Oxford University Press's Blog, page 981

February 1, 2013

Collective redress – another false dawn?

Collective action reform in England and Wales was first seriously mooted twenty five years ago. From the perspective of proponents of the opt-out form of collective action (i.e., a form of collective proceedings where all the potential claimants are automatically represented in the proceedings unless they explicitly choose not to be), nothing of substance has been achieved since then. The closest advocates for reform got were the class action provisions in the 2009 Financial Services Bill, which were dropped at the last minute to help secure the Bill’s enactment prior to the 2010 general election.

Since 2010 prospects for reform have been slight. A pre-general election consultation by the Department for Business, Innovation and & Skills (BIS), which raised the issue of a consumer collective action, disappeared without trace. In this there was nothing to surprise the sceptic: collective action consultations have historically yielded nothing. In April 2012, to the surprise of many, BIS issued another consultation. This time its focus is reform of the follow-on opt-in form of collective action which can be used in claims brought under the Competition Act 1998

The present consultation once more raises issues which, given the 25 year history of abortive reform, have been debated to the nth degree, two of which do however need detailed consideration.

First, the consultation moves beyond the government’s previous position that if reform is to be implemented it should be consistent with the Civil Justice Council’s 2008 recommendations. In particular it proposes that an opt-out form of action be introduced; the CJC had rejected the introduction of an opt-out action in favour of one where the court determines on a case-by-case basis whether the action should be opt-in (i.e., where a claimant has take deliberate and express steps to be brought within the scope of the proceedings) or opt-out.

BIS’s proposal is predicated, amongst other things, on the grounds that the present Competition Act opt-in procedure is inadequate; inadequate because it has only ever been used once, in the JJB Football shirts case and then only because, it is claimed, a mere 130 individuals opted-in. The factual claim is contentious: opt-in figure was arguably 550, if not higher, with an additional 15,000 individuals claiming under the settlement reached in the proceedings. More substantively, the consultation does not appear to grapple with the question whether the lack of claimants opting-in is actually a sign that individuals are making a proper choice not to pursue an individually de minimus claim, and whether an opt-out system actually amounts in such circumstances to an improper fetter on an individual’s choice to resort to litigation to enforce their rights. It is a question that the CJC did not consider. If reform is to come, it might perhaps be better if it came after principled consideration of this issue.

Secondly, the consultation raises the question of what happens to damages awarded under an opt-out procedure which go unclaimed. Opt-out systems always result in some, if not the majority of, damages going unclaimed. Rather than being taken as a sign that the procedure does not provide access to justice, compensation for loss or the enforcement of private rights for those individuals whose rights were infringed, the unclaimed damages are viewed as something which can be distributed by the court for a purpose related to the substance of the claim (a cy-pres distribution). The consultation, for the first time, proposes that unclaimed damages should not be distributed this way but should rather be paid to the Access to Justice Foundation.

Critics might suggest that whatever the merits of a cy-pres distribution, at least it is intended to result in a benefit to those similarly situated to the individuals whose rights had been infringed. Requiring such funds to be paid to a charity, no matter how meritorious, which has nothing to do with the rights infringed, might be said to run contrary to the aim of enforcing rights and securing effective compensation for those harmed individuals. It might even be said, as it was in the United States in the context of a statutory provision which required unclaimed damages to be paid to the State, to ‘cripple the compensatory function for the private class’ (State of California v. Levi Strauss & Co., 715 P.2d 564, 575 (Cal. 1986)).

Hopefully BIS will consider these, and the other issues which its proposes raise, and in doing so ensure that reform, if it comes, is consistent with securing effective access to justice for those who genuinely wish to pursue their claims and see their rights enforced; a commitment to the rule of law requires no less. If it does not, its consultation will be yet another false dawn.

Prof John Sorabji (Hon) is Senior Fellow, Judicial Institute, University College, London, barrister and Legal Secretary to the Master of the Rolls. He is a contributor to Extraterritoriality and Collective Redress, edited by Duncan Fairgrieve and Eva Lein. Any views expressed in this article are those of the author and are neither intended to nor do they represent the views of any other individual or body.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Collective redress – another false dawn? appeared first on OUPblog.

A Very Short Film competition

The Very Short Film competition was launched in partnership with The Guardian in October 2012. The longlisted entries are now available for the public vote which will produce four finalists. After a live final in March, the winner will receive £9000 towards their university education.

By Chloe Foster

After more than three months of students carefully planning and creating their entries, the Very Short Film competition has closed and the longlisted submissions have been announced.

The competition asked entrants to create a short film which would inform and inspire us. Students were free to base their entry on any subject they were passionate about. There was just one rule: films could be no longer than 60 seconds in length.

We certainly had many who managed to do this. The standard of films was impressive. How were we to whittle down the entries and choose just 12 for the longlist?

We received a real range of films from a variety of ages, characters and subjects — everything from scuba diving to the economic state of the housing market. It was great to see a mixture of academic subjects and topics of personal interest.

It must be said that the quality of the filmmaking itself was very high in some entries. However not all of these could be put through to the longlist; although artistic and clever, they didn’t inform us in the way our criteria specified.

When choosing the longlisted entries, judges looked for students who were clearly on top of their subject. We were most impressed by films that conveyed a topic’s key information in a concise way, were delivered with passion and verve, and left us wanting to find out more. By the end of our selection process, we felt that each of the films had taught us something new or made us think about a subject in a way we hadn’t before.

The sheer amount of information filmmakers managed to convey was astounding. As the Very Short Introductions editor Andrea Keegan says: “I thought condensing a large topic into 35,000 words, as we do in the Very Short Introductions books was difficult enough, but I think that this challenge was even harder. I was very impressed with the quality and variety of videos which were submitted.

“Ranging from artistic to zany, I learned a lot, and had lots of fun watching them. The longlist represents both a wide range of subjects — from the history of film to quantum locking — and a huge range in the approaches taken to get the subjects across in just one minute.”

We hope the entrants enjoyed thinking about and creating their films as much as we enjoyed watching them. We asked a few of the longlisted students what they made of the experience. Mahshad Torkan, studying at the London School of Film, tackled the political power of film: “I am very thankful for this amazing opportunity that has allowed me to reflect my values and beliefs and share my dreams with other people. I believe that the future is not something we enter, the future is something we create.”

Maia Krall Fry is reading geology at St Andrews: “It seemed highly important to discuss a topic that has really captured my curiosity and sense of adventure. I strongly believe that knowledge of the history of the earth should be accessible to everyone.”

Matt Burnett, who is studying for an MSc in biological and bioprocess engineering at Sheffield, used his film to explore the challenges of creating cost-effective therapeutic drugs: “I felt that in a minute it would be very hard to explain my research in enough detail just using speech, and it would be difficult to demonstrate or act out. I simplify difficult concepts for myself by drawing diagrams, often spending a lot of time on them. For me it is the most enjoyable part of learning, and so I thought it would be fun to draw an animated video. If I get the chance to do it again I think I’d use lots of colours.”

So, what are you waiting for? Take a look at the 12 films and pick your favourite of these amazingly creative and intelligent entries.

Chloe Foster is from the Very Short Introductions team at Oxford University Press. This article originally appeared on guardian.co.uk.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Very Short Film competition appeared first on OUPblog.

January 31, 2013

Ríos Montt to face genocide trial in Guatemala

After the judge’s ruling Monday in Guatemala City, the crowd outside erupted into cheers and set off fireworks. The unthinkable had happened: Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez had cleared the way for retired General Efraín Ríos Montt, who between 1982 and 1983 had overseen the darkest years of that nation’s 36-year long armed conflict, would stand trial for genocide. In that conflict (1960-1996), more than 150,000 Guatemalans died, the majority at the hands of their own government, which used their lives to prosecute a ferocious counterinsurgency war against a group of Marxist guerrillas who had hoped to bring a Sandinista-style socialist regime to Guatemala. For many, General Ríos Montt represented the face of this war, because it was during his short terms as president between March 1982 and August 1983 (he both came to power and was expelled in military coup d’états), that the Guatemalan army undertook the most bloody operation of the war, a violent scorched-earth campaign that not only nearly eliminated the guerrillas military operation, but which also killed many thousands of civilians, the vast majority of them Maya “Indians.” Now, some thirty years later, Ríos Montt will be prosecuted along with his former chief of intelligence, Mauricio Rodriguez Sánchez, for genocide and crimes against humanity. Specifically, he will be charged with ordering the killings of more than 1,700 Maya Ixil people in a series of massacres that the Army conducted in the northern part of the country in 1982.

The axiom “justice delayed is justice denied” notwithstanding, the prosecution of fatally misguided leaders and despots such as Serbia’s Radovan Karadžić or Hutu leader Beatrice Munyenyezi is not unusual in the early 21st century. Trials such as these are designed to serve the cause of justice, of course, but they are also instrumental in helping a traumatized society create a coherent narrative and build a collective historical memory around what happened in its recent past. What is unusual about the case against Ríos Montt is that almost no one foresaw the day when such a trial would ever take place in Guatemala. In large part, this stems from Guatemala’s long-standing culture of impunity, where few people, from common criminals all the way up to corrupt businessmen and military officers, are held accountable for their crimes; generally speaking, the rule of law there simply does not rule. Beyond that, Ríos Montt’s continued influence in the country—among other things, he established and headed a powerful political party, the Frente Republicano Guatemalteco in the 1989, and he run an unsuccessful campaign for president as recently as 2003—further mitigated against expectations for his prosecution. His daughter, Zury Ríos Montt (who is married to former US Congressman Jerry Weller) is a rising and powerful young politician; her support for her father is so absolute that she stormed out of the courtroom yesterday before the judge could finalize his pronouncement. But most of all, the prosecution of Ríos Montt seemed most unlikely because, in the strange paradox of power that sometimes comes with authoritarian regimes, there were, and still continue to be, some Guatemalans who continue to respect him, remembering his bloody rule as a time when one could walk the streets of the capital safely and when the “raging wolves” of communism were kept at bay.

Adding to the complexity of this case is that fact that, at the time he served as chief of state in the early 1980s, (although called “President,” he did not actually hold this title, having taken power in a coup), Ríos Montt was a newly born again Christian, a member of a neo-Pentecostal denomination called the Church of the Word (Verbo). Fresh from the rush of his conversion, Ríos Montt addressed the nation weekly during his term of office, offering what people called his “Sunday sermons,”—discourses in which he drifted freely from topics ranging from his desire to defeat the “subversion,” to advice on wholesome family living, to his particular vision of a “New Guatemala” where all peoples would live together as one (a jab at the unassimilated Maya), in compliant obedience to a benign government that served the general good. Ríos Montt’s dream of a New Guatemala was in many ways as elusive as quicksilver, and in his sermons, he made no mention of the carnage going on in the countryside. The sacrifice of the Maya people and other “subversives” was not at all too high a price to pay, in his estimation, for the New Guatemala.

But the elegance, even the peaceability of his language, along with his strong affiliation with the Church of the Word (his closes advisors were church leaders, not his fellow generals) in that moment made Ríos Montt the darling of the emergent leaders of the Christian Right in the United States who were coming of age during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. For them, as for the Reagan administration, Ríos Montt seemed to have emerged out of nowhere from the turmoil of the Central American crisis of the early 1980s as an anti-communist Christian soldier and ally. It seemed unthinkable to them that the same man who, with one hand, reached out to called for honesty and familial devotion from his people, would order the killing of his own people with his other. And so it seems to some Guatemalans even today. Yet the strong and irrefutable body of evidence that produced yesterday’s ruling tells a very different, and much more tragic story.

Virginia Garrard-Burnett is a Professor of History and Religious Studies at the University of Texas-Austin and the author of Terror in the Land of the Holy Spirit: Guatemala under General Efrain Rios Montt 1982-1983.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ríos Montt to face genocide trial in Guatemala appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding and respecting markets

Almost every day has brought a fresh story about investment markets, their strengths and weaknesses. Misreporting of data for calculation of LIBOR, money laundering with a whiff of Central American drugs trading, costly malfunctioning of programme trading mechanisms which brought the trading company to its knees, reputational damage inflicted by as yet unsubstantiated accusations of illicit financing in breach of international sanctions… the list goes on and on.

Toronto Financial District. Photo by Alessio Bragadini, 23 June 2009. Creative Commons License.

And this has all been on top of the recent history of the so-called credit crunch and the self-inflicted wounds that have beset the banking industry over the last five years, with consequentially a savage public backlash of distrust and dislike of bankers and banks. This has affected the banking fraternity as a whole, even though those that caused the damage to their banks, to the shareholders and in the end to the taxpayers, were a small sub-set only of the banking workforce.The list of problems, for firms, and in some cases for their customers as well, prompts some reflections about the role of investment markets in our society and about the relationship between markets and their regulation. Some years ago, in the latter part of the last century, it was fashionable for academics and practitioners alike to put their trust in the strength and reliability of market mechanisms. The experience in earlier decades of the hard discipline of the money markets no doubt added to this. For example the humiliation of the forced departure of the United Kingdom from the former European Monetary mechanism (EMU) in the 1980s reinforced the beliefs of many in the power of the markets as a way of finding and pricing out inefficiency and restoring a new equilibrium at a different point on the scale.

To the majority, therefore, the proper role of regulation at that time was essentially limited to cases of market failure. Most of the work in the public interest could be done by the markets themselves. They might, of course, need some help from the regulators to ensure proper disclosure, with a view to sufficient, and non-discriminatory, access by market users and commentators to market information. But if there was “sunlight” in the market, then that more or less guaranteed the “hygiene” of its mechanisms. From that concept came “light touch” as a means of describing a system of financial regulation that basically left it to well informed markets to function for themselves.

Not all agreed at the time with this general approach. There were honourable exceptions, whose only consolation since has been the (frequently best left unsaid) phrase “I told you so at the time”.

How things have changed since then! A rapid U-turn in public and political thinking has brought demands for sterner and more intrusive regulation. The insidiousness of human greed and of lack of foresight is now widely recognised and needs to be restrained. The market economists now accept that there is a real, and central, role for discipline, including both its punitive and its deterrent aspects as well as the benefits it brings in excluding the dangerous from the playing field altogether. The change has even led our politicians to embark on structural change to restore a previous splitting of retail regulation from the upper reaches of financial services. The case for this change has been based on a hope of better focus of the two new bodies on the two sectors, though the underlying motive appears more to be a desire to change something simply because it is thought to have failed.

Splitting in the public interest also seems likely to be required in the major banks as well. The “Vickers” reforms look set to require the banking industry to function in two separate ways, with required distance between the investment banking arms and the general consumer-based borrowing and lending functions.

Another consequence is that “enforcement” is once more central to the world of regulation, rather than seen as a stick kept, as far as was possible, in the cupboard for occasional use only in the most serious circumstances.

We have now arrived at a new post-crisis period of great challenge but also of potential opportunity. We seem to be set for a number of difficult coming years, during which the markets will be dominated and constrained by austerity, continuing uncertainty and risks of instability. But markets and economies tend to recover over time. We must hope that the politicians, central banks and regulatory authorities have learned all of the necessary lessons from the recent crises to prevent instability or, at least, better to manage and contain the risks of it.

Michael Blair QC, Professor George Walker, and Stuart Willey are the editors of the new edition of Financial Markets and Exchanges Law. Michael Blair QC is in independent practice at the Bar of England and Wales specialising in financial services. Previously General Counsel to the Board of the Financial Services Authority. Queen’s Counsel honoris causa 1996. George Walker is Professor in International Financial Law at School of Law, Queen Mary University of London and is a member of the Centre for Commercial Law Studies (CCLS). He is also a Barrister and Member of the Honourable Society of Inner Temple in London. Stuart Willey is Counsel and Head of the Regulatory Practice in the Banking & Capital Markets group of White & Case in London. Stuart specializes in financial regulation focusing on the securities markets, banking and insurance.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Understanding and respecting markets appeared first on OUPblog.

To memorize or not to memorize

I have a confession to make: I have a terrible memory. Well, for some things, anyway. I can name at least three movies and TV shows that Mary McDonnell has been in off the top of my head (Evidence of Blood, Donnie Darko, Battlestar Galactica), and rattle off the names of the seven Harry Potter books, but you take away that Beethoven piano score that I’ve been playing from since I was 14, and my fingers freeze on the keyboard. My inability to memorize music was in fact the reason I gave up on my dream of being a concert pianist—though, in retrospect, this was probably the right move for me given how lonely I would get during hours-long practice sessions…

I’ve since come to terms with my memory “deficiency,” but a recent New York Times article by Anthony Tommasini on the hegemonic influence of memorization in certain classical performing traditions brought some old feelings to the fore. Why did I have to memorize the music I was performing, especially considering how gifted I was at reading music notation (if I may say so myself)?

As Tommasini points out (citing this article by Stephen Hough), the tradition of performing from memory as a solo instrumentalist is a relatively young one, introduced by virtuosi like Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann in the 1800s. Before that, it was considered a bit gauche to play from memory, as the assumption was that if you were playing without a score in front of you, you were improvising an original piece.

I should be clear at this point that I have nothing against musicians performing from memory. Indeed some performers have the opposite problem to mine: the sight of music notation during performance is a stressor, not a helper. Nonetheless, I do feel that the stronghold that memorization has on classical soloist performance culture needs to be slackened.

One memory in particular related to memorization haunts me still. After sweating through a Bach organ trio sonata during a master class in the early 00s, the dear late David Craighead gave me some gentle praise and encouraged me to memorize the piece. “Make it your own” were his words. I was devastated. How on earth was I going to memorize such a complex piece?

In spite of my devastated feelings, I heard a nagging voice in the back of my mind telling me Dr. Craighead was right. If only I could memorize the piece, it truly would be my own. I’d heard before from other teachers that the best way to completely “ingest” a piece was to practice it until you didn’t need the score anymore. The lone recital I gave from memory during my college years was admittedly an exhilarating experience; I definitely felt that I had a type of ownership over the pieces, even if I was in constant terror of having a memory lapse. In hindsight, though, I believe my sense of ownership was not a result of score-freedom, but from the hours and hours (and hours) I spent in the practice room preparing for the recital.

Whether or not you are moved by my struggles (being a little facetious here), I think that, in 2013, it is time for us to acknowledge the multiplicity of talents a classical soloist may possess, and stop trying to squeeze everyone into the same box.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post To memorize or not to memorize appeared first on OUPblog.

What is a false allegation of rape?

What is a false allegation of rape? At first, this might appear to be a daft question. Reflecting the general tendency to think of the truth or otherwise of allegations in reductive terms of being either true or false, the meaning of “false allegation” is commonly taken to be self-evident. A false allegation of rape is an allegation that is false; the rape alleged did not, in fact, occur. In the abstract, this seems a perfectly logical and sensible approach.

In practice, however, there is much more to making a formal rape complaint than the simple and solitary assertion, “I was raped”, or, where the identity of the accused is known, “I was raped by X”. Complainants’ statements comprise multiple assertions of fact detailing when an alleged incident happened, where it happened, how it happened, and at whose hands, as well as giving an account of the events and circumstances leading up to and following the incident. For criminal justice professionals, whose priorities are trial-focussed, the question of veracity extends to each and every statement of fact – the who, what, where, when, how and so forth – contained in a complainant’s account. As complainants may conceal or actively lie about any one or more of these facts, the messy reality is that some rape allegations may be more (or less) true (or false) than others. This raises a conceptual question: is an allegation “false” because it’s not genuine, or because it’s not true?

In practice, however, there is much more to making a formal rape complaint than the simple and solitary assertion, “I was raped”, or, where the identity of the accused is known, “I was raped by X”. Complainants’ statements comprise multiple assertions of fact detailing when an alleged incident happened, where it happened, how it happened, and at whose hands, as well as giving an account of the events and circumstances leading up to and following the incident. For criminal justice professionals, whose priorities are trial-focussed, the question of veracity extends to each and every statement of fact – the who, what, where, when, how and so forth – contained in a complainant’s account. As complainants may conceal or actively lie about any one or more of these facts, the messy reality is that some rape allegations may be more (or less) true (or false) than others. This raises a conceptual question: is an allegation “false” because it’s not genuine, or because it’s not true?

Of course, there’s a certain degree of overlap between these two approaches. Presumably, we would all agree that the alleged rape which is, in fact, a complete fabrication of something that never happened is a false allegation. But how would you describe the allegations of a complainant who, for example, reports being ambushed at midnight by a knife-wielding stranger, dragged into nearby bushes and raped, when CCTV footage, witness statements, and scientific evidence prove unequivocally that the complainant and accused had, in fact, spent the evening drinking together in various local bars and that sex took place at the accused’s home? Or the allegations of a rape complainant who maintains that she (or he) was stone-cold sober at the material time, when a toxicology report shows that, in fact, the complainant had consumed a significant amount of alcohol and a fair amount of cocaine, and witnesses state that she had done so voluntarily? Clearly, the fact that a complainant has lied about some detail or other in their statement(s) does not mean that there was, in fact, no rape. It does, however, mean that their allegations aren’t (entirely) true. Despite a genuine rape incident at the heart of the allegation, the complainant’s account contains assertions of fact that are demonstrably false. And the falsehoods in a complainant’s statement(s) have potentially catastrophic implications for a prosecution. If the complainant, almost invariably the prosecution’s chief witness in a rape trial, has a documented history of providing evidence which, although sworn on pain of prosecution to be true, is, in fact, false, then a prosecution is unlikely to proceed. There may well have been a rape but, in the absence of compelling prosecution evidence independent of the complainant, the chances of proving beyond reasonable doubt that there was are slim.

Regardless of one’s conceptual approach, then, referring to the alleged rape that didn’t happen as a “false allegation” is uncontroversial. The issue really is whether the rape that didn’t happen the way the complainant said it did might also be described as false. And that is an issue on which reasonable minds might – and, as I have recently argued, do – reasonably differ. “Well,” you may say, “so the ‘false allegation’ is a contestable concept. Big deal. So what?” Well, it is a big deal because nobody’s really discussing what “false allegations” are and yet people keep trying to count them! There’s a fairly extensive research literature and broader critical debate, spanning several decades, on the prevalence of false rape allegations. The prevailing academic orthodoxy insists that false allegations of rape are rare, or at least no more common than false allegations of other offences, with those claiming otherwise – usually criminal justice professionals with first-hand experience of investigating and prosecuting rape cases – quickly dismissed by the mainstream as misogynists and sceptics. But how one conceptualises and defines the “false allegation” has a direct, and often striking, effect on how many are observed. Despite repeated claims to the contrary, research findings are consistent only in their inconsistency. Estimated prevalence rates for false rape allegations range from the sublime to the ridiculous. So the contestable nature of the concept of the “false allegation” matters because divergent estimates may reflect methodological rather than attitudinal factors. Put simply, the various protagonists may not all be counting the same things.

Dr Candida Saunders is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Nottingham. Her article, The Truth, the Half-truth and Nothing like the Truth: Reconceptualizing False Allegations of Rape, appears in The British Journal of Criminology where you can read it in full and for free via the link above.

The British Journal of Criminology: An International Review of Crime and Society is one of the world’s top criminology journals. It publishes work of the highest quality from around the world and across all areas of criminology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Police Lantern In England Outside The Station. By Stuart Miles, iStockPhoto.

The post What is a false allegation of rape? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 30, 2013

The non-interventionist moment

The signs are clear. President Barack Obama has nominated two leading skeptics of American military intervention for the most important national security cabinet posts. Meeting with Afghan President Hamid Karzai, who would prefer a substantial American residual presence after the last American combat troops have departed in 2014, Obama has signaled that he wants a more rapid transition out of an active combat role (perhaps as soon as this spring, rather than during the summer). The president has also countered a push from his own military advisors to keep a sizable force in Afghanistan indefinitely by agreeing to consider the “zero option” of a complete withdrawal. We appear on the verge of a non-interventionist moment in American politics, when leaders and the general public alike shun major military actions.

Only a decade ago, George W. Bush stood before the graduating class at West Point to proclaim the dawn of a new era in American security policy. Neither deterrence nor containment, he declared, sufficed to deal with the threat posed by “shadowy terrorist networks with no nation or citizens to defend” or with “unbalanced dictators” possessing weapons of mass destruction. “[O]ur security will require all Americans to be forward looking and resolute, to be ready for preemptive action when necessary to defend our liberty and to defend our lives.” This new “Bush Doctrine” would soon be put into effect. In March 2003, the president ordered the US military to invade Iraq to remove one of those “unstable dictators,” Saddam Hussein.

This post-9/11 sense of assertiveness did not last. Long and costly wars in Iraq and Afghanistan discredited the leaders responsible and curbed any popular taste for military intervention on demand. Over the past two years, these reservations have become obvious as other situations arose that might have invited the use of troops just a few years earlier: Obama intervened in Libya but refused to send ground forces; the administration has rejected direct measures in the Syrian civil war such as no-fly zones; and the president refused to be stampeded into bombing Iranian nuclear facilities.

The reaction against frustrating wars follows a familiar historical pattern. In the aftermath of both the Korean War and the Vietnam War, Americans expressed a similar reluctance about military intervention. Soon after the 1953 truce that ended the Korean stalemate, the Eisenhower administration faced the prospect of intervention in Indochina, to forestall the collapse of the French position with the pending Viet Minh victory at Dien Bien Phu. As related by Fredrik Logevall in his excellent recent book, Embers of War, both Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles were fully prepared to deploy American troops. But they realized that in the backwash from Korea neither the American people nor Congress would countenance unilateral action. Congressional leaders indicated that allies, the British in particular, would need to participate. Unable to secure agreement from British foreign secretary Anthony Eden, Eisenhower and Dulles were thwarted, and decided instead to throw their support behind the new South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem.

Another period marked by reluctance to use force followed the Vietnam War. Once the last American troops withdrew in 1973, Congress rejected the possibility they might return, banning intervention in Indochina without explicit legislative approval. Congress also adopted the War Powers Resolution, more significant as a symbolic statement about the wish to avoid being drawn into a protracted military conflict by presidential initiative than as a practical measure to curb presidential bellicosity.

It is no coincidence that Obama’s key foreign and defense policy nominees were shaped by the crucible of Vietnam. Both Chuck Hagel and John Kerry fought in that war and came away with “the same sensibility about the futilities of war.” Their outlook contrasts sharply with that of Obama’s initial first-term selections to run the State Department and the Pentagon: both Hillary Clinton and Robert Gates backed an increased commitment of troops in Afghanistan in 2009. Although Senators Hagel and Kerry supported the 2002 congressional resolution authorizing the use of force in Iraq, they became early critics of the war. Hagel has expressed doubts about retaining American troops in Afghanistan or using force against Iran.

Given the present climate, we are unlikely to see a major American military commitment during the next several years. Obama’s choice of Kerry and Hagel reflect his view that, as he put it in the 2012 presidential debate about foreign policy, the time has come for nation-building at home. It will suffice in the short run to hold distant threats at bay. Insofar as possible, the United States will rely on economic sanctions and “light footprint” methods such as drone strikes on suspected terrorists.

If the past is any guide, however, this non-interventionist moment won’t last. The post-Korea and post-Vietnam interludes of reluctance gave way within a decade to a renewed willingness to send American troops into combat. By the mid-1960s, Lyndon Johnson had embraced escalation in Vietnam; Ronald Reagan made his statement through his over-hyped invasion of Grenada to crush its pipsqueak revolutionary regime. The American people backed both decisions.

The return to interventionism will recur because the underlying conditions that invite it have not changed significantly. In the global order, the United States remains the hegemonic power that seeks to preserve stability. We retain a military that is more powerful by several orders of magnitude than any other, and will surely remain so even after the anticipate reductions in defense spending. Psychologically, the American people have long been sensitive to distant threats, and we have shown that we can be stampeded into endorsing military action when a president identifies a danger to our security. (And presidents themselves become vulnerable to charges that they are tolerating American decline whenever a hostile regime comes to power anywhere in the world.)

Those of us who question the American proclivity to resort to the use of force, then, should enjoy the moment.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The non-interventionist moment appeared first on OUPblog.

Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1

Last time I was writing my monthly gleanings in anticipation of the New Year. January 1 came and went, but good memories of many things remain. I would like to begin this set with saying how pleased and touched I was by our correspondents’ appreciation of my work, by their words of encouragement, and by their promise to go on reading the blog in the future. Writing weekly posts is a great pleasure. Knowing that one’s voice is not lost in the wilderness doubles and trebles this pleasure.

Week and Vikings.

After this introduction it is only natural to begin the first gleanings of 2013 with the noun week. Quite some time ago, I devoted a special post to it. Later the root of week turned up in the post on the origin of the word Viking, and it was Viking that made our correspondent return to week. My ideas on the etymology of week are not original. In the older Germanic languages, this noun did not mean “a succession of seven days.” The notion of such a unit goes back to the Romans and ultimately to the Jewish calendar. The Latin look-alike of Gothic wiko, Old Engl. wicu, and so forth was a feminine noun, whose nominative, if it existed, must have had the form vix. Since the phrase for “in the order of his course” (Luke I: 8) appears in Latin as in ordine vicis suae and in Gothic as in wikon kunjis seinis, some people (the great Icelandic scholar Guðbrandur Vigfússon among them) made the wrong conclusion that the Germanic word was borrowed from Latin. In English, the root of vix can be seen in vicar (an Anglo-French word derived from Latin vicarius “substitute, deputy”), vicarious, vicissitude, vice (as in Vice President), and others, while week is native. Its distant origin is disputed and need not delay us here. Rather probably, German Wechsel (from wehsal) “exchange” belongs here. Among the old cognates of week we find Old Icelandic vika, which also had the sense “sea mile,” and this is where Viking may come in. “Change, succession, recurrent period” and “sea mile” suggest that the oldest Vikings (in the beginning, far from being sea robbers and invaders) were called after “shift, a change of oarsmen.” But many other hypotheses pretend to explain the origin of Viking, and a few of them are not entirely implausible.

The present perfect.

More recently, while discussing suppletive forms, I mentioned in passing that the difference between tenses can become blurred and that for some people did you put the butter in the refrigerator? and have you put the butter in the refrigerator? mean practically the same. This remark inspired two predictable comments. The vagaries of the present perfect also turned up in one of my recent posts and also caused a ripple of excitement, especially among the native speakers of Swedish. As with week and Viking, I’ll repeat here only my basic explanation. In Germanic, the perfect tenses developed in the full light of history, and in British English a good deal seems to have changed since the days of Shakespeare, that is, the time when the first Europeans settled in the New World. To put it in a nutshell, there was much less of the present perfect in the sixteenth and the seventeenth century than in the nineteenth. In the use of this tense English, wherever it is spoken, went its own way. For instance, one can say in Icelandic (I’ll provide a verbatim translation): “We spent a delightful summer together in 1918, and at that time we have seen so many interesting places together!” The perfect foregrounds the event and makes it part of the present. In English, the present perfect cannot be used so. Only a vague reference to the days gone by will tolerate the present perfect, as in: “This has happened more than once in the past and is sure to happen again.” Therefore, I was surprised to see Cuthbert Bede (alias Edward Bradley) write in The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green: “Who knows? for dons are also mortals, and have been undergraduates once” (the beginning of Chapter 4). In my opinion, have been and once do not go together. If I am wrong, please correct me.

However, in my next pronouncement I am certainly right. British English has regularized the use of the present perfect: “I have just seen him,” “I have never read Fielding,” and so on. I mentioned in my original post that, when foreigners are taught the difference between the simple past (the so-called past indefinite) and the present perfect, they are usually shown a picture of a weeping or frightened child looking at the fragments on the floor and complaining to a grownup: “I have broken a plate!” American speakers are not bound by this usage: “I just saw him. He left,” “I never read Fielding and know no one who did,” while a child would cry: “Mother, I broke a plate!” A British mother may be really cross with the miscreant, whereas an American one may be mad at the child, but their reaction has nothing to do with grammar. Our British correspondent says that he makes a clear distinction between did you and have you put the butter in the refrigerator, while his American wife does not and prefers did you. This is exactly what could be expected. My British colleague, who has not changed his accent the tiniest bit after decades of living in Minneapolis and being married to an American, must have unconsciously modified his usage. I have been preoccupied with the perfect for years, and once, when we were discussing these things, he said, with reference to the present perfect, that during his recent stay in England, his interlocutor remarked drily: “You have lived in America too long.”

Blessedly cursed? Tamara and Demon. Ill to Lermontov’s poem by Mikhail Vrubel’, 1890. (Tretiakov gallery.) Demon and Tamara are the protagonists in the poem by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). The poem is famous in Russia; there is an opera on its plot; several translations into English, including one by Anatoly Liberman, exist; and Vrubel’ was obsessed by this work.

Suppletive girls and wives.In discussing suppletive forms (go/went, be/am/is/are, and others), I wrote that, although we have pairs like actor/actress and lion/lioness, we are not surprised that boy and girl are not derived from the same root. I should have used a more cautious formulation. First, I was asked about man and woman. Yes, it is true that woman goes back to wif-man, but, in Old English, man meant “person,” while “male” was the result of later specialization, just as in Middle High German man had the senses “man, warrior, vassal,” and “lover.” Wifman meant “female person.” The situation is more complicated with boys and girls. Romance speakers will immediately remember (as did our correspondent, a native speaker of Portuguese) Italian fanciullo (masculine) ~ fanciulla (feminine) and the like. In Latin, such pairs also existed (puellus and puella). But I don’t think that fanciulla and puella were formed from funciullo and puellus: they are rather parallel forms. But I am grateful for being reminded of such pairs; they certainly share the same root.

Lewis Carroll’s name.

I think the information provided by Stephen Goranson is sufficient to conclude that the Dodgson family pronounced their family name as Dodson, and this confirms my limited experience with the people called Dodgson and Hodgson.

PS. At my recent talk show on Minnesota Public Radio, which was devoted to overused words, I received a long list of nouns, adjectives, and verbs that our listeners hate. I will discuss them and answer more questions next Wednesday. But one question has been sitting on my desk for two months, and I cannot find any information on it. Here is the question: “I was wondering if you knew what the Latin and Italian translations would be of the term blessedly cursed? I know this is not a common phrase, but I would think that there would be a translation for it.” Latin is tough, but our correspondents from Italy may know the equivalent. Their help will be greatly appreciated.

To be continued.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Jim Downs on the Emancipation Proclamation

The editors of the Oxford African American Studies Center spoke to Professor Jim Downs, author of Sick From Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, about the legacy of the Emancipation Proclamation 150 years after it was first issued. We discuss the health crisis that affected so many freedpeople after emancipation, current views of the Emancipation Proclamation, and insights into the public health crises of today.

Emancipation was problematic, indeed disastrous, for so many freedpeople, particularly in terms of their health. What was the connection between newfound freedom and health?

I would not say that emancipation was problematic; it was a critical and necessary step in ending slavery. I would first argue that emancipation was not an ending point but part of a protracted process that began with the collapse of slavery. By examining freedpeople’s health conditions, we can see how that process unfolded—we can see how enslaved people liberated themselves from the shackles of Southern plantations but then were confronted with a number of questions: How would they survive? Where would they get their next meal? Where were they to live? How would they survive in a country torn apart by war and disease?

Due to the fact that freedpeople lacked many of these basic necessities, hundreds of thousands of former slaves became sick and died.

The traditional narrative of emancipation begins with liberation from slavery in 1862-63 and follows freedpeople returning to Southern plantations after the war for employment in 1865 and then culminates with grassroots political mobilization that led to the Reconstruction Amendments in the late 1860s. This story places formal politics as the central organizing principle in the destruction of slavery and the movement toward citizenship without considering the realities of freedpeople’s lives during this seven- to eight- year period. By investigating freedpeople’s health conditions, we first notice that many formerly enslaved people died during this period and did not live to see the amendments that granted citizenship and suffrage. They survived slavery but perished during emancipation—a fact that few historians have considered. Additionally, for those that did survive both slavery and emancipation, it was not such a triumphant story; without food, clothing, shelter, and medicine, emancipation unleashed a number of insurmountable challenges for the newly freed.

Was the health crisis that befell freedpeople after emancipation any person, government, or organization’s fault? Was the lack of a sufficient social support system a product of ignorance or, rather, a lack of concern?

The health crises that befell freedpeople after emancipation resulted largely from the mere fact that no one considered how freedpeople would survive the war and emancipation; no one was prepared for the human realities of emancipation. Congress and the President focused on the political question that emancipation raised: what was the status of formerly enslaved people in the Republic?

When the federal government did consider freedpeople’s condition in the final years of the war, they thought the solution was to simply return freedpeople to Southern plantations as laborers. Yet, no one in Washington thought through the process of agricultural production: Where was the fertile land? (Much of it was destroyed during the war; and countless acres were depleted before the war, which was why Southern planters wanted to move west.) How long would crops grow? How would freedpeople survive in the meantime?

Meanwhile, a drought erupted in the immediate aftermath of the war that thwarted even the most earnest attempts to develop a free labor economy in the South. Therefore, as a historian, I am less invested in arguing that someone is at fault, and more committed to understanding the various economic and political forces that led to the outbreak of sickness and suffering. Creating a new economic system in the South required time and planning; it could not be accomplished simply by sending freedpeople back to Southern plantations and farms. And in the interim of this process, which seemed like a good plan by federal leaders in Washington, a different reality unfolded on the ground in the postwar South. Land and labor did not offer an immediate panacea to the war’s destruction, the process of emancipation, and the ultimate rebuilding of the South. Consequently, freedpeople suffered during this period.

When the federal government did establish the Medical Division of the Freedmen’s Bureau – an agency that established over 40 hospitals in the South, employed over 120 physicians, and treated an estimated one million freedpeople — the institution often lacked the finances, personnel, and resources to stop the spread of disease. In sum, the government did not create this division with a humanitarian — or to use 19th century parlance, “benevolence” — mission, but rather designed this institution with the hope of creating a healthy labor force.

So, if an epidemic broke out, the Bureau would do its best to stop its spread. Yet, as soon as the number of patients declined, the Bureau shut down the hospital. The Bureau relied on a system of statistical reporting that dictated the lifespan of a hospital. When a physician reported a declining number of patients treated, admitted, or died in the hospital, Washington officials would order the hospital to be closed. However, the statistical report failed to capture the actual behavior of a virus, like smallpox. Just because the numbers declined in a given period did not mean that the virus stopped spreading among susceptible freedpeople. Often, it continued to infect formerly enslaved people, but because the initial symptoms of smallpox got confused with other illnesses it was overlooked. Or, as was often the case, the Bureau doctor in an isolated region noticed a decline among a handful of patients, but not too far away in a neighboring plantation or town, where the Bureau doctor did not visit, smallpox spread and remained unreported. Yet, according to the documentation at a particular moment the virus seemed to dissipate, which was not the case. So, even when the government, in the shape of Bureau doctors, tried to do its best to halt the spread of the disease, there were not enough doctors stationed throughout the South to monitor the virus, and their methods of reporting on smallpox were problematic.

You draw an interesting distinction between the terms refugee and freedmen as they were applied to emancipated slaves at different times. What did the term refugee entail and how was it a problematic description?

I actually think that freedmen or freedpeople could be a somewhat misleading term, because it defines formerly enslaved people purely in terms of their political status—the term freed places a polish on their condition and glosses over their experience during the war in which the military and federal government defined them as both contraband and refugees. Often forced to live in “contraband camps,” which were makeshift camps that surrounded the perimeter of Union camps, former slaves’ experience resembled a condition more associated with that of refugees. More to the point, the term freed does not seem to jibe with what I uncovered in the records—the Union Army treats formerly enslaved people with contempt, they assign them to laborious work, they feed them scraps, they relegate them to muddy camps where they are lucky if they can use a discarded army tent to protect themselves against the cold and rain. The term freedpeople does not seem applicable to those conditions.

That said, I struggle with my usage of these terms, because on one level they are politically no longer enslaved, but they are not “freed” in the ways in which the prevailing history defines them as politically mobile and autonomous. And then on a simply rhetorical level, freedpeople is a less awkward and clumsy expression than constantly writing formerly enslaved people.

Finally, during the war abolitionists and federal officials argued over these terms and classifications and in the records. During the war years, the Union army referred to the formerly enslaved as refugees, contraband, and even fugitives. When the war ended, the federal government classified formerly enslaved people as freedmen, and used the term refugee to refer to white Southerners displaced by the war. This is fascinating because it implies that white people can be dislocated and strung out but that formerly enslaved people can’t be—and if they are it does not matter, because they are “free.”

Based on your understanding of the historical record, what were Lincoln’s (and the federal government’s) goals in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation ? Do you see any differences between these goals and the way in which the Emancipation Proclamation is popularly understood?

The Emancipation Proclamation was a military tactic to deplete the Southern labor force. This was Lincoln’s main goal—it invariably, according to many historians, shifted the focus of the war from a war for the Union to a war of emancipation. I never really understood what that meant, or why there was such a fuss over this distinction, largely because enslaved people had already begun to free themselves before the Emancipation Proclamation and many continued to do so after it without always knowing about the formal proclamation.

The implicit claim historians make when explaining how the motivation for the war shifted seems to imply that the Union soldiers thusly cared about emancipation so that the idea that it was a military tactic fades from view and instead we are placed in a position of imagining Union soldiers entering the Confederacy to destroy slavery—that they were somehow concerned about black people. Yet, what I continue to find in the record is case after case of Union officials making no distinction about the objective of the war and rounding up formerly enslaved people and shuffling them into former slave pens, barricading them in refugee camps, sending them on death marches to regions in need of laborers. I begin to lose my patience when various historians prop up the image of the Union army (or even Lincoln) as great emancipators when on the ground they literally turned their backs on children who starved to death; children who froze to death; children whose bodies were covered with smallpox. So, from where I stand, I see the Emancipation Proclamation as a central, important, and critical document that served a valuable purpose, but the sources quickly divert my attention to the suffering and sickness that defined freedpeople’s experience on the ground.

Do you see any parallels between the situation of post-Civil War freedpeople and the plights of currently distressed populations in the United States and abroad? What can we learn about public health crises, marginalized groups, etc.?

Yes, I do, but I would prefer to put this discussion on hold momentarily and simply say that we can see parallels today, right now. For example, there is a massive outbreak of the flu spreading across the country. Some are even referring to it as an epidemic. Yet in Harlem, New York, the pharmacies are currently operating with a policy that they cannot administer flu shots to children under the age of 17, which means that if a mother took time off from work and made it to Rite Aid, she can’t get her children their necessary shots. Given that all pharmacies in that region follow a particular policy, she and her children are stuck. In Connecticut, Kathy Lee Gifford of NBC’s Today Show relayed a similar problem, but she explained that she continued to travel throughout the state until she could find a pharmacy to administer her husband a flu shot. The mother in Harlem, who relies on the bus or subway, has to wait until Rite Aid revises its policy. Rite Aid is revising the policy now, as I write this response, but this means that everyday that it takes for a well-intentioned, well-meaning pharmacy to amend its rules, the mother in Harlem or mother in any other impoverished area must continue to send her children to school without the flu shot, where they remain susceptible to the virus.

In the Civil War records, I saw a similar health crisis unfold: people were not dying from complicated, unknown illnesses but rather from the failures of a bureaucracy, from the inability to provide basic medical relief to those in need, and from the fact that their economic status greatly determined their access to basic health care.

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture. It provides students, scholars and librarians with more than 10,000 articles by top scholars in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Jim Downs on the Emancipation Proclamation appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of information technologies in the legal world

The uncharitable might say that I write the same book every four years or so. Some critics certainly accuse me of having said the same thing for many years. I don’t disagree. Since the early 80s, my enduring interest has been in the ways in which technology can modernize and improve the work of the legal profession and the courts. My main underpinning conviction has indeed not changed: that legal work is document and information intensive, and that a whole host of information technologies can and should streamline and sometimes even overhaul traditional methods of practicing law and administering justice.

What have changed, of course, are the enabling technologies. When I started out on what has become a career devoted largely to legal technology, the web had not been invented, nor had tablets, handheld devices, mobile phones, and much else. As new technologies emerge, therefore, I always have a new story to tell and more evidence that suggests the legal world is shifting from being a cottage industry to an IT-enabled information sector.

The evolution of my thinking reflects my own technical interests and career activities over the years. My first work in the field, in the 1980s, focused on artificial intelligence and its potential and limitations in the law. This began in earnest with my doctoral research at Oxford University. I was interested in the possibility of developing computer systems that could solve legal problems and offer legal advice. Many specialists at the time wanted to define expert systems in law in architectural terms (by reference to what underlying technologies were being used, from rule-based systems to neural networks). I took a more pragmatic view and described these systems functionally as computer applications that sought to make scarce legal knowledge and expertise more widely available and easily accessible.

This remains my fundamental aspiration today. I believe there is enormous scope for using technology, especially Internet technology, as a way of providing affordable, practical legal guidance to non-lawyers, especially those who are not able to pay for conventional legal service. These systems may not be expert systems, architecturally-defined. Instead, they are web-based resources (such as online advisory and document drafting systems) and are delivering legal help, on-screen, as envisaged back in the 1980s.

During the first half of the 90s, while I was working in a law firm (Masons, now Pinsent Masons), my work became less academic. I was bowled over by the web and began to form a view of the way it would revolutionize the communication habits of practicing lawyers and transform the information seeking practices of the legal fraternity. I also had some rudimentary ideas about online communities of lawyers and clients; we now call these social networks. My thinking came together in the mid-1990s. I became clear, in my own mind at least, that information technology would definitely challenge and change the world of law. Most people thought I was nuts.

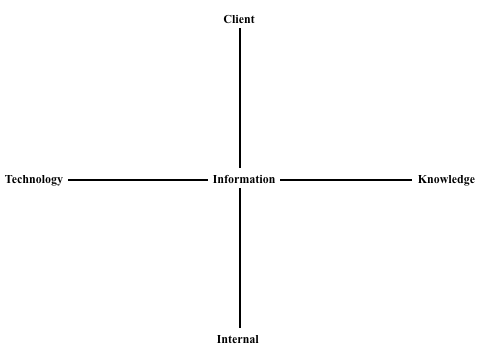

A few years later, to help put my ideas into practice, I developed what I called ‘the grid’ – a simple model that explained the inter-relationships of legal data, legal information, legal knowledge, as found within law firms and shared with clients. I had used this model quite a bit with my clients (by this time, I was working independently) and it seemed to help lawyers think through what they should be doing about IT.

In the years that followed, however, I became even more confident that the Internet was destined to change the legal sector not incrementally and peripherally but radically, pervasively, and irreversibly. But I felt that, in the early 2000s, most lawyers were complacent. Times were good, business was brisk, and the majority of practitioners could not really imagine that legal practice and the court system would be thrown into upheaval by disruptive technologies.

Then came the global recession and, in turn, lawyers became more receptive than they had been in boom times when there had been no obvious reason why they might change course. Dreadful economic conditions convinced lawyers that tomorrow would look little like yesterday.

With many senior lawyers now recognizing that we are on the brink of major change, my current preoccupation is that most law schools around the world are ignoring this future. They continue to teach law much as I was taught in the late 1970s. They are equipping tomorrow’s lawyers to be twentieth century not twenty-first century lawyers. My mission now is to help law teachers to prepare the next generation of lawyers for the new legal world.

Richard Susskind OBE is an author, speaker, and independent adviser to international professional firms and national governments. He is president of the Society for Computers and law IT adviser to the lord chief justice. Tomorrow’s Lawyers is his eighth book.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: ‘The Grid’ courtesy of Richard Susskind. Used with permission. Do not reproduce without explicit permission of Richard Susskind.

The post The future of information technologies in the legal world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers