Oxford University Press's Blog, page 960

April 5, 2013

Environmental History’s growing pains

In the fall of 1994, I was invited to offer my university’s first environmental history course. Entering this unchartered territory, I scrambled to find sample syllabi and appropriate books. Nearly two decades later, environmental history is a standard course offering and my university, like so many others, boasts a thriving Environmental Studies major as well as a major in Environmental Science. Environmental history books, textbooks, articles, blogs, podcasts, and documentary films are flooding the market. The ASEH/FHS has grown by leaps and bounds, and Environmental History is recognized as a leading journal.

Some historical fields have evolved slowly, with movement like a glacier’s—meaningful, but slow. Environmental history has been more like an avalanche—fast, furious, and undeniable. Some of this growth can be attributed to timing, as environmental history and the information revolution took hold almost simultaneously. Tools like GIS made unique contributions to the field’s success. And like all fields, environmental history reaps the benefits of the internet, such as immediate access to articles and essays. H-Environment has created a global community of scholars in which questions are raised and answered, and opportunities to present and publish scholarship are widely circulated. More importantly, even as some traditional fields of historical study are increasingly denigrated as no longer crucial to the historical canon, appreciation of the practical value of environmental history is on the rise on campuses all over the world. Many universities offer not only environmental courses, but are dedicated to applying lessons learned, making their campuses as green as possible. Their success is judged (and celebrated) by publications including E-Magazine and the Chronicle of Higher Education.

One of the best changes is the increasing interdisciplinarity of environmental history and its incorporation into a variety of related studies. This sets it apart from other relatively new disciplines. Women’s history, for example, too often still finds itself isolated in a kind of pink ghetto as professors (and texts) of history courses with more traditional emphases (political, economic, and specific periodization) either ignore women’s history entirely or incorporate it only superficially. Environmental history, on the other hand, has more quickly been accepted as crucial to the historical enterprise and is given considerable coverage in a wide variety of courses covering a range of places, historical periods, and topics (including science, religion, gender, race, economics, and politics).

Autumn scence. 6 October 2012. Photo by Dmitri Popov. Creative Commons License.

There are some drawbacks to all this exciting growth, and not just that it’s impossible to keep up with the mounting supply of new information. A common complaint among environmental history professors and students alike is that the courses are just so depressing. Students complain that, having gained a true understanding of the breadth, depth, and life-threatening nature of the problems, they feel overwhelmed and helpless. In the face of rapid global warming, their individual efforts, including recycling their bottles and cans and bringing their reusable containers to Starbucks, seem akin to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

One of the new challenges facing this thriving field is to replace, or at least temper, the doom and gloom with a sense of practical empowerment. In delineating the human role in the creation of our current environmental crises, some historians are taking care to teach, rather than preach or scold, and highlight the roles that people have played in responding constructively to those crises, and in heading off others entirely. Such approaches create not a false sense of security, but inspiration, instilling feelings of responsibility and providing tools to help implement positive change.

Environmental history continues to experience a variety of growing pains, but its growth, and its ability to inspire, challenge, and promote genuine understanding and meaningful reform, reveals in new and dynamic ways the profound value of the study of history.

Nancy C. Unger is Associate Professor of History at Santa Clara University. She is the author of Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers: American Women in Environmental History and the prize-winning biography Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer, and book review editor of The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Environmental History’s growing pains appeared first on OUPblog.

What do the Falkland Islands continue to tell us about territorial world views?

By Klaus Dodds

The last couple of weeks have been busy ones when it comes to news about the Falkland Islands. Or Islas Malvinas as Argentine and other readers might insist upon. For others, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) is the preferred naming option — highlighting as it does their continued contested status.

We have had the Falkland Islands referendum. I was fortunate enough to be an accredited observer and spent a very interesting few days watching the voting and counting unfold in Stanley and the wider Islands. Shortly afterwards, an Argentine bishop was appointed the next Pope, Francis I, and this encouraged speculation about what the pontiff might have to say on the question of the Islas Malvinas. President Kirchner of Argentina was quick off the mark and paid her respects at the Vatican. Whatever special powers the Pope possesses, it won’t be enough to alter the sovereignty dynamic in the case of these South Atlantic islands. As Margaret Thatcher might have said the current UK government is not for turning — sovereignty is not up for discussion. And, most recently, new archival papers released in the UK revealed that members of the Thatcher government were divided over how to respond to the Argentine invasion of April 1982. For all the talk of an ‘Iron Lady’ and dispatching a ‘task force’ to recover the Islands, there was clearly the possibility at one stage or another of a deal being done. Raising in the process the enticing question of how British politics, let alone the fate of the Falkland Islanders, might have been different if war was avoided and some kind of settlement secured.

But that was April 1982 and things have moved on since then. Indeed, in the last two years, relations between Britain and Argentina have worsened and there is no reason to think that any settlement will be forthcoming. Whatever some newspaper columnists might think, the referendum was intended to send a clear message to Argentina and the wider world that the Falklands community is not looking to its nearest neighbor when considering future options. And, at the moment, it does not need to. The UK government has reiterated its support for respecting the ‘wishes’ of the Falkland Islands community and that other neighbours such as Chile and Uruguay are a benign presence. Brazil, while offering some rhetorical support to Argentina, is not unhelpful to the UK position. So the imbroglio continues.

At this stage, attention often turns to other kinds of options, beyond the continuation of the status quo i.e. the Falklands continuing as a UK overseas territory. While laudable, I think what continues to fascinate me about these islands is perhaps what insights they have to offer us more generally. As other geographers such as Alec Murphy note, territory continues to exercise an extraordinary ‘allure’ in our contemporary world. Noting all the claims made in the 1990s about globalization and border-free worlds, the idea of territory remains popular with political leaders and publics alike. For one thing, and perhaps other islands such as Cyprus animate this issue as well, territory helps to consolidate a view of political life being container like. Islands, with their apparently clear-cut distinctions between land and sea seem to lend themselves well to the containerization of political thought.

Second, we might think about territory as a flexible resource, which enables the socio-spatial education of citizens. In the case of the Falklands, there is a vast array of materials ranging from postage stamps, computer games and atlases to commemoration and museum displays that play their part in the geographical education of citizenry. They play their part in creating regimes of territorial legitimation and reinforce particular spatial commitments. The end result is to remind us perhaps that states rarely give up territory and usually only do so under extreme circumstances. Even when the territory in question was poorly understood and arguably neglected, as was the case of the Falklands in 1982, there was still sufficient allure in the territory itself combined with a sense of protecting the small resident community to ensure that the UK committed itself to resisting the Argentine occupation. The invading Argentine forces, on the other hand, while undoubtedly aware of the Falklands as a geographical component of Argentina, were remarkably ignorant of the English speaking community residing on the islands. Islanders still recall of Argentine amazement when they discovered that their first language was English and not Spanish.

What was striking, in the aftermath of the 1982 conflict, was the billions of pounds the UK was prepared to invest in the Falklands, and the wider commitment to bolster a presence in the South Atlantic and Antarctic. The idea of giving up the territory in question was now unthinkable, and if anything the Falklands is more embedded in UK stories about its extra-territorial scope and responsibities (as well as histories of war and commemoration). UK governments use the term ‘overseas territories’ to acknowledge that distance need not be any kind of barrier to their continued connection with the UK.

Finally, we should not under-estimate the power of territorially based world-views and the ease in which many territorial disputes seem unable to make much progress when it comes to promoting alternative imaginations — joint sovereignty, parallel statehood, cross citizenships, and other kinds of free associations. This does not mean such things are not possible or even desirable in the case of some of the most violent and apparently intractable disputes. But one should not under-estimate how keenly many people feel around the world about lines on the maps and barriers on the ground. Perhaps they offer a modicum of reassurance in a world, where to paraphrase Marx and Engels, all that appears solid melts into air. And this would apply to both Britain and Argentina.

Klaus Dodds is Professor of Geopolitics at Royal Holloway, University of London and a Visiting Fellow at St Cross College, University of Oxford. He is editor of The Geographical Journal and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He is the author and editor of a number of books including the Geopolitics: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2007) and The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2012). He was a visiting fellow at Gateway Antarctica, University of Canterbury and has worked with national and international polar organizations including British Antarctic Survey, Antarctica New Zealand, International Polar Foundation, and the Australian Antarctic Division.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with Very Short Introductions on Facebook, and OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Wild Nature [public domain] via iStockphoto

The post What do the Falkland Islands continue to tell us about territorial world views? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2013

The professionalization of library theft

The indication that an ordinary string of rare book thefts has evolved into a terrifying string of rare book thefts often comes down to this: the presence of a man whose sole job it is to get rid of library ownership marks. No other single trait indicates as certainly that a theft ring has moved from the amateur to the professional ranks. So while it seems encouraging that five people involved in the Girolamini Library thefts have been sentenced for their crimes, it had better only be the beginning of people being prosecuted. One of the men charged two months ago with playing a part in the scheme was a Bologna bookbinder whose job was to scrub books of their marks — and his presence, like that of a single cockroach, signals a much larger problem.

Almost all library books are marked in some way by their owner institution, usually with one of three types of stamp: ink, emboss or perforation. There are also a host of secondary identification marks, including bookplates pasted inside the front cover and cataloguing information written on the title page or gutter. All of these must be destroyed for a professional thief to feel safe.

Almost all library books are marked in some way by their owner institution, usually with one of three types of stamp: ink, emboss or perforation. There are also a host of secondary identification marks, including bookplates pasted inside the front cover and cataloguing information written on the title page or gutter. All of these must be destroyed for a professional thief to feel safe.

Solo thieves — the dreaded one-man-bands of the cultural heritage theft world — do this work themselves, the results of which are often poor. Because these guys have to spend a lot of time worrying about the thefts and the sales, they often give short shrift to the most tedious part of the job, making a hash of it with unsightly, value-killing blemishes — an easy thing to do when mixing bleaching agents and hot irons with paper that is often centuries old. So theft rings that grow to a certain size either develop from amidst their ranks men who have an aptitude for the task, or they simply hire people whose job it is to work with old books.

The American book theft ring I write about in Thieves of Book Row was very particular about scrubbing its books of library markings. It employed a small army of men to steal from America’s libraries to feed the Manhattan book trade, but warned these men against tinkering with book stamps. A botched field-scrub could ruin the value of book — and was, counter-intuitively, an even more tell-tale sign of theft than even the presence of a library stamp, which could often be explained away. Book cleaning was done by a few trusted individuals; in the case of particularly tricky marks, like perforated stamps, the work could be outsourced to England.

This is almost certainly what happened in Italy. A Bolognese bookbinder, who could be trusted both to work with old paper and to keep his mouth shut, would be a go-to guy for tough marks. He would know how to clean pages or, if needed, get rid of them altogether, replacing the marked leaves with either close copies from other editions or pages manufactured expressly for the purpose. This is an act known in the book world as “sophisticating,” and a really fine job of it requires the touch of a craftsman.

The worst news is, like any cottage industry that becomes successful enough to hire specialists, book theft rings that employ task-specific men soon need a guaranteed supply to justify their expense. It’s a feedback loop that all but guarantees that the Girolamini Library arrests and prosecutions have barely scratched the surface.

Travis McDade is Curator of Law Rare Books at the University of Illinois College of Law. He is the author of the upcoming Thieves of Book Row: New York’s Most Notorious Rare Book Ring and the Man Who Stopped It and The Book Thief: The True Crimes of Daniel Spiegelman. He teaches a class called “Rare Books, Crime & Punishment.” Read his previous blog posts: “Barry Landau’s coat pockets” ; “The difficulty of insider book theft” ; and “Barry Landau and the grim decade of archives theft”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image via iStockphoto.

The post The professionalization of library theft appeared first on OUPblog.

The 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention

Derided by a number of major military powers when it was adopted, almost 16 years later the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention is in pretty rude health. No fewer than 161 States have adhered to its provisions — the most recent being Poland in December 2012 – and few outside dare to use anti-personnel mines these days such is the stigmatisation of the weapon, even though a ban has not yet crystallised in customary law. There is little or no transfer of anti-personnel mines, and what little there is consists mainly of small-scale, illicit sales. As a result, large stockpiles in China and the USA lie dormant, and even Russia is no longer laying mines in Chechnya, so far as we know.

Of course, challenges remain in implementing the treaty. Assistance to mine victims has made relatively little headway in recent years, frustrated by trials and tribulations in overcoming institutional weaknesses in health systems in many post-conflict nations. Progress in mine clearance has been especially disappointing, with two dozen States being forced to request extensions to their 10-year treaty deadlines, and this despite the fact that many had to confront only limited contamination. The United Kingdom has even implied that the clearance requirements only apply to developing nations with significant numbers of casualties, a perverted reading of its international legal obligations (which most certainly extend to mined areas on the Falkland Islands). At the same time, non-party States China, Nepal, and the USA have cleared most, if not all of the mines on territory under their jurisdiction, so the treaty has had a broader normative impact.

Furthermore, if donors are as generous over the next decade or so as they have been over the last 20 years, the world should still be all but cleared of landmines by 2022 — only 25 years since the adoption of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention. That’s no mean achievement, even though it should have been possible sooner and at a much cheaper cost than the estimated $10 billion or so it will likely have cost. Regrettably many countries and operators still commit precious clearance assets to areas without any contamination as their survey capacity and risk management abilities are lacking. National capacity building has been more a tool of rhetoric than an on-the-ground reality.

So what are the treaty’s broader lessons for disarmament? The Convention, which entered into force on 1 March 1999, was the result of the ‘Ottawa Process’, a freestanding treaty negotiation outside a United Nations (UN)-facilitated forum with the aim of outlawing anti-personnel mines. The process was so called because it was launched in Ottawa in October 1996 by Lloyd Axworthy, the Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs. Axworthy and his staff had seen that progress towards a ban was doomed to be thwarted by the tradition of consensus within UN disarmament fora, notably the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW). After three years of negotiations, the CCW was only able to agree on a complex set of additional restrictions that did not even require all mines to be self-destructing and/or self-deactivating. In contrast, the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention was negotiated from start to finish in less than a year.

Party states to the Ottawa Treaty via Wikimedia Commons.

Sadly, two decades later, little has changed in the disarmament world. The only weapon that has been banned since 1997, cluster munitions, was similarly the result of a freestanding process, this time led by Norway, after the CCW had again failed to act forcefully. Ironically, once the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) had been adopted in Dublin in 2008, a number of States, led by the USA, sought to adopt a protocol to the CCW restricting the weapon for those planning not to adhere to the CCM in the near to medium term. But by then it was too little, too late, and some ham-fisted diplomacy resulted in no agreement.

It seems likely that future weapons law treaties will also have to go outside the United Nations if they are to be adopted (unless inroads can be made into the tyrannical consensus ‘rule’). For getting 193 Member States to agree to ban or restrict anything remotely useful in military terms is a challenge that will rarely be met in practice. Anti-vehicle mines, explosive weapons with wide area effects, tasers and other ‘less-lethal’ weapons, and even nuclear weapons are all on the agenda for greater regulation in years to come. But there’s little prospect of any agreement being made in consensus fora, such as the Conference on Disarmament or UN disarmament mechanisms.

Perhaps some normative progress can be achieved under the auspices of the Human Rights Council, notably with regard to the use of certain weapons outside situations of armed conflict. Otherwise, it remains to a State or core group of States to take the initiative, and then it’s every State for itself and the Devil take the hindmost (to paraphrase). In this, the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention just reflects the traditional method of adopting weapons law treaties in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth. So maybe it’s just a return to the rule, proving that disarmament within the UN is a mere exception.

Stuart Casey-Maslen is Head of Research at the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. He is author of Commentaries on Arms Control Treaties, Volume 1: The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction and co-editor of The Convention on Cluster Munitions: A Commentary.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention appeared first on OUPblog.

McDonald’s revisited: when globalization goes native

In January 2013 the Daily Telegraph ran a story on the refusal of the inhabitants of the famed old neighbourhood of Montmartre, in Paris, to accept the arrival in their midst for the first time of a Starbucks coffee shop. The Paris Pride heritage association denounced this “attack on the place’s soul.” A resident said “we must do everything to stop this disfiguring, as it opens the door to any old rubbish.” Twenty years previously, said local sources, McDonald’s had tried to open, but they had been forced out. Now the invader was back, just with a different disguise.

What is it about these world-wide American food and drink experiences which can still set off such resistance in local communities wherever they choose to land? Of course this is by no means a universal reaction, in time or place, otherwise there would not be 1,700 Starbucks shops across Europe (including Russia), or 7,300 McDonald’s restaurants, with more coming even in the crisis. But the multi-faceted power of these companies, and their apparently unstoppable will to expansion, has provoked a variety of antagonisms over the years. Starbucks’ historian, Bryant Simon, talks of ‘pushback’. More serious is the ‘brand backlash’ that a New York Times correspondent saw in the targeting of McDonald’s around the world at the time of the Iraq war.

What is it about these world-wide American food and drink experiences which can still set off such resistance in local communities wherever they choose to land? Of course this is by no means a universal reaction, in time or place, otherwise there would not be 1,700 Starbucks shops across Europe (including Russia), or 7,300 McDonald’s restaurants, with more coming even in the crisis. But the multi-faceted power of these companies, and their apparently unstoppable will to expansion, has provoked a variety of antagonisms over the years. Starbucks’ historian, Bryant Simon, talks of ‘pushback’. More serious is the ‘brand backlash’ that a New York Times correspondent saw in the targeting of McDonald’s around the world at the time of the Iraq war.

Most of the negative impulses have been temporary, not least because the chains have responded to the irritations they can produce: adapting menus, advertising, and their restaurants to local tastes. And by no means all the reactions have been destructive: ‘pushback’ can produce interesting alternatives to the enemy. But in a world where tensions between the ‘global’ and the ‘local’ are never far away, these American names remind us that only the US possesses truly universal food brands, with Coke still the world’s most powerful trademark of all, according to the agencies which rank such things. So, whatever it might wish, the high profile of McDonald’s, its unrivalled resources and symbolic associations, have tended to get the company caught up in the politics of change in all those cultures where conflicts of modernization have been particularly intense.

In his pioneering work on America’s role in debates over the future in 20th century France (Seducing the French 1993), Richard Kuisel focuses at one point on the controversy Coca-Cola set off when it arrived in the country in 1949. The Left was against it, the wine-producers deplored it, the government and the press opposed it. The Cold War was raging and Coke openly waved the US flag. But Kuisel writes that at stake were issues of modernity, sovereignty, and identity which have endured long after the Cold War, and are still felt well beyond France. “Our problem is to find a formula of life as between the old traditions and the new world rushing into us from every side,” said the Irish writer Sean O’Faolain in 1940. In the second half of the 20th century, repeated waves of technological, social, and cultural novelties coming from across the Atlantic, usually driven by market forces, have meant that the shock of the future usually arrived with an unmistakeable American accent. Was this an ‘Irresistible Empire’ as Victoria De Grazia suggested in her 2005 survey of the impact and reception of American models of consumerism in 20th century western Europe?

In the post-Cold War era of globalization, identity politics took off in Europe and in many places across the globe. As the renowned political scientist Stanley Hoffmann of Harvard put it, the more societies converged in their (Western-style) systems of living, the more each tried to cling to its native idiosyncracies. And in many lands, food became one of the key areas of contention in this struggle. The Minister of Agriculture in Italy’s Berlusconi government of 2009, from the separatist Northern League party, declared that he would not eat pineapple, let alone hamburgers, and encouraged the elimination of kebab stores and other alien food presences from his territory. (Meanwhile the Minister of Culture in the same government hired the founder of McDonald’s in Italy as his commercial adviser.)

But Italy showed that the politics of food could be much more constructive and intelligent than these gestures suggested. In 1989 the International Slow Food campaign was founded, inspired by journalist Carlo Petrini. He had originally gained fame in a protest against the arrival of McDonald’s close by Rome’s ancient Spanish Steps. Today Petrini’s movement comprises websites, magazines, seminars, food fairs, and a gastronomic university. It has gone global and inspired an ever-expanding food retail chain under the Eataly brand. Contrast this with the fate of France’s anti-McDonald’s lobby. Led from 1999 by a charismatic farmer, José Bové, who shot to notoriety by destroying a McDonald’s building site, the protesters chose to join the militant wing of the anti-globalization struggle. In 2007 Bové gained 1.3% of the vote at the Presidential election and disappeared into the European Parliament.

So the continuing success of McDonald’s in Europe — its second largest area by presence outside the US — demonstrates yet again the splitting effect that America’s cultural challenges produce, between nations and within them. Slow Food gets the headlines but McDonald’s gets the youthful crowds. Traditionalists and cultural élites (not always the same) tend to deplore the low-cost, quantity-over-quality thrust of the chain, just as they have done since the days of Woolworth’s and Hollywood, and as they do today in nations like India, where small shops fight the spread of supermarkets. Now, ten years after the Iraq war, America’s presence in the world seems less controversial than it once was, and so does McDonald’s. Whether the brand still acts as a stand-in for the nation we shall only see in the next crisis. In the meantime the company believes it has found a synthesis of its own best traditions and those of the young and old who rush into its restaurants, looking for speed, value — and a safe hamburger — wherever they are.

David Ellwood is an Associate Professor of International History at University of Bologna and Adjunct Professor in European-American Relations at Johns Hopkins University, SAIS Bologna Center. He is the author of The Shock of America: Europe and the Challenge of the Century. His first major book was Italy 1943-1945: The Politics of Liberation (1985) then came Rebuilding Europe: Western Europe, America and Postwar Reconstruction (1992). The fundamental theme of his research — the function of American power in contemporary European history — has shifted over the years to emphasize cultural power, particularly that of the American cinema industry. He was President of the International Association of Media and History 1999-2004 and a Fellow of the Rothermere America Institute, Oxford, in 2006.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pas de Starbucks à Montmartre poster from PARIS FIERTÉ via PARIS FIERTÉ website. Used for the purpose of illustration.

The post McDonald’s revisited: when globalization goes native appeared first on OUPblog.

April 3, 2013

Plebgate

“‘Pleb’–gate” — as the altercation between Andrew Mitchell, MP, and police officers guarding Downing Street has become known — continues to rumble along. It seems to me that there is a huge unanswered question lurking therein. It is this: what on earth are police officers doing providing an armed guard for the Prime Minister?

One might say that they do it, because they always have. Certainly, for as long as I can remember there has been the figure of the police constable standing outside the door of Number 10. For many years, it was an icon: an apparently unarmed police officer guarding the civil head of government. What better image of democracy could one imagine? However, that is no longer the image. When officers stand at the door of Number 10, they do so wearing body armour and conspicuously carrying a sidearm, when they not pictured gripping a sub–machine gun or assault rifle. This is not a reassuring image. It looks awfully like an embattled state.

One might say that they do it, because they always have. Certainly, for as long as I can remember there has been the figure of the police constable standing outside the door of Number 10. For many years, it was an icon: an apparently unarmed police officer guarding the civil head of government. What better image of democracy could one imagine? However, that is no longer the image. When officers stand at the door of Number 10, they do so wearing body armour and conspicuously carrying a sidearm, when they not pictured gripping a sub–machine gun or assault rifle. This is not a reassuring image. It looks awfully like an embattled state.

At a time when the government is telling the nation that it can no longer afford policing on the scale to which it has become accustomed, politicians show little inclination to deplete those who guard them, both at Downing Street and the Palace of Westminster. I suspect that victims of crime who are left waiting for officers to attend their personal calamity, will no longer consider that ‘we are all in this together’.

This is more important than mere equity. Guarding royalty, diplomats, and politicans is hardly compatible with the role of the police officer. In the Metropolitan Police the Diplomatic Protection Group (DPG) is dismissed as ‘doors, posts and gates’. Standing for hours at a static post does not take much in the way of policing knowledge and skills, there are few members of the public to disturb officers and if a crime has been committed these officers are the least likely to rush to the scene.

There are ample discarded members of HM armed forces who could easily fulfil such a role with the minimum of training and probably a significantly less cost. After all, the armed tactics that the ‘civil’ police who guard these locations are taught have been copied from the military. So, former soldiers would provide just as secure protection from a terrorist attack as the ‘bobbies’ who now do the job.

However, ‘plebgate’ reveals much more. Mr Andrew Mitchell, does not dispute that he said something along the lines of ‘I thought you guys were here to help us?’ In other words, the officers in Downing Street are regarded by this minister as a mere servant of them. Since no other politician has disputed this remark, amongst everything that has been disputed, then I suspect it is a widely shared view. In Downing Street, the rebuke ‘Officer, I pay your wages’, seems actually appropriate. However, the police are not servants of any class of the population — motorists who park on double-yellow lines, local squires, or ministers of the crown. The officers in Downing Street should have replied to Mr Mitchell, that they do not serve him, or the government. They do what it says on the helmet: they serve the Crown. It is the ‘Queen’s Peace’ that they are sworn to protect, not the convenience of politicians.

So, let the axe fall where it should: return all those officers who now serve ‘the political class’ to the duties for which taxpayers imagine their taxes are levied: the protection of all citizens. Replace them, if our politicians feel uniquely vulnerable, with guards who explicitly serve the interests of this privileged elite.

Professor P.A.J. Waddington, BSc, MA, PhD is Professor of Social Policy, Director of the History and Governance Research Institute, The University of Wolverhampton. He is a general editor forPolicing.

A leading policy and practice publication aimed at senior police officers, policy makers, and academics, Policing contains in-depth comment and critical analysis on a wide range of topics including current ACPO policy, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, specialist operations, accountability, and human rights.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: British Policeman, also known as a ‘Bobby’ observing London life. Photo by GP232, iStockphoto.

The post Plebgate appeared first on OUPblog.

It is hard to stop thief

The title of this post is meant to warn our readers that the origin of the word thief has never been discovered. Perhaps an apology is in order. I embarked on today’s seemingly thankless topic after I received a question from Denmark about the possible ties between Danish to “two” and tyv “thief.” Although our corresponded knows that they cannot be related, the implications of the to / tyv case and the attempts to discover the etymology of thief are worthy of a short essay.

To and tyv begin with the same consonant (t), but from a historical point of view the identity of t1and t2 is misleading. In the past, the relevant forms were tvau and þjóf, similar to Modern Engl. two and thief (the letter þ designates the same sound as Engl. th). For some reason, th has been lost in most of Modern Germanic (but not in Icelandic or English). In the continental Scandinavian languages it turned into t, while old t remained unchanged. In German old th became d. That is why the German for thief is Dieb. Hence the rule: English (or Icelandic) th corresponds to Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian t and German d. I have dwelt on this uninspiring subject because it is exactly such correspondences that bear the grandiloquent name “phonetic laws.” Since theory is always more straightforward than practice, the “laws” often give researchers trouble. When words are obviously related but something goes wrong with phonetics, the deviation has to be explained.

For instance, Engl. thousand = Danish tusind (everything is fine!) = German tausend. But the German word was expected to begin with d! Why doesn’t it? The reason, which I won’t discuss here, came to light long ago, and the integrity of phonetic laws was saved. In other cases we may be out of luck. Thus, the vowels of heath and heather are incompatible (again I’ll skip the explanation why). Can we venture the conclusion that heather and heath look almost like homonyms by chance? It seems we should! The game has to be played according to the rules, for, if we disregard them, the game will stop. Historical linguists hope to win a fair wrestling match with the material, rather than participating in a skirmish. Sounds change more rapidly than non-specialists think. That is why etymologists always try to deal with the oldest forms recorded in texts. Danish to and tyv look close enough, but as long as we realize that their t’s have different sources, we won’t even try to compare them.

In Broad Daylight

The main Germanic word for “thief” is old. Gothic had þiufs (spelled þiubs), and with Gothic we are in the fourth century CE. The other related languages had similar forms, none of which resembles any non-Germanic word designating a person who steals. Given such evidence, the etymologist faces at least three possibilities.

Perhaps the root of þiufs (to be more precise, of its protoform) existed in Sanskrit (Greek, Latin, Celtic, Slavic—one or all of them) but had a different sense. If so, we should remember that Germanic f corresponds to non-Germanic p (as in Engl. father versus Latin pater) and look for words with the root teup- (in þiufs, i goes back to e, and -s is an ending) or even teu-, because -p may turn out to be a suffix.

Or þiufs, from the unattested þeofs, is a Germanic coinage and never had cognates in other languages. Considering the meaning of the word thief, it could come into existence as slang. Perhaps that is how thieves once called themselves, but with time the word gained respectability and became part of the Standard. To cite a parallel: In the middle of the eighteenth century, Samuel Johnson, the author of a famous English dictionary, called the noun slum low. Slums are still slums, but the word is no longer “low”: it is neutral.

The word may have been borrowed from another language (not necessarily as part of international thieves’ cant).

Despite the absence of unquestionable cognates (nouns or verbs that refer to stealing) students of Germanic tried to find some phonetically acceptable words that could have been related to thief. The most successful find was Greek typhlós “blind,” with the idea that þeof- meant either “hidden” or “imaginary.” Perhaps a more appropriate gloss would have been “a thing unseen; secret.” The Gothic adverb with the root of þiufs meant “clandestinely” (compare Engl. steal and stealthily). But several circumstances make this etymology suspect. Most important, the oldest Germanic sense of thief was not “someone who steals things under cover of darkness” (in Dickens’s days they said under cover of the darkness), but rather “criminal, violator” and “robber.” (The distinction between “thief” and “robber,” attested in Greek and Latin, doesn’t seem to have existed in the oldest Germanic society, while burglars in our sense of the word were unknown.) As far as we can judge, the ancient Germanic þeof- was not the proverbial thief in the night. The overtones of secrecy inherent in our thief and steal do not predate the introduction of Christianity.

Putative cognates, such as mean “cower,” “strike,” and “violence” (all of them have been offered), match the earliest sense of “thief” tolerably well, but one wonders why they occur in Lithuanian, Greek, and Avestan (an Iranian language). Not that distant and isolated connections among words are impossible. It just so happens that we cannot reconstruct the path from Lithuanian “press together” and “attack,” Greek “strike,” or Iranian “violence” to Germanic “thief.” If those words meant “robber” or if Germanic had words obviously akin to them, there would have been no problem. But even with the written history of a word for “thief” at our disposal, we often wonder at the zigzags in its development. Russian vor “thief” (with congeners elsewhere in Slavic) is probably related to the verb vrat’ “to lie, tell falsehoods,” and the noun’s oldest recorded senses were “cheat, swindler; adulterer.” French voleur “thief” is a metaphor borrowed from falconry. In other cases, the origin of the word for “thief” is as obscure as it is in Germanic. For example, the Romans connected latro “thief” with Greek látron “payment, compensation” (other words aligned to it meant “service; servant, slave”) and Latin latus “side” (compare Engl. lateral). The second derivation was definitely, and the first, quite possibly, a tribute to folk etymology. In Latin, latro “thief” was opposed to fur “robber,” a borrowing from Greek, as though the Romans could not coin their own noun for someone who sat in an ambush and waylaid them. It seems that honest people (and etymologists’ honesty has never been called into question) find it hard to follow thieves’ ways.

I am inclined to think that þeof- was a native coinage, possibly a slang word, perhaps even a taboo alternation of some other well-known noun (unless it was a borrowing from another language whose speakers were famous for their dishonest ways). That this supposition is not entirely groundless can be seen from the history of Old Icelandic þjófr. It should have been þjúfr, and no one knows who and when violated the “right” form.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: “Stop thief! stop thief! a highwayman!” from Randolph Caldecott’s picture books, series. Source: NYPL Digital Gallery.

The post It is hard to stop thief appeared first on OUPblog.

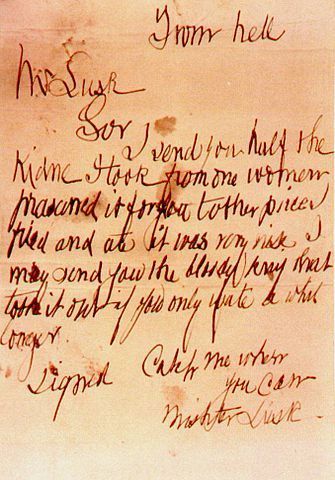

Jack the Ripper and the case of Emma Smith

The World of Jack the Ripper

Many people are puzzled by the phenomenon of ripperology. What kind of person has a grim fascination with a serial killer famous for not getting caught? For me, and many fellow ripperologists, the appeal is not Jack per se, but the atmosphere of Whitechapel in the 1880s. The case is a window into a forgotten world and one that shows us how that world was experienced by the common man. Not for us the elegant homes and horse-drawn carriages. We want the daily grind, the sweat, and the muddy streets. This is why it is easy to distinguish between the casual and serious ripperologist; the latter will baulk at the slightest mention of a Royal conspiracy.

No, the far more interesting case, the one worth exploring, involves normal men and women and a society ill-at-ease with itself. The case of Emma Smith is illustrative. Smith is not considered a canonical victim, but her murder is certainly indicative of how normalised street violence was at the time. In many ways, the Ripper case is the first time that knife-crime become fodder for sensationalist media coverage. It had long existed, as we will see in Smith’s case, and it always had an obvious motivation: robbery, sexual assault, or drunkenness. This is why Jack is so startling: he is the first recorded serial killer without any discernible motivation beyond the impulse to take lives.

Turning up the heat

Smith can be said to mark the first escalation of violence in what became known as the ‘autumn of terror’ (31 August 1888 – 9 November 1888). Smith was murdered in what appears to have been an especially vicious mugging on April 3rd, 1888. She was relieved of her possessions, sexually assaulted, and beaten, but her attackers did not seem to have set out to kill her. She lived long enough to describe them as a gang and this piece of information is usually considered sufficient to make her case non-canonical. In the canonical cases, with one exception, witnesses claimed to have seen Jack alone with his victim — assuming, that is, they had seen him at all. Even in the sole witness account where we have more than one perpetrator, that of Israel Schwartz in the case of Elizabeth Stride, we are told of a second man and not of a gang.

However, Smith was certainly the victim of a new tendency for extreme violence in the Whitechapel area. The gang that targeted Smith was nothing new. Gangs often extorted money from prostitutes, but they rarely needed to act out their threats. It is possible that Jack gained a taste for violence as part of this gang. Perhaps his fellow gang-members disassociated from him upon realising he was more sadistic than they. However, this goes against our best psychological profiles. Serial killers are, almost always, loners and certainly not known for their ability to co-operate with others.

The Streets of Whitechapel

Smith was attacked, like many women in her trade, as she left one of the many local pubs populated by the working-poor of London. She may very well have found herself, like the canonical Ripper victims, in the dangerous situation of needing to recuperate the money she had spent boozing. Money was needed for a bed at one of the local doss-houses. The easiest way to do this was street prostitution and this took place in the early hours of the morning. This entailed hanging around pitch-black streets; street lamps being rare and sparse. The same can be said of the rag-tag police-force that patrolled the area in predictable beat patrols. These patterns were well-known to the local criminals and easily identified by anyone with a desire to avoid them.

Despite the darkness Whitechapel and surrounding areas were never entirely empty. Between the late-night drinking culture and the early morning trade-culture there was constant movement. This helps explain why the Ripper would have been able to stalk the streets with relative ease. Even blood-stained hands clasping a knife would not have raised an eyebrow. After all, a butcher rises early. Even when hysteria concerning the Ripper was at its height he was able to rely on these facts. Coupled with police inexperience with such cases, including a lack of forensics, and it becomes easier to understand how he slipped their net.

It is worth remembering that the first ever crime-scene photo was taken at the scene of his final murder — that of Mary Kelly (9 November 1888). Then the murders stopped. Time was catching up with Jack. We never hear from him again. His legacy, however, remains with us. Only these days he would likely have been caught.

Paul J. Ennis is a writer based in Dublin. He is the author of Continental Realism (Zero Books, 2011).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) The “From Hell” Letter postmarked 15 October 1888. Original in the Records of Metropolitan Police Service, National Archives, MEPO 3/142. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Streetmap showing the locations of the first seven Whitechapel murders 1894. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Jack the Ripper and the case of Emma Smith appeared first on OUPblog.

What a mess! The politics and governance of the British Constitution

Do we have a constitution? What is the British constitution? Does anyone actually care? At one level the answers to these questions are relatively simple and straightforward. ‘Yes’ — we do have a constitution but its constituent elements are scattered amongst a range of documents and within the tacit understandings of a number of parliamentary conventions; the British constitution is — through accident and design — a mess that has evolved in a muddled manner, betraying the existence of a latent form of ‘club government’; ‘No’, nobody cares because this is how it has always been and we don’t trust politicians and they’re all the same.

The problem with these answers is that although they may have shaped the dominant view of the British constitution in the twentieth century they appear unable to capture and reflect the changing social and political situation in the twenty-first century. When they are reframed as being concerned with the future governance of the United Kingdom then people clearly do care about the constitution. More specifically they care when theoretical debates and questions suddenly become elements of hard, day-to-day reality. For example, setting the date for a referendum on Scottish independence suddenly raises questions about the future of the United Kingdom, and the Court of Appeal’s decision to prevent the deportation of Abu Qatada confuses the public about the balance of power between the executive and judiciary. My sense from talking and (more importantly) listening to people as I travel around the UK is not that they don’t care about British politics and its constitutional arrangements but that they simply don’t understand where power lies or why.

This takes us back to the second question and the evolution of the British constitution. David Marquand once characterized New Labour’s approach to constitutional reform as being: “a revolution of sleepwalkers who don’t quite know where they are going or why.” The introduction of a great raft of constitutional measures without any clear statement of what (in the long run) the government was seeking to achieve, any idea of how reform in one sphere of the constitution would have obvious and far-reaching consequences for other elements of the constitutional equilibrium, or any detailed analysis of the nature or model of democracy that existed towards the end of the twentieth century, therefore formed central components of the ‘Blair paradox’. As such, the public’s confusion about the distribution of powers — not to mention the existence of complex blame games and credit claims — reflects a deeper situation of democratic drift. Jack Straw may have argued with me publicly that my diagnosis is wrong and that New Labour’s reforms were underpinned by a set of underlying principles, but such theoretical back-filling remains unconvincing. The UK is suffering from constitutional anomie in the sense that reforms have been implemented — before and after New Labour — in a manner that is bereft of any underlying logic. Constitutional anomie is therefore an ailment of both mental and physical health vis-à-vis the body politic. Social and political anxiety, confusion, and frustration emerge with the result that reforms that were designed to enhance levels of public trust and confidence in politics, politicians, and political institutions can actually have the opposite effect.

If the phrase ‘constitutional anomie’ risks over-complicating what is in reality a simple issue then let us call it what it is: a constitutional mess.

It is in exactly this context that today’s report Do we need a constitutional convention for the UK? by the House of Commons’ Political and Constitutional Reform Committee makes the case for a more thorough and explicit review of our constitutional framework. Although questions may revolve around the specific structure or nature of this review, what cannot be questioned is the urgent need to look across the constitutional landscape in order to assess what exists and why, and to look to the future in terms of what we want the UK to look like in 10 or 20 years time. The impending 2014 referendum on independence for Scotland makes a thorough consideration of the future of the United Kingdom and all its component nations all the more pressing. I am well aware that in supporting the need for a review, commission, or convention of some kind to take stock of the past, present, and future of our constitutional framework I am being terribly un-British in approach — for many the thought of adopting a set of explicit constitutional principles is almost heretical — but the malleability of the British constitution has arguably been exhausted, the relationship between its constituent parts confused, and the mess that now undoubtedly exists demands urgent review and reform.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance

at the University of Sheffield. He was awarded the Political Communicator of the Year Award in 2012 and is a member of the Advisory Board for the Economic and Social Research Council’s ‘The Future of the United Kingdom and Scotland’ Programme. Jack Straw’s response to his criticisms can be found in the journal Parliamentary Affairs (Vol.63, 2010). Author of Defending Politics (2012), you can find Matthew Flinders on Twitter @PoliticalSpike and read more of Matthew Flinders’s blog posts here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Houses of Parliament. Photo by Adrian Pingstone. Creative Commons License via WikiWitch on Wikimedia Commons

The post What a mess! The politics and governance of the British Constitution appeared first on OUPblog.

April 2, 2013

Kenyatta confirmed as Kenyan president but ethnic politics remain

On Saturday 30 March 2013, Kenya’s Supreme Court unanimously decided that Kenya’s presidential election — which had been held on 4 March — was conducted in a free, fair, transparent and credible manner, and that Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto of the Jubilee Alliance were validly elected. Raila Odinga of the Coalition for Reform and Democracy (CORD) publicly disagreed with the court’s findings, but emphasised the supremacy of the constitution and wished Kenyatta and Ruto luck in implementing the 2010 constitution. Raila’s decision to seek legal redress for alleged electoral manipulation, rather than to call for mass action, and his respect for the court’s ruling stands in stark contrast to 2007 when a disputed election triggered unprecedented violence. The 2013 election and its aftermath were generally peaceful with the notable exceptions of attacks on state security personnel at the Coast the night before the election and a harsh state security response to violent demonstrations in parts of Nyanza Province and Nairobi following the reading of the Supreme Court’s verdict.

The 2013 election reveals a strong commitment to peace amongst Kenyans, which is fuelled by people’s experiences of the 2007/8 post-election crisis that — at least for a time — seemed to threaten to throw the country into civil war, and by a strong “peace narrative,” which has been fostered by church leaders, civil society organisations, and politicians. However, it also reflects a profound sense of disillusionment and impotence amongst many Kenyans. Demonstrations were banned on the basis that they “inevitably” lead to violence. Strategically located state security personnel rendered public protest an incredibly dangerous option. Meanwhile the emphasis on “peace” made people cautious of highlighting problems lest they be labelled as warmongers.

But as well as differences, there are also strong continuities between 2007 and 2013. One is the ongoing political salience of ethnic identities and narratives of difference, competition, marginalisation, and particular suffering, which pose significant challenges for the Jubilee Alliance moving forward.

The prominence of ethnic identities was reflected in pronounced ethnic voting patterns (the vast majority of Kikuyu and Kalenjin voted for the Jubilee Alliance, and the majority of Luo voted for CORD), but also in vicious debates on social media sites following the announcement of the results and public responses to the Supreme Court’s decision. Thus, while Uhuru announced that his government would work with and serve all Kenyans, the perception on the ground is clearly different. Many Jubilee supporters in Kalenjin and Kikuyu-dominated areas, for example, celebrated the Supreme Court’s decision by holding up loaves of bread and declaring that while in the coalition government they had had to share a loaf, they now had the whole thing!

The challenge of communal narratives and perceptions includes the difficulty of working with those ethnic groups who predominately supported Raila and CORD, such as the Luo and coastal communities. First, these communities have strong narratives of marginalisation and past suffering at the hands of previous ethnically-biased (and Kikuyu and Kalenjin-headed) regimes. Second, there is a strong perception within these communities that the Kikuyu and Kalenjin have benefited from the “fruits of Uhuru [independence]” more than other Kenyans and are unable to allow others to govern. Finally, many people from these communities firmly believe that the 2013 election was marked by gross irregularities, that the election should have gone to a run-off, and that their vote has once again been stolen. This poses a challenge to the new government as people tend to focus in on evidence that reinforces existing narratives. Many CORD supporters are already talking about boycotting the next presidential election, and such narratives and perceptions can further fuel a sense of ethnic difference and competition — and perhaps future conflict.

However, inter-ethnic tension and violence is not inevitable and people will be closely watching how the new Jubilee government includes members of all communities and how devolution plays out in practice: whether it serves to bring government closer to the people and a fairer distribution of resources, or whether it is marked by conflicts between the centre and the counties, different power brokers at the county level, and self-perceived “locals” and “outsiders” in cosmopolitan counties.

Second, while the Kalenjin and Kikuyu came together behind the Jubilee Alliance, it is clear that ethnic stereotypes, narratives of difference, competition, and mistrust continue to be a feature of day-to-day relations at the local level. In turn, there is a fear among many members of the Kalenjin community that their support for Uhuru’s presidency may be “betrayed” with potential “evidence” including a failure to fully share government positions and resources, and possible scenarios at the International Criminal Court (ICC) where both Uhuru and Ruto face charges of crimes against humanity. However, there is nothing inevitable about the collapse of the Jubilee Alliance, especially since Uhuru’s TNA party needs Raila’s URP party if it is to continue to enjoy a majority in the National Assembly and Senate.

In short, the new Jubilee government lacks legitimacy in many parts of the country and faces the possibility of internal divisions — two challenges that are both characterised by (among other things) strong ethnic narratives of difference, competition, marginalisation, betrayal, and particular suffering. Other challenges include Uhuru and Ruto’s cases at the ICC, the delivery of campaign promises, the government’s relations with civil society organisations who opposed Uhuru and Ruto’s candidacy and petitioned their victory, and government relations with the international community. Many countries having congratulated Uhuru on his victory, while simultaneously emphasising the need for Kenya to continue to comply with its international obligations, such as the ICC.

Gabrielle Lynch is an Associate Professor of Comparative Politics, Department of Politics and International Studies at University of Warwick. Her article “Becoming indigenous in the pursuit of justice: The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the Endorois” was recently included in a virtual issue on Kenya from African Affairs.

African Affairs is published on behalf of the Royal African Society and is the top ranked journal in African Studies. It is an inter-disciplinary journal, with a focus on the politics and international relations of sub-Saharan Africa. It also includes sociology, anthropology, economics, and to the extent that articles inform debates on contemporary Africa, history, literature, art, music and more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only African history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Kenyatta confirmed as Kenyan president but ethnic politics remain appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers