Nate Silver's Blog, page 143

January 25, 2016

Elections Podcast: One Week To Iowa

You can stream or download the full episode above. You can also find us by searching “fivethirtyeight” in your favorite podcast app, or subscribe using the RSS feed.

If you’re a fan of the podcast, leave us a rating and review on iTunes, which helps other people discover the show. Have a comment, want to suggest something for “good polling vs. bad polling” or want to ask a question? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

The Republican Party May Be Failing

“The Party Decides,” the 2008 book by the political scientists Marty Cohen, David Karol, Hans Noel and John Zaller, has probably been both the most-cited and the most-maligned book of this election cycle. After re-reading the book, which underpinned a lot of our early analysis of the primaries here at FiveThirtyEight, I’ve come to another conclusion: It’s probably also the most misunderstood book of the 2016 campaign.

The caricature of the book seems to be this: “The Party Decides” posits a clash between “the establishment” and rank-and-file voters and claims that the establishment always prevails. But that’s not really what the book says. Instead, the book argues that the major American political parties are broad and diverse coalitions of politicians, activists and interest groups, many of whom would never think of themselves as belonging to the political establishment.

However, the book does presume that, in part because of their breadth and diversity, American political parties are strong institutions. Furthermore, it assumes that strong, highly functional parties are able to make presidential nominations that further the party’s best interest.

For a variety of reasons, the nomination of Donald Trump would probably not be in the best interest of the Republican Party. Such an outcome this year, which seems increasingly likely, would either imply that the book’s hypothesis was wrong all along — or that the current Republican Party is weak and dysfunctional and perhaps in the midst of a realignment.1

The party isn’t “the establishment”You might associate “The Party Decides” with an empirical claim made in the book: Endorsements made by influential Republicans and Democrats are a good predictor of who will win each party’s nomination. At FiveThirtyEight, we’ve been keeping track of a subset of those endorsements, those made by current governors and members of Congress in each party.

Our focus on endorsements by governors and members of Congress is mostly a matter of convenience, however.2 In “The Party Decides,” the authors consider a much broader array of endorsers, including state legislators, labor unions, interest groups and even celebrities. This is important because, in contrast to earlier scholarship that thinks of parties as consisting solely of politicians and party organizations like the Republican National Committee, the authors of “The Party Decides” take a more inclusive view. Their parties include not just elected officials but also “religious organizations, civil rights groups … organizers, fundraisers, pollsters, and media specialists” and even “citizen activists who join the political fray as weekend warriors.”

That means the term “Republican establishment” (in addition to its other problems) is not a good approximation for the book’s view on the party. “Anti-establishment” members of Congress, such as the Freedom Caucus, are parts of “the party” as much as members who always vote with leadership. Lots of people within Washington, D.C., are considered to be part of the “party,” but so are people in Kentucky and Alaska. The editors of National Review magazine are probably3 part of the Republican Party as the book’s authors would define it, but so are bloggers at RedState and conservative talk-radio hosts in Iowa.

The authors of “The Party Decides” use phrases like “party elites” and “party insiders” to describe this collection of people. An alternative that I sometimes prefer is “influential Democrats” and “influential Republicans.” That’s really the bottom line: These people have some ability to influence the nomination,4 and they have some interest in doing so. That influence could take many forms, including holding a position of power, having access to a donor network, possessing scarce skills or knowledge, contributing time or money, or having the ability to persuade others through a media platform.

It might even be tempting to boil down “The Party Decides” to an idea like this: You ought to pay attention to what influential people who care about a party nomination are doing, since they can have a lot of say in the outcome. Indeed, that’s probably a better representation of “The Party Decides” than the idea that a monolithic establishment always wins.

But the book has something more than that in mind. Parties are not merely collections of influential people; those people are supposed to be working together to further the party’s interests. If they “can agree to work together for a candidate, as usually they can, they constitute a formidable political force,” the book says. But they cede much of that power when they remain splintered.

The mechanics of this are complicated, obviously. Some groups within a party care a great deal about winning office. Others are more interested in policy or ideological victories. Moreover, in a given election, a party can only nominate one candidate; if she wins office, she’ll have only so much political capital. Which issues get priority and which ones get short shrift?

But if the parties in “The Party Decides” are complicated, that’s because real American political parties are complicated, too. It’s not inherently obvious what anti-abortion activists, the National Rifle Association, the oil lobby and movement conservative intellectuals have in common — but all of them usually associate themselves with the Republican Party and they potentially stand to gain by working together under its banner.5 Historically, the result of this party-building process has been a punctuated equilibrium of parties that can be stable for decades at a time but which occasionally undergo rapid and dramatic realignments.

Strong parties nominate strong candidatesSo the party always wins? Not quite. Blame the book’s title if you like (the long version is: “The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform”). It seems to imply that the Republican and Democratic parties are all-powerful, with voters merely going along for the ride. That’s not quite what the authors say, however. “We do not claim that parties are juggernauts that always prevail,” they write in the first chapter.

The authors are also aware of the limited data available on party nominations. “The greatest point of vulnerability, in our view, lies in the thinness of the data that underlie the analysis,” they write. “Our main analyses involve sixty-one candidates, but these candidates ran in only ten nomination contests — and ten is not a large number for making inferences about a process as complicated as presidential nominations.”6 Being aware of these limitations is not the same thing as working around them, of course. But generally speaking, I think the book does a pretty good job under the conditions. (For geeky readers, I have a longer discussion in the footnotes.7)

One reason I say this is because the claims made by “The Party Decides” are modest. The authors aren’t saying that parties can wave a magic wand and nominate whomever they like. Instead, they posit that American political parties are robust and diverse institutions. And they claim that these parties make fairly rational choices in whom they nominate for president. The closest the book comes to a thesis statement is this:

Parties are a systematic force in presidential nominations and a major reason that all nominees since the 1970s have been credible and at least reasonably electable representatives of their partisan traditions.

There are a couple of things to unpack here. First, that qualification “since the 1970s.” That refers, in part, to the nomination process that’s been in place since the McGovern-Fraser reforms, which greatly increased voter participation in the system. However, it conveniently also excludes the Democratic nominations of 1972 and 1976, which were contested under the new system but resulted in the choice of factional candidates, George McGovern and Jimmy Carter.

The book’s view is that party elites had yet to learn the nuances of the new rules, whereas McGovern and Carter had clever strategies to exploit them. (In McGovern’s case, focusing on delegate accumulation instead of the popular vote; in Carter’s, understanding that a strong performance in Iowa could produce media-fueled momentum that would give him a leg up in subsequent contests.) Perhaps, but these years also suggest that the power wielded by party elites is fragile and that unconventional candidates can win if they (like Trump) pursue unconventional strategies.

Nonetheless, truly disastrous nominations like McGovern’s have been rare. Instead, parties have usually nominated candidates who, as the book puts it, are:

“Credible and at least reasonably electable”;“Representatives of their partisan traditions.”You might describe these two dimensions (as we sometimes have) as “electability” and “ideological fit.” The goal for a party is to find a candidate who scores highly along both axes. George W. Bush in 2000, for example, was acceptable to all major factions of the GOP, but he also began the race as a “compassionate conservative” with a highly favorable image among general election voters. It’s no surprise that Bush won his nomination easily.

At other times, the party must contemplate a trade-off between these goals. Sometimes, it will choose a candidate who breaks with party orthodoxy in important ways, but who has a lot of crossover appeal to general election voters. Bill Clinton in 1992 and John McCain in 2008 are good examples. Or, it may go for broke with an ideologically “pure” candidate whose electability is unproven. Sometimes, the gamble pays off, as it did for Republicans with Ronald Reagan in 1980, but there’s also the risk of winding up with the next Barry Goldwater. Note that Bernie Sanders and Ted Cruz, if chosen, would arguably8 fit into the category of ideologically pure but electorally dubious nominees.

http://c.espnradio.com/audio/2664556/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-01-25-174556.64k.mp3Our elections podcast launched this week. Listen to the full episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

It has been extremely rare, however, for a candidate to be nominated while scoring poorly along both dimensions. McGovern is probably the best example, insofar as he was too radical even for many Democrats in 1972 and a disaster of a general election nominee.

Donald Trump might be another of those cases. It’s not clear what policy positions Trump really holds, but to the extent he has articulated them, they’re all over the map and not that well aligned with those traditionally held by Republican officeholders. However, unlike previous “mavericks” such as Bill Clinton or McCain, Trump is not very popular with general election voters. On the contrary, he’s extremely unpopular with independents and would begin the general election race with worse favorability ratings than any candidate to receive a major-party nomination before.

To some extent — at least until we see how the first few states vote — this is a reason to be skeptical of Trump. It’s possible that even if party elites don’t have much say in the process, Republican voters will figure out on their own that Trump is a risky nominee.

Put another way, the case for being doubtful of Trump’s nomination prospects never had all that much to do with “The Party Decides.” It was not as though Trump fit the profile of a typical Republican nominee but just lacked endorsements from party elites. Instead, Trump is an outlier in nearly every respect and in ways that suggest he could be extremely damaging to the Republican Party as its nominee. To have doubted Trump is to have given the Republican Party credit, perhaps too much credit, for being able to avoid a potential disaster.

But now that Trump has gone from “black swan” to prospective nominee, it’s worth asking another question: If Republican voters are on the verge choosing Trump, why aren’t party elites doing much to stop them?

So why isn’t the GOP stopping Trump?Some of the reasons could be circumstantial. One way in which a factional candidate might win the nomination is by claiming the plurality when the vote among mainstream candidates is divided. That might be some of what’s happening this year. An unprecedented number of traditionally well-qualified Republicans entered the race. Although some of them have since dropped out, there’s still a pile-up in New Hampshire –– a state where Republicans might otherwise have a chance of stopping Trump — with Marco Rubio, Chris Christie, Jeb Bush and John Kasich each polling between 8 percent and 12 percent of the vote.

Another reason could be if a candidate rides a wave of media-driven momentum to victory. Usually, we’d think of a momentum candidate as someone like Carter, who parlayed an unexpected “win”9 in the Iowa caucuses in 1976 to emerge from obscurity and top a disorganized field. Can Trump, who was a nationally renowned figure before he entered the race, really be placed in the same category as Carter? Maybe. The media coverage of Trump has been disproportionate and seems to be self-reinforcing, with polls and coverage begetting one another in a virtuous cycle.

But these aren’t the good excuses for party elites that they might seem. In fact, they are exactly the sorts of outcomes that party elites are supposed to intervene to prevent. One of the reasons to coordinate during the early, “invisible primary” phase of the nomination is to avoid a logjam of candidates later on. As for Trump’s media coverage, surely some of it reflects the fact that he’s a perpetual attention machine who generates good ratings. But in “The Party Decides,” party elites are supposed to serve as a counterweight to “the poor quality of media coverage, which covers leading candidates much more than others.” So far, they haven’t been able to change the narrative on Trump.

What power does the party really have?

If the “Party Decides” theory is at a loss to explain why GOP elites have failed to stop Trump, it may be because elites never had all that much power to begin with. Indeed, the book can be frustratingly opaque when describing how party elites motivate rank-and-file voters to go along with their choices. “The inner workings of the invisible primary are, as the name implies, hard to see,” it says at one point.

So I’ll try to fill in the some of the blanks by borrowing from the political scientist Joseph Nye’s distinction between “hard power” and “soft power” in international relations. Hard power consists of military and economic might. Soft power consists of non-coercive forms of influence, such as gaining global esteem by exporting popular culture.

In the context of presidential nominations, the analogy to “hard power” is rule-setting authority plus control over scarce resources. Modern political parties do have some of this. They control the rules by which delegates are chosen, for example, though attempts to rig the rules in favor of the elites’ preferred candidate can backfire. They would have quite a bit of power in the (unlikely) event of a contested convention. Party elites also have access to financial resources, though not a monopoly on them.10 The party may own quite a bit of data, an increasingly important resource.

For the most part, however, “The Party Decides” seems to think that party elites possess “soft power”: the power of persuasion. It assumes that party elites have largely the same goals as rank-and-file voters, but are more informed about which candidates to support, leaving the electorate “open to suggestion”:

All of which leads us to reason as follows: An electorate that is usually not very interested, not very well informed, and attracted to candidates in significant part because they are doing well is probably an electorate open to suggestion about whom to support. If, as we know to be the case, many primary and caucus voters are also strong partisans, what they want in a candidate may be exactly what party insiders want: someone who can unite the party and win in November.

This is a plausible story in some respects. In particular, it coincides with the finding that polls are not very predictive until quite late in the nomination race and even then can undergo dramatic shifts in the span of weeks or days. Voters usually like several of their party’s candidates; it may not take all that much to nudge them from one candidate to another. There are also reasons to be skeptical, however. For example — perhaps especially in the Republican Party — there has been an erosion of trust between party elites and rank-and-file voters.

For a long time, this seemed to be the question that the Republican nomination would turn upon. Trump seemingly had plenty of support from voters, but almost none from party elites, making him the “perfect test case.” How much power did the party really have? Would voters continue to support Trump once the party threw its whole playbook at him?

But just when it looked like we were about to get some answers, a funny thing happened on the way to Des Moines.

Party elites haven’t been doing much to stop Trump

It became clear a month or so ago, if it hadn’t been already, that Republicans didn’t have much of a strategy for stopping Trump. In fact, other than occasionally tsk-tsking at some of his more inflammatory remarks, they weren’t doing much of anything about him. They weren’t waging a concerted negative campaign; there have been remarkably few negative ads of any kind against Trump. But party elites also weren’t throwing their support to any of the other candidates, at least judging by those candidates’ still-lackluster pace of endorsements.

Recently, the race took an even stranger turn. There were stories like this one, from Philip Rucker and Robert Costa at The Washington Post, suggesting that party elites were warming to Trump. Soon after, Bob Dole was suggesting that Trump wasn’t such a bad guy, while Iowa Sen. Chuck Grassley was appearing with Trump and urging voters to “make America great again.”

Importantly, these actions seem to have been taken mostly in opposition to Ted Cruz, instead of in support of Trump. Nonetheless, these reports caused me to renounce much of my remaining skepticism of Trump’s chances. Even tactical and tacit support for Trump is remarkable from the “Party Decides” perspective because the book suggests he’s just about the last person party elites would want to nominate.

I mentioned the main reasons for this before: Trump scores poorly on the two dimensions — electability and ideological fit — that party elites are supposed to care most about. Maybe you could make a devil’s advocate case on Trump’s behalf, but I’m not sure how convincing it would be.11

Moreover, Trump is not the sort of candidate to whom you’d expect the party to extend the benefit of the doubt. Under “The Party Decides,” parties are supposed to prefer candidates who are acceptable to as much of the coalition as possible to those who are polarizing. Trump generates considerable enthusiasm among some Republican groups but strong opposition among others. Party elites tend to prefer candidates who have worked their way up through the system and developed a network of relationships within the party. Trump, a relative newcomer to Republican Party politics, worked around the system instead.

What’s more, Trump has touched on any number of “third rail” issues, from banning Muslims from entering the United States to denouncing super PACs, that Republican candidates usually avoid. This is part of Trump’s appeal, of course: He says what other candidates won’t say, but which may nevertheless be popular with Republican voters. But Republican candidates usually avoid mentioning these topics for good reason12: They tend to expose the seams in the Republican coalition — splitting the base from the “donor class,” dividing some Republican constituencies from others, or damaging the party’s brand for the general election.

Perhaps you can argue that Cruz is just as bad as Trump from a “Party Decides” standpoint. Cruz is far enough to the right that he could cost the GOP points in the general election. He’s such a purist, in fact, that he also might be too far to the right for some groups of influential Republicans, such as those who support government subsidies for ethanol. Furthermore, Cruz is perceived to be difficult to work with. But there’s no reason party elites can’t oppose Cruz and oppose Trump just as vocally.

One explanation could be that party elites are misinformed or confused about Trump. “The Party Decides” tends to assume that party elites are highly sophisticated — able to see past the spin, the non-predictive early polls and the media talking points of the day. But perhaps this isn’t the case. Party elites often have relatively little communication with rank-and-file voters and may not understand the reasons for Trump’s popularity because they don’t encounter very many Trump supporters. At the same time, they exist within the political echo chamber and are inundated with constant media chatter about Trump’s polls and momentum. The party elites may even be engaged in a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts: Because everyone thinks that Trump is impervious to attack, no one is bothering to attack him.

Have Republicans lost their team spirit?

Maybe the most incredible passage of the campaign cycle comes from a recent Jonathan Martin article in The New York Times. It suggests that some Republican professionals are supporting Trump because they think he’ll lose:

Of course, this willingness to accommodate Mr. Trump is driven in part by the fact that few among the Republican professional class believe he would win a general election. In their minds, it would be better to effectively rent the party to Mr. Trump for four months this fall, through the general election, than risk turning it over to Mr. Cruz for at least four years, as either the president or the next-in-line leader for the 2020 nomination.

I’m a bit skeptical, but Martin seems to be referring to Republican lobbyists and consultants, in which case the reporting makes a certain amount of sense. If Trump wins the nomination but loses the general election, we’ll have another extremely vigorous competition for the Republican nomination in 2020, which means lots of work for consultants.13 Lobbyists and consultants would stay busy with either the transactional Hillary Clinton or the wheeler-dealer Trump as president, but less so with an ideologue like Cruz.

Other types of party elites have their own incentives. Republican members of Congress apparently think they’ll do worse with Cruz on the ballot than with Trump. I haven’t seen much evidence to support this claim (or much evidence against it), but so long as the members believe it, you might expect their self-preservation instincts to kick in.

The other Republican campaigns, meanwhile, may have tactical reasons to avoid attacking Trump even as they pillory one another.

The theme is that many Republican elites have no professional incentive to oppose Trump even if they personally dislike his politics or think he’d be a poor nominee. That’s fair enough. But the whole point of forming a party is to work together to facilitate the party’s interests. In that sense, the GOP would qualify as a weak, fraying party if it can’t avoid nominating Trump, a candidate who might at once reject large parts of the party’s traditional platform and potentially cost it a highly winnable general election.

That’s not to say the Republican Party would disappear after a Trump nomination — there would almost certainly still be something named the Republican Party — but it could conceivably be transformed into something more in Trump’s image, perhaps more in the direction of a European populist party. Trump’s nomination could even trigger a political realignment. Such things are rare, occurring perhaps once every several decades, but nominees like Trump are awfully rare, too.

Or maybe not. “The Party Decides” isn’t wrong, not quite yet. While most of the book’s focus is on the “invisible primary” phase of the campaign, it also presents statistical evidence that party elites continue to exert influence on the outcome well after Iowa and New Hampshire have voted.14 Furthermore, on the previous three occasions when party elites failed to reach a consensus before Iowa (these were the 1988 and 2004 Democratic nominations and the 2008 Republican race), the parties nevertheless wound up nominating fairly conventional candidates (Michael Dukakis, John Kerry and McCain). If Marco Rubio winds up the Republican nominee after all, the theory will come out looking pretty good. And if it’s Jeb Bush, somehow, the party’s powers will seem miraculous.

January 22, 2016

LeBron’s Cavs Are The Best Team Ever To Fire Its Coach Midseason

The Cleveland Cavaliers fired head coach David Blatt on Friday, even though he guided the team to the NBA Finals last season and a 30-11 record so far this year.

The NBA is a tough league. But as far as we can tell, no coach has been fired under similar circumstances before.

Below, you’ll find a table of NBA coaches since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976-77 who were fired or resigned in the middle of the regular season when their teams had an Elo rating of 1550 or higher.1 The league-average Elo rating is about 1500, so a rating of 1550 reflects a pretty good team; about as good as the Atlanta Hawks right now.

The most abrupt NBA coaching departuresCOACHSEASONTEAMELOCOACH RECORDNOTESDavid Blatt2015-16Cavaliers166930-11FiredDel Harris1998-99Lakers16116-6FiredLarry Brown1982-83Nets159947-26Resigned under pressureDon Nelson2004-05Mavericks159742-22ResignedLarry Brown1991-92Spurs158621-17FiredFrank Layden1988-89Jazz158411-6ResignedStan Van Gundy2005-06Heat158011-10Resigned under pressurePaul Westhead1981-82Lakers15727-4FiredDanny Ainge1999-2000Suns156313-7ResignedGene Shue1977-7876ers15592-4FiredJack McKinney1979-80Lakers155210-4InjuredSource: Basketball-reference.com

Coaches don’t usually get fired when their teams are playing well. But Blatt’s Cavs haven’t just been good; they’ve been on the verge of great. The team’s current Elo rating is 1669, far higher than that of any other team when it fired a coach mid-season.

When a coach does get fired despite a solid record, it’s usually because his team is underperforming lofty expectations. But that can’t really be said of the Cavs. Their preseason team win total at the Westgate Las Vegas SuperBook was 56.5 wins; they’re actually a little ahead of that pace, currently projecting to finish the season 61-21 instead.

Yes, the Cavs were embarrassed on Monday by the Warriors, 132-98. But one bad regular-season loss isn’t usually enough to doom a coach. It’s reasonable to ask whether the overt tension between Blatt and superstar LeBron James played a role because there’s not really a good precedent for something like this happening. (James was reportedly not consulted about Blatt’s firing.)

Larry Brown resigned under pressure as head coach of the New Jersey Nets late in the 1982-83 season despite a 47-26 record, but that was because he’d agreed to take a job the next season at the University of Kansas. Del Harris was canned as Lakers’ head coach early in the 1998-99 season when the team had a strong 1611 Elo rating, but its record was just 6-6 at that point, below the perennially high expectations in Lakerland.

January 21, 2016

One Big Reason To Be Less Skeptical Of Trump

In a nomination race like the Republican one, you could draw up a list of reasons to be skeptical of any candidate’s chances. Here are some reasons to be skeptical about Ted Cruz’s position in Iowa, for example. Here’s why Marco Rubio’s strategy looks increasingly precarious. There are also good reasons to be skeptical about Donald Trump’s chances of winning the Republican nomination:

His polling in Iowa isn’t great, and he’s probably still the underdog there.There’s reason to doubt the strength of his ground game, in Iowa and other states.Trump’s favorable ratings and second-choice numbers are generally inferior to Cruz’s and Rubio’s, meaning that other candidates might benefit more as the field winnows.1But the reason I’ve been especially skeptical about Trump for most of the election cycle isn’t listed above. Nor is it because I expected Trump to spontaneously combust in national polls. Instead, I was skeptical because I assumed that influential Republicans would do almost anything they could to prevent him from being nominated.

I’m in the midst of working on a long review of the book “The Party Decides,” so we’ll save some of the detail for that forthcoming article. But the textbook on Trump is that he’d be a failure along virtually every dimension that party elites normally consider when choosing a nominee: electability (Trump is extremely unpopular with general election voters); ideological reliability (like Sarah Palin, Trump’s a “maverick”); having traditional qualifications for the job; and so forth. Even if the GOP is mostly in disarray, my assumption was that it would muster whatever strength it had to try to stop Trump.

But so far, the party isn’t doing much to stop Trump. Instead, it’s making such an effort against Cruz. Consider:

The governor of Iowa, Terry Branstad, said he wanted Cruz defeated.Bob Dole warned of “cataclysmic” losses if Cruz was the nominee, and said Trump would fare better.Mitch McConnell and other Republicans senators have been decidedly unhelpful to Cruz when discussing his constitutional eligibility to be president.An anti-Cruz PAC has formed, with plans to run advertisements in Iowa. (By contrast, no PAC advertising has run against Trump so far in January.)You can find lots of other examples like these. It’s the type of coordinated, multifront action that seems right out of the “The Party Decides.” If, like me, you expected something like this to happen to Trump instead of Cruz, you have to revisit your assumptions. Thus, I’m now much less skeptical of Trump’s chances of becoming the nominee.

Can we take this a step farther, in fact? Can we say that the party has decided … for Trump?

I’ve seen some headlines to that effect, but they’re premature and possibly wrong. So far, the GOP’s actions are conspicuously anti-Cruz more than they are pro-Trump. For example, although former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin just endorsed Trump, no current Republican governors or members of Congress have.

Instead, it may be that Republicans think of Cruz as the more immediate threat, and then plan to turn around and attack Trump later. But that’s a high-degree-of-difficulty caper to pull off. For one thing, Trump, who’s in a much better position in the polls than Cruz in states after Iowa, could rack up several wins in a row if he takes the Hawkeye State.

Just as important, there are few signs that Republicans have much of a strategy for whom to back apart from Trump. Four “establishment lane” candidates — Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, John Kasich and Rubio — are tightly packed in New Hampshire polls. That could potentially change before New Hampshire votes because of tactical voting.2 And whichever of these candidates perform worst in the early states will probably drop out.

But Republican party elites seem indifferent among these four candidates, when in my view some are more capable than others of eventually defeating Trump and Cruz:

Rubio would seem to have the best shot. He’s easily the most conservative of the four, has the best favorability ratings and can make perhaps the best electability argument. His ground game may not be very good, but he has a decent amount of cash on hand.Bush and Christie probably rank next, in some order. It’s hard to imagine Republican voters coming all the way around to the patrician Bush after flirting with bad-boy Trump for so long — especially when Bush’s favorability numbers with Republican voters are in the tank. But remember that those dalliances with Trump are hypothetical, only contemplated in polls and not yet actuated with votes. Perhaps the Republican electorate that shows up to vote is more like the 2012 version, which supported Mitt Romney. It’s a long shot, but if it happens, Bush will have plenty of money and organization to extend the race.If the GOP electorate is in an angrier mood, then Christie’s personality overlaps the most with Trump’s. He’s a good debater, and his favorability ratings are on the upswing, although still just middling. But Christie entered the race with a lot of baggage that will receive more scrutiny if he surges in the polls. He also doesn’t have much of an organization beyond New Hampshire.Kasich’s outlook seems the worst of the four, combining Bush’s lack of appeal to conservatives with Christie’s lack of organization beyond New Hampshire. The one qualification to this is that Kasich has a more conservative track record than he lets on.3So if I were ranking the four establishment candidates’ chances of eventually defeating Trump and Cruz, I’d put Rubio first and Kasich last. But if I were ranking them in terms of who seems to have the most momentum right now, the order would be just the opposite. Kasich has gained 3 or 4 percentage points in New Hampshire polls over the past month, while Rubio has declined slightly in New Hampshire and national polls, and his once-steady flow of endorsements has turned into a trickle.

These differences might seem pretty minor — there’s room for near-daily momentum shifts before New Hampshire votes. Obviously, it’s also possible that Republicans’ efforts to stop Cruz in Iowa will backfire.

Things are lining up better for Trump than I would have imagined, however. It’s not his continued presence in the race that surprises me so much as the lack of a concerted effort to stop him.

Check out the latest polls and forecasts for the 2016 presidential primaries.

January 20, 2016

Is The Bernie Sanders Surge Real?

In this week’s 2016 Slack chat, the FiveThirtyEight politics team contemplates the “Bernie Bump.”1 As always, the transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Last week was a pretty good one for Bernie Sanders. Polls came out showing him closing in on Hillary Clinton in Iowa, and he continues to lead in New Hampshire. Weirdly, there wasn’t any obvious piece of news that would explain a Sanders surge. So, is it real?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): It seems pretty clear that he’s gained ground in Iowa. Less clear in national polls. Somewhere in between in New Hampshire.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Well, I’m not sure he’s gained ground in Iowa as much as Clinton has lost ground, according to the Des Moines Register poll. It is clear that the race is tighter in Iowa. Nationally, I do think Sanders has gained, but Clinton still holds a rather clear lead (15 to 20 percentage points). In New Hampshire, Sanders is ahead, but is it by 5 or 10 percentage points? I don’t know.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): I think that people started looking more seriously at Sanders in December, and I’m not really sure why. Maybe it was his campaign ramping up advertising in early states, being in the news more for the data breach (not that that was a good thing for Bernie, but he did try to spin it into “the DNC is trying to mute me”). Who knows! But he’s now being talked about as a serious candidate, where for a while he was sort of being treated more in the vein of a Dennis Kucinich.

natesilver: FWIW, our FiveThirtyEight national polling average (which we’re not publishing yet — stay tuned) has Clinton up 22 percentage points. Although that was before the Monmouth poll released today, which might tighten things a bit. But somewhere in the high teens or perhaps low 20s nationally is where the race seems to be. By contrast, our averaging method would have had Clinton up by 25 points at the end of December.

So that suggests some tightening, but not as much as the media narrative — which is pretty blatantly cherry-picking which polls it emphasizes — seems to imply.

micah: But this, at least in Iowa, doesn’t seem to be a case of “the media is making all this up.”

natesilver: Indeed — our Iowa polling average now has Clinton up by 5 points, compared with 16 points at the end of December.

harry: Well, the most recent NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found Clinton gaining over Sanders nationally.

micah: Does anyone have other explanations for the tightening in Iowa? Just more people tuning in? Change in tone of the media, as Clare said?

harry: How about the fact that Sanders has been outspending Clinton on television advertisements?

clare.malone: I think there’s probably a lot of that, and I also think there’s something to be said for the fact that people like Bernie’s idealistic version of the Democratic Party. But that’s also the luxury of being a voter in an early state, right? They feel like they can champion a guy who might not be mainstream but who can change the tenor of the race a bit. Whereas someone who’s voting in March might be more inclined to think of his vote in pragmatic terms — who’s going to actually win the general election?

natesilver: In Iowa, the demographics are pretty good for Sanders — as good as in New Hampshire, pretty much. He has a good ground game. People don’t have a lot of reason not to vote for him. The phrase “natural tightening” can be pretty meaningless, but I think it applies reasonably well here.

harry: Indeed, the favorable ratings for Clinton and Sanders are nearly identical in Iowa. Voters like both candidates. It’s doesn’t take a lot for them to shift between the candidates.

micah: And I think Clare’s right that the tone of the coverage of Sanders has shifted: People are taking him more seriously now.

clare.malone: The race getting tighter in Iowa has a lot to do with more people leaving the Clinton camp and saying that they’re undecided, so there’s still time for them to run back to her, but also just as much time for the Bernie momentum narrative to continue, which is helped along by … media like us! Slack chats changing the course of history, guys. This is big stuff.

harry: YUGE STUFF!

natesilver: Would you rather be the candidate (Sanders) whom the media ignores or the candidate (Clinton) whom the media interprets everything as being bad news for?

clare.malone: Ooh, primary election “would you rather.” This could be a MILLION-DOLLAR IDEA.

micah: The media doesn’t ignore Bernie.

clare.malone: I would always rather be the underdog, aka Bernie.

micah: I’d rather be Martin O’Malley.

clare.malone: Managing your expectations is key in politics, as in life.

natesilver: Our data suggests that Sanders is a little under-covered relative to his standing in the polls.

micah: That data is old.

clare.malone: SNAP!

harry: Micah throwing da shade.

micah: All right, so let’s posit that the tightening of the race in Iowa and (to a lesser extent) the nation is real and lasting. Sanders leads in New Hampshire. Is Sanders a real threat to win the nomination now?

natesilver: Define real.

clare.malone: I think that’s definitely going to change over the next week or so. The New York Times had a big piece this morning about how the Clinton campaign is changing its strategy given the Bernie bump (which, incidentally, sounds like a really fun dance move, no?).

harry: My New York accent is real. My ability to drive is also real, but not really real.

micah: Real means >25 percent chance.

natesilver: Sell.

micah: 20 percent.

harry: Sell.

natesilver: Still selling.

micah: [let’s give the #feeltheberners a moment to leave an angry comment]

15 percent.

natesilver: That’s about where Betfair has it, for what it’s worth.

harry: I’m sorry, but — knowing I’ve been paid off by my corporate overlords — here’s what I see: There’s just little-to-no sign that Clinton has lost any traction among black voters. The most recent YouGov poll has her up 75 percent to 18 percent among black Democrats. The most recent Morning Consult poll has her ahead 71 percent to 14 percent. The most recent Monmouth poll has her up 71 percent to 21 percent among non-white voters. Sanders would need to close that gap to have any chance in South Carolina. And remember, Clinton was only up by 7 percentage points at this point among non-white voters in the 2008 cycle.

natesilver: Indeed. That, along with her support from the party establishment, is why Clinton is the heavy favorite. But at what point does the price on Bernie become attractive to you?

If I could get him at 20-1 (implying about a 5 percent chance of winning), I’d take it.

harry: Yes. I think that’s fair.

clare.malone: This is a real down-at-the-betting-window Slack chat, isn’t it?

micah: Here’s the real question for me. For Sanders to win the nomination, he probably needs to win Iowa AND New Hampshire. And that’s eminently possible.

But if that happens, how much does that reset the race? You can imagine the media shitstorm that would follow, but is that shitstorm enough to hurt Clinton with non-white voters?

clare.malone: No, I don’t think so, Micah. Those are two pretty white states, right? I think Clinton would still be able to make her broad appeal, and, sure, she might have to do some big rebranding, maybe hitting heavier on a progressive economic message, playing up the whole thing about how Bernie is going to dismantle Obamacare, etc. — that to me, from the looks of the debate, is going to be one way that she hits him, gets the message across that he’s more “pie in the sky” idealist than “get it done” politician.

natesilver: Yeah, I think he needs both. Given its demographics and how much voter enthusiasm matters in a caucus, Iowa should be among the easier states in the country for him to win. If he can’t win in Iowa, I don’t think he’s competitive in enough places to make it a real race, although he could still win New Hampshire.

As far as forecasting the severity of the shitstorm, I’m of two minds. On the one hand, the media will absolutely eat up the story of the “inevitable” Clinton losing Iowa to a septuagenarian self-described socialist. On the other hand, Clinton’s media coverage is always something of a shitstorm. With a few exceptions, the Beltway consensus for months was that Joe Biden needed to jump into the race because Clinton was doomed. That proved to be profoundly flawed. And it depressed Clinton’s numbers in the polls, but not to the point where she ever trailed Sanders.

harry: Here’s what Sanders needs to do: Win caucuses out West (and polling out there suggests he could do so) and some Northern primaries. Then, he needs to combine that with doing better in the outer South (Kentucky, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia) than President Obama did. That’s the way this works. He won’t be able to recapture the Obama coalition in the Deep South.

micah: Are you all surprised that Sanders has gotten this close?

clare.malone: I don’t think it’s really all that surprising. I actually think, as crazy as it might sound, that Donald Trump and Sanders are trying to appeal to similar forces fomenting in the American population; people are frustrated with the way things are going, they are skeptical of big institutions (banks!), and they want to see a different kind of leadership. Of course, Trump’s way of courting this is instilling fear in people, and Sanders’s way of courting this is righteous, idealistic governmental revolution. They’re both populist movements, albeit with undertones of authoritarianism in one.

natesilver: I don’t think it’s that surprising. First, as we’ve been saying for six months now, the first two states happen to be pretty favorable for Bernie.

Second, there are a lot of people, including the media and Democratic interest groups, who have a strong incentive for there to be a competitive Democratic race, or at least some semblance of one. To get a little more wonky still, the median voter theorem would imply that two-candidate races should be at least reasonably close.

Third, history suggests that even “inevitable” candidates, like Bob Dole ’96 and George W. Bush ’00, lose a few states. Al Gore ’00 was the only one to sweep all 50. But he nearly lost New Hampshire to Bill Bradley. And if you’d read the press coverage of that race 16 years ago, you’d see plenty of articles about how Bradley was surging and it was time for Gore to panic.

harry: Sure, and both Dole and Bush used South Carolina as a firewall, just as Clinton might.

natesilver: Maybe this is all coming out as more skeptical about Bernie than I’m intending it to be. The case for Bernie is that (i) he could win Iowa and New Hampshire, which (ii) could produce huge momentum and very favorable press coverage, and (iii) he has enough money and a good enough ground game to run a long campaign, and (iv) well then, who knows, maybe this time really is different?

How do you translate that into a probability? That’s difficult. There’s a reason we’re trying to model the primaries one state at a time, instead of issuing an overall forecast.

harry: We won’t know if Bernie is for real until he wins Iowa. If he does, then let’s see where his support with non-white voters goes. Until then, it’s a lot of hypotheticals. And I’ve found that this season, hypotheticals have a weird way of playing out.

Check out the latest polls and forecasts for the 2016 presidential primaries.

January 18, 2016

Donald Trump Is Really Unpopular With General Election Voters

Several recent stories, like this one from the Washington Post’s Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, report that influential Republicans have become increasingly resigned to the prospect of Donald Trump as their nominee. One theme in these stories is that the GOP “donor class” seems to have persuaded itself that Trump might not be such a bad general election candidate.

On that point, the donor class is probably wrong.

It’s hard to say exactly how well (or poorly) Trump might fare as the Republican nominee. Partisanship is strong enough in the U.S. that even some of his most ardent detractors in the GOP would come around to support him were he the Republican candidate. Trump has some cunning political instincts, and might not hesitate to shift back to the center if he won the GOP nomination. A recession or a terror attack later this year could work in his favor.

But Trump would start at a disadvantage: Most Americans just really don’t like the guy.

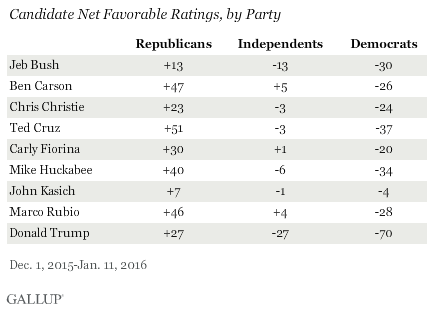

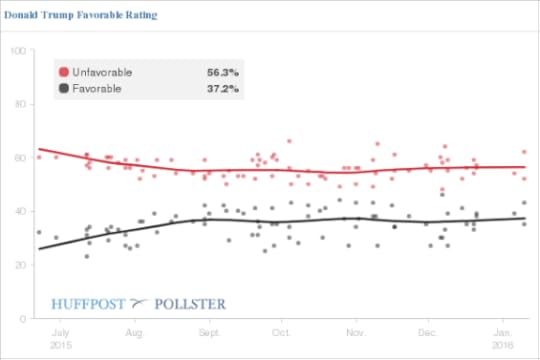

Contra Rupert Murdoch’s assertion about Trump having crossover appeal, Trump is extraordinarily unpopular with independent voters and Democrats. Gallup polling conducted over the past six weeks found Trump with a -27-percentage-point net favorability rating among independent voters, and a -70-point net rating among Democrats; both marks are easily the worst in the GOP field. (Trump also has less-than-spectacular favorable ratings among his fellow Republicans.)

Favorability ratings can vary quite a bit from pollster to pollster, however, so I went back and collected a broader array of data. Specifically, I took an average of each candidate’s favorability ratings in polls from the Huffington Post Pollster database since Nov. 1.1

Republican favorability, average since Nov. 1CANDIDATEFAVORABLEUNFAVORABLENET FAVORABLEBen Carson37370Marco Rubio3435-1Ted Cruz3239-7John Kasich2027-7Carly Fiorina2836-8Mike Huckabee2840-12Chris Christie3144-13Rand Paul2642-16Rick Santorum2244-22Jeb Bush2951-22Donald Trump3358-25Source: Huffington Post Pollster

We’ve got an unpopular set of presidential candidates this year– Bernie Sanders is the only candidate in either party with a net-positive favorability rating — but Trump is the most unpopular of all. His favorability rating is 33 percent, as compared with an unfavorable rating of 58 percent, for a net rating of -25 percentage points. By comparison Hillary Clinton, whose favorability ratings are notoriously poor, has a 42 percent favorable rating against a 50 percent unfavorable rating, for a net of -8 points. Those are bad numbers, but nowhere near as bad as Trump’s.

Democratic favorability, average since Nov. 1CANDIDATEFAVORABLEUNFAVORABLENET FAVORABLEBernie Sanders3835+3Hillary Clinton4250-8Martin O’Malley1829-11Source: Huffington Post Pollster

This is not just a recent phenomenon; Trump’s favorability ratings have been consistently poor. It’s true that his favorability numbers improved quite a bit among Republicans once he began running for president. But those gains were almost exactly offset by declines among independents and Democrats. In fact, his overall favorability ratings have been just about unchanged since he began running for president in June:

Head-to-head polls of hypothetical general election matchups have almost no predictive power at this stage of the campaign, but for what it’s worth, Trump tends to fare relatively poorly in those too. On average,2 in polls since Nov. 1, Trump trails Clinton by 5 percentage points, while Clinton and Marco Rubio are tied.

You could plausibly argue that Ted Cruz would be a worse nominee than Trump despite having better favorability ratings and faring slightly better in general election head-to-heads.3 There’s reasonably clear evidence that voters tend to punish candidates with “extreme” (far right or far left) ideologies, and by statistical measures Cruz would be the most conservative nominee since (and possibly including) Barry Goldwater in 1964. Trump’s ideology is harder to pin down.

But that Cruz might be a bad nominee doesn’t make Trump a good one. It’s a perplexing that Republican elites have resigned to nominating either Trump or Cruz when nine other candidates are running and no one has voted yet.

January 15, 2016

Why Some GOP Candidates Aren’t Taking The Fight To Trump

If you, like us here at FiveThirtyEight, were initially skeptical of Donald Trump’s chances of winning the GOP nomination in part because you assumed that the Republican Party would go out of its way to stop him, then you’ll find the following pretty remarkable. According to Tim Alberta of the National Review, there are currently no negative television ads running against Trump in Iowa, New Hampshire or South Carolina.

There are a lot of reasons for this — including, paradoxically, both resignation to the idea of Trump as the nominee, and conversely, a belief that Trump’s support in national polls won’t translate into winning margins in Iowa and other early voting states. But there’s another dimension to the problem too. It should have been perfectly obvious, but it became clearer to me after spending the past week in Iowa: The campaigns competing against Trump are acting in their own narrow best interests, and not necessarily in the best interest of the Republican Party.

If you look at the race through the lens of the national media, it’s easy to focus solely on Trump, and to a lesser extent Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio. But in Iowa, there are a lot of other Republican campaigns too. Some, like Ben Carson’s, are relatively visible in the form of billboards and advertisements. Others, like Rick Santorum’s, you really have to go looking for. All of these campaigns still have boots on the ground. However implausible their candidate’s chances might be, it’s the job of their staffers to keep working for their candidate until the bitter end.

So unless the Republican National Committee itself were to buy airtime to run negative ads against Trump, the question is which individual candidates might benefit from doing so. This answer is more complicated than you might think.

The most important part of the calculation is that if Trump doesn’t win Iowa, Cruz very probably will instead. In fact, if Trump slumps during the final two weeks of the campaign, Cruz could win resoundingly in Iowa, since polls suggest that he’s the second choice of many Trump voters.

So what would the other candidates rather have: an overwhelming Cruz win in Iowa or a close finish between Cruz and Trump?

Rubio, for example, might prefer a close finish. For one thing, if Cruz and Trump almost evenly split their vote, there’s an outside chance that Rubio could win Iowa himself with something like the 25 percent of the vote Mitt Romney got in 2012.1 Furthermore, a big Cruz win in Iowa, coupled with a big Trump loss, might be enough for Cruz to surge to the top of New Hampshire polls and win there too.

What about Chris Christie? Christie’s tough-guy persona might seem perfect for taking on Trump, especially during a debate. But Christie, like Rubio, has largely avoided confronting Trump. That too could reflect a strategic calculation. To win the nomination, Christie will first need a good performance in New Hampshire. Then he’ll hope to survive until the latter half of the nomination process, when lots of delegate-rich (and often winner-take-all or winner-take-most) blue and purple states vote. He’s playing a long game, in other words, and he might not mind some Trump-induced chaos in the short run if it prevents Cruz or some other candidate from slingshotting to victory.

Obviously, the calculations that Rubio and Christie are making may be wrong. Jeb Bush and John Kasich, whose situations are not all that different than Christie’s or Rubio’s, have chosen to attack Trump instead. Furthermore, the more Trump becomes a threat to win the nomination himself, instead of being a bumper that other candidates try to ricochet against, the more urgent it becomes to attack him.

That may be what Cruz’s campaign has figured out. After months of buddying up to Trump, Cruz is now shifting into attack mode. While Cruz might prefer a cordial victory over Trump in Iowa, maintaining a favorable image with Trump supporters so as to convert them into his camp later on, Trump remains too much of a threat too late in the race for Cruz to feel assured of that now.

It might seem ironic that the establishment could soon be counting on Cruz to save itself from Trump. (Cue the scene from “Jurassic World” when T. Rex is summoned out of its cage to battle Indominus Rex to the death.) But if you consider the problem from the standpoint of the individual campaigns, and not “the party” as a whole, it makes a lot more sense.

January 14, 2016

The GOP Primary, In One Debate

If you’d spent the past eight months hiking the Appalachian Trail, and Thursday night’s GOP presidential debate was the first whiff you’d gotten of the candidates in action, you’d be more than a little surprised to see Donald Trump at center stage, where the polling frontrunner normally stands. And maybe you’d be wondering where Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker went. But by the end of the nearly two-and-a-half hour debate, you’d have a reasonably good understanding of the dynamics of the Republican race.

You’d see, in Trump, a lot of political “street smarts.” You’d see a willingness to draw from a populist grabbag of topics (tariffs on China; a ban on Muslims entering the United States) that candidates from both parties usually avoid. You’d also see plenty of self-indulgence on process topics such as Ted Cruz’s “natural born” citizenship, and a willingness to pontificate on topics he clearly knows nothing about. You’d notice that several of Trump’s opponents seemed too intimidated to attack him. You’d see Trump wobble — sometimes badly, such as in his initial exchange with Cruz — and then recover, almost miraculously.

You’d see, in Cruz, a smart tactician who serves up plenty of red meat, and who (perhaps more effectively than any other candidate) plays to both the debate hall and the home viewing audience. You’d also see a candidate who doesn’t invite sympathy and can overextend himself, sometimes tempting an effective counter-attack, like the one Trump got in about “New York values” and Sept. 11.

You’d see, in Marco Rubio, the ultimate glass-half-full, glass-half-empty candidate. Just when you thought Rubio was finally going to have his breakthrough moment (his opening answer was effective and flashed anger that Rubio has sometimes been lacking), he’d disappear for long stretches of time, with competent but canned-sounding answers that failed to raise him above the fray. Then just about when you were ready to count Rubio out, he’d surprise you with an effective strike, like the one he carried out against Cruz on immigration and other topics toward the end of the debate.

You’d see, in Chris Christie, a candidate who seemed to be on the fringe between top-tier and second tier. You’d notice that he was using his personality to mostly good effect (this wouldn’t have been true if you’d watched some of Christie’s earlier debates). You’d see that, like Cruz, he was a good tactician. But you’d also wonder if his blows were landing as effectively with the home audience of conservative Republicans as they were on stage.

You’d see Jeb Bush, and wonder why a candidate who was once one of the frontrunners was standing over yonder in 4-percenter territory. Then you’d witness Bush’s seeming inability to read the moment. He’d invite a fight with Trump over Trump’s proposed Muslim ban — a slightly risky tactic given where Republican voters poll on the issue, but perhaps worthwhile if Bush wants to appear dignified and presidential — only to be oddly ineffective in delivering his punch, bogging himself down in process instead of principles.

You’d see John Kasich and wonder if his goal was to win New Hampshire, or maybe just to get liberal pundits to say nice things about him on Twitter.

You’d see Ben Carson and wonder if he had a pulse.

All right, you get the point. But I noticed that in the grades we collected from the FiveThirtyEight staff tonight1, there was a strong correlation between how much success we thought the candidates had in the debate Thursday night and how well they’re doing in the nomination race overall.

CANDIDATEAVERAGE GRADEHIGH GRADELOW GRADETed CruzB+AC+Donald TrumpBA-C-Chris ChristieBB+C+Marco RubioB-B+CJeb BushC+BDJohn KasichCBDBen CarsonD+CFNot a perfect correlation — we had Cruz having the slightly better debate than Trump, when Trump remains ahead of him in polls. But the debate was still the closest thing we’ve seen to the GOP campaign in microcosm.

January 13, 2016

The Glass-Half-Empty Case Against Ted Cruz

DES MOINES — Like so much else at this point in the campaign, Wednesday morning’s Des Moines Register/Bloomberg Politics Iowa poll could be looked at in either of two ways for the leading candidates. For Ted Cruz, the glass-half-full interpretation is that the best poll in the state still shows him ahead — by 3 points over Donald Trump — when several other recent polls in Iowa had shown a narrow advantage for Trump instead. The glass-half-empty interpretation is that Cruz’s lead is diminished: The previous DMR/Bloomberg poll, taken a month ago, had Cruz ahead by 10 points.

Our Iowa Republican forecast model splits the difference between these two hypotheses, with Cruz’s position essentially unchanged from where it was before the new poll.

And yet, in the conventional wisdom about who’s going to win Iowa, there’s a lot of glass-half-fullism for Cruz. The prediction market Betfair puts his chances of a win at 65 percent. By contrast, the polls-plus version of our forecast, which accounts for endorsements and the candidate’s standing in national polls in addition to state polls, puts Cruz’s chances at 50 percent (as compared to 26 percent for Trump and 17 percent for Marco Rubio). The polls-only version of our forecast puts Cruz’s chances at 42 percent, essentially tied with Trump.

Our forecast models are blunt instruments in the primaries. They’re not directly accounting for Cruz’s apparently superior Iowa ground game or the fact that he has a lot of support among evangelical voters. Cruz also has among the top favorability ratings in the state and is a lot of voters’ second-choice candidate, putting him in a good position to pick up support should supporters of other candidates waver. That’s the glass-half-full case, and it’s a perfectly reasonable one.

What about the glass-half-empty case?

Cruz may not be leading at all depending on what poll you look at; several of them have Trump ahead instead.It’s still awfully early in Iowa. There are almost three weeks of campaigning left to go — and unlike in 2012 or 2008, the stretch run won’t be interrupted by the holidays. That’s an eternity in a race where about half of voters say they’ve yet to make up their minds.Iowa isn’t necessarily a two-horse race. Rubio, sitting in the low- to mid-teens in the polls, is in no worse a position than John Kerry was before winning the 2004 Democratic caucuses, or than Rick Santorum was before winning the Republican race here in 2012.Cruz’s campaign has tended to raise the media’s expectations for how he’ll perform in Iowa. That can be a high-risk, high-reward strategy, reinforcing momentum when things are going well, but potentially triggering “Did Cruz peak too soon?” storylines if he has a rough debate or a bad few days in the polls.I’m not sure which case I find more persuasive. I agree with the notion that Cruz is the favorite in Iowa, but just how much of a favorite is harder to say.

Check out our 2016 primary forecast and follow along as FiveThirtyEight’s politics team reports from Iowa all week.

January 12, 2016

Who’s Winning Iowa And New Hampshire?

We launched our forecasts for the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primaries today. For much more detail about how this all works, you can read here. But our premise is that, given the challenges inherent in predicting the primaries, we’ll be publishing two models instead of pretending we’ve found a magic bullet:

The first model, which we call polls-only, is based only on polls from one particular state. (Iowa polls in the case of Iowa, for example.) It’s basically an updated version of the model we used for the primaries four years ago.The second model, polls-plus, also considers endorsements and national polls, in addition to state polls, and tries to consider the effect that Iowa and New Hampshire could have on subsequent state contests. (National polls aren’t necessarily a positive for a candidate in the polls-plus model; instead, it’s a bearish indicator when a candidate’s state polls trail his national numbers.)Historically, polls-plus would have been somewhat more accurate, but it’s pretty close — so we think the models are most useful when looked at together. Indeed, they present different perspectives on the races this year, mostly because of that endorsements variable, which helps Hillary Clinton and Marco Rubio but hurts Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. If you take a strictly empirical view of the primaries, accounting for the establishment’s historical tendency to win out in the end, you’ll probably prefer the polls-plus model. If you think “this time is different” — or you’re a Trump or a Bernie fan — you’ll probably like polls-only instead.

Let’s go through the four races we’re forecasting so far:

Iowa Republicans. Before the new year, Ted Cruz appeared to have a narrow polling lead over Trump, but that’s less clear now, with several recent polls showing a small advantage for Trump instead. In fact, the polls-only forecast now has the race as a dead heat, giving both Trump and Cruz a 42 percent chance of winning Iowa.

Cruz retains an edge in the polls-plus forecast, however; it likes him because his Iowa polls exceed his national polls (while the opposite is true for Trump). Polls-plus gives Cruz a 49 percent chance of winning Iowa, to Trump’s 28 percent.

What about an upset in Iowa? Given how volatile the polls can be there, it’s too soon to completely write off third-placed Rubio. He has an 18 percent chance of winning Iowa according to polls-plus and a 9 percent chance based on polls-only. Other candidates, however — including Ben Carson, who is sinking so much that he’s at risk of dropping out, according to the model — are true long shots.

Iowa Democrats. Because public opinion can shift rapidly in the primaries, our models put a lot of emphasis on the most recent polls. That’s good news for Sanders, who has been neck and neck with Clinton in Iowa polls published this month after trailing her for most of last year. In fact, the race is nearly a tossup: He now has a 45 percent chance of winning Iowa according to polls-only, although the polls-plus model, noting Clinton’s dominance in endorsements, is more skeptical of Sanders, giving him a 27 percent chance instead.

New Hampshire Republicans. Of the four races we’re forecasting right now, this one is probably the most interesting, even though it also features the clearest leader: Trump, who has led almost every New Hampshire poll since July.

Let’s start with the good news for Trump. Not only is he leading — he’s also gained a bit in the latest New Hampshire polls, polling at about 30 percent recently, compared with 26 percent in December.

Nonetheless, it’s early in New Hampshire, and there are five other candidates besides Trump who have at least a semi-credible path to victory there. Thus, recognizing the uncertainty in the race, the polls-only model has Trump with a 55 percent chance to win the state: pretty good, but still barely better than a coin flip.

The polls-plus model also has Trump as the front-runner but puts his chances lower, at 39 percent, in part because it gives decent odds to a number of candidates from the moderate and establishment parts of the GOP. Collectively, Rubio, John Kasich, Chris Christie and Jeb Bush have a 47 percent chance of winning New Hampshire. Among that group, Rubio has the best chance (23 percent), while Kasich’s fortunes (11 percent) have been rising. Bush’s chances are just 6 percent, on the other hand, and have continued to fall.

It’s also conceivable that Cruz could win New Hampshire, especially after a big win in Iowa.

New Hampshire Democrats. Here, there’s a split between the models. Sanders is a 73 percent favorite according to polls-only, while polls-plus — noting Clinton’s advantage in endorsements and that she’s favored in Iowa — gives Clinton the slightest edge, with a 53 percent chance to Sanders’s 47 percent. Essentially, she’d be following the path that Al Gore took over Bill Bradley in 2000, when an Iowa victory propelled him to a narrow victory in the Granite State. But the polls-plus model is designed to lower the effect of the endorsements variable to zero by election day in each state. So if Clinton keeps falling in New Hampshire and Iowa polls instead of rising, the establishment may not be able to bail her out, and she’ll have to contemplate the possibility of being swept in both states.

Forecasts will be coming soon in other states like South Carolina once more polling becomes available in them.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers