Oxford University Press's Blog, page 988

January 9, 2013

Teaching algorithmic problem-solving with puzzles and games

In the last few years algorithmic thinking has become somewhat of a buzzword among computer science educators, and with some justice: ubiquity of computers in today’s world does make algorithmic thinking a very important skill for almost any student. Although at the present time there are few colleges and universities that require non-computer science majors to take a course exposing them to important issues and methods of algorithmic problem solving, one should expect the number of such schools to grow significantly in the near future.

Algorithmic puzzles, i.e., puzzles that involve clearly defined procedures for solving problems, provide an ideal vehicle to introduce students to major ideas and methods of algorithmic problem solving:

Algorithmic puzzles force students to think about algorithms on a more abstract level, divorced from programming and computer language minutiae. In fact, puzzles can be used to illustrate major strategies of the design and analysis of algorithms without any computer programming — an important point, especially for courses targeting non-CS majors.

Solving puzzles helps in developing creativity and problem-solving skills — the qualities any student should strive to acquire.

Puzzles are fun, and students are usually willing to put more effort into solving them than in doing routine exercises.

Puzzles provide attractive topics for student research because many of them don’t require an extensive mathematical or computing background.

It’s important to stress that algorithmic puzzles is a serious topic. A few algorithmic puzzles such as Fibonacci’s Rabbits and Königsberg’s Bridges played an important role in history of mathematics. Such well-known and intriguing problems as the Traveling Salesman and the Knapsack Problem, which clearly have a puzzle flavor, lie at the heart of the so-called P ≠ NP conjecture, the most important open question in modern computer science and mathematics.

It’s important to stress that algorithmic puzzles is a serious topic. A few algorithmic puzzles such as Fibonacci’s Rabbits and Königsberg’s Bridges played an important role in history of mathematics. Such well-known and intriguing problems as the Traveling Salesman and the Knapsack Problem, which clearly have a puzzle flavor, lie at the heart of the so-called P ≠ NP conjecture, the most important open question in modern computer science and mathematics.

So reader, I would like to challenge you to an algorithmic puzzle, #136, “Catching a Spy”:

In a computer game, a spy is located on a one-dimensional line. At time 0, the spy is at location a. With each time interval, the spy moves b units to the right if b≥0 and |b| units to the left if ba and b are fixed integers, but they are unknown to you. Your goal is to identify the spy’s location by asking at each time interval (starting at time 0) whether the spy is currently at some location of your choosing. For example, you can ask whether the spy is currently at location 19, to which you will receive a truthful yes/no answer. If the answer is “yes,” you reach your goal; if the answer is “no,” you can ask the next time whether the spy is at the same or another location of your choice. Devise an algorithm that will find the spy after a finite number questions.

Leave the answer in the comments below.

Anany Levitin is a professor of Computing Sciences at Villanova University. He is the co-author of Algorithmic Puzzles with Maria Levitin. He is the author of Introduction to the Design and Analysis of Algorithms, Third edition, a popular textbook on design and analysis of algorithms, which has been translated into Chinese, Greek, Korean, and Russian. He has also published papers on mathematical optimization theory, software engineering, data management, algorithm design, and computer science education.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

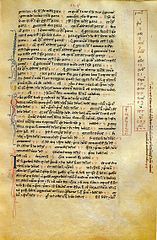

Image credit: Leonardo da Pisa, Liber abbaci, Ms. Biblioteca Nazionale di Firenze, Codice magliabechiano cs cI, 2626, fol. 124r Source: Heinz Lüneburg, Leonardi Pisani Liber Abbaci oder Lesevergnügen eines Mathematikers, 2. überarb. und erw. Ausg., Mannheim et al.: BI Wissenschaftsverlag, 1993. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Teaching algorithmic problem-solving with puzzles and games appeared first on OUPblog.

Reveries of a solitary fell runner

New Year is – or so I am told – a time to reflect upon the past and to consider the future. Put slightly differently, it is a time to think. Is it possible, however, that we may have lost – both individually and collectively – our capacity to think in a manner that reaches beyond those day-to-day tasks that command our attention?

The sheer pace and speed of life; the challenge of somehow stepping outside the storm in order to gain some sense of where you are going (and why); a capacity to pause and think, has arguably become an increasingly precious commodity in an ever-busier world. This is reflected in the changing nature of higher education and the imposition of pressures and expectations that have arguably combined to squeeze-out the space for scholarly thought and reflection. Fifty years ago the founding professor of the Department of Politics at the University of Sheffield, Sir Bernard Crick, used to insist that all students and all members of staff would ‘walk out’ together in the Peak District every Wednesday afternoon in order to nourish both physical and intellectual health. The realities of scholarship in the twenty-first century leave little room for such endeavours (i.e. some space to think).

In ‘taking strength from the hills’ Bernard Crick’s attitude had much in common with those expressed in 1782 by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his Reveries of the Solitary Walker. As a fell runner I appreciate ‘the pleasures of going one knows not where’ and as a writer I understand the manner in which physical activity and a sense of remoteness ‘animates and activates my ideas’. ‘I can hardly think at all when I am still; my body must move if my mind is to do the same’, Rousseau wrote; ‘The pleasant sights of the countryside, the unfolding scene, the good air, a good appetite, the sense of well-being that returns as I walk…all of this releases my soul, encourages more daring flights of thought, impels me, as it were, into the immensity of being, which I can choose from, appropriate, and combine exactly as I wish’. These words capture almost perfectly exactly why I run.

So, where can we rediscover that time to think? The hills and valleys therefore provide exactly that escape, that sense of isolation, that passing moment of release from the instrumentality of grinding social conformity, from the pressures of daily life that many crave but so few appear to be able to achieve. A deeper account of the reveries of the lonely fell runner or walker might engage with Sigmund Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) with its focus on the idea that a fundamental tension exists between the conformity and control demanded by civilization and the instinctual freedom demanded by individuals. Freud therefore leaves us with a core paradox that takes us not just back to Rousseau but forward to more recent works such as Alan de Botton’s Status Anxiety (2004), Barry Schwartz’s The Paradox of Choice (2005) and Oliver James Affluenza (2006) in the sense that the social and economic structures that we have created to protect ourselves from various risks (squalor, want, disease, etc.) seem unable to make us happy. The growth of research and writing on the ‘science of happiness’ in recent years therefore reveals (or more accurately recognises) a longstanding fault line in modern life.

Although Alfred Wainwright (the British fell walker, guidebook author, and illustrator) would have given short thrift to such ‘scientific’ pretensions he was undoubtedly a man who understood the need to draw inspiration and energy from the hills. The paradox that Rousseau reflected on and that caused Wainwright such angst was the realisation that by drawing attention to the reveries of the solitary walker – to the raw and simple beauty of the fells and peaks and moors – they risked destroying the very peace and tranquillity that the countryside provided. And yet in their writing both Rousseau and Wainwright could not conceal the pleasures of escaping – albeit temporarily – the trials and tribulations of modern life. Indeed, at the beginning of his poem ‘Sylvie’s Walk’ (L’Allée de Silvie, 1747), written nearly thirty years before he began the Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire, Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote,

As I wander freely in these groves,

My heart the highest pleasure knows!

How happy I am under the shady trees!

How I love the silvery streams!

Sweet and charming reverie,

Dear and beloved solitude,

May you always be my true delight!

With these words in mind let a lonely (but happy) fell runner offer you a Happy New Year in which you find the space to think.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance at the University of Sheffield. He was awarded the Political Communicator of the Year Award in 2012. Author of Defending Politics (2012), he is also co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of British Politics and author of Multi-Level Governance and Democratic Drift.

Matthew Flinders is now writing a monthly OUPblog column on current affairs and politics; watch out for it on the first Wednesday of every month! Read more of Matthew Flinders’s blog posts and find him on Twitter @PoliticalSpike. And, in case you were wondering, Matthew is a member of Dark Peak Fell Runners!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Trail running. Photo by thinair28 via iStockPhoto.

The post Reveries of a solitary fell runner appeared first on OUPblog.

January 8, 2013

Stay-at-home dads aren’t as new as you think

At the start of this year, the New York Times declared stay-at-home dads a new trend. The numbers are still miniscule compared to stay-at-home moms, but dads are increasingly visible on the internet, if not yet on the playground. There are SAHD blogs, forums for tips and support, and sites that help isolated dads find parenting groups (or all of the above in one place, like the National At-Home Dad Network). Throughout these venues and the mainstream media there are discussions about why men are staying at home with the kids (positive choice? forced by recession?), and what this trend implies about gender definition (is being a SAHD ‘masculine’?). Interestingly, these dads often describe what they’re doing in masculine terms — as an “epic adventure,” “not for the faint of heart.”

What is almost universally assumed in these discussions is that stay-at-home dads are new. They aren’t.

The so-called traditional notion of a father’s place being out in the world, bringing in an income, while the mother nurtures children into young adulthood developed in the western world alongside the industrial revolution, as new opportunities pulled many men out of the home and into offices. American and European periodicals and fiction from the first half of the nineteenth century responded to rapid and sometimes unsettling economic changes with idealized, comforting images of the mother as an “angel of the house” and the father as a confident breadwinner. The overwhelming ubiquity of such images has taught us to view these projections as “traditional,” universal roles. It seems to make intuitive sense: only women can bear children and breastfeed babies, after all. But the rest of childcare can, and over time often has, been done by others: servants, relatives, friends, neighbors, and sometimes fathers.

In the middle of the nineteenth century when images of idealized domesticity were most broadly promoted—when it was, in most parts of Europe and America, most costly for men or women to openly act against type—we still find men who loved being fathers and women who had ambitions in the public sphere. But do we see an actual stay-at-home dad who does not work outside the home, and who spends years nurturing his children while his wife brings home the bacon?

As it turns out — yes.

But to find him we do need to leave the middle-classes of western Europe and America. Those societies had restrictive property laws that prevented most married women from managing property on their own and inhibited women’s opportunities outside homemaking. At the same time, those societies enjoyed booming industrial economies where men could earn a good income in a great variety of occupations.

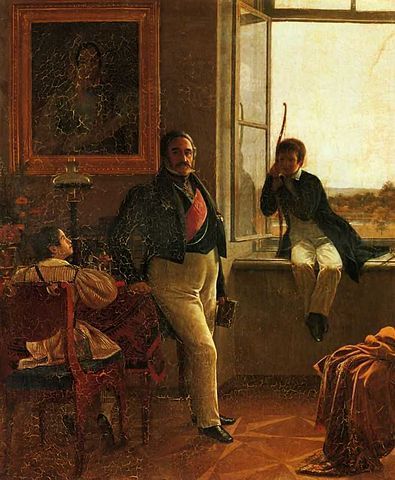

In Imperial Russia, by contrast, women enjoyed the right to manage their own property, and there was no commercial middle class in the western sense. A large majority of the Russian population were peasants, many of them enserfed. Nobles handled the government apparatus and the management of those vast peasant-filled lands. But very few Russian nobles were like the people you see in the latest remake of Anna Karenina, waltzing around ballrooms dripping jewels and getting entangled in sticky love affairs. The majority had only small to modest incomes. Middling-income nobles often struggled to make ends meet for their serf dependents as well as for themselves. One such Russian nobleman, Andrei Chikhachev, kept a diary about raising his two children. After his children were older, he wrote to newspapers about how ideally he and his wife had arranged their affairs, and argued that their peers who were not doing the same already should strive to do so.

Портрет А.С.Лошкарева с детьми. Крендовский Евграф Федорович. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Andrei’s wife, Natalia, likewise kept a diary and from it we know that she spent her days managing the serf labor and finances of their estates. She was so successful that over the first fifteen years of their marriage, while the children were young, she not only provided for her family and hundreds of dependents, but brought the Chikhachev family out of debt. (Andrei had inherited a mortgage on 90% of his part of their property; Natalia separately owned about as much, without debt.)While she was doing this, Andrei taught their two children their lessons up to the age of twelve, when they went to Moscow for formal schooling. He played with the children, invented games for them, and doted over their progress. He also carried out a rigorous program of self-study to qualify himself to instruct the children in catechism, history, geography, literature, and French (while an uncle taught them mathematics and tutors were brought in for German and Latin).

Childrearing was Andrei’s vocation, and far from being emasculated by it, he wrote of it as the ideal masculine role. He reasoned that raising a child was an intellectual and moral task, which is to say, an abstract task. Abstract thinking was, in Andrei’s mind, both inherently masculine, and existed outside the home in the metaphorical sense. While Natalia managed complex finances and gave Andrei an allowance, her work remained practical and within the “home” (which they understood as encompassing their scattered agricultural estates). Thus even through a mid-nineteenth century lens colored by the literature of domesticity, Andrei could understand his wife’s financial and management role as ideally feminine, and his own nurturing role as ideally masculine.

While Andrei and Natalia’s arrangement may not have been precisely typical, their friends and neighbors found nothing in it to raise their eyebrows about, which is a striking contrast to the attitudes of comparable privileged classes in, say, England or the United States in the same period. And given the fact that many Russian women did manage their own property, the arrangement may not have been as unusual as we think. The Chikhachevs likely came to their roles from the same reasons that some men are choosing to be stay-at-home-dads today; they were in debt and their society offered few lucrative opportunities for Andrei, but little in the way of obstacles to Natalia. The Chikhachevs’ story tells us, if nothing else, that the Victorian stereotype was always just a stereotype, and after two hundred years we can perhaps finally put it aside, and embrace a more flexible reality.

Katherine Pickering Antonova is the author of a microhistory about the Chikhachev family, An Ordinary Marriage: The World of a Gentry Family in Provincial Russia. She teaches Russian history at Queens College, City University of New York. Read Katherine Pickering Antonova’s blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Stay-at-home dads aren’t as new as you think appeared first on OUPblog.

What do mathematicians do?

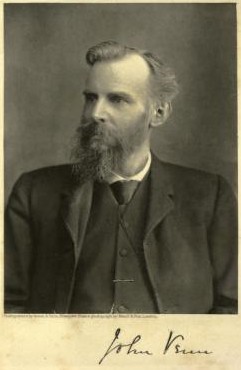

Writing in 1866, the British mathematician John Venn wrote, in reference to the branch of mathematics known as probability theory, “To many persons the mention of Probability suggests little else than the notion of a set of rules, very ingenious and profound rules no doubt, with which mathematicians amuse themselves by setting and solving puzzles.” I suspect many of my students would extend Venn’s quip to the entirety of mathematics. Often they seem to believe, upon entering my classroom for the first time, that a tacit agreement exists between us. They will dutifully memorize whatever rules I give them and apply them with machine-like accuracy at test-time, but to expect anything beyond that is considered a serious breach of etiquette.

Writing in 1866, the British mathematician John Venn wrote, in reference to the branch of mathematics known as probability theory, “To many persons the mention of Probability suggests little else than the notion of a set of rules, very ingenious and profound rules no doubt, with which mathematicians amuse themselves by setting and solving puzzles.” I suspect many of my students would extend Venn’s quip to the entirety of mathematics. Often they seem to believe, upon entering my classroom for the first time, that a tacit agreement exists between us. They will dutifully memorize whatever rules I give them and apply them with machine-like accuracy at test-time, but to expect anything beyond that is considered a serious breach of etiquette.

I held such views myself, once upon a time. That is why my first visit to the annual Joint Mathematics Meetings, as an undergraduate student in the early nineties, was such an eye-opening experience. This is the largest mathematics conference of the year, held every January in a different city. Almost two decades later, I am still consistently amazed by the sheer variety of things that mathematicians study. Browsing through the program for this year’s edition, which is being held in San Diego, I notice that there are sessions on complex dynamics and celestial mechanics. Continued fractions get their own session, as do coverings of the integers, and frontiers in geomathematics. Financial mathematics gets a session. So does graph theory, and also the history of mathematics. If you prefer, you can go in for the real jawbreakers. They have titles like, “Advances in General Optimization and Global Optimality Conditions for Multiobjective Fractional Programming Based on Generalized Invexity.” For me, reading the program is like listening to opera. I may not understand all the words, but it sure sounds good!

This conference is called the Joint Mathematics Meetings, because it is held jointly between the two major mathematics organizations in the United States: The American Mathematical Society (AMS) and the Mathematical Association of America (MAA). The AMS generally concerns itself with the profession of mathematics and publishes several highly prestigious research journals. The MAA, by contrast, generally focuses on the educational aspects of mathematics. The sessions I listed above are directed towards researchers and are organized by the AMS. MAA sessions tend to have gentler titles. This year they are hosting a session on the beauty and power of number theory; another one on writing, talking, and sharing mathematics; still another on mathematics in industry; and, my personal favorite, a session called, “Where Have All the Zeros Gone?”

The sessions, however, are only the tip of the iceberg. There are also keynote talks featuring the alphas of our profession. In my experience, the main purpose of these talks is to remind you that, your PhD notwithstanding, there are mathematicians out there who are way smarter than you are. There is also the employment center, populated by eager job-seekers who stand out clearly from the other conference attendees, because they are well-dressed. There is also the exhibition center, in which every mathematical publisher on the planet shows off its latest books. For an impulse buyer like me, this is a dangerous place.

Which brings me back to the John Venn quote with which I started and the question at the top of this essay. Yes, I suppose we do spend a lot of time setting and solving puzzles. We dutifully apply the rules of proper inference to the abstract objects that have caught our fancy, thereby producing publishable theorems. That, however, is really a very small part of what mathematicians do.

You see, more than anything else, to be a mathematician is to be part of a community. Whatever else it is, mathematics is a social activity undertaken by human beings to further human goals and purposes. The main point of the conference is not to transact mathematical business, though that is certainly important. Rather, the point is to socialize, to renew old friendships, and to engage in casual conversations. The point is to remind you that mathematics is not about ivory tower theorizing, but about being part of a community that is united by its love for, and its belief in the importance of, mathematics. This applies whether your focus is on pure mathematics or applied mathematics. It does not matter whether you prefer teaching, research or community outreach. It includes elementary school teachers showing grade-schoolers the mechanics of basic arithmetic, high school teachers giving students their first taste of higher-level math, and graduate school professors at the frontiers of modern research. It also includes the students who will form the next generation not just of professional mathematicians, but of mathematically informed lay people as well.

All are part of the same community, and all are essential to the continued health of our discipline.

Jason Rosenhouse is Associate Professor of Mathematics at James Madison University. His most recent book is Among The Creationists: Dispatches from the Anti-Evolutionist Front Lines. He is also the author of Taking Sudoku Seriously: The Math Behind the World’s Most Popular Pencil Puzzle with Laura Taalman and The Monty Hall Problem: The Remarkable Story of Math’s Most Contentious Brain Teaser. Read Jason Rosenhouse’s previous blog articles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only mathematics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: John Venn. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What do mathematicians do? appeared first on OUPblog.

On music and mentorship

As part of my freelance existence, I mentor a number of musically gifted teenagers. They operate in a varied and difficult-to-negotiate world, especially if they possess a great talent but are not in a highly protected ‘hothouse’ environment. As musicians, they are expected to behave with total professionalism, changing from kids having fun on a beach to soloing in front of 10,000 people in a few minutes. (I have seen them do just that on many occasions.)

Yet as teenagers they are not accorded much degree of autonomy. They are ordered around by bells and beeps, and given a regimented life with its constant requirements to do things well and in a timely manner while showing creativity and learning. Any failure to meet deadlines is generally met with public reprimand and possibly punishment. This is all with the best of intentions of course; the teacher knows that there are various grade exams that will arrive and underperformance in these will quickly result in the student learning the meaning of the consequences of actions or inaction.

Yet as teenagers they are not accorded much degree of autonomy. They are ordered around by bells and beeps, and given a regimented life with its constant requirements to do things well and in a timely manner while showing creativity and learning. Any failure to meet deadlines is generally met with public reprimand and possibly punishment. This is all with the best of intentions of course; the teacher knows that there are various grade exams that will arrive and underperformance in these will quickly result in the student learning the meaning of the consequences of actions or inaction.

However, teenage musicians create music that is expressive and personal and sometimes not bounded by any ‘rules’. They perform and practice sustaining a performance persona that can communicate, taking control of a ritualized social situation. They wear their music like they wear their clothes – available at any time to structure and communicate their mood.

It was expected that this ‘born digital’ generation would have their musical lives ordered and organized too by the proliferation and integration of digital tools. Their music would be sorted into playlists to match their mood. They would never lose their contacts backed up automatically by cloud computing. They would use the Internet to source whatever they needed.

My experience and research shows that the teenager’s creative space lacks such regimentation. A teenager’s bedroom is a pretty good model: it is highly personal, comforting, unstructured and creative. It may contain uneaten food, dirty clothes, and various things that an adult would think embarrassing but it is a place for experimentation, slipping seamlessly (and frustratingly for adults) between that responsible adult world and the tiny tantrum.

We adults struggle to understand this world. It seems irrational, self-centered, indulgent, and full of music that is mostly too everything. But from the teenager’s perspective, they are at some arbitrary point, suddenly expected to conform, to act their age, and even like their parent’s music perhaps!

In the past four years, working on a project to bring together the widest range of writing about the musical world of children has provided a unique opportunity to see the world from their perspective. We have only just begun to ask about this world in terms that the teenager might recognize and respond to, to see how music is integral to so many aspects to becoming adult and expressing who and what we are. Our theories and models will struggle as children struggle with the incredible variety of social settings, cultural expectations, opportunities, and requirements they encounter.

Trevor Wiggins, co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Children’s Musical Cultures, with Patricia Shehan Campbell. Trevor Wiggins is a Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London and an independent musician and music educator. He has a particular interest in the interconnections between Ethnomusicology and processes of pedagogy and music education, drawing particularly on his long-term fieldwork in northern Ghana. He has published numerous articles, CDs and pedagogic materials that explore this area and has delivered lectures and workshops on these topics in many countries. He is currently co-editor of the journal Ethnomusicology Forum.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A young Asian woman with her clarinet. Photo by tmarvin, iStockphoto.

The post On music and mentorship appeared first on OUPblog.

January 7, 2013

Words of 2012 round-up

While most people are getting excited for the start of awards season on Sunday with the Golden Globes, the season has just ended for word nerds. From November through January, the Word(s) of the Year announcements are made. I’ll let you decide who is the Golden Globes, BAFTAs, SAGs, National Film Critics Circle, etc. of the lexicography community. Just remember YOLO — because it appeared on every list.

Oxford Dictionaries was first off the mark with omnishambles for the UK and GIF (verb) for the USA respectively. (13/11)

Marc Weisblott appears to be the only person who put forth suggestions for Canada’s Word of the Year. (13/11)

Dictionary.com chose bluster for the combination of its political and meteorological uses. (19/11)

Watture (electric car, watt + voiture) was named (French) Word of the Year by Festival XYZ. (23/11) The other French Word of the Year, twitter, was decided at the Festival du Mot. (25/05)

Dennis Baron of Web of Language and A Better Pencil chose #hashtag. (02/12)

Merriam-Webster chose two Words of the Year: socialism and capitalism. (05/12)

Huffington Post selected sideboob given its prevalence in their coverage this year. (06/12)

Zoë Triska of Huffington Post hates YOLO. I’m getting the impression everyone does. (10/12)

Nancy Friedman (aka Fritinancy) had a list of 14 WOTY words and is I believe the only person to include Ermahgerd. (12/12)

Australian National Dictionary Centre’s Word of the Year 2012 was green-on-blue: (used in a military context) an attack made on one’s own side by a force regarded as neutral. (13/12)

Khaya Dlanga made some suggestions for South Africa’s Word of the Year. (13/12)

Rettungsroutine (routine rescue) is the Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache (German Language Society) Word of the Year. (14/12)

Ben Zimmer’s Boston Globe column included many WOTY candidates. (16/12)

Cambridge Dictionaries looked at its top words for each month of 2012. (18/12)

Jen Doll at the Atlantic Wire presented “An A-to-Z Guide to 2012′s Worst Words”. (18/12)

LGBT activist Stampp Corbin suggested demographics is WOTY 2012. (19/12)

Collins Dictionary selected 12 words of the year (one for each month) including Gangnam Style, 47 percent, and Romneyshambles. (20/12)

Linguist Geoff Nunberg’s Word of the Year is Big Data. (20/12)

Vlae Kershner and the readers of SFGate selected fiscal cliff. (20/12)

Lake Superior State University released their annual list of words that should be banished in 2013. (31/12)

Professor Holly R. Cashman proposed LGBTQ WOTYs. (02/01)

The American Name Society chose Sandy as their . (04/01)

And finally, the American Dialect Society Word of the Year is… hashtag. Check out Ben Zimmer’s recap of the process (unfortunately not in GIF form, #disappointed). (04/01)

The Macquarie Dictionary Word of the Year (Australia) has yet to be announced, but I can contain WOTY no longer.

Please let me know if I missed any other WOTYs in the comments below, and your suggestions for which dictionary or person is which film awards ceremony and why.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Words of 2012 round-up appeared first on OUPblog.

Responsible Wealth should oppose the GST Grandfather Exemption

By Edward Zelinsky

In the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, Congress and President Obama recently agreed that the federal estate tax will be imposed at a 40% rate on estates over $5,000,000. On 11 December 2012, a group of affluent Americans, organized under the banner of Responsible Wealth, had called for a stronger federal estate tax. In particular, Responsible Wealth urged that federal estate taxation begin at a rate of 45% on estates over $4,000,000.

Neither the American Taxpayer Relief Act nor the Responsible Wealth statement addressed a particularly egregious loophole of federal transfer taxation, namely, the grandfather exemption of the generation skipping tax (GST). Under this exemption, the GST does not apply to trusts established before 25 September 1985. By virtue of this GST exemption, older wealth is immunized from federal transfer taxation while otherwise equivalent new wealth is taxed under the estate tax.

Because Responsible Wealth includes heirs to older fortunes, such as Dr. Richard Rockefeller and Dr. Abigail Disney, Responsible Wealth is uniquely positioned to address this unfairness of the federal tax statute. As part of its self-proclaimed mission to strengthen the federal estate tax, Responsible Wealth should lead the effort to repeal the GST grandfather exemption and thereby subject old wealth to the same transfer taxation as new wealth.

While the details are complex, the basic story is not. It was once both easy and common for wealthy individuals to bestow fortunes on their children, grandchildren, and perhaps even their great-grandchildren free of any further federal estate taxes. This multi-generational tax immunity was achieved through so-called generation-skipping trusts. Such trusts distribute income and principal to the offspring of wealthy individuals without that lucky offspring ever paying any further estate taxation.

The moniker “generation-skipping” is misleading. Under such trusts, the benefits of wealth don’t skip any generation. Just the estate taxation of wealth skips generations as the estates of individuals dying after the founder of the family fortune pay no further federal estate taxes.

Consider, for example, Dr. Disney’s family. Her fortune stems from her grandfather, Roy O. Disney. Mr. Disney, along with his brother Walt, created an entertainment behemoth including valuable icons of American culture. It is likely that, when he died in 1971, a man as wealthy and well-advised as Roy O. Disney left his fortune to his family in a generation-skipping trust. (His brother Walt did.) If so, in 2009, when Roy O. Disney’s son Roy E. Disney died, no estate tax was levied on his death. That trust (assuming the common practice) now continues for Dr. Disney, the granddaughter of Roy O. and the daughter of Roy E. It is likely that, when the generation-skipping Disney trust passes to Dr. Disney’s heirs, they too will owe no further estate taxes.

In 1986, Congress decided that this kind of multi-generational estate tax avoidance is unacceptable. Accordingly, Congress supplemented the federal estate tax with the GST to block these kind of tax-avoidance arrangements. The GST is a variant of the estate tax and removes the tax advantages of generation-skipping trusts. Together, the estate tax, now supplemented by the GST, requires wealthy families to pay federal tax at least once every generation — unless a generation-skipping trust was created before 25 September 1985.

In those cases of older wealth, neither the federal estate tax nor the new GST applies. Thus, any generation-skipping trust created by Roy O. Disney before his death enjoys continuing federal tax immunity well into the 21st century by virtue of the GST grandfather exemption for trusts in existence on 25 September 1985.

Whatever the policy merits or political need for the GST grandfather exemption in 1986, it has outlived its usefulness. If new, i.e., post-1985, wealth is to be subject to estate taxation once every generation along the lines recently adopted by Congress and advocated by Responsible Wealth, older wealth should be subject to such taxation also. The members of Responsible Wealth who benefit from the GST grandfather exemption are uniquely positioned to call for the abolition of the exemption from which they and their families unfairly benefit. They should do so.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Responsible Wealth should oppose the GST Grandfather Exemption appeared first on OUPblog.

Holy Court of Owls, Batman!

My name is Mark Peters, and I am a Batman-aholic.

My name is Mark Peters, and I am a Batman-aholic.

I blame Christopher Nolan. Between The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises, I felt an insatiable thirst for more Batman than Mr. Nolan was providing. In my desperation, I turned to a childhood addiction: comic books. I was always more of a Marvel guy, but I had read the holy trinity of classic Batman graphic novels: Batman: Year One, The Dark Knight Returns, and The Killing Joke. I soon learned these were only the tip of the Batberg.

As I re-plunged into comics, I discovered Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s The Long Halloween (which partly inspired The Dark Knight), Ed Brubaker and Greg Rucka’s The Wire-esque Gotham Central, and Neal Adams’ warped Batman: Odyssey. I’m currently absorbed in Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s Death of the Family story, and I’m catching up on animated fare like Return of the Red Hood. Even the somewhat disappointing The Dark Knight Rises couldn’t dampen my addiction. I’m hooked.

So I figured I’d combine my new obsession with my old obsession: lexicography. Here’s a look at some items from the Bat-lexicon that deserve wider use. These terms — which aren’t as well-known as Batcave and boy wonder — would be fine additions to your linguistic utility belt.

Zur-En-Arrh

Back in the bonkers days of 1950s Batman, Zur-En-Arrh was a faraway planet where a scientist named Tlano became a Batman-inspired crime-fighter: the Batman of Zur-En-Arrh. When Tlano transported Batman to Zur-En-Arrh, Batman gained Superman-like powers, because of Zur-En-Arrh’s sun and because the 1950s were cuckoo-bananas times for Batman. Grant Morrison paid homage of Zur-En-Arrh in the recent Batman R.I.P storyline, which also revived the imp known as Bat-Mite. I’m confident Zur-En-Arrh would be perfect as a celebrity baby name or civilian safeword.

the Court of Owls

Batman villains the Joker, the Riddler, the Penguin, Two-Face, and Catwoman are all household names, but unless you’ve been keeping up with the comics, you likely don’t know about the Court of Owls. Playing on nature’s owl vs. bat rivalry, the Court of Owls is an old, secret, villainous (duh) group that Batman discovers in the awesome 2011-2 series of the same name. Court of Owls could succeed as a lexical term, especially among the conspiracy-driven. Why can’t you hold down a job? The Court of Owls. Who really planned 9/11? The Court of Owls. Who does Obamacare really help? The Court of Owls.

Shark Repellent Bat Spray

This handy doohickey appeared in Batman: The Movie, featuring Adam West and the rest of the gang from the 1960s TV series. This glorious, ridiculous contraption is as specific as the Batarang — the Swiss Army knife of bat-gadgets — is multidimensional. However, I’m told it also acts as a Bat Morning After Pill.

From Batman no. 124 (June 1959). Writer: Arnold Drake. Penciller: Sheldon Moldoff. Inker: Charles Paris. Image courtesy of DC Comics. All rights reserved.

Whirly-BatAlong the same ludicrous lines, here’s a gadget — from the comics, this time — that looks like the flying equivalent of Job Bluth’s Segway. In The Essential Batman Encyclopedia, Robert Greenberger describes the Whirly-Bat as a “one-person flying vehicle,” dryly adding, “Its flight specifications were never recorded.” Maybe that’s because this gadget, which debuted in 1958, was quickly and appropriately forgotten. However, according to Daniel Wallace’s Batman: The World of the Dark Knight, “It is fully collapsible and can be packed in the trunk of the Batmobile.” Please, copyright gods, allow a picture of the Whirly-Bat to appear in this column.

Ace the Bat-Hound

Ace was an abandoned German shepherd the dynamic duo adopted in 1955, and unlike the Whirly-Bat, Ace has popped up in the comics more frequently over the years. Given the wide use of German shepherds as police or terrorism dogs, Ace might be the least implausible item on this list. In Batman and Robin, Batman recently gave a Great Dane named Titus to his whacko son Damian, so perhaps there’s a new Batdog in the making. Awesomely, there’s also a Batcow.

Damian Wayne

Who’s Damian, you say? Casual Bat-fans know good guys Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson, Commissioner Gordon, and Alfred Pennyworth, but the latest addition to the Bat-family is a doozy. The not-so-subtly-named Damian is the child of Batman and villain Talia al Ghul. Batman didn’t know Damian existed till the kid was ten: till then, he was raised by his mom and the League of Assassins, which means Damian is also an assassin, not to mention one of the least well-adjusted tykes in the world. To sum up, Batman — who never kills — has a son who is a killer. This leads to hysterical conversations in which Batman scolds Damian (who is currently Robin) about killing the way other parents scold their kids for leaving out the milk. I’m not sure how his name could be part of the lexicon, but Damian is a good reference point when your own children forget their chores or murder a supervillain.

flink

What’s flink you say? It’s a word I would never have known about if my buddy Shane hadn’t lent me Batman: The Dailies 1944-1945, which collects the short-lived newspaper strip. Flink was an all-purpose word used by hitman Jojo the Flinker. In a strip that ran on January 17, 1945, Jojo demonstrates the word’s versatility, using it as adjective (“Not fair treatment, ol’ pal. The ‘flink treatment’!”), verb (“I ain’t gonna flink ya right away.”), and interjection (“But I only trust a guy once—an’ then—flink!!”). As an expert marksman, most of JoJo’s flinkage related to shooting people. In the intro to this collection, writer Al Schwartz said of flink, “I didn’t get that from anywhere in particular. It was the idea of putting something into his speech that would be characteristic.” I love this flinkin’ word. It deserves a revival, for flink’s sake.

Mark Peters is a lexicographer, humorist, rabid tweeter, and language columnist for Visual Thesaurus. He also writes Lost Batman Tales.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language, lexicography, word, and etymology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Dark Knight Rises movie poster used for the purposes of illustration in a commentary on the work. (2) Whirly-Bat from Batman no. 124 (June 1959). Writer: Arnold Drake. Penciller: Sheldon Moldoff. Inker: Charles Paris. Image courtesy of DC Comics. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission. (Thank you to Scott Bryan Wilson and Steve Korte of DC Comics for the image!)

The post Holy Court of Owls, Batman! appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten revision tips from the OUP student law panel

For many students it’s that time of year again when the festive cheer has ended and they are brought back down to earth with a bump by the prospect of mountains of revision to plough through.

To help, we asked some students from the OUP Student Law Panel for their top revision tips that help them survive the exam season, and have a collection of their responses for you below.

Whatever degree you’re studying, flash cards are definitely the way forward during exam season. Whether you’re writing out complex equations, facts and dates, or useful quotes, flash cards are great. Test yourself, test your housemates, and pin them up everywhere! Charlotte Elves, 1st year, University of Birmingham

Try to find a willing victim to talk through your revision topics with you. Not only will giving small presentations help you realise whether you have a grip on the information, it will also help you organise your thoughts on the spot which will assist in planning any essays. Adam Fellows, 1st year, Northumbria University

Revision requires self-restraint. From indulgence, from slothfulness, from procrastination. But such an ascetic life can quickly become draining and, in the end, self-defeating. So my tip is to take unscheduled liberties. A sensible plan with healthy study breaks is tedious. A ridiculously intensive plan with minor rebellions is refreshing. James Manwaring, 3rd year, University of Warwick

Observe, imagine, and relate. For example, a ‘Private’ sign outside a farm reminds me of trespassing and triggers my imagination of different scenarios. I then think about what the relevant laws and the cases are. This not only consolidates your understanding, but also raises some unrecognised confusions. Tina Mok, 1st year, University of Nottingham

I would always recommend using a wide range of textbooks in revision. In particular, I use small revision guides and also more in-depth textbooks to ensure I cover all the points needed for my exam. I then use these bits of information to create a spider diagram, which contains all the cases, theories, and reports from a variety of different sources. Emma Bray, 3rd year, University of York

I first make comprehensive revision notes and then start by repeatedly copying them out until I can remember the information. Each time, I cut the total words I write by half until I can summarise an A4 page in a handful of words. Then, a parent or friend tests me vocally. James Robins-Johnson, 1st year, University of York

Try to remember any relevant cases by associating each one of them with an image or memory so that they are easier to recall during an exam (aka neural networking). Waqar Aziz, 1st year, University of Salford

Make the best use of seminar preparation and attendance, as they condense all the information given in lectures and the exams are usually based around topics which are discussed in seminars. Leanne Newton, 2nd year, Swansea University

The revision method that worked well for me was to create mind-maps on the separate topics of the subject I’m doing. I made them colourful and pinned them to my wall so that I saw them. I also think that a really good way of remembering cases is to make an A3 page and get pictures which relate to each case. That way I remembered the case by remembering the picture that went with it. Laura Ashmore, 1st year, University of York

For me the most important study tip is to make a plan of what and when you are going to study. This ensures you can maintain an organised routine and allows for you to keep an overview on your progress at all times. Tobias Hoecker, 1st year, University of Warwick

For more help on getting through your law revision, look no further than OUP’s two revision guide series, Concentrate and Q&A, with a series of new editions being released this spring.

Paul Bramwell is a Marketing Assistant for higher education law books at Oxford University Press. The OUP Student Law Panel is an invaluable resource for the UK Higher Education team. The feedback they provide in response to surveys on a variety of topics including study methods and features of OUP products is very influential in directing the future of OUP’s publishing and marketing projects.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by a sea of revision, let OUP’s Questions and Answers series keep you afloat! Written by experienced examiners, the Q&As offer expert advice on what to expect from your exam, how best to prepare, and guidance on what examiners are really looking for. Revision isn’t always plain sailing, but the Q&As will allow you to approach your exams with confidence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: A Student of the University of British Columbia studying for final exams, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Ten revision tips from the OUP student law panel appeared first on OUPblog.

Space weather

We are all used to blaming things (rightly or wrongly) on the weather, but now it seems that this tendency has been extended to space weather. Space weather, for those who are uncertain, describes the effects that flares and other events on the Sun produce on Earth.

Consult many of the sites on the World Wide Web that are devoted to events on a particular day in history, and you will be told that on 16 August 1989, a geomagnetic storm caused the Toronto Stock Exchange to crash. The trouble is that this is an urban myth. The Toronto Stock Exchange did crash that day, but because of hardware and software failures, not because of a geomagnetic storm.

Why did they blame the Sun? Probably because 1989 did see a catastrophic event in Canada caused by a geomagnetic storm, which has even been described as ‘The Cosmic Wake-up Call’. Less kindly perhaps, it might be called ‘The Day Quebec Hydro’s Network Collapsed’, when 6 million people were suddenly plunged into darkness, left without electricity, stranded in lifts, woke to unheated homes, and went without a hot breakfast.

But what is a geomagnetic storm? Let’s take that disastrous event in March 1989 as an example.

On 6 March 1989, the Sun’s rotation carried into view a gigantic sunspot group, about 70,000 km across. (That’s big, very big. Sunspot groups don’t come any larger.) Between 6 and 19 March it was phenomenally active, with at least 195 explosive solar flares, with 11 of the most extreme ‘X-class’ flares. One that occurred on 6 March emitted a surge of charged particles and X-rays that overwhelmed the detectors on the Geostationary Orbiting Environmental Satellite 7 (GOES-7). But that was nothing compared with what happened on 10 March. There was a rare ‘white-light flare’ – only a few of which have ever been seen – of extreme intensity, and a coronal mass ejection (CME), directed straight at the Earth.

It takes time for the plasma ejected in a CME to reach the Earth, and the flood of charged particles began to arrive on 12 March. By the middle of 13 March, the magnetopause, the boundary that separates the Earth’s magnetosphere (where the Earth’s magnetic field is dominant) from the interplanetary region governed by the Sun’s magnetic field and the solar wind, had been compressed from its normal distance of about 55,000 km on the sunward side, to about half that amount. Geostationary satellites, orbiting at 35,500 km from the Earth, and normally protected from the solar wind, were exposed to the full blast of particles. These can severely damage detectors and computers on board satellites and sometime even render them completely useless.

Many Earth-observation satellites, including the meteorological, polar-orbiting satellites are much closer to Earth, in what are known as low Earth orbits (LEO), which are generally taken to be at altitudes of 160 to 2000 kilometres. The International Space Station (ISS) is in an orbit that carries it between 320 and 400 km above the surface. Satellites in LEO may still be damaged by the intense flux of charged particles occurring during solar storms, and there are often communications problems. (Some GPS signals were affected by the March 1989 storm.) But there is yet another effect, because, although low in density, there is some residual atmosphere at these altitudes.

The charged particles collide with atoms and molecules in the atmosphere, giving rise to aurorae and, at the same time, cause heating of the upper atmosphere. This expands outwards, raising the density at satellite altitudes and thus slowing down LEO satellites, and causing their orbit to decay more rapidly. Some may even re-enter and burn up. In the March 1989 storm, the density increased to five to nine times its normal level. One satellite started tumbling uncontrollably.

Under relatively quiet conditions, aurorae are most frequently seen in two zones, known as the auroral ovals, roughly centred on the magnetic poles, but reaching lower latitudes on the midnight meridian. These auroral ovals may be regarded are roughly fixed in space as the Earth rotates beneath them. There is always a flow of charged particles, known as the auroral electrojet, in the ionosphere following the route of the auroral ovals.

When a major geomagnetic storm occurs, the particle influx into the ionosphere not only causes extreme changes in radio communications, but the electrojets become exceptionally strong and the whole system expands towards the equator.

Green aurora. © Denis Buczynski.

During the extreme geomagnetic storm of 13 March 1989, intense red aurorae were seen over the whole of the southern United States and as far south as Mexico, Cuba, and the Cayman Islands. (Red aurorae, rather than the more common green form, often accompany major geomagnetic storms.) The auroral oval around the south magnetic pole also expanded, and aurorae were seen in Australia and New Zealand, and even as far north as South Africa, where aurorae are extremely rare.

Red aurora. © Alex Cherney terrastro.com.

But that is not all. When the currents flowing in the electrojets strengthen, they create correspondingly strong electrical currents at the Earth’s surface. All electrical equipment, such as the major transformers used in high-voltage transmission lines, are ‘earthed’, that is, bonded electrically to the underlying ground. The immense induced currents created by a geomagnetic storm may find it easier to flow through man-made electrical connections and transmission lines than through the Earth’s surface. This is especially the case where, as in Sweden and (in particular) in Canada, the underlying rocks are granite or similar rocks, which have poor electrical conductivity. On 13 March, the immense currents surged through Hydro Quebec’s transmission lines, burning out some transformers and causing other fault-sensing equipment to disconnect whole sections of the transmission grid. The ‘knock-on’ effect caused damage to electrical equimpment as far south as New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. Quebec Hydro’s whole system failed, leading to a blackout over a large part of Canada and some of the northeastern United States. Blackouts also occurred in Sweden, and the grid in the United Kingdom was affected, but there no major interruptions took place.

Such major geomagnetic storms are infrequent, but even though lessons were learned from the storm of 1989, our dependence on satellites, long-distance communications, and electrical power has only increased, so these solar storms remain a major hazard today.

Storm Dunlop is a Fellow of both the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Meteorological Society. The second edition of his Oxford Dictionary of Weather was published in 2008.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life science articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Green aurora photograph by Denis Buczynski. Red aurora photograph by Alex Cherney. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Space weather appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers