Oxford University Press's Blog, page 964

March 27, 2013

Monthly etymological gleanings for March 2013

This has been a good month for the “gleanings”: I have received many questions and many kind words through the blog and privately. My usual thanks to those who read and react.

Idioms: dictionaries.

Our Polish correspondent wants to know where he can find a dictionary giving the origin of English idioms. I can list several such reference books but should first “issue a warning.” The origin of an idiom is often harder to ascertain than the origin of a word. Idioms tend to appear from thin air, and all we know about many of them is the date of their first attestation in print. To exacerbate matters, as journalists like to say, those who compile etymological dictionaries of idioms refrain from saying where they found their information (from whom they copied it), but without references one should take their pronouncements with a whole saltcellar at one’s side. Many compilations are called Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (after Ebenezer C. Brewer). If published by reputable presses, they are worth consulting. Familiar quotations, which often become idioms, have been investigated very well, and dictionaries of them are helpful.

Try Linda and Roger Flavell, Dictionary of Idioms (several editions and reprints). Charles Funk was the prolific author of superficial books on “curious word origins” (words and idioms are given there pell-mell). Something can be found in Webb B. Garrison, Why Say It (another moderately reliable source). I occasionally open Dictionary of Word Originsby Jordan Almond; Why Do We Say… by Nigel Rees; To Coin a Phrase by Edwin Radford and Alan Smith; and the 1937 book Everyday English Phrases by J.S. Whitebread. In the past, the volumes of Notes and Queries (most of them are now available online) contained discussion of astounding local idioms (in addition to the more common ones). People offered their suggestions, and I am sorry that no one has put together and tabulated this precious material. The idioms (“phrases”) in N&Q can be easily retrieved through the indexes. But to repeat: Don’t take anything you will find anywhere for the ultimate truth.

Idioms: salad days.

The question about this idiom has been asked and answered countless times. It is known that my salad days first appeared in print in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra (1606) and meant “the time of one’s youthful inexperience” (rather than “the peak of my career,” as in Modern American English). Salad apparently referred to one’s green years (cf. The Green Years, a novel by Archibald J. Cronin). But it is not known whether Shakespeare coined this bold metaphor or whether it was current in his time (the second alternative is less likely).

Shucks!

In distinction from those who commented on my recent discussion of the exclamation shucks!, I don’t believe that it has anything to do with the F-word (even though the taboo origin seems “obvious” to one of our correspondents). When taboo forms come up, the first consonant is usually preserved (compare Gosh for God, Land for Lord, bally for bloody, and so forth), so that focks, ficks, or something similar might be expected. The plural also speaks against the taboo derivation. In f— it or f— you, there is no s. From a morphological point of view, shucks! belongs with jiggers! (and it even resembles it: just devoice the consonants and you will get shickers!). Finally, shucks expresses embarrassment or disappointment, not anger or frustration.

Sound symbolism: wr-.

Does only English use the group wr- for designating twisting of all kinds? I will confine myself to a nonbinding general statement. Onomatopoeia seems to be near universal. All over the world, groups like gr-, kr-, br- make people think of various noises (grinding, raucous cries, breaking, rupture, and the like), but sound symbolism is language-specific, especially when it comes to consonants. (Vowels are more obviously “symbolic”: the tit for tat situation, with short i denoting a small object and short a a big one, has been observed in numerous unrelated languages.) Some associations probably arise by chance, that is, thanks to statistics. For example, so many English words for smooth surfaces and gliding and glowing begin with gl- that gl- acquired a life of its own, and neither gloom nor gloaming can ruin the connection. Also, we often detect symbolism in retrospect. For instance, we know what collywobbles means, and it begins to seem that the sound shape of collywobbles suits the word’s meaning in the best way possible.

On the same note: cur.

Cur is possibly sound imitative (kr-kr). In English, the word may be of Scandinavian descent, as evidenced by the Scandinavian verbs kurra and kurre for screeching, cooing, etc. Chirp, screech, and scream are close to kurr-.

Twerp and twill.

I was very pleased to learn from Stephen Goranson that twerp was already current in 1917. This confirms my suspicion that the word does not go back to a proper name. And yes, of course, tw- in twill is related to tw- in two. I paired twill with tweed because they so well go together. But thief does not belong with them. The word is of unknown origin, and I may devote a special post to it.

“Vikings” and “herring” (as opposed to cabbages and kings).

(1) If víking was pronounced with a short vowel, wouldn’t the word have been spelled with -kk-? Probably not, especially in Old Norwegian and Old Icelandic, in which kk seems to have been preaspirated, that is, to have had the value of hk(k). For example, in Modern Icelandic, rekja “unravel” (or its homonym rekja “humidity, moisture; rain; dew”) has a long vowel, while rekkja “bed” has a short one (and preaspirated k), but in Old Icelandic both had short e and were distinguished only by consonant length. It should also be remembered that medieval spelling is inconsistent. Thus, in Old Icelandic, an accent mark over a vowel designated length, but one cannot always rely on the form attested in manuscripts. The evidence of modern languages sometimes carries more weight for reconstructing the pronunciation of the past.

(2) The Scandinavian word for “herring.” Both sil and sild exist, and, assuming that they are related (a safe assumption),-d must be a suffix, but its exact meaning remains unclear.

“Dance” in the Romance languages.

Spanish has both danzar and bailar. Likewise, Italian has danzare and ballare. Old French had baller (extant in Modern French as baller “make merry; dance,” now obsolete alongside danser). As always, when close synonyms coexist, they divide their spheres of influence and try to gain the entire available territory.

Wollt ihr den totalen Krieg?

This is the famous catchphrase by Goebbels (1943; “Do you want a “total,” that is, “an all-out, all-embracing, all-pervading” war, “war and nothing else”?). Our Danish correspondent wonders why there is no infinitive (haben “have”) in the phrase and quotes sentences in Modern Danish in which ville is also used “absolutely,” without an infinitive, and means “want, prefer”or something similar. This usage seems natural to me. In German, wollen is quite possible without an infinitive. I am not sure whether phrases like du hast es gewollt “you wanted it” arose under French influence (compare the now proverbial French tu l’as voulu, George Dandin), but something like ob man will oder nicht “whether one wants it or not” (with an exact analog in Danish) must be a hundred percent native. In older texts, “be,” “have,” and “go” were regularly omitted after modal verbs. Old Icelandic is especially typical in this respect.

An etymologist reborn

Give up versus give up on.I fully agree with Debbie Allen’s distinction between the two. Indeed, we give up things when we relinquish them for good, while giving up on something more often hints at inevitable sacrifices. That is why it is impossible to give up on the ghost: one either has this commodity or not.

Personal.

(1) Brianne Hughes likes my blog and says that she would be glad to give me a hug if we met but fears that it would be improper. Oh, quite proper! I often hear that callous men objectify women, and shudder, but I, not being a woman, would love being objectified. Also, I heard our neighbor once complain that her teenage son was too much in demand. “Girls exploit him!” she whimpered. Since I knew very well how the young man was used by the opposite sex, it occurred to me that some forms of exploitation might be welcome. One of the basic principles of dialectics is that truth is always concrete.

(2) Anne Morgan does not have much trust in incarnation but hopes that, if she is ever reborn, she will be an etymologist. I too have a confused notion of (re)incarnation, except that I fear reemerging as a woodpecker, for in this case I will continue my present occupation, which is pecking away at hard wood in search of edible grubs.

Spring has come (congratulations!), and the seventh year of this blog began with it.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus principalis , chromolithograph, 1888. Birds of North America by Jacob H. Studer, John Graham Bell, Frank Chapman, Theodore Jasper, (artist). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymological gleanings for March 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Female characters in the Narnia series

What can the reader expect of the Chronicles of Narnia series to reveal about Christianity? According to Former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, the Narnia series serves as a refreshing take on what it means to experience the divine in daily life. Christianity is portrayed in a more humanizing light through C.S. Lewis’s imaginative interpretation of Christian doctrine. In the following excerpt from The Lion’s World: A Journey into the Heart of Narnia, Williams examines the portrayal of female characters in the Narnia series.

The charges of sexism or misogyny, though, are harder to counter. Even a very sympathetic commentator like Stella Gibbons (author of Cold Comfort Farm and a rather unexpected admirer of Lewis) complains that Lewis disliked “women who have entered rather boldly into the world that men have reserved for themselves. The domesticated, fussy, kind woman gets an occasional pat on her little head — (Mrs Beaver in The Lion, Ivy Maggs in That Hideous Strength).” Much feeling has been generated by the banishment of Susan from Last Battle because “She’s interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations. She was always a jolly sight too keen on being grown-up” (Last Battle Ch. 12 , p. 741). Susan has forgotten Narnia apparently with the onset of puberty, and this has led some to conclude that she is “damned” for reaching sexual maturity.

This is unfair. We have already met (in The Horse) a mature Narnian Susan, courted by the heir to the Calormene throne. Her failure is not growing up. It is the denial of what she has known, rooted in her “keenness” not to grow up but to be grown-up, a very different matter. “It is the stupidest children who are most childish and the stupidest grownups who are most grown-up,” we are told in Chapter 16 of The Silver Chair (p. 661). Susan is guilty of what Edmund in The Lion is initially guilty of, no more and no less, which is the refusal to admit the reality of Narnia when you have actually lived there. In The Lion this denial is one of the things that open the door to Edmund’s more serious treachery (so it is hardly a gender-specific matter); the issue is precisely that truthfulness which again and again — as we shall see — emerges as the central moral focus of the Narnia stories. And of course Susan’s longer-term future as an adult in “our” world is left entirely open. Lewis himself wrote in 1960 to a young reader distressed by Susan’s defection that he was reluctant to write the story of Susan’s rediscovery of Narnia.

Not that I have no hope of Susan’s ever getting to Aslan’s country, but because I have a feeling that the story of her journey would be longer and more like a grown-up novel than I wanted to write. But I may be mistaken. Why not try it yourself?

Nor does Lewis in fact give us a series of weak or ill-defined female characters. Lucy’s courage and determination are a constant theme in the books where she appears. In Prince Caspian, when Edmund says “’to Peter and the Dwarf’ that girls ‘can never carry a map in their heads’”, it is Lucy who retorts “That’s because our heads have got something inside them” (Prince Caspian Ch. 9 , p. 370) and ends the conversation. In Dawn Treader Chapter 8, Lucy again castigates her male companions for being such “swaggering, bullying idiots” when Edmund and Caspian quarrel over who will be overlord of the island where water magically turns things to gold (p. 484). Aravis in The Horse is as forceful and intelligent a figure as any. It is true enough that Lewis seems to be all too ready to deal with the extremes of the spectrum where female characters are concerned — witch-queens and nannies. But in between there is rather more than some readers have noticed of ordinary female intelligence; and the depiction of male jostling for position among both boys and men, and the lethal consequences of this male pride, is none too flattering. It will not do to see Lewis as a simple misogynist. It is tempting to say that the further he gets away from theorizing about gender characteristics, the better he is in depicting women; the problem with the ill-starred Jane in That Hideous Strength is — as Stella Gibbons once again observes — that she has to carry an uncomfortable weight of theory in the very complex plot of that strange work.

Nor does Lewis in fact give us a series of weak or ill-defined female characters. Lucy’s courage and determination are a constant theme in the books where she appears. In Prince Caspian, when Edmund says “’to Peter and the Dwarf’ that girls ‘can never carry a map in their heads’”, it is Lucy who retorts “That’s because our heads have got something inside them” (Prince Caspian Ch. 9 , p. 370) and ends the conversation. In Dawn Treader Chapter 8, Lucy again castigates her male companions for being such “swaggering, bullying idiots” when Edmund and Caspian quarrel over who will be overlord of the island where water magically turns things to gold (p. 484). Aravis in The Horse is as forceful and intelligent a figure as any. It is true enough that Lewis seems to be all too ready to deal with the extremes of the spectrum where female characters are concerned — witch-queens and nannies. But in between there is rather more than some readers have noticed of ordinary female intelligence; and the depiction of male jostling for position among both boys and men, and the lethal consequences of this male pride, is none too flattering. It will not do to see Lewis as a simple misogynist. It is tempting to say that the further he gets away from theorizing about gender characteristics, the better he is in depicting women; the problem with the ill-starred Jane in That Hideous Strength is — as Stella Gibbons once again observes — that she has to carry an uncomfortable weight of theory in the very complex plot of that strange work.

Rowan Williams is Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge. A poet and theologian, he is the former Archbishop of Canterbury and Primate of All England. He is the author of The Lion’s World: A Journey into the Heart of Narnia, published this month in the United States by Oxford University Press USA.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Skandar Keynes, Ben Barnes and Georgie Henley in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Copyright 20th Century Fox and Walden Media, LLC. Used for the purposes of illustration.

The post Female characters in the Narnia series appeared first on OUPblog.

March 26, 2013

Soldier, sailor, beggarman, thief

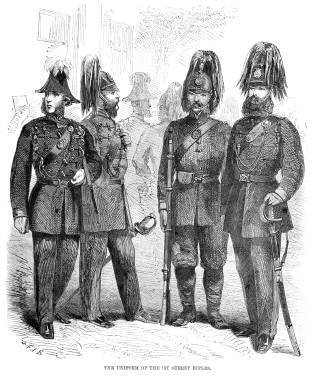

Soldiers, sailors, and airmen reflect the societies from which they come. We should not be surprised therefore if they reflect vices as well as virtues; yet there is often hostility to anyone picking up on the vices of service personnel. When putting together my recent book, I was denied permission to use a quotation from the memoir of an infantry lieutenant about theft by members of his platoon in Germany in 1945. It might be asked: why was the information put in the memoir if it was not to be read? It was not always thus.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries British soldiers were commonly looked upon as dangerous, dissipated and, at least when stationed at home, drunk. It was also feared that demobilisation at the end of a war led to men trained in the use of weapons and brutalised by battlefield experience would turn to violence and robbery rather than the manual labour that was thought to suit their social origins. There was a slight respite in these fears when Britain became and armed nation in the wars against the French Revolution and Napoleon, though this was subsequently offset by garbled accounts of the Duke of Wellington’s description of his men as ‘the scum of the earth enlisted for drink.’ Press reports of the horrors of the Crimean War brought a degree of sympathy for the soldiery and some amelioration of the suspicions about soldiers, yet at the end of the century Rudyard Kipling could contrast the ‘thin red line of ‘eroes when the drums begin to roll’ and the publican’s: ‘We serve no red-coats here.’

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries British soldiers were commonly looked upon as dangerous, dissipated and, at least when stationed at home, drunk. It was also feared that demobilisation at the end of a war led to men trained in the use of weapons and brutalised by battlefield experience would turn to violence and robbery rather than the manual labour that was thought to suit their social origins. There was a slight respite in these fears when Britain became and armed nation in the wars against the French Revolution and Napoleon, though this was subsequently offset by garbled accounts of the Duke of Wellington’s description of his men as ‘the scum of the earth enlisted for drink.’ Press reports of the horrors of the Crimean War brought a degree of sympathy for the soldiery and some amelioration of the suspicions about soldiers, yet at the end of the century Rudyard Kipling could contrast the ‘thin red line of ‘eroes when the drums begin to roll’ and the publican’s: ‘We serve no red-coats here.’

Jack Tar could, potentially, be as rough and rowdy as Tommy Atkins, but he was rarely criticised to the same extent. Of course it would be quite wrong to label every pre-war Tommy as drunk and dissipated, but the two world wars appear to have moderated the critical attitudes. The patriotic volunteers of 1914 and many of the young men conscripted in the last two years of war were from a very different social class, with very different expectations from the old volunteer army. These were men who had never expected to serve in the army and who came from families that had never expected to see their young men in khaki. Conscription during the Second World War, and its maintenance until the beginning of the 1960s, continued this moderation, and so too has the fact that recent conflicts involving an all professional army have been of suspect legality and questionable motivation. When brave young men are losing their lives or returning from distant, unpopular wars severely disabled, the idea that anyone should point to some of them being criminal offenders appears to some to be offensive.

In 1946 the former president of the British Military Court in Jerusalem made a throwaway comment at a Rotary Club dinner. When someone asked about theft by Palestinian Arabs, he replied that British soldiers were’ the biggest thieves in the world.’ A glance through the press during both world wars reveals soldiers involved in everything from petty theft to major black-market racketeering. A glance through other sources shows them selling guns to insurgents in Ireland in 1921 and to Hagana in Israel in 1947. Large numbers of young women in the ruins of continental Europe appear to have worn clothes styled and hand-made from British Army blankets; the blankets, along with cigarettes, army rations, chocolates were purchased with watches, cameras, jewellery, and sometimes their bodies. British soldiers raped – though not as often, it seems, as soldiers from other armies; sometimes they robbed; occasionally they murdered. They were paid to fight, and often they fought men on their own side. There were regimental rivalries; rivalries between ships’ crews or ships from different home ports; above all their were rivalries with better-paid troops from the White Dominions and, above all, in both world wars there was hostility towards the over-paid, over-sexed Americans who were ‘over-here’. At times the evidence reads like contemporary reports of fighting between rival street gangs. But then servicemen recruited for the duration of a war knew that, once engaged with the acknowledged enemy of the state, they depended on their mates, on their new family of the platoon or company, the gun battery, their shipmates, their crew.

The notion of the brutalised veteran, returning home unable to settle back into civilian life and engaging in a life of robbery and violence was common after both world wars. There appears to have been a slight increase in violence following both world wars, but this seems mainly to have been domestic violence as men responded to stories of their wives ‘carrying-on’ with others in their absence or lashed out when a noise or an incident reminded them of some aspect of their war experience. A few self-harmed; the statistical evidence does not point to many suicides, but police officers and others could cover up a suicide to protect a family, especially if the man was a war hero. A few others could not settle back into civilian and took to living rough.

Occasional outbursts of violence, loss of temper, self-harm, living rough are problems recognised among veterans of modern wars. Criminal offending by servicemen, especially by young, poorly educated men, sometimes from broken homes, who finish up in the tough so-called ‘teeth-units’ that do the hard fighting in modern armies should not come as a great surprize. No more so should the fraud and dodgy-dealings that is to be found among some administrative and logistics personnel. The armed services, as noted earlier, reflect the societies from which they come. Governments, under pressure from different charities, are being forced to recognise the deleterious impact of military service on some young men. The historical evidence suggests that government responses have improved, but there is still some way to go. Governments boast about using evidence-based policy, the history of crime and the British armed services needs much more research; and it can certainly produce much significant evidence.

Clive Emsley is Emeritus Professor, the Department of History, The Open University. He is the author of Soldier, Sailor, Beggarman, Thief: Crime and the British Armed Services since 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only History articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vintage engraving from 1861 of Uniform of the 1st Surrey Rifles from the British Army via Duncan1890, iStockphoto.

The post Soldier, sailor, beggarman, thief appeared first on OUPblog.

Humane, cost-effective systems for formerly incarcerated people

A recent New York Times article, reports on a study that found private, corporate-run transitional halfway houses were less effective in preventing recidivism than releasing inmates directly into communities. For those interested in understanding and improving outcomes among ex-offenders, these results are discouraging.

However, the size and scale of the halfway houses could have contributed to these disappointing results. The study included 38 facilities across the state housing up to 4,500 individuals; one private company had four facilities that could together house almost 800 individuals. Successful outcomes rarely occur when individuals are taken out of one dehumanizing large-scale system and put in another. Human warehousing is no replacement for real community reintegration.

However, the size and scale of the halfway houses could have contributed to these disappointing results. The study included 38 facilities across the state housing up to 4,500 individuals; one private company had four facilities that could together house almost 800 individuals. Successful outcomes rarely occur when individuals are taken out of one dehumanizing large-scale system and put in another. Human warehousing is no replacement for real community reintegration.

Re-integration programs need to offer useful, scalable features with specific goals and consequences for program administrators as well as program recipients. As reported, inspections of these facilities revealed residents had too much unstructured time. Residents need support to use their time looking for employment or training opportunities for jobs. However, one individual mentioned that the private companies running these facilities seemed more concerned with filling up beds than providing effective services.

These recovery systems exist within the larger economic and social system. The current economic climate continues to provide few job opportunities, particularly for ex-offenders. As such, those with the most needs at the bottom of the social ladder have even fewer opportunities to positively change their life.

We need more naturalistic, humane, and cost-effective systems to address the more than 600,000 individuals released from jail and prison each year. In contrast to large facilities, we have seen much lower recidivism rates in Oxford Houses, which are small-scale (7-12 person), democratic, self-run, self-financed recovery communities. When ex-offenders in these small scale recovery houses have experienced mentors and hope, they are less likely to relapse and go back to prison. Today, there are over 10,000 former addicts who live in over 1,500 of these Oxford houses across the country, many of whom are ex-offenders.

What makes systems like Oxford House an attractive and economic alternative to other large systems is their adherence to specific goals (providing sober housing) modeled after a general program of mutual help and support groups. In these democratic settings, there are specific requirements (abstinence, employment, resident participation) and sanctions for violating these principles (immediate eviction). We need to explore alternatives to large, de-humanizing institutions that often perpetuate the problem of recidivism.

Leonard A. Jason, professor of clinical and community psychology at DePaul University and director of the Center for Community Research, is the author of Principles of Social Change published by Oxford University Press. He has investigated the self-help recovery movement for the last 20 years. Ron Harvey is a graduate student in Community Psychology at DePaul University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Two hands clutching prison bars. Photo by jgroup, iStockphoto.

The post Humane, cost-effective systems for formerly incarcerated people appeared first on OUPblog.

Psychocinematics: discovering the magic of movies

Like the great and powerful Oz, filmmakers conceal themselves behind a screen and offer a mesmerizing experience that engages our sights, thoughts, and emotions. They have developed an assortment of magical “tricks” of acting, staging, sound, camera movement, and editing that create a sort of sleight of mind. These techniques have been discovered largely through trial and error, and thus we have very little understanding of how they actually work on our psyche. Scholars of “film studies” have thought deeply about the nature of movies, yet few scientists have considered empirical analyses of our movie experience—or what I have coined psychocinematics. Yet more than any other artistic expression or form of entertainment, we are captured by movies and involve ourselves with the characters portrayed, almost as if are in the scenes themselves.

How do filmmakers draw us into the drama and keep us riveted to the screen? How does film editing link events in an often seamless manner? How do movies drive our emotions, instilling suspense, laughter, horror, sadness, and surprise along the way? Why are movies so compelling? One’s first response might be: “It’s the story, stupid!” If the plot isn’t interesting or if we cannot identify with the characters portrayed, interest soon diminishes. Of course, how a filmmaker engages us into the plot is determined by a variety of factors: the acting may be superb, the visuals stunning, the editing seamless or interestingly quirky, the drama gripping, or the suspense overwhelming. For a scientific understanding, one needs evaluate these rather subjective features by developing a theoretical framework for empirical research.

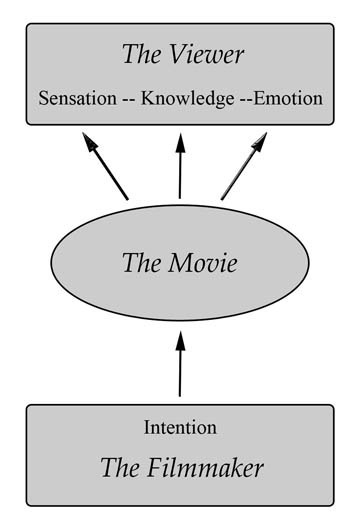

Toward a scientific analysis of movies, I’ve come up with a simple scheme that captures the psychological features of our movie experience, which I call the I-SKE model. The name is an acronym for what I believe are four essential components of our aesthetic response to movies: the intention (I) of the filmmaker and three psychological components of the viewer: sensation, knowledge, and emotion. The I-SKE model was initially developed to describe our aesthetic response to visual art (see Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder). When we experience art, indeed when we experience anything, we don’t start from a “blank slate” as we are always applying our knowledge to new experiences, drawing on world knowledge, cultural experiences, and personal memories. Ernst Gombrich, the noted art historian called this influence “the beholder’s share.” With respect to movies, filmmakers play on our prior knowledge (of life and of movies) by offering an audiovisual experience that is part storytelling and part a simulation of how we naturally experience the world. The I-SKE model can be used to breakdown the beholder’s share into the sensory, conceptual (knowledge), and emotional features of film. Indeed, when these three components are running at maximum intensities we experience that satisfied feeling as the movie credits roll and exclaim, “that was fantastic!” Psychocinematics considers the impact of these I-SKE components and how they interact.

Toward a scientific analysis of movies, I’ve come up with a simple scheme that captures the psychological features of our movie experience, which I call the I-SKE model. The name is an acronym for what I believe are four essential components of our aesthetic response to movies: the intention (I) of the filmmaker and three psychological components of the viewer: sensation, knowledge, and emotion. The I-SKE model was initially developed to describe our aesthetic response to visual art (see Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder). When we experience art, indeed when we experience anything, we don’t start from a “blank slate” as we are always applying our knowledge to new experiences, drawing on world knowledge, cultural experiences, and personal memories. Ernst Gombrich, the noted art historian called this influence “the beholder’s share.” With respect to movies, filmmakers play on our prior knowledge (of life and of movies) by offering an audiovisual experience that is part storytelling and part a simulation of how we naturally experience the world. The I-SKE model can be used to breakdown the beholder’s share into the sensory, conceptual (knowledge), and emotional features of film. Indeed, when these three components are running at maximum intensities we experience that satisfied feeling as the movie credits roll and exclaim, “that was fantastic!” Psychocinematics considers the impact of these I-SKE components and how they interact.

With the advent of brain imaging techniques, particularly functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), psychological science can now link mental events with brain processes. Indeed, it is now possible to have individuals watch a movie in a fMRI scanner and record the brain regions that are active during the experience (something that was considered science fiction fantasy only 20 years ago). In this way, one can map psychological experience with brain activity. We must not, however, fall into a modern-day version of phrenology where bumps on the head are replaced by bright spots on a brain scan. We need to go further and develop theories that describe the functional dynamics of neural activity and how brain regions interact to enable us to see, think, and feel. Thus, psychocinematics offers an opportunity to consider our movie experience from a scientific perspective that connects minds, brains, and experience at the movies. In the end, we’ll need more than psychology and biology, as sociology, history, anthropology, and other relevant disciplines are needed to gain a broad understanding of the magic of movies.

Arthur P. Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He studies the psychological and biological underpinnings of memory and movies. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. He is co-editor of Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience (Shimamura & Palmer, ed., OUP, 2012), editor of the forthcoming Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies(ed., OUP, March 2013), and author of the forthcoming book, Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (May 2013). Further musings can be found on his blog, Psychocinematics: Cognition at the Movies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Psychocinematics: discovering the magic of movies appeared first on OUPblog.

The Blaines of Lake Geneva

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (1896–1940) was born in St Paul, Minnesota, and named after his second cousin three times removed, the author of “The Star-Spangled Banner”. He went to Princeton University, but dropped out, eventually joining the Army in 1917. While in the service he began writing a novel, and also met and fell in love with Zelda Sayre, of Montgomery, Alabama, whom he married in the spring of 1920, the year in which he published his first novel, This Side of Paradise. The novel, a thinly disguised fictional account of Fitzgerald’s Princeton years, made its author an instant literary success and a celebrity as well. In honor of the anniversary of the publication of This Side of Paradise on 26 March 1920, we dug up this excerpt from this great novel.

Amory Blaine inherited from his mother every trait, except the stray inexpressible few, that made him worthwhile. His father, an ineffectual, inarticulate man with a taste for Byron and a habit of drowsing over the Encyclopædia Britannica, grew wealthy at thirty through the death of two elder brothers, successful Chicago brokers, and in the first flush of feeling that the world was his, went to Bar Harbor and met Beatrice O’Hara. In consequence, Stephen Blaine handed down to posterity his height of just under six feet and his tendency to waver at crucial moments, these two abstractions appearing in his son Amory. For many years he hovered in the background of his family’s life, an unassertive figure with a face half-obliterated by lifeless, silky hair, continually occupied in “taking care” of his wife, continually harassed by the idea that he didn’t and couldn’t understand her. But Beatrice Blaine! There was a woman! Early pictures taken on her father’s estate at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, or in Rome at the Sacred Heart Convent — an educational extravagance that in her youth was only for the daughters of the exceptionally wealthy — showed the exquisite delicacy of her features, the consummate art and simplicity of her clothes. A brilliant education she had — her youth passed in renaissance glory, she was versed in the latest gossip of the Older Roman Families; known by name as a fabulously wealthy American girl to Cardinal Vitori and Queen Margherita and more subtle celebrities that one must have had some culture even to have heard of. She learned in England to prefer whiskey and soda to wine, and her small talk was broadened in two senses during a winter in Vienna. All in all Beatrice O’Hara absorbed the sort of education that will be quite impossible ever again; a tutelage measured by the number of things and people one could be contemptuous of and charming about; a culture rich in all arts and traditions, barren of all ideas, in the last of those days when the great gardener clipped the inferior roses to produce one perfect bud.

In her less important moments she returned to America, met Stephen Blaine and married him — this almost entirely because she was a little bit weary, a little bit sad. Her only child was carried through a tiresome season and brought into the world on a spring day in ninety-six. When Amory was five he was already a delightful companion for her. He was an auburn-haired boy, with great, handsome eyes which he would grow up to in time, a facile imaginative mind and a taste for fancy dress. From his fourth to his tenth year he did the country with his mother in her father’s private car, from Coronado, where his mother became so bored that she had a nervous breakdown in a fashionable hotel, down to Mexico City, where she took a mild, almost epidemic consumption. This trouble pleased her, and later she made use of it as an intrinsic part of her atmosphere — especially after several astounding bracers. So, while more or less fortunate little rich boys were defying governesses on the beach at Newport, or being spanked or tutored or read to from “Do and Dare,” or “Frank on the Lower Mississippi,” Amory was biting acquiescent bell-boys in the Waldorf, outgrowing a natural repugnance to chamber music and symphonies, and deriving a highly specialized education from his mother.

“Amory.”

“Yes, Beatrice.” (Such a quaint name for his mother; she encouraged it.)

“Dear, don’t think of getting out of bed yet. I’ve always suspected that early rising in early life makes one nervous. Clothilde is having your breakfast brought up.”

“All right.”

“I am feeling very old to-day, Amory,” she would sigh, her face a rare cameo of pathos, her voice exquisitely modulated, her hands as facile as Bernhardt’s. “My nerves are on edge — on edge. We must leave this terrifying place to-morrow and go searching for sunshine.”

Amory’s penetrating green eyes would look out through tangled hair at his mother. Even at this age he had no illusions about her.

“Amory.”

“Oh, yes.”

“I want you to take a red-hot bath — as hot as you can bear it, and just relax your nerves. You can read in the tub if you wish.”

She fed him sections of the “Fêtes Galantes” before he was ten; at eleven he could talk glibly, if rather reminiscently, of Brahms and Mozart and Beethoven. One afternoon, when left alone in the hotel at Hot Springs, he sampled his mother’s apricot cordial, and as the taste pleased him, he became quite tipsy. This was fun for a while, but he essayed a cigarette in his exaltation, and succumbed to a vulgar, plebeian reaction. Though this incident horrified Beatrice, it also secretly amused her and became part of what in a later generation would have been termed her “line.”

“This son of mine,” he heard her tell a room full of awe-struck, admiring women one day, “is entirely sophisticated and quite charming — but delicate — we’re all delicate; here, you know.” Her hand was radiantly outlined against her beautiful bosom; then sinking her voice to a whisper, she told them of the apricot cordial.

They rejoiced, for she was a brave raconteuse, but many were the keys turned in sideboard locks that night against the possible defection of little Bobby or Barbara. . . . These domestic pilgrimages were invariably in state; two maids, the private car, or Mr. Blaine when available, and very often a physician. When Amory had the whooping-cough four disgusted specialists glared at each other hunched around his bed; when he took scarlet fever the number of attendants, including physicians and nurses, totalled fourteen. However, blood being thicker than broth, he was pulled through.

The Blaines were attached to no city. They were the Blaines of Lake Geneva; they had quite enough relatives to serve in place of friends, and an enviable standing from Pasadena to Cape Cod. But Beatrice grew more and more prone to like only new acquaintances, as there were certain stories, such as the history of her constitution and its many amendments, memories of her years abroad, that it was necessary for her to repeat at regular intervals. Like Freudian dreams, they must be thrown off, else they would sweep in and lay siege to her nerves. But Beatrice was critical about American women, especially the floating population of ex-Westerners.

“They have accents, my dear,” she told Amory, “not Southern accents or Boston accents, not an accent attached to any locality, just an accent” — she became dreamy. “They pick up old, moth eaten London accents that are down on their luck and have to be used by someone. They talk as an English butler might after several years in a Chicago grand-opera company.” She became almost incoherent — “Suppose — time in every Western woman’s life — she feels her husband is prosperous enough for her to have — accent — they try to impress me, my dear —- ”

Though she thought of her body as a mass of frailties, she considered her soul quite as ill, and therefore important in her life. She had once been a Catholic, but discovering that priests were infinitely more attentive when she was in process of losing or regaining faith in Mother Church, she maintained an enchantingly wavering attitude. Often she deplored the bourgeois quality of the American Catholic clergy, and was quite sure that had she lived in the shadow of the great Continental cathedrals her soul would still be a thin flame on the mighty altar of Rome. Still, next to doctors, priests were her favorite sport.

“Ah, Bishop Wiston,” she would declare, “I do not want to talk of myself. I can imagine the stream of hysterical women fluttering at your doors, beseeching you to be simpatico” — then after an interlude filled by the clergyman — “but my mood — is — oddly dissimilar.”

Only to bishops and above did she divulge her clerical romance. When she had first returned to her country there had been a pagan, Swinburnian young man in Asheville, for whose passionate kisses and unsentimental conversations she had taken a decided penchant — they had discussed the matter pro and con with an intellectual romancing quite devoid of soppiness. Eventually she had decided to marry for background, and the young pagan from Asheville had gone through a spiritual crisis, joined the Catholic Church, and was now — Monsignor Darcy. “Indeed, Mrs. Blaine, he is still delightful company — quite the cardinal’s right-hand man.”

“Amory will go to him one day, I know,” breathed the beautiful lady, “and Monsignor Darcy will understand him as he understood me.”

Amory became thirteen, rather tall and slender, and more than ever on to his Celtic mother. He had tutored occasionally — the idea being that he was to “keep up,” at each place “taking up the work where he left off,” yet as no tutor ever found the place he left off, his mind was still in very good shape. What a few more years of this life would have made of him is problematical. However, four hours out from land, Italy bound, with Beatrice, his appendix burst, probably from too many meals in bed, and after a series of frantic telegrams to Europe and America, to the amazement of the passengers the great ship slowly wheeled around and returned to New York to deposit Amory at the pier. You will admit that if it was not life it was magnificent. After the operation Beatrice had a nervous breakdown that bore a suspicious resemblance to delirium tremens, and Amory was left in Minneapolis, destined to spend the ensuing two years with his aunt and uncle. There the crude, vulgar air of Western civilization first catches him — in his underwear, so to speak.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was a writer whose fiction is one of the most eloquent expressions of the American Jazz Age of the 1920s. Jackson R. Bryer is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Maryland. He has published widely on F. Scott Fitzgerald, including an edition of the love letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda (2002), and he has been President of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society since 1990. For Oxford World’s Classics he has edited This Side of Paradise.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Blaines of Lake Geneva appeared first on OUPblog.

Whitman today

By Jerome Loving

Walt Whitman died 121 years ago today. The Bruce Springsteen of his age, he sang about and celebrated what he called “the Divine Average”. And it was always on equal terms, the woman the same as the man, as he suggests in “America”. Shortly before his death, the aging bard may have spoken the poem into one of the Thomas Edison’s devices that made wax cylinder recordings. It authenticity is suggested by the fact that the recording which survives, readily available on the web, is one of the late poems of Leaves of Grass (1855-1892) instead of something earlier and today greater. Poets always think they’re working on their best poem, and “America” is a late poem for Whitman.

Centre of equal daughters, equal sons,

All, all alike endear’d, grown, ungrown, young

or old,

Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich,

Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law

and Love,

A grand, sane, towering, seated Mother,

Chair’d in the adamant of Time.

Walt Whitman in 1872

Whitman’s plan for democracy went beyond the shores of the United States. In “Passage to India”, he celebrated the completion of three great achievements in communication—the opening of the Suez Canal, the linking up of the Union and Central Pacific transcontinental railroads, and the laying of the Atlantic Cable—as an advancement of international brotherhood.

Europe to Asia, Africa join’d, and they to the New World,

The lands, geographies, dancing before you, holding a festival garland,

As brides and bridegrooms hand and hand.

Today Whitman has become something of a cultural artifact. Levi uses the “America” poem in one of its advertisements. Walt Whitman used to “sing the body electric,” writes Tom Geier. “Now, the late poet is singing the praises of denim-clad bodies in a new advertising campaign for Levi’s . . . . It’s not the first time that dead authors have been used to shill products, though I can’t help finding the whole concept a little creepy and unsettling”. The poet’s image has also been used in a number of cinemas, including, most famously, in Dead Poets Society. The actor has starred in a CBS special in the 1970s entitled Song of Myself. There he played the poet as he was about to publish his first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855. Torn also appeared as the older Whitman in the movie Beautiful Dreamers (1990); there the older Whitman visits a Canadian Mental Hospital, where his first biographer, Richard Maurice Bucke, was superintendent. The poet engages the inmates, finding sanity in their diagnosed insanity.

“This is what you shall do,” Whitman wrote in the famous preface to the first edition of his book: “Love the earth and sun and the animals, despise riches, give alms to every one that asks, stand up for the stupid and crazy, devote your income and labor to others, hate tyrants, argue not concerning God, have patience and indulgence toward the people, take off your hat to nothing known or unknown or to any man or number of men, go freely with powerful uneducated persons and with the young and with the mothers of families, read these leaves in the open air every season of every year of your life, re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul, and your very flesh shall be a great poem.”

He also wrote in the 1855 Preface that “America” was “essentially the greatest poem.” He meant that nature itself was a poem of which we were all a miraculous part:

Who goes there? hankering, gross, mystical, nude;

How is it I extract strength from the beef I eat?

“Take my leaves America, take them South and take them North,” the poet urges us in “Starting From Paumanok.” The leaves, or spears of grass, are Whitman’s stand-in for nature itself, which as Ralph Waldo Emerson had taught him, was the emblem of God. The grass was also green, the color of hope, and perennial, reflecting the endless recycling of lives. These symbols were dropped into our existence by God the way a lady would drop her handkerchief to attract the notice of a man:

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may

see and remark, and say Whose?

Jerome Loving, Distinguished Professor of English at Texas A&M University, is the editor of Oxford World Classics edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. He is the author of a number of biographies, including Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. His Confederate Bushwhacker: Mark Twain in the Shadow of the Civil War will be published in the fall of 2013.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Walt Whitman. Photographer: G. Frank E. Pearsall (1860-1899) (NYPL Digital Gallery) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Whitman today appeared first on OUPblog.

March 25, 2013

Ode to my Tuba - the beautiful Tallulah

At the age of sixteen I was told that I would no longer be able to play my beloved trumpet, due to medical complications. The only alternative, to uphold my county scholarship and commitments to orchestras and brass bands, was to take up the tuba. The arrogant trumpeter that I was back then was horrified at this cumbersome instrument, cuddling a great lump of brass that seemed to prove no merit to my sense of style or popularity. At the time, being a grumpy adolescent, this was torture.

Years on, I take pride in my position as a tuba player. My beautiful Besson Sovereign tuba is affectionately named Tallulah or Tula for short. I have learned what a delightful instrument the tuba is and how versatile and lyrical they can be when played (even if they are a little heavy). There seems to be a stigma that the tuba’s only vocation is as an instrument of the “ump-pah-pah” and counting endless bars of rests. However, more needs to be said of this sometimes under-rated instrument.

Years on, I take pride in my position as a tuba player. My beautiful Besson Sovereign tuba is affectionately named Tallulah or Tula for short. I have learned what a delightful instrument the tuba is and how versatile and lyrical they can be when played (even if they are a little heavy). There seems to be a stigma that the tuba’s only vocation is as an instrument of the “ump-pah-pah” and counting endless bars of rests. However, more needs to be said of this sometimes under-rated instrument.

Unlike many string and woodwind instruments, the tuba has limited devoted repertoire. What is available varies in its purpose, some look to parody the instrument as the piece “Tuba Smarties” by Herbie Flowers does. Yet there are odd concertos that present the instrument in its splendour, as the Vaughan Williams’s Concerto for Bass Tuba does. Commissioned by the London Symphony Orchestra in 1953 to mark the 50th anniversary of the orchestra, Vaughan Williams’s tuba concerto remains today an outstanding work for the instrument and is recognised as the first major work written for the tuba. Indeed, when it was premiered on 13 June 1954, performed by the orchestra’s principal tuba player Philip Catelinet, it was the first time that a concerto of its kind had ever been performed.

It is through the Vaughan Williams concerto that we are able to recognise the great range of the tuba and appreciate its hidden talents. While it cannot be denied that it serves the purpose of a supporting bass in orchestras and brass bands very well, it is also capable of sweeping cadenzas (when given the opportunity) and in a lead role, such as it features in this concerto, it is evident how charismatic it can be. A particular favourite movement of mine is the second, the Romanza. It is easy to presume with its size that the tuba is quite an awkward instrument, yet in this movement the real sensitivity and tenderness of the tuba is heard.

For the meantime, I continue to practise my part from the arrangement for tuba and piano; perhaps one day I will have the opportunity to play the piece with an orchestra.

Ruth Fielder is the Sales Administrator in the Sheet Music Department at Oxford University Press.

Ralph Vaughan Williams‘s wide-ranging musical activities greatly enhanced English musical life but they have also contributed to the mistaken view that his compositional work was in some way parochial. He believed in the value of music education and wrote practical competition pieces, serviceable church music, and with the 49th Parallel he found a new outlet in writing for film. His profoundly disturbing Symphony No.6 received international acclaim with more than a hundred performances in a little over two years. The Concerto for Bass Tuba and Orchestra was composed in 1953-4 to mark the 50th anniversary of the formation of the LSO and was written for the orchestra’s principal tuba player, Philip Catelinet. It was the first major concerto to be written for the instrument, and remains today the outstanding work of its kind.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition.

Image credit: A gold brass tuba euphonium isolated against a white background in the vertical format. Photo by mkm3, iStockphoto.

The post Ode to my Tuba - the beautiful Tallulah appeared first on OUPblog.

March Madness: Atlas Edition – Final Four

Oklahoma State and Georgetown are out, but Madagascar, Indonesia, Turkey, and Mexico are still in the running. Confused? It’s time for the Final Four of March Madness: Atlas Edition! While players battle it out on the court, countries in our tournament are competing for the coveted title of “Country of the Year” based on statistics drawn at random from Oxford’s Atlas of the World: 19th Edition.

Last week we asked: Which country has a higher level of endemism?

Check out the winners below! Did you get them right?

Madagascar vs. Burma (Myanmar) WINNER: Madagascar

Indonesia vs. Japan WINNER: Indonesia

Italy vs. Turkey WINNER: Turkey

Mexico vs. USA WINNER: Mexico

For the Final Four, we want to know:

By current estimates, which country’s capital is expected to be more populated in 2015?

Madagascar vs. Indonesia

Turkey vs. Mexico

The development of agriculture more than 10,000 years ago led to the clustering of communities in farming villages. From there, the world’s first cities appeared in the lower Tigris and Euphrates valleys 5,500 years ago. Cities cropped up in China 3,600 years ago, and now the majority of the world’s population live in cities. The pull of city life is only growing. By 2015, 28.7 million inhabitants are expected to live in Tokyo-Yokohama, the largest metropolitan area by that year. To determine the winners in this week’s round, select the country whose capital will be the most populated in 2015. You can print out our Atlas bracket (below) and place your bets, or play along on our Facebook page. Check back on 1 April to find out what will make it to the semi-finals!

Tournament schedule:

Sweet Sixteen: 11 March Which country has the highest GDP per capita?

Round of 8: 18 March Which country has a higher level of endemism?

Final Four: 25 March This week: Which country’s capital will be more populated by 2015?

Semi-finals: 1 April

Championship: 8 April

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post March Madness: Atlas Edition – Final Four appeared first on OUPblog.

Mark Blyth on austerity

It is one of the most important topics in world politics and economics, yet few understand how it works and its real impact. Austerity — that toxic combination of politics and economics — must be recognized for what it is and what it costs us. The arguments for it are thin, while the evidence of its impact on wealth and income inequality is ample. For every economy to grow, this dead economic idea needs to stay dead.

Political economist Mark Blyth, author of Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, explains how austerity leads to low growth and hurts economies from local to global.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Mark Blyth is Professor of International Political Economy at Brown University. He is the author of Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea and Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mark Blyth on austerity appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers