Phil Simon's Blog, page 74

August 5, 2014

Big Data: It Depends

How much data do we need?

How much data do we need?

It’s question that I hear quite often, most recently after speaking to 100 chief executives in Atlantic City, NJ. At the end of my 45-minute talk, the CEO of an airplane parts manufacturer wanted to know what all of this “Big Data stuff” ultimately meant for him and his organization. As he asked his question, he explained that he was already able to predict “with about 90 percent accuracy” whether a given part would fail. Would analyzing different data sources really move his organization’s needle? Would the juice be worth the squeeze?

To be sure, these are reasonable queries. I’ll be the first to admit that it’s impossible to answer “How much is enough?” questions like these in a vacuum. As such, I responded with a few questions of my own:

What if you could up your prediction accuracy rate to 99 percent for a relatively small amount of money?

Why would you focus on an abstract number? Isn’t it really important to predict the failure rates of critical engine parts as accurately as possible? For parts in coffee dispensers, though, is the same level of precision required?

Assessing the viability of potential improvements like these are meaningless without context. Economics is fundamentally the study of scarcity and foolish is the pundit, thought leader, speaker, or consultant who answers questions like these in absolute terms. For instance, if Google possessed unlimited funds, then it could buy every startup with a remote chance of success. Despite its immense coffers, even mighty Google has to make choices.

Choices make companies interesting.

And it’s those bets and choices that make companies so interesting. The fact that Google plunked down $3B for Nest indicates that it’s betting heavily on the Internet of Things. Google could have spent that money on something else entirely–or just kept it in the bank. As Mahatma Gandhi famously said, “Actions express priorities.”

Simon Says

Ultimately, does Big Data matter for any given CXO? Which data will ultimately matter? And which will prove a fool’s errand? These are lofty questions with a maddeningly simple yet incomplete answer: It depends.

Does this smack of the traditional consultant’s response a bit? Sure, I’ll cop to that. That doesn’t mean, though, that equivocating here is the wrong move. It’s not. I understand the need for easy answers. When it comes to Big Data, however, they simply don’t exist. Doing it right is far easier said than done.

Feedback

What say you?

This post is brought to you by SAS.

This post is brought to you by SAS.

The post Big Data: It Depends appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 4, 2014

When Dataviz Manifests the Obvious

“Perfect is the enemy of good.”

–Voltaire

Why does Netflix spend so much money on trying to predict what its 50 million subscribers will watch? (The company famously offered a prize to anyone who could improve its recommendation engine.) Why has it devoted so many resources to collaborative filtering?

Why does Netflix spend so much money on trying to predict what its 50 million subscribers will watch? (The company famously offered a prize to anyone who could improve its recommendation engine.) Why has it devoted so many resources to collaborative filtering?

How Netflix generates recommendations is a bit of a black box, but the reason is fairly straight forward: Better predictions mean better business. Let me explain.

Think about the two-year contract that you likely have with AT&T, Verizon, or another wireless carrier. If you don’t like the service, there’s not much that you can do in the immediate future. Breaking your existing contract will be expensive, although T-Mobile will cover the fee. Still, for many folks, the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.

Better does not mean perfect.

Contrast the lock-in business model with that of Netflix. Contract? What contract? You continue paying for as long as you like. If you want to take a few months off, go right ahead sans penalty. Netflix will be there waiting if and when you decide to return. And this is no accident. It’s unlikely that Netflix would have grown as much as fast had it try to lock its customers into multi-year agreements. Reed Hastings and the top brass at Netflix clearly believe that the carrot is a more effective means of garnering customers than the stick. By serving up relevant movies and TV shows, Netflix is betting that its customers will stick around.

Put differently, Netflix is trying to be your friend–or at least not the scourges that most people consider their cable and cell providers to be. Do you think that it’s a coincidence that Netflix blasted Verizon and Comcast on net neutrality?

All of this underscores the importance of timely, relevant, and better predictions. Note that better does not mean perfect. Sometimes Netflix recommends content to me that I find lacking or just plain anodyne. When I stop watching that show after five minutes (and never return), Netflix knows not to recommend similar movies to me in the future.

Simon Says: Keep Expectations in Check

Far too many CXOs justifiably doubt the import of Big Data. Sure, there’s tremendous hype and comparatively little in the way of documented case studies and examples. Ultimately, many ask the bottom-line question: How will this impact my business?

I’ve said many times that it’s critical to manage expectations. Let’s say that you believe that analyzing unstructured data will double your market share or eliminate customer attrition in six months. Good luck with that. Instead, why not take a more measured, conservative approach? Realize that it’s a marathon, not a sprint. If Netflix is still noodling with its recommendation algorithm more than 15 years after its founding, what makes you think that you’ll be able to nail yours in a few months or quarters?

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business but the opinions expressed are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business but the opinions expressed are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

The post When Dataviz Manifests the Obvious appeared first on Phil Simon.

The Folly of the Perfect Prediction

“Perfect is the enemy of good.”

–Voltaire

Why does Netflix spend so much money on trying to predict what its 50 million subscribers will watch? (The company famously offered a prize to anyone who could improve its recommendation engine.) Why has it devoted so many resources to collaborative filtering?

Why does Netflix spend so much money on trying to predict what its 50 million subscribers will watch? (The company famously offered a prize to anyone who could improve its recommendation engine.) Why has it devoted so many resources to collaborative filtering?

How Netflix generates recommendations is a bit of a black box, but the reason is fairly straight forward: Better predictions mean better business. Let me explain.

Think about the two-year contract that you likely have with AT&T, Verizon, or another wireless carrier. If you don’t like the service, there’s not much that you can do in the immediate future. Breaking your existing contract will be expensive, although T-Mobile will cover the fee. Still, for many folks, the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.

Better does not mean perfect.

Contrast the lock-in business model with that of Netflix. Contract? What contract? You continue paying for as long as you like. If you want to take a few months off, go right ahead sans penalty. Netflix will be there waiting if and when you decide to return. And this is no accident. It’s unlikely that Netflix would have grown as much as fast had it try to lock its customers into multi-year agreements. Reed Hastings and the top brass at Netflix clearly believe that the carrot is a more effective means of garnering customers than the stick. By serving up relevant movies and TV shows, Netflix is betting that its customers will stick around.

Put differently, Netflix is trying to be your friend–or at least not the scourges that most people consider their cable and cell providers to be. Do you think that it’s a coincidence that Netflix blasted Verizon and Comcast on net neutrality?

All of this underscores the importance of timely, relevant, and better predictions. Note that better does not mean perfect. Sometimes Netflix recommends content to me that I find lacking or just plain anodyne. When I stop watching that show after five minutes (and never return), Netflix knows not to recommend similar movies to me in the future.

Simon Says: Keep Expectations in Check

Far too many CXOs justifiably doubt the import of Big Data. Sure, there’s tremendous hype and comparatively little in the way of documented case studies and examples. Ultimately, many ask the bottom-line question: How will this impact my business?

I’ve said many times that it’s critical to manage expectations. Let’s say that you believe that analyzing unstructured data will double your market share or eliminate customer attrition in six months. Good luck with that. Instead, why not take a more measure, conservative approach? Realize that it’s a marathon, not a sprint. If Netflix is still noodling with its recommendation algorithm more than 15 years after its founding, what makes you think that you’ll be able to nail yours in a few quarters?

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

The post The Folly of the Perfect Prediction appeared first on Phil Simon.

August 1, 2014

Vote on the Cover of Message Not Received

I’m about 37,000 words into the manuscript for Message Not Received. The research is going very well. I’ve already nailed down a few case studies, but there’s room for one or two more.

I’m about 37,000 words into the manuscript for Message Not Received. The research is going very well. I’ve already nailed down a few case studies, but there’s room for one or two more.

One of my favorite parts of the book-writing process is the development of the cover. For several reasons, it’s a blast. For one, it’s just plain fun to see my ideas become more tangible. I’ll typically throw out a few concepts to Luke Fletcher, my awesome cover guy and, over the course of a 45-minute phone call, we’ll flush them out. A few weeks later, he’ll return with several mockups that reflect the gist of our discussion. We refine them from here.

It doesn’t hurt that Luke and I have a great rapport. Like me, he’s a huge fan of Breaking Bad and The Big Lebowski, although these common interests make it too easy for us to get off track. They were Nazis, dude?

Here are some mockups from Luke:

What do you think?

Vote on our poll!

The post Vote on the Cover of Message Not Received appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 31, 2014

Message Not Received: Sneak Preview

I’ve been quiet on this site for the last few weeks. Aside from refining my golf game, I’ve been cranking away on Message Not Received: How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications.

I’ve been quiet on this site for the last few weeks. Aside from refining my golf game, I’ve been cranking away on Message Not Received: How New Technologies and Simpler Language Can Fix Your Business Communications.

Last night, I cracked 34,000 words in the manuscript. (Golf applause.) I should have cover mockups within a few days. Wiley and I have even moved up the publication date by a few months. I should be holding it in my hands in May of 2015.

Research is going very well. It looks like the book will contain four to five proper case studies and a bunch of other examples and outside perspectives. I’ve come across some fascinating companies that use truly collaborative tools to, you know, actually collaborate. I’m really excited about the stories I’ll be telling. Yes, there is life beyond e-mail.

The structure of the book is pretty solid at this point. I know what kind of house I’m building, I just don’t know how many bathrooms it will contain, where the sofa will go, etc.

Without further ado, here’s the current table of contents.

Preface

Part I: Background and Introduction

Introduction

Chapter 1: Technology Is Eating the World

Part II: Systematic Chaos: Why We Don’t Communicate Good at Work

Chapter 2: What We Say

Chapter 3: How We Say It

Chapter 4: The Effects of Poor Business Communication

Part III: The Solution

Chapter 5: Guidelines for Effective Business Communication

Chapter 6: Awareness, Context, and the Power of Words

Chapter 7: Better Business Communication through New Tools

Coda

By the way, if you have an example of a particularly jargon-filled job description, let me know. I’d love to throw a few more in.

The post Message Not Received: Sneak Preview appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 16, 2014

Past ≈ Future?

Most of us have heard this line–or something similar–more than a few times:

The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior.

As a longtime sports fan, I’ve seen this bromide play out more times than I can recall. One of my favorite examples here concerns baseball. Many statistics like batting average, hits, wins, RBI, walks, and the like almost always resemble a bell curve. That is, absent injury, a strike-shortened season, or other extenuating circumstances, the trajectory of a player’s productivity tends to peak mid-career and then wane as Father Time catches up.

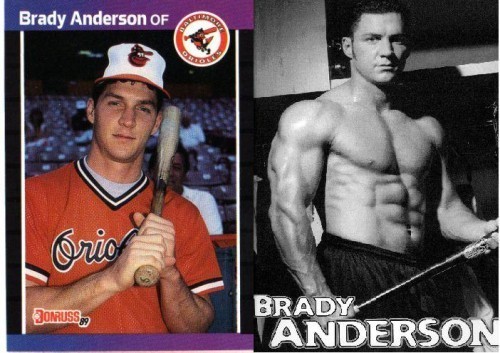

That’s not to say, though, that there haven’t been plenty of notable sports exceptions to the “past ≈ future” rule. For instance, Oriole outfielder Brady Anderson’s home run totals had historically been pretty predicable, give or take. Then, from 1995 to 1996, the number skyrocketed from 16 to 50.

Yes, 50.

Due strictly to chance or skill, an increase of more than 200 percent is completely implausible–that is, at least due to natural events. Of course, Anderson’s productivity boon stemmed from artificial means, so much so that he made the All Steroid Team.

