Oxford University Press's Blog, page 985

January 21, 2013

Depression in old age

Depression in old age occurs frequently, places a severe burden on patients and relatives, and increases the utilization of medical services and health care costs. Although the association between age and depression has received considerable attention, very little is known about the incidence of depression among those 75 years of age and older. Studies that treat the group 65+ as one entity are often heavily weighted towards the age group 65-75. Therefore, the prediction of depression in the very old is uncertain, since many community-based studies lack adequate samples over the age of 75.

With the demographic change in the forthcoming decades, more emphasis should be put on epidemiological studies of the older old, since in many countries the increase in this age group will be particularly high. To study the older old is also important, since some crucial risk factors such as bereavement, social isolation, somatic diseases, and functional impairment become more common with increasing age. These factors may exert different effects in the younger old compared to the older old. Knowledge of risk factors is a prerequisite to designing tailored interventions, either to tackle the factors themselves or to define high-risk groups, since depression is treatable in most cases.

With the demographic change in the forthcoming decades, more emphasis should be put on epidemiological studies of the older old, since in many countries the increase in this age group will be particularly high. To study the older old is also important, since some crucial risk factors such as bereavement, social isolation, somatic diseases, and functional impairment become more common with increasing age. These factors may exert different effects in the younger old compared to the older old. Knowledge of risk factors is a prerequisite to designing tailored interventions, either to tackle the factors themselves or to define high-risk groups, since depression is treatable in most cases.

In our recent study, over 3,000 patients recruited by GPs in Germany were assessed by means of structured clinical interviews conducted by trained physicians and psychologists during visits to the participants’ homes. Inclusion criteria for GP patients were an age of 75 years and over, the absence of dementia in the GP’s view, and at least one contact with the GP within the last 12 months. The two follow-up examinations were done, on average, one and a half and then three years after the initial interview.

Depressive symptoms were ascertained using the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). We found that the risk for incident depression was significantly higher for subjects

85 years and older

with mobility impairment and vision impairment

with mild cognitive impairment and subjective memory impairment

who were current smokers.

It revealed that the incidence of late-life depression in Germany and other industrialized countries is substantial, and neither educational level, marital status, living situation nor presence of chronic diseases contributed to the incidence of depression. Impairments of mobility and vision are much more likely to cause incidents of depression than individual somatic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus and coronary heart disease. As such, it is vital that more attention is paid to the oldest old, functional impairment, cognitive impairment, and smoking, when designing depression prevention programs.

GP practices offers ample opportunity to treat mental health problems such as depression occurring in relation to physical disability. If functional impairment causes greater likelihood of depression, GPs should focus on encouraging older patients to maintain physical health, whether by changing in personal health habits, advocating exercise, correcting or compensating functional deficits by means of medical and surgical treatments, or encouraging use of walking aids. Additionally, cognitive and memory training could prevent the onset of depressive symptoms, as could smoking cessation. If these steps are taken, the burden of old age depression could be significantly reduced.

Siegfried Weyerer is professor of epidemiology at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany. He has conducted several national and international studies on the epidemiology of dementia, depression and substance use disorders at different care levels. He is also an expert in health/nursing services research. He is one of the authors of the paper ‘Incidence and predictors of depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and older: results from a 3-year follow-up study’, which appears in the journal Age and Ageing. You can read the paper in full here.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Grief. Photo by Anne de Haas, iStockPhoto.

The post Depression in old age appeared first on OUPblog.

January 20, 2013

John Ruskin’s childhood home

Praeterita, John Ruskin’s incomplete autobiography, was written between periods of serious mental illness at the end of his career, and is an eloquent analysis of the guiding powers of his life, both public and private. An elegy for lost places and people, it recounts Ruskin’s intense childhood, his time as an undergraduate at Oxford, and his journeys across France, the Alps, and northern Italy. Attentive to the human or divine meaning of everything around him, Praeterita is an astonishing account of revelation. In the following excerpt, Ruskin remembers his childhood home.

When I was about four years old my father found himself able to buy the lease of a house on Herne Hill, a rustic eminence four miles south of the ‘Standard in Cornhill’; of which the leafy seclusion remains, in all essential points of character, unchanged to this day: certain Gothic splendours, lately indulged in by our wealthier neighbours, being the only serious innovations; and these are so graciously concealed by the fine trees of their grounds, that the passing viator remains unappalled by them; and I can still walk up and down the piece of road between the Fox tavern and the Herne Hill station, imagining myself four years old.

Our house was the northernmost of a group which stand accurately on the top or dome of the hill, where the ground is for a small space level, as the snows are, (I understand,) on the dome of Mont Blanc; presently falling, however, in what may be, in the London clay formation, considered a precipitous slope, to our valley of Chamouni (or of Dulwich) on the east; and with a softer descent into Cold Harbour-lane on the west: on the south, no less beautifully declining to the dale of the Effra, (doubtless shortened from Effrena, signifying the ‘Unbridled’ river; recently, I regret to say, bricked over for the convenience of Mr Biffin, chemist, and others); while on the north, prolonged indeed with slight depression some half mile or so, and receiving, in the parish of Lambeth, the chivalric title of ‘Champion Hill,’ it plunges down at last to efface itself in the plains of Peckham, and the rural barbarism of Goose Green.

Our house was the northernmost of a group which stand accurately on the top or dome of the hill, where the ground is for a small space level, as the snows are, (I understand,) on the dome of Mont Blanc; presently falling, however, in what may be, in the London clay formation, considered a precipitous slope, to our valley of Chamouni (or of Dulwich) on the east; and with a softer descent into Cold Harbour-lane on the west: on the south, no less beautifully declining to the dale of the Effra, (doubtless shortened from Effrena, signifying the ‘Unbridled’ river; recently, I regret to say, bricked over for the convenience of Mr Biffin, chemist, and others); while on the north, prolonged indeed with slight depression some half mile or so, and receiving, in the parish of Lambeth, the chivalric title of ‘Champion Hill,’ it plunges down at last to efface itself in the plains of Peckham, and the rural barbarism of Goose Green.

The group, of which our house was the quarter, consisted of two precisely similar partner-couples of houses, gardens and all to match; still the two highest blocks of buildings seen from Norwood on the crest of the ridge; so that the house itself, three-storied, with garrets above, commanded, in those comparatively smokeless days, a very notable view from its garret windows, of the Norwood hills on one side, and the winter sunrise over them; and of the valley of the Thames on the other, with Windsor telescopically clear in the distance, and Harrow, conspicuous always in fine weather to open vision against the summer sunset. It had front and back garden in sufficient proportion to its size; the front, richly set with old evergreens, and well-grown lilac and laburnum; the back, seventy yards long by twenty wide, renowned over all the hill for its pears and apples, which had been chosen with extreme care by our predecessor, (shame on me to forget the name of a man to whom I owe so much!) — and possessing also a strong old mulberry tree, a tall whiteheart cherry tree, a black Kentish one, and an almost unbroken hedge, all round, of alternate gooseberry and currant bush; decked, in due season, (for the ground was wholly benefi cent,) with magical splendor of abundant fruit: fresh green, soft amber, and rough-bristled crimson bending the spinous branches; clustered pearl and pendant ruby joyfully discoverable under the large leaves that looked like vine.

The differences of primal importance which I observed between the nature of this garden, and that of Eden, as I had imagined it, were, that, in this one, all the fruit was forbidden; and there were no companionable beasts: in other respects the little domain answered every purpose of Paradise to me; and the climate, in that cycle of our years, allowed me to pass most of my life in it. My mother never gave me more to learn than she knew I could easily get learnt, if I set myself honestly to work, by twelve o’clock. She never allowed anything to disturb me when my task was set; if it was not said rightly by twelve o’clock, I was kept in till I knew it, and in general, even when Latin Grammar came to supplement the Psalms, I was my own master for at least an hour before half-past one dinner, and for the rest of the afternoon.

My mother, herself finding her chief personal pleasure in her flowers, was often planting or pruning beside me, at least if I chose to stay beside her. I never thought of doing anything behind her back which I would not have done before her face; and her presence was therefore no restraint to me; but, also, no particular pleasure, for, from having always been left so much alone, I had generally my own little affairs to see after; and, on the whole, by the time I was seven years old, was already getting too independent, mentally, even of my father and mother; and, having nobody else to be dependent upon, began to lead a very small, perky, contented, conceited, Cock-Robinson-Crusoe sort of life, in the central point which it appeared to me, (as it must naturally appear to geometrical animals,) that I occupied in the universe.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: John Ruskin, 1879 by unknown (Hubert von Herkomer?) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post John Ruskin’s childhood home appeared first on OUPblog.

January 19, 2013

Chaucer in the House of Fame

By the time Geoffrey Chaucer died in 1400, he had been living for almost a year in obscurity in a house in the precincts of Westminster Abbey, and on his death he was buried in a modest grave in the church’s south transept. The poet’s last few months had not been his happiest. At the close of a decade in which he had gradually retired from the various administrative offices he had occupied under Edward III and Richard II, Richard’s deposition by Henry Bolingbroke in September 1399 had turned Chaucer’s world upside down. The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse, which was directed to the new king, makes it clear that his fortunes, which had been in the ascendant for much of Richard’s reign, could not now be much worse:

Ye [i.e. the purse] by my lyf, ye be myn hertes stere. life, star

Quene of comfort and of good companye,

Beth hevy ageyn, or elles moot I dye. be, must, die

This story takes a happy twist, though, in the years immediately after Chaucer’s burial. A new incarnation of the poet found himself in luxurious circumstances, as likenesses of Chaucer began to pop up in the margins and on the frontispieces of increasingly sumptuous manuscript copies of his own works (especially of the Canterbury Tales and Troilus and Criseyde), and even, as a tutelary and authorizing presence, alongside the works of his friend and disciple, Thomas Hoccleve.

By 1476 Chaucer’s reputation was such that the first printed book in English, issued by William Caxton from his new printing press at Westminster was the first edition of the Canterbury Tales. In 1556, the antiquary Nicholas Brigham paid for the erection of a new tomb for the poet in the Abbey, to which Chaucer’s bones were translated, an honour which before the Reformation would have only been accorded to a saint (the perceived anti-monasticism in the poet’s works made the Catholic poet surprisingly popular with Protestant reformers). In 1599, the burial nearby of another devoted Chaucerian, Edmund Spenser began the cluster of literary memorials in Westminster Abbey now known as Poets’ Corner.

As I’m writing this on the ‘tenthe day now of Decembre’, the date on which Chaucer chose to set the framing narrative of his poem The House of Fame, it seems like a good time to ask what Chaucer did to ensure that, when most other medieval English writers’ work was fading (or even being ignominiously thrust) into obscurity in the Renaissance, his name and fame lived on.

House guest

Never, sith that I was born since

Ne no man elles me beforn, else, before

Mette, I trow stedfastly, dreamed, believe

So wonderful a drem as I

The tenthe day now of Decembre,

The which as I kan now remembre,

I wol yow tellen everydel. every bit

With this impressive boast, the main action of The House of Fame is introduced. The promise to tell his audience everydel of what he claimed to have dreamt was not made good: the poem is unfinished, and breaks off enigmatically after just over 2,000 lines of fantastical action.

After a first book in which the dreamer finds himself in a glass temple to the goddess Venus, he is carried by a talking eagle to the house of the title: a castle or peel constructed entirely of beryl, and set on top of a rock of ice ‘Betwixen hevene, erthe, and see’, where all the talk of the world comes together. There he sees a grotesque goddess arbitrarily dispensing good and bad fame (or total obscurity) to her petitioners, irrespective of their merits and achievements. When asked if he too has come here to have fame, the dreamer is unequivocal in his denial:

I cam noght hyder, graunt mercy, not, hither

For no such cause, by my hed!

Sufficeth me, as I were ded,

That no wight have my name honde. . . man

For what I drye, or what I thynke, feel

I wil myselven al hyt drynke. all it drink

Naming games

In one respect, Chaucer was as good as his dreamer’s word. Only twice in all his works is the poet referred to by name: once as ‘Geffrey’ by the eagle in The House of Fame, and once as ‘Chaucer’, by the Man of Law in The Canterbury Tales. This should not, perhaps, be surprising; writers don’t often refer to themselves within their work, except as a poetic ‘I’. If they did, we’d probably know the names of more of the medieval writers whose works were transmitted in manuscript form, in an age before the title page was invented.

Chaucer, however, is different: perhaps we expect him to name himself more, because he inserts such a vividly fictionalized version of himself (bumbling and tongue-tied, always apparently self-effacing, and ready to be shocked by the lewdness of what goes on around him) into most of his works.

Yet we not only do ‘have his name in hand’ more than 600 years after his death, we can attach that name not to a single work or manuscript, but to an established canon of ‘complete works’ that has remained largely stable for most of that time. Chaucer may make only fleeting reference to his own name, but he is less reticent about the titles of his works.

One of the reasons that the core canon of Chaucer’s works has remained unchanged for so long, but for a few mistaken attributions and deliberate frauds, is that three separate lists of his writings are embedded within them. The fullest and most important of these, in the ‘Retractions’ at the end of the Canterbury Tales, takes the form of a request for divine forgiveness for his profane writings, and for the prayers of his audience in acknowledgement of his sacred and moral works:

I biseke yow mekely, for the mercy of God, that ye preye for me that Crist have mercy on me and foryeve me my giltes, and namely of my translacions and enditynges of worldly vanitees, the whiche I revoke in my retracciouns, as is the book of Troilus, the book also of Fame. . . the tales of Caunterbury. . . and many another book, if they were in my remembrance, and many a song and many a leccherous lay.

While the pious sentiments seem genuine enough, it’s hard not to see this list, along with the others, as part of the same urge to list and claim a body of work, each time adding to and polishing the table of his achievements, and allowing it to shine more brightly by placing it against the portrait of the barely competent innocent-at-large who narrates most of his poems.

As well as listing his works in this unusual way, Chaucer takes great care to associate his name with the works of the classical poets. The famous apostrophe at the close of Troilus and Criseyde maintains an appearance of modesty, while asserting the right of his poem (the earliest to be described as a tragedy in English) to keep company with the works of the great authors of antiquity:

Go, litel bok, go, litel myn tragedye, book

. . . But litel book, no makyng thow n’envie, literary work, [do] not envy

But subgit be to alle poesye; subject

And kis the steppes where as thow seest pace see

Virgile, Ovide, Omer, Lucan, and Stace. Homer, Statius

A similar, slightly expanded version of this list of classical writers occurs in The House of Fame itself, where the right of the vernacular poet to take his place alongside his Latin predecessors is strongly hinted at in the paraphrase of Virgil’s Aeneid that takes up much of the first book, and in the dreamer’s repeated assertions that his experiences outstrip those of the most famous visionaries not only of classical literary tradition, but also of the Bible.

In claiming for himself this specifically literary version of Fame, Chaucer seems to come close to humanist ideas about authorship embodied in the works of the Italian writers of the fourteenth century. While Chaucer was certainly not the first English writer to use the work of the classical poets – throughout the Middle Ages, the pagan Latin authors remained an important part of the academic curriculum, and their stories and ideas were frequently recycled – he was one of the first to interact with, and borrow from, the work of the Italian poets Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio.

Chaucer names the first two of this poetic triumvirate frequently in his works, acknowledging his debt to them for individual tales, allowing Petrarch his status as laureat poete, and describing Dante as ‘the grete poete of Ytaille’. However, he never mentions Boccaccio by name, although he relies heavily on his Italian near-contemporary’s work in two major works, The Knight’s Tale andTroilus and Criseyde, and may even have met him in Florence on a diplomatic mission in 1372. In the case of Troilus, Chaucer goes so far as to invent a spurious classical authority — ‘Lollius’ — as his source. It is as if, having aligned himself with the greatest authors of the past, Chaucer had found a source of poetic inspiration that was practically unknown to his audience, and that he wanted to keep it (and a greater share of the available fame) to himself.

Something else that he may have learned (or caught) from these Italian poets also helped Chaucer helped to align his work with the coming mainstream of European literature, prefiguring the concerns of English Renaissance poets, and ensuring his own continued relevance: his enthusiasm for classical mythology and legend.

Gods and Monsters

This interaction with the classical past was not in itself new in medieval English literature. The story of Troy, its destruction, and the wanderings of its survivors, was particularly popular in England, through the legend that traced the foundation of Britain back to the Trojan Brutus. Chaucer may not have been the first to reuse and recycle this classical material, but he was the first to do so consistently, and with such obvious delight in the details and machinery of Latin and Greek myth and legend.

Chaucer’s Thebes and Troy – in common with most medieval depictions of the classical past — may be barely distinguishable in social or material terms from fourteenth-century London and the court of Richard II, but the landscape and universe in which they are set are peopled with creatures and deities alien to earlier English writing. In fact it is in Chaucer that many of the creatures of classical mythology make their first appearance in English. When Criseyde swears her love to Troilus:

On every god celestial. . .

On every nymphe and deite infernal, nymph, deity

On satiry and fawny more and lesse, satyrs, fauns

That halve goddes ben of wildernesse. demigods

Each of these halve goddes seem to be new arrivals in English. Elsewhere, he finds it necessary to import the word monstre from French in order to classify the centaurs, harpies, and the three-headed dog Cerberus encountered by Hercules in his labours, which are recounted (albeit in brief) for the first time in English literature in The Monk’s Tale.

While it seems that theatrical and social ‘personalities’ first came to be called stars in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, it is fitting that the first recorded user of the word ‘celebrity’, and one of the first to use ‘famous’ in English should also provide our first evidence for the word starry, and that the dreamer in The House of Fame should be worried that he might be ‘stellified’ and placed among the stars of the ‘Galaxie, Which men clepeth the Milky Way’ (another two examples of first recorded use) when the eagle carries him aloft. Would the poet himself have been so alarmed at the prospect of being made a star? Somehow, I doubt it.

This article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Jonathan Dent is a researcher on the OED, and begs—like Chaucer—that if there is anything in this blog that displeases you, that you ascribe it to the fault of his unknowing, and not to his will, which would gladly have written better if he had the knowledge.

Oxford Dictionaries Online is a free site offering a comprehensive current English dictionary, grammar guidance, puzzles and games, and a language blog; as well as up-to-date bilingual dictionaries in French, German, Italian, and Spanish. We also have a premium site, Oxford Dictionaries Pro, which features smart-linked dictionaries and thesauruses, audio pronunciations, example sentences, advanced search functionality, and specialist language resources for writers and editors.

Subscribe to the OxfordWords blog via RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Chaucer in the House of Fame appeared first on OUPblog.

January 18, 2013

Jason Steinhauer, the Kluge Center, and opportunities for oral historians

In our second blog post of 2013, I, Troy Reeves, Managing Editor, have taken over, while our social media coordinator and blog contributor Caitlin Tyler-Richards get some well deserved time away from the office. This guarantees the reader of two things: (1) This post will be wordy, nearing on inscrutable; and (2) far less funny.

In our second blog post of 2013, I, Troy Reeves, Managing Editor, have taken over, while our social media coordinator and blog contributor Caitlin Tyler-Richards get some well deserved time away from the office. This guarantees the reader of two things: (1) This post will be wordy, nearing on inscrutable; and (2) far less funny.

This week, I speak with Jason Steinhauer, program specialist in the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress (LOC). According to Jason, “the Kluge Center brings together scholars and researchers from around the world to stimulate and energize one another, to distill wisdom from the Library’s rich resources, and to interact with policymakers and the public.” In this podcast, Jason and I talk about the Kluge Center’s opportunities for oral historians, and his strongest memories from his two-plus years working at the LOC’s Veterans History Project. I also overcome the urge to ask him to sing a piece from his band, The Grey Area. Next time, people, I promise.

[See post to listen to audio]

Or download the podcast directly.

Jason Steinhauer currently serves as program specialist for The John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. Prior to joining the Kluge Center, Jason served as a liaison specialist for the Library’s Veterans History Project, working with volunteer interviewers nationwide to build the country’s largest oral history project. An award-winning curator and oral historian, Jason’s exhibition credits include Lincoln and New York at the New-York Historical Society, New York City of Refuge Stories from the Last 60 Years at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, and Ours to Fight For: American Jews in the Second World War, winner of the Grand Prize for Excellence in Exhibitions from the American Alliance of Museums. When not advocating for oral history and scholarship, he is the frontman for the indie rock group The Grey Area. Chat with him about the Library of Congress, oral history, and leadership on Twitter (@JasonSteinhauer), or message him on LinkedIn.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image used with permission of Jason Steinhauer. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Jason Steinhauer, the Kluge Center, and opportunities for oral historians appeared first on OUPblog.

Bill McGuire on the geological consequences of climate change

Could it be that we are on track to bequeath to our children and their children not only a far hotter world, but also a more geologically fractious one? Already there are signs that the effects of climbing global temperatures are causing the sleeping giant to stir once again.

Below, you can listen to Bill McGuire talk about the topics raised in his book Waking the Giant: How a changing climate triggers earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes. This podcast is recorded by the Oxfordshire Branch of the British Science Association who produce regular Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Listen to podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Or you can download it directly from Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Bill McGuire is an academic, science writer, and broadcaster. He is currently Professor of Geophysical and Climate Hazards at UCL. Bill was a member of the UK Government Natural Hazard Working Group established in January 2005, in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami, and in 2010 a member of the Science Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE) addressing the Icelandic volcanic ash problem. He was also a contributing author on the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) report on extreme events. His books include Waking the Giant: How a changing climate triggers earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes, Surviving Armageddon: Solutions for a Threatened Planet, and Seven Years to Save the Planet. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Bill McGuire on the geological consequences of climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

Thought Control

As a teacher I have sometimes offered a million pounds to any student who can form any one of the following beliefs: that they can fly; that they were born on the moon; or that sheep are carnivorous. Needless to say, I have never had to pay up. The Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass might have been able to believe six impossible things before breakfast, but that is a feat few of us can match. In fact, it is doubtful whether the formation of belief is under voluntary control at all. Adopting a belief seems to be more like digesting or metabolizing and rather unlike looking or speaking—it seems to be something that happens to one rather than something that one does.

But unlike digestion or metabolizing, the upshot of belief-formation has a direct impact on how we behave. Although we don’t always act in accordance with our beliefs, it goes without saying that what we believe plays a huge role in governing what we do. More importantly, a rational person ought to act on the basis of their beliefs; indeed, failing to act in light of one’s beliefs is a form of irrationality.

In and of themselves the two claims that we have just examined—that belief-formation is involuntary and that a person’s beliefs justify their actions—are unobjectionable. Trouble looms, however, when we put them together. From Francisco Pizarro to Tomás de Torquemada, and from Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to Anders Breivik, history is littered with the carnage wrought by the actions of sincere but misguided individuals—people who have regarded the superiority of their religion, race or ideology as legitimizing actions that we regard as horrific.

In and of themselves the two claims that we have just examined—that belief-formation is involuntary and that a person’s beliefs justify their actions—are unobjectionable. Trouble looms, however, when we put them together. From Francisco Pizarro to Tomás de Torquemada, and from Khalid Sheikh Mohammed to Anders Breivik, history is littered with the carnage wrought by the actions of sincere but misguided individuals—people who have regarded the superiority of their religion, race or ideology as legitimizing actions that we regard as horrific.

How should we regard such individuals? If the formation of belief is involuntary, then, one might think, we cannot justifiably condemn them for holding the beliefs that motivated their actions. Can we condemn them for acting on those beliefs? Arguably not, for how else is a person to act if not on the basis of their beliefs? But if we cannot condemn them either for forming their beliefs or for acting in light of their beliefs, what grounds do we have for condemning them at all?

Some might be tempted to respond that we don’t have any grounds for condemning such individuals, and that those who act on the basis of their sincerely held beliefs shouldn’t be denounced for what they do, no matter how awful their deeds. We could, of course, continue to regard such agents as legally responsible for their crimes, but—according to this line of thought—we have no grounds for holding them morally guilty for the actions that they carry out in light of their convictions.

Although some might be happy to settle for this solution, I suspect that for many of us it is a response of last resort—a position to be adopted only when all other avenues are exhausted. Are there any other avenues available to us?

Perhaps we were too quick to embrace the idea that belief-formation is always involuntary. Although it is clear that we cannot simply decide to adopt any old proposition that is put to us, it doesn’t follow—and it may not be true—that we have no intentional control over what we believe. For example, it is surely plausible to suppose that we have some control over whether or not to subject our beliefs to critical scrutiny. One can deliberate about whether or not to believe those propositions that are open questions for one. And if deliberation lies within one’s voluntary control, then perhaps one can be justifiably blamed for failing to deliberate appropriately.

Perhaps so, but does this solve our puzzle? I suspect not. For one thing, I very much doubt whether the beliefs that motivated Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Anders Breivik were ‘open questions’ from their point of view. Instead, I suspect that they regarded them as self-evident truths, claims no more deserving of critical scrutiny than the belief that 2+2=4 or the belief that there is water at the bottom of the ocean. Moreover, even if they were guilty of failing to subject their beliefs to the kind of scrutiny that they should have, that failing would surely be relatively minor rather than an instance of gross moral turpitude of the kind for which we are inclined to hold them guilty.

So, how should we resolve this puzzle? I don’t have a full solution to offer, but here is one line of thought that I find tempting. Although belief-formation is responsive to evidence, it is also influenced by desire and motivation: how we take the world to be is heavily influenced by how we would like the world to be. And one of the central sources of belief in the superiority of one’s religion, race or ideology is surely the desire to dominate one’s fellow human beings.

And here, perhaps, we can see the hint of a solution to our puzzle. What the Khalid Sheikh Mohammeds and Anders Breiviks of this world are guilty of is not the fact that they have voluntarily adopted unjustified beliefs, for we have seen that it is doubtful whether their beliefs were voluntarily acquired. Rather, their guilt lies in the character traits that their beliefs manifest. Our condemnation of them is justified insofar as the beliefs that motivated their actions were grounded in intolerance, arrogance and self-aggrandizement.

Tim Bayne is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Manchester. He has taught at the University of Canterbury, Macquarie University, and the University of Oxford. His main interests are in the philosophy of psychology, with a particular focus on consciousness. A native of New Zealand, he divides his time between Manchester and Geneva. His is the author of Thought: A Very Short Introduction .

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, upon capture. Taken by U.S. forces when KSM was captured [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Thought Control appeared first on OUPblog.

January 17, 2013

C is for Coloratura

Marilyn Horne, world-renowned opera singer and recitalist, celebrated her 84th birthday on Wednesday. To acknowledge her work, not only as one of the finest singers in the world but as a mentor for young artists, I give you one of my favorite performances of hers:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sesame Street has always been a powerful advocate for utilizing music in teaching. “C is for Cookie,” a number that really drives its message home, maintains its cultural relevance today despite being first performed by Cookie Monster more than 40 years ago. Ms. Horne’s version appeared about 20 years after the original, and is an excellent re-imagining of a classic (with great attention to detail—note the cookies sewn into her Aida regalia and covering the pyramids).

Horne’s performance shows kids that even a musician of the highest caliber can 1) be silly and 2) also like cookies—that is, it portrays her as a person with something in common with a young, broad audience. This is something that members of the classical music community often have a difficult time accomplishing; Horne achieves it here in less than three minutes.

Fortunately, many professional classical musicians have embraced this strategy. Representatives of the opera world (which is not known for being particularly self-aware) have had a particularly strong presence on Sesame Street, with past episodes featuring Plácido Domingo (singing with his counterpart, Placido Flamingo), Samuel Ramey (extolling the virtues of the letter “L”), Denyce Graves (explaining operatic excess to Elmo), and Renée Fleming (counting to five, “Caro nome” style).

Sesame Street produced these segments not only to expose children to distinguished music-making, but to teach them about matters like counting, spelling, working together, and respecting one another. This final clip features Itzhak Perlman, one of the world’s great violin soloists, who was left permanently disabled after having polio as a child. To demonstrate ability and disability more gracefully than this would be, I think, impossible:

Click here to view the embedded video.

American children’s music, as described in the new article on Grove Music Online [subscription required], has typically been produced through a tug of war between entertainment and educational objectives. The songs on Sesame Street succeed in both, while also showing kids something about classical music itself: it’s not just for grownups. It’s a part of life that belongs to everyone. After all, who doesn’t appreciate that the moon sometimes looks like a “C”? (Though, of course, you can’t eat that, so…)

Jessica Barbour is the Associate Editor for Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. You can read her previous blog posts, “Foil thy Foes with Joy,” “Glissandos and Glissandon’ts,” and “Wedding Music” and learn more about children’s music, Marilyn Horne, Itzhak Perlman, and other performers mentioned above with a subscription to Grove Music Online.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post C is for Coloratura appeared first on OUPblog.

Five facts about the esophagus

The Mayo Clinic Scientific Press suite of publications is now available on Oxford Medicine Online. To highlight some of the great resources, we’ve pulled together some interesting facts about the esphophagus from Stephen Hauser’s Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review.

(1) The esophagus has two major functions: to propel food boluses downward to the stomach and to keep stomach contents from refluxing upward. The esophagus accomplishes these functions by its tubular anatomy and motility that involves the contraction and relaxation of sphincter muscles and precisely timed peristaltic waves.

(2) The initial process of swallowing is under voluntary control. A swallow is initiated by the lips closing, the teeth clenching, and the tongue being elevated against the palate, forcing the bolus to the pharynx. Entry of the bolus into the pharynx triggers the involuntary swallowing reflex.

(3) Oropharyngeal dysphagia is often characterized by the complaint of difficulty initiating a swallow, transitioning the food bolus or liquid into the esophagus, meal-induced coughing or “choking,” or of food “getting stuck” in the voluntary phase of swallowing.

(4) Patients with an esophageal body or LES disorder describe “esophageal dysphagia” characterized by the onset of symptoms moments after the initiation of a swallow. They usually can sense that the food or liquid bolus has traversed the oral cavity and has entered the esophagus. They complain of food feeling “stuck” or “hung up” in transition to the stomach.

(5) Gastroesophageal reflux is the reflux of gastric contents other than air into or through the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) refers to reflux that produces frequent symptoms or results in damage to the esophageal mucosa or contiguous organs of the upper aerodigestive system and occasionally the lower respiratory tract.

Gastroenterology and hepatology encompass a vast anatomical assortment of organs that have diverse structure and function and potentially are afflicted by a multiplicity of disease processes. Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review is designed to assist both physicians in-training who are preparing for the gastroenterology board examination and the increasing number of gastroenterologists awaiting recertification.

The Mayo Clinic Scientific Press suite of publications is now available on Oxford Medicine Online. With full-text titles from Mayo Clinic clinicians and a bank of 3,000 multiple-choice questions, Mayo Clinic Toolkit provides a single location for residents, fellows, and practicing clinicians to undertake the self-testing necessary to prepare for, and pass, the Boards and remain up-to-date. Oxford Medicine Online is an interconnected collection of over 250 online medical resources which cover every stage in a medical career, for medical students and junior doctors, to resources for senior doctors and consultants. Oxford Medicine Online has relaunched with a brand new look and feel and enhanced functionality. Our aim is to ensure that the site continues to deliver the highest quality Oxford content whilst meeting the requirements of the busy student, doctor, or health professional working in a digital world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five facts about the esophagus appeared first on OUPblog.

Examining photographs of Einstein’s brain is not phrenology!

Imagine that you return from work to find that a thief has broken into your home. The police arrive and ask if they may dust for finger and palm prints. Which would you do? (A) Refuse permission because palm reading is an antiquated pseudoscience or (B) give permission because forensic dermatoglyphics is sometimes useful for identifying culprits. A similar question may be asked about the photographs of the external surface of Albert Einstein’s brain that recently emerged after being lost to science for over half a century. If asked whether details of Einstein’s cerebral cortex should be identified and interpreted from the photographs, which would you answer? (A) No, because to conduct such a study would engage in the 19th century pseudoscience of phrenology or (B) Yes, because the investigation could produce interesting observations about the cerebral cortex of one of the world’s greatest geniuses and, in light of recent functional neuroimaging studies, might also suggest potentially testable hypotheses regarding Einstein’s brain and those of normal individuals. Lest you think this is a straw man (or Aunt Sally) exercise, more than one pundit has recently invoked the phrenology argument against studying Einstein’s brain. For example, one blogger opines, “I hope no one cares about Einstein’s brain. By this I mean his brain anatomy.” The three of us who were privileged to describe the treasure-trove of recently emerged photographs opted for B.

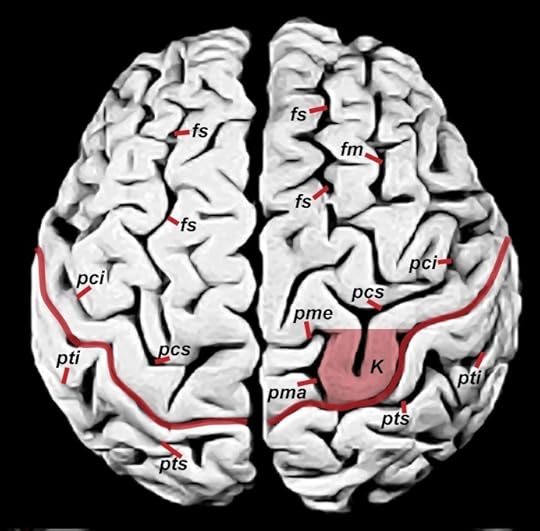

We did so because various data support studying the variation and functional correlates of folds (gyri) on the surface of the human brain and the grooves (sulci) that separate them. For example, David Van Essen hypothesizes that tensions along the connections between cells that course beneath the surface of the brain explains typical patterns of convolutions on its surface. Disruptions in the development of these connections in humans may result in abnormal convolutions that are associated with neurological problems such as autism and schizophrenia. Representations in sensory and motor regions of the cerebral cortex may change later in life as shown by imaging studies of Braille readers, upper limb amputees, and trained musicians, and sometimes these adaptations are correlated with superficial neuroanatomical features such as an enlargement in the right precentral gyrus (called the Omega Sign because of its shape) associated with movement of the left hand in expert string-players. Indeed, Einstein’s right hemisphere has an Omega Sign (labeled K in the following photograph, for knob), which is consistent with the fact that he was a right-handed string-player who took violin lessons between the ages of 6 and 14 years. The aforementioned blogger supports his opposition to studying Einstein’s cerebral cortex with the observation that “assuming causality with correlation” is “a cardinal sin of science”. However, this old saw does not mean that correlated features are necessarily causally unrelated. The functional imaging literature on the cerebral cortices of musicians and controls suggests that Einstein’s Omega Sign and his history as a violinist were probably not an unrelated coincidence.

Superior view of Einstein’s brain, with frontal lobes at the top. The shaded convolution labeled K is the Omega Sign (or knob), which is associated with enlargement of primary motor cortex for the left hand in right-handed experienced string-players.

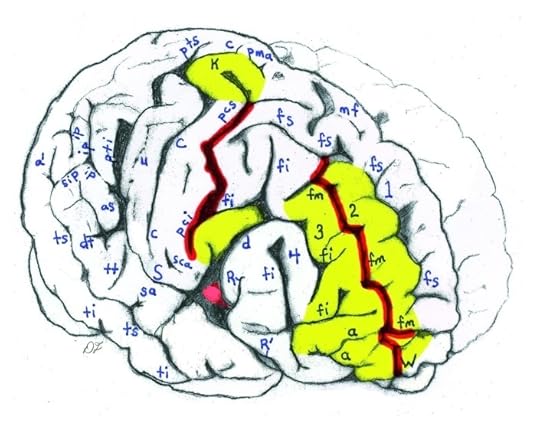

The investigation of previously unpublished photographs of Einstein’s brain reveals numerous unusual cortical features which suggest hypotheses that others may wish to explore in the histological slides of Einstein’s brain that surfaced along with the photographs. For example, Einstein’s brain has an unusually long midfrontal sulcus that divides the middle frontal region into two distinct gyri (labeled 2 & 3 in the following image), which causes his right frontal lobe to have four rather than the typical three gyri. An extra frontal gyrus is rare, but not unheard of. Einstein’s frontal lobe morphology is interesting because the human frontal polar region expanded differentially during hominin evolution, is involved in higher cognitive functions (including thought experiments), and is associated with complex wiring underneath its surface. These data suggest that the connectivity associated with Einstein’s prefrontal cortex may have been relatively complex, which could potentially be explored by investigating histological slides that were prepared from his brain after it was dissected.

Tracing from photograph of the right side of Einstein’s brain taken with the front of the brain rotated toward viewer. Unusual sulcal patterns are indicated in red; rare gyri are highlighted in yellow.

The microstructural organization in the parts of the cerebral cortex that are involved heavily in speech (Broca’s area and its homologue) were shown to be unique in their patterns of connectivity and lateralization in the genius Emil Krebs, who spoke more than 60 languages. That study, however, did not include information about the gross external neuroanatomy in the relevant regions. Functional neuroimaging technology is making it possible to explore the functional relationships between variations in external cortical morphology, subsurface microstructure including neuronal connectivity, and cognitive abilities. In other words, scientists should now be able to analyze form and function cohesively from the external surface of the cerebral cortex into the depths of the brain. Pseudoscience this is not.

Dr Dean Falk is the Hale G. Smith Professor of Anthropology at Florida State University and a Senior Scholar at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Dr Fred Lepore is Professor of Neurology and Ophthalmology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, New Jersey. Dr Adrianne Noe is Director of the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. You can read their paper, ‘The cerebral cortex of Albert Einstein: a description and preliminary analysis of unpublished photographs’ in full and for free. It appears in the journal Brain.

Brain provides researchers and clinicians with the finest original contributions in neurology. Leading studies in neurological science are balanced with practical clinical articles. Its citation rating is one of the highest for neurology journals, and it consistently publishes papers that become classics in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Both images are authors’ own. Do not reproduce without prior permission from the authors.

The post Examining photographs of Einstein’s brain is not phrenology! appeared first on OUPblog.

January 16, 2013

Drinking vessels: ‘goblet’

One more drinking vessel, and I’ll stop. Strangely, here we have another synonym for bumper, and it is again an old word of unknown origin. In English, goblet turned up in the fourteenth century, but its uninterrupted recorded history began about a hundred years later. Many names of vials, mugs, and beverages probably originated in the language of drinkers, pub owners, and glass manufacturers. They were slang, and we have little chance of guessing who coined it and in what circumstances.

Goblet may have been one of such coinages. French gobelet means the same as Engl. goblet, a word with a history not less obscure than that of its English namesake. The diminutive suffix -et is Romance, so that gobelet looks like the name of a little gobel. Unfortunately, we have no idea what a gobel is or was. Only gobeau has been attested. Nor does the suffix provide secure guidance to the origin of goblet. To be sure, the word may have been French, suffix and all, though it is strange that gobeau, not gobel, has turned up. On the other hand, a Romance suffix could be added to an English noun. Strumpet is almost certainly a Germanic word, but -et, as I mentioned in one of my previous blogs, turned a homegrown English whore into a classy Frenchified harlot. We had similar trouble with -ard in tankard.

An Old High German Reader by Theodor Wilhelm Braune.

Gobelet ~ goblet are not restricted to French and English. Spanish cubilette seems to be a close cognate going back to Medieval Latin cupellum “cup.” However, the similarity may be due to chance, because it remains unclear why the French and the English reflex of initial c (that is, k) should have been g. Derivation of gobelet from cup/cupellum, directly or via French, was proposed long ago. However, since the beginning of English lexicography it has had a strong rival. French gober means “swallow, gulp down.” Given such a root, goblet can be understood as a vial whose contents had to be gobbled up hurriedly or greedily — less than a fully convincing interpretation. Besides, we are in the dark about the origin of gober. Braune (1850-1926), one of the most distinguished German language historians, who had a rather frustrating habit of giving his name as Wilhelm on book covers but Theodor when signing his articles (so that for a long time I could not decide whether Wilhelm and Theodore, those precursors of Oscar Wilde’s Mr. Bunbury, were one person or two), isolated the root g-b ~ g-f in the Romance languages and traced it to Germanic. A seemingly ill-assorted group of words, including goblet, gag, giggle, goggle, javelin, jig, jug, and quite a few others, found themselves in the same group. If a scholar less solid and of less fame than Braune had come up with such a list, it would have been laughed out of court. As a matter of fact, a series of articles by him, all of which are like the one in which gob and goblet occur (1922), had minimal influence on Germanic etymologists; it seems because they have been ignored rather than rejected as containing fanciful ideas.Not unexpectedly, a connection between gob and goblet occurred to many people before 1922. To justify it, goblet was defined as “a cup containing a long quantity for one opening of the mouth, for one draft or swallow” (Charles Richardson). How much one can drink at one opening of the mouth depends on the size of the consumer’s throat and cannot serve as a foundation for a secure etymology. Hensleigh Wedgwood, who always tried to detect sound imitative roots in English words, explained goblet so: “The names of vessels for containing liquids are often taken from the image of pouring out water, expressed by forms representing the sound of water guggling out of the mouth of a narrow-necked vessel.” As usual, he cited numerous words from various languages bearing out his conclusion. Wedgwood’s etymology makes sense, and many dictionaries offer some version of it, specifying that the source of gob might be the Irish word for “mouth” and “beak.” I have a curious confirmation of his hypothesis. Russian drunks are in the habit of sharing a half-liter bottle among three people. But how can 500 grams be divided into three equal parts? Strangely, in the process of careful pouring a half-liter bottle yields 21 “glugs.” Each thirsty alcoholic receives seven glugs. This is (at best) what scholars call anecdotal evidence. We still face the question whether gob and goblet are related. Nor should it be forgotten that goblets are not narrow-necked.

Uncle Toby

Those who have read my essay posted two weeks ago will remember that Ernest Weekley derived tankard from a proper name. He offered a similar etymology for goblet and many other vessels. This is what he said (I will only expand his abbreviations): “goblet. Old French gobelet, diminutive of gobel, gobeau. All these words are French surnames, Old High German God-bald, god-bold (cf. Engl. Godbolt), and the vessel is no doubt of same origin. Cf. Engl. dialectal gaddard, goblet, Old French godart, Old German Gott-hart, god-strong, named in same way. See goblin, and cf. demijohn, jack, gill, jug, tankard, Middle Engl. jubbe (Job) in Chaucer, etc.” In the entry tankard, he also mentioned toby-jug, bellarmine, and puncheon. Under his pen goblin ended up as a diminutive name of Gobel. A Toby Philpot jug, or simply Uncle Toby, was made in the shape of a stout man in a long coat, knee breeches, and three-cornered hat, seated. The phrase no doubt, when used in etymological studies, always makes me wince. Toby is a clear case. Perhaps Weekley guessed well that tankard has something to do with Tancred, but the path from God-bald to goblet is not straight. As concerns style, Weekley’s entries resemble Braune’s article: inspiring but a bit reckless.Thus, we have several conjectures: goblet may go back to Latin cupellum, via French, or to Engl. gobble (which may be traced to Irish gob), or to the name God-bald, admittedly, not much to choose from. In a very general way, Braune may have been right. It seems that goblet is ultimately a Germanic word (regardless of its putative ties with Irish gob “beak, mouth”) and that its derivation from Latin and French, though supported by such authorities as Skeat, should be treated with a grain of salt.

When dictionaries explain the rhetorical figure of hendiadys, they sometimes give the example drink from gold and goblet for drink from golden goblets. Let this fact efface the salty impression left by the last sentence, above.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Themas well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Cover page for Althochdeutsches Lesebuch (1888) via Open Library. (2) Toby Jug, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England. Reptonix free Creative Commons licensed photos via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Drinking vessels: ‘goblet’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers