Phil Simon's Blog, page 70

November 13, 2014

Crowdsourcing Healthcare

Do you whip out a map while you’re driving these days? At work, do you send letters or intraoffice memos like Don Draper does? Do you still own a fax machine?

Do you whip out a map while you’re driving these days? At work, do you send letters or intraoffice memos like Don Draper does? Do you still own a fax machine?

Of course not.

Thanks to technology, just about every industry has dramatically changed in the last twenty years—with one glaring omission: healthcare.

Go to a doctor’s office and it usually feels like 1995 or even 1975. Healthcare remains plagued by tens of billions of dollars of annual waste, fraud, inefficiency, and general bureaucracy.

Healthcare: More Money, More Problems

Maybe none of this would matter if it wasn’t so large. In the US alone, healthcare accounts for nearly $4 trillion of the country’s GDP. What’s more, that number is increasing at a rate of six to seven percent per annum, considerably higher than inflation.

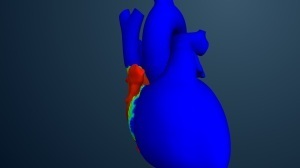

There’s no simple solution to the mess that is healthcare. As I pointed out on CNBC last year, however, data and technology can go a long way towards making healthcare work better. For instance, technologies like computational modeling look particularly promising. Imagine doctors being able to simulate what each patient’s heart looks like before cutting him or her open. Who can argue with safer, less expensive, and superior healthcare? Regardless of your politics or feelings about Obamacare, advancements like these offer enormous hope.

Along these lines, Dassault Systèmes recently signed a five-year collaborative research agreement with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The pact calls for the treatment of heart disease via the insertion, placement, and performance of pacemaker leads and other cardiovascular devices.

Dassault Systèmes isn’t going about such an endeavor on its own, though. The company is working closely with the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) to accelerate the approval process of medical devices. Dubbed the Living Heart Project, Dassault has plenty of help in the form of leading cardiologists, medical device companies, and academic researchers.

A New Model: Sharing Technology and Benefits

The 30 contributing member organizations include more than 100 cardiovascular specialists from across research, industry, and medicine. DSS is proving each party with access to its heart simulator.

Collaboration among pharmaceutical companies isn’t exactly common.

Anyone with a modicum of knowledge about healthcare knows that historically large healthcare organizations haven’t always played nice with each other. Collaboration among pharmaceutical companies isn’t exactly common. What’s more, scientists have often valuable withheld information from each other. Some have even bickered about who discovered diseases, often to the detriment of those affected. AIDS is a case in point. (See the excellent 1993 movie And the Band Played On.) Getting disparate parties and warring factions to work together is almost always far easier said than done.

To avoid these thorny issues, Dassault is employing a crowdsourcing model that both protects individual intellectual property and lets them reap potential benefits. Other goals include spurring innovation, improving patient reliability, and reducing costs. Interestingly, the project has already borne fruit. For instance, it validated the efficacy of a novel valve assist device prior to insertion in a real patient and understand the progression of heart disease.

Simon Says

Let’s hope that collaboration and innovation like this increasingly become the rule in healthcare, not the exception.

Feedback

What say you?

This post originally ran on HuffPo.

The post Crowdsourcing Healthcare appeared first on Phil Simon.

November 12, 2014

The Case Against a Data Center of Excellence

I recently had lunch with some new friends, one of whom has a 17-year-old son entering college. He’s really interested in math and statistics.

I recently had lunch with some new friends, one of whom has a 17-year-old son entering college. He’s really interested in math and statistics.

Given the insane cost of college education, why not graduate with a degree in a white-hot field? At the top of the list these days is data science. Demand far exceeds supply. If I were a sophomore at Carnegie Mellon with a $63,000 annual bill, you can bet that I’d strongly consider going down this road.

This begs the question: Does an organization really need a data scientist to “do” Big Data?

Culture and Data Science

The answer is an equivocal no. You can rent them on sites like Kaggle and an emerging group of competitors.

More generally, rare is the organization that fully taps the potential of its employees. No, you can’t send a bright analyst to a two-day training course and expect her to become Nate Silver. You can, however, encourage employees to experiment and reward data-oriented thinking and solutions. And you can hire for numeracy. Why should any position not require basic fluency with statistics?

Above all, you can reject the notion of a center of excellence, defined as:

a team, a shared facility or an entity that provides leadership, evangelization, best practices, research, support and/or training for a focus area. The focus area in this case might be a technology (e.g. Java), a business concept (e.g. BPM), a skill (e.g. negotiation) or a broad area of study (e.g. women’s health). A center of excellence may also be aimed at revitalizing stalled initiatives.

Why centralize knowledge in one pocket of the organization? Why not diffuse it as much as possible? On HBR, Michael Schrage argues against black boxes and centers of analytic excellence.

Simon Says

I think back to the time that I spoke at Netflix headquarters. With the exception of the receptionist at the front desk, just about everyone I met there struck me as analytical, even the company’s head of PR. Is it any wonder that it is so successful?

Reject the notion of a center of excellence.

Your organization may not be able to catch up to Netflix next week, next month, or next decade. Be that as it may, relying upon only a small cadre of “experts” to help understand, interpret, and act upon data is rife with peril. A single defection may hamstring a key department, product launch, or even the entire organization. Do what you can to diffuse expertise.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business, but the opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business, but the opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

The post The Case Against a Data Center of Excellence appeared first on Phil Simon.

November 5, 2014

The Glass Cage

In five years, will your doctor be taking orders from a tablet and an algorithm? It sounds farfetched, but cost pressures and technological advances are leading us down that very road.

In five years, will your doctor be taking orders from a tablet and an algorithm? It sounds farfetched, but cost pressures and technological advances are leading us down that very road.

Google is one of several companies trying to bring driverless cars to the masses. Sophisticated CAD programs are changing the very essence of architecture—and not necessarily for the better. Human skill is less important than ever in farming, manufacturing, and flying a plane. Some people believe that pilotless planes represent the future. Home Depot is testing robot “employees”, the recent subject of an absolutely hysterical Last Week Tonight skit. (For my money, Jon Oliver hosts the best show on TV right now, but I digress.)

Far less understood, though, is where all of these newfangled devices, software programs, and systems are taking us. Against this backdrop, I recently read Nick Carr’s The Glass Cage: Automation and Us. (Disclaimer: His publisher sent me a copy gratis.)

Where are we going?

The Glass Cage is neither an anti-automation screed nor a polemic. The two-fold premise of the book is both profound and simple: a) to help us understand how we got to now, to paraphrase Steven Johnson’s latest book; and b) to question whether our direction is wise.

Just because we can automate something doesn’t meant that we should.

Like his other texts, Carr has clearly done a great deal of research. There’s the obligatory story of the Luddites. That much I expected. I figured that Carr would mention cleaning robotic vacuums. Ditto for Google’s autocomplete feature. I was unaware, however, of the extent to which many other facets of daily life are being automated (read: architecture, air travel, and medicine). It’s either cool or scary, depending on your point of view. Maybe it’s a bit of both.

Carr questions the the libertarian ethos so prevalent in today’s Silicon Valley. More than ever, we view disruption as an unalloyed good. AirBNB and Uber are cases in point. For several reasons, though, all of this technology should give us pause. First, are these new, automated experiences better and safer than their predecessors? Carr points to research that questions and/or refutes both claims.

Even if we take these improvements for granted, what are the human ramifications? Not too many people seem to be asking question such as:

We will be able to critically think when algorithms and GPS devices effectively do that for us?

Will early dementia set in because we don’t exercise our brains? (The evidence suggests that it may.)

We will be able to spell when we know that spellcheck will take care of that for us? What about math and calculators?

Has automation resulted in tremendous progress over the last 100 years—and particularly the last 15? No doubt, but at what cost?

And, perhaps most important, will automation eventually put us all out of work?

Carr manifests the drawbacks of automation. He both implicitly and explicitly asks critical questions like these throughout The Glass Cage. Brass tacks: Just because we can automate something doesn’t meant that we should.

Near the very end of the book, Carr drops an interesting piece of knowledge. The word robot derives from the Czech term for servitude. It’s a fascinating double entendre. Automation is increasing faster than ever, fueled by technological, economic, and societal factors, a trend with no signs of abating. The Glass Cage forces the reader to think about where we’re going, how fast, and what it all means.

Originally published on HuffPo.

The post The Glass Cage appeared first on Phil Simon.

November 4, 2014

Curing My E-mail Addiction: The Revelation

Excerpted from my forthcoming book, Message Not Received: How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications.

Excerpted from my forthcoming book, Message Not Received: How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications.

Headquartered in the bucolic town of Cooperstown, New York, a stone’s throw from the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame, Bassett Healthcare is a three-hospital network of primary and specialty care providers. The organization employs about 4,500 people and, in the late 1990s, began pushing the limits of its legacy enterprise system. In 2000, Bassett purchased and successfully deployed the Lawson Software enterprise resource planning (ERP) system.

In 2007, Bassett decided to upgrade its time-and-attendance application. Lawson had launched a new application called Absence Management. This coincided with the eventual retiring — or, in industry parlance, the decommissioning — of its predecessor, Time Accrual.

Bassett needed someone to lead the upgrade and, as it so happened, I was a very experienced consultant with the Lawson HR suite. I had even helped a similar healthcare organization perform the same upgrade earlier that year. For four months in 2007, Bassett contracted me to do the same.

Over the course of my time at Bassett, I worked on-site for four days each week. I trained employees in the new application, configured it, tested it, created user guides, validated results, loaded data, investigated issues, called in support requests, participated in meetings, and ultimately hit the switch. You could say that I was a jack-of-all-trades, a human Swiss Army knife.

Once I activated the new Lawson Absence Management module, there was no going back. (The specific details aren’t terribly important here.) Bottom line: That bell couldn’t be unrung.

Bassett consisted of three disparate legal entities. Because of that and some system considerations, I had to perform the final data conversion and system activation three times, each in a separate production or live environment. In so doing, I would be generating hundreds of thousands of transactions that would affect the holiday, sick, and vacation time of more than 4,000 active employees — and twice as many former ones.

Adding to the complexity, I would be activating Absence Management during business hours. IT certainly wasn’t about to revoke everyone’s system access just for me, and therein laid a problem. Because dozens of Bassett’s HR and payroll employees could concurrently access Lawson with me, they could unknowingly create issues that would complicate or even derail the migration altogether.

I knew that timely communication would be essential for a successful upgrade, a point that I made during the final few meetings before we went live.

It’s Go Time

I arrived in the office before 7 a.m. on activation day. I was prepared to face the challenges that lay ahead. Over the course of the eight-hour conversion, I did my best to keep everyone informed, via e-mail of course. I diligently advised Bassett senior management and anyone remotely involved of my progress. My long, incredibly detailed e-mails explained how the last step went, what I was doing now, and my next course of action. In short, I tried to follow the Golden Rule. I wanted people to know exactly what they were and were not supposed to do — and when.

I thought that my e-mails were as clear as possible. In reality, though, I was only confusing people. They simply couldn’t handle the volume of detail-laden messages I was sending. At one point, a Bassett employee named Julie visited my desk, unsure about the current status of the migration.

I thought that my e-mails were as clear as possible. In reality, though, I was only confusing people.

“Didn’t you get my e-mail?” I asked, a bit perplexed at how she could possibly be in the dark after my exhaustive communications efforts.

“Which one?” Julie chuckled.

At that moment, I had my revelation. Julie was absolutely right. In two words, she showed me the error of my ways. Yes, my heart was in the right place; I was just trying to keep everyone informed — really informed. In doing so, however, my actions were having the precisely opposite effect. I vowed from that point onward to change how I communicated. I would send less e-mail.

Just to finish the story, the upgrade went off without a hitch. Everyone was happy, and I returned to Bassett a few years later to do some additional work.

Originally posted on Medium.

The post Curing My E-mail Addiction: The Revelation appeared first on Phil Simon.

November 3, 2014

The Myth of the Big Data Switch

More and more organizations have jumped on the Big Data train the 18 months since the publication of Too Big to Ignore. There’s a reason that Hadoop enabler Hortonworks recently announced $100M in additional funding. This currently values the company at a cool $1 billion. Not exactly WhatsApp, but not too shabby either.

Some argue that that eye-popping valuations like these prove that we’re in a tech bubble. Maybe, but I don’t think so—at least not with Big Data. Mark my words. In a few years, it will no longer be the sole purview of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Netflix, Twitter, and other billion-dollar behemoths. I firmly expect greater adoption from progressive mid-market organizations and even small businesses. Organizations are going to need plenty of help in this regard. They can’t do it alone.

Some argue that that eye-popping valuations like these prove that we’re in a tech bubble. Maybe, but I don’t think so—at least not with Big Data. Mark my words. In a few years, it will no longer be the sole purview of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Netflix, Twitter, and other billion-dollar behemoths. I firmly expect greater adoption from progressive mid-market organizations and even small businesses. Organizations are going to need plenty of help in this regard. They can’t do it alone.

Big Data: Not a Weekend Hackathon

Does mean that organizations can immediately take advantage of vast troves of unstructured data in in any meaningful way? In short, probably not. It just doesn’t work that way. Perhaps the key question is: What’s your model going to be?

Beyond that, relatively few organizations possess the requisite tools to effectively handle Big Data, never mind the internal expertise. Making sense out of Big Data is going to take some time.

Why can’t organizations just use existing data-management tools?

This seems like a logical question. When it comes to unstructured data, relational databases and business intelligence (BI) applications are simply not built to house, retrieve, and interpret petabytes of unstructured data.

Sure, text analytics may manifest some quick hits, but these are the exceptions that prove the rule. Generally speaking, Big Data is different on many levels than ERP and CRM “projects.” To paraphrase The Who, the old boss isn’t the same as the new boss.

Simon Says: It’s a Marathon, Not a Sprint

Even a skilled and experienced partner doesn’t activate Big Data over a weekend, a month, or even a quarter.

Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Google, and others are in such powerful positions today because each realized a long time ago that this stuff matters. They then each actually did something about it. Years later, each has has effectively accumulated significant advantages over their peers. None of this happened over the course of a few months or even a year; we’re talking about a decade or more.

I question whether most CXOs understand the enormity of the task that lies ahead. Even with the help of a skilled and experienced partner, an organization doesn’t “activate” these types of tools; it is the antithesis of a weekend hackathon. Put differently, there’s no magic “Big Data switch.”

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business, but the opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business, but the opinions in this post are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

The post The Myth of the Big Data Switch appeared first on Phil Simon.

October 31, 2014

Has E-Mail Peaked?

The following is excerpted from How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications (Wiley, March, 2015).

For a long time now, e-mail has served as the default mode of business communication, and a fair amount of research confirms as much. For instance, in 2013, the Radicati Group released its E-mail Statistics Report, 2013–2017. Among the study’s most interesting findings:

E-mail remains the go-to form of business communication. In 2013, business e-mail accounts totaled 929 million. The number of mailboxes is expected to grow annually at a rate of 5 percent over the next four years, reaching over 1.1 billion by the end of 2017.

More than 100 billion business e-mails were sent in 2013 every day. That number is expected to exceed 130 billion by 2017.

To be sure, these are unwieldy numbers, but what do they mean to you?

In July 2012, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) released a report titled “The Social Economy: Unlocking Value and Productivity Through Social Technologies.” MGI found that knowledge workers on average now spend fully 28 percent of their work time managing e-mail. The math here is scary: People who work 50 hours per week spend 14 hours stuck in their inboxes. Put in remarkable historical context, a generation ago, professionals spent no time sending and reading e-mails. Today, those tasks constitute nearly one-third of their workday. The McKinsey report recommends that workers use more collaborative tools in lieu of e-mail. In effect, we can “buy back” 7 to 9 percent of our workweeks.

In July 2012, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) released a report titled “The Social Economy: Unlocking Value and Productivity Through Social Technologies.” MGI found that knowledge workers on average now spend fully 28 percent of their work time managing e-mail. The math here is scary: People who work 50 hours per week spend 14 hours stuck in their inboxes. Put in remarkable historical context, a generation ago, professionals spent no time sending and reading e-mails. Today, those tasks constitute nearly one-third of their workday. The McKinsey report recommends that workers use more collaborative tools in lieu of e-mail. In effect, we can “buy back” 7 to 9 percent of our workweeks.

All of this is to say that e-mail has come a long way since its advent in the 1960s as a tool for government types, techies, and wonks. For nearly a quarter-century, it remained very much a niche form of communication. Beginning in the mid- to late 1990s, e-mail began its march into—and eventual dominance of—the corporate world. It quickly supplanted the intraoffice memo. Score one for the environment.

Still, its early adoption was anything but smooth. Many VPs employed secretaries to type for them; they did not want to be self-sufficient. Back then, storage costs were considerable. To combat this, IT departments typically restricted the size of employee inboxes to now laughable levels. A message sent with a 3-megabyte attachment would typically bounce back.

Most corporations, nonprofits, and small businesses quickly realized that e-mail was becoming an indispensable internal and external communications tool. Business was willing to pay for fast, reliable, secure e-mail, and software vendors responded. As a result, the reliability of e-mail has significantly improved from its early days. Sure, with rare exception, messages sometimes inexplicably vanish, perhaps because of a glitch in the matrix. Spam filters sometimes incorrectly flag messages before they reach their intended recipients. Most organizations have relaxed their message size limits, if not altogether eliminated them. Data storage has never been less expensive.

Yes, spam is still a problem, Bill Gates’s proclamations about its impending demise notwithstanding. (The ex-CEO famously predicted in 2004 that spam as we know it would be cured by 2006.) Sometimes e-mail accounts are hacked. Everyone (including yours truly) has mistakenly replied to everyone copied on an e-mail instead of just to the sender—and eaten a fair amount of crow for doing so. Beyond that, the novelty of sending around time-sucking chain e-mails has thankfully waned. We now have social networks and blogs to share jokes and stories that once routinely contaminated our inboxes.

The overall e-mail experience might be qualitatively better than a decade ago. To be sure, though, it continues to suffer from profound problems. The next section examines them.

Originally published on Information Week.

The post Has E-Mail Peaked? appeared first on Phil Simon.

Has E-mail Peaked?

The following is excerpted from How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications (Wiley, March, 2015).

For a long time now, e-mail has served as the default mode of business communication, and a fair amount of research confirms as much. For instance, in 2013, the Radicati Group released its E-mail Statistics Report, 2013–2017. Among the study’s most interesting findings:

E-mail remains the go-to form of business communication. In 2013, business e-mail accounts totaled 929 million. The number of mailboxes is expected to grow annually at a rate of 5 percent over the next four years, reaching over 1.1 billion by the end of 2017.

More than 100 billion business e-mails were sent in 2013 every day. That number is expected to exceed 130 billion by 2017.

To be sure, these are unwieldy numbers, but what do they mean to you?

In July 2012, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) released a report titled “The Social Economy: Unlocking Value and Productivity Through Social Technologies.” MGI found that knowledge workers on average now spend fully 28 percent of their work time managing e-mail. The math here is scary: People who work 50 hours per week spend 14 hours stuck in their inboxes. Put in remarkable historical context, a generation ago, professionals spent no time sending and reading e-mails. Today, those tasks constitute nearly one-third of their workday. The McKinsey report recommends that workers use more collaborative tools in lieu of e-mail. In effect, we can “buy back” 7 to 9 percent of our workweeks.

In July 2012, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) released a report titled “The Social Economy: Unlocking Value and Productivity Through Social Technologies.” MGI found that knowledge workers on average now spend fully 28 percent of their work time managing e-mail. The math here is scary: People who work 50 hours per week spend 14 hours stuck in their inboxes. Put in remarkable historical context, a generation ago, professionals spent no time sending and reading e-mails. Today, those tasks constitute nearly one-third of their workday. The McKinsey report recommends that workers use more collaborative tools in lieu of e-mail. In effect, we can “buy back” 7 to 9 percent of our workweeks.

All of this is to say that e-mail has come a long way since its advent in the 1960s as a tool for government types, techies, and wonks. For nearly a quarter-century, it remained very much a niche form of communication. Beginning in the mid- to late 1990s, e-mail began its march into—and eventual dominance of—the corporate world. It quickly supplanted the intraoffice memo. Score one for the environment.

Still, its early adoption was anything but smooth. Many VPs employed secretaries to type for them; they did not want to be self-sufficient. Back then, storage costs were considerable. To combat this, IT departments typically restricted the size of employee inboxes to now laughable levels. A message sent with a 3-megabyte attachment would typically bounce back.

Most corporations, nonprofits, and small businesses quickly realized that e-mail was becoming an indispensable internal and external communications tool. Business was willing to pay for fast, reliable, secure e-mail, and software vendors responded. As a result, the reliability of e-mail has significantly improved from its early days. Sure, with rare exception, messages sometimes inexplicably vanish, perhaps because of a glitch in the matrix. Spam filters sometimes incorrectly flag messages before they reach their intended recipients. Most organizations have relaxed their message size limits, if not altogether eliminated them. Data storage has never been less expensive.

Yes, spam is still a problem, Bill Gates’s proclamations about its impending demise notwithstanding. (The ex-CEO famously predicted in 2004 that spam as we know it would be cured by 2006.) Sometimes e-mail accounts are hacked. Everyone (including yours truly) has mistakenly replied to everyone copied on an e-mail instead of just to the sender—and eaten a fair amount of crow for doing so. Beyond that, the novelty of sending around time-sucking chain e-mails has thankfully waned. We now have social networks and blogs to share jokes and stories that once routinely contaminated our inboxes.

The overall e-mail experience might be qualitatively better than a decade ago. To be sure, though, it continues to suffer from profound problems. The next section examines them.

Originally published on Information Week.

The post Has E-mail Peaked? appeared first on Phil Simon.

October 30, 2014

Thoughts on Simpler Business Language

I have often wondered what the business world would be like if people routinely didn’t talk about “cloud-based next-generation platforms” and honestly expect to be understood.

I have often wondered what the business world would be like if people routinely didn’t talk about “cloud-based next-generation platforms” and honestly expect to be understood.

While we’re at it:

What if every new tech release wasn’t superfluously branded “as a service”?

What if self-anointed thought leaders recognized the accelerating rate of technological change and tried to communicate as clearly as possible?

In this era of pervasive communications, what if people went out of their way to be understood—and not just drop neologisms, jargon, and buzzwords?

Word-processing applications ship with spell check and grammar check. What if they also included checks for coherence? What if Microsoft Word stopped users from 70-word sentences that, while creating grammatically correct, made absolutely no sense when read?

What would this world look like? Maybe some management consultants wouldn’t have very much to say. Maybe they’d have to relearn their mother tongues.

Some argue that our tech-heavy, rapidly moving world necessitates a completely new language. The old rules of English no longer apply.

Bullocks.

There are plenty of good tech writers who communicate complex ideas in understandable ways. Steven Levy is one of them.

If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough. –Albert Einstein

— Phil Simon (@philsimon) October 30, 2014

Simon Says

Give simplicity a try at work. You may very well find that others respond better to your suggestions and directions. Ditch that incredibly long sentence in lieu of two or three sharper, shorter ones.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Thoughts on Simpler Business Language appeared first on Phil Simon.

October 28, 2014

Proprietary APIs: A New Tool in the Age of the Platform

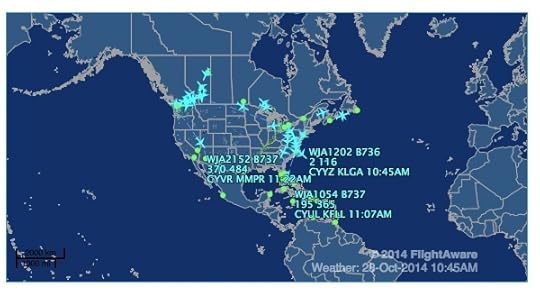

For a long time now, apps like FlightAware have helped millions of air travelers track the location and status of their flights. If you’re picking up your friend at the airport, it seems odd these days not to know the time at which he or she will arrive—even with inevitable delays.

But how does this magic happen behind the scenes?

The Age of APIs

Non-techies are probably oblivious to today’s almost-pervasive usage of application programming interfaces. (At a high level, APIs make it very easy for developers to connect networks, individual devices, and information streams.) And that’s kind of the point. Most of us aren’t developers; we just want to easily use the cool stuff that developers create without jailbreaking our devices.

APIs have been a boon for companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, Twitter, and others, a point I make in The Age of the Platform. Without robust ways to build apps and services, developers wouldn’t be able to do what they do (read: create apps that improve our lives—and, of course, allow us to easily waste time). Brass tacks: Each company would not be nearly as successful without APIs and their cousins, software development kit (SDKs).

Foolish is the executive, though, who ignores the downsides of platforms and, specifically, APIs. Case in point: Howard Lindzon.

A few years ago, the founder of StockTwits learned this lesson the hard way. His company relied on the Twitter API to generate cashtags. When a user clicked on $AAPL, for instance, he or she would see financial information about Apple’s stock price, financials, and the like.

Pretty snazzy, right?

Organizations have to start grappling with the costs if inaction.

Lindzon woke up one morning in July of 2012 to find that Twitter loved Lindzon’s idea. In fact, Twitter decided to implement it, obviating the need for its users to visit Stocktwits at all. Aside from “old-fashioned” hashtags, Twitter now supported these very same cashtags. Thanks for the idea, Howard. Your check is not in the mail.

Lindzon was incensed. In his view, Twitter had hijacked his idea. Perhaps, but sans Twitter, it’s very doubtful that StockTwits would have done nearly as well in the first place.

Brass tacks: in the Age of the Platform, frenemies abound. The same companies that let startups quickly blossom can quickly become scourges.

All of this begs the question: What’s the solution to the platform dilemma?

More Tools Than Ever

Ah, if it were only that simple. Those looking for easy answers will continue to be unsatisfied; there is no one right way to crack this nut. Interestingly, though, some companies have taken to building proprietary APIs as a means of avoiding StockTwits-like situations. They understand all too well that it’s incredibly risky to rely so heavily on powerful organizations and their APIs.

It’s high time that organizations begin grappling with the costs of inaction.

For instance, a few years ago, third parties were scraping valuable flight data and metadata from WestJet Airlines’ website. This was causing a number of problems, including increasing its site load time, a critical consideration for increasingly impatient consumers and search engines alike.

There wasn’t much that WestJet could do about it circa 2012. Omitting this information from its site would curtail if not destroy its business. Without the data, how could a customer book a flight? WestJet would just have to grin and bear it.

Well, it’s no longer 2012. Organizations today canput more arrows than ever in their quivers, a point underscored at this year’s IBM Insights. In the case of WestJet, the company effectively built its own bridge via the IBM API Management solution. The technical details aren’t terribly important here, but now apps like FlightAware can easily—and automatically—pull real-time data from WestJet (and other airlines) without any scrambling behind the scenes. Perhaps even more important, WestJet was able to exert greater control over one of its key business assets: its own data.

What’s more, custom APIs are no longer the sole purview of very large corporations. It’s never been more affordable for small businesses and mid-market organizations to do these types of things, a trend that shows no signs of abating. I’d also argue that these types of considerations have become more essential than ever. Every company is becoming a tech company; some just haven’t realized it yet.

Simon Says: Stasis Is Not an Option

Two years is an eternity today. Organizations that refuse to embrace new tools, data, and ways of doing things run the risk of irrelevance. Far too often, execs focus on the cost of action. It’s high time that they begin grappling with the costs of inaction.

Feedback

What say you?

Originally published on HuffPo.

The post Proprietary APIs: A New Tool in the Age of the Platform appeared first on Phil Simon.

October 23, 2014

Early Thoughts on Google Inbox

In Message Not Received, I rail against e-mail as most people current use—and misuse—it. Among my biggest gripes: It was never designed as a task-management application, although many people use it precisely for that purpose. (I did myself for many years until I saw the light.) And don’t get me started on using it for scheduling appointments. You won’t hear the end of it.

In Message Not Received, I rail against e-mail as most people current use—and misuse—it. Among my biggest gripes: It was never designed as a task-management application, although many people use it precisely for that purpose. (I did myself for many years until I saw the light.) And don’t get me started on using it for scheduling appointments. You won’t hear the end of it.

Why do we check e-mail so compulsively at work, up to 20 times per day? In the book, I explore many reasons of the reasons, including cultural expectations, ease of use, and the ubiquity of the tool. I’d argue that the single biggest reason, though, is that we choose to use e-mail as our de facto to-do list. As such, constantly going to our inboxes makes sense. How else are we going to know what we should be doing and the status of key items?

But what if e-mail could be smarter? What if it could alert you?

That’s the promise behind Google’s radical new email app. In a nutshell, it promises to make e-mail more efficient and proactive. As David Pierce writes on The Verge:

It’s looking for a few things: similar types of emails, which it combines into “Bundles” with names like “Updates” and “Travel,” and bits of information that are obviously the important part of the message. I have a Delta receipt that I’ve been meaning to file in my expenses; Inbox immediately grabbed the PDF and featured it in the stream of my inbox. Attachments are no longer buried below the message, they’re one simple tap away. If you have a confirmation number for a flight, you’ll see the flight’s status. If there’s an address in your email, your inbox or search results give you a Maps link without even needing to open the message.

The app is invite-only at this point and I have dutifully signed up for a test run. (Plus, I like giving early impressions of Google’s wares.) I’m happy to give it a go, although I’m very content using Todoist to manage my tasks.

Other preliminary thoughts:

Should we trust Google with this information? Will with be comfortable with Google effectively telling us what to do and when? Surely Google will use Inbox to serve up even more relevant ads. I can’t fault Larry et. al for trying to make money. After Google is a publicly traded company. But it’s hard to overlook the company’s privacy record.

What if Gmail goes down? What then? Will we forget what to do? How many of us even know our friends’ and relatives’ phone numbers? I sure don’t.

Will ads get downright creepy? It doesn’t take a creative imagination to see this breaking bad. What if “adult” ads appear and your significant other looks over your shoulder?

Simon Says

E-mail has to evolve in order to survive. Not too many tools and tchotchkes succeed by remaining constant, and this goes double in an age of unprecedented, rapid technological change.

Use whatever tools you want. Just understand, though, that if you pay nothing, then you are the product.

Feedback

What say you?

The post Early Thoughts on Google Inbox appeared first on Phil Simon.