Nate Silver's Blog, page 107

April 3, 2017

The Gorsuch Filibuster Shows Liberals’ Clout

At least 41 Democratic senators have publicly committed to filibuster President Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch, leading to a probable showdown with Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

The filibuster might seem like payback for Democrats after Republicans refused to consider the nomination of then-President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, for 293 days starting last year. Unlike Republicans last year, however, Democrats don’t have all that much power. They aren’t in the majority — and McConnell has strongly hinted that he could seek to eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court picks if Gorsuch can’t get 60 votes. Across a variety of surveys, moreover, a plurality of voters think the Senate should confirm Gorsuch, although a fair number of voters don’t have an opinion either way. Therefore, Democrats’ political endgame is unclear.

Gorsuch is quite unpopular with liberal voters, however: By a 61-15 margin, they oppose his confirmation, according to a YouGov poll last week. Thus, the planned filibuster may simply be a sign of the liberal base’s increasing influence over the Democratic coalition. The share of Democrats who identify as liberal has steadily increased over the past 10 years. According to the recently released Cooperative Congressional Election Study, 53 percent of Democratic voters identified as liberal last year. Until recently, it was rare to find surveys that showed liberals made up a majority of the party.

But to some extent, that 53 percent figure understates the case. The CCES also asked voters about whether they’d engaged in a variety of political activities, including donating to a candidate, attending a political meeting, working on behalf of a campaign or putting up a political sign. Among Democrats who’d done at least one of those things — a group I’ll call “politically active Democrats” — 69 percent identified as liberal. These were some of the voters who helped propel Bernie Sanders to almost two dozen primary and caucus victories last year.

Oftentimes these liberals are found in states where you might not necessarily expect them — such as in the Mountain West, which was a strong region for Sanders last year. According to a regression analysis conducted on the CCES data, the proportion of politically active Democrats who identify as liberal is larger in states where candidate Trump fared poorly. But controlling for that, it’s also larger in states that have more white voters, and more college-educated voters. And it’s larger in the West than in the other political regions of the country. In the table below, I’ve estimated the share of politically active Democrats in each state who identify as liberal. Since the sample sizes for some states are small, the estimates are based on a blend of the raw polling data from the CCES and the regression model I described above.

SHARE OF POLITICALLY ACTIVE DEMOCRATS THAT IDENTIFY AS LIBERAL

STATE

DEM SENATORS UP FOR RE-ELECTION

POLL-BASED ESTIMATE

MODEL-BASED ESTIMATE

BLENDED ESTIMATE

D.C.

87%

77%

84%

Idaho

92

74

82

Utah

85

74

80

Washington

Cantwell

78

76

78

Minnesota

Klobuchar

78

74

78

Oregon

77

78

77

New Hampshire

81

71

76

Vermont

Sanders

78

75

76

Montana

Tester

73

77

76

Alaska

84

71

75

New Mexico

Heinrich

76

73

75

Maine

King

78

69

74

Arizona

75

70

74

Massachusetts

Warren

75

72

74

Connecticut

Murphy

75

72

74

Rhode Island

Whitehouse

74

73

73

Virginia

Kaine

73

68

72

California

Feinstein

72

74

72

Michigan

Stabenow

73

69

72

Indiana

Donnelly

73

68

72

Wyoming

83

67

72

New York

Gillibrand

72

71

72

Iowa

72

71

71

Illinois

71

70

71

South Dakota

82

67

71

Colorado

69

75

70

Nebraska

73

67

70

Arkansas

78

59

70

Florida

Nelson

69

66

69

Nevada

68

69

69

Tennessee

70

63

68

Pennsylvania

Casey

68

70

68

Delaware

Carper

63

72

68

Wisconsin

Baldwin

67

72

68

Ohio

Brown

68

68

68

Kansas

64

70

66

Mississippi

73

54

65

North Carolina

64

66

65

Texas

64

63

64

New Jersey

Menendez

63

67

63

Oklahoma

63

61

63

Louisiana

61

66

63

North Dakota

Heitkamp

51

66

61

Kentucky

60

64

61

Hawaii

Hirono

43

71

61

Missouri

McCaskill

60

65

61

Alabama

61

57

59

Maryland

Cardin

58

64

59

West Virginia

Manchin

49

67

57

South Carolina

51

59

54

Georgia

49

61

51

Where is the Democratic base most liberal?

Source: Cooperative Congressional Election Study

It’s not surprising that Washington, Oregon and Vermont are places where the liberal wing of the Democratic base dominates. But Idaho, where I estimate that 82 percent of politically active Democrats identify as liberal, and Utah, where I estimate that 80 percent do, also rate near the top. It’s not that Idaho and Utah are blue states, obviously; they’re among the most Republican in the country. Nonetheless — perhaps because a lot of moderate voters identify with the GOP in these states — the few Democrats that remain are overwhelmingly liberal.

The same phenomenon holds in Montana, where I estimate that 76 percent of politically active Democrats are liberal. That may help to explain why Sen. Jon Tester of Montana says he will vote against Gorsuch, even though he faces a tough general election campaign next year. Whether or not Democrats would issue a primary challenge to Tester, who has generally sided with the party on key votes, is questionable. Nonetheless, he’ll be relying on his base for money, volunteers and a high turnout on Election Day. In Montana, the conservatives are conservative — but the Democratic base is fairly liberal also.

By contrast, Democratic Sens. Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, who will vote to confirm Gorsuch, are on somewhat safer ground. Some 61 percent of politically active Democrats identify as liberal in North Dakota, while 57 percent do in West Virginia, according to this estimate. Those figures are almost certainly higher than they would have been a few years ago. But Heitkamp and Manchin probably face more risk from the general election than from a loss of support among their base.

Nor is the Democratic base all that liberal in the Mid-Atlantic region, including states such as Maryland, Delaware and New Jersey. Instead, even the party activists in these states can have a moderate, pro-establishment tilt. That may explain why senators such as Chris Coons of Delaware and Robert Menendez of New Jersey were slow to announce their positions on Gorsuch before eventually deciding to oppose him.

Politics Podcast: The Political Calculus Of A Filibuster

Subscribe: iTunes |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

New to podcasts?

Senate Democrats secured enough votes Monday to sustain a filibuster of Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team discusses the political calculus at play for Democrats and what a rule change by Republicans to end filibusters for Supreme Court nominations would look like. They crew also plays a new game, “Smoke or Fire?” to determine which recent scandals are the most significant. Then they debate a recent piece from The Upshot, suggesting that, “Turnout Wasn’t the Driver of Clinton’s Defeat.”

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast will be taping a live show at the Comedy Cellar in New York City on April 18 at 7pm.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 28, 2017

What Should Trump Do Next?

In this week’s politics chat, we debate what the Trump administration should focus on next, now that its health care reform push has fallen apart.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Our topic for today:

More specifically: With the Republican health care bill in shambles, what should Trump do now?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Eat a lot of ice cream.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Is Trump :toast:?

micah: No. That’s not our topic.

clare.malone: He is toasty looking.

natesilver: He is at a new low in our approval ratings tracker, 41.8 percent.

micah: Should Trump:

Go to war with the Freedom Caucus?

And/or try to form a governing coalition with moderate Democrats?

And/or ditch Paul Ryan?

What are the other options?

natesilver: What Would the West Wing Do? (WWWWD?)

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Those are not great options.

micah: We need more options.

perry: I think getting Neil Gorsuch confirmed to the Supreme Court is step No. 1.

Show you can do something.

micah: Focus on Gorsuch.

clare.malone: You don’t want to go to war with the Freedom Caucus, do you?

I mean, I would think you’d try to loop around them. Court moderates?

perry: And House Speaker Paul Ryan has the same problems former Speaker John Boehner did. Replacing Ryan is not a solution.

natesilver: Trump should put forward a big infrastructure bill — which could potentially be quite popular — and dare Congress to oppose him.

perry: Reince Priebus, Trump’s chief of staff, hinted on a Sunday show that they would court moderate Democrats.

clare.malone: Yeah, infrastructure seems like a surer bet than taxes, right?

perry: Right

clare.malone: EVERYONE LOVES BUILDING THINGS.

perry: Tax reform is hard and complicated and will have GOP opponents.

natesilver: I think John Harwood has a pretty good summary here: https://twitter.com/JohnJHarwood/status/846410720883421189

perry: Unless “tax reform” is just tax cuts for everyone, which would be fine.

natesilver: It feels like Trump needs a win in there. Gorsuch will probably provide one, at least in terms of keeping his base happy.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Let’s back up the train on Gorsuch. Let’s back it up. Chris Coons is saying that Republicans might not get the 60 votes necessary for cloture, which could cause the nuclear option to be invoked. (Getting rid of the filibuster on Supreme Court nominations.) Then you add on everything else. It’s not pretty.

micah: But even if that’s a fight, it’s a good fight for Trump, right?

natesilver: Gorsuch is somewhat popular with the public though, no? And Democrats haven’t had good messaging in why the Congress should reject him. Isn’t Trump sort of on the right side of the argument?

perry: Right now, yes. My only question is if public opinion is movable on Gorsuch, particularly if Trump/Stephen Bannon/Stephen Miller say something publicly that is problematic for the confirmation (“He will uphold our travel ban,” etc.)

harry: Gorsuch is somewhat popular, though not overwhelmingly so. My research indicates that the popularity of a SCOTUS nominee can be somewhat fluid. These types of things can cascade. It may not. But I think there’s a sense of blood in the water.

micah: But in terms of what comes next: Does Trump focus on Gorsuch to the exclusion of everything else? Doesn’t the White House need to decide pretty soon whether to do tax reform/infrastructure?

perry: Good question. They seem to saying tax reform is the next big project. I think it’s government funding first, then debt ceiling.

natesilver: In a purely tactical sense, there are worse fights Trump could have. Which is one disadvantage to Democrats filibustering Gorsuch. But I don’t think the Democrat base is going to let them get away with not taking a pretty tough line on Gorsuch.

perry: So what should Trump do? We seem to think Gorsuch, then infrastructure. But my impression is he is doing tax reform. I get the sense he is passionate about that issue

natesilver: As you said, an across-the-board tax cut — à la George W. Bush in 2001 — could be reasonably popular. Something mostly geared toward high earners might not be.

micah: Yeah, I’m not sure why we think infrastructure would be that easy? Like, he’s vulnerable… are Democrats really going to bail him out and give him a win?

clare.malone: It’s certainly more in Trump’s traditional wheelhouse (tax reform).

natesilver: I’m not saying it would be easy to actually get something done on infrastructure, but Trump would be on the right side of public opinion, most likely.

harry: I like the tax cut idea if it’s broad and across the board. But is that something the House GOP would actually do?

clare.malone: I mean, some of our theorizing is a little moot … he seems to be pretty clear he wants tax reform. Don’t we think he’ll hold big sway with the agenda?

perry: No. A government funding fight and a debt ceiling one could take weeks to resolve — and again make Mark Meadows the star of D.C.

harry: We know, for example, that people think the rich don’t pay enough in taxes, and that they, themselves, pay too much. Of course, Americans felt that way too in 2001 too. One of the big lessons of the health care fight is that something cannot be seen as being geared toward the rich — or shifting the burden away from them. Yet, that’s also something that some Republicans (see Ryan, Paul) have an inclination to do.

natesilver: The Trump tax plan — or at least the one he was pitching on the campaign trail — involved massive tax cuts for high-income earners and smaller tax cuts (and perhaps even tax increases for some groups depending on how the bill was designed) for the middle class. So I’m not sure how that would poll. It would depend a lot on the marketing of it, and that’s not been a strength of Trump and the GOP so far.

perry: I wonder if Trump should go outside the Congress/big bill category. Bill Clinton did this on school uniforms. Barack Obama cheering on the gay rights movement and later Black Lives Matter.

micah: That’s interesting.

clare.malone: Immigration something.

micah: Yeah, maybe he does an outside-the-beltway push related to immigration in some way? Or ISIS.

natesilver: He’s also on the wrong side of public opinion on immigration in lot of ways, though.

clare.malone: This just in across the transom:

FWIW: Federal judge in San Francisco to hear preliminary injunction motion against Trump sanctuary cities EO next Weds, April 5

— Josh Gerstein (@joshgerstein) March 27, 2017

harry: Look at Trump’s approval ratings on immigration. Lots of low 40s and 30s. Perhaps certain elements of his plan are more popular, but I tend to think that the approval rating for the overall policy matters more.

perry: Policing, tax cuts, paid family leave. These are issues where he may find less resistance. And he mentioned them all in his big speech to Congress in February.

Immigration has hard lines. Trade?

harry: His higher approval ratings generally revolve around the economy and maybe terrorism. Keep in mind, his executive orders on restricting travel from several majority-Muslim countries didn’t poll that badly.

natesilver: Cracking down on sanctuary cities is an exception in that it’s an issue where the public seems to be with Trump. That’s a better fight for him than the border wall, for instance.

perry: Interesting. Do we think this Environmental Protection Agency policy is in the right direction? Is that pro-economy or anti-environment to voters?

micah: Yeah, I think — if done smartly — he could make a public push on some of these immigration and environmental policies framed around jobs. From the coasts, it’s easy to underestimate how well that stuff plays.

clare.malone: “The Waters of the U.S.” rule is the magic phrase in all that. It’s an EPA rule that Republicans loved to bash during the primaries with the notion that it was the kind of regulation killing industry.

natesilver: Opinion is also against him on removing environmental regulations.

micah: Polls shmolls.

harry: Plus, the environment is not an important issue in the eyes of voters.

perry: This raises the question: What on the Trump/GOP agenda is actually popular with the public? Nate keeps highlighting things that are not popular

micah: Not letting refugees in.

natesilver: His agenda isn’t that popular, which can happen when you only get elected with 46 percent of the vote, including a lot of people who come along grudgingly because they hated your opponent even more.

Remember, George W. Bush — who was elected under similar circumstances in 2000 — made a point of having a much more bipartisan agenda, although that changed a lot after Sept. 11.

Trump never really made noise about reaching out to the other side of the aisle. And Republicans chose a very partisan piece of legislation for their first major policy initiative, health care. Infrastructure bills and some tax cut proposals would be popular. Immigration and national security stuff seems to be on a case-by-case basis, with voters generally having more trust for Trump on the latter than the former.

harry: What Nate said … I think there’s a reason Trump has an approval rating in the low 40s according to our tracker. And sometimes people misread winning an election with winning a mandate. Those two things don’t always go together. Trump has behaved as if he won 55 percent of the vote. I also think we may underestimate how much his personality grinds on Democrats, which may make it more difficult for them to cross the aisle even on issues on which they agree with him.

micah: OK, let me flip this conversation a bit, from issues to coalitions…

Trump has the House and the Senate. He has Republicans and Democrats. He has the conservative, anti-establishment Freedom Caucus and the more moderate Tuesday Group. He has Sens. Rand Paul and Mitch McConnell and Ted Cruz.

Who should Trump be aligning himself with? Despite unified GOP control, Trump has yet to put together a real governing coalition — how does he scrap one together?

clare.malone: I mean, I would say the Tuesday Group.

natesilver: As a bit of math, if you don’t get any Freedom Caucus votes in the House, you need in the neighborhood of seven or eight Democrats, depending on how many people are absent from Congress at any given time.

clare.malone: That doesn’t seem craaazy. Even for 2017.

natesilver: But it also assumes you’re batting 1.000 with Republicans not in the Freedom Caucus, which is pretty unlikely.

perry: Clare, from your reporting, are there seven or eight Democrats in the House who would work with Trump?

clare.malone: There are a few Democrats who caucus to the right, I would say. And on something like say, infrastructure, you might be able pull people in. I think it depends … tax reform seems trickier to me (for many reasons).

harry: Tough for me to see too many Democrats going along with Trump when his approval rating with Democrats, according to Gallup, is 8 percent.

natesilver: There are 12 Democratic representatives from districts that Trump won, which is not that many, but it’s something. And maybe around five others that have oddly high Trump scores despite being in districts Hillary Clinton won. So there’s a little something to work with.

But as Harry says, Trump is really unpopular with Democrats, so he’s going to have offer actual concessions and not token-ish ones.

perry: My answer: Govern with McConnell. Figure out which bills will pass in the Senate. The American Health Care Act was going to die there anyway. And McConnell is, I would argue, smarter than Ryan on tactics.

harry: I like Perry’s answer.

micah: Don’t you still have to figure out the House?

natesilver: Could any bill that could pass the Senate also pass the House?

perry: Lol. That seems like a broader issue.

harry: Well, at least you’d know what coalition you’d need in the House.

natesilver: The weird thing about the Senate is that on a proportional basis, there are a lot more moderate Democrats.

clare.malone: Yeah.

micah: I guess that’s my point, though… I don’t think this is on Ryan. There’s a group in the House that says no to everything. If you don’t completely cater to the Freedom Caucus, you’re kind of screwed?

clare.malone: It seems like the House is the real knot to untangle for Trump.

micah: Agree ^^^

natesilver: You have the Red State Five in the Senate (Joe Manchin, Joe Donnelly, Heidi Heitkamp, Claire McCaskill, Jon Tester) who are gettable-ish on some issues.

perry: A small dissent. We saw a Freedom Caucus member leave the group on Monday.

micah: Yeah, that was interesting.

perry: If the Freedom Caucus was the only votes against a bill, and it failed only because of them, that would be interesting.

I wonder if that would change the membership of the Freedom Caucus.

clare.malone: It wasn’t though, right? In all likelihood?

perry: I think Bannon had that one point basically right: There was some value in having a vote on Friday.

natesilver: Trump (and Bannon) handled the last 24 hours of the health care imbroglio fine and were smart to hold a vote instead of letting things drag out.

micah: There was no vote.

harry: There was in Nate’s mind.

He’s next level thinker.

micah: Three-dimensional chess.

natesilver: Smart to **schedule** a vote.

Two-dimensional chess.

micah: 12-dimensional.

natesilver: 1-dimensional.

Checkmate.

perry: If I were the GOP leadership, I would try to smoke out the Freedom Caucus a bit, see if they will vote down a bill the rest of the House GOP wants to pass. See if the Freedom Caucus is really 30 people or the core is really 15-20.

micah: Yeah, and that makes a big difference.

natesilver: I’m not sure health care was a great test case for that, though, since the bill could also easily have died from moderate opposition.

perry: Exactly.

harry: But I think the Freedom Caucus did something rather interesting, according to reports. They basically formed a union. A union not to get picked off. The question is what type of bill would the Freedom Caucus not like that everyone else would like.

perry: I suspect this upcoming government funding bill. But we will see.

natesilver: There’s also the idea, as brought up by Andrew Sullivan, that Trump will find some hawkish response to a terrorist attack or foreign entanglement as a distraction from his domestic woes. Which seems … not unlikely to me.

clare.malone: George W. Bush 2.0.

harry: Yemen War?

clare.malone: Only if the conflict is seriously affecting Saudi borders.I don’t see that happening. I.e., Yemen’s not important enough from the U.S.’s point of view to really waste a full on war with (it’s no resource-rich Iraq).

harry: They are weighing it.

natesilver: I sort of think Trump’s canny enough not to get the U.S. involved in another Middle Eastern war without a clear provocation.

micah: Wow. What the hell makes you say that?

natesilver: I’m thinking more about like what if the London attack last week had happened in front of the U.S. Capitol.

perry: I know we are nearing the end, but Clare wrote that interesting piece on Democrats’ effort to organize a resistance movement. I’m curious if we can have a brief “are the Democrats doing really well or is Trump’s team just making mistakes” discussion?

micah: Yeah, let’s wrap with that ^^^ question. Clare, you wrote that piece, so you go first.

clare.malone: My answer is: We don’t have enough information yet. There have been no elections to test whether or not the Democrats have their act together yet. That’s a lot of what my piece was talking about — how do the Democrats come back from the brink, electorally.

I think, though, that the Democrats’ potential filibuster of Gorsuch is an outcrop of that grassroots movement, perhaps.

micah: Yeah, I tend to agree. Although, the nature of the stumbles so far — travel ban, health care, wire-tapping, Russia — don’t seem very dependent on Democratic actions. So I think I lean towards the Trump team making mistakes. And whether Democrats have done a decent job capitalizing on those mistakes we’ll need an election to test.

natesilver: FWIW, I think there’s a pretty clear order of those stumbles, which is (1) health care (2) Russia (3) travel ban (4) wire-tapping. But you’re right that they’re mostly unforced errors.

micah: Alphabetical?

natesilver: Although, you can argue that Democrats won the long-term messaging war on insurance-for-everyone and that made it much tougher for the GOP to pass a health insurance bill. But, of course, Democrats paid a high price for their Obamacare votes in 2010.

harry: On the travel ban: There were Democrats out at the airports protesting. On health care: The Democrats did a good job selling what a crummy bill it was, and zero Democrats defected and voted for the bill. On wiretapping, Rep. Adam Schiff, the ranking minority member on the House Intelligence Committee, has done a good job of making Rep. Devin Nunes, the chairman, look silly. So yes, the Trump administration has set itself up. But also, Democrats have not screwed up those opportunities. Not yet, anyway.

perry: I basically agree with what Harry said.

micah: OK, final thoughts?

natesilver: There are still a wide variety of outcomes for how Trump’s presidency could unfold. But the successful ones increasingly require him to change course.

perry: Health care is really hard. Really hard. And the Russia controversy kind of saps the presidency in some unmeasurable ways. But if he gets Gorsuch confirmed, things won’t look as bad.

March 27, 2017

Politics Podcast: Live From Boise

Subscribe: iTunes |

ESPN App |

Download |

RSS |

New to podcasts?

This week’s FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast was recorded live at the Treefort Music Fest in Boise, Idaho. The team talked to Boise Mayor David Bieter about local partisanship, played a round of wonky political trivia and answered audience questions. The crew discusses the failure of the House GOP health care bill in a separate live emergency podcast.

Checking out the @FiveThirtyEight political podcast at @treefortfest pic.twitter.com/oefnbnaUED

— Matt Gregg (@MattGregg70) March 24, 2017

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Trump Doesn’t Have A Mandate For Paul Ryan’s Agenda

There were so many reasons for the failure of the Republicans’ health care bill — and its failure was so spectacular — that it’s hard to tell which ones mattered most. The bill was poorly drafted and lacked buy-in from key Republican stakeholders. President Trump’s boardroom negotiating tactics didn’t translate well to the halls of Congress. The House Freedom Caucus was intransigent; it represents a new axis of conflict within the GOP, and House Speaker Paul Ryan didn’t have a good plan for handling it.

Any of these factors alone might have scuttled the bill; health care legislation is never easy. Taken together, they not only doomed the bill but imploded it. Republicans had promised to repeal the Affordable Care Act for seven years; their bill didn’t survive for three weeks.

But the variety of unforced errors by Ryan, Trump and other Republicans obscures other, more fundamental problems with their health care bill. Namely, the American Health Care Act was a fairly radical piece of legislation and — perhaps relatedly — an exceptionally unpopular one. The public may have wanted change when they elected Trump, but this was not the sort of change they were looking for.

The AHCA wasn’t radical in the way a Freedom Caucus-designed bill might have been. It didn’t dismantle Obamacare’s exchanges. It wouldn’t have allowed insurers to deny coverage on the basis of pre-existing conditions. Philosophically, it didn’t do much to challenge former President Barack Obama’s notion that Americans had a right to health insurance and that government had a duty to ensure its availability. For these reasons, Freedom Caucus members and libertarian-ish Republicans complained that the bill didn’t go far enough.

But the bill had huge redistributive effects. The AHCA would have cut taxes by almost $600 billion over a decade, but almost all of the reductions would have been realized by people making at least $200,000 a year and much of it by people making $1 million a year or more, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation. By contrast, insurance premiums would skyrocket for older, poorer Americans. On average, a 64-year-old with an annual income of $26,500 per year would have to pay about $14,600 to purchase insurance on the exchanges, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Obamacare, of course,

March 25, 2017

Emergency Health Care Podcast: Live From Boise

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast happened to have a previously scheduled live show in Boise, Idaho, (as part of the Hackfort festival) on Friday, the same day that the House GOP’s Obamacare replacement bill was pulled. The team joined a crowd at the Egyptian Theatre to discuss the political implications, what the development means for President Trump’s other priorities, and why the bill was so widely panned.

We’re putting up the conversation about health care now. The rest of the live show will appear in Monday’s regular slot.

Checking out the @FiveThirtyEight political podcast at @treefortfest pic.twitter.com/oefnbnaUED

— Matt Gregg (@MattGregg70) March 24, 2017

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 23, 2017

Trump Has No Good Options On Health Care

UPDATE (March 23, 8:43 p.m.): Late on Thursday, Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told reporters that Trump is demanding the House vote on the GOP health care bill on Friday. Mulvaney also said that if the bill doesn’t pass, Trump will move on to other issues. We’re not sure if this is a call, fold or a raise — it’s sort of a combination of all three. But it underscores that Trump is in a tough position.

Sometimes in a poker hand, you find yourself with no good choices. You’ve invested a lot of money in the pot. But then your opponent unexpectedly makes a large bet and you have a marginal hand. Your options — folding, calling and reraising (as a bluff) — are all money-losing plays. But you have to pick one of them, and it’s a matter of finding the least-worst outcome. It’s the situation every poker player hates the most.

President Trump finds himself in a similar predicament on health care, now that GOP leaders have announced they’re delaying a vote on the House GOP’s bill to repeal and replace Obamacare and seemingly have no clear plan to secure the votes for passage. Trump has a series of bad options for how to proceed:

Trump could fold. This would involve making some public declaration that the Republicans needed to go back to the drawing board on health care or move on to other priorities. While this might allow Trump to save some face, it would nevertheless be a costly play. He’d concede defeat on one of his signature priorities, his reputation as a dealmaker would take a hit, and The House Freedom Caucus would feel as though they had a notch in their belt. It would be embarrassing — and if the past is any guide, Trump wouldn’t handle his embarrassment very well.Trump could raise, going “all-in” on the bill and doing everything he could to secure passage. This would probably involve making further compromises with the House Freedom Caucus — pushing the bill further to the right and perhaps making it even less popular — and then threatening moderate Republican who dared to defect from the bill. It just might work to get the bill across the finish line in the House. Then again, it might not, and Trump would have wasted more political capital without getting anywhere. Or the bill could pass the House and then die in the Senate, putting House Republicans in a position where they’d taken a roll call vote on an extremely unpopular bill and had nothing to show for it. Or perhaps the bill eventually would pass the Senate and become law, only for Republicans to discover that the public wasn’t bluffing when they told pollsters that they hated the bill, hurting Trump’s approval rating and costing Republicans dozens of seats at the midterms. Republicans might face another round of political backlash, furthermore, once millions of Americans discovered they were no longer able to afford their health insurance or their policies didn’t cover as much as they used to.Finally, Trump could call — which would mean distancing himself from the bill without a clear plan for what came next. He wouldn’t officially declare the Republicans’ health care efforts dead; in fact, he and Press Secretary Sean Spicer would stubbornly resist the “FAKE NEWS” narrative that the bill had failed. But he’d largely stop lobbying Republicans on behalf of the bill, instead telling House Speaker Paul Ryan to figure things out for himself. The risks here are obvious enough. Trump — who remains popular with rank-and-file GOP voters and members of Congress — is the best salesmen Republicans have. Without his working on its behalf, the GOP bill would probably become even more unpopular. But Ryan might not have an exit strategy and relations between the White House and Capitol Hill could fray. The whole process could play out for months, exerting a continuous drag on Trump’s popularity, as the Democrats’ health care bill did to President Obama.What play should Trump make? If he took my advice (he doesn’t), he’d probably fold, declaring that the GOP’s bill hadn’t kept the promises he made to voters. He’d ask Congress to start over on the health care bill, moving along to tax reform in the meantime. Perhaps he’d pass some incremental health care bill later on, just as Bill Clinton eventually passed SCHIP (although not until four years later) as a consolation prize for his own failed health care program in 1993. As I said, however, folding would hardly be a risk-free alternative and conceding a loss would be out of character for Trump.

Here’s the thing, though, about a poker player — or a president — who finds themselves in this situation. It’s usually their own damned fault. In poker, being in a no-win situation is often the result of playing a hand you should have folded to begin with or otherwise having misplayed it earlier on.

Trump, and Republicans, have likewise made a lot of mistakes on health care. They didn’t lock down key constituencies before they rolled the bill out, leading to it being attacked from every angle — from the right wing of the GOP, from moderates and from conservative policy experts — upon its debut earlier this month. Instead of taking a populist approach, they adopted a bill with many provisions that were likely to be unpopular and no clear strategy for selling it to the public. They ignored the lessons that Obama and Clinton had learned from their struggles to pass a health care bill. They’ve tried to rush the bill through at a time when the White House faces a lot of competing priorities and distractions. They adopted a bill that predictably got a miserable score from the Congressional Budget Office. And for years, they’ve made all sorts of promises to voters on health care that they knew they couldn’t keep.

Health care policy isn’t easy even under the best conditions. But Trump has misplayed his hand from the start.

March 22, 2017

The GOP Health Care Bill Is Unpopular Even In Republican Districts

With a vote tentatively scheduled for Thursday, the health care bill put forth by Republican Congressional leaders and endorsed by President Trump is still taking heat from all sides in the House of Representatives. Some of the opposition comes from moderate Republicans such as Florida’s Ileana Ros-Lehtinen who represent districts that voted for Hillary Clinton. But most of it has come from the Freedom Caucus and other highly conservative members who say the bill does not go far enough in repealing the Affordable Care Act and scaling back government involvement in health insurance markets.

This puts Trump and Republican leaders in a potentially unwinnable position: Further efforts to mollify conservatives in the House could jeopardize the bill’s already endangered chances of ever passing the Senate. Here’s the thing, though: Trump and Republicans would have a lot more leverage if their bill weren’t so darned unpopular.

I estimate that there are only about 80 congressional districts — out of 435 — where support for the bill exceeds opposition. About two-thirds of Republican members of the House, in fact, likely come from districts where the plurality of voters oppose the bill. And because even Trump supporters have lukewarm opinions on the bill, there may not be any districts where vigorous support for the health care bill exceeds vigorous opposition.

These estimates are derived from a YouGov poll, released on Wednesday, that showed 33 percent of registered voters supporting the GOP’s bill and 48 percent opposed to it. Those numbers are right in line with the polling average for the bill. But YouGov did something interesting and broke down support and opposition based on who respondents said they voted for last November. Among Clinton voters, only 7 percent support the bill while 84 percent oppose it. By comparison, 61 percent of Trump voters support the bill while 16 percent oppose it.

Some of the opposition among Trump supporters probably comes from conservatives; a quarter of conservatives in the YouGov poll said they oppose the bill. In any event, Clinton voters are a lot more uniform in their opposition to the bill than Trump voters are in support of it. And they also have much stronger feelings about it. Among Clinton voters, 71 percent said they strongly oppose the bill, while only 21 percent of Trump supporters strongly support it.

Those numbers are lopsided enough that they come out looking pretty bad for Republicans even in Trump-friendly districts. Take, for instance, Rep. Mike Simpson of Idaho’s 2nd Congressional district, encompassing Boise and the Eastern part of the state, which Trump won 55-30 last November, according to Daily Kos Elections. That’s a really red district. But if you infer these voters’ views of the health care bill based on the YouGov poll and the number of Trump, Clinton and third-party voters in the district, you wind up with only 39 percent in favor in the bill and 43 percent opposed. Meanwhile, strong opposition to the bill exceeds strong support 29-13 in Simpson’s district, according to this estimate. Even in Idaho, therefore, the politics of the bill are dubious for Republicans.

And the numbers are much worse, of course, in districts like Ros-Lehtinen’s. By this calculation, opposition to the bill exceeds support 57-28 in Florida’s 27th Congressional district, where she serves. And strong opposition to the bill exceeds strong support 44-9.

Perhaps there are regional variations in GOP support for the bill, or certain states and districts where support is unusually high, but at least based on this simple estimate, there are about 80 districts, as I mentioned, where supporters of the bill are in the plurality. But I estimate that there are only three of them — Alabama’s 4th, Kentucky’s 5th and Texas’s 13th — where supporters of the bill constitute an outright majority. And even in those three districts, strong opposition to the bill matches strong support for it.

To repeat, Republicans in Congress don’t have a lot of good options on their hands. There are consequences for defying Trump, just as there are consequences for voting for an unpopular bill. But this is not the typical case where Republican members can necessarily count on their base to save them. As polarized as the country has become, the bill has strikingly few supporters, and the average Republican member of the House represents a district where the health care bill is somewhat unpopular.

You can find our estimates of support for the bill in all 435 congressional districts in the table below.

CORRECTION (March 22, 7:22 p.m.): An earlier version of this article misstated how Clinton voters said they feel about the Republican health care bill in a recent poll. Seventy-one percent of those voters oppose it, not support it.

How Much Of The Trump-Russia Story Is Smoke And How Much Is Fire?

In this week’s politics chat, we examine the smoke-to-fire ratio in the reporting about the ties between Trumpworld and Russia. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): I’m making our usual chatmate Harry continue to work on a piece he’s writing for tomorrow, so he’s skipping our chat today. The four of us, however, are checking back in on the Trump-Russia ties story. FBI Director James Comey and NSA Director Mike Rogers gave some interesting testimony on Monday before the House Intelligence Committee. So before we get to our questions, someone give us the main headlines coming out of that hearing — what’s new?

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): We knew that the FBI was investigating Russia-Trump ties. Comey just said it publicly for the first time.

The other headline was how Republicans rallied around Trump and tried to change the subject from Russia ties to the anti-Trump government leaks.

micah: OK, so the fact that the FBI was investigating whether the Trump campaign colluded with Russia to interfere with the 2016 election had been reported, but Comey publicly confirmed it. That was the news.

perry: Oh, and Comey and Rogers slapped down Trump’s claims that Obama wiretapped him or that the British did. Again, we already knew the wiretapping didn’t happen. But Comey said it. And Rogers suggested it was bad for international relations.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): “The department has no information that supports those tweets” is a line that feels very 2017.

perry: Comey was almost deadpan in his remarks.

micah: OK, so the questions …

How much smoke is there in the Trump-Russia story vs.

March 21, 2017

Trump Is Tempting Fate On Health Care

House Republicans introduced their health care bill, the American Health Care Act, only two weeks ago. During that relatively short interval, President Trump’s approval ratings — which were never very good — have become a little worse.

Is that just a coincidence? Could health care be Trump’s undoing when so many things haven’t been? Let’s ask a few more questions about Trump’s popularity and the GOP’s health care plan. The health care bill probably has had a drag on Trump’s numbers, but it isn’t an open-and-shut case.

How popular is Donald Trump? We have a handy interactive to answer that very question. Rounding to the nearest whole number, Trump has a 43 percent approval rating and a 52 percent disapproval rating, according to our polling average.

That isn’t a good score compared to where past presidents stood at this point of their presidencies. George W. Bush had a 55 percent approval rating and a 27 percent disapproval rating at this point in his term, for instance, using the same method that we use to calculate Trump’s ratings, while Barack Obama had a 59 percent approval rating and a 32 percent disapproval rating.

But while Trump’s numbers aren’t good, they aren’t necessarily catastrophic, either. Trump won the election last November even though only 38 percent of voters had a favorable impression of him in the national exit poll. The circumstances behind that victory were quirky — coming partly because Trump had a not-very-popular opponent in Hillary Clinton and partly because of the Electoral College. Nonetheless, neither Trump nor his opponents should take very much for granted.

But what about that Gallup poll? Aren’t Trump’s polls cratering? On Sunday, Gallup published a poll showing Trump’s approval rating falling to just 37 percent, and his disapproval rating rising to 58 percent — the worst numbers they’ve shown for him so far.

These results drew an awful lot of attention from journalists in my Twitter feed. But they’re something of an outlier. Gallup has generally had low ratings for Trump. And their polls have been fairly “bouncy” as compared to those of other polling firms. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it’s important to keep in mind for context. For instance, Trump’s net Gallup approval rating improved by 9 percentage points from Feb. 16 to Feb. 22, even though it was flat in other surveys. And it improved 5 points from Sunday’s edition of Gallup’s poll to Monday’s. Individual polls — and Gallup’s especially — can be noisy.

The bottom line is there’s not much reason to cite individual polls as compared to the polling average.

But Trump’s numbers are getting worse in the average, right? Yeah, they probably are. Other polling firms haven’t shown the massive drop-off that Gallup has. But pollsters from Rasmussen Reports to Ipsos to Fox News have mostly had Trump moving in the wrong direction. Over the past week or two, Trump’s approval ratings have declined by about 2 percentage points in the FiveThirtyEight average, while his disapproval ratings have climbed by about 3 points.

Is the decline because of the health care bill? My view is that the bill probably does have something to do with Trump’s declining ratings. For one thing, the timing lines up fairly well, given that we’d expect a lag of a week or so between when the bill was introduced (on March 6) and when we’d begin to see clear effects from it in the polling average. If you look at a chart of Trump’s ratings, you see a fairly distinct inflection point of the sort that often accompanies news-driven shifts in candidates’ ratings:

And then there’s the fact that the bill has little support from the public …

How popular is the Republican health care bill? It’s not popular at all. Here are the six polls on the bill that we’ve found so far:

POLLSTERSUPPORT/FAVORABLEOPPOSE/UNFAVORABLENET SUPPORTFox News34%54%-20Morning Consult4635+11Public Policy Polling2449-25SurveyMonkey4255-13YouGov/CBS News1241-29YouGov/Huff. Post2445-21Average3047-16The Republicans’ health care bill isn’t popular at allOn average, just 30 percent of voters favor the GOP bill, as compared with 47 percent who oppose it. By comparison, Obamacare had a 40 percent favorable rating and a 49 percent unfavorable rating when it finally passed Congress in March 2010. Later that year, Democrats lost 63 seats in Congress, in part because of the health care bill’s unpopularity. But while Obamacare polled poorly, the numbers for the Republican bill are quite a bit worse.

It’s also the case that a fair amount of the public doesn’t yet have a firm opinion of the GOP bill. In theory, that might represent an opportunity for the GOP to improve the bill’s perception. But the experience of Obamacare suggests the AHCA’s polling may get worse before it gets better. The earliest polls on the Democrats’ health care bill, in the spring and summer of 2009, found the public about evenly divided on it, although with a lot of voters undecided. The vast majority of undecideds turned against the bill, however, as it went through months of congressional infighting. With no clear path forward for Republicans — any bill that could pass the House right now probably won’t pass the Senate without significant alterations — they could be in for the same fate.

A couple of those health care polls seemed weird. What’s up with that Morning Consult poll? Unlike the five surveys that showed the Republican bill to be unpopular, Morning Consult’s poll for Politico last week found a plurality of respondents in favor of it. But there’s an important difference in their poll. As the Huffington Post’s Ariel Edwards-Levy points out, the Morning Consult poll didn’t describe it as a Republican bill, instead referring to “a proposed health care bill in Congress called the American Health Care Act.” That’s probably not informative enough given that the bill’s formal name is fairly obscure to voters.

Without including the Morning Consult poll in the average, approval for the GOP bill drops to just 27 percent with 49 percent disapproving. Still, we’d rather wait for more good polls to come along than to kick the ones we have out of the sample. We’re continuing to monitor the health care polling and should have a more comprehensive review of it for you soon.

I’m still not totally convinced. Why are you so confident that health care is hurting Trump? I’m not totally convinced, either. We can observe when a president rises and falls in the polls, but it’s not always easy to say why. Still, there are lots of reasons to think that health care is a liability for Trump … even in a political climate where people have often been too quick to predict Trump’s demise.

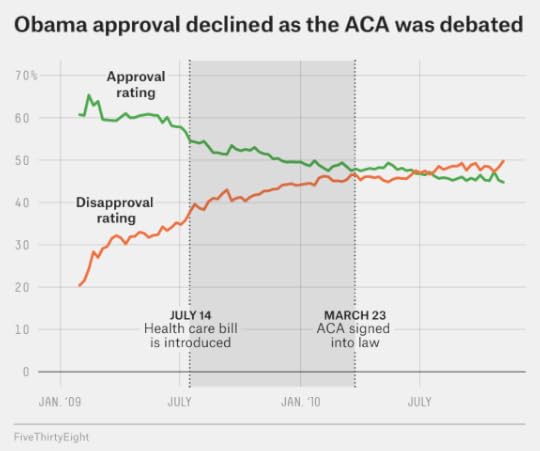

One factor is that we know health care policy can cause big swings in public opinion. In 2009 and 2010, for example, the debate over the Democrats’ health care bill coincided with a sharp decline in Obama’s popularity. From when then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi introduced the House version of the Democrats’ bill in July 2009 to when the Affordable Care Act eventually passed in March 2010, Obama’s approval rating declined by roughly 10 percentage points, while his disapproval rating increased by about 10 points. Perhaps the timing was just a coincidence and Obama’s numbers were bound to decline anyway, but his ratings worsened at a faster rate during the health care debate than before or after it.

There’s also the problem that Trump risks having overpromised and underdelivered. Polling and focus groups suggest that while voters have lots of problems with Trump, they generally trust him to get things done and keep his promises. On health care, Trump has painted himself into a corner. Trump promised to repeal Obamacare, but he also promised a replacement that would provide “insurance for everybody.” However, the number of uninsured people would rise by 24 million people by 2026 under the GOP bill, according to the Congressional Budget Office’s estimates. Furthermore, some of the bill’s greatest impacts — in terms of lost coverage, decreasing subsidies and more expensive premiums — could be felt most acutely by the very older, rural voters who supported Trump in large numbers.

Finally, there’s the matter of intensity, where there’s a massive advantage for Democrats. Some 72 percent of Hillary Clinton voters strongly oppose the GOP’s health care bill, according to the YouGov/Huffington Post poll, while only 13 percent of Trump voters strongly support it. That makes health care a lot different than the typical issue on which partisans are equally riled up on both sides. And it could create problems for Trump and the GOP down the road. Town halls around the country will continue to be rowdy, for instance, while a high Democratic turnout could offset some of Republicans’ traditional demographic advantages at the midterms.

But can we trust these polls in the first place? Oh, this argument again? It’s certainly possible to overestimate the precision of polling. If your fate depended on whether Trump’s approval rating was really 40 percent or 43 percent or 46 percent, for instance, you’d want to take out a life insurance policy. And there are inevitably lots of ways to misinterpret the polling. During last year’s election, a lot of national media outlets mistakenly concluded that the Electoral College would help Clinton. That finding wasn’t supported by the polling, which instead suggested the Electoral College would benefit Trump. But overall, the polls were about as accurate as they’d been historically, with Trump beating his national polls by only 1 to 2 percentage points and his swing state polls by 2 to 3 percentage points, on average.

And when the polls are wrong, it isn’t necessarily in the direction that you’re hoping for, or expecting. In 2010, Democrats predicted that Obamacare would immediately become more popular upon its passage. Its numbers didn’t improve, however, and neither did theirs — instead, Democrats’ position continued to worsen down the stretch run of the midterm campaign, leading to their 63-seat drubbing in the House. Trump and Republicans have every right to cross their fingers and pass a health care bill, as Democrats did. But they can’t necessarily defy their electoral fate.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers