Oxford University Press's Blog, page 971

March 5, 2013

Why I like Ike – sometimes

We are in the midst of a great Dwight Eisenhower revival. Our 34th president, whose tenure once appeared to be little more than a sleepy interlude between the New Deal era and the tumultuous 1960s, is very much in vogue again. The past year has seen the publication of three major new biographies. On 7-8 March, Ike’s presidential legacy and its implications for our own time will be the focus of a conference at Hunter College in New York City.

The renewed interest in Eisenhower owes much to our dissatisfaction with our current politics, especially the partisan polarization that yields stalemate in national politics and prevents action on issues ranging from the long-term deficit and immigration reform to climate change and investments in education. In foreign policy, we recoil from a decade of costly and frustrating military interventions. We see political leaders seeking to break any policy impasse through public rhetoric that has little demonstrable impact on public opinion.

Against this backdrop of frustration, Eisenhower’s record in office looks impressive. Even as conservatives called on Ike to dismantle the New Deal, his administration backed the expansion of Social Security coverage. And while conservatives also demanded that the United States “roll back” communism in Eastern Europe, Eisenhower avoided reckless confrontations with Moscow and Beijing. He brought the Korean War, by then deeply unpopular at home, to a close within months of taking office. Also, despite his pending reelection contest in 1956, he insisted that Israel, Great Britain, and France withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula and the Suez Canal.

Of special note, Eisenhower recorded several important legislative achievements, notwithstanding the fact that the Republican Party controlled both houses of Congress only during his first two years in office. He pushed successfully for the federal interstate highway program that remade America’s built landscape, the first civil rights bill to win congressional approval since Reconstruction, and enhanced science education. It isn’t surprising, then, that pundits and politicians alike get a bit wistful when they consider what Ike did under the umbrella of bipartisanship.

In contrast to the highly visible public leadership favored by presidents in our own time, Eisenhower preferred a low-key style. He realized that sometimes he could be most effective behind the scenes, what political scientist Fred Greenstein aptly terms the “hidden-hand presidency.” One result was that Eisenhower could appear to be reluctant to act, as during the Little Rock school desegregation crisis. But we have seen today that when a president associates himself very visibly with an issue, his support can be toxic, driving away some of those who otherwise share his position.

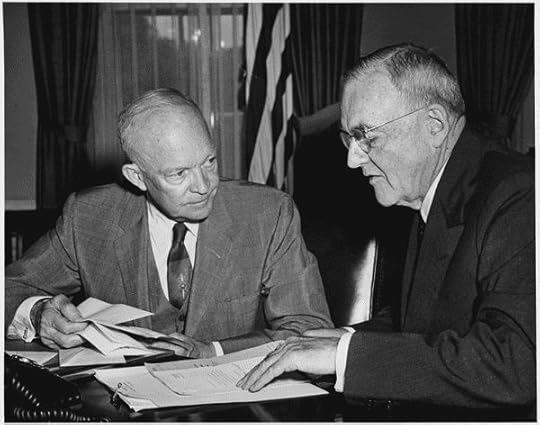

President Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles in 1956. US National Archives and Records Administration.

So there is much to like now about Dwight Eisenhower as a president. That said, we also need to recognize that his record owed a great deal to the circumstances in which he held office. Many of the things he accomplished simply are not possible today.

Let’s start with Ike’s ability to make deals across party lines. Mid-century American politics has been described as a four-party democracy: moderate and liberal Republican internationalists; Republican conservatives; conservative Southern Democrats; and liberal big-city Democrats. From these components, a president and legislative leaders such as Lyndon Johnson could mix and match. The parties overlapped ideologically at the margins, and some lawmakers stood closer to the center of opinion in the other party than in their own. Contrast this with the situation now, where the most conservative Democrat consistently casts more liberal votes than the most liberal Republican.

In fact, if a Dwight Eisenhower had tried to run for president as a Republican in 2012, he would not have secured the nomination. The party has veered too far to the right, and a nominating system that gives so much weight to ideological activists would be especially inhospitable to someone with as many centrist positions as Ike held.

Eisenhower also held office at the peak of America’s relative advantage in the global economy. Europe and Asia had yet to recover from the war’s devastation and American industries enjoyed an enormous competitive edge. So dominant was the American economy in the postwar period that Eisenhower could expand Social Security, establish an interstate highway system that would be largely self-funded through new dedicated revenues, sustain a large peacetime military, and balance the budget. Certainly, he had to make some difficult choices, but they pale next to the trade-offs policy makers face today.

Yes, there is still a lot to like about Ike. His record commands respect. But perhaps the most important thing we can learn is that a president has to work with the material at hand, and some of the ingredients Eisenhower used won’t be found in the political cupboard any more.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. Read Andrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why I like Ike – sometimes appeared first on OUPblog.

A conversation with Chet Raymo on White-crowned Sparrows and other matters

Does the world have a voice? Do particular places have a distinctive vocabulary, grammar, and syntax all their own? Can we learn this language, learn to attune our ears to its music and perhaps in this way come to inhabit the world with more care and feeling? These are not new questions, nor are they original to me. The ancient Stoics had a sense of the Logos or Word as a fiery substance moving through all matter. Early Christians (and Jews before them, although not in quite the same way) spoke also of a Word through whom the world came into being and continued to be sustained. Medieval visionaries such as Hildegard of Bingen have expressed this intuition in terms of a prima vox or “primary voice” whispering through all living things. For Henry David Thoreau, one of the critical tasks for anyone wanting to know the world is learning to attune the ear to the gramática parda or “tawny grammar” arising from the life of wild beings. Similarly, the great French writer Jean Giono spoke of the necessity of becoming sensitive to what he called simply “le chant du monde.”

No, these are not new questions. But they have taken on new meaning and urgency in the present moment as the fabric of world continues to fray and ever-greater numbers of places are at risk of falling silent forever. The need to listen, to learn the language of the world has become one of the urgent moral tasks of our time. But what precisely are we listening to or for? A Voice behind or within the world? The simple eloquence of the world itself? And what of the silence behind and within things? A silence that some have argued is primordial, the sources of all language. How might the contemplative practice of listening contribute to the work of repairing the world?

This, as it turns out, is where Chet Raymo and I recently picked up the thread of a conversation begun many years ago at a small Thai restaurant in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We had been invited to Cambridge in the fall of 2000 by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim (from the Forum on Religion and Ecology) to participate in a conference on “The Ecological Imagination: Nature, Place and Spirituality.” I had read Chet’s work before [Honey from Stone: A Naturalists’s Search for God (Cowley, 1995); Natural Prayers (Ruminator Books, 1999)], but this was my first time meeting him. We hit it off, the scientist and theologian finding common ground in our love of particular places (the Dingle Peninsula) and literatures (the Catholic mystical tradition). And we stayed in touch over the years.

Recently Chet sent me a note to let me know he had been reading The Blue Sapphire of the Mind and had written about it on his “Science Musings” blog. I read his comments and sent him a response, which he also posted on his blog. The debate on the possible relationship between science and religion (or spirituality) has become one of the most fraught areas of our contemporary public discourse, and it seems unlikely that this modest exchange will make any significant difference, especially for those who are convinced that there is little point in even attempting a rapprochement between them. Still, there is something worthwhile in the simple act of listening to another speak of his or her own subjective experiences of and feeling for the natural world. Listening and perhaps offering a response arising out of what may well be a very different kind of experience. I make reference to it here as a gesture toward the possibility of further engagement with these questions by anyone who may wish to take them up.

A note about the place and the context that gave rise to the conversation: I refer in the book to a place called the Sinkyone Wilderness (or Lost Coast), one of wildest and most remote places on the northern California coast, a place where I have spent part of every summer for the past fifteen years. It is there that I became acquainted with the White-crowned Sparrow, a bird common to many parts of the Pacific Coast and whose lilting song I came to associate with the plateau overlooking the Pacific Ocean at the Sinkyone Wilderness. Almost every day I would sit on the gnarled, bleached branches of a fallen eucalyptus tree in the field below our cabin. Sooner or later I would hear the song of that sparrow, sharp, sweet, insistent. It became for me an essential part of the “tawny grammar” of that place. And on the occasions when I wandered up the road to Redwoods Monastery to sit in silence and chant psalms with the members of that community, the song of the sparrow subtly entered into and became part of another, sacred grammar. After a while I had a hard time distinguishing them from one another.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Douglas E. Christie is Professor of Theological Studies, Loyola Marymount University, and the author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology and The Word in the Desert: Scripture and the Quest for Holiness in Early Christian Monasticism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo of the Sinkyone tree by Douglas E. Christie. Used with permission.

The post A conversation with Chet Raymo on White-crowned Sparrows and other matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Stalin’s curse

My interest in the Cold War has developed over many years. In fact, as I look back, I would say that it began around the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis in the early 1960s when I was still in high school. Over the years, as a college student and then as a university professor, I began to look more closely at the vast literature that developed on the topic and to examine the bitter controversies that had raged since 1945. In the process, I stumbled upon several illuminating studies, but there was no one “school” of interpretation that I found satisfying. As with my other books (on Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union), I wanted to find out for myself what really happened, what the Cold War was all about.

Why did I end up focusing on Stalin? He turned out to be the key figure at the epicenter of events when the East-West conflict began. However one might explain the motives behind his actions, it is clearly the case that his initiatives led to the Cold War. Moreover, by the time he died in March 1953, he had helped to create the communist world that seemed impervious to change, as well as the terms of engagement with the West. These configurations were all but frozen in place.

Where to begin an account of this fateful turn of events? I found that it is misleading at best to make a division, as we often do, between the end of the Second World War in May 1945 and the post-war period. Not only did the mayhem continue after VE-Day, but massive violence in the name of the communist cause occurred simultaneously with the years of the conflict against Nazism and spilled over into the post-war. There were savage retributions, multiple ethnic cleansing operations, and civil wars, which became entangled in the establishment of new communist regimes in Eastern Europe. Similarly in Asia, there is a seamless web of connections from the war against Japan to the Cold War.

As far back as August 1939, the Soviet Union, as Hitler’s ally, had begun to renew its mission, on hold since the early 1920s, to extend the communist Red Empire. According to Stalin, Hitler was unknowingly playing a revolutionary role by destroying old regimes and ruling classes. The Nazi invasion of the USSR in mid-1941 represented a setback, but Stalin still perceived possibilities for advancing the cause even when the capitalist British and Americans came forward with offers to help. What is remarkable is that his faith in the inevitability of world-wide communist revolutions never diminished. He was the master of disguise. When he spoke with his accidental allies he neither used the language of the Communist revolutionary, nor whispered of any aims for the post-war besides guarantees for the future security of the USSR. Who could argue with that?

Privately, Stalin never wavered in his hatred for all the capitalist countries, be they German, Japanese, British, or American. His strong immediate preference was to milk the wartime alliance for all it was worth. Yet he was always prepared to go over to the offensive for the Red cause, or to encourage others to do so. As he put it succinctly to Yugoslav comrades in 1948: “You strike when you can win, and avoid the battle when you cannot. We will join the fight when conditions favor us and not when they favor the enemy.”

The story that unfolded between the beginning of the Second World War and Stalin’s death exactly sixty years ago in 1953, is gripping, momentous, and tragic. The once seemingly impregnable Red Empire that he, along with millions of true believers, had created began to dissolve in 1989 and the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist in 1991. Although they all bristled with armies and their secret police forces were larger than ever, they barely fired a shot. It was as if there was nothing left to defend.

Now that the dust has settled, it turns out that political cultures, authoritarian traditions, and command economies do not change as quickly as regimes. So the nations over which Stalin and his disciples ruled for so long still carry the telltale signs of his curse. These include a penchant to tolerate a strongman at the top, fragile regard for the individual, and stunted civil societies. Although people will have to struggle for years to overcome these deficits, the indications are, in spite of setbacks, that they will succeed.

Robert Gellately is Earl Ray Beck Professor of History at Florida State University. His publications have been translated into over twenty languages and include the widely acclaimed Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: the Age of Social Catastrophe (2007), Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 (2001), and The Gestapo and German Society: Enforcing Racial Policy, 1933-1945 (1990). His most recent work is Stalin’s Curse: Battling for Communism in War and Cold War.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Yalta summit in February 1945. Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Stalin’s curse appeared first on OUPblog.

The Beatles record “From Me to You,” Tuesday 5 March 1963

With Northern Songs (their publishing company) established, the Beatles needed a song for their next single and, flushed with the success of “Please Please Me” and the emerging ecstasy at their performances, they again brought together elements from different songs in their repertoire to create something new and fresh. George Martin scheduled a recording session for Tuesday 5 March, towards the end of their first national tour when they served as a warm-up act to British singer Helen Shapiro. On the Thursday (28 February 1963) before the recording session, as the bus barreled through the cold from York to Shrewsbury and as the tour began its final zigzag retreat towards London, Lennon and McCartney put their heads together to create something they could record.

Fifty years ago, setting up in studio two was beginning to feel comfortable to Paul McCartney: not as familiar as the Cavern Club in Liverpool perhaps, but comfortable. The carpets on the parquet floor, the high ceiling, the wood paneled stairs and doors, the movable acoustic panels, and the quilted drapes of damping cloth gave the room a warm if institutional library feel, complemented by the professorial air George Martin brought to their meetings. Their ordeal on 11 February recording the remaining tracks for their first album had served a cathartic function, transforming them from ambitious amateurs into professionals. With a hit record, they now returned with confidence and a growing sense of authority.

Fifty years ago, setting up in studio two was beginning to feel comfortable to Paul McCartney: not as familiar as the Cavern Club in Liverpool perhaps, but comfortable. The carpets on the parquet floor, the high ceiling, the wood paneled stairs and doors, the movable acoustic panels, and the quilted drapes of damping cloth gave the room a warm if institutional library feel, complemented by the professorial air George Martin brought to their meetings. Their ordeal on 11 February recording the remaining tracks for their first album had served a cathartic function, transforming them from ambitious amateurs into professionals. With a hit record, they now returned with confidence and a growing sense of authority.

They had prepared songs for the session, including the most likely candidates for their next single, “From Me to You,” “Thank You Girl,” and “The One after 909.” We cannot know how much time they had been able to rehearse before they arrived; but the rigors of touring left little opportunity for practice, especially now that they squeezed in radio appearances as well. Indeed, they had only written the core of “From Me to You” a few days before this session. We know that they commonly ran through the material in advance of the tape rolling, such that takes one and two of “From Me to You” show most of the principal elements already in place.

McCartney has commented that he and Lennon would introduce a song to the group and Martin, and would work out the basics such as chords, melody, meter and rhythm, at which point each musician would retire separately for a brief period before returning to try performing the song. Apart from some occasionally ragged singing, the early takes sound reasonably prepared and over the course of seven attempts at a suitable track, they would increase the tempo, alter lyrics and form, and generally smooth out their performance. Sometimes, they chided each other on missing endings, chord changes, and other details, but the atmosphere remained positive and constructive.

Lennon and McCartney would already have rehearsed vocal parts as they created the song so that in “From Me to You,” they differentiated the two statements of the chorus (the first in unison, the second in two-part harmony). With take one, however, they also left room for something they would overdub later. That is, they were already anticipating how to use the studio creatively. George Martin likely functioned as an educator in this process, telling them how they might approach making the recording, and the Beatles would be good students.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The recordings also reveal that the Beatles performed live in the studio. That is, rather than recording an instrumental backing track and then adding the vocals, they sang and played simultaneously as though on stage. British performers and production crews understood this approach as the norm in the early sixties, although by the end of the decade, technology would allow and encourage asynchronous recording where musicians no longer interacted in real time with other performers in the studio.

McCartney functioned very much as a music director, counting in every take as he and Lennon faced each other to sing into different sides of the same Neumann microphone, balancing the relationship between melody and harmony by ear. They had no opportunity to sing the parts separately and have engineer Norman Smith balance them afterwards. Over the course of the first four attempts at a suitable performance, they slightly increased the tempo and brought the details more closely into focus. Still, they sensed room for improvement: the band continued to search for a satisfactory performance, correcting as they played.

The repetitiveness of the text leads to problems with the second verse, in which they repeatedly have difficulty remembering to sing “so call on me…” instead of “just call on me.” To create variation to the short performance, in take five they added half an empty verse followed by the refrain just before the second chorus, clearly indicating the intention to overdub material. By take seven, they had a solid basis upon which to work. Playing back take seven, they now added harmonica over Harrison’s electric guitar and when they came to the inserted verse, the electric guitar, harmonica, and even the bass all doubled the melody. Nevertheless, Martin wanted more options, so they recorded multiple edit pieces, including the introduction, an inserted verse, and the coda that the artist-and-repertoire manager could cut (literally, with a pair of brass scissors) and then splice with adhesive tape to replace part of the original recorded performance.

Click here to view the embedded video.

With this recording, the production team and the band firmly moved into the realm of creating works that could exist only in a magnetic environment before being cut to disc. Although they recorded parts of “From Me to You” live in the studio, the end recordings (the mono and stereo versions are different) are the products of George Martin and Norman Smith editing the material together after the band had packed their equipment and left. Thus, in its way, “From Me to You” portends the magnetic revolution in which the Beatles were to be major players in the coming decade.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cover art for “From Me to You” by The Beatles used for the purposes of illustration via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Beatles record “From Me to You,” Tuesday 5 March 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

Patsy Cline… 50 years on

On 5 March 1963, a plane flying over Tennessee encountered inclement weather and crashed. On board were country musicians Randy Hughes, Cowboy Copas, Hawkshaw Hawkins, and Patsy Cline. A star of both country and popular music, Cline is remembered as one of the greatest American singers of the 20th century. The following is an extract from The Encyclopedia of Country Music entry on Patsy Cline by Margaret Jones.

Popular in her time, Patsy Cline has achieved iconic status since her tragic death at age thirty in 1963. Cline is invariably invoked as a standard for female vocalists, and she has inspired scores of singers, including k. d. lang, Loretta Lynn, Reba McEntire, Linda Ronstadt, Trisha Yearwood, and Wynonna. Her unique, crying style and impeccable vocals have established her reputation as the quintessential torch singer.

Cline’s short life reads like the heart-torn lyrics of many of the ballads she recorded. Born Virginia Patterson Hensley in Winchester, Virginia, in the midst of the Depression, she demonstrated musical proclivity at an early age—a talent inherited from her father, an accomplished amateur singer.

By age twenty Cline connected with local country bandleader Bill Peer, an association that intensified her desire for country music stardom. She adopted the name Patsy after her middle name, Patterson, and possibly in a nod to singer Patsy Montana, whose feisty cowgirl persona anticipated both Cline’s spunk and early stage costuming. Cline married her first husband, Gerald Cline, on March 7, 1953, but she found the relationship unfulfilling, and they divorced four years later.

During this period Cline made inroads into the thriving Washington, D.C., country music scene, masterminded by country music’s “media magician,” Connie B. Gay. Beginning in the fall of 1954, Gay spotlighted Cline as a soloist on his Town & Country TV broadcasts, which included Jimmy Dean as host, Roy Clark, George Hamilton IV, Billy Grammer, Dale Turner, and Mary Klick. Through her Washington connections Cline landed her first recording contract in September 1954, with Bill McCall’s Pasadena, California–based Four Star Records, an association that lasted six years and became the single greatest hindrance to her career. Cline alleged that McCall swindled her out of royalties and gave her substandard material to record. Cline’s debut single, the country weeper “A Church, a Courtroom and Then Goodbye,” sold poorly when released in July 1955 on the Decca label’s Coral subsidiary (by lease arrangement between McCall and Decca A&R man Paul Cohen). Cohen turned production over to his protégé and eventual successor, Owen Bradley, who became Cline’s guiding light for the duration of her recording career.

Cline’s first four singles flopped, but the “hillbilly with oomph” act she developed on TV and in personal appearances earned her regional fame. Her recording stalemate ended when she made her national TV debut on the Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts show on January 21, 1957, singing “Walkin’ After Midnight,” which hit #2 country and #12 pop. Cline rode high on the hit for the next year, working show dates and performing regularly on Godfrey’s weekly CBS broadcast Arthur Godfrey and Friends and on ABC’s Country Music Jubilee, but there were no follow-up hits. Her September 1957 marriage to second husband Charlie Dick resulted in a tumultuous relationship glamorized in Sweet Dreams, the 1985 biographical film starring Jessica Lange as Cline. By the end of 1957 Cline had retreated into semi-retirement.

After giving birth to a daughter (Julia) in August 1958, Cline moved to Nashville and signed with manager Randy Hughes, who attempted to revive her career by booking one-nighters across the country and helping her ride out her Four Star contract. Back to working $50 gigs, she was at her nadir when the Grand Ole Opry belatedly made her a member on January 9, 1960. That summer she signed with Decca, and Bradley directed her toward becoming a leading exponent of the emergent Nashville Sound beginning with her recording of the Harlan Howard–Hank Cochran song “I Fall to Pieces.” Cline initially resisted Bradley’s lush arrangements, which featured backings by the Jordanaires, but ultimately accepted his guidance.

Cline gave birth to a son (Randy) in January 1961 and survived a near-fatal car accident in June as “Pieces” slowly started its climb up the charts, reaching #1 country in August and peaking at #12 in Billdoard’s pop rankings. Cline maintained her chart momentum with the crossover hits “Crazy” and “She’s Got You” and with albums such as Patsy Cline Showcase and Sentimentally Yours. Other highlights included appearances at Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl and on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Cline joined The Johnny Cash Show as the touring group’s star female vocalist in January 1962, and over the next fourteen months she played numerous dates with Cash’s “family,” which included Don Gibson, George Jones, Carl Perkins, June Carter, Barbara Mandrell, Gordon Terry, and Johnny Western.

Cline related premonitions of her death to close friends Loretta Lynn, Dottie West, and June Carter as early as September 1962. Her last public performance was a benefit in Kansas City, March 3, 1963. Returning home, she was killed in a plane crash that also took the lives of pilot Randy Hughes and fellow Opry stars Cowboy Copas and Hawkshaw Hawkins. Cline’s singles “Leavin’ on Your Mind,” “Sweet Dreams (Of You),” and “Faded Love” charted Top Ten after she died. Numerous new or reissue recordings have appeared since her death, and she has remained one of the MCA label’s most consistent sellers. The subject of both Sweet Dreams and the hit 1990s play Always… Patsy Cline, she was elected to The Country Music Hall of Fame in 1973.

Immediately upon publication in 1998, the Encyclopedia of Country Music became a much-loved reference source, prized for the wealth of information it contained on that most American of musical genres. Countless fans have used it as the source for answers to questions about everything from country’s first commercially successful recording, to the genre’s pioneering music videos, to what conjunto music is. This thoroughly revised new edition includes more than 1,200 A-Z entries covering nine decades of history and artistry, from the Carter Family recordings of the 1920s to the reign of Taylor Swift in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Compiled by a team of experts at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, the encyclopedia has been brought completely up-to-date, with new entries on the artists who have profoundly influenced country music in recent years, such as the Dixie Chicks and Keith Urban.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Patsy Cline… 50 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

March 4, 2013

For stronger gun control laws; against the divestiture of gun stocks

By Edward Zelinsky

Even before the events in Newtown, I supported the strengthening of gun control laws. Advocates of gun rights correctly assert the need for better enforcement of existing laws as well as the urgency of confronting the violent nature of our culture. But General McChrystal is also correct. There is no compelling reason for civilians to own or possess high capacity weaponry designed for military missions.

The case against the divestiture by public pension plans of the stocks of gun manufacturers is as strong as the case for stronger gun control laws. Such divestitures have been undertaken by public pension plans in New York City, Chicago, and California. If individuals want to avoid gun stocks in their personal investments (including their own IRAs and self-directed 401(k) accounts), they have every right to do so. However, pension fiduciaries are not investing their own money. Such fiduciaries should not use the funds under their control to pursue political agendas — even political agendas with which I agree.

For public pension fiduciaries to divest gun stocks is both futile and troubling. In a competitive market, such divestiture is an economically meaningless gesture. When the New York, Chicago, and California pension plans sold gun stocks, someone else bought them. The net result was an ineffectual game of musical chairs which simply shifted the ownership of these gun stocks from one owner to another.

Moreover, there is no principled limit once political criteria are introduced into the investment of public pension funds. If pension trustees should divest the stocks of gun manufacturers to advance a political agenda, why don’t they also divest the stocks of companies that make the unhealthy foods that New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg correctly identifies as a severe public health problem? Or why do they not sell the stock of the media and software companies which make violent movies and video games?

To avoid this slippery slope, fiduciary law declares that pension funds should be invested, not to further anyone’s social agenda but to exclusively benefit the financial capacity of pension plans to fund the retirement payments they owe. The exclusive benefit rule, as it has become known, precludes the fiduciaries of pension plans from pursuing objectives which, no matter how worthy, divert pension resources from the mission of providing retirement income. Once that diversion starts, there is no convincing place for it to stop.

Many public pension plans confront serious problems including underfunding unrealistic rate of return assumptions and the ongoing retirement of the Baby Boomer workforce, that will stress such plans in unprecedented numbers. In this challenging environment, the exclusive benefit rule serves the salutary purpose of assuring that pension funds are invested with a single-minded focus on producing economic returns. Pension plans should not pursue social agendas which, however worthy, are irrelevant to pensions’ mission of providing retirement benefits.

Our elected officials should push for additional laws to control gun violence and for stronger enforcement of existing laws. The executives of media and software companies should act responsibly to reduce the violent nature of their products. But pension trustees should not divest gun stocks to further the gun control agenda.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: New York Stock Exchange. Photo by Elbie Ancona, 12 August 2010. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post For stronger gun control laws; against the divestiture of gun stocks appeared first on OUPblog.

My favorite insult

When friends heard that I was working on a book on insults, I typically had some explaining to do: “It is not a book of insults; it is a book about insults and the role they play in human society.”

They would go on to ask whether, in my research, I had come across any good insults. Indeed I had. In the process of doing research, I had not only read every insult anthology I could get my hands on but categorized the insults I found there, the way an entomologist might spend time collecting and categorizing beetles.

And what, they would ask, was my favorite insult? I would explain that I didn’t have a favorite—not if by favorite they meant an insult that I liked better than the others. This is because I disliked them all! Indeed, in my book I argue that the world would be a better place if we could curb our insulting tendencies. But having made this point, I admitted that there were some insults that I found particularly interesting because of the cunning manner in which they inflicted harm on their target. In particular, I was intrigued by secondhand insults.

To understand how these insults work, it is first necessary to understand behind-the-back insults. If Al makes disparaging remarks to Bob about Charlie, who isn’t present, Al will have insulted Charlie behind his back. By doing this, Al might be able to hurt Charlie’s social standing, without Charlie knowing about the insult and therefore without the danger that he will retaliate.

To understand how these insults work, it is first necessary to understand behind-the-back insults. If Al makes disparaging remarks to Bob about Charlie, who isn’t present, Al will have insulted Charlie behind his back. By doing this, Al might be able to hurt Charlie’s social standing, without Charlie knowing about the insult and therefore without the danger that he will retaliate.

Bob can react to Al’s attack on Charlie in a number of ways. He might join in the attack. He might chastize Al for attacking Charlie. Or he might instead react to Al’s attack by telling Charlie what Al has been saying. Bob’s motives for doing this might be laudable: he might want Charlie to know what is going on so he can defend himself against Al’s attacks. Alternatively, he might report the insult simply because he knows Charlie will be upset to hear about it.

Reporting the insult allows Bob, in effect, to insult Charlie without himself being the author of that insult. Furthermore, if asked why he passed on the insult, Bob can defend himself by claiming to have had Charlie’s best interests in mind: he needed to know what was being said about him! His insult, in other words, will have what CIA operatives call plausible deniability. Charlie’s day will be ruined, but it will be Al, not Bob, who is ultimately to blame. This is a textbook example of what I call a secondhand insult.

There are even more subtle ways to inflict these insults. Suppose Diane invites Elsie but not Frances to a party. Suppose Elsie, on the following day, calls Frances to ask why she wasn’t at the party, and suppose she makes this call not because she wants to know why Elsie was missing: she already knows that Elsie wasn’t there because she hadn’t been invited! Then why make the call? So Frances will know that she hadn’t been invited and thereby experience the pain of having been slighted. This behavior sounds catty, but such things do happen.

Secondhand insults interest me because they show just how ingenious people can be in their use of insults as a means for raising their position on the social hierarchy. If only this ingenuity could instead be used for the good of mankind! More generally, one of the best ways to immunize ourselves to the insults that others might inflict on us is to withdraw from the social-hierarchy game.

For one last example of a secondhand insult, allow me to quote entertainer Oscar Levant. When asked whether he ever read bad reviews of his performances, he replied that he didn’t have to, inasmuch as “my best friends invariably tell me about them.”

William B. Irvine is professor of philosophy at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of A Slap in the Face: Why Insults Hurt — and Why They Shouldn’t, and before that of A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature and language articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: High school class series photo by sjlocke, iStockphoto.

The post My favorite insult appeared first on OUPblog.

Port and border security

By Andrew Staniforth

In direct response to the increased post-9/11 terrorist threat from al Qa’ida, the British government appointed Lord Carlile of Berriew CBE QC as Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (IRTL) during 2001. In more than nine years as Independent Reviewer, Lord Carlile spent a considerable proportion of his time on ports and border security. This was perhaps a mundane part of the Reviewer’s routine, but its importance struck him very quickly. As he stood behind Special Branch officers at UK airports he realised how many extremely speedy judgements fall upon them, with a complex body of intelligence and law sitting on their shoulders. He also observed the questioning of passengers and stated that:

“I came to understand the intrusion faced by almost always innocent passengers, but the critical importance of the national security framework in which we all travel. In sea ports and on ferries, I became conscious of the porous and fragile nature of our border controls. At huge freight terminals, I saw the opportunities for terrorist and other seriously criminal acts with the potential for irreparable public damage, and the subtlety required to meet those challenges in a proportionate as well as strictly lawful fashion.”

As part of a series of protective measures in 2007, Prime Minister Gordon Brown asked Lord West, then Minister for Homeland Security and Counter-Terrorism, to conduct a review of UK security specifically focusing upon the protection of strategic infrastructure, stations, ports and airports, and other crowded places. There were three key findings from the review which included;

A need for a new ‘risk-based’ strategic framework to reduce vulnerability of crowded places;

Focused effort on reducing the vulnerability of the highest risk crowded places by working with private and public sector partners at a local level;

New efforts to ‘design in’ counter terrorism security measures are needed, building on good practice from crime prevention.

The recommendations from Lord West’s review were accepted by the Prime Minister and their full implementation continues to be a work in progress for UK port and border security authorities. These security measures quite rightly focused upon the determined threat from contemporary international terrorists wishing to expose and exploit vulnerabilities in border security. Yet there are numerous hazards for ports practitioners to counter which directly impact upon national security, the most pressing being the threats from serious and organized crime. Globally, the United Nations estimates that the most powerful international organized crime syndicates each accumulate in the region of $1.5 billion a year. The international drugs market alone is estimated to be worth £200 billion and the UK’s National Security Strategy also notes that cyber crime has been estimated to cost up to $1 trillion per year globally.

While the laundering of criminal cash and the importation of drugs are key challenges for security forces engaged in the protection of ports and borders, the trafficking of human beings remains a primary concern to government’s and is a serious crime which demeans the value of human life. Human trafficking, the acquisition of people through the use of force, coercion, deception, through debt bondage or other means with the aim of exploiting them. Men, women and children can fall into the hands of traffickers either in their own countries or abroad. Trafficking occurs both across borders and within a country; it is not always visible — exploitative situations are frequently covert and not easily detectable and include the exploitation for prostitution, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or removal of organs. Sadly, children are amongst the most vulnerable victims of this increasingly organised crime. Sometimes they are sold by family members or families are in debt bondage to traffickers and their children are put into forced labour or domestic work where they are vulnerable to sexual or physical abuse. Children may be abducted, or handed over by their parents in the belief that they may have a better life and access to education. Children are also vulnerable to being used in criminal enterprises, working in cannabis farms or pick-pocketing gangs. Some are unaccompanied asylum-seeking children who can be preyed upon by those who exploit them to enable others to acquire state benefits. Security forces at ports continue to tackle human trafficking through prevention and disruption mechanisms achieved by dismantling criminal networks, constructing robust prosecution cases, and confiscating assets which are the proceeds of crime.

The diverse range of security challenges encountered at borders requires a dedicated and determined response, however, the passage through ports security screening also provides significant opportunities for authorities to lawfully gather intelligence and evidence. The increasingly commercialised and economically driven focus of ports of entry provides a challenging environment for law enforcement and intelligence agency practitioners to operate and all in authority must never forget that the safety of the travelling public and the wider security of its citizens must continue to take precedence at all times. The development of a strong, united, and resilient border with agencies, businesses, and governments working together shall ensure increased security for all. New threats shall no doubt emerge in future and those intent upon defeating security measures at borders will continue to create new and innovative solutions to carry out their unlawful activities. The protection of UK borders continues to remain our first and last line of national security defence.

Andrew Staniforth, Detective Inspector, North East Counter Terrorism Unit and Senior Research Fellow, Centre of excellence for terrorism, resilience, intelligence and organised crime research (CENTRIC). He is the author of Blackstone’s Handbook of Ports & Border Security with the Police National Legal Database (PNLD) and consultant editors Clive Walker and Stuart Osbourne QPM.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Port and border security appeared first on OUPblog.

An Oxford guide to women’s history: quiz

Did you know that March is Women’s History Month? In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography you’ll currently find biographies of 6340 women who’ve shaped British history and culture between the 1st and 21st century — making it one of the most extensive accounts of women’s contribution to national life. Viewed in the round, the Dictionary’s coverage reflects changing experiences and opportunities across 2000 years of British history.

Who are these women? First, of course, there are many whose historical importance derived from their inherited social status. Fittingly, the ODNB’s earliest women subjects — Boudicca and Cartimandua — were 1st-century queens of the Iceni and Brigantes respectively. They are followed by a further 500 queens, consorts, and members of royal families, culminating with ‘modern’ royals such as Diana, princess of Wales.

Then there are the pioneers: the first woman to be elected to the House of Commons, for example, or the first to sit in the chamber; the first woman to hold public office in the UK, or the first to practice as a barrister. As well as embodying change, many of these women were also campaigners for equality in the franchise, professional opportunities, and civil liberties. The Oxford DNB includes biographies of more than 350 women who are principally remembered as campaigners for women’s rights. Though the earliest date from the 1700s (most notably, Mary Wollstonecraft), the greatest number were associated with late 19th and early 20th-century networks — of which the ‘suffragists’ and ‘suffragettes’ are the best known. They include leaders such as Millicent Garratt Fawcett and Emmeline Pankhurst, as well as activists like the Manchester campaigner, Flora Dummond, or the ‘suffragette martyr’, Emily Wilding Davison, the centenary of whose death will be marked this June.

Twentieth-century reforms created new opportunities that are also reflected in the Oxford DNB’s coverage of women in the modern period. Most eighteenth-century women in the ODNB are included for their contribution to literature, education, religious practice or the stage. However, by the mid-twentieth century the picture was changing, albeit gradually. Though the arts remain important, a significant—and ever growing—number of women now gain their place in the ODNB as national leaders in science, medicine, the law, and business. In these four fields the Dictionary offers biographies of nearly 500 women active in post-war Britain, from the crystallographer and Nobel laureate, Dorothy Hodgkin, to the Body Shop founder Anita Roddick.

Many of these women are familiar names you’d expect to find in the Oxford DNB. But there’s another kind of ODNB biography that’s also worth mentioning. In recent years, women’s history has developed to concentrate as much on shared experiences as remarkable individuals. The ODNB’s coverage has likewise shifted to reflect these new interests and to provide first-time biographies of women who, until recently, were often missing from the historical record. Recently added biographies of this kind include Agnes Cowper whose ordeal as vagrant in seventeenth-century London provides a remarkable insight into the everyday experience of labouring women, now drawn on by social historians. Or Gwyneth Bebb (1889-1921), one of the first campaigners for women’s participation in the legal profession who, until recently, had been all but forgotten due to her early death in childbirth—months before she was due to become the first woman called to the English bar. Not all ‘rediscovered’ biographies are those lived on the social margins or dedicated to progressive reform, of course. Two days after International Women’s Day, Britain will mark Mothering Sunday. Seemingly a long-established tradition, Mothering Sunday is, in fact, a 20th-century recreation, devised and promoted by a Nottingham clerical worker, Constance Penswick Smith — one of the newest additions to the Oxford DNB.

In addition to the biographies above, the lives of Diana, princess of Wales; the political pioneers Constance Markiewicz and Nancy Astor; the suffragette Emily Wilding Davison; the businesswoman Anita Roddick; and Constance Penswick Smith, reviver of Mothering Sunday, are also available as episodes in the Oxford DNB’s free biography podcast series.

To celebrate Women’s History Month, it’s now time for a quiz…

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. In addition to 58,500 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 175 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men & women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. The American National Biography is the first biographical resource of this scope to be published in more than sixty years.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An Oxford guide to women’s history: quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

March 3, 2013

The KKK in North Carolina

How can mainstream institutions and ideals subsume organized racism and political extremism? Why did the United Klans of America (UKA) once flourish in the Tar Heel state? From lax policing to a lack of mainstream outlets for segregationist resistance, a variety of factors led to the creation of one of the strongest and most complex Ku Klux Klan (KKK) groups in America — and a dramatic conservative shift in North Carolina. We sat down with David Cunningham, author of Klansville, U.S.A., to discuss the rise and fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan.

Why was the KKK so popular in North Carolina?

Two factors were important. First, the state’s klan leadership — and in particular its top officer, “Grand Dragon” Bob Jones — had the ingenuity and capacity to mount massive rallies every night in the state. Hundreds — and sometimes thousands — of spectators would come out, buy refreshments and souvenirs, listen to live music from the KKK’s house band Skeeter Bob and the Country Pals, hear a full slate of klan orators, and watch the climactic burning of a 60 or 70 foot high cross. This skewed county fair atmosphere was compelling theater, and a highly effective recruiting tool.

The United Klans of America printed 2000 of these flyers for each rally. Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The second factor related to the flipside of North Carolina’s pronounced moderation with civil rights. In places like Mississippi or Alabama, committed segregationists could count on militant support from a full spectrum of state and local officials — from governors on down to school boards — and the KKK therefore had a narrow appeal, primarily among those who believed that violence was the only answer to civil rights challenges. In North Carolina, where political officials were clear that they didn’t agree with civil rights reforms but would abide by federal law, the klan became the primary conduit for those who sought to defiantly maintain segregation. This meant that, while the group certainly attracted its share of violent members, it also appealed to those who sought out a civic outlet that insulated them from changes to the racial order.

What led to the KKK’s abrupt and rapid decline in the late 1960s?

While the declining fortunes of Jim Crow-style segregation made the klan’s efforts seem increasingly futile and anachronistic, the fall of the civil rights-era KKK was predominantly a policing story. In North Carolina, state officials had always spoken out against the klan but hadn’t ever engaged in actions that would proactively hinder the group’s efforts to organize and terrorize its enemies. When a congressional committee held hearings on the KKK in late 1965, the state’s status as “Klansville U.S.A.” was splashed across the national headlines. This led to an about-face in North Carolina’s policing efforts. The Governor appointed an “anti-klan” committee to strategize about how to solve its KKK problem, and soon after state police began arresting klansmen on violations large and small, court injunctions prevented the klan from holding rallies in many communities, judges began sentencing klansmen for infractions that would have been ignored earlier in the decade, and both the state police and FBI began more aggressively deploying informants to create infighting within klan units that sapped the group of its resource base. While the press emphasized how disgruntled KKK members were abandoning a laughably crude and irrelevant organization, in truth the Carolina Klan was a sophisticated outfit whose momentum was halted only by an equally dedicated and coordinated anti-klan policing campaign.

What does the KKK’s history tell us about the civil rights movement?

Fifty years ago, while Dr. King was delivering his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the Mall in Washington, DC, the KKK was barnstorming around North Carolina, holding its first rallies and attracting two or three thousand spectators each night to protest the rising civil rights tide. When King came to Raleigh, the state’s capital, three years later, a thousand robed klansmen gathered to protest his speech. Talking to reporters afterward, he asked how the state that prided itself as the most liberal in the South could also have the largest KKK. We know that the Civil Rights Movement story remains important, and this is a key component of it — part of the mosaic that continues to shape race relations in the United States today.

What was it like talking to these former KKK members as you researched your book?

These conversations ran the gamut, from unreconstructed defenses of the klan’s mission, to strong rejections of the KKK’s principles, to nostalgic reminiscences about the camaraderie and “good fun” that members enjoyed. Two interviews in particular stand out. The first was with Robert Shelton, who as the United Klans of America’s “Imperial Wizard” was the most influential KKK leader of the era. Shelton had been put out of the KKK business by a landmark Southern Poverty Law Center lawsuit in the 1980s, and by the early 2000’s had adopted a Burger King near his Alabama home as a sort of ad hoc headquarters for him and “his boys.” He agreed to meet me there, and arrived in a big powder-blue Lincoln Town Car with a defiant “Never” license plate displayed in front. He bragged about working out a deal with the manager for cheap coffee in return for keeping the restaurant full. The disjuncture between his persona and the setting, I think, says a lot about the klan’s declining fortunes since the 1960s.

Another interesting interview was with George Dorsett, the Carolina Klan’s most popular and fiery speaker in the 1960s. Late in his life, both his charisma and his stridency remained evident as he regaled me with Biblical justifications for racial separation. He also told me about his work as an FBI informant throughout much of his klan tenure. I had previously seen documentation of his recruitment by the Bureau, and also had learned about his partnership-of-sorts with his local handling agent. But what struck me was his retrospective view that the FBI was working for him, which isn’t entirely inaccurate if you consider how he was able to protect his role as the KKK’s most successful fundraiser while on the Bureau’s payroll.

What is the KKK’s legacy today?

In my view, the KKK continues to embody two opposing realities. The first relates to the tragic continuities associated with klan activity in the South. My colleague Rory McVeigh and I have found that communities where the KKK was active fifty years ago continue to this day to have significantly higher rates of violent crime than places where the klan never established a foothold. That sustained culture of violence is one aspect of the legacy of organized and sanctioned vigilantism. But the KKK’s trajectory also epitomizes the great changes that have occurred in the South and our nation since the 1960s. In the 2008 election, Barack Obama became the first Democratic presidential candidate in more than three decades to win North Carolina. From Klansville, U.S.A. to the state that cemented the election of our first African-American president, all in less than fifty years — a remarkable transformation indeed!

David Cunningham is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and the Social Justice & Social Policy Program at Brandeis University. Over the past decade, he has worked with the Greensboro (N.C.) Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the Mississippi Truth Project, and served as a consulting expert in several court cases. The author of Klansville, U.S.A.: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-Era Ku Klux Klan, his current research focuses on the causes, consequences, and legacy of racial violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The KKK in North Carolina appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers