Oxford University Press's Blog, page 982

January 29, 2013

HIV/AIDS testing: suspicion and mistrust among Baby Boomers

The seventh of February will mark the thirteenth National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day. Despite the fact that blacks make up only 14% of the US population, the CDC reports that blacks accounted for 44% of all newly reported HIV infections in 2009, the HIV infection rate among Latinos was nearly three times as high as that of whites, and 1 in 4 persons living with HIV/AIDS in the USA is an older adult (50+ years old).

The CDC reported that 1,600 White, 450 Black, and 300 Latino men aged 50 or older acquired HIV in 2009 through unprotected sex with other men. In other research conducted among senior-housing residents, investigators learned that 42% of residents had been sexually active within the previous six months. One third of the sexually active residents reported two or more partners during that period, but only 20% had regularly used condoms.

Alarmingly, older adults are prone to be disproportionately diagnosed in the late stages of HIV disease. Many older Americans who seek services in public health venues do not undergo testing for HIV infection, some due to mistrust in the government. Researchers in a recent study found among the 226 participants, 30% reported belief in AIDS conspiracy theories, 72% reported government mistrust, and 45% reported not undergoing HIV testing within the past 12 months.

Among African Americans, endorsements of AIDS conspiracy theories stem from historical experiences with racism and medical discrimination, although knowledge of African Americans’ experiences may lead members of other racial/ethnic groups to endorse such theories.

Making HIV testing routine in public health venues may be an efficient way to improve early diagnosis among at-risk older adults. Alternative possibilities include expanding HIV testing in nonpublic health venues. Finally, identifying particular sources of misinformation and mistrust would appear useful for appropriate targeting of HIV testing strategies in the future.

Key calendar dates:

7 February 2013 National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

19 May 2013 Asian Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

27 June 2013 National HIV Testing Day

15 October 2013 National Latino HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

1 December 2013 World AIDS Day

For further reading:

AIDS.gov

CDC on HIV/AIDS

“Belief in AIDS-Related Conspiracy Theories and Mistrust in the Government” by Chandra L. Ford et al. in The Gerontologist

Dr. Chandra Ford is an assistant professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at UCLA. Her areas of expertise are in the social determinants of HIV/AIDS disparities, the health of sexual minority populations and Critical Race Theory. Ford has received several competitive awards, including the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Services Award (an individual dissertation grant) from the National Institutes of Health and a North Carolina Impact Award for her research contributions to North Carolinians. Her most recent research, “Belief in AIDS-Related Conspiracy Theories and Mistrust in the Government” in The Gerontologist, is available to read for free for a limited time.

The Gerontologist, published since 1961, is a bimonthly journal (first issue in February) of The Gerontological Society of America that provides a multidisciplinary perspective on human aging through the publication of research and analysis in gerontology, including social policy, program development, and service delivery. It reflects and informs the broad community of disciplines and professions involved in understanding the aging process and providing service to older people.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post HIV/AIDS testing: suspicion and mistrust among Baby Boomers appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was Harry Hopkins?

He was a spectral figure in the Franklin Roosevelt administration. Slightly sinister. A ramshackle character, but boyishly attractive. Gaunt, pauper-thin. Full of nervous energy, fueled by caffeine and Lucky Strikes.

Hopkins was an experienced social worker, an in-your-face New Deal reformer. Yet he sought the company of the rich and well born. He was a gambler, a bettor on horses, cards, and the time of day. Between his second and third marriages he dated glamorous women — movie stars, actresses and fashionistas.

It was said that he had a mind like a razor, a tongue like a skinning knife. A New Yorker profile described him as a purveyor of wit and anecdote. He loved to tell the story of the time President Roosevelt wheeled himself into Winston Churchill’s bedroom unannounced. It was when the prime minister was staying at the White House. Churchill had just emerged from his afternoon bath, stark naked and gleaming pink. The president apologized and started to withdraw. “Think nothing of it,” Churchill said. “The Prime Minister has nothing to hide from the President of the United States.” Whether true or not, Hopkins dined out on this story for years.

On the evening of 10 May 1940 — a year and a half before the United States entered the Second World War — Roosevelt and Hopkins had just finished dinner. They were in the Oval Study on the second floor of the White House. As usual, they were gossiping and enjoying each other’s jokes and stories. Hopkins was forty-nine; the president was fifty-seven. They had known one another for a decade; Hopkins had run several of Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies that put millions of Americans to work on public works and infrastructure projects. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt had consoled Harry following the death of his second wife, Barbara, in 1937. The first lady was the surrogate mother of Hopkins’s daughter, Diana, age seven. Hopkins had become part of the Roosevelt family. He was Roosevelt’s closest advisor and friend.

The president sensed that Harry was not feeling well. He knew that Hopkins had had more than half of his stomach removed due to cancer and was suffering from malnutrition and weakeness in his legs. Roosevelt insisted that his friend spend the night.

Hopkins and Barbara Duncan

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Returning to New York after a trip to Europe in the summer of 1934.

Hopkins at the 1940 Democratic national convention

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In Chicago with daughter Diana, age seven. From left to right behind them: John Hertz, founder of the Hertz car rental empire, thoroughbred race horse owner and a close friend of Hopkins; David, Hopkins’ twenty-eight-year-old son; and Edwin Daley

Under the fourteen-inch guns of the British battleship Prince of Wales

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In August 1941, Churchill, Hopkins and British officers discuss the forthcoming meetings with President Roosevelt off the coast of Newfoundland in what became known as the Atlantic Conference.

Hopkins conferring with Roosevelt

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In the Oval Study, June 1942.

Rabat, Morocco

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After visiting American troops in Rabat, Hopkins, General Mark Clark (second from left), Roosevelt, and General George Patton (right) discuss the North Africa campaign during a lunch in the field.

Roosevelt celebrating his sixty-first birthday

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

In the roomy cabin of his Boeing Clipper with Admiral Leahy (left), Hopkins and Captain Howard Cone, the Clipper commander (right). They were on the final leg of their return from the Casablanca conference.

At the Tehran conference outside the Soviet embassy

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

December 1943, left to right: General George Marshall shaking hands with British Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Archibald Clark Kerr, Hopkins, V. N. Pavlov (Stalin’s interpreter), Joseph Stalin and Vyacheslav Molotov (with mustache).

Louise “Louie” Hopkins

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Louise “Louie” Hopkins charmed the Russian officers as she and Harry toured Berlin on their way back from Moscow in June 1945.

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-33807";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

Hopkins was the man who came to dinner and never left. For most of the next three-and-one-half years Harry would live in the Lincoln suite a few doors down the hall from the Roosevelts and his daughter would live on the third floor near the Sky Parlor. Without any particular portfolio or title, Hopkins conducted business for the president from a card table and a telephone in his bedroom.

During those years, as the United States was drawn into the maelstrom of the Second World War, Harry Hopkins would devote his life to helping the president prepare for and win the war. He would shortly form a lifelong friendship with Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine. He would even earn a measure of respect and a degree of trust from Joseph Stalin, the brutal dictator of the Soviet Union. He would play a critical role, arguably the critical role, in establishing and preserving America’s alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union that won the war.

Harry Hopkins was the pectin and the glue. He understood that victory depended on holding together a three-party coalition: Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt. This would be his single-minded focus throughout the war years. Churchill was awed by Hopkins’s ability to focus; he often addressed him as “Lord Root of the Matter.”

Much of Hopkins’s success was due to social savvy, what psychologists call emotional intelligence or practical intelligence. He knew how to read people and situations, and how to use that natural talent to influence decisions and actions. He usually knew when to speak and when to remain silent. Whether it was at a wartime conference, alone with Roosevelt, or a private meeting with Stalin, when Hopkins chose to speak, his words were measured to achieve effect.

At a dinner in London with the leaders of the British press during the Blitz, when Britain stood alone, Hopkins’s words gave the press barons the sense that though America was not yet in the war, she was marching beside them. One of the journalists who was there wrote, “We were happy men all; our confidence and our courage had been stimulated by a contact which Shakespeare, in Henry the V, had a phrase, ‘a little touch of Harry in the night.’”

Hopkins’s touch was not little nor was it light. To Stalin, Hopkins spoke po dushe (according to the soul). Churchill saw Hopkins as a “crumbling lighthouse from which there shown beams that led great fleets to harbour.” To Roosevelt, he gave his life, “asking for nothing except to serve.” They were the “happy few.” And Hopkins had made himself one of them.

David Roll is the author of The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler. He is a partner at Steptoe & Johnson LLP and founder of Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation, a public interest organization that provides pro bono legal services to social entrepreneurs around the world. He was awarded the Purpose Prize Fellowship by Civic Ventures in 2009.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Who was Harry Hopkins? appeared first on OUPblog.

How ardently I admire and love you…

On 28 January 1813, Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen was published. Originally titled ‘First Impressions’, Austen was forced to re-title it with a phrase from Frances Burney’s Cecilia after the publication of Margaret Holford’s First Impressions. We’ve paired an extract from the book with a scene from the most recent dramatization to see how Austen’s words have survived the centuries.

While settling this point, she was suddenly roused by the sound of the door bell, and her spirits were a little fluttered by the idea of its being Colonel Fitzwilliam himself, who had once before called late in the evening, and might now come to enquire particularly after her.

Click here to view the embedded video.

But this idea was soon banished, and her spirits were very differently affected, when, to her utter amazement, she saw Mr. Darcy walk into the room. In an hurried manner he immediately began an enquiry after her health, imputing his visit to a wish of hearing that she were better. She answered him with cold civility. He sat down for a few moments, and then getting up walked about the room. Elizabeth was surprised, but said not a word. After a silence of several minutes he came towards her in an agitated manner, and thus began,

‘In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.’

Elizabeth’s astonishment was beyond expression. She stared, coloured, doubted, and was silent. This he considered sufficient encouragement, and the avowal of all that he felt and had long felt for her, immediately followed. He spoke well, but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed, and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride. His sense of her inferiority––of its being a degradation––of the family obstacles which judgment had always opposed to inclination, were dwelt on with a warmth which seemed due to the consequence he was wounding, but was very unlikely to recommend his suit.

In spite of her deeply-rooted dislike, she could not be insensible to the compliment of such a man’s affection, and though her intentions did not vary for an instant, she was at first sorry for the pain he was to receive; till, roused to resentment by his subsequent language, she lost all compassion in anger. She tried, however, to compose herself to answer him with patience, when he should have done. He concluded with representing to her the strength of that attachment which, in spite of all his endeavours, he had found impossible to conquer; and with expressing his hope that it would now be rewarded by her acceptance of his hand. As he said this, she could easily see that he had no doubt of a favourable answer. He spoke of apprehension and anxiety, but his countenance expressed real security. Such a circumstance could only exasperate farther, and when he ceased, the colour rose into her cheeks, and she said,

‘In such cases as this, it is, I believe, the established mode to express a sense of obligation for the sentiments avowed, however unequally they may be returned. It is natural that obligation should be felt, and if I could feel gratitude, I would now thank you. But I cannot––I have never desired your good opinion, and you have certainly bestowed it most unwillingly. I am sorry to have occasioned pain to any one. It has been most unconsciously done, however, and I hope will be of short duration. The feelings which, you tell me, have long prevented the acknowledgment of your regard, can have little difficulty in overcoming it after this explanation.’

Mr. Darcy, who was leaning against the mantle-piece with his eyes fixed on her face, seemed to catch her words with no less resentment than surprise. His complexion became pale with anger, and the disturbance of his mind was visible in every feature. He was struggling for the appearance of composure, and would not open his lips, till he believed himself to have attained it. The pause was to Elizabeth’s feelings dreadful. At length, in a voice of forced calmness, he said,

‘And this is all the reply which I am to have the honour of expecting! I might, perhaps, wish to be informed why, with so little endeavour at civility, I am thus rejected. But it is of small importance.’

‘I might as well enquire,’ replied she, ‘why with so evident a design of offending and insulting me, you chose to tell me that you liked me against your will, against your reason, and even against your character? Was not this some excuse for incivility, if I was uncivil? But I have other provocations. You know I have. Had not my own feelings decided against you, had they been indifferent, or had they even been favourable, do you think that any consideration would tempt me to accept the man, who has been the means of ruining, perhaps for ever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?’

As she pronounced these words, Mr. Darcy changed colour; but the emotion was short, and he listened without attempting to interrupt her while she continued.

‘I have every reason in the world to think ill of you. No motive can excuse the unjust and ungenerous part you acted there. You dare not, you cannot deny that you have been the principal, if not the only means of dividing them from each other, of exposing one to the censure of the world for caprice and instability, the other to its derision for disappointed hopes, and involving them both in misery of the acutest kind.’

She paused, and saw with no slight indignation that he was listening with an air which proved him wholly unmoved by any feeling of remorse. He even looked at her with a smile of affected incredulity.

‘Can you deny that you have done it?’ she repeated.

With assumed tranquillity he then replied, ‘I have no wish of denying that I did every thing in my power to separate my friend from your sister, or that I rejoice in my success. Towards him I have been kinder than towards myself.’

Elizabeth disdained the appearance of noticing this civil reflection, but its meaning did not escape, nor was it likely to conciliate her.

‘But it is not merely this affair,’ she continued, ‘on which my dislike is founded. Long before it had taken place, my opinion of you was decided. Your character was unfolded in the recital which I received many months ago from Mr. Wickham. On this subject, what can you have to say? In what imaginary act of friendship can you here defend yourself? or under what misrepresentation, can you here impose upon others?’

‘You take an eager interest in that gentleman’s concerns,’ said Darcy in a less tranquil tone, and with a heightened colour.

‘Who that knows what his misfortunes have been, can help feeling an interest in him?’

‘His misfortunes!’ repeated Darcy contemptuously, ‘yes, his misfortunes have been great indeed.’

‘And of your infliction,’ cried Elizabeth with energy. ‘You have reduced him to his present state of poverty, comparative poverty. You have withheld the advantages, which you must know to have been designed for him. You have deprived the best years of his life, of that independence which was no less his due than his desert. You have done all this! and yet you can treat the mention of his misfortunes with contempt and ridicule.’

‘And this,’ cried Darcy, as he walked with quick steps across the room, ‘is your opinion of me! This is the estimation in which you hold me! I thank you for explaining it so fully. My faults, according to this calculation, are heavy indeed! But perhaps,’ added he, stopping in his walk, and turning towards her, ‘these offences might have been overlooked, had not your pride been hurt by my honest confession of the scruples that had long prevented my forming any serious design. These bitter accusations might have been suppressed, had I with greater policy concealed my struggles, and flattered you into the belief of my being impelled by unqualified, unalloyed inclination; by reason, by reflection, by every thing. But disguise of every sort is my abhorrence. Nor am I ashamed of the feelings I related. They were natural and just. Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your connections? To congratulate myself on the hope of relations, whose condition in life is so decidedly beneath my own?’

Elizabeth felt herself growing more angry every moment; yet she tried to the utmost to speak with composure when she said,

‘You are mistaken, Mr. Darcy, if you suppose that the mode of your declaration affected me in any other way, than as it spared me the concern which I might have felt in refusing you, had you behaved in a more gentleman-like manner.’

She saw him start at this, but he said nothing, and she continued, ‘You could not have made me the offer of your hand in any possible way that would have tempted me to accept it.’

Again his astonishment was obvious; and he looked at her with an expression of mingled incredulity and mortification. She went on.

‘From the very beginning, from the first moment I may almost say, of my acquaintance with you, your manners impressing me with the fullest belief of your arrogance, your conceit, and your selfish disdain of the feelings of others, were such as to form that ground-work of disapprobation, on which succeeding events have built so immoveable a dislike; and I had not known you a month before I felt that you were the last man in the world whom I could ever be prevailed on to marry.’

‘You have said quite enough, madam. I perfectly comprehend your feelings, and have now only to be ashamed of what my own have been. Forgive me for having taken up so much of your time, and accept my best wishes for your health and happiness.’

And with these words he hastily left the room, and Elizabeth heard him the next moment open the front door and quit the house. The tumult of her mind was now painfully great. She knew not how to support herself, and from actual weakness sat down and cried for half an hour. Her astonishment, as she reflected on what had passed, was increased by every review of it. That she should receive an offer of marriage from Mr. Darcy! that he should have been in love with her for so many months! so much in love as to wish to marry her in spite of all the objections which had made him prevent his friend’s marrying her sister, and which must appear at least with equal force in his own case, was almost incredible! it was gratifying to have inspired unconsciously so strong an affection. But his pride, his abominable pride, his shameless avowal of what he had done with respect to Jane, his unpardonable assurance in acknowledging, though he could not justify it, and the unfeeling manner in which he had mentioned Mr. Wickham, his cruelty towards whom he had not attempted to deny, soon overcame the pity which the consideration of his attachment had for a moment excited…

Pride and Prejudice has delighted generations of readers with its unforgettable cast of characters, carefully choreographed plot, and a hugely entertaining view of the world and its absurdities. With the arrival of eligible young men in their neighborhood, the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet and their five daughters are turned inside out and upside down. Pride encounters prejudice, upward-mobility confronts social disdain, and quick-wittedness challenges sagacity, as misconceptions and hasty judgements lead to heartache and scandal, but eventually to true understanding, self-knowledge, and love. In this supremely satisfying story, Jane Austen balances comedy with seriousness, and witty observation with profound insight.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics onTwitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post How ardently I admire and love you… appeared first on OUPblog.

The Subject is Jazz

The New Year is a time of looking forward to the future and back to the past. Looking back, last year witnessed the death of Dave Brubeck, one of the all time great jazz musicians. Brubeck became famous through his live performances and his recordings, especially the seminal Time Out album released in 1958. But he also became famous through his many appearances on American and international television, beginning with The Colgate Comedy Hour in 1955, and appearing on variety shows such as The Steve Allen Plymouth Show (1958), The Timex All-Star Jazz Show (1957), and The Ed Sullivan Show (1955, 1960, 1962). As his fame grew, Brubeck also became the subject of several TV documentaries, including prestigious programs like The Twentieth Century (1961) and The Bell Telephone Hour (1968). He was also an honored guest in the few exclusively jazz programs that aired in the 1960s. He appeared on Jazz 625 in 1964 and made several appearances on Jazz Casual, an occasional series that ran on the National Educational Network from 1961-68.

Here’s the Brubeck Quartet performing for a broadcast of Jazz Casual in 1961.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Brubeck made many more TV appearances throughout the world in the 1960s and 1970s, many of which can be seen on YouTube.

As important as Brubeck’s TV appearances were, perhaps no one furthered the cause of jazz on television more than Billy Taylor, who also died recently in 2010. After graduating college in 1942, Taylor got his professional start with Ben Webster’s Quartet on New York’s famed 52nd Street. He then served as the house pianist at the legendary club Birdland, where he performed with such celebrated masters as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis. He went on to receive a masters and doctor’s degree in music education at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and served as Duke Ellington Fellow at Yale. He divided his career as performer, writer, jazz advocate, and educator for the remainder of his life.

Taylor’s contributions to television music were manifold. He was the music director and band leader for The David Frost Show from 1969-72, becoming the first African American musician to hold that position on a TV talk show. He served as “Jazz and Modern Music Correspondent” for CBS News Sunday Morning from 1981-2002. He also was a contributor to many jazz documentaries, notably for Louis Armstrong (1971) and Duke Ellington (1981, 2000).

Taylor made his TV debut on the Steve Allen’s Tonight! show in 1956. Next, he appeared on Jazz Party in 1958. That year proved pivotal, as Taylor was asked to be music director for a new TV series, The Subject is Jazz, produced by NBC.

Before his death, Dr. Taylor was interviewed for an upcoming book of his memoirs written by Teresa Reed, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor (Indiana University Press). Taylor had this to say about the program:

“A second opportunity in 1958 came by way of Marshall Stearns. By that time, his deep interest in jazz had turned to television, and in collaboration with Leonard Feather, he came up with the idea to do a series of thirteen shows as part of a program called The Subject is Jazz. Although jazz had been on radio for decades, The Subject is Jazz would be the very first program of its type to come to television. Stearns and Feather were both writers, however, and neither knew a thing about the practical aspects of musical direction or doing a television show. So it was for this purpose that they hired me. Having experienced rejection from MENC, it was crucial to me that The Subject is Jazz develop into a high-quality, educational show. The Subject is Jazz was distributed through NBC network facilities to educational TV stations. Although a variety of different musicians performed on the show, my basic combo included Osie Johnson on drums, Eddie Safranski on bass, Mundell Lowe on guitar, Tony Scott on clarinet, Jimmy Cleveland on trombone, and Carl (later known as “Doc”) Severinsen on trumpet.

“The show featured some great music and stimulating conversations with people like Duke Ellington, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, all of whom were serious connoisseurs of jazz. But a major flaw was the show’s dry, stoic, and overly academic presentation. There were lots of people who knew and loved the music, people who would have made excellent commentators for the show… Rather than get some known radio personality, the producer hired Gilbert Seldes, a Harvard-trained cultural critic who read to the television audience from his stack of handheld notes. I knew that the audience for The Subject is Jazz was vastly different from the audience I typically encountered while I was performing in clubs. Gilbert Seldes was a conservative, grandfatherly type in his mid-sixties who sported a professorial bowtie and spoke in a sort of scholarly monotone, using carefully measured language as one does while delivering a lecture. He was an intellectual speaking to a Saturday-afternoon television audience of intellectuals who wanted to understand the music with their minds as much as they enjoyed it with their ears and hearts. Working in this context, it was my job to combine clear, articulate answers to Seldes’s questions with musical demonstrations of whatever I was explaining.

“By today’s more sophisticated, high-tech standards, The Subject is Jazz may seem like a very primitive and ‘square’ attempt at using mass media to educate the public about the music. Yet, in some ways, the show was quite ahead of its time. During the thirteen-week run of The Subject is Jazz I also had an opportunity to perform some of my own compositions… The last episode featured a composition that was my tribute to Charlie Parker, titled “Early Bird.”” (Teresa Reed, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor, p.137-38)

Here is a video of that last episode:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television. His thanks to Dr. Teresa Reed, Professor of Music at the University of Tulsa, for this “sneak peek” at her upcoming book, The Jazz Life of Dr. Billy Taylor. Look for it on bookshelves soon!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Subject is Jazz appeared first on OUPblog.

January 28, 2013

Happy Birthday, Pride and Prejudice! Would you find me a date?

Two hundred years after the initial publication of Pride and Prejudice, commodities marketed to Janeites overwhelmingly emphasize Jane Austen’s powers as an advisor. Shoppers can choose among volumes called Finding Mr. Darcy: Jane Austen’s Rules for Love or Dating Mr. Darcy: The Smart Girl’s Guide to Sensible Romance; The Jane Austen Guide to Life, Happily Ever After, Modern Life’s Dilemmas, Dating, Good Manners, and coming soon, Thrift; older miniatures such as Jane Austen’s Little Advice Book, Jane Austen’s Little Instruction Book, Jane Austen’s Universal Truths; books called The Jane Austen Companion to Love and to Life but also the 2013 Jane Austen Companion to Life mini wall calendar; and works of fiction masquerading as advice, with titles such as The Jane Austen Marriage Manual, Dear Jane: A Heroine’s Guide to Life and Love, What Would Jane Austen Do?, and even Jane Austen Ruined My Life: a novel. This visibility of her so-called guidance helps to reveal how attractively Austen perfected the didactic tradition of the eighteenth-century novel. Austen’s predecessor Samuel Richardson aspired to be a guide for his readers on matters of romance and conduct, but no one today looks for counsel in A Collection of such of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Cautions, Aphorisms, Reflections, and Observations contained in the History, as are presumed to be of general Use and Service or any of the other volumes of extracts he compiled from his novels. Meanwhile, a drawback of Austen’s marketability as an advisor is that it risks branding Austen’s admirers as sexually and socially desperate. So at least my students tell me. Far from the companion who guarantees one’s literary distinction, Austen the mentor can be a style-cramper for young women in just the way that Mrs. Bennet is for Elizabeth Bennet: association with her suggests that one lacks a romantic partner and is willing to make an unseemly effort to get one.

What I find remarkable in this latest twist to Austen’s reception is how precisely yet incompletely it follows cues set up in the opening sentence of Austen’s best-loved novel. There, Austen takes Richardson’s notion that reading can turn things around for your romantic life and gives it a utopian dimension, offering up a narrator who can help readers not just with counsel but with limitless powers for active intervention in the world. When Pride and Prejudice’s narrator adopts what initially seems to be the tone of an advising aunt to give the reader’s implicit antecedent question, “will my beloved ever propose to me?” the coy but distinctly encouraging answer, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” she offers to write us the love story we want through the sheer force of her magical thinking and ours: her control over the fictional world will extend into our world and dictate the behavior of that particular man whose name we have mentally substituted for the general term, “single man.” By an entirely different logic, the words “universally acknowledged” hint that the narrator is prepared to extort a proposal for the reader from the man in question by using group pressure against him. In a society ruled by the gentleman’s code requiring that if it is generally supposed that a man will marry a particular, willing woman, he is honor-bound to propose to her, power to make matches goes to anyone who can persuasively articulate universal opinion, as the narrator here proves that she can do. The reader’s romantic hopes get an additional boost from the sanguine expectations of others—how could the narrator and a whole universe of acknowledgers be mistaken?—and from the sense that, since she herself acknowledges her beloved’s want of a wife, she belongs to a prestigious group, one whose alliance with herself can only further her chances with her beloved.

What I find remarkable in this latest twist to Austen’s reception is how precisely yet incompletely it follows cues set up in the opening sentence of Austen’s best-loved novel. There, Austen takes Richardson’s notion that reading can turn things around for your romantic life and gives it a utopian dimension, offering up a narrator who can help readers not just with counsel but with limitless powers for active intervention in the world. When Pride and Prejudice’s narrator adopts what initially seems to be the tone of an advising aunt to give the reader’s implicit antecedent question, “will my beloved ever propose to me?” the coy but distinctly encouraging answer, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” she offers to write us the love story we want through the sheer force of her magical thinking and ours: her control over the fictional world will extend into our world and dictate the behavior of that particular man whose name we have mentally substituted for the general term, “single man.” By an entirely different logic, the words “universally acknowledged” hint that the narrator is prepared to extort a proposal for the reader from the man in question by using group pressure against him. In a society ruled by the gentleman’s code requiring that if it is generally supposed that a man will marry a particular, willing woman, he is honor-bound to propose to her, power to make matches goes to anyone who can persuasively articulate universal opinion, as the narrator here proves that she can do. The reader’s romantic hopes get an additional boost from the sanguine expectations of others—how could the narrator and a whole universe of acknowledgers be mistaken?—and from the sense that, since she herself acknowledges her beloved’s want of a wife, she belongs to a prestigious group, one whose alliance with herself can only further her chances with her beloved.

Of course, the trap laid for that straight, nubile woman and every reader willing to identify with her soon appears. The next sentences of the novel oblige the reader to recognize that the universe whose apparent prestige was the basis for her romantic optimism has boundaries: standing outside it are the single man himself, whose “feelings or views” may, the narrator warns, be “little known”; the intelligent Mr. Bennet, who sarcastically asks whether marrying a Bennet daughter was Mr. Bingley’s “design in coming here”; and indeed the narrator, who abruptly revokes her opening promises, prepares to draw a mustache on her once-flattering portrait of the reader, and transforms her own persona. Suddenly, the advisory figure to whom the reader confessed the name of her beloved no longer looks like that comfortable confidante, benign and wise, who was ready to grant the reader’s desire and testify to the dignity of that desire, but rather like Mrs. Bennet: liable to misjudge the desires of eligible men, unable to tell the difference between a vulgar local community and the world, abjectly desperate to find her protégée a husband, likely to sink rather than raise the reader’s social status and marriageability. Having unwarily accepted the matchmaking services of this Mrs. Bennet-like figure, the reader now seems to stand condemned before the new, Mr. Bennet-like narrator coming into view, who articulated that opening sentence not to endorse its assurances but to ridicule them.

By taking Austen as fairy godmother or pathetic yenta, the Janeite and anti-Janeite camps ignore this last transformation in the narrator. Perhaps their doing so represents an insight: after all, the narrator soon eases the pressure of her threatened scorn by offering up for our identification the magnificent Elizabeth Bennet, who demolishes the law that desire for a husband makes a woman contemptible. That Pride and Prejudice, with its wealth of generalizations about love, inspires so many readers with the hopeful, even euphoric eagerness for rules that it sends up in Mary Bennet, Mr. Collins, and the reader of its opening sentences suggests that Austen retained a fundamental allegiance to advice-book tradition she knew so well how to mock.

Sarah Raff is Associate Professor of English at Pomona College and has written for Publishers Weekly. Her upcoming book about Jane Austen’s erotic evolution will be published by Oxford in September 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) The submissive reader by Rene Magritte, 1928 via wikipaintings.org. (2) Altered version of Dear Abby star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Original photo by Ben McCune, 2006. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Happy Birthday, Pride and Prejudice! Would you find me a date? appeared first on OUPblog.

The global data privacy power struggle

Tension between different regulatory systems has long existed in certain areas (think of the disagreements between EU and US competition regulators regarding the aborted GE-Honeywell merger in the early 2000s). A similar power struggle is currently underway between different legal regimes regulating the collection, processing, and transfer of personal data (variously referred to in different legal systems as “data protection”, “data privacy”, or “information privacy” law), one that will shape the world in the 21st century.

Data protection law has traditionally been viewed as a dreary subject of interest only to a few specialists. But whether it involves filling out government forms, purchasing items on the web, communicating with friends and relatives online, or checking in for a flight, almost every activity we engage in nowadays involves the processing of personal data. The growing importance of data processing is reflected in the large number of countries (approximately 100) around the world that have enacted data protection laws, and the countries and international organisations (including the European Union, the OECD, and the United States) that are currently in the process of revising them to meet the challenges posed by globalisation and the rapid growth of the Internet.

Data protection law has traditionally been viewed as a dreary subject of interest only to a few specialists. But whether it involves filling out government forms, purchasing items on the web, communicating with friends and relatives online, or checking in for a flight, almost every activity we engage in nowadays involves the processing of personal data. The growing importance of data processing is reflected in the large number of countries (approximately 100) around the world that have enacted data protection laws, and the countries and international organisations (including the European Union, the OECD, and the United States) that are currently in the process of revising them to meet the challenges posed by globalisation and the rapid growth of the Internet.

Much personal data routinely flows across national borders, and the same data processing may result in the application of multiple laws. The ease with which data flows internationally also means that data privacy law has become a point of competition between different legal systems, with each one striving to achieve the seemingly impossible goal of simultaneously protecting the privacy of individuals, striking a balance between privacy and other important values (e.g., public security), and furthering economic growth.

This competition has been most pronounced between the European Union, which has recently asserted that other countries should follow the “gold standard” of its data protection legislation, and the United States, which believes that its system is even better. Such international regulatory spats illustrate that nations too often view the subject largely as a way to score political points, and that they have failed to grasp some basic facts about the processing of personal data:

Protection of data privacy is not just a transatlantic issue. Data protection laws have been enacted all over the world, including by regional organizations (APEC, ECOWAS, and others) and dozens of nations in Africa, Latin America, and Asia.

It is also not just an online issue. Nearly every economic and social activity nowadays involves the processing of personal data, including the most basic ones. Too often regulatory attention focuses on the online “flavour of the month” (e.g., social networks, search engines, etc.), and fails to recognize that data processing has become embedded in every aspect of society.

And it is not just an economic issue, but one that can help further important developmental goals as well. For example, the UN Secretary General has begun an initiative called “Global Pulse” involving projects such as the use of data analytics to better understand the global state of various infectious diseases, and using a centralized text messaging system to allow mobile phone users to report on people trapped under buildings following an earthquake, among others. Data protection law is currently not conceived to facilitate the large-scale use of data mining for purposes related to development, public health, and similar goals, but these uses will greatly increase in coming years, and will challenge our assumptions about the purposes and structure of regulation.

Part of the problem is that while data protection and privacy issues have global ramifications, the legal framework for them is still very much a matter of local or, at best, regional regulation. While some regional organizations (in particular the Council of Europe) are attempting to become more global, there are substantial differences in the way the subject is viewed in different countries and legal systems. In contrast to some other areas of the law, there is also a lack of legal instruments and institutions of a global scope covering privacy and data protection.

Legal regulation of data processing often stands in tension with economic pressures that encourage the processing and transfer of personal data, and political pressures that inhibit the development of coordinated and coherent regulation. States are only too happy to adopt legal requirements for the private sector that they are unwilling to comply with themselves (e.g., with regard to data processing for law enforcement purposes), and technology to process personal data advances faster than the law can keep up with.

From being considered a niche area, data protection law has evolved to the point that it is hard to find areas of human endeavour that it does not concern. The way that the struggles over data protection are resolved in the coming years will determine the kind of world we live in, and the kind of Internet we have.

Dr. Christopher Kuner is editor-in-chief of the journal International Data Privacy Law. He is author of European Data Protection Law: Corporate Compliance and Regulation, and the forthcoming book Transborder Data Flow Regulation and Data Privacy Law in which he elaborates some of the topics discussed here. Dr. Kuner is Senior Of Counsel at , and an Honorary Fellow of the Centre for European Legal Studies, University of Cambridge.

Combining thoughtful, high level analysis with a practical approach, International Data Privacy Law has a global focus on all aspects of privacy and data protection, including data processing at a company level, international data transfers, civil liberties issues (e.g., government surveillance), technology issues relating to privacy, international security breaches, and conflicts between US privacy rules and European data protection law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Laptop keyboard with fingerprint enlarged by magnifying glass – computer criminality concept. Image by Jirsak, iStockphoto.

The post The global data privacy power struggle appeared first on OUPblog.

Why are married men working so much?

If you become wealthier tomorrow, say through winning the lottery, would you spend more or less working than you do now? Standard economic models predict you would work less. In fact a substantial segment of American society has indeed become wealthier over the last 40 years — married men. The reason is that wives’ earnings now make a much larger contribution to household income than in the past. However married men do not work less now on average than they did in the 1970s. This is intriguing because it suggests there is something important missing in economic explanations of the rise in labor supply of married women over the same period.

One possibility is that what we are seeing here are the aggregate effects of bargaining between spouses. This is plausible because there was a substantial narrowing of the male-female wage gap over the period. The ratio of women’s to men’s average wages; starting from about 0.57 in the 1964-1974 period, rose rapidly to 0.78 in the early 1990s. Even if we smooth out the fluctuations, the graph shows an average ratio of 0.75 in the 1990s, compared to 0.57 in the early 1970s.

The closing of the male-female wage gap suggests a relative improvement in the economic status of non-married women compared to non-married men. According to bargaining models of the household, we should expect to see a better deal for wives—control over a larger share of household resources – because they don’t need marriage as much as they used to. We should see that the share of household wealth spent on the wife increases relative to that spent on the husband.

Bargaining models of household behavior are rare in macroeconomics. Instead, the standard assumption is that households behave as if they were maximizing a fixed utility function. Known as the “unitary” model of the household, a basic implication is that when a good A becomes more expensive relative to another good B, the ratio of A to B that the household consumes should decline. When women’s wages rose relative to men’s, that increased the cost of wives’ leisure relative to that of husbands. The ratio of husbands’ leisure time to that of wives should therefore have increased.

In the bargaining model there is an additional potential effect on leisure: as the share of wealth the household spends on the wife increases, it should spend more on the wife’s leisure. Therefore the ratio of husband’s to wife’s leisure could increase or decrease, depending on the responsiveness of the bargaining solution to changes in the relative status of the spouses as singles.

To measure the change in relative leisure requires data on unpaid work, such as time spent on grocery shopping and chores around the house. The American Time-Use Survey is an important source for 2003 and later, and there also exist precursor surveys that can be used for some earlier years. The main limitation of these surveys is that they sample individuals, not couples, so one cannot measure the leisure ratio of individual households. Instead measurement consists of the average leisure of wives compared to that of husbands. The paper also shows the results of controlling for age and education. Overall, the message is clear; the relative leisure of married couples was essentially the same in 2003 as in 1975, about 1.05.

One can explain the stability of the leisure ratio through bargaining; the wife gets a higher share of the marriage’s resources when her wage increases, and this offsets the rise in the price of her leisure. This raises a set of essentially quantitative questions: Suppose that marital bargaining really did determine labor supply how big are the mistakes one would make in predicting labor supply by using a model without bargaining? To provide answers, I design a mathematical model of marriage and bargaining to resemble as closely as possible the ‘representative agent’ of canonical macro models. I use the model to measure the impact on labor supply of the closing of the gender wage gap, as well as other shocks, such as improvements to home -production technology.

People in the model use their share of household’s resources to buy themselves leisure and private consumption. They also allocate time to unpaid labor at home to produce a public consumption good that both spouses can enjoy together. We can therefore calibrate the model to exactly match the average time-allocation patterns observed in American time-use data. The calibrated model can then be used to compare the effects of the economic shocks in the bargaining and unitary models.

The results show that the rising of women’s wages can generate simultaneously the observed increase in married women’s paid work and the relative stability of that of the husbands. Bargaining is critical however; the unitary model, if calibrated to match the 1970s generates far too much of an increase in the wife’s paid labor, and far too large a decline in that of the men; in both cases, the prediction error is on the order of 2-3 weekly hours, about 10% of per-capita labor supply. In terms of aggregate labor, the error is much smaller because these sex-specific errors largely offset each other.

The bottom line therefore is that if, as is often the case, the research question does not require us to distinguish between the labor of different household or spouse types, then it may be reasonable to ignore bargaining between spouses. However if we need to understand the allocation of time across men and women, then models with bargaining have a lot to contribute.

John Knowles is a professor of economics at the University of Southampton. He was born in the UK and schooled in Canada, Spain and the Bahamas. After completing his PhD at the University of Rochester (NY, USA) in 1998, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and returned to the UK in 2008. His current research focuses on using mathematical models to analyze trends in marriage and unmarried birth rates in the US and Europe. He is the author of the paper ‘Why are Married Men Working So Much? An Aggregate Analysis of Intra-Household Bargaining and Labour Supply’, published in The Review of Economics Studies.

January 27, 2013

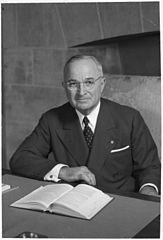

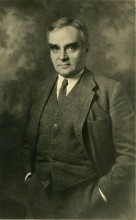

A letter from Harry Truman to Judge Learned Hand

Learned Hand was born on this day in 1872. In a letter dated 15 May 1951, Judge Learned Hand wrote President Harry S. Truman to declare his intention to retire from “regular active service.” President Truman responded to Hand’s news with a letter praising his service to the country. These letters are excerpted from Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand, edited by Constance Jordan.

To Judge Learned Hand

May 23, 1951

The White House, Washington, D.C.

Your impending retirement fills me with regret, which I know is shared by the American people. It is hard to accept the fact that after forty-two years of most distinguished service to our Nation, your activities are now to be narrowed. It is always difficult for me to express a sentiment of deep regret; what makes my present task so overwhelming is the compulsion I feel to attempt, on behalf of the American people, to give in words some inkling of the place you have held and will always hold in the life and spirit of our country.

Your profession has long since recognized the magnitude of your contribution to the law. There has never been any question about your preeminent place among American jurists – indeed among the nations of the world. In your writings, in your day-to-day work for almost half a century, you have added purpose and hope to man’s quest for justice through the process of law. As judge and philosopher, you have expressed the spirit of America and the highest in civilization which man has achieved. America and the American people are the richer because of the vigor and fullness of your contribution to our way of life.

We are compensated in part by the fact that you are casting off only a part of the burdens which you have borne for us these many years, and by our knowledge that you will continue actively to influence our life and society for years to come. May you enjoy many happy years of retirement, secure in the knowledge that no man, whatever his walk of life, has ever been more deserving of the admiration and the gratitude of his country, and indeed of the entire free world.

Very sincerely yours, Harry S. Truman

Hand immediately responded to the President’s letter:

To President Harry S. Truman

May 24, 1951

Dear Mr. President:

Dear Mr. President:

Your letter about my retirement quite overwhelms me. I dare not believe that it is justified by anything which I have done, yet I cannot but be greatly moved that you should think that it is. The best reward that anyone can expect from official work is the approval of those competent to judge who become acquainted with it; your words of warm approval are much more than I could conceivably have hoped to receive. I can only tell you of my deep gratitude, and assure you that your letter will be a possession for all time for me and for those who come after me.

Respectfully yours, LEARNED HAND

The letters above were excerpted from Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand, edited by Constance Jordan, a retired professor of comparative literature and also Hand’s granddaughter. Learned Hand served on the United States District Court and is commonly thought to be the most influential justice never to serve on the Supreme Court. He corresponded with people in different walks of life, some who were among his friends and acquaintances, others who were strangers to him.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Harry S Truman. US National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Judge Learned Hand circa 1910. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A letter from Harry Truman to Judge Learned Hand appeared first on OUPblog.

Obama’s Second Inaugural Address

Conservatives hate it; liberals love it. His Second Inaugural Address evinces Barack Obama coming into his own, projecting himself unvarnished and real before the world. No more elections for him, so also less politics. He is number 17 in the most exclusive club in America — presidents who get to serve a second term. Yes, there’s still the bonus of a legacy. But the legacy-desiring second-term president would just sit back and do no harm, rather than put himself out there for vociferous battles to come.

For better or for worse, Barack Obama believes that the constitutional compact from whence he derives the fullness of his authority gives him a responsibility. He believes that the framers of the Constitution “gave to us a republic, a government of, and by, and for the people. Entrusting each generation to keep safe our founding creed.” But he did not mean that he was an originalist, or a “constitutional conservative.” Indeed, the very opposite is true. Obama believes that the “founding creed” is no less than this: “we have always understood that when times change, so must we, that fidelity to our founding principles requires new responses to new challenges.” Originalism means change, he is telling us.

This is a president no longer prepared to dally, or to punt on his liberal beliefs. “The commitments we make to each other through Medicare and Medicaid and Social Security, these things do not sap our initiative. They strengthen us,” he said. “Our journey is not complete until our gay brothers and sisters are treated like anyone else under the law,” he also proclaimed. In his mind, there is no need to coddle the political right anymore, and he believes that the truth as he tells it will set us free.

So unreserved was Obama’s conviction that he took the sacred line of modern conservatism, “We the people declare today that the most evident of truth that all of us are created equal — is the star that guides us still” and turned it into the most liberal of philosophies, that “our individual freedom is inextricably bound to the freedom of every soul on Earth.” Obama never really had much of a stomach for unadulterated libertarianism; in his heart of hearts, this former community organizer is a communitarian. This is why he cited “We the People” five times in his address.

Call Obama liberal, or call him correct; the point is half the country does not agree, and there are tough wars to come. That Obama has been so uncharacteristically upfront about his intentions signals, though, his belief that the national political tide has turned. That on gay rights, immigration, and so forth, either because of his electoral mandate or the changing demographics of the country, he believes he holds the upper hand.

And however short his second-term “honeymoon,” I think he does. Had Obama not been re-elected, his first term might have been construed as a fluke; a bit of electoral charity from a guilt-ridden America willing to give a half-African-Anerican a chance to deliver at the White House. But Barack Obama was re-elected by a vote differential of 5 million. Only the most measly of partisan spirits will deride this victory, and deny Obama the honeymoon that he justly earned.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Obama’s Second Inaugural Address appeared first on OUPblog.

The curious appeal of Alice

By Peter Hunt

The recent appearance of Fifty Shades of Alice, which is (I am told) about a girl who follows a vibrating white rabbit down a hole, made me reflect, not for the first time, that children’s literature is full of mysteries.

For example, how did a satire on literary fashions in the early 1900s, centred on the retreatist, misogynistic fears of middle-aged men ever become a cosy national icon?* How did a series of novels satirising the British middle-class, and closely based on the 19th-century mores of the public-school system (which scarcely exists elsewhere) become the world’s biggest seller?** Or how did an anti-heroic, anti-empire broadside, whose narrator is corrupt and whose most memorable (and most admired) character is a brutal multi-murderer, become a classic for boys?*** Perhaps most curious of all, how did an intensely personal present from an eccentric bachelor to a little girl, packed with intimate in-jokes, ever come to be translated into most of the languages on earth?

Since its first translation in 1869, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland has become, in Ireland Eibhlís i dTír na Niongantas, in Denmark, Maries haendelser I vidunderlandet, in Finland, Liisan seikkailut ihmemaailmassa, in Iceland, Lísa í undralandi, and in Wales Anturiaethau Alys yng Ngwlad Hud and Alys yn nhir swyn. Alis, Alisa, Alicja, Alicji, Alenka, Elenkine, Elisi, Elsje, or Else, has her adventures im Wunderland, du pays des merveilles, nel paese delle meraviglie, csodaországban, I eventyrland, w krainie czarów, ülkesinde, or, in Slovak, divotvornej krajine (literally, the mad country). And, perhaps most improbably, the native peoples of northern South Australia, whose lands include Uluru, or Ayer’s Rock, and whose language is Pitjantjatjara, can read about Alitjinja ngura tjukurtjarangka (Alitji in the Dreamtime). The book was translated into Russian by Vladimir Nabokov, a link that has not escaped critics; an Italian edition in 1962, La meravigliosa Alice was subtitled Una lucida invenzione, la creazione poetica di una ‘lolita’ vittoriana.

Like other great pieces of popular culture, it has proved to be highly adaptable: Alice has appeared in Blufferland, Dairyland, Cookery-land, Blunderland, Virusland, Orchestralia, Police Court Land, Plunderland, Puzzle-land, Jurisprudencia, Debitland, Llechweddland (near Blaenau Ffestiniog in Wales) and even in Stitches (a book of patterns). And the title or the structure or the characters of the book have been used for political satire (Edward Hope’s Alice in the Delighted States (1928)), for propaganda (James Dyrenforth’s Adolf in Blunderland (1940)) and as a reference in conspiracy theory (David Icke’s Alice in Wonderland and the World Trade Center Disaster. Why the Official Story of 9/11 is a Monumental Lie (2002)).

A dress in the style of that worn in the 1972 film ‘Alice in Wonderland’ featuring Fiona Fullerton in the title role. Dress designed, owned and photographed by Birgit Compton. Public domain.

Of course, some of this can be accounted for by the literary snowball effect – once a book is famous, it stays famous, with the help of royalty-free publishing and marketing – but how did it become famous in the first place? And even more mystifying, how did it become internationally famous?

Conventional wisdom attributes the initial success of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to the historical moment. For the child readers of 1865 it must have made a liberating change from the moralising tone of almost all the children’s books that preceded it. Carroll was, rather anarchically, slyly supporting the rebellious but frustrated nature of a real little girl. All the characters that Alice meets are adult (and mad), and the book is full of parodies of the pious verses that children were obliged to learn. And perhaps he was also slyly supporting rebellious but frustrated adults (who, after all bought the book for their children): to them it must have appeared as a refreshingly sceptical take on life in an age of increasing scepticism.

Its international success is more difficult to explain; it is, after all, an unmistakably British, or English book — a characteristic perhaps as likely to alienate as attract overseas readers. It is a world revolving around endless tea-parties, garden parties, a savage game of croquet (the All England Croquet Club was established in 1868), river-bank picnics, and comfortable, kitten-filled nurseries. Then there are the perhaps quintessentially English eccentrics: the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, the Mock Turtle, the homicidal Queen, the arrogantly ignorant Duchess, the servile courtiers, the mad jurymen — do these ingredients add up to something that could not but be English? And most of all, passing unscathed through all the lunacy, is the figure of Alice, polite, well-bred, ladylike. No Pinocchio or Jo March is she!

The answer, if there is an answer, may lie in the fact that for any reader, of any generation in any place, Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland is disturbing. It is a seemingly endless series of semantic Chinese boxes, emotional and intellectual, of precise and general application. It is never quite what it seems — it is anything but nonsense — and why it ever became to be considered as such is perhaps the biggest mystery of all.

Peter Hunt was the first specialist in Children’s Literature to be appointed full Professor of English in a British university. Peter Hunt has written or edited eighteen books on the subject of children’s literature, including An Introduction to Children’s Literature (OUP, 1994) and has edited Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Wind in the Willows, Treasure Island and The Secret Garden for Oxford World’s Classics. 27 January 2013 is the 181st birthday of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (strictly speaking, Lewis Carroll will be 157 on 1 March, the day in 1856 when the name of Dodgson‘s alter ego was agreed upon).

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

*The Wind in the Willows

**Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone and series

***Treasure Island

The post The curious appeal of Alice appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers