Oxford University Press's Blog, page 957

April 12, 2013

The Mashapaug Project

Mashapaug Pond, Yoyatche Mehquantash – Always Remember by Loren Spears. Used with permission of the photographer.

By Caitlin Tyler-Richards

Continuing our celebration of the release of 40.1, today we’re excited to share a conversation between managing editor Troy Reeves and contributors Anne Valk and Holly Ewald. Valk and Ewald are the authors of, “Bringing a Hidden Pond to Public Attention: Increasing Impact through Digital Tools,” which describes the origins and methods of the Mashapaug Project, a collaborative community arts and oral history project on a pond in Providence, Rhode Island. Through the course of their conversation with Troy, Valk, and Ewald demonstrate how we may push the definition and impact of oral history work.

Those interested in public art and public humanities should also be sure to give this a listen!

[See post to listen to audio]

Anne Valk is Associate Director of Programs at the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage at Brown University. Her book Living with Jim Crow: African American Women and Memories of the Segregated South (Palgrave Press, 2010), written with Leslie Brown, won the Oral History Association Book Award in 2011. Holly Ewald is an artist who works within the context of public spaces, and with the people who inhabit and treasure those places. As founder of Urban Pond Procession, she encourages other artists to use the historical and environmental challenges of Mashapaug Pond to engage the public in creative responses to this neglected site. Through Our Eyes, An Indigenous View of Mashapug Pond (2012), a book she co-edited with Dawn Dove, was the culmination of a project with an intergenerational Indigenous group at the Tomaquag Museum in Rhode Island.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview and like them on Facebook to preview the latest from the Review, learn about other oral history projects, connect with oral history centers across the world, and discover topics that you may have thought were even remotely connected to the study of oral history. Keep an eye out for upcoming posts on the OUPblog for addendum to past articles, interviews with scholars in oral history and related fields, and fieldnotes on conferences, workshops, etc.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Mashapaug Project appeared first on OUPblog.

eIncarnations

Cleora Emily Bainbridge was born 8 November 1868, and passed away on 14 April 1870. Her father was a clergyman, and her mother, Lucy Seaman Bainbridge, was director of the Woman’s Branch of the New York City Mission Society. In 1883, her father, William Folwell Bainbridge, imagined what her life might have been like by casting her as the heroine of his novel Self-Giving, where she became a Christian missionary and died a martyr.

Cleora’s brother, William Seaman Bainbridge, born 17 February 1870, became an internationally prominent surgeon and medical scientist, living a full life until 22 September 1947. Had Cleora lived, she would have accompanied her brother and parents as they toured American Baptist missions around the world, 1879-1880, which prepared her brother for many more such voyages. He co-founded the International Committee of Military Medicine in Belgium in 1921, and two years later, he had the equivalent of an email address, Bridgebain, receiving telegrams sent to it from anywhere in the world.

Long dead, a sister and brother have now returned to life inside virtual worlds, as avatars: Cleora in fantasy role-playing game EverQuest II, and William in two science fiction virtual worlds where medical science advanced to frightening levels, Fallen Earth and Tabula Rasa.

Cleora Emily Bainbridge (1868-1870)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The only surviving photograph

la

la Cleora's Avatar, a Half-Elf Conjuror Mage in EverQuest II

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la William Seaman Bainbridge (1870-1947)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

At his most idealistic and ambitious, playing the role of Columbus at festivities marking the 400th anniversary of his discovery of the New World in 1892 at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York, a remarkable educational resort founded in 1874.

la

la Bridgebain in His Crude Chemtown Laboratory in Fallen Earth

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la Bridgebain and the Clone He Made of Himself, after a Battle in Tabula Rasa

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

la

la  ');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-37916";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "thumbslider";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

Long ago, the gods abandoned Norrath, the world of EverQuest II. The game imagines the gods as creeping back to regain their lost status as lords of all the lands; it presents a cynical view of religion. Given Cleora’s history, I cast her avatar as ambivalent about deities. Her perspective made her an excellent vantage point for research.

The post-apocalyptic gameworld of Fallen Earth depicts conflict between numerous small gangs and cults in a chaotic corner of the United States, some years after the fall of civilization caused by a plague that may have resulted from unconstrained genetic engineering. Set in and around the Grand Canyon in Arizona, including simplified versions of many real locations, the game requires avatars to scavenge materials from the environment so they can craft weapons and medicines in order to survive the new Dark Ages. Bridgebain joined the Tech faction—scientists and engineers who believe only technology can restore civilization—and set up his headquarters in an advanced Tech base named Chemtown.

Tabula Rasa imagined that the Earth was invaded by a vicious extraterrestrial army called the Bane, but a few humans were able to escape to the planets Foreas and Arieki, where they formed alliances with the indigenous civilizations against the invaders. In addition to exploring these alien worlds and battling the Bane, Bridgebain collected Logos symbols from widely dispersed and often hidden shrines, where they were left by an ancient civilization named called the Eloh. Assembled into sentences, these Logos elements are like scientific theories or engineering designs that give the user advanced powers. Bridgebain collected all the Logos symbols, learned new medical skills like cloning himself, and eventually battled back from the stars to a point in New York City only a few blocks from Gramercy Park where the real doctor had lived.

Cleora and the two Bridgebains are Ancestor Veneration Avatars (AVAs), a new way of memorializing, enjoying, and learning from deceased family members, especially for a secular society in which traditional ways of dealing emotionally with death have lost plausibility. When operating an AVA inside a virtual world, the user can draw upon personal knowledge of the dearly departed (many written records as in the case of Bridgebain), and a hopeful sense of what a life might have been like in a particular social context (as in the case of Cleora). The goal is as much to enrich the life of the user as to fulfill a duty to the deceased. Indeed, the user gains a richer sense of human life by experiencing a challenging virtual world from the perspective of another person.

William Sims Bainbridge is a prolific and influential sociologist of religion, science, and popular culture. He serves as co-director of Human-Centered Computing at the National Science Foundation. His books include eGods: Faith versus Fantasy in Computer Gaming, Leadership in Science and Technology, The Warcraft Civilization, Online Multiplayer Games, Across the Secular Abyss, and The Virtual Future. He is the grandnephew of Cleora Bainbridge and grandson of William Seaman Bainbridge.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

All images courtesy of author.

The post eIncarnations appeared first on OUPblog.

Children and schools just keep getting better

By Gary Thomas

Frank Spencer’s famous assertion to Betty that ‘Every day in every way, I am getting better and better!’ is true. We are indeed getting better and better all the time.

Click here to view the embedded video.

At the primary schools athletics championships for New South Wales in December 2012, a 12-year-old boy, James Gallaugher, ran the 100m sprint in 11.72 seconds. This is a time that would comfortably have won him the gold medal in the 100m at the Olympic Games in Athens in 1896.

The phenomenon of continual improvement extends to IQ. Amongst psychologists the Flynn effect (so-called because it has been extensively studied by the New Zealand psychologist James Flynn) is well known: it refers to the large increases in IQ that have occurred over one hundred years of intelligence testing. Intelligence tests have an average of 100, and they do so unfailingly. You would be wrong, however, to conclude from this that intelligence remains constant in the population. The consistent average IQ of 100 is the result of the work of the psychometricians, who toil to maintain the figure of 100. The tests and their marking regimes have to be continually reconstructed to bring the average to 100 and to make the distribution of scores conform to shape of the bell-shaped normal distribution curve.

The reconstruction is needed because our performance is improving all the time. When people are asked to take intelligence tests from a previous generation their scores are consistently above those of the earlier cohort.

Which brings me to GCSEs and A levels. The results keep improving there as well. They keep improving because, unlike with IQs, no one was working (until now) to hold them at a consistent figure. If the kids answer the questions well, they get an ‘A’.

It’s all part of the narrative that rubbishes schools that says that the steady improvements in examination results are down to ‘grade inflation’. There may be an element of grade inflation, but my guess is that most of the improvement is down to a variant of the Flynn effect, which also explains James Gallaugher’s extraordinary sprint speed. You can imagine why this happens: with IQ, it’s because so much more information and so many more tools for thinking and learning are about now — kids have access to machines and experiences that previous generations couldn’t even dream of.

It’s all part of the narrative that rubbishes schools that says that the steady improvements in examination results are down to ‘grade inflation’. There may be an element of grade inflation, but my guess is that most of the improvement is down to a variant of the Flynn effect, which also explains James Gallaugher’s extraordinary sprint speed. You can imagine why this happens: with IQ, it’s because so much more information and so many more tools for thinking and learning are about now — kids have access to machines and experiences that previous generations couldn’t even dream of.

Instead of watching Crackerjack on the TV, as I used to do when I got home from school, today’s generation are straight onto their computers. Scattered amongst the games and the music will be the occasional Internet search, which will lead to something else … and something else — they interact with their machines. Kids are encouraged to think, to find things out, to write and communicate in a dozen different ways. They go places, see things and have access to knowledge to which once upon a time only the most privileged had access. It’s no wonder they are getting cannier.

And James Gallaugher’s extraordinary 100m sprint is just as easy to explain. Children are better fed, taller, healthier, have access to better facilities and coaching, which in turn benefits from a hundred years of research into ways of improving running. Running shoes are marvellously improved and tracks are made of high-grip material rather than ashes. Why are we surprised that things continually improve?

So, today’s kids are not only healthier, they are also more articulate and more knowledgeable than those of previous generations. Schools are better: not only are classes smaller, but children and young people are encouraged to think where once they would have been drilled in handwriting, Latin, and the names of national heroes from history. Teaching is improving all the time: today’s teachers are better educated and better trained, understanding the ways in which children learn. The differences between schools of today and those of my generation, forty years ago, are huge. This is why IQs, exam results — and sprinting speeds — continually improve.

Gary Thomas, Professor in Education, University of Birmingham. He has spent his career working in education, first as a primary school teacher, then as an educational psychologist, then as an academic in five universities. He is the author of Education: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: By alegri/4freephotos.com [Creative Commons] via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Children and schools just keep getting better appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2013

The challenges and rewards of biographical essays

One of the first things I did after being appointed general editor of the American National Biography was to assign myself an entry to write. I wanted to put myself in the shoes of my contributors and experience first-hand the challenge of the short biographical form.

I settled on Carolyn Gold Heilbrun (1926-2003), a feminist literary scholar who also wrote mystery novels under the pen name of Amanda Cross. Her writings on biography and women’s literature have been important to my own intellectual journey as a feminist scholar and I have even toyed with the idea of using her best known book, Writing a Woman’s Life (1988), as the model for a book on feminist biography I hope to write someday. I also love her mystery novels, which bear a strong debt to Dorothy Sayers, whose books had also been a formative influence on me when I was growing up. One of the most important prerequisites for writing good biography, I have learned, is the spark between biographer and subject, and it seemed like Heilbrun and I would make a good match.

Carolyn Heilbrun – the most brilliant. Legenda, 1947. Image courtesy of Susan Ware. Do not reproduce without permission.

Additionally, I had a more personal connection to the subject: Heilbrun had been a classmate of my mother’s at Wellesley College in the 1940s. My mother loved to tell the story of letting “Cacky” (her nickname) Gold into their dorm by a basement window after she had stayed out past curfew with the Harvard student, James Heilbrun, whom she married in February of her sophomore year. I suspect that Carolyn had not officially told college officials about her marriage, because her new husband was about to be shipped off to the Pacific. So in the meantime she managed to steal time with him in Cambridge with the help of her dorm mates who covered for her. By her senior year, he was back from the war and they lived off campus while she finished her degree. Carolyn Gold Heilbrun graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1947, as did my mother, Charlotte McConnell.

A photo of six Freshman from the Class of 1947 at Wellesley, including Susan Ware’s mother, Charlotte McConnell, second from left. Legenda, 1947. Image courtesy of Susan Ware. Do not reproduce without permission.

I always chuckled over this story, because by the time I was a student at Wellesley in the late 1960s, living in the same Severance Hall dorm, it wasn’t so much a question of letting students in through basement windows after hours but trying to sneak in male visitors for the night. I seriously doubt that my mother and her friends would have conspired with Carolyn so readily if she had been sneaking off to see her boyfriend, but the sanction of marriage made it okay.

[image error]

Tower Court complex – Wellesley College. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Fast forward about forty years to 1987, when I published a biography of New Deal politician (and Wellesley graduate) Molly Dewson, a work very much informed by the feminist scholarship of which Heilbrun was now a leading proponent from her tenured position in the English Department at Columbia. Seeking to make a connection between her and my mother, I sent her an inscribed copy of my book. I never heard a word in return.

Some years later my mother and I were both reading Heilbrun’s Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty. One night I got an excited phone call. “Look at page 212,” my mother exclaimed. “She mentions your book!” Sure enough, Heilbrun used the story of Molly Dewson and her partner Polly Porter as an example of how women’s relationships could be just as strong and long-lived as heterosexual marriages. Unfortunately she slightly garbled the title of my book, calling it My Partner and I rather than Partner and I, but I think Heilbrun’s rendition is actually better.

A lot of the background research and preparation for a biographical entry never makes it into the formal essay. It also takes a lot more time to craft a biographical essay than, say, this blog post. Every detail has to be nailed down. Hard choices have to be made about which episodes and events to include versus which to leave out. Should I include quotations to give the flavor of her writing? How much space should I devote to her personal life, when she always claimed that the essence of her life was her work? So many choices, so few words.

In practically the same amount of space as this blog post, we ask our contributors to craft an interpretation of an entire life, chock full of dates and details accompanied by the larger context in which the subject operated. The experience of writing a biographical essay, and then writing about the process, confirms how challenging – and rewarding — the invitation to contribute an essay to the ANB can be. I plan to draw on this insight in my interactions with contributors in the years to come.

Susan Ware is the General Editor of the American National Biography and celebrated her first year anniversary of working on the ANB this April. She is an accomplished historian, editor, and the author of seven books, including biographies of Billie Jean King, Amelia Earhart, Molly Dewson, and Mary Margaret McBride. She served as the editor of several documentary collections and of the most recent volume of Notable American Women, published in 2004, which contains biographies of 483 women from over 50 fields. Educated at Wellesley College and Harvard University, Dr. Ware taught at New York University and Harvard. Susan’s article on Carolyn Gold Heilbrun will be added to the ANB Online in October 2013.

The landmark American National Biography offers portraits of more than 18,700 men and women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. First published in 24 volumes in 1999, the ANB received instant acclaim as the new authority in American biographies, and continues to serve readers in thousands of school, public, and academic libraries around the world. Its online counterpart, ANB Online, is a regularly updated resource currently offering portraits of over 18,700 biographies, including the 17,435 of the print edition. ACLS sponsors the ANB, which is published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The challenges and rewards of biographical essays appeared first on OUPblog.

Name that dance

“Shake Shake Shake Señora”! We’ve all heard that song, but do you know how to dance to it? Should you do the Rumba, the Hustle, or possibly the Merengue? Dancing is a universal form of expression and is also unique to different cultures worldwide. In 1982, the International Theatre Institute created the worldwide holiday known as “International Dance Day” on the 29th of April. In honor of the upcoming holiday, we’ve gathered information from the Oxford Index to test your dance knowledge. Take our brief “Name that dance” quiz, it’s not as easy as you think!

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

The Oxford Index is a free search and discovery tool from Oxford University Press. It is designed to help you begin your research journey by providing a single, convenient search portal for trusted scholarship from Oxford and our partners, and then point you to the most relevant related materials — from journal articles to scholarly monographs. One search brings together top quality content and unlocks connections in a way not previously possible. Take a virtual tour of the Index to learn more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

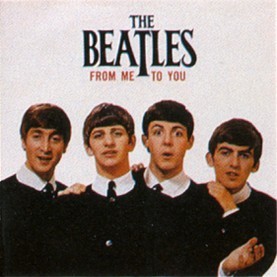

From Me (the Beatles) to You (the Stones): April 1963

After the success of the single “Please Please Me” and the release of the album Please Please Me, British fans and the press eagerly anticipated “From Me to You.” Fans had pre-ordered so many copies of the disk that when Parlophone did release R 5015 on 11 April 1963, the single immediately appeared in pop charts where it would stay for an amazing 21 weeks. In the sometimes-volatile New Musical Express charts, “From Me to You” charged into the ratings almost immediately, displacing Gerry and the Pacemakers and their version of “How Do You Do It” from the top position in the 26 April issue. But British journalists found challenges in describing the music and the artists.

The music press knew this disc would be a success, as indeed would every Beatles release until 1967. This success presented many critics with a significant problem: what of any consequence could they say about a Beatles record? Fans were going to buy the records no matter what they said. More problematically, the Beatles represented music that British music critics had difficulty understanding. The industry had disdained rock and roll in favor of smoother artists, for example transforming Cliff Richard from a snarling, Elvis-imitating rocker singing “Move It” into the harmless film star of Summer Holiday (January 1963). But the Beatles represented something different and writers seemed to lack a vocabulary for what they heard on these recordings and in concert halls, let alone what was transpiring in the minds of teens listening to these discs at home.

The music press knew this disc would be a success, as indeed would every Beatles release until 1967. This success presented many critics with a significant problem: what of any consequence could they say about a Beatles record? Fans were going to buy the records no matter what they said. More problematically, the Beatles represented music that British music critics had difficulty understanding. The industry had disdained rock and roll in favor of smoother artists, for example transforming Cliff Richard from a snarling, Elvis-imitating rocker singing “Move It” into the harmless film star of Summer Holiday (January 1963). But the Beatles represented something different and writers seemed to lack a vocabulary for what they heard on these recordings and in concert halls, let alone what was transpiring in the minds of teens listening to these discs at home.

Record Retailer and Music Industry News, in a prophetic bit of hyperbole, noted (11 April) that “Beatle hysteria has never been higher—and this is a likely Number One.” Keith Fordyce, in The New Musical Express (12 April), commented that the disc possessed “plenty of sparkle” and a “commercial” lyric, and would entering the charts “quickly.” Nevertheless, despite approving the singing, the harmonizing, and the lyric, he did not “rate the tune as being anything like as good as on the last two discs” [“Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me”]. And Don Nicholl in Disk (13 April) applauded “From Me to You” as a “lusty beater” destined to be a hit, and notes that the harmonica, guitar, and singing would send the recording to the top of the charts. Notably, Nicholl remarked on the “surprising falsetto phrases” in the song, presumably referring to the insertion of the syllable “whoo” at the end of the chorus that the Beatles had copied from the Isley Brothers. Every time they sang the syllable in their performances of “Twist and Shout” and shook their heads, their audiences screamed. John Lennon and Paul McCartney knew a good thing when they heard it and copy it they did. Critics knew that what they heard was a hit, but were unsure what it meant.

Record Retailer was right about the hysteria and by now the band was touring constantly while continuing their juggernaut of near daily appearances on radio and television shows, including a third appearance on Thank Your Lucky Stars to promote the record. Having taped this show on Easter Sunday (14 April) in Teddington and finding themselves on the south side of the Thames, they took the opportunity to hear a band that impresario Georgio Gomelsky had recommended to Brian Epstein. When they entered the “Crawdaddy Club” (a room rented by Gomelsky) they encountered a band that he unofficially managed: the Rolling Stones. The Stones certainly knew who the Beatles were and the Beatles were impressed with what they heard, inviting the London band to be their guests when they appeared at the Royal Albert Hall later the same week. After that show, as some of the Stones helped Mal Evans load the Beatles van, a group of shrieking girls surrounded them, thinking they were the soon-to-be Fab Four. Although the girls were disappointed, Brian Jones of the Stones knew immediately what he wanted.

On Sunday 21 April, the New Musical Express held their annual “Poll-Winners All-Star Concert” which featured the performers who had gathered the most points in categories such as “Best Male Vocalist” and “Best Instrumental Group.” Recognizing (or perhaps fearing) a sea change in British pop music, the NME added four acts that had not been on the ballot to a program that featured perennial winners Cliff Richard and the Shadows. The Beatles, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Mark Wynter, and Mike Berry joined the roster of acts; but everyone knew who stole the show. A sea change was growing into a tidal wave.

Gordon R. Thompson is Professor of Music at Skidmore College. His book, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out, offers an insider’s view of the British pop-music recording industry. Check out Gordon Thompson’s posts on The Beatles and other music here.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image courtesy of Gordon Thompson.

The post From Me (the Beatles) to You (the Stones): April 1963 appeared first on OUPblog.

The other Salem witch trials

The history of American witchcraft is indelibly associated with Salem, Massachusetts, where in 1692 nineteen people were executed as witches after the accusations of two young girls sparked a wave of fear. The village of Salem, the centre of the events of 1692, is now the town of Danvers, with the focus of today’s witchcraft industry centred on Salem city. But there are numerous other Salems in America, born of the country’s religious heritage – Salem in Hebraic means “peace”. But forget colonial Salem for a moment, as on two occasions in America’s more recent past Salem was the scene of trials related to witchcraft.

Salem 1878. In May 1878 the Supreme Judicial Court at Salem, Massachusetts, considered:

That the said Daniel H. Spofford of Newburyport is a mesmerist, and practices the art of mesmerism, and that by his power and influence he is capable of injuring the persons and property and social relations of others, and does by said means so injure them. That the said Daniel H. Spofford has at divers times and places since the year 1875 wrongfully, maliciously and with the intent to injure the plaintiff, caused the plaintiff by means of his said power and art great suffering of body, severe spinal pains and neuralgia, and temporary suspension of mind.

The charge reads remarkably like the indictments for witchcraft two centuries earlier, and the trial’s location further underscored the association in the minds of commentators.

Profoundly influenced by both mesmerism and spiritualism in her early adult life, the founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910), conceived a source of spiritual harm that came to be known as “malicious animal magnetism” or “MAM”. This was the malign use of willpower, the projection of harmful thoughts to cause physical damage. MAM become something of a preoccupation amongst early members of the movement.

In 1870 Daniel Spofford and his wife had entered into an agreement with Eddy that she would teach them the healing art for the sum of $100 cash and ten per cent of the commercial income from their future Christian Science healing practice. The Spoffords fell out with Eddy over other matters and declined to pay the tithe. So in 1878 Eddy launched a lawsuit against them. It was one of several legal actions that the litigious Eddy instigated against former followers at the time.

Things got worse for Spofford when, as this case was pending, Lucretia Brown, a 48-year-old spinster who lived with her mother and sister in one of the oldest houses in Ipswich, lodged a suit against Spofford that Lucretia had suffered a spinal injury as a child, but while an invalid she was able to run a crocheting agency, employing local women working for pin money. An erstwhile Congregationalist, she was converted to Christian Science in 1876 after successful treatment by a female Christian Science healer from the town of Lynn named Dr Dorcas Rawson, herself a former Methodist. Lucretia was rejuvenated and was able to walk for miles for the first time since childhood, but she had a relapse following several visits by Spofford. She consulted Dorcas again who diagnosed that Spofford had been using mesmerism against her. And so Lucretia decided to take legal action, with some subsequently suggesting that Eddy put her up to it. The case was dismissed.

“The Long Lost Friend” was one of the most widely consulted books on how to deal with witches and witchcraft in nineteenth- and twentieth-century America.

Salem 1893. The town of Salem, Columbiana County, Ohio, was a thriving settlement founded by the Quakers. Its inhabitants numbered over 6,000 by the end of the nineteenth century, at which time it was described by one observer as displaying “order, prosperity, thrift, and comfort”. But in 1893 the peace after which the town was named was shattered by a virulent witchcraft dispute.

A few miles south of Salem, at a place known as McCracken Corner, lived a farmer named Jacob Culp. Born in Germany around 1839, he and his family emigrated to America when he was a boy. By 1860 the young man had taken up farming and married Hannah Loop, a Pennsylvanian woman fifteen years his senior, becoming step father to two children from her previous marriage. Culp worked hard and became one of the most prosperous members of the community. Sometime during the 1870s Hannah’s mother Mary Loop and her disabled brother Ephraim moved in to the Culp’s home for a few years. When Mary died, some neighbours, including a couple of the Loop sisters, cast accusing glances at Jacob. When Hannah also died sometime around 1887 and Jacob married Hattie, a woman twenty-five years younger, rumour had it he had bumped Hannah off too by his witchcraft.

The principal rumour-monger was Culp’s sister-in-law, Sadie Loop. Sadie was a key member of Hart Methodist Church, having served it as a Sunday School teacher and sexton. In November 1892, following further family misfortunes and illnesses, which no doctor could help, Sadie decided to call upon a herb doctress named Louise Burns. She told Sadie that she had a very bad brother-in-law, and when she was asked which one, Burns replied “the one that came across the ocean.” This could only be Jacob.

Sadie told a farmer and church Class Leader named Homer B. Shelton of her suspicions. He subsequently made a formal complaint about Sadie:

The undersigned a member of the Methodist Episcopal church, complains to you that Sadie Loop, a member of the same church, has been guilty of immoral conduct, and she is hereby charged therewith as follows: Charge, falsehood.

Specification 1. The said Sadie Loop on or about the 27th day of April, 1893, did utter and publish, contrary to the word of God and the discipline, the following false and evil matter of and concerning Jacob Culp, to wit that he, meaning the said Jacob Culp was a wizard and practiced witchcraft.

H.B. Shelton

A church trial was held in the classroom of Salem Methodist Church. The presiding Judge, Rev. Smith, concluded after hearing all the evidence that he had no alternative but to expel Sadie Loop from the membership of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Hart Church never recovered from these traumatic events. Today it is marked only by a small graveyard along Route 45 a few miles south of Salem.

These nineteenth-century Salem witch trials are a reminder that, two hundred years after the last legal executions for witchcraft in the USA, accusations of witchcraft and malign occult influence could still shake communities to their core, revealing that fear of witchery was as much a part of modern American life as it was in the colonial days.

Owen Davies is Professor of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire and has written extensively on the subject of magic. His new book America Bewitched: The Story of Witchcraft after Salem is the first full history of witchcraft in modern America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: From John George Hohman’s The Long Lost Friend: A Collection of Mysterious and Invaluable Arts & