Oxford University Press's Blog, page 962

April 1, 2013

IRS boondoggles: Star Trek videos and reasonable compensation cases

By Edward Zelinsky

Many Americans have seen the now-infamous Star Trek video made by the IRS with taxpayer funds. It is painful to watch. Captain Kirk (known in the 21st century as William Shatner) pronounced himself “appalled at the utter waste of U.S. tax dollars.” The video’s dialogue is depressingly sophomoric. The acting talents of the IRS employees are comparable to the acting talents of law professors, that is to say, nonexistent.

Click here to view the embedded video.

But this video is not the worst IRS boondoggle to recently come to light. That award goes to the IRS for spending public resources to litigate K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc. v. Commissioner.

This was a reasonable compensation case, so-called because the IRS attacked the reasonability and therefore the tax deductibility of the salaries paid to employees of a closely-held corporation. The IRS never contests as unreasonable the multi-million dollar salaries routinely paid by publicly-traded corporations to failed and ethically-challenged executives. What the IRS deems unreasonable are the far smaller salaries paid to the hard-working and successful owners of closely-held corporations.

The facts of K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc. are typical of these reasonable compensation cases: a successful, family-owned corporation paid salaries on the order of $981,728 to the corporation’s sole shareholder and $215,000 to his wife. These individuals paid federal income taxes on these salaries. The IRS’s goal (which it achieved) was to get a second, corporate tax on part of these amounts on the theory that these salaries were unreasonable and therefore not fully deductible for corporate income tax purposes.

The salaries paid in K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc. constitute a lot of money for most of us. But these salaries are pocket change for the Masters of the Universe who control our major publicly-traded corporations. Many of these executives are competent, ethical individuals who earn their pay honorably. But others are not.

Why does the IRS challenge the compensation paid to the owner in K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc. as unreasonable but not the millions paid to Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase? Perhaps because Mr. Dimon’s compensation (like that of other presidents of major corporations) is set by a nominally independent board of directors and professional compensation consultants. However, it is today hard to take seriously the purported independence or professionalism of these kinds of directors and consultants.

In a case like K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc., the IRS effectively attacks entrepreneurial success in family-owned corporations as unreasonable. The problematic nature of these cases contrasts with recent and commendable IRS successes in combating illegal tax shelters including unreported foreign bank accounts. It is these kinds of productive activities to which the IRS should be devoting its resources, not Star Trek videos or reasonable compensation cases like K&K Veterinary Supply, Inc.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post IRS boondoggles: Star Trek videos and reasonable compensation cases appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare’s fools

Since today is April Fools’ Day, we wanted to take a look at some of the most famous fools in literature: those written by Shakespeare. Below is just a handful of Shakespearean fools from a selection of his tragedies, comedies, and more. Who are your favourite Shakespearean fools? Let us know in the comments.

Feste, Twelfth Night, or What You Will

“Many a good hanging prevents a bad marriage.”

Feste is a fool for the Countess Olivia and seems to have been attached to the household for some time, as a “fool that the Lady Olivia’s father took much delight in”. Feste claims that he wears “not motley” in his brain, so even though he dresses the part of the fool, he is not an idiot, and can see through the other characters. Indeed, there are times when he appears almost omnipresent, knowing more about Viola/Cesario’s disguise than he lets on. Certainly, he seems to leave Olivia’s house and return at his desire a little too freely for a servant, weaving in and out of the action with the sort of impunity reserved for a person nobody took seriously. He is referred to by name only once during the play, otherwise he is addressed only as “Fool,” while in the stage directions he is mentioned as “Clown.”

Touchstone, As You Like It

“The more pity, that fools may not speak wisely what wise men do foolishly.”

Touchstone is Duke Frederick’s court jester, notable for his quick wit. He is an observer of human nature, and comments on the other characters throughout the play, contributing to a better understanding of the action. Touchstone is a clever and somewhat cynical fool, although, it is referenced often in the text that he is a “natural” fool (“Fortune makes Nature’s natural the cutter-off of Nature’s wit” and “hath sent this natural for our whetstone”).

The Gravediggers, Hamlet

“What is he that builds stronger than either the mason, the shipwright, or the carpenter?”

The Gravediggers (or Clowns) appear briefly in Hamlet, making their one and only appearance at the beginning of the first scene of Act V. We meet them as they dig a grave for the recently drowned Ophelia, discussing whether she deserves a Christian burial after having killed herself. Many major themes of the play are brought up by the Gravediggers in the short time they are on stage, but they use often dark humour to examine them, contrary to the rest of the tragic play.

Titania and Bottom in a scence from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, by Edwin Landseer

Nick Bottom, A Midsummer Night’s Dream“This is to make an ass of me, to fright me if they could.”

Bottom provides comic relief throughout A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and is probably most famous for having his head transformed into that of an ass. He is a member of The Mechanicals, who are rehearsing a play, ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’, in the hope of performing it on Duke Theseus’s wedding day. Puck, a fairy, finds them in the woods rehearsing and decides to play tricks of them, such as the aforementioned transformation of Bottom’s head. The Fairy Queen, Titania, falls in love with him thanks to a potion created by her jealous husband Oberon. Later, once Titania has had the potion removed, and Puck is made to lift the ass’s head spell, Bottom wakes in a field wondering whether it was indeed a dream or not. In terms of performance, Bottom, like Horatio in Hamlet, is the only major part that can’t be doubled, meaning that the actor who plays him cannot play another character within the same play, since Bottom is present in scenes involving nearly every character

The Fool, King Lear

“Thou shouldst not have been old till thou hadst been wise”

The relationship between Lear and his Fool is founded on friendship and dependency. The Fool commentates on events and points out the truths which are either missed or ignored. When Lear banishes Cordelia, the Fool is upset, but rather than leave the ridiculous King, the Fool accompanies him on his way to madness. The Fool realises that the only true madness is to recognize this world as rational.

Trinculo, The Tempest

“I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy-headed

monster. A most scurvy monster!”

Trinculo is Alonso’s servant, a drunken jester who provides plenty of comic relief throughout the play. Caliban takes an instant dislike to him and his drunken insults. However, Trinculo becomes part of Caliban’s plan to murder Prospero which ultimately fails.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. By Edwin Henry Landseer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Shakespeare’s fools appeared first on OUPblog.

Does spelling matter?

“You can’t help respecting anybody who can spell TUESDAY, even if he doesn’t spell it right; but spelling isn’t everything. There are days when spelling Tuesday simply doesn’t count.”

- Rabbit of Owl in A.A. Milne, The House at Pooh Corner, chapter 5

As part of his agenda to improve primary school education, Michael Gove plans to invest more teaching time in driving up standards of spelling; his proposals include a list of 162 words which all eleven-year old children will be expected to spell correctly. As his critics were quick to point out, Gove’s belief in the importance of accurate spelling was somewhat undermined by a number of misspellings in the White Paper itself; Tristram Hunt gleefully suggested that Gove, “of all people,” should be able to spell bureaucracy. This highlights one of the golden rules of orthography: before you criticise someone else’s spelling, be sure your own is up to scratch.

This clamp down on spelling standards raises a question which has been debated for centuries. Should we be investing so much school time in teaching children to acquire a spelling system which is bedevilled by idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies? Wouldn’t it be simpler to reform English spelling to make it easier to learn? Calls for spelling reform have been voiced since the sixteenth century, although the proposers often had conflicting agendas. Where some reformers wished to restore a closer link between spelling and pronunciation, proposing phonetic spellings like niit “knight,” others sought to restore the link between spelling and etymology, introducing silent letters into doubt, scissors, language, thereby driving speech and writing further apart.

While spelling may pose many hurdles for unwary learners, it is by no means clear that it is the reason for comparatively low levels of literacy. Calls for reform today often draw on exaggerated and alarmist claims about the difficulties of English spelling, making unfounded links between English spelling and youth illiteracy and unemployment, and other social ills. Claims that more transparent spelling systems have resulted in higher levels of literacy in countries like Finland and Spain, where there is a closer relationship between spelling and pronunciation, are based on intuition rather than evidence, and ignore the wide range of social and educational factors that inevitably impact upon early literacy.

While spelling may pose many hurdles for unwary learners, it is by no means clear that it is the reason for comparatively low levels of literacy. Calls for reform today often draw on exaggerated and alarmist claims about the difficulties of English spelling, making unfounded links between English spelling and youth illiteracy and unemployment, and other social ills. Claims that more transparent spelling systems have resulted in higher levels of literacy in countries like Finland and Spain, where there is a closer relationship between spelling and pronunciation, are based on intuition rather than evidence, and ignore the wide range of social and educational factors that inevitably impact upon early literacy.

The English Spelling Society continues to fly the flag for spelling reform today, lobbying for wholesale simplification of the system. In September 2008 its president, John Wells, proposed relaxing spelling rules, accepting variants such as thru and lite, and ceasing to distinguish between they’re, their and there. In his speech to the Conservative Party conference in October 2008 David Cameron attacked Wells’s proposals, reformulating them as a direct assault upon educational standards: “He’s the President of the Spelling Society. Well, he’s wrong. And by the way, that’s spelt with a ‘W’.”

There is, however, an important question that gets lost in the politicisation of this debate. Is it necessary to have a standard spelling system? Why do we all need to spell the same way? It’s easy to imagine that a single spelling system is a necessity rather than a choice, but it is a comparatively recent phenomenon. In the Middle Ages there were literally hundreds of spellings of common words like through, including drowgh, yhurght, trghug, trowffe. By comparison, the proposed tolerance of thru seems positively mild. The proposal to tolerate variant spellings is not new; Mark Twain expressed a disdain for people who were only capable of spelling a word one way, while H.G. Wells viewed unusual spellings as an expression of character and personality. George Bernard Shaw left money in his will to fund an entirely new, “Shavian,” alphabet to replace the current system, whose surplus letters led to the waste of so much time and money: “Shakespeare might have written two or three more plays in the time it took him to spell his name with eleven letters instead of seven.”

Proposals to tolerate spelling variation are not merely evidence of recent liberal attitudes and slipping standards; a similar proposition to that of John Wells was made in a letter to the Times Educational Supplement in 1960, in which the writer questioned the need for a common orthography, suggesting that variants such as sieze, seize and seeze should be deemed equally acceptable. Who is responsible for these trendy, permissive suggestions? C.S. Lewis. Such a policy would also encourage a more phonetic system, since alternative spellings could accommodate the different accents spoken in Britain and throughout the world. For instance, speakers of English differ in their pronunciation of words like car and card, depending on their accent. For Scots, Irish and most North American speakers, who pronounce the r in such words, these are logical spellings. But for southern English speakers, for whom the r is silent, it would make more sense to spell such words without it.

Standardised spelling is a development closely linked with the introduction of printing; it is the role of copyeditors and proofreaders to ensure that an author’s spelling conforms to the standard. The recent publication of the manuscripts of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens provoked outrage in the media at their poor spelling. But their relaxed attitude to spelling is entirely unremarkable, given that correct spelling was imposed during the printing process. While printing has led to the establishment of a standard spelling system, the private spelling practices of diaries, letters and journals have continued to show considerable diversity up to the present day. The role of publishing houses as the gatekeepers of the standard is coming under increasing pressure today, as private spellings are now diffused more widely via websites, blogs, tweets, emails and other forms of unmediated online communication. There is a tacit acceptance that variant spellings are acceptable in such contexts and consequently the grip of the standard has begun to be loosened. Definitions in the online Urban Dictionary often view such misspellings as superior to conventional spellings; Teusday is labelled an “alternate spelling for Tuesday that better people use.” C.S. Lewis regularly used this spelling in his private letters; perhaps his extensive reading in medieval literature meant he was reviving an earlier form, or perhaps he agreed with Rabbit that there are some days when spelling Tuesday correctly just doesn’t matter.

Simon Horobin is Professor of English at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Magdalen College. His book, Does Spelling Matter?, examines the role of spelling today, considering why English spelling is so difficult to master, whether it should be reformed, and whether the electronic age signals the demise of correct spelling. He also writes a blog about English spelling.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Rykneld School Spelling Certificate by Lindosland (Own work), shared under Creative Commons CC-BY-SA-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The post Does spelling matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 31, 2013

An Oxford Companion to Game of Thrones

“My brother has his sword, King Robert has his warhammer and I have my mind…and a mind needs books as a sword needs a whetstone if it is to keep its edge. That’s why I read so much Jon Snow.”

–Tyrion Lannister

The long-awaited third season of Game of Thrones premiers on HBO 31 March 2013 and Oxford University Press has everything you need to get ready, whether you’re looking to brush up on your dragon lore, forge your own Valyrian steel, or learn about some of the most dramatic real-life succession fights culled from our archives.

For the aspiring Daenerys Targaryen:

Dragons, Serpents, and Slayers in the Classical and Early Christian Worlds: A Sourcebook

By Daniel Ogden

This comprehensive collection of dragon myths from Greek, Roman, and early Christian sources is perfect for any would-be Mother of Dragons.

Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times

By Seán McGrail

Having trouble finding boats to take you to Westeros? This collection of ancient vessels is all you need to build your own.

Goddess: Myths of the Female Divine

By David Leeming and Jake Page

A history of divine women, from Hera and Pandora to The Holy Mother.

History’s greatest “real life” Game of Thrones:

Poisoned Legacy: The Fall of the Nineteenth Egyptian Dynasty

By Aidan Dodson

Aidan Dodson explores the mysteries of the origins of the Egyptian usurper-king Amenmeses and the career of the ‘king-maker’ of the period, the chancellor Bay (sort of an Egyptian Petyr Baelish). Having helped to install at least one pharaoh on the throne, Bay’s life was ended by his abrupt execution, ordered by the woman with whom he had shared the regency of Egypt for the young and disabled King Siptah.

The Children of Henry VIII

By John Guy

Henry VIII fathered four children who survived childhood, each by a different mother. Their lives were consumed by jealously, mutual distrust, bitter rivalry, hatred…sound familiar?

“John Snow (1813–1858)” in the Oxford DNB

By Stephanie J. Snow

OK, so he only shares the same name as the member of the Night’s Watch, but still…he discovered that cholera was a waterborne infection! That’s pretty heroic.

For the student of the Common Tongue:

From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages

Edited by Michael Adams

Think Dorathki is a cool language? You may be interested in some other made-up languages.

The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary, First Edition

By Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner

No study of invented languages is complete without the father of them all, J.R.R. Tolkien.

“Words are wind – the language of Game of Thrones” on the OxfordWords Blog

By Adam Pulford

Pulford examines Martin’s language, some truly archaic and some only archaic-sounding.

For those looking to besiege King’s Landing:

Masters of the Battlefield: Great Commanders From the Classical Age to the Napoleonic Era

By Paul K. Davis

Vivid portraits of fifteen legendary military leaders on and off the battlefield. Tywin Lannister would fit right in.

The Illustrated Art of War: The Definitive English Translation by Samuel B. Griffith

By Sun Tzu

Translated with an Introduction by Samuel B. Griffith

Robb Stark could take a lesson or two from this masterpiece of battle tactics and strategy.

How to trade like you’re the richest man in Qarth:

“The Medieval Spice Trade” in The Oxford Handbook of Food History

By Paul Freedman

If you’re applying for a spot in the Ancient Guild of Spicers, this article is a must-read.

The Silk Road: A New History

By Valerie Hansen

Xaro Xhoan Daxos would have a whole chapter in this book if he were, you know, real.

Some of George R.R. Martin’s literary inspirations:

Oxford Book of British Ghost Stories

By Michael Cox and R. A. Gilbert

George R.R. Martin has his own list of recommended authors, a good many of whom are collected here.

The Classic Horror Stories

By H. P. Lovecraft

Edited by Roger Luckhurst

While note exactly fantasy, there are enough ghouls and monsters here to frighten a White Walker.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

Edited by J. R. R. Tolkien and E. V. Gordon

Revised by Norman Davis

Knights, castles, and magic. A classic.

That’s it! So crack open some of these books (and some Iron Throne Ale) and enjoy Season Three!

Jonathan Kroberger is an Associate Publicist in the New York office of Oxford University Press. Special thanks to Kimberly Hernandez for research assistance.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post An Oxford Companion to Game of Thrones appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is baseball exempt from antitrust law?

As the baseball season opens and fans wonder how their favorite teams and players will do this year, a certain sort of fan will also wonder about a perennial question. Why is baseball the only sport exempt from antitrust law?

The answer cannot be found in the text of the antitrust statutes, which do not distinguish between baseball and other forms of enterprise. Nor can it be found in the economic structure of the baseball business, which is identical to that of the other major professional team sports. Applying antitrust law to sports can raise some difficult questions, but they are the same questions in baseball as in other sports. There is no reason to treat an agreement to restrict the location of baseball teams, for example, differently from an agreement to restrict the location of football teams. The antitrust concerns implicated by a draft of baseball players are the same as those implicated by a draft of basketball players. So how did baseball become the only sport exempt from the antitrust laws?

Denver Grigsby, a Yankee spring prospect and future Chicago Cubs outfielder, in 1922, the year of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The exemption’s origin is a 1922 Supreme Court case called Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League, in which the Court held that the federal antitrust laws did not apply to baseball, because these laws only governed interstate commerce, and baseball was not a form of interstate commerce. The issue returned to the Supreme Court in 1953 and 1972, and both times the Court declined to overrule Federal Baseball Club, even though the conventional professional understanding of interstate commerce had expanded dramatically in the interim. Meanwhile, in two cases from the 1950s, one involving boxing and the other football, the Court made clear that the exemption is only for baseball, not for sports generally. Congress has had the power, all the while, to amend the antitrust laws to treat sports equally, but it has done so only to a very limited extent. The outcome of this combination of activity and inactivity is an exemption just for baseball, one that is now nearly a century old.

How can we explain the persistence of such a weird state of affairs? The most common explanation emphasizes the unique position of baseball in American culture. Judges and legislators have bent over backwards, the argument goes, to protect the national pastime.

But while baseball no doubt has a meaning in American culture unlike that of other sports, and while one can certainly find examples of judges and politicians proclaiming their love for baseball, there is much more to baseball’s exemption than the desire of government officials to express their passion for the game by insulating it from lawsuits. It is a story in which a sophisticated business organization has been able to work the levers of the legal system to achieve a result favored by almost no one else. For all the well-known foibles of the owners of major league baseball teams, baseball has consistently received and followed smart antitrust advice from sharp lawyers, all the way back to the 1910s, when the sport faced its first antitrust crisis.

At the same time, it is a story that serves as an arresting reminder of the path-dependent nature of the legal system. At each step, judges and legislators made decisions that were perfectly sensible when considered one at a time, but this series of decisions yielded an outcome that makes no sense at all.

Stuart Banner is the Norman Abrams Professor of Law at UCLA. His latest book, The Baseball Trust: A History of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption (2013), has just been published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why is baseball exempt from antitrust law? appeared first on OUPblog.

The death of Charlotte Brontë

By Janet Gezari

I ordered the Kindle edition of Ellie Stevenson’s recent collection, Watching Charlotte Brontë Die: and Other Surreal Stories, because I was curious, and it cost only $2.99. In the title story, Charlotte Brontë dies (or seems to) while riding a bicycle, run down by a car on a cold, wet night. The narrator, a “writer’s researcher” who is obsessed with Charlotte and who lives near Haworth, Charlotte’s birthplace, perhaps 150 years later, remarks that he hadn’t known that Charlotte could ride a bike. The image of Charlotte riding a bicycle is more fanciful than surreal. Although the ancestor of our modern bicycle, the velocipede, was invented in 1817, it was only in the last decades of the nineteenth century that Victorians embraced the bicycle. Even these improved, later bicycles wouldn’t have been a useful means of transportation in the village of Haworth with its steep, cobbled main road, or on the squishy moors nearby where the Brontës walked in all weathers.

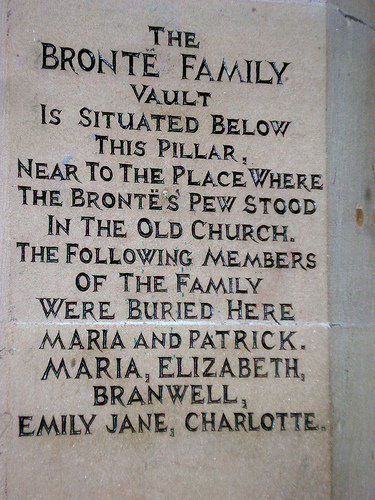

The Brontë family vault at Haworth Church

Her actual death followed a debilitating illness and occurred almost exactly nine months after her marriage to her father’s curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls. The death certificate states its cause as “Phthisis” or acute tuberculosis, the same disease that killed Emily and Anne. We know that Charlotte could eat or drink almost nothing until a few weeks before her death and that she was rapidly losing weight. Lyndall Gordon suggests she had a bacterial infection like typhoid, noting that Tabitha Ackroyd, the Brontës’ servant, had died from a digestive infection six weeks earlier and could have communicated it to Charlotte. During Charlotte’s and Tabby’s lifetimes, contaminated water and inadequate sewerage made Haworth one of the unhealthiest places to live in England. Charlotte may have been pregnant (in a letter, she suggests that she was), even though her death certificate omits this information. One conjecture is that she was suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum, an extreme form of morning sickness that affects no more than 2% of women in the early stages of their pregnancy and is rarely fatal. This past December, when Catherine, the Duchess of Cambridge, was admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum, an evolutionary biologist applauded its adaptive virtues and declared that women suffering from it have a reduced risk of miscarriage. (This is a welcome antidote to the myth that associates morning sickness with a neurotic rejection of pregnancy.) It’s hard to know how Charlotte, who saw herself as a daughter, a sister, and at last a wife, would have managed as a mother. Jane Eyre is the only one of her heroines who gives birth to a child, and Jane spends no narrative time on either her agency in this event or her life after it. The novel’s only reference to Jane’s child calls our attention to his eyes, which resemble his father’s “as they once were — large, brilliant, and black.” Like the Duchess of Cambridge, Jane accepts her reproductive mission in life, and many readers have been unable to forgive her for trading so much thrilling rebellion for happy conformity in the end.

Unlike either Anne or Emily, Charlotte was an avid letter-writer, but she was too ill to keep up with her correspondence in the weeks before her death. The few letters she wrote are mainly concerned with other peoples’ illnesses. Even if she had not written her novels, Charlotte’s correspondence—about 950 of her letters have survived—would have made her memorable. Like her novels, her letters convey the social isolation she felt and combatted. Emily thrived in her isolation, and Anne escaped it by finding steady employment as a governess in a busy household, but Charlotte could not feel alive without loving companionship. Her most notorious letters are the ones she wrote to her married Belgian professor, Constantin Heger, revealing what she would have called her monomania and what we would today call a desperate crush. We don’t have Charlotte’s letters to Arthur Bell Nicholls or his to her. Charlotte’s decision to marry him was a healthy response to the intensified barrenness of her life after Anne’s and especially Emily’s death. When she accepted Nicholls, she knew that she was not gaining a husband with “fine talents” and “congenial” views (Gaskell, who approved of the marriage, described him as “very stern and bigoted”), but she believed, rightly, that she would gain a devotion that was passionate and steady. Since only her father, her husband, and two former servants were at her bedside when she died, we lack an account of her death to match her fiercely truthful accounts of the deaths of Anne and Emily. There was no one watching Charlotte Brontë die who could register the awfulness and the ordinariness of her dying.

Janet Gezari is Lucretia L. Allyn Professor of Literatures in English at Connecticut College. She is the author of Charlotte Brontë and Defensive Conduct, Last Things: Emily Brontë’s Poems, and the introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Charlotte Brontë’s Selected Letters. She is currently editing The Annotated Wuthering Heights (forthcoming from Harvard University Press).

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo of Brontë family vault. Used with permission from sharpandkeen via Flickr. Do not reproduce with permission of the photographer.

The post The death of Charlotte Brontë appeared first on OUPblog.

March 30, 2013

Disappearing States

The Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, now in its 54th year, gathers competitors from over 550 law schools who compete in a simulated fictional dispute before the International Court of Justice. To celebrate the theme of this year’s competition, OUP author Jane McAdam has written a special blog piece on climate change and the phenomenon of the ‘disappearing’ state.

By Jane McAdam

The ‘disappearing State’ or ‘sinking island’ phenomenon has become a litmus test for the dramatic impacts of climate change on human society. Atlantis-style predictions of whole countries disappearing beneath the waves raise fascinating legal issues that go to the heart of the rules on the creation and extinction of States. These rules have never been tested in this way before. But while the potential loss of territory for environmental reasons is novel, much of this deliberation is taking place in the abstract. Underlying assumptions about why, when, whether, and how States might ‘disappear’, and the consequences, do not always sit comfortably with the empirical evidence. The danger is that this may lead to well-intentioned, but ultimately misguided, responses.

The criteria for statehood under international law are four-fold: a defined territory, a permanent population, an effective government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other States. While all four criteria would seemingly need to be present for a State to come into existence, the absence of all four does not necessarily mean that a State has ceased to exist. This derives from the strong presumption of continuity of States in international law, which presumes that existing States continue even when some of the formal criteria of statehood start to wane.

In the context of climate change, it is often assumed that sea-level rise will ultimately inundate the territory of certain low-lying island countries, thus rendering it uninhabitable. It is true that small low-lying island States are particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts, including loss of coastal land and infrastructure due to erosion, inundation, sea-level rise and storm surges; an increase in the frequency and severity of cyclones, creating risks to life, health and homes; loss of coral reefs, with attendant implications for food security and the ecosystems on which many islanders’ livelihoods depend; changing rainfall patterns, leading to flooding in some areas, drought in others, and threats to fresh water supplies; salt-water intrusion into agricultural land; and extreme temperatures.

However, the focus on loss of territory as the indicator of a State’s ‘disappearance’ may be misplaced. Low-lying atoll countries are likely to become uninhabitable as a result of diminished water supplies long before they physically disappear. In October 2011, for example, Tuvalu declared a state of emergency because of severe water shortages, necessitating an urgent humanitarian response (temporary desalination plants, rehydration packs, technical support, and water supplies) from Australia and New Zealand.

In international law terms, then, the absence of population, rather than territory, may be the first signal that an entity no longer displays the full indicia of statehood. But where would people go, and what would their legal status be?

Movement away from small island States is likely to be slow and gradual, rather than triggered by a sudden event. Although migration has long been a natural human adaptation strategy to environmental variability, the legal (and sometimes physical) barriers to entry imposed by States today considerably restrict people’s ability to move.

If people seek to enter another country without permission to do so, they may find themselves in a very precarious legal position, potentially without work rights, basic health care, or social services. They will generally not meet the legal definition of ‘refugee’, which requires a person to show a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of a particular attribute (such as religion or political opinion). Nor is it clear that they will benefit from complementary protection under human rights law (non-return to a risk to life or inhuman or degrading treatment) — although the more debilitated the home environment, the better chance they will have. Finally, it is unlikely that they would be recognized as stateless persons, since that legal definition is deliberately restricted to people who are ‘not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law’. Whether or not this could be met may depend in part on whether the ‘State’ is considered still to exist. In any event, though, the statelessness treaties are poorly ratified and few States have statelessness determination procedures in place or a protective legal status for such people.

The relocation of whole communities has been raised from time to time as a solution for small island States. But this is an option of last resort for most, and one which should be treated with considerable caution. This is because there is much more to relocation than simply securing territory. Apart from fundamental issues about identity and self-determination, those who move need to know that they can remain and re-enter the new country, enjoy work rights and health rights there, have access to social security if necessary and be able to maintain their culture and traditions, and also what the legal status of children born there would be. There is also the question of how to balance the human rights of relocating groups with those of the communities into which they move. The effects of dislocation from home can last for generations and have significant ramifications for the maintenance and enjoyment of cultural and social rights by resettled communities. That is clear from the situation of the Banabans on Rabi, who were relocated in 1945 from present-day Kiribati to Fiji.

This is why a key policy objective of some small island States is to enhance existing migration options to developed countries in the region. Managed migration is a safer mechanism for enabling people to move away from the longer-term effects of climate change, without artificially treating people as in need of international ‘protection’ (from a persecutory State). It can play an important role in livelihood diversification and risk management strategies. Furthermore, given that one of the biggest problems for small island States is overpopulation, increased migration could help to relieve population and resource pressure. This may mean that a smaller population could remain on the territory for longer.

Jane McAdam is Scientia Professor of Law at the University of New South Wales, Australia and a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. She is the author of Climate Change, Forced Migration, and International Law.

We would like to offer competitors of the Jessup Moot a month of free access to the Journal of International Criminal Justice. Your access will last through 6 May 2013.

To activate your trial, follow the below steps:

1. Register with My Account: Visit My Account online to create your account. If you have already created a login for My Account, simply login into your account with your username and password.

2. Register your trial subscription: Once you have created an account or logged in with My Account, click the link ‘Manage your subscriptions.’

3. Activate the subscriber number: Enter the subscriber number A1695267, check the box next to the license agreement, and click the button ‘Add Subscription.’

Once you’ve completed online registration for a free trial access, you will be free to browse, read and save articles. Please note that in rare cases it can take up to 36 hours for a free trial to activate.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Tinny, small tropical island in Indian ocean during a storm with wind and rain. Photo by Alfaproxima, iStockphoto.

The post Disappearing States appeared first on OUPblog.

Constantine and Easter

Christians today owe a tremendous debt to the Roman emperor Constantine. He changed the place of the Church in the Roman World, moving it through his own conversion from the persecuted fringe of the empire’s religious landscape to the center of the empire’s system of belief. He also tackled huge problems with the way Christians understood their community. The three most important things the church owed to Constantine were a roadmap for reuniting communities split by persecution, a universal definition of the Church’s teaching, and a fixed date for the celebration of Easter. His solutions to the second and third issues remain in place to this day.

Constantine dealt with all three of the Church’s major issues at the conference he summoned at the ancient city of Nicaea (modern Iznik in Turkey) in June of 325 AD. The issue of persecution stemmed from a period of bitter conflict with the imperial government that had ended just over ten years before the council convened, while the debate over the Church’s teaching had exploded a few years before Nicaea (the issue was Jesus’ humanity). The Easter question had been festering for centuries, and the problems were inextricably tied up with the fact that no one recorded the actual day of the Crucifixion.

All that people could know on the basis of Christian Scripture was that the crucifixion was linked to the celebration of Passover, which meant that it should come at some point in the spring. But when? Since the date of Passover, then as now, is celebrated in accordance with the Jewish calendar, the correlation with the Julian calendar used by Christians and most other inhabitants of the Roman Empire was always inexact. Some Christians believed that the best way to solve the problem was to celebrate Easter on the first day of Passover according to the Jewish calendar, another group held that Easter should be celebrated on the first Sunday after the opening of Passover, while yet another group felt that the timing of the Christian festival should not be determined by the timing of Passover and should instead be celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the Vernal Equinox.

Emperor Constantine I, presenting a model of the city to Virgin Pary. Detail of the southwestern entrance mosaic in Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey). Photo by Myrabella. Creative Commons License.

The Easter story was extremely important to Constantine. Conscious as he was that he had been raised as a pagan, and that he had done things in his earlier life of which he was not proud (he never tells us what those things were), he felt that he had experienced a sort of moral resurrection when he became a Christian. He credited his extraordinary military career to God’s willingness to forgive his past sins and he wanted to make sure that he ruled in a way that would repay the benefits he believed his God had given him. In a sense there was nothing more obvious to Constantine than that Easter shouldn’t be connected with the festival of another faith. It should stand on its own in connection with the natural world. Hence he ordained that Easter should be celebrated on the Sunday after the first New Moon of Spring.

The solution to the Easter issue had the added advantage of allowing him to make an important concession to the group whose definition of the Faith he was rejecting outright at Nicaea, the so-called Arian faction, named for the Egyptian priest who had aggressively preached a doctrine asserting the human aspect of Christ. Constantine liked his God, like his empire, to be completely united, which is what we see today in the Nicene Creed in the phrase “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God.” That desire for unity also enabled him to arrive at an acceptable solution to the divisions that had arisen out of the period of persecution as he essentially argued that the two sides should bury the hatchet and recognize each other as Christians first. That approach has not had nearly so much influence as his approach to Easter or to the Trinity.

Constantine was a complex and at times difficult man, a passionate one with a ferocious temper. But he was also a man who was able to recognize his own weaknesses. It may have been that self-knowledge which enabled him to come to the new faith he hoped would make him a better ruler, and gave him the ability to find and forge compromises to build a better and more unified society.

David Potter is Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Greek and Latin at the University of Michigan. His books include Constantine the Emperor, The Victor’s Crown, Emperors of Rome, and Ancient Rome: A New History.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Constantine and Easter appeared first on OUPblog.

March 29, 2013

Free will and quantum conspiracy

We all agree that heredity, previous experience, and environment influence our choices. But why do some claim that, fundamentally, free will is an illusion? The easy answer: Free will does not fit within a scientific worldview. Free will mysteriously brings about a choice, and a physical event, without a prior physical cause. A motive for denying free will is to explain away that mystery. It’s a good motive. Explaining mysteries is a motive driving the scientific endeavor.

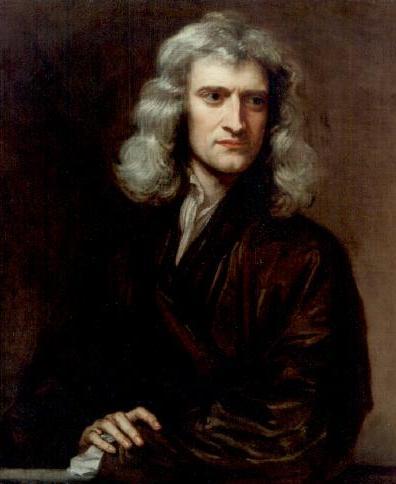

Our strict sense of cause and effect came with Newton’s physics, “classical physics.” To an “all-seeing eye” that knew the position and velocity of each atom in the universe at a given moment, the entire future of universe would be known. The idea that every event, even every thought, has a prior cause is part of our Newtonian heritage; it’s the determinism of classical physics. Most arguments denying free will are ultimately based on this determinism. Classical physics provides an extremely good approximation for the big things we ordinarily deal with, but it’s just an approximation. It fails completely for the atoms and molecules that big things are made of. Reasoning about free will should not be based on classical physics, a fundamentally flawed physics.

Our strict sense of cause and effect came with Newton’s physics, “classical physics.” To an “all-seeing eye” that knew the position and velocity of each atom in the universe at a given moment, the entire future of universe would be known. The idea that every event, even every thought, has a prior cause is part of our Newtonian heritage; it’s the determinism of classical physics. Most arguments denying free will are ultimately based on this determinism. Classical physics provides an extremely good approximation for the big things we ordinarily deal with, but it’s just an approximation. It fails completely for the atoms and molecules that big things are made of. Reasoning about free will should not be based on classical physics, a fundamentally flawed physics.

Quantum physics, or quantum mechanics, is the most battle-tested theory in all of science. No prediction of quantum mechanics has ever been wrong. It applies universally, to the big as well as the small. One-third of our economy is based on things designed with quantum mechanics. A quantum measurement problem was recognized at the inception of the theory almost a century ago. Physicists usually present it in mathematical terms, where the human issue of free will is obscure. The quantum measurement problem is sometimes, more appropriately, called the observer problem, a name emphasizing that it can be seen directly in quantum-theory-neutral observations.

The observer problem arises because you can demonstrate that a small object had either of two contradictory properties. The usual property considered (in what is sometimes called wave-particle duality) is the property of extension, how big something is. You could, for example, demonstrate that an object had been compact, concentrated in some small location, like a grain of sand. Alternatively, you could demonstrate that the object had been not compact, that it was spread out over a wide range, like a patch of fog.

Problem: Since we feel that we could have demonstrated either of two contradictory properties, what was the “actual” property of the object before we chose which of the two contradictory properties to demonstrate?

The standard quantum physics solution: Accept free will as something beyond physics. (“The free choice of the experimenter” is our preferred physics usage, not “free will.”) The experimenter’s free choice of demonstration, without any physical force on the object, creates the “actual” property the object had.

An alternate solution: Deny free will. Quantum mechanics then requires a determinism that conspires to match the experimenter’s not-free choice to the “actual” property the object had.

Bottom line: Denying free will implies a mysterious conspiratorial determinism.

Bruce Rosenblum and Fred Kuttner are the authors of Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness. Bruce Rosenblum is currently Professor of Physics, emeritus, at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He has also consulted extensively for government and industry on technical and policy issues. His research has moved from molecular physics to condensed matter physics, and, after a foray into biophysics, has focused on fundamental issues in quantum mechanics. Fred Kuttner is a Lecturer in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He devotes most of his time to teaching physics after a career in industry, including two technology startups, and a second career in academic administration. His research interests have included the low temperature propoerties o solids and the thermal properties of magnets. For the last several years he has worked on the foundations of quantum mechanics and the implications of the quantum theory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Portrait of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (August 8, 1646 -October 19, 1723). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Free will and quantum conspiracy appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of same-sex marriage by the numbers

This week, the US Supreme Court heard two cases that could change same-sex marriage laws nationwide. If the Defense of Marriage Act and Proposition 8 are ruled illegal, same-sex couples around the nation could rush to the altar this summer.

To help measure the impact of this ruling on the population, Social Explorer took a look at data on same-sex couples. The Census and American Community Survey collect data on unmarried partners living together. These numbers offer some insight into how many co-habitating same-sex partners might consider marriage if it became a legal right.

To help measure the impact of this ruling on the population, Social Explorer took a look at data on same-sex couples. The Census and American Community Survey collect data on unmarried partners living together. These numbers offer some insight into how many co-habitating same-sex partners might consider marriage if it became a legal right.

According to the 2011 American Community Survey:

There were 605,472 same-sex unmarried partners nationwide.

Those couples accounted for 9% of all unmarried partner households.

There were 87,078 unmarried same-sex partners in California.

California accounts for 14.4% of same-sex partners living together.

The New York Times household comparison tool created with Social Explorer and IPUMS data and analysis shows that unmarried same-sex partners have higher incomes than both married couples and unmarried opposite-sex partners.

You can explore a more detailed view of same-sex unmarried partners in California, your neighborhood, and elsewhere using Social Explorer’s five-year American Community Survey map.

Interactive Map of Same-Sex Unmarried Partners (American Community Survey 2006-10)

Check out Social Explorer’s map and report tools to find out more about same-sex couples and other groups.

Sydney Beveridge is the Media and Content Editor for Social Explorer, where she works on the blog, curriculum materials, how-to-videos, social media outreach, presentations and strategic planning. She is a graduate of Swarthmore College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. A version of this article originally appeared on the Social Explorer blog.

Social Explorer is an online research tool designed to provide quick and easy access to current and historical census data and demographic information. The easy-to-use web interface lets users create maps and reports to better illustrate, analyze and understand demography and social change. From research libraries to classrooms to the front page of the New York Times, Social Explorer is helping people engage with society and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Rainbow flag from Wikimedia Commons.

The post The future of same-sex marriage by the numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers