Nate Silver's Blog, page 110

February 15, 2017

What Makes A Trump Story Stick

To work as someone who covers Donald Trump for a living is to sometimes doubt your own memory. Quite often, a story that everyone else treats as a new and stunning revelation seems to you like something you’ve heard before.

To take one example: Last July, there was a modest uproar after Trump gave a speech in North Carolina in which he offered tempered praise for former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. One can understand why this was a story, but Trump had used similar lines about Hussein in speeches, interviews and debates several times before — for instance, in a Republican debate in February. I remember being shocked after that debate that Trump’s comments, which went so against Republican orthodoxy, hadn’t received more attention from voters and the media. I was surprised again in July, when a story that so many people had ignored in February was suddenly treated as salient.

There are a lot of cases like this. Last April, for example, the Boston Globe published a story alleging that Trump had groped a Florida woman named Jill Harth in the early 1990s. The story, despite a lot of carefully reported detail from one of America’s most prominent newspapers, was largely ignored. In October, however, after the publication of a leaked “Access Hollywood” tape on which Trump condoned unwanted sexual contact toward women, and after several more women came forward to accuse him of sexual harassment or sexual assault, Google searches for Harth’s name were about 30 times higher than they had been in April, when the Globe’s original story broke.

I had a similar haven’t-I-heard-this-one-before reaction after The New York Times published a story on Tuesday night that alleged that “members of [Trump’s] 2016 presidential campaign and other Trump associates had repeated contacts with senior Russian intelligence officials in the year before the election.” Didn’t we already know that, or at least have strong reason to suspect it? In August 2016, then-Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid wrote a letter to FBI Director James Comey asking for an investigation into ties between Russia and the Trump campaign. In October, Mother Jones and Slate published stories levelling relatively specific accusations at Trump. Then last month, Buzzfeed published a dossier, later attributed to a former British spy, that alleged that the Trump campaign had met with Russian officials, among other lurid details.

It would be one thing if Tuesday’s Times story had provided specific evidence or proof of these pre-existing claims, something those earlier stories largely lacked. But it didn’t: Their most recent story was almost entirely based on anonymous sources and was exceptionally light on specifics. In its third paragraph, furthermore, the story reported that American officials “had seen no evidence” that Russia and Trump were colluding to influence the election, only that there had been contacts between them. I’m not saying that the Times story wasn’t newsworthy, but there wasn’t really a lot there that would cause you to shift your prior views if you’d been following the news fairly carefully already.

And yet, at least as I write this on Wednesday morning, the story has blown up massively. How come? Obviously, one big reason is the timing: The story came after the resignation on Monday of national security adviser Michael Flynn, after it was revealed that Flynn had conversations with Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak about economic sanctions on Russia, contradicting claims made by White House officials. Reporters smell blood in the water — especially with Trump acting something like a wounded animal — which made the allegations about Trump and Russia seem relevant again even if they aren’t new, exactly.

It’s noteworthy that the Flynn story — which was originally reported by the Wall Street Journal on Jan. 22 — contained a lot of specifics: detail about whom Flynn had the conversations with, when they took place, and what the subject matter was. (Subsequent reporting even revealed where Flynn was when he had the conversations — at a “beachside resort in the Dominican Republic.”) The specificity of the claims made it harder for the White House to refute them: Vague denials aren’t persuasive against specific claims, but specific denials run the risk of getting you caught in a lie. The specificity also made it easier for other news organizations, such as the Washington Post, to follow up on these stories and verify or rebut the claims.

But specificity isn’t everything: Persistence matters too. The Boston Globe’s story on Harth contained a lot of specific claims, but without news organizations following up on it or cable news shows talking about it, it couldn’t metastasize into a well-known story. Even the Flynn story didn’t blow up overnight: Based on Google search traffic, Flynn drew relatively little interest from readers until late last week, even though the Journal’s story had been published on Jan. 22. Other news organizations continuing to report out the story — and the White House bungling the response to it under increasing pressure — made a big difference in how much attention it got.

The formula behind which news stories become salient — which ones dominate the news cycle for days and weeks on end versus which ones quickly fade from memory — reflects a complex interaction between news organizations (what are their incentives?), readers (what are they watching or clicking?) and the principals behind the stories (who’s pushing the story and who’s trying to rebut it?). To some extent, it may even reflect a degree of randomness and chaos stemming from herd behavior: If a few highly influential news organizations like the Times, the Post and the Journal all decide that a story is relevant, everybody else probably will too. If they throw shade on a story, conversely, it may die fairly quickly. Ironically enough, one example of the latter result comes from the story of Trump’s ties to Russia. On Oct. 31 last year, a New York Times story (“Investigating Donald Trump, F.B.I. Sees No Clear Link to Russia”) cast doubt on the Mother Jones and Slate stories that were published that same day, and the topic of Trump’s links to Russia faded from the public conversation within a few days, only to come back with a vengeance once he was elected president.

Obviously, the inherent newsworthiness of the stories can matter too. A story about Trump groping women is more likely to blow up than one that accuses him of cheating at golf. But this can be a fairly rough correlation. On the one hand, there’s so much news that it’s hard for news organizations to cover everything at once. On the other hand, low- or medium-importance stories can feed back upon themselves and receive a disproportionate amount of attention. Your mileage may vary, but — especially in light of what’s happened since — the incredible amount of coverage devoted to Clinton’s email server during last year’s campaign doesn’t hold up very well in retrospect.

Trump can also seek to influence coverage priorities, of course. During the primary campaign, his tactic of constantly changing the subject and creating shiny objects for the media to chase often proved to be highly effective. During the general election, he wasn’t always as successful at this, instead digging in on stories such as his feud with the family of American soldier Humayun Khan, which turned minor issues into medium-sized ones. Still, Trump was often bailed out by a Clinton-related story or by reporters who lost interest and went looking for another shift in the horse race.

As president, Trump might find it more difficult to avoid sustained coverage of a single issue. The stakes for every action he takes are much greater, making him less nimble. And the media’s incentives are a lot different. I’m making generalizations, but major news organizations are usually willing to take a more openly adversarial posture toward a sitting president — especially one they don’t like — than they would be toward a presidential candidate (especially one they didn’t expect to win). Many of them would regard publishing stories that led to Trump’s resignation or impeachment as the ultimate badge of honor, in fact. If there’s any chance of that happening, the media will need fire and not just smoke — and they’ll need a whole lot of persistence when Trump tries to change the subject.

February 14, 2017

So, Umm, Is The Trump Administration In Disarray?

In this week’s politics chat, we talk about how messed up the Trump administration is. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Happy

February 13, 2017

Politics Podcast: Tea Party Parallels

As anti-Trump protesters flock to congressional town halls around the country, lots of political observers are drawing parallels to the tea party protests of 2009. But are they accurate? The New York Times’s Kate Zernike joins the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast to explore the similarities and differences between the backlash against the Trump administration and the tea party movement that started in response to the Obama administration. The podcast crew also introduces FiveThirtyEight’s “Trump Score,” a tool that will help track who in Congress is most and least in line with the Trump agenda.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Clinton’s Ground Game Didn’t Cost Her The Election

If the election turned into an Electoral College showdown, Hillary Clinton had an ace in the hole — or so it was assumed. In the event of a close election, her field operation could ensure a high turnout from her base and give her a “big advantage” in the swing states, The New York Times reported on Nov. 3, in an article that contrasted Clinton’s supposedly more data-driven strategy against what it portrayed as an erratic and imprecise approach by Donald Trump:

Mrs. Clinton’s efforts are most intense in a few large swing states where balloting is underway. Guided by data on millions of voters around the country, the Clinton campaign has deployed her top surrogates to areas where she needs a boost: Mr. Obama fired up voters on her behalf in Jacksonville, Fla., and Miami, cities where black voters have yet to turn out in sizable numbers.

Seldom have Mr. Trump and Mrs. Clinton’s divergent approaches to electioneering been on more vivid display. Where Mrs. Clinton has homed in on minority turnout in early-voting states, Mr. Trump has delivered a broad-brush message denouncing Mrs. Clinton as corrupt.

Seeking to break through on an electoral map that favors Mrs. Clinton, Mr. Trump has tested his strength in unconventional places — one day in tossup states, another in Democratic-leaning states like Michigan and New Mexico, still another in states that Mrs. Clinton seemed to have locked up long ago, like Virginia and Colorado.

Mrs. Clinton’s extensive field operation gives her a big advantage over Mr. Trump, whose campaign employs a relatively meager staff and has outsourced most get-out-the-vote activities to the Republican National Committee.

Needless to say, the election didn’t work out quite as Clinton hoped. Not only did she lose seven swing states and 100 electoral votes that Barack Obama had won four years earlier — she did so despite winning the popular vote. If the hallmark of a good campaign is turning out voters where you need them most, then Clinton’s failed miserably. She received almost as many votes (65.85 million) as Obama had nationwide (65.92 million). But while she earned 900,000 more votes than Obama in California and almost 600,000 more in Texas, she underperformed him in the swing states.

So what went wrong with Clinton’s vaunted ground game? There are certainly some things to criticize. There’s been good reporting on how Clinton’s headquarters in Brooklyn ignored warning signs on the ground and rejected the advice of local operatives in states such as Michigan. And as I wrote in a previous installment of this series, Clinton did not allocate her time and resources between states in the way we would have recommended. In particular, she should have spent more time playing defense in states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Colorado and less time trying to turn North Carolina into a blue state or salvage Iowa from turning red.

Here’s the thing, though: The evidence suggests those decisions didn’t matter very much. In fact, Clinton’s ground game advantage over Trump may have been as large as the one Obama had over Mitt Romney in 2012. It just wasn’t enough to save the Electoral College for her.

There are several major problems with the idea that Clinton’s Electoral College tactics cost her the election. For one thing, winning Wisconsin and Michigan — states that Clinton is rightly accused of ignoring — would not have sufficed to win her the Electoral College. She’d also have needed Pennsylvania, Florida or another state where she campaigned extensively. For another, Clinton spent almost twice as much money as Trump on her campaign in total. So even if she devoted a smaller share of her budget to a particular state or a particular activity, it may nonetheless have amounted to more resources overall (5 percent of a $969 million budget is more than 8 percent of a $531 million one).

But most importantly, the changes in the vote from 2012 to 2016 are much better explained by demographics than by where the campaigns spent their time and money. Let me start with a couple of simple comparisons that I think pretty convincingly demonstrate this, and then we’ll attempt a more rigorous approach.

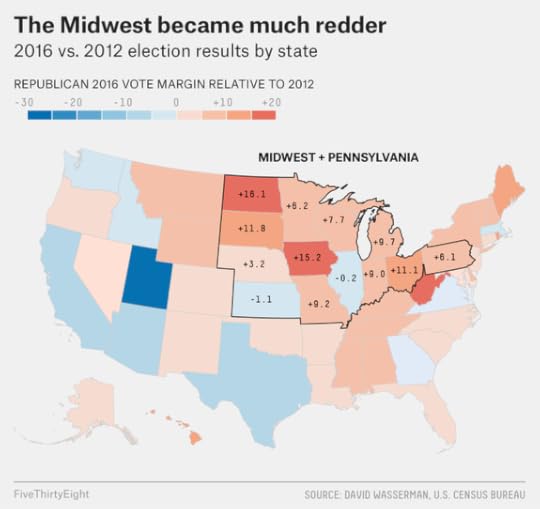

Comparison No. 1: Clinton spent literally no time in Wisconsin, whereas Trump repeatedly campaigned in the state. Wisconsin turned red. But so did Pennsylvania, where both candidates campaigned extensively. Trump’s margin of victory in each state was almost identical, in fact — 0.8 percentage points in Wisconsin and 0.7 percentage points in Pennsylvania. That strongly implies that the demographic commonalities between Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — both of them have lots of white voters without college degrees — mattered a lot more than the difference in campaign tactics.Comparison No. 2: As I mentioned, Trump campaigned a lot more than Clinton in Wisconsin, and it turned red. But Trump also campaigned a lot more than Clinton in Colorado — it actually had the largest gap of any state in where the candidates spent their time. Colorado remained blue, however, with Clinton winning it by about the same margin that Obama won it by in 2012. The difference is that Colorado has relatively few white voters without college degrees, while Wisconsin has lots of them. Again, that strongly implies that demographics rather than campaign tactics drove the shift in the results.This idea is also evident if you look at state-by-state or county-by-county maps of where the vote shifted from 2012 to 2016. Within the Midwest, for example, it wasn’t just Michigan and Wisconsin that became much redder. So did Minnesota, Indiana, Missouri, North Dakota and South Dakota, even though there was almost no campaigning by either candidate in any of them.

Another, more rigorous way to address the question is by regression analysis. Accounting for where the candidates spent their resources makes almost no difference, it turns out, once you’ve controlled for one or two major demographic categories and the 2012 vote. For instance, we can run a regression analysis to project the 2016 result in each state where the input variables are the 2012 results, the share of voters in each state who are whites without college degrees, and — it doesn’t matter much in the swing states but in order to avoid a big outlier in Utah and Idaho — the Mormon population of each state. If Clinton had an inferior ground game to Obama, we’d expect the model to overestimate her performance in swing states and underestimate it in noncompetitive states. But that’s not what it shows — instead, it replicates the actual results quite well in swing states, red states and blue states alike.

DEMOCRATIC VOTE MARGINSWING STATESWHITE NON-COLLEGE SHAREMORMON SHAREOBAMA 2012PROJECTED CLINTON 2016*ACTUAL CLINTON 2016Michigan53%+9.5+1.2-0.2Minnesota54+7.7-0.9+1.5Wisconsin57+6.9-3.3-0.8Nevada426+6.7+6.2+2.4Iowa62+5.8-6.4-9.4New Hampshire57+5.6-4.1+0.4Colorado423+5.4+3.6+4.9Pennsylvania50+5.4-1.3-0.7Virginia371+3.9+3.7+5.3Ohio53+3.0-5.0-8.1Florida40+0.9-0.8-1.2North Carolina40-2.0-3.5-3.7—Blue statesD.C.2+83.6+91.5+86.8Hawaii155+42.7+50.6+32.2Vermont55+35.6+24.0+26.4New York30+28.2+28.6+22.5Rhode Island49+27.5+19.0+15.5Maryland29+26.1+27.1+26.4California262+23.1+26.2+30.1Massachusetts40+23.1+19.2+27.2Delaware45+18.6+13.2+11.4New Jersey33+17.8+17.7+14.1Connecticut38+17.3+15.0+13.6Illinois38+16.9+14.6+17.1Maine62+15.3+2.4+3.0Washington474+14.9+10.1+15.5Oregon534+12.1+4.8+11.0New Mexico283+10.1+14.6+8.2—Red statesGeorgia34-7.8-5.9-5.2Arizona426-9.1-8.1-3.5Missouri531-9.4-16.0-18.6Indiana55-10.2-17.6-19.2South Carolina39-10.5-10.5-14.3Mississippi391-11.5-11.4-17.8Montana575-13.7-19.8-20.4Alaska415-14.0-12.8-14.7Texas311-15.8-11.7-9.0Louisiana40-17.2-17.3-19.6South Dakota551-18.0-24.4-29.8North Dakota602-19.6-28.0-35.7Tennessee48-20.4-23.7-26.0Kansas481-21.7-24.8-20.6Nebraska541-21.8-27.4-25.0Alabama46-22.2-24.4-27.7Kentucky621-22.7-32.3-29.8Arkansas541-23.7-29.5-26.9West Virginia66-26.8-37.6-42.2Idaho6026-31.9-28.1-31.8Oklahoma491-33.5-36.0-36.4Wyoming5512-40.8-40.5-46.3Utah4968-48.0-18.5-18.1Demographics explain the changes in Clinton’s performance in swing states* Projected vote is based on a regression that accounts for the 2012 vote, the share of voters in each state who are whites without college degrees, and the share of residents in each state who are Mormon.

Source: David Wasserman, Church of Latter-Day Saints

In Pennsylvania, for instance, the share of white voters without college degrees is well above average so the model expects an above-average shift toward Trump. And that’s exactly what happened, of course: Trump won Pennsylvania by about 1 percentage point, right in line with the model’s expectations. Wisconsin? Clinton’s roughly 1-point loss there is actually a tick better than the 3-point loss the regression model projects. The model also projects Michigan, Minnesota and Florida to be photo finishes, as they were. It has Trump favored in New Hampshire, which has a lot of white voters without college degrees, so that may have been a state where Clinton’s ground game did save her.

On the flip side, the regression correctly projects Clinton to roughly replicate Obama’s numbers in Colorado and Virginia, as she did — even though Trump spent much more time than she did in those states. With one or two exceptions, such as Hawaii, it also does a good job with red states and blue states — for instance, in capturing the big shift toward Trump in Maine and the one toward Clinton in Texas.

To be clear, these are after-the-fact projections done with knowledge of how the actual vote turned out, as opposed to pre-election predictions. But the regression is able to figure all of this out without giving any consideration to how Clinton and Trump spent their time and money. Instead, it can explain the Electoral College drop-off Clinton experienced relative to Obama based on some simple demographic variables and the 2012 vote alone. That suggests that either the ground game didn’t matter much — or that Clinton’s ground game advantage was as large as Obama’s was after all.

Or it may have been a combination of both: The ground game may have helped both Obama and Clinton at the margin. But studies from political scientists find the effects of a superior turnout operation to be quite modest in presidential elections — usually overwhelmed by larger, macro-level factors. In 2012, for example, the condition of the economy probably mattered more than Obama’s turnout operation. And in 2016, all the news generated by Trump and the media circus surrounding him, plus major stories like the FBI’s investigation of Clinton, tended to drown out the candidates’ efforts at a piecemeal, coalition-building approach. You certainly can criticize Clinton for choosing an overall message that didn’t sell to white voters without college degrees. That’s a high-level strategic failure, however, rather than one of her field operation or her Electoral College tactics. Not spending enough time in Wisconsin and Michigan was dumb, but probably wasn’t decisive.

So did reporters go wrong in putting so much focus on the ground game? This series hasn’t been kind to how the media covered the horse race, but I’m somewhat forgiving on this question. Personally, I find a lot of this reporting to be valuable and interesting. I’d be something of a hypocrite otherwise, since FiveThirtyEight did a fair amount of reporting on the ground game ourselves.

The error, instead, was in assuming that there was necessarily a lot of predictive information in the ground game. Toward the end of the campaign, the implication of much of the coverage of the race, especially when it came to factors such as early voting, was that Clinton didn’t need to worry about the tightening polls because her data and turnout operation would save her. That was probably a mistake because by late in the race, many effects of a campaign’s field operation are already reflected by the polls. If a Democratic canvasser successfully persuaded an undecided voter to move into the Clinton column, for instance, that voter would show up as a Clinton voter if a pollster called her. This is especially true for polls of likely voters, which can sometimes reflect the effects of a field operation by anticipating turnout patterns.

There are also plausible ways in which a field operation’s effects might be missed by the polls, such as if a campaign registered a lot of new voters and a poll used an outdated registered voter list. But as an empirical observation, it’s hard to predict the direction of polling error. If anything, when the polls have been off in recent elections, it’s been in the opposite direction of what pundits and reporters expected. One reason I find it vexing when people are quick to blame the polls for underestimating Trump is that, at least during the stretch run of the campaign, most of the arguments were about why the polls might be overestimating Trump’s chances instead.

February 8, 2017

What Really Matters From Trump’s First 3 Weeks?

In this week’s politics chat, we try to separate the important, lasting storylines from the first three weeks of Donald Trump’s presidency from the more trivial, ephemeral ones. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Hey, friends.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): We have fewer friends than usual since Clare is “traveling” for “work.”

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): For the record, Clare is traveling for work. (No scare quotes necessary.) Nate, do you want to set up this chat since it was your idea and I don’t really get it?

natesilver: You said it was a good idea and you didn’t know what the idea was?

micah: I like the idea, but intro-ing it involves setting up the main questions and narrowing the conversation.

natesilver: Well, the big question is what matters so far from the first three-ish weeks of the Trump administration and what doesn’t. Which storylines are going to have staying power and shape the country and the presidency? And which are just shiny objects?

micah: Separating the signal from the noise, if you will. #book-plug

natesilver: Human beings have to make plans and strategize for the future. As the pace of our lives becomes faster and faster, we have to do so more often and more quickly. But are our predictions any good? Is there hope for improvement? How can we separate … the Signal from the Noise?

(That’s actually lifted from my book jacket.)

micah: OK, so let’s tackle that first question first: What storylines from the first three weeks of the Trump administration will have staying power/really matter long term?

We each get one “signal” nomination and one “noise” nomination. Harry, you get the first signal nomination.

harry: Well. I think there are many different stories. It’s been a busy few weeks. I’d argue that Trump’s inability to communicate well with Congress is a big one. I think that’s a signal.

micah: What do you mean by “inability to communicate well”?

harry: There clearly was no communication with Congress when it came to some of his executive orders. Congressional Republicans were taken aback. And since you need Congress to pass bills, it seems to me to be a problem.

natesilver: That’s definitely one of the 7,102 most important storylines so far. I’d rank it right ahead of Trump’s bathrobe.

micah: Hmmm … I’d be more willing to label that #signal if you widened it to include a lack of consultation with everyone outside a small group in the White House. Basically, is the White House’s policy process broken?

harry: What I’m arguing is: Yes, Trump has signed some stuff, but what seems to be the problem here is that Trump has shown no ability to use the system.

micah: So, I’d vote for “Trump’s isolated, ad hoc decision-making process” as being one of the real storylines of the first few weeks that could have a lasting impact. Although, the administration could easily get better at this.

harry: He is acting like he did during the campaign and relying on a small group of people with little outside help. That (i) leads to policy that clearly hasn’t been run through the ringer and (ii) makes congressional Republicans mad.

micah: Nate, you’re not buying even that broader storyline?

natesilver: I’m not sure what to think of it because those stories are based so heavily on anonymous sourcing. And it’s like there are so many things going on in plain sight.

micah: OK, Nate with nomination No. 2 …

natesilver: I think this tweet sort of sums it up:

Just cannot believe a judge would put our country in such peril. If something happens blame him and court system. People pouring in. Bad!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 5, 2017

micah: Tweeting? That’s your storyline?

natesilver: No, not the tweeting. Oh god no. NO!

micah: Trolling Nate is fun.

natesilver: I picked that tweet because there are actually THREE storylines in one here. It’s like neopolitan (sp?) ice cream.

harry: Side note: I got that type of ice cream this weekend and had it with cool whip. Please continue though.

natesilver: The three storylines:

Trump’s executive order on immigrants and refugees itself has a pretty substantive policy impact.Trump is prepared to battle — or undermine — the judicial branch if he isn’t getting his way.Trump is tipping his hand as to a strategy if/when “something happens,” e.g. a terrorist attack, and is very likely to exploit it to expand his powers.micah: Hmmm. I generally buy all that, but you’re ascribing an awful lot of meaning to a Trump tweet. I’m not sure that much deliberation went into that tweet.

natesilver: It’s not the tweet, Micah. It’s just that the tweet encapsulates some of the most important things going on so far.

micah: Has the administration gone to battle with the judicial branch? There were scattered reports of Customs and Border Protection officials disregarding court orders, but Homeland Security complying with a federal judge’s ruling halting the travel ban. Vice President Mike Pence said the right things about the judge’s ruling.

harry: Right.

micah: Basically, my question is how much evidence is there outside of Twitter for storylines No. 2 and No. 3?

natesilver: I’m more thinking ahead a couple of steps. It seems very likely to me that an actual or apparent terrorist attack will become the focal point for how Trump’s presidency develops. And that he’ll use it as a pretext to go to battle with the judicial branch.

It might be true that there’s more smoke than fire right now. However, he’s only been on the job for three weeks, and Trump has a pretty good track record of following through on his promises/threats when he gets the chance.

micah: OK, I get it. But there is a chance that turns out to be noise. We don’t know it’s signal as of yet.

harry: Man, Micah brought his big boy pants today.

harry: Trump has gone after a judge before. I don’t know if that means we should take him more or less seriously.

micah: No, that’s true. That suggests we should take him more seriously now.

natesilver: I mean, the probability of an actual or thwarted terrorist attack in the U.S. or in some NATO country over the next year or so has to be quite high. I’m not talking about something on a 9/11 or a Paris scale or anything like that, but something scary enough for Trump to use it as a cudgel to try to expand his powers.

micah: OK, my turn.

Signal nomination: The main check on Trump will be the courts, not Congress.

harry: I agree 100 percent on this based on what’s going on right now.

natesilver: I agree 99.9999999 percent. Don’t get overconfident, Harry.

harry: I’m sorry.

natesilver: But, yeah, Republicans in Congress have near-unanimously sided with Trump on every vote so far.

micah: OK, so if you look at our Trump Score tracker, even Republican senators and representatives from purple states and districts have supported the Trump position pretty uniformly. There are 17 Republican senators from states Trump either lost or won by less than 10 percentage points. Sen. Susan Collins of Maine (which Trump lost by 3 percentage points) has supported the Trump position about 82 percent of the time. The other 16 have supported Trump 100 percent of the time:

The dynamic in the House is similar.

natesilver: There really aren’t many signs of resistance at all. Cory Gardner and Dean Heller are from states Hillary Clinton won, and they’ve voted with Trump 100 percent of the time so far. Rep. David Valadao is from a California district that Clinton won by 16 points, and he’s voted with Trump 100 percent of the time.

Some rhetoric on the Sunday morning shows. But a lot of talk and very little action.

harry: Agree entirely with that. It’s actually record-breaking how much they’ve agreed with him so far. (More on that later on FiveThirtyEight.com.)

micah: Right. There’s still a chance that changes, depending on what Trump does. And there’s certainly been popular resistance to Trump. The Women’s Marches were one of the biggest demonstrations in U.S. history (perhaps the biggest). Trump’s immigration order also sparked protests. But those public demonstrations haven’t yet been enough to get Republican elected officials to break ranks. From the primary to the general election to the first few weeks of Trump’s presidency, all signs point to Republicans backing Trump. That goes for voters and elected officials, btw.

natesilver: A good heuristic for “Is Trump’s presidency in crisis?” is that it isn’t until Republicans in Congress begin to offer substantive resistance to him. So far that HASN’T happened. Which is why I’m suspicious of those “Trump in disarray” narratives that have become popular with the kids these days.

harry: Congress is merely reflective of voters right now.

micah: Drop some data on us, Harry.

harry: Take a look at the most recent national Quinnipiac poll: Trump has an 88 percent approval rating among Republicans.

Now if you want a sense for what it looks like when a presidency is really in trouble, look how Republicans in Congress were acting in 2007 and 2008. In 2007, the average House Republican voted with Bush 75 percent of the time, as calculated by Congressional Quarterly. In 2008, 68 percent of the time. Right now, we’re at 98 percent!

natesilver: I do just wanna point out that the electoral incentives to support Trump so uniformly are not clear for guys like Gardner and Valadao. The general election risk probably outweighs the threat of a primary challenge for them. So their 100 percent support seems to reflect something else — an effective job of whipping by Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan, or a fear of being targeted by Trump for standing out from the crowd, or both.

harry: Or maybe they just agree on what he’s presented so far?

micah: I mean, yeah, Congress has mostly voted on confirmations and typical GOP policy stuff so far.

natesilver: That’s fair enough.

micah: OK, Nate, give us your nomination for biggest “noise” storyline so far.

natesilver: Maybe this is too easy, but I think most storylines involving Trump and the media are noise.

micah: Wait — spell that out a little more. There’s one version of that argument I agree with. There’s one I 100 percent do not agree with.

natesilver: I’m referring to parochial stuff like who gets called on at press briefings and so forth. There’s probably a little too much obsession with Sean Spicer and Kellyanne Conway too.

harry: The fact that Spicer has become such a big talking point that he became a segment on “Saturday Night Live”?

natesilver: I certainly think the Trump administration’s communication and media strategy is important, and sort of fascinating, to study. And there are a lot of questions the media ought to be asking itself about how to cover the White House. But I don’t think the personalities matter very much and a lot of it is just gossip.

micah: I agree that the “who get’s called on” stuff or “where the press room is” in the White House is noise. And I agree that there’s too much reliance on Spicer, Conway, etc. But I think it’s good that the press is starting to question whether having Conway or Spicer on TV is good journalism.

natesilver: We could have a whole chat about good and bad things in how the media has covered Trump so far. As I said before, I’m pretty concerned about the reliance on anonymous sourcing, which seems worse than ever. And people have made some errors in rushing into stories before confirming facts and details. On the other hand, there’s been a big surge of interest in journalism. And some of the niceties breaking down — such as in not having Conway on TV quite as much — are long overdue.

But something like the “White House rattled by McCarthy’s spoof of Spicer” storyline feels to me like a case where there’s probably a small grain of truth, but it’s also been exaggerated by a potent mix of liberal/media wish fulfillment and anonymous sourcing.

harry: That’s merely a continuation of the long-standing meme of “John Oliver CRUSHES [insert name here].”

Now perhaps with Trump, it’s something more. He appeared to respond to an “SNL” skit, on Twitter. But I tend not to think that influences policy at all.

micah: Harry, your noise nomination please.

harry: Here’s mine: The idea that the Trump presidency has been a disaster. I think that’s noise. Some people see how he’s had problems after signing the executive orders and think Trump has lost. But the fact is that (i) all of Trump’s Cabinet nominees who have come up for a vote have been approved; (ii) Republicans are voting with him in record numbers; and (iii) Trump’s executive orders have had major policy implications, in some instances. You can phrase that differently, but I think a lot of people see problems with Trump’s communications (which are real) and think his administration has been ineffectual. But look at the scoreboard. The Trump administration can simultaneously be a communications disaster, wrapped in scandal and still have real-world impact on its policy goals.

natesilver: I basically agree with this, although there’s more robust evidence now that his approval ratings are declining.

harry: I think that’s true about his approval ratings — though, those can change. From a policy standpoint — and keep in mind that we’re still nearly two years away from the 2018 midterm elections — Trump isn’t losing.

micah: Yeah, I think this is all right.

natesilver: Let’s take you behind the curtain here at the FiveThirtyEight politics chat. Harry edited his comment from “Trump is winning” to “Trump isn’t losing,” which nullified my whole reply.

harry: Prove it.

natesilver: Because “he’s winning” probably isn’t right. His signature executive order has been knocked down by the courts (for now). His popularity wasn’t very good to begin with and is declining. Democrats in Congress are resisting him in record numbers, even though Republicans are voting with him in record numbers. There’s a lot of liberal political activity, like at the women’s marches, and that stuff can have pretty big implications down the road. The raid in Yemen doesn’t seem to have gone well, and there have been some minor (only minor so far) dust-ups with American allies.

So you can definitely say that Trump has let the other team put a few points up on the board.

And you can make a pretty reasonable case that he is losing, in fact — that things are going slightly worse than expected, even if your expectations were fairly low.

However, it isn’t a blowout, and some of the narratives are very wrongly treating it as one.

harry: Let me put it this way: I’m not sure there is a clear sign that Democrats are winning. Battles may be won or lost, but the war carries on.

natesilver: That’s fair. Democrats haven’t gotten very many wins. And as we discussed last week, they don’t seem to have a strategy at all on Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch.

On the other hand, Democrats are out of power, and it’s hard for the party out of power to accomplish much when the other party is toeing the party line. So to some extent, it’s not Democrats but Trump himself who’s his own worst enemy.

micah: OK, let’s wrap this up with my noise nomination.

This is a tricky one because there’s a good deal of signal here too, but I’m going with … LEAKS!

natesilver: I thought you were gonna go with the Ivanka Trump/Nordstrom storyline — that would have been another good “noise” one.

micah: That seemed too obvious.

So obviously there are essential leaks that provide invaluable information about what’s going on behind the doors of the White House and administration agencies. But there have been so many leaks so far that it’s very hard to figure out what matters and what doesn’t.

harry: Forget what matters and what doesn’t matter. It’s also hard to figure out what’s real and what isn’t real. The anonymous sourcing, as Nate pointed out earlier, is rampant.

natesilver: Yeah, especially when “senior White House official” could mean anything from an intern to Trump himself.

Like those stories about how Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump heroically fought back against Trump’s purported LGBT executive order seemed to represent the Jared and Ivanka point of view in a way that I’d have found very pleasing if I were Jared and Ivanka.

And some of the stories alleging that [Bannon/Spicer/insert name here] are falling out of favor with Trump seem like they might be planted by people who want [Bannon’s/Spicer’s/insert name here’s] job.

I’m also sure that some of the stories are true and super important. But it’s kind of like the old adage: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.” I assume that half of the inside-the-White House stories based on anonymous sourcing are basically bullshit, but I don’t know which half.

harry: One of the key things here is that they’re all leakers. Trump is probably leaking too. Or trying to.

natesilver: So do we think it’s significant that there have been so many leaks (even if some of the leaks themselves are self-interested gossip)?

micah: That does seem significant. Basically a whole chunk of the executive branch has said “fuck it.” Because they don’t like Trump.

harry: It shows a lack of discipline within the administration. The Obama White House, by contrast, managed to keep leaks to a minimum.

micah: Well, Obama went after leakers pretty ruthlessly.

harry: It goes back to my original “signal” nomination — that Trump is relying on a small group of folks and not running more stuff through the system.

micah: You mean my edited version of your signal nomination.

natesilver: We’re gonna make the next politics chat a LIVE chat, Harry.

micah: That’d be terrifying.

OK, last thoughts?

harry: Buy Nate’s book? … I’m kidding. When we are looking for signal going forward, the question you have to ask yourself is: “Does this have real-world policy implications?” Or, “Will this affect everyday people?” If the answer is “no,” it’s probably noise. If “yes,” then you might have yourself a signal.

Folks, a little inside information: Nate’s been typing for about 37 hours now. I hope his response is the greatest ever.

natesilver: I guess I’d just say … we all agree that Trump has had some successes and some failures so far. I might even say that the media is overlooking some of the successes, like Trump’s support from Republicans in Congress. But I’d be careful with the idea that Trump’s presidency is all just sort of averaging out to a Mark Halperin C+ grade or something. There are a LOT of ways this presidency could turn out, including some tail risks where some pretty crazy things happen.

harry: Nice plug for the article. Granted, I do agree. I’ve been emphasizing when I talk with people that it could get crazy at any point. Or it could just not. Anything is on the table.

natesilver: And to some extent, it’s important for everybody to keep those tail risks in mind as they report on the daily goings-on. Trump’s tweet about Nordstrom is probably not going to lead the country to a deep and dark place, even if conflicts of interest are a real issue. His tweet that openly says you should blame the court system when the next terrorist attack/bad thing happens is a much bigger deal, on the other hand.

February 7, 2017

The Super Bowl Wasn’t Really Like The Election

It’s time for some probability theory. Imagine you’d passed out on Lime-A-Ritas before kickoff on Sunday night and woken up in a cold sweat at 3 a.m. to read the headline, “New England Patriots win 34-28.” That would have been about the least surprising Super Bowl result imaginable. The Patriots were favored before the game according to Vegas betting lines and FiveThirtyEight’s Elo projections, and it was expected to be high-scoring.

But, oh, what drama you would have missed! The Patriots overtime comeback from a 28-3 deficit made for perhaps the most exciting Super Bowl ever, as well as one of the largest comebacks in NFL history, Super Bowl or otherwise. You have to watch a lot of football games to see something like that happen.

If your social media feeds are like mine, they contained a blurry mix of politics and sports on Sunday night. So as the Atlanta Falcons collapsed, there were a lot of people (myself included!) comparing them to Hillary Clinton and the victorious New England Patriots to Donald Trump. But Super Bowl Sunday and election night weren’t really very much alike. On one of them, something highly unlikely occurred — and the other was pretty much par for the course.

The truly unlikely event was the Patriots’ epic comeback. According to ESPN’s win probability model, their chances bottomed out at 0.2 percent in the third quarter, when they trailed 28-3. By contrast, Trump’s chances were 29 percent on election morning, according to FiveThirtyEight’s polls-only model. Those are really different forecasts; if you trust the models, Trump’s Election Day victory was more than 100 times likelier than Tom Brady’s comeback.

Of course, there are a few things to debate here. For instance, Trump’s overall rise to the presidency — from the moment he descended the elevators at Trump Tower onward — is still astonishing, even if he was only a modest underdog on Election Day itself.

And on the football side, one can argue about exactly how unlikely the Pats’ comeback really was. As I mentioned, according to ESPN’s win probability model, the Falcons’ chances topped out at 99.8 percent. Their chances were slightly higher still according to the Pro-Football-Reference.com win probability model, reaching 99.9 percent at several points in the third and fourth quarters. Conversely, the Falcons’ odds peaked at about 96 percent according to Las Vegas bookmakers.

While 96 percent might not sound that different than 99.9 percent, consider the numbers in terms of odds: It’s the difference between a 1-in-25 chance of a Patriots’ comeback and a 1-in-1,000 chance. (I’d recommend this “trick” as a sanity check whenever you encounter a probabilistic forecast — restate the probability in terms of odds. That usually makes it much clearer how far out you’ve ventured onto the edge of the probability distribution.) In the context of a football game, maybe that doesn’t matter very much. But it’s crucially important to distinguish a 1-in-25 chance from a 1-in-1,000 chance in life-and-death matters, such as when considering a risky medical procedure or assessing the likelihood of an earthquake in a given region.

For various reasons, ranging from p-hacking, to survivorship bias, to using normal distributions in cases where they aren’t appropriate, to treating events as being independent from one another when they aren’t — that latter one was a big problem with election models that underestimated Trump’s chances — people designing statistical models tend to underestimate tail probabilities (when probabilities are close to zero, but not exactly zero). Perhaps not coincidentally, people also tend to underestimate these probabilities when they don’t use statistical models. It’s not always the case, but it’s often true that when a supposedly 2 percent or 0.2 percent or 0.02 percent event occurs, the “real” probability was higher — perhaps even an order of magnitude higher. Maybe an ostensibly 1-in-500 event was really a 1-in-50 event, for instance.

Sports models are sometimes exempt from these problems because sports are data-rich but structurally simple, which makes modeling a lot easier. Still, it’s noteworthy that Super Bowl bettors were picking up on something that the models weren’t considering. Should the models have done more to account for the quality of the trailing team’s quarterback (i.e., some sort of Tom Brady clutch factor?). Should Super Bowls be treated differently from other sorts of football games? (I make a case here that Super Bowls might be different from regular-season games.) These models have also been somewhat overconfident historically, according to Josh Levin at Slate. I don’t know enough about the nuts and bolts of NFL win probability models to render a firm judgment either way, but these would be things to think about if your life depended on whether the Patriots’ chances were really 0.1 percent or 4 percent.

Nonetheless, even if the models didn’t get things quite right, it was almost certainly correct to say that history gave the Patriots long odds. We can be confident about this because of the basic gut-check that I described before: There have been lots of NFL games, and comebacks like the one the Patriots made have been very rare. For example, according to the Pro-Football-Reference.com Play Index, there have been 364 games since 1999 (not counting Super Bowl LI) in which a team trailed by between 24 and 27 points at some point in the third quarter. (The Patriots trailed by 25.) Of those, the trailing team came back to win in only three games, or 0.8 percent of the time. There are various aggravating and mitigating factors you’d want to consider for Super Bowl LI — like that the Patriots had Tom Freakin’ Brady — so I’d guess that those models had New England’s chances too low. Even so, the Pats’ comeback required near-perfect execution, as well as some uncanny luck.

But for the election? That empirical gut-check you can often use for sports — that we’ve been in this situation hundreds or thousands of times before and that we know from history that it almost always turns out a certain way — doesn’t really work. For one thing, there’s not much data. Presidential elections are rare things; FiveThirtyEight’s model was based on only 11 previous elections (since 1972), and others were based on as few as five elections (since 1996). Furthermore, despite the small sample size, there were a fair number of precedents for a modest polling error that would nonetheless be large enough to put Trump into the White House. (In the end, Trump beat his polls by only 2 to 3 points in the average swing state, but that was enough to win the Electoral College). That’s why we thought it was sort of nuts to give Trump less than a 1 percent chance or a 2 percent chance on election morning, where some other models had him. Those were less empirically driven probabilities than adventurous extrapolations drawn from thin data.

All right, I don’t want to relitigate the election model wars. Besides, there are some more interesting questions here, such as whether supposedly low-probability events are happening more often than they “should” happen. I don’t mean to suggest that there’s been some sort of a glitch in the matrix. (Although if a 16-seed wins the NCAA tournament, I’ll be ready to conclude that the people who designed the Planet Earth simulation are just toying with us.) But it’s worth asking whether statistical models are systematically underestimating tail risks or if this is just a matter of perception.

My answer is probably some of both. On the one hand, people — and I don’t just mean Twitter eggs or your 6-year-old nephew, but lots of well-credentialed people who ought to know better — don’t really have a strong grasp of probability. A 20 percent chance is supposed to occur 20 percent of the time, for instance. That’s not anywhere close to being a tail risk; that’s a routine occurrence (20 percent of weekdays are Mondays).

A 20 percent probability is really different from a 2 percent probability, however, and really, really different from an 0.2 percent probability. We’re not talking about some fine point of distinction; lumping them together is like equating a carrot to a cheetah because they’re both organisms that begin with the letter “c.”

The further a model gets out on the tail of the probability distribution, the more evidence you ought to demand from it — and the more you ought to assume it was wrong rather than “unlucky” when a supposedly unlikely event occurs. To say something has only a 0.2 percent chance of occurring is a really bold claim — in some sense, 100 times bolder than saying it has a 20 percent chance. To be credible, claims like these require either a long track record of forecasting success (you’ve made hundreds of similar forecasts and they’ve been well-calibrated) or a lot of support from theory and evidence. In the hard sciences — and sometimes in sports — you often have enough data (and strong enough theoretical priors) to defend such claims. But it’s rarer to encounter those circumstances in electoral politics, economic forecasting and many other applications involving social behavior.

So if it seems like a lot of crazy, low-likelihood things are happening, some of it is selective memory — focusing on the highly memorable times the long-shot probability came in and ignoring all the boring ones when the favorite prevailed. And some of it is people plugging things into the narrative that don’t really fit. Some of those crazy happenings, however, were never quite as unlikely as billed.

February 6, 2017

Donald Trump Had A Superior Electoral College Strategy

This is the sixth article in a series that reviews news coverage of the 2016 general election, explores how Donald Trump won and why his chances were underrated by the most of the American media.

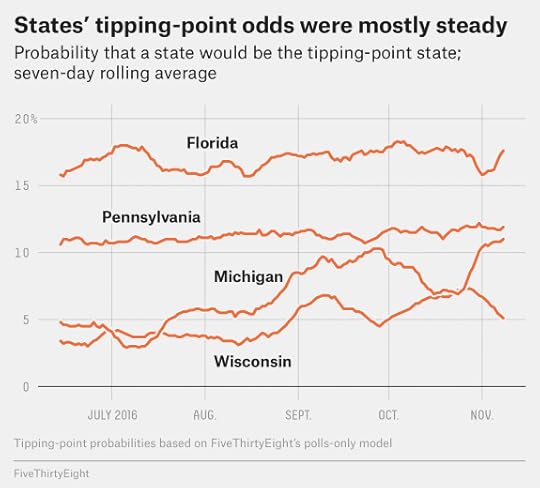

By one measure, Wisconsin was the most important state in the nation in November. According to FiveThirtyEight’s tipping-point calculation, it was the state that put Donald Trump over the top to 270 electoral votes and the White House. (Or at least arguably it did: Pennsylvania has a competing tipping-point claim.) So here’s an interesting question: How many times did Hillary Clinton visit Wisconsin during the general election? The answer: Zip, zilch, nada. She didn’t set foot in the Badger State after losing the Democratic primary there to Sen. Bernie Sanders in April.

So, case closed, right? Clinton had an incompetent Electoral College strategy and maybe even blew the election because of it? Well, yes and no. She probably should have campaigned in a broader range of states. In particular, she should have spent more time in states, such as Wisconsin, where she was narrowly leading in polls but that had the potential to flip to Trump if the election tightened, as it did during the final 10 days of the campaign.

This very probably didn’t cost Clinton the election, however — and the importance of Electoral College tactics is probably overstated in general. I’m going to save that discussion for the next article in this series, but in the meantime … I come in praise of Trump’s Electoral College approach and in criticism of Clinton’s. Indeed, Trump was pretty close to having an optimal Electoral College strategy as judged by our tipping-point calculation. Clinton made a couple of mistakes, meanwhile. So did campaign reporters, who usually lauded Clinton’s strategy while maligning Trump’s, making essentially the same errors that the Clinton campaign did.

Which states did the candidates consider to be most important? Perhaps the best gauge is simply where Clinton and Trump spent their time. Clinton’s campaign (less so Trump’s) had enormous resources to spend on television advertising, enough that she probably encountered diminishing returns among swing-state voters who had seen as many of her commercials as they could stand. Candidate visits, however, are the ultimate scarce resource. No matter how much money or how many staffers you have, you’ll only have one Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump.

Here, then, is how the candidates distributed their time from Sept. 1 through the day before the election, based on the share of their public events that occurred in each state. (Note that Trump overall was a considerably more active campaigner than Clinton, holding 105 events to her 70 during this period.) For comparison, I’ve listed how likely each state was to be the tipping-point state, based on how it ranked on average from Sept. 1 to Nov. 7, according to our polls-only model.

SHARE OF PUBLIC APPEARANCES,SEPT. 1 TO NOV. 7STATETIPPING-POINT PROBABILITYCLINTONTRUMPFlorida17.4%20.0%18.1%Pennsylvania11.511.411.4Michigan9.04.35.7North Carolina8.614.311.4Ohio8.211.49.5Colorado6.11.47.6Wisconsin6.10.02.9Virginia5.70.03.8Minnesota4.50.01.0Nevada3.24.34.8New Hampshire2.54.36.7Arizona2.51.41.9Georgia2.00.00.0Iowa1.94.32.9New Mexico1.50.01.0Trump probably had a better tipping-point strategy than Clinton

Tipping-point probabilities based on FiveThirtyEight’s polls-only model

Sources: Conservative Daily News, HillarySpeeches.com.

One thing to notice is that Clinton and Trump’s strategies are not all that different. Clinton has been criticized for not spending enough time in Michigan, for instance, but on a percentage basis, she spent only slightly less time there than Trump did.

Still, Trump’s strategy was closer to the one we would have recommended. There were two major errors, from our standpoint, in Clinton’s approach.

Error no. 1: Clinton focused too much on close states rather than tipping-point states. On average from Sept. 1 through Nov. 7, the closest states in our polls-only model were Ohio, Nevada, North Carolina, Iowa and Florida. And yet Clinton spent more time in these states than she should have. A combined 54 percent of Clinton’s events (and 47 percent of Trump’s) were held in these states, whereas there was only a 39 percent chance that one of them would be the tipping-point state.

How can it have been a mistake for Clinton to focus on these states when they were so close? In a nutshell, they weren’t “must win” states for her. On average during this period, Clinton was projected to win roughly 310 electoral votes. A slightly Republican-leaning state such as Ohio might easily have given Clinton her 300th or 320th electoral vote in the event of a clear win nationally. But others, like Pennsylvania, were more likely to provide the decisive 270th electoral vote, and that’s what the tipping-point calculation measures.

A good rule of thumb is that tipping-point states are those polling closest to the national average. Before FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress, for instance, Clinton’s lead in Michigan had been roughly 6 percentage points. She was up by about the same amount in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. But she was leading nationally by about 6 points, also. Therefore, states like Michigan were actually good ones for Trump and Clinton to campaign in, on the prospect that they’d become competitive if the race tightened, as it did — better than states like Ohio or Iowa, which were closer at that moment but further from the tipping point.

It’s also the case that the best defense is sometimes a good offense. Florida and North Carolina might not have been must-win states for Clinton, but they potentially were must-wins for Trump. So it wasn’t a bad idea for her to be spending some time in them. In general, however, the correct strategy for a candidate with an overall Electoral College lead can be surprisingly conservative, involving spending time and money in states that seem fairly safe but that could slip in the event of a shift in the race or systematic polling error. In Clinton’s case, that would have included more time in states such as Michigan, Wisconsin and Colorado.

Error no. 2: Clinton was overconfident and campaigned in too narrow a range of states. Clinton played a considerably narrower map than Trump did. In addition to Wisconsin, she also skipped Virginia, Minnesota and New Mexico during the closing stages of the campaign; Trump visited all of those states. And she spent much less time than he did in Colorado.

Apart from Wisconsin, Trump didn’t win any of these states (although he came close in Minnesota). But he had more or less the right strategy given the overall uncertainty in the race. The point is not that candidates are supposed to be clairvoyant — that it should have been obvious to Trump and Clinton that they needed to campaign in Wisconsin but didn’t have to worry about Colorado, for instance. In an alternate reality, college-educated suburbanites — instead of whites without college degrees — might have shifted toward Trump late in the race, narrowly putting him over the top in Colorado. It’s precisely because the polls can be wrong in ways that you don’t anticipate — and because news events can shift them in unpredictable ways — that you want to play a fairly broad map.

Why did the supposedly data-savvy Clinton campaign make these mistakes? Perhaps because they’re easy mistakes to make. I’m sure that it had highly sophisticated forecasts and models of the campaign and has a rigorous understanding of concepts such as tipping-point states. But for both technical and nontechnical reasons, it’s much easier to build an overconfident model than an underconfident one. This can especially be the case when you rely on proprietary data, such as internal polls. As I’ll describe in a future article in this series, it’s not clear that internal polls are better than public polling averages. If campaigns wrongly believe that they’ve solved the riddle of polling, they might make overconfident decisions, going “all in” on certain strategies instead of diversifying their approach.

Furthermore, decisions about where to spend time and money aren’t made in a vacuum. Like any other kind of organization, campaigns are subject to internal politics and potentially misaligned incentives, and their decisions can be influenced by outside groups, such as donors and the media. Making the technically correct decision may not be easy if it contradicts the conventional wisdom, and correct Electoral College strategy (i.e., not necessarily campaigning in the closest states if they aren’t near the tipping point) is often slightly counterintuitive.

Speaking of the conventional wisdom, we should talk some about how the media covered Clinton’s and Trump’s Electoral College tactics. Being among the most technical aspects of the campaign, this was generally not a strength of mainstream coverage. For instance, on Oct. 30, The New York Times jabbed at Trump for “campaigning well outside the traditional band of states that decide presidential elections,” including in New Mexico and Michigan, “two solidly blue states where polling has shown Mrs. Clinton with a clear lead” — failing to recognize that they were potentially tipping-point states even if Clinton was ahead there. A few days later, on Nov. 3, the Times criticized Trump for campaigning in too wide a range of states:

Rather than wielding data and turnout machinery as tools, Mr. Trump has instead battered at the political map in a less discriminating way, trying to shift the national race a point or two in his favor and perhaps find a soft spot in Mrs. Clinton’s support.

This was, it would turn out, pretty much exactly the strategy that swung the Electoral College to Trump. The national race tightened by a percentage point or two — actually a bit more than that after Comey’s letter to Congress — and Trump found a soft spot in Clinton’s support in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. As you read appraisals that second-guess Clinton campaign’s tactics, keep in mind that reporters often had the same blind spots. Trump was also often scolded by pundits and analysts for campaigning in the very states that would win him the presidency.

To some extent, the media’s misconceptions about Electoral College strategy and Clinton’s errors may have reinforced one another. For the most part, decisions about where to allocate resources should be determined by where states line up relative to one another. Typically, news events produce similar changes in lots of states at once, so even a major shock (say, Comey’s letter or the release of Trump’s “Access Hollywood” tape) won’t change the correct Electoral College approach all that much. The chart below provides some examples of how states’ tipping-point probabilities were fairly steady, even with all the ups and downs of the campaign.

Despite this, the media tended to read these tactical decisions as revealing a candidate’s absolute strength, rather than the relative importance of the states. A foray into traditionally Republican Arizona, for instance, would be read as a sign of strength for Clinton while a trip to traditionally blue Wisconsin would be seen as an admission of weakness. If a candidate was too concerned about her media clippings, that could inhibit correct decision-making. One wonders whether the reason Clinton never totally abandoned Iowa, for instance — even though she rarely polled well there and it was highly unlikely to be the tipping-point state — is because doing so would have occasioned a media freakout.

Conversely, Trump’s data team wasn’t likely to get a lot of credit from the media almost no matter what it did. With rare exception, reporters tended to portray Trump’s Electoral College strategy as being whimsical and haphazard, even when it was doing some pretty smart things. That may have helped Trump’s team to shut out the noise and maximize its candidate’s chances of winning the election.

Politics Podcast: Trump vs. The Judge — Vol. II

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew discusses the long-term effects of President Trump’s attacks on a federal judge who temporarily blocked his executive order halting immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries and suspending the acceptance of any refugees. Then, in this week’s edition of “good use of polling or bad use of polling,” the team assesses Trump’s bold claim that “any negative polls are fake news.” FiveThirtyEight’s Ben Casselman also joins the show to explain Trump’s framework for pulling back financial regulations, as well as how businesses have reacted to Trump’s travel ban and threat to levy tariffs against Mexico.

The podcast is exploring the directions of the two major political parties in the Trump era in a new mini-series called “Party Time.” New episodes publish on Thursdays throughout the month of February.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

February 3, 2017

Is It Time To Bring Back The Hartford Whalers?

It was one of the best logos in all of sports. A green “W,” and a blue whale’s tail, neatly using the negative space to form an “H,” as in “Hartford Whalers.” Unfortunately, they don’t give out Stanley Cups for graphic design. The Whalers didn’t have a lot of success on the ice, winning just one playoff series in 18 NHL seasons before moving to North Carolina and becoming the Carolina Hurricanes before the 1997-98 season.

But now there’s a chance the Whalers could resurface. The state of Connecticut is pursuing the New York Islanders, who are in danger of being kicked out of their woefully inadequate arena at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. The team would play at the XL Center in Hartford, the Whalers’ former home.

How successful might Whalers 2.0 be? In a 2013 study, I estimated that about 175,000 avid NHL fans live in the Hartford-New Haven metro area. That sounds bad, though it’s comparable to or slightly better than some of the lower-tier American NHL markets, including Columbus, Raleigh-Durham, Miami and Nashville (and better than Las Vegas, where the NHL is expanding). Furthermore, there’s potentially room for growth. According to our estimates, 7 percent of adults in the Hartford metro area were avid NHL fans in 2013. But the percentage is 13 percent in the New York metro area and 17 percent in the Boston metro area. If the Islanders or another team were to relocate to Hartford, the numbers would probably improve. The Hartford-New Haven media market is the largest in the U.S. without a “big four” sports franchise. But it’s only about one-eighth the size of New York’s media market (which includes Long Island and Northern New Jersey).

Of course, the NHL’s last stint in Hartford didn’t exactly end successfully. Between the 1989-90 and 1996-97 seasons, the average NHL team’s revenues more than doubled, increasing from $22 million to $52 million, according to estimates from Forbes and Financial World magazines. But the Whalers’ revenues didn’t increase at all during this period, flatlining at about $25 million. That doesn’t adjust for inflation, so their income actually decreased on a real basis.

Then again, fans weren’t exactly being treated to great hockey — and the trade of star Ron Francis and the talk of relocation didn’t help to build goodwill either. In the 1989-90 season, the Whalers had a slightly above-average 38-33-9 record and also earned slightly above-average revenues. But things went underwater from there: the Whalers never had a winning season again.

The question is whether the Islanders would be better off with one-eighth of a loaf in New York or a market to themselves in Connecticut. Considering the popularity of the New York Rangers (and the presence of the New Jersey Devils), the inadequacy of the Barclays Center for hockey, and all the other competition for the fans’ entertainment dollar in New York, it’s probably a pretty close call.

14 Versions Of Trump’s Presidency, From #MAGA To Impeachment

When faced with highly uncertain conditions, military units and major corporations sometimes use an exercise called scenario planning. The idea is to consider a broad range of possibilities for how the future might unfold to help guide long-term planning and preparation. The goal is not necessarily to assess the relative likelihood of each scenario so much as to keep an open mind so you’re not so surprised when events don’t develop quite as you’d expected.

This technique might be useful in the case of President Trump. He’s made so much news in his first two weeks that it feels as though he’s been president for two months — or two years. I worry that we, the community of Trump-watchers, may be making too many extrapolations from this small sample of data and have become too narrow-minded in our efforts to imagine what might come next. Play with a few variables — such as Trump’s relationship with Republicans in Congress, his approval ratings, and whether he’s a real authoritarian or just sort of a troll — and you’ll soon find yourself wandering down some interesting paths in which Trump’s presidency is variously a stunning success or a threat to the future of the American Republic — or both at once.

Take David Frum’s recent article at The Atlantic (“How to Build an Autocracy”) about one possible future Trump could build, for instance. Frum doesn’t rely on a straight-line extrapolation of what we’ve seen from Trump so far. Instead, he imagines a scenario in which Trump crosses Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell and shifts toward a more populist economic program, with lots of spending on infrastructure and social welfare. Using that fairly popular agenda, Trump wins re-election. But Trump wouldn’t be some sort of Bloombergian center-left technocrat, Frum says. There would still be plenty of nationalism and social populism mixed in with his economic populism. He’d also continue to defy and disrespect democratic norms and institutions, using the presidency as a platform to bully the opposition and enrich himself. It’s a kinder, gentler, more insidious, more media-savvy form of authoritarianism: “a mix that’s worked well for authoritarians in places like Poland,” as Frum notes.

No, things probably won’t unfold in exactly this way. The point is that it’s a plausible outcome. If the past year and a half has taught us nothing else, it’s that things in American politics often aren’t as certain as people assume, especially when it comes to Trump.

Here, then, is a list of 14 plausible futures for Trump, grouped into a few broad categories. Some of them are mutually exclusive while others can be mixed and matched. And there are undoubtedly many possible futures that I haven’t considered. But I hope that these make for a reasonably representative range of possibilities. If you find yourself feeling a strong urge to rule some of them out, ask yourself whether there’s really enough evidence to do that given that we’re just 1 percent of the way through Trump’s first term.

Group I: Extrapolations from the status quo.This first group of scenarios involve Trump not changing his behavior very much. But the public reaction to him varies, following a steady course in Scenario 1, a downward trajectory in Scenario 2, and an upward trajectory in Scenario 3.

1. Trump keeps on Trumpin’ and the country remains evenly divided. In this scenario, Trump continues to implement his campaign-trail agenda. He still rants on Twitter every morning and picks unnecessary fights, although (perhaps it’s already too late for this?) he mostly avoids major entanglements with foreign leaders that could really get him into trouble. And it … sort of works. The press regularly predicts Trump’s demise, but difficult periods are followed by comparatively successful ones and he benefits from relatively low expectations. At the same time, he doesn’t win over many new converts. Still, Trump’s base of 40 to 45 percent of the country sticks with him. Given Republicans’ geographic advantages in Congress and the Electoral College, that makes for a very competitive 2018 and 2020.

2. Trump gradually (or not-so-gradually) enters a death spiral. Liberals and other Trump adversaries might overrate the likelihood of this scenario. There were many moments during the campaign where the conventional wisdom was that Trump was doomed, only for the narrative to flip once the news cycle turned over. There have also already been a couple of these moments during his first two weeks in the White House: Consider the intense criticism of Trump’s executive order on refugees this weekend, followed by the largely positive reception Trump got on Tuesday for his nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court.

At the same time, we don’t yet know very much about how sustainable Trump’s schtick will be as president, so it would be foolish to dismiss the possibility that he’s in over his head and never really recovers. Trump is fighting a lot of battles at once without much of a support structure around him. Moreover, his problems could be self-reinforcing as issues pile on top of one another and public opinion turns against him, especially if the more coolheaded and competent advisers and Cabinet members flee the White House as Trump begins to falter. In this scenario, Trump’s approval ratings wouldn’t necessarily fall off a cliff — his base would give him a mulligan or two — but they would move slowly and inexorably downward, as happened to George W. Bush during his last two years in office. Although a desperate and deeply unpopular Trump could pose some risks to American institutions, the general idea here is that Trump would become too ineffectual too quickly to cause all that much lasting damage. Impeachment and resignation are plausible endgames in this scenario.

3. Trump keeps rewriting the political rules and gradually becomes more popular. Trump won the presidency despite being fairly unpopular, and he remains fairly unpopular now. Nonetheless, what he’s accomplished is impressive, especially given the long odds that many people (including yours truly) gave Trump at the start. Maybe the guy is pretty good at politics? One can imagine various scenarios where Trump’s default approach to politics turns out to be a winning one over the long run, even if it leads to its fair share of rocky moments. One possible mechanism for this is that by constantly pushing the boundaries of conduct and discourse, Trump shifts the Overton Window (the range of policies and behaviors that are considered politically acceptable) in his direction. In that sense, he’s always playing a home game, since he’s redefined politics on his own terms while others — especially the mainstream media — are struggling to catch up. During the late stages of the Republican nomination race, Trump’s adversaries decided it was easier to join him than to beat him, and voters who were on the fence about him came along. It’s possible that something similar could eventually happen with the general electorate.

Group II: Trump changes direction.These scenarios imagine that Trump shifts his approach, whether because what he was doing before just wasn’t working or because the challenges of the presidency reshape his habits.

4. Trump mellows out, slightly. This is the mildest course change. In this case, after an up-and-down first three to six months, Trump gradually gets better at the job of being president, not necessarily because of a concerted effort to pivot but because he learns through trial and error that he needs to pick his battles. Steve Bannon and other more incendiary advisers lose stature, and Trump’s bonds with Republican leaders in Congress strengthen as he somewhat faithfully carries out their agenda. There are still many profoundly weird moments, but Trump gradually comes to govern more like a conventional Republican. Like most first-term incumbents, he enters 2020 as a slight favorite for re-election.

5. Trump cedes authority. I rarely see this possibility discussed, but it has several historical precedents among presidents who found the job mentally or physically overwhelming. The key aspect is that within a year or two, Trump would have effectively relinquished day-to-day control of the government to Vice President Mike Pence and to his Cabinet, instead focusing on the more ceremonial aspects of the presidency and perhaps exploiting it for personal enrichment. There are several variations on this scenario, which range from Trump being surprisingly popular as a sort of celebrity-in-chief to Trump largely withdrawing from the public spotlight.

6. Trump successfully pivots to the populist center (but with plenty of authoritarianism too). This is Frum’s scenario. To recap, it involves Trump becoming more of a true populist, remaining hard-line on immigration and trade but calling for significant infrastructure and social welfare spending. His new direction earns plaudits from the media, which is eager to tell a “pivot” story, and is genuinely popular with independents and Rust Belt Democrats. At the same time, Trump continues to erode the rule of law by using strong-arm tactics with the media, the judiciary and private business, and he collaborates with Republicans to restrict voting rights. Trump’s presidency is fairly successful as far as it goes, but he moves the country in the direction of being an illiberal democracy.

7. Trump flails around aimlessly after an unsuccessful attempt to pivot. In this scenario, Trump is like George Steinbrenner running the 1980s New York Yankees, firing his managers and changing course all the time without ever really getting anywhere. Instead, he churns through advisers and alienates allies faster than he makes new ones. In one version of the scenario, Trump attempts a Frum-ian pivot to the center but it fails — Congressional Republicans don’t go along with with the program, and it costs him credibility with his base more quickly than it wins him new converts. By early 2019, there are impeachment proceedings against Trump, and several Republicans are considering challenging him for the 2020 nomination. Trump winds up being something of a lame duck despite being in his first term, drawing comparisons to Jimmy Carter.