And then there’s Apple. The chart below shows when I, on the advice of ostensibly experienced analysts, bought more than a few shares of the company’s stock:

Click on image to embiggen.

That hurt.

Clearly there’s no direct relationship between past and future performance when it comes to individual stocks. If it were, then investing would be downright easy.

How will Big Data impact the relationship between past and future performance? Put differently, will we be able to read between the lines better?

It’s a lofty and interesting subject, one that Nate Silver addresses in his excellent book The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail �but Some Don’t (affiliate link). Perhaps

Simon Says

The era of Big Data and predictive analytics guarantees nothing. I strongly suspect that Black Swans will continue to exist.

There’s been no shortage of exceptions to the “past ≈ future” rule.

I’ll be the first to admit that this is tough for many people to swallow, but there’s a good chance that predictions continue to miss their marks. I for one believe that many, if not most things, will only completely understood in hindsight. Big Data can certainly help, but I sincerely doubt that we’ll get to the point at which our models can take everything into account. I suspect that the future never completely resemble the past.

Feedback

What say you?

While the words and opinions in this post are my own, Trendensity has compensated me to write it.

While the words and opinions in this post are my own, Trendensity has compensated me to write it.

The post Past ≈ Future? appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 9, 2014

Looking for Examples and Case Studies for My Next Book

My next book will examine technology, language, and business communication. (Read the announcement here.)

My next book will examine technology, language, and business communication. (Read the announcement here.)

Although I have plenty of opinions and thoughts on these topics, I am not just looking inward. As I did with The New Small, Too Big to Ignore, and The Visual Organization, I am reaching outward, In those books, I solicited proper case studies to make them richer. I just think that, if at all possible, that’s the right way to do research and write a business book.

What am I looking for this time? Funny you should ask. Here are a few types of questions to think about:

Do you work with people who rely upon e-mail far too often and/or when it’s not appropriate? Don’t get me wrong. E-mail is critical in many if not most organizations, but there’s certainly a time and place for it. Did something huge fall through the cracks at the last minute because someone erroneously believed that sending an e-mail was sufficient?

Are any of your employees too text- and acronym happy? Has your organization lost deals because prospective clients couldn’t get a timely and appropriate response in plain English from, you know, a human voice?

Could your organization have ever averted a massive problem–or at least minimized it–if the key parties had just taken five minutes to get on a call together?

Have you ever tried to show someone a new way of doing things only to be rebuffed? For instance, have you ever told the guy who sends 30-mb e-mail attachments that it’s not 1998 and there are better ways? (WeTransfer, DropBox, Box.Net, and others.)

Have you come across any employees, consultants, software vendors, thought leaders, and/or management types who routinely use words incorrectly in a vain attempt to sound smart? I’m not talking about people who legitimately make mistakes (e.g., verbiage). Do you work with individuals who believe that they’re effectively explaining technology-related things when they’re only confusing others?

Did you ever leave a job because of the organization’s unwillingness to embrace new applications and tools?

Did your team, department, or organization miss key deadlines because a software salesperson or vendor couldn’t communicate effectively? Did a team suffer because several members’ communication skills weren’t up to snuff?

On the positive side, is your organization using a raft of truly collaborative tools like Asana to manage projects and actually get work done?

I am particularly interested in the effects that poor business communication habits and styles have on others. Does that mean that I need some type of ROI calculation? Of course not. At the same time, though, I’m looking for more than just complaints like “Saul would never talk about our meth business in person; he always wanted to use a secure line.”

FAQ

Here’s a very simple FAQ. Click on the question to expand the answer.

My boss uses jargon repeatedly and no one understands him. I don't want to get fired. Can I contribute anonymously?

Yes. My first book is replete with pseudonyms. I didn’t want to get sued. More important, I respect the confidentiality of my sources.

Does my contribution have to be unnamed?

No.

What do I get in return?

I believe that writing is cathartic. I’ve saved thousands of dollars that I would have spent on shrinks. Beyond that, if your contribution makes it into the book, I’m happy to hook you up with a free physical copy of when it’s published in mid-2015.

OK. How do I get started?

Click here to go to a Google form.

Does filling out that form guarantee that my unedited contribution makes it into the book?

No. Not all rants are book-worthy, much less without an edit.

Thanks and let me know if you uhave any questions.

The post Looking for Examples and Case Studies for My Next Book appeared first on Phil Simon.

Site Tweaks

There’s a world of difference between a simple, static website and a true content management system like WordPress. To me, the former is analogous to a brochure. It’s my firm belief that websites need to evolve, both in terms of substance as well as style.

There’s a world of difference between a simple, static website and a true content management system like WordPress. To me, the former is analogous to a brochure. It’s my firm belief that websites need to evolve, both in terms of substance as well as style.

Against that backdrop, my rock-star developer and I have made some changes to this site over the past week. You might notice a new and (I hope) more palatable set of fonts. I had grown tired of the previous fonts and believe that these new ones increase the overall readability of the site. What’s more, the site now sports a proper logo. There are some other, relatively minor tweaks as well designed to augment consistency. I have a few new toys to play with as well.

I freaking love WordPress.

That’s it. I hope that you like version 3.1 of my site. Let me know if you experience any issues.

The post Site Tweaks appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 8, 2014

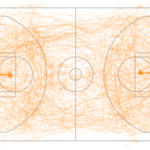

When Dataviz Manifests the Obvious

It’s easy to geek out on data and dataviz these days. One major potential time-suck: Deadspin Regress.

There. You’ve been warned.

Of particular interest to me was this recent data visualization of NBA players’ movement created via SportVU. The tool does a number of things, some of which are more interesting and revealing than others. The Deadspin article manifests how, thanks to SportVU, anyone can visualize where NBA players move on the court during the course of a game.

As the article illustrates, this visualization isn’t terribly insightful. You won’t find five-time NBA champion Tim Duncan of the Spurs hanging out at the 3-point line very often. As a true big man, he tends to play close to the post. (For more on advanced NBA analytics, click here.)

Now, did you need a fancy dataviz tool to tell you that? Perhaps not. Maybe you watch a great deal of basketball and instinctively know that he never takes three-pointers. In his 17-year career, he’s taken well under 200 total threes. Hell, that’s an average month for Warriors’ sharpshooter Steph Curry.

Data visualizations don’t guarantee a thing. Don’t let that stop you from using them.

The point here is that data (Big, Small, or whatever you want to call it) often confirms what we already know. And so do data visualizations. What’s more, as I write in The Visual Organization, “The notion that a dataviz–no matter how good–guarantees a new insight or successful outcome is simply ludicrous.”

Simon Says

The explosion of data and democratization of tools with which to analyze them are mixed blessings. Yes, there’s a signal in that noise, but often Big Data scares and overwhelms many of us. It’s easy to drown in the data deluge. I understand all too well the desire to shut down, to ignore potentially new sources of data–and ways to analyze it.

Fight the urge to flight. Don’t let the fact that useless nature of many data visualizations prevent you from asking important questions. Plus, even if nine of ten assumptions are confirmed, what happens when the tenth is proven incorrect? What if that new insight shakes the foundation of your new marketing campaign or even business model?

Feedback

What say you?

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was brought to you by IBM for Midsize Business and opinions are my own. To read more on this topic, visit IBM’s Midsize Insider. Dedicated to providing businesses with expertise, solutions, and tools that are specific to small and midsized companies, the Midsize Business program provides businesses with the materials and knowledge they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

The post When Dataviz Manifests the Obvious appeared first on Phil Simon.

July 3, 2014

The Skinny on My Seventh Book

For a long time now, I’ve observed many people struggling with business communications. (Truth be told, I wasn’t exactly great at it coming out of grad school.) As my career has moved towards technology and data, I have noticed that this problem is becoming even more acute. The inability to effectively speak and write effectively results in all sorts of inefficiencies, misunderstandings, gaffes, squabbles, and missed opportunities. And this goes double when it comes to technology-related matters.

For a long time now, I’ve observed many people struggling with business communications. (Truth be told, I wasn’t exactly great at it coming out of grad school.) As my career has moved towards technology and data, I have noticed that this problem is becoming even more acute. The inability to effectively speak and write effectively results in all sorts of inefficiencies, misunderstandings, gaffes, squabbles, and missed opportunities. And this goes double when it comes to technology-related matters.

I’ve addressed on this site more than a few times the penchant of many to use buzzwords and jargon when plain English would suffice just fine. Far too many people think that they’re being clever or clear when they drop ostensibly sophisticated terms and bastardize others. (Incent is not a word.) Beyond that, they turn nouns into verbs. In reality, they’re only bloviating. (Use case and price point are real pets peeve of mine.) They fail to consider the context of what they’re saying. They ignore their audiences. They “talk without speaking.”

So what?

You may not think that none of this is a big deal. Many of us do it, right? For several reasons, I’d argue the opposite. First, the need for clear, concise, and context-appropriate communication has never been more pronounced. Employees are inundated with messages throughout the day, many of which arrive via confusing or inscrutable e-mails. Why? Often simple, clear, and honest in-person conversation is almost always preferable, more effective, and faster than a chain of pointless e-mails.

Second, you also may believe that new times have always required new words. On this, I would agree, but only to a certain extent. The verb “to google” developed organically. People understood what it meant. But what about horrible and contrived terms like Big Data Platforms as a Service or even a Next Generation Big Data Platform as a Service? Shouldn’t these words accurately explain an important concept?

Bad Communication Is Bad Business

Forget for a moment any one vendor’s poorly-worded press release. The larger question is whether emerging technology trends really require an entirely new and confusing vocabulary. In short, no. At a high level, I can explain Big Data to a teenager without getting all technical. In fact, I have on several occasions.

The proliferation of faux and contrived terms just plain rankles me. Now, I’ll be the first to admit that I can be a bit persnickety when it comes to language. That aside for a moment, I just don’t think that bad communication is good business. Let me explain.

In the mid-1990s, chief executives who bought ERP, CRM, or BI software knew exactly what they were buying. Despite that, as I wrote in Why New Systems Fail, those projects still suffered from deplorable batting averages. But what happens when CXOs don’t understand what they’re buying? In the case of Big Data or another newfangled “solutions”, I’d argue that confusing marketing coupled with a relative dearth of client understanding are inhibiting the adoption of truly important technologies like Hadoop.

Many people need to reexamine not only what they say, but how they say it.

Truth be told, not everyone can be Dale Carnegie. Many of us take software salespeople, management consultants, techies, and CXOs with a 50-lb. bags of salt. We don’t expect them to speak in a straightforward manner. But the downsides can be significant. For instance, it’s impossibly to carry out a strategy when employees don’t understand it. Exhibit A: The Ballmer One Microsoft Memo:

Today’s announcement will enable us to execute even better on our strategy to deliver a family of devices and services that best empower people for the activities they value most and the enterprise extensions and services that are most valuable to business.

Huh?

If technology were a fleeting trend, then perhaps we could excuse bad communication. We can’t. Technology and data are permeating every instance of our lives–and not just in the workplace. The Internet of Things is coming–and fast. Every company is becoming a tech company; some of them just don’t know it yet.

Against that backdrop, at a high level, my next book will examine technology and how we communicate. I’m still playing around with titles and subtitles. Once again, Wiley will be publishing it and the expected release date is summer of 2015.

Brass tacks: It’s my firm belief that many of us need to reexamine not only what we say, but how we say it.

The post The Skinny on My Seventh Book appeared first on Phil Simon.