Oxford University Press's Blog, page 986

January 16, 2013

The two funerals of Thomas Hardy

By Phillip Mallett

At 2.00 pm on Monday 16 January 1928, there took place simultaneously the two funerals of Thomas Hardy, O.M., poet and novelist. His brother Henry and sister Kate, and his second wife Florence, had supposed that he would be buried in Stinsford, close to his parents, and beneath the tombstone he had himself designed for his first wife, Emma, leaving space for his own name to be added. But within hours of his death on 11 January, Sydney Cockerell and James Barrie had established themselves at his home at Max Gate, and determined that he should be laid in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey. Trapped between family pieties and what the men of letters bullyingly assured her were the claims of ‘the nation’, the exhausted Florence agreed to a compromise as grotesque as anything in Hardy’s fiction: his ashes were be buried in the Abbey, together with a spadeful of Dorset earth, and his heart in Stinsford churchyard.

The Dorset funeral was a quiet affair. Kate, who went to the Abbey, while Henry attended in Stinsford, recorded that ‘the good sun shone & the birds sang & everything was done simply, affectionately & well.’ That at the Abbey was a national event. Crowds waited outside in the rain to file past the open grave; Stanley Baldwin and Ramsay MacDonald were among the pall bearers. So too were Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw, as ill-matched in their height as in their politics; according to Shaw’s secretary, Blanche Patch, Kipling shook hands ‘hurriedly, and turned away as if from the Evil One’. Hardy had once proposed the creation of ‘a heathen annexe’, suitable for non-believers like Swinburne, Meredith and himself, but T. E. Lawrence, absent in Karachi, thought he might have been amused at his belated capture by Church and Establishment: ‘Hardy was too great to be suffered as an enemy to their faith: so he must be redeemed.’

The Dorset funeral was a quiet affair. Kate, who went to the Abbey, while Henry attended in Stinsford, recorded that ‘the good sun shone & the birds sang & everything was done simply, affectionately & well.’ That at the Abbey was a national event. Crowds waited outside in the rain to file past the open grave; Stanley Baldwin and Ramsay MacDonald were among the pall bearers. So too were Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw, as ill-matched in their height as in their politics; according to Shaw’s secretary, Blanche Patch, Kipling shook hands ‘hurriedly, and turned away as if from the Evil One’. Hardy had once proposed the creation of ‘a heathen annexe’, suitable for non-believers like Swinburne, Meredith and himself, but T. E. Lawrence, absent in Karachi, thought he might have been amused at his belated capture by Church and Establishment: ‘Hardy was too great to be suffered as an enemy to their faith: so he must be redeemed.’

Dorchester is famously Hardy’s ‘Casterbridge’, at the centre of Wessex, and many a biographer has remarked that his heart rightly belongs there. Yet when Hardy began writing, he had no reason to suppose that for more than fifty years his imagination would linger in the southwestern counties of England. Rather than a calculated first step, as he later liked to suggest, the name ‘Wessex’ was introduced casually in Far from the Madding Crowd, in a description of Greenhill Fair as ‘the Nijni Novgorod of Wessex’, when most readers must have been struck as much by the reference to Nijni Novgorod as by the disinterment of the ancient name of Wessex. In a miniature way the sentence is revealing about Hardy’s position as a regional writer. In describing the sheep fair, on ‘the busiest, merriest, noisiest day of the whole statute number’, the narrator associates himself not only with its regular visitors but also with those outsiders for whom Greenhill and Nijni Novgorod, since 1817 the site of the annual Makaryev Fair, are equally places to read about rather than to visit. He is at once a participant in local life and custom, and an educated observer of it.

Perhaps it is only just that the town has a slightly uneasy relation with Hardy and his legacy. It is at least a profitable one. Tourists began using his fiction as a guide to the area as early as the 1890s, and Hardy was canny enough to identify his work with the Wessex ‘brand’; his first volume of short stories was titled Wessex Tales, his first collection of verse Wessex Poems. ‘Wessex’ was not only what he knew; it was what he brought to the literary market-place. The brand remains: contemporary visitors can stay at the Wessex Royale hotel, travel by Wessex taxis, or have their used cars broken up by Wessex Metals. But the visitor who asks in the town centre for directions to Max Gate, or to Hardy’s birthplace at Higher Bockhampton, is likely to ask in vain. When in 1999 Prince Edward was created Earl of Wessex (an earldom defunct since the eleventh century), it was the film Shakespeare in Love, not Hardy’s work, which suggested the title.

Divided in life, then, as divided in death? The trope is obviously tempting. Hardy’s fiction is full of characters caught between two ways of life, of natives who return to find that rather than ‘native’ they have become harbingers of a wider and typically newer way of life. But the simple metaphor of division does less than justice to Hardy’s constant negotiation with the class stratification of Victorian society. Part of what Hardy took from his Wessex background, and his family ties, was the strength and will to leave, but the struggle to return imaginatively, and to recreate a past informed by the sense of its own passing, marks all his fiction and most of his verse. It is not division for which Hardy should be remembered, still less in lazy terms of a ‘snob’ trying to disown his roots, or a ‘self-educated peasant’ who could never disguise them, but the search for connection, between social groups, modes of speech, aspiration and memory, the complex sense of participancy and the still more complex right of individuals to be themselves. If the double funerals have an element of the grotesque, easily attached to the marginalising adjective ‘Hardyan’, his achievement as a poet and novelist makes him central to the ‘great tradition’ of English writing.

Phillip Mallett teaches English Literature at the University of St Andrews. He is editor of the Thomas Hardy Journal and Vice-Preseident of both the Thomas Hardy Society and the Thomas Hardy Association. His edition of Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree for Oxford World’s Classics is forthcoming in May 2013.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Thomas Hardy’s Grave by Caroline Tandy [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The two funerals of Thomas Hardy appeared first on OUPblog.

Changing the conversation about the motives of our political opponents

“Our country is divided.” “Congress is broken.” “Our politics are polarized.” Most Americans believe there is less political co-operation and compromise than there used to be. And we know who is to blame for this situation—it’s our political opponents. Democrats know that Republicans are to blame, and Republicans know that Democrats are to blame. Not only do we know that our political opponents are to blame, but we are suspicious of their motives, of why they take the positions they take. Bottom line: we can’t trust them.

This is a serious problem for our country. One source of the problem is a misperception of what really motivates people’s political opinions, judgments, and actions. People often assume such opinions are all about self-interest or all about “carrots and sticks.” As Romney recently put it, “What the president’s campaign did was focus on certain members of his base coalition, give them extraordinary financial gifts from the government, and then work very aggressively to turn them out to vote, and that strategy worked.” Plenty of commentators criticized the reference to minorities, the poor, and students as essentially being paid off for their votes, but few if any disputed the overall assumption that the “carrots” candidates offer voters determine the vote. Indeed, the field of ‘public choice’ in economics assumes just this, that voters are guided by their own self-interest and “vote their pocketbooks.”

What does it mean for our political conversation to assume that the opinions, judgments, and actions of our political opponents are motivated by self-interest? It means that their stands on political issues are selfish rather than being in the best interest of our country. We can’t trust them to be concerned about what is best for the rest of us because our interests are different than their interests. We assume that they do not have good will. But what if people are not primarily motivated by self-interest (by “carrots”) in the political domain or in any other domain of life? In fact, there is substantial evidence from research on human motivation that what people want goes well beyond attaining “carrots” (or “gifts”). What they want is to be effective.

Brian Deese, right, Special Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, and Economic Advisor Gene Sperling confer as President Barack Obama calls regional politicians to inform them of the next day’s announcement about General Motors filing for bankruptcy, Sunday night, May 31, 2009. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Yes, one way of being effective is to have desired outcomes, which can include attaining “carrots” (and avoiding “sticks”). But there is much more to being effective. People also want to be effective at establishing what’s real or right or correct (being effective in finding the truth), as when people want to hear the truth about themselves or what is happening in their lives even if “the truth hurts.” Indeed, people want to observe, discover, and learn about all kinds of things in the world that have nothing to do with their attaining “carrots” (or avoiding “sticks”). And people also want to manage what happens, to have an effect on the world (being effective in having control), as when children jump up and down in a puddle just to make a splash. Indeed, people will take on pain and even risk injury to feel in control of a difficult and challenging activity, as illustrated most vividly in extreme sports.

It is establishing what’s real (truth) and managing what happens (control) that often are our primary motivations — rather than self-interest — and this is both good news and bad news if we are to change the political conversation. The bad news is that humans, uniquely among animals, establish truth by sharing reality with others who agree with their beliefs (or with whom they can establish agreed-upon assumptions). And when they do create a shared reality with others, they experience their beliefs as objective — the whole truth and nothing but the truth. This means that when others disagree with these beliefs, as when Democrats and Republicans disagree with each other, each side is so certain that what they believe is reality, that they infer that those on the other side must either be lying about what they truly believe or they are too stupid to recognize the truth or they are simply crazy. These derogations of our political opponents don’t derive from our self-interests being in conflict with them. It is more serious than that. It derives from the establishment of a different shared reality to them, a shared reality that we are highly motivated to maintain because it gives us the truth about the how the world works.

This is bad news indeed. But if we understand that out political opponents just want to be effective in truth, there is a ‘good news’ silver lining. The good news is that we need not characterize our political opponents as being selfish, or liars, or stupid, or crazy. We need not question their good will. Instead, we can recognize that they, like us, want truth and control, and they want truth and control to work together effectively. They want to “go in the right direction.” They, like us, want our country to be strong. They want Americans to live in peace and prosperity. Yes, they have different ideas about what direction is the right one to make this happen, but this is something we can discuss. In order to establish what’s real, manage what happens, and go in the right direction — which are ways of being effective that we all want — we need to listen to one another and and learn from one another. This is a political conversation worth having. Let us have that respectful, serious conversation in the New Year and search for common ground. Good will to all.

E. Tory Higgins is the author of Beyond Pleasure and Pain: How Motivation Works. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. He has received the Distinguished Scientist Award from the Society of Experimental Social Psychology, the William James Fellow Award for Distinguished Achievements in Psychological Science (from the Association for Psychological Science), and the American Psychological Association Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions. He is also a recipient of Columbia’s Presidential Award for Outstanding Teaching.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Changing the conversation about the motives of our political opponents appeared first on OUPblog.

Memories of undergraduate mathematics

Two contrasting experiences stick in mind from my first year at university.

First, I spent a lot of time in lectures that I did not understand. I don’t mean lectures in which I got the general gist but didn’t quite follow the technical details. I mean lectures in which I understood not one thing from the beginning to the end. I still went to all the lectures and wrote everything down – I was a dutiful sort of student – but this was hardly the ideal learning experience.

Second, at the end of the year, I was awarded first class marks. The best thing about this was that later that evening, a friend came up to me in the bar and said, “Hey Lara, I hear you got a first!” and I was rapidly surrounded by other friends offering enthusiastic congratulations. This was a revelation. I had attended the kind of school at which students who did well were derided rather than congratulated. I was delighted to find myself in a place where success was celebrated.

Looking back, I think that the interesting thing about these two experiences is the relationship between the two. How could I have done so well when I understood so little of so many lectures?

I don’t think that there was a problem with me. I didn’t come out at the very top, but obviously I had the ability and dedication to get to grips with the mathematics. Nor do I think that there was a problem with the lecturers. Like the vast majority of the mathematicians I have met since, my lecturers cared about their courses and put considerable effort into giving a logically coherent presentation. Not all were natural entertainers, but there was nothing fundamentally wrong with their teaching.

I now think that the problems were more subtle, and related to two issues in particular.

First, there was a communication gap: the lecturers and I did not understand mathematics in the same way. Mathematicians understand mathematics as a network of axioms, definitions, examples, algorithms, theorems, proofs, and applications. They present and explain these, hoping that students will appreciate the logic of the ideas and will think about the ways in which they can be combined. I didn’t really know how to learn effectively from lectures on abstract material, and research indicates that I was pretty typical in this respect.

Students arrive at university with a set of expectations about what it means to ‘do mathematics’ – about what kind of information teachers will provide and about what students are supposed to do with it. Some of these expectations work well at school but not at university. Many students need to learn, for instance, to treat definitions as stipulative rather than descriptive, to generate and check their own examples, to interpret logical language in a strict, mathematical way rather than a more flexible, context-influenced way, and to infer logical relationships within and across mathematical proofs. These things are expected, but often they are not explicitly taught.

My second problem was that I didn’t have very good study skills. I wasn’t terrible – I wasn’t lazy, or arrogant, or easily distracted, or unwilling to put in the hours. But I wasn’t very effective in deciding how to spend my study time. In fact, I don’t remember making many conscious decisions about it at all. I would try a question, find it difficult, stare out of the window, become worried, attempt to study some section of my lecture notes instead, fail at that too, and end up discouraged. Again, many students are like this. I have met a few who probably should have postponed university until they were ready to exercise some self-discipline, but most do want to learn.

What they lack is a set of strategies for managing their learning – for deciding how to distribute their time when no-one is checking what they’ve done from one class to the next, and for maintaining momentum when things get difficult. Many could improve their effectiveness by doing simple things like systematically prioritizing study tasks, and developing a routine in which they study particular subjects in particular gaps between lectures. Again, the responsibility for learning these skills lies primarily with the student.

Personally, I never got to a point where I understood every lecture. But I learned how to make sense of abstract material, I developed strategies for studying effectively, and I maintained my first class marks. What I would now say to current students is this: take charge. Find out what lecturers and tutors are expecting, and take opportunities to learn about good study habits. Students who do that should find, like I did, that undergraduate mathematics is challenging, but a pleasure to learn.

Lara Alcock is a Senior Lecturer in the Mathematics Education Centre at Loughborough University. She has taught both mathematics and mathematics education to undergraduates and postgraduates in the UK and the US. She conducts research on the ways in which undergraduates and mathematicians learn and think about mathematics, and she was recently awarded the Selden Prize for Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education. She is the author of How to Study for a Mathematics Degree (2012, UK) and How to Study as a Mathematics Major (2013, US).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Screenshot of Oxford English Dictionary definition of mathematics, n., via OED Online. All rights reserved.

The post Memories of undergraduate mathematics appeared first on OUPblog.

January 15, 2013

Douglas Christie on contemplative ecology

There is a deep and pervasive hunger for a less fragmented and more integrated way of understanding and inhabiting the world. What must change if we are to live in a sustainable relationship with other organisms? What role do our moral and spiritual values play in responding to the ecological crisis? We sat down with Douglas E. Christie, author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind, to discuss a contemplative approach to ecological thought and practice that can help restore our sense of the earth as a sacred place.

What is the blue sapphire of the mind?

It is an image used by Evagrius of Pontus, a fourth century Christian monk, to describe the condition of the mind transformed by contemplative practice: it is pure and endless and serene, capable of seeing and experiencing union with everything and everyone.

What is “contemplative ecology” and what does it have to do with this idea?

Contemplative ecology has two distinct but related meanings. First, it refers to a particular way of thinking about and engaging ecological concerns, rooted in a distinctive form of contemplative spiritual practice. Second, it refers to a particular way of thinking about spiritual practice, one that understands the work of transforming awareness as leading toward and including a deepened understanding of the intricate relationships among and between all living beings. The underlying concern is to find new ways of thinking about the meaning and significance of the relationship between ecological concern and contemplative spiritual practice, that can help to ground sustained care for the environment in a deep feeling for the living world.

What possible meaning do you think such a contemplative approach can have in an age of massive and growing environmental degradation?

Contemplative traditions of spiritual practice, including those grounded in monastic forms of living, have long occupied the margins of mainstream society. The work of such communities is often hidden from view. Because of this, their contributions to work of social and political transformation can seem, on the face of it, negligible. But a careful examination of the historical record suggests that such communities have contributed and continue to contribute significantly to the project of cultural, social and even political renewal — primarily through their unwavering commitment to uncovering the deepest sources of our bonds with one another and with the living world. In our own moment of ecological and political crisis, these traditions of contemplative thought and practice can help to awaken in us a new awareness of the deepest sources of our shared concern for the world.

Is this a matter of particular concern to religious communities?

Yes, and no. Certainly, environmental degradation is a concern that religious communities around the world are waking up to in a new way, and this includes the particular contributions of monastic communities. But the distinctively contemplative dimension of this renewal transcends religion (at least in narrow terms) and touches on a wider and more fundamental human concern: to truly know ourselves as part of the rich web of life. Contemplative ecology addresses anyone who wishes to think more deeply and carefully about what it is to be alive and attentive to the natural world, and to respond with care and affection.

Douglas E. Christie is Professor of Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University, and the author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology and The Word in the Desert: Scripture and the Quest for Holiness in Early Christian Monasticism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dissolving fractured head. Photo by morkeman, iStockphoto.

The post Douglas Christie on contemplative ecology appeared first on OUPblog.

Ancient manuscripts and modern politics

Oddly, perhaps, there are striking similarities between Western Epicureanism and Eastern Buddhism. Even a cursory glance at Lucretius, On The Nature of Things, reveals a characteristically “Buddhist” position on human oneness and human transience. Greek and Roman Stoicism, too, share this animating concept, a revealing vision of both interpersonal connectedness and civilizational impermanence.

But what has this understanding to do with current world affairs, especially patterns of globalization and interdependence? Consider that in their common passage from the ethereal to the corporeal, Epicureanism, Stoicism and Buddhism all acknowledge one great and indissoluble bond of everlasting being, an essential and harmonious conflation of self and world. While each instructs that the death of self is meaningless, even a delusion, all also agree that the commonality of death can overcome corrosive divisions. This recognized commonality can provide humankind with authentically optimal sources of global cooperation. Whether or not we can ever get beyond our fear of death, it is only this commonality that can ultimately lift us above planetary fragmentation and explosive disunity.

For political scientists, economists, and other world affairs specialists, such a “molecular” view can open new opportunities for the expanding study of globalization and international relations. Rather than focus narrowly on more traditional institutions and norms, this neglected perspective can now offer scholars a chance to look more penetratingly behind the news. The outer world of politics and statecraft is often a reflection of our innermost private selves.

Virtually every species (more than ninety-nine percent, to be more exact) that once walked or crawled on this nearly-broken planet has already become extinct. Exeunt omnes? Where shall we go?

Even among the most sophisticated scholars of globalization and world politics, certain essential truths remain well hidden. As a species, whether openly or surreptitiously, we often take a more-or-less conspicuous delight in the suffering of others. Psychologists and writers call it schadenfreude.

What sort of species can tolerate or venerate such a hideous source of pleasure? To what extent, if any, is this venal quality related to our steadily-diminishing prospects for building modern civilizations upon ancient premises of human oneness?

“Our unconscious,” wrote Freud, “does not believe in its own death; it behaves as if it were immortal. “What we ordinarily describe as heroism may in some cases be no more than denial. Still, an expanded acceptance of personal mortality may represent the very last best chance we have to endure together.

Such acceptance can come from personal encounters with death. All things move in the midst of death, but what does it really feel like to almost die? What can we learn from experiencing near death (no one can “experience” death itself, an elementary insight shared famously by Lucretius, Schopenhauer, and Santayana), and then emerging, whole, to live again?

Can we learn something here that might benefit the wider human community, something that could even move us beyond schadenfreude to viable forms of cooperation and globalization?

Death happens to us all, but our awareness of this expectation is blunted by deception. To accept forthrightly that we are all flesh and blood creatures of biology is more than most humans can bear. Normally, there is even a peculiar embarrassment felt by the living in the presence of the dead and dying. It is almost as if death and dying were reserved only for others.

That we, as individuals, typically cling to sacred promises of redemption and immortality is not, by itself, a species-survival issue. It becomes an existential problem, one that we customarily call war, terrorism, or genocide, only when these assorted promises are forcibly limited to certain segments of humanity, but are then denied to other “less-worthy” segments.

In the end, we must learn to understand, all national and international politics are genuinely epiphenomenal, a symptomatic reflection of underlying and compelling private needs. The most pressing of these private needs is undoubtedly an avoidance of personal death.

It is generally not for us to choose when to die. Rather, our words, our faces, and our countenance, will sometime lie well beyond any considerations of conscious choice. But we can still choose to recognize our shared common fate, and therefore our critical interdependence. This incomparably powerful recognition could carry with it an equally significant collective promise.

Much as we might like to please ourselves with various qualitative presumptions of hierarchy and differentiation, we humans are pretty much the same. This is already abundantly clear to scientists and physicians. Whatever our divergent views on what happens to us after death, the basic mortality that we share can represent the very last best chance we have to coexist and survive. This is the case only if we can first make the very difficult leap from a shared common fate, to more generalized feelings of empathy.

We can care for one another as humans, but only after we have first acknowledged that the judgment of a common fate will not be waived by any harms that are inflicted deliberately upon others, upon the “unworthy.” In essence, modern war, terror, and genocide are often disguised expressions of religious sacrifice. They may represent utterly desperate human hopes of overcoming private mortality through the killing of “outsiders.” Such sacrificial hopes are fundamentally and irremediably incompatible with the more cooperative forms of world politics.

A dual awareness of our common human destination and of the associated futility of sacrifice, offer medicine against endless torment in the global “state of nature.” Only such awareness can genuinely relieve an otherwise incessant war of all against all. Only a person who can feel deeply within himself or herself the unalterable fate and suffering of a broader humanity will ever be able to embrace genuine compassion, and thus to reject destructive spasms of collective violence.

There can be no private conquests of death through war, terror, or genocide. To cooperate and survive as a species, a uniquely courageous and worldwide embrace of mortality, empathy, and caring will first be needed. For students of globalization and world politics, this imperative can represent a timeless understanding of almost unimaginable potency. It’s time to think more about such primal unity, and its still-latent promise for humane globalization and interdependence.

Louis René Beres, Professor of Political Science and International Law at Purdue, was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971). He is currently examining previously unexplored connections between human death fears and world politics. Born in Zürich, Switzerland, at the end of World War II, Professor Beres is the author of ten books, and several hundred articles, on international relations and international law. He is a regular contributor to the OUPblog.

If you’re interested in this subject, you may be interested in Globalization for Development: Meeting New Challenges by Ian Goldin and Kenneth Reinert. Globalization and its relation to poverty reduction and development are not well understood. Goldin and Reinert explore the ways in which globalization can overcome poverty or make it worse, define the big historical trends, identify the main globalization processes (trade, finance, aid, migration, and ideas), and examine how each can contribute to economic development.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ancient manuscripts and modern politics appeared first on OUPblog.

The music industry, change, and copyright

“It was brand new, it was relatively unregulated, and it posed a mortal threat to the music business as it existed at that time, because it was making the product available for free to the public.” That sounds like a discussion of digital music, but it’s a comment on the introduction of radio in the early 20th century.

In this video, Gary A. Rosen, an intellectual property lawyer, explains that the radio industry made the same arguments as digital music providers in their similar battles with the music industry, nearly 100 years apart. The long and tortured career of Ira B. Arnstein, “the unrivaled king of copyright infringement plaintiffs,” opens a curious window into the evolution of copyright law in the United States and the balance of power in Tin Pan Alley. Although Arnstein never won a case, author Gary A. Rosen shows that the decisions rendered ultimately defined some of the basic parameters of copyright law. Arnstein’s most consequential case, against a dumbfounded Cole Porter, established precedents that have provided the foundation for successful suits against George Harrison, Michael Bolton, and many others.

The music industry, radio in the 1920s, and the Internet today

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ira Arnstein and the origin of “Unfair to Genius”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Gary A. Rosen is the author of Unfair to Genius: The Strange and Litigious Career of Ira B. Arnstein. He has practiced intellectual property law for more than 25 years. Before entering private practice, he served as a law clerk to federal appellate judge and award-winning legal historian A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The music industry, change, and copyright appeared first on OUPblog.

January 14, 2013

A letter from Learned Hand

Learned Hand (1872-1961) served on the United States District Court and is commonly thought to be the most influential justice never to serve on the Supreme Court. He corresponded with people in different walks of life, some who were among his friends and acquaintances, others who were strangers to him. In the letter below, Hand writes to Mary McKeon, a New Yorker troubled by Hand’s decision to invalidate the warrantless search and consequent arrest of the Soviet spy, Judith Coplon.

To Mary McKeon

December 28, 1950

Dear Miss McKeon:

I have your letter about the Coplon case and I can understand why you are troubled about the result; and because you were not abusive, I am going to try to explain it to you.

It is a rule — well settled by the decisions of the Supreme Court — that evidence which the Government secures by its own violation of law it may not use against the person whose rights have been invaded. An extreme example of this would be in case a United States marshal were to break into the house of an accused person and seize his papers; the Government would not be allowed to use the papers against the person whose house had been entered. The same thing is true of documents found upon the person of one who is unlawfully arrested as was Judith Coplon. That was one ground for the reversal. The other was that during the trial it became necessary for the Government to depend upon evidence which it was unwilling to let her see. The Constitution provides that a person accused of crime is entitled to have all witnesses, who are called against him, brought into court at the trial.

Thus in these two instances the rights of the accused were violated, which is entirely consistent with her guilt. Perhaps, if you reflect, you will agree that it is not desirable to convict people, even though guilty, if to do so it is necessary to violate those rules on which the liberty of all of us depends.

Truly yours,

Learned Hand

The letter above was excerpted from Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand, edited by Constance Jordan, a retired professor of comparative literature and also Hand’s granddaughter. In 1944, Coplon, who worked for the Foreign Agents Registration section, was recruited as a spy by the NKGB, i.e., the People’s Commissariat for State Security. In 1949, FBI agents detained Coplon as she met with Valentin Gubitchev, a KGB official employed by the United Nations, while carrying what she thought were secret U.S. government documents; in actuality, they were fakes, planted in her purse at the order of J. Edgar Hoover. Declared guilty of espionage by the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in 1949, Coplon appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. In United States v. Coplon, in an opinion authored by Hand and announced on December 5th, her conviction was overturned.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Judge Learned Hand circa 1910. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A letter from Learned Hand appeared first on OUPblog.

HFR and The Hobbit: There and Back Again

Is it the sense of experiencing reality that makes movies so compelling? Technological advances in film, such as sound, color, widescreen, 3-D, and now high frame rate (HFR), have offered ever increasing semblances of realism on the screen. In The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, we are introduced to the world of 48 frames per second (fps), which presents much sharper moving images than what we’ve seen in movies produced at the standard 24 fps. Yet many viewers, including myself, have come away with a less-than-satisfying experience as the sharp rendering of the characters portrayed is reminiscent of either old videotaped TV programs (soap operas, BBC productions) or recent CGI video games. What features of HFR create this new sensory experience and why does it appear so unsettlingly similar to the experience of watching a low budget TV program?

One factor that can be ruled out is the potential difference in flicker rate. Moving images are of course created by the rapid succession of still frames, and thus the flicker or on-and-off rate must be fast enough so that we do not perceive any change in illumination between frames. With early silent films, the flicker rate was less than 16 fps, and a noticeable flashing or flickering was apparent (hence the term “flicks” to refer to these early movies). Since the advent of sound, the standard has been 24 fps, though the flicker rate is increased with the use of a propeller-like shutter that spins rapidly in a movie projector so that a movie running at 24 fps actually presents each frame two or three times, thereby increasing the flicker rate to 48 or 72 fps. Thus, with respect to flicker rate we have always watched movies at HFR.

A still from The Hobbit film. (c) Warner Bros.

Two factors have motivated the current interest in HFR. The obvious one is that actions recorded at more rapid frame rates, such as a car chase shot at 48 fps vs 24 fps, would reduce by half the distance objects move across successive frames. With HFR we are presented shorter increments of movement, and our brains need not work as hard to extrapolate apparent motion across frames, which may result in a smoother sense of motion. I, however, do not think that it is this between-frame difference that is driving our sensory experience as we watch The Hobbit. A second, less known factor, is that the movie was shot at a faster shutter speed than movies shot at 24 fps. Filmmakers have a rule that states that the shutter speed at which each frame is shot should be half as long as the frame duration. Thus, most movies we’ve seen have been shot at 24 fps with a shutter speed of 1/48 sec for each frame. Those of you who have played with photography know that this shutter speed would produce rather blurry images when the camera is hand held. On a tripod, a movie filmed with this shutter speed would show fast moving objects (e.g., cars) with a noticeable blur. When movies filmed at 24 fps are shot with a faster shutter speed and less motion blur, actions appear jerky and unnatural.

The Hobbit was filmed with a shutter speed of 1/64 sec, which produced less motion blur and thus sharper images compared to movies shot at 24 fps. At the faster frame rate, the jerkiness associated with presenting sharp images at 24 fps is largely reduced, though I did notice that on some occasions large camera movements and fast movements of actors appeared stilted and unnatural. A psychological study by Kuroki and colleagues showed that in order to perceive naturalistic movements with sharp moving images (i.e., no motion blur) it is necessary to use frame rates of 250 fps or faster. Interestingly, the shutter speed used for The Hobbit closely matches that used for old videotaped TV programs, which were filmed at 30 fps with a shutter speed of 1/60 sec. I suspect that it is this close match in shutter speed (and thus similarity in image sharpness) that creates the impression of viewing a soap opera when we watch Bilbo Baggins and company.

In the future, after years of experiencing HFR movies, will we be able to appreciate the more realistic renderings garnered by this new technology? Will a younger generation without prior associations to videotaped TV programs be enamored by the sharper images? Time will tell, though I’m skeptical. HFR does offer a more realistic rendering than what we’ve previously encountered at the movies, and further advances may help to refine its use. Yet do we really want to have an entirely realistic portrayal? In most cases that would mean having the experience of sitting next to the director watching actors on a sound stage with artificial lighting, which is exactly the impression I had while watching Bilbo backlit by what was supposed to be moonlight. Instead, we may end up preferring a softer image which maintains the illusion of being engaged in an adventure with our favorite fictional characters and partaking in a wonderfully unexpected journey.

Arthur P. Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He studies the psychological and biological underpinnings of memory and movies. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. He is co-editor of Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience (Shimamura & Palmer, ed., OUP, 2012), editor of the forthcoming Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies (ed., OUP, March 2013), and author of the forthcoming book, Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (May 2013). Further musings can be found on his blog, http://psychocinematics.blogspot.com.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post HFR and The Hobbit: There and Back Again appeared first on OUPblog.

The Tottenham riots, the Big Society, and the recurring neglect of community participation

The Tottenham riots in the London Borough of Haringey took place in August 2011. We examined three responses to them: reports by North London Citizens, an alliance of 40 mostly faith community institutions including schools, the Tottenham Community Panel established by Haringey Council, and the Riots, Communities and Victims Panel established by Parliament.

The riots coincided with the end of an era of British urban policy when various community-centred regeneration programmes introduced by the previous New Labour Government, were being wound down. One of its flagship initiatives was the New Deal for Communities (NDC), a ten year programme which invested £50 million in each of thirty deprived areas including Tottenham. More recently, David Cameron has promoted the idea of the Big Society with an accompanying rhetoric that blames big government for enfeebling the civic sphere.

Two of the three analyses of the Tottenham riots that we examined shared this perspective. North London Citizens emphasised the need to create new community leaders; the Riots Communities and Victims Panel emphasised an on-going failure of services to engage with communities and vaguely endorses an agenda of neighbourhood-level community empowerment. Cameron’s Big Society agenda envisioned communities and neighbourhoods becoming empowered to take local decisions and solve local problems taking over the running of services and facilities where appropriate. None of the three reports make such recommendations for Tottenham. Rather, they restate in minor key the need for greater responsiveness to communities with no clear ideas about how this might be achieved.

Two of the three analyses of the Tottenham riots that we examined shared this perspective. North London Citizens emphasised the need to create new community leaders; the Riots Communities and Victims Panel emphasised an on-going failure of services to engage with communities and vaguely endorses an agenda of neighbourhood-level community empowerment. Cameron’s Big Society agenda envisioned communities and neighbourhoods becoming empowered to take local decisions and solve local problems taking over the running of services and facilities where appropriate. None of the three reports make such recommendations for Tottenham. Rather, they restate in minor key the need for greater responsiveness to communities with no clear ideas about how this might be achieved.

All three reports emphasised a deficit in community cohesion. All three identified inadequate engagement by local service providers with residents as part of the problem. But Tottenham has been here before. The aftermath of the 1985 riot saw considerable effort to improve, foster and build community cohesion in Tottenham. Many of the buildings that were looted and burned in 2011 had been the focus of regeneration efforts.

We had just completed research on the efficacy of such policies when the riots occurred. Our 2011 book Lessons for the Big Society: planning, regeneration and the politics of community participation (Ashgate, 2011) examined a long history of failed efforts by the local authority to secure such participation. There were many reasons for this. Labour held a political monopoly in Tottenham. Community activism not sponsored by the party was often ignored. The institutional culture of the local authority councillors and officials was often hostile to community participation in decision-making even if official rhetoric claimed otherwise. Well-to-do parts of the borough had articulate well-organised groups capable of putting pressure on officials and councillors. Community groups in Tottenham lacked the skills and cultural capital that worked to win responsiveness from institutional actors.

The kind of community capacity that regeneration programmes in Tottenham sought to introduce appeared feeble compared to the on-going capacity for unsolicited activism found in well-to-do areas – expressed through single issue campaigns, the establishment of long-standing amenity groups and well-organised networks able to compel responsiveness from Council officials and councillors. The New Labour diagnosis was that areas like Tottenham lacked the necessary social capital. But the regeneration programmes it put in place engendered only a limited form of community capacity, and this depended on the life-support of funding that has since ended.

What then for Cameron’s Big Society? Even after decades of community-focused urban renewal in Tottenham, both community-institutional relationships and community cohesion remain weak. However, this does not justify the withdrawal of state support or bucolic expectations that civil society can fill the resulting void with minimal support. The very localities that need community empowerment also need state support the most.

We argue that what might work for Tottenham is an approach that seriously interrogates why past regeneration efforts were unable to empower local communities but at the same time accepts that such empowerment cannot be realised without significant state funding. It would take seriously the scepticism-bordering-on-hostility of the Big Society to local authority officialdom. But what Tottenham needs for the foreseeable future is big government willing to learn from past mistakes.

Professor Bryan Fanning is the Head of the School of Applied Social Science at University College Dublin. Dr Denis Dillon is employed by Community Services Volunteers (CSV) in North London. They are the co-authors of Lessons for the Big Society: planning, regeneration and the politics of community participation (Ashgate, 2011). Their article, The Tottenham riots: the Big Society and the recurring neglect of community participation, appears in Community Development Journal.

Since 1966 the leading international journal in its field, Community Development Journal covers a wide range of topics, reviewing significant developments and providing a forum for cutting-edge debates about theory and practice. It adopts a broad definition of community development to include policy, planning and action as they impact on the life of communities. It publishes critically focused articles which challenge received wisdom, report and discuss innovative practices, and relate issues of community development to questions of social justice, diversity and environmental sustainability.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: After the Riot – View from near Scotland Green. Photo by Alan Stanton, 2011. Creative Commons Licence. (via Wikimedia Commons)

The post The Tottenham riots, the Big Society, and the recurring neglect of community participation appeared first on OUPblog.

January 13, 2013

The death of Edmund Spenser

Writing to his friend Dudley Carleton on 17 January 1599, the enthusiastic correspondent John Chamberlain (1553-1628) noted that “Spencer, our principall poet, coming lately out of Ireland, died at Westminster on Satturday last.” Chamberlain’s testimony confirms that Spenser died on 13 January. Chamberlain is a good recorder of court gossip and a barometer of what interested the upper echelons of London society. Edmund Spenser’s death is reported at the end of a letter listing the marriages and deaths of people the two correspondents both knew. We have no idea what led to Spenser’s death. The few accounts we have of his last days, all of which are brief and limited in detail, fail to provide clues of his state of health or mind. The trouble is that different explanations are equally plausible. Spenser’s circumstances might have had an impact on the timing of his death, or he might simply have died of natural causes, being neither especially young nor particularly old to die in an era of relatively primitive medical practice, bad diet, and the absence of comfort when winter weather was extreme. The most striking fact is that he died within three weeks of leaving Ireland, having left in grim circumstances.

By the time of his death Spenser was undoubtedly the most celebrated and important poet writing in English. He had assumed the mantle of Sir Philip Sidney, the most important aristocratic poet before Spenser; William Shakespeare wasn’t really in Spenser’s league as a poet; John Donne and Ben Jonson were yet to emerge as poets of stature. Yet, according to Jonson, talking to William Drummond some years later Spenser “died for lack of bread.” It is unlikely that this is true as Spenser had a generous pension from the queen of £50 per annum, and had carried some letters from the desperate colonists in Ireland to the Privy Council who, surely, had not stood by and let him starve. Perhaps payments were delayed; more likely Jonson’s comments are a reflection on the catastrophic loss that Spenser had suffered when his estate was over-run in Ireland and he was forced to flee. Legend has it that Spenser and his family escaped via a cave beneath his house at Kilcolman, but it is more likely that they had already fled to the safety of Cork city before heading for London. Spenser, it seems, was recognised as an unfortunate writer, one whose talent had taken him from relatively obscure origins to unprecedented heights, only to cheat him at the last.

Cave at Kilcolman. Courtesy of Andrew Hadfield.

But if Spenser was a detested colonist in Ireland and overlooked by the authorities in England, he was celebrated and lauded by his fellow poets in London. He was buried at the end of January in Westminster Abbey. William Camden has provided the best account of what must have been a moving and significant event. Camden, like Jonson, provides evidence in his short sketch of Spenser’s life and death that Spenser was perceived to have been harshly treated in life and that he died in poverty, a belief shared by most who commented on the last months of Spenser’s life in the early seventeenth century. Camden writes:

But by a Fate which still follows Poets, he always wrastled with poverty, though he had been Secretary to the Lord Grey, Lord Deputy of Ireland. For scarce had he there settled himself in a retired Privacy, and got Leisure to write, when he was by the Rebels thrown out of his Dwelling, plundered of his Goods, and returned into England a poor man, where he shortly after died, and was interred at Westminster, near to Chaucer, at the Charge of the earl of Essex; his hearse being attended by Poets, and mournfull Elegies and Poems with the Pens that wrote them thrown into his Tomb.

The area where Spenser was thought to be buried was dug up in the inter-war period but there was no trace of the body, poems or pens.

Many of these elegies would have reappeared in print, such as that by the young Cornish poet, Charles Fitzgeoffrey (1593-1636), who had already praised Spenser as the heir of Homer in his long lament for Sir Francis Drake (1596), and who now cast him as the English Virgil in a series of Latin tributes published in 1601. There were poems from more established writers such as Nicholas Breton, whose “An Epitaph Upon Poet Spencer,” with such memorable lines as, “Sing a dirge on Spencers death, / Till your soules be out of breath,” was published as the last poem in the volume, Melancholike Humours (1600). It is also likely that another elegy written for the occasion was the unpublished Latin epigram by William Alabaster (1567-1640), ‘In Edouardum Spencerum, Britannicae poesios facile principem,’ which does sound as if it were designed for the funeral:

Fors qui sepulchre conditur siquis fuit If who’s buried here,

Quaeris uiator, dignus es qui rescias. you ask passerby, you deserve to hear.

Spencerus istic conditur, siquis fuit Spenser is buried here. If who he is

Rogare pergis, dignus es qui nescias. you go on to ask, you don’t deserve to know.

The decision to bury Spenser near to Chaucer was a first step towards defining the collection of graves of writers in the south transept, Poets’ Corner. The area was not formally designated as the resting place for the nation’s most celebrated writers until the eighteenth century, but Spenser, generally accepted as the natural heir of Chaucer, was buried next to his most illustrious predecessor, a decision that started a trend. By 1723 the site contained the graves and monuments of a number of illustrious poets: Samuel Butler, Abraham Cowley, Michael Drayton, John Dryden, Thomas Shadwell and others. A monument was eventually erected by Lady Anne Clifford. Clifford, who had been taught by Samuel Daniel and was later pictured alongside her books, which included Spenser, was clearly eager to advertise her role as a reader and patron of English poetry. The monument was built by Nicholas Stone (1585/8-1647), who noted in his account book, “I also mad a moument for Mr. Spencer, the pouett and set it up at Westmester for which the contes of Dorsett payed me 40£.” Stone was a distinguished master mason, “the best English sculptor of his generation,” who later designed John Donne’s tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral, helped build the Banqueting House in Whitehall from Inigo Jones’s designs, as well as Goldsmith’s Hall and a number of other funeral monuments and prominent country houses. The inscription on the now destroyed monument, gave erroneous dates for the poet’s birth and death, although, at least, his Christian name was spelled correctly:

HEARE LYES (EXPECTING THE SECOND

COMMINGE OF OVR SAVIOUR CHRIST

JESVS) THE BODY OF EDMOND SPENCER,

THE PRINCE OF POETS IN HIS TYME;

WHOSE DIVINE SPIRIT NEEDS NOE

OTHIR WITNESSE THEN THE WORKS

WHICH HE LEFT BEHINDE HIM.

HE BORNE IN LONDON IN

THE YEARE 1510. AND

DIED IN THE YEARE

1596.

Spenser monument, Westminster Abbey. Reproduced with kind permission of Westminster Abbey.

According to the antiquarian John Dart (d.1730), it was not an impressive edifice, a pointed contrast to its replacement. Recommending a tour of the poets’ monuments in the South Transept, Dart notes that:

[T]he first Tomb you come at is a rough one, of coarse Marble and looks by the Moisture and Injury of the Weather, and the Nature of the Stone, much older than it is. This, whose Form is here erected to the Memory of Mr. Edmond Spencer, a Man of great Learning and such luxuriant Fancy, that his Works abound with as great Variety of Images (and curious tho’ small Paintings) as either our own or any Language can afford in any Author.

Dart, citing Camden as an authority, reproduces a Latin epitaph that was supposedly on the original tomb, although it is now no longer visible. Dart translates it as:

Here lies Spenser next to Chaucer, next to

him in talent as next to him in death. O Spenser,

here next to Chaucer the poet, as a poet you are

buried; and in your poetry you are more permanent

than in your grave. While you were alive, English

poetry lived and approved you; now you are dead,

it too must die and fears to.

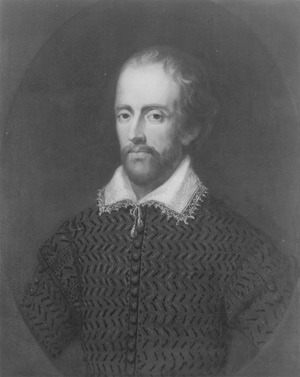

Chesterfield portrait of Edmund Spenser. Reproduced with kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

None of this remains and Dart and Camden are the only witnesses to the original. The monument was important enough to feature in John Hughes’ edition of his works, in an engraving by Loius de Guernier. The edition, the first illustrated edition of Spenser’s works, included a picture of four well-dressed figures, two men and two women, discussing the inscription on Spenser’s tomb, obviously in the absence of a portrait of the poet . Poets’ Corner was taking shape as a place in the public imagination, started through the union of Chaucer and Spenser. The monument decayed and crumbled away and was replaced in 1778 by a more durable marble structure in the same style, built by William Mason (1725-97), the poet and garden designer, who had been a fellow at Pembroke College. Mason also gave the college a copy of the Chesterfield portrait which hangs in the hall. Now, there was a clear desire to know what Spenser had looked like, unfortunately a long time after any evidence could be recovered.Andrew Hadfield is Professor of English at the University of Sussex and the author of Edmund Spenser: A Life (OUP, 2012). He is the author of a number of works on early modern literature, including Shakespeare and Republicanism; Literature, Travel and Colonialism in the English Renaissance, 1540-1625; Spenser’s Irish Experience: Wilde Fruyt and Salvage Soyl; and Literature, Politics and National Identity: Reformation to Renaissance. He was editor of Renaissance Studies (2006-11) and is a regular reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement. Read his previous blog post “10 facts and conjectures about Edmund Spenser” and “Edmund Spenser: ‘Elizabeth’s arse-kissing poet?’”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The death of Edmund Spenser appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers