Oxford University Press's Blog, page 972

March 2, 2013

The Constitution and the health care debate

Many Americans share a deep reverence of the Constitution — perhaps to the country’s detriment. While we have learned from the Founders and Framers, they didn’t issue commandments. They left room for interpretation, change, and even some disobedience. Louis Michael Seidman, author of On Constitutional Disobedience, spoke to us about how this eighteenth century document is influencing our modern debate on health care and his controversial take on how to bring American laws up to date.

How does the constitution influence the debate on health care?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How can the United States maintain its civil liberties?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What’s your take on Seidman’s views? Leave your thoughts in the comments.

Louis Michael Seidman is Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Constitutional Law at Georgetown University. His books include On Constitutional Disobedience, Our Unsettled Constitution, Equal Protection of the Laws, and Silence and Freedom.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Constitution and the health care debate appeared first on OUPblog.

March 1, 2013

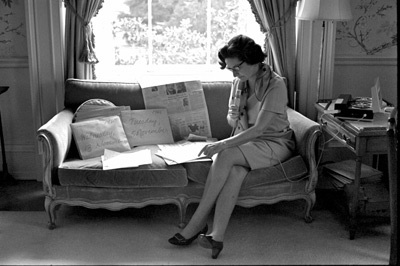

Michael Gillette on Lady Bird Johnson and oral history

Lady Bird Johnson recording her White House diary. Image courtesy of the LBJ Library.

This episode of the OHR on OUPblog, I take the opportunity to interview Michael Gillette, author of Lady Bird Johnson: An Oral History. In this podcast, Gillette discusses the book, the research behind and process of interviewing “Mrs. Johnson,” and his current role as executive director of Humanities Texas. Our host, Oxford University Press, published Lady Bird Johnson at the end of last year.Among Gillete’s excellent stories and insight, I get to use one of my favorite mantras: prior preparation prevents piss poor performance. I also avoid asking if Gillette is related to one half of the Penn & Teller magical, comedic duo. Caitlin nixed that idea in advance, noting that no one under 30 (probably over 30, too) would understand my humor. Your loss. [You’re welcome. --Caitlin]

[See post to listen to audio]

Or download the podcast directly.

Michael L. Gillette directed the LBJ Library’s Oral History Program from 1976 to 1991. He later served as director of the Center for Legislative Archives at the National Archives and is currently the executive director of Humanities Texas in Austin. He is the author of Lady Bird Johnson: An Oral History and Launching the War on Poverty: An Oral History.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Michael Gillette on Lady Bird Johnson and oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

An Oxford Companion to the 2013 Papal Elections

Yesterday Pope Benedict XVI retired from his papal duties with the intention to lead a life of prayer in seclusion. His sudden abdication has left many of the faithful wondering who will step in as his successor. While there are rumors that the next Pope may be from Latin America or Africa, the exact process of how a Pope is chosen is still shrouded in mystery. With the help of OUP’s resources, I hope to help answer the questions of those whose curiosity in Papal elections and history was sparked by the recent turn of events.

THE PAPACY’S EARLIER YEARS

To better understand the how the modern Papacy came about, it’s good to explore how it has evolved from its earlier years to recent times. Here are some helpful resources that go into greater detail on Papal history:

The Papal Monarchy: The Western Church from 1050 to 1250

A History of the Popes 1830-1914

Catholicism: The Story of Catholic Christianity

THE MODERN PAPACY

While the lives of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI have been well documented, how much is known of the modern popes that came before them? Here’s a rundown of the 20th Century popes who influenced the Papacy as we know it today:

St. Pius X: The son of a seamstress and a village postman, Pius X wasn’t the first choice to succeed Leo XIII. An imperial veto from Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria forced the cardinals to go into another round of voting in protest of the Emperor’s involvement. Pius X was eventually chosen because the cardinals preferred a successor who would take the Papacy in a different direction from his predecessor. He was renowned for his more traditional take on Catholicism, his reforms on Canon Law, and his major reforms within the church. Pius X remained in office until his death in 1914 and was canonized in 1954.

Benedict XV: He was the son of a poor but aristocratic family who earned doctorates in theology and canon law. His later training in papal diplomatic service made him a successful candidate to succeed Pius X. He is remembered for his pontificate occurring during the First World War, having the Vatican remain neutral during that time, and ending the feud between traditionalists and modernists. He remained in office until his death in 1922.

Pius XI: The son of a silk factory manager, he was elected as Pope after a long and difficult election process. He is most remembered for the Lateran Pacts (1929), where the Vatican came to be recognized as a neutral, independent state. Other achievements during his time as pope include his involvement with missions, consecrating the first Chinese bishops, and modernizing the Vatican Library. He remained in office until his death in 1939.

Pius XII: As the son of a lawyer with ties to the Vatican, he was inspired early on to pursue the priesthood. He succeeded Pius XI after a short election because he was one of the most influential cardinals at the time and because of his extensive experience in foreign policy and relations. He is known for heavily promoting peace before the onset of World War II. During the war he was known for his neutrality and for making the Vatican an asylum for refugees during Hitler’s occupation of Rome. His dedication to peace and neutrality helped raise the number of dioceses to 2,048 by the time of his death. He remained in office until his death in 1958.

John XXIII: Born in a small village, he served as an ambassador (called a nuncio) with his diplomatic missions to Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece. He was elected Pope after a three day election, mainly due to the fact that many Cardinals believed his advanced age would lead to a short papacy. He is famous for calling together the Second Vatican Council in order to revive and update the teachings and organization of the church. He remained in office until his death in 1963.

Paul VI: The often ill son of a lawyer and newspaper editor, Paul pursued his early theological studies from his home. He was his predecessor’s confidant and played an important role in helping to bring about the Second Vatican Council. Due to his close relationship with John XXIII, he was viewed as the next likely successor and was elected Pope after six ballots. As he promised his predecessor, he continued the Second Vatican Council and dedicated himself to implementing the changes in canon law brought about by the council. He is well-known for traveling with the nickname the “pilgrim pope” and for declaring St Teresa of Avila (1515–82) and St Catherine of Siena (1347–80) the first women doctors of the church. He remained in office until his death in 1978.

John Paul I: From a working class family with socialist ties, he was appointed the bishop of Vittorio Venetoby by his predecessor in 1958. He became an active and eminent member of Italian Conference of Bishops before being elected pope. After a short round of ballots in 1978, he was chosen as the new pope mainly out of the desire for a new style of leadership. He is most remembered for his short papacy.

POPES WHO HAVE RESIGNED

You’ve heard it countless times on the news; Pope Benedict XVI is the first pope in about 600 years to resign. But who were the previous popes who made the same decision and what were their reasons for leaving office? Here are a few notable popes who either chose or were coerced into retirement:

St. Silverius: This pope’s papacy was plagued by political intrigue and he was forced to abdicate after accusations of being pro-Goth. While he was later given the chance for a fair trial, he was exiled again by his successor Vigilius.

John XVIII: Little is known about his time in office, but it is speculated that his Papacy was a result of the influence of John II Crescentius. It is known that he died at a monastery after possibly resigning as pope. The reasons behind his resignation are still up to speculation, but some believe his falling out of favor with John II Crescentius may have been one of the reasons.

Celestine V: Elected as pope in 1294 after much persuasion because of his hesitance to take on the role. He chose to abdicate after five months because of his unwillingness to act as a puppet under the control of Charles II of Sicily.

For more information on papal resignations, you can read last week’s Papal resignations through the years.

PAPAL CANDIDATES 2013

Along with the ceremony of the papal elections themselves, the leading candidates are still a matter of speculation. Business Insider has compiled a helpful list of the rumored front runners for the upcoming election:

Cardinal Marc Ouellet

Where is he from: Canada

Possibility of Election: He’s the current Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops and has extensive experience in missionary work. He’s also known to be fluent in six languages.

Cardinal Peter Kodwo Appiah Turkson

Where is he from: Ghana

Possibility of Election: He is the current President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. He also has the reputation of being a good public speaker and he represents the global presence of Catholicism.

Cardinal Leonardo Sandri

Where is he from: Argentina

Possibility of Election: Currently the President of the Congregation for the Oriental Churches and is said to speak five languages. He is also rumored to have influential friends in the Curia.

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi

Where is he from: Italy

Possibility of Election: Current President of the Pontifical Council for Culture and a well-respected man within the church.

ELECTION PROCESS INFORMATION

The most commonly known aspect of the election process is the smoke signal, black smoke to indicate that the cardinals are still undecided and white to indicate that a choice has been made. But what occurs just before the smoke signal? What is the election process like? CNN’s Bruce Schneier gives us the step by step process of how popes are elected:

I. In the first phase of voting, cardinals are given paper ballots to write their choices on. After the ballots are handed out, nine of the cardinals are chosen as election officials that are divided into three groups: the group who counts the votes, the group who checks the ballot results, and the group who collects the votes from cardinals who could not be present. After the election officials are chosen, the cardinals all cast their votes.

II. The second phase involves each cardinal individually placing their ballots into a chalice. The third group also adds in the votes of the cardinals who could not be present. After all the cardinals have placed their ballots in the chalice, the group who counts the votes begins their work. The first official shakes the chalice and then the three officials count the ballots while passing them into a second chalice. The third official reads the names aloud while all three officials keep a tally of the names chosen.

III. The final phase involves the ballot counters tallying up all the candidates from the second phase. After their work is done, the group who checks the ballot results go over the entire process and the results. After ensuring that the election process was fair, they burn the ballots. Depending on their findings, the election will conclude with a new pope or the election process will start over again.

MORE RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

If you crave even more information on all things Papal, here are a few more resources to look into:

The abdication of Pope Benedict XVI

Papacy and the Atlantic World

“African Christian Communities”

Heirs of the Fisherman: Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession

The Catholic Church: What Everyone Needs to Know (forthcoming)

Ratzinger’s Faith: The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI

Catholicism: A Very Short Introduction

The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, 3rd edition

The American Catholic Revolution: How the Sixties Changed the Church Forever

The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice

Sense of the Faithful: How American Catholics Live Their Faith

Dictionary of Popes

Kimberly Hernandez is a social media intern at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) St. Peter’s and the Vatican, Rome. Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs. Source: NYPL Digital Gallery.

(2) Pope Benedict XVI during general audition, 2007. Photo by Tadeusz Górny. Released into the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An Oxford Companion to the 2013 Papal Elections appeared first on OUPblog.

Medical Law: A Very, Very, Very, Very Short Introduction

By Charles Foster

By the standards of most books, the Very Short Introduction to Medical law is indeed very short: 35,000 or so words. As every writer of a VSI knows, it is hard to compress your subject into such a tiny box. But I wonder if I could have been much, much shorter. 88 words, in fact.

Here’s my re-write:

1. Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

2. There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

This would hardly be saleable as a VSI, but is there anything else to say? Certainly it’s arguable that the rest of what we describe as ‘medical law’ (at least in a publicly funded healthcare system) is simply commentary on it.

The words, of course, are those of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. It’s the most elastic of all the Convention articles. It stretches to places of which the original draftsmen (probably thinking of preventing phone tapping and other Big Brother-ish activities by the State’s shadowy men in raincoats) would never have dreamed.

It effortlessly and unsurprisingly encompasses confidentiality. It’s not hard to see how it can generate a right to informed consent, determine what should happen to my body parts, have a fair stab at drafting a definition of death, and, generally, require clinicians to act in all their dealings with me in just the sort of respectful way that makes a good doctor a good doctor. It has been found to extend to the end of life, enabling me (so long as the criteria in 8(2) are satisfied), to end my life at the time and in the circumstances that I choose. It’s a structure built by autonomy and dignity, and is now their natural home, from which they preside over the law.

Article 8 doesn’t just let me do things. It prefers to permit than to deny, but it’s capable, using the language of 8(2), of stopping me do things too. If I want to nail my genitals recreationally to a piece of plywood, or to ask a surgeon to cut off all my limbs because that’s this season’s look, it’s likely to have something stern to say.

But ultimately some commentary is necessary. The tension between 8(1) and 8(2) (which is the real tension in much medical litigation) needs to be measured and described. Fundamental and parthenogenetically fecund though it is, perhaps Article 8 needs to acknowledge its need for insemination by ideas such as personhood and the right to reproduce, and its reliance on other principles (the right to life, for instance, embodied in the law of murder, manslaughter, and the prohibition of assisted suicide). Perhaps, too, duties aren’t just the flip side of rights, and perhaps we need somehow to oblige doctors to get out of bed in order to be respectful. We all know that highly elastic principles and people tend not to be great on the details.

Having looked at it, I’m reassured that the remaining 34,912 words were justified.

Charles Foster is a Fellow of Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, a tutor in medical law and ethics at the University of Oxford, and a barrister (practising in medical law) at Outer Temple Chambers, London. He read law and veterinary medicine at the University of Cambridge. He is the author, editor or contributor to over thirty five books, including Medical Law: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Medical Law: A Very, Very, Very, Very Short Introduction appeared first on OUPblog.

February 28, 2013

Metre and alliteration in The Kalevala

By Keith Boseley

In the original final Finnish version of the Kalevala, published in 1849 (17: 523 – 526):

Ei sanat salahan joua

eikä luottehet lovehen;

mahti ei joua maan rakohon,

vaikka mahtajat menevät.

Before we translate, certain features can be pointed out: a line has eight syllables; stress always falls on the first syllable of a word; every line has alliteration. Soon after the Kalevala came out in its final version, the Baltic German linguist Franz Anton Schiefner (1817 – 1879) published the first German translation in 1852. He ironed out the metre into a trochaic tetrameter, and disregarded the alliteration. Later German translations have followed his example. Hans and Lore Fromm’s 1967 edition (from Finnish) also recast the text into pairs of lines:

Worte werden nicht verborgen, Sprüche fallen nicht in Spalten,

Zauber stürzt nicht in die Erdschlucht, wenn auch Zauberwisser gehen.

Elias Lönnrot and Kalevala heroes on the monument by Emil Wikström in Helsinki

Now the bad news: The Song of Hiawatha, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 long narrative poem, imitated Schiefner for his retelling of Native American legends, and has proved a bestseller ever since, despite endless — and deserved — parodies by Lewis Carroll, among others. Result: for readers of English, the Kalevala is in trochaic tetrameters. W. F. Kirby (1844 – 1912), the English entomologist and folklorist whose 1907 version was the first complete English translation from the Finnish, rendered it thus:Till no spells are hidden from me,

Nor the spells of magic hidden,

That in caves their power is lost not,

Even though the wizards perish.

The original Kalevala metre remains a mystery — see the opening quotation. Many Finns and translators into a variety of languages make matters worse by following Schiefner. The present English translator has learnt from his native tradition, begun by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey’s (1516/17 – 1547) sixteenth-century versions of Virgil, by avoiding original metres. Thousands of lines before tackling the Kalevala, I developed a syllabic line of seven — sometimes five, less often nine — owing something to medieval Welsh. This has enabled me, in my Oxford World’s Classics edition, to translate almost literally:

Words shall not be hid

nor spells be buried;

night shall not sink underground

though the mighty go.

The Kalevala’s influence lies not only in Finnish history — such as its essential role in fostering a distinct sense of national cultural identity that resulted in its independence in 1917 following the Russian Revolution — but elsewhere too. One of the more famous examples may be found in J.R.R. Tolkien, who credited several aspects of the Finnish epic and the language as part of the inspiration behind The Lord of the Rings. Väinämöinen, the wise old sage, was a source of inspiration for the character of Gandalf, and Tolkien was rapt with excitement upon discovering a Finnish Grammar, as he noted in a letter to W.H. Auden, also one-time professor at the University of Oxford:

It was like discovering a complete wine-cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavour never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me; and I gave up the attempt to invent an ‘unrecorded’ Germanic language, and my ‘own language’ – or series of invented languages – became heavily Finnicized [sic] in phonetic pattern and structure.

The Kalevala remains a source of only semi-discovered beauty and incredible imagination. Have you ever been challenged to tie an egg into invisible knots? (You may use magic.)

Keith Boseley has published several collections of poems and a number of translation, mainly from French, Portuguese, German, and Finnish. In 1991 he was made a Knight, First Class, of the Order of the White Rose of Finland. An audio book of his edition of the Kalevala was published by Naxos this month. The cover art for the audio book is by Ben Boseley.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Elias Lönnrot and Kalevala heroes on the monument by Emil Wikström in Helsinki. Photo by Дар Ветер [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Metre and alliteration in The Kalevala appeared first on OUPblog.

Music during World War II

When politicians attempt to capture a unifying moment, they often choose the music of Aaron Copland. Why? Classical music in 1940s America had a ubiquitous cultural presence at time when national identity consolidated. Drawing on music history, aesthetics, reception history, and cultural history, Sounds of War recreates the remarkable sonic landscape of the World War II era. We present a brief excerpt of the forthcoming book below.

Music also played its role. Whether as an instrument of blatant propaganda or as a means of entertainment, recuperation, and uplift, music pervaded homes and concert halls, army camps and government buildings, hospitals and factories. A medium both permeable and malleable, music was appropriated for numerous war-related tasks. Indeed, even more than movies, posters, books, and newspapers, music sounded everywhere in this war, not only in its live manifestations but also through recording and radio. So far as the U.S. is concerned, even today, musicians such as Dinah Shore, Duke Ellington, and the Andrew Sisters populate the sonic imaginary of wartime. Whether performed by “all-girl” groups such as the International Sweethearts of Rhythm or by military bands conducted by Glenn Miller and Artie Shaw, swing and boogie-woogie entertained civilians at home and G.I.s stationed abroad. Numerous films created to boost both civilian and military morale—from Star Spangled Rhythm (1942) and Stage Door Canteen (1943) to Anchors Aweigh (1945)—featured star-studded numbers presenting country sounds, barbershop quartets, swing, sentimental ballads, and hot jazz, among others. Likewise, nostalgic songs such as “I’ll Be Seeing You” (1938) and belligerent tunes as “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” (1942) had their place on popular radio programs, USO shows and V-Discs.

Star Spangled Rhythm, for example, brings together all the popular styles well known for this period, and indeed often regarded as iconic for it. However, it does so in what might sometimes seem surprising ways, if with obvious programmatic intent. The big production number “Swing Shift,” set in an aircraft factory, combines jazzy swing with traditional barn dances, musical and dance styles that might otherwise have been hailed as incompatible. Another number merges the style and performance of the African American Golden Gate Quartet with the more sentimental duet “Hit the Road to Dreamland” (marked as “white” by both its performance style and its crooning arrangement) performed by Mary Martin and Dick Powell. Hot jazz is represented, inevitably, by a Harlem street scene featuring the star African American dancer Katherine Dunham. And equally inevitably, the film ends with a patriotic number, “Old Glory,” where Bing Crosby, at the head of a crowd before a stage-set Mount Rushmore, sings in praise of the U.S. flag, engages with a Doubting Thomas, and leads representatives of the states (including a gospel group for Georgia) into a choral hymn of patriotic solidarity.

Yet that final number has still more surprises to offer given its obvious, and no doubt deliberate, echoes of another well-known patriotic piece, John La Touche and Earl Robinson’s Ballad for Americans (1939). Here we move from “popular music” in the direction of a repertory that was, and is, often labeled “classical.” I use that term with all due caution—and mostly for the lack of anything better—without asserting value judgments on its superiority over other musical forms and acts, nor limiting my inquiry to elitist “highbrow” domains: indeed, one of my points is that wartime classical music is not at all highbrow—just as popular music is not lowbrow—but does its cultural work in differently configured social spheres. However, for all the scholarly emphasis on popular culture in the wartime period, what in fact distinguished musical life in the U.S. during World War II from other times of war was the significant role assigned to classical music: in 1940s America it had a cultural relevance and ubiquity that is hard to imagine today.

The out-and-out involvement of the entire nation into the war meant that all music was to serve in its needs, and that also included types of music that had already gained a significantly broader presence in U.S. culture during the 1930s. This new prominence was achieved in New Deal America—and we shall see how New Deal institutions transferred to wartime ones—especially through music appreciation courses in schools and colleges, nationwide radio broadcasts of major orchestras and the Metropolitan Opera House, and gramophone catalogues that offered a repertoire of classics for the middlebrow household. Through these educational and marketing initiatives, classical music from symphonies to Schubert songs carried added value as cultural capital moving beyond popular musical entertainment. Also at stake, however, was the U.S.’s role not just as a military power, but also as a force for civilization. In composer Henry Cowell’s words, musicians of all stripes were “shaping music for total war.” Indeed, no other period in U.S. history mobilized and instrumentalized culture in general, and music in particular, so totally, so consciously, and so unequivocally as World War II.

Musicians—whether a singing cowboy such as Gene Autry or an opera singer such as John Carter from the Met—saw themselves as cultural combatants. Aaron Copland, for example, was just one of many classical composers deeply involved in the war effort. Marc Blitzstein, Elliott Carter, Henry Cowell, Roy Harris, and Colin McPhee all participated in the propaganda missions of the Offi ce of War Information (OWI). Earlier, in summer 1942, Blitzstein had become attached to the Eighth Army Air Force in London where he was commissioned to compose his Airborne Symphony. Samuel Barber also served in the Army Air Force (but stationed in the U.S.), writing both his Second Symphony and his Capricorn Concerto, “a rather tooting piece, with fl ute, oboe and trumpet chirping away” and thus fi t for the times, as he assured Copland.5 Civilian commissions for new music focused on patriotic and “martial” subjects, most famously the series of fanfares that Eugene Goossens, the chief conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, requested from American composers and from European musicians in exile: Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man is a still much performed result. Similarly, the League of Composers (financed by the Treasury Department) commissioned seventeen works on patriotic themes, including Bohuslav Martinů’s Memorial to Lidice and William Grant Still’s In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy. Classical music was heard on the radio and in film scores, whether Yehudi Menuhin playing Schubert’s Ave Maria in Stage Door Canteen or Victor Young infusing the entire score for Frenchman’s Creek (1944) with Claude Debussy’s Clair de lune. Concert music was performed in the Armed Forces, for example by the Camp Lee Symphony Orchestra or the U.S. Navy Band String Quartet; and it even played a role in the work of the Office of Strategic Services (the predecessor to the CIA), whose director, General “Wild Bill” Donovan, was known not only to support experiments in using music as cipher code, but also to involve himself in music-related propaganda efforts.

Annegret Fauser is Professor of Music and Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. She is author of Sounds of War: Music in the United States during World War II and Musical Encounters at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair and co-editor of Music, Theater and Cultural Transfer: Paris 1813-1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Music during World War II appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten ways to rethink ‘Arthur’s Britain’

Guy Halsall, author of Worlds of Arthur: Facts and Fictions of the Dark Ages, illuminates the reality behind the façade of myths and legends concerning King Arthur. He outlines here ten ways which will challenge what you thought you knew about the legendary King Arthur and the world in which he was supposed to have lived.

1. Stop looking for ‘King Arthur’. There is no conclusive evidence that he ever existed and none at all that would allow us to say anything reliable about him if he did. He might have lived … or he might not. That’s all there is to say and, unless some entirely new piece of evidence is discovered (unlikely), that is all there will ever be to say on the topic (and don’t believe anyone who tells you otherwise). There are far more interesting things to think about in Britain between 400 and 600. Get over it!

2. Forget the characters, artefacts, and places of legend. If there’s hardly any evidence to support Arthur’s existence, there is even less for Guinevere, Lancelot and the other Knights of the Round Table, for Excalibur or Camelot. While the evidence we have suggests that some people (not many) knew of an Arthur figure, legendary or historical, in the first millennium, the other people, places and things of the legends were all invented after 1000.

Glastonbury Tor: Often supposed to be the Isle of Avalon from Arthurian legend (via iStockPhoto)

3. Abandon the written sources. Sadly almost no reliable written evidence exists for a political narrative history of Britain between c.410 and c.597. Gildas’ On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain (written c.475-c.550) tells many things about the church, mentalities and some politics of his day, but little in detail – and we don’t know where or when he was writing. The Life of Germanus of Auxerre tells us a little about the bishop’s visit to the island in 429 and (maybe) again in the 440s, but not much. That apart, every datable source for political history is late (from at least 200 years after Arthur’s supposed lifetime around 500!) and written for the political agendas of its own day.

4. It’s not just about the South — get some context! What happened in Britain south of Hadrian’s Wall will only make sense if viewed in a broader context, one that not only takes into account the north of Britain but the whole of western Europe in the fifth and sixth century. (See point 5.)

The Pictish fort at Dundurn at the head of Strathearn, © Guy Halsall 2013; all rights reserved.

5. ‘Arthur’ was not the defender of the Romans. Whatever happened as the late Roman diocese of Britanniae (The Britains) became a series of kingdoms, English and Welsh, it did not involve the destruction of Roman Britain by barbarian invaders. Roman civilisation in Britain collapsed in the crisis of the Empire around 400, long before any ‘Saxons’ took over. Any ‘proto-Arthur’ was not fighting to defend Roman civilisation; that had long gone. Fifth- and sixth-century change in Britain only makes sense when you take a view that crosses the artificial boundary between ‘Roman archaeology’ and ‘early Anglo-Saxon’ (or sub-Roman, or early historic in other areas).

6. ‘Arthur’ did not fight against the Saxon invasion. The details of the written sources have long since been dismissed by serious scholars but the framework they provided remains. That framework sees Arthur and/or the Britons fighting a defensive war against invading ‘Saxons’, gradually pushing them to the west. But that is an image that suited particular moments of eighth- to tenth-century politics and the histories that were written then. Nowhere in the fifth- and sixth-century West did politics play out simply in terms of conquering barbarians fighting defending Roman provincials. Without the dubious written sources (point 2) there is no evidence that Britain was any different.

A defence against the Saxons? Or a fortified depot safeguarding Roman Britain’s crucial links with the rest of the Empire? The mighty walls of the ‘Saxon Shore’ fort at Richborough (Kent), © Guy Halsall 2013, all rights reserved.

7. Britain wasn’t united — fifth-century factions. Fifth-century politics everywhere else in western Europe were about faction-fighting. Regional alliances of Roman aristocrats and barbarian soldiers fought other Romano-barbarian factions for control. This pattern looks quite like that of Anglo-Welsh alliances that we can see when we first get reliable political historical evidence in the earlier seventh century. The political map was probably complex and ever-changing. A ‘Proto-Arthur’, therefore, could have been a ‘Briton’ whose troops were ‘Saxons’, or whose kingdom ‘became’ Saxon. People like that existed. If he was it’s not surprising he was left with nowhere to go but legend.

8. Stop looking for Saxons or Britons. Archaeological evidence should not be discussed as relating to Saxons or Britons. Such identities were political. They were multi-layered, they could be adopted or abandoned in certain circumstances and they didn’t only — or perhaps even primarily — relate to the places where someone or their family originated. Therefore specific types of finds, buildings or burials are unlikely to tell you the geographical or biological origins of a site’s occupants or users and, if they do, that will not necessarily tell you what their ethnic identity was. In any case, the archaeology maps very badly onto the old idea of a simple east-to-west advance across the landscape by English (Anglo-Saxon) settlement and kingdoms.

9. There were no ‘knights’. Any Arthur proto-type didn’t win his wars because of his use of heavy cavalry. There’s no evidence for fifth-/sixth-century ‘Arthurian’ heavy cavalry. Most if not all war-leaders at the time led warriors who had horses, who sometimes fought mounted and sometimes on foot.

10. Start thinking in terms of a mess. Forget the neat lines on the map, the orderly ‘front-line’ of traditional views. Think of a kaleidoscope. A mess is maybe less romantic but more interesting and exciting.

Guy Halsall has taught at the universities of London and York, where he has been a professor of history since 2006. He has published widely on a broad range of subjects and his most recent book Worlds of Arthur: Facts and Fictions of the Dark Ages explores King Arthur, the myths, the legends, the history — and what we can ever really know about him.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Ten ways to rethink ‘Arthur’s Britain’ appeared first on OUPblog.

February 27, 2013

Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2013

My usual thanks to those who have commented on the posts, written me letters privately or through OUP, and corrected the rare but irritating typos. I especially appreciate comments that deal with the languages remote from my sphere of interest: Arabic, Farsi, Romany, and so forth. But, even while dealing with the languages that are close to my area of expertise (for example, Sanskrit and Frisian), quite naturally, I feel less comfortable in them than in English, German, or Icelandic (my “turf”). I remember my astonishment when as a student I read an introduction to Meillet’s booklet on Germanic in which he, among other things, said that he had added some small things to the previous edition and corrected the mistakes. Meillet, a living god, the greatest specialist in the history of Indo-European, corrected his mistakes! More than fifty years later that surprise has not worn off. Of course, I understand, quod licet Iovi…, but still….

Some things I say sound wrong, but I say them intentionally, not to complicate matters. Having spent decades on grammatical morphology, Propp’s morphology of the folk tale (and thanks to him on Goethe’s morphology), I, as could be suspected, know that morph- is a Greek root. But the modern English verb morph (which I dislike) did not come to us from Greek. Even morpheme and its cognates reached English from French, and there their source was usually Latin. So, when I called morph a Latinism, I did not commit a terrible error. The same is true of gh- in the Sanskrit verb I cited in connection with guest/host. Brugmann, the author of the etymology to which I referred, for an obvious reason did not mark palatalization and I reproduced his form because I did not want to modernize him. However, as noted, all suggestions, friendly and critical, are welcome, even though like most people I prefer to be praised rather than hauled over the coals.

The present perfect.

The comment of our correspondent reflects the classic rule: this tense allows the speaker to include a past action in the present moment, but the important thing is not the formulation but the various uses of the tense in related languages. The perfect is not a Germanic invention, but the analytic form that needs an auxiliary verb and a participle is a Germanic-Romance innovation. American speakers do not “include” the past in the present when they say he just left, while British speakers do (he has just left). With today, usage varies. I saw her today seems to be acceptable even in British English, though today, by definition, is not yet over. In teaching foreigners, it is important to mention “national” distinctions. Fortunately or unfortunately, unified usage for the countries in which English is spoken does not exist, though in cultivated written form the distinctions are much less noticeable.

Whose advocate is this laughing devil?

Advocate versus advocate for.I (have) received a letter in which the writer refuses to accept for after advocate. “I now hear and read it… even on public radio and in print. Will the commonality of such misusage contribute to its becoming acceptable? (I fear this may already have occurred.) Advocate for is, of course, redundant; it also implies the possibility that one would advocate against something, which is clearly impossible.” Indeed, no preposition is needed after the verb advocate , but, as usual, the situation is less obvious than it seems. Language is tremendously redundant at all levels. Redundancy allows it to break through the “noise.” For instance, we understand whispered speech, but what is a vowel or a voiced consonant with the voice turned off? Apparently, the residual information suffices for the message to be processed by the listener. English has lost nearly all endings, but in the languages that have cases and gender distinctions in nouns, adjectives, and sometimes verbs, agreement defines usage. A plural noun will need a plural adjective before or after it (and so forth). This rule is not necessary (compare Engl. good book ~ good books), but it safeguards the sense group from being misunderstood. At the lexical level, language also tries to be redundant. To advocate higher salaries is fine; to advocate for them is “wrong” but may sound more like fight for. Or perhaps the preposition came from the noun: compare a strong advocate for higher salaries.

Over the years, I have collected a small glossary of redundant prepositions and adverbs. In British English, one brushes up one’s French; Americans brush up on their French. The same happens to give up. The idiom give up the ghost preserves the original usage, but Americans tend to give up on things. Many of them have given up smoking but are unwilling to give up on life’s little pleasures. I am perpetually puzzled by the collocation continue on. How else can one continue? Infection can penetrate the lungs but can probably also penetrate into the lungs. I think everybody will prefer penetrate into the thicket but penetrate the problem. And a final remark. “Even on public radio and in print.” Why should journalists be more refined than the rest of the world? That might make them sound and look elitist, the worst sin one can think of. And I would like to repeat what I have said so many times. If “everybody” says something, the usage becomes correct. Swimming against the current is noble, but don’t expect the stream to turn back because of your efforts.

In the same spirit was the wrathful letter condemning the phrase combine together. Indeed, together is redundant. But if we look around, we will notice that many things are said to be joined together. The society of which I happen to be a member states that it is a group of people assembled together (with an explanation of what the purpose of the assembly is). I have several examples of gather together. Are they all wrong?

Aroint.

Can it be related to the Germanic verb for “run” (German rennen, Swedish ränna, etc.)? The meaning of aroint thee would then be run! The line from Macbeth with the word aroint has been the object of numerous conjectures. Years ago, an eminent editor of Shakespeare suggested that Old Engl. rinnan was the etymons of aroint; consequently, our correspondent’s suggestion is not new. To my mind, it has little appeal. All the forms cognate with run have a short vowel, while modern dialectal rynt seems to go back to a diphthong. From the same post I received a question about the Latin phrase dii te averruncent . Dii: pl. of deus “god” (here, “pagan god, devil”), averrunco “deflect, divert” (here, 3rd p. pl. present, subj.); hence “may the devils take you from here.”

Viking.

The word has a long vowel, but what would have happened if it were a borrowing of a noun with a short vowel in the lending language? I think it would then have retained the short vowel, at least at the epoch that did not require lengthening in this position (assuming that it would not have fallen prey to folk etymology).

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Laughing demon by Katsushika Hokusai, 1831. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for February 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Medical apocalypse

When many people hear the word apocalypse, they picture four remorseless horsemen bringing death and destruction during the world’s final days. In fact, the Greeks who introduced the word over 2,000 years ago had no intention of invoking the end times. Instead the word apocalypse, which is composed of the roots for “away” and “cover,” means to pull the cover away, to reveal, and to see hidden things. The idea is not merely that we can bring things shrouded in darkness to light, or make visible what was once invisible. These interpretations imply no prior effort to conceal. With apocalypse, there is a clear connotation that what is unseen has been intentionally hidden.

The contemporary medical field of radiology exhibits both revelatory and apocalyptic features. Anyone who has seen x-ray, ultrasound, CT, or MR images of the human body knows that we now routinely peer inside it without cutting it open. Hundreds of thousands of patients each year, who would once have undergone diagnostic surgeries intended to determine what ails them, can now be evaluated in a non-invasive fashion. For example, it is now possible completely to assess the extent of abdominal trauma patients’ injuries with a CT scan, only operating on the small number whose injuries are associated with severe, ongoing blood loss or the interruption of blood flow to a vital organ.

This ability offers huge benefits to the patient and savings to the healthcare system. Important risks, costs, and downstream effects of surgery can be completely avoided. The patient whose imaging findings don’t indicate surgical therapy and doesn’t undergo an operation is spared risks of anesthesia, infection, and bleeding. While CT scans are expensive compared to doing nothing, they constitute a small fraction of the combined cost of anesthesiologist’s and surgeon’s fees, operating room and recovery room time, and prolonged hospitalization and post-operative recovery. And the patient does not go through life with a surgical scar or increased risk of developing a bowel obstruction.

No one who knows anything about medicine would doubt for a moment that the advent of radiology has completely transformed the way physicians care for patients. In fact, a poll conducted at the turn of the millennium revealed that the two most important medical innovations in the latter half of the 20th century were the introduction of CT and MRI scanning. Nothing was introduced into medicine during that time period without which it would be more difficult to imagine providing top-notch care to patients. Fields such as neurology, neurosurgery, emergency medicine, trauma surgery, and oncology would be almost unrecognizable without such technologies.

What can x-rays, ultrasound, CT, and MRI scanners reveal? The answer is simple yet profound — every one of the most important categories of human disease. Infectious and inflammatory disorders generally demonstrate swelling and increased contrast enhancement, appearing brighter than normal tissues. Traumatic injuries usually appear as loss of blood flow to tissues, associated in some cases with hemorrhage. The same can be said for vascular disorders, such as heart attack or stroke, where the blood flow to vital tissues is interrupted. And cancers generally appear as masses that displace or replace normal tissues in the lung, colon, breast, prostate gland, and so on.

The contributions of medical imaging can be regarded as a form of revelation, illuminating the otherwise invisible inner structure and function of the human body. The only alternative ways to visualize such structures is to insert an endoscope, which makes parts of the body such as the linings of the respiratory and digestive tracts directly visible, or to use a scalpel, which necessarily entails damage to normal tissues. In both cases, some form of anesthesia is generally needed, and there are risks of perforation, bleeding, and infection. Of course, the radiation associated with CT scans entails a tiny theoretical risk of cancer, but MRI and ultrasound involve essentially no health risk.

Does it make sense to consider radiology not merely revelatory but also apocalyptic? In other words, would we be justified in saying that the interior of the human body is not only invisible but actually hidden? There are a number of grounds for answering these questions in the affirmative. One obvious sense concerns the fate of a pre-19th century ancestor whose internal anatomy had become accessible to the eye. Whether a trauma victim or a surgical patient, any person whose brain, heart, or intestines had seen the light of day would likely be dead or dying, and those who weren’t would suffer a very high risk of death from infection over the ensuing days (Figure).

Figure. This young woman was severely injured in a motor vehicle accident. A CT scan image of her abdomen shows that her intestines have herniated out through a wound in the right side of her abdominal wall. This is a relatively rare case, where internal anatomy has become directly visible to the eye. For most of human history, such a wound would have proved fatal, either right away or in the ensuing days, as overwhelming infection developed. Today, however, advanced surgical techniques and antibiotics make it possible for the patient to survive.

From a pre-historical perspective, the exposure of such internal anatomy would necessitate so much destruction of normal tissues, such a large blood loss, and so high a probability of infection that it would be essentially incompatible with life. So far as we know, it was only relatively recently in human history, really only in the last few centuries, that physicians and scientists had gained sufficient knowledge of the structure and function of the human body, as well as the existence of pathogens such as bacteria, to be able to prevent and treat problems such as internal blood loss and bacterial infection. Only by keeping their insides hidden could human beings survive.

Consider also the milieu intérieur, a term coined in the 19th century by the great physiologist Claude Bernard. It refers to the body’s remarkable ability to maintain a relatively stable internal environment in the face of huge swings in external conditions. Summer or winter, gorging or fasting, awake or asleep, we maintain a remarkably consistent internal temperature, blood pH, and glucose concentration, and so on. Bernard and his followers believed that the skin, the linings of our digestive and respiratory tracts, and the immune system play a vital role in maintaining the internal conditions of life. To disrupt such boundaries, for example by a severe burn, is to put the organism at grave risk.

Both nature and man labor to keep the hidden hidden. If the insides are brought into direct contact with the outside, the organism dies. Confronted by a knife-wielding assailant, our impulse to self-preservation provides ample evidence of the depth of the instinct to protect our interior. And this is especially true of our most vital constituents. We naturally make use of less vital parts, such as the arms and legs, to protect the most essential ones, such as our head, neck, and torso. When such inner parts do become directly visible, many people experience a deep, even visceral sense of revulsion, some even becoming nauseous, dizzy, or passing out.

Radiology, then, represents more than a form of revelation. It is apocalyptic, an uncovering of the hidden. As such, it walks a kind of tightrope. On the one hand, it transgresses some of our most deeply seated natural boundaries, revealing what eons of natural selection and millennia of cultural evolution have established as a sanctum sanctorum, off limits to the eyes. Yet it does so in a most remarkable way, making it possible to transgress such boundaries without breaking them down, and for one of the noblest of purposes, to diagnose, stage, treat, and monitor the recurrence of disease. Above all, such transgressions involve not life’s taking but its protection and restoration.

Richard Gunderman, MD PhD, is a Professor of Radiology, Pediatrics, Medical Education, Philosophy, Liberal Arts, and Philanthrophy at Indiana University, Indianapolis, Indiana, and winner of the 2012 Alpha Omega Alpha Robert Glaser Distinguished Teacher Award. He is also the author of X-Ray Vision: The Evolution of Medical Imaging and Its Human Implications.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Medical apocalypse appeared first on OUPblog.

Don’t get taken for a ride: taxis and other “tricky” markets

Have you ever wondered if your car mechanic is charging you too much? Or been worried about taking your laptop to a computer specialist, because that might cost you almost as much as a new computer? Have you ever suspected that your taxi is driving you in circles when you were visiting a tourist destination? For most people the answer to at least one of those questions is a loud “yes”! So, what is it that makes us consumers so vulnerable in these – and other – kinds of situations? The answer is straightforward: it’s all about information.

The above are all examples of so called credence goods markets: the seller has superior information, in other words she knows more than the consumer about the good or service that the latter needs. For instance, when a car mechanic tells me that my brakes need to be replaced, I tend to believe them – who wants to take the risk of driving without functional brakes? To make things worse, consumers are frequently not even ex post able to observe the quality that they have received. Did my mechanic really replace those brakes with new ones? To sum up the problem, we often have to rely on the judgment of an expert who is also the seller of a good or service, and this opens the door to fraud.

The above are all examples of so called credence goods markets: the seller has superior information, in other words she knows more than the consumer about the good or service that the latter needs. For instance, when a car mechanic tells me that my brakes need to be replaced, I tend to believe them – who wants to take the risk of driving without functional brakes? To make things worse, consumers are frequently not even ex post able to observe the quality that they have received. Did my mechanic really replace those brakes with new ones? To sum up the problem, we often have to rely on the judgment of an expert who is also the seller of a good or service, and this opens the door to fraud.

Taxi rides are no different. In an unfamiliar city, the passenger often has no clue (or only a vague idea) about the shortest route to a destination. So it’s in the driver’s interest to increase the fare by taking a longer route. Or, even worse: some drivers charge higher fares than they should, by means of manipulated taximeters or other methods. Most of us have experienced such events, or at least heard of others who have. For instance, I have recently seen news reports on taxi fraud in New York City, Berlin, or a number of other cities such as Prague or Buenos Aires – see the exciting new documentary series on city scams in the National Geographic channel.

This is where our study comes in. Anecdotal stories abound, but our aim was to undertake a systematic investigation into fraud on a real credence good market by means of a field experiment. Our pick was the market for taxi services in Athens, Greece. Five undercover experimenters took 348 taxi rides on 16 different routes throughout the city and, rotating in groups of three, assumed different “information roles”: in the role of a local native passenger, the experimenter entered a taxi and simply asked to be taken to a given destination. In the role of a non-local native passenger, the experimenter would add that he is not familiar with the city and ask if the driver knew the destination. This is a clear signal that the passenger has inferior information, allowing the driver to infer that he can get away with taking a circuitous route to the destination – we refer to this type of fraud as overtreatment. In a third role, that of a foreigner, a passenger would repeat the “non-local” scenario, but in English. This is then a clear indication that the passenger is not only unfamiliar with the city’s roads, but also with the taxi fare system, which is regulated nationwide in Greece! This opens the door to an additional type of fraud through manipulated bills, bogus surcharges and the like. We call this overcharging, because it means that an excessive fare is charged for a given distance.

What did we find? Well, first of all, it’s not a good idea to let the driver know that you don’t know your way about – unless you enjoy being taken for a ride! Our local passengers were hardly ever taken on detours, while the other two roles (non-Athenian Greeks and foreigners) were taken on detours of about double length on average. On top of this, passengers acting as foreigners fell victims to overcharging much more often than native passengers, who presumably know how fares work in the country: about every fifth foreigner ended up paying more than they should for a given ride, while the frequency was around 5% for the other two types of passengers. Hence, we detected a very systematic pattern of fraud, relating to a passenger’s perceived information. In addition to the information dimension we manipulated the passengers’ perceived income in our experiment, alternating their appearance and exact destination and thereby distinguishing between those with high and low perceived income. We did not find strong evidence for an effect of income on fraud, although “rich” passengers did appear to be somewhat more susceptible to detours. The good news is that, notwithstanding the systematic nature of fraudulent behavior, its occurrence is relatively infrequent in Athens. Indeed, the majority of taxi drivers in our sample provided an honest service and charged the correct amount for it.

We can draw some specific lessons from these findings. The obvious implication is that a buyer should convey, if possible, the impression that they are not clueless. For instance, in the case of medical treatments – another prominent credence good – it may be worthwhile mentioning a (fictitious) doctor in the family; or, with car repairs, memorizing and using some technical terms might help, and asking the mechanic to put the replaced parts back in the car’s boot can guard against false charges. For taxi rides, one possibility is to use navigation systems (available in many mobile phones) to verify the optimal route to a destination. In a nutshell, as in many other economic situations, information is the key.

Loukas Balafoutas is Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Finance at the University of Innsbruck. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Edinburgh and has also worked at the OECD Development Centre. His research focuses on the behavioral underpinnings of economic activity and he has used laboratory and field experiments to study behavior in areas such as tournaments, public goods, property rights, corruption, and social norms. He is the co-author, along with Adrian Beck, Rudolf Kerschbamer, and Matthias Sutter, of the paper ‘What drives taxi drivers? A field experiment on fraud in a market for credence goods’ in full and for free in The Review of Economic Studies.

The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. It is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journal, with a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers, and is essential reading for economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Taxi. By Oktay Ortakcioglu, iStockPhoto.

The post Don’t get taken for a ride: taxis and other “tricky” markets appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers