Nate Silver's Blog, page 102

June 19, 2017

Why The Georgia Special Election Matters

The “takes” you’ll read about the special election in Georgia’s 6th Congressional District on Tuesday night are probably going to be dumb. A close outcome in either direction would be consistent with what we know about the political environment. So if either Democrat Jon Ossoff or Republican Karen Handel wins narrowly, it will be portrayed as a more important predictive signal than it really is. A blowout result would be a bigger deal. But even then, Georgia 6 is a slightly unusual district, and the election would be one data point among many. Georgia isn’t even the only special election on Tuesday; South Carolina’s 5th Congressional District is holding one also.

Here’s the thing, though: Sometimes dumb things matter if everyone agrees that they matter. Congressional Republicans could use a signal of any kind right now to coordinate their strategy around two vexing issues: first, their health care bill, and second, their behavior toward President Trump and the investigations surrounding him. Whatever direction Republicans take on these questions, they will find some degree of strength in numbers. Republicans would probably be less afraid of publicly rebuking Trump, for instance — and becoming the subject of a @realDonaldTrump tweetstorm or Trump-backed primary challenge — if other GOPers were doing the same.

The Georgia 6 outcome might trigger some herd behavior among Republicans, therefore, changing the political environment in the weeks and months ahead. A loss for Handel would probably be interpreted by the GOP as a sign that the status quo wasn’t working. If even a few members of Congress began taking the exit ramp on Trump and the American Health Care Act, a number of others might follow. A win, conversely, would have a morale-boosting effect; Republicans would probably tell themselves that they could preserve their congressional majorities by turning out their base, even if some swing voters had abandoned them.

Georgia 6 is a tough district to diagnose because its politics in presidential elections shifted a lot from 2012 to 2016. In 2012, the district went for Mitt Romney by 23 percentage points in an election that then-President Barack Obama won by 4 points nationally. That made it 27 points more Republican than the country as a whole. In 2016, by contrast, it chose Trump over Hillary Clinton by only 1.5 points in an election where Clinton won the popular vote by about 2 points nationally. Therefore, it was only 3 to 4 points more Republican than the national average.

If one uses the 2016 presidential election as a benchmark, this is a race that Democrats should be winning. They currently lead in the generic congressional ballot by about 7 percentage points, which ought to be enough for Ossoff to overcome the district’s modest GOP lean from 2016. By contrast, if one takes 2012 as the benchmark in the district, then even coming within single digits of Handel would represent a massive overperformance for Ossoff.

FiveThirtyEight’s usual procedure — what has produced the best predictions in past elections — is to combine the past two presidential cycles in a 3-1 ratio. That is to say, we’d take three parts from 2016, when the district was only slightly red-leaning, and one part from 2012, when it overwhelmingly backed Romney. By that formula, Georgia 6 is 9.5 points more Republican than the country as a whole. According to the generic ballot, the current political environment isn’t quite Democratic enough to overcome a 9.5-point deficit, so you’d expect Handel to win, although narrowly. (The table here describes a number of methods for projecting the Georgia 6 result, which I’ll explain further below. The one I just mentioned — taking a blend of recent presidential results and adjusting it based on the generic ballot — is the third in the table.)

GENERIC BALLOT METHODS

PROJECTION

2016 presidential result + generic ballot

Ossoff +3.3

2012 presidential result + generic ballot

Handel +20.3

Blend* of past presidential results + generic ballot

Handel +2.6

2016 congressional result** + generic ballot

Handel +7.8

SPECIAL ELECTION RESULTS SO FAR METHODS

PROJECTION

2016 presidential result + special election results so far

Ossoff +11.9

2012 presidential result + special election results so far

Handel +11.7

Blend of past presidential results + special election results so far

Ossoff +6.0

2016 congressional result + special election results so far

Ossoff +0.8

FIRST-ROUND VOTE METHODS

PROJECTION

Aggregate party margin in first round

Handel +2.1

Aggregate party margin in first round + shift in generic ballot since first round

Ossoff +1.1

Aggregate party margin in first round + top-two margin in first round

Ossoff +4.8

Aggregate party margin in first round + top-two margin in first round + blend of past presidential results

Handel +0.4

Aggregate party margin in first round + top-two margin in first round + blend of past presidential results + generic ballot

Ossoff +3.3

POLLING METHODS

PROJECTION

Average of recent polls***

Ossoff +2.4

It’s hard to know how Georgia 6 “should” go

* The blend of past presidential results uses a 3:1 ratio of results from the 2016 and 2012 presidential elections

** The 2016 congressional result is adjusted for former Rep. Tom Price’s incumbency advantage

*** Recent polls include those from Trafalgar Group, Opinion Savvy, SurveyUSA, Landmark Communications and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Given that this is an election to Congress, one could also look at past congressional results for guidance. In 2016, the Republican incumbent Tom Price, who vacated the seat to become Trump’s secretary of Health and Human Services, won the district by 23 percentage points. This was somewhat less than his 32-point margin in 2014 and his 29-point margin in 2012, but it nevertheless suggested that the district was still quite red. Republican representatives such as Price had a significant incumbency advantage in 2016, as incumbents almost always do — even in supposedly anti-establishment environments. But even if you adjust for that advantage, the Republican lean of the district is about 15 points, still too much for Ossoff to overcome given the generic ballot. In fact, coming within several points of Handel would count as a good result for him given Price’s performance.

One could argue, however, that the standard for Democratic success should not be based on the generic ballot, but instead their results in special elections so far this year. By our method of benchmarking special elections, these have been very good for Democrats and are consistent with a political climate in which Democrats would win the national House vote by about 15 points.

That makes for a big difference. With a 7-point win in the House popular vote, as the generic ballot shows, Democrats would be only about even money to take over the House next year, given the way the vote is distributed among districts. With a 15-point win, they’d be all but assured of doing so — in fact, they’d probably have a massive wave election on the scale of 1994 or 2010, with lots of Republicans in supposedly safe districts being caught in the undertow. If Democrats are to keep pace with their special election results so far, then Ossoff probably should be winning the race, not just coming close — and Georgia 6 should be the election where Democrats go from “moral victories” to actual wins.

Another set of benchmarking methods involves extrapolating from the first-round vote in Georgia on April 18. In that election, multiple candidates from both parties were on the ballot. Ossoff got by far the most votes with 48 percent, with Handel finishing in a distant second at 20 percent to claim the other runoff spot. However, the Republican candidates combined got about 51 percent of the vote, compared to 49 percent for Ossoff and other Democrats together. Methods that factor in these results generally suggest a close race, but perhaps with Ossoff as a slight favorite. One of these methods, for instance, takes into account that while Republicans narrowly won the aggregate vote on April 18, the political climate has become somewhat more Democratic since then, perhaps just enough for Ossoff to win by a point or two.

Finally, there’s the polling, which shows Ossoff ahead by a not-very-safe margin of about 2 percentage points. You’d rather be 2 points ahead than 2 points behind, however.

So there are a lot of rather different, but nevertheless entirely reasonable, ways to interpret what might constitute a good or bad result for the parties on Tuesday. If either Handel or Ossoff wins by more than about 5 percentage points — which is entirely possible given the historic (in)accuracy of special election polls — you can dispense with some of the subtlety in interpreting the results, especially if the South Carolina outcome tells a similar story. Otherwise, Tuesday’s results probably ought to be interpreted with a fair amount of caution — and they probably won’t be.

As I said, however, the vote comes at a critical time for Republicans — and extracting any signal at all from Georgia might be enough to influence their behavior. Republicans really are in a pickle on health care. The AHCA is so unpopular that they’d have been better off politically letting it die back in March, at least in my view. But I don’t have a vote in Congress and Republicans do, and they’ve tallied the costs and benefits differently, given that the bill has already passed the House and is very much alive in the Senate. The central political argument Republicans have advanced on behalf of the bill is that failing to pass it would constitute a broken promise to repeal Obamacare, demotivating the GOP base. That argument will lose credibility if a Democrat wins in a traditionally Republican district despite what looks as though it will be high turnout.

There are also some tentative signs of congressional Republicans breaking with Trump, at least when it comes to matters related to Russia. Two weeks ago, former FBI Director James Comey testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee. Directors of other intelligence agencies and Attorney General Jeff Sessions have also recently testified before the committee. Then last week, the Senate overwhelmingly (by a 97-2 margin) approved a package of sanctions against Russia despite the White House’s objections to them. Those are serious, tangible steps for a Congress that had often moved in lockstep with Trump until the last few weeks.

As is the case with health care, Republicans don’t have an obviously correct strategy for handling Trump. Pulling the rug out from under him could create a vicious cycle in which Trump’s approval rating continues to decline and even some fairly partisan Republican voters begin to disapprove of his performance. But polls suggest that Trump is already quite unpopular with swing voters (and that his base has already shrunk), which might suggest that it’s smart for Republicans in competitive seats to rebuke Trump before matters get even worse.

In either case, the narrative that emerges from the Georgia 6 runoff will lack nuance and will oversimplify complex evidence. While special elections overall are a reasonably useful indicator in forecasting upcoming midterms, their power comes in numbers. A half-dozen special elections taken together are a useful sign; any one of them is less so. But we’re at a moment when Republicans have a lot of decisions to make now, and the story they tell themselves about the political environment matters as much as the reality of it. The narrative will probably be dumb, but it might matter all the same.

June 15, 2017

Emergency Politics Podcast: Trump Is Under Investigation

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

Embed |

New to podcasts?

Embed Code

In an emergency installment, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast reacts to reports that special counsel Robert Mueller is investigating whether President Trump tried to obstruct justice. According to The Washington Post, the investigation began days after the president fired FBI Director James Comey and includes interviews with top intelligence officials.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

What Would A Real GOP Break From Trump Look Like?

In this week’s politics chat, we game out what would happen if relations between the Trump administration and congressional Republicans worsen. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): With all the scandals and investigations swirling around President Trump — including the latest revelation that the special counsel’s investigation includes obstruction of justice — one of the central questions continues to be: How much do Republicans, particularly congressional Republicans, support the president? The answer to that question informs how much of Trump’s agenda will be enacted, and potentially how these various investigations will unfold.

But because I feel like Democrats, progressives and many media outlets have spent a lot of time wondering if this or that will “finally” be the thing that causes the GOP to back away from Trump, I don’t want to do that. Instead, let’s look forward. Two questions for discussion today:

What will be the real, tangible signs that Republicans have broken with Trump?

Trump has done a lot of things and Republicans are still with him, so what would actually cause such a break?

(We’ve got a skeleton crew for our chat today; Clare and Harry are off doing more important things, but the chat must go on.)

So, for example, let’s start with the latest news, breaking late on Wednesday: Robert Mueller, the special counsel investigating the whole Russia affair, is looking at whether Trump obstructed justice, according to The Washington Post. We suspected this, but this is ‼️ news, right?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Yeah, it’s big news. Let’s not take the too-cool-for-school attitude that it’s no big deal just because it was a predictable step. The president, less than five months into his term in office, is being investigated for obstruction of justice. That’s a big milestone.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Obstruction of justice is how presidents get impeached and/or removed (Richard Nixon was charged with obstruction by the House Judiciary Committee; Bill Clinton by the full House). So this is important, if true. And I doubt the Post wrote this without serious consideration, even if they had to use unnamed sources to do it.

micah: Here are the money paragraphs from the Post:

The move by special counsel Robert S. Mueller III to investigate Trump’s conduct marks a major turning point in the nearly year-old FBI investigation, which until recently focused on Russian meddling during the presidential campaign and on whether there was any coordination between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin. Investigators have also been looking for any evidence of possible financial crimes among Trump associates, officials said.

Trump had received private assurances from then-FBI Director James B. Comey starting in January that he was not personally under investigation. Officials say that changed shortly after Comey’s firing.

natesilver: Trump (or rather, Trump’s attorney’s spokesperson) is not really even denying it. In the Post’s story, he said it was a horrible, awful thing that the news was leaked. But he didn’t dispute the news, one bit.

micah: Comey’s firing may go down as one of the all-time blunders in U.S. political history.

perry: Other money part in that story:

The Justice Department has long held that it would not be appropriate to indict a sitting president. Instead, experts say, the onus would be on Congress to review any findings of criminal misconduct and then decide whether to initiate impeachment proceedings.

So ultimately, no matter what Mueller finds, it is still up to Congress.

natesilver: There are now two clear roads to impeachment. Or not to impeachment, per se, but to Congress having to wrestle with the question of impeachment.

Mueller finds that Trump obstructed justice;

Trump fires Mueller.

micah: 3. Mueller finds collusion?

perry: That is not clear.

natesilver: Yeah, I mean, maybe, but that’s a murky path.

The point is that Congress can’t avoid the impeachment question if either Nos. 1 or 2 happen. An impeachment proceeding is basically the correct remedy in those cases. Congress might decide it didn’t hit the threshold that made it an impeachable offense, but it couldn’t just make it all go away, at that point.

perry: And that brings us to politics. Because those roads involve either Republicans pushing for the removal of their party leader, or Democrats winning the House in 2018 and then doing it.

micah: So right, that’s the thing though: Do we really know a GOP-controlled Congress would turn on Trump even in some of these scenarios? Nothing Republicans have done so far suggests that.

natesilver: I think you’re presuming that they haven’t done anything, which isn’t completely true.

micah: What have they done?

natesilver: They had former FBI Director James Comey testify. They applauded the appointment of a special counsel, although some of them are starting to express reservations about Mueller now.

perry: Republicans have also set up investigations in the House and Senate to varying degrees. Some of the Republicans, I would say, asked tough questions of Attorney General Jeff Sessions during the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Tuesday. And basically defended Comey’s honesty, which Trump had questioned.

There is a new bill moving through Congress, with GOP support, that would basically prevent Trump from lifting sanctions against Russia. Which feels like a big line being drawn. It passed 97-2 in the Senate on Wednesday, which seems like a firm of rejection of Trump’s attempts to shift the U.S. toward a less antagonistic relationship with Russia. (The bill still must pass the House and then either be signed by Trump or a two thirds majority in each house override his veto.) Trump lifting sanctions on Russia would have been a firing-Comey-level political disaster, and his party may be ending any chance of the president doing that.

natesilver: And all of this is less than five months into his presidency. I think you can accuse the GOP of a lot of things, including very often pandering to Trump, but I think Russia is a somewhat bad example of this phenomenon.

micah: OK, I’m going to play the role of “Democrat who’s pissed off Republicans aren’t acting more like Democrats with regards to Trump” in this chat ….

I think you’re both setting a very low bar for Republicans. During the Comey and Sessions hearings, many Republicans ran interference for the administration.

perry: Right.

micah: Trump fired an FBI director investigating his campaign and then said that’s why he fired him.

His administration has made a mess of many things: the travel ban, the foreign trip, etc. And more recently, he’s thrown House Republicans under the bus, pushing them to pass the American Health Care Act and now calling the bill “mean.”

And your answer to all that is basically “but Republicans have nibbled around the edges.”

perry: “Trump has done a lot of things and Republicans are still with him, so what would actually cause such a break?” This was your original question. I think we have to consider the possibility that partisanship and tribalism are now so strong that the answer is potentially never, assuming he does not commit a violent crime. Are we sure if he fired Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and Mueller that Republicans on the Hill would break with him? I’m not.

micah: Yeah, what do you think would happen if tomorrow Trump fires Rosenstein and Mueller?

natesilver: I wouldn’t be shocked either way, but I think firing Rosenstein and Mueller might really be a breaking point for them.

micah: I’ve heard that before.

natesilver: But when?

perry: But the fact that we are saying “might” is telling.

micah: Why would firing Mueller be any different than firing Comey? For Republicans.

natesilver: Firing Comey has gotten Trump into huge trouble.

micah: Define “trouble.”

natesilver: The possibility that he’ll be impeached down the line somewhere.

micah: Remember, we’re talking about Republicans, though. That possibility basically rests on Democrats winning the House in 2018.

natesilver: I get that, but there’s a process here. They’re not going to impeach him when he’s still sniffing a 40 percent approval rating (OK, 38 percent).

micah: So what trouble is he in with Republicans, again?

perry: We need to define what Republicans reining him in means more precisely. I agree with Nate, Republicans have limited him some. But they are nowhere close to, say, drawing lines and declaring if you cross these, you will be removed from office. And he is crossing a lot of what we thought were real lines. Firing Comey being the biggest one.

natesilver: I mean, part of the problem is that short of impeachment, there aren’t a ton of steps to take. But impeachment itself is a dramatic measure.

micah: So what would Republicans do, short of impeachment? Let’s go from least to most drastic.

perry: The least dramatic would be to say they are “concerned” a lot and do nothing else, like they have been doing for most of the year. I would say that bringing Comey to the Hill and ramping up these investigations has taken this to a second, more active stage.

micah: Is passing legislation to limit what Trump can do, such as on Russia sanctions, part of Stage 2 or is that on to Stage 3?

perry: I still think of that as a kind of Stage 2. I assume Trump can sign that bill and pretend it was not targeted at him.

natesilver: I’d say it’s Stage 2b. We’ll also want to see how they deal with further appointments that Trump makes. He probably avoided a fight by nominating Christopher Wray as Comey’s replacement at FBI instead of someone more obviously partisan.

perry: Some more aggressive options: 1. demand Trump make promises not to fire Mueller, Rosenstein, Wray; 2. demand he hire a powerful chief of staff and give that person lots of power on staffing/decisions at White House; 3. censure.

micah: Censure seems like Stage 9.

natesilver: Yeah, I will grant you that not drawing a line in the sand — re: firing Mueller — isn’t a great look.

Again, the context here, though, is that he’s only been president for five months. It’s easy to forget that. So the question is where they are today, versus where they were in January.

perry: And I would say the evidence so far is that Trump is breaking norms at a faster rate than his party is reining him in. Which makes me think maybe his party won’t ever rein him in. The attacks on Mueller, after the Comey firing, have been surprising. Kellyanne Conway was attacking Mueller on Twitter. Sarah Huckabee Sanders said Trump had the right to fire Mueller but did not intend to. These seem like threats to Mueller. And look at Paul Ryan’s comment in response. It was not exactly strong.

natesilver: Oh we could have a whole separate chat about Paul Ryan.

micah: He’s been the most amazing part of all this, for me.

perry: Really? Tell me more.

micah: I guess I’ve just been surprised at how fully he’s continued to defend and back Trump. I don’t think I ever expected him to be Lindsey Graham, for example, but I didn’t expect him to be Jeff Sessions, either.

perry: Isn’t he just Mitch McConnell, but in the House?

micah: McConnell has seemed to have more of a “I don’t give a shit what Trump says” attitude?

natesilver: For me, the most revealing actions that Republicans have taken are not on Trump, but on health care.

It’s an extremely unpopular bill, and certainly not the bill that Trump ran upon.

They’re violating a lot of norms in terms of the lack of transparency in the drafting and vetting process for the bill.

micah: So what’s that reveal?

natesilver: Well, since the main effect of the bill is to cut taxes, it reveals that cutting taxes (or if you prefer, reducing the size of government) is a massive goal for them.

micah: BREAKING NEWS!!!!

June 13, 2017

Donald Trump Is Making Europe Liberal Again

On Dec. 4 last year, less than a month after Donald Trump had defeated Hillary Clinton, Austria held a revote in its presidential election, which pitted Alexander Van der Bellen, a liberal who had the backing of the Green Party, against Norbert Hofer of the right-wing Freedom Party. In May 2016, Van der Bellen had defeated Hofer by just more than 30,000 votes — receiving 50.3 percent of the vote to Hofer’s 49.7 percent — but the results had been annulled and a new election had been declared. Hofer had to like his chances: Polls showed a close race, but with him ever so slightly ahead in the polling average. Hofer cited Trump as an inspiration and said that he, like Trump, could overcome headwinds from the political establishment.

So what happened? Van der Bellen won by nearly 8 percentage points. Not only did Hofer receive a smaller share of the vote than in May, but he also had fewer votes despite a higher turnout. Something had caused Austrians to change their minds and decide that Hofer’s brand of populism wasn’t such a good idea after all.

Left: Far-right candidate Norbert Hofer. Right: Independent presidential candidate Alexander van der Bellen.

Georg Hochmuth/AFP/Getty Images; Alex Domanski/Getty Images

The result didn’t get that much attention in the news outlets I follow, perhaps because it went against the emerging narrative that right-wing populism was on the upswing. But the May and December elections in Austria made for an interesting controlled experiment. The same two candidates were on the ballot, but in the intervening period Trump had won the American election and the United Kingdom had voted to leave the European Union. If the populist tide were rising, Hofer should have been able to overcome his tiny deficit with Van der Bellen and win. Instead, he backslid. It struck me as a potential sign that Trump’s election could represent the crest of the populist movement, rather than the beginning of a nationalist wave:

Wonder if Trump could hurt right-wing nationalist movements in Europe. People may associate movements with Trump. Trump way unpopular in EU.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) December 4, 2016

It was also just one data point, and so it had to be interpreted with caution. But the pattern has been repeated so far in every major European election since Trump’s victory. In the Netherlands, France and the U.K., right-wing parties faded down the stretch run of their campaigns and then further underperformed their polls on election day. (The latest example came on Sunday in the French legislative elections, when Marine Le Pen’s National Front received only 13 percent of the vote and one to five seats in the French National Assembly.) The right-wing Alternative for Germany has also faded in polls of the German federal election, which will be contested in September.

The beneficiaries of the right-wing decline have variously been politicians on the left (such as Austria’s Van der Bellen), the center-left (such as France’s Emmanuel Macron) and the center-right (such as Germany’s Angela Merkel, whose Christian Democratic Union has rebounded in polls). But there’s been another pattern in who gains or loses support: The warmer a candidate’s relationship with Trump, the worse he or she has tended to do.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron have both been the beneficiaries of the right-wing decline.

Gabriel Rossi/LatinContent/Getty Images; Lionel Bonaventure/AFP/Getty Images

Merkel, for instance, has often been criticized by Trump and has often criticized him back. Her popularity has increased, and her advisers have half-jokingly credited the “Trump factor” for the sharp rebound in her approval ratings over the past year.

By contrast, U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May has a warmer relationship with Trump. She was the first foreign leader to visit Trump in January after his inauguration, when she congratulated him on his “stunning electoral victory.” But she was criticized for not pushing back on Trump as much as her European colleagues or her rivals from other parties after Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris climate accords on June 1 and then instigated a fight with the mayor of London after the terrorist attack in London two days later. Her Conservatives suffered a humiliating result, blowing a 17 percentage point polling lead and losing their majority in Parliament; it’s now not clear how much longer she’ll continue as prime minister. Trump was not May’s only problem, but he certainly didn’t help.

Let’s take a slightly more formal tour of the evidence from these countries:

The Netherlands

Geert Wilders.

Carl Court/Getty Images

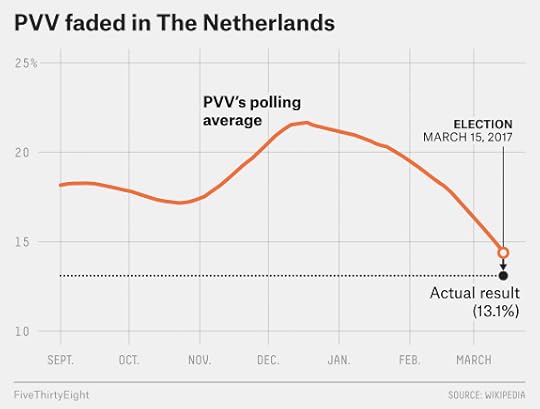

The Netherlands’ Geert Wilders, of the nationalist Party for Freedom (in Dutch, Partij voor de Vrijheid or PVV), hailed Trump’s victory and predicted that it would presage a populist uprising in Europe. And PVV initially rose in the polls after the U.S. election, climbing to a peak of about 22 percent of the vote in mid-December — potentially enough to make it the largest party in the Dutch parliament. But it faded over the course of the election, falling below 15 percent in late polls and then finishing with just 13 percent of the vote on election day on March 15. Those results were broadly in line with the 2010 and 2012 elections, when Wilders’ party had received between 10 and 15 percent of the vote. The center-right, pro-Europe VVD remains the largest party in the Netherlands.

France

Marine Le Pen.

Chesnot/Getty Images

Reciprocating praise that Le Pen had offered to Trump, Trump expressed support for Le Pen after a terrorist attack in Paris in April and predicted that it would “probably help” her to win the French presidential election. But over the course of a topsy-turvy race, Le Pen’s trajectory was downward. Last fall, she’d projected to finish with 25 to 30 percent of the vote in the first round of the election, which would probably have been enough for her to finish in pole position for the top-two runoff. Her numbers declined in December and January, however, and then again late in the campaign. She held onto the second position to make the runoff, but just barely, with 21 percent of the vote. Then she was defeated 66-34 percent by Macron in the runoff, a considerably wider landslide than polls predicted.

Le Pen’s National Front endured another disappointing performance over the weekend in the French legislative elections. Initially polling in the low 20s — close to Le Pen’s share of the vote in the first round of the presidential election — the party declined in polls and turned out to receive only 13 percent of the vote, about the same as their 14 percent in 2012. As a result, National Front will have only a few seats in the French Assembly while Macron’s En Marche! — which ran jointly with another centrist party — will have a supermajority.

The United Kingdom

Theresa May.

Jack Taylor/Getty Image

While the big news in the U.K. was May’s failed gamble in calling a “snap” parliamentary election, it was also a poor election for the populist, anti-Europe UK Independence Party. Having received 13 percent of the vote in 2015, UKIP initially appeared poised to replicate that tally in 2017 (despite arguably having had its raison d’être removed by the Brexit vote). But it began to decline in polls in the spring, and the slump accelerated after the election was called in April. UKIP turned out to receive less than 2 percent of the vote and lost its only seat in Parliament.

UKIP’s collapse in some ways makes May’s performance even harder to excuse. Most of the UKIP vote went to the Conservatives, providing them with a boost in constituencies where UKIP had run well in 2015. But the Conservatives lost votes on net to Labour (although there was movement in both directions), Liberal Democrats and other parties. It’s perhaps noteworthy that Conservatives performed especially poorly in London after Trump criticized London Mayor (and Labour Party member) Sadiq Khan, losing wealthy constituencies such as Kensington that had voted Conservative for decades.

Germany

Frauke Petry.

Markus Schreiber/AP photo

The German election to fill seats in the Bundestag isn’t until September, but there’s already been a fair amount of movement in the polls. Merkel’s CDU/CSU has rebounded to the mid- to high 30s from the low 30s last year. And the left-leaning Social Democratic Party surged after Martin Schulz, the former president of the European Parliament, announced in January that he’d be their candidate for the chancellorship (although the so-called “Schulz effect” has since faded slightly). Thus, the election is shaping up as contest between Schulz, who has sometimes been compared to Bernie Sanders and who is loudly and proudly pro-Europe, and Merkel, perhaps the world’s most famous advocate of European integration.

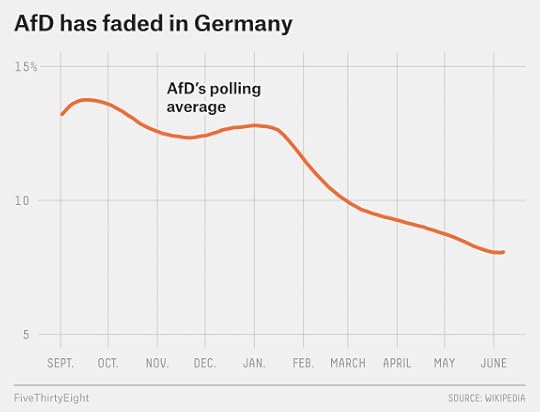

The losers have been various smaller parties, but especially the right-wing Alternative for Germany (in German, Alternative für Deutschland or AfD) and their leader, Frauke Petry, who have fallen from around 12 to 13 percent in the polls late last year to roughly 8 percent now. Meanwhile, both Schulz and Merkel have sought to wash their hands of Trump. Instead of criticizing Merkel for being too accommodating to Trump, Schulz instead recently denounced Trump for how he’d treated Merkel.

So if you’re keeping score at home, right-wing nationalist parties have had disappointing results in Austria, the Netherlands, France and the U.K., and they appear poised for one in Germany, although there’s a long way to go there. I haven’t cherry-picked these outcomes; these are the the major elections in Western Europe this year. If you want to get more obscure, the nationalist Finns Party underperformed its polls and lost a significant number of seats in the Finnish municipal elections in April, while the United Patriots, a coalition of nationalist parties, lost three seats in the Bulgarian parliamentary elections in March.

Despite the differences in electoral systems from country to country — and the quirky nature of some of the contests, such as in France — it’s been a remarkably consistent pattern. The nationalist party fades as the election heats up and it begins to receive more scrutiny. Then it further underperforms its polls on election day, sometimes by several percentage points.

While there’s no smoking gun to attribute this shift to Trump, there’s a lot of circumstantial evidence. The timing lines up well: European right-wing parties had generally been gaining ground in elections until late last year; now we suddenly have several examples of their position receding. Trump is highly unpopular in Europe, especially in some of the countries to have held elections so far. Several of the candidates who fared poorly had praised Trump — and vice versa. He’s explicitly become a subject of debate among the candidates in Germany and the U.K. To the extent the populist wave was partly an anti-establishment wave, Trump — the president of the most powerful country on earth — has now become a symbol of the establishment, at least to Europeans.

There are also several caveats. While there have been fairly consistent patterns in elections in the wealthy nations of Western Europe, we have little evidence for what will happen in the former nations of the Eastern Bloc, such as Hungary, which has moved substantially to the right in recent years. (The next Hungarian parliamentary election is scheduled for early next year.) Turkey is a problematic case, obviously, especially given questions about whether elections are free or fair there under Tayyip Erdogan.

And even within these Western European countries, while support for nationalist parties has generally been lower than it was a year or two ago, it may still be higher than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

Politics is often cyclical, and endless series of reactions and counterreactions. Sometimes, what seems like the surest sign of an emerging trend can turn out to be its peak instead. It’s usually hard to tell when you’re in the midst of it. Trump probably hasn’t set the nationalist cause back by decades, and the rise of authoritarianism continues to represent an existential threat to liberal democracy. But Trump may have set his cause back by years, especially in Western Europe. At the very least, it’s become harder to make the case that the nationalist tide is still on the rise.

June 12, 2017

Politics Podcast: Who Makes Up The Base?

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

Embed |

New to podcasts?

Embed Code

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team takes on the state of the Democratic and Republican bases. Do moderates have a place in either party’s base? And should President Trump attempt to expand his appeal beyond his base? The crew also previews Tuesday’s Democratic primary in Virginia, where Tom Perriello and Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam are competing to be the party’s candidate for governor.

Plus, in “good use of polling or bad use of polling”: How untrustworthy is Trump compared to former FBI Director James Comey?

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

June 9, 2017

Emergency Politics Podcast: The U.K. Election

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

Embed |

New to podcasts?

Embed Code

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team called an emergency podcast to react to the results of the U.K. election. No party won a majority in a snap election called by Prime Minister Theresa May, who was hoping to expand her previous majority as she negotiates the U.K.’s exit from the European Union.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

The U.K. Election Wasn’t That Much Of A Shock

Despite betting markets and expert forecasts that predicted Theresa May’s Conservatives to win a large majority in the U.K. parliamentary elections, the Tories instead lost ground on Thursday, resulting in a hung parliament. As we write this in the early hours of Friday morning, Conservatives will end up with either 318 or 319 seats, down from the 330 that the Tories had in the previous government. A majority officially requires 326 seats.

Conservatives will wind up with the plurality of seats and the plurality of the popular vote. It’s still possible — indeed, probable — that Conservatives will form a government, either as a minority government or as part of a coalition, most likely with the Democratic Unionist Party, which won 10 seats in Northern Ireland. By contrast, a coalition between Labour, Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party (which lost a significant number of seats) would have about 310 seats — short of a majority. It’s also probable that May will continue as Conservative leader and prime minister, the BBC reports.

With 42 to 43 percent of the vote, in fact, the Tories should wind up with their largest vote share since under Margaret Thatcher. But the outcome isn’t being interpreted as any sort of moral victory for May; instead, it’s being portrayed in the British media as a disaster. That’s because at the time May unexpectedly called for a “snap” election seven weeks ago, polls showed Conservatives leading Labour by 17 percentage points and poised to win as many as 400 seats in parliament. Instead, they went backward and are at best hanging on by a thread. It’s even plausible that there could be another election later this year.

And yet, the results should not have been all that surprising if one followed this year’s polling and the polling history of the U.K. closely. The final polling average showed conservatives ahead by 6.4 percentage points. In fact, Conservatives should wind up winning the popular vote by 2 to 3 percentage points. That means the polling average will have been off by about 4 percentage points. (The table below lists YouGov twice because they polled the race using two different methods.)

POLLSTER

CON.

LAB.

UKIP

LIB. DEM.

OTHER

LEAD

Qriously

39%

41%

3%

6%

11%

Lab.

3

Survation

41

40

2

8

8

Con.

1

SurveyMonkey

42

38

4

6

10

Con.

4

Norstat

39

35

6

8

12

Con.

4

YouGov.co.uk

42

38

3

9

7

Con.

4

Kantar Public

43

38

4

7

8

Con.

5

YouGov (The Times)

42

35

5

10

8

Con.

7

Opinium

43

36

5

8

7

Con.

7

Ipsos MORI

44

36

4

7

7

Con.

8

Panelbase

44

36

5

7

8

Con.

8

ORB

45

36

4

8

7

Con.

9

ComRes

44

34

5

9

7

Con.

10

ICM

46

34

5

7

7

Con.

12

BMG Research

46

33

5

8

9

Con.

13

Average

42.9

36.4

4.3

7.7

8.3

Con.

6.4

The U.K. polls missed, but not by that much

Percentages are rounded.

Sources: UK Polling Report, Wikipedia, @britainelects

While a 4-point error would be fairly large in the context of a U.S. presidential election, it’s completely normal in the case of the U.K. On average in U.K. elections since World War II, the final set of polls have missed the Conservative-Labour margin by 3.9 percentage points, almost exactly in line with this year’s error.

YEAR

POLLING AVERAGE

ACTUAL RESULT

ACTUAL V. POLLS

2017

Con.

6.4

Con.

2.4*

Lab.

4.0

–

2015

Con.

0.6

Con.

6.5

Con.

5.9

–

2010

Con.

7.9

Con.

7.2

Lab.

0.7

–

2005

Lab.

6.2

Lab.

2.9

Con.

3.3

–

2001

Lab.

14.2

Lab.

9.4

Con.

4.8

–

1997

Lab.

17.5

Lab.

12.8

Con.

4.7

–

1992

Lab.

1.5

Con.

7.6

Con.

9.1

–

1987

Con.

8.1

Con.

11.7

Con.

3.6

–

1983

Con.

20.3

Con.

15.2

Lab.

5.1

–

1979

Con.

5.9

Con.

7.2

Con.

1.3

–

1974 (Oct.)

Lab.

9.2

Lab.

3.6

Con.

5.6

–

1974 (Feb.)

Con.

2.9

Con.

0.6

Lab.

2.3

–

1970

Lab.

4.1

Con.

3.4

Con.

7.5

–

1966

Lab.

11.2

Lab.

6.0

Con.

5.2

–

1964

Lab.

1.5

Lab.

0.8

Con.

0.7

–

1959

Con.

3.2

Con.

5.6

Con.

2.4

–

1955

Con.

3.3

Con.

3.2

Lab.

0.1

–

1951

Con.

4.5

Lab.

0.8

Lab.

5.3

–

1950

Con.

0.7

Lab.

2.8

Lab.

3.5

–

1945

Lab.

6.0

Lab.

8.0

Lab.

2.0

–

U.K. polls haven’t been very accurate historically

* 2017 results reflect a preliminary estimate. For elections since 1974, results reflect Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) only and not Northern Ireland. Most UK pollsters have excluded Northern Ireland from their samples in recent years.

Source: Report of the Inquiry into the 2015 British general election opinion polls, Researchbriefings.parliament.uk

As has been the case in several recent elections, therefore, the problem was not so much with the polls, or at least not with some of the polls. The problem was with how people were interpreting them. Betting markets on Thursday morning showed Conservatives with only about a 15 percent chance of failing to achieve a majority. In our view, this was unrealistically low given that their lead in the polling average was close to the Tories’ winning margin in 2015 (6.5 percentage points), which had barely been enough for a majority. Taken at face value, the polls suggested a result wherein Conservatives took barely over half the seats, not a blowout.

In that way, this result was much like the 2016 U.S. presidential election, when Donald Trump was just a “normal polling error” away from winning, and yet people seemed to have a lot more confidence than they should have had that Hillary Clinton was going to win. The Brexit vote provides another example of this groupthink; the London-based media found a “Leave” vote so “unthinkable” that they ignored polls showing the race almost tied. The confirmation bias wasn’t as bad in this election as it was for Brexit or Trump, but there were signs of it here and there: YouGov took a huge amount of abuse ahead of the election for daring to publish a model that (correctly, it turned out) showed a hung parliament, for example. Therefore, this was the latest in a string of failures for the conventional wisdom that has given rise to our half-sarcastic (but half-serious) “first rule of polling errors”: whenever the pundits try to outguess the polls, you should assume that the polls will miss in the opposite direction of what they expect.

But while pollsters had middling results on the whole, some did much better than others. Indeed, the polls in the lead-up to this election showed a wide range of outcomes, with final polls showing margins that ranged from Labour 3 to Conservatives 13. There were a number of pollsters who had results very close to the final outcome, including Survation, Kantar Public, Norstat and SurveyMonkey. That’s far different than what occurred two years ago in the 2015 U.K. election, when all but two polls had the election within a narrow range between Labour 1 to Conservatives 1. That had been a sign of pollsters “herding” toward a consensus instead of behaving independently.

Although pollsters may not have herded in this election, however, some of them were guilty of another sin: distrusting their own data. After the 2015 election, many pollsters applied much more aggressive turnout models which weighted down the number of younger voters who are generally more favorable to Labour. In turn, they boosted the percentage of older voters, who are generally more friendly toward the Conservatives.

Given the substantial age gap in this election, the turnout weighting had an especially big effect. Among the final polls, seven of them adjusted their results in this way, in all but one case yielding a more friendly result for the Conservatives. You can see this in the table below, which looks at the raw results for these seven pollsters and their adjusted results. The average difference was nearly 6 percentage points in Tories’ favor. That’s a huge gap. In 2015, such adjustments had shifted the results by only about 1 point toward Conservatives. And likely voter models in U.S. presidential elections typically only move the numbers by a couple of percentage points in either direction (usually toward Republicans).

POLLSTER

RAW VOTING INTENTION

HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION

Ipsos MORI

Tied

—

Con.

8

–

BMG Research

Con.

1

–

Con.

13

–

Survation

Con.

1

–

Con.

1

–

ICM

Con.

5

–

Con.

12

–

YouGov

Con.

2

–

Con.

7

–

ComRes

Con.

5

–

Con.

10

–

Opinium

Con.

4

–

Con.

7

–

Average

Con.

2.6

–

Con.

8.3

–

Pollster adjustments shifted the results toward Conservatives

Source: Huffington Post Pollster, BMG Research

These adjustments proved to be counterproductive in the U.K. The average “raw” result from these polls — which applied demographic weights but otherwise relied on voters’ self-reported likelihood to vote instead of complicated turnout models — showed a 2.7 percentage point lead for the Conservatives, very close to their actual results. But the “headline” version of the polls, which applied the turnout models and removed or reallocated undecided voters, showed an 8.3-percentage point lead for the Conservatives instead.

Although polling the U.K. is hard, we’re not very sympathetic to the pollsters who made these adjustments. That’s because turnout models were probably not the cause of the Conservative underestimation in 2015. According to a report prepared by the British Polling Council and the Market Research Society, the error had more to do with the fact that the initial samples were unrepresentative of the overall population.

The 2017 election therefore seems to be a case of an overcorrection. The pollsters apparently did a good enough job of weighting the raw samples properly, which got them fairly close to the right outcome. Then on top of that, some of them gave extra weight to the Conservatives through their turnout models. As a result, they discounted signs of a youth-driven Labour turnout surge. As was the case in the U.S. with Bernie Sanders, younger voters turned out in a big way for Labour’s left-wing leader, Jeremy Corbyn. It’s one thing for a pollster to get an outcome wrong because voters fail to turn out when they say they will. But if voters tell you they’re going to turn out, you ignore them, and they show up to vote anyway, you really don’t have much of a defense.

The overall theme is that many people who covered the U.K. election (whether as pollsters or pundits or journalists) were guilty of fighting the last war. It’s true that Conservatives have some history of outperforming their polls in the U.K. and had done so in 2015. Yet, those previous underestimations may have occurred just by chance or for reasons peculiar to each election. Many people were so preoccupied with not underestimating Conservatives that they failed to consider how they might be underestimating Labour instead. Thus, they largely ignored the possibility of a hung parliament despite its being an entirely realistic outcome. (We estimated the chances of it to be about 1 in 3.)

But if the results ought not to have been much of a surprise given where the polls stood on Thursday morning, what about where they stood in April, when May called the election as Conservatives led by 17 percentage points? While this is a trickier case, we’re still not sure the outcome should be considered all that shocking.

When May called the election, we noted that she was undertaking a risky move because the U.K. polls had historically been volatile (in addition to not being very accurate even at the end of the campaign). And there were some reasons to expect an especially large amount of volatility in this race. The election was unexpected, so voters had only about 50 days to get to know the candidates. May had only become prime minister last July and might still have been in her “honeymoon period” when she skated above the partisan fray — something that was bound to change once she asked voters to go to the polls again. A better economy traditionally boosts the incumbent party, but the British economy wasn’t doing all that well. And U.K. elections are typically fairly close — only three of them since World War II have been decided by double-digit popular vote margins — so there was some risk of reversion to the mean.

There were also a lot of events during the campaign, but the compressed time frame makes them hard to sort out from one another. How much did the Conservative manifesto hurt the Tories? Did terrorist attacks in Manchester and London work against them? Was May’s perceived softness toward President Trump a factor, especially after Trump began to attack London Mayor Sadiq Khan? Given the results of the French election, is there an overall resurgence toward liberal multiculturalism in Europe, perhaps as a reaction to Trump? We don’t know the answers to these questions, although we hope to explore some of them in the coming days. We do know that elections around the world are putting candidates, pollsters and the media to the test, and there isn’t a lot they can be taking for granted.

June 8, 2017

Emergency Politics Podcast: Comey’s Testimony

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

Embed |

New to podcasts?

Embed Code

In an emergency installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the team reacts to former FBI Director James Comey’s testimony before the Senate intelligence committee. The FiveThirtyEight team also tracked Comey’s testimony in real time on our live blog.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

June 7, 2017

The Three Scenarios For The U.K. Election

On the morning of the U.S. presidential election, we pointed out that there were three scenarios for what might transpire that night, each of which were about equally likely. In Scenario No. 1, the polls would be spot-on; Hillary Clinton would win narrowly, with a 3-to-4 percentage point popular victory and somewhere on the order of 300 electoral votes. In Scenario No. 2, Clinton would outperform her polls, leading to a near-landslide victory and possible wins in states such as Arizona and Georgia which had traditionally favored Republicans. And in Scenario No. 3, Donald Trump would beat his polls; because the Electoral College favored Trump, even a small polling error in his favor would probably be enough to make him president. Scenario No. 3 is the one that transpired, but it wasn’t any more or less likely than the other two.

There’s a similar set of scenarios in play for the U.K. general election, which is taking place on Thursday. Conservatives lead by an average of 6 to 7 percentage points in recent polls, but with a wide range — anywhere from a 3-point Labour lead in one survey to a 13-point Conservative lead in another. Some of these polls were conducted partly or wholly before the terror attack in London on Saturday, but it’s not clear what effect the attack has had, with polls differing on whether the Conservative lead is rebounding and expanding slightly or instead continuing to narrow.

POLLSTER

CON.

LAB.

UKIP

LIB. DEM.

OTHER

LEAD

BMG Research*

46

33

5

8

9

Con.

+13

Survation*

41

40

2

8

8

Con.

+1

ICM*

46

34

5

7

7

Con.

+12

YouGov*

42

35

5

10

8

Con.

+7

ComRes*

44

34

5

9

7

Con.

+10

SurveyMonkey*

42

38

4

6

10

Con.

+4

Opinium*

43

36

5

8

7

Con.

+7

Qriously*

39

41

3

6

11

Lab.

+3

Kantar Public

43

38

4

7

8

Con.

+5

Panelbase

44

36

5

7

8

Con.

+8

Norstat

39

35

6

8

12

Con.

+4

ORB

45

36

4

8

7

Con.

+9

Ipsos MORI

45

40

2

7

6

Con.

+5

Average

43.0

36.6

4.2

7.6

8.3

Con.

+6.3

U.K. polls are still all over the place

* Poll conducted entirely after London terror attack on June 3.

Sources: UK Polling Report, Wikipedia, @britainelects

We don’t have a model of this election — but in our view, there’s no way around the fact that uncertainty is high and that nobody should be surprised about the outcome unless perhaps Labour wins an outright majority of seats. U.K. polls have not historically been very accurate. And pundit attempts to outguess the polls have often been even worse. (In 2016, pundits and betting markets were notoriously confident that Britain would vote to remain within the European Union even when polls showed a nearly even race.) However, if one takes the polling average but assumes that the error is as high as it has been historically, then it turns out that each of these three outcomes are roughly as likely as one another:

Scenario No. 1: Narrow-ish Conservative majority

In this case, the polling average is fairly accurate (although some individual polls will unavoidably be off). May wins by 5 to 9 percentage points, close to the 6.5-point margin that Conservatives won by in 2015. At the higher end of this range, Conservatives might gain one or two dozen seats in Parliament from the 330 they had (there are 650 seats in total). At the narrower end, they might just barely hang onto their majority.

Either outcome would be disappointing relative to when May called the election in April — when Conservatives were ahead by about 17 points on average and possibly headed for a 400-seat majority — and wouldn’t speak highly of her political skills. But it would also be something of a relief given how much polls have tightened since then and still possibly give them their largest majority since 1987.

Scenario No. 2: Conservative landslide

Since Conservatives lead by 6 to 7 percentage points on average, and since U.K. polls have missed by an average of about 4 points in the past, it’s not at all hard to imagine them winning the popular vote by double digits. Indeed, Conservatives have often outperformed their polls in recent U.K. elections, such as in 2015 when polls implied a hung parliament and they instead won a majority. On Saturday, we made a long argument as to why this doesn’t necessarily imply that they will beat their polls again. The gist of it is that pollsters are seeking to correct for their past errors — in some cases, by applying turnout models that shift the polls by several percentage points in Tories’ favor — so it may be a mistake to apply a mental adjustment on top of the one that pollsters are already making.

But a Conservative overperformance is certainly possible if Labour’s youth turnout doesn’t materialize, if undecided voters worry about the unpopular Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn running the government, or if the terror attack pushes voters to May. Such an outcome might yield somewhere in the neighborhood of 375 seats in Parliament for Conservatives — perhaps more if Labour holds ground in the cities but collapses in working-class areas, as happened to Democrats in the 2016 U.S. election.

Scenario No. 3: Conservatives lose their majority

To be precise, I mean that Conservatives win fewer than 326 seats; we’re making no predictions about whether they’d then find a coalition partner to form their next government or if there would be some sort of Corbyn-led government instead. Betting markets as of Wednesday night imply there’s only about a 15 percent chance of Conservatives failing to win an outright majority.

If you take the polls at face value, however, the chances are surely higher than that. If Labour beats the final polling average by only 1 or 2 percentage points, both sides will start having to sweat out the results from individual constituencies. And if they beat their polls by much more than that, May’s majority is probably toast. If this happens, the adjustments that pollsters made to discount Labour turnout will have proven to be counterproductive, and the lesson for pollsters will be to trust their data instead of making too many presumptions about who is likely to vote. The lesson for May, meanwhile, would be never to call a “snap” election again in a country where public opinion can shift so rapidly.

Emergency Politics Podcast: Comey’s Prepared Testimony

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

Embed |

New to podcasts?

Embed Code

In an emergency podcast, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team discusses former FBI Director James Comey’s prepared testimony, which was released in advance of his appearance before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. His remarks confirm much of the reporting that had been leaked by anonymous sources over the past month.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers