Oxford University Press's Blog, page 987

January 12, 2013

Choice in the true necessaries and means of life

In 1845 Henry David Thoreau left his home town of Concord, Massachusetts to begin a new life alone, in a rough hut he built himself a mile and a half away on the north-west shore of Walden Pond. Walden is Thoreau’s classic autobiographical account of this experiment in solitary living, his refusal to play by the rules of hard work and the accumulation of wealth and above all the freedom it gave him to adapt his living to the natural world around him.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun rose clear. It is never too late to give up our prejudices. No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. What every body echoes or in silence passes by as true to-day may turn out to be falsehood to-morrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields. What old people say you cannot do you try and find that you can. Old deeds for old people, and new deeds for new. Old people did not know enough once, perchance, to fetch fresh fuel to keep the fire a-going; new people put a little dry wood under a pot, and are whirled round the globe with the speed of birds, in a way to kill old people, as the phrase is. Age is no better, hardly so well, qualified for an instructor as youth, for it has not profited so much as it has lost. One may almost doubt if the wisest man has learned any thing of absolute value by living. Practically, the old have no very important advice to give the young, their own experience has been so partial, and their lives have been such miserable failures, for private reasons, as they must believe; and it may be that they have some faith left which belies that experience, and they are only less young than they were. I have lived some thirty years on this planet, and I have yet to hear the first syllable of valuable or even earnest advice from my seniors. They have told me nothing, and probably cannot tell me any thing, to the purpose. Here is life, an experiment to a great extent untried by me; but it does not avail me that they have tried it. If I have any experience which I think valuable, I am sure to reflect that this my Mentors said nothing about.

Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Stephen Fender, Professor of American Studies and Director of the Postgraduate Centre in the Humanities, University of Sussex, this new edition of Walden considers the author in the context of his birthplace and his sense of its history: social, economic and natural. In addition, an ecological appendix provides modern identifications of the myriad plants and animals to which Thoreau gave increasingly close attention as he became acclimatized to his life in the woods by Walden Pond.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Choice in the true necessaries and means of life appeared first on OUPblog.

January 11, 2013

The map she carried

In the heyday of the British Empire, Britain’s second most-widely-read book, after the Bible, was: (a) Richard III (b) Robinson Crusoe (c) The Elements (d) Beowulf ? Why do I ask?

“Since late medieval or early modern time,” Michael Walzer writes in Exodus and Revolution, “there has existed in the West a characteristic way of thinking about political change, a pattern that we commonly impose upon events, a story that we repeat to one another. The story has roughly this form: oppression, liberation, social contract, political struggle, new society…. Because of the centrality of the Bible in Western thought and the endless repetition of the story, the pattern has been etched deeply into our political culture. It isn’t only the case that events fall, almost naturally, into an Exodus shape; we work actively to give them that shape.”

The second-most-widely-read book plays that role in Western thought too: (c) The Elements by Euclid. Since late medieval or early modern time, there has existed in the West a characteristic way of organizing knowledge, a pattern that we commonly impose upon observations, concepts, and ideas, a pattern we teach our children. Because of the centrality of Euclid in Western education and the endless repetition of his axioms, definitions, theorems and proofs, the pattern has been etched deeply into our intellectual culture. It isn’t only the case that knowledge falls, almost naturally, into a Euclidean shape; we work actively to give it that shape.

Euclid was the geometry of the medieval university and the bedrock of European education for centuries. It wasn’t just about the triangles; Euclid sharpened your mind, trained your logic. His clever proofs were the very model of argument. To master Euclid was to master the world, the world around you and beyond. “Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night; God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.” And what did Newton’s lamp look like? See for yourself in the Principia Mathematica. “All human knowledge begins with intuitions,” said Kant, “proceeds from there to concepts, and ends with ideas.” Where do you think he got that? Euclideana even permeates our politics, but for this blog I’ll stick to science.

Non-Euclidean geometries put an end to that? No, they didn’t. Non-Euclidean geometries substituted one axiom for another, but they kept Euclid’s vision of organized knowledge, his faith in deductive reasoning. Non-Euclidean geometry is as Euclidean as Euclid’s! So is the new, improved axiom set David Hilbert proposed for geometry in the 19th century. (It turned out that Euclid’s wasn’t perfect.) So is the quixotic Russell-Whitehead program, in the early 20th century, to reduce mathematics to logic. Modern mathematics is consciously Euclidean to the core. In 1900, in a still-influential address, David Hilbert proposed rewriting Newton for modern physics along this vision of organized knowledge.

Born in 1894, Dorothy Wrinch grew up in a London suburb. She aced the mathematics program at Cambridge University and then studied logic with Bertrand Russell. The naturalist D’Arcy Thompson was another mentor and friend; his Growth and Form was her bible. Tugged by philosophy, mathematics, and biology for a decade, she cast her lot with biology, determined to unravel it through the powerful lens of logic. The model of protein architecture she came up with catalyzed protein chemists despite or because of its weaknesses. Why?

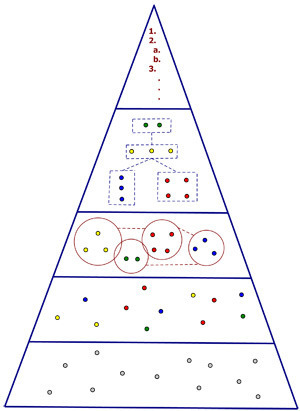

Figure 1. Dorothy Wrinch’s model of scientific development: First stage: brute facts. Second: sorting facts into classes. Third: theories linking the classes and explaining the facts. Fourth, finding the relationships among the theories and deducing their logical consequences. Fifth, Euclid-style axioms.

In her philosophy phase, Dorothy argued that not only physics but every science will look like geometry when it grows up. All sciences pass through the same five stages (right), she said, though they vary in their rate of ascent. Physics is mature, she said, and sociology embryonic. But biology, her special mission, was just ripe for logic.With this map to guide her, she found what she was looking for. “A number of new sciences have passed from the embryonic stage,” she wrote in 1934. “Discarding description as their ultimate purpose, they are now ready to take their places in the world state of science. The thesis which I wish now to develop is but a logical consequence of the thorough-going application of this principle.” Her protein model was one such consequence.

Biology ripe for logic? Some natives were not amused. (Or they were.) “Her idea of science is completely different from theirs,” Linus Pauling put it. You betcha!

Euclid fell from his curricular throne and the British Empire collapsed at about the same time. Quantum mechanics scotched Hilbert’s program and Gödel scotched Russell’s. Biology has resisted Euclid too. Though the structures of thousands of proteins are now known in exact detail, their inner logic remains where Dorothy left it, the brass ring on the Nobel carousel.

Marjorie Senechal is the Louise Wolff Kahn Professor Emerita in Mathematics and History of Science and Technology, Smith College, author of I Died for Beauty: Dorothy Wrinch and the Cultures of Science, and Editor-in-Chief of The Mathematical Intelligencer. At the Join Mathematics Meeting, AMS-MAA Special Session on the History of Mathematics, II, Room 9, Upper Level, San Diego Convention Center, she is speaking on 5:00 p.m. on Saturday, 12 January, on Biogeometry, 1941.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about mathematics on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The map she carried appeared first on OUPblog.

Do old people matter?

A couple of weeks ago one of us (MG) attended the biannual Hospice New Zealand conference in Auckland where there was a discussion session responding to the question ‘Do old people matter?’ The general feeling amongst delegates was that, of course they matter, or for some, of course we matter. The answer to the question was regarded to be self-evident; no debate was needed. However, it leaves us with the question as to whether this was actually an accurate representation of delegates’ underlying beliefs, or indeed of those held by society as a whole. On reflection, maybe not. Whilst we may all fervently believe that we aren’t ageist and castigate explicit examples of ageism, negative connotations of ageing are so deep rooted in our society that they are difficult to escape. We would argue that even those of us working in a field such as palliative and end of life care aren’t immune to such charges.

For example, older people are less likely than younger people to have access to specialist palliative care and more likely to die in settings where concerns have been raised about the quality of end of life care provided, notably hospitals and care homes. This is despite the fact that age shouldn’t dictate levels of palliative care need experienced. Rather, the current patterns of care reflect deep-rooted ageism, both in terms of individual clinician patterns of referral to specialist palliative care, and in relation to more subtle practices within society. Indeed, whilst we may all struggle against the charge of ageism, ultimately we tolerate the ‘warehousing’ of older people in institutions where good care is so poorly valued that staff (predominantly unregulated and unregistered), typically receive little more than the minimum wage to look after some of the most vulnerable people in our societies at the end of their lives.

For example, older people are less likely than younger people to have access to specialist palliative care and more likely to die in settings where concerns have been raised about the quality of end of life care provided, notably hospitals and care homes. This is despite the fact that age shouldn’t dictate levels of palliative care need experienced. Rather, the current patterns of care reflect deep-rooted ageism, both in terms of individual clinician patterns of referral to specialist palliative care, and in relation to more subtle practices within society. Indeed, whilst we may all struggle against the charge of ageism, ultimately we tolerate the ‘warehousing’ of older people in institutions where good care is so poorly valued that staff (predominantly unregulated and unregistered), typically receive little more than the minimum wage to look after some of the most vulnerable people in our societies at the end of their lives.

We were left wondering whether things have got better or worse in terms of end of life care for older people over time. Was there ever really a ‘golden age’ where communities revered their older members and cared for them collectively up until death? Allan Kellehear argues that this overly romanticised historical picture bears little relation to the realities of abandonment and mercy killing of older people practised by our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Like us, they saw frail older people as a problem for society, although he argues that unlike us, they viewed dying as an inevitable part of living. He concludes that recognising the inevitability of dying and discussing it within our families and communities, as well as at a service and policy level, is fundamental to ensuring a humane response to the growing demand for end of life care for our ageing populations.

And what is apparent is that the need is growing. Internationally the number of people dying annually will almost double over the next 30 years. Fifty six million people died in 2009; 91 million are likely to die in 2050. For developed countries, the ageing and dying of the ‘baby boomers’ will possibly be the greatest public heath challenges of this century. Many people say that they would want to die without warning, ‘in their sleep.’ The reality is that most people will have protracted deaths, linked to a combination of long term conditions and having to cope with co-morbities, including cognitive frailty. The UK report ‘Dying for Change’ (2010) argues that society is ill-prepared for how caring for the dying will change in the next two decades as people live longer. The co-author of this report, Charles Leadbetter, warns us that: “confronting, managing and experiencing death are among the most difficult, painful and troubling issues we face.” As Paul Cann notes we need to put end of life care in the middle of our lives: this is everybody’s business.

Merryn Gott and Christine Ingleton are the editors of Living with Ageing and Dying: Palliative and End of Life Care for Older People. Merryn Gott joined the University of Auckland in 2009 as Professor of Health Sciences in the School of Nursing. Her PhD is in gerontology and over the last 12 years she has developed an international programme of research exploring palliative and end of life care for older people. Christine Ingleton is Professor of Palliative Care Nursing in the School of Nursing & Midwifery at the University of Sheffield. She has contributed to 30 research grants and awards totalling over L3.5 million. She has published over 90 outputs in peer reviewed journals and contributed to 6 books on health services research.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: old couple sitting on bench in park, autumn. Photo by sculpies, iStockphoto.

The post Do old people matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

The Beatles and “Please Please Me,” 11 January 1963

Although “Love Me Do” had been the Beatles’ induction into Britain’s recording industry, “Please Please Me” would bring them prominently into the nation’s consciousness. The songwriters, the band, the producer, and the manager all thought that they had finally found a winning formula. An advertisement in the New Musical Express proclaimed that the disc would be the “record of the year,” even as it raised a chuckle among industry insiders; but the hyperbole would prove prophetic.

Britons struggled as January introduced them to 1963. The biting cold and snow only reinforced a national funk incubated by French rejection of the UK’s application to the European Common Market, by the recurring strikes of power workers, and by the sudden decline of Labour Party leader Hugh Gaitskell’s health. Families gathered around television sets waiting for news on Gaitskell’s condition, even as some had their electricity interrupted, leaving dark screens and colder rooms. With the recent Cuban missile crisis still in the nation’s minds and the international Cold War in its most frigid phase, viewers pined for some warmth.

When Parlophone released “Please Please Me” on Friday 11 January, Keith Fordyce in the New Musical Express expressed skepticism, with most of the year ahead of them, that “Please Please Me” could possibly be the “record of the year”; however, he made a powerful observation. He noted that the disc was “full of beat, vigour, and vitality — and what’s more, it’s different. I can’t think of any other group currently recording in this style.” Musically, the Beatles stood out. Cliff Richard’s fans may have swarmed him trying to get to a London theater; but the crooner was a British sanitized version of Elvis, or rather of American imitators of Elvis. The Beatles’ embrace of Black-American musical models, their stark vocal harmonies, and the joyful energy of their performances would distinguish them from docile British crooners like Johnny Leyton.

Readers of the Record Retailer on Thursday 17 January would have observed that “Please Please Me” had nudged into the trade paper’s UK’s top 50 recordings. Unfortunately, that night, unions providing Britain’s gas and electrical service conducted a work slowdown, darkening much of the east and southeast of England, including London. Even Buckingham Palace felt the effects of workers who refused to work overtime without a new contract. For those waiting in the hope that Hugh Gaitskell’s health would improve, this would be a long weekend.

The Beatles on Thank Your Lucky Stars in 1963. Courtesy of Gordon Thompson.

On Saturday 19 January, newspapers carried word that the previous evening Gaitskell had succumbed to what doctors would later describe as an autoimmune disease. (Harold Wilson would succeed him as the leader of the Labour Party.) Much of the nation would be in mourning for the economist turned politician, pouring over papers like the Daily Mirror for information on the widow, the doctors, and the funeral arrangements. These same papers would also list the guests on that night’s edition of the television show Thank Your Lucky Stars, recorded in Manchester on 13 January and tape delayed. The trad-jazz clarinetist Mr. Acker Bilk and his band would headline the show, with appearances by Petula Clark, Mark Wynter, and others. Near the bottom of the bill (added by producer Philip Jones at Dick James’s request), the name “The Beatles” could have referred to a comedy act, for all most readers knew. Viewers would have to wait to see. A little levity would be welcome.

That evening at 5:50 PM, Thank Your Lucky Stars (on ITV) introduced the Beatles to their first national television audience. With the power back, families watching the flickering black-and-white image would have seen four grinning, dark-suited musicians with schoolboy hairstyles playing their instruments and singing (albeit miming) “Please Please Me.” Unlike Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Billy Fury and the Tornados, Marty Wilde and the Wildcats, and innumerable other British acts where a band backed a singer, the Beatles presented a unified, egalitarian ensemble.

As interested teens and others began looking for information on the Beatles, they would have learned of the band’s Liverpool origins, a city that most of Britain associated with the working-class poor. (An estimated 37,000 were unemployed in early 1963, marking it for special economic attention.) As such, the Beatles became an extension of that identity and of a continually growing social discontent with British class attitudes.

That night on Thank Your Lucky Stars, in particular, their hairstyle made an impression. In the UK, young males let their washed hair fall forward naturally; but, when they became men (or aspired to be men), they greased and coifed their hair. The Beatles’ friends in Hamburg had introduced them to the idea that returning their hair to a style characteristic of young teenagers served as a subtle form of cultural subversion. A week after that appearance, the Daily Mirror ran a photo of the four somber Beatles (not the usual pop photo demeanor), staring directly at the camera. The accompanying article advised readers to watch the band in 1963. Indeed.

Gordon Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Beatles and “Please Please Me,” 11 January 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

Autism: a Q&A with Uta Frith

We spoke to Uta Frith, author of Autism: A Very Short Introduction and asked her about diagnosis, the perceived links between autism and genius, and how autism is portrayed in culture.

Autism was not identified before the 1940s. Weren’t there any autistic people before this?

Autism was not a new phenomenon starting in the middle of the 20th century, but it needed people like Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger to point out the striking constellation of poor social communication and stereotypic behaviours for others to see it too. Clinicians used the terms ‘infantile’ or ‘early childhood autism’ and located it among the neglected population of children who were born ‘mentally deficient’. Gradually clinicians became aware that most of this neglected population showed similar problems in varying degrees, and that specialist services were needed to educate children who could not communicate appropriately. They embraced the idea of the autism spectrum. So, just as there has been an increase in the autism spectrum diagnosis, there has been a corresponding decrease in the diagnosis of mental retardation.

But the spectrum idea had even wider implications. The constellation of social impairments and stereotypic behaviours can also be found in people whose intellectual abilities are average or superior. Previously these people would have been regarded as loners or possibly schizophrenic. It turned out that many families had an eccentric uncle, cousin, or grandfather! From the 1990s the diagnosis of Asperger syndrome became hugely popular and preferred to the diagnosis of autism. This popularity also reflected the gradual recognition of outstanding talents in autism, which is particularly visible in people who are also articulate. The loosening of criteria from early childhood autism, which remains rare, to the whole autism spectrum, which is not at all rare, has helped to make autism one of the most frequently used diagnostic categories today. In the US, 1 in 88 people currently have the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.

I have read that some people with Asperger syndrome claim that they do not have a disorder, but that they are just different from ‘neurotypicals’.

Asperger syndrome is a label that is going to disappear from the official diagnostic criteria. This is because clinicians believe that autism spectrum conditions can be diagnosed regardless of severity and regardless of differences in ability. But in its mildest form is autism a disorder? Certainly, the border between autistic and neurotypical is hard to establish. Many of us are a bit geeky and a bit egocentric and a bit obsessive. It could all be just a matter of degree. However, this argument has serious drawbacks. Educational support, psychiatric and other care will only be given to people who have a disorder, and on the whole autistic people do need specialist education and care. My hope is that eventually we might be able to identify clear-cut differences, but not in observable behaviour. The distinctions are likely to be in the underlying mental mechanisms that atypical brain development disturbs in particular ways. But this is still speculation, and arguments about what it means to be autistic will continue.

Are most scientists and artists on the autism spectrum?

A supremely self-assured egocentrism coupled with obsession with a particular idea or technique seems to be the mark of genius. We expect a genius to be oblivious of the trivial aspects of a conventional social life.

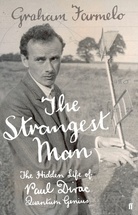

A supremely self-assured egocentrism coupled with obsession with a particular idea or technique seems to be the mark of genius. We expect a genius to be oblivious of the trivial aspects of a conventional social life.  We should be suspicious of this stereotype, because on the one hand, not all artists and scientists are like this. On the other hand, some people may behave like this to persuade other people that they are artists. However, the idea that autism and genius go together has given new impetus to the stereotype. Now we can label the fact that a famous artist or scientist habitually withdraws from company and shows arrogance and blatant socially inappropriate behaviour: it must be autism! However, the likeness to autism is only superficial. There are many reasons for people to be socially odd and to be single-minded to the point of obsession. In the case of the brilliant physicist Paul Dirac, the case can be made that he had Asperger syndrome and Graham Farmelo’s marvellous biography (“The Strangest Man”, 2009) provides a lot of support for this possibility.

We should be suspicious of this stereotype, because on the one hand, not all artists and scientists are like this. On the other hand, some people may behave like this to persuade other people that they are artists. However, the idea that autism and genius go together has given new impetus to the stereotype. Now we can label the fact that a famous artist or scientist habitually withdraws from company and shows arrogance and blatant socially inappropriate behaviour: it must be autism! However, the likeness to autism is only superficial. There are many reasons for people to be socially odd and to be single-minded to the point of obsession. In the case of the brilliant physicist Paul Dirac, the case can be made that he had Asperger syndrome and Graham Farmelo’s marvellous biography (“The Strangest Man”, 2009) provides a lot of support for this possibility.

Autism has been portrayed in books, plays, and in films. Which can you recommend?

Rain Man was made in 1988, is one of the first big movies that portrayed autism, and indeed autism in an adult who had many endearing traits. This was hugely important, to make people aw are of the fact that autistic children grow up to be autistic adults and that they could be heroes. In making this film the director and actors consulted autistic people and their parents. This made the portrayal by Dustin Hoffman exceptionally perceptive.

are of the fact that autistic children grow up to be autistic adults and that they could be heroes. In making this film the director and actors consulted autistic people and their parents. This made the portrayal by Dustin Hoffman exceptionally perceptive.

The most frequent aspect that films and books portray is savant talent, for example, an encyclopedic memory. In some cases this is mere caricature of what might be found in real life. The film I like best never mentions autism, and was made in 1979. It is called “Being There”. Here Peter Sellers portrays a man who outshines sophisticated socialites by his innocence. Mark Haddon with his 2003 best selling book “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime” succeeded in telling a good story from the point of view of an autistic boy. He made a huge contribution to awareness of autism and a more tolerant attitude to autistic people by reaching a large readership.

Uta Frith is the author of Autism: A Very Short Introduction and Autism and Talent. She is Emeritus Professor of Cognitive Development at University College London and Visiting Professor at the University of Aarhus.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: Book jacket of The Strangest Man from Faber.co.uk used for the purposes of illustration; Book jacket of Autism and Talent, all rights reserved by Oxford University Press; Photo still captured from Youtube clip of Rain Man.

The post Autism: a Q&A with Uta Frith appeared first on OUPblog.

January 10, 2013

A comic quotation quiz

Moliere wrote in La critique de l’école des femmes (1663) that “it’s an odd job, making decent people laugh.” In the hopes that 2013 will be filled with delightful oddity and humor, we present this quiz, drawn from the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, 4th edition. Edited by the late Ned Sherrin, the dictionary compiles words of wit and wisdom from writers, entertainers and politicians. Hopefully, by question eight, you will not be able to say “Another day gone and no jokes” (Flann O’Brien, The Best of Myles, 1968)

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Ned Sherrin was one of Britain’s best known broadcasters and raconteurs. The Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations gathers more than 5,000 quotations in a rollicking collection drawn from an international cast of humorists and pundits, ranging from Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Oscar Wilde to Groucho Marx, Monty Python, and Russell Brand.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A comic quotation quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

The changing face of opera

Outreach and innovation are two buzzwords that pop up again and again in relation to established “classical” music institutions such as symphony orchestras and opera companies. In an effort to build younger audiences, many of these institutions have introduced new programs that attempt to do away with the of the concert-going experience, such as expensive tickets or the need for a certain type of attire, that might discourage younger or less experienced listeners from attending.

l’Opéra Garnier, Paris, France

A perfect example is the English National Opera’s initiative “Undress for the Opera”, whose launch last year included such pop icons as Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz) and Terry Gilliam (Monty Python, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas). “Undress” aims at a younger audience by offering affordable tickets, opportunities to meet the cast post-performance, and “club-style” bars, as well as a refreshing mix of new and old works throughout the season (by Mozart, Verdi, Glass, and Michel van der Aa).

While the challenge for large, established companies like ENO is to attract younger audiences, the challenge for the many smaller, newly-established companies out there is simply that of creating work that holds true to an overall mission of performing and creating opera that holds relevance and meaning to contemporary audiences of all ages. Two such companies here in New York City typify the main thrusts of that mission, which involve either: (1) reimagining old works, or, (2) developing new works that stretch traditional conceptions of opera.

Morningside Opera, founded four years ago by a group of Columbia University musicology PhD students, has performed works from Britten to Handel, incorporating their musicological savvy with a modern sensibility that often pushes at the boundaries of decency (much like the original works did in their own time). Case in point is their most recent production, ¡Figaro! (90210), which recasts Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro as “a zany farce about immigration and citizenship in 21st-century America.”

MO’s setting of Cherubino’s aria “Non so più” speaks for itself:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Experiments in Opera, founded two years ago by a collective of composers and performers, on the other hand focuses solely on producing newly composed works. EiO defines opera as “the hybrid space of the theater, performance, installation, dance and storytelling arts”, a definition borne out by performances that have included libretto-as-comic-book (Jason Cady’s Happiness Is the Problem) and works like Matthew Welch’s Borges and the Other, based on Jorge Luis Borges’ short story about a meeting between an older Borges and a younger Borges.

Both of these performances remind us that the genre of opera is not a repository of museum pieces but a living, breathing art. Morningside Opera’s take on Figaro leads us to reconsider an opera that was politically timely in the 18th century to be just as relevant in the 21st. EiO’s performance reveals new ways for opera’s inherently multi-media substance to tell a story for a new age. Both performances demonstrate that the art of opera is still a vital genre, one that continues to inspire composers and performers to break new ground.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The changing face of opera appeared first on OUPblog.

‘Grooming’ and the sexual abuse of children

The word ‘grooming’ has become synonymous with child sexual abuse. It is often used to describe situations of extra-familial abuse, where predatory strangers befriend children who were previously unknown to them. Two of the most prominent social connotations of the term are ‘online grooming’ committed via the internet and ‘institutional grooming’ and abuse committed by those in positions of power and trust.

While ‘grooming’ is a useful short-hand to describe the staged process of befriending children in order to prepare them for abuse and prevent disclosure, it is a term that needs to be used with caution. There is a need to acknowledge the complexities of the onset of sexual offending against children and recognise that there will not always be pre-abuse grooming in every case. The unmitigated use of such terminology, however, can serve to mask these complexities. That being said, grooming of the child, significant others, or the environment is a highly significant and multi-layered variable in child sexual abuse. Unpacking and confronting some of these nuances is vital to protective and preventive efforts.

Within intra-familial contexts, there is often no need to groom prior to the first offence, since in many cases the abuser will already be physically proximate to the child. ‘Familial grooming’, however, can operate not only upon the child but also other protective adults and the environment itself. In the case of father-daughter abuse, for example, the would-be offender may groom or manipulate the mother in order to create the opportunity to be alone with the child and abuse undetected. Similarly, the immediate familial surroundings can also be groomed so that inappropriate behaviours are normalised and the victim ultimately does not recognise themselves as such.

Further complexities arise in relation to the potential cross-over between victimhood and an offending identity. This is particularly the case where abuse occurs on an organisational level. A minority of enquiries into institutional child abuse have demonstrated that victims report being abused by their peers as well as adults where abuse has become part of the organisational culture. Similarly, peer-to-peer grooming also has resonance in the context of ‘localised’ or ‘street grooming’. Recent high profile cases such as those in Rochdale and Oldham demonstrate that young girls may recruit other children and young people into exploitative situations, which in its worst form becomes organised abuse or trafficking.

Such complexities which underlie the onset of sexual offending against children also have broader significance in terms of recognising and challenging inappropriate pro-offending behaviour. It is widely assumed that the adult male is the most typical offender. Sexual offences committed by young people and females, however, together comprise a substantial proportion of official statistics on sexual offending against children (approximately one-third and 5% respectively). These groups of offenders may have different motivations and may initiate abuse in different ways to adult male offenders, whether this is more experimental or relational and less overt.

As an extension of the concept of institutional grooming, sex offenders may seek to manipulate professionals who are charged with their assessment, treatment, or management into discounting their risk to children. However in order to protect children it is vital to remember that all sex offenders act and think differently, and their routes into offending don’t fit any particular. Stereotyping predatory offenders in this way can be dangerous, by detracting our attention from other possible sources of harm to children. Similarly, whole communities can be groomed to view offenders as trustworthy individuals. The ongoing investigation concerning abuse by the late Jimmy Savile highlights potential societal grooming in evidence on a large scale. It is arguable that Savile used his influence to groom not just his victims but society as a whole, abusing his position of trust and authority which was amplified by his celebrity status.

Ultimately, at the tertiary level, the prevention of child sexual abuse in the form of legal and policy frameworks only comes into play once risk is known and identified. Some of these complexities concerning grooming point towards the need for additional social policies at the primary and secondary levels of prevention. Specifically, public health approaches aimed at raising awareness of child sexual abuse and promoting identification and intervention should be targeted at children, families, potential offenders, and wider society. This should involve a continuum of services centring on the creation of a ‘safeguarding’ culture within families, communities, and organisations.

Dr Anne-Marie McAlinden is Reader in Law at Queen’s University Belfast. Her book ‘Grooming’ and the Sexual Abuse of Children: Institutional, Internet and Familial Dimensions published in December 2012.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: School children walking in corridor (motion blur) photo by Bim via iStockphoto.

The post ‘Grooming’ and the sexual abuse of children appeared first on OUPblog.

January 9, 2013

How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’

Very long ago, one of our correspondents asked me how irregular forms like good—better and go—went originated. Not only was he aware of the linguistic side of the problem but he also knew the technical term for this phenomenon, namely “suppletion.” One cannot say the simplest sentence in English without running into suppletive forms. Consider the conjugation of the verb to be: am, is, are. Why is the list so diverse? And why is it mad—madder and rude—ruder, but bad—worse and good—better? Having received the question, I realized that, although I can produce an inventory of suppletive forms in a dozen languages and know the etymology of some of them, I am unable to give a general reason for their existence. I consulted numerous books on the history of the Indo-European languages and all kinds of “introductions” and discovered to my surprise that all of them enumerate the forms but never go to the beginning of time. I also turned to some of my colleagues for help and came home none the wiser. So I left the query on the proverbial back burner but did not forget it. One day, while feeding my insatiable bibliography and leafing through the entire set of a journal called Glotta (it is devoted to Greek and Latin philology), I found a useful article on suppletion in Classical Greek. Naturally, there were references to earlier works in it. I followed the thread and am now ready to say something about the subject.

This introduction might seem unnecessary to our readers, but I have written it to point out two things. First, it sometimes happens that finding an answer to what looks like an elementary question proves a difficult enterprise. Second, the episode has a sobering aspect. The main work on the origin of suppletion is a “famous” book written more than a hundred years ago, and it had important predecessors. “Everybody,” as various authors say, knows it. Well, apparently, the book’s fame is not universal, and one can devote long years to the study of historical linguistics and stay outside the group defined by the cover term “everybody.” Nothing like a question from a student, friend, or reader to prick one’ vanity! And now to business.

Regular forms exist in both grammar and word formation. For instance, many languages use a special suffix to derive the name of a feminine doer from its masculine counterpart. Thus, German Freund “(male) friend” ~ Freundin “(female) friend.” English borrowed from French the suffix -ess; hence actor ~ actress, lion ~ lioness, and many others. But in no language are the words for “girl” and “woman” derived from those for “boy” and “man.” German and Italian have resigned themselves to the existence of Professorin and Professoressa, whereas English does without professoress despite the fact that the number of women on our faculty is now considerable. Man and woman, boy and girl form natural pairs (and their referents form natural couples); yet language keeps them apart, and no one feels the inconvenience caused by the separation.

This is a portrait of Evgeny Zamyatin, the author of the novel We, who already in the early twenties of the past century showed what happens when we becomes the plural of I.

Grammar follows thought and generalizes disparate forms. It makes us feel that work, works, worked, and working belong together. English has almost no morphology left, but it is enough to look at a summary of Greek or Latin conjugations, to see how many forms ended up belonging together. We can only reason backward and keep begging the question. Why do we have separate forms for man and woman? Because each member of the tandem was felt to be unique, rather than “derived.” How do we know that? From the fact that the words are different. The vicious circle is unmistakable. We have no way of deciding why thought combines some entities but separates others. However, certain moves can be explained. For example, horses is the plural of horse (one horse/many horses), but I cannot be multiplied, even though grammar says that we is the plural of I. Therefore, it does not come as a surprise that I and we have different roots. Likewise they is not the plural of he, she, or it.The speakers of early Indo-European who coined the words for “first” and “second” understood them as “the foremost one” and “the next one” and saw no intrinsic connection between what we call ordinal numerals and the cardinal numerals one and two. Suppletive forms in the pairs one/first and two/second turn up in various languages with rare consistency. We wonder why the comparative of good is better. We should ask ourselves what the positive degree of better is! It has never existed. From an etymological point of view, better means approximately “improved; remedied; compensated for.” Good needed a partner meaning “more than good” and better offered its services. We would have preferred “gooder,” but our indomitable ancestors chose to do their work the hard way. They did the same all over the Indo-European world (compare Latin bonus/melior/optimus, and be grateful for the similarity between better and best). Worse probably meant “entangled.” Yet the suffix -er in better (it once existed in worse too) indicates that the comparative force of both adjectives was not a secret.

Perhaps the hardest case is suppletion in verbs. We encounter cases like go/went everywhere. Moreover, the present is affected as often as the preterit. In Italian, the infinitive is andare, but “I go” is vado; the French pair is aller and vais. A look at the entire panorama of Indo-European shows that suppletive forms occur in the conjugation of the verbs for “come; go,” “eat,”, “give,” “take, bring, carry, lead” (those who studied even a bit of Latin had fero/tuli/latum beaten into them at the very beginning), “say, speak,” strike, hit,” “see, show,”, and of course “be, become.” In most cases the relevant forms are individual (like andare and aller), that is, each language invented, rather than inherited, suppletion. The example of English is especially dramatic. The past of Old Engl. gan “go” was eode, a word derived from a different root. In Middle English, went, the historical preterit of wend (as in wend one’s way), superseded eode. The language had a chance of producing a regular past of gan but chose to replace suppletion with suppletion. Even in the carefully edited text of the Gothic Bible (a fourth-century translation from Greek) the preterit gaggida (of gaggan; read gg as ng) occurred once. In Gothic, but not in English. Those who know German may think that gehen/ging “go/went” are related, but they are not. The source of the illusion is the initial consonant g-.

No fully convincing explanation of this phenomenon exists, but some facts can be considered with profit. Early Indo-European did not have some of the tenses we take for granted. A classic example is the lack of the future in Germanic. This statement need not cause surprise. Even today we sometimes do very well without the future: the context does everything for us. Compare: I am leaving tomorrow and If I leave tomorrow…. The difference between the preterit and the perfect can also be hazy: “Did you put the butter in the refrigerator?” or “Have you put the butter in the refrigerator?” The difference is insignificant. Nor does any English speaker bemoan the absence of the aorist. Centuries ago, verbs were often classified according to whether they designated a continuous (durative) or momentary (terminative) action, and occasionally verbs like see (durative) and look (momentary) were later merged within a single paradigm. One thing is “go, walk”; something quite different is “reach one’s destination.” Consider the difference between speak and say. This is probably how went made a union with go. Eode is a word of obscure origin and its inner form meant as little to speakers in the fifth century as it does to us.

The merger of synonyms within one paradigm may not have been the only source of suppletion, but it was an important one. Perhaps the most intriguing question is why languages choose the same verbs and adjectives for defying regular grammar. It appears that the usual target is the most common of them: “good; bad,” “be; come; go; take; eat; speak” and the like (see the list above). Frequency in language always tends to defy regularization. Not every irregular form is the product of suppletion: man/men, tooth/teeth, do/does also have to be learned individually, but none of them is “suppletive.”

We have thrown a quick look at this vexing problem and see that final clarity avoids us, but such is the fate of all things whose past has to be not simply recorded but reconstructed. In any case, I have answered an old question, and my conscience is clear.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Themas well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Boris Kustodiev. Portrait of the author Yevgeny Zamyatin. 1923. Drawing. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How come the past of ‘go’ is ‘went?’ appeared first on OUPblog.

London place names, but not as you know them

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the London Underground. The Metropolitan Railway line, completed in 1863, then running from Paddington to Farringdon Street, was the first part of the London Underground to be built, and was the first Underground railway up and running in the world. More than 2,000 workers built the line, and the first carriages were pulled by steam before electrification was introduced in the early nineteenth century.

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the London Underground. The Metropolitan Railway line, completed in 1863, then running from Paddington to Farringdon Street, was the first part of the London Underground to be built, and was the first Underground railway up and running in the world. More than 2,000 workers built the line, and the first carriages were pulled by steam before electrification was introduced in the early nineteenth century.

Today, the Tube, as it quickly became known, is often an area of frustration in many commuters’ lives, though we have to admit that without it we would be stranded (probably somewhere near the M25). In honour of its longstanding service, here are ten little-known yet interesting facts about the locations in which underground stations can be found today:

Bakerloo, the underground railway line which opened in 1906, had its name coined by the Evening Standard, because it ran from Baker Street to Waterloo. This portmanteau proved very unpopular when it was introduced, with many deeming it rather vulgar and undignified.

Piccadilly, from which Piccadilly Circus gets its name, stems from the nickname for a house belonging to one Robert Baker, a tailor who made his fortune from selling piccadills or piccadillies – a term for collars fashionable at the time.

Maida Vale in West London has even more impressive beginnings than a well-known recording studio. The area (and tube station) gets its name from the Battle of Maida in southern Italy, where British troops were victorious over the French in 1806.

Pimlico, an area and station found in Westminster, is almost certainly a relic from native America. Richard Coates argues that the name is transferred from the Pamlico Indians of North America who lived alongside the Pamlico River, near to Sir Walter Ralegh’s Virginia, founded in 1585-7. It is thought the exotic sounding name of Pimlico returned with one of the colonists.

Rayners Lane station in Harrow opened in 1906. The name is said to come from an old shepherd who lived in a solitary cottage along the lane towards the end of the nineteenth century.

Marble Arch, from which Marble Arch station takes its name, was originally located in front of Buckingham Palace, until the new east range of Buckingham Palace was constructed in its place. The magnificent Arch now famously sits in the middle of a large traffic island.

Old Street was old in the thirteenth century! The street from which Old Street station takes its name was an important route into the city well before the introduction of underground railways.

Chalk Farm, a tube stop and area in North London, is not built on chalk, but rather clay. Called Chaldecotein 1253, meaning ‘the cold cottage(s)’ from old English, which may refer to inhospitable dwellings, the transformation of the original name of this area is simply due to phonetic changes.

Canary Wharf on the Isle of Dogs has absolutely nothing to do with the canary bird, and has much more humble beginnings than the impressive commercial property that it now comprises might suggest. Canary Wharf was the name given to a fruit factory built there in 1937, processing fruit from the Spanish island of Canary (Gran Canaria), from the Latin Canaria insula, that is ‘isle of dogs’, referring to the apparently large dogs once found on the island.

Mile End, called so because it is approximately one mile east of Aldgate, is steeped in British history, being the location for the peasants’ revolt of 1381, when the men of Essex met Richard II and successfully acquired the abolition of feudal serfdom.

The information in this article is taken from A Dictionary of London Place Names by A. D. Mills, now in its second edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) The London Underground in motion. Photo by Jessica C, 2005. Creative Commons License. (via Wikimedia Commons). 2) Marble Arch. Photo by Stephen Mckay, 2007. Creative Commons License (via Wikimedia Commons). 3) Canary Wharf Tube stop. Photo by Mike Knell, 2006. Creative Commons License. (via Wikimedia Commons).

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers