Nate Silver's Blog, page 112

January 23, 2017

The Invisible Undecided Voter

This is the third article in a series that reviews news coverage of the 2016 general election, explores how Donald Trump won and why his chances were underrated by the most of the American media.

In 2012, President Obama’s advantage over Mitt Romney, although often paper-thin in national polls, was stronger than it appeared for two big reasons. One was that Obama, in stark contrast to Hillary Clinton, was outperforming his national polls in swing states, largely as a result of his popularity in the Midwest. The other is that 2012 featured remarkably few undecided voters: Only about 4 percent of voters went into Election Day not already committed to Obama or Romney. That reduced the chance of a potential last-minute swing. Even if most of the undecideds turned out for Romney, it probably wouldn’t have been enough to vault him past Obama in the swing states.

Just the opposite was true in 2016, and Clinton’s lead was considerably more fragile than it appeared from national polls. Not only was she underperforming in the Electoral College because of the way her demographic coalition was configured (see the first article in this series for more about that) but a much larger number of voters — about 13 percent on Election Day and as many as 20 percent at earlier stages of the campaign — were either undecided or said they planned to vote for third-party candidates Gary Johnson and Jill Stein. Those undecided voters made Clinton’s lead much less safe and they broke strongly toward Donald Trump at the end of the race. Trump won voters who decided in the last week of the campaign by a 59-30 margin in Wisconsin, 55-38 in Florida, 54-37 in Pennsylvania and 50-39 in Michigan, according to exit polls, which was enough to flip the outcome of those four states and their 75 combined electoral votes.

The late shift toward Trump, like other periods of polling instability throughout the campaign, was consistent with a long-term pattern. Historically, the more undecided and third-party voters there are, the more volatile and less accurate the polling has tended to be. The relationship ought to be fairly intuitive: There’s not much a pollster can do when a voter hasn’t yet made up her mind. In 1980, for instance, final polls showed Ronald Reagan leading Jimmy Carter roughly 43-40, with 17 percent of voters undecided or saying they planned to vote for independent John Anderson. Reagan wound up winning in a landslide, 51-41, making for a seemingly massive polling error. But Carter technically didn’t underperform his polls: it’s just that Reagan hugely outperformed his as undecideds and Anderson voters broke his way. A milder example came in 2000, when a relatively high number of voters said they were undecided or planned to vote for Ralph Nader, presaging an upset win in the popular vote by Al Gore (George W. Bush had led by 3 to 4 percentage points in the final national polls). By contrast, the 2004 and 2008 cycles had very few undecided voters and highly accurate polling.

COMBINED UNDECIDED + THIRD PARTY VOTECYCLEWITH 100 DAYS TO GOON ELECTION DAY19729.3%–8.1%–197610.0–8.7–198025.5–17.3–19847.4–4.7–198810.8–5.7–199219.1–22.1–199619.7–13.3–200017.8–8.9–20046.4–3.4–200813.1–3.6–20127.6–4.3–201618.5–12.5–2016 featured far more undecided voters than recent past elections2016 estimates are based on FiveThirtyEight “polls-only” national average. Estimates for years prior to 2016 are based on retroactively running the FiveThirtyEight model, except the estimates in 1972 and 1976 with 100 days to go, which are based on a simple average of national polls in July 1972 and July 1976, respectively. (There would not enough polls in these years to properly run the FiveThirtyEight model 100 days in advance.)

FiveThirtyEight’s model accounted for the high number of undecideds, which is part of the reason it gave Trump better odds than other forecasts. I’m somewhat perplexed as to why these voters didn’t draw more attention from other modelers or reporters, however, since they were often key to understanding the progression of the campaign. With a large fraction of voters not firmly committed to either candidate — no doubt in part because of the historic unpopularity of both Clinton and Trump — it didn’t take much to move them from one candidate to the other, and so news events had more impact on the polls in 2016 than they did in 2012.

To the extent reporters considered the high number of undecideds, it was often in focusing on how Trump’s share of the vote was low, without noticing that the same was also true for Clinton. For instance, on Aug. 12, The New York Times wrote that Trump had “been waiting for months for a poll in which he cracks 50 percent of the vote against Hillary Clinton in any of his top battleground states” and suggested he had a ceiling on his support:

For a candidate who once seemed like an electoral phenomenon, with an unshakable following and a celebrity appeal that crossed party lines, Mr. Trump now faces the possibility that his missteps have erected a ceiling over his support among some demographic groups and in several swing states. He has been stuck under 45 percent of the vote in Ohio and Pennsylvania for weeks, polls show, while Mrs. Clinton has gained support.

The flaw in the analysis is that by this logic, Clinton also had a ceiling. Although this article was written at one of the high points of the campaign for Clinton in the midst of her convention bounce, she nonetheless had only 44 to 45 percent of the vote in national polls. A significant fraction of voters disliked both candidates, and Clinton never quite drew enough voters into her column to make her lead truly safe, as it might have been if she’d reached closer to 50 percent of the vote.

Was it predictable that those late-deciding voters would break toward Trump? I tend to think mostly not and that the behavior of the late-deciders was instead mainly attributable to an unfavorable news environment for Clinton in the shadow of the James B. Comey letter to Congress and the Wikileaks dumps. But you could argue the point. A once-popular idea called the “incumbent rule” held that undecideds tended to break toward the challenger (as they did toward Reagan in 1980). There are some big flaws with this idea as applied to 2016: It hadn’t hadn’t held up well in recent years (late-deciding voters broke slightly to President Obama in 2012, for instance) and although Clinton was running as a de facto successor to Obama, she wasn’t technically an incumbent.

Still, if the incumbent rule was iffy, so was the idea that Trump had a ceiling imposed by demographics. All it took was for him to win two-thirds of white voters without college degrees to overcome huge problems with the rest of the electorate. (The Electoral College also helped Trump, of course, allowing him to be elected with only 46 percent of the national vote.)

The undecideds were a warning sign that Clinton hadn’t sealed the deal with quite a wide enough coalition of voters, conversely — especially in the Midwest where undecideds were plentiful. In the states that were the biggest upsets relative to the polls — Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — Clinton met or slightly exceeded her share of the vote in polls, but Trump beat his by more.

It Wasn’t Clinton’s Election To Lose

This is the second article in a series that reviews news coverage of the 2016 general election, explores how Donald Trump won and why his chances were underrated by the most of the American media.

If the “emerging Democratic majority” was one pillar of the flawed argument that Hillary Clinton had an Electoral College advantage over Donald Trump, the other was the “blue wall,” the claim that Democrats began with a base of 242 electoral votes because they’d won them in each election since 1992. Here’s a version of the argument as it appeared in The New York Times on July 30, for example:

For now, though, Mr. Trump is grappling with a magnified version of the dilemma that threatens to stymie Republicans every four years. Democrats have won a consistent set of 18 states in every presidential election since 1992, giving them a base of 242 Electoral College votes even before counting some of the biggest swing states. As a result, the last two Republican nominees, Mitt Romney and John McCain, would have needed to capture nearly all the contested states on the map in order to win.

It turned out that Clinton lost three “blue wall” states — Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin — along with the 2nd Congressional District of Maine. Throughout the campaign, the Times and most other news outlets had downplayed Trump’s prospects in these states, which were enough to win him the election.

What was wrong with the “blue wall” idea? You can read our longer critique here, but the gist of it is that looking at a state’s long-term voting history told you almost nothing about how it was likely to behave the next time around. California and Vermont had once been reliably red states (they had voted Republican in each election from 1968 to 1988) until they suddenly weren’t. In 1992, the first year of the “blue wall,” Arkansas and West Virginia were more Democratic than Connecticut. A state’s short-term voting history (how it voted in 2012 and 2008) might tell you something more, by contrast. But that information needed to be interpreted carefully because states rise and fall with the national tide.

An alternative to the “blue wall” and the “emerging Democratic majority” was to look at the underlying, macro-level conditions of the race, or what we sometimes refer to as the “fundamentals.” Political scientists and other empiricists disagree on exactly how to do this, and the precision of these methods can be overestimated. But there’s broad agreement on a couple of propositions:

First, there are few if any permanent majorities. A newly elected party (for instance, Barack Obama’s Democrats before the 2012 election) often wins a second presidential term. Beyond that, it’s not much of an advantage to be the incumbent party, and it may be at a slight disadvantage when a party tries to win more than two terms in a row.Second, the economy matters a lot to voters, and a better economy helps the incumbent party, other factors held equal.By this rubric, the 2008 and 2012 elections were likely to be strong years for Democrats. In 2008, Obama was facing John McCain after Republicans had held the White House for two terms and overseen a financial collapse. In 2012, Obama was a first-term incumbent running for re-election and the economy was just good enough to get him over the finish line.

But Clinton faced more headwinds in 2016, trying to win a third consecutive term for her party amid a mediocre economy. Against a “generic” Republican such as John Kasich or Marco Rubio, she might have been in a toss-up race or even a slight underdog, in fact. So she was counting on good economic news — or for Trump to underperform a “generic” Republican because of his unique flaws as a candidate.

The “fundamentals” approach also has its limitations. There are lots of ways to measure economic conditions, and they don’t always agree with one another. Furthermore, fundamentals models don’t have any notion of what makes for a good candidate, which sometimes leads to the mistaken view that candidates and campaigns don’t matter at all.

But instead of being presented with appropriate qualifications, this perspective was almost completely lacking in coverage of the 2016 campaign. (And it wasn’t because reporters were unfamiliar with it: In 2012, there was lots of attention to how the economy was affecting the race, with monthly jobs reports being as hotly anticipated as new poll releases from Florida or Ohio.) Coverage rarely mentioned the parallels between Clinton and Al Gore, for instance, who had failed to win a third consecutive term for Democrats in 2000 under similar conditions to the ones Clinton faced.

Instead, 2016 was generally treated as Clinton’s race to lose when that conclusion didn’t necessarily follow from the empirical research on presidential campaigns. A better perspective was that Clinton was leading in the polls despite somewhat challenging conditions for Democrats, no doubt in part because of Trump’s flaws as a candidate. However, that made her vulnerable if the candidate-quality gap closed — whether because of her own problems as a candidate or because Trump’s performance improved — in which case partisanship would kick in and she’d be headed for a barnburner of a finish.

Incidentally, Clinton slightly outperformed the “fundamentals” according to most of the political science models, which usually forecast the popular vote rather than the Electoral College. For instance, the economic index included in FiveThirtyEight’s “polls-plus” model implied that Trump would win the popular vote by about 1 percentage point. Instead, Clinton won it by roughly 2 percentage points. That’s not a huge difference, but it’s something to consider before assuming that Clinton must have been an exceptionally flawed candidate.

It’s also possible, of course, that Clinton and Trump were both “bad” candidates but that their flaws mostly cancelled one another out. This idea would seem to be supported by their record-low favorability ratings, for example. One bit of pushback to this theory: Politicians are an unpopular lot nowadays, and most of the other men and women who ran for president in 2016 wound up with bad favorability ratings too. So Trump and Clinton’s unpopularity may have been partly an artifact of the partisan political climate. Either way, it’s rarely easy to win a presidential election, and Clinton was trying to win hers under more challenging conditions than what Democrats faced in 2008 and 2012.

The Electoral College Blind Spot

This is the first article in a series that reviews news coverage of the 2016 general election, explores how Donald Trump won and why his chances were underrated by the most of the American media.

Donald Trump’s victory in last November’s election victory came despite the fact that he lost the popular vote by 2.1 percentage points, making for the widest discrepancy between the popular vote and the Electoral College since 1876. So one measure of the quality of horse-race analysis is in how seriously it entertained the possibility of such a split in Trump’s favor. This is one point on which the data geeks generally came closer to getting the right answer. FiveThirtyEight’s statistical model, for example, saw the Electoral College as a significant advantage for Trump, and projected that he’d be about even money to win the Electoral College even if he lost the popular vote by 1 to 2 percentage points. Overall, it assigned a 10.5 percent chance to Trump’s winning the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, but less than a 1 percent chance of Hillary Clinton’s doing the same.

By contrast, much of the conventional reporting during the campaign wrongly presumed that the Electoral College would be an advantage for Clinton. For instance, on July 30 — at a time just after the conventions when national polls showed Clinton and Trump almost tied — The New York Times wrote of Trump’s “daunting electoral map” and narrow path to 270 electoral votes:

Even as Mr. Trump has ticked up in national polls in recent weeks, senior Republicans say his path to the 270 Electoral College votes needed for election has remained narrow — and may have grown even more precarious. It now looks exceedingly difficult for him to assemble even the barest Electoral College majority without beating Hillary Clinton in a trifecta of the biggest swing states: Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The article would go on to cite premises that reflected the idea of the “emerging Democratic majority,” the phrase coming from the title of a 2002 book by John Judis and Ruy Teixeira, which argued that the country’s changing demographics — particularly, the growing number of minority and college-educated voters — worked in Democrats’ favor. For instance, the Times implied that Trump’s problems among “Hispanic voters and suburban moderates” constituted an especially big liability in the Electoral College.

But the “emerging Democratic majority” had a lot of flaws, some of which had been pointed out by data-savvy journalists for years. (See for example Real ClearPolitics’s Sean Trende, The Upshot’s Nate Cohn, and FiveThirtyEight contributor David Wasserman.) One basic problem with the theory is that while white voters without college degrees might have been declining as a share of the electorate, they still represented a hugely influential group and significantly outnumbered racial minorities in the electorate. According to Wasserman’s estimates, 42 percent of voters are whites without college degrees. By comparison, 27 percent of voters are nonwhite. If white noncollege voters were to start voting Republican by the same margins that minorities voted for Democrats, Democrats were potentially in a lot of trouble, even if they also made gains among college-educated whites.

Furthermore, whites without college degrees are overrepresented in swing states as compared to the country as a whole. Sure, there were some exceptions, such as Virginia. But in the average swing state — weighted by its likelihood of being the tipping-point state — whites without college degrees make up an average of 45.3 percent of the electorate, higher than their 41.6 percent share nationwide. That’s a big part of why Clinton won the popular vote while losing the Electoral College.

STATETIPPING-POINT CHANCEWHITE NON-COLLEGE SHAREFlorida17.6%40.1%–Pennsylvania12.349.8–Michigan11.752.5–North Carolina11.240.4–Virginia6.036.7–Colorado6.041.6–Ohio5.253.3–Wisconsin4.857.2–Minnesota3.853.7–Nevada3.741.9–Arizona2.841.6–New Mexico2.827.5–New Hampshire2.356.5–Georgia2.334.2–Iowa1.362.0–Weighted avg. of tipping-point states45.3–United States41.6–Swing states had an above average share of white noncollege votersThe weighted average includes states where the tipping-point chance was below Iowa’s 1.3 percent.

The “emerging Democratic majority” also hadn’t held up that well empirically. Since the book was written, Democrats had good election cycles in 2006, 2008 and 2012 but bad ones in 2004, 2010 and 2014 — and had decent results in federal elections but had fared miserably in elections for governor and state legislatures.

Why then, did the idea have such currency? One reason may be that it was seductive to liberal cosmopolitans, a category that includes most journalists at the Times and at other news outlets (including FiveThirtyEight). If you live in a big city and work in an industry dominated by college-educated professionals, you might intuitively overestimate the education level of the electorate and how rapidly it was diversifying.

There’s a more banal possibility also: The failure to see Clinton’s vulnerabilities in the Electoral College reflected a lack of attention to detail. It was easy to make a superficial case along the following lines: Democrats had won two presidential elections in a row, the minority population was growing, and states such as Arizona were becoming more competitive. Therefore, Advantage Clinton in the Electoral College. By contrast, the flaws in the argument required a pencil and paper — or a spreadsheet — to work out. If you weren’t being careful, you might have missed that the Midwestern states moving away from Clinton had a lot more electoral votes than the ones like Arizona that were moving toward her, or that polls showed her substantially underperforming Obama in middle-class states such as Pennsylvania and Michigan. Another important detail — as discovered by Cohn — is that exit polls had probably overstated the diversity and education levels of the electorate.

Or it may be that these are really two sides of the same coin: Because journalists were predisposed toward the assumption that the country was too diverse to elect Trump, they didn’t probe it for flaws as much as they might have otherwise. The “emerging Democratic majority” was reasonable-sounding argument, but it didn’t hold up well to scrutiny and it didn’t get enough of it.

January 19, 2017

The Real Story Of 2016

On Friday at noon, a Category 5 political cyclone that few journalists saw coming will deposit Donald Trump atop the Capitol Building, where he’ll be sworn in as the 45th president of the United States. It’s tempting to use the inauguration as an excuse to finally close the chapter on the 2016 election and instead turn the page to the four years ahead. But for journalists, given the exceptional challenges that Trump poses to the press and the extraordinary moment he represents in American history, it’s also imperative to learn from our experiences in covering Trump to date.

As editor-in-chief of FiveThirtyEight, which takes a different and more data-driven perspective than many news organizations, I don’t claim to speak to every question about how to cover Trump. And I don’t expect many of the answers to be obvious or easy. But in the part of the story that I know best, horse-race coverage, the results of the learning process have been discouraging so far.

While data geeks and traditional journalists each made their share of mistakes when assessing Trump’s chances during the campaign, their behavior since the election has been different. After Trump’s victory, the various academics and journalists who’d built models to estimate the election odds engaged in detailed self-assessments of how their forecasts had performed. Not all of these assessments were mea culpas — ours emphatically wasn’t (more about that in a moment) — but they at least grappled with the reality of what the models had said.

By contrast, some traditional reporters and editors have built a revisionist history about how they covered Trump and why he won. Perhaps the biggest myth is when traditional journalists claim they weren’t making predictions about the outcome. That may still largely be true for local reporters, but at the major national news outlets, campaign correspondents rarely stick to just-the-facts reporting (“Hillary Clinton held a rally in Des Moines today”). Instead, it’s increasingly common for articles about the campaign to contain a mix of analysis and reporting and to make plenty of explicit and implicit predictions. (Usually, these take the form of authoritatively worded analytical claims about the race, such as declaring which states are in play in the Electoral College.) Furthermore, editors and reporters make judgments about the horse race in order to decide which stories to devote resources to and how to frame them for their readers: Go back and read their coverage and it’s clear that The Washington Post was prepared for the possibility of a Trump victory in a way that The New York Times wasn’t, for instance.

If almost everyone got the first draft of history wrong in 2016, perhaps there’s still time to get the second draft right.Another myth is that Trump’s victory represented some sort of catastrophic failure for the polls. Trump outperformed his national polls by only 1 to 2 percentage points in losing the popular vote to Clinton, making them slightly closer to the mark than they were in 2012. Meanwhile, he beat his polls by only 2 to 3 percentage points in the average swing state. Certainly, there were individual pollsters that had some explaining to do, especially in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, where Trump beat his polls by a larger amount. But the result was not some sort of massive outlier; on the contrary, the polls were pretty much as accurate as they’d been, on average, since 1968.

Why, then, had so many people who covered the campaign been so confident of Clinton’s chances? This is the question I’ve spent the past two to three months thinking about. It turns out to have some complicated answers, which is why it’s taken some time to put this article together (and this is actually the introduction to a long series of articles on this question that we’ll publish over the next few weeks). But the answers are potentially a lot more instructive for how to cover Trump’s White House and future elections than the ones you’d get by simply blaming the polls for the failure to foresee the outcome. They also suggest there are real shortcomings in how American politics are covered, including pervasive groupthink among media elites, an unhealthy obsession with the insider’s view of politics, a lack of analytical rigor, a failure to appreciate uncertainty, a sluggishness to self-correct when new evidence contradicts pre-existing beliefs, and a narrow viewpoint that lacks perspective from the longer arc of American history. Call me a curmudgeon, but I think we journalists ought to spend a few more moments thinking about these things before we endorse the cutely contrarian idea that Trump’s presidency might somehow be a good thing for the media.

To be clear, if the polls themselves have gotten too much blame, then misinterpretation and misreporting of the polls is a major part of the story. Throughout the campaign, the polls had hallmarks of high uncertainty, indicating a volatile election with large numbers of undecided voters. And at several key moments they’d also shown a close race. In the week leading up to Election Day, Clinton was only barely ahead in the states she’d need to secure 270 electoral votes. Traditional journalists, as I’ll argue in this series of articles, mostly interpreted the polls as indicating extreme confidence in Clinton’s chances, however.

So did many of the statistical models of the campaign, of course. While FiveThirtyEight’s final “polls-only” forecast gave Trump a comparatively generous 3-in-10 chance (29 percent) of winning the Electoral College, it was somewhat outside the consensus, with some other forecasts showing Trump with less than a 1 in 100 shot. Those are radically different forecasts: one model put Trump’s chances about 30 times higher than another, even though they were using basically the same data. Instead of serving as an indication of the challenges of poll interpretation, however, “the models” were often lumped together because they all showed Clinton favored, and they probably reinforced traditional reporters’ confidence in Clinton’s prospects.

But the overconfidence in Clinton’s chances wasn’t just because of the polls. National journalists usually interpreted conflicting and contradictory information as confirming their prior belief that Clinton would win. The most obvious error, given that Clinton won the popular vote by more than 2.8 million votes, is that they frequently mistook Clinton’s weakness in the Electoral College for being a strength. They also focused extensively on Clinton’s potential gains with Hispanic voters, but less on indications of a decline in African-American turnout. At moments when the polls showed the race tightening, meanwhile, reporters frequently focused on other factors, such as early voting and Democrats’ supposedly superior turnout operation, as reasons that Clinton was all but assured of victory.

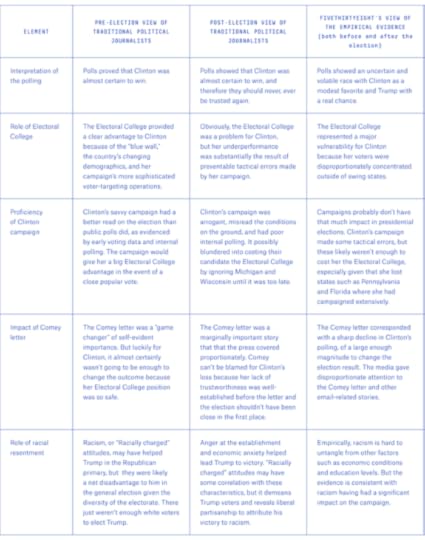

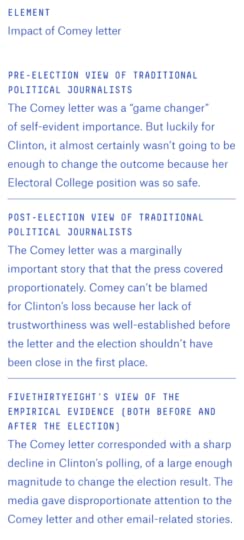

Post-election coverage has also sometimes misled readers about how stories were reported upon while the campaign was underway. The table below contains some important examples of this. Election post-mortems by major news organizations have tended to skirt past how much importance they attached to FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress on Oct. 28, for instance, and how much the polls shifted toward Trump in the immediate aftermath of Comey’s letter.

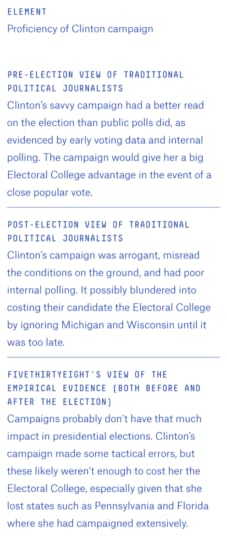

In other cases, the conventional wisdom has flip-flopped without journalists pausing to consider why they got the story wrong in the first place. For instance, it’s now become fashionable to bash Clinton for having failed to devote enough resources to Michigan and Wisconsin. Never mind, for a moment, that these states wouldn’t have been enough to change the overall result. (If Clinton had won Michigan and Wisconsin, she’d still have only 258 electoral votes. To beat Trump, she’d have also needed a state such as Pennsylvania or Florida where she campaigned extensively.) The criticism is ironic given that many stories during the campaign heralded the Clinton campaign’s savviness, while skewering Trump for having campaigned in “solidly blue” states such as Michigan and Wisconsin. It’s fair to question Clinton’s approach, but it’s also important to ask whether journalists put too much stock in the Clinton campaign’s view of the race.

What exactly, then, is the “right” story for how Trump won the election? I obviously have a detailed perspective on this — but in a macroscopic view, the following elements seem essential:

First, the background conditions were pretty good for Trump. Clinton was trying to win a third consecutive term for her party, replacing a fairly popular predecessor in President Obama, but she was doing that amid a mediocre economy and at a time of high partisanship. Various “fundamentals” models put together by political scientists and economists considered a matchup between a “generic” Republican and a “generic” Democrat (say, between Marco Rubio and Joe Biden) to be roughly a toss-up under these circumstances, or perhaps to slightly favor the GOP. While these models have significant limitations, they argue against the widespread presumption that the election was Clinton’s to lose.Second, demographics gave Trump a big advantage in the Electoral College. Clinton won the popular vote by 2.1 percentage points, similar to George W. Bush’s margin of victory over John Kerry in 2004, after which Bush claimed to have earned a mandate. But she lost in the biggest popular vote-versus-Electoral College discrepancy since 1876. Although Trump has protested otherwise, this discrepancy does not appear to have been mainly the result of tactical choices made by the campaigns. Instead it reflected demographics: White voters without college degrees, by far Trump’s strongest demographic group, were disproportionately concentrated in swing states, while Clinton’s coalition of minorities and college-educated whites (but with declining turnout among black voters) produced huge gains for her in states such as California and Texas without winning her any additional electoral votes.Third, voter preferences varied substantially based on news events, and the news cycle ended on a downturn for Clinton. As compared with recent presidential elections, there were a much higher number of undecided and third-party voters in 2016, probably because of the record-setting unpopularity of both Clinton and Trump. As a result, public opinion was sensitive to news coverage and events such as debates, with Clinton holding a national polling lead of as much as 6 to 8 percentage points over Trump in most of June, August and October, but Trump within striking distance in most of July, September and (crucially) November. Late-deciding voters broke strongly toward Trump in the final two weeks of the campaign, amid a news cycle dominated by discussion of the Comey letter and the Wikileaks hack of Democratic emails.This is an uncomfortable story for the mainstream American press. It mostly contradicts the way they covered the election while it was underway (when demographics were often assumed to provide Clinton with an Electoral College advantage, for instance). It puts a fair amount of emphasis on news events such as the Comey letter, which leads to questions about how those stories were covered. It’s much easier to blame the polls for the failure to foresee the outcome, or the Clinton campaign for blowing a sure thing. But we think the evidence lines up with our version of events. And if almost everyone got the first draft of history wrong in 2016, perhaps there’s still time to get the second draft right.

I want to lay down a few ground rules for how this series of articles will proceed — but first, a few words about FiveThirtyEight’s coverage of Trump. My view is that we had lots of problems, but that we got most of them out of the way good and early by botching our assessment of Trump’s chances of winning the Republican primary. Among our mistakes: That forecast wasn’t based on a statistical model, it relied too heavily on a single theory of the nomination campaign (“The Party Decides”), and it didn’t adjust quickly enough when the evidence didn’t fit our preconceptions about the race. Moreover, we “leaned into” this view in the tone and emphasis of our articles, which often scolded the media for overrating Trump’s chances. While it’s challenging to judge a probabilistic forecast on the basis of a single outcome, we have no doubt that we got the Republican primary “wrong.”

Something like the opposite was true in the general election, in our view. While our model almost never had Trump as an outright favorite, it gave him a much better chance than other statistical models, some of which had him with as little as a 1 percent chance of victory. Independent evaluations also judged FiveThirtyEight’s forecast to be the most accurate (or perhaps better put, the least inaccurate) of the models. The tone and emphasis of our coverage drew attention to the uncertainty in the outcome and to factors such as Clinton’s weak position in the Electoral College, since we felt these were misreported and neglected subjects. We even got into a couple of very public screaming matches with people who we thought were unjustly overconfident in Trump’s chances.

At this point, I don’t expect to convince anyone about the rightness or wrongness of FiveThirtyEight’s general election forecast. To some of you, a forecast that showed Trump with about a 30 percent chance of winning when the consensus view was that his chances were around 15 percent will self-evidently seem smart. To others, it will seem foolish. But for better or worse, what we’re saying here isn’t just hindsight bias. If you go back and check our coverage, you’ll see that most of these points are things that FiveThirtyEight (and sometimes also other data-friendly news sites) raised throughout the campaign.

With that in mind, here’s ground rule No. 1: These articles will focus on the general election. That’s because we spent a lot of time last spring and summer reflecting on the nomination campaign. You can find our self-critique of our primary coverage here. For other detailed reflections, I’d recommend my colleague Clare Malone’s piece on what Trump’s win in the primary told us about the Republican Party, and my article on how the media covered Trump during the nomination process.

Ground rule No. 2: These articles will mostly critique how conventional horse-race journalism assessed the election, although with several exceptions. The focus on conventional journalism in this article is not meant to imply that data journalists got everything right, however. There’s obviously a lot to criticize in how certain statistical models were designed, for instance. But we’ve already covered these modeling issues at length both before and after the election, so I won’t dwell on them quite as much here. As a quick review, however, the main reasons that some of the models underestimated Trump’s chances are as follows:

Most of the models underestimated the extent to which polling errors were correlated from state to state. If Clinton were going to underperform her polls in Pennsylvania, for instance, she was also likely to do so in demographically similar states such as Wisconsin and Michigan.Several of the models were too slow to recognize meaningful shifts in the polls, such as the one that occurred after the Comey letter on Oct. 28.Most of the models didn’t account for the additional uncertainty added by the large number of undecided and third-party voters, a factor that allowed Trump to catch up to and surpass Clinton in states such as Michigan.Some of the models were based only on the past few elections, ignoring earlier years, such as 1980, when the polling had been way off.Put a pin in these points because they’ll come up again. Interestingly enough, the analytical errors made by reporters covering the campaign often mirrored those made by the modelers. I’d also argue that data journalists are increasingly making some of the same non-analytical errors as traditional journalists, such as using social media in a way that tends to suppress reasonable dissenting opinion.

One final ground rule: The corpus for this critique will be The New York Times. Specifically, it will be stories published by the Times’s political desk (as opposed to its by investigations team, in its editorial pages or by its data-oriented subsite, The Upshot). This is not an arbitrary choice. The Times, which hosted FiveThirtyEight from 2010 to 2013, is one of the two most influential outlets for American political news, along with The Washington Post. But also, the Times is a good place to look for where coverage went wrong. Few major news organizations conveyed more confidence in Clinton’s chances or built more of their coverage around the presumption that she’d become the 45th president. (At one point, the Times actually referred to Clinton’s “administration-in-waiting”). Articles commissioned by the Times’s political desk regularly asserted that the Electoral College was a strength for Clinton, when in fact it was a weakness. Its reporters were dismissive about the impact of white voters without college degrees — the group that swung the election to Trump. And the Times, like the Clinton campaign, largely ignored Michigan and Wisconsin.

As you read these, keep in mind this is mostly intended as a critique of 2016 coverage in general, using The New York Times as an example, as opposed to a critique of the Times in particular. Most of these mistakes were replicated by other mainstream news organizations, and also often by empirically minded journalists and model-builders. At the same time, a relatively small group of journalists and news organizations, including the Times, has a disproportionate amount of influence on how political events are understood by large segments of the American public. (Media consolidation may itself be a part of the reason that Trump’s chances were underestimated, insofar as it contributed to groupthink about his chances.) I think it’s important to single out examples of better and worse coverage, as opposed to presuming that news organizations didn’t have any choice in how they portrayed the race, or bashing “the media” at large. Obviously, I’m mostly taking a critical focus here, but in the footnotes you can find a list of examples of outstanding horse-race stories — articles that sagely used reporting and analysis to scrutinize the conventional wisdom that Clinton was the inevitable winner.

So here’s how we’ll proceed. I’ve clipped a number of representative snippets from the Times’s coverage of the campaign from the conventions onward. Each one will form the basis for a short article that reveals what I view as a significant error in how 2016 was covered. We’re currently planning on about a dozen of these articles — the idea is to be comprehensive — grouped into two broad categories. The first half will cover what I view as technical errors, while the second half will fall under the heading of journalistic errors and cognitive biases. It’s a somewhat fuzzy distinction, but important for what lessons might be drawn from them. The technical errors ought to be easier to fix, but they have narrower applications. The cognitive biases reflect more deep-seated problems and have more implications for how Trump’s presidency will be covered; they’re also the root cause of some of the technical errors. But they won’t be easy to correct unless journalists’ incentives or the culture of political journalism change. We’ll release these a couple of articles at a time over the course of the next few weeks, adding links as we go along. Then I’ll have some concluding thoughts. It’s going to be a lot of 2016, at the same time we’re also covering what’s sure to be a tumultuous 2017. But the election is too important a story for journalists to just shrug and move on from — or worse, to perpetuate myths that don’t reflect the reality of how history unfolded.

January 17, 2017

Can You Trust Trump’s Approval Rating Polls?

For perhaps the first time since last November’s election, polls are making headlines again. Surveys from CNN, Gallup, ABC News and The Washington Post, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal and Quinnipiac University all have Donald Trump with net-negative numbers on handling his presidential transition and duties as president-elect. On average between the five surveys, 41 percent of Americans approve of Trump’s transition performance while 52 percent disapprove.

POLLSTERAPPROVEDISAPPROVECNN40%52%Gallup4451ABC News / Washington Post4054Quinnipiac University3751NBC News / Wall Street Journal4452Average4152January polls give Trump poor marks for transitionWhile those numbers wouldn’t be all that out of line for a sitting president’s job approval rating — almost every recent commander-in-chief has endured a slump or two — they’re unusual for a president-elect. Newly elected presidents typically enjoy high approval ratings as they transition into office. Even George W. Bush, who won the 2000 election only after a contentious recount and despite losing the popular vote, had about two-thirds of Americans approving of his transition as he prepared to take the oath of office.

And so Trump — in what’s almost certainly a sign of things to come — has pushed back against the approval-ratings polls on Twitter. Let’s let @realDonaldTrump take the dais:

The same people who did the phony election polls, and were so wrong, are now doing approval rating polls. They are rigged just like before.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 17, 2017

One might be inclined to make a variety of rebuttals here. For instance, these particular pollsters aren’t especially good targets for Trump’s ire. Of the five pollsters, only ABC News and NBC News issued late national polls, and they were both fairly close to the mark, projecting Hillary Clinton to win the popular vote by 4 percentage points (in fact, Clinton won the popular vote by 2.1 points). Quinnipiac did issue late polls that showed Clinton narrowly ahead in Florida and North Carolina, although Trump’s narrow win in Florida was comfortably within the poll’s margin of error.

Also, these approval ratings polls are measuring opinions among all adults, instead of registered or likely voters. In theory, polls that sample all adults are less error-prone, since a pollster doesn’t have to worry about projecting who will turn out to vote.

But all of that may be getting too much into the weeds. There’s no doubt that polls took a trust hit during the campaign and that Trump is going to exploit it.

Here’s the thing. The loss of trust mostly isn’t the pollsters’ fault. It’s the media’s fault. Oh, yes, I’m going there. The loss of trust in polls was enabled, in large part, by reporting and analysis that incorrectly portrayed the polls as showing an almost-certain Clinton win when in fact they showed a close and highly uncertain Electoral College race, especially after FBI Director James B. Comey’s letter to Congress on Oct. 28.

As my colleague Harry Enten put it a few days before the election, Trump was only a normal-size polling error away from winning. Clinton would win if the polls were spot on — and she’d win in a borderline landslide in the event of an error in her favor. But the third possibility — if the polls underestimated Trump, even slightly — would probably be enough for Trump to win the Electoral College. (That’s why FiveThirtyEight’s forecast during the final week of the campaign showed Trump with roughly a 1-in-3 chance of winning the Electoral College, dipping slightly to 29 percent on Election Day itself.)

That third possibility is pretty much exactly what happened. Trump beat the final FiveThirtyEight national polling average by only 1.8 percentage points. Meanwhile, he beat the final FiveThirtyEight polling average in the average swing state — weighted by its likelihood of being the tipping-point state — by 2.7 percentage points. (The miss was larger than that in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, but Clinton met or slightly exceeded her polls in several other swing states.) This was nothing at all out of the ordinary. The polls were about as accurate as they’d been, on average, in presidential elections since 1968. They were somewhat more accurate than they’d been in the most recent federal election, the 2014 midterms. But they were enough to tip the election to Trump because Clinton had been in a precarious position to begin with.

Yep, this is opening up a can of worms. And get ready, because we’re going to be uncracking a giant, industrial-size vat of worms later this week, with a series of articles that ask why the conventional wisdom was so sure Clinton would win when (in our view, anyway) that conclusion wasn’t justified based on the polls. The answers turn out to be pretty interesting — and complicated — so I’ll save the detail for later.

In the meantime, with polls in the news again, I’d urge my journalistic colleagues to do a better job of reporting on uncertainty when they report on polling data. Not only do polls have a margin of sampling error — for instance, the margin of sampling error on CNN’s poll of 1,000 adults is plus or minus 3 percentage points — but they also have other types of errors, such as nonresponse bias. The people who respond to polls — often under 10 percent of the population contacted — may not be representative of the population as a whole, and that creates a lot of challenges.

These types of errors are harder to quantify, but as an empirical matter they probably work out to an additional margin of error of 2.5 to 3 percentage points for national polls. Call this figure the margin of methodological error (this is my term, not one in common use). The error can be a lot higher under some circumstances, such as when measuring voter preferences during a low-turnout primary, or for subsamples of hard-to-reach populations. But since our focus is on national approval ratings polls, we’ll ignore those complications for now.

So then, to calculate the overall error in a poll — what I’ll call the true margin of error — you add the margin of sampling error and the margin of methodological error together, right? No, not quite. Instead, you need a sum of squares formula. To save you some math, here are a few useful benchmarks:

For a high-quality, 1,000-person national poll, a good estimate of the true margin of error is about plus or minus 4 percentage points.For a national polling average, meanwhile, the true margin of error is about plus or minus 3 percentage points. It’s true that polling averages can greatly reduce sampling error, by aggregating thousands of interviews together. But polling averages don’t necessarily eliminate methodological error. When the polls are wrong, they tend to miss in the same direction.There’s one other critical distinction that people often miss. The margin of error, as traditionally described, applies only to one candidate’s vote share (“Clinton has 47 percent of the vote”) or one side of a yes/no question (“41 percent of voters approve of Trump’s performance”). The margin of error for the difference between two candidates (“Clinton leads Trump by 5 percentage points”) — or a candidate’s net approval rating (“Trump has a negative-10 approval rating”) — is roughly twice as high:

That means for a high-quality, 1,000-person national poll, the true margin of error for the margin between candidates — or a candidate’s net approval rating — is about 8 percentage points.And for a national polling average, the true margin of error for the margin between candidates, or a candidate’s net approval rating, is about 6 percentage points.Whenever you see an article that cites polling data, you should add or subtract the true margin of error and consider how the story would change. For instance, the polling average we calculated above had Trump’s approval rating at 41 percent. The true margin of error on this number, based on the rules-of-thumb above, is about plus or minus 3 points. What if Trump’s approval rating were really 44 percent? Or 38 percent? How much would this change the story? In this case, I’d suggest, it wouldn’t change the story all that much. Trump would still be unusually unpopular for a president-elect.

By contrast, national polling averages during the final week of the campaign had Clinton up by 3 to 4 percentage points. By the rules above, the true margin of error on this number was about plus or minus 6 points. That means Clinton could really have been ahead by 9 to 10 percentage points — or that Trump could have been up by 2 to 3 points. The story would be completely different, in other words, based on even modest errors in the polling. But very little of the horse-race coverage that I read conveyed that sense of uncertainty.

You can, of course, seek to describe uncertainty with probabilities (“Clinton has a 71 percent chance of winning”) instead of with words (“Clinton’s favored, but it’s anybody’s race”). Obviously, probabilities are our preferred way of doing things around here, and they can work great for certain readers while producing confusion, or misinterpretation, among others. That’s another theme I’ll explore in our upcoming series.

But so many of the articles I read toward the end of last year’s campaign didn’t convey any sense of uncertainty at all. A small Clinton lead was misreported as a sure thing. And then a small polling error was misreported as a massive failure of the data. It’s a fairly minor part of the puzzle, but if journalists want to rebuild trust in their reporting, ending the boom-and-bust cycle in how they report on polling — first overrating its precision and then being shocked when it’s even a couple of percentage points off — would be one way to start. Doing so would make it harder for Trump, or other politicians, to undermine confidence in polls they don’t like.

Politics Podcast: Trump Vs. The Polls — Vol. II

President-elect Donald Trump is waging a new battle against polling, arguing that his approval rating is “rigged.” (He made similar claims about horserace polls during the 2016 presidential election.) The FiveThirtyEight Politics Podcast breaks down what makes approval ratings different from election polls and why Trump’s historically low rating could actually pose a challenge. The team also discusses the history of dissent at presidential inaugurations and how crowd sizes are estimated.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 12, 2017

Should Rumors Like The Trump Dossier Be News?

In this week’s politics chat, we debate the journalistic ethics and political implications of Buzzfeed’s decision to publish a memo full of unsubstantiated allegations against President-elect Donald Trump. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): Welcome, everyone. It’s been an unreal week in the political world. We’ve got the confirmation hearings, President Obama’s farewell address and Donald Trump’s first press conference in months. Then, amid all this, news broke about a “secret” dossier that the Russians supposedly compiled about Trump. Then Buzzfeed published the documents. So we’re going to talk about this dossier and how it’s been handled, but first: Nate, can you give us the top line of what happened here — what we know and don’t know?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): There’s a 35-page document, attributed to a “person who has claimed to be a former British intelligence official,” which makes various accusations about Trump, ranging from a kinky sexual episode (which is said to have provided Russia with “kompromat,” or compromising information that might be used for blackmail) to various quid pro quos between the Trump campaign and the Russian government.

The document, or previous versions of it, has been circulating in journalistic and political circles since at least October. Buzzfeed published the whole thing on Monday, when other news organizations had mostly referred to it only in a circumspect way. And lots of people are pissed at Buzzfeed for doing this, and Trump spent a lot of time bashing Buzzfeed and CNN (which also reported on the documents fairly extensively) in his press conference.

micah: So let’s start with the fundamental question: Should Buzzfeed have published the memo in full? Would we have published this? (I should say, at the outset, that there are a lot of FiveThirtyEighters who aren’t in this chat who also have strong opinions about this and would have a say on whether to publish, so this is not a perfect representation of what our internal deliberations would look like.)

natesilver: Well, I’ll ignore for a moment that this isn’t really a story in FiveThirtyEight’s expertise, which obviously is a reason that we’d lean against publishing a story on this at all. Suppose the memo was on a subject where we felt like we had a lot of in-house expertise? The answer is that … we’d have had a huge fight about it. Parts of which we will simulate for you, dear reader, right now.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Under the circumstances — a number of unverifiable and not-yet-verified allegations in a document rife with errors — no, I don’t think Buzzfeed should have published.

I think it’s journalistic malpractice to have done so.

And I say that not because I think the American public can’t decide things for themselves (Buzzfeed Editor-in-Chief Ben Smith reasoned that by publishing the full document, the site allowed readers to evaluate it themselves) but because part of the responsibility of journalists is to act as a filter for people to help them discern what is real and what is not. And I think that this story has done the industry a huge disservice at a time when it can’t afford to keep losing the public’s trust.

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): There are reasons to publish and reasons not to publish, but I don’t think the idea that we should just let people decide for themselves is a reason to publish. That’s what Wikileaks does. That’s not a news organization. That’s a clearinghouse of information that is either real or fake. And while it could be argued that journalists aren’t very good at figuring out what is good or bad information, I think it’s something quite different when you have a news organization essentially saying at the top that some of this stuff is fake.

micah: OK, Nate, give us the pro-publishing argument. I think you lean more in that direction, right?

natesilver: I’m not sure i’m pro-publishing, no. But what I’d say is this: If you’re going to write about the document at all, I think there’s a strong case for publishing the document. We probably wouldn’t have written about the document at all if the sourcing was so sketchy.

clare.malone: Well, Nate, I think you can write about the allegations in the document effectively while not exposing yourself to being caught up in propagating some untruths. CNN did that with their report on it.

natesilver: I’m just more cynical than you about how effective reporters are at doing that sort of thing.

clare.malone: We’re already seeing claims made in the documents being debunked, yet Twitter has glommed on to this golden shower thing, and I think that’s likely to be most people’s takeaway from all this. And I find that unfortunate, especially if it’s unverifiable. The top-line takeaways are being undercut, I think.

natesilver: I agree that the, uh, golden shower stuff in some ways does Trump a favor, because who the hell cares about that, really?

I’m just a lot closer to Buzzfeed’s paradigm where I distrust the idea of the media as gatekeepers.

micah: I think I’m against publishing, but something about the idea that this was widely circulating among the media and political elite but wasn’t available to the public does bother me. At the same time, I don’t buy the argument that that wide circulation made this newsworthy. Slate’s Will Oremus had a good summary of the problem here:

It [publishing] happened via a series of steps by various actors, each of whom relied on the actions of those before them to justify their own decisions. BuzzFeed presumably published it in part because CNN was reporting on it. CNN was reporting on it because intelligence officials had briefed Trump on it. Intelligence officials briefed Trump on it because senior congressional leaders were passing it around. Senior congressional leaders may have been passing it around in part because Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid alluded to it in a letter blasting FBI Director James Comey for publicizing information harmful to Hillary Clinton but not publicizing the dirt on Trump. Each act lowered the bar for those who followed to act on information that they knew might or might not be true.

clare.malone: I don’t think of media as gatekeepers so much as watchdogs for truth, Nate. That’s a real difference.

harry: The question is: Where does Buzzfeed end and Wikileaks begin? Well, that’s the question for me, anyway.

clare.malone: Gatekeeping implies some sort of power conspiracy in Washington that just wanted to keep this gossip for themselves, but that wasn’t the concern for news organizations — the concern was the report contained a lot of on-the-face-of-it errors, a lot of things that made them suspect, and a source that had a serious bias.

natesilver: I don’t think the comparison between Buzzfeed and Wikileaks makes sense.

With Wikileaks, there wasn’t really much question about the veracity of the information. The ethical issue was about how it was obtained.

harry: I meant it more in terms of just publishing stuff that isn’t exactly verifiable.

natesilver: I compare it more to how the media handled the Comey letter. Very unclear what it was all about. And yet it was treated as obviously bad news for Hillary Clinton and a huge game-changer. And it turned out to be a nothingburger. That was a massive, massive journalistic failure.

micah: How is this similar to that, though? I’m not seeing it.

harry: Of course, that was an actual letter from someone who was known.

clare.malone: Well, in the case of the Comey letter, there had been a previous investigation into Clinton by the FBI, so there was actually something for people to follow off of to make deductions that it wasn’t the best thing for Clinton. Not the best comparison, in my book.

natesilver: Meaning, the campaign press was happy to speculate based on incomplete information in the case of the Comey letter, without really having done any reporting on the story.

Come on. The difference in how this Trump revelation is being handled vs. how the Comey letter was handled is too hyperbolic to ignore. pic.twitter.com/NHY2qy7x4L

— Matt McDermott (@mattmfm) January 11, 2017

clare.malone: We’ve got one British intelligence agent who is our source in this story. No one knows him from Adam. Comey was the head of a federal agency.

micah: But with the Trump dossier, they had done a ton of reporting and not been able to verify any of the claims in the documents. That fact — that multiple media organizations and intelligence agencies have had this for a while and not been able to verify any of it — is super important in my book.

clare.malone: The dossier was published by Buzzfeed essentially, they said, because it had been the subject of Washington chatter and they thought Americans should be able to chatter about it too. But we aren’t British biddies gossipping in a village market — “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire” isn’t a good enough reason to publish something like this in the way that they did.

natesilver: Right, so you maybe shouldn’t publish anything on it at all? I’m just saying. I don’t necessarily want CNN’s filtered version of the story. And I don’t like the idea of gossip that’s circulated very widely in media circles being withheld from the public out of some sense of propriety. When in so many other cases — like the Comey letter — the press is abundantly happy to gossip in public.

clare.malone: So CNN was basically laying out for people the thing that purportedly intelligence services had told Trump in a meeting.

micah: Although there’s some question about whether they did tell Trump about this now.

Backing up a second for a moment: The dossier might have been part of the intelligence briefing not because intelligence agencies believed the allegations. Their point might have been to show that Russia was tilting toward Trump, and the proof was that Russia had dirt on both campaigns but only released stuff about Clinton. From the intelligence community’s point of view, it didn’t matter if the allegations in the dossier were true; they had a different point to make. And that’s something journalists should write about. And journalists can do that without publishing the dossier itself. They can say that it’s a bunch of unverified salacious gossip that may well have been made up by a rogue agent — but that ultimately, Russia did nothing with it. (And the FBI didn’t do much, either.)

clare.malone: Press people gossip, yes. But they don’t publish their gossip all the time for good reason. Human beings, especially reporters, want salacious things to happen — that’s just the way it is. But better angels and journalistic ethics advise us to carefully comb through things three times before we go to press.

Journalism isn’t gossip on glossy pages or newsprint. At least it shouldn’t be. I know my esteemed former Gawker friends would insert some arguments here. But I stand by my old-fashioned sanctimony.

natesilver: You’re describing a world where political journalism is a lot more truth-driven than it is in practice. Political journalism is incredibly political, and the reason that stories get published or not published or framed in a certain way often has a lot more to do with appearances than the underlying veracity of the claims.

micah: But Nate, that’s not reason to just throw up our hands and say, “Well, let’s just publish everything.” I’d rather us say, “Let’s do a better job of filtering and framing.”

natesilver: I just think some of the sanctimony about what Buzzfeed did is hypocritical.

harry: Would you have published it?

micah: The more I think about this, the more publishing the document seems like a fundamental abdication of journalistic duty — to put it in really obnoxious terms. We, for example, would never publish a data set and say, “We’re not sure if this is right, but have at it!”

clare.malone: Right.

natesilver: But what if lots of news organizations were publishing snippets of the database? And characterizing the database? And maybe even mischaracterizing it?

micah: That doesn’t persuade me at all. So what? We would write about them mischaracterizing and misusing it. Does publishing the full data set add truth into the world? No.

natesilver: It possibly adds to truth relative to publishing parts of the database.

clare.malone: Basically, so far, what your argument seems to be to me, Nate, is that we have journalists with bad standards and … we should realize that and get past our demand that journalism be better?

I’m missing the philosophical argument here about our role as journalists. And I want to hear the baseline opposing view!

natesilver: I think our role as journalists is to discover the truth.

clare.malone: OK. I agree.

micah: Should we ask our colleague Kyle Wagner (erstwhile Deadspin editor) to make the opposing argument?

kyle has joined the chat

clare.malone: Glad to have Kyle, but also want to hear Nate’s say.

natesilver: I guess something just feels wrong to me about the idea that dozens of reporters have seen this document, but that the general public can’t be trusted with it.

clare.malone: Because it might be untrue. That’s the reason. And news organizations publishing what might be internet rumor or Kremlin misinformation is really problematic.

What was there to report is that this was presented to Trump by intelligence agencies as something that was being peddled — rumors of Trump having close, possibly illegal ties to Russia. But they weren’t sure of that info either.

harry: Clare is a lot more convincing to me, I’ll tell ya.

clare.malone: When you put a document out there, unfiltered, as a news org, you’re lending your imprimatur to it.

micah: That’s the thing: In an ideal world, a reader visits nytimes.com or fivethirtyeight.com or buzzfeed.com and starts with the premise that everything they’re reading is true. Publishing this memo hurts that cause. If you want to live in a world where the media leans much more heavily toward publishing everything and then the media and the public engage in some type of Socratic effort to move everyone toward the truth, that’s defensible, but I just can’t imagine how that would work.

clare.malone: By publishing, you’re saying, implicitly at the very least, that you think there is substance to this.

natesilver: My stance is that then you shouldn’t touch the subject at all. I don’t like when reporters try to make superfine distinctions about how to characterize the dossier. If none of it is verifiable, don’t even go near it.

I’ve spent almost 10 years covering how the political press reports on polling data, and I’d say nuance isn’t really a strength.

micah: That’s 100 percent true.

clare.malone: But then we have to make it better, right? There are nuanced reporters. We should be encouraging that, not throwing up our hands and saying, “Nothing to be done here, they’re all fools.”

kyle: I can see the argument for not running the story at all — though I’d disagree with it — but once the CNN report was out there, the document itself was the story. The absurdity of the claims and the shaggy provenance of the report are crucial parts of that story. CNN tried to run the making-the-sausage story, but they left out the pieces that made it such a complex mess.

micah: So Kyle, your argument is to write a story about how there’s this shady/unsubstantiated memo rocketing around? Does that require publishing the memo?

clare.malone: You can publish a story about it and say that the claims haven’t been verified. It’s pretty simple. And that’s the reason why you’re not pubbing the claims.

And your language about the report is more vague, sure, but that seems responsible.

I would note here that I am the daughter of a lawyer and I feel that particularly in the internet age, people seem to feel free to lob around accusations and take a “guilty until proven innocent” stance on things that I’m fundamentally uncomfortable with.

kyle: If you’re going to do the story, I don’t see how you don’t run the memo. Lots of places chose not to run the story! CNN ran the story about this mysterious document that left readers with big, obvious questions that CNN had the answers to, but it didn’t share them.

micah: What questions?

kyle: “What are these claims that are so salacious that they’re eyes-only for the Gang of Eight and found their way to John McCain’s desk and are still being passed around to Trump and Obama?”

natesilver: To some extent, this is a question of defaults. I think Buzzfeed’s default is “the public has a right to this information as much as we do.” And I think I mostly agree with that.

micah: Margaret Sullivan captured your point about defaults succinctly:

Smith said he did so because his, and BuzzFeed’s preference and philosophy is, essentially, “When in doubt, publish.” But at many other news organizations, the rule is caution: “When in doubt, leave it out.”

harry: The more I think about this the less I wonder if this should have been published. I am not sure if any of this is true.

kyle: Micah didn’t ask me, but referring to the claims without actually stating them is no different from The New York Times refusing to publish the word “fuck” when a public figure says “fuck.” You’re leaving the reader with a needlessly incomplete accounting of facts.

clare.malone: I will accede that there is a fair amount of political journalism that falls into a certain penumbra — there is politicking between political figures and agencies and bodies. So there is reporting that gives the broad outlines of strategic thinking and back-and-forths. The idea that intelligence agencies are worried about ties to Russia and the president-elect are important ones to note to the American people, especially given previous reporting. You could characterize the intelligence community presenting Trump with allegations that he had made “inappropriate contact” with Russian intelligence agencies but say that the claims were still being investigated or some such.

We’re trying to help people synthesize and understand the world, and part of that synthesis is eliminating the hooey.

micah: So let’s talk briefly about the fallout from all this before we wrap. First, the relationship between Trump and the press seems to have reached a new low (and it was already really bad) just as Trump is about to take office. He bashed the hell out of the press in that news conference. And that CNN reporter pushed back pretty hard.

That terrible relationship seems like not a good thing, but it helps Trump in his crusade against the media, right?

natesilver: Oh, don’t get me wrong, I think the politics of this are quite helpful for Trump.

clare.malone: Oh yeah.

natesilver: It was nicely timed from his perspective, in terms of letting him claim the moral high ground in the press conference.

harry: Well, hold on a second. I don’t think this loses him a single supporter. But I’m not sure it helps him gain one either.

clare.malone: I dunno, Harry.

kyle: To steal a phrase from a former boss, I think this serves as a literal vaccination against future stories or claims with anything but the most undeniable proof.

micah: Yeah, I think that’s right — at least with his supporters.

harry: Why would it help him? (In terms of polling, anyway.)

micah: Won’t some swing voters who aren’t reflexively anti-media look at the facts here and side with Trump?

clare.malone: Yeah, and I think, Kyle, that that sort of nuclear logic is not quite right or … logical.

natesilver: It also distracts from Trump’s conflicts of interest, which was the ostensible subject of the press conference.

harry: That’s a different tack.

clare.malone: I mean, forget gaining supporters, it’s eroding trust in the institution of the press — that has cascading effects.

harry: I could see that happening, where it distracts us from things that could hurt Trump.

natesilver: I don’t know. I’m not thinking about his approval ratings or anything like that, though. I’m thinking about the extent to which the dossier and how it was reported will make the press more fearful or fearless about covering Trump in the future.

I thought one of the brilliant things Trump did was to praise the news organizations who didn’t publish the memo. Give them a little treat for being obedient.

clare.malone: Jesus, you are cynical.

micah: I’m not sure reporters will see that as a reward.

kyle: Reporters, maybe not, but publishers?

micah: Publishers, yeah. Good point.

harry: These are arguments I’m more open to. And questions that I cannot answer. We still haven’t heard the last about this report, I don’t think.

micah: But if next week, some media outlet has some other magical dossier, and let’s say they’re 90 percent confident in the claims contained therein, do they publish? Aren’t they less likely to publish now? And at 90 percent or 95 percent, don’t we want them to publish?

clare.malone: These things are case-by-case calls. There’s no way that we can sit here and make that call for people.

natesilver: This sort of gets back to the conversation about defaults.

micah: No, I know, but I’m just saying they’re less likely to publish now. Given all the blowback against Buzzfeed.

clare.malone: Are they?

harry: Most news organizations wouldn’t have done what Buzzfeed did. We know that because they didn’t.

clare.malone: I don’t know. It would make me hungrier to publish something that I felt confident I had reported out. And take the inevitable spitball from Trump as a mark of honor. I’m going to stand up for reporters here!

As long as your mother or your dog loves you, you shouldn’t worry about who you offend, right? As long as it’s verifiable and the truth.

micah: Yeah, I think most reporters would love to be attacked by Trump, actually.

harry: If you want someone to love you and you’re in the media, get a dog.

micah: My dog loves me:

natesilver: Do these principles need to be in conflict, though? Suppose I believe both of the following: 1. reporters ought to make a lot of effort to determine the veracity of what they write, and 2. there shouldn’t be that much of a distinction between reporters and citizens, and we should generally avoid reporters knowing things that citizens don’t know.

micah: But those are in direct conflict, Nate.

natesilver: Really? What if you reported out a very in-depth story about the dossier that tried to sort through the claims as best it could but then also published the dossier to show your source material.

kyle: Take a dumb sports analogy: If a general manager was trying to tank a player’s trade value with ridiculous claims, the decision to publish isn’t based on whether or not those claims are true, it’s based on the fact that this is a thing that someone is trying to sell to other GMs. And, of course, you include what the ridiculous claim is, because that’s the reason it is a story.

micah: Hmmm … that’s actually somewhat persuasive, Kyle.

clare.malone: But there is training that reporters go through, Nate. Knowing who to call for comment, knowing your responsibilities for reaching out to such and such.

Citizen bloggers or whatever don’t have that same background most of the time. I’m not disputing the idea that reporters should fill citizens in on pretty much what they know — that’s our job — but if a reporter is genuinely unsure of something, I think it’s prudent to hold back until you know more and can more fully educate the public.

natesilver: At FiveThirtyEight, we quite often say, “Here’s what’s going on the best that we can figure out, but if you don’t trust us, go download the data yourself.”

micah: But the data isn’t in question there, Nate, the conclusions that should be drawn from it are.

Think about all the reporting that goes into a typical story. Think about all the calls you make and all the B.S. that gets fed to you — that should be left out.

natesilver: So, would you have a problem if a news organization started to run a transcript of every interview they conducted?

micah: Yes.

Generally, we want there to be a really high signal-to-noise ratio in American media. That would add a ton of noise.

harry: (I, for one, wouldn’t read those transcripts.)

natesilver: Having had my views misquoted and mischaracterized so many times, I’d be way in favor of news organizations often publishing transcripts.

micah: But that’s an argument for better filtering, not for no filtering.

natesilver: It’s also an argument for recognizing our human limitations as filters.

And that journalists have a lot of incentives that compete with truth-seeking, in terms of making them better filters.

clare.malone: Ton of noise, I agree. But technically, if the conversation was on the record, sure, run the transcript. What’s important with quotes is always context. Context problems are mostly what pols/public figures/Nate Silver complain about when being misquoted or misconstrued, right?

micah: Sure. I’ve been at FiveThirtyEight for six years now and been around for several separate flurries of stories about us, and I’d say probably only 10 to 20 percent are fundamentally accurate. But I don’t think those writers publishing transcripts of all their interviews would help.

micah: OK, we gotta wrap. Closing thoughts?

clare.malone: Well, now I’m worried Nate’s gonna fire me and hire a 13-year-old citizen blogger.

January 9, 2017

Politics Podcast: Trump And The Senate

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast looks at the budding relationship between President-elect Donald Trump’s administration and the U.S. Senate. Confirmation hearings for Trump’s Cabinet picks are scheduled to begin this week, and the debate over how to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act is underway. The crew discusses the Cabinet nominees that are likely to receive the most pushback, and science reporter Anna Maria Barry-Jester joins to talk about options for repealing and replacing Obamacare.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button above or by downloading it in iTunes, the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen.

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes. Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 5, 2017

Make College Football Great Again

Ohio State somewhat embarrassed the Big Ten in getting shut out by Clemson 31-0 in the College Football Playoff semifinal last week. Still, hindsight is 20/20, and I don’t necessarily begrudge the playoff selection committee for having turned down Penn State, which won the Big Ten championship, in favor of the Buckeyes. Ohio State was probably the better regular-season team and had fewer losses against a tougher schedule. Penn State — which for its part blew a big lead to lose the Rose Bowl to USC — had a head-to-head win against Ohio State and the conference title, two factors the committee explicitly says it considers in ranking the teams. It was a tough decision.