Oxford University Press's Blog, page 977

February 14, 2013

Comfort food

This Valentine’s Day-themed tech post was supposed to be just that—a way to show that all that sexy metadata powering the Oxford Index’s sleek exterior has a sweet, romantic side, just like the rest of the population at this time of year. I’d bounce readers from a description of romantic comedies to Romeo and Juliet to the three-act opera Elegy for Young Lovers, and then change the Index’s featured homepage title to something on the art of love to complete the heart shaped, red-ribboned picture.

I didn’t do any of these things. I got distracted. As it turns out, searching the word “chocolate” (“It is not addictive like nicotine but some people, ‘chocoholics’, experience periodic cravings”) reveals a whole smorgasbord of suggested links to delectable food summaries and from my first glimpse at the makings of a meringue, I was gone—making mental notes for recipes, stomach rumbling, eyes-glazing over. Mmm glaze.

In the end, my “research” was actually quite fitting to the season. Because, really, when it comes to Valentine’s Day in the 21st century, only a handful of things are reliable and certain—and almost all of them are made with sugar.

Best Mouthwatering Dessert Descriptions

Mousse

Meringue

Baklava

Profiterole

Tiramisù

Turkish delight

Wafer

Mille-feuille

Best Quote About Doughnuts…or Anything

“When Krispy Kremes are hot, they are to other doughnuts what angels are to people.”

– Humor writer Roy Blount Jr, New York Times Magazine

Best Etymology Entry

Snack

→ Snack was originally a verb, meaning ‘bite, snap’. It appears to have been borrowed, in the fourteenth century, from Middle Dutch snacken, which was probably onomatopoeic in origin, based on the sound of the snapping together of teeth… The modern verb snack, ‘eat a snack,’ mainly an American usage, is an early nineteenth-century creation.

Top 5 Favorite Random Food Facts

Attempts to can beer before 1930 were unsuccessful because a beer can has to withstand pressures of over eighty pounds per square inch.

Brownies are essentially the penicillin of the baking world.

Boston is the brains behind Marshmallow Fluff.

There is such a thing as the “Queen of Puddings” …and it sounds amazing:

→ Pudding made from custard and breadcrumbs, flavoured with lemon rind and vanilla, topped with jam or sliced fruit and meringue.

Cupcakes are known by some as “fairy cakes”.

Best Relevancy Jump

The overview page for “cake”….

→ Plain cakes are made by rubbing the fat and sugar into the flour, with no egg; sponge cakes by whipping with or without fat; rich cakes contain dried fruit.

….leads to a surprising related link: “Greek sacrifice”

→ Vegetable products, esp. savoury cakes, were occasionally ‘sacrificed’ (the same vocabulary is used as for animal sacrifice) in lieu of animals or, much more commonly, in addition to them. But animal sacrifice was the standard type.

The Entry I Wish I Hadn’t Found:

→ Flaky crescent-shaped rolls traditionally served hot for breakfast, made from a yeast dough with a high butter content. A 50‐g croissant contains 10 g of fat of which 30% is saturated.

Best Food-Related Band Names

Martha And The Muffins

Milk and Cookies

My Friend The Chocolate Cake

Sam Apple Pie

Ice Cream Hands

Best Overall Summary of What Food Is

Food and Literature

→ Food is a form of communication that expresses the most deeply felt human experiences: love, fear, joy, anger, serenity, turmoil, passion, rage, pleasure, sorrow, happiness, and sadness.

Georgia Mierswa is a marketing assistant at Oxford University Press and reports to the Global Marketing Director for online products. She began working at OUP in September 2011.

The Oxford Index is a free search and discovery tool from Oxford University Press. It is designed to help you begin your research journey by providing a single, convenient search portal for trusted scholarship from Oxford and our partners, and then point you to the most relevant related materials — from journal articles to scholarly monographs. One search brings together top quality content and unlocks connections in a way not previously possible. Take a virtual tour of the Index to learn more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Croissants chauds sortis du four. Photo by Christophe Marcheux/Deelight, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Comfort food appeared first on OUPblog.

Valentine’s Day serenades

Love is in the air at Oxford University Press! As we celebrate Valentine’s Day, we’ve asked staff members from our offices in New York, Oxford, and Cary, NC, to share their favorite love songs. Read on for their selections, and be sure to tell us what your favorites are too. Happy Valentine’s Day!

Owen Keiter, Publicity

All-time is impossible, so…“Girlfriend” by Ty Segall is a feat of simplicity. Ty manages to stuff the headlong rush of a new, young, senseless love into about two breathless minutes. Nobody’s getting excited about the caveman-ish lyrics, which are almost incomprehensible anyway, but that’s not the point. The point is: when Ty hollers “I’ve got a girlfriend/She says she loves me,” you can tell it’s got him feeling like nothing can touch him.

Click here to view the embedded video.

For those having less pleasant Valentine’s Days: “Lipstick Vogue” by Elvis Costello. This Year’s Model is the Bible of those who are mistrustful of sex and love; “Lipstick Vogue” contains gems like “Maybe they told you were only one girl in a million/You say I’ve got no feelings; this is a good way to kill them.”

Lana Goldsmith, Publisher Services

My actual favorite love song right now is “Crazy Girl” by Eli Young Band. I love this song because I feel like I live it all the time. It’s easy to feel insecure or unappreciated, but this song shakes you by the shoulders and reminds you that you’re the greatest thing that ever happened to somebody.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Purdy, Director of Publicity

When you are single and in your 40s love has come and gone enough that I find it hard to narrow my choice down to just one favorite love song. I have three that make me wistful for another lover, and maudlin for love and lovers long lost:

Nina Simone’s “Do I Move You” is a bluesy jazz plea for recognition from some indifferent lover that is at times sultry, needful, demanding and lustful.

Another classic by Ms. Simone, “Turn Me On,” is a simile-saturated reminiscence of a lover gone too long and the heightened anticipation of his/her return.

Finally, there is Miss Etta James’s version of “Deep in the Night.” Etta’s mournful moan reminds me how love can come to plagues one’s every thought and action:

Read a book and I think about you

Put it down and I think about you

I make some coffee and I think about you

Wash up the cup and I think about you

Wind the clock I think about you

Turn on the light and I think about you

Then I punch the pillow and think about you

Anwen Greenaway, Promotion Manager, Sheet Music

“True Love” by Cole Porter is one of the most memorable songs in the 1956 film High Society, starring Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly, and Frank Sinatra. When I was a child my Dad had an old vinyl record of the film soundtrack. I remember being mesmerized by the film stills on the LP cover and listening to the record over and over at Christmas. It’s the soundtrack of all my childhood Christmases, a beautiful song, and unashamedly sentimental — what’s not to love about that?!

Click here to view the embedded video.

Flora Death, Editorial Admin Assistant, Sheet Music

“So In love” by Cole Porter, from Kiss Me Kate, because it’s gloriously melodramatic and haunting, and has wonderful lyrics like all Cole Porter’s music.

Emma Shires, Editorial Assistant, Sheet Music

Marvin Gaye’s “How Sweet it is to be Loved by You” is so fun and upbeat. I love putting it on when I’m cooking, really turning up the volume, and dancing round the kitchen like a mad thing.

Ruth Fielder, Sales Administrator, Sheet Music

Biffy Clyro’s “Mountains” is my all-time favorite love song because it represents the ugly and beautiful sides to being in love, and therefore, for me, this song paints a more realistic picture: This being that most of the time love is a selfish act, but on occasion love itself as a thing of togetherness and intimacy; that ultimately nothing can tear you apart.

Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Publicity

“Laid” is a very sly love song by the British band James. The best line is the women’s clothes/gender roles couplet (if not the kitchen knives and skeeeeeewers) rather than the famous opening verse unfit for the OUPBlog. I sang this song, including the falsetto ending, COUNTLESS times with my friend Clara, who is now the history editor at NYU Press, when we were both assistants, as there wasn’t much to do in Princeton except go to the Ivy on Thursdays for karaoke and $1 beers. I hadn’t heard the song in ages until this past December at The Archive, a bar around the corner from our offices on Madison Avenue, and the television jukebox was playing, improbably, “The Best of James.” My friend and colleague Owen, the bassist for the great new band Journalism, said “The Best of James?? What the hell is James?” Probably for the best…

Matt Dorville, Online Editor, Reference

“The Book of Love” by The Magnetic Fields is a favorite of mine that is very apropos for a publishing house blog and one that I find myself singing all too often. It is from 69 Love Songs, an ambitious, and somewhat cheeky, look at love from The Magnetic Fields. If you haven’t listened to the album, I highly recommend it. It contains songs that are bittersweet, tender, pithy and catchy as hell. They’re not all winners, but the ones that are will make you smile all day.

Alana Podolsky, Publicity

“Tere Bina” composed by A. R. Rahman, lyrics by Gulzar is my favorite. Meaning “Without You”, “Tere Bina” is the great A.R. Rahman’s composition for the Hindi film Guru (2007) starring Abhishek Bachchan and Aishwarya Rai, Bollywood’s Brangelina. Rahman’s score derives from Sufi devotional music and is paired with Gulzar’s simple lyrics, creating a song that will resonate with any heartsick romantic no matter your language background. The cherry on top: the film’s dance sequence.

Kimberly Taft, Journals

My favorite love song is “At Last” by Etta James. I think it’s great because of her powerful vocals and the accompanying instruments. It’s truly a classic and I’m sure will be around forever.

Jessica Barbour, Grove Music/Oxford Music Online

“I’m Your Moon” was written by Jonathan Coulton in reaction to Pluto’s demotion from planet to dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union. Coulton, stating that Pluto clearly must have found this “very upsetting,” wrote a love song to the slighted celestial body from the point of view of Charon, one of Pluto’s moons. (You can watch another live video in which Coulton tells the whole backstory here.) Pluto is only twice as big as Charon, and they orbit a point between each other instead of Charon circling Pluto the way our moon orbits around the Earth. And they’re always facing each other as they orbit, like two people doing this. Coulton says on his blog that he was just thinking about Pluto when he wrote it. But the way Charon sings about how the rest of the world doesn’t really understand them, encourages Pluto to stay true to itself, and promises that they’ll always have each other no matter what—what else can you ask for in the perfect love song?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Anna-Lise Santella, Grove Music and Oxford Reference

Back when we were dating, my husband and I used to hang out at Cafe Toulouse in Chicago where the great jazz violinist Johnny Frigo used to play with Joe Vito on piano. We loved the way he played “A Fine Romance.” If we had to pick something to be “our song,” that would be it. When it came time to picking a song for the first dance at our wedding, that was the first thing that came to mind. Then we looked at the lyrics — which are the opposite of a love song:

A fine romance, with no kisses

A fine romance, my friend, this is

We should be like a couple of hot tomatoes, But you’re as cold as yesterday’s mashed potatoes….

Not a song with which to celebrate the start of a marriage. The song was written by Jerome Kern for the movie Swing Time, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Fortunately, the movie also includes one of the great love songs of all time, “The Way You Look Tonight.” We picked that instead. And we asked Johnny Frigo to play at our wedding. It was perfect. It’s one of the great romantic songs:

Some day, when I’m awfully low,

When the world is cold,

I will feel a glow just thinking of you And the way you look tonight….

A month after we got married, I ran into Johnny playing a Columbus Day gig in Daley Plaza in Chicago. I reminded him who I was and told him how much we’d enjoyed his playing at our wedding. “Great night, great night,” he said. “And you weren’t so bad yourself.”

Click here to view the embedded video.

Your Oxford-Approved Playlist:

Alyssa Bender joined Oxford University Press in July 2011 and works as a marketing associate in the Ac/Trade and Bibles divisions. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: scanned from period card from ca. 1910 with no notice of copyright via Wikimedia Commons

The post Valentine’s Day serenades appeared first on OUPblog.

A Valentine’s Day Quiz

It’s that time of the year again where the greeting cards, roses and chocolates fly off the shelves. What is it about Valentine’s Day that inspires us (and many of the great literary authors) to partake in all kinds of romantic gestures?

This month Oxford Reference, the American National Biography Online, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Who’s Who have joined together to create a quiz to see how knowledgeable you are in Valentine traditions.

Do you know who grows some of the most fragrant roses or hand-dips the sweetest treats? Find out with our quiz.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Answers to all these questions can be found using Oxford Reference, the Oxford DNB, Who’s Who, and the American National Biography Online. Both Oxford Reference and the Oxford DNB are freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the resources, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A Valentine’s Day Quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

Why the corporation is failing us, and how to restore it

The corporation is the most important institution in the world – an institution that clothes, feeds and houses us; employs us and invests our savings; and is the source of economic prosperity and the growth of nations around the world. At the same time, it has been the cause of terrible poverty, deprivation and environmental degradation, and these problems are set to increase in the future.

Over the last few years alone we have endured:

The accounting scandals in Enron and WorldCom

The Libor scandals

The underpayments of corporation tax

The misselling of mortgages, payment protection insurance, and derivatives

The financial crisis

The environmental disasters in the Gulf of Mexico and Fukushima

Each of these is thought to have their own cause and to require their particular solution. This is fundamentally wrong: the problems are not specific and the solutions are not individual. There is a generic problem that requires a common solution. The problem is the corporation and the solution is to fix it and not everything around it.

Fixing the corporation involves addressing its failures of ownership, values, governance, regulation and taxation. This requires:

Corporations taking responsibility for their actions and consequences, and having long-term committed shareholders;

Corporations having clearly defined values and principles, and truly independent boards of directors responsible for their implementation;

Tougher enforcement of public laws regarding bribery, corruption, environmental damage, fraud, insider dealing and market abuse;

More stringent protection of our financial systems and ecosystems;

Less intrusive regulation elsewhere and greater use of the corporate tax system to align interests of corporations with society at large.

Implementing these changes involves a reform of business education and a redefinition of the roles and responsibilities as well as rights and rewards of executives and investors.

This is not so much a reinvention as a rebirth of the corporation. Historically it was established by royal charter with a defined public purpose to undertake voyages of discovery and promote trade. The family firms that succeeded it were frequently established by founders with strong ethical principles and visions. Two corporations that illustrate that are Lehman Brothers and Barclays Bank, not today’s versions but those of the 19th and 17th centuries respectively. Mayer Lehman, the founder of Lehman Brothers, took his children every Sunday to the Mount Sinai hospital to see the plight of the less fortunate members of New York society. John Freame, the founder of Barclays Bank, wrote Scripture Instruction, a principle text used by the Quakers for more than a century. Over time those strong values have contracted into a single one of maximizing the short term earnings of shareholders.

That is not universally the case – some of the world’s most successful corporations and best performing economies have very different purposes and values. Bertlesmann one of the world’s largest media companies, Robert Bosch the automotive company, Carlsberg the brewing company, and Tata the conglomerate owner of Jaguar Land Rover are all structured as industrial foundations with boards that are responsible for the values and principles of their organizations. The Nordic and Scandinavian countries, which are currently being upheld as models for the rest of the world, emphasize a broader set of corporate principles encompassing a wider set of stakeholders than their shareholders.

This bears not only on the positive aspects of what corporations could do but also on the normative ones of what they should do. While notions of morality are well developed in relation to individuals, they are not in respect of corporations. Indeed, the idea of a moral corporation would generally be regarded as an oxymoron. It is not. What gives it substance is the ability of the corporation to establish levels of commitment to which we as individuals can only aspire. What makes it credible is the coincidence between the normative goals of doing good and the positive ones of making goods because ultimately the moral corporation is a commercially successful one and the competitiveness of nations depends on the moral fibre of its corporations.

Restoring trust in corporations is one of the most important policy issues of the 21st century. Without it economic policies will fail, environmental degradation will intensify and financial systems will collapse. With it, we can achieve levels of economic prosperity and well-being that far exceed what we have experienced to date.

Video: Colin Mayer on fixing the broken trust in corporations

Click here to view the embedded video.

See also: Why are we facing a crisis of trust in corporations?

And: What needs to be done to restore trust in corporations?

Colin Mayer is the author of Firm Commitment: Why the corporation is failing us and how to restore trust in it (OUP, 2013). He is the Peter Moores Professor of Management Studies at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, an Honorary Fellow of Oriel and St Anne’s Colleges, Oxford, and a Professorial Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. He is a member of the UK Competition Appeal Tribunal and the UK Government Natural Capital Committee, and a Fellow of the European Corporate Governance Institute.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why the corporation is failing us, and how to restore it appeared first on OUPblog.

February 13, 2013

‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’

The questions people ask about word origins usually concern slang, family names, and idioms. I cannot remember being ever asked about the etymology of house, fox, or sun. These are such common words that we take them for granted, and yet their history is often complicated and instructive. In this blog, I usually stay away from them, but I sometimes let my Indo-European sympathies run away with me. Today’s subject is of this type.

Guest is an ancient word, with cognates in all the Germanic languages. If in English its development had not been interrupted, today it would have been pronounced approximately like yeast, but in the aftermath of the Viking raids the native form was replaced with its Scandinavian congener, as also happened to give, get, and many other words. The modern spelling guest, with u, points to the presence of “hard” g (compare guess). The German and Old Norse for guest are Gast and gestr respectively; the vowel in German (it should have been e) poses a problem, but it cannot delay us here.

The hostess and her guests

The related forms are Latin hostis and, to give one Slavic example, Russian gost’. Although the word had wide currency (Italic-Germanic-Slavic), its senses diverged. Latin hostis meant “public enemy,” in distinction from inimicus “one’s private foe.” (I probably don’t have to add that inimicus is the ultimate etymon of enemy.) In today’s English, hostile and inimical are rather close synonyms, but inimical is more bookish and therefore more restricted in usage (some of my undergraduate students don’t understand it, but everybody knows hostile). However, “enemy” was this noun’s later meaning, which supplanted “stranger (who in early Rome had the rights of a Roman).” And “stranger” is what Gothic gasts meant. In the text of the Gothic Bible (a fourth-century translation from Greek), it corresponds to ksénos “stranger,” from which we have xeno-, as in xenophobia. Incidentally, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the best Indo-European scholars had agreed that Greek ksénos is both a gloss and a cognate of hostis ~ gasts (with a bit of legitimate phonetic maneuvering all of them can be traced to the same protoform). This opinion has now been given up; ksénos seems to lack siblings. (What a drama! To mean “stranger” and end up in linguistic isolation.) The progress of linguistics brings with it not only an increase in knowledge but also the loss of many formerly accepted truths. However, caution should be recommended. Some people whose opinion is worth hearing still believe in the affinity between ksénos and hostis. Discarded conjectures are apt to return. Today the acknowledged authorities separate the Greek word from the cognates of guest; tomorrow, the pendulum may swing in the opposite direction.Let us stay with Latin hostis for some more time. Like guest, Engl. host is neither an alien nor a dangerous adversary. The reason is that host goes back not to hostis but to Old French (h)oste, from Latin hospit-, the root of hospes, which meant both “host” and “guest,” presumably, an ancient compound that sounded as ghosti-potis “master (or lord) of strangers” (potis as in potent, potential, possibly despot, and so forth). We remember Latin hospit- from Engl. hospice, hospital, and hospitable, all, as usual, via Old French. Hostler, ostler, hostel, and hotel belong here too, each with its own history, and it is amusing that so many senses have merged and that, for instance, a hostel is not a hostile place.

Unlike host “he who entertains guests,” Engl. host “multitude” does trace to Latin hostis “enemy.” In Medieval Latin, this word acquired the sense “hostile, invading army,” and in English it still means “a large armed force marshaled for war,” except when used in a watered down sense, as in a host of troubles, a host of questions, or a host of friends (!). Finally, the etymon of host “consecrated wafer” is Latin hostia “sacrificial victim,” again via Old French. Hostia is a derivative of hostis, but the sense development to “sacrifice” (through “compensation”?) is obscure.

The puzzling part of this story is that long ago the same words could evidently mean “guest” and “the person who entertains guests”, “stranger” and “enemy.” This amalgam has been accounted for in a satisfactory way. Someone coming from afar could be a friend or an enemy. “Stranger” covers both situations. With time different languages generalized one or the other sense, so that “guest” vacillated between “a person who is friendly and welcome” and “a dangerous invader.” Newcomers had to be tested for their intentions and either greeted cordially or kept at bay. Words of this type are particularly sensitive to the structure of societal institutions. Thus, friend is, from a historical point of view, a present participle meaning “loving,” but Icelandic frændi “kinsman” makes it clear that one was supposed “to love” one’s relatives. “Friendship” referred to the obligation one had toward the other members of the family (clan, tribe), rather than a sentimental feeling we associate with this word.

It is with hospitality as it is with friendship. We should beware of endowing familiar words with the meanings natural to us. A friendly visit presupposes reciprocity: today you are the host, tomorrow you will be your host’s guest. In old societies, the “exchange” was institutionalized even more strictly than now. The constant trading of roles allowed the same word to do double duty. In this situation, meanings could develop in unpredictable ways. In Modern Russian, as well as in the other Slavic languages, gost’ and its cognates mean “guest,” but a common older sense of gost’ was “merchant” (it is still understood in the modern language and survives in several derivatives). Most likely, someone who came to Russia to sell his wares was first and foremost looked upon as a stranger; merchant would then be the product of semantic specialization.

One can also ask what the most ancient etymon of hostis ~ gasts was. Those scholars who looked on ksénos and hostis as related also cited Sanskrit ghásati “consume.” If this sense can be connected with the idea of offering food to guests, we will again find ourselves in the sphere of hospitality. The Sanskrit verb begins with gh-. The founders of Indo-European philology believed that words like Gothic gasts and Latin host go back to a protoform resembling the Sanskrit one. Later, according to this reconstruction, initial gh- remained unchanged in some languages of India but was simplified to g in Germanic and h in Latin. The existence of early Indo-European gh- has been questioned, but reviewing this debate would take us too far afield and in that barren field we will find nothing. We only have to understand that gasts ~ guest and hostis ~ host can indeed be related.

There is a linguistic term enantiosemy. It means a combination of two opposite senses in one word, as in Latin altus “high” and “deep.” Some people have spun an intricate yarn around this phenomenon, pointing out that everything in the world has too sides (hence the merger of the opposites) or admiring the simplicity (or complexity?) of primitive thought, allegedly unable to discriminate between cold and hot, black and white, and the like. But in almost all cases, the riddle has a much simpler solution. Etymology shows that the distance from host to guest, from friend to enemy, and from love to hatred is short, but we do not need historical linguists to tell us that.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Conversation de dames en l’absence de leurs maris: le diner. Abraham Bosse. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post ‘Guests’ and ‘hosts’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Ordering off the menu in China debates

Growing up with no special interest in China, one of the few things I associated with the country was mix and match meal creation. On airplanes and school cafeterias, you just have “chicken or beef” choices, but Chinese restaurants were “1 from Column A, 1 from Column B” domains. If only in recent China debates, a similar readiness to think beyond either/or options prevailed!

I thought of this when Reuters ran an assessment of Xi Jinping’s first weeks in power last months that in some venues carried this “chicken or beef” sort of headline: “China’s New Leader: Reformist or Conservative?” Previous Chinese leaders have often turned out to have both reformist and conservative sides. Even Deng Xiaoping, considered the quintessential reformer due to his economic policies, held the line on political liberalization and backed the brutal 1989 crackdown. Mightn’t Xi, too, end up ordering from the reformist and conservative sides of the menu?

A Valentine’s Day for the books: President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden meet with Vice President Xi Jinping of the People’s Republic of China and members of a Chinese delegation in the Oval Office, Feb. 14, 2012, several months before Xi became the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Mo Yan’s Nobel Prize win last fall, which continues to generate controversy, led some foreign commentators into a similar “chicken or beef” trap—or, rather, an “Ai Weiwei or Zhang Yimou” one. The former is an artist locked into an antagonistic relationship with the government, the latter a filmmaker who has been choreographing spectacles celebrating Communist Party rule, including both the Opening Ceremonies of the Beijing Games and a 2009 gala staged to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic. Since they are two of the only internationally prominent Chinese creative figures, some Westerners assumed Mo must be like one or the other.

In fact, the novelist shares traits with each but isn’t all that similar to either. Like China’s best-known artist, Mo has a penchant for mocking the powerful. And like the renowned filmmaker turned state choreographer, Mo works within the system, serving as a Vice-Chairman of the official writer’s association and recently agreeing to be a delegate to the Chinese People’s Consultative Political Conference. Unlike Ai Weiwei, though, Mo skewers only relatively safe targets, like the kinds of corrupt local officials that the central authorities don’t mind seeing satirized, and instead of railing against censorship, he has likened it to an inconvenience akin to airport security protocols. And unlike Zhang Yimou, one of whose best films was based on the novelist’s story “Red Sorghum,” Mo has consistently produced iconoclastic works.

If Column A choices signal compliance and Column B ones criticism, the artist and filmmaker now stick to opposite sides of the menu, while Mo Yan keeps choosing from both—and he’s not alone in this. Yu Hua, an author whose political choices I find more admirable, does this as well. He belongs to the official writer’s association and his novels, like Mo’s, generally satirize relatively safe targets. But Yu also pens trenchant essays on taboo topics, including the 1989 massacre. He’s frustrated that these can only be published abroad, but glad that they end up circulating on the mainland in underground digital versions.

A third debate, centering on the competing predictions made by “When China Rules the World” author Martin Jacques and “The Coming Collapse of China” author Gordon G. Chang, makes me think not of the value of combining Column A and Column B choices but of a different feature of Chinese restaurants that I only learned about as an adult. If you don’t like the options on the English language menu in some Chinatown eateries, you can ask to see a Chinese language one that lists additional dishes the proprietor doubts will interest most customers.

My problem with the Jacques vs. Chang debate is that I find neither pundit convincing. Jacques’ vision of China moving smoothly toward global domination glosses over the fissures within the country’s elite and the many domestic challenges its government faces. Chang continually underestimates the Communist Party’s resiliency and adaptability. His 2001 book said it would implode by 2011. Late in 2011, he told Foreign Policy readers that he’d miscalculated and they could “bet on” his prophecy coming true in 2012. In 2013, the Communist Party is still in control and somehow Chang’s still being invited onto news shows to make forecasts.

When asked whether Xi Jinping is a reformer or a conservative and whether Mo Yan is a collaborator or a critic, I can craft an answer that draws a bit from both Column A and Column B Being asked whether I side with Jacques or Chang is different. I’m left feeling like a hungry vegetarian who has been given a list made up exclusively of chicken and beef dishes—and hopes desperately that there’s another menu hidden in the back with some acceptable choices.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Chancellor’s Professor of History at University of California at Irvine, is the author of China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know (2010), an updated edition of which will be published in June.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ordering off the menu in China debates appeared first on OUPblog.

Why don’t people pay off credit card debt?

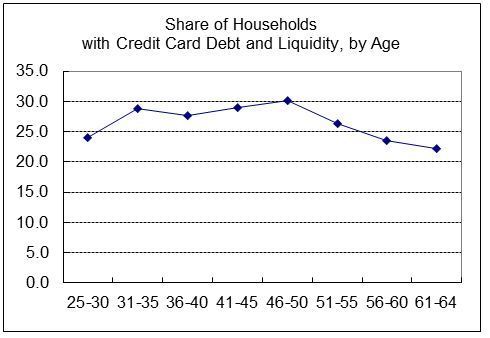

In the United States, around 25% of households tend have a substantial amount of expensive credit card debt that they carry over multiple months or even years, while also holding significant liquid assets, i.e. balances in checking and savings accounts.

For example, in 2001 data, such households paid an average 14% interest rate on the credit card, while earning nearly no return on the bank accounts. A median such household had $3800 in credit card debt, and $3000 in the bank. The average amounts were about $5800 and $7200, respectively. This behavior is quite persistent with age, as the picture below shows. It is also persistent over time, at least over the last two decades. The statistics for 2010 are very close to those for 2001.

It may seem that given the cost of revolving credit card debt, people should pay it off if they have any money in the bank. Hence, the phenomenon has been termed the “credit card debt puzzle”. Much of the discussion of it in the literature interpreted it as evidence that people lack self-control, or that they lack the financial sophistication to plan properly. In my study, I instead focused on a more familiar idea: that people hold on to money in the bank because they may need it for expenses for which credit cannot be used, and such expenses could be large and unexpected. Not only do we pay our rents and mortgages still largely by check or electronic payment from the bank, but if we have a large car or home repair to take care of, the contractor might give preferential pricing to a cash payment or simply not accept credit cards. Indeed I find that homeowners are more likely to simultaneously have debt and money in the bank, and that home repairs are an important source of large and unpredictable expenses for most households. Then, even if a household has credit card debt, it may not be optimal to draw down the bank account to zero to repay the debt. Incidentally, this idea has been advanced in the past by those who have studied the same behavior on the side of firms.

The story is intuitive; the difficult part is measuring how well this explanation can account for the puzzle, because we do not have good data on how people pay for things during a typical month, and because it is difficult to disentangle which expenses are unpredictable. Nevertheless, using several household surveys and a model of household portfolio choice, I measured both typical monthly liquid expenses (i.e. those done by cash, check, debit and other ways that require the bank account to have a positive balance), and the extent of uncertainty in them. I find that for the median person, there appears to be enough uncertainty to warrant holding on the order of $3,000 of liquid assets, even if she has credit card debt as well. In other words, many people who simultaneously have credit card debt and money in the bank are behaving without violation of self-control or rationality, under the constraint that they do not have enough money both to pay off their debt and attend to their expected monthly expense needs.

The story is intuitive; the difficult part is measuring how well this explanation can account for the puzzle, because we do not have good data on how people pay for things during a typical month, and because it is difficult to disentangle which expenses are unpredictable. Nevertheless, using several household surveys and a model of household portfolio choice, I measured both typical monthly liquid expenses (i.e. those done by cash, check, debit and other ways that require the bank account to have a positive balance), and the extent of uncertainty in them. I find that for the median person, there appears to be enough uncertainty to warrant holding on the order of $3,000 of liquid assets, even if she has credit card debt as well. In other words, many people who simultaneously have credit card debt and money in the bank are behaving without violation of self-control or rationality, under the constraint that they do not have enough money both to pay off their debt and attend to their expected monthly expense needs.

While the story accounts for the median amount of money held in the bank by those who also have credit card debt, the average household has a lot more money in the bank, and more money than credit card debt. This means that there are people who have very large amounts of liquid assets while still revolving credit card debt. While such households may face more severe risks than the average case that I measured, and while some may hold money in the bank because they foresee a possibility of a job loss and want to be able to pay at least their average expenses, it does suggest that some people may be able to improve their financial positions by examining their bank and credit card balances, and the interest costs that they pay on the credit card debt, to see if they can pay off some of their debt using their money in the bank.

Irina A. Telyukova is an assistant professor of economics at the University of California, San Diego. Her research focuses on different aspects of household saving. She has several publications on credit card debt and money demand. Her current research is about the use of home equity in retirement, in the United States and across countries, including a study about reverse mortgages. She is the author of the paper ‘Household Need for Liquidity and the Credit Card Debt Puzzle’, which appears in The Review of Economic Studies.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: (1) Graph produced by the author. Do not reproduce without permission. (2) Credit Card. By Gökhan ARICI, iStockphoto

The post Why don’t people pay off credit card debt? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 12, 2013

Will Obama address Afghanistan in his State of the Union address tonight?

President Obama is expected to announce at his State of the Union address tonight that 34,000 US troops — half the number currently stationed there — will return from Afghanistan next year. The war in Afghanistan has now continued for over ten years, since US forces entered the country after September 11th. The country, however, is still far from stable, and as Alex Strick van Linschoten, co-author of An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan, explains, US involvement has become a crutch for a country still trying to find order. “It is a reality that the only thing holding the country together at the moment is essentially the presence of the foreigners, yet at the same time it’s one of the reasons for the continuing instabilities,” Strick van Linschoten says.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Alex Strick van Linschoten has lived in Afghanistan since 2006. With Felix Kuehn, he is the co-author of An Enemy We Created: The Myth of the Taliban-Al Qaeda Merger in Afghanistan, co-editor of My Life with the Taliban, and The Poetry of the Taliban. He is currently working on a PhD at the War Studies Department of King’s College London. Follow him on Twitter @strickvl.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Will Obama address Afghanistan in his State of the Union address tonight? appeared first on OUPblog.

Anna Karenina’s happiness

It’s Valentine’s Day on Thursday, so let us celebrate the happiness of brief, all-encompassing love. We’ve paired a scene from the recent film adaptation of Anna Karenina, currently nominated for fours Oscars, with an excerpt of the novel below. In it, Anna and Vronsky discuss the happiness of their newfound love.

IT was already past five, and in order not to be late and not to use his own horses, which were known to everybody, Vronsky took Yashvin’s hired carriage and told the coachman to drive as fast as possible. The old four-seated hired vehicle was very roomy; he sat down in a corner, put his legs on the opposite seat, and began to think. A vague sense of the accomplished cleaning up of his affairs, a vague memory of Serpukhovskoy’s friendship for him, and the flattering thought that the latter considered him a necessary man, and above all the anticipation of the coming meeting, merged into one general feeling of joyful vitality. This feeling was so strong that he could not help smiling. He put down his legs, threw one of them over the other, and placing his arm across it felt its firm calf, where he had hurt it in the fall the day before, and then, throwing himself back, sighed deeply several times.

‘Delightful! O delightful!’ he thought. He had often before been joyfully conscious of his body, but had never loved himself, his own body, as he did now. It gave him pleasure to feel the slight pain in his strong leg, to be conscious of the muscles of his chest moving as he breathed. That clear, cool August day which made Anna feel so hopeless seemed exhilarating and invigorating to him and refreshed his face and neck, which were glowing after their washing and rubbing. The scent of brilliantine given off by his moustache seemed peculiarly pleasant in the fresh air. All that he saw from the carriage window through the cold pure air in the pale light of the evening sky seemed as fresh, bright and vigorous as he was himself. The roofs of the houses glittered in the evening sun; the sharp outlines of the fences and the corners of buildings, the figures of people and vehicles they occasionally met, the motionless verdure of the grass and trees, the fields of potatoes with their clear-cut ridges, the slanting shadows of the houses and trees, the bushes and even the potato ridges—it was all pleasant and like a landscape newly painted and varnished.

‘Get on, get on!’ he shouted to the coachman, thrusting himself out of the window; and taking a three-rouble note from his pocket he put it into the man’s hand as the latter turned round. The coachman felt something in his hand, the whip cracked, and the carriage rolled quickly along the smooth macadamized high road.

‘I want nothing, nothing but that happiness,’ he thought, staring at the ivory knob of the bell between the front windows of the carriage, his mind full of Anna as he had last seen her.

‘And the longer it continues the more I love her! And here is the garden of Vrede’s country house. Where is she? Where? Why? Why has she given me an appointment here, in a letter from Betsy?’ he thought; but there was no longer any time for thinking. Before reaching the avenue he ordered the coachman to stop, opened the carriage door, jumped out while the carriage was still moving, and went up the avenue leading to the house. There was no one in the avenue, but turning to the right he saw her. Her face was veiled, but his joyous glance took in that special manner of walking peculiar to her alone: the droop of her shoulders, the poise of her head; and immediately a thrill passed like an electric current through his body, and with renewed force he became conscious of himself from the elastic movement of his firm legs to the motion of his lungs as he breathed, and of something tickling his lips. On reaching him she clasped his hand firmly.

‘You are not angry that I told you to come? It was absolutely necessary for me to see you,’ she said; and at sight of the serious and severe expression of her mouth under her veil his mood changed at once.

‘I angry? But how did you get here?’

‘Never mind!’ she said, putting her hand on his arm. ‘Come, I must speak to you.’

He felt that something had happened, and that this interview would not be a happy one. In her presence he had no will of his own: without knowing the cause of her agitation he became infected by it.

‘What is it? What?’ he asked, pressing her hand against his side with his elbow and trying to read her face.

She took a few steps in silence to gather courage, and then suddenly stopped.

‘I did not tell you last night,’ she began, breathing quickly and heavily, ‘that on my way back with Alexis Alexandrovich I told him everything … said I could not be his wife, and … I told him all.’

He listened, involuntarily leaning forward with his whole body as if trying to ease her burden. But as soon as she had spoken he straightened himself and his face assumed a proud and stern expression.

‘Yes, yes, that is better! A thousand times better! I understand how hard it must have been for you’ he said, but she was not listening to his words—only trying to read his thoughts from his face. She could not guess that it expressed the first idea that had entered Vronsky’s mind: the thought of an inevitable duel; therefore she explained that momentary look of severity in another way. After reading her husband’s letter she knew in the depths of her heart that all would remain as it was, that she would not have the courage to disregard her position and give up her son in order to be united with her lover. The afternoon spent at the Princess Tverskaya’s house had confirmed that thought. Yet this interview was still of extreme importance to her. She hoped that the meeting might bring about a change in her position and save her. If at this news he would firmly, passionately, and without a moment’s hesitation say to her: ‘Give up everything and fly with me!’ she would abandon her son and go with him. But the news had not the effect on him that she had desired: he only looked as if he had been offended by something. ‘It was not at all hard for me — it all came about of itself,’ she said, irritably. ‘And here …’ she pulled her husband’s note from under her glove.

Click here to view the embedded video.

‘I understand, I understand,’ he interrupted, taking the note but not reading it, and trying to soothe her. ‘I only want one thing, I only ask for one thing: to destroy this situation in order to devote my life to your happiness.’

‘Why do you tell me this?’ she said. ‘Do you think I could doubt it? If I doubted it …’

‘Who’s that coming?’ said Vronsky, pointing to two ladies who were coming toward them. ‘They may know us!’ and he moved quickly in the direction of a sidewalk, drawing her along with him.

‘Oh, I don’t care!’ she said. Her lips trembled and her eyes seemed to him to be looking at him with strange malevolence from under the veil. ‘As I was saying, that’s not the point! I cannot doubt that, but see what he writes to me. Read—’ she stopped again.

Again, as at the first moment when he heard the news of her having spoken to her husband, Vronsky yielded to the natural feeling produced by the thoughts of his relation to the injured husband. Now that he held his letter he could not help imagining to himself the challenge that he would no doubt find waiting for him that evening or next day, and the duel, when he would be standing with the same cold proud look as his face bore that moment, and having fired into the air would be awaiting the shot from the injured husband. And at that instant the thought of what Serpukhovskoy had just been saying to him and of what had occurred to him that morning (that it was better not to bind himself) flashed through his mind, and he knew that he could not pass on the thought to her.

After he had read the letter he looked up at her, but his look was not firm. She understood at once that he had already considered this by himself, knew that whatever he might say he would not tell her all that he was thinking, and knew that her last hopes had been deceived. This was not what she had expected.

‘You see what a man he is!’ she said in a trembling voice. ‘He …’

‘Forgive, me, but I am glad of it!’ Vronsky interrupted. ‘For God’s sake hear me out!’ he added, with an air of entreaty that she would let him explain his words. ‘I am glad because I know that it is impossible, quite impossible for things to remain as they are, as he imagines.’

‘Why impossible?’ said Anna, forcing back her tears and clearly no longer attaching any importance to what he would say. She felt that her fate was decided.

Vronsky wanted to say that after what he considered to be the inevitable duel it could not continue; but he said something else.

‘It cannot continue. I hope that you will now leave him. I hope …’ he became confused and blushed, ‘that you will allow me to arrange, and to think out a life for ourselves. To-morrow …’ he began, but she did not let him finish.

‘And my son?’ she exclaimed. ‘You see what he writes? I must leave him, and I cannot do that and do not want to.’

‘But for heaven’s sake, which is better? To leave your son, or to continue in this degrading situation?’

‘Degrading for whom?’

‘For everybody, and especially for you.’

‘You call it degrading! do not call it that; such words have no meaning for me,’ she replied tremulously. She did not wish him to tell untruths now. She had only his love left, and she wanted to love him. ‘Try to understand that since I loved you everything has changed for me. There is only one single thing in the world for me: your love ! If I have it, I feel so high and firm that nothing can be degrading for me. I am proud of my position because … proud of … proud …’ she could not say what she was proud of. Tears of shame and despair choked her. She stopped and burst into sobs. He also felt something rising in his throat, and for the first time in his life he felt ready to cry. He could not explain what it was that had so moved him; he was sorry for her and felt that he could not help her, because he knew that he was the cause of her trouble, that he had done wrong.

‘Would divorce be impossible?’ he asked weakly. She silently shook her head. ‘Would it not be possible to take your son away with you and go away all the same?’

‘Yes, but all that depends on him. Now I go back to him,’ she said dryly. Her foreboding that everything would remain as it was had not deceived her.

‘On Tuesday I shall go back to Petersburg and everything will be decided. Yes,’ she said, ‘but don’t let us talk about it.’

Anna’s carriage, which she had sent away and ordered to return to the gate of the Vrede Garden, drove up. Anna took leave of Vronsky and went home.

A classic of Russian literature, this new edition of Anna Karenina uses the acclaimed Louise and Alymer Maude translation, and offers a new introduction and notes which provide completely up-to-date perspectives on Tolstoy’s classic work.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Anna Karenina’s happiness appeared first on OUPblog.

The essential human foundations of genocide

“In the end,” says Goethe, “we are creatures of our own making.” Although offered as a sign of optimism, this insight seems to highlight the underlying problem of human wrongdoing. After all, in the long sweep of human history, nothing is more evident and palpable than the unending litany of spectacular crimes. Most spectacularly of all, these properly codified public wrongs include genocide, terrorism, and crimes against humanity.

After Nuremberg, after the Holocaust, one might have expected a far-reaching change in human conduct, a welcome reduction of egregious harms occasioned by both new knowledge and new law. Yet, let us look around us at the present moment. The views are not encouraging. Look at Syria, Egypt, Afghanistan, Sudan, Uganda, and the Congo. Let us try to figure out the presumptively democratic but also riotous ethos sweeping across North Africa and the Middle East. Not to be forgotten, there is present-day Iran. Today, its faith-based leaders openly declare a determinedly genocidal intent against Israel. Let us also consider Cambodia, Argentina, Rwanda, Somalia, and the former Yugoslavia.

War and genocide are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Sometimes, war is simply the optimal means by which an intended genocide can be most efficiently carried out. How has an entire species, miscarried from the start, scandalized its own creation? Are we all potential murderers of those who live beside us?

What about slavery? In every form and permutation, this “natural” crime continues to grow, insidiously but without evident disguise, in Mali and Mauritania, and in other more conspicuous places. Shall we recall the murderous diamond mines of Sierra Leone and Liberia? And let us not forget the ever-widening radius of human child trafficking, an ancient and medieval practice, now especially visible in Nigeria and Benin.

Where is civilization? These devastating crimes are still far-flung and robust. Paradoxically, they are flourishing even now, in the “developed” and thoroughly “modern” 21st century.

For as long as we can identify the tangled skeins of world history, the corpse has been in fashion. Today, on several continents, whole nations of corpses are the rage. As for the international community, it stands by as it has so often, incredulously, with self-righteous indignation, sheepish, yet also arrogant, simultaneously calculating and lamenting its own self-reinforcing impotence.

Why? The answer has several intersecting levels, and several overlapping layers of pertinent meaning. At one level, certainly the one most familiar to political scientists and legal scholars, the basic problem lies in the changing embrace of power politics. Representing a transformation of traditional political realism, the relentless deification of states has finally reduced billions of prospective individuals to barely residual specks of significance.

In such an world, wherein the “self-determination of peoples” is a weighty value, sanguinary executions of the innocent must always be expected and applauded. Moreover, such executions, sometimes a thinly disguised or expressly secular form of religious “sacrifice,” are heralded defiantly as “sacred.” To prevent terrorism, genocide, and crimes against humanity, nation-states must first be shorn of their presumed sacredness.

Before even this can happen, however, individuals must first be allowed to discover alternative and equally attractive sources of belonging. Somehow, humanity must finally conquer the continuing incapacity of individual persons to draw true, vital, and existential meaning from within themselves.

Although generally unseen, the core problem we face on earth is the universal and omnivorous power of the herd in human affairs. This power is based upon individual submission. Ultimately, the problem of international criminality is always one of distraught and unfulfilled individuals. Ever fearful of having to draw meaning from their own inwardness, most human beings, like a moth to a flame, will draw closer and closer to the nearest collectivity.

Whatever the gripping claims of the moment, the herd spawns contrived hatreds of dissimilarity that can make even mass murder seem warm, welcome, and reasonable. Fostering a persistent refrain of “us” versus “them,” it encourages each submissive member to ceremoniously celebrate the death of “outsiders.”

The overriding task, then, must be to discover the way back to ourselves as persons. Understood in terms of the contemporary prevention of genocide, terrorism, and crimes against humanity, we are thus commanded to look beyond ordinary politics, and toward a determinedly worldwide actualization of authentic persons.

At its source, the unrecognized but critical human task is to migrate from the Kingdom of the Herd, to the Kingdom of the Self. In succeeding with this very nuanced and unambiguously grand movement, one must first want to live in the second kingdom. We must fix the fragmented and fractionated world at its most elementary individual source. Then, after so many millennia of brutishness and exclusion, we could do whatever is needed to enable our fellow human beings to find sufficient comfort and reassurance outside the segregating and always-potentially murderous herd.

Louis René Beres (Ph.D., Princeton, 1971) is the author of many books and articles dealing with international relations and international law. He was born in Zürich, Switzerland. Dr. Beres is Professor of Political Science at Purdue. He is a frequent contributor to OUPblog.

If you are interested in this subject and want to learn more, The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies is the first book to subject both genocide and the young discipline it has spawned to systematic, in-depth investigation. Thirty-four renowned experts study genocide through the ages by taking regional, thematic, and disciplinary-specific approaches. The work is multi-disciplinary, featuring the work of historians, anthropologists, lawyers, political scientists, sociologists, and philosophers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The essential human foundations of genocide appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers