Is competition always good?

Wow! That is what my university’s former football coach wanted to hear from prospective student-athletes when touring the new $45 million football practice facility. Parts of my university need repair. Departments face resource constraints. But the new practice facility was to set the standard in the university’s fierce competition for talented recruits. So our former coach led reporters through the planned 145,000 square-foot building, with its grand team meeting room, custom-designed chairs, hydro-therapy room, restaurant, nutrition bar, and lockers equipped to charge iPads and cellphones. But as the tour concluded, our coach observed that several rival universities, upon seeing our planned facility, were planning even more expensive training facilities. As our rivals spend millions on elaborate facilities, none of the universities have a sustained competitive advantage. And other student needs remain unmet.

Competition is ordinarily viewed as good. It is, after all, the backbone of most developed countries’ economic policies. Promoting competition is broadly accepted as the best available tool for promoting economic well-being. Competition can yield lower prices, better quality, more choices, innovation, greater efficiency, increased productivity, and additional economic development and growth. Competition has its social and moral virtues, such as promoting individual initiative, liberty, and free association. Not surprisingly, competition can take a religious quality, especially among antitrust enforcers. They regularly try to protect the public from harmful special interest legislation, premised on complaints of excess competition.

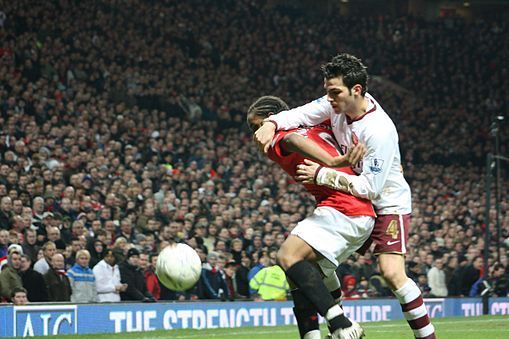

Competition, although seen as good, is not pervasive. At times the laws and informal norms stress cooperation, rather than competition. We don’t want parishioners, after all, competing for pews, or children competing for their parents’ affection. Some areas aren’t subject to market competition (e.g. human organs) or are exempt from competition laws (e.g. labor). Even though competition is generally seen as good, not all forms of competition are necessarily good. So we distinguish between fair and unfair means of competing — to promote the soccer player’s artful pass while punishing the scoundrel’s rough elbow. But for most commercial activity, competition on the merits is the presumed policy. It is the glue that binds our economy.

While watching my university’s football coach tour the state-of-the-art facilities, I wondered whether competition always benefits society. When does competition devolve into its pejorative synonyms: arms race and race-to-the-bottom? When is competition the problem’s cause, rather than its cure? These questions expose competition policy’s blind spot. Few within antitrust circles ask these questions. Instead, their elixir often is more, rather than less, competition.

Interestingly, an economist examined over a century ago these questions. Competition, Irving Fisher found, works to society’s benefit under two assumptions: first, when each individual can best judge what serves his interest and makes him happy; and second, when individual interests are aligned with collective interests. These two assumptions often are valid; competition, as a result, reliably delivers. But when these assumptions don’t hold, as recent developments in the economic and psychology literature show, competition can worsen the problem. One scenario is where firms effectively compete to exploit overconfident consumers with imperfect willpower (think credit cards). Rather than compete to help consumers obtain or find solutions for their imperfect willpower, firms instead compete in devising better ways to exploit consumers.

A second scenario is where individual and group interests diverge. Competition benefits society when individual and group interests and incentives are aligned (or at least don’t conflict). But when individual interests diverge from collective interests, as in the case of testosterone, the competitors and society are worse off. Wall Street traders, the press reports, are boosting their testosterone levels. One study found that traders, with higher morning testosterone levels, were likelier to earn more profits that day. Higher testosterone levels can increase the traders’ appetite for risk and fearlessness. So traders, weighing the benefits and risks, can rationally decide to boost their testosterone levels to gain a relative competitive advantage (or at least not be competitively disadvantaged against higher testosterone traders). However, as other traders inject testosterone, the traders no longer enjoy a relative competitive advantage. They and society are collectively worse off.

We saw this race-to-the-bottom before the economic crisis. With the expansion of Fitch Ratings, the competitive pressures on the two entrenched ratings agencies increased. Their cultures changed. They increasingly emphasized greater market share and short-term profits. To gain a relative advantage, they lowered their rating requirements. Their ratings quality deteriorated. As the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission found, Moody’s alone rated nearly 45,000 mortgage-related securities as AAA. In contrast, in early 2010, only six private-sector companies were rated AAA. So too nations compete for a relative advantage by relaxing their banking, environmental, safety, and labor protections. Their competitive race-to-the-bottom ultimately leaves them and their citizens collectively worse off.

So is competition in a market economy always good? If the answer is no, a separate issue is whether we should allow private parties to deal with these types of failures or whether legislation is required. Once we recognize that market competition produces at times worse results, the debate shifts to whether the problem of suboptimal competition can be better resolved privately (by perhaps relaxing antitrust scrutiny to private restraints) or with additional governmental regulations (which raises issues over the form of regulation and who should regulate).

So when you hear the policymaker’s refrain of making markets more competitive, competition likely is the solution. But as football coaches, Wall Street traders, ratings agencies, and nations realize, increasing competition at times worsens, rather than cures, the problem.

When he joined the University of Tennessee in 2007, Prof. Maurice E. Stucke brought 13 years of litigation experience as an attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and Sullivan & Cromwell. A Fulbright Scholar in 2010-2011 in the People’s Republic of China, he serves as a Senior Fellow at the American Antitrust Institute, on the boards of the Academic Society for Competition Law and the Institute for Consumer Antitrust Studies, and as one of the United States’ non-governmental advisors to the International Competition Network. His scholarship has been cited by the U.S. courts, the OECD, competition agencies, and policymakers. You can read his article “Is competition always good?” in the Journal of Antitrust Enforcement.

The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement is a new launch journal from Oxford University Press in 2013. All content is freely available online for a limited time and papers published ahead of the first print volume (April 2013) are available online now. The Journal of Antitrust Enforcement provides a platform for leading scholarship on public and private competition law enforcement, at both domestic and international levels. The journal covers a wide range of enforcement related topics, including: public and private competition law enforcement, cooperation between competition agencies, the promotion of worldwide competition law enforcement, optimal design of enforcement policies, performance measurement, empirical analysis of enforcement policies, combination of functions in the competition agency mandate, and competition agency governance. Other topics include the role of the judiciary in competition enforcement, leniency, cartel prosecution, effective merger enforcement, competition enforcement and human rights, and the regulation of sectors.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: (1) The University of Tennessee Pride of the Southland Marching Band performs pregame at the UT vs. California football game. Photo by Jordan3757, Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

(2) Arsenal’s Cesc Fàbregas (white shirt) duels with Anderson of Manchester United. Photo by Gordon Flood, Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is competition always good? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers