Oxford University Press's Blog, page 984

January 23, 2013

What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua?

Walmart now has stores in more than fifteen developing countries in Central and South America, Asia and Africa. A glimpse at the scale of operations: Nicaragua, with a population of approximately six million, currently has 78 Walmart retail outlets with more on the way. That’s one store for every 75,000 Nicaraguans; in the United States there’s a Walmart store for every 69,000 people. The growth has been rapid; in the last seven years, the corporation has more than doubled the number of stores in Nicaragua (see accompanying graphs — Figure 1 from the paper).

When a supermarket chain like Walmart moves into a developing country it requires a steady supply of fresh fruits and vegetables largely sourced domestically. In developing countries where the majority of the poor rely on agriculture for their livelihood, this means that poor farmers are increasingly selling produce to and contracting directly with large corporations. In precisely this way, Walmart has begun to transform the domestic agricultural markets in Nicaragua over the past decade. This profound change has been met with both excitement and trepidation by governments and development organizations because the likely effects on poverty and inequality are not known, in particular:

What existing assets or experience are required for a farmer to sell their produce to supermarkets?

Do small farmers who sell their produce to supermarkets benefit from the relationship?

What is the role of NGOs in facilitating small farmer relationships with supermarkets?

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Supermarkets require that farmers meet standards related to production, post-harvest processing, and delivery; for example, the use of specific pesticides and fertilizers and the cleaning and packaging of vegetables. Moreover, supermarkets generally require farmers to guarantee production year round, which requires planning (sometimes across multiple farmers), irrigation and capital. These requirements can present significant challenges to small farmers with little capital and it is thought that such challenges could strongly effect which farmers sell produce to supermarkets.

Generally, researchers have studied the inclusion of farmers in supply chains by measuring the income, assets and welfare of a group of farmers selling a crop to supermarkets (“suppliers”) with a similar group of farmers selling the same crop in traditional markets (“non-suppliers”). This research has provided important insights but has struggled with two persistent challenges.

First, because most existing studies rely on surveys of farmers living in the same area, we do not know how important farmer experience or assets such as farm machinery or irrigation, are for inclusion in supply chains in comparison to other farmer characteristics like community access to water or proximity to good roads.

Second, without measurements on supplier and non-supplier farmers over time it is difficult for a researcher to isolate the effect being a supplier has on the farmer. For example, if Walmart excels at choosing higher-ability farmers as suppliers, a study that just compared supplier and non-supplier incomes would overestimate the supermarket effect because Walmart’s high-ability farmers would earn more income even if they had not contracted with the supermarket.

With these two challenges in mind, I implemented a research project in Nicaragua in which I first identified all small farmers who had had a steady supply relationship with supermarkets for at least one year since 2000 (see accompanying graphs — Figure 2 from the paper). I also revisited 400 farmers not supplying supermarkets but living in areas where supermarkets were buying produce. My team and I surveyed farmers about their experiences over the past eight years: the markets where they had sold, the farming, land, and household assets they had owned. Since my study included farmers selling a variety of crops to supermarkets and measured how their assets, and supermarket relationships, changed in time, I was able to more rigorously address how these markets affected small farmers. The project was part of a collaboration between researchers Michigan State University, Cornell University, and the Nitlapan Institute in Managua.

Results

Farmer participation

Farmers located close to the primary road network and Nicaragua’s capital, Managua, where the major sorting and packing facility is located, and with conditions that allow them to farm year round were much more likely to be suppliers. Remarkably, this effect was much stronger than other farmer characteristics such as existing farm capital or experience.

Farmer welfare

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

Suppliers do benefit from selling their produce to supermarkets. The assets of farmers that sold to supermarkets for at least one year between 2000 and 2008 were 16% higher than for farmers that did not sell to supermarkets.

One way to think of income is as a flow of financial resources based, in part, on a farmer’s assets. By statistically relating a change in assets to a change in income I find that a 16% increase in assets corresponds to an average increase in annual household income of about $200 — or 15% of the average 2007 income for the farmers I studied.

Our previous work discovered that supermarkets don’t pay farmers a higher mean price than traditional markets but they do offer a more stable price. This analysis suggests a reason that household assets – and thus income — increase among farmers who sell to supermarkets; shielded from price fluctuations in the traditional markets by the supermarket contract, farmers invest in agriculture, in some cases moving to year-round cultivation. Farmers finance these investments through higher and more stable incomes and new credit sources. Income increases are attributable not to higher average prices but likely to increased production quantities.

NGOs

NGOs have played an important role in small farmer access to supermarket supply chains all over the world. In Nicaragua, a USAID program funded NGOs to help small farmers sell to supermarkets. These NGOs established farmers’ cooperatives and provided technical assistance, contract negotiation, and financing. Do NGOs change farmer selection or outcomes? Do they choose farmers with less wealth or experience? Or do farmers working with NGOs benefit in a special way from supermarkets because of the services NGOs provide?

We find, on average, that NGO-assisted farmers start with similar productive assets and land as those who sell to supermarkets without NGO assistance. Nor do we find a special effect on the assets of NGO-assisted farmers. However, we do find that NGOs play a critical role in keeping farmers with little previous experience in vegetable production in the supply chain. Low-experience farmers who are not assisted by NGOs are more likely to drop out of the supply chain than those assisted by NGOs.

Conclusions

These findings offer grounds for optimism and also a measure of caution with respect to the effects of supermarkets operating in developing countries. Supermarket contracts improve farmer welfare, and the improvements are detectable in farmers’ assets. However, since being close to roads and having the ability to farm year round is so critical to inclusion in the supply chain, not all farmers will be afforded these opportunities. Moreover, because these trends are still nascent in Nicaragua and in many other parts of the developing world, it remains to be seen what the broader effects will be for the agricultural sector and development. For example, as NGOs invest in preparing more small farmers to supply supermarkets, the gains to farmers from joining supply chains may be lost to increased competition. Our results in Nicaragua suggest that, given the small number of supplier farmers, changes in rural poverty related to supermarket expansion will be modest, but how will these supply chains, and the benefits they represent for farmers, change over time? I am currently a part of a team studying Walmart supply chains in China, which will interrogate these questions on a much larger scale in the context of a global and rapidly expanding economy.

Hope Michelson is a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia University’s Earth Institute in the Tropical Agriculture and Rural Environment program. She completed her doctoral research in the Economics of Development in 2010 at Cornell University’s Department of Applied Economics. She is the author of “Small Farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare Effects of Supermarkets Operating in Nicaragua” in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The American Journal of Agricultural Economics provides a forum for creative and scholarly work on the economics of agriculture and food, natural resources and the environment, and rural and community development throughout the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: All images property of Hope Michelson. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post What happens when Walmart comes to Nicaragua? appeared first on OUPblog.

Competition results: who’s your favourite philosopher?

To celebrate the publication of our second Philosophy Bites book, Philosophy Bites Back, authors Nigel Warburton and David Edmonds released a 39 minute podcast episode of a wide range of philosophers answering the question ‘Who’s Your Favourite Philosopher?’

Listen to Who’s Your Favourite Philosopher?

[See post to listen to audio]

Twitter Competition

We also asked you to let us know on Twitter who your favourite philosopher is and why. The competition is now closed and we received over 150 entries, which you can view on Storify. We can now reveal the winning entries, as chosen by Nigel Warburton and David Edmonds!

View the story “Philosophy Bites Back: The Winning Tweets” on Storify

David Edmonds is an award-winning documentary maker for the BBC World Service and a Research Associate at the Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at Oxford University. Nigel Warburton is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy at the Open University. They are co-authors of Philosophy Bites (OUP, 2010) and Philosophy Bites Back (OUP, 2012), which are based on their highly successful series of podcasts. You can also follow @philosophybites on Twitter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Competition results: who’s your favourite philosopher? appeared first on OUPblog.

Palliative care: knowing when not to act

One of the things that has always puzzled me is the number of palliative care services that have the word ‘pain’ in the title. Why do we concentrate so much on that one, admittedly unpleasant, symptom? Why ‘Pain and Palliative Care Services’ rather than, for example, ‘Vomiting and Palliative Care Service’ , ‘Dyspnoea and Palliative Care Service’, or even ‘Sadness, Anger, Existential Anguish and Palliative Care Service’?

That’s the problem with trying to describe palliative care. The whole point of palliative care is that it is holistic – a word that has acquired a certain flakiness, but which in reality simply refers to looking at the wholeness of a person, rather than focusing on only one domain (such as physical symptoms), or even one specific symptom (such as pain). But the purpose of a definition, by definition, is to set limits around a concept. There is a sense in which defining something as holistic is a contradiction in terms. Yet that is what we have to do in palliative care, if we are to communicate some sense of the task of caring for children and adults with life-limiting conditions; a sense that encompasses both the idea that it is holistic and that it is specialist (there are some things you need to learn to do to do it well).

The clue to the nature of palliative care is in the name: ‘care’. It is a care whose aim is not cure. In the United Kingdom, we have recently seen the results of misunderstanding what palliative care is all about. As in most countries that are resource-rich (or, at least, would have considered themselves as such before the global recession), the United Kingdom sometimes struggles to avoid the temptation to over-intervene. Even where it is overwhelmingly unlikely that an intervention will help – such as when death is inevitable – we in resource-rich countries can’t help ourselves. Sometimes we have to do something even if we know it is more likely to damage a patient – considered holistically – than it is to help them. That is not because anyone is trying to be cruel, but simply because if you are a doctor faced with a very sick patient, it is hard not to intervene, even when the latter option would truly be the right thing to do.

So, if you want to improve the lives of people who are close to death, one really good way to do it is to offer doctors more support in doing less, and in doing it well. The Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient (LCP) was designed to do exactly that. Its sole purpose has been to protect dying patients from the pain and indignity of useless interventions around the end of their life. Sadly, holding back on those interventions that will harm people can sometimes look, at least to the untutored eye, very like deliberately killing them. Even some philosophers find it tricky to admit that killing someone is not at all the same thing as refusing to try to prevent their inevitable death. So perhaps it is not surprising to find that, in trying to see who were the baddies here, the Daily Mail crashed clumsily down on the wrong side, screaming that babies were being euthanised using the Liverpool Care Pathway. But it isn’t true.

The Liverpool Care Pathway hasn’t really found its way into children’s care, despite the Daily Mail‘s assertions. That’s because it was designed for adults, mainly with cancer, rather than for children and the much larger range of conditions that can cause their death. There’s nothing wrong with the concept. As in adults, the art and science of palliative care in children is to preserve wellbeing as far as possible, using all the tools at our disposal. To do that often means introducing some interventions – some medication, perhaps, or the opportunity to talk about fears, or the chance to decide where you or your child should die. But improving wellbeing can equally mean withholding interventions that would be likely to cause an overall damage to it. Good paediatric palliative care must mean knowing what procedures to leave out, as well as knowing which ones to introduce. Whatever some moral philosophers say, there is a big difference between actively hastening someone’s death, and not trying fruitlessly to prevent death when to do so would mean making life worse. And whatever the Daily Mail may confidently claim, putting a patient on the Liverpool Care Pathway is not the same as euthanasia. Care pathways are pointers to the best way to avoid careless and harmful over-intervention. Properly used, palliation and pathways do exactly what they say on the tin; they care.

Dr Richard Hain is Consultant and Lead Clinician at the Wales Managed Clinical Network in Paediatric Palliative Care Children’s Hospital, and Visiting Professor at the University of Glamorgan, and Honorary Senior Lecturer at Bangor University. He is co-editor of the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, Second Edition (OUP, 2012), with Ann Goldman and Stephen Liben.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Old and young hands photo by SilviaJansen via iStockPhoto.

The post Palliative care: knowing when not to act appeared first on OUPblog.

January 22, 2013

Celebrating Piltdown

Science works in mysterious ways. Sometimes that’s even truer in the study of the origins of the human race.

Piltdown is a small village south of London where the skull of a reputed ancient human ancestor turned up in some gravel diggings a century ago. The find was made by Charles Dawson, a lawyer and amateur archaeologist, with an unusual knack for major discoveries. Shortly thereafter a lower jaw that fit the skull turned up and, voilá — the missing link between the apes and man had been found in the British Isles.

The Manchester Guardian headlined “The earliest man? Remarkable discovery in Sussex. A skull millions of years old.” The find was widely regarded as the most important of its time. The discovery of Piltdown Man made Europe, and especially Great Britain, the home of the “first humans”. The find fit the expectations of the time and resolved certain racist and nationalist biases against evidence for human ancestry elsewhere. Early humans had large brains and originated in Europe.

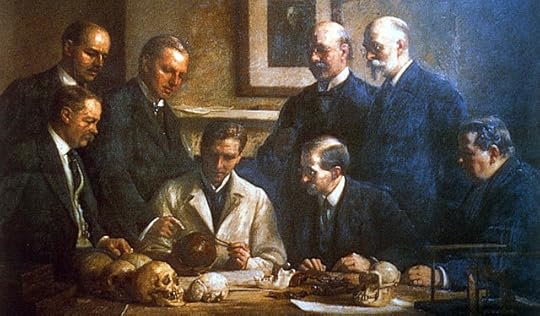

Piltdown Gang by John Cooke (1915). Back row: (left to right) F. O. Barlow, G. Elliot Smith, Charles Dawson, Arthur Smith Woodward. Front row: A. S. Underwood, Arthur Keith, W. P. Pycraft, and Sir Ray Lankester.

For 40 years this Piltdown Man was generally accepted as an important ancestor of the human race. Various authorities raised doubt and critiqued the evidence, but Piltdown kept its place in our early lineage until a curator at the British Museum, Kenneth Oakley, took a closer look. Oakley and several other scientists assembled incontrovertible evidence to the show that Piltdown was a forgery. The chemistry of the jaw and skull were different and could not have come from the same individual. The teeth of the lower jaw had been filed down to make them fit with the skull. The skull was human but the jaw came from an ape. The bones had been stained to enhance the appearance of antiquity. In 1953, Time magazine published this evidence gathered by Oakley and others. Piltdown was stricken from the record and placed in ignominy, a testimony to the gullibility of those scientists who see what they want to see.

Hoax, fraud, crime? Perhaps the designation is not so important, but the identity of the perpetrator appears to be. More than 100 books and articles have been written over the years, trying to solve the mystery of who forged Piltdown. Various individuals have been implicated, but the pointing finger of justice always returns to Charles Dawson. Dawson’s knack for finding strange and unusual things was more than just luck. His sense of intuition was fortified by a home workshop for constructing or modifying these finds before he put them in the ground. A recent book by Miles Russell, The Piltdown Man Hoax: Case Closed, documents Dawson’s numerous other archaeological and paleontological “discoveries” that have been revealed as forgeries. As Russell noted, the case is closed. That fact, however, is not keeping British scientists from throwing a good bit of money and energy into the whodunit, using the latest scientific technology to try to unmask the culprit.

So, 100 years of Piltdown. Not exactly a cause for celebration — or is it? Science does work in mysterious ways. Although Piltdown misled the pursuit of our early human ancestors for decades, much good has come from the confusion. Greater care is exercised in the acceptance of evidence for early human ancestors. Scientific methods have moved to the forefront in the investigation of ancient human remains. The field of paleoanthropology — the study of early human behavior and evolution — has emerged wiser and stronger. The earliest human ancestors are now known to have come from Africa and begun to appear more than six million years ago. Evolution, after all, is about learning from our mistakes.

T. Douglas Price is Weinstein Professor of European Archaeology Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His books include Europe before Rome: A Site-by-Site Tour of the Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages; Principles of Archaeology; Europe’s First Farmers; and the leading introductory textbook in the discipline, Images of the Past.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Piltdown appeared first on OUPblog.

Choices and rights, children and murder

Demonstration protesting anti-abortion candidate Ellen McCormack at the Democratic National Convention, New York City. Photo by Warren K. Leffler, 14 July 1976. Source: Library of Congress.

“Abortion is a Personal Decision, Not a Legal Debate!”“My Body, My Choice!”

“Abortion Rights, Social Justice, Reproductive Freedom!”

Such are today’s arguments for upholding Roe v. Wade, whose fortieth birthday many of us are celebrating.

Others are mourning.

“It’s a child, not a choice!”

“Abortion kills children!”

“Stop killing babies!”

How did we arrive at this stunningly polarized place in our discussion — our national shouting match — over women’s reproductive rights?

Certainly it wasn’t always this way. Indeed, consensus and moderation on the issue of abortion has been the rule until recently.

Even if we go back to biblical times, the brutal and otherwise misogynist law of the Old Testament made no mention of abortion, despite popular use of herbal abortifacients at the time. Moreover, it did not treat a person who caused a miscarriage as a murderer. Fast-forward several thousand years to North American indigenous societies where women regularly aborted unwanted pregnancies. Even Christian Europeans who settled in their midst did not prohibit abortion, especially before “quickening,” or the appearance of fetal movement. Support for restrictions on abortion emerged only in the 1800s, a time when physicians seeking to gain professional status sought control over the procedure. Not until the twentieth century did legislation forbidding all abortions begin to blanket the land.

What happened during those decades to women with unwanted pregnancies is well documented. For a middle-class woman, a nine-month “vacation” with distant relatives, a quietly performed abortion by a reputable physician, or, for those without adequate support, a “back-alley” job; for a working-class woman, nine months at a home for unwed mothers, a visit to a back-alley butcher, or maybe another mouth to feed. Women made do, sometimes by giving their lives, one way or another.

But not until the 1950s did serious challenges to laws against abortion emerge. They began to gain a constitutional foothold in the 1960s, when the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) persuaded the US Supreme Court to declare state laws that prohibited contraceptives in violation of a newly articulated right to privacy. By the 1970s, the notion of a right to privacy actually cut many ways, but on January 23, 1973, it cut straight through state criminal laws against abortion. In Roe, the Supreme Court adopted the ACLU’s claim that the right to privacy must “encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” But the Court also permitted intrusion on that privacy according to a trimester timetable that linked a woman’s rights to the stage of her pregnancy and a physician’s advice; as the pregnancy progressed, the Court allowed the state’s interest in preserving the woman’s health or the life of the fetus to take over.

Roe actually returned the country to an abortion law regime not so terribly different from the one that had reigned for centuries if not millennia before the nineteenth century. The first trimester of a pregnancy, or the months before “quickening,” remained largely under the woman’s control, though not completely, given the new role of the medical profession. The other innovation was that women’s control now derived from a constitutional right to privacy — a right made meaningful only by the availability and affordability of physicians willing to perform abortions.

With these exceptions, the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe did little more than return us to an older status quo. So why has it left us screaming at each other over choices and children, rights and murder?

There are many answers to this question, but a major one involves partisan politics.

On the eve of Roe, to be a Catholic was practically tantamount to being a Democrat. Moreover, feminists were as plentiful in the Republican Party as they were in the Democratic Party. Not so today, on the eve of Roe’s fortieth birthday. Why?

As the Catholic Church cemented its position against abortion and feminists embraced abortion rights as central to a women’s rights agenda, politicians saw an opportunity to poach on their opponent’s constituency and activists saw an opportunity to hitch their fortunes to one of the two major parties. In the 1970s, Paul Weyrich, the conservative activist who coined the phrase “moral majority,” urged Republicans to adopt a pro-life platform in order to woo Catholic Democrats. More recently, the 2012 election showed us Republican candidates who would prohibit all abortions — at all stages of a pregnancy and even in cases of rape and incest — and a proudly, loudly pro-choice Democratic Party.

In the past forty years, abortion has played a major role in realigning our major political parties, associating one with conservative Christianity and the other with women’s rights — a phenomenon that has contributed to the emergence of a twenty-point gender gap, the largest in US history. Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that we are screaming at each other.

Leigh Ann Wheeler is Associate Professor of History at Binghamton University. She is co-editor of the Journal of Women’s History and the author of How Sex Became a Civil Liberty and Against Obscenity: Reform and the Politics of Womanhood in America, 1873-1935.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Choices and rights, children and murder appeared first on OUPblog.

Do you know your references and allusions?

Are you an Athena when it comes to literary allusions, or are they your kryptonite? Either way, the Oxford Dictionary of Reference and Allusion can be your Henry Higgins, providing fascinating information on the literary and pop culture references that make reading and entertainment so rich. Take this quiz, Zorro, and leave your calling card.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Andrew Delahunty and Sheila Dignen are freelance lexicographers who have extensive experience compiling dictionaries. From classical mythology to modern movies and TV shows, the revised and updated Oxford Dictionary of Reference and Allusion, third edition explains the meanings of more than 2,000 allusions in use in modern English, from Abaddon to Zorro, Tartarus to Tarzan, and Rambo to Rubens.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only dictionary articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Do you know your references and allusions? appeared first on OUPblog.

Are the political ideals of liberty and equality compatible?

Are the political ideals of liberty and equality compatible? In this video, OUP author James P. Sterba of University of Notre Dame, joins Jan Narveson of University of Waterloo, to debate the practical requirements of a political ideal of liberty. Not only Narveson but the entire audience at the libertarian Cato Institute where this debate takes place is, in Sterba’s words, ”hostile” to his argument that the ideal of liberty leads to (substantial) equality. Sterba goes on to further develop that argument in From Rationality to Equality.

Click here to view the embedded video.

James P. Sterba is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame. His latest work, From Rationality to Equality, publishes in February 2013. His previous publications include Three Challenges to Ethics (OUP, 2001), The Triumph of Practice over Theory in Ethics (OUP, 2005) and Does Feminism Discriminate Against Men? A Debate, with Warren Farrell (OUP, 2007). He is past president of the American Philosophical Association (Central Division).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Are the political ideals of liberty and equality compatible? appeared first on OUPblog.

Plagiarized or original: A playlist for the contested music of Ira B. Arnstein

From the 1920s to the 1950s, Ira B. Arnstein was the unrivaled king of music copyright litigants. He spent the better part of those 30 years trying to prove that many of the biggest hits of the Golden Age of American Popular Song were plagiarized from his turn-of-the-century parlor piano pieces and Yiddish songs. “I suppose we have to take the bad with the good in our system which gives everyone their day in court,” Irving Berlin once said, but “Arnstein is stretching his day into a lifetime.”

Arnstein never won a case, but he left an enduring imprint on copyright law merely by getting his days in court and establishing precedents that later led to copyright infringement judgments against such notables as George Harrison and Michael Bolton. Though his claims often strained judicial credulity, Arnstein had a gift for posing conundrums that engaged some of the finest legal minds of his era, forcing them to refine and sharpen their doctrines.

Over the years, Arnstein laid claim to more than a hundred standards of the Great American Songbook. This playlist of 15 songs — from Irving Berlin’s “A Russian Lullaby” of 1927 to Cole Porter’s “I Love Paris” of 1952 — is representative, and we have selected recordings that illustrate performance styles from the 20s to today. “No one,” as one lawyer wrote and you will agree, “can accuse Arnstein of courting feeble opposition.”

Gary A. Rosen is the author of Unfair to Genius: The Strange and Litigious Career of Ira B. Arnstein. He has practiced intellectual property law for more than 25 years. Before entering private practice, he served as a law clerk to federal appellate judge and award-winning legal historian A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Plagiarized or original: A playlist for the contested music of Ira B. Arnstein appeared first on OUPblog.

January 21, 2013

Checking in on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream, with data

Martin Luther King, Jr. was the legendary civil rights leader whose strong calls to end racial segregation and discrimination were central to many of the victories of the Civil Rights movement. Every January, the United States celebrates Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to honor the activist who made so many strides towards equality.

Let’s take a look at the demographics of the legendary man’s hometown then and now to see how it has (and has not) changed. King was born in 1929, so we’ll examine Census data from 1930, 1940, and the latest Census and American Community Survey data.

His boyhood home is now a historic site, situated at 450 Auburn Avenue Northeast, in Fulton County (part of Atlanta). In 1930, Fulton County had a population of 318,587 residents. A little over two thirds of the population was white (68.1 percent) and almost one third of the population was African American (31.9 percent). Today, the 920,581-member population split is nearly even at 44.5 percent white and 44.1 percent African American, according to 2010 Census data. Fulton’s population is more African American than the United States as a whole (12.6 percent), but not as as much as Atlanta (54.0 percent).

A closer look at 1940s Census data of the Atlanta area offers more detail about where the black and white populations lived. The following map shows the distribution of the black population in the Atlanta of King’s youth. Plainly, African Americans lived together, largely apart from whites.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 1940 (click map to explore)

For comparison, the following map shows where the black population lives today. Now the black population has expanded in the metro area, but still seems to be quite segregated.

African American Population in Fulton County, GA, and Surroundings, 2010 (click map to explore)

Reflecting on a century after the end of slavery, King said in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

The quest for equal rights and freedoms made up part of a larger vision. In 1967, he spoke of aspiring for full equality at a speech at the Victory Baptist Church in Los Angeles:

Our struggle in the first phase was a struggle for decency. Now we are in the phase where there is a struggle for genuine equality. This is much more difficult. We aren’t merely struggling to integrate the lunch counter now. We’re struggling to get some money to be able to buy a hamburger or a steak when we get to the counter…

He went on to say that this would require a commitment of not only political initiative but also money: “It didn’t cost the nation one penny to integrate lunch counters. It didn’t cost the nation one penny to guarantee the right to vote. The problems that we are facing today will cost the nation billions of dollars.”

In 1968, King and other activists launched the Poor People’s Campaign, advocating for economic justice to address these imbalances in opportunity and resources. A few months later, he was assassinated.

We can look at different socioeconomic indicators to measure the country’s progress towards equality. According to 1940 Census data, more than a third (36.5 percent) of housing units in Fulton County where whites lived were owner occupied, compared to less than a seventh (14.0 percent) of the housing units where African Americans lived.

Today, home ownership increased for both groups, but the gap remains. Two thirds (66.6 percent) of white households are owner-occupied, compared to two fifths (41.7 percent) of all black households.

Home Ownership Comparison in Fulton, GA, by Race

Let’s examine other measures of equality to see examples of additional gaps.

The unemployment rate is nearly twice as high among African Americans (17.9 percent) compared to among whites nationwide (9.5 percent). That gap is even more pronounced in Fulton County, where the unemployment rate for whites is 7.7 percent, while the unemployment rate for African Americans is 20.4 percent.

The percent of those living below poverty is also higher in the black community (27.2 percent) than in the white community (12.5 percent). While both groups are better off in Fulton County than the rest of the US, the poverty rate gap is even larger (8.2 percent among whites and 26.6 percent among African Americans in Fulton).

Similarly, while both groups are better educated in Fulton County compared to the rest of the US, nearly two thirds (62.4 percent) of white adults in the county have BA degrees or more, while just one quarter (25.3 percent) of the black population have the same level of education. The college attainment gap is 11.6 percentage points nationwide, but 37.1 percentage points in Fulton County.

While much progress towards freedom and equality has been made since King’s time, chronic gaps persist, even in his own backyard. The data show that 50 years after the “I Have a Dream Speech,” equal opportunity and socioeconomic status continue to lag behind equal rights.

Sydney Beveridge is the Media and Content Editor for Social Explorer, where she works on the blog, curriculum materials, how-to-videos, social media outreach, presentations and strategic planning. She is a graduate of Swarthmore College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. A version of this article originally appeared on the Social Explorer blog. You can use Social Explorer’s mapping and reporting tools to investigate dreams, freedoms, and equality further.

Social Explorer is an online research tool designed to provide quick and easy access to current and historical census data and demographic information. The easy-to-use web interface lets users create maps and reports to better illustrate, analyze and understand demography and social change. From research libraries to classrooms to the front page of the New York Times, Social Explorer is helping people engage with society and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Checking in on Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream, with data appeared first on OUPblog.

Lessons of Casablanca

Seventy years ago this month, Americans came to know Casablanca as more than a steamy city on the northwest coast of Africa. On 23 January 1943, the film Casablanca, starring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman, a tale of doomed love and taking the moral high ground, was released to packed movie houses. The next day, a Sunday, President Franklin Roosevelt ended two weeks of secret World War II meetings in Casablanca with Prime Minister Winston Churchill by announcing at a noon press conference, in a sunlit villa garden fragrant with mimosa and begonia, that “peace can come to the world,” only through the “unconditional surrender by Germany, Italy and Japan.”

The Academy Award-winning movie, of course, became a classic.

Title screen of Casablanca, the Academy-Award winning classic directed by Michael Curtiz and starring Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Paul Henreid. Image in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Similarly, Roosevelt’s supremely confident proclamation reverberated throughout the world and shortly entered the history books. Choosing just a few words, the president for the first time sought to firmly establish Allied war aims and determine the framework of the peace.

But both the emotional power of the film and the president’s lofty words blurred if not obscured some inconvenient facts. American audiences must have been persuaded that their government, like Bogart’s Rick, would do the right thing by turning its back on the Nazi collaborators (the French puppet government, the Vichy regime) and casting its lot to fight alongside Charles de Gaulle’s Free French. In fact, the Roosevelt administration did not act to cut its ties with Vichy, continued to rely on Nazi sympathizers to run the Moroccan government, and did not officially recognize de Gaulle until October 1944. Like the political and military realities confronting the Obama administration today in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria and Iran, the situation on the ground in North Africa in 1943 was murky, complicated and ambiguous. It did not lend itself to the high-minded moral clarity that Hollywood screenwriters enjoy.

So too the policy of unconditional surrender announced by the US president at Casablanca, and endorsed by the British prime minister, masked some stark realities. Unless and until the Soviet Union decided once and for all to reject German peace-feelers and its Red Army had achieved sufficient size and strength to break the back of Germany’s military machine, “unconditional surrender” could be nothing more than a hollow slogan. Though the president’s confident rhetoric was ostensibly aimed at lifting the morale of the populations of the United States and Great Britain, it was in fact directed at the man who was conspicuously absent from the Casablanca conference—Joseph Stalin. Roosevelt was aware that many would argue that the unconditional surrender policy would prolong the war by encouraging the Nazis to fight to the last man and woman, but he believed that this danger was outweighed by the need to allay Soviet suspicions that the Americans and British would conspire to negotiate a separate armistice with Germany. Roosevelt saw his policy as another way to convince Stalin of his goodwill, a political and psychological substitute for a second front—a phrase that would keep the Soviets in the war, killing German soldiers by the bushel.

President Roosevelt, with Prime Minister Winston Churchill at his side, reading the “unconditional surrender” announcement to the assembled war correspondents. Casablanca, French Morocco, Jan 1943. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

The policy announced by Roosevelt at Casablanca not only failed to acknowledge the essential role of the Soviets, it also did not have the impact on surrender and peace that he intended. Italy would soon surrender under “conditional” terms. Japan would eventually surrender on condition that her Emperor would be retained. And FDR’s dream that he would turn the page on balance-of-power diplomacy in central Europe and broker the postwar peace would be shattered by the man who could not attend the Casablanca conference in January 1943 because he was busy directing the crucial struggle at Stalingrad.

In the years since Casablanca, experience has shown that presidents would do well to emulate Roosevelt by defining war goals and outlining a framework for peace before engaging the enemy (or at least at an early stage of the conflict). Indeed, the failures of presidents Truman, Johnson, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush to do so in Korea, Vietnam, Panama, Iraq, and Afghanistan seriously soiled their legacies.

Still, the lessons of Casablanca run much deeper and are far more nuanced than the articulation of war aims and peace terms. Casablanca—the movie and the conference—teaches us that human conflict, particularly armed conflict, usually does not end on predictable terms and in conformance with unilateral decrees. Often family, clan, or tribal affiliations trump national loyalties making it difficult if not impossible to distinguish between friends and enemies, neutrals and belligerents. Religious and cultural differences befuddle American peacekeepers. These problems test the mettle of the Obama administration today in places like Benghazi, Waziristan, Damascus, and Teheran.

In Casablanca, Rick was led to believe that he had come to that city because of the healthful waters. Told by Captain Renault that he was in the desert, Rick responded, “I was misinformed.” When it comes to waging wars and structuring peace, US presidents and policymakers should humbly revisit the lessons of Casablanca.

David L. Roll is a partner at Steptoe & Johnson, LLP and founder/director of the Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation, a public interest organization that provides pro bono legal services to social entrepreneurs around the world. His latest book is The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Lessons of Casablanca appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers