Oxford University Press's Blog, page 976

February 18, 2013

Prepping for tax season

The W2s are in the mail and tax providers’ commercials on TV. Yes, it’s tax season and time for a reminder about what and why taxes are. Here’s a brief excerpt from Taxes in America: What Everyone Needs to Know by Leonard E. Burman and Joel Slemrod.

Most people know what the individual income tax is. It’s the tax that has made April 15 as iconic as the Super Bowl, without the parties or the popcorn. It’s probably the most salient tax for most people, even though these days most people owe more in payroll taxes than income taxes. The federal payroll tax is earmarked to fund Social Security retirement, survivors, and disability insurance and Medicare. Sometimes it’s called the FICA tax after the legislation that enacted it (the Federal Insurance Contributions Act). For self-employed people, it’s called the SECA tax (the Self-Employment Contributions Act). We have no idea why there are two names for basically the same tax, but it’s a fun fact that will impress your friends at cocktail parties.

What is the personal income tax?

Pretty simple: It’s a tax on individual income collected by the federal government and most states.

The federal tax is progressive, which means the tax rate rises with income. Defining income, however, is not as straightforward as you might think. The standard economist’s definition of income is the sum of what you spend and what you save. Spending is pretty straightforward.

But measuring saving is a little more complicated. It includes what we put in the bank, mutual funds, retirement accounts, and other kinds of investments. But increases in wealth that we don’t spend also add to savings (and hence to income). In many cases this unfamiliar definition lines up with the more familiar meaning—what you are paid if you are employed plus what you make from owning a business and from investments—but, in some cases that we’ll expand on later, it differs in important ways.

The income tax is much more than a tax on income. While some deductions account for the cost of earning income—for example, you can deduct the cost of uniforms that you have to wear to work—many deductions, exemptions, and tax credits are intended to provide subsidies of some sort or another. They often have little to do with the measurement of income.

The income tax is the most common point of contact between people and the government. The filing deadline of April 15 is as well-known a date as April Fools’ Day, and not many events bring on more stress than a tax audit. It’s really no surprise that, according to public opinion polls, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ranks near the bottom of American government institutions in popularity, while the Social Security Administration (SSA) tops the list: for most

Americans the IRS cashes your checks, while the SSA sends checks out. This image persists even though in recent years the IRS has dispersed hundreds of millions of payments related to, for example, the Earned Income Tax Credit and stimulus programs. Not only that, but the process of calculating what is owed is for many a complex, time-consuming, intrusive, expensive, and ultimately mysterious process, where the right answer is elusive. As the noted humorist Will Rogers said decades ago, “The income tax has made more liars out of the American people than golf has. Even when you make a tax form out on the level, you don’t know when it’s through if you are a crook or a martyr.” Many taxpayers suspect that they are suckers—when others find loopholes to escape their tax liability, they’re left holding the bag.

What is a tax?

A tax is a compulsory transfer of resources from the private sector to government that generally does not entitle the taxed person or entity to a quid pro quo in return (that’s why it has to be compulsory). Tax liability—what is owed to the government—may be triggered by a wide variety of things, such as receiving income, purchasing certain goods or services, or owning property.

Taxes can impose a substantial cost on people over and above the purchasing power they redirect to public purposes because they can blunt the incentives to work, save, and invest and can also attract resources into tax-favored but socially wasteful activities such as tax-sheltered orange orchards or construction of “see-through” office buildings (which could be profitable in the early 1980s because of tax benefits despite a dearth of tenants).

Tax policy affects the rewards or costs of nearly everything you can think of. It increases the price of cigarettes and alcohol, lowers the cost of giving to charity, reduces the reward to working, increases the cost of owning property or transferring wealth to your children, lowers the cost of homeownership, and subsidizes research and development. For this reason, tax policy is really about everything, or at least everything with an economic or financial angle.

Can taxes be discussed without getting into government spending?

The appropriate level of taxes should reflect a comparison of the benefits of what government spending provides—be it national security, social insurance, fire departments, or national parks—with the cost of taxes. When comparing the benefits to the costs, we need to bear in mind that the cost of taxes should also incorporate the disincentives and misallocations that taxes inevitably cause. For this reason a bridge that costs $500 million to build should promise benefits quite a bit higher than that.

Many Americans care little about the abstract question of whether overall taxes are too high, too low, or just about right. They care much more about their taxes, and their own tax liability. That’s a whole different matter, because whether my tax burden is $25,000 a year or $50,000 a year has absolutely no effect on the strength of our national defense, the viability of the Medicare system, or whether the local park system is well manicured. At the macro level, determining the right allocation of tax burdens depends on resolving what is fair—always a contentious issue—and how alternative tax systems that assign tax burdens differently affect economic growth.

Leonard E. Burman and Joel Slemrod are the author of Taxes in America: What Everyone Needs to Know. Leonard E. Burman is Daniel Patrick Moynihan Professor of Public Affairs at Maxwell School of Syracuse University. Joel Slemrod is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and the Paul W. McCracken Collegiate Professor of Business Economics and Public Policy in the Stephen M. Ross School of Business, at the University of Michigan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Prepping for tax season appeared first on OUPblog.

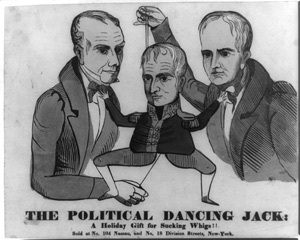

The presidents that time forgot

If you think that Barack Obama can only learn how to build a lasting legacy from our most revered presidents like Abraham Lincoln, you should think twice. I am sure that Obama knows what great presidents did that made them great. He can also learn, however, from some once popular presidents who are now forgotten because they made mistakes or circumstances that helped to bury their legacies.

Enduring presidential legacies require presidents to do things and express constitutional visions that stand the test of time. To be lasting, presidential legacies need to inspire subsequent presidents and generations to build on them. Without such inspiration and investment, legacies are lost and eventually forgotten.

Consider, for example, James Monroe who was the only man besides Obama to be the third president in a row to be reelected. Once wildly popular, he is now largely forgotten. His first term was known as the era of good feelings because it coincided with the demise of any viable opposition party. When he was reelected in 1820, he won every electoral vote but one. Yet, most Americans know nothing about his presidency except perhaps the “Monroe Doctrine” supporting American intervention to protect the Americas from European interference. The doctrine endures because subsequent presidents have adhered to it.

Consider, for example, James Monroe who was the only man besides Obama to be the third president in a row to be reelected. Once wildly popular, he is now largely forgotten. His first term was known as the era of good feelings because it coincided with the demise of any viable opposition party. When he was reelected in 1820, he won every electoral vote but one. Yet, most Americans know nothing about his presidency except perhaps the “Monroe Doctrine” supporting American intervention to protect the Americas from European interference. The doctrine endures because subsequent presidents have adhered to it.

Monroe’s record is largely forgotten for three reasons: First, his legislative achievements eroded over time. He authorized two of the most significant laws enacted in the nineteenth century — the Missouri Compromise, restricting slavery in the Missouri territory, and the Tenure in Office Act, which restricted the terms of certain executive branch officials. But, subsequent presidents differed over both laws’ constitutionality and tried to repeal or amend them. Eventually, the Supreme Court struck them both down.

Second, Monroe had no distinctive vision of the presidency or Constitution. He entered office as the fourth and last member of the Virginia dynasty of presidents. He had nothing to offer that could match the vision and stature of his three predecessors from Virginia — Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. Even with no opposition party, he was unsure where to lead the country. His last two years in office were so fractious, they became known as the era of bad feelings.

Third, Monroe had no close political ally to follow him in office. While he had been his mentor Madison’s logical successor, Monroe had no natural heir. Subsequent presidents, including John Quincy Adams who had been his Secretary of State, felt little fidelity to his legacy.

If President Obama wants to avoid Monroe’s mistakes, he must plan for the future. He should consider whom he would like to follow him and which of his legislative initiatives Republicans might support. If Obama stands on the sidelines in the next election or fails to produce significant bipartisan achievements in his second term, he risks having his successor(s) bury his legacy.

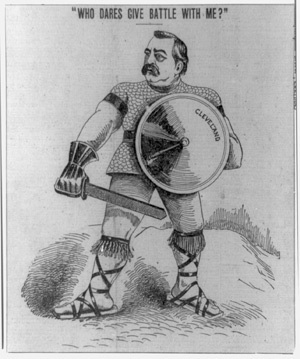

Grover Cleveland, another two-term president, is more forgotten than Monroe. If he is remembered at all, it is as the only man to serve two, non-consecutive terms as president. He was the only Democrat elected in the second half of the nineteenth century and the only president other than Franklin Roosevelt to have won most of the popular vote in three consecutive presidential elections.

Grover Cleveland, another two-term president, is more forgotten than Monroe. If he is remembered at all, it is as the only man to serve two, non-consecutive terms as president. He was the only Democrat elected in the second half of the nineteenth century and the only president other than Franklin Roosevelt to have won most of the popular vote in three consecutive presidential elections.

Yet, Cleveland’s record is forgotten because he blocked rather than built things. He devoted his first term to vetoing laws he thought favored special interests. He cast more vetoes than any president except for FDR, and in his second term the Senate retaliated against his efforts to remove executive officials to create vacancies to fill by stalling hundreds of his nominations.

Cleveland successfully appealed to the American people to break the impasse with the Senate, but his constant clashes with Congress took their toll. In his second term, his disdain for Congress, bullying its members to do what he wanted, and stubbornness prevented him from reaching any meaningful accord to deal with the worst economic downturn before the Great Depression of the 1930s. While Cleveland resisted building bridges to Republicans in Congress, Obama still has time to build some.

Finally, Calvin Coolidge had the vision and rhetoric required for an enduring legacy, but his results failed the test of time. He was virtually unknown when he became Republican Warren Harding’s Vice-President. But, when Harding died, Coolidge inherited a scandal-ridden administration. He worked methodically with Congress to root out the corruption in the administration, established regular press briefings, and easily won the 1924 presidential election Over the next four years, he signed the most significant federal disaster relief bill until Hurricane Katrina and the first federal regulations of broadcasting and aviation. He supported establishing the World Court and the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which outlawed war.

Coolidge’s vision had wide appeal. His conviction that the business of America was business still resonates among many Republicans, but he quickly squandered his good will with the Republican-led Senate when, shortly after his inauguration in 1925, he insisted on re-nominating Charles Warren as Attorney General after it had rejected his nomination. Coolidge could have easily won reelection, but he lost interest in politics after his son died in 1924. He did not help his Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover win the presidency in 1928 and said nothing as the economy lapsed into the Great Depression. His penchant for silence, for which he was widely ridiculed, and the failures of his international initiatives and economic policies destroyed his legacy.

As Obama enters his second term, he cannot stand above the fray like Monroe and Coolidge. He must lead the nation through it. He must work with Congress rather than become mired in squabbles with it as did Cleveland, whose contempt for Congress and limited vision made grand bargains impossible. On many issues, including gay rights and solving the debt ceiling, President Obama’s detachment has allowed him to be perceived as having been led rather than leading. He still has a chance to lead through his words and actions and define his legacy as something more than his having been the first African-American elected president or the controversy over the individual mandate in the Affordable Care Act. Unlike forgotten presidents, he still has the means to construct a legacy Americans will value and remember, but to avoid their fates he must use them — now.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published several books, including The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Images from The Forgotten Presidents.

The post The presidents that time forgot appeared first on OUPblog.

What does the future hold for international arbitration?

How can we outline the discussion on the law and practice of international arbitration? What is the legal process for the drafting of the arbitration agreements or the enforcement of arbitral awards? Long-time international arbitrators Constantine Partasides, Alan Redfern, and Martin Hunters — co-authors of Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration: Fifth Edition with Nigel Blackaby — sat down with the OUPblog to discuss the latest developments in their field. Watch the following videos to learn more about current views on international arbitration and what changes they expect to see in the future.

How did the idea of writing a book come about?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What challenges are arbitrators facing now?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How do you view the future of international commercial arbitration?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nigel Blackaby, Constantine Partasides, Alan Redfern, and Martin Hunter are the authors of Redfern and Hunter on International Arbitration: Fifth Edition. Nigel Blackaby is one of the partners of the international arbitration group at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in Washington, DC. Constantine Partasides is a one of the partners of the international arbitration group at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in London. Alan Redfern is the barrister and international arbitrator at One Essex Court Chambers in London. Martin Hunter is currently a barrister and international arbitrator at One Essex Court Chambers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What does the future hold for international arbitration? appeared first on OUPblog.

Do people tend to live within their own ethnic groups?

There are many policies around the world designed to encourage ethnic desegregation in housing markets. In Chicago, the Gautreaux Project (the predecessor of the Moving To Opportunity program) offered rent subsidies to African American residents of public housing who wanted to move to desegregated areas. Germany, the United Kingdom, and Netherlands, impose strict restrictions on where refugee immigrants can settle. Many countries also have “integration maintenance programs” or “neighborhood stabilization programs” to encourage desegregation. These policies are often controversial as they are alleged to favor some ethnic groups at the expense of others. Regardless of the motivation behind these policies, knowing the welfare effects is important because these desegregation policies affect the location choices of many individuals.

I am interested in one such desegregation policy in Singapore: the ethnic housing quotas. Using location choices, I analyzed how heterogeneous households sort into neighborhoods as the ethnic proportions in the neighborhood change. To do this at such a local level I had to assemble a dataset of ethnic proportions by hand-matching more than 500,000 names to ethnicities using the Singapore residential phonebook.

I am interested in one such desegregation policy in Singapore: the ethnic housing quotas. Using location choices, I analyzed how heterogeneous households sort into neighborhoods as the ethnic proportions in the neighborhood change. To do this at such a local level I had to assemble a dataset of ethnic proportions by hand-matching more than 500,000 names to ethnicities using the Singapore residential phonebook.

The ethnic housing quotas policy in Singapore is a fascinating natural experiment. It was implemented in public housing estates in 1989 to encourage residential desegregation amongst the three major ethnic groups in Singapore: Chinese (77%), Malays (14%), and Indians (8%). The quotas are upper limits on the proportions of Chinese, Malays, and Indians at a location. Locations with ethnic proportions that are at or above the quota limits are subjected to restrictions designed to prevent these locations from becoming more segregated. For example, non-Chinese sellers living in Chinese-constrained locations are not allowed to sell to Chinese buyers because this transaction increases the Chinese proportion and makes the location more segregated.

Using transactions data close to the quota limits and controlling for polynomials of ethnic proportions calculated using the phonebook, I documented price dispersion across ethnic groups that is consistent with theoretical predictions of the policy’s impact. The findings suggest a model where Chinese and non-Chinese buyers have different preferences for Chinese neighborhoods.

Indeed, my estimates show that all groups have strong preferences for living with members of their own ethnic group but the shapes of the preferences are very different across the three ethnic groups. All groups have ethnic preferences that are inverted U-shaped but with different turning points. This means that once a neighborhood has enough members of their own ethnic group, households want new neighbors from other ethnic groups. Finding tastes for diversity and differences in the shapes of ethnic preferences is consistent with previous research using data on racial attitudes from the General Social Survey in the United States and also surveys of ethnic relations in Singapore.

I used these estimates of ethnic preferences to perform welfare simulations. The seminal work by Thomas Schelling on tipping showed that externalities exist in a model with ethnic preferences because a mover affects the utility of his current and future neighbors by changing the ethnic composition of the neighborhood. Due to these externalities, Schelling showed that policies such as the ethnic quotas could potentially be used as a coordination mechanism to achieve equilibrium with integrated neighborhoods. My welfare estimates show that under the quota policy, about one-third of neighborhoods are close to the optimal allocation of Chinese, Malays, and Indians respectively.

Maisy Wong is Assistant Professor in Real Estate at Wharton, University of Pennsylvania. Her paper, ‘Estimating Ethnic Preferences Using Ethnic Housing Quotas in Singapore’ can be read in full and for free in The Review of Economic Studies.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: HDB flats at Tampines New Town. By Terence Ong. [Creative Commons], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Do people tend to live within their own ethnic groups? appeared first on OUPblog.

February 17, 2013

A quiz on Prohibition

Old Man Prohibition hung in effigy from a flagpole as New York celebrated the advent Repeal after years of bootleg booze. Source: NYPL.

How much do you know about the era of Prohibition, when gangsters rose to power and bathtub gin became a staple? 2013 marks the 80th anniversary of the repeal of the wildly unpopular 18th Amendment, initiated on 17 February 1933 when the Blaine Act passed the United States Senate. To celebrate, test your knowledge with this quiz below, filled with tidbits of 1920s trivia gleaned from The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America: Second Edition .Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The second edition of The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America thoroughly updates the original, award-winning title, while capturing the shifting American perspective on food and ensuring that this title is the most authoritative, current reference work on American cuisine. Editor Andrew F. Smith teaches culinary hist ory and professional food writing at The New School University in Manhattan. He serves as a consultant to several food television productions (airing on the History Channel and the Food Network), and is the General Editor for the University of Illinois Press’ Food Series. He has written several books on food, including The Tomato in America, Pure Ketchup, and Popped Culture: A Social History of Popcorn in America. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink is also available on Oxford Reference.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A quiz on Prohibition appeared first on OUPblog.

The tragic death of an actor

By Maya Slater

The farce is at its height: the old clown in the armchair is surrounded by whirling figures in outlandish doctors’ costumes, welcoming him into their brotherhood with a mock initiation ceremony. He takes the Latin oath: ‘Juro’, falters. His face crumples. The audience gasps – is something wrong? But the clown is grinning now, all is well, the dancing grows frenzied, the play rushes on to its end.

Not till the next day will the audience find out what happened afterwards. They carried the clown off the stage in his chair, and rushed him home. He was coughing blood, dying. He asked for his wife, and for a priest to confess him. They failed to arrive before he died.

It happened 340 years ago, on 17 February 1673, but his magnificently ironic death is still central to the French understanding of Molière. He is their greatest comic playwright, unique in that he also directed his own plays and wrote his greatest parts for himself. Centuries later, this still gives the modern audience a frisson. In The Hypochondriac, sick with TB (he had his fatal seizure during the fourth performance), Molière himself spoke the following words:

‘Your Molière’s an impertinent fellow… If I were a doctor, I’d have my revenge… when he fell ill, I’d let him die without helping him. I’d say: “Go on, drop dead!”

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

Writing those words anticipating his own death was surely tempting fate, but long before his last play, audiences had got used to seeing Molière on stage speaking lines which seemed to cast an ironic light on his own life. Nine years earlier, in The School for Wives (1662), the first of his great verse comedies, he played the part of a ridiculous old bachelor determined to marry an innocent young girl decades younger than him. Instead, the girl escapes with a young man her own age. The audience knew that Molière himself had recently married Armande – he was 40, she was 22. What must they have thought when he portrayed a thwarted older lover, gnashing his teeth in rage and frustration as his young bride escaped from his clutches?

A year later, Molière’s self-mockery has grown more explicit. The new play is The School for Wives Criticised, a short, informal sketch, ridiculing Molière’s critics in an argument about The School for Wives. Significantly, Molière didn’t defend his own play onstage. Instead, he himself played an absurd Marquis, who attacks Molière and his work: ‘I’ve just been to see it… It’s detestable.’ ‘Talk to us about its faults,’ says someone. ‘How should I know? I didn’t even bother to listen,’ replies the Marquis.

Molière’s second riposte to his critics, which again took the form of a short polemic play, The Impromptu at Versailles, was strikingly new, and still feels fresh and exciting today. We see Molière (who just this once played himself) and his troupe in rehearsal, trying desperately to get a performance together for the King and Court to see. The actors are uncooperative and annoying, which enables Molière to show himself trying to cope with them. He presents himself as unable to keep control of his unruly cast, breaking out in frustration: ‘Don’t you realise, I’m the one who carries the can…?’ When they finally start their rehearsal, Molière interrupts it to comment on The School for Wives, and to make some interesting general observations on acting. The play they are rehearsing is a conversation between two stupid courtiers. Molière again takes the part of the silly Marquis, and once more launches a comic attack on himself: ‘You’re desperate to justify Molière… don’t you think your Molière is played out [?]’ And then comes a moment unique in his work, where he takes over another actor’s part, and speaks as himself, in defence of his own art: ‘Wait a minute, You want to say all that a bit more emphatically. Listen, this is how I want it spoken…’

Of course the burning question must be: what was Molière like as an actor, and how did he perform his roles? We know he wore a heavy black moustache. We can assume that he excelled at portraying comic rage and frustration, from the number of furious outbursts he wrote for himself to perform. He put himself in ridiculous situations, hiding under the table in Tartuffe, performing a clumsy dance in The Bourgeois Gentleman, fleeing in terror dressed as a woman in M. de Pourceaugnac. But perhaps the most vivid account of his acting is found in a malicious satirical portrait written by the son of a rival actor:

‘He enters, nose to the wind, on bow legs, one shoulder thrust forward. His wig trails behind, stuffed full of bayleaves like a ham. He dangles his hands rather carelessly by his sides. His head sits on his back like a pack on a mule. He rolls his eyes. When he speaks his lines, the words are punctuated by endless hiccoughs.’

By the end, racked with TB, his performances had become less physically demanding. And performing the role which killed him that February night 350 years ago, that of the ludicrous hypochondriac, he was having to insert lines to excuse his own coughing, and played the part sitting in the red velvet chair which is still preserved as their most precious relic by the Comédie française theatre.

Maya Slater is Senior Reseach Fellow at Queen Mary, University of London. She also writes fiction and reviews theatre and books. She is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, and Other Plays by Molière.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Molière as Julius Cesar by Nicolas Mignard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post The tragic death of an actor appeared first on OUPblog.

February 16, 2013

The five stages of climate change acceptance

A few days ago, the President of the United States used the State of the Union address to call for action on climate change. The easy way to do so would have been to call on Congress to take action. Had President Obama framed his remarks in this way, he would have given a nod to those concerned about climate change, but nothing would happen because there is virtually no chance of Congressional action. What he actually did, however, was to put some of his own political capital on the line by promising executive action if Congress fails to address the issue. The President, assuming he meant what he said, has apparently accepted the need for a strong policy response to this threat.

Not everybody agrees. There has long been a political debate on the subject of climate change, even though the scientific debate has been settled for years. In recent months, perhaps in response to Hurricane Sandy, the national drought of 2012, and the fact that 2012 was the hottest year in the history of the United States, there seems to have been a shift in the political winds.

Oblique view of Grinnell Glacier taken from the summit of Mount Gould, Glacier National Park in 1938. The glacier has since largely receded. In addition to glacier melt, rising temperatures will lead to unprecedented pressures on our agricultural systems and social infrastructure, writes Andrew T. Guzman. Image by T.J. Hileman, courtesy of Glacier National Park Archives.

In 1969, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross described the “five stages” of acceptance: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. For many years, climate change discussions seemed to be about getting our politics past the “denial” stage. Over time, however, scientific inquiry made it obvious that climate change is happening and that it is the result of human activity. With more than 97% of climate scientists and every major scientific body of relevance in the United States in agreement that the threat is real, not to mention a similar consensus internationally, it became untenable to simply refuse to accept the reality of climate change.

The next stage was anger. Unable to stand on unvarnished denials, skeptics lashed out, alleging conspiracies and secret plots to propagate the myth of climate change. In 2003, Senator Inhofe from Oklahoma said, “Could it be that man-made global warming is the greatest hoax ever perpetrated on the American people? It sure sounds like it.” In 2009 we had “climategate.” More than a thousand private emails between climate scientists were stolen and used in an attempt (later debunked) to show a conspiracy to fool the world.

Now, from the right, come signs of a move to bargaining. On 13 February, Senator Marco Rubio reacted to the President’s call for action on climate change, but he did not do so by denying the phenomenon itself or accusing the President of having being duped by a grand hoax. He stated instead, “The government can’t change the weather. There are other countries that are polluting in the atmosphere much greater than we are at this point. They are not going to stop.” Earlier this month he made even more promising statements: “There has to be a cost-benefit analysis [applied] to every one of these principles.” This is not anger or denial. This is bargaining. As long as others are not doing enough, he suggests, we get to ignore the problem.

It is, apparently, no longer credible for a presidential hopeful like Senator Rubio to deny the very existence of the problem. His response, instead, invites a discussion about what can be done. What if we could get the key players: Europe, China, India, the United States, and Russia to the table and find a way for all of them to lower their emissions? If the voices of restraint are concerned that our efforts will not be fruitful, we can talk about what kinds of actions can improve the climate.

To be fair, Senator Rubio has not totally abandoned denials. While engaging in what I have called “bargaining” above, he also threw in, almost in passing, “I know people said there’s a significant scientific consensus on that issue, but I’ve actually seen reasonable debate on that principle.” In December he declared himself “not qualified” to opine on whether climate change is real. These are denials, but they are issued without any passion; his heart is not in it. They seem more like pro forma statements, perhaps to satisfy those who have not yet made the step from denial and anger to bargaining.

If leaders on the right have reached the bargaining stage, the next stage is depression. What will that look like? One possibility is a full embrace of the science of climate change coupled with a fatalistic refusal to act. “It is too late, the planet is already cooked and nothing we can do will matter.” When you start hearing these statements from those who oppose action, take heart; we will be close to where we need to get politically. Though it will be tempting to point out that past inaction was caused by the earlier stages of denial, anger, and bargaining, nothing will be gained by such recriminations. The path forward requires continuing to make the case not only for the existence of climate change, but also for strategies to combat it.

The final stage, of course, is acceptance. At that point, the country will be prepared to do something serious about climate change. At that point we can have a serious national (and international) conversation about how to respond. Climate change will affect us all, and we need to get to acceptance as soon as possible. In short, climate change will tear at the very fabric of our society. It will compromise our food production and distribution, our water supply, our transportation systems, our health care systems, and much more. The longer we wait to act, the more difficult it will be to do so. All of this means that movement away from simple denial to something closer to acceptance is encouraging. The sooner we get there, the better.

Andrew T. Guzman is Professor of Law and Associate Dean for International and Executive Education at the University of California, Berkeley. His books include Overheated: The Human Cost of Climate Change and How International Law Works, among others.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The five stages of climate change acceptance appeared first on OUPblog.

February 15, 2013

Re-introducing Oral History in the Digital Age

This week, in the spirit of our upcoming special issue on oral history’s evolving technologies, we want to (re)introduce everyone to the website Oral History in the Digital Age, a substantial collaboration between several institutions to “put museums, libraries, and oral historians in a position to address collectively issues of video, digitization, preservation, and intellectual property and to provide both a scholarly framework and regularly updated best practices for moving forward.”

We especially want to direct people to the site’s “Thinking Big” video series, which features reflections by top scholars on the evolving relationship between oral history and digital media. Below is one of the videos from the series, an interview with United States Senate historian and author of Doing Oral History Don Ritchie. We’ve also include a quiz to test readers on the oral history and digital media.

Click here to view the embedded video.

“And I discovered that the basic fundamental practices of doing oral history have not changed. The face to face interviews, the types of things you need to do to research and to engage a person, to draw them out and to ask non-leading questions, open ended questions and things like that — that stayed the same regardless of what the technology is. But everything around it changed.”

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/ media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Re-introducing Oral History in the Digital Age appeared first on OUPblog.

The bombing of Monte Cassino

On the 15th of February 1944, Allied planes bombed the abbey at Monte Cassino as part of an extended campaign against the Italians. St. Benedict of Nursia established his first monastery, the source of the Benedictine Order, here around 529. Over four months, the Battle of Monte Cassino would inflict some 200,000 causalities and rank as one of the most horrific battles of World War II. This excerpt from Peter Caddick-Adams’s Monte Cassino: Ten Armies in Hell, recounts the bombing.

On the afternoon of 14 February, Allied artillery shells scattered leaflets containing a printed warning in Italian and English of the abbey’s impending destruction. These were produced by the same US Fifth Army propaganda unit that normally peddled surrender leaflets and devised psychological warfare messages. The monks negotiated a safe passage through the German lines for 16 February — too late, as it turned out. American Harold Bond, of the 36th Texan Division, remembered the texture of the ‘honey-coloured Travertine stone’ of the abbey that fine Tuesday morning, and how ‘the Germans seemed to sense that something important was about to happen for they were strangely quiet’. Journalist Christopher Buckley wrote of ‘the cold blue on that late winter morning’ as formations of Flying Fortresses ‘flew in perfect formation with that arrogant dignity which distinguishes bomber aircraft as they set out upon a sortie’. John Buckeridge of 1/Royal Sussex, up on Snakeshead, recalled his surprise as the air filled with the drone of engines and waves of silver bombers, the sun glinting off their bellies, hove into view. His surprise turned to concern when he saw their bomb doors open — as far as his battalion was concerned the raid was not due for at least another day.

Brigadier Lovett of 7th Indian Brigade was furious at the lack of warning: ‘I was called on the blower and told that the bombers would be over in fifteen minutes… even as I spoke the roar [of aircraft] drowned my voice as the first shower of eggs [bombs] came down.’ At the HQ of the 4/16th Punjabis, the adjutant wrote: ‘We went to the door of the command post and gazed up… There we saw the white trails of many high-level bombers. Our first thought was that they were the enemy. Then somebody said, “Flying Fortresses.” There followed the whistle, swish and blast as the first flights struck at the monastery.’ The first formation released their cargo over the abbey. ‘We could see them fall, looking at this distance like little black stones, and then the ground all around us shook with gigantic shocks as they exploded,’ wrote Harold Bond. ‘Where the abbey had been there was only a huge cloud of smoke and dust which concealed the entire hilltop.’

The aircraft which committed the deed came from the massive resources of the US Fifteenth and Twelfth Air Forces (3,876 planes, including transports and those of the RAF in theatre), whose heavy and medium bombardment wings were based predominantly on two dozen temporary airstrips around Foggia in southern Italy (by comparison, a Luftwaffe return of aircraft numbers in Italy on 31 January revealed 474 fighters, bombers and reconnaissance aircraft in theatre, of which 224 were serviceable). Less than an hour’s flying time from Cassino, the Foggia airfields were primitive, mostly grass affairs, covered with Pierced Steel Planking runways, with all offices, accommodation and other facilities under canvas, or quickly constructed out of wood. In mid-winter the buildings and tents were wet and freezing, and often the runways were swamped with oceans of mud which inhibited flying. Among the personnel stationed there was Joseph Heller, whose famous novel Catch-22 was based on the surreal no-win-situation chaos of Heller’s 488th Bombardment Squadron, 340th Bomb Group, Twelfth Air Force, with whom he flew sixty combat missions as a bombardier (bomb-aimer) in B-25 Mitchells.

After the first wave of aircraft struck Cassino monastery, a Sikh company of 4/16th Punjabis fell back, understandably, and a German wireless message was heard to announce: ‘Indian troops with turbans are retiring’. Bond and his friends were astonished when, ‘now and again, between the waves of bombers, a wind would blow the smoke away, and to our surprise we saw the gigantic walls of the abbey still stood’. Captain Rupert Clarke, Alexander’s ADC, was watching with his boss. ‘Alex and I were lying out on the ground about 3,000 yards from Cassino. As I watched the bombers, I saw bomb doors open and bombs began to fall well short of the target.’ Back at the 4/16th Punjabis, ‘almost before the ground ceased to shake the telephones were ringing. One of our companies was within 300 yards of the target and the others within 800 yards; all had received a plastering and were asking questions with some asperity.’ Later, when a formation of B-25 medium bombers passed over, Buckley noticed, ‘a bright flame, such as a giant might have produced by striking titanic matches on the mountain-side, spurted swiftly upwards at half a dozen points. Then a pillar of smoke 500 feet high broke upwards into the blue. For nearly five minutes it hung around the building, thinning gradually upwards.’

Nila Kantan of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps was no longer driving trucks, as no vehicles could get up to the 4th Indian Division’s positions overlooking the abbey, so he found himself portering instead. ‘On our shoulders we carried all the things up the hill; the gradient was one in three, and we had to go almost on all fours. I was watching from our hill as all the bombers went in and unloaded their bombs; soon after, our guns blasted the hill, and ruined the monastery.’ For Harold Bond, the end was the strangest, ‘then nothing happened. The smoke and dust slowly drifted away, showing the crumbled masonry with fragments of walls still standing, and men in their foxholes talked with each other about the show they had just seen, but the battlefield remained relatively quiet.’

The abbey had been literally ruined, not obliterated as Freyberg had required, and was now one vast mountain of rubble with many walls still remaining up to a height of forty or more feet, resembling the ‘dead teeth’ General John K. Cannon of the USAAF wanted to remove; ironically those of the north-west corner (the future target of all ground assaults through the hills) remained intact. These the Germans, sheltering from the smaller bombs, immediately occupied and turned into excellent defensive positions, ready to slaughter the 4th Indian Division when they belatedly attacked. As Brigadier Kippenberger observed: ‘Whatever had been the position before, there was no doubt that the enemy was now entitled to garrison the ruins, the breaches in the fifteen-foot-thick walls were nowhere complete, and we wondered whether we had gained anything.’

Peter Caddick-Adams is a Lecturer in Military and Security Studies at the United Kingdom’s Defence Academy, and author of Monte Cassino: Ten Armies in Hell and Monty and Rommel: Parallel Lives. He holds the rank of major in the British Territorial Army and has served with U.S. forces in Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Source: U.S. Air Force; (2) Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-2005-0004 / Wittke / CC-BY-SA; (3) Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-J26131 / Enz / CC-BY-SA

The post The bombing of Monte Cassino appeared first on OUPblog.

The abdication of Pope Benedict XVI

By Gerald O’Collins, SJ

“Pope Benedict is 78 years of age. Father O’Collins, do you think he’ll resign at 80?” “Brian,” I said, “give him a chance. He hasn’t even started yet.” It was the afternoon of 19 April 2005, and I was high above St Peter’s Square standing on the BBC World TV platform with Brian Hanrahan. The senior cardinal deacon had just announced from the balcony of St Peter’s to a hundred thousand people gathered in the square: “Habemus Papam.” Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger had been elected pope.

Less than an hour earlier, white smoke pouring from a chimney poking up from the Sistine Chapel let the world know that the cardinal electors had chosen a successor to Pope John Paul II. The bells of Rome were supposed to ring out the news at once. But it took a quarter of an hour for them to chime in. When Hanrahan asked me why the bells hadn’t come in on cue, I pointed the finger at local inefficiency: “We’re in Italy, Brian.”

I was wrong. The keys to t he telephone that should have let someone contact the bellringers were in the pocket of the dean of the college of cardinals, Joseph Ratzinger. He had gone into a change room to put on his white papal attire, and didn’t hand over the keys until he came out dressed as pope.

he telephone that should have let someone contact the bellringers were in the pocket of the dean of the college of cardinals, Joseph Ratzinger. He had gone into a change room to put on his white papal attire, and didn’t hand over the keys until he came out dressed as pope.

One of the oldest cardinals ever to be elected pope, after less than eight years in office Benedict XVI has now bravely decided to retire or, to use the “correct” word, abdicate. His declining health has made him surrender his role as Bishop of Rome, successor of St Peter, and visible head of the Catholic Christendom. He no longer has the stamina to give the Church the leadership it deserves and needs.

Years ago an Irish lady, after watching Benedict’s predecessor in action, said to me: “He popes well.” You didn’t need to be a specialized Vatican watcher to notice how John Paul II and Benedict “poped” very differently.

A charismatic, photogenic, and media-savvy leader, John Paul II proved a global, political figure who did as much as anyone to end European Communism. He more or less died on camera, with thousands of young people holding candles as they prayed and wept for their papal friend dying in his dimly lit apartment above St Peter’s Square.

Now Benedict’s papacy ends very differently. He will not be laid out for several million people to file past his open coffin. His fisherman’s ring will not be ceremoniously broken. There will be no official nine days of mourning or funeral service attended by world leaders and followed on television or radio by several billion people. He will not be lifted high above the crowd like a Viking king, as his coffin is carried for burial into the Basilica of St Peter’s. The first pope to use a pacemaker will quietly walk off the world stage.

In my latest book, an introduction to Catholicism, I naturally included a (smiling) picture of Pope Benedict. But he pales in comparison with the photos of John Paul II anointing and blessing the sick on a 1982 visit to the UK; meeting the Dalai Lama before going to pray for world peace in Assisi; in a prison cell visiting Mehmet Ali Agca, who had tried to assassinate him in May 1981; and hugging Mother Teresa of Calcutta after visiting one of her homes for the destitute and dying.

In my latest book, an introduction to Catholicism, I naturally included a (smiling) picture of Pope Benedict. But he pales in comparison with the photos of John Paul II anointing and blessing the sick on a 1982 visit to the UK; meeting the Dalai Lama before going to pray for world peace in Assisi; in a prison cell visiting Mehmet Ali Agca, who had tried to assassinate him in May 1981; and hugging Mother Teresa of Calcutta after visiting one of her homes for the destitute and dying.

Yet the bibliography of that introduction contains no book written by John Paul II either before or after he became pope. But it does contain the enduring classic by Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity (originally published 1967). Both as pope and earlier, it was through the force of his ideas rather than the force of his personality that Benedict XVI exercised his leadership.

The public relations record of Pope Benedict was far from perfect. He will be remembered for quoting some dismissive remarks about Islam made by a Byzantine emperor. That 2006 speech in Regensburg led to riots and worse in the Muslim world. Many have forgotten his visit later that year to the Blue Mosque in Istanbul when he turned towards Mecca and joined his hosts in silent prayer.

Catholics and other Christians around the world hope now for a forward-looking pope who can offer fresh leadership and deal quickly with some crying needs like the ordination of married men and the return to the local churches of the decision-making that some Vatican offices have arrogated to themselves.

When he speaks at midday from his apartment to the people gathered in St Peter’s Square on 24 February, the last Sunday before his resignation kicks in, Pope Benedict will be making his final public appearance before the people of Rome. A vast crowd will have streamed in from the city and suburbs to thank him with their thunderous applause. They cherished the clear, straightforward language of his sermons and homilies, and admire him for what will prove the defining moment of his papacy—his courageous decision to resign and pass the baton to a much younger person.

Gerald O’Collins received his Ph.D. in 1968 at the University of Cambridge, where he was a research fellow at Pembroke College. From 1973-2006, he taught at the Gregorian University (Rome) where he was also dean of the theology faculty (1985-91). Alone or with others, he has published fifty books, including Catholicism: A Very Short Introduction and The Second Vatican Council on Other Religions. As well as receiving over the years numerous honorary doctorates and other awards, in 2006 he was created a Companion of the General Division of the Order of Australia (AC), the highest civil honour granted through the Australian government. Currently he is a research professor of theology at St Mary’s University College,Twickenham (UK).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: Pope Benedict XVI during general audition By Tadeusz Górny, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Church of the Carmine, Martina Franca, Apulia, Italy. Statues of Mother Teresa and Pope John Paul II By Tango7174, creative commons licence via Wikimedia Commons

The post The abdication of Pope Benedict XVI appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers