Oxford University Press's Blog, page 965

March 25, 2013

Is competition always good?

Wow! That is what my university’s former football coach wanted to hear from prospective student-athletes when touring the new $45 million football practice facility. Parts of my university need repair. Departments face resource constraints. But the new practice facility was to set the standard in the university’s fierce competition for talented recruits. So our former coach led reporters through the planned 145,000 square-foot building, with its grand team meeting room, custom-designed chairs, hydro-therapy room, restaurant, nutrition bar, and lockers equipped to charge iPads and cellphones. But as the tour concluded, our coach observed that several rival universities, upon seeing our planned facility, were planning even more expensive training facilities. As our rivals spend millions on elaborate facilities, none of the universities have a sustained competitive advantage. And other student needs remain unmet.

Competition is ordinarily viewed as good. It is, after all, the backbone of most developed countries’ economic policies. Promoting competition is broadly accepted as the best available tool for promoting economic well-being. Competition can yield lower prices, better quality, more choices, innovation, greater efficiency, increased productivity, and additional economic development and growth. Competition has its social and moral virtues, such as promoting individual initiative, liberty, and free association. Not surprisingly, competition can take a religious quality, especially among antitrust enforcers. They regularly try to protect the public from harmful special interest legislation, premised on complaints of excess competition.

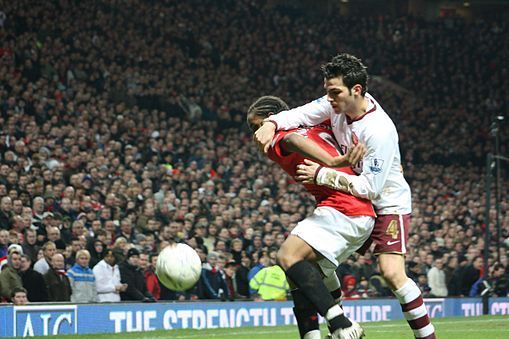

Competition, although seen as good, is not pervasive. At times the laws and informal norms stress cooperation, rather than competition. We don’t want parishioners, after all, competing for pews, or children competing for their parents’ affection. Some areas aren’t subject to market competition (e.g. human organs) or are exempt from competition laws (e.g. labor). Even though competition is generally seen as good, not all forms of competition are necessarily good. So we distinguish between fair and unfair means of competing — to promote the soccer player’s artful pass while punishing the scoundrel’s rough elbow. But for most commercial activity, competition on the merits is the presumed policy. It is the glue that binds our economy.

While watching my university’s football coach tour the state-of-the-art facilities, I wondered whether competition always benefits society. When does competition devolve into its pejorative synonyms: arms race and race-to-the-bottom? When is competition the problem’s cause, rather than its cure? These questions expose competition policy’s blind spot. Few within antitrust circles ask these questions. Instead, their elixir often is more, rather than less, competition.

Interestingly, an economist examined over a century ago these questions. Competition, Irving Fisher found, works to society’s benefit under two assumptions: first, when each individual can best judge what serves his interest and makes him happy; and second, when individual interests are aligned with collective interests. These two assumptions often are valid; competition, as a result, reliably delivers. But when these assumptions don’t hold, as recent developments in the economic and psychology literature show, competition can worsen the problem. One scenario is where firms effectively compete to exploit overconfident consumers with imperfect willpower (think credit cards). Rather than compete to help consumers obtain or find solutions for their imperfect willpower, firms instead compete in devising better ways to exploit consumers.

A second scenario is where individual and group interests diverge. Competition benefits society when individual and group interests and incentives are aligned (or at least don’t conflict). But when individual interests diverge from collective interests, as in the case of testosterone, the competitors and society are worse off. Wall Street traders, the press reports, are boosting their testosterone levels. One study found that traders, with higher morning testosterone levels, were likelier to earn more profits that day. Higher testosterone levels can increase the traders’ appetite for risk and fearlessness. So traders, weighing the benefits and risks, can rationally decide to boost their testosterone levels to gain a relative competitive advantage (or at least not be competitively disadvantaged against higher testosterone traders). However, as other traders inject testosterone, the traders no longer enjoy a relative competitive advantage. They and society are collectively worse off.

We saw this race-to-the-bottom before the economic crisis. With the expansion of Fitch Ratings, the competitive pressures on the two entrenched ratings agencies increased. Their cultures changed. They increasingly emphasized greater market share and short-term profits. To gain a relative advantage, they lowered their rating requirements. Their ratings quality deteriorated. As the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission found, Moody’s alone rated nearly 45,000 mortgage-related securities as AAA. In contrast, in early 2010, only six private-sector companies were rated AAA. So too nations compete for a relative advantage by relaxing their banking, environmental, safety, and labor protections. Their competitive race-to-the-bottom ultimately leaves them and their citizens collectively worse off.

So is competition in a market economy always good? If the answer is no, a separate issue is whether we should allow private parties to deal with these types of failures or whether legislation is required. Once we recognize that market competition produces at times worse results, the debate shifts to whether the problem of suboptimal competition can be better resolved privately (by perhaps relaxing antitrust scrutiny to private restraints) or with additional governmental regulations (which raises issues over the form of regulation and who should regulate).

So when you hear the policymaker’s refrain of making markets more competitive, competition likely is the solution. But as football coaches, Wall Street traders, ratings agencies, and nations realize, increasing competition at times worsens, rather than cures, the problem.

When he joined the University of Tennessee in 2007, Prof. Maurice E. Stucke brought 13 years of litigation experience as an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and Sullivan & Cromwell. A Fulbright Scholar in 2010-2011 in the People’s Republic of China, he serves as a Senior Fellow at the American Antitrust Institute, on the boards of the Academic Society for Competition Law and the Institute for Consumer Antitrust Studies, and as one of the United States’ non-governmental advisors to the International Competition Network. His scholarship has been cited by the U.S. courts, the OECD, competition agencies, and policymakers. You can read his article “Is competition always good?” in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement.

The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement is a new launch journal from Oxford University Press in 2013. All content is freely available online for a limited time and papers published ahead of the first print volume (April 2013) are available online now. The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement provides a platform for leading scholarship on public and private competition law enforcement, at both domestic and international levels. The journal covers a wide range of enforcement related topics, including: public and private competition law enforcement, cooperation between competition agencies, the promotion of worldwide competition law enforcement, optimal design of enforcement policies, performance measurement, empirical analysis of enforcement policies, combination of functions in the competition agency mandate, and competition agency governance. Other topics include the role of the judiciary in competition enforcement, leniency, cartel prosecution, effective merger enforcement, competition enforcement and human rights, and the regulation of sectors.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) The University of Tennessee Pride of the Southland Marching Band performs pregame at the UT vs. California football game. Photo by Jordan3757, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) Arsenal’s Cesc Fàbregas (white shirt) duels with Anderson of Manchester United. Photo by Gordon Flood, Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is competition always good? appeared first on OUPblog.

Alcohol advertising, by any other name…

Most adults won’t be familiar with the music video You Make Me Feel by Cobra Starship, as it has much greater appeal to young people. There is little doubt however that the overwhelming majority of adults would quickly identify the product placement in the video, as seen in screenshot below. The commercial intent of the product placement in this example is self-evident. Despite this, it is not considered to be an “alcohol beverage advertisement” by the Australian Alcohol Beverages Advertising Code (ABAC). There are a number of concerns with the current self-regulation scheme in Australia, but most equivalent international codes do not cover product placement either, as detailed by ABAC.

This rather obvious example serves two purposes: it highlights the shortcomings in current regulations, not just in Australia; and it provides insight into how easily and often young people are exposed to product placement.

To be clear, product placement is advertising. The European Union define product placement as “…any form of audio-visual commercial communication consisting of the inclusion of or reference to a product, a service or the trade mark thereof so that it is featured within a programme, in return for payment or for similar consideration”. Like all other types of advertising, product placement has a number of purposes. The most explicit of these is to encourage consumers to buy more of the product. But product placement has a more subtle capacity to change community attitudes and norms. It is not just paid product placement that has the potential to influence though, unpaid incidental product placement is just as concerning and harder to regulate.

Endorsement of alcohol use by celebrities, like the musicians and actors who feature in music videos, has a substantial influence on the attitudes and behaviours of young people. Similarly, tobacco promotion in popular media is a significant contributor to the uptake of smoking by the young. For example, teenagers whose favourite stars smoke on screen are up to 16 times more likely to think favourably of smoking, and are more likely to smoke than those whose favourite stars do not smoke.

Young people need protection from advertising. It has long been known that children and adolescents are more vulnerable to advertising than adults. Many countries recognise this vulnerability and have regulations that restrict advertising to children in addition to any restrictions on alcohol and tobacco advertising that may exist. But regulations can easily be circumvented.

In Australia, Saturday morning is a time when children often watch television and there are broadcasting restrictions to ensure that the content is suitable. Two (Commercial Television Industry Code of Practice and Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) Code of Practice) of the three (Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association (ASTRA) Codes of Practice is the exception) television codes of practice for Australia make explicit reference to weekend mornings between 0600 and 1000 being reserved for “general” viewing, in other words suitable for children. All of these codes require discretion or care when portraying legal drug use during programs with a “General” classification.

There is cause for concern then, when almost one-third of the videos shown on television on Saturday morning, during a designated children’s viewing time, contain a reference to alcohol or tobacco and the vast majority of those references were pro-use. Alcohol references are more common (by about four times) than tobacco references, most likely reflecting the declining popularity of smoking among young people.

Our young people deserve better than this. It is clear that product placement is an effective and pervasive advertising technique, but is currently unregulated in Australia. There is an urgent and acknowledged need to expand the definition of advertising to include all promotional and marketing activities, not just product placement. On the other hand, parents should also be able to trust the classification of television programs, and that their children aren’t being encouraged to drink and smoke every time they watch programs deemed suitable for a general audience.

Steve (Iain) Pratt is Nutrition and Physical Activity Manager at Cancer Council Western Australia and Adjunct Research Fellow at Curtin University. He is an Accredited Practising Dietitian (APD) and Accredited Exercise Physiologist (AEP) with more than ten years’ experience in public health. You can follow him on Twitter @Pratt_Steve. Dr Emma Croager is Education & Research Services Manager at Cancer Council Western Australia; and Senior Adjunct Research Fellow at Curtin University, Western Australia. Since returning to Australia in 2006, she has worked in chronic disease prevention and public health, with a specific focus on lifestyle risk factors for chronic disease, and rural and remote health. You can follow her on Twitter @emmacroager. They are the co-authors, along with Rebecca Johnson and Natalie Khoo, of the paper ‘Legal drug content in music video programs shown on Australian television on Saturday mornings‘, which is available to read for free on the Alcohol and Alcoholism journal website.

Alcohol and Alcoholism publishes papers on biomedical, psychological and sociological aspects of alcoholism and alcohol research, provided that they make a new and significant contribution to knowledge in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Still taken from the official video for You Make Me Feel by Cobra Starship.

The post Alcohol advertising, by any other name… appeared first on OUPblog.

March 24, 2013

Happy Birthday, Topsy

By David Leopold

William Morris (1834-1896) is widely recognized as the greatest ever English designer, a poet ranked by contemporaries alongside Tennyson and Browning, and an internationally renowned figure in the history of socialism. However, since the year 2013 offers no ‘big’ anniversary as a pretext to survey these various major achievements, I will instead use 24 March (his birthday) as an excuse to look at how Morris actually spent some of his own birthdays. We might not share his achievements, but, in certain respects at least, his birthdays might look rather like our own. Not least, they were occasions on which to be reminded of family, friends, and one’s own mortality.

Appropriately enough, Morris’s mother Emma emerges (from correspondence at least) as perhaps the most reliable celebrant and gift-giver; a ‘very nicely worked’ cloth in 1885, a pair of candlesticks three years later. Morris had moved some considerable political and cultural distance from his conventional bourgeois upbringing, but his mother remained a lively and supportive presence throughout nearly his entire life. In 1890 (when her health had finally begun to fail), Morris feigned a stern tone in responding to her birthday greetings, warning that ‘I shall have to scold you if you talk of presents. Your love is the best present I can have’. Her death in 1894 (aged 89) hit Morris unexpectedly hard; he confided to Georgiana Burne-Jones that even his ‘old and callous heart’ had been touched by the absence of ‘what had been so kind to me and fond of me’.

Birthdays were also, of course, an occasion for Morris’s more immediate family, especially since his daughter May was born on 25 March and they often held a joint celebration. If Morris was away, he would report back on his birthday to his family. An 1878 letter to his (two) daughters shows parental kindness moderating, but not effacing, Morris’s critical eye for design detail; he thanks May for her gift of a very pretty ‘baccy pouch’ but insists that the cotton strings will need replacing with silk to avoid setting his teeth on edge when opening it. In the same year, he provided his wife Jane with a humorous sketch of the morning after his birthday dinner with his mother and (second) sister Henrietta in Much Hadham, in Hertfordshire. Rogers (his mother’s maid) had cut his hair in the presence of not only his ‘kinswomen’ but also his mother’s parrot; the latter, at least, was seemingly delighted with the entertainment and ‘mewed & barked & swore & sang at the top of his vulgar voice’.

William Morris, aged 53

Birthdays were also an occasion for being remembered by, and spending time with, his friends. In thanking Louisa Baldwin for ‘remembering me & my birthday’ in 1875, Morris added that he had always been a lucky man with his friends. Those friendships, however, were sometimes tested by his occasional ill-humour and quick temper (usually immediately followed by embarrassment and regret). After one especially ‘crabby’ birthday evening (1869) spent in the company of Edward Burne Jones (‘Ned’) and Charles Fairfax Murray, Morris felt obliged to write apologies to both men. Admitting that he could be ‘like a hedgehog with nastiness’, Morris craved forgiveness from Burne-Jones on the grounds that he simply could not do without him.Birthdays also provide a reminder of our own mortality. Morris met middle-age with a familiar mixture of melancholy and resignation. On his thirty-ninth birthday he complained (to Charles Eliot Norton) that his hair was turning grey. A year later he described turning forty (to Louisa Baldwin) as a ‘sad occasion’ despite the fact that he felt no older. As the years passed, a sense of acquiescing in the inevitable seems to have displaced that earlier angst. By 1887, Morris could be found simply confiding to his diary: ‘fifty-three years old today – no use grumbling at that’.

And lastly, at least beyond childhood, birthdays are often simply days like any other. Morris’s own daily routine typically took a fiercely energetic form, involving work and politics. In 1874, he told one birthday correspondent that the day itself had been ‘solemnized’ only by his laboring hard at the illuminations (probably of The Odes of Horace) which were currently his chief joy. And in 1888, his birthday fell during a socialist tour of the more ‘wretched’ parts of Scotland, and Morris spent the day lecturing in the mining town of West Caldor, in West Lothian.

In thanking Louisa Baldwin for her birthday greetings of 1875, Morris speculated on some connections between two of these themes – politics and mortality – and wondered whether our failure to have created a better world might not reflect the shortness of our mortal coil. Perhaps, he mused, we are simply not here long enough to turn sufficient attention towards making the world a more rational and humane place. However, by the time he came to write News From Nowhere (1890), the great utopian novel of his later years, Morris had reversed the putative connection here, turning idle regret into realistic aspiration in the process. It was only after they had created a society embodying equality and community that the inhabitants of Nowhere came to live much longer lives. When a visitor expresses surprise at the vigour and vitality of a man in his nineties (but looking much younger), he is told that in Nowhere they have beaten the three-score and ten of ‘the old Jewish proverb book’, and, more importantly, that those lives now contain much more in the way of health and happiness.

David Leopold is University Lecturer in Political Theory, University of Oxford, and John Milton Fellow, Mansfield College, Oxford. He has edited William Morris’s News From Nowhere, for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Morris, aged 53. By Frederick Hollyer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Happy Birthday, Topsy appeared first on OUPblog.

The historical arc of tuberculosis prevention

In Tijuana, Mexico, 43-year-old tuberculosis patient Maria Melero takes her daily medicines at home while her health worker watches on Skype. Thirteen thousand kilometers away in New Delhi, India, Vishnu Maya visits a neighborhood health center to take her TB meds. A counselor uses a laptop to record Maya’s fingerprint electronically. An SMS is then sent to a centralized control center to confirm that Maya has received today’s dose.

The global burden of TB is massive and such episodes are repeated daily across the world. Although incidence and death rates have been falling in many regions—TB mortality has dropped by 41% since 1990—the WHO estimates that there were 8.7 million new cases in 2011. Deaths totaled 1.4 million people, 30% of whom were also HIV positive. Maria and Maya belong to a growing number of people who suffer from multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB, which is caused by organisms that are stubbornly unmoved by the most effective anti-TB drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin. In 2011 there were about half a million new MDR–TB cases and 9% of these are extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB, failing to respond even to second line drugs such as amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin.

The remote and electronic surveillance of thousands of patients like Maria and Maya is part of an attempt to expand and enhance Directly Observed Therapy, Short-course (DOTS), whereby health care workers watch patients take their daily medications—for up to two years in the case of XDR-TB. DOTS, which undoubtedly has saved countless lives, was once believed to hold the key to eliminating the scourge of TB, but it has come in for a great deal of criticism in recent years. As well as focusing on patients who were easiest to treat, the mismanagement of DOTS in India and elsewhere has been identified as a key reason for the rise of MDR-TB, XDR-TB, and most recently, totally drug-resistant (TDR) TB. Reports of TDR-TB have now been made from as far afield as Italy, Iran, South Africa, and India and have prompted responses in the west that paint an apocalyptic future of superbugs run amok.

The Indian cases of TDR-TB were first recounted by Zarir Udwadia of the Hinduja Hospital and Research Center in Mumbai. Dr Udwadia recently described TDR-TB in India “an iatrogenic disease that represents a failure of physicians, public and private, and a failure of public health.” The idea that some illnesses are caused by medical activity isn’t a new one; nor is the notion that medical, pharmaceutical, and public health systems do a gross disservice to the world’s poor. What’s more, the triumphal claims that tuberculosis is a disease of the past and well within the realms of human control are now long gone, rightfully consigned to the dustbin labeled “medical hubris”. But if we consider the historical arc of tuberculosis prevention and therapy from the late nineteenth century onwards, Udwadia’s accusation signifies an important and necessary concession in the long-running blame game of patient “recalcitrance”, “non-compliance”, and “adherence”.

La miseria (1886). Cristobal Rojas (1857–1890)

Medical and public health authorities frequently associated high rates of tuberculosis mortality and morbidity with immoral behaviors and vice. Well into the twentieth century, when some of the social determinants of tuberculosis—such as domestic crowding, under-nutrition, and occupational exposures—were acknowledged (if not fully understood or recognized by legislation), the reasons for heightened susceptibility were often explained away by deploying racial, ethnic, and class stereotypes. As many historical studies in the United States have shown, African-Americans, Chinese, Jews, eastern Europeans, and the poor were portrayed as incorrigible, ignorant, and incapable of acting on the advice of (mostly) white, middle-class public health professionals. Often these critiques were underwritten by eugenic arguments: tuberculosis was a disease that picked off the feeble-bodied, preying on a weak urban residuum that lacked inherited resistance. Such prejudicial attitudes were replicated across the world and were particularly prevalent in the colonized parts of the globe.

Before the wide availability of anti-tuberculosis drugs in the 1940s (the first, streptomycin, was discovered in 1943), treatment options for tuberculosis were limited and of questionable efficacy. Educational campaigns aimed to change behaviors, but lacked direct focus. The emergence of sanatoria in the late nineteenth century offered new possibilities that served two purposes: isolating sufferers from the rest of the community and instilling “rules for health” that centered on diet, exercise, rest, and plenty of fresh air. However, sanatoria only treated a minority of patients with TB and an extended period of sequestration was an unrealistic option for many a working-class family’s main breadwinner. Consequently, the lion’s share of tuberculosis management was home-based and sought to replicate the sanatorium regime as much as possible. Patients were relied upon to perform the rituals of taking their own temperature and weight, regulating diet, and scheduling periods of rest and activity. Placing the responsibility for success firmly in the hands of sufferers, doctors cautioned that this sort of domesticated “preventive therapy” would fail if the patient lacked will-power, strength of character, and an even temperament. As mentioned earlier, these traits were not thought to be abundant in the types of people who usually succumbed to tuberculosis!

Not surprisingly, long-standing tropes of patient delinquency found their way into criticisms about the early versions of supervised ambulatory therapies in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Yet technological interventions such as fluorescent tracers, urine testing, and radioactive pill dispensers that were designed to overcome perceived cultural barriers to taking medicines ended up undermining patient-doctor relationships with secrecy and mistrust. By the late 1960s, direct observation seemed to be a palpable necessity, though it took almost 30 years to become WHO policy in 1995.

It is somewhat ironic that just as the structural, social, and economic barriers to patient “non-compliance” are being taken seriously by the medical mainstream, the chief medical officer for England recently invoked a dystopian scenario of a drug-resistant bacterial rampage reminiscent of the early nineteenth century. If we do indeed spiral towards some sort of pre-antibiotic dark age, then one can only hope that prejudice, discrimination, and infection can be overcome in equal measure.

Graham Mooney co-edits the journal Social History of Medicine, which has released a virtual issue on tuberculosis to mark World Tuberculosis Day on Sunday March 24, 2013. He is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. His most recent publication is ‘The material consumptive: Domesticating the tuberculosis patient in Edwardian England’ in the Journal of Historical Geography (2013).

Social History of Medicine is concerned with all aspects of health, illness, and medical treatment in the past. It is committed to publishing work on the social history of medicine from a variety of disciplines. The journal offers its readers substantive and lively articles on a variety of themes, critical assessments of archives and sources, conference reports, up-to-date information on research in progress, a discussion point on topics of current controversy and concern, review articles, and wide-ranging book reviews.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The historical arc of tuberculosis prevention appeared first on OUPblog.

March 23, 2013

World TB Day

March 2013 is a busy month. For the ladies, various countries celebrate Mother’s Days and globally International Women’s Day fell on the eighth. At the end of the month Passover and Easter are special periods of celebration for two of the world’s leading religions. Easter is a major opportunity for a chocolate fest whatever you believe. To get in shape for such overindulgence, take advantage of Europe’s National Skipping Day on the 15th of March. If you prefer something more cerebral there were World Spelling, Maths, and Book Days on the fifth, sixth, and seventh. Health and medicine get a good look-in too. Purple Day (26 March) aims to raise awareness of epilepsy and encourages its participants to dress in purple, the colour of loneliness. Kidney Day (14 March) focused this year on acute injuries to these marvellous filterers of our blood. The 24th of March is World TB Day.

The first World TB Day was held in 1982 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Robert Koch’s discovery on 24 March 1882 of the germ of tuberculosis, known today as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. On that Friday evening in Berlin, Koch read a formal research paper to a crowded medical meeting. It was published on 10 April in the Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift and after translation quickly made its way from the medical to the popular presses around the world.

Tuberculosis has been making the news ever since. We might think of the rise and almost immediate fall of Koch’s tuberculin cure. Of sanatoria built as peons to the new Internationalist architectural style, which segregated even if they couldn’t cure and were finally rendered redundant by the “miracle drugs” in the post-WWII antibiotic rush. Of BCG vaccination campaigns that gathered pace in Europe and then reached into the developing world thanks to the Scandinavians and the WHO. In recent years, in the HIV/AIDS years, the news has been dominated by the return of tuberculosis to the deprived inner-city wastelands of the developed world and its worsening effects everywhere else. Tuberculosis has gone global again: just sample the world’s press and internet news sites.

The growing problems of drug resistance have dominated the headlines, particularly the rising incidence of the worst forms of extreme drug resistance (XDR-TB). Patients infected with XDR-TB face a tortuous treatment process and the distinct possibility that treatment may fail. A study published in September 2012 highlighted the difficulties in Estonia, Latvia, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand where 44% of those enrolled showed resistance to at least one of what are termed the “second-line drugs.” These are much more expensive, have harsh side effects and require longer periods of treatment.

There have been positives too. The twenty-eight of December 2012 saw the USA’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approve bedaquiline — the first new drug against tuberculosis in more than 40 years — for use in multidrug resistant tuberculosis. Research has also indicated that vitamin D may speed the recovery of tuberculosis patients and help clear their sputum of bacteria. Ongoing research into novel vaccines or those able to augment the protection BCG offers to children has not yet yielded a usable product but has revealed vital new information about the immunological mechanisms involved. There is something to show for the US$70–100 million spent annually on research into tuberculosis vaccines.

Much more will be needed from the laboratory, better drugs and better vaccines and in the field of social welfare, alleviation of the poverty that fosters tuberculosis and the HIV/AIDS that accelerates it. History shows that tuberculosis control never mind its elimination also needs strong, committed, and comprehensive health care systems at the national level and binding agreements at the international level. 24 March 2013 will launch the second year of the World TB Day campaign that began in 2012.

Stop TB in my lifetime — what a wonderful thought.

Helen Bynum is a freelance historian of medicine and a former researcher for Wellcome. She is the author of Spitting Blood: The history of tuberculosis and Tropical Medicine in the 20th century. Together with Bill Bynum, they have edited the award winning Dictionary of Medical Biography (5 vols).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) Robert Koch. Stephen A. Schwarzman Building / George Arents Collection. Source: NYPL.

(2) World TB Day promotional image from The Stop TB Partnership website.

The post World TB Day appeared first on OUPblog.

March 22, 2013

Chinua Achebe, 1930-2013

Oxford University Press is sad to hearing of the passing of Chinua Achebe. The following is an excerpt from The New Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes, edited by John Gross.

In 1957 Achebe spent several months in London. He had already completed a draft of his first novel, Things Fall Apart, but felt that it needed further work; he took the manuscript back to Lagos, where he worked for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service, and finished revising it there:

When I was in England, I had seen advertisements about typing agencies; I had learned that if you really want to make a good impression, you should have your manuscript well typed. So, foolishly, from Nigeria, I parceled my manuscript –– handwritten, by the way, and the only copy in the whole world –– wrapped it up and posted it to this typing agency that advertised in the Spectator. They wrote back and said, ‘Thank you for your manuscript. We’ll charge thirty-two pounds.’ That was what they wanted for two copies, and which they had to receive before they started. So I sent thirty-two pounds in British postal order to these people, and then I heard no more. Weeks passed, and months. I wrote and wrote and wrote. No answer. Not a word. I was getting thinner and thinner and thinner. Finally, I was very lucky. My boss at the broadcasting house was going home to London on leave. A very stubborn Englishwoman. I told her about this. She said. ‘Give me their name and address.’ When she got to London she went there! She said, ‘What’s this nonsense?’ They must have been shocked, because I think their notion was that a manuscript sent from Africa –– well, there’s really nobody to follow it up. The British don’t normally behave like that. It’s not done, you see. But something from Africa was treated differently. So when this woman, Mrs Beattie, turned up in their office, and said, ‘What’s going on?’ they were confused. They said, ‘The manuscript was sent but customs returned it.’ Mrs. Beattie said, ‘Can I see your dispatch book?’ They had no dispatch book. So she said, ‘Well, send this thing, typed up, back to him in the next week, or otherwise you’ll hear about it.’ So soon after that, I received the typed manuscript of Things Fall Apart. One copy, not two. No letter at all to say what happened.

Interview in Paris Review, 1994

In his biography of Achebe, Ezenwa-Ohaeto quotes the novelist’s response to a friend who asked what his reaction would have been if the manuscript had been stolen: ‘he said that he would have died’.

In The New Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes, master anthologist John Gross brings together a delectable smorgasbord of literary tales, offering striking new insight into some of the most important writers in history. John Gross is the editor of The Oxford Book of Aphorisms, The Oxford Book of Essays, After Shakespeare, and many other publications. He was editor of the Times Literary Supplement from 1974 to 1981, and is currently theatre critic of the Sunday Telegraph.

The post Chinua Achebe, 1930-2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Friday procrastination: cool videos edition

Google Plus and academic productivity.

Extremely rare triple quasar found.

Fitting in with our March Madness: Atlas Edition, Oxford Bibliographies in Geography launched this week.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nonsense botany from Edward Lear. His nonsense language wasn’t bad either.

Dead authors can tweet you out of the water.

A reminder about Open Culture’s master list.

#bbpBox_311240368471556097 a { text-decoration:none; color:#306885; }#bbpBox_311240368471556097 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }Love how @March 11, 2013 6:21 pm via TweetDeck Reply Retweet Favorite Open Culture

Be thankful someone hasn’t dedicated a book to you.

One six-second drum loop versus the world.

Research librarians versus scholars.

#bbpBox_311514120983826433 a { text-decoration:none; color:#0084B4; }#bbpBox_311514120983826433 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }#AnimatedGIF showing the time-evolution of the four-lepton mass distribution in the search for the SM #Higgs boson: https://t.co/i9uJ1uQi69

March 12, 2013 12:28 pm via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

CMS Experiment CERN

March 12, 2013 12:28 pm via web

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

CMS Experiment CERNThe most extraordinary man to play Test cricket (h/t The Millions)

Lonely Planet Guide Saves Lives of Three Boys.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The taste of Earl Grey isn’t the only complex thing about it. It’s etymology is a little murky.

Presenting the PULP-O-MIZER. (h/t The Millions)

The women of Russian writers’ lives. (h/t The Millions)

Click here to view the embedded video.

Emir O. Filipović on cats and medieval manuscripts.

Click here to view the embedded video.

For the New Yorkers/Tumblr enthusiasts: May is Tumblr month on Thirteen.

It’s okay to return your library books late if they were bombing.

If you want to apply for this NYPL internship, please also apply for a social media intern position at OUP.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Diversity, librarianship, and library resources.

Where Some Like It Hot was set.

Blind your editors with poor animations.

#bbpBox_312516815039365120 a { text-decoration:none; color:#0084B4; }#bbpBox_312516815039365120 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }The books in your room are the only thing stopping your DVDs from attacking you while you sleep.

March 15, 2013 6:53 am via Twitter for iPhone

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

WaterstonesOxfordSt

March 15, 2013 6:53 am via Twitter for iPhone

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

WaterstonesOxfordStWhen art and science student interact, they create some fascinating projects.

Google Reader is leaving us. Joshua Rothman reflects.

#bbpBox_310514403659370498 a { text-decoration:none; color:#7DA348; }#bbpBox_310514403659370498 a:hover { text-decoration:underline; }Dear spammers: I consider it highly unlikely that a 1400 yr old Cathedral is in a compromising photo which has caused you to laugh out loud

March 9, 2013 6:16 pm via TweetDeck

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Ripon Cathedral

March 9, 2013 6:16 pm via TweetDeck

Reply

Retweet

Favorite

Ripon CathedralTwo academics discuss the pros and cons of using Twitter as a learning tool.

What is the origin of the word scalawag?

Most of us hate those one line ‘Thank you’ emails.

Incredibly rare valkyrie figure found.

LA County just got a bit better.

Archaeologists are trying to put together funding for another exploration of the Antikythera wreck.

Alice Northover joined Oxford University Press as Social Media Manager in January 2012. She is editor of the OUPblog, constant tweeter @OUPAcademic, daily Facebooker at Oxford Academic, and Google Plus updater of Oxford Academic, amongst other things. You can learn more about her bizarre habits on the blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Friday procrastination: cool videos edition appeared first on OUPblog.

Antisocial personality disorder: the hidden epidemic

It may be hard to believe, but one of the most common and problematic mental disorders is ignored by the public and media alike. People — and reporters — breathlessly talk about depression, substance abuse and autism, but no one ever talks about antisocial personality disorder. Why?

Though better known as sociopathy, antisocial personality disorder, or ASP, affects up to 8½ million Americans and there is no cure, nor are there any good treatments. Psychiatrists like me who are interested in this disorder tend to be ignored and our concerns marginalized. The patients themselves can be difficult, and even unpleasant, and that limits interest. It is hard for people to be sympathetic toward those who tend not to arouse our concern. There are no poster children to point to.

Few mental health professionals are interested in the disorder and some run when a colleague tries to refer an antisocial patient to them. ASP is rarely discussed in medical schools, and few researchers take it on as a cause. Most telling, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the government’s premier medical research organization, funds a grand total of two projects in which the term “antisocial” appears in the title. By contrast, the NIH funds hundreds if not thousands of studies on more conventional mental health topics such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorders, and autism. How are we — as mental health professionals — to make headway in treating and preventing this disorder when the government does not lead the way?

First, let us consider what ASP is. Briefly, it is a disorder of chronic or serial misbehavior that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood, usually persisting throughout a person’s life. These are the rule breakers who see fit to violate society’s conventions. As children they fight with others, lie to their parents, and steal from the corner store. As adults, they abuse their partners or spouses, are irresponsible toward their children, and some are criminal. In the worst cases, some commit heinous acts of violence. Few of its sufferers are women, as it is predominately a man’s disorder. And sufferer is not the right word, because most antisocial persons do not “suffer” in the usual sense since they rarely believe anything is wrong. Their behavior is not the problem; society and its tiresome rules are the problem.

First, let us consider what ASP is. Briefly, it is a disorder of chronic or serial misbehavior that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood, usually persisting throughout a person’s life. These are the rule breakers who see fit to violate society’s conventions. As children they fight with others, lie to their parents, and steal from the corner store. As adults, they abuse their partners or spouses, are irresponsible toward their children, and some are criminal. In the worst cases, some commit heinous acts of violence. Few of its sufferers are women, as it is predominately a man’s disorder. And sufferer is not the right word, because most antisocial persons do not “suffer” in the usual sense since they rarely believe anything is wrong. Their behavior is not the problem; society and its tiresome rules are the problem.

How did we arrive at this point? First, there is the lack of visibility. ASP is not on the public’s radar screen. While known to psychiatrists and psychologists for nearly 200 years in one form or another, few mental health professionals bother to make the diagnosis or to even make referrals for its evaluation or treatment. The public misunderstands the term antisocial, believing the disorder to relate to shyness, when it really relates to bad behavior directed against society. Finally, researchers tend to go where the money is. Since the NIH directs few funds to investigate ASP, why would an investigator study it? Take autism as an example. The amount of research exploded within the last decade when it became clear that the government was interested in the disorder. That could happen with ASP if the NIH changed its tune. Despite this deliberate indifference, over the past 50 years researchers have — mostly on their own time and money — consistently shown it to be one of the most heritable of disorders and to have a clear neurobiological basis.

Why should I and others care? Though under the radar, ASP isn’t going anywhere. It will continue — over time — to cost us billions and billions though its direct and indirect costs associated with law enforcement and criminal justice. Nearly all of us are victims of an antisocial person’s misdeeds; we fear them and even grapple with the disorder in our families. Now more than ever, psychiatry and society have the means to explore why some people turn bad, but progress will continue to accrue slowly until we begin to see ASP more clearly and commit ourselves to doing something about it.

Understanding the scope of ASP and coming to grips with it requires time and money. The NIH and other agencies must change their tune about funding ASP research and its many facets, particularly crime and violence. Priorities should include wide-reaching projects to explore its origins and search for methods to change its course. Geneticists must continue to investigate genes that might predispose individuals to ASP and determine how they function. Neuroscientists should work to pinpoint brain regions linked to antisocial behavior while identifying the neurophysiological pathways that influence its expression. Mental health professionals must overcome their own resistance to working with antisocial persons in order to develop new treatments. Last, we must focus attention on the group at highest risk of developing ASP: children with antisocial behavior. Improved understanding of their home life and social environment may lead to more effective interventions that may prevent ASP from developing. By treating and possibly preventing ASP, we can have a broad impact that ripples through society, thereby helping to reduce spousal abuse, family violence, and criminal behavior.

Donald W. Black, MD, is the author of Bad Boys, Bad Men: Confronting Antisocial Personality Disorder (Sociopathy), Revised and Updated Edition. He is a Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City. A graduate of Stanford University and the University of Utah School of Medicine, he has received numerous awards for teaching, research, and patient care, and is listed in “Best Doctors in America.” He serves as a consultant to the Iowa Department of Corrections. He writes extensively for professional audiences and his work has been featured in television and print media worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dissolving fractured head. Photo by morkeman, iStockphoto.

The post Antisocial personality disorder: the hidden epidemic appeared first on OUPblog.

In the path of an oncoming army: civilians in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

The Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival 2013 is in full swing, welcoming thinkers and writers from across the globe to our wonderful city of Oxford. We’re delighted to have over thirty Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year! OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Oxford this year, you won’t miss out on all the action. Don’t forget you can also follow @oxfordlitfest and check the event schedule here.

Mike Rapport will be giving a free talk at the Oxford Literary Festival on Saturday 23 March 2013 at 1.15 p.m. to talk about The Napoleonic Wars. The Very Short Introductions ’soapbox’ talks will be running twice a day during the festival.

By Mike Rapport

Modern wars, someone once wrote, are fought by civilians as well as by armed forces. In fact, it is of course a truism to say that civilians are always affected by warfare in all periods of the past — as the families left behind, by the economic hardship, by the horrors of destruction, plunder, requisitioning, siege warfare, hunger, and worse. The involvement of civilians in modern wars, however, became more intense because, with the advent of ‘total war’, belligerent states began to mobilise the entire population and material resources of the country. The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars were an early example of the ways in which a modern war could grind millions of people up in its brutal cogs, whether as conscripts in the firing lines of Europe’s mass armies and navies, or as civilians caught in the path of the oncoming battalions and trapped in the crossfire of the fighting itself. At the Oxford Literary Festival on 24 March, I will be speaking about the non-combatants who, in one way or another, found themselves entangled in the wars.

Civilians were of course victims. Four years ago Karen Hagemann published a fine article on the civilian experience of the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, the largest battle in European history before 1914. The local people started as horrified onlookers, as maimed, sick French troops retreated into the city to find treatment in makeshift military hospitals But soon the fighting arrived on their streets and doorsteps and they themselves became the victims. First, they suffered economically with the pillaging and requisitioning of tools, furniture, food and livestock. Then they found themselves under fire, huddling in churches and cellars to shelter — sometimes in vain — from the bursting shells, or they fled the carnage, carrying what they could on carts and wheelbarrows and dragging their terrified children along with them.

Yet this was a ‘people’s war’ not only because the conflict may have killed at least one million civilians (and very likely many, many more). It was also a ‘people’s war’ because the civilian population of all the belligerents mobilized behind the war effort. Economies were reoriented into supplying armies and navies, while the recruiting-sergeant and press-gang became all-too-familiar sights across Europe. In revolutionary France in 1793, the ‘mass levy’ of the entire population for the war effort gave men, women and children explicit roles to play in the mobilisation of all the nation’s resources for the sole purpose of fighting the war. Yet civilians also voluntarily engaged in the prosecution of the conflict. In France in the 1790s, communities collected money and valuables and presented them to the government as ‘patriotic donations’. Women played a pivotal role: in Germany, a ‘Women’s Association for the Good of the Fatherland’ raised money and collected valuables for the Prussian war effort against France in 1813: it boasted some 600 branches by 1815. In Britain, women raised subscriptions for the wounded, the widowed and collected materials and clothing for the troops: there were, again, hundreds of such organisations. In Spain, men and women joined bands of guerrillas to fight and plunder the French, although in many cases such actions appear to have been little different from banditry, since Spaniards suffered from these depredations too.

Yet it all shows that people were not simply coerced. They were stirred by propaganda fed to them by governments and by a media trying to convince them that the war was, variously, a struggle for survival, for liberty, for religion, for monarchy, or for the Emperor. The people themselves played a role in shaping the propaganda, in defining what the war was about. With an expansion in literacy in the eighteenth century, such popular support would have been impossible without an interaction between public opinion and governments. In the varieties and intensity of the civilian experience, the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars are a chilling anticipation of the ‘total wars’ of the twentieth century.

Dr Mike Rapport is Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Stirling. He is the author of Nationality and Citizenship in Revolutionary France: The Treatment of Foreigners 1789-1799 (OUP, 2000), The Shape of the World: Britain, France and the Struggle for Empire (Atlantic, 2006), 1848, Year of Revolution (Little, Brown, 2008), and The Napoleonic Wars: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2013).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with Very Short Introductions on Facebook, and OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Victory declaration after the battle of Leipzig, 1813 [Public Domain} via Wikimedia Commons

The post In the path of an oncoming army: civilians in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars appeared first on OUPblog.

Witchcraft: yesterday and today

The Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival 2013 is in full swing, welcoming thinkers and writers from across the globe to our wonderful city of Oxford. We’re delighted to have over thirty Oxford University Press authors participating in the Festival this year! OUPblog will be bringing you a selection of blog posts from these authors so that even if you can’t join us in Oxford this year, you won’t miss out on all the action. Don’t forget you can also follow @oxfordlitfest and check the event schedule here.

Malcolm Gaskill will be appearing at the Oxford Literary Festival on Saturday 23rd March 2013 at 5:15 p.m. to provide a very short introduction to Witchcraft. This event is free to attend.

By Malcolm Gaskill

I’m looking at a photo of my six-year-old daughter wearing her witch costume — black taffeta and pointy hat — last Halloween. Our local vicar marked the occasion by lamenting in the parish magazine this ‘celebration of evil’. All Hallows’ Eve, the night when traditionally folk comforted souls of the dead, is not, in fact, evil, but did once have evil in its margins. Spirits on the loose might be bad as well as good, and for humans to manipulate them was witchcraft. The perception of evil, concentrated in the figure of the witch, was once powerfully real. Kate’s fancy dress character, however winsome, has a profound cultural connection to a terrifying dimension of the past and, as we’ll see, the present too.

night when traditionally folk comforted souls of the dead, is not, in fact, evil, but did once have evil in its margins. Spirits on the loose might be bad as well as good, and for humans to manipulate them was witchcraft. The perception of evil, concentrated in the figure of the witch, was once powerfully real. Kate’s fancy dress character, however winsome, has a profound cultural connection to a terrifying dimension of the past and, as we’ll see, the present too.

Myths about the ‘witch-craze’ abound. One version has it that millions of medieval women were persecuted by the church, aided by the prejudices of benighted peasants. Witchcraft accusations, we like to think, were a good way for people stupider than us to get rid of people they didn’t like or chose to scapegoat to explain misfortune in an unscientific age. This picture is essentially false. The ‘witch-hunt’ resulted in the execution of around 50,000 people (a fifth of them men), mostly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. A key development at that time was the rise of the state, with its laws and tribunals, and it was this, far more than the Catholic church, which made witch-hunting possible. Insofar as religion was involved, it was the ferocious energy unleashed by the Protestant Reformation that did most harm. Finally, if witchcraft was a pretext to bump off enemies, it wasn’t a very good one: about half of all suspicions — the few that made it into court — ended in acquittals. In England, three-quarters of all trials disappointed the accusers.

And this was no cultural dark age. These were the days of Shakespeare, Milton and Newton — no longer the Middle Ages. It was the early modern period with its new sciences and technologies, literary and artistic genius, explosions of print and commerce, global discoveries, and new ways of seeing and feeling. It’s more comfortable to think that witch-hunts preceded the Renaissance, but they didn’t, and if we look closely we ca n see why. The search for truth, and growing human confidence to find it, underpinned the inquisitorial legal process, replacing blind faith in judicial ordeals and unlimited torture. Statutes against witches and the will to use them, combined with social and economic tension caused by demographic change, largely explain the rise of witch-trials after 1500. Witches were made officially real by law and reason long before the same law and reason made them unreal by undermining the evidence on which they were tried.

n see why. The search for truth, and growing human confidence to find it, underpinned the inquisitorial legal process, replacing blind faith in judicial ordeals and unlimited torture. Statutes against witches and the will to use them, combined with social and economic tension caused by demographic change, largely explain the rise of witch-trials after 1500. Witches were made officially real by law and reason long before the same law and reason made them unreal by undermining the evidence on which they were tried.

What is remarkable, even in the heyday of witchcraft prosecutions, was just how much restraint was shown in most places, at most times. There was no witch-holocaust because communities and authorities alike were preoccupied with order, and condemning innocent people did not serve that end. England had a few years during the Civil Wars when settled life was disturbed, puritan magistrates and clergy became powerful, and the normal administration of justice was interrupted. Once restraints were removed, what followed was the most savage witch-hunt in English history, with perhaps three hundred East Anglian women and men accused, and a third of them executed.

But throughout Europe and colonial north America, such events were the exceptions that proved the rule, the rule being that witch-crazes were uncommon and undesired by most. During our Halloween fun, it’s worth remembering both those who died and those who were sufficiently sceptical and fond of communal harmony to keep mass witch-hunts at bay. And we might also remember that the distance between us and such outrages is not just a few hundred years, but a few hundred miles.

On 6 February this year Kepari Leniata, a 20-year-old mother of two living in the highlands of Papua New Guinea, was accused of bewitching a six-year-old boy to death. Villagers stripped and bound her, then dragged her to a rubbish dump where she was tortured with hot irons until she confessed. The police arrived, but were held back by locals who doused Leniata in petrol and burned her alive. The UN human rights office explained that this was just the latest of numerous lynchings, each conforming to a pattern found in many parts of the developing world where witch-beliefs are strong and uncontained by law or authority.

The persecution of witches in any age says a lot about the society that allows it or cannot resist it — its structures, institutions, and social organization of power. If we in the West have successfully neutralized our most deadly fears and packaged our persecutions as harmless trick-or-treating, then perhaps we should be shouldn’t be too worried about celebrating evil. Recent events in Papua New Guinea suggest that we barely know the meaning of the word.

Malcolm Gaskill is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of East Anglia. His books include Hellish Nell: Last of Britain’s Witches (2001), Witchfinders: a Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy (2005), and Witchcraft: a Very Short Introduction (2010).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Photo provided by Malcolm Gaskill. Not to be used without express permission; the execution of Ann Hibbins on Boston Common in 1656 [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The post Witchcraft: yesterday and today appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers