Nate Silver's Blog, page 142

February 1, 2016

Iowa Is The Hardest State To Poll

It’s common for pundits to recite ass-covering phrases like “it all comes down to turnout” or “anything could happen” on the eve of a big election. If you’ve been following FiveThirtyEight over the years, you know it’s not our style to do that. Instead, we issue probabilistic forecasts, which can sometimes seem quite confident: We had Barack Obama as a 90.9 percent favorite to beat Mitt Romney on the eve of the 2012 general election, for example.

So let’s get a couple of things straight before the results start trickling in from Iowa tonight:

It all comes down to turnout.Anything could happen.All right, not absolutely anything could happen. Martin O’Malley is not going to win the Democratic caucuses. Donald Trump will probably not finish behind Carly Fiorina.

But could Marco Rubio win the Iowa caucuses despite not having led a single poll there? Sure. Rick Santorum did that exact thing four years ago.

Could Trump slip all the way to third place? Entirely plausible. But he could also get upwards of 40 percent of the vote and double his nearest rival’s total.

Ben Carson in second place? Rand Paul in third? The odds are against it — but equally strange things have happened in Iowa before.

We say this for the same reason we can sometimes issue highly confident forecasts just before a general election: It’s what the data tells us. That data tells us that polling in general elections is pretty accurate, at least in the final few weeks before the election. The data also tells us that polling in primaries and caucuses is not very accurate. Historically, the average error of late polls in presidential general elections is about 3.5 percentage points.1 By contrast, the average polling error associated with presidential primaries is more like 8 percentage points, more than twice as high.

So imagine that we have a forecast showing Trump 4 percentage points ahead of Ted Cruz in some state. If Trump wins by 12 points instead, or Cruz wins by 4, the pollsters would be pilloried, and we’d come in for our share of flak too. But that’s what an 8-point error looks like, and 8-point errors happen fairly often in primaries and caucuses.

What makes polling these elections so difficult? There are a few major factors:

Turnout is much lower in primaries and caucuses, and much harder to predict.There are often multiple candidates running. Such races increase polling error because of the potential for tactical voting.There are far more swing voters because most voters like several of their party’s candidates. In the recent Des Moines Register Iowa poll, for example, the average Republican respondent had a favorable impression of four of the Republican candidates. By contrast, only a small fraction of general election voters like both the Democratic and Republican candidates.A substantial number of voters wait until the last few days of the campaign to make up their minds in primaries and caucuses; by contrast, the vast majority of general election voters have their minds made up well ahead of Election Day.But if primaries and caucuses are always tough for pollsters, some are even harder than others. This is something we’ve studied extensively too. Historically, the polling error has been higher when:

A state holds a caucus instead of a primary.It’s early in the nomination calendar rather than later. (Perhaps because pollsters haven’t yet had a chance to learn from their mistakes.)There are more candidates running. (See above for why this matters.)You’ll note that the first two circumstances apply in the Democratic caucuses tonight, and all three do for Republicans. Iowa is a caucus state, and it’s the first state to vote. And there are still a huge number of candidates on the GOP side. In our polling average, candidates other than Trump, Cruz and Rubio have a collective 28 percent of the vote, while another 3 percent or 4 percent of voters still say they’re undecided. That’s almost a third of the vote that could easily enough recirculate to one of the front-runners.

Put another way, the uncertainty associated with forecasting tonight’s Iowa Republican caucus is about as high as it gets in a major American election. Even Ann Selzer, the best pollster in the country, could have a rough night.

That doesn’t mean we’re completely in the dark. Our forecast models are designed to account for this uncertainty. Hillary Clinton, for example, leads Bernie Sanders by 4.5 percentage points in our Iowa polling average. In a general election, that would make her a rather heavy favorite, probably upwards of 90 percent. But in the Iowa caucuses, it’s not that much of an edge. Thus, our polls-only forecast still gives Sanders a 28 percent chance of winning, and our polls-plus forecast, which likes Sanders because his Iowa numbers exceed his standing in national polls, puts his chances slightly higher, at 33 percent.

There’s even more uncertainty on the Republican side. Trump leads Cruz in our polling average by about the same margin that Clinton leads Sanders, 4.7 percentage points. But the larger number of candidates involved could make for a wild finish. Here’s each candidate’s chances of finishing in first, second or third, according to our polls-only model:

Iowa: Polls-only forecast as of Monday afternoonCANDIDATE1ST2ND3RD4TH OR WORSEDonald Trump54%30%12%3%Ted Cruz3339208Marco Rubio11244024Ben Carson151579Rand Paul495Jeb Bush396Mike Huckabee298Chris Christie199John Kasich199Carly Fiorina99Rick Santorum>99Trump has a 54 percent chance to win, according to our polls-only model, compared with Cruz’s 33 percent. But you’ll notice that the model gives Rubio an outside chance too, 11 percent. Surely Rubio will finish in the top three, at least? No, that’s not certain either; the model gives him a 24 percent chance of finishing in fourth place or worse.

Then there are some of the truly wild scenarios I described earlier. Carson is given a 5 percent chance of finishing in second place. How might that happen? I can’t tell you. But by definition, the biggest surprises are the ones no one is prepared for, like Hillary Clinton beating Barack Obama in the 2008 New Hampshire primary.

Our polls-plus forecast also has Trump favored, but only narrowly. Its algorithm gives an extra percentage point or two to Cruz and Rubio because their Iowa polls exceed their standing in national polls — historically a favorable indicator — and the opposite is true for Trump.

Iowa: Polls-plus forecast as of Monday afternoonCANDIDATE1ST2ND3RD4TH OR WORSEDonald Trump46%33%17%4%Ted Cruz3937195Marco Rubio14264218Ben Carson31383Rand Paul396Jeb Bush298Mike Huckabee198Chris Christie>99John Kasich>99Carly Fiorina>99Rick Santorum>99But again, there’s a lot of uncertainty. Polls-plus assigns Trump a 10 percent chance of finishing with 15 percent of the vote or less, which could be a campaign-ending embarrassment. However, it also gives him a 10 percent chance of finishing at 38 percent or higher, in which case he’d look unstoppable.

As primary season wears on, our models won’t be hedging their bets quite so much. Candidates will drop out, and voter preferences may become more stable. As we learn more about who is voting for whom, we may also be able to add demographic information to our forecasts, which can potentially make them quite a bit more accurate.

But for tonight? Keep an open mind about the results. And don’t be shocked if the polls are way off.

http://c.espnradio.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2669580/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-02-01-153020.64k.mp3Our elections podcast just launched. Listen to the latest episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

Elections Podcast: Your Guide To The Iowa Caucuses

It’s Iowa caucuses day! In our elections podcast we break down the latest polling and news from Iowa, explain how caucusing works, and answer some listener mail.

http://c.espnradio.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2669580/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-02-01-153020.64k.mp3Subscribe: iTunes |Download |RSS |VideoYou can stream or download the full episode above. You can also find us by searching “fivethirtyeight” in your favorite podcast app, or subscribe using the RSS feed. Check out all our other shows.

If you’re a fan of the elections podcast, leave us a rating and review on iTunes, which helps other people discover the show. Have a comment, want to suggest something for “good polling vs. bad polling” or want to ask a question? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Why Iowa Matters For Trump And Sanders

If there’s one thing almost every species of political journalist agrees upon — number-crunchy nerds and shoe-leather reporters have no real beef about this — it’s that Iowa matters. Iowa matters a lot. (New Hampshire matters too. Those other states? Meh, not so much.2)

But for such a widely shared assumption, there’s not a lot of discussion about why Iowa matters. It isn’t self-evident why the votes of a couple of hundred thousand people in a kooky caucus process in a demographically unrepresentative state should tell us all that much about what will happen in the rest of the country. So what follows is an inventory of theories as to why Iowa can matter and whether there’s any basis to think it might be more or less important than usual this year. In particular, we’ll consider the cases of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders and how their futures might be affected by tonight’s results.

Theory No. 1: Iowa matters because it affects the tone and volume of media coverageEvidence for the theory: One funny thing about Iowa is that performance relative to the media’s expectations sometimes matters more than performance in any absolute sense. Democrat Gary Hart got a huge bounce out of Iowa in 1984 despite having lost it to Walter Mondale by more than 30 percentage points — all because he did a little better than polling and the media anticipated.

What it means for Trump: You can’t understand the Trump phenomenon without understanding his formidable skill in exploiting the tropes of American political journalism — or the media’s disproportionate coverage of him. But what that means for the post-Iowa spin is harder to say. Trump has almost 100 percent name recognition, and he’s sure to be the lead story win or lose; that might make this factor less important than usual. If the media eventually tires of Trump, however, or another candidate is elevated to receive roughly coequal coverage with him, there could be damage to Trump’s standing in the polls.

What it means for Sanders: The media may not care much for Bernie Sanders, but it would love to see a competitive Democratic race. The press also has a habit of blowing even minor Hillary Clinton stories out of proportion. So if Clinton lost Iowa, the media environment would be extremely toxic for her, at least for a few weeks. With that said, although Clinton’s image has fluctuated a lot with general election voters, she’s historically been resilient with her Democratic base.

Theory No. 2: Iowa matters because it generates a ‘bandwagon effect’Evidence for the theory: Lots of academic research suggests that voters like to join the winning team, throwing their support to candidates who are performing well in polls. This matters a lot more in primaries than in general elections because voters are usually choosing from among several acceptable candidates.

What it means for Trump: Trump’s whole campaign is predicated on the notion of his being a “winner”; he’s the guy who spends half his speeches (I’m not exaggerating much) reciting polling results. That could make a loss in Iowa dangerous for him. But doesn’t that also imply that lots of voters would join the Trump bandwagon if he won? Maybe, but Trump may already have most of those bandwagon voters given that most Republicans already expect him to be their nominee.

What it means for Sanders: In contrast to Republicans on Trump, Democratic voters are skeptical that Sanders can defeat either Hillary Clinton or the Republican nominee. A win in Iowa could go a long way toward easing those doubts.

Theory No. 3: Iowa matters because it sends a signal to ‘party elites’ and helps them coordinate on a candidateEvidence for the theory: In cases where party elites3 haven’t settled on an acceptable candidate during the “invisible primary,” they’ve tended to flock to one quickly after Iowa and the other early-voting states, with large numbers of endorsements suddenly coming that candidate’s way. The clearest examples are Michael Dukakis in 1988, John Kerry in 2004 and John McCain in 2008.

What it means for Trump: Trump is problematic both for the Republican Party and for theories about the influence of party elites. The twist is that those party elites seem to hate Ted Cruz even more; in fact, there has been something of a coordinated effort to deny Cruz a win in the Iowa caucuses, even if it means boosting Trump. Could that tacit backing turn into explicit support for Trump if he wins Iowa? It’s possible; you’ve already seen some capitulation to Trump from people you might never have expected. But Marco Rubio is much more in line with the candidates that party elites usually prefer. A strong performance by Rubio could (finally) yield a surge in endorsements and financial support; a weak one would leave party elites flailing around.

What it means for Sanders: Democratic elites have already thrown their lot in with Clinton. It wouldn’t be surprising to see Sanders pick up a handful of endorsements if he wins Iowa and New Hampshire. But most influential Democrats will probably go down with the Clinton ship.

Theory No. 4: Iowa matters because it winnows the field, with candidates dropping out if they fail to perform wellEvidence for the theory: As we found when developing our primary forecast models, the rate of candidate dropouts accelerates considerably after Iowa and New Hampshire.

What it means for Trump: This is another risk factor for Trump, who has less second-choice support than rivals Cruz and Rubio in many polls, implying that they’d benefit more as other candidates exit the race. With so many Republican campaigns still so well-funded, however — Jeb Bush’s campaign and his super PAC have a combined $66.5 million in cash on hand, for example — the power of the purse to compel struggling candidates out of the race may be diminished.

What it means for Sanders: The winnowing factor is less important when the field is already small. Martin O’Malley is the only remaining Democrat besides Sanders and Clinton. In Iowa, the O’Malley vote could make some difference because of the Democrats’ caucus rules. But nationally, he’s at 3 percent in the polls, and what he does just isn’t going to matter much.

Theory No. 5: Iowa matters because it’s the first glimpse of whether polls match the reality on the groundEvidence for the theory: The first four theories involved voters changing their preferences based on the events set in motion by Iowa. This one’s in a different category; instead, it’s a reflection of our imperfect knowledge of voter behavior. If there’s one “Polling 101” lesson that we wish more people heeded, it’s that polls can be way off the mark in primaries and caucuses, even when they’re usually pretty accurate in general elections.

What it means for Trump: Earlier in the campaign, we were often exasperated by the media’s obsession over Trump’s polls at points in time when they’d historically lacked much predictive power. Polls are more meaningful now that the voting is about to start, but even so, misses of 5 to 10 percentage points are not uncommon in early primaries and caucuses. How many of Trump’s supporters will turn out to vote is perhaps the most important question in the campaign right now; the polls could have it wrong in either direction. As is the case in general elections, furthermore, polling errors are likely to be correlated from one state to the next. If Trump significantly underperforms his polls in Iowa, for example, there’s a good chance his New Hampshire numbers are inflated too.

What it means for Sanders: Polls have been pretty wild on the Democratic side as well; consider, for instance, that polls released in Iowa in the past month have shown everything from a 29-point lead for Clinton to an 8-point lead for Sanders. Tonight will resolve at least a few of our questions about where the race stands.

http://c.espnradio.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2669580/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-02-01-153020.64k.mp3Our elections podcast just launched. Listen to the latest episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

January 31, 2016

Hillary Clinton May Win Iowa After All

It would be entirely reasonable to presume that Bernie Sanders has momentum in Iowa. He’s gained on Hillary Clinton in national polls. He keeps pulling further ahead of Clinton in New Hampshire. And he’s made substantial gains in Iowa relative to his position late last year. December polls of Iowa showed Sanders behind by an average of 16 percentage points; the race is much closer now.

There’s just one problem: Sanders’s momentum may have stalled right when it counts the most.

The Des Moines Register’s Iowa poll released Saturday, for example, had Clinton leading Sanders by 3 percentage points. That means Iowa is close and winnable for Sanders; polling errors of 5 or even 10 percentage points are not uncommon in the caucuses. But it also means that Sanders hasn’t gained on Clinton. The previous Des Moines Register poll, released earlier in January, showed Clinton up by 2 percentage points instead.

The same story holds for other polling companies that have surveyed Iowa twice in January. A couple of these pollsters — American Research Group and Quinnipiac University — show Sanders leading. But they don’t show him gaining; Sanders also led in the previous edition of the ARG and Quinnipiac surveys.

No late surge for SandersPOLLSTERMOST RECENT POLLPREVIOUS POLLCHANGEAmerican Research GroupSanders +3Sanders +3—Gravis MarketingClinton +11Clinton +21Sanders +10Marist CollegeClinton +3Clinton +3—Public Policy PollingClinton +8Clinton +6Clinton +2Quinnipiac UniversitySanders +4Sanders +5Clinton +1Des Moines RegisterClinton +3Clinton +2Clinton +1The only polling firm to show Sanders making substantial gains in January is Gravis Marketing. It had him trailing Clinton by an implausible 21 points earlier this month. Now, it has him down by 11. That may reflect reversion to the mean (or herding) after a seeming outlier more than any genuine movement toward Sanders.

Overall, Clinton is ahead by 5.3 percentage points in FiveThirtyEight’s weighted polling average in Iowa. She led Sanders by exactly the same margin, 5.3 percentage points, on Jan. 15.

What’s blunting Sanders’s progress? Actually, it might not have a lot to do with Sanders. Clinton isn’t an easy mark. She remains extremely popular with Democrats, including in Iowa, where her favorable rating was 81 percent in the Des Moines Register poll. (Sanders’s favorable rating was 82 percent in the same poll.)

And Clinton has an impressive ground game in Iowa, where she has field offices throughout the state and voter outreach tactics modeled more on President Obama’s successful 2008 campaign than her own failed one. Clinton’s campaign takes a highly localized approach to Iowa, I learned on a visit to her Davenport field office earlier this month, with volunteers responsible for contacting a parcel of voters in a particular neighborhood again and again until the caucuses.

Sanders has an impressive ground game also. In fact, it’s not always easy to tell the campaigns apart. His campaign and Clinton’s use many of the same tools and strategies, and there’s a lot of cross-pollination into both camps from former members of the Obama 2008 campaign team.

On a visit to Sanders’s Des Moines headquarters this month, I discussed with his staffers an unusual occurrence in the polls: Some Iowa surveys, like the previous version of the Des Moines Register poll, showed the number of undecided voters increasing as the vote approached.

The Sanders staffers had a convincing-sounding explanation. Since most Democrats like both candidates, it wasn’t just a matter of flipping Clinton voters into Sanders voters. The voters had to proceed through a liminal stage first: the state of being undecided.

But it may be that some of those voters, after flirting with the idea of voting for Sanders, wind up sticking with Clinton in the end.

Read more:

Four Roads Out Of Iowa For Republicans

What Happens If Bernie Sanders Wins Iowa

Check out our latest forecasts for the 2016 presidential primaries.

January 30, 2016

Four Roads Out Of Iowa For Republicans

Yes, I know: There’s an incredibly handsome orange-haired man from Queens sitting atop the polls. Donald Trump has a serious chance of winning the Republican nomination — not words I’d have expected myself to be writing six months ago.1 Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, however, still have a shot to knock Trump off his pedestal. Jeb Bush, John Kasich and Chris Christie might have a chance too, although they’ll need a lot of things to break right for them.

The dominoes will begin falling after the Iowa caucuses Monday night. It seems to me there are four basic narratives that could emerge from the state. (By “narratives,” I mean how the media, Republican party elites and the other candidates will interpret the results. Be warned: How the media responds is sometimes way more predictable than how voters do.) They depend, respectively, on whether Trump beats Cruz and on how well Rubio does.

About Rubio: What it means to perform “well” is obviously a little subjective, but how a candidate does relative to his polls is usually a pretty good guide to the spin that eventually emerges. Recent Iowa polls have Rubio in third place, with a vote share in the mid-teens. If Rubio finishes in the low teens or worse, his performance is likely to be regarded as disappointing (he’ll also be at risk of falling behind Ben Carson or another candidate into fourth place). If he’s in the high teens or better, he’ll probably be regarded as having momentum, especially if he slips into second place. Our models also think there’s an outside chance — 7 percent to 10 percent, depending on which version you look at — for Rubio to win Iowa. That’s mostly out of an abundance of caution: Iowa polls are sometimes wildly off the mark.2 The scenarios below contemplate Rubio finishing in second or a strong third place, but not winning. Of course, there could be even crazier outcomes still — our models give Carson around a 1-in-100 chance of winning Iowa, for example — but the four cases we describe below are the ones we take to be most likely.

Road No. 1: Trump beats Cruz, and Rubio does wellThis seems to be the result the cognoscenti are expecting. Betting markets give Trump a 2-in-3 chance to win Iowa; our models now have him favored too, although not by as clear a margin as the markets. Meanwhile, there’s a lot of talk, with some justification, that Rubio has “momentum” going into the caucuses.

No matter what happens, the first headlines that emerge from Iowa are likely to be about Trump. Depending on exactly how well Rubio does, however, the conventional wisdom could congeal into anticipating a two-man race between Trump and Rubio. Perhaps that’s the matchup Republicans deserve. Rubio and Trump offer the two clearest visions for what the Republican Party’s future might look like: a forward-looking but emphatically conservative party in Rubio’s case, a populist-leaning and perhaps radically changed one in Trump’s.

It’s also the matchup that Republican “party elites” seem to want. By mounting an anti-Cruz campaign in Iowa, they were necessarily helping Trump, perhaps on the theory that another candidate could emerge to defeat Trump later on. If Rubio performed well in Iowa, he’d look like that candidate, giving party elites as good an outcome as they had any right to expect.

The big caveat is that this was possibly an idiotic strategy to begin with; it’s nearly impossible to control either Trump or the media narrative surrounding him, and it might be even harder after a big win in Iowa. We’d want to look for active signs of party leaders moving toward Rubio — in the form of endorsements and explicit pressure on candidates like Bush to drop out of the race. If Republican bigwigs just sit passively golf-clapping the result instead, the Trump whirlwind could sweep the news about Rubio’s vaguely good finish off the front pages.

Road No. 2: Trump beats Cruz, and Rubio does poorlyGet your Drudge Sirens ready. If Trump not only wins but blows out the competition, with both Cruz and “savior” Rubio flopping, Monday will be one of the most famous days in American political history.3 Although there might be some hope of anointing a new savior in New Hampshire — Bush, Kasich or Christie — other party elites might begin to capitulate toward Trump, as is already happening to some degree.

Could Trump get off to an extremely strong start, winning the first several states along with most of those in the “SEC Primary” on March 1, only to fail later on? Well, perhaps. The GOP calendar backloads a lot of winner-take-all or winner-take-most primaries in blue and purple states into April and beyond, so Trump could emerge with huge amounts of momentum but not be anywhere close to mathematically clinching the nomination. To some extent, we’d be in uncharted territory, since a Trump-like candidate has never gotten off to such a strong start before. But for Trump to lose, someone would have to beat him, and if both Cruz and Rubio blew their chances, it’s hard to know which candidate that would be. In my view, it would be safe to say that Trump had become the odds-on favorite to win the nomination, but where he’d fall on the spectrum between 51 percent and 99 percent I’m not sure.

You might notice I’ve pulled a little trick there, however, presuming a “blowout win” for Trump when that wouldn’t necessarily be the case. Suppose Rubio did badly, but Trump only narrowly beat Cruz. Would that make a difference? My guess is that it wouldn’t make a lot of difference — a Trump win is a Trump win — unless the vote were so close that (as in 2012) the outcome was uncertain well after midnight.

But this is one of the trickier cases. Cruz’s campaign would point toward how it had beaten expectations despite “the establishment” having stacked the deck against it. Which would be a pretty reasonable argument! But that doesn’t mean that Republican elites, having registered their discomfort with Cruz, would be receptive to it.

Road No. 3: Cruz beats Trump, and Rubio does poorlyIf Cruz beats Trump, however, Cruz will look Teflon, and the Republican elites who tried to stop him will seem feckless. Also, since the conventional wisdom no longer anticipates a Cruz win in Iowa, it will be more surprising and possibly produce a bigger Cruz bounce. Furthermore, suppose that Rubio has a poor night. This is the nightmare case for Republicans who were hoping to stop Cruz.

It would also make New Hampshire really interesting. Trump begins with a fairly large lead there, and Cruz is not a good fit for the state. So even a fairly large bounce for Cruz (and an erosion in Trump’s support) could leave both candidates stuck in the high teens or low 20s, not necessarily enough to win. It’s possible that someone like Kasich or Bush could emerge under those circumstances.

We’d also want to look for signs of whether Cruz’s win in Iowa was an indication of Cruz’s strength or Trump’s weakness. If it seemed to be a result of Trump’s failed ground game, maybe that wouldn’t be as much of a problem for Trump in New Hampshire and other primary states, where the barriers to participation are less than in a caucus. Nonetheless, Trump would be — for the first time all campaign — a loser. To the extent his support is partly based on a bandwagon effect, it would be seriously tested.

Road No. 4: Cruz beats Trump, and Rubio does wellIf both Cruz and Rubio have strong nights in Iowa, however, the meaning is clearer: Trump didn’t live up to the hype. There would be questions about whether Trump’s support in polls was a mirage to begin with, whether it had collapsed at the last minute because of voter dissatisfaction with his having skipped the Republican debate, or whether his lack of a turnout operation had foiled him. Those questions would be important for determining whether Trump had a chance to recover in New Hampshire. But in terms of the media narrative, they’d all be variations on the theme that Trump had gone bust.

In some ways, the Republican primary might even start to look fairly conventional. An “outsider” candidate with evangelical support would have won Iowa. A couple of “insider” candidates would be looking to emerge out of New Hampshire, with Rubio having a leg up because of his strong Iowa showing. Trump wouldn’t necessarily disappear — the media will keep writing him into the plot so long as he is willing — but it might be as more of a Newt Gingrich-esque sideshow, a candidate who wins a few states here and there but has little chance of commanding a majority. If we enter Iowa in a Trumpnado and exit it with what seems to be a fairly normal Republican race, that might be the biggest surprise of all.

Read more:

Four Roads Out Of Iowa For Republicans

What Happens If Bernie Sanders Wins Iowa

http://c.espnradio.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2667975/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-01-29-163515.64k.mp3Our elections podcast launched this week. Listen to the latest episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

January 29, 2016

What Happens If Bernie Sanders Wins Iowa

If you’re dreaming of Bernie Sanders beating Hillary Clinton, you know how the movie begins (he wins Iowa on Monday1), how it ends (he accepts the nomination to a Simon & Garfunkel tune), and one of the major plot lines (black, Hispanic and moderate Democrats, who for now prefer Clinton to Sanders, begin to #feelthebern). You also know who the hapless villain is: Democratic party elites (aka “the establishment”), who will be fighting Sanders every step of the way.

Otherwise, the details are fuzzy. We’re not quite sure how Sanders pulls off this Wes Anderson caper.

Sanders is highly competitive in the first two states, Iowa (where he’s only narrowly behind Clinton) and New Hampshire (where he leads her). However, those states are favorable for Sanders demographically, with Democratic turnout dominated by Sanders’s base of white liberal voters. The question is whether Sanders can expand his coalition into more diverse states that will vote later on and where African-Americans, Hispanics and white moderates make up a larger share of the electorate. He won’t need to win every voter in these groups, but he’ll need enough of them to go from the roughly one-third of Democratic voters he captures in national polls now to the 50-percent-plus he’ll need eventually.

The first challenge for Sanders is that he appears to be trailing in Iowa. Our “polls-only” forecast gives Clinton a 68 percent chance of winning the state, compared with 32 percent for Sanders, on the basis of her being about 4 percentage points ahead in our weighted polling average. Our “polls-plus” forecast, which assigns some additional credit to Clinton because of her massive lead in endorsements, has Clinton as a 76 percent favorite.

To be clear, those forecasts aren’t predicting that Clinton will win Iowa by 30 percentage points. They’re projecting a close finish and saying that Clinton is somewhat more likely — a little better than a 2-to-1 favorite — to come out on top. But Iowa polls are not all that accurate, and even some polls that show Clinton ahead envision Sanders winning if his voters come out. A Sanders win wouldn’t be all that much of an upset, in other words, at least relative to where the polls stand now.

At the same time, it’s not clear that Sanders has momentum in the Hawkeye State. He made major gains when the first few polls came out in January relative to where they’d been in December, making the race much closer. But he’s never quite surpassed Clinton. In fact, Clinton’s had roughly the same 4-point lead in our polling average for a couple of weeks now. We’ll know more after the Des Moines Register, which previously had Clinton 2 points ahead, releases its excellent poll Saturday.

What if Sanders wins Iowa?But suppose Sanders does win Iowa. The next step is relatively easy: He’ll probably also win New Hampshire, where the demographics are even better for him, he has a geographic advantage as a Vermont senator (that really does matter) and he already leads Clinton by 13 percentage points. (Obligatory reminder: Clinton won New Hampshire in 2008 despite being way behind in the polls after Iowa.)

If Sanders pulls off the twofer, you’ll be hearing these facts often:

No candidate (Democrat or Republican) has lost the nomination after winning both Iowa and New Hampshire since Ed Muskie in 1972.2No candidate has won the the nomination without winning either Iowa or New Hampshire since Bill Clinton in 1992.But there are two reasons to think that Hillary Clinton, like her husband, could defy the prevailing trend. One is the issue I mentioned earlier: Sanders’s success in Iowa and New Hampshire might be a reflection of their Sanders-friendly demographics rather than a harbinger of Clinton’s doom. That seems to match the polling we’re seeing in other states, where (for instance) Sanders is doing relatively well in Wisconsin, which also has plenty of white liberals, but struggling in North Carolina, which has fewer.

Unlike on the Republican side, this isn’t necessarily a choice between head and heart for Democratic voters. Democrats aren’t just backing Clinton because they think she’s more pragmatic or electable; most of them are closer to Clinton than Sanders on the issues. So even if Sanders gained a lot of momentum after the early states, he could have trouble closing the sale with voters who think he’s a little too far to the left.

The other factor is that Clinton has the Democratic machine more or less fully behind her. What influence “the party” exerts over voters is a matter of considerable debate and importance, but empirically, endorsements have continued to hold predictive power throughout the nomination process and not just in Iowa and New Hampshire. Clinton also begins with a large edge in superdelegates, who make up about 15 percent of delegates to the Democratic convention. Those superdelegates could switch to Sanders if it looked like he had a mandate from Democratic voters, but they’d probably tip the balance to Clinton in a too-close-to-call race.

Furthermore, although it’s true that no candidate since Bill Clinton has won the nomination without winning one of the first two states, that may be because the establishment has always had an acceptable candidate to choose from. In 1992, when party leaders were lukewarm on both Iowa winner Tom Harkin and New Hampshire winner Paul Tsongas, somehow the rules were bent, Clinton was billed as the “comeback kid” despite losing each of the first four states,3 and he went on to win the nomination fairly easily.

But Sanders would have an avalanche of momentum going for him after wins in Iowa and New Hampshire. The national press corps, which spins even minor stories into crises for Clinton, would portray Clinton’s campaign as being in a meltdown. Momentum usually matters in the primaries — and sometimes it matters a lot — but exactly how many Democrats would change their votes as a result is hard to say. The wave of negative coverage might be especially bad for Clinton, but it’s also possible that, because the media has sounded false alarms on Clinton before, she’d be relatively immune to the effects of another round of bad press. One factor helping Sanders: Voters who had been attracted to his message before, but who weren’t sure he could win, would mostly have their doubts removed after he beat Clinton twice.

It’s also possible that Democratic party elites would panic. A good indicator for this will be whether there would be renewed efforts to draft Joe Biden, or some other candidate, such as John Kerry, into the race. That would probably constitute a misreading of the situation. Sanders’s support reflects support for Sanders more than it does an anti-Clinton vote, whereas there’s never been much of a market for Biden. The more calls you hear to “draft Biden,” the more likely it is that Clinton’s support will be undercut when it’s far too late for party elites to come up with a viable alternative and that Sanders wins the nomination.

The first chance we’d have to get a read on the situation would be Nevada, which votes Feb. 20. (Nevada comes before South Carolina for Democrats; the reverse is true for Republicans.) Nevada’s one of the hardest states to forecast, however: There’s not a lot of polling there, and I’m not sure I’d trust the polls anyway in a low-turnout caucus. Jon Ralston, the uncannily accurate Nevada journalist, gives Clinton a “slight edge” in the state. That sounds about right. Clinton has a strong ground game in Nevada and could perform well among Hispanics. Sanders has advertised heavily in Nevada, and voter enthusiasm could be important in the state, especially if he won support from Nevada’s heavily unionized workforce.

One state that doesn’t look good for Sanders is South Carolina, where Clinton is ahead by 31 points and where the Democratic electorate is majority black and relatively conservative. If Sanders wins there, or comes within a few points of doing so, that will be an unambiguous sign that Clinton is in deep trouble.

If Clinton’s firewall holds in South Carolina, however, she also figures to perform well in the “SEC Primary” states of March 1, at which point she’d potentially build up a fairly large delegate lead and tamp down some of the panicky media coverage.

What if Sanders loses Iowa?It’s probably over. Not that I’d expect Sanders to drop out of the race. Nor would I expect the media to stop covering it. Depending on Clinton’s margin of victory, you’d probably see some headlines about her resilience, but others saying the results had “raised doubts” about her campaign.

None of that would necessarily matter. Iowa should be one of the half-dozen or so most favorable states in the country for Sanders; New Hampshire is one of the few that ranks even higher for him. If Sanders can’t win Iowa, he probably won’t be winning other relatively favorable states like Wisconsin, much less more challenging ones like Ohio and Florida. His ceiling wouldn’t be high enough to win the nomination unless something major4 changes.

http://c.espnradio.com/s:5L8r1/audio/2667975/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-01-29-163515.64k.mp3Our elections podcast launched this week. Listen to the latest episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

January 28, 2016

What Would The Republican Race Look Like Without Trump?

If the debate in South Carolina two weeks ago represented the Republican primary in microcosm, this one was like a randomized control trial: What would the GOP primary look like without1 Donald Trump?

True, Trump’s absence was hard to ignore during the first 30 minutes of the debate. It didn’t help that the Fox News moderators focused their first few questions around Trump. The other candidates seemed a little unsure of themselves.

But by the second half of the debate, you had — as Chris Wallace reminded Ted Cruz — an actual debate. It was a good and vigorous discussion, with lots of tough questions posed by Wallace and Megyn Kelly. And it gave us a glimpse of which candidates are most diminished by Trump, and which actually seem to benefit from his presence.

According to our staff grades,2 the candidate with the best night was someone who’s usually forgotten about … Rand Paul. With his libertarian-leaning views, Paul is a hard guy for the media to characterize: He’s certainly not an “establishment” candidate, but he also doesn’t fit the stereotype of a fire-breathing, red meat conservative. In an election without Trump, Paul might be among the more interesting candidates for the press to cover. In an election with Trump, he’s treated as an afterthought.

FiveThirtyEight’s Republican debate gradesCANDIDATEAVERAGE GRADEHIGH GRADELOW GRADERand PaulBACMarco RubioB-A-CJeb BushB-A-DChris ChristieB-B+DTed CruzC+B+DJohn KasichC+BDBen CarsonD+BFThe bar is pretty low, but Jeb Bush also had one of his better performances, receiving a B- grade. It’s hard to know how much of Bush’s disappointing campaign can be blamed on Trump: Many of his problems were apparent from the start. But every candidate has his problems, and Bush isn’t fundamentally all that different from Mitt Romney, who won the nomination four years ago. Trump seems to have a particular talent for drawing out Bush’s least appealing qualities, while Bush appeared more self-possessed without Trump on stage.

By contrast, our group thought that Ted Cruz had his worst performance of the cycle, giving him a C+. Without his frenemy Trump on stage, Cruz had two problems: First, as the highest-polling candidate at the debate, he was more of a lightning rod for attacks. Second, without the histrionic Trump as a comparison, Cruz’s delivery showed its rough edges, at times being both corny and sanctimonious. More importantly, Cruz’s strategy of positioning himself as the “compromise” between Trump and the more conventional candidates no longer looks so brilliant anyway as Republican leaders have turned on him.

Marco Rubio’s performance didn’t seem to be affected much one way or the other by Trump’s absence. That seems to be true of Rubio in general, actually: He isn’t affected all that much by the context, polling about equally well with every demographic group in every state. Unfortunately for Rubio, that’s not good enough to win him any states, although there are signs of forward movement for him in Iowa.

Still, I find it pretty hard to guess how Republican voters will react to all of tonight’s action. Take Rubio, for instance: I thought he was pretty solid overall, but that he got roughed up by Kelly on immigration. How will voters weigh those two things? Both the pundit reaction and the Fox News focus group were more sympathetic to Rubio than I would have guessed, but neither of those are the most reliable benchmarks.

Instead, we’re in the “fog of war” phase of the campaign. It’s hard for reporters, including us at FiveThirtyEight, to judge what the debate looks and sounds like to voters at home who aren’t as immersed in the campaign3 and who haven’t heard the same catch phrases delivered so many times. Moreover, it’s not just any Republican voters but a very narrow subset of them who matter right now — the perhaps 125,000 or 150,000 Iowans4 who will caucus next Monday, maybe one-third of whom are undecided or could still plausibly be persuaded to change their minds. That’s somewhere in the neighborhood of 30,000 to 50,000 people who will go a long way toward determining the Republican Party’s future. And I wouldn’t put a great deal of trust in us or any other journalists’ guesses about what they might be thinking.

For that matter, while it was predictable that many reporters couldn’t resist the storyline that Trump won the debate by not showing up for it, I’m not sure that’s so obvious either. I understand the case: Trump’s leading rivals didn’t have a great night, and Trump continued to command the lion’s share of attention despite not being on stage. But Trump pretty much always dominates the media conversation; that’s priced into the polls already, and we’ll still have to see how well he closes the sale with actual Iowa voters. For the next four days, the impressions of those 50,000 or so persuadable Iowans is all that matters.

January 27, 2016

Sorry, Bloomberg: Trump Is Already A Third-Party Candidate

A presidential election between Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders — still a fairly unlikely prospect1 but, well, never say never — might seem like the perfect opportunity for an independent candidate to enter the race. Sanders would be the most left-wing nominee since George McGovern, who lost by 23 points to Richard Nixon in 1972. Trump, who has a net favorable rating of -25 percentage points among general election voters, would begin the race as perhaps the most unpopular major-party nominee ever.

It wouldn’t be as easy as it sounds for an independent, though. That’s partly because, in the conditional probability warp zone I’m asking us to consider, Sanders and Trump will each have won their respective nominations and demonstrated some political acumen in the process. They might be below-average candidates, but they wouldn’t be total pushovers. It’s also because, as Brendan Nyhan reminds us, there are some significant structural challenges facing an independent candidate. Among other things, a centrist, independent candidate would probably underperform a bit in the Electoral College relative to his or her share of the popular vote.

But neither of those problems are quite what I had in mind. Instead, there’s a more basic issue: It’s hard to find the right candidate for the job.

Take former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who has been floating trial balloons about an independent bid2 and who seems more likely to run in the event of a Trump vs. Sanders matchup. Bloomberg, worth an estimated $49 billion, would have no trouble financing a presidential campaign. Surely he could find some wiggle room between Trump and Sanders?

Maybe not. Sanders, obviously, would be an extremely liberal Democratic nominee. Trump, perhaps less obviously, might wind up being fairly left-of-center for a Republican candidate. So the center-left Bloomberg would be swimming in a crowded lane.

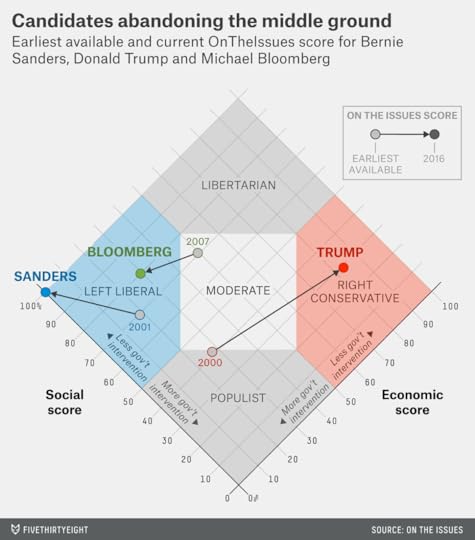

We can visualize this using data from OnTheIssues.org, which categorizes the ideological position of politicians based on their public statements and voting records. OnTheIssues helpfully distinguishes between social and economic issues, allowing for candidates to be “populist” (economically liberal and socially conservative) or “libertarian” (economically conservative and socially liberal) rather than simply conventionally liberal or conservative. And because OnTheIssues has been around for some time, we can track how a candidate’s positions have “evolved” with the political winds. The chart below shows the scores for Trump, Sanders and Bloomberg — both where they stand now and how they positioned themselves earlier in their careers.3

Today’s Donald Trump is often described as a “populist.” But if you define “populism” as OnTheIssues does, meaning someone who’s socially conservative but economically liberal, that was more true of him back in 1999 and 2000. That’s when Trump was considering his own independent bid for president, calling for a wealth tax on multi-millionaires while already emphasizing the importance of America “[controlling] its own borders.” Recently, Trump’s positions have become more conservative, although they remain fairly idiosyncratic. Where he’d wind up as a general-election candidate is anyone’s guess, but it would probably be somewhere along the spectrum between populist and moderately conservative.

Sanders has also “evolved,” although less dramatically than Trump. He had a few traces of crusty, Vermont populism before, with relatively moderate positions on immigration and guns, but has gradually shed them to adopt more conventionally liberal positions. In fact, he’s become a sort of liberal lodestar: Sanders now rates as maximally liberal on both economic and social policy, according to OnTheIssues.

Bloomberg, who was registered as a Republican when he ran for mayor in 2001 and 2005 but became an independent in 2007,4 has also moved to his left and now holds positions that, while rightward of Sanders’s, aren’t appreciably different from Barack Obama’s or Hillary Clinton’s. In the event of a presidential bid, Bloomberg would presumably pivot back toward the center. He used to be a Democrat, but even in his days as a nominal Republican he was really a center-left moderate. And because of his

January 26, 2016

Does Donald Trump Need To Win Iowa?

For this week’s 2016 Slack chat, the FiveThirtyEight politics teams ponders how important the Iowa caucuses are to Donald Trump.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): We’re less than a week out from the Iowa caucuses, and Donald Trump has overtaken Ted Cruz as the most likely winner in the Hawkeye State, according to our polls-only forecast. (And he’s closed the gap on Cruz in our polls-plus forecast.) But there are still doubts about whether Trump can turn out his voters. So, does Trump NEED to win Iowa to win the nomination?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Ted Cruz wins Iowa, John Kasich wins New Hampshire, and Trump emerges as the consensus candidate. I’m joking. Maybe.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): The answer to me is “no, he doesn’t.” I can envision Trump winning without Iowa. But by winning it, he would greatly increase his chances. He’s already over a 50 percent chance to win in both of our New Hampshire forecasts and both of our South Carolina forecasts.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): I don’t think he needs to … he’s the new Teflon candidate, right? Maybe he will even defy the momentum convention. (Look at that rhyme.)

natesilver: OK, I’ll bite. I think an Iowa loss would be pretty bad for Trump. Although maybe not because of “momentum.”

An Iowa loss is bad because the most probable cause of the loss is that his voters aren’t showing up. That means his polls could be inflated everywhere, although probably more in caucus states than in primary states.

The expectations game is harder to gauge, I think, because Trump’s relationship with the media is so oddly codependent.

harry: The question is whether a campaign all about “winning” can take losing. Trump hasn’t lost yet, and the few times he’s gone down in the polls, he’s gone bonkers.

natesilver: He hasn’t lost yet, and he hasn’t really had a moment yet where he had a string of bad polls. It’s interesting too that his top attribute in last night’s ABC News poll was electability. That’s the one where he had the largest lead over his rivals. That contradicts the data showing that Trump is extremely unpopular with general-election voters. But as long as Trump’s winning states and winning in the polls, GOP voters will think he’s a winner, and a great general-election candidate.

clare.malone: I think the idea of how Trump will actually handle losing is an interesting one to contemplate. Being too dismissive or defensive could make the whole enterprise crumble in on itself. People see the Emperor without his clothes, that kind of thing. And for a campaign that seems light on professional political operatives, it would be interesting to see the strategy that would emerge out of an Iowa loss.

harry: Of course, here’s the thing: Even if he loses in Iowa, he still has New Hampshire. Will his 15 to 20 percentage point lead collapse in a week?

micah: It’s possible, right?

clare.malone: I think that scenario is unlikely to happen; maybe Trump supporters in New Hampshire would even be galvanized all the more to get out to the polls and help their guy if he loses in Iowa.

micah: Well, it depends on why he lost in Iowa.

natesilver: If he loses Iowa, it’s also very possible that he’s not actually leading by 15 points in New Hampshire to begin with. You’re underselling the uncertainty in polls. Especially for an unconventional candidate like Trump.

By the same measure, if he way overperforms the polls in Iowa … well, look out, because maybe all those people showing up at rallies really are going to turn out.

clare.malone: What a time to be alive.

harry: Yes, I have to agree with that: two feet of snow in New York and a Trump win in Iowa.

natesilver: Our polls-only forecast has Trump with a 67 percent chance of winning New Hampshire. Which is pretty good for Trump, but also leaves open the distinct possibility he won’t win the state, especially if he loses Iowa.

A 15-point lead — actually, it’s an 18-point lead in our forecast — just isn’t anywhere near as solid in the New Hampshire primary as it would be in a general election. (If a candidate led by 18 points at this point in a general election, he’d be 99+ percent to win.) Especially when there are five other candidates who have some nonzero chance of winning the state.

harry: Right, I should point out that the non-poll factors, such as endorsements, still suggest that Trump isn’t anywhere near as strong as the polls suggest. Now that could mean one of two things.

Endorsements don’t matter — a lack of support from elected officials and party operatives won’t hurt Trump.Or, that the polls may be off. Not in the sense that Trump ends up with 10 percent. But they could be off by enough to throw Iowa to Cruz by a decent margin, and then who knows what might happen.clare.malone: I don’t think Trump’s supporters care a whit about him having politician endorsements — to me it’s a moot point with them/him. Which defies the traditional patterns we have to go off of.

natesilver: Feel free to throw things at me for saying this, but there’s still a good case that Trump is over-performing the fundamentals. Now, at this point, that may not matter. Even if it’s a bubble, Trump may be able to ride that bubble all the way to the nomination, especially if he wins Iowa. But if something happens to reset the race –— notably, a loss in Iowa — there’s a chance the Trump bubble could burst.

clare.malone: (Harry lobs abacus)

micah: I still think there’s like a 15 percent chance that that happens.

natesilver: And remember, about HALF of New Hampshire voters make up their mind in the final WEEK.

http://c.espnradio.com/audio/2664556/fivethirtyeightelections_2016-01-25-174556.64k.mp3Our elections podcast launched this week. Listen to the full episode above, or subscribe on iTunes.

micah: So, if Trump loses Iowa, how do you all think he responds? Let’s say Cruz finishes with 36 percent and Trump with 25 percent.

clare.malone: I think he tries to spin it as “Iowa doesn’t matter, isn’t like most of the country” and then onward and upward with the arts. He’ll start touting bigtime New Hampshire poll numbers.

natesilver: It’s interesting (and maybe indicative) how y’all have framed that question. In a more traditional race, the big story of Cruz 36, Trump 25 wouldn’t be Trump losing Iowa but Cruz having won it. Cruz is the one who looks pretty Teflon in that case. And he’s Teflon with actual votes, not just in polls.

micah: But that won’t be the story this year.

So if Trump loses Iowa, what does his path to the nomination look like then? I take it he then NEEDS New Hampshire?

harry: If he were to lose Iowa and New Hampshire, it is difficult for me to see how he wins the nomination. It’s not impossible, but I just don’t see it.

clare.malone: I dunno, he could make a lot of inroads in the South. I mean, if he and Cruz are kinda competing for the same voters, this could still be a viable path.

natesilver: Trump could do well in the South, but the GOP’s delegate math doesn’t particularly favor the South. I think you all may be missing the forest for the trees there, though. If Trump loses both Iowa and New Hampshire, that means his big numbers in national polls may have been a mirage all along.

micah: Not necessarily … what if he loses by a hair?

natesilver: He could lose Iowa by a hair without underreporting his polls, but if he loses New Hampshire, that means something pretty significant has changed.

Either some other candidate gained huge momentum, the polls were way inflating Trump’s vote, or both.

Basically everything that I’m saying here boils down to NOBODY HAS VOTED YET. In the primaries, that’s not merely a perfunctory statement. Everything really can change once people start voting.

clare.malone: Nate’s pragmatism really puts a damper on wild-theories-on-a-Tuesday-afternoon time.

harry: Yeah, this point gets lost most of the time; people seem to think that primaries are just like general elections. Primary polling is far less accurate historically, and even if the polls are accurate, primaries can change very quickly. That doesn’t mean they will, but they can.

clare.malone: I mean, basically what we’re all looking to get out of the next couple of weeks is whether or not the Trump house is built out of sand and fog, or if it’s actually viable glass and steel — and then if all these supporters turn out to be real and he wins Iowa, etc., the GOP is really going to have to figure out what the heck to do all the way down the line in this primary season.

natesilver: Let’s spare a few moments for our friend Ted Cruz. Lots of powerful Republicans have spent three weeks trying to knock him out of the running in Iowa. But suppose he survives and wins the state by several percentage points. What does Cruz do then? And what does “the party” do, having fired a blank in their attempt to execute Cruz?

harry: Well, I think Iowa is a very Cruz-friendly state, so I don’t know what it means for “the party” on that score. I do think it’s good news for them, however. I continue not to understand why they are going after Cruz and not Trump. It’s one of the many things this cycle that just makes very little sense to me.

natesilver: Maybe they’re just not that bright. It was the same donor class that threw $100 million behind Jeb!, after all.

clare.malone: Well, Cruz might not play well in a lot of states still — yeah, what Harry just said. He’s playing on a certain kind of conservatism. I think what the party is going to do gets back to a previous chat where we discussed that nothing can be done until the establishment — sorry, Nate, the party elites — decide to unite behind one person. Then they can make better efforts.

micah: [Cue a pro-Rubio argument from Nate.]

harry: Nate loves Rubio like I love snow.

natesilver: Harry stop trying to hide your love for Chris Christie.

harry: Sorry, I’ve moved onto a new beau: John Kasich.

micah: Who does Clare secretly love?

clare.malone: I think I’m the only one without a fave!

natesilver: I thought you wanted to stand with Rand?

clare.malone: No, no. I am a rock. I am an island. No faves allowed.

natesilver: But back to those “party elites.” Weirdly, Trump wins Iowa, that’s a sign that they might have some influence after all.

clare.malone: Wait, why Nate? We can’t assign any of this Trump rise to just the power of the people? The elites always have to be behind it?

natesilver: Trump’s gained 5 percentage points or so in the Iowa polls since party leaders began their anti-Cruz kick.

clare.malone: Or maybe the Trump “he’s a Canadian” thing just worked really well.

micah: I agree with Clare.

natesilver: The timing doesn’t line up with that as well, though.

micah: Canadian + Trump’s general offensive. That timing matches up well enough.

harry: Truth is that it’s difficult to figure out whether X caused Y, or maybe Z did. But I do agree with Nate insofar as it wouldn’t be a negative indicator for party actor support. But again, I think it’s a very dangerous game to hope you can have Trump win Iowa and then beat him later.

natesilver: Yeah, that’s quite a feat they’re hoping to pull off. Kind of insane, really.

micah: So that brings me nicely to a final question: If Trump wins Iowa, how unstoppable does he become?

clare.malone: I think we’re basically all going to say versions of “not unstoppable,” right?

natesilver: Depends on a lot of things, including how Rubio does in Iowa and New Hampshire. If Iowa’s like Trump 31 percent, Cruz 23, Rubio 18 — then Rubio will probably be seen as the main challenger to Trump and might get a boost in New Hampshire.

If it’s Trump 31, Cruz 23, Carson 9, Rubio 8 … well, who knows what, but Trump looks a lot safer then.

micah: Yeah, not to respond to my own question, but I think the answer is: not unstoppable.

natesilver: Yeah, the short answer is “in pretty darn good shape, but not unstoppable.”

micah: Even if he wins Iowa and New Hampshire, a lot can happen. As our own David Wasserman has pointed out: The calendar is friendly to a March establishment comeback.

natesilver: Stop using the E word, Micah.

harry: If Trump wins Iowa, I think he can be stopped. I just don’t know how it happens exactly. I guess, as Nate points out, it would depend on how he did it. For Wasserman’s calendar to work out for the “establishment,” Rubio would probably need to do unexpectedly well in Iowa.

natesilver: There’s always Jim Gilmore, Harry. There’s always Jim Gilmore.

Check out the latest polls and forecasts for the 2016 presidential primaries.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 729 followers