Nate Silver's Blog, page 106

April 17, 2017

Politics Podcast: Trump’s Paths, Revisited

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

New to podcasts?

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew assess the election results in Kansas’s 4th Congressional District and the prospects in Tuesday’s special election in Georgia’s 6th District. As the Trump administration approaches Day 100, they also look back on Nate Silver’s article about the 14 wildly different paths that Trump’s presidency could take. Have any paths become more likely than others?

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

The Save Ruined Relief Pitching. The Goose Egg Can Fix It.

Hall of Fame relief pitcher Richard “Goose” Gossage isn’t the biggest fan of the “Moneyball” revolution. Here at FiveThirtyEight, we don’t think his expletive-laced tirades about nerds ruining baseball have always found their target the way his fastballs once did. But on one point, he’s absolutely right: The save is a stupid [bleep]ing statistic.

Gossage recently lashed out against modern closers — including all-time saves leader Mariano Rivera — arguing that they aren’t used in the right situations and that cheaply earned saves exaggerate closers’ value compared to the pitchers of his day. “I would like to see these guys come into more jams, into tighter situations and finish the game. … In the seventh, eighth or ninth innings. I don’t think they’re utilizing these guys to the maximum efficiency and benefit to your ballclub,” Gossage said. “This is not a knock against Mo [Rivera],” he continued later. “[But] I’d like to know how many of Mo’s saves are of one inning with a three-run lead. If everybody in that [bleep]ing bullpen can’t save a three-run lead for one inning, they shouldn’t even be in the big leagues.”

Gossage is right about pretty much all of that. A pitcher probably shouldn’t get much credit for handling just the final inning when his team has a three-run lead. Moreover, the top relief pitchers today are less valuable than they were in Gossage’s heyday in the 1970s and ’80s. In large part, that’s because managers are trying to maximize the number of saves for their closer, as opposed to the number of wins for their team. They’re managing to a stat and playing worse baseball as a result.

But there’s a solution. Building on the work of Baseball Prospectus’s Russell Carleton, I’ve designed a statistic and named it the goose egg to honor (or troll) Gossage. The basic idea — aside from some additional provisions designed to handle inherited runners, which we’ll detail later — is that a pitcher gets a goose egg for a clutch, scoreless relief inning. Specifically, he gets credit for throwing a scoreless inning when it’s the seventh inning or later and the game is tied or his team leads by no more than two runs. A pitcher can get more than one goose egg in a game, so pitching three clutch scoreless innings counts three times as much as one inning does.

The goose egg properly rewards the contributions made by Gossage and other “firemen” of his era, who regularly threw two or three innings at a time, often came into the game with runners on base, and routinely pitched in tie games and not just in save situations. I’ve calculated goose eggs for all seasons since 1930 — plus select seasons since 1921 — based on play-by-play data from Retrosheet. While Gossage ranks only 23rd in major league history with 310 saves, he’s the lifetime leader in goose eggs (677) — ahead of Rivera and every other modern closer.

PITCHER

SAVES

PITCHER

GOOSE EGGS

Mariano Rivera

652

Goose Gossage

677

Trevor Hoffman

601

Rollie Fingers

663

Lee Smith

478

Hoyt Wilhelm

641

Francisco Rodriguez

430

Mariano Rivera

614

John Franco

424

Lee Smith

589

Billy Wagner

422

John Franco

589

Dennis Eckersley

390

Trevor Hoffman

580

Joe Nathan

377

Bruce Sutter

557

Jonathan Papelbon

368

Tug McGraw

521

Jeff Reardon

367

Jeff Reardon

520

Troy Percival

358

Sparky Lyle

520

Randy Myers

347

Kent Tekulve

517

Rollie Fingers

339

Lindy McDaniel

507

John Wetteland

330

Mike Marshall

489

Francisco Cordero

329

Gene Garber

468

Roberto Hernandez

326

Ron Perranoski

444

Huston Street

324

Francisco Rodriguez

430

Jose Mesa

321

Todd Jones

425

Todd Jones

319

Billy Wagner

421

Rick Aguilera

318

Jesse Orosco

416

Robb Nen

314

Doug Jones

410

Tom Henke

311

Stu Miller

405

Goose Gossage

310

Roberto Hernandez

404

Jeff Montgomery

304

Randy Myers

404

Doug Jones

303

Darold Knowles

400

Career leaderboards for saves and goose eggs, 1930-2016

Plus select seasons since 1921

Source: Retrosheet

If managers want to squeeze every ounce of potential and talent out of their top relievers — maybe even doubling their value — it’s time to give up the save and embrace the goose.

Bullpens are still built around the save

While I come to bury the save, let me first sing some of its praises. The statistic, invented by the sportswriter Jerome Holtzman and officially adopted by Major League Baseball in 1969, came into the world with noble intentions. Relief pitchers were becoming more commonplace — the share of starts that ended in complete games would decline from 40 percent in 1950 to 22 percent in 1970. But these pitchers’ contributions were largely unheralded by fans, Holtzman correctly noted, because they rarely earned wins or losses and ERA did not reveal much about which relievers had been used in clutch situations.

Furthermore, some of the intuitions behind the save rule are correct. Modern statistics such as leverage index find that late-inning situations when a team holds a narrow lead are indeed quite important. For instance, an at-bat in the ninth inning when the pitcher’s team leads by one run has a leverage index of 3.3. That means it has more than three times as much impact on the game’s outcome as an average at-bat.

The problem is that there’s a fuzzy relationship between the most valuable relief situations and the ones that the save rewards. Take a look at the following chart, which shows the leverage index in different situations based on the inning and the game score:

Imagine that one evening, Pitcher A throws a scoreless eighth inning in a game where his team leads by one run — a situation that has a leverage index of 2.4 — before being pulled for his team’s closer. Meanwhile, in another ballgame on the other side of town, Pitcher B enters the game in the ninth inning when his team holds a three-run lead — a leverage index of just 0.9 — and gives up two runs but eventually records the final out. Pitcher A’s performance was quite valuable. Pitcher B’s was not — in fact, it was kind of crappy. But Pitcher B gets a save for his troubles whereas Pitcher A doesn’t. It doesn’t make a lot of sense.

There are other problems with the save, also. It doesn’t give a pitcher any additional reward for pitching multiple innings — even though two clutch innings pitched in relief are roughly twice as valuable as one. And a pitcher doesn’t get a save for pitching in a tie game, even though it’s one of the highest-leverage situations.

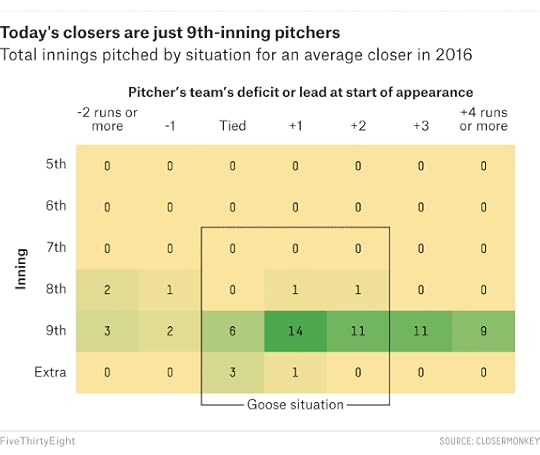

I know I’m not breaking much news here: Stat geeks have been complaining about the save for years. But don’t modern, post-“Moneyball” teams know better than this? Aren’t they using their best relievers in the highest-leverage situations, whether or not they yield a save? In a word: no. (In 11 words: Mostly not, except maybe for the Cleveland Indians and Andrew Miller.) The next table reflects how teams used their closers (as defined by closermonkey.com, a site that tracks bullpen usage obsessively) over the course of 2016, as measured by the number of innings the closer pitched in different situations:

The typical modern closer is really just a ninth-inning specialist. In 2016, the average closer threw 66 innings, and 56 of them came in the ninth inning. This included 11 innings in games where his team led by three runs in the ninth — a save situation, but not a high-leverage one. Conversely, it included just six innings in tie games in the ninth, which is not a save situation but is one of the highest-leverage situations you can find.

Again, this is pretty much how you’d use your bullpen if the goal was to maximize the number of saves for your closer (instead of the number of wins for your team). Managers seem so conditioned by the “only use your closer in the ninth inning with a lead” heuristic that they often use their closers in the ninth inning when their team leads by more than three runs, which is a not a save situation and is even more of a waste of the closer’s supposed talent. Baseball teams have supposedly reached a state of statistical enlightenment — but their closer usage is every bit as stubborn as NFL teams’ too-frequent refusal to go for it on 4th down.

Defining a goose egg

If managers were thinking about goose eggs rather than saves, they’d find plenty of better ways to use their best relievers. So let’s define a goose egg, officially. Just as for the save rule, the formal definition is a bit more complicated than the quick-and-dirty version I described above. But here goes:

A relief pitcher records a goose egg for each inning in which:

It’s the seventh inning or later;

At the time the pitcher faces his first batter of the inning:

His team leads by no more than two runs, or

The score is tied, or

The tying run is on base or at bat

No runs (earned or unearned) are charged to the pitcher in the inning and no inherited runners score while the pitcher is in the game; and

The pitcher either:

Records three outs (one inning pitched), or

Records at least one out, and the number of outs recorded plus the number of inherited runners totals at least three.

You’ll notice that the rules are more forgiving to pitchers who enter the game with runners on base, since these cases can have much higher leverage indexes than situations where the bases are empty. For instance, if a pitcher enters the game with two runners on and records a single out without allowing a run, he’ll earn a goose egg.

But the rule is strict about what it means by a scoreless inning. An unearned run cooks a goose egg, just as an earned run does. (The eggs are delicate.) And a pitcher doesn’t get a goose egg if a run scores while he’s in the game, even if the run was charged to another pitcher.

Overall, these rules can yield high goose-egg totals among many types of relievers, not just closers. That’s clear when you look at the goose egg leaderboard for 2016, for example. The Indians’ Miller and the Mets’ Jeurys Familia tied for the major league lead with 42 goose eggs last year, but Familia was used as a typical modern closer (and led the majors with 51 saves) while Miller often entered the game in the seventh or eighth inning. Mets setup man Addison Reed tied for fourth in the majors with 39 goose eggs last season, meanwhile, even though he had just one save.

TRADITIONAL STATS

GOOSE STATS

PITCHER

INNINGS PITCHED

ERA

W-L

SAVES

BLOWN SAVES

GOOSE EGGS

BROKEN EGGS

Jeurys Familia

77.2

2.55

3-4

51

5

42

7

Andrew Miller

74.1

1.45

10-1

12

2

42

7

Zach Britton

67.0

0.54

2-1

47

0

40

1

Addison Reed

77.2

1.97

4-2

1

4

39

5

Tyler Thornburg

67.0

2.15

8-5

13

8

39

7

Nate Jones

70.2

2.29

5-3

3

9

38

8

David Robertson

62.1

3.47

5-3

37

7

36

7

Sam Dyson

70.1

2.43

3-2

38

5

36

5

Roberto Osuna

74.0

2.68

4-3

36

6

35

4

Kelvin Herrera

72.0

2.75

2-6

12

3

35

9

Kenley Jansen

68.2

1.83

3-2

47

6

34

6

Familia, Miller tied for goose-egg lead in 2016

ERA and W-L record cover relief appearances only

Sources: FanGraphs, Retrosheet

Miller and Familia’s league-leading total would have been paltry by Gossage’s standards, however. In addition to being the lifetime leader in goose eggs, he’s also the single-season leader, having recorded 82 goose eggs (almost as many as Miller and Familia combined) in 1975, when he threw 141.2 (!) innings in relief for the Chicago White Sox.

The top firemen of Gossage’s day routinely had 60 goose eggs or more in a season, with their totals sometimes reaching into the 70s or — in the case of Gossage in 1975 and John Hiller in 1974 — the 80s.

Just one pitcher since 2000 — the Angels’ Scot Shields in 2005 — has had as many as 60 goose eggs in a season, however. These days, it’s rare for a pitcher to record even 50 goose eggs. League-leading goose-egg totals have plummeted even as saves have risen. The turning point seems to have been 1990, when Bobby Thigpen and Dennis Eckersley both beat the single-season saves record while rarely working more than one inning at a time. In the 1970s and 1980s, the average league leader in saves threw 112 innings over 69 appearances. Since 1990, by contrast, the average saves leader has also appeared in 69 games but has thrown only 71 innings.

THROUGH 1989

SINCE 1990

YEAR

PITCHER

GOOSE EGGS

YEAR

PITCHER

GOOSE EGGS

1975

Goose Gossage

82

1992

Doug Jones

67

1974

John Hiller

80

2005

Scot Shields

60

1965

Stu Miller

79

1990

Bobby Thigpen

56

1969

Ron Perranoski

79

1993

John Wetteland

56

1973

Mike Marshall

79

1996

Trevor Hoffman

55

1977

Rich Gossage

74

1993

Jeff Montgomery

54

1963

Dick Radatz

73

1996

Mariano Rivera

54

1965

Bob Lee

72

1998

Robb Nen

53

1964

Dick Radatz

71

2004

Brad Lidge

53

1979

Kent Tekulve

71

1998

Trevor Hoffman

51

1970

Lindy McDaniel

70

2000

Danny Graves

51

1983

Bob Stanley

70

2011

Jonny Venters

51

1950

Jim Konstanty

69

1997

Trevor Hoffman

50

1980

Doug Corbett

68

2011

Tyler Clippard

50

1965

Eddie Fisher

66

1991

Mitch Williams

48

1974

Tom Murphy

66

1993

Jim Gott

48

1974

Mike Marshall

66

1997

Jeff Shaw

48

1977

Sparky Lyle

66

2007

Heath Bell

48

1978

Rollie Fingers

66

1991

Paul Assenmacher

47

1980

Bruce Sutter

66

1992

Lee Smith

47

1972

Tug McGraw

65

1996

Roberto Hernandez

47

1979

Sid Monge

65

1996

Troy Percival

47

1980

Dan Quisenberry

65

1998

Jeff Shaw

47

1982

Bill Caudill

65

2003

Eric Gagne

47

1984

Willie Hernandez

65

2004

Tom Gordon

47

2004

Mariano Rivera

47

2008

Francisco Rodriguez

47

2014

Tony Watson

47

Single-season goose-egg leaderboard, 1930-2016

Plus select seasons since 1921.

Source: Retrosheet

Broken eggs and GWAR

(goose wins above replacement)

Having only learned about the goose egg a few moments ago, you might still be a little suspicious of it. Sure, closers are pitching fewer innings than they used to and getting fewer goose eggs. But perhaps they’re pitching more efficiently and providing more overall value as a result? It goes without saying that pitchers like Miller and Zach Britton are really good at their jobs.

To properly value relievers, we need a companion statistic called the broken egg, which is to a goose egg as a blown save is to a save. (I wanted to call this companion stat a “blown goose,” but my editors decided that vaguely dirty jokes were the hill they wanted to die on.) We’ll define it as follows:

A relief pitcher records a broken egg for each inning in which:

He could have gotten a goose egg if he’d recorded enough outs;

At least one earned run is charged to the pitcher; and

The pitcher does not close out the win for his team.

In other words, you get a broken egg when you could have gotten a goose egg but are charged with an earned run instead, with an exemption if you get the last out of the game. Note that this leaves some situations that result in neither goose eggs nor broken eggs, which we’ll say are a “meh.” For instance, if a run scores while you’re in the game but it isn’t charged to you, that’s neither a goose egg or a broken egg; it’s a meh. I’ll speak no more of mehs in this article because they’re pretty boring; when I use the phrase “goose opportunity,” it means a goose egg or a broken egg.

There are usually about three goose eggs for every broken egg, meaning that relievers convert about 75 percent of their goose opportunities. And unlike saves and blown saves, which are highly punitive to guys who aren’t closers, the goose system gives middle relievers a fair shake. For instance, Mark Eichhorn — a good-but-not-great middle reliever for the Blue Jays and other teams in the 1980s and ’90s — converted 76 percent of his lifetime goose opportunities, about the same rate as an average closer.

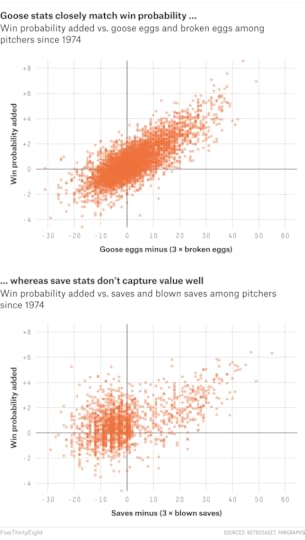

Goose eggs and broken eggs — when taken together — also do a good job of replicating more complicated statistics. For instance, there’s a 0.78 correlation between a simple linear combination of these stats and the highly sophisticated statistic win probability added (WPA), which is arguably the best way to value relief pitchers. WPA is a lot of work to calculate, however, so goose eggs and broken eggs get you to mostly the same place but are relatively simple counting statistics. Saves and blown saves, on the other hand, have a much noisier relationship with WPA (a correlation of 0.50).

But if you take your statistics with an extra helping of rigor — and if you’ve read this far, you probably do — there are a few more things to consider. It’d be nice to adjust performance for a pitcher’s park and league; it was a lot easier to convert goose opportunities at Dodger Stadium in the low-offense 1960s than at Coors Field during the juiced-offense era. We’d also like to know how valuable a late-inning reliever is, which will require some notion of what the replacement level is for the goose statistic. Considering that a lot of high-performing closers — including Rivera — were once middling starters, is the job really that challenging?

To answer those questions, we need to create another new stat: goose wins above replacement (GWAR). To do that, I went back to the history books. Over time, the number of goose opportunities per game has increased (as teams pull their starting pitchers earlier) while the success rate for converting them has varied. The offense-friendly era from 1993 through 2009 was a rough one for relief pitchers, who converted a middling 73.8 percent of their goose opportunities. The best relievers from this era, such as Rivera and Trevor Hoffman, might be slightly underrated without considering this context. But since 2010, which has seen a revival of pitching, the goose-egg conversion rate has improved to 76.5 percent.

YEARS

ERA

AVERAGE GOOSE OPPORTUNITIES PER GAME

CONVERSION RATE

1921-1940

Lively Ball Era

0.28

73.8%

1941-1945

World War II

0.21

77.2

1946-1962

Postwar Era

0.53

75.9

1963-1972

Neo-Deadball Era

0.71

77.5

1973-1992

Balanced Era

0.79

76.3

1993-2009

Juiced Offense Era

0.84

73.8

2010-2016

Strikeout Era

0.92

76.5

Goose opportunities are increasing

Source: Retrosheet

To determine the goose replacement level, I looked at the performance of pitchers since 1996 who made no more than 150 percent of the league’s minimum salary and who were acquired in free agency, on waivers, or through the Rule 5 draft. Essentially, these are the guys who are available to any major league team at any time for next to nothing — the literal definition of replacement-level players. But they actually weren’t too bad in goose situations. They converted 71.5 percent of their goose opportunities during this period, as compared to 74.7 percent for the league as a whole. To put that in more familiar terms, these relievers had a 3.91 ERA, weighted by their number of goose situations, as compared to a 3.64 weighted ERA for the league overall.

Therefore, a team shouldn’t be spending a lot for average relief pitching — the average relievers just aren’t that much better than the replacement-level guys. Pick up a few failed starters off the waiver wire, tell them to limit their repertoire to their two best pitches, and test them out in Triple-A or in low-leverage situations. You won’t necessarily have the next Gossage or Miller — those guys are scarcer and more valuable commodities — but you’ll probably find a couple of pretty good late-inning relievers without paying a lot to do it.

A complete formula for GWAR, which adjusts for a pitcher’s park as well as his league and converts performance in goose situations to wins, can be found in the footnotes.20

The best relievers of all time, according to goose

Even with all this extra work, however, we come to basically the same conclusion that we did before: Most of the best relief seasons came a long time ago, and from pitchers who followed Gossage’s usage pattern rather than Rivera’s.

YEAR

NAME

GOOSE EGGS

BROKEN EGGS

CONV. %

REPLACEMENT-LEVEL CONV. %

GWAR

1965

Stu Miller

79

7

91.9%

75.0%

7.5

1975

Goose Gossage

82

11

88.2

74.3

6.7

1996

Mariano Rivera

54

6

90.0

68.7

6.6

1969

Ron Perranoski

79

13

85.9

72.2

6.6

1996

Troy Percival

47

3

94.0

69.0

6.5

1984

Willie Hernandez

65

7

90.3

73.1

6.4

1980

Doug Corbett

68

10

87.2

71.8

6.3

1967

Ted Abernathy

51

3

94.4

72.5

6.2

1977

Sparky Lyle

66

8

89.2

73.3

6.1

1993

Jeff Montgomery

54

7

88.5

69.5

6.0

2000

Keith Foulke

42

3

93.3

67.7

6.0

1993

John Wetteland

56

6

90.3

71.8

6.0

1970

Lindy McDaniel

70

9

88.6

74.2

5.9

1999

Billy Wagner

44

4

91.7

68.0

5.9

1973

John Hiller

59

7

89.4

72.2

5.9

1972

Tug McGraw

65

6

91.5

75.9

5.8

1963

Dick Radatz

73

11

86.9

73.9

5.7

1988

John Franco

56

5

91.8

73.8

5.7

1979

Aurelio Lopez

54

7

88.5

70.6

5.7

1988

Doug Jones

51

5

91.1

71.6

5.7

1987

Tim Burke

42

2

95.5

70.7

5.7

1977

Bruce Sutter

62

10

86.1

71.1

5.6

1979

Kent Tekulve

71

13

84.5

71.7

5.6

1982

Bill Caudill

65

10

86.7

72.4

5.6

1969

Wayne Granger

59

9

86.8

71.0

5.6

1979

Bruce Sutter

63

11

85.1

70.9

5.5

2002

Eric Gagne

46

3

93.9

72.5

5.5

1983

Dan Quisenberry

60

11

84.5

69.8

5.4

2004

Joe Nathan

41

2

95.3

71.1

5.4

1982

Greg Minton

63

8

88.7

74.1

5.4

2004

Mariano Rivera

47

4

92.2

71.8

5.4

2004

Eric Gagne

46

5

90.2

69.8

5.4

1978

Gene Garber

52

7

88.1

70.5

5.4

2008

Brad Lidge

34

0

100.0

69.5

5.4

1979

Joe Sambito

52

6

89.7

71.8

5.4

1998

Trevor Hoffman

51

5

91.1

72.7

5.4

1955

Ray Narleski

44

2

95.7

73.3

5.4

2016

Zach Britton

40

1

97.6

72.6

5.3

1969

Tug McGraw

46

4

92.0

71.6

5.3

1983

Bob Stanley

70

17

80.5

68.8

5.3

Single-season goose wins above replacement (GWAR) leaderboard, 1930-2016

Plus select seasons since 1921

Sources: Retrosheet, baseball-reference.com

The best relief-pitching season of all time, according to this metric, belongs to Stu Miller, who had 79 goose eggs and just 7 broken eggs for the 1965 Baltimore Orioles. Miller’s traditional numbers looked pretty good that year — he went 14-7 with a 1.89 ERA and 24 saves in 119.1 innings pitched, finishing seventh in American League MVP balloting. His goose stats make it clear that he was almost unhittable in high-leverage situations, however. He contributed 7.5 wins above replacement according to GWAR, which is a Cy Young Award-caliber performance.

After Miller’s 1965 comes Gossage’s 1975, and then there’s a year from Rivera. But Rivera’s best season according to GWAR was not 2004, when he had a league-leading and career-high 53 saves, but 1996, when he was used as a setup man to John Wetteland and had just 5 saves in 107.2 innings of 2.09 ERA relief. Rivera was promoted to closer the next year, but his value declined as the Yankees held him to 71.2 innings despite the success he’d had in the fireman role.

Only two of the top 40 relief seasons have come in the past 10 years. You can be literally almost perfect — as Britton and his 0.54 ERA were last year — and yet still not provide as much value as pitchers like Gossage did because you didn’t have enough volume in high-leverage situations.

The lifetime GWAR leaderboard is somewhat more forgiving to modern closers. Rivera tops the list, with Hoffman second and Gossage third:

NAME

GOOSE EGGS

BROKEN EGGS

CONV. %

REPLACEMENT-LEVEL CONV. %

GWAR

Mariano Rivera

614

108

85.0%

70.5%

54.6

Trevor Hoffman

580

113

83.7

71.6

43.7

Goose Gossage

677

146

82.3

73.1

39.4

Billy Wagner

421

80

84.0

69.8

37.0

John Franco

589

132

81.7

72.0

36.3

Tug McGraw

521

101

83.8

73.0

34.9

Jonathan Papelbon

361

52

87.4

71.7

33.7

Troy Percival

354

64

84.7

69.4

33.3

Hoyt Wilhelm

641

146

81.4

73.8

31.3

Joe Nathan

344

53

86.6

71.9

30.4

Francisco Rodriguez

430

87

83.2

71.9

30.3

Bruce Sutter

557

134

80.6

72.2

30.3

Todd Jones

425

101

80.8

69.7

30.2

Lee Smith

589

156

79.1

71.6

28.9

John Wetteland

307

62

83.2

69.9

25.6

Jeff Reardon

520

130

80.0

72.5

25.4

Rollie Fingers

663

164

80.2

74.3

25.3

Robb Nen

314

60

84.0

71.2

24.8

Stu Miller

405

81

83.3

73.7

24.3

Randy Myers

404

92

81.5

72.2

23.9

Armando Benitez

331

73

81.9

70.7

23.6

Kent Tekulve

517

134

79.4

72.5

23.4

Huston Street

325

63

83.8

72.2

23.3

Roberto Hernandez

404

111

78.4

69.8

23.3

Tom Henke

357

81

81.5

71.4

23.1

Ron Perranoski

444

99

81.8

73.7

22.8

Lindy McDaniel

507

130

79.6

72.9

22.3

Dan Quisenberry

380

87

81.4

72.3

22.1

Jeff Montgomery

360

89

80.2

70.8

21.8

Sparky Lyle

520

130

80.0

73.6

21.6

Dave Giusti

305

54

85.0

73.4

21.5

Dennis Eckersley

352

81

81.3

72.0

20.8

Todd Worrell

350

80

81.4

72.2

20.7

Jose Valverde

252

45

84.8

71.6

20.5

Mike Henneman

306

67

82.0

71.6

20.2

Bob Wickman

344

92

78.9

70.2

19.7

Keith Foulke

263

62

80.9

69.3

19.7

Dave Smith

347

78

81.6

73.0

19.2

Dave Righetti

372

92

80.2

72.2

19.2

Craig Kimbrel

227

34

87.0

73.0

19.0

Career goose wins above replacement (GWAR) leaderboard, 1930-2016

Plus select seasons since 1921

Sources: Retrosheet, baseball-reference.com

So perhaps you can argue that modern closer usage at least helps the best relievers to preserve their longevity, even if it almost certainly doesn’t maximize their value over the course of a given season. Then again, Rivera and Hoffman and Billy Wagner might just have been freaks; there’s been a ton of turnover in the closer ranks lately. Of the top 10 pitchers in saves in 2011, only three were still in the league in 2016, and only one (Craig Kimbrel) was still regularly working as a closer. As long as teams are burning through relief pitchers, they might as well try to get more value out of their best ones.

So how should an ace reliever be used?

Managers have a lot of room for improvement if they forget about saves and use goose eggs as a bullpen guide. A bare-bones workload for a goose-optimized closer would look something like this:

Pitch in all goose situations, including ties, in the ninth inning. For a typical team, that works out to about 40 or 45 innings over the course of the season.

Pitch in goose situations in the eighth inning when his team leads by one run exactly, with the plan of usually also pitching the 9th when the game remains in a goose situation. This will add another 15 innings or so.

Pitch in any goose situations in extra innings, up to a maximum of two total innings pitched for the game. Keep in mind that this will often be impossible because the closer will already have been used earlier in the game. Still, this should amount to another five or 10 innings in a typical season.

That will work out to a total of around 65 innings pitched for the season — about the same number that closers throw now — over roughly 50 appearances. But those innings would come with a super-high leverage index of about 2.5. And the pitcher would go from around 40 or 45 goose opportunities in a season to 60 or 65 instead, potentially generating nearly 50 percent more value as a result.

For an older or injury-prone closer (say, the Los Angeles Angels’ Huston Street), that might be basically all the work they could handle. But there are lot of teams that might want to replicate MiIler’s success, and there are younger, fitter pitchers who could build on this minimal workload. Depending on the day, they could enter in the eighth inning in tie games, for instance. And they could come into the game with runners on, even in the seventh inning; it can be worth using your best reliever to get your team out of a jam in these cases even if you have to remove him from the game later. A pitcher picking up some of these situations might wind up throwing 85 or 90 innings — and a roughly equal number of goose opportunities — over the course of a season in which he makes 60 or 65 appearances. Those pitchers could have roughly double the value that modern closers do. It’s really not that radical a shift from how pitchers are used now.

But it doesn’t have to stop there. Modern teams have about 150 goose opportunities in a season. One day, they’ll find a guy with the right genetics and the right mentality to throw two or three innings every second or third day — someone who really could approach Gossage’s usage pattern — and when that happens, Gossage’s 82-goose-egg single-season record might come under threat. It would be a high bar to clear. But it would be an accomplishment worth chasing down, whereas a save record usually isn’t.

You can download detailed data on goose eggs and broken eggs for all pitchers since 1930 here.

Handicapping The Georgia 6 Special Election

If the polls are right, then Democrat Jon Ossoff will receive by far the most votes in Georgia’s 6th Congressional District, which is holding a special election to replace former U.S. Rep. Tom Price on Tuesday. But Ossoff will probably finish with less than 50 percent of the vote, which would trigger a runoff between him and the next-highest finisher — most likely the Republican Karen Handel, but possibly one of three other Republicans (Bob Gray, Dan Moody Judson Hill) who are closely bunched behind her in polls.

Furthermore, the combined vote for all Republican candidates will probably exceed the combined vote for Ossoff and other Democrats, although it should be close. And the district has historically been Republican-leaning, although it was much less so in the 2016 election than it had been previously. All of this makes for a fairly confusing set of circumstances and a hard-to-forecast outcome.

But we can gain some insight by evaluating the results of past elections to Congress in California, Louisiana and Washington, which follow a similar structure to the Georgia special election. That is to say, they have a first round or nonpartisan blanket primary in which unlimited numbers of candidates from all parties compete against one another, and a second round in which the top two candidates advance to a runoff. This data allows us to come to a handful of broad conclusions:

First, the aggregate party margin — whether Democrats or Republicans receive more votes overall — indeed has some predictive power for forecasting runoff results. It’s a useful thing to look at.

But so does the top-two margin — that is, which candidate wins the first round, and by how much.

Of these measures, the aggregate party margin is somewhat more predictive. But when there’s a split between them — say, the Democrat is the top finisher but Republicans win the aggregate vote — the runoff could usually go either way.

The runoff often winds up being a lot different than what you might expect from the first round, as the dynamics of a multiway race and a two-way race aren’t that similar to one another. Uncertainty is inherently fairly high.

Metrics such as the overall partisanship of a district — as measured by its relative presidential margin, for instance (how it votes for president as compared to the rest of the country) — may be more predictive of runoff outcomes than the first-round results.

Apply these principles to the Georgia 6 race, and you’ll conclude that Tuesday night’s first round won’t actually resolve that much — unless Ossoff hits 50 percent of the vote and averts the runoff entirely. (That’s an unlikely but hardly impossible scenario given the fairly high error margins of polls under these circumstances.) Even if Ossoff finishes in the low 40s, it will be hard to rule him out in the second round provided that he still finishes in first place by a comfortable margin. But even if Ossoff finishes just a point or two shy of 50 percent, and Democrats finish with more votes than Republicans overall, he won’t have any guarantees in the runoff given that it’s a Republican-leaning district and that the GOP will have a chance to regroup. With the runoff not scheduled until June 20, there will be lots of time for speculation about what the first round meant — and a lot of it will be hot air.

While I’ve already given away the conclusion, let’s walk through the evidence in a bit more detail. First, here’s where polls have the race, using an average of the most recent surveys from SurveyUSA, Opinion Savvy, Landmark Communications, Lake Research Partners, Meeting Street Research, Revily, Red Racing Horses and Clout Research, with undecideds allocated proportionately among the candidates.

CANDIDATE

DEMOCRATS

REPUBLICANS

Jon Ossoff

46

Karen Handel

18

Bob Gray

13

Dan Moody

9

Judson Hill

9

Ron Slotin

1

David Abroms

1

Other Republicans

1

Other Democrats

1

Total by party

48

51

Ossoff has a big lead, but Democrats are under 50 percent

Average of recent polls from SurveyUSA, Opinion Savvy, Landmark Communications, Lake Research Partners, Meeting Street Research, Revily, Red Racing Horses and Clout Research, with undecideds allocated proportionately.

Ossoff has polled at a raw 42 percent on average between these polls, but he gets up to 46 percent given his portion of the undecided vote. Handel is the top Republican, at 18 percent after allocating undecideds, with Gray following her at 13 percent. Republicans combined have 51 percent of the vote, however, whereas Democrats have 48 percent.

If Tuesday’s results wound up exactly like this — with Republicans winning the aggregate party vote by 3 percentage points, but Ossoff winning the top-two margin by 28 points over Handel — then what would the outlook be for the second round?

With help from my colleague Aaron Bycoffe, I found 181 elections to Congress (either the House or the Senate) since 2008 in California, Louisiana and Washington, which used the two-stage format and in which a Republican squared off against a Democrat in the runoff. Then I ran a regression to predict the runoff margin based on the aggregate party margin and the top-two margin. It came up with the following formula:

Runoff margin = .66 * Aggregate party margin + .22 * Top-two margin

Note that the coefficient is larger on the aggregate party margin than top-two margin — that’s the regression’s way of saying that the aggregate party margin is the more important indicator. However, the top-two margin — that is, who actually won the first round — shouldn’t be overlooked. Out of 21 races in our database where a candidate won the plurality in the first round but her party lost the aggregate party vote, the candidate nevertheless won the runoff 11 times. For instance, Republicans combined got more of the vote in Washington’s U.S. Senate primary in 2010, but Democratic incumbent Patty Murray got the plurality of the vote. Murray went on to win the second round over Republican Dino Rossi.

Plugging Ossoff’s numbers into the formula above, we come up with a projection that he’d win the runoff by 4 percentage points. So that sounds pretty good for him, right? Well, yes … it would be pretty good. But not more than pretty good, because he has some other things to worry about. For one thing, the margin of error in the calculation is quite high. Specifically, it’s about 8 percentage points for projecting one candidate’s vote share in the runoff, or 16 percentage points (!) for projecting the margin between the candidates. First-round results only tell you so much in these cases.

And then there’s the partisanship of the district to consider. In Louisiana’s Senate election in 2014, Democratic incumbent Mary Landrieu received 42 percent of the vote in the first round, a plurality. But she improved only to 44 percent in the runoff, easily losing to Republican Bill Cassidy. There just weren’t enough Democratic votes to go around in Louisiana. Could Ossoff suffer from a similar problem?

Perhaps, but the partisanship of Georgia’s 6th District is hard to gauge. Former Republican speaker Newt Gingrich represented the district for 20 years. And in 2012, it voted for Mitt Romney by 23 percentage points, according to data compiled by Daily Kos Elections. But last year, it chose Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by less than 2 percentage points. Like other well-educated, Sunbelt suburbs, it was one of the bright spots for Democrats in what was otherwise a tough election.

Because of this ambiguity, the results in Georgia 6 are going to be hard to benchmark. An Ossoff win would unambiguously be good news for Democrats. But a narrow loss could be anywhere from disappointing to encouraging for them, depending on the margin and whether you think 2016 represented the new normal in the district. If judged by its 2012 results, merely coming within single digits in Georgia 6 would count as a decent result for Democrats, as was the case in a special election in the Kansas’s 4th Congressional District last week. If we’re going by 2016, by contrast, Democrats ought to be competitive in the district as a matter of course — and they should be winning their fair share of races there when the national climate is even moderately Democratic leaning.

To measure district partisanship at FiveThirtyEight, we use the past two presidential elections, but weight them 75-25 in favor of the most recent election. We also compare the district to how the country voted overall, instead of looking at its raw vote totals. By our formula, Georgia 6 comes out as an R +10 district, meaning that it’s a net of 10 points more Republican than the country as a whole. (That is, in an election where the Republican and Democratic candidates tied in the national popular vote, you’d expect the Republican to win by 10 point in Georgia 6). That’s the sort of district that wouldn’t be competitive in a neutral year, but could easily become competitive if the national environment were friendly to Democrats.

If it seems like I’ve taken a lot of time to parse this district’s partisanship, that’s because it matters quite a lot for forecasting purposes. If you test a district’s presidential margin in the runoff elections I described above, it turns out to be more important than either the aggregate party margin or the top-two margin from the first round of voting. Put another way, these nonpartisan primaries can be weird — parties and voters sometimes face counterintuitive tactical choices — and therefore they may not be that informative. But in an environment when congressional and presidential voting are increasingly correlated, the long-term partisanship of a district can tell you a lot.

To get back to Georgia 6, we can now use the following formula to project the runoff results:

Runoff margin = .53 * Relative presidential margin + .35 * Aggregate party margin + .19 * Top-two margin

As I mentioned, the relative presidential margin is Republican +10 in the district. And Republicans project to win the aggregate party margin by 3 points on Tuesday. But Ossoff projects to win the top-two margin by 28 points. Apply the formula, and it shows a photo-finish for the runoff, with the Republican projected to win by 1 percentage point — effectively a toss-up given the formula’s high margin of error.

We’re almost getting to the point where this has turned into (gulp) a model rather than just a quick-and-dirty way to take the pulse of the race. And if this were a full-fledged model, there are a couple of other things we’d want to consider. For one thing, it’s probably safe to conclude that we’re in a somewhat Democratic-leaning environment right now, given Trump’s poor approval ratings, a modest Democratic advantage on the generic congressional ballot and the results of last week’s special election in Kansas. That should mitigate some of Georgia 6’s Republican lean. For another thing, a couple of polls, such as this one, have tested prospective runoff matchups, and they’ve usually shown Ossoff a percentage point or two ahead of Handel and other Republicans. It’s not much of a “lead,” but it suggests that a runoff might at least be a toss-up for him.

As of Sunday evening, betting markets gave Ossoff about a 40 percent chance of eventually being the next member of Congress from Georgia 6, whether by winning a majority of the vote on Tuesday or prevailing in the June runoff. While that isn’t a ridiculous assessment, it looks too pessimistic on Ossoff. If the polls are right, the outcome of a runoff is more like a true 50-50 proposition — plus, there’s an outside chance that Ossoff could win outright on Tuesday. We’ll have a better sense for the odds after Tuesday, although perhaps not that much better given the uncertainties I described above.

But I generally think the conventional wisdom has been too slow to catch up with the fact that midterm and off-year elections are often problematic for the president’s party, and especially when the president is as unpopular as Trump. What might seem like an extraordinary feat — Democrats flipping Gingrich’s old seat — is going to be more commonplace in an environment like this one.

April 12, 2017

What Do We Know About The 2018 Midterms Right Now?

In this week’s politics chat, we look ahead to the 2018 midterm elections. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Greetings, everyone. Our question for today: What do we know about the 2018 midterms right now? What metrics/trends/things should 2018 enthusiasts be looking at?

So, first up: How would you describe the political environment right now? (And does that even matter for what happens in a year and a half?)

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Cloudy with a chance of landslide. An anti-Trump/GOP landslide, that is.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): President Trump’s approval numbers, at least right now, are bad. George W. Bush in 2006 or Barack Obama 2014 bad. That is not good for Republicans.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Yeah, the environment is not Republican friendly. It often isn’t friendly to the president’s party in the lead up to a midterm, but this is really bad. The president’s approval rating is just 41 percent. That’s the worst ever at this point in a presidency. Then there’s the generic ballot; an average of the generic ballot polls so far has the Republican Party down 6 percentage points. That’s the worst ever for the majority party in Congress at this point.

Now, does that matter? Things shift, but it’s certainly a poor starting position for the GOP.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): God I want to say something contrarian here. But I don’t think I can, really, given, ya know, reality.

natesilver: Contrarianism isn’t allowed here at FiveThirtyEight, Clare.

micah: Says the uber-contrarian.

perry: The counter, I think, is the map. Lots of Senate seats in red states are up in 2018. Lots of House races in districts that were conservative leaning pre-Trump.

micah: OK, but what about the second half of my question? I assume a lot can change before November 2018.

natesilver: I guess the way I see it is this: My prior is that a midterm is usually quite bad for the president’s party. So the default is that Republicans fighting an uphill battle. You could make an argument that we don’t have that much reason to deviate from the default yet. But the default is still pretty bad.

clare.malone: It also depends on whether or not there are sustained efforts among Democrats at the state level to make sure their voters turn out, especially post-health care battle. That issue was a big thing for people to rally around. Democrats are trying to make the whole “make Trump release his taxes” thing happen this weekend, but I think they’re going to have to find other offensive (as opposed to defensive) strategies to keep the base active.

harry: This is not for this year, but we know from the past that, if anything, the generic ballot tends to move against the party in power in the year running up to the midterms. So just talking about the fundamentals, the environment may actually get worse for Republicans.

natesilver: And obviously Perry is right that the Senate map isn’t very friendly to Democrats, but that’s different from the political environment per se. If you had a Republican-leaning environment at the midterms, maybe the GOP would gain six or seven Senate seats given the map. In the Democratic-tinged environment we’ll probably have, however, maybe they’ll just break even. That’s still a huge difference.

perry: Can the environment change? Trump could get more popular. I think?

clare.malone: For sure.

natesilver: There are two opposing forces here: On the one hand, presidents tend to get less popular over time. On the other hand, they tend to revert to the mean so, e.g., very unpopular presidents might be more likely than not to rebound at some point. Right now — because Trump’s approval ratings are already so low — I think it’s reasonable to assume his numbers are about equally likely to fall further or to rebound some.

Although, that assessment doesn’t consider any circumstances pertinent to Trump in particular. It just says “given a president with a 40 percent approval rating 80 days into his term, what would you expect his approval rating to be in six months”? And the answer is probably about 40 percent, but with a huge margin of error around that.

If Trump’s in some sort of death spiral because he’s overmatched for the job, you could argue the case for its being lower. But to some extent, we’re out on a limb because no president has been so unpopular so soon into his term.

perry: Clare hinted at what I think is an interesting question about the Democrats. We are seeing really strong activism, but that is different than midterm turnout. The activism could predict higher turnout. Or not.

clare.malone: Right … they still don’t have a message besides “Trump bad.”

natesilver: At the midterms, I’m more likely to take signs of activism/energy seriously than I would for a presidential general election.

micah: So in terms of whether the political winds stay blowing in Democrats’ favor or swing around towards the GOP, does it all basically come down to Trump? Or does it somewhat depend on what Democrats do?

To Clare’s point, this Democratic tax day thing seems a bit weak sauce to me.

clare.malone: A lot of it is on Democrats, IMO. It doesn’t seem that Trump can get much less popular unless something breaks with Russia or he drowns a kitten on live TV or something. It seems more likely that he stays the same or gets a little more popular because people find what he’s doing relatively harmless or they get used to Trump talk.

natesilver: I want to contradict your contrarianism, Clare. There are lots of ways that Trump could get less popular. If his supporters feel like he’s not delivering on his promises, that’s a big risk. And remember, his favorability rating has been in the 35 percent range at points in the past, so — although comparing approval and favorability numbers is slightly apples-to-oranges — he isn’t even at the low end of his own historical range.

harry: Enthusiasm about who people were supporting was a big leading indicator of Republican success in 1994, 2010, and 2014. Same for Democrats in 2006. So I’m big on enthusiasm in midterms.

clare.malone: What’s Trump’s lowest range? I’d like to be able to fathom the depths!

natesilver: He had a 35 percent favorability rating for long stretches of the 2016 election. And actually bottomed out toward 30 percent when he was having problems with his fellow Republicans last spring.

harry: But I’m less sure about Trump’s individual numbers. I know what they mean now, but those can move around. That’s why I’m also interested in congressional numbers like the generic ballot. Why look to the wheat when you can look to the pasta, if you catch my drift.

natesilver: I have no idea what you mean.

clare.malone: “Look into the pasta”?

micah: Harry, please go sit in the corner.

natesilver: “Why look to the wheat when you can look to the pasta.”

clare.malone: Is that like, “read the tea leaves”? Except wack.

micah: Except it doesn’t make any sense whatsoever.

Anyway, let’s keep going on my “how much does it matter what Democrats do?” question a little more.

perry: I would frame the Democrats’ question this way: The people at the town halls will vote. But that is not a majority in most districts. What happens to black turnout? Latino turnout? Turnout among people who often drop off at midterms even if they voted in the presidential election? Turnout of people under 35? Those are important questions. I don’t know the demographics of the town hall attendees, but the pictures are often of older, white women.

clare.malone: But maybe not the white women they need…

micah: So maybe Democrats should be spending all their time readying their GOTV operation and sorta trust that the anti-Trump passion will take care of itself?

clare.malone: See, this is the problem with the Democrats’ resistance messaging if it doesn’t shift a little pre-midterms: They risk alienating all those people who are on the margins, who might have voted for Trump but have regrets. They still haven’t landed squarely on an economic message. They’re still prosecuting the “unfit for office” line. No one wants to hear that after a while. Negativity wears.

Yeah, if you hate Trump, you’re gonna hate him in a year.

You gotta persuade now.

perry: I think a totally negative message, no real vision, can work in a midterm. But it does require your base to vote.

natesilver: I think negative can work, too. But it can be a mix of negative message against Trump and a negative message against the Republican Party — and maybe also a negative message against incumbency/“the system” — depending on the state or district.

harry: We’re dealing with a very small subset of House elections off of which we think Republicans have a turnout advantage in midterms. Go back to 2006 and it disappears. That was the year with bigly Democratic enthusiasm (as I showed above). I’m also not convinced the midterm gap is that large. You see that in Patrick Ruffini’s numbers in Pennsylvania. Let’s put it this way, if Democrats hold a 9 percentage point advantage on the generic ballot as Marist recently found, then they’re going to make big gains. So I think it’s more about persuasion than about turnout, but both are important. I’ll also add that the onus is less on the Democrats than in a presidential election. That’s a choice. This is a referendum on the party in power.

perry: Interesting.

natesilver: Go hard anti-Trump in suburban, Sunbelt districts such as Georgia 6, hard anti-Paul Ryan in some of the Midwestern districts that have flipped to the GOP, hard anti-establishment out West, and you can put a fair number of districts in play.

perry: You guys are saying most of the districts they need to flip are not full of very liberal constituencies anyway?

clare.malone: Not Sunbelt suburbs, necessarily.

micah: That’s why the all-negative strategy doesn’t make sense to me. They need to flip GOP/Trump-won districts.

harry: Yes, but remember if Trump is unpopular, then he’ll be underwater in those districts, too.

clare.malone: I will also point out here that a fair number of competitive districts are in California. Which can have interesting Sunbelt-esque characteristics in certain parts.

natesilver: People aren’t voting for a Democratic agenda, though. Because Democrats can’t really get anything done as long as Trump’s in the White House*. So in some sense, it’s more honest and accurate to say “we’re running as a check on Paul Ryan and Donald Trump.”

*Unless Trump actually tries to bargain with Democrats, which could be interesting.

micah: OK, what else should 2018 watchers be looking at? Candidate recruitment?

harry: Candidate recruitment and retirements.

clare.malone: Orrrrrriinnnnnnnnnnn!

Orrin Hatch might retire (he gave what I read to be a soft “I will run”), in which case we might see the resurrection of Mitt Romney and that would be totally fascinating to have him on the national scene.

perry: Democrats say people are coming out of the woodwork to run. Question is 1. fundraising. Everyone is not going to raise Jon Ossoff money. 2. Candidate recruitment. I would say this might be more important on the Republican side, in Senate races, if they are trying to knock off Joe Manchin or Claire McCaskill. The numbers are potentially there. Are the candidates?

clare.malone: Not that I know of?

harry: In Missouri, maybe. Republicans will have a strong candidate in Ann Wagner to take on McCaskill.

clare.malone: It’ll be interesting to see if the small-dollar fundraising goes places with any candidates — Our Revolution, the Bernie Sanders-associated PAC might try to make moves on that.

natesilver: By the way, this is how the Kansas and Georgia special elections matter a lot, too. If Democrats were to win one of those — or, I guess, make it a photo finish in Kansas — you’re going to see a HUGE boost in recruitment, and also perhaps a fair number of GOP retirements.

micah: FYI for readers: We’re chatting late on Tuesday, before the results from Kansas 4 are finalized. [Editor note: Republican Ron Estes won, but not by much.]

perry: That is a good point. Candidates are looking for signs this is a good environment. Basically everyone Democrats wanted to run in 2006 eventually did, as it became clear it was a good time to run.

Our assumption in this conversation is the House is the story. That Democrats are more likely to gain the majority there than the GOP is likely to get 60 seats in the Senate, which would also be huge. Is that assumption correct?

micah: I think that’s correct.

harry: If there was a Democratic president there’d be a good shot for Republicans to get to 60. I could see them getting to 56 seats in a good year under Trump. But 60 seems hard. They’d have to go and win a number of purple seats. A poll just out from Virginia has Tim Kaine up by 20+ percentage points over possible Republican opponents.

natesilver: Republicans aren’t gonna get 60 seats — or even come close — unless there’s a Sept. 11-like event that makes Trump super popular. They’re more likely to lose the Senate than to get 60 seats, IMO.

And much more likely to lose the House.

perry: That is what I think, too. But Trump and his team were talking about winning 60 Senate seats maybe two months ago, before the travel ban and health care debacles.

micah: OK, so what else is there to pay attention to?

natesilver: Governor’s races obvs. Including the one in Virginia this year.

clare.malone: That seems likely to go Democratic, at this point. Both Democrats — Tom Perriello and Ralph Northam — are polling better than Ed Gillespie, the Republican.

perry: Interesting. Gillespie is as un-Trump as you can get.

harry: The latest Quinnipiac poll has the Democrats up around 10 percentage points.

natesilver: Could Perriello be a 2020 candidate, though?

harry: Doug Wilder tried to run in 1992 after winning Virginia’s governor’s race in 1989, so it’s not crazy.

clare.malone: I mean, what are you gonna do with yourself after just one term?

Lotsa excess energy to expend.

perry: In 2018, I think you have several GOP governors in big states who are term-limited. That gives Democrats an opportunity.

micah: Yeah, overall the governors map is basically the inverse of the Senate map, right?

harry: Lots of Republican governors up for re-election or term-limited, though the correlation between the national environment and governor races is less clear than for federal elections.

micah: Clare, did Perriello seem like presidential material to you? Maybe not in 2020, but someday?

perry: Donald Trump is president.

micah: lol. Fair point.

clare.malone: He’s certainly a smart, ambitious guy. Has lived overseas (foreign policy plaudits.) I’m sure the thought of running for president has crossed his mind, if not uttered in private.

perry: I guess the question I would be curious about: Is there a Democratic governor who if he or she won re-election in 2018 would be a 2020 contender?

micah:

I.

love.

this.

game.

perry: I can’t think of one. This is perhaps a weakness of the party.

clare.malone: What about senator? Sherrod Brown used to get mentioned for things. He might be too old? I don’t know anymore.

perry: I missed that Micah was being sarcastic!

micah: I wasn’t!

clare.malone: Micah’s a sick, twisted dude, Perry.

perry: Brown is up in 2018, so are Amy Klobuchar and Christopher Murphy, so they can’t do all of the presidential hinting I think they would do otherwise

harry: I’d say the only governor who could potentially be popular with the base whose seat is up in 2018 is John Hickenlooper in Colorado, but he’s term-limited.

clare.malone: Right, if Brown lost, would he run?

natesilver: There’s nothing wrong with 2020 speculation, just like there’s nothing wrong with having a beer on a Sunday afternoon.

micah: I hate the “it’s too soon” act political reporters do. For one, they f*cking love talking about this stuff — why pretend otherwise? Secondly, Trump aside, running for president takes a lot of prep work. The contenders don’t think it’s too soon.

micah: OK, let’s close out with the special elections.

We’re chatting about this before the Kansas 4 results come in, but I’ve never seen U.S. House special elections get so much attention!

natesilver: Apparently you don’t remember Dede Scozzafava in 2009.

These things always get a fair amount of attention. You could have a good argument about whether it’s too much attention or too little.

perry: These races are important, for two reasons. 1. Every seat matters and winning Georgia 6 gets Democrats one seat closer. 2. As Nate said, wins/close losses could motivate the Democrats’ base to get even more involved. But if Ossoff loses, that may be a problem for Democrats. All of this hype, and nothing.

harry: Special elections in the whole can be predictive. That is, if Democrats outperform what we expect across many races, then that’s a good sign for Democrats. What we don’t want to do is look at individual results and draw big conclusions.

I’m also not looking at wins and losses. I’m looking at the margin relative to the presidential lean.

What I'll be keeping an eye on in upcoming special elections. Started with CA-34 last week and continues with KS-04 this week. pic.twitter.com/tNZwG51uoY

— (((Harry Enten))) (@ForecasterEnten) April 9, 2017

If Republicans start seeing that Democrats are doing well compared to the presidential lean across the board, it could hurt their recruiting.

natesilver: I do wonder if expectations have changed to the point where even a narrow win in Georgia 6 would be taken as an OK sign for Republicans. And, yeah, expectations are dumb — they’re basically just another word for media spin — but to the extent Georgia 6 could affect something like candidate recruitment, the narrative coming out of the race could matter.

harry: Yeah, I think that’s where binary win/loss can matter, is recruitment. And expectations have gotten crazy in Georgia 6. There hasn’t been a single poll that has Ossoff close to getting the 50 percent necessary to avoid a runoff.

clare.malone: It’s just a place for people to expend their excess energy, I think (Georgia 6). That’s part of the phenom.

micah: I think that’s right.

Since this chat will publish after the Kansas results are in, anyone bold enough to make predictions now?

Bueller?

You’re all chickens. I’ll say R +14.

clare.malone: Someone will make a “What’s the Matter With Kansas?” headline pun.

perry: I literally know nothing about this race except for what I read in Harry’s story. Republican by 16.

natesilver: R+9.

micah: “Nate Silver Predicted Close Race In Kansas House Election”

natesilver: Oh please stop, Micah.

perry: Lol. Can I tweet that? #dontgetfired

micah: Haha.

clare.malone: Nate, I hear you’re endorsing Jon Ossoff, right?

micah: I heard that, too.

OK, closing thoughts?

natesilver: Closing thought: My experience has been that people don’t adjust their expectations quickly enough to how bad the midterm/off-year environment usually is for the president’s party. They certainly didn’t in 2014, 2010, 2006.

So, yes, there are absolutely some reasons for skepticism in terms of how many gains Democrats could make. They face a problematic map, Trump could get more popular, #theresistance could turn out to have more bark than bite, etc. But I think people are forgetting how rough these things usually are for the president’s party. The modal case at this point is that the House gets very interesting, Democrats pick up several governor’s seats, and the Senate is maybe a wash (because only because of the GOP’s very favorable map). That’s the default.

So I’m looking for evidence to deviate from the default. A close race in Georgia 6 would actually be pretty consistent with the default. A close race in Kansas 4, on the other hand, would be more genuinely surprising and would suggest that Democrats had a lot of upside.

April 10, 2017

Are The Cavs Overrated Or Underrated?

The Cleveland Cavaliers haven’t been any good lately. And I don’t just mean their loss Sunday against the Atlanta Hawks, in which they became only the third team in NBA history to blow a 26-point fourth-quarter lead. They’re 12-13 since the All-Star break. They have one of the NBA’s worst defenses, having allowed 107.9 points per 100 possessions — in the same territory as the Orlando Magic and the New York Knicks. They haven’t won a road game against a Western Conference playoff team all season. But handicappers think LeBron James and company have a pretty good chance of winning their second-straight NBA title anyway.

Their view depends on their belief in the existence of Playoff LeBron, a superhero that transcends his already-formidable regular season form to carry his team to ever-greater heights. The good news for Cavs’ fans is that Playoff LeBron exists. He just might not be mighty enough to drag this team to a title.

On the basis of their regular-season record and point differential, this season’s Cavs have been in the same general vicinity as teams such as the Boston Celtics, Toronto Raptors and Utah Jazz. Those teams are variously 30-to-1 to 100-to-1 longshots to win the title, according to Vegas bookmakers. But the Cavs are nonetheless the second-favorite team to win the championship, with a 20 to 25 percent chance according to bookmakers.

Computer systems disagree. All of them have the Warriors as odds-on favorites to win the title, with the San Antonio Spurs as the next-best bet, and the Cavs as part of an undistinguished mass of teams beneath them. ESPN’s BPI puts Cleveland’s chances at just 4 percent. Basketball-Reference’s playoff odds also have them at 4 percent. And FiveThirtyEight’s Elo-based ratings, which heavily weight recent play, have them even lower at just 2 percent.

Usually, Elo-type ratings mimic betting markets fairly well. We give the Warriors a 65 percent chance of winning the title, for instance, and the San Antonio Spurs an 11 percent chance — right in line with where markets have them. So what accounts for the huge difference on Cleveland?

One explanation is that this is all just sort of irrational: the Cavs are a marquee team and bettors just can’t stomach the idea that they’re just the Raptors with better uniforms. But I’m not sure I totally buy that; NBA betting markets are usually fairly sharp.

Instead, bettors expect the Cavs to find a higher gear in the postseason. This isn’t an idea they just came up with; it was already priced into their assessment of the Cavs before the year began. At the start of the NBA season, FiveThirtyEight’s projections forecast the Cavs to win 57 regular-season games. (They have 51 now, so they’ll finish with no more than 53 wins.) That forecast was almost the same as what Vegas gave them, which put their over-under at 56.5 wins. But we also gave the Cavs only an 11 percent chance of winning the title whereas Vegas put them at 5-to-2 against, or a 29 percent chance. In other words, handicappers and the computer models agree on “regular-season Cavs.” It’s just that Vegas thinks that “playoff Cavs” are different — and much better — whereas our Elo ratings make no such distinction.

But is there good reason to think that Cleveland can turn it up a notch?

It’s not hard to recall examples of defending champions that lollygagged their way through the regular season, only to show up as the best version of themselves in the playoffs. In 2000-01, Shaquille O’Neal, Kobe Bryant and the Los Angeles Lakers finished with a 56-26 record — better than the Cavs this year, but not by that much — before winning 15 of 16 playoff games and repeating as NBA champion. And Hakeem Olajuwon and the 1994-95 Houston Rockets finished at 47-35 before winning the title despite being the No. 6 seed. In his last season in Miami, James and the 2013-14 Miami Heat had an uninspired regular season, going 54-28. But they made the NBA finals before losing to San Antonio.

I’ve done a bit of cherry-picking there, however. Overall, it’s not clear if defending champs overperform by much in the playoffs. In the table below, I’ve looked at every defending NBA champion since the ABA-NBA merger in 1976-77. If the “higher gear” theory is correct, then they should systematically beat Elo’s expectations in the postseason, in which case their Elo ratings will rise over the course of the playoffs. On average, however, these teams’ Elo ratings increased only from 1644 to 1658 during the playoffs. So there’s a little something there, but in Elo terms, that’s pretty minor — not much more than a rounding error.

ELO RATING IN PLAYOFFS

YEAR

TEAM

RECORD

POINT DIFF.

PLAYOFFS

START

END

DIFF.

2017

Cavaliers

51-29

+3.2

TBD

1566

TBD

TBD

2016

Warriors

73-9

+10.4

Lost NBA Finals

1788

1756

-32

2015

Spurs

55-27

+6.3

Lost 1st Round

1733

1721

-12

2014

Heat

54-28

+4.2

Lost Finals

1581

1604

+23

2013

Heat

66-16

+7.0

Won Title

1757

1754

-3

2012

Mavericks

36-30

+1.8

Lost 1st Round

1547

1525

-22

2011

Lakers

57-25

+6.0

Lost 2nd Round

1659

1624

-35

2010

Lakers

57-25

+4.8

Won Title

1613

1695

+82

2009

Celtics

62-20

+7.4

Lost 2nd Round

1693

1653

-40

2008

Spurs

56-26

+5.1

Lost Conf. Finals

1662

1678

+16

2007

Heat

44-38

-1.2

Lost 1st Round

1505

1479

-26

2006

Spurs

63-19

+6.7

Lost 2nd Round

1685

1675

-10

2005

Pistons

54-28

+3.3

Lost NBA Finals

1613

1689

+76

2004

Spurs

57-25

+7.5

Lost 2nd Round

1734

1719

-15

2003

Lakers

50-32

+2.7

Lost 2nd Round

1655

1651

-4

2002

Lakers

58-24

+7.2

Won Title

1676

1738

+62

2001

Lakers

56-26

+3.7

Won Title

1647

1779

+132

2000

Spurs

53-29

+5.9

Lost 1st Round

1637

1625

-12

1999

Bulls

13-37

-8.6

Missed playoffs

1355

—

—

1998

Bulls

62-20

+7.2

Won Title

1728

1785

+57

1997

Bulls

69-13

+10.7

Won Title

1766

1802

+36

1996

Rockets

48-34

+1.6

Lost 2nd Round

1485

1497

+12

1995

Rockets

47-35

+2.3

Won Title

1531

1665

+134

1994

Bulls

55-27

+2.9

Lost 2nd Round

1575

1607

+32

1993

Bulls

57-25

+6.2

Won Title

1679

1726

+47

1992

Bulls

67-15

+10.1

Won Title

1769

1762

-7

1991

Pistons

50-32

+3.1

Lost Conf. Finals

1552

1535

-17

1990

Pistons

59-23

+5.4

Won Title

1666

1716

+50

1989

Lakers

57-25

+6.4

Lost NBA Finals

1637

1677

+40

1988

Lakers

62-20

+4.8

Won Title

1643

1662

+19

1987

Celtics

59-23

+6.6

Lost NBA Finals

1676

1659

-17

1986

Lakers

62-20

+6.8

Lost Conf. Finals

1652

1647

-5

1985

Celtics

63-19

+6.5

Lost NBA Finals

1668

1685

+17

1984

76ers

52-30

+2.4

Lost 1st Round

1587

1572

-15

1983

Lakers

58-24

+5.1

Lost Finals

1605

1606

+1

1982

Celtics

63-19

+6.4

Lost Conf. Finals

1686

1703

+17

1981

Lakers

54-28

+3.3

Lost 1st Round

1610

1595

-15

1980

SuperSonics

56-26

+4.2

Lost 2nd Round

1639

1614

-25

1979

Bullets

54-28

+4.8

Lost Finals

1581

1554

-27

1978

Trail Blazers

58-24

+5.9

Lost 1st Round

1558

1551

-7

Average*

1644

1658

+15

How defending NBA champions fared the next season

* Average excludes 1999 Bulls and 2017 Cavaliers

Source: Basketball-reference.com

Forget looking at defending champions, though. The more important variable, as far as sports bettors are probably concerned, is LeBron. Between his experience, his toughness, and his ability to thrive in crunch-time situations, he has a game well tailored to the playoffs. And that shows up in the data:

ELO RATING IN PLAYOFFS

YEAR

TEAM

RECORD

POINT DIFF.

PLAYOFFS

START

END

DIFF.

2017

Cavaliers

51-29

+3.4

TBD

1566

TBD

TBD

2016

Cavaliers

57-25

+6.0

Won Title

1642

1759

+117

2015

Cavaliers

53-29

+4.4

Lost Finals

1631

1692

+61

2014

Heat

54-28

+4.8

Lost Finals

1581

1604

+23

2013

Heat

66-16

+7.9

Won Title

1757

1754

-3

2012

Heat

46-20

+6.4

Won Title

1613

1712

+99

2011

Heat

58-24

+7.5

Lost Finals

1672

1702

+30

2010

Cavaliers

61-21

+6.5

Lost 2nd Round

1701

1646

-55

2009

Cavaliers

66-16

+8.9

Lost Conf. Finals

1725

1742

+17

2008

Cavaliers

45-37

-0.3

Lost 2nd Round

1506

1562

+56

2007

Cavaliers

50-32

+3.9

Lost Finals

1598

1621

+23

2006

Cavaliers

50-32

+2.2

Lost 2nd Round

1562

1564

+2

Average*

1635

1669

+34

LeBron James’s teams usually find a higher gear in the playoffs

* Average excludes 2017 Cavaliers.

Source: Basketball-reference.com