Nate Silver's Blog, page 104

May 22, 2017

Will Donald Trump Be Impeached?

After a cacophonous two weeks of political news, a new sound has begun to emerge from Washington: the word “impeachment.” Following the news that President Trump may have tried to bully FBI director James Comey out of investigating Michael Flynn’s ties to Russia, Sen. Angus King of Maine, an independent, told CNN that recent allegations, if true, are already making impeachment hearings more likely. Rep. Al Green, a Democrat from Texas, became the first congressman to call for Trump’s impeachment from the House floor. And even some Republicans in blue-leaning districts, such as Rep. Carlos Curbelo of Florida, have begun to entertain impeachment as a possibility.

This might all seem like a liberal fantasy: No president has ever been booted out of the job, and only Richard Nixon resigned under the pressure of the impeachment process.

But people putting money on the line are taking impeachment seriously. According to the prediction market Betfair, the chance that Trump will fail to serve out his four-year term is about 50 percent (!). There’s even a 20 to 25 percent probability (!!) that Trump doesn’t finish out 2017 in office, these bettors reckon.

Are those numbers within the realm of reason? It isn’t easy to forecast Trump’s odds of impeachment, or of his removal from office. There isn’t enough data to build a statistical model of it, in the way we would for an election. But we can say that there are two opposite forces tugging strongly on the impeachment rope:

On the one side, there’s Trump’s escalating pattern of (alleged) misconduct, which increasingly reflects behavior that has been used as grounds for impeachment in the past.

On the other side, there’s the intense partisan loyalty of Republicans, both among GOP members of Congress and among voters in the states and districts they represent.

So long as these sides are pulling with roughly equal force, Trump isn’t going to be removed from office, which would require a two-thirds majority in the Senate. But if something snaps — if Republicans have reason to think Trump has become a liability even in red states — look out. History suggests Trump could be vulnerable under such circumstances, despite the historical rarity of impeachment. Here’s how to think about the chances.

If Trump left office early, he of course wouldn’t be the first president to do so. There are various ways a president’s term can end prematurely. But some of the possibilities apart from impeachment are fairly remote.

Eight presidents died during their terms. While that possibility can’t be ruled out for Trump, the odds of it are relatively low. Actuarial tables show that a 70-year-old American man (Trump’s age) has only about a 10 percent chance of dying over his next four years.

YEAR

PRESIDENT

TERM

TIME OF TERM SERVED

REASON

1841

Harrison

1st

31 days

Natural death

1850

Taylor

1st

1 year, 4 months

Natural death*

1865

Lincoln

2nd

42 days

Assassination

1881

Garfield

1st

7 months

Assassination

1901

McKinley

2nd

6 months

Assassination

1923

Harding

1st

2 years, 5 months

Natural death

1945

Roosevelt

4th

3 months

Natural death

1963

Kennedy

1st

2 years, 10 months

Assassination

1974

Nixon

2nd

1 year, 7 months

Resignation

Which presidents failed to serve out their terms?

* Although a handful of scholars contend that Taylor was poisoned, this is not the consensus view.

Source: historyinpieces.com

Trump could also quit the job for reasons other than the pressure of impeachment — deciding he wanted to spend more time at Mar-a-Lago, for instance. But American elected officials have generally held onto their jobs even when things are going pretty badly. Among U.S. governors since 2000, for example, I could find only one case — Alaska’s Sarah Palin in 2009 — of someone who resigned her position early without being in the midst of a major scandal or having another political job (such as an ambassadorship or Cabinet position) already lined up.

YEAR

STATE

GOVERNOR

REASON

2000

Missouri

Mel Carnahan

Died in office

2000

Texas

George W. Bush

Elected president

2001

Massachusetts

Paul Cellucci

Diplomatic appointment

2001

New Jersey

Christine Todd Whitman

Cabinet appointment

2001

Pennsylvania

Tom Ridge

Cabinet appointment

2001

Wisconsin

Tommy Thompson

Cabinet appointment

2003

California

Gray Davis

Recalled

2003

Indiana

Frank O’Bannon

Died in office

2003

Utah

Mike Leavitt

Cabinet appointment

2004

Connecticut

John G. Rowland

Scandal

2004

New Jersey

Jim McGreevey

Scandal

2005

Nebraska

Mike Johanns

Cabinet appointment

2006

Idaho

Dirk Kempthorne

Cabinet appointment

2008

New York

Eliot Spitzer

Scandal

2009

Arizona

Janet Napolitano

Cabinet appointment

2009

Kansas

Kathleen Sebelius

Cabinet appointment

2009

Utah

Jon Huntsman Jr.

Diplomatic appointment

2009

Illinois

Rod Blagojevich

Impeached & removed from office

2009

Alaska

Sarah Palin

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

2010

West Virginia

Joe Manchin

Elected to U.S. Senate

2015

Oregon

John Kitzhaber

Scandal

2017

New Hampshire

Maggie Hassan

Elected to U.S. Senate*

2017

South Carolina

Nikki Haley

Diplomatic appointment

2017

Alabama

Robert Bentley

Scandal

Which governors left office early?

* Hassan’s term was ending and she left office only three days early.

Source: Wikipedia

There’s also the prospect of Section 4 of the 25th Amendment being invoked against Trump, which would make Vice President Pence the acting president if Trump were “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” But this isn’t the shortcut that it might seem. Under the 25th Amendment, Trump could be replaced on an interim basis if both Pence and a majority of Cabinet officers agreed that he were unfit for office. But if Trump disputed the finding, it would require a two-thirds majority of both chambers of Congress to keep Trump from returning to the Oval Office.

So let’s talk about impeachment. Although if we’re being more precise, impeachment doesn’t remove a president from office; conviction on impeachment charges does. Just to be clear about our terminology:

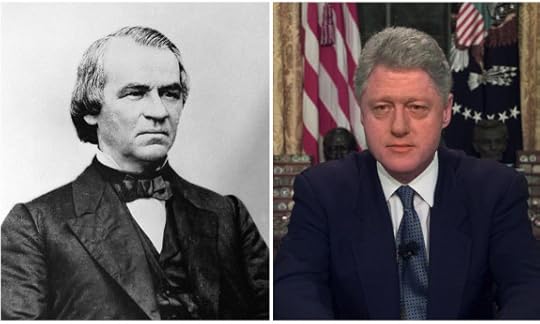

Impeachment is the sole authority of the House of Representatives and requires a simple majority vote. Presidents Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton were impeached by the House.

The Senate then holds an impeachment trial and essentially acts as the jury, voting on whether or not to convict the president and remove him from office; it takes a two-thirds majority (67 of 100 votes) to do so. Neither Johnson nor Clinton was convicted by the Senate, although it came down to one vote in Johnson’s case. The Senate can also vote to bar an impeached president from holding office again.

Although no president has been removed from office, Nixon resigned under the threat of removal, and he probably would have been removed in the absence of his resignation. So he should probably count as a “victim” of the impeachment process.

Even so, that’s only 1 of 44 previous presidencies — and 1 of 57 previous presidential terms — to end in the president’s termination. Therefore, you might think the chance of Trump being removed from office is very low. But it’s not that simple.

The issue is that among the 44 prior presidents, not all that many were plausible candidates for impeachment and removal; there was never any real basis to impeach Dwight Eisenhower, for instance. Instead, the relevant question is how many presidents were removed from office (or compelled to resign) out of the share of presidents who engaged in behavior comparable to Trump’s. If only Trump and Nixon had reached a certain level of “impeachability,” for instance, then the empirical evidence wouldn’t be comforting for Trump; rather, it would suggest that the only president who previously reached that threshold of malfeasance had lost his job.

Presidents Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton were impeached by the House.

Getty Images

To provide evidence against Trump being removed, the data would instead have to contain examples of presidents who could have been removed from office, but weren’t. For instance, it might be relevant that there were never serious efforts to impeach Ronald Reagan for the Iran-Contra scandal. In fact, the Democratic leadership in Congress went somewhat out of their way to avoid actions that could lead to impeachment proceedings against Reagan. Why was that, exactly? One could come up with a variety of plausible theories: that the scandal wasn’t severe enough; that Reagan wasn’t personally involved enough; that Reagan’s popularity insulated him from impeachment; that Reagan enjoyed good relations with Congress at a period of relatively low partisanship, and so forth.

In a perfect world, we’d have data on hundreds of presidents, a few dozen of whom had been impeached. That would let us statistically identify the various factors that made a president more or less likely to survive the process. In the real world, the best we can do is make some educated guesses. Based on the precedents we have available — and our overall knowledge of the American political system — I would expect the following factors to be important in determining a president’s likelihood of removal or resignation:

The seriousness of the alleged offenses. Does the president’s behavior fall under the constitutional category of “high crimes and misdemeanors?” Have similar behaviors been the basis for impeachment proceedings in the past?

The partisanship of pivotal votes in Congress. How much partisanship is there in Congress? Other things held equal, how likely is the decisive 67th senator to vote to remove a president from his own party?

The president’s popularity. What are the president’s approval ratings? Does the public think he should be impeached? Has there been a “mandate” delivered by midterm elections or special elections? What do his numbers look like in states and congressional districts where members of Congress are on the fence about how to vote?

The president’s relationship with Congress. Does the president generally have good relations with congressional leadership? Is his party’s legislative agenda intact? Does Congress feel as though the balance of power has been upset? Is the president cooperating with investigations into his conduct, or antagonizing Congress instead?

Party control of Congress. Which party controls the House and — less importantly for impeachment purposes — the Senate?

The line of succession. Who would take over for the president? Do leaders of the president’s party regard the replacement as an acceptable — or even preferable — alternative to the president?

Let’s consider each of these factors in Trump’s case.

Factor 1

The seriousness of the alleged offenses

Nixon resigned under the threat of removal — and he probably would have been removed in the absence of his resignation.

getty images

In 1970, Gerald Ford (then a U.S. representative, and later the president) said rather cynically that “an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers [it] to be at a given moment in history.” While impeachment is undeniably a political process rather than a legal one, Ford’s interpretation is probably too reductionist. Congress has historically used its powers somewhat judiciously and drawn fairly fine distinctions between different grounds for impeachment.

In 1974, for instance, the House Judiciary Committee recommended impeachment for Nixon on three charges — obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress. But it overwhelmingly rejected recommending impeachment on two other charges related to Nixon’s bombing of Cambodia and his failure to pay taxes. Similarly, in 1998, the House impeached Clinton on two charges — perjury and obstruction of justice — but it rejected an abuse of power charge by a 148–285 margin.

It’s perhaps also noteworthy that neither George W. Bush nor Barack Obama was subjected to serious attempts at impeachment despite facing highly partisan opposition in Congress. They might have done lots of things their adversaries disliked, but nothing that House Speakers Nancy Pelosi, John Boehner and Paul Ryan were willing to call a firing offense.

That’s not to say the correlation between the inherent “impeachability” of the president’s conduct and Congress’s likelihood of action has been perfect, by any means. Congress may exaggerate or underplay the severity of charges for partisan reasons — many scholars argue that Clinton and Johnson’s impeachments were overreaches of congressional power, for instance. But the underlying facts of the case have mattered to some extent.

Neither George W. Bush nor Barack Obama were subjected to serious attempts at impeachment despite facing highly partisan opposition in Congress.

Getty images

So what does that mean for Trump? The Constitution provides that, “The president, vice president and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” While liberals and anti-Trump Republicans have sometimes accused Trump of “treason” for his dealings with Russia, he almost certainly hasn’t committed treason by the letter of the Constitution.

The good news for Trump ends there, however. While the term “high crimes and misdemeanors” might seem hopelessly vague, it has a fair amount of legal history and is generally regarded as referring to political crimes (“crimes against the state”) as opposed to personal affairs. A drunk driving conviction might not qualify as a “high crime,” for instance. But an action that wasn’t illegal per se but reflected an abuse of the president’s office could count as one. That Trump almost certainly did not commit a criminal offense in reportedly disclosing highly classified information to Russia would not necessarily protect him from an impeachment charge on those grounds, for example.

But the bigger problem for Trump is probably Comey, in that firing him might have constituted obstruction of justice. Obstruction of justice is about the last accusation that a president wants on his radar if he fears impeachment; it was one of the two charges that the House used to impeach Clinton and one of the three charges that the House Judiciary Committee recommended against Nixon.

One more thing to keep in mind: The Trump presidency is only four months old. Congress has yet not done all that much to investigate his affairs, and special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Trump’s ties to Russia was just announced last week — and yet Trump has already gotten himself in quite a lot of trouble. What might seem like tenuous reasons for impeachment now could could turn out to be just the tip of the iceberg.

The bottom line: If Congress is looking for reasons to impeach Trump, it already has some plausible ones — and it will probably wind up with more before long. This factor substantially contributes to the likelihood of Trump being removed from office.

Factor 2

The partisanship of pivotal votes in Congress

President Trump talks with Rep. Peter King (R-NY) after addressing a joint session of Congress in February.

Getty images

Congress is at a high tide in terms of both partisan polarization and ideological division. FiveThirtyEight’s Trump Score shows that in the House, the average Republican has sided with Trump 97 percent of the time on votes on which the White House has articulated a position; the average Democrat has done so only 15 percent of the time. (The discrepancy has been nearly as wide in the Senate.) And according to the statistical system DW-Nominate, the ideological gap between the parties has continued to widen; Democrats have gotten more liberal and (to an even greater extent) Republicans have gotten more conservative.

While measures such as DW-Nominate and our Trump Score have their imperfections, my colleagues Julia Azari, Perry Bacon Jr. and Harry Enten found that they historically provided a pretty good guide to impeachment voting patterns. In other words, it’s reasonable to infer that because Congress is highly polarized on almost every other issue, it probably also would be polarized on impeachment and removal votes. This would seem to have three major consequences for Trump:

It makes impeachment less likely in the near term, because Republicans control the House.

It makes impeachment (but not Trump’s removal from office) more likely if Democrats take over the House in 2019. Partisanship might compel Democrats to impeach Trump even if the political or legal rationale for doing so is dubious.

Most importantly, it makes Trump’s removal from office much less likely, other factors held equal. Even if all 48 Senate Democrats voted to remove Trump, they’d also need support from 19 Republicans to get to a two-thirds majority. That would require dipping far into the Republican ranks — well past the few moderates in the Senate — and the decisive 67th vote would have to come from a fairly conservative Republican like Missouri’s Roy Blunt or South Dakota’s John Thune instead. This isn’t going to change much in 2019, even if Democrats have a great midterm election.

At the same time, we shouldn’t conclude that partisanship provides Trump with absolute protection against removal from office. As an empirical matter, we don’t have much data on what factor would win out if the case for impeachment were very strong (say, if Mueller uncovered that Trump had accepted bribes from Russia) but partisanship were also very high.

There’s also some question as to where partisanship might lead congressional Republicans if they conclude that a Trump presidency isn’t in the best interests of the GOP. Trump hasn’t been a Republican for all that long, and it isn’t clear how invested he is in the Republican agenda or how competent he is to execute it. Republicans have a poor track record of standing up to Trump, but during the election campaign, the alternative was either to invite chaos (since Marco Rubio and other candidates weren’t clicking with voters) or to elect Hillary Clinton. Now their alternative is Pence — or Ryan if Pence were also impeached. A lot of Republican members of Congress might view Pence or Ryan as an upgrade on Trump.

The bottom line: Partisanship is the biggest protection that Trump has against impeachment. If you see Republicans start to break with Trump in more substantive ways, such as by launching special committees or holding up his replacement for Comey, he might have more reason for concern. But overall this factor substantially reduces the likelihood of Trump being removed from office.

Factor 3

The president’s popularity

Patrons at a bar watching the Iran-Contra hearings. Reagan had an approval rating of around 50 percent even after the Iran-Contra scandal was revealed. Democratic efforts to impeach him could easily have wound up backfiring.

Getty images

Members of Congress are loyal to their president, but there’s one thing they usually care about even more: their own re-election. Presidential popularity has a strong influence on congressional races. Beyond a certain point, a president can become toxic enough that it’s in the interest of members of his own party to abandon him. Nixon, for instance, had an approval rating in the mid-20s at the time of his resignation in 1974. Republicans endured a 48-seat loss in the House even after he resigned. But they might have taken an even worse loss if he’d stayed in office. Based on my colleague Harry Enten’s formula, Republicans would have expected to lose around 60 seats if Nixon were still president, given his approval rating.

By contrast, Reagan had an approval rating of around 50 percent even after the Iran-Contra scandal was revealed. Democratic efforts to impeach him could easily have wound up backfiring. Twelve years later, Republicans learned this the hard way, losing House seats in the 1998 midterms in the midst of their attempt to impeach Clinton, whose approval rating exceeded 60 percent.

Trump’s popularity is in a somewhat awkward middle ground. With an approval rating of about 39 percent, he’s no Clinton or Reagan. But he isn’t late-stage Nixon, either. Trump is not very popular, but he was never all that popular to begin with and won the Electoral College despite it. It’s not clear that all that many voters have regrets about their decision to vote for Trump, at least not yet. And few polls have asked voters whether they think Trump should be impeached.

At the same time, the idea that 39 or 40 percent of the country will never abandon Trump is probably mistaken — or at least, it represents a speculative interpretation of the evidence. The share of voters who say they strongly support Trump is only 20 to 25 percent — and those numbers have been falling. Moreover, Trump has lost about one point off his overall approval rating per month. That might not sound like a lot, but if the pattern continued, he’d be in the low-to-mid 30s by the new year and into Nixonian territory by the midterms.

There are a couple of further complications. One issue is that while Trump is fairly unpopular overall, his numbers are holding up better in red states — and red-state senators represent the pivotal votes for Trump’s removal from office. The table below reflects my estimate of Trump’s current approval rating in each state based on recent state-by-state approval-rating polls and the 2016 and 2012 election results.

STATE

APPROVAL RATING

DISAPPROVAL RATING

STATE

APPROVAL RATING

DISAPPROVAL RATING

1

Hawaii

26%

68%

26

Arizona

42%

52%

2

Vermont

28

66

27

Ohio

42

52

3

Calif.

28

66

28

Iowa

42

52

4

Maryland

29

65

29

Georgia

42

51

5

Mass.

29

65

30

Texas

44

49

6

N.Y.

30

64

31

S.C.

45

48

7

R.I.

32

61

32

Alaska

46

48

8

Illinois

33

61

33

Mississippi

46

47

9

Washington

34

60

34

Missouri

47

47

10

N.J.

34

60

35

Indiana

47

47

11

Conn.

34

60

36

Montana

48

46

12

Delaware

35

59

37

Louisiana

48

46

13

Oregon

35

58

38

Kansas

48

45

14

N.M.

36

57

39

Nebraska

50

44

15

Maine

37

56

40

Tennessee

50

44

16

Colorado

38

56

41

Utah

50

43

17

Virginia

38

56

42

Arkansas

50

43

18

Nevada

39

55

43

Alabama

51

43

19

Minnesota

39

55

44

S.D.

51

43

20

Michigan

39

55

45

Kentucky

51

42

21

N.H.

39

55

46

N.D.

53

41

22

Wisconsin

39

54

47

Idaho

53

41

23

Penn.

40

54

48

Oklahoma

54

39

24

Florida

40

54

49

W.Va.

55

38

25

N.C.

41

53

50

Wyoming

58

35

Estimating approval and disapproval of Trump by state

These estimates are based on a regression analysis, where the independent variable is the Republican margin of victory or defeat in the 2016 and 2012 presidential elections, weighted 3:1 in favor of 2016. The dependent variable is Trump’s approval rating (or disapproval rating) in each state, based on state-by-state approval rating polls conducted within the past two months (since March 20), as listed at PollingReport.com and Wikipedia. State-by-state estimates are calibrated such that Trump’s overall numbers, weighted by the number of voters in each state, are a 39 percent approval rating and a 55 percent disapproval rating, matching his national approval and disapproval ratings as of Saturday morning.

If voting in the Senate strictly abided by Trump’s popularity, the 67th vote to remove Trump from office would come from Missouri. (Two-thirds of states are bluer than Missouri and one-third are redder.) But in Missouri, I estimate, Trump’s numbers are roughly breakeven, with about 47 percent of Missourians approving of his performance and 47 percent opposed. I wouldn’t expect Missouri’s senators, Blunt and Democrat Claire McCaskill, to be eager to kick Trump out of office under those circumstances.

Another issue is that it might be a leap of faith for Republicans to impeach Trump on the basis of polling data, given that trust in polls is relatively low right now. I have some … complicated feelings about this. The mainstream media screwed up its interpretation of polls throughout 2016, misreporting surveys that showed a close and competitive Electoral College race as indicating surefire Clinton victory. At the same time, polls have a real-world margin of error that exceeds their purported margin of error, and Trump’s numbers are slightly better among people who vote than they are among the country overall. Congress could wait for unambiguous evidence that the public had turned on Trump, whether in the form of very poor polling numbers (say, approval ratings in the low 30s) or inexcusable election results (such as in the upcoming special elections in Montana and Georgia, or in a big Republican loss at the midterms). Until we see one or both of those things, I wouldn’t expect Trump to be under that much pressure of impeachment.

The bottom line: For the time being, this factor contributes only modestly to the likelihood of Trump being removed from office. Trump is unpopular, but his numbers are not unsalvageable (several presidents have come back from similar ratings to win a second term). A further deterioration in his popularity would imply that he is unpopular even in red states, however, and would greatly increase the risk to Trump.

Factor 4

The president’s relationship with Congress

The House impeachment committee that tried President Andrew Johnson after he removed Edwin Stanton from office.

Getty images

This is not a factor that I’d thought a lot about originally. But when you review the scholarship on impeachment and consider the historical evidence, its importance becomes obvious. Impeachment cases have usually involved an element of conflict between the president and the legislative branch.

This is most obvious in the case of Johnson, whose impeachment was the result of a plain-old turf war with Congress. In 1867, Congress had passed something called the Tenure of Office Act, which was supposed to prevent the president from firing Cabinet officers without the Senate’s consent. Johnson fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton anyway in a direct challenge to the act’s legitimacy. The House impeached him as a result. The Tenure of Office Act was later repealed — and in 1926, posthumously declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court — but it had invited a confrontation with Johnson, and he had obliged.

Contempt of Congress was also one of the articles of impeachment that the House Judiciary Committee recommended against Nixon after he failed to cooperate with congressional subpoenas during the Watergate investigation. And pissing matches between the president and Congress have been the basis of some near-misses in the impeachment process; there were some fairly serious attempts to impeach John Tyler over his use of presidential vetoes, for example.

For the time being, Trump has a cordial relationship with Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. (Though that hasn’t always been the case.) The GOP still has hopes of passing major legislation, including health care and tax-reform bills, and that requires cooperation between the White House and Congress. But one can imagine Trump doing various things to antagonize Congress, from Twitter rants against congressional leadership to refusing to comply with the requests of congressional investigators. Firing Comey — who was confirmed 93-1 by the Senate in 2013 — may also have been a risky move in this respect. From Johnson to Harry Truman — who drew calls for impeachment after dismissing General Douglas MacArthur in 1951 — high-profile firings have sometimes prompted members of Congress to ask for the president’s head.

The bottom line: For the time being, this factor doesn’t contribute much to the likelihood of Trump being removed from office. But Trump’s history of escalating conflict and failing to respect boundaries could antagonize Congress and contribute to the likelihood of impeachment in the future, especially if the GOP’s agenda is in disrepair. History suggests that Congress takes that stuff personally, and it probably should, since the impeachment process is part of the Constitution’s system of checks and balances.

Factor 5

Party control of Congress

Impeachment proceedings against Johnson, Nixon and Clinton all took place when the opposition party controlled the House. Carl Albert (above) was the speaker of the House while the Watergate scandal was unfolding.

getty images

Impeachment proceedings against Johnson, Nixon and Clinton all took place when the opposition party controlled the House. But is it something close to an ironclad rule that a president won’t be impeached when his party runs the House, or just a statistical pattern from a small sample of data?

Imagine, for example, that by this point next year, almost all Democrats in the House want to impeach Trump, and so do about three dozen Republicans — enough to constitute an overall majority. But Republicans are still in charge of the House, and Ryan and other members of the leadership are firmly opposed to an impeachment vote. Moreover, the House Judiciary Committee — which has traditionally run point on the impeachment process — is opposed. Would the pro-impeachment members have any basis to force Ryan’s hand?

The short answer is … maybe, but Ryan and company could make their task a lot harder. I asked Sarah Binder, a professor of political science at George Washington University and a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution, about what might happen if a narrow majority of Congress wanted to impeach Trump but the Republican leadership didn’t.

“This is one of those cases where we can outline a set of procedural steps to an impeachment vote, and yet have a hard time actually seeing this happen,” Binder said in an email. Possible routes could include members of Congress raising questions of privilege or filing a discharge petition. “But the key is whether the cross-party impeachment majority would really stick together” through numerous procedural votes and barriers thrown up by Ryan, she said. “I think that’s a very steep hurdle.”

One might raise a sophisticated objection here: Sure, control of the House could matter if there were only a narrow majority in favor of impeachment. But what if there were a large majority instead — enough that Trump was not only under threat of impeachment but also removal by a two-thirds vote in the Senate? Could Ryan & Co. really resist that kind of pressure?

We’re deep into speculative territory, but it’s worth remembering that legislative voting tactics are complicated. Members of a party tend to stick together, until the wheels come off — and even then the wagon sometimes gets repaired again. Consider, for instance, how the Republicans’ health care bill was initially presumed to be almost certain to pass the House, then was pulled from the floor in March, and then was passed this month as both moderates and the conservative Freedom Caucus returned to the fold.

It’s plausible, in other words, that Ryan and the House Judiciary Committee could keep the impeachment genie in the bottle, even if impeachment would prevail by a fairly clear majority if a vote came to the floor and members were left to their own devices.

Control of the Senate is less important, insofar as the Senate would have to try the impeachment charges whether or not they wanted to. And per the Constitution, the trial would be overseen by Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts rather than by the Senate leadership.

The bottom line: A Democratic takeover of the House — perhaps an even-money proposition — is not quite a prerequisite for Trump’s impeachment and removal, but it would greatly increase the odds. It would also give the Democrats far greater powers to investigate Trump and to subpoena key materials, which could create additional bases for impeachment charges.

Factor 6

The line of succession

Pence in next in line. Then comes Ryan.

Getty images

In 1868, Republicans in Congress had the power to replace Andrew Johnson, a Democrat who had run with Abraham Lincoln on the National Union ticket, with a Republican president. And there was absolutely nothing Democrats could do about it.

The circumstances were unusual. Johnson had ascended to the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination, and the vice presidency was vacant. Instead, the line of succession would have given the presidency to the Republican Benjamin Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate. Republicans had an overwhelming majority in the Senate in the midst of Reconstruction, so they didn’t need any Democratic votes to convict Johnson and replace him with Wade.

Republicans didn’t quite do it; instead the vote was 35-19 in favor of conviction, one short of the number needed. But the prospect of a Wade presidency was an influential factor in determining senators’ votes, encouraging Radical Republicans to vote to convict Johnson (since Wade was a fellow Radical) but discouraging moderates from doing so.

While Johnson may have been an extreme case, it’s reasonable to assume that the identity of the president’s successor is a factor in the impeachment calculus. Pence is more conservative than Trump and was widely praised by GOP leaders at the time he became Trump’s running mate; he’s also a more predictable politician than Trump and formerly held a leadership position in the Republican-led House. He also has decent favorability ratings, at least for the time being. In short, Republicans have some reasons to prefer Pence to Trump, which could make removing Trump more palatable. (Of course, that’s assuming that Pence isn’t implicated in any sort of scandal himself.)

The bottom line: If the theory is that you shouldn’t hire a well-qualified understudy because he makes your job more vulnerable, then Trump made a mistake in picking Pence as his running mate. Pence isn’t popular with everyone, but he’s likely to be broadly acceptable to Republicans in the House and Senate, and they’re the ones with impeachment votes. Articles like this one, in which Republicans begin to “whisper” about the probability of a President Pence, should be seen as a bearish indicator for Trump.

Trump’s firing of Comey might have constituted obstruction of justice, one of the two charges that the House used to impeach Clinton and one of the three charges that the House Judiciary Committee recommended against Nixon.

getty images

All that work … and I’m still not going to give you a precise number for how likely Trump is to lose his job. That’s because this is a thought experiment and not a mathematical model. I do think I owe you a range, however. I’m pretty sure I’d sell Trump-leaves-office-early stock (whether because of removal from office or other reasons) at even money (50 percent), and I’m pretty sure I’d buy it at 3-to-1 against (25 percent). I could be convinced by almost any number within that range.

The easiest-to-imagine scenario for Trump being removed is if Republicans get clobbered in the midterms after two years of trying to defend Trump, the Republican agenda is in shambles, Democrats begin impeachment proceedings in early 2019, and just enough Republicans decide that Pence (or some fresh face with no ties to the Trump White House) gives them a better shot to avoid total annihilation in 2020.

In some sense, then, the most important indicators of Trump’s impeachment odds are the ones you’d always use to monitor the political environment: presidential approval ratings, the generic congressional ballot and (if taken with appropriate grains of salt) special election results. What makes this time a little different is that if Republicans think the ship is sinking, impeachment may give them an opportunity to throw their president overboard first.

CLARIFICATION (May 22, 1:33 p.m.): A previous version of this article described imprecisely Rep. Angus King’s comments about Trump’s impeachment prospects. The paragraph has been updated.

May 17, 2017

Emergency Politics Podcast: The Comey Memo

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

New to podcasts?

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew assesses the fallout from reports that President Trump asked then-FBI director James Comey to end the bureau’s investigation of former national security adviser Michael Flynn. Trump’s request was reportedly detailed in a memo written at the time by Comey.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

May 16, 2017

Have Trump’s Problems Hit A Breaking Point?

In this week’s politics chat, we do an appraisal of the White House. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): So … where to start? I won’t run through all the things that have happened this week in detail, but here’s a summary from Dafna Linzer at NBC News:

Last seven days: pic.twitter.com/iA5Io6HgqA

— Dafna Linzer (@DafnaLinzer) May 16, 2017

And then after all that, The New York Times reported late Tuesday that President Trump asked James Comey, when he was FBI Director, to end the Michael Flynn investigation (according to a memo apparently written by Comey at the time).

We’ve talked before about whether Trump’s campaign, then President Trump’s administration, were in “disarray.” Usually, the answer is “yes,” and then the crisis (or crises) subside, there’s a period of calm, then it all starts over again. But today let’s talk “Is the Trump administration irreparably damaged?” — the idea we’re trying to get at is some combination of: Are things spinning out of control? Is the White House sustaining lasting damage? Or, does the disarray have momentum?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): So, I started thinking about this yesterday during the podcast taping with an expert in scandals that we had on (the best academic pursuit.) And to me the key question here is always: How will the American public ultimately respond to this? In scandals gone by, politicians were concerned about what people’s long-term view of a scandal might be. In theory, that’s right — what is the public’s ultimate takeaway? But I keep wondering whether or not the frenzied pace at which scandals occur now in some way blunts the impact of each one?

Or is this line of thinking too postmodernist (or something?)

A bit off-topic, but that’s the framework I tend to think about these things in.

micah: No, I think that’s the central question.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Here’s the problem as far I’m concerned: trust, among the public and the media. If I hear a statement from one of Trump’s spokespersons or someone representing the administration, I don’t believe it. How many times have we seen the administration reverse itself? We saw it with Michael Flynn. We saw it with Comey. We see it now with H.R. McMaster and Trump. The trust deficit is part of what crushed Hillary Clinton’s campaign. It seems very difficult to build back up trust once there’s a deficit.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I’m normally skeptical of events in the news cycle being overhyped. But I think this is pretty bad for Trump. His worst sequence during either his campaign or his presidency so far, with the possible exception of the Access Hollywood tape and its subsequent aftermath.

micah: The asking-Comey-to-shut-down-the-Flynn-investigation thing seems like a huge development, right?

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Good god. This seems really big. It is closer to actual obstruction of justice.

natesilver: I mean … what is there to say? It’s really bad news for Trump that Comey has seemingly created an extensive paper trail of their conversations. This is the sort of thing that would be the basis for impeachment. And at a minimum, the drip-drip-drip of leaks from Comey, and other people in the intelligence community, is going to create a lot of “distractions” for Trump from his ability to pass his agenda.

clare.malone: This is why it’s hard to fire lawyers. Like, legit. On any level — these people are trained to keep paper trails!

perry: It seems like firing Comey may have been worse than just letting Comey investigate Trump’s connections to Russia. This was a huge political mistake, even aside from the ethics of it and the violation of norms.

clare.malone: Yeah. It does seem more and more like a decision that came to Trump out of pique and then was justified by the people around him. The latter part is more fascinating to me still — why they let him do that?

perry: Still, we should be careful about predicting permanent damage to Trump after all that happened in the campaign. Or to say the disarray has momentum and is permanent. What if the health care bill passes in 6-8 weeks?

clare.malone: The campaign thing is really fair to point out, but then the next question to ask is whether the office of the presidency being involved colors things differently. With this scandal — national security being massively disrupted, potentially — that’s something that’s really different from the campaign scandals.

natesilver: It’s sort of a myth that Trump was impervious to damage in the campaign. A lot of the things that people expected to damage him did damage him, at least during the general election. He got elected despite having only about a 38 percent favorability rating for a variety of somewhat quirky circumstances. And during the campaign, he had the benefit of having Clinton as his foil — and she was capable of her own screw-ups, obviously.

I’m not sure there’s anything comparable when you’re president — you’re sort of running against yourself.

harry: Basically, Nate is talking about this.

perry: I’m not saying these controversies don’t matter politically. But winning the presidency is obviously something. Getting a huge health care bill passed would be something. If you can govern and pass big bills, that is the point of being president.

So I guess we maybe should make a distinction between politics (big effect) versus policy (not as sure).

micah: Yeah, let’s separate things that way … politics first …

Do the Comey scandal, the classified info scandal, the latest Times report, etc. do lasting damage to the GOP’s prospects in 2018, and Trump’s re-election chances?

harry: Each is another building block.

clare.malone: I think they do damage. Let’s think of say, those reluctant Trump voters in the suburbs — they might not think that the long-simmering Russia investigation was actually a big deal, but I think if you were a skeptical Trump voter keeping an eye on these things and the accumulating chaos, you’re not exactly thrilled, right? You might not want to abandon him yet, but the chain of events and chaotic scene isn’t great.

natesilver: Soooo … my short answer to that, Micah, is “yeah, sure,” but I’m also not sure it’s quite the right way to be thinking about the question.

micah: What’s the right way?

natesilver: Like, what if firing Comey causes a bunch of people in the intelligence community to turn hostile to Trump, and as a result, some other scandal is exposed that wouldn’t have been exposed otherwise, and that scandal costs him the presidency or gets him impeached?

Or … what if as a result of spilling the beans to Russia, the State Department is less willing to share secrets with Trump, and as a result of his being less knowledgeable, he screws up some foreign policy crisis when he might have done OK otherwise?

micah: So it seems like you would answer our original question in the affirmative, right? The Trump scandals build on themselves.

natesilver: I might posit a semantic difference between “building on themselves” and “having consequences that could persist for months or years.” But basically, yeah.

micah: Right. I mean, the news about Trump asking Comey to stop the Flynn probe was a result of the Comey firing scandal.

Perry, Clare, Harry — you all agree?

clare.malone: The long-term narrative of investigations, scandal, etc., is bad for the voters who were already most on the edge about Trump but who voted for him.

So, yeah.

micah: haha.

clare.malone: But I wanted to say it MY WAY.

natesilver: Yeah — and those marginal/reluctant Trump voters are more important to Trump’s future than Trump’s more devoted base.

harry: Well, yes. But I think we’re thinking about it in somewhat different ways. I don’t think there needs to be any more foreign policy or intelligence fallouts for this to hurt him in the long term. But these scandals probably won’t be the key things remembered if nothing else comes from them, either. It’s part of a long string, which is why this stands out.

perry: Lasting damage to his reelection chances, from the last week? I don’t know. I think his reelection chances were already complicated by his terrible approval ratings. But no, this does not help. I have to say these two words, however: Access Hollywood.

harry: BRB, going to investigate some Trump voters at GOP HQ and see what they think. #realamerica

natesilver: 100 percent of Trump supporters support Trump, according to our reporting.

harry: Agree with Perry. This is Day Two of this new “scandal” or whatever we’re calling it. Maybe it’s Day One. Who knows what else we might find out by Friday?

natesilver: The thing is — while you can maybe portray the Comey firing as being consistent with Trump’s brand, the “sharing state secrets about ISIS with the Russians” thing really isn’t.

clare.malone: OK, how about this:

A lot of whether or not this has lasting effect in the public mind depends on the Democrats. The Republicans were able to make Clinton’s emails the talking point for months and months and months. If the Democrats were able to rhetorically weaponize these series of connected scandals, then I think they do have the potential for real lasting effect.

natesilver: There’s more conflict in this chat than usual. I’m pretty much on Clare’s side.

micah: FIGHT!

perry: Hmm. What is the disagreement?

micah: Perry, don’t ruin it.

clare.malone: Fighting is good in this family, Perry.

harry: I love all of you.

clare.malone: Your shoes are ugly.

perry: I just missed it.

clare.malone: We’re yellers.

micah: We’re trying to hype conflict to sell papers!

clare.malone: Perry, you don’t think the recent scandals have lasting effect, right? Or it’s too soon to know?

perry: I like disagreement. I’m just not sure I disagree with much here. I think these controversies could be damaging.

natesilver: I guess I’m just saying (and I think Clare is saying?) that the “this is probably bad news for Trump” outweighs the margin of uncertainty, so to speak.

clare.malone: Right.

perry: Of course it’s bad news for Trump. But whether it is permanently damaging is a different question.

clare.malone: Right. I think Nate and I are leaning on the side of, this likely is long-term bad.

perry: Can he win re-election after this week? I would say maybe. I assume you guys agree?

micah: Yeah.

clare.malone: If we’re talking about whether or not these are going to have long-term effects, it comes down to whether or not they start to be chinks in the bond between Trump and certain Republicans who always had at least a glimmer of skepticism about him.

natesilver: Right, that’s the way to measure it.

clare.malone: They are kind of the congressional stand-ins for those reluctant Trump voters.

natesilver: The Comey firing and the intelligence slip are both the sort of thing that could be grounds for impeachment, if Congress were so inclined, though.

perry: They are huge policy matters. They are huge violations of political norms. I’m just not sure they fundamentally alter the politics of the country, which are very divided, but with Trump being very unpopular, Democrats favored in 2018 and I have no idea what happens in 2020.

natesilver: One way this week has been damaging for Trump is that it makes impeachment proceedings very likely if Democrats take over the House in 2019.

perry: So that is a great point. And that is something I should have been considering during this chat.

natesilver: (To be clear, impeachment proceedings are not the same thing as the House voting for impeachment, much less the two-thirds of the Senate voting to convict….)

harry: Chris Stirewalt at Fox News had an excellent writeup of this. The idea being that what Trump is doing now isn’t making impeachment any more likely in the next year or so, but 2019 is when the action could begin.

clare.malone: But let’s theorize and say that a small number of concerned Republican senators band together after a few months of what they consider to be illiberal tendencies in the president and decide to do something (I don’t know what). Don’t moves or waves of feeling like that within the Republican establishment ultimately lead to the potential for, say, a decent intraparty challenge in 2020? (To get a lil cray.)

natesilver: So, if Democrats take over the House, 2019 could be a very interesting year. Democrats are holding impeachment hearings, and at the same time, the “invisible primary” for the 2020 GOP nomination is getting underway. Might some Republicans decide that they’re better off with Vice President Mike Pence than with Trump? Or some alternative to both Pence and Trump?

clare.malone: Yeah, Pence.

micah: Ehhh, I don’t see any evidence or rumblings of that level of Trump-abandonment at all. (As of Tuesday at 6 p.m. Eastern.) Remember, if the GOP establishment isn’t behind Trump he cannot win the nomination in 2020. See: “The Party Decides.”

Speaking of:

Sen. Sanders will debate Gov. John Kasich tonight on CNN. Tune in at 9 ET! #DebateWithBernie pic.twitter.com/KrDhsjZjuo

— Bernie Sanders (@SenSanders) May 16, 2017

clare.malone: That guy has been really smart by staying out of the news, if I may say.

micah: John Kasich?

clare.malone: lol. No, Pence.

micah: I was gonna say …

clare.malone: Kasich is basically licking TV lenses.

harry: Two things: 1. If you watch Sanders vs. Kasich, you probably need a life more than I do. 2. The No. 1 thing to watch for as to whether there will be a primary challenge to the sitting president is his approval rating. Trump’s approval rating is low enough that, for a generic president, we’d expect a primary challenge.

natesilver: FWIW, the Senate can also vote to bar someone from holding office in the future if they’re impeached. The baller move for Trump is if he resigned under threat of impeachment in 2019, and then ran for the GOP nomination in 2020 anyway.

clare.malone: Harry, do you have a different metric for how low Trump would have to sink to get a challenge?

harry: I don’t know if it’s any different. The fact that perhaps Trump has a higher approval rating among Republicans compared to what you’d expect given his overall approval rating might stave off a challenge for a little bit, but if he gets much below 40 percent it’ll probably happen. (No guarantees.)

natesilver: The lowest someone ever reached in his approval ratings before getting re-elected anyway was Truman, who fell to about 33 percent by a year or two into his (inherited) first term. But in general, I think a 40-ish percent approval rating is recoverable whereas a 30-ish percent one would create massive problems for Trump.

perry: Shifting gears a bit, I actually do think this week may bring a permanent change in how the media and other Republicans view Trump. He did something that violated a big norm, firing the person who is investigating him. The comparisons of him to Richard Nixon were near constant. No one can laugh off that comparison anymore.

The people who write about authoritarian governments will be published more.

natesilver: Yeah, the fact that Trump has repeatedly undercut his own spokespersons is another long-term consequence here.

perry: Harry said this earlier in the chat, but newspapers are going to start publishing stories and basically ignoring White House denials, which are meaningless now.

natesilver: I feel like, in general in my writing on Trump to date — I won’t speak for the rest of the site — I haven’t done enough to play up the consequences of what happens if you have an incompetent president, or perhaps a mentally unstable one. Those are big things to worry about, separate from authoritarianism.

perry: I don’t know which of those three Trump is, but I think all are possibilities,

clare.malone: The New Yorker’s Evan Osnos covers Ronald Reagan/mentally unstable stuff in this piece really well. He gets into how Reagan’s staff were monitoring him and considering possibly invoking constitutional mechanisms to get him out of office.

natesilver: Reagan may have had some issues in his second term, but he also surrounded himself with highly competent people — not something I’m sure you can say for Trump.

People with a lot of defects can get along fine if they hire well.

micah: A little on the nose, Nate.

perry: That is why I think incompetent doesn’t capture well what is going on. Trump could have hired a really strong chief of staff and empowered him. He hired Reince Preibus.

natesilver: Micah is my Reince Preibus.

micah: omg.

perry: Micah is your Howard Baker. Or James Baker. (I’m kidding, but being somewhat serious.)

natesilver: Oops. Yeah, I screwed up the analogy. Micah is one of the Bakers.

perry: Trump doesn’t like managing but also has hired a flawed manager. Or he doesn’t like details.

micah: I’d rather be H.R. Haldeman.

natesilver: Another problem for Trump is that it’s going to be harder for him to hire good people, given how he’s treated the people who have worked for him so far.

micah: For the final bit here, let’s talk about how the past week’s events affect Trump’s agenda. That’s important in that it impacts peoples’ lives, but I think it’s also a good indirect measure of where the administration is.

Do the Comey firing and the Russia/info scandal (we need good shorthand for this) make it harder to enact health care reform?

clare.malone: I like Harry’s theory on this, which I think he’s typing.

perry: Yes, but doesn’t make it impossible. Same for tax reform.

natesilver: Sure, in that passing health care requires Republicans to make a big leap of faith toward Trump, given how unpopular the bill is, and this week will have given them less reason to have faith in him.

clare.malone: Harry’s theory on this (which he’s still typing) is contrarian.

harry: Well, I’m mostly with Nate and Perry here. Everything Trump has done in the last week makes him less likely to be trusted by his own staff. It makes the press less likely to trust anything they say. So to me, it can make an agenda harder to enact.

That said — and I spoke about this on the podcast — the scandals could make it easier to pass less popular legislation because they divert people’s attention. There will be fewer questions about health care because everyone will be asking what the heck is he sharing now with Russia?

natesilver: The scandals also slow down the calendar. Confirming the new FBI director could be contentious, for example. Sen. John Cornyn pulled his name from consideration on Tuesday.

But I would say this: The fact that House Speaker Paul Ryan and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell have been largely forgiving of Trump’s recent problems suggests that they’re still holding out hope of getting some substantive legislation passed.

clare.malone: Yeah, Ryan and McConnell didn’t bat an eye, really, at this.

harry: McConnell did speak out Tuesday morning in a way that was clearly not pleased, given how quiet McConnell normally is.

micah: Yeah, McConnell really came down hard on Trump, Harry. Here’s his blistering quote: “I think we could do with a little less drama from the White House on a lot of things so we can focus on our agenda, which is deregulation, tax reform, repealing and replacing Obamacare.”

natesilver: I don’t think that kind of opposition counts for much unless it eventually turns into hard-and-fast consequences. Which, so far, we haven’t seen.

micah: My default stance on the bulk of Republican officials is: I’ll believe they’re bucking Trump when they take identifiable steps to do so.

So let’s close on this: What’s the standard for Republicans truly checking Trump? It’s definitely not anonymously complaining about the White House to media outlets.

harry: We need to keep an eye on two things. No. 1 is how often senators vote with Trump. No. 2 how many bills get passed? They often won’t bring stuff to the floor if it won’t pass. So the two of those in combination are key.

clare.malone: Once we see people besides Jeff Flake, Lindsey Graham and John McCain be vocal about Trump opposition, then you’ll know if the tide is turning.

Maybe that comes from things like, upcoming, who replaces Comey — what sort of direction you go with that position is key. For example. I wonder if anyone besides Graham types in the Senate would voice opposition to a highly partisan pick.

natesilver: For me, the markers of real GOP pushback would include forming a select committee to investigate Trump-Russia stuff, or failing to confirm a key Trump cabinet nominee.

perry: Yeah, voting down nominees who are problematic. Like Trey Gowdy for FBI director, if that happened. (Although, Gowdy took himself out of the running, too.)

natesilver: Or if we’re looking at anonymous complaining … if we start to see Republicans anonymously suggesting that Trump should resign, that would be meaningful.

perry: Or truly condemning acts that violate norms, like the Comey firing.

And yeah, calling for a special prosecutor or a select committee would be important.

My other measure would be co-sponsoring legislation that takes on some of the business/tax issues around Trump. McConnell/Ryan will never let that stuff get to the floor, but if 150 House Republicans and 30 senators are on a bill calling for Trump to release his taxes, that is something

micah: So things are moving fast, but based on the fact that we haven’t really seen any of that as of Tuesday evening, the GOP is still with Trump.

perry: Oh yes.

May 11, 2017

Will An Anti-Trump Message Be Enough For Democrats In 2018?

In this week’s politics chat, we sift through all the different lessons Democrats are taking from the 2016 election. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): There’s been a sudden resurgence of post-mortems on the 2016 presidential election. So today’s plan is to discuss the various conclusions that have been floating around. But let’s talk through them specifically in regards to what lessons Democrats should learn heading into 2018 and 2020.

Everyone got that?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): jksdfbdsafbskdf

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Sounds like a blast.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): It’s a retreat to move forward, so to speak.

micah: Exactly.

OK, so question No. 1: Lots of people think Hillary Clinton ran too much of an anti-Trump campaign, as opposed to running on an affirmative vision for the country. Do we think that’s true? Do Democrats need a vision for 2018 and 2020? Or can they win just by running against Trump? (With the latest James-Comey-firing imbroglio, for example, there seems like plenty of material for Democrats to run on.)

natesilver: For 2018, an anti-Trump/anti-GOP message should suffice. For 2020, they’ll need that plus something more affirmative.

micah: What makes you say that?

clare.malone: There are governors races in 2018; don’t Democrats need an affirmative message in those?

harry: We do know that Clinton ran a very negative campaign. At least on television. That didn’t work. Or, it didn’t work well enough. Midterms can be very different, however. They’re usually a referendum on the incumbent president. That said, the relationship between a president’s approval rating and the midterm results is not as strong as you might think.

natesilver: PARTIES DON’T HAVE BROAD, SWEEPING VISIONS AT MIDTERMS.

micah: Contract With America.

natesilver: That’s the only example, Micah. Think of another.

Go ahead.

Please proceed, governor.

micah: Democrats ran on an anti-war, anti-corruption message in 2006. That was a pretty consistent message nationally.

clare.malone: What if we’re in a new time, MAKING HISTORY, Nate? Isn’t there room to think that this might be a new paradigm? (Points for buzzword, right?!)

natesilver: You might need an affirmative message if you were running against a super-popular Dwight D. Eisenhower-type of president and trying to make the case for why he needed some constraints on his power anyway. But the Democrats are running against Donald Trump. And Republicans already control both branches of Congress, in addition to the presidency. It’s not a hard argument to make.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): I have never thought that Clinton lost because she lacked a more positive message. Lots of people agreed with Trump’s core message that the country is struggling, Washington needs to be shaken up. And he appealed to cultural/racial concerns in a way that she couldn’t. I’m not sure a more focused economic message, whatever that means, would have won Clinton Wisconsin, for example.

And I think 2006, 2010, 2014 all showed that running largely against the incumbent president is fine for midterms.

natesilver: I’m not sure it’s true either, but I think this topic (whether Clinton needed a more positive message) has actually been a bit under-studied, relative to other causes of Clinton’s defeat. She was a pretty big outlier in terms of having so few non-negative ads. And whether this was the right decision or not, it probably had more impact than whether she visited Wisconsin, for instance.

harry: One of the questions that I haven’t seen answered is whether running against Trump could work merely because Democrats are fired up. Or whether they will need to win over Trump voters. Right now, the generic ballot suggests that Democrats won’t have that hard of a time convincing people to vote against Trump.

perry: People wanted to vote for Trump. Or enough of them, in the right areas. I think 2018/2020 are referendums on him. A 10-point plan on X is fine. But it will be ignored.

Who among us has read Chris Murphy’s foreign policy vision?

Or Elizabeth Warren’s new book?

micah: Who hasn’t!?

Pop quiz: What’s the title of Warren’s book?

natesilver: I’m not sure I’ve ever read a book written by a politician. Or at least not a “my vision” sort of book.

perry: “This Fight Is Our Fight.” I read it last week. Raise?

micah: At FiveThirtyEight, you actually get your pay docked for reading that kind of book.

perry: Murphy says we should double the foreign aid and diplomacy budget.

micah: That’s a winning message for sure.

natesilver: This Fight Is Your Fight. This Fight Is Our Fight. From California. To The New York Islands.

harry: One under-studied group is people who voted for neither Clinton nor Trump and voted for a Democrat or Republican for the House in 2016. Third-party votes made up about 3 percentage points more of the presidential than the House vote. If Democrats can win a good chunk of those in 2018, it could help them out on the margins.

perry: Right. It’s not clear Democrats need to win many Trump voters next year.

micah: OK, question No. 2: Do Democrats need a message or plan that appeals to white working-class voters?

clare.malone: They need a message that appeals to all working-class voters. We touched on this a little bit last chat (I think — they’re starting to blur), but Democrats need a front-and-center message that is hard-core populist economics (or at least rhetorically), appeals to white, black and Latino voters, and puts identity politics on the back burner a little.

That’s the real talk. It’s not that Democrats need to get rid of talking about identity politics — which is what people always read — but it’s an emphasis thing.

natesilver: There’s the issue that white working-class voters are overrepresented in swing states. And also in the House and (especially) the Senate, given that they have something of a rural bias.

perry: I think the empirical answer to this is “not really,” right? You can win through gains in the suburbs, among college-educated whites, etc. And according to a new study by the Public Religion Research Institute, the data suggests that white working-class voters are being moved to Republicans by Trump-style rhetoric such as “Make America Great Again” and a kind of cultural nostalgia. Democrats can’t out-identity the Republicans on issues like limiting immigration.

micah: Trump’s appeal to white voters along cultural resentment lines — particularly on issues like immigration — was huge, right? I mean, that was Clare’s thesis in “The End Of A Republican Party.”

perry: The PPRI study suggests that it’s not that Democrats talked about Black Lives Matter too much, but that Trump talked about the problems of illegal immigration just enough.

This is where the Bernie Sanders approach falls apart, to me.

If the issue is not Democrats talking about race too much, but that Republicans have found cultural issues that work or them, that’s a more complicated issue. How do Democrats appeal to white-working class people worried about cultural issues/the growing diversity of the country, etc?

That is what PPRI was highlighting.

harry: I haven’t read the report as in depth as you have, Perry, but I tend to think that over the long run, these things balance each other out. That is, it may not be tomorrow that Democrats win over enough college-educated whites in the Sunbelt to offset losses among working-class white voters in the Northeast and Midwest. But eventually, these things tend to work out to a 50-50 nation. (For what it’s worth, the PPRI study is not the first to mention the idea that Democrats would lose ground among whites fearful of the growing diversity of the country. It’s been long discussed in academia. It’s just that 2016 was the first time we really saw it in action on a national scale.)

perry: My point, to say this bluntly, is that if winning white working-class voters is about culture, not economics, I’m not sure what a Democratic message for them sounds like.

micah: Yeah, I can’t imagine a majority of Democrats will start dog-whistling on race.

natesilver: This point is a little hard to articulate, but are we overrating how much choice Democrats have in this area? A party, like any other large group, is sort of made up of its constituent parts.

clare.malone: Nate, by that do you mean … catering to local culture? Catering to the different factions of the party in different geographic regions?

natesilver: I mean, you basically have a party made up of (1) white urbanites; (2) some wealthy white suburbanites, especially women; (3) blacks; (4) Hispanics; (5) Asians.

I guess I’m just asking whether these things are self-fulfilling to a certain extent. People look at the sorts of people who are Democrats and they say, “That’s not me.”

perry: Right.

micah: But Democrats are recruiting 2018 candidates as we speak. Don’t they have some agency there?

harry: Candidates still matter in House elections. You’re probably not going to win in Wyoming if you’re a Democrat, but you have a chance to pick off some interesting seats if you run the right people.

perry: Yes, they have some agency. Candidates do matter. I’m suggesting, if I were recruiting candidates, I would spend less time on populism, more time on finding people with cultural ties to their areas.

To me, if we think Joe Biden would have done better than Clinton, we are talking about culture/identity, not populism. (Although I don’t deny they are related.)

clare.malone: The most interesting lab for all this are state legislative elections.

micah: Why, Clare?

clare.malone: That’s where Democrats can test hypotheses of who might win … or if their fate is sealed in certain places by demographics and a shifting culture.

natesilver: The party can and should be more inclusive. And that means finding the “right” candidate to compete in lots of red-leaning areas. And a “big tent” attitude that permits multiple messages at a time.

clare.malone: So you could take your chance and see whether or not a populist running in a more Trump-leaning area can actually sell something in the Democratic-brand. Or if he’s just perceived as, I dunno, the liberal elite’s tool in such-and-such locality.

micah: OK … next question: Do Democrats need a better media strategy?

(This is Nate’s question, so, Nate, please explain the thinking behind it.)

natesilver: Haha. I guess I meant two things by that.

The first component is that if we’re diagnosing what went wrong for Clinton, her media coverage was an important part of it, particularly the coverage of email related stories (including FBI Director James Comey’s letter).

micah: Here we go …

clare.malone: Please just see Nate’s 30-part series on this.

natesilver: So do Democrats need to push back more against the mainstream media when the mainstream media latches on to dumb narratives? It might feel unnatural for Democrats because the mainstream media — like Democrats — have a center-left orientation. But it was certainly a problem for Clinton.

micah: Clare, Nate’s series is a skimpy 10 parts at the moment.

perry: The greater media push back is already happening: See Bret Stephens. Or look at Neera Tanden’s Twitter feed. Democrats now constantly attack The New York Times.

natesilver: See, I’d argue that the pushback against the NYT, et al., is healthy for Democrats. The mainstream media has a lot of different hang-ups and biases, one of which is a liberal/cosmopolitan bias. But another one is that they respond to people who work the refs, and the right has been much better about working the media referees than the center-left has for a long time.

micah: Hasn’t the media gotten better about not getting bamboozled by criticism into slanting coverage? Remember when climate change was a “both sides” issue? That’s not the case anymore.

clare.malone:

natesilver: The Times just hired Bret Stephens, and MSNBC just hired George Will, so I’m not sure that climate is the best example.

perry: Right.

micah: Lol.

I’m talking news coverage, though.

harry: I’d say Democrats did a pretty good job of getting a network like CNN to call Trump a liar on its chyron. Trump lies more than the average politician, but still. Isn’t that a sign that Democrats can do a pretty job of working the refs too?

clare.malone: Whoa. Stop, guys. The “Democrats” didn’t make CNN do that. Let’s give journalism some credit.

harry: Oh, I disagree tremendously. CNN was giving Trump wall-to-wall coverage with little pushback. For a very long time. I’m not saying CNN’s own journalists didn’t also fight back. But I think Democrats definitely worked the refs.

natesilver: CNN became a lot more sophisticated over the course of the campaign, which is not to say they don’t still have problems.

perry: Jeffrey. Lord.

micah: I mean, there was a learning curve for everyone in covering Trump. Us included.

natesilver: For sure.

clare.malone: Again, I’ll make my now-tired response: TV news was very different than other news in how they were covering Trump.

micah: Yeah, we really shouldn’t lump them together. TV has much different incentives.

micah: OK, so we think Democrats should keep working the refs?

perry: This will not be fun as a reporter, but I think the Democrats should invest as much time bashing the media as the Republicans have.

natesilver: Another media question: Do Democrats need to deal with the social media environment, the alt-right, “fake news,” WikiLeaks and the like?

perry: That’s where I think Democrats will have trouble. There is going to be active resistance on the left to the kind of misleading, false, crazy media style of some of the right-wing sites. Fake news, or what have you, can be an effective political strategy. And is dangerous for democracy.

clare.malone: The Democratic Party is a bigger tent. Breitbart works because of the out-group mentality of many Republicans and their relative demographic homogeneity.

harry: I’m not sure there would be that much resistance, at least based on my Twitter feed.

micah: With Trump in the White House, there definitely has seemed to be an uptick in liberal conspiracy theories. But I think Clare’s right that there’s something about the left culturally that keeps that wing of the party more contained?

perry: Right.

clare.malone: Although, they’re certainly more activated these days.

micah: So to Nate’s question about whether Democrats need a strategy to combat that stuff … do they? What would it be?

natesilver: Yes, they need a strategy. And, no, I don’t have any idea what the strategy should be.

harry: No clue. I mean I just go back to evidence-based reporting. Checking multiple mainstream media outlets as well.

clare.malone: If we’re going to revert to Nate’s idea that Democrats need only to run against Trump in the midterms, then they use Trump’s previous statements to the media, positions covered by Breitbart, et al., during the campaign, and use it against him. He didn’t #draintheswamp, for instance.

To me, that promise that he made during the campaign:

And then the reality of all the bankers that work in the White House right now, could be fairly powerful if deployed correctly.

natesilver: That could make sense, sure. There’s also the inherent tension that Brietbart defines itself in opposition to the establishment, and Trump is sort of the establishment now.

micah: David Brock and James Carville are arguing that Democrats can undermine Trump’s populist credibility on health care, too.

micah: OK, to close us out: If you were advising Democrats to take one thing away from the 2016 election, what would it be?

harry: There are no guarantees in politics.

clare.malone: There is a new order in your party: Recognize it.

natesilver: Mine would be: Don’t assume that demographics equal a favorable destiny for Democrats.

micah: Harry, yours is a total cop out.

Nate’s too, kind of.

perry: I’m just struck by all of the cultural anxiety research coming out. Economics are a factor too, of course, and these things are related. I think Democrats should SAY they are reaching out to working-class whites for sure. All the time. Every party should say they are reaching out to all voters. And they should try to reach them. But (i) I’m not sure how successfully they can really reach white-working class voters, (ii) they have to assume that means reaching working-class whites on cultural and economic grounds, and (iii) that is not simple.

harry: If Democrats reach out to black voters more and well-educated white voters, that could work as well. Alas, I guess that wouldn’t allow a lot of reporters to head to run-down towns in the Midwest, though.

natesilver: My lesson is: “It all comes down to turnout.”

May 10, 2017

How To Know if The Trump-Russia Story Has Momentum

When the media talks about President Trump and Russia, it often does so in terms of dominoes falling or pressure building incrementally on the administration. With an investigative story here, a firing or a resignation under suspicious circumstances there, it’s easy for people to assume that eventually something will give, the way Richard Nixon finally broke and resigned after the Watergate story gradually developed from 1972 through 1974.