Oxford University Press's Blog, page 963

March 29, 2013

Exclusion and the LGBT life course

Few scenes in one’s life evoke vivid imagery. A generation’s historical memory can be reduced to a single significant moment—think Pearl Harbor, JFK’s assassination, 9/11. For gay and lesbian Californians of my generation, the State Supreme Court’s 2008 ruling in favor of same-sex marriage seemed initially like it might just be such a moment. As a well-adjusted gay man, happily partnered for over a decade in a relationship legally recognized through the state’s domestic partnership system, I did not anticipate the wave of emotion I felt upon hearing the decision. I had grown accustomed to the “separate but equal”(ish) system the state had constructed for me. I lived happily in a predominantly gay enclave in San Francisco and had grown accustomed to, even embraced, separation from “mainstream” heterosexual culture. Like most gays and lesbians in my generation (born in the 1970s, coming out in the 1990s), I had successfully navigated the psychological challenges of social and political exclusion.

One of the great achievements of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movement has been the creation of communities in which a young lesbian can feel a sense of inclusion and commonality. LGBT communities offer her a space in which no explanation, no defense, and no apology for her sexual orientation is needed. These communities represent vital adaptations to a social structure in which the experience of sexual minorities and their ability to participate in cultural institutions—free from stigma and discrimination—is constantly relegated to a question.

What would it mean to reimagine that young lesbian’s life course in the context of a new cultural and political reality—a life course not characterized by the navigation of stigma but of the possibility for unapologetic self-expression? While the US Supreme Court may not be as concerned with the psychology of social exclusion as it is with the technicalities of “standing,” this question ought to be at the forefront of our national conversation, if we care at all about today’s LGBT youth, and if we hope for them a life course of possibility rather than limitation.

Today’s LGBT youth are coming of age in a radically different cultural reality than previous generations. On the one hand, they have access to far greater resources and far greater access to one another. Many of today’s youth experience diversity in sexual orientation as the “new normal,” as psychologist Ritch C. Savin-Williams suggested in The New Gay Teenager (Harvard University Press, 2005). Sociological studies in high schools in both the United States by C.J. Pascoe (Dude, You’re a Fag, University of California Press, 2007) and the United Kingdom by Mark McCormack (The Declining Significance of Homophobia, Oxford University Press, 2012) support this idea.

But the storyline about today’s LGBT youth is not so straightforward. As the justices were quick to suggest this week, social change is not linear and immediate but in an active state of debate. A popular refrain of marriage equality opponents has been that more time is needed for cultural conversation before a ruling that might apply to the entire nation. How might that young lesbian experience this debate about her own life course possibilities?

In 2011, the Institute of Medicine issued a report indicating that LGBT persons continue to experience health and mental health disparities relative to their heterosexual peers. The report coincided with a major review paper in the Journal of Research on Adolescence by Elizabeth Saewyc revealing that the “new normal” for LGBT youth does not necessarily translate into the privilege of an adolescence unburdened by victimization or psychological distress. In short, LGBT youth experience both greater support than ever and continued psychological distress because of continued societal stigma. Narratives of struggle coexist with narratives of liberation from societal stigma in a rapidly changing cultural context for sexuality.

As a culture, we are at a crossroads. Do we maintain the rhetoric of stigma and its policy implications? Do we suggest to today’s LGBT youth that their pursuit of happiness in the love and satisfaction of an intimate relationship is culturally inferior to their heterosexual peers? Do we suggest to them that they are lesser, defective, abnormal? Or do we use this opportunity to apply the anchoring political ideals of our nation—ideals like individual liberty and equality before the law—to a group whose long history of demonization has been accompanied by significant psychological struggle?

Here politics and science converge for the great “experiment” to be concerned with is not the consequences of same-sex marriage for society, but rather the consequences of social exclusion for the health and well-being of sexual minority persons. To summarize the evidence from social science: stigma and subordination psychologically harm LGBT people. Same-sex relationships provide meaning and happiness and are comparable to opposite-sex relationships. Many same-sex relationships actually show more equality in matters such as domestic labor and communication than opposite-sex relationships. The children of same-sex headed households fare just as well as those of opposite-sex ones. When the rights of sexual minority people are subject to a vote by the majority, they experience greater psychological distress as surveys conducted during anti-gay marriage amendment votes have illustrated. That young lesbian listening to the marriage equality debate has a psychological response to what it means for her life.

In short, the evidence to weigh is not whether marriage equality will somehow erode society as we know it but rather how marriage inequality interferes with the fundamental rights enshrined in our national narrative of political liberty and equality, subordinating an entire class of citizens and thwarting the possibilities of a life course free from stigma and psychological distress. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are not abstract concepts; they are lived psychological experiences—lived by LGBT people in spite of a social structure that conspires against them.

While I would never wish a different life course upon myself—my struggles define my identity—I would welcome a world in which young LGBT persons do not have to navigate the psychology of social and political exclusion. And I and other social scientists would welcome a world in which our political ideals are embodied in our concern for the psychological welfare of our nation’s LGBT citizens.

Phillip L. Hammack is Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He is co-editor of The Story of Sexual Identity: Narrative Perspectives on the Gay and Lesbian Life Course (Oxford University Press, 2009) and co-editor of Oxford’s Series on Sexuality, Identity, & Society.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Exclusion and the LGBT life course appeared first on OUPblog.

Blogging oral history

It’s been six months since we at Oral History Review (OHR) started blogging regularly at the OUPblog, so we think now is a good time to look back on the last few months. We’ve discussed everything from the historiography of oral history to the challenges of recording interviews on recent history, and we’ve approached these issues with essays, q&as, timelines, quizzes, and podcasts.

Our first post talked about the promise of how oral history can work with other fields. It’s important to remember how we can work with others and how their work can inform our own. One of the strengths of oral history is the ability to take an interdisciplinary approach.

We can all learn a new digital approach. New media provides both challenges and opportunities for us all. Technology has shifted the collection and dissemination of oral history. Oral historians must decide on how to address fellow historians and the general public. We could even quiz you on it.

In fact, when Oral History Review staff looked through the responses to our survey on print versus online publishing, we learned that over 50% of our readers haven’t activated their online subscriptions, and nearly 20% are not sure whether they have activated their accounts or not. We’ve set up a brief tutorial on the Oxford Journals website to guide you through the process.

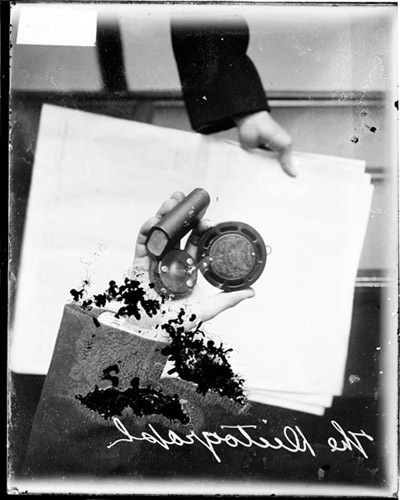

Image of a man holding a dictograph, a small recording device used for gaining evidence, in a room in Chicago, Illinois. Chicago Daily News, Inc., photographer. 1912 Feb. 3. DN-0058190, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum. Library of Congress.

We’ve also begun the Oral History Review podcast, which features interviews with leading oral historians including Michael Gillette, Jason Steinhauer, Roger Davis Gatchet, and Stephen Sloan. In our last post, managing editor Troy Reeves spoke with issue 40.1 contributor Lindsey Barnes about her upcoming article with Kim Guise, “World War Words: The Creation of a World War II-Specific Vocabulary for the Oral History Collection at the National WWII Museum.” Good news, that article is now available online at our Oxford Journals website.

Whether discussing community identity, a common vocabulary, or our students, the different approaches of our fellow oral historians have been enlightening. Moreover, it’s quite the reversal for many of us to be on the other side of the recorder and it has helped us appreciate the challenge that others may have in opening up to us.

Finally, although our field is called oral history, we continue to address issues that are relevant today. It informs and provides perspective on current issues, and some history is lived every day.

As always, we invite your comments and ideas on how we can continue to examine our field in new ways and address different matters.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Blogging oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

Oh! what a lovely conclave

“Carnival time is over,” the newly-elected Pope Francis is reported to have said when he was offered an ermine-trimmed mozzetta such as most of his predecessors had worn round their shoulders during the winter season. He may not have been alluding to the thirteen-day sede vacante which had just reached its much-anticipated conclusion, but it does seem fair to say that this papal interregnum was arguably the jolliest on record. Previous interregna included a period of mourning before the cardinals entered the conclave; this one made history precisely because it didn’t. That did much to lighten the atmosphere.

In 2005, after the death of John Paul II, interest in the ensuing conclave did not seem to extend much beyond predicting — presumably for gambling purposes — who would be elected. The procedures of the conclave were explained for the benefit of the wider public, but opportunities to bring the entire experience to life with reference to what is known of past conclaves were rarely, if ever, taken. In some quarters there might still be an assumption that the history of conclaves must be a subject dry enough to rival Stubbs on Archbishop Stigand, but the greater variety of media platforms created during the last eight years has allowed a little more conclave history to trickle out this time round. We have also seen some splendid online graphics illustrating the balloting process as it currently exists, complete with cartoon cardinals waddling up penguin-like to cast their votes.

In 2005, after the death of John Paul II, interest in the ensuing conclave did not seem to extend much beyond predicting — presumably for gambling purposes — who would be elected. The procedures of the conclave were explained for the benefit of the wider public, but opportunities to bring the entire experience to life with reference to what is known of past conclaves were rarely, if ever, taken. In some quarters there might still be an assumption that the history of conclaves must be a subject dry enough to rival Stubbs on Archbishop Stigand, but the greater variety of media platforms created during the last eight years has allowed a little more conclave history to trickle out this time round. We have also seen some splendid online graphics illustrating the balloting process as it currently exists, complete with cartoon cardinals waddling up penguin-like to cast their votes.

It would be interesting to know whether any broadcasters amended their schedules in the last few weeks in order to screen cinematic accounts of past conclaves: the nearest that most of us will ever get to the real thing. In 2002 the streets of Rome were deserted when RAI broadcast the John XXIII biopic Papa Giovanni, starring the American Edward Asner in the title role. In that production much attention is devoted to the reading of the ballot papers, with the number of votes for Cardinal Roncalli increasing scrutiny by scrutiny. When Cardinal Seán Brady spoke of his reaction at hearing the name “Bergoglio” read out time after time, it brought to mind the conclave scenes in Papa Giovanni. One feature of conclaves that has not survived since Pope John’s election in 1958 is the practice of cardinals — as collective rulers of the Church in the absence of a papal monarch — sitting beneath baldacchini which they cause to collapse when the new pope is elected. That particular carnival is well and truly over, but it is certainly instructive to see it on screen.

As conclave films go, rather more fanciful is The Conclave (2006), a loose dramatisation of Pius II’s account of his own election in 1458, twisted in order to feature Rodrigo Borgia, the most junior cardinal deacon, in scenes far removed from ecclesiastical politics. Pius’s unparalleled memoirs are as rich in inside information as they are overtly hostile towards his French counterparts. There is, however, something deeply unconvincing about the casting of Brian Blessed as Enea Silvio Piccolomini. Let’s settle for his beard as the source of the problem. Clerical beards deserve a blog post all of their own, and would doubtless have received one had the Capuchin Seán O’Malley been elected last week. In the fifteenth century the beard that mattered was that of the Greek cardinal Bessarion who, as Pope Pius relates, quite literally came within a whisker of being elected in 1455, until the Breton cardinal Alain de Coëtivy urged his fellow electors not to entrust the Latin Church to a man whose facial hair suggested that he was an easterner at heart. Bessarion is one of the lesser characters in The Conclave, the very existence of which suggests that we shall never see the conclave of 1455 depicted in film.

As far as we non-cardinals are aware, the most dramatic conclave of the modern period was that of 1903, when the Austrian veto was pronounced against Cardinal Rampolla, whose votes steadily declined while the name “Sarto” was read out with increasing frequency. That might well have cinematic potential, but at least it seems to have inspired the novel Hadrian VII, which was published the following year. Had this month’s conclave lasted any longer than it did there might have been serious anxiety in many a Catholic household, as clerics and laymen alike suspected they might be about to experience their Corvo moment. Productions of Peter Luke’s play of the novel allow us to revel in a stage full of cardinals.

The dramatic impact of Pope Benedict’s helicopter flight into the sunset is not something that could be repeated with anything like the same effect. Indeed, in the light of recent events, papal resignations now look like becoming the norm, with papal elections therefore becoming less of a surprise and more matter-of-fact. After decades of inertia in the Vatican, Pope Francis probably needs to be a pontiff in a hurry and, thus far, is proving to be precisely that. If his simplifying agenda extends to papal elections, perhaps we shall have all the more need of fictional conclaves to illustrate what we have lost.

Stella Fletcher was a founding editorial board member of Oxford Bibliographies in Renaissance and Reformation, and has made a number of contributions, including Cardinals. Her publications include Princes of the Church: a history of the English cardinals (2001) and Roscoe and Italy (2012). She is honorary secretary of the Ecclesiastical History Society, of which she has also written ‘A Very AgreeableSociety’: The Ecclesiastical History Society, 1961-2011.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vatican, Vatican City State – March 13, 2013: Black smoke emerges from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican after the cardinal vote for a new pope. Black smoke indicates that no pope was elected. It is the second day of the conclave to elect a pope. Photo by omada, iStockphoto.

The post Oh! what a lovely conclave appeared first on OUPblog.

Magic moments

By Owen Davies

Magic in the modern world

The recent battle between religion and science conducted in the media, spearheaded by Professor Richard Dawkins and other high-profile figures, has garnered much international attention. The debate is not new of course; it stretches back several centuries. One aspect of the debate that receives less attention today is the issue of magic: a concept which is inextricably linked to the history of science and religion. The notion of both science and religion as magic is as relevant today as it ever was.

Magic: what’s in a word?

Magic continues to pervade popular imagination and language. Today the term ‘magic’ can be used to describe the supernatural, superstition, simple illusion, religious miracles, and fantasies of the imagination. It can also be applied to the ‘wonders’ of science, or used as a simple superlative. The literary confection known as ‘magical realism’ has considerable appeal, as demonstrated by the success of Life of Pi. Modern scientists have even incorporated the word into their vocabulary, with their ‘magic acid’ (a super acid developed in the 1960s) and ‘magic angles’ (an angle of 54.7356°) .

Click here to view the embedded video.

Magic and primitivism

Since the Enlightenment – which the study of magic reveals as a problematic historical concept in itself – magic has often been seen as a marker of primitivism, of a benighted earlier stage of human development, and yet across the modern globalised world hundreds of millions continue to resort to magic and also to fear it. Magic provides explanations and remedies for those in extreme poverty and without access to alternatives. While in the industrial West, with its state welfare systems, religious fundamentalism decries the continued public threat posed by magic, and in our pluralistic spiritual democracy some have redefined magical practices as a form of religion.

Global magic

The debate over religion, magic, and science in the modern world is also too often conceived within a Judaeo-Christian western framework of intellectual development, with the magical and religious beliefs of much of the rest of the world ignored in general histories and debates. The magic of the literary cultures of China, India, and Asia are as rich and ancient as those of the Mediterranean world and are equally important to understanding what influenced developments in western magic. Understanding how different cultures have negotiated the relationship between science, religion and magic over the centuries and millennia also help us put Western developments in context. The influence of the Bible and Koran on magical traditions in Africa, the Americas and the Middle East are equally illuminating. The vast resource of oral traditions regarding magic, science, and religion in non-literary cultures also needs to be considered on an equal footing in our consideration of past and present human understanding. It is only by studying and comparing oral and literary magic cultures of the world that we can breakdown notions of primitiveness based on western assumptions.

Magic in your car

Twentieth-century technology is not immune from magical interference. Across the globe today talismans are placed in cars to protect them as much as the occupants. Ethnographers working in the bocage region of Normandy during the 1970s and 1980s found that car accidents or breakdowns were sometimes blamed on witchcraft. This notion is merely a technological version of the frequent accusations in earlier European sources that witches caused cart wheels to break or wagons to get stuck in the mud. In parts of Africa the introduction of tractors added a new dimension to agricultural witchcraft disputes. A study of road travel in Ghana found that the wrecks of cars and lorries at accident black spots on otherwise good, new road surfaces attracted suspicions of witchcraft.

Wishful thinking: magic?

We all have our magic moments. Have you ever urged your car to go faster as it struggles up a slope? Have you ever made a wish or believed that an event was more than coincidence? A desire for something to happen – ‘I hope she loses her job’ – may be expressed rationally, but if it comes true it may be interpreted magically. These are phenomena of our waking hours. In our dreams our minds lead us into magical worlds and activities. Far from espousing a rational view of the world, parents from cultures across the globe actively encourage magical thinking in pre-school children. It provides explanations to satisfy children in their early stages of inquisitiveness about why things work or happen. Children’s books feed magical fantasies, and early-years children’s television present magical worlds that bear no relationship to the real world. Why do we nourish magical thinking? It shields our ignorance, helps parents avoid uncomfortable questions, and provides a satisfying shared realm of adult and infant imagination and escapism.

Owen Davies is Professor of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire. He has written extensively on the history of magic, witchcraft, and ghosts, including Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (OUP, 2009), The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts (Palgrave, 2007), Paganism: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2011), and Magic: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2012).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with Very Short Introductions on Facebook, and OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Magic moments appeared first on OUPblog.

March 28, 2013

A very short slideshow of our very short soapboxes

By Chloe Foster

We had 13 wonderful Very Short Introductions authors taking part in our series of Very Short Soapboxes at the Sunday Times Oxford Literary Festival last week. The change of venue, from the usual marquee at Christ Church to the warmth and comfort of Blackwell’s bookshop, was a blessing (who wants to stand in a tent with a snow blizzard outside? Although some would say our authors are that good). From Medical Law to The Napoleonic Wars, from The Gothic to The British Empire, there was a subject for everyone to enjoy. Here are a few highlights.

Barry Cunliffe gives a talk on The Druids

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la All eyes on Barry Cunliffe for his excellent talk

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Lynda Mugglestone speaks to a captive audience about Dictionaries

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Some audience members come and chat to Lynda after her talk

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Klaus Dodds speaks about The Antarctic

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Klaus Dodds

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Elleke Boehmer accompanies her talk with some props!

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Elleke Boehmer talks about Nelson Mandela

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la  ');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-37741";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "thumbslider";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with Very Short Introductions on Facebook, and OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A very short slideshow of our very short soapboxes appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating the suffrage movement in International Women’s History Month

The campaigners for women’s suffrage rightfully occupy a place at the forefront of the coverage of International Women’s History Month. Women such as Emmeline, Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst, Millicent Fawcett, Josephine Butler, and Nancy Astor earned themselves recognition from their involvement in the campaign for women’s suffrage. The women who campaigned against granting women the right to vote are less frequently commemorated, although many were also prominent figures at the time. Their positions provide an interesting insight into women’s varying roles in and expectations of political life; they assumed positions of leadership and often argued for the advancement of women’s rights in education and the workplace while attempting to preserve more conservative gender roles.

Who Was Who entries provide insight into the diversity of attitudes to women’s suffrage in the early years of the twentieth century. The career section of the suffragette Constance Lytton’s entry details the injuries she sustained after being force fed during a prison hunger strike, while Ellen Odette, Countess of Desart’s work was summarized as “The usual duties of a well-educated, intelligent woman, conscientiously carried out; very strong anti-suffrage views.” To celebrate that variety, here are a few of the accomplished and occasionally surprising women who weighed in against suffrage:

Mary Augusta Ward, known as Mrs Humphry Ward, was the first head of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League, which she helped found in 1908, and edited the Anti-Suffrage Review. She came to public prominence as a novelist; her books were much disliked by Virginia Woolf, who wrote that “[Ward] is as great a menace to health of mind as influenza to the body,” but were phenomenal bestsellers on both sides of the Atlantic. Ward was a philanthropist, social reformer, advocate of women’s education, war correspondent, and eventually became one of England’s first female magistrates. She believed that national politics dealt with “constitutional, legal, financial, military, international problems — problems of men, only to be solved by the labour and special knowledge of men, and where the men who bear the burden ought to be left unhampered by the political inexperience of women.” (The Times, 27 February 1909).

Gertrude Bell was the founding secretary of the Anti-Suffrage League, and eventually headed their northern branch. Whilst she also believed most women did not have the experience to take part in politics, her own career, which included stints as a diplomat, archaeologist, traveller, writer, mountaineer, linguist, political officer and spy, meant that she was highly influential and made huge contributions to British imperial policy in the Middle and Near East. There was a strong vein of imperialist enthusiasm in the anti-suffrage movement; Clementina Fessenden, founder of Empire Day and propagandist, is one of the few people in Who Was Who to list her membership of the Anti-Suffrage League in her entry.

Bell’s friend Violet Markham was another supporter of the Anti-Suffrage League. Her main field of interest as a social reformer was in the alleviation of poverty and unemployment, particularly for women. She advanced a belief in the importance of women’s work, whilst maintaining the Victorian ideology of ‘separate spheres’ for the sexes, believing that women could contribute politically by participating in local government. She explained this in at an anti-suffrage rally on 28 February 1912, at the Albert Hall:

“We believe that men and women are different — not similar — beings, with talents that are complementary, not identical, and that they therefore ought to have different shares in the management of the State, that they severally compose. We do not depreciate by one jot or tittle women’s work and mission. We are concerned to find proper channels of expression for that work. We seek a fruitful diversity of political function, not a stultifying uniformity.”

The changes in women’s lives bought about by the First World War moderated Markham’s beliefs, and by the 1918 general election, she was prepared to stand, albeit unsuccessfully, as an Independent Liberal parliamentary candidate.

Laura Dawkins is a Development Editor for Scholarly Reference at Oxford University Press.

Who’s Who is the essential directory of the noteworthy and influential in every area of public life, published worldwide, and written by the entrants themselves. Who’s Who 2013 includes autobiographical information on over 33,000 influential people from all walks of life. The 165th edition includes a foreword by Arianna Huffington on ways technology is rapidly transforming the media. Please note that the Who’s Who articles in this blog post will be freely accessibly for a month from 27 March 2013, after which you can access through subscription.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ggbain-13078)

The post Celebrating the suffrage movement in International Women’s History Month appeared first on OUPblog.

Dinah Shore’s TV legacy

For Black History Month, I wrote about an American Television pioneer: Nat “King” Cole, who was the first African American to host a television show. Since many have dubbed March as “National Women’s Month,” I focus on another pioneer of early television, Dinah Shore.

American television of the 1950s was a haven for white male artists and hosts. African Americans were scarce on TV, appearing only as guest artists on musical variety shows. Women television artists fared no better. Of the many female singers active at the time (Lena Horne, Rosemary Clooney, Judy Garland, and numerous others), the only woman singer to host her own TV show was Dinah Shore.

Frances “Fanny” Rose Shore was born on 29 February 1916, in Winchester, Tennessee. After graduating from Vanderbilt University, she moved to New York City to pursue a singing career. Her first job was as a singer at WNEW, a radio station in New York, where she sang with Frank Sinatra who was hired around the same time. During one show, she sang “Dinah,” and a DJ who couldn’t remember her name called her the “Dinah girl.” The name stuck, and she used it for the rest of her life. She sang and recorded with Xavier Cugat’s band, and recorded her first big solo hit, “Yes, My Darling Daughter” in 1941.

Click here to view the embedded video.

With her radio and recording successes, she was signed to host her own radio show, “Call to Music” in 1943. That same year she appeared in her first movie, “Thank Your Lucky Stars” starring Eddie Cantor. She became immensely popular, touring to entertain US troops during World War II and recording several hit records. Shore also appeared in musical films throughout the 1940s, including Belle of the Yukon (1944) and Till the Clouds Roll By (1946).

Like many radio stars, Dinah Shore made the move to television. In 1951, she made her television debut on The Ed Wynn Show, and also made a guest appearance on Bob Hope’s first NBC television special. These appearances resulted in NBC assigning her own regular TV show, The Dinah Shore Show in November 1951. Like many programs at the time, the show was given two 15-minute time slots during the week. In 1956, Chevrolet sponsored Dinah to host two one-hour specials, and their success led to Dinah Shore’s Chevy Show, a regular musical variety show that ran from 1956 until 1961, running in a Sunday evening time slot on NBC.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Shore’s success on the show can be attributed to her conservative vocal choices and middlebrow sensibilities. She, like many TV stars of the decade, was content to sing “standards” and “Tin Pan Alley” songs that were familiar to the TV audience. In particular, she was noted for her famed signature theme song, the catchy Chevrolet jingle, “See the USA in your Chevrolet,” accompanied by her closing gesture of a sweeping smooch to the audience.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The song was helped by the fact that its sponsor was an “all American” car, and the lyric: “America’s the greatest land of all,” also affirmed the conservative TV audience’s sensibilities. After the Chevy Show, Shore went on host three daytime television programs: Dinah’s Place (1970 to 1974), the 90-minute talk show Dinah! (1974 to 1980), and Dinah and Friends (1979 to 1984).

Click here to view the embedded video.

Her TV career ended in 1991 after a two-year run on cable TV’s The Nashville Network with the talk show, A Conversation with Dinah.

Dinah Shore achieved much success in her television career, winning the Emmy Awards for Best Female Singer (1954-55), Best Female Personality (1956-57), and Best Actress in a Musical or Variety Series (1959). However, The Dinah Shore Chevy Show rarely entered the top 20 ratings during its run, as it ran against CBS’s General Electric Theater hosted by Ronald Reagan, which regularly won the time slot (Reagan also had a better lead-in with The Ed Sullivan Show).

Besides TV, Dinah Shore was an avid golfer, and supporter of women’s golf. She founded the Colgate (and now Nabisco) Dinah Shore Tournament on the LPGA tour. Dinah Shore passed away on 24 February 1994 in Beverly Hills, California, after a brief battle with ovarian cancer.

[image error]

Ron Rodman is Dye Family Professor of Music at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. He is the author of Tuning In: American Television Music, published by Oxford University Press in 2010. Read his previous blog posts on music and television.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Photograph provided by author.

The post Dinah Shore’s TV legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

This April fools’ day, learn from the experts

As the First of April nears you may be planning the perfect joke, hoax, or act of revenge. If so—and if you’re looking for inspiration—may we recommend some of British history’s finest hoaxers, courtesy of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. So this year, how about …

1. Going shopping. In 1809 Theodore Hook performed a spectacular act of revenge by ordering enormous quantities of coal, musical instruments, upholstery, linen, and jewellery for delivery in unison to the same address in Berners Street, London. The lord mayor of London, governor of the Bank of England, and the duke of Gloucester were also tricked into making an appearance at the victim’s door. The Berners Street hoax took Hook, and two accomplices, six weeks to plan. This was before internet shopping. Think what you could do.

2. Doing-it-yourself. Follow the example of Frances Griffiths and Elsie Wright and cut out your own imitation fairies and gnomes. Next take some photos of them at the bottom of the garden, and bring them to the attention of a devotee of the paranormal, such as Arthur Conan Doyle. With his backing the ‘Cottingley fairies’ became a worldwide sensation and continued to convince (some) until 1983 when Griffiths and Wright admitted their hoax. As Elsie remarked: ‘I’m old now and I don’t want to die and leave my grandchildren thinking that they had a loony grandmother.’

3. Being a bit more ambitious. For this one you’ll need a Royal Navy battleship, a few false beards, and Virginia Woolf. Masterminded by the professional practical joker Horace De Vere Cole, the party (including a youthful Woolf) tricked their way onto HMS Dreadnought and toured the ship while masquerading as the Abyssinian royal family. Here’s the proof.

4. Making use of your balding friends. To imitate this one, another of De Vere Cole’s, you’ll need to block book some theatre tickets (must be in the stalls) and then carefully arrange your balding associates, having first consulted a book of rude words. Read the biography for more—and don’t forget to cross your Ts and dot your Is.

5. Making a career of it. Hoaxes that last a day are really for beginners. Instead let Archibald Stansfield Belaney be your inspiration. Though born at 32 St James’s Road, Hastings, Sussex, Belaney passed himself off as Grey Owl—a native American whose deception was only uncovered after his death. If you think big, the rewards can be great. In 1937 Grey Owl was invited to give a lecture at Buckingham Palace; AND he was played by Pierce Brosnan in the film version of his unusual life.

6. Not discarding those fragments of orang-utan. In 1912 Charles Dawson and Arthur Woodward caused a sensation by announcing the discovery of the ‘missing link’ in human evolution—uncovered in a gravel pit not too far from Grey Owl’s boyhood home. The body, dated to 4 million BC, became known as Piltdown Man, and was for several decades widely regarded as the oldest fossil human found in Europe. Then, in the 1950s, came new scientific techniques and the revelation that Piltdown Man was simply an odd assembly of stained bones and the jaw of a young orang-utan. By then Dawson and Woodward were dead—and the who and why remain unanswered.

7. If can’t get hold of an orang-utan, rabbits will do. This was the experience of Mary Toft, the so-called ‘Rabbit woman of Godalming’, in 1726. It’s quite a story, though not for the faint hearted.

8. Going bump in the night. Rattle your plumbing in a convincing way, and who knows who’ll come by to investigate. This is what Elizabeth Parsons did in 1762 and she met Samuel Johnson and the duke of York! Like Grey Owl, her deception was commemorated in art, with a poem, play and an engraving by William Hogarth.

9. Breathing in. Staying with the eighteenth-century, we come to John Montagu, second earl of Montagu, who’s thought to have been behind the ‘bottle conjuror’ hoax, as performed to a packed Haymarket theatre, London, in 1749. The trick saw a full-size man squeeze himself into a wine bottle. If this were not enough, ‘during his stay in the bottle any person may handle it, and see plainly that it does not exceed a common tavern bottle’ (General Advertiser, 16 Jan. 1749).

10. Not promising violence, especially against foreigners. Be careful, not all April Fool’s day tricks go to plan, and the fooled can turn nasty—as the seventeenth-century actor Thomas Jevon can testify.

As well as reading their entries, you can also listen to the stories of the Cottingley fairies, Piltdown Man, and Elizabeth Parsons (the ‘Cock Lane ghost’) in the Oxford DNB’s 175-strong biography podcast.

Philip Carter is Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. In addition to 58,500 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 175 life stories now available. You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @odnb on Twitter for people in the news. The Oxford DNB is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post This April fools’ day, learn from the experts appeared first on OUPblog.

What can animals see, hear, or sense?

Our world is dominated by colours and patterns that provide information about how to behave and survive. These are a product of how our sensory system and brain interpret the physical properties of the environment. For example, how people see and describe colours can depend on whether they have ‘normal’ colour vision or not, what culture they come from, and even what their emotional state is. Colour is in the eye of the beholder!

However, the differences in perception among humans are a drop in the ocean compared to how other animals view the world. Even animals with the same sensory modalities (e.g. vision) have substantial differences across species. Take vision and ultraviolet (UV) light. We can’t see UV because our lens blocks these very short wavelengths before they can reach the photoreceptors. In contrast, many animals detect and use UV for a variety of tasks. For example, flowers may look beautiful to us, but seen through the eyes of a bee they take on a whole new appearance. Many petals have lines that are only visible in UV that run towards the centre of the flower. These ‘nectar guides’ act like landing lights, directing insects to the pollen and nectar. Birds also use UV. Many of us will have seen kestrels hovering at the side of a road or field. They can detect the presence of voles by picking up UV light that’s reflected by vole urine along trails. Blue tits provide another example. They look identical to us but the male plumage reflects more UV than females, and males with greater UV are more attractive in mating.

The same flower can look quite different to human eyes and other animals. The photo on the left is taken in human visible light, whereas the photo on the right encompasses the range of wavelengths bees can see (ultraviolet, shortwave, and mediumwave light, but not longer wavelengths that humans perceive).

Ultraviolet light is just one example of differences in vision among animals. Some of the most extreme cases come from the deep ocean. Longer (‘red’) wavelengths of light fail to reach here, making the conditions blue (rich in short wavelengths). In addition, almost all bioluminescence in the ocean is blue or blue-green, and because it doesn’t make sense to have a visual system that detects light that isn’t there, most animals in the depths can’t detect red light. Dragon fish, however, produce red bioluminescence and have a visual system to detect it. This means that they can signal to each other without attracting unwanted attention, and even use their red flashlights to hunt without the prey knowing that they’re there!

So far, we’ve focussed on vision. But humans have other senses too – touch, taste, smell, and hearing. Unfortunately, there’s nothing exceptional about any these either. We can hear sounds roughly in the range of 15-20,000 Hz (20 kHz), but this fails to match many species. For example, bats navigate and detect prey using ultrasonic echolocation (sometimes well above 100 kHz), which can be so refined that they can determine the size, texture, speed, and even wing beat frequency of their insect prey! Ultrasonic sounds are used by other animals too, such as mice and rats in aggressive encounters, mate attraction, and even to beg for food.

Animals also differ in what sensory systems they have, with humans lacking electric and magnetic senses that are found in other species. Birds are particularly well studied for how they use the earth’s magnetic field to navigate. Bees and other insects can also orientate based on magnetic cues, and as if echolocation wasn’t enough, so too can some bats. Equally fascinating is the use of electric information. Sharks and rays, and even some ‘primitive’ mammals like platypus and echidna can detect the electric fields generated by other animals (usually prey). Some fish from South America and Africa can even produce electricity and use this to navigate, find prey, identify their own species, and assess potential mates. Just as male and female blue tits look different to bird eyes, many electric fish have different electric signal forms for males and females.

Many animals including birds can see ultraviolet light. The top photos are human visible images of a parrot and budgie, whereas the images below show their striking colour patches in ultraviolet.

What drives differences among animal sensory systems? We don’t have all the answers to this important question but it’s clear that the environment that an animal evolved and lives in plays a major role. For example, electricity isn’t well conducted by air and so an electric sense would be useless to most terrestrial animals. Many fish with an electric sense live in murky disturbed waters or are nocturnal. Here, vision is more limited so they use other senses. Animals have also evolved sensory systems that are tuned to specific tasks. For example, some primates, including humans, evolved the ability to see differences between reds and greens (which most mammals don’t) for finding ripe fruit against green leaves. Finally, sensory systems take up significant resources and energy. There’s simply no reason to invest in a sensory system that’s not useful – natural selection doesn’t like waste! It’s why cave animals like blind cavefish lose their visual systems when they move into dark environments.

These are exciting times to study the perceptual worlds of animals. New technologies have made it possible to eavesdrop on once hidden modes of communication and to appreciate how other species interpret their environment. Above all, we are obtaining a much better picture of how sensory systems shape animals’ lives and the role they play in evolution, and even how we can learn from them to improve our own lives.

Martin Stevens is a BBSRC Senior Research Fellow, based in the Centre for Ecology & Conservation, University of Exeter. His research focuses on sensory ecology and behaviour, especially animal coloration and vision, across a range of organisms. It covers bird vision, anti-predator defences such as camouflage and warning signals, brood parasitism and cuckoos, and sexual signals and vision in primates. He is the author of Sensory Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution (OUP, 2013). Find Martin Stevens on Twitter: @SensoryEcology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Both images © Martin Stevens, all rights reserved.

The post What can animals see, hear, or sense? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 27, 2013

Achebe

A conversation with Chinua Achebe was a deep, slow and gracious matter. He was exceedingly courteous and always listened and reflected before answering. In his later years he talked even more slowly and softly, savouring the paradoxes of life and history. He spoke in long, clear, simple sentences which often ended in a profound and sad paradox. Then those extraordinary eyes twinkled, his usually very solemn face would break into a huge smile and he would chuckle.

He had a look of Nelson Mandela about him. Both have that ability to look very stern and solemn and then break into a huge smile. It happened when they met each other in South Africa, his daughter, Nwando, told me. At first the two men just looked at each other and then burst out laughing as if recognizing their brotherhood. Both romantic about Africa’s traditions, they talked and talked. Mandela had read Things Fall Apart when he was in prison on Robben Island and he said of Achebe: “The writer in whose company the prison walls fell down.”

He also shared Mandela’s care for ordinary people. I noticed how cleaners and nurses and others who cared for him were treated as friends.

His life was itself a paradox. He was of that first generation of ordinary Africans to receive western education. Until then only the sons of chiefs were sent to school. He loved and gloried in the education he had been lucky enough to receive – a typical British public school routine and curriculum. Nor had he any complaints about the benefits that modern technology had brought to Africa. But he was also a fierce defender of African traditions and the right – duty even – of all Africans to live by them and respect them. He wanted the two cultures to meet as equals. It was not about civilization replacing barbarism.

This was not merely philosophical. It was personal. His father, a Christian missionary who laboured tirelessly as a church worker and builder of churches, encouraged his son to read – especially the Bible. His father’s uncle however kept the traditions and when his nephew tried to convert him, the uncle showed him the insignia of his traditional Igbo titles – which he would have had to renounce if he became Christian. “What shall I do to these?” he asked. Achebe interpreted these words as: What do I do to who I am? What do I do to history?

The dilemma which separated his father from his great uncle haunted Achebe all his life. His books are set in the time when the old world was being destroyed, lost or abandoned and a new world of modernity, mediated by the West, was being imposed on Africa. His five novels trace the story from the coming of the white man, through to Nigeria’s independence and self government and its failure to deliver on its promises. His books were prescient about Nigeria’s failures. In A Man of the People, published in 1966, he describes a coup – which promptly happened in reality.

Whichever way he looked at it, the British seizure and creation of what is now Nigeria was a catastrophe. In Things Fall Apart the impetuous and uncompromising traditionalist, Okonkwo, tries to resist the British by force and ends committing suicide in the forest. In the next novel Arrow of God, the old keeper of the shrine, a modest open-minded man and based on Achebe’s great uncle, tries to engage with the white invaders, showing what might have been a coming together of different cultures. Instead the result is the same – they are not interested and humiliate him and destroy the shrine.

Achebe celebrated Nigerian independence with great excitement, believing, as most of his generation did, that a liberated Africa would soar. His disillusionment was swift and, long before the rest of the world foresaw the political failures of the new African states; Achebe pinpointed them. In A Man of the People he described the African states as a house abandoned by the colonial powers, taken over by “the smart and the lucky and hardly ever the best”, leaving the vast majority of the people out in the rain.

Soon after came the second agonizing dilemma of his life. In 1967 his Igbo people, feeling persecuted and excluded by the alliance of the northern Muslims and the Yoruba in the west, declared independence from Nigeria. Led by Colonel Ojukwu, the Igbo called their new country Biafra and Achebe was its chief proponent and propagandist. The war lasted three years and left more than a million dead. His last book, There was a Country, is an account of that war and shows Achebe to still be a staunch supporter of Biafran independence.

A car accident in Nigeria in 1990 left him in a wheelchair and dependent on others. He had to move to America for treatment. But his devoted wife Christie looked after him fiercely and made very sure he did not get mobbed by visitors or used by people who might exploit his easy going nature.

In my book, Africa Altered States Ordinary Miracles I used Achebe’s image of the house left behind by the imperial powers as a theme. I then had the cheek to contact him and ask him to write a forward. I was astounded and thrilled when he readily agreed and we got to meet each other.

In 2009 I accompanied him on his last visit to Nigeria to make a film for the BBC. We went to see the home that he had built for his family, complete with its own power and water supply and a lift that would take his wheelchair. It was close to completion and he wanted to live out his final years there but the medical services he needed were not available and his family persuaded him to stay in the US. Sadly that was his first and last visit to that house.

Everywhere he went he was mobbed. We drove at frantic speed from Abuja to Owerri accompanied by a police escort which forced everyone off the road. The lead police Land Rover roared up the middle of the road, lights full on, sirens wailing and police with whips lashing out at cyclists, bikers and pedestrians as they passed. At one stage the convoy took a wrong turning but doubled back, travelling the wrong way along a busy motorway at night. This was the sort of behavior that Achebe had denounced in his 1983 tirade The Trouble with Nigeria. I pointed this out to him. He gave me a rueful smile and shook his head sadly. His son Chide, a distinguished doctor in America, tried unsuccessfully to persuade them to go a little more slowly and be less violent.

Achebe delivered his lecture at Owerri in Igbo heartland and reminded his audience of their history, their culture, their language. This was their heritage, he said, and if they kept faithful to it, they would be strong. After the speech I asked audience members randomly what they thought of the speech. One of those I spoke to said he agreed: “If we know our Igbo language and culture we will be strong – and then we can rule Nigeria!” This sentiment was repeated by two others I interviewed. When I related this to the old man he was appalled. “That is not what I meant at all,” he said. But I wondered if, after his long absence from Nigeria, a new more cynical generation had lost touch with his noble, old-fashioned idealism.

I hope this and the scores of other tributes to one of the greatest Africans of his generation, whose work and memory will last as long as Africa itself, will be some consolation for Christie Achebe and all the family. I condole you.

Listen to Chinua Achebe: A Hero Returns, BBC Radio 4, 23:00, 22 March 2013 presented by Richard Dowden, Director of the Royal African Society and author of Africa; altered states, ordinary miracles.

This article originally appeared on African Arguments, hosted by the Royal African Society and World Peace Foundation, part of the Guardian Africa Network.

Richard Dowden is director of the Royal African Society.

African Affairs is published on behalf of the Royal African Society and is the top ranked journal in African Studies. It is an inter-disciplinary journal, with a focus on the politics and international relations of sub-Saharan Africa. It also includes sociology, anthropology, economics, and to the extent that articles inform debates on contemporary Africa, history, literature, art, music and more.

The post Achebe appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers