chaos. Walker’s abortive campaign, for instance, may have been a result of unlucky timing and an overcrowded Republican field rather than anything major he did wrong.

Wouldn’t a Romney bid — in a field that still has 15 active candidates — invite even more chaos? Maybe, but under this theory, the GOP is probably unlucky to have wound up in a world where Trump and Carson are doing so well. Doing something to shake the campaign up could be a good risk, therefore. Furthermore, Romney would potentially begin his campaign with a lot of momentum. He was polling at about 20 percent of the GOP field when he was considering a bid last winter. If he started out in the same place now,4 he’d be at or near the top of the field, which could encourage Republicans to join the bandwagon and consolidate behind him.

Sound a little risky? Absolutely. So we’ll counter chaos theory with Occam’s razor. If Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio and Scott Walker have all failed to bridge the gap between the establishment and the grassroots, bringing Willard Mitt Romney out of mothballs probably won’t help.

November 10, 2015

John Kasich Is So ‘Underrated,’ He’s Overrated

Not every debate is a “game changer.” In fact, given how overzealous the press can be in declaring events to be turning points when they prove to have little effect on the campaign, it’s probably best to assume that most debates don’t matter.

So I can’t begrudge Bloomberg’s Mark Halperin, for instance, for giving every Republican candidate a B+ to a B- for their performance in Milwaukee on Tuesday night. Our staff grades at FiveThirtyEight1 were pretty similar. We had six of the eight main-stage candidates bunched together between a B- and a C+, and we had Marco Rubio as the “winner” despite averaging just a B+.

CANDIDATEAVERAGE GRADENATE’S GRADEMarco RubioB+B+Rand PaulB-B-Ted CruzB-B+Jeb BushC+C+Carly FiorinaC+BDonald TrumpC+BBen CarsonC+B+John KasichCCPersonally, I thought that Rubio did fine but that Ben Carson and Ted Cruz did as much to advance their causes. Carson received more Google search traffic than any other candidate during the debate,2 a factor that has sometimes been a better leading indicator of polling movement than pundits’ takes on who did well, and his performance was composed after a couple of weeks of intense media scrutiny.

I’m not sure, conversely, that Jeb Bush did much to steady himself amidst a campaign that has gone badly. After promising to assert himself, Bush ranked near the bottom in speaking time and last in Google search volume.

But these are minor quibbles. Let’s instead talk about a candidate who, in addition to having a poor debate, has shown few signs of life lately: Ohio Gov. John Kasich.

We get the theoretical case for Kasich. He’s fairly moderate, but no more moderate than Bush. He’s a fresher face than Bush. And his campaigning muscles are more in shape, since he was elected and re-elected easily in Ohio in 2010 and 2014 (Bush has not run a campaign in more than a decade).

You might expect, given how much Bush is struggling, that Kasich would be surging, at least with a certain type of Republican voter.

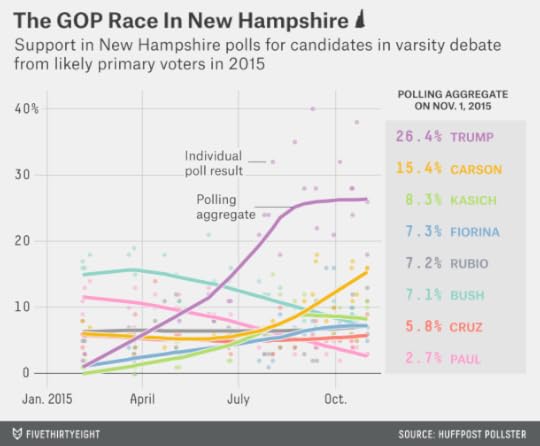

But after a few premature pronouncements over the summer that Kasich’s campaign had “momentum,” there are few signs of it now. He moved up in the polls in New Hampshire in July and August after running a blitz of advertisements there, but his standing has topped out at about 8 or 9 percent, and has perhaps even declined slightly from his late-summer peak:

Meanwhile, Kasich’s favorability ratings are getting worse in New Hampshire: He had a net favorability rating of just +5 percentage points in a recent WBUR poll, down from +24 in September. Kasich’s favorability ratings are a little better in the Monmouth poll of New Hampshire, but the trajectory is still well down from September.

The reason may be that Kasich, like Jon Huntsman four years ago, is spending too much time in the media bubble. The predominately center-left political press may like the substance of what Kasich is saying — his positions on gay marriage and Medicaid, for instance — and then forget how little they have in common with Republican primary voters.

I’d thought that Kasich might be engaged in an elaborate tactical bank shot. First, get on the radar screen by any means necessary. Run a ton of ads in New Hampshire six months before anyone votes there? Sure! Cozy up to the center-left media? Some coverage is better than none! Deliberately emphasize your moderate positions on the debate stage, so as to at least stand out from the other 16 candidates? Well, why not!

But part two of the strategy, I’d assumed, would be a pivot — once he had found his footing, he would move back to the right. Kasich was conspicuously not doing that in Milwaukee, however. Instead, he was going out of his way to pick fights with other Republicans, usually to prove how moderate he was.

Maybe that pivot is still coming — there’s still time in New Hampshire, especially if someone like Carson wins in Iowa. But Kasich’s declining numbers in the state are a sign that he may already have worn out his welcome.

Check out our live coverage of the Republican debate.

Just Win, Baby (And You’ll Probably Make The College Football Playoff)

Last season’s first-ever College Football Playoff might have miscalibrated everyone’s sense of what it takes to make it to the final four. Six power conference champions or co-champions1 — Alabama, Baylor, Florida State, Ohio State, Oregon and TCU — were undefeated or had one loss against reasonably good schedules. There’s plenty of room to critique how the committee went about leaving Baylor and TCU out, but there was no one inherently correct way to slot six fairly equally matched teams into four playoff positions.

But a field as crowded and qualified as last year’s was atypical. Most of the time there are a couple of teams that are weak links: a three-loss conference champion here, a one-loss team that played an incredibly weak schedule there. A mess like last year’s isn’t impossible, obviously. But usually the knot will untangle itself through conference championships, rivalry games and upsets that knock teams out late in the season.

So don’t despair, Michigan State fans. (Of which I’m one.) Yeah, you probably lost on a bad call last weekend. But you’re still highly likely to make the playoff if your team wins all of its remaining games, in which case you’ll have defeated Ohio State and (probably) Iowa in the Big Ten championship. Pretty much every one-loss team from a power conference is more likely than not to make the playoff if it wins out.

And an undefeated power conference team like Oklahoma State shouldn’t fret, even if it is currently outside the committee’s top four. Some of the teams ranked in front of it are almost certain to lose — and even if they don’t, there’s a good chance Oklahoma State will leapfrog some one-loss teams if it keeps winning.

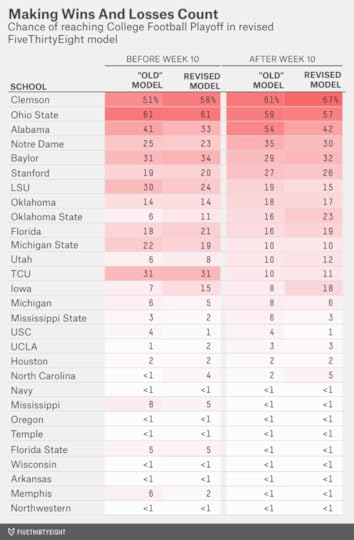

Our subjective perceptions of the playoff picture aren’t the only thing that may be miscalibrated, though. The same could be said about the FiveThirtyEight College Football Playoff model. At least, that’s the conclusion we came to when we were conducting research for this article. Although the model seems to give basically reasonable answers, a couple of things left us scratching our heads when we examined it more deeply.

For instance, it posited a conspicuously large gap between Iowa’s chance of winning the Big Ten championship (27 percent) and making the playoff (8 percent). Iowa is undefeated, and while it’s possible they could win the Big Ten with one loss or more, the internal calculations in the model also implied that they’d have only about a 55 percent chance of making the playoff even if they ran their record to 13-0. One can see why a computer might come to that conclusion — Iowa has played a pretty bad schedule, and its margin of victory hasn’t been impressive — but human beings are going to vote an undefeated Big Ten champion into the playoff unless almost everything else2 is working against them.

Readers had some questions for us too. Why was USC, which already has three losses, given any realistic chance by the model (granted, it was just 4 percent) of making the playoff? And why was one-loss Alabama’s chance of making the playoff so much higher than its SEC championship chances? There are some good reasons for that one,3 but even accounting for those, the gap seemed to be too wide and the model seemed to be too optimistic about Alabama still making the playoff if it endured a second loss.

The theme here is that human beings pay a lot of attention to wins and losses — more than our computer seemed to be doing. An undefeated power conference team is going to get in except under rare circumstances. Two-loss power conference teams have historically finished in the AP top four more often than you might think, but it’s still a hard road. And a three-loss team making the playoff? Almost impossible unless there’s total carnage everywhere else.

Since the whole point of our model is to mimic human intuition, reader feedback made us think it had some blind spots. So we re-examined the historical data4 and concluded that our model should be placing more weight on plain-vanilla wins and losses. Or at least, it should be doing so for power conference teams (and for Notre Dame); minor conference teams historically haven’t been treated that kindly by either poll voters or the committee. Even if the committee currently ranks a one-loss team ahead of an undefeated team, or a two-loss team ahead of a one-loss team, it may re-examine the case in future weeks, and the team with fewer losses will often get the benefit of the doubt. (For a more technical explanation of how this is implemented in the model, see the footnotes.5)

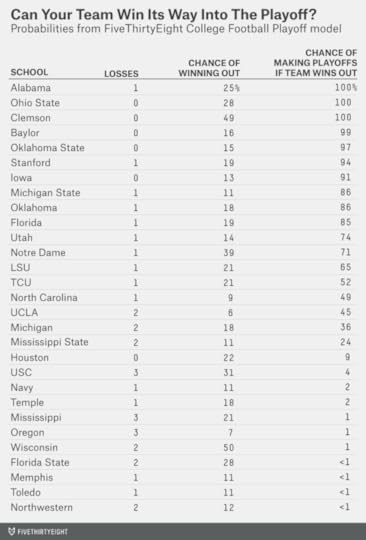

This relatively simple change has little impact for most teams, but it does affect a couple of the cases that had bothered us (and some of our loyal readers). Iowa’s chances of making the playoff are now 18 percent instead of 8 percent. Alabama’s are 42 percent instead of 54 percent. USC’s are 1 percent6 instead of 4 percent. Here’s how everyone’s odds were affected by the change:

And here’s a new summary table showing the playoff picture heading into tonight, when the playoff committee will release its new rankings at 7 p.m. Undefeated Baylor has moved slightly ahead of one-loss Notre Dame in our forecast, but otherwise the top six are unchanged.

RankingProbability of …TeamCFPEloFPIConf. TitlePlayoffNat. Title Clemson 9-013667%67%17%

Clemson 9-013667%67%17% Ohio State 9-032544%57%15%

Ohio State 9-032544%57%15% Alabama 8-141435%42%12%

Alabama 8-141435%42%12% Baylor 8-067234%32%12%

Baylor 8-067234%32%12% Notre Dame 8-1569—30%7%

Notre Dame 8-1569—30%7% Stanford 8-11151152%26%5%

Stanford 8-11151152%26%5% Oklahoma St. 9-01441337%23%5%

Oklahoma St. 9-01441337%23%5% Florida 8-110101438%19%3%

Florida 8-110101438%19%3% Iowa 9-09132927%18%2%

Iowa 9-09132927%18%2% Oklahoma 8-11514119%17%7%

Oklahoma 8-11514119%17%7% LSU 7-129814%15%4%

LSU 7-129814%15%4% Utah 8-112112122%12%2%

Utah 8-112112122%12%2% TCU 8-1812310%11%4%

TCU 8-1812310%11%4% Michigan St. 8-1782212%10%1%

Michigan St. 8-1782212%10%1% Michigan 7-217201613%6%1%

Michigan 7-217201613%6%1% North Carolina 8-1—182030%5%

North Carolina 8-1—182030%5% Mississippi St. 7-22016153%3%

Mississippi St. 7-22016153%3% UCLA 7-22321186%3%

UCLA 7-22321186%3% Houston 9-025223633%2%

Houston 9-025223633%2% USC 6-3—19719%1%

USC 6-3—19719%1% Wisconsin 8-2—17243%

Wisconsin 8-2—17243% Temple 8-122283943%

Temple 8-122283943% Mississippi 7-31826109%

Mississippi 7-31826109% Navy 7-1—155419%

Navy 7-1—155419% Florida State 7-21624170%

Florida State 7-21624170% Memphis 8-11331453%

Memphis 8-11331453% Northwestern 7-2212961

Northwestern 7-2212961 Toledo 7-12440539%

Toledo 7-12440539% Texas A&M 6-3194923College Football Playoff (CFP) rankings as of Nov. 3.

Texas A&M 6-3194923College Football Playoff (CFP) rankings as of Nov. 3.

But back to football substance. I mentioned before how lots of teams, even if they don’t technically control their own destiny,7 are favored to make the playoff if they win the rest of their games. Now that the model is (hopefully) doing a better job of mimicking the emphasis that human voters place on wins and losses, we can be more precise about that. Specifically, the model estimates that 14 teams have a 50 percent or greater likelihood of making the playoff conditional on winning out.

The model figures that Michigan State, for instance, has an 86 percent chance of making the playoff if it wins out. Even the lowliest one-loss major conference team, North Carolina, which wasn’t ranked by the committee last week, is about even-money to make the playoff if it wins out. And undefeated Iowa (91 percent) and Oklahoma State (97 percent) are all but assured of making the playoff if they finish the year without a loss, even if the committee doesn’t have them in the top four tonight.

So the tough part for teams like Michigan State isn’t sweating the committee’s decision if it wins the Big Ten; it’s getting to that point in the first place. With Ohio State and Iowa still in the way; the Spartans have only an 11 percent chance of running the table.

November 9, 2015

Does Trump, Cruz Or Rubio Have the Best Pre-Debate Chance?

With the fourth Republican debate happening on Tuesday, we used this week’s politics Slack chat to check in on the state of the GOP primary. But this is FiveThirtyEight, so instead of just spouting off on the race, we played one of our favorite games: “Buy/Sell/Hold.” As always, the transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): It’s been awhile since we’ve played “Buy/Sell/Hold” for the GOP primary. So, let’s play! The rules, as always: I give you the chances for each candidate as implied by the current betting line on Betfair.com, and you have to decide whether to buy/sell/hold stock in that candidate given that price.

OK, Nate and Harry, we’re going in reverse alphabetical order! First up: Donald Trump with an 18.7 percent chance to win the GOP nomination — buy/sell/hold?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): First of all, I just want to say that as someone with a late-alphabet last name, I support reverse alphabetical order.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Very nice. And as someone with a brain, I support selling Trump at 18.7 percent.

natesilver: I’m a sell at 18.7 percent, indeed. Trump has risen quite a bit over at Betfair over the past month or so, which I’m not sure makes sense.

harry: It’s people seeing the calendar go by and Trump still doing decently well in the polls.

micah: Yeah, isn’t the logic something like, “The longer he sits atop the polls, the more REAL Trump’s support is”?

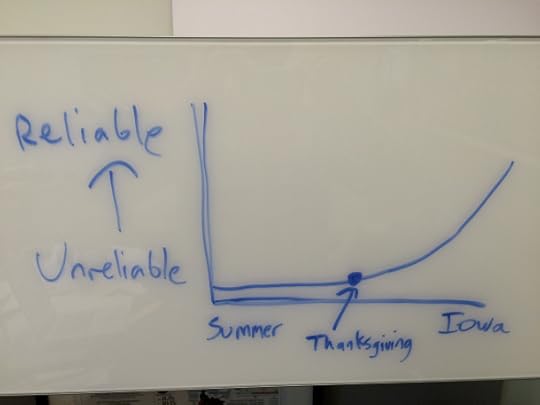

natesilver: But as we emphasize a lot around here, political time is not linear. What you say is true narrowly speaking. I don’t think anybody, us included, is saying Trump has literally zero chance. And those chances will rise the longer he maintains his position in the polls. But polls in early November aren’t particularly more informative than those in October or September or August or July.

harry: Most people are planning Thanksgiving and their Christmas shopping. They still aren’t paying all that much attention.

micah: I vaguely remember one of you saying in a previous chat to start paying more attention to the polls after Turkey Day?

natesilver: Yeah, we’ve mentioned Thanksgiving as a point when the polls start to get more interesting. Historically, that’s about when you begin to see much more widespread interest in the campaign.

harry: We still had time for a Newt Gingrich boom and bust after Thanksgiving last election, and the Iowa caucuses are a month later in 2016 than they were in 2012. Anyway, the point is that Trump is vastly overvalued at 18.7 percent for someone who has such a low net favorability rating among Republicans.

natesilver: re: Thanksgiving, I’m just saying that’s an inflection point at which the reliability of the polls begins to increase. Not saying that they instantly go from meaningless to meaningful. Here let me draw a graph.

[Nate gets up and draws on his office whiteboard.]

micah: All right, next: Rick Santorum with a 0.2 percent chance — buy/sell/hold?

natesilver: At 500-1? Sure. Buy a few shares.

harry: I mean, I think I’m buying here. I think he’s probably closer to something like 200-1? Maybe even 100-1?

harry: Win in Iowa and then who knows what happens?

micah: Marco Rubio with a 38.6 percent chance of winning the GOP nomination — buy/sell/hold? According to Betfair, Rubio has the best chance of winning by a wide margin. (I’d sell at that price.)

harry: I think I’m also selling. It’s not that he doesn’t have the best chance; he does. It’s that I would be closer to 30 percent or 33 percent. There are still far too many unknowns. Can he raise enough money? Can he convert high net favorability ratings into actual votes? Can he continue racking up endorsements? He’s still behind Bush in the endorsement race.

natesilver: I’m buying at 38.6 percent, although I don’t think I’m getting a great bargain.

micah: You’re in the tank for Rubio.

natesilver: If I know you guys as well as I think I do, you’re going to be selling or holding a lot of the other candidates. Unless you’re really bullish on Jeb Bush or Trump or Ben Carson, it’s hard to get the numbers to add up to 100 percent unless you have Rubio in the 40 percent range or above. But more importantly, we have seen some signs of progress for Rubio. He’s one of only two Republicans to have received any endorsements in the past few weeks. He’s lined up some big super PAC backers. His favorability ratings remain strong.

micah: Some signs, sure, but it’s all mostly potential still.

harry: Right, lots of potential. Rubio is a hot commodity these days, but sometimes you get berned.

micah: I think we’re all high on Rubio’s chances, but I think the hype has outpaced the reality at this point.

natesilver: The fact that there’s a meme out there that the hype has outpaced the reality makes it less likely he’s overvalued in the market.

micah: Is that really a meme?

harry: Yeah, what meme is that? Is it just in this office?

micah: I just want to see a really good fundraising quarter or a bunch of endorsements (more than the five he’s gotten in the past week). Or for him to even shoot up in the polls, as meaningless as they are.

Anyway, Rand Paul at 0.6 percent — buy/sell/hold?

natesilver: I was making the ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ motion.

harry: Buying at 0.6 percent. I’ll go to 1.2 percent. I mean, who the heck knows? Maybe there’s a government scandal involving drones or something.

micah: Yeah, I’d buy to like 3-4 percent.

natesilver: I guess I’m a hold, and I’d be a sell if you forced me to pick. Even at that very cheap price. He’s doing miserably in the polls. And the GOP primary electorate has moved away from libertarianism toward Trumpism so far this cycle.

harry: Right, but as you yourself have said, Nate, things can change. The electorate may be in a different place three months from now.

natesilver: To me, it’s a big assumption that Paul will even be around in three months. He’s risking damaging his brand and possibly inviting a primary challenge by staying in the race.

harry: His main Democratic challenger for his Kentucky Senate seat has already said he’s not running.

I just think lightning could strike.

micah: Lots of disagreement so far! Now we get to the big guns: George Pataki at 0.1 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: Sell.

natesilver: SELL.

harry: He’s pro-choice; he can’t win a GOP presidential primary.

natesilver: He was mayor of Peekskill, New York, which is a lovely town.

micah: John Kasich at 2.3 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: Buying. I’d even go double or triple that, potentially.

natesilver: Yeah, that seems cheap on Kasich. Even if he’s overrated by Acela Republicans. To me, the flowchart is something like this: Rubio will get his trial run as the establishment front-runner. If he fails in that role, people will look at Kasich, Chris Christie, Bush a second time, maybe even Mitt Romney, etc.

harry: Yeah, I gotta agree. Kasich came in very hot, and now he has cooled. But with a Christian conservative having a good shot in Iowa, New Hampshire becomes paramount. Maybe Kasich can break through there.

micah: And Jeb’s struggles help Kasich as much as anyone, right? (save Rubio, maybe?)

harry: Jeb’s struggles help Kasich, Rubio and Christie.

micah: OK, Bobby Jindal, 0.6 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: Again, I’m buying. Here’s why. He has high net favorability ratings in Iowa, and with so many candidates, who knows?

natesilver: I’m buying, I guess, although not as eagerly as Harry. Jindal has blown a couple of big chances in the debates. It’s not clear that he has the retail skills.

harry: He’s 0.6 percent. If he were at 6 percent, then I’d be selling.

natesilver: I mean, if you can’t out-debate Pataki, Santorum and Lindsey Graham, that’s sort of the politics version of hitting below the Mendoza Line.

micah: Mike Huckabee at 0.8 percent?

harry: Buying. Same reasons as with Jindal, and Huckabee once won 20 percent of the national primary vote. Plus, Huckabee can be a very good debater.

natesilver: I guess I’m buying. But I just want to re-emphasize that if someone “should” be at (say) 1.5 percent instead of 0.8 percent, they’re a solid buy but still aren’t going to shift the overall odds very much.

micah: Lindsey Graham — 0.3 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: I’m selling.

natesilver: I’m not buying.

micah: Does that mean you’re holding?

natesilver: It’s a shold for me.

micah: I’m sholding on the word “shold.”

Carly Fiorina with a 1.2 percent chance — buy/sell/shold?

natesilver: Buy.

harry: Buying too.

micah: Up to?

natesilver: Uhhh, 3 percent maybe? She clearly wasn’t able to sustain very much momentum after her sterling performances in the debates. And it’s not clear how interested she is in building out a real campaign architecture. Still, her favorability ratings are fairly good, and she’s a plausible (not saying likely) establishment vs. outsider compromise choice.

Let me also note that I would have assigned only a 3 percent chance to my being able to eat this bowl of ramen without spilling on myself, and I just pulled that off. So sometimes the long shot comes through.

harry: I’m with Nate on this. I’m not sure there is much to add. I will say Fiorina has gotten a few endorsements. So it’s not a totally lost cause.

micah: Ted Cruz with a 10.3 percent chance of winning the Republican nomination — buy/sell/hold?

harry: Holding, I think. He’s quite conservative, yes, but there’s room for him given the divided field and his high favorability ratings

natesilver: Holding. He was a bargain a few weeks ago, but he’s been bid up quite a bit since.

I think there’s a pretty good chance that Cruz has an influence on the race at some point and could emerge as the leading “insurgent” alternative. But having an influence on the race is not the same thing as winning it.

Also on Cruz, I suspect his Harvard-debate-team style is going to rub a few voters the wrong way. It’s not fatal by any means, but it’s one thing working against him. And it’s interesting that he didn’t move up in the polls as much as some people expected after the previous debate.

harry: Of course, Rubio didn’t really move up much either.

micah: Chris Christie at 3.1 percent?

harry: If I don’t buy after the piece I just wrote, I should be put out to pasture.

natesilver: I’m a buy, but a weak buy. I can see Harry’s case for Christie. But fundamentally, he still has a LOT of problems — too moderate, has lost his luster with independent voters, not seen as a party guy, and the whiff of vetting issues.

Like Cruz, he’s a guy who could have a surge at some point but have it prove to be unsustainable.

With that said, having the stage sort of to himself in the JV debate is an opportunity.

harry: Yes. It’s a buy, but not a strong buy.

micah: Ben Carson 6.5 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: Selling.

natesilver: If past patterns are any indication, he’s about to surge to 42 percent in the polls.

micah: Because of the fracas over alleged misrepresentations in his life story?

natesilver: Yeah, after being ganged up on by the media.

micah: You think there’s a lot of smoke but no fire?

natesilver: I think whoever set the campfire did so sloppily. So maybe there are a few embers, but it looks bad. (This metaphor is rapidly going to hell.)

I suppose I don’t think there should be such a big spread between Trump’s chances and Carson’s chances at Betfair.

harry: Reminder: Even before this whole thing with pyramids and fires and whatever it is y’all are getting at, Carson had little shot at winning the nomination. Neither does Trump.

natesilver: Anyway, I’m a shold on Carson.

micah: Last but not least, Jeb Bush at 9.6 percent — buy/sell/hold?

harry: I’m buying. I know, I know — how could I buy on the man whose debate performances remind me most of the Mets’ World Series defense. But he’s still got the most endorsements. He still has a lot of super PAC cash. So I’d go higher than 9.6 percent. Not much higher, but higher. Let it be known, however, that his chances have dropped at least in half over the last two months.

natesilver: When I was putting together my subjective odds, I had him at 9 percent. So that’s a hold, I guess. Bush has gotten barely any endorsements since Labor Day. They’re mostly a relic of an earlier period and the promise his campaign failed to live up to.

harry: Only Rubio has picked up the slack … and not by that much. At least as of yet.

natesilver: At the pace he’s been on recently, Rubio will surpass Bush within a week or two. But here’s the other thing. Republicans don’t have a good reason to choose Bush. His fundamentals aren’t that strong. He’s not with them ideologically, and his electability credentials are meh.

harry: It comes down to New Hampshire.

micah: All right, to close us out here, give me all your subjective odds.

Here are mine:

Jeb Bush — 10 percent

Ben Carson — 5 percent

Chris Christie — 6 percent

Ted Cruz — 14 percent

Carly Fiorina — 5 percent

Lindsey Graham — 1 percent

Mike Huckabee — 1 percent

Bobby Jindal — 4 percent

John Kasich — 10 percent

George Pataki — 1 percent

Rand Paul — 3 percent

Marco Rubio — 30 percent

Rick Santorum — 1 percent

Donald Trump — 5 percent

Other — 4 percent

natesilver:

Bush — 9 percent

Carson — 6 percent

Christie — 5 percent

Cruz — 10 percent

Fiorina — 3 percent

Graham —

Huckabee — 1 percent

Jindal — 1 percent

Kasich — 8 percent

Pataki —

Paul — 1 percent

Rubio — 45 percent

Santorum — 1 percent

Trump — 6 percent

Other — 4 percent

harry:

Bush — 13 percent

Carson — 4 percent

Christie — 6 percent

Cruz — 10.3 percent

Fiorina — 5 percent

Graham — 0.1 percent

Huckabee — 3 percent

Jindal — 2 percent

Kasich — 8 percent

Pataki — 0 percent

Paul — 1.2 percent

Rubio — 33 percent

Santorum — 1.2 percent

Trump — 5 percent

Other — 8.2 percent

November 5, 2015

We Have (Almost) No Idea What The Economy Will Look Like On Election Day

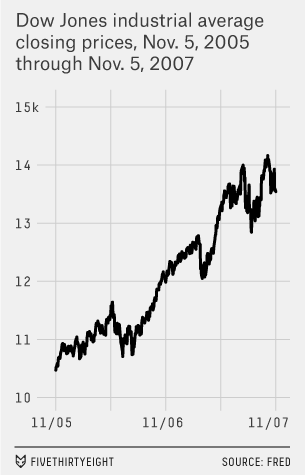

There’s almost exactly one year to go until Election Day 2016. But I want to wind the clock back eight years, to Nov. 5, 2007.

What were the headlines that day? According to the news aggregator Memeorandum, the most talked-about national stories were the confirmation of Michael Mukasey as attorney general and the increasing unrest in Pakistan. There was also the typical litany of campaign stories, particularly about the growing rivalry between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, who were both serving in the U.S. Senate and running for the Democratic presidential nomination.

But there was very little about the economy, even though it was about to become the focal point of the campaign. The Dow Jones industrial average, for instance, was doing fine, having wobbled a bit from its October highs but still having risen by about 13 percent year over year.

Just one month later, however, the economy would be in recession1 — indeed, in the midst of the worst recession since the Great Depression as part of a global financial crisis whose aftereffects are still being felt today.

Could we find ourselves in equally dire straights by this time next year — in the midst of a severe economic crisis that few people saw coming?

Well, maybe. There were some warning signs by November 2007; the subprime mortgage sector was already in distress, and there were some voices in the wilderness suggesting that it could have dire consequences for the economy. But that wasn’t the consensus view of policymakers or forecasters. Instead, the forecasting survey put out by The Wall Street Journal in November 2007 called for slower-than-usual growth but assigned only a 1 in 3 chance of a recession.2

Indeed, economists have shown very little ability to forecast the direction of the economy more than six months in advance. As I wrote in my book, the historical margin of error associated with GDP forecasts made a year ahead3 is plus-or-minus a whopping 4.6 percentage points. By this time next year, the economy could be back in recession — or in the midst of a “Morning in America” resurgence.

And because the economy is so important to presidential campaigns,4 events in China or Greece or the American oil boom, which few political observers are paying much attention to today, could prove to be the real “game changers” in the election.

November 3, 2015

Here’s How Our College Football Playoff Predictions Work

Are you ready for some football? Or at least, some vociferous arguing about football?

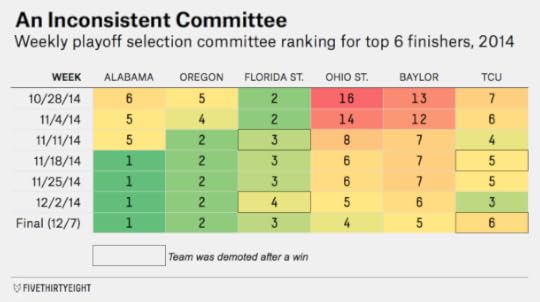

Last season’s first-ever College Football Playoff taught us two things. First, going from a championship game to a four-team playoff won’t end the annual bickering over which teams belong. Second, the playoff selection committee seemingly takes a different approach than voters traditionally have in the coaches’ and media polls. In particular, they are more willing to scramble teams’ positions from week to week, even when everyone wins out.

Florida State, for instance, despite never losing during the regular season, moved from No. 2 in the committee’s initial rankings to No. 4 on Dec. 2, before being upgraded to No. 3 in the committee’s final rankings on Dec. 7. More consequentially, TCU dropped from No. 3 to No. 6 — and out of the playoff — in the committee’s final rankings despite having won its final game over Iowa State 55-3. Historically, it’s unusual in the coaches’ and media polls for a team to lose ground after winning a game, and there’s almost no precedent for a team dropping three spots, as TCU did.

You can spin all of this as a good thing (“the committee starts with a blank slate every week and gives each team a fair shake!”) or a bad one (“the committee is inconsistent and indecisive!”). Either way, it has implications if you’re trying to anticipate the committee’s next move — as we, like so many other college football fans, are foolishly trying to do.

Our way is pretty geeky and statistical, of course. Last season, we introduced a model that simulated the rest of the college football season and sought to forecast which four teams would make the playoff. We described the model as “speculative” since the committee was a new thing, giving us no historical data to measure its behavior; instead, we used the historical behavior of voters in the coaches’ poll as a substitute.

For several weeks, the model seemed to be uncannily accurate! Then … a (mild?) disaster. Our final set of simulations gave TCU a 91 percent chance of making the playoff, Florida State a 68 percent chance, and Ohio State a 40 percent chance. But TCU, the safest bet according to the model1, was the one left out.

While we could have sheepishly attributed this result to “bad luck” — a 91 percent chance isn’t a 100 percent chance — we don’t think that’s the right conclusion here. Instead, after a year’s worth of experience under our belts that let us see how the committee works, we’re making a couple of revisions to the model:

First, we account for the committee’s potential to scramble the ratings slightly from week to week, even where the on-field action didn’t seem to warrant it, such as in its flip-flopping of Florida State and TCU last year. The mechanics of this are a little involved; I’ll describe them briefly down below.Second, we assign a small bonus2 to conference champions.3Third, the model accounts for slightly more uncertainty than in last year’s version.These aren’t huge changes — the backbone of the model is the same as last year — but for what it’s worth, the revised version of the model would have correctly predicted the top four seeds last season, and in the right order. (Both Florida State and Ohio State would have been projected to leapfrog ahead of TCU in the committee’s final standings.) I say “for what it’s worth” because it’s not very much of an accomplishment to “predict” something after it’s already happened. But having one year’s worth of data on the committee’s behavior is a lot better than none.

The model works by simulating out the rest of the season thousands of times. It’s iterative, meaning that it does this week by week. The process works like this:

Start with Week 10 committee standings.Simulate Week 10 games.Forecast how Week 11 committee standings will change in response to simulated Week 10 games.Simulate Week 11 games.Rinse and repeat until you get to the final committee rankings on Dec. 6.The model also simulates conference championship games and the four-team playoff itself. Thus, it provides a probabilistic estimate of each team’s chances of winning its conference, making the playoff, and winning the national championship.

We’ll be updating the numbers twice weekly: first, on Sunday morning (or very late Saturday evening) after the week’s games are complete; and second, on Tuesday evening after the new committee rankings come out. In addition to a probabilistic estimate of each team’s chances of winning its conference, making the playoff, and winning the national championship, we’ll also list three inputs to the model: their current committee ranking, FPI, and Elo. Let me explain the role that each of these play.

RankingProbability of …TeamCFPEloFPIConf. TitlePlayoffsNat. TitleOhio State31447%61%16%Clemson17756%51%12%Alabama42614%41%11%TCU84237%31%11%Baylor610132%31%13%LSU25822%30%8%Notre Dame589—25%5%Michigan State731915%22%3%Stanford1161346%19%3%Florida1091241%18%4%Oklahoma1516315%14%5%Mississippi18171020%8%2%Iowa9122925%7%Michigan1722187%6%Oklahoma St.14111415%6%1%Utah12152118%6%Memphis13143621%6%Florida State16131513%5%USC—20530%4%1%Mississippi St.2019173%Houston25233330%2%UCLA2321225%1%North Carolina—262323%Toledo24244328%Temple22324541%Oregon—2532Wisconsin—18245%Texas A&M193016Arkansas—3926Penn State—2741Northwestern214257

Remember: the committee rankings are a starting point for the model and not the ending point. At this relatively early point in the season, the committee standings won’t matter very much; there are too many opportunities for the teams to be scrambled later on. (Consider, for instance, that eventual national champion Ohio State started out at No. 16 last year.) They’ll tend to matter more as the season goes along, although, as we saw with TCU last year, nothing except for the committee’s final rankings are all that definitive.

FPI is ESPN’s Football Power Index. We consider it the best predictor of future college games so that’s the role it plays in the model: if we say Team A has a 72 percent chance of beating Team B, that prediction is derived from FPI. Technically speaking, we’re using a simplified version of FPI that accounts for only each team’s current rating and home field advantage; the FPI-based predictons you see on ESPN.com may differ slightly because they also account for travel distance and days of rest.

But if FPI is good at predicting, it’s not very “politically correct,” meaning that it deliberately doesn’t care about how human beings might rank the teams. For instance, FPI currently has a USC with three losses as the fifth best team in the country — ahead of undefeated Clemson! Committee voters would never do that.

Instead, that’s the role that our college football Elo ratings play. If you’re familiar with FiveThirtyEight, you’ll be familiar with Elo ratings. They’re a simple mathematical system that form the basis of our NFL forecasts, for instance. We’ve also applied Elo to soccer, the NBA, basketball and other sports.

Our college football Elo ratings are a little different, however. Instead of being designed to maximize predictive accuracy — we have FPI for that — they’re designed to mimic how humans rank the teams instead.4 Their parameters are set so as to place a lot of emphasis on strength of schedule and especially on recent “big wins,” because that’s what human voters have historically done too. They aren’t very forgiving of losses, conversely, even if they came by a narrow margin under tough circumstances. And they assume that, instead of everyone starting with a truly blank slate, human beings look a little bit at how a team fared in previous seasons. Alabama is more likely to get the benefit of the doubt than Vanderbilt, for example, other factors held equal.

How do Elo ratings help the model? As it plays out each week of the season, the model forecasts each team’s new projected ranking based on a combination of its committee ranking in the previous week, the game result (as simulated by FPI) and its Elo rating. In other words, Elo ratings form a counterbalance against the committee rankings, which as we’ve seen can be subject to change. Last year, for instance, Elo had Florida State ranked very highly: As an undefeated returning national champion, the Seminoles had the profile of a team that human voters typically love. Elo also had Ohio State ranked highly, well ahead of TCU. Thus, the model wouldn’t have been so surprised that Florida State and Ohio State jumped ahead of TCU in the final standings.5

If the rankings still look a little off to you — if you can’t quite figure out how a team gets to where it does based on Elo, FPI and its current committee ranking — there’s one other likely culprit, which is a team’s future strength of schedule. LSU, for instance, is given only a 30 percent chance of making the playoff in part because they have a brutal schedule ahead, with games against Alabama (this weekend), Mississippi and Texas A&M — plus a potential SEC Championship game against Florida. If a team has already taken a loss or two and is currently out of the running, however, a tougher upcoming strength of schedule may help it, because it means that the team has more opportunities to impress the committee and get it to reconsider.

Most importantly of all, there’s still a lot of football left to be played. It’s hard for any team to run the table, and even current front-runners like Ohio State and Baylor won’t be safe if they endure a loss. Thus, only two teams (Ohio State and Clemson), start with more than a 50 percent chance of making the playoff in our initial forecast.

The Election Is A Year Away — Is Either Party Winning?

The presidential election is now officially one year away. So for this week’s 2016 Slack chat, we chewed over each party’s general election prospects. What do we know a year out? As always, the transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): All right, we’re one year out from the 2016 general election; what’s the outlook? Does either party have an advantage?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): No. Good chat, guys!

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Here’s what I would say: The generic presidential ballot shows a slight GOP advantage. YouGov has tested a generic Republican presidential candidate vs. a generic Democrat four times since the beginning of September. GOP holds a 2.25 point average lead. That suggests to me, at the least, that the Democrats do not have an advantage heading into next year.

natesilver: I’m open to explanations about why the probabilities are slightly different from 50-50. But I’m not sure why I should care about the generic ballot.

harry: Well, I think it gives us a general idea of the political environment overall. And it reflects the president’s approval rating as well. The rough line of when a president’s approval rating helps or hurts a candidate from his own party is about 48 percent.

Obama’s approval rating right now is 45 or 46 percent. Both of those numbers indicate to me that the environment is probably a little more favorable to the GOP than the Dems.

Not greatly so, but a little bit so.

natesilver: I’m not sure I’d say that 45 or 46 percent is meaningfully different from 48 percent. Not a year out, anyway.

If you run the numbers with Obama’s favorability ratings instead, for instance, you get a different answer.

harry: Let me ask you this: Is the difference between a 55 percent chance of the GOP winning meaningfully different than a 50 percent chance?

natesilver: Do you want me to get existential here?

micah: YES!

natesilver: Sure, it’s meaningful if it really were a difference between 55 percent and 50 percent. Something that made a 5 percentage point difference in the likelihood of Democrats or Republicans winning would be way more meaningful than 99 percent of the stuff that pundits call “game-changers.”

However.

These fundamentals-based presidential models kind of suck. They’re not nearly as precise or as accurate as they claim to be.

harry: Most of those fundamental models are based off economic measures. I don’t think I put any economic numbers in this so far.

natesilver: I guess I look at it more like this. My prior is that elections with a term-limited incumbent are 50-50. I’m looking for evidence that persuasively overcomes that prior. An extremely popular or extremely unpopular incumbent would clearly matter. But Obama’s popularity is about average.

micah: But this was one of my questions: Obama isn’t running; how much of an effect will he have on the race? Positive or negative — is Obama’s popularity really a big factor?

natesilver: He’ll have a fairly neutral effect, given his current popularity level.

harry: We only have approval rating data at this point in a campaign (September/October the year before) for six instances when an incumbent president didn’t run for re-election. Now, I took those and plugged them into a simple little regression. With Obama’s approval at 46 percent, the GOP is expected to win by about 2 percentage points. Again, there’s a huge margin of error, but signs point to a slight GOP edge.

natesilver: Dude. It’s not even six examples really. It’s four.

harry: Who are your four?

natesilver: Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush are the only presidents in American history to be term-limited. Obama will be the fifth.

And I don’t care if you get the same regression results with four.

harry: And did you know that Obama’s approval rating is below the average approval rating for those four? And it’s not particularly close either.

natesilver: The problem is that running a regression model based on an n of four is inherently kind of ridiculous.

NERD FIGHT!

harry: The average approval rating of those four is 59 percent. Obama’s is 45 or 46 percent. I’m not saying this is anything close to a be-all end-all predictor.

But the evidence we do have suggests something slightly on the GOP side of 50-50.

natesilver: OK, but there’s other evidence that possibly points toward Democrats having a slight edge.

harry: Such as what? The blue wall? Your favorite blue wall?

micah: PERMANENT DEMOCRATIC MAJORITY!

natesilver: No, the blue wall is bullshit. Or, at least, mostly bullshit. But if you’re talking about minutia on the order of a 46 percent vs. 48 percent approval rating, then maybe there’s a very very small Democratic Electoral College advantage.

harry: Why do you think that advantage exists?

natesilver: Because they did have an advantage in 2012 and 2008, if you look at where the tipping point state was relative to the national popular vote.

natesilver: Those advantages are NOT very sticky from election to election. But, again, if we’re talking about shit that moves the probabilities by 5 percentage points one way or the other, then maybe?

harry: Now, let me state a point of agreement here: I concur that those advantages are not very sticky from election to election.

natesilver: It’s all minutia, and I don’t think we should be concerned about a minutia a year out.

harry: This site should be about arguing over the small stuff sometimes!

micah: All right, somewhat related question: We’ve already heard pundits and politicians say, “It’s very hard for a party to win the White House three elections in row.” I guarantee that will be said millions of times from now to November 2016. Is it true?

natesilver: The White House is not a metronome.

micah: So no?

harry: Small sample size on that one. I don’t agree with the concept that winning a third term is inherently more difficult. And, moreover, looking at the generic presidential ballot and Obama’s approval, this looks more like a close election than one that is clearly one-sided from start to end, a la 1952 or 2008.

natesilver: You have four examples of term-limited presidents. If you look for examples before the 22nd amendment was adopted (which I guess you have to do when you have a sample size of four): Elections with retiring incumbents seem to be about 50-50.

micah: Of course, who the parties nominate could change those numbers. It seems like this could be an election where the candidates make a huge difference, right? Let’s say Hillary Clinton wins, whether she faces Donald Trump or Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio will have a big effect on the odds.

natesilver: Yes. That’s the proverbial and maybe literal elephant in the room.

micah: What order of magnitude are we talking about?

harry: Yes, this is the question. This is one where I could find myself in agreement with Mr. Silver on whether it’s a 50-50. Cruz, for example, would be a historically conservative candidate. If he’s the GOP nominee, that could be worth a few percentage points and harm the Republicans.

natesilver: Which, in an election that otherwise looks about 50-50, could make a lot of difference.

If Clinton has a 75 percent chance of facing a 50-50 election, and a 25 percent chance of facing a 75-25 election (e.g., against Cruz, Carson, Trump, or a GOP electorate that gets all screwed up because one of those guys runs as a third party), then her overall chances of winning are 56 percent.

natesilver: Now, I think you can argue that Clinton would be a slight underdog against Rubio, for instance.

micah: What about vs. Jeb! Bush or John Kasich or Chris Christie?

natesilver: Sure, Kasich, in particular. I’m less sure about Jeb or Christie, just because their personal ratings have been pretty bad for a long time.

But Clinton’s not very popular either, obviously.

micah: OK, let me see if I have this right …

One year out, the election is probably about 50-50 (maybe 55-45 Republican, according to Harry), but that could be tipped toward the Democrats if the Republicans nominate Trump/Carson/Cruz or toward the Republicans if they nominate Rubio or Kasich. Moreover! Obama, with middling-but-not-horrible approval ratings, won’t have a huge effect on the race (also, the “it’s hard to win the White House three times in a row” maxim is bullshit).

harry: I think that’s mostly right, though I will say to the degree that Obama has an effect, it likely hurts, not helps, the Democratic candidate at this point.

natesilver: That’s basically right. Almost everything we’ve been talking about wouldn’t shift the probabilities much from 50-50. Maybe you can argue that slightly more of the tiebreakers line up on the GOP side instead of the Democratic side; Harry’s more convinced about that than I am, I guess.

But there’s some probability of something that would make a huge difference, which would be the GOP nominating Cruz/Carson/Trump. Or nominating an establishment candidate after a huge, messy nomination fight, that might include a brokered convention or something close to it. In those cases, Clinton — for all her flaws — is a clear favorite.

harry: Clear favorite undersells it, IMHO. (Of course, now I’m just being difficult.)

October 29, 2015

Are The Royals Really This Much Better Than The Mets?

Today is an off day for the Kansas City Royals and New York Mets, but not for us. As the teams traveled to New York City to resume the World Series on Friday with the Royals leading by two games to none, ESPN.com editor and writer Christina Kahrl joined FiveThirtyEight’s biggest baseball obsessives from her Kansas City hotel to look ahead to Game 3. As usual, the transcript below has been lightly edited.

Carl Bialik, lead news writer: Welcome, baseball fans! Historically, five out of six teams down two games to none in a best-of-seven series go on to lose. Can the Mets be the one out of six? Is there anything you see that makes that look likely?

Neil Paine, senior sportswriter: Well, according to ESPN Stats & Info, the last time the Mets were outscored by exactly seven runs in the first two games of a World Series was in 1986, and we know what happened then. (But seriously, they are in deep trouble.)

Christina Kahrl, ESPN.com editor and writer: Hrm. 1986: John McNamara, Red Sox manager and a model manager if tactical passivity is your thing. 2015: Ned Yost, Royals manager and a model manager if tactical passivity is your thing. I’m sensing a trend.

Nate Silver, editor in chief: Well, the Mets are playing at home. They probably have the best of the starting pitching matchups in Games 3 and 4, especially with Chris Young coming into Game 4 with some extra mileage on his arm.

Harry Enten, senior political writer: Let me offer this piece of hope for the Mets (because, as Neil notes, they are in trouble): The Royals are hitting at about their average through the small sample size of two games (.721 OPS vs .734 in the regular season), while the Mets are hitting quite below their average (.432 vs. .712 in the regular season).

Neil: Yeah, perhaps one ray of sunshine is that the Mets were this close to getting a split in KC, if Jeurys Familia doesn’t make that one mistake. And that was with Mets bats underperforming.

Harry: And then, surely Yost is bound to cost the Royals. Right?! Right?!

Christina: Actually, the thing you can say for Yost is that, a little like Tony La Russa in 2011 or Bruce Bochy in any World Series, he’s been working with what he’s got this postseason. Chris Young probably won’t have to face the Mets a third time through the order, he’ll be out and the Mets will be dealing with Kris Medlen or Danny Duffy in the middle innings.

Harry: Christina, you mentioned that Yost wouldn’t stick with Chris Young. The Mets bullpen is so weak that they had to bring in Jon Niese again in Game 2. And while it worked for one inning, it killed them in that second inning.

Carl: The starting-pitching matchups look good for the Mets on paper, and it does seem like the Mets bats are due to regress upward (progress?). So to what extent do we say the first two games were fluky, and to what extent do we reconsider our assessment of the two teams? Is

October 28, 2015

Yeah, Jeb Bush Is Probably Toast

“You know, I think Jeb Bush is toast,” I told one of my editors after Wednesday night’s debate.

“I kinda do too,” he replied. “I’m just worried because that’s what everyone else seems to think too.”

Yes, we pride ourselves on being skeptical of the conventional wisdom here at FiveThirtyEight. You don’t have to look very far back for examples of it being wrong, such as how it badly overestimated the degree of danger that Hillary Clinton’s campaign was in until a week or two ago. But being skeptical is not the same thing as being a contrarian. There are plenty of times when the conventional wisdom is right. This is probably one of those times.

Bush received poor reviews for his debate performance from political commentators of all stripes (Republican, Democratic, partisan, nonpartisan, reporters, “data journalists”), many of whom also suggested that his campaign might soon be over. The straw poll1 we conducted among FiveThirtyEight writers and editors agreed; Bush’s average grade was a C-, putting him at the bottom of the 10-candidate group.

CANDIDATEAVERAGE GRADEHIGH GRADELOW GRADEMarco RubioA-ACTed CruzB+ADChris ChristieBA-DCarly FiorinaB-A-DBen CarsonC+A-DJohn KasichCB-DMike HuckabeeCBDDonald TrumpCB+D-Rand PaulC-B-FJeb BushC-BFI agree with the group (I gave Bush a C-). Bush lost a probably ill-advised confrontation with Marco Rubio over Rubio’s absences from the Senate. Bush’s closing statement seemed stilted. He was the setup for a Chris Christie applause line about fantasy football. And for much of the debate, he was an afterthought, receiving the second-lowest amount of talk time among the candidates.

None of these things, taken alone or even together, would ordinarily be all that damaging. Bush didn’t make a catastrophic mistake — an “oops” moment. But the media consensus seemed to be that the debate was a potential make-or-break moment for Bush. Even if you were to charitably round up Bush’s performance to a C+ or B-, it probably wasn’t good enough.

Why does the conventional wisdom matter so much for Bush? Two reasons. First, because (as we pointed out before the debate) Bush’s “fundamentals” aren’t all that strong. He entered the debate with middling favorability ratings and polling at about 7 percent nationally. His endorsements have all but dried up: just two since Labor Day and none in the past three weeks, according to our endorsement tracker. His third-quarter fundraising totals were mediocre. This wasn’t a case like that of Hillary Clinton, who even at her worst moments was polling at 45 percent and had the overwhelming support of the Democratic establishment. Bush had a lot of work to do to gain the lead in the first place.

The other reason the conventional wisdom matters for Bush is because Bush is running a conventional campaign. It’s not as though he has all that much grassroots support: Only 3 percent of his fundraising has come from small donors. Instead, Bush needs the support of Republican elites — and favorable media coverage — to signify to reluctant Republican voters that he’s a viable nominee. And he needs their financial backing to win a potential war of attrition.

Instead, before the debate, major Bush donors were fretting openly to reporters (not just swiping at Bush anonymously) that his campaign was in a potential “death spiral.” Those concerns may grow larger and louder now, especially given that Rubio and (in my view at least) Christie had effective debates and are plausible replacements for Bush in the “establishment” lane of the GOP field.

Could Bush ride out the storm? Maybe. But his problem isn’t a mere lack of “momentum”; his candidacy has always been flawed. Instead of being the most electable conservative — the traditional profile of the Republican nominee — Bush has never looked all that electable or all that conservative.

And Republicans have a lot of alternatives. While Rubio has some problems too — his third-quarter fundraising was pretty abysmal, for instance — he fits the profile of the electable conservative. If Rubio were to falter, the Republican establishment would have a few backup options left, such as Christie or John Kasich (or in an emergency, even Mitt Romney). These candidates also have flaws, Christie especially, but they aren’t necessarily more severe than Bush’s.

In the insurgent lane, Ted Cruz, a candidate whose chances were already on the upswing, probably helped himself during the debate. It’s possible that Cruz’s gains will come at Donald Trump’s expense, although I personally thought Trump did fine2 and that if Cruz gains in the polls, it could come from Ben Carson or some other candidate instead.

But whether it’s Cruz or Trump or Carson ahead, the Republican establishment can’t wait that much longer to get its act together. And the most expedient way to do that may be to kick Bush to the curb.

Check out our live blog of Wednesday night’s Republican debate.

Maybe Republicans Really Are In Disarray

As many of you have probably noticed, we’re suspicious of overarching political “narratives” here at FiveThirtyEight. Oftentimes, they’re applied prematurely to explain short-term fluctuations in the polls that prove irrelevant in the end.1 And even when narratives avoid this problem, they tend to be ad hoc, introduced after the fact to describe results rather than predicting them in advance.

Which narratives deserve more credit? We’re inclined to give more attention to theories of the 2016 campaign that (in the manner of testable scientific hypotheses) were proposed before it began. And we give more credence to narratives that rely on evidence other than polls,2 since polls just aren’t very predictive of much at this stage of the campaign.

Here’s one narrative that passes these tests. You might or might not agree with it, but it deserves a hearing. I was reminded of it the other day when reading an interview with the political scientists Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein, who have written extensively about it. The theory is that Republicans are a broken, dysfunctional political party — that the GOP is in disarray, in other words.

This idea has a little bit of tenure, having been introduced by Mann and Ornstein several years ago. And it can conjure plenty of evidence other than polls. For instance:

The Republican speaker of the House, John Boehner, recently resigned under pressure from a dissident group of Republicans, the House Freedom Caucus.Under Republican leadership, the House entered into an unpopular government shutdown and only narrowly avoided a crisis over raising the debt ceiling.The 112th and 113th congresses were among the least productive ever as measured by the amount of legislation passed, with filibusters and other parliamentary tactics used frequently.Statistical measurements of voting in Congress like DW-Nominate find that Republicans are, on average, more conservative than at any point in the modern era. Democrats in Congress have also become more liberal, especially in the past few years, but the polarization is asymmetric (Republicans have moved to the right more than Democrats have moved to the left).Nonetheless, there are also high levels of disagreement among Republicans in Congress. Because Congress is highly partisan, Republicans may be largely united when voting against Democrats, but this conceals profound differences among Republicans about tactics, strategy and policy objectives.In 2010, 2012 and 2014, Republican incumbents such as House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Sen. Dick Lugar of Indiana were ousted in primary challenges. Meanwhile, “outsider” candidates such as Christine O’Donnell in Delaware and Ken Buck in Colorado won the Republican nomination in key open-seat Senate races, possibly costing the GOP several Senate seats.Although establishment-backed candidates eventually won, Republicans were relatively slow to settle on presidential nominees in 2008 and 2012 as compared with previous years. The 2012 campaign featured several surges for candidates like Herman Cain and Newt Gingrich who were openly opposed by the party establishment.Republicans are apparently having trouble choosing their 2016 nominee as well, not just as measured by the polls, but also according to other measures of support like fundraising and endorsements.That seems like a coherent story. But before you get too comfortable with it, consider the following rebuttals.

The Republican speaker of the House, John Boehner, recently resigned under pressure from a dissident group of Republicans, the House Freedom Caucus.

Boehner may have resigned his speakership, but he served for a reasonably long time and was reasonably effectual at the job. Furthermore, after all the drama, the new speaker will probably wind up being Paul Ryan — who has plenty of establishment backing and who got the Freedom Caucus to accede to several of his conditions.

Under Republican leadership, the House entered into an unpopular government shutdown and only narrowly avoided a crisis over raising the debt ceiling.

The government shutdown was short-lived and probably did not cause substantial long-term damage to the GOP. And while the fights over the debt ceiling may have been scary, it’s not clear how close we actually came to breaching it — tense negotiations often involve brinksmanship.

The 112th and 113th congresses were among the least productive ever as measured by the amount of legislation passed, with filibusters and other parliamentary tactics used frequently.

This could just as easily result from plain ol’ partisanship and divided government — Democrats were in charge of the White House and (until this year) the Senate.

Statistical measurements of voting in Congress like DW-Nominate find that Republicans in Congress are, on average, more conservative than at any point in the modern era.

This data doesn’t necessarily prove that Republicans are dysfunctional. Instead, it just suggests they’ve become more conservative. A party can be extremely conservative (or extremely liberal) but also highly organized.

There are high levels of disagreement among Republicans in Congress.

Perhaps, but these intramural debates may be largely irrelevant. The GOP does not have much ability to affect policy so long as Democrats control the White House, and their behavior might change were they to win the presidency again. Republicans were reasonably unified when they last had unilateral control of government under George W. Bush.

In 2010, 2012 and 2014, Republican incumbents such as House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Sen. Dick Lugar of Indiana were ousted in primary challenges. Meanwhile, “outsider” candidates like Christine O’Donnell and Ken Buck won the Republican nomination in key open-seat races, possibly costing the GOP several seats in the Senate.

Some incumbents lost — but the vast majority survived. And it’s hard to argue that the tea party was all that damaging to Republicans given that the GOP had historically great midterm results in both 2010 and 2014. Overall, Republicans are doing quite well electorally, with the obvious and important exception of the presidency.

Although establishment-backed candidates eventually won, Republicans were relatively slow to settle on presidential nominees in 2008 and 2012 as compared with previous years.

These elections seem par for the course: John McCain and Mitt Romney wrapped up their respective nominations by Super Tuesday or shortly thereafter, which is about average for past nomination races. Also, the “Party Decides” theory of presidential primaries favored by political scientists (we like it too) is mostly focused on the end result of the nomination process. It predicts that candidates must have some establishment backing to win their nominations in the end; it doesn’t have that much to say about the path they take to get there.

Republicans are apparently having trouble choosing their 2016 nominee as well.

Emphasis on “apparently”; it’s still early. Almost every nomination race seems dramatic in real time. Almost every time, people advance convincing-seeming arguments about how “this time is different” and how past rules should be thrown out. And yet, almost every time, a fairly conventional candidate wins the nomination in the end.

So then, the “Republicans in Disarray!” theory has been debunked? No, not really; I just wanted to present both sides of the case. (Welcome to FiveThirtyEight, the site where we argue against ourselves.) Grand theories of politics are hard to prove definitively given the paucity of actual election results (just one data point every two or four years, depending on how you’re counting). The “Republicans in Disarray!” argument is credible, and pretty convincing when applied to Congress. But it’s not dispositive. Even if you buy it, you also have to decide where the theory applies; what effect it has on presidential primaries (as opposed to congressional elections) or on election outcomes (as opposed to governance once a candidate is elected to office) is hard to say.

But there is one dynamic of the 2016 GOP presidential primary that lends credence to the “Republicans in Disarray!” case. Under the “Party Decides” theory, which presumes reasonably arrayed parties, the most important proxy for party support is endorsements. And so far, Republicans lawmakers aren’t endorsing much of anyone.

Take our endorsement tracker. It finds that Republican lawmakers are issuing endorsements at their slowest pace ever.3 We’re at a time in the campaign when the rate of endorsements ordinarily accelerates — but Jeb Bush, the putative leader in endorsements, has received just two since Labor Day. There have been just three endorsements for any Republican candidate in the past two weeks (all three were for Marco Rubio). Hillary Clinton has roughly twice as many endorsements as the entire GOP field put together.

It may be revealing to break the endorsement data down by the ideology of the endorsers, as measured by DW-Nominate. In the chart below, I’ve split the 301 current Republican members of Congress (both senators and representatives) into three groups: the most moderate 100 members, the most conservative 100 members, and the 101 in between.

Among the most moderate Republicans in Congress, it’s mostly business as usual. The pace of endorsements is sluggish (about two-thirds of these relatively moderate Republicans haven’t endorsed anyone yet) but largely in line with past elections, including 2012 and 2008. Jeb Bush is the clear front-runner with this group, with 16 percent of the endorsements from moderate Republicans in Congress; Chris Christie is in second place, with 5 percent.

A decade or two ago, the majority of Republicans in Congress would have fit into what we’re now calling the “moderate” group.4 But now, the center of gravity has shifted. And the 101 Republicans near the median of the party have had much more trouble reaching consensus. About 80 percent of them have yet to issue any endorsement. And no candidate (Bush and Rubio are nominally tied for first place) has received more than 5 percent of their support.

Look toward the most conservative 100 Republicans, and there are even more signs of disarray. As with the previous group, about 80 percent of them haven’t endorsed anyone yet. But among those who have endorsed, the leading choices are Ted Cruz and Rand Paul, two candidates who spend a lot of their time poking a finger in the eye of the Republican establishment.

Looking at these endorsements, the Republican Party appears to be disarrayed, or at least not as arrayed as it usually is. Most elected officials haven’t yet picked a candidate, and there’s substantial disagreement among those who have.

So then: President Trump? Well, probably not. Trump (and Ben Carson) has a lot of problems other than lack of support from the Republican establishment. And even if the Republican Party is too weak to easily reach consensus on a candidate, it may nevertheless be strong enough to veto an unacceptable nominee from being chosen. (Trump has little support even among the Freedom Caucus.)

But someone like Ted Cruz could be a more plausible nominee than under ordinary circumstances. And even if the establishment “wins” and gets its preferred nominee, that process might take longer than normal, possibly including a race that’s undecided after the final primary and caucus states vote in June.

Republicans have had a lot of close calls in recent years. Events such as the debt ceiling debate and the speakership transition looked like potential crises, but cooler heads prevailed in the end. Close calls, however, are usually a sign of being accident-prone. The risk of an “accident” is higher than usual.

Check out our live coverage of the Republican debate.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers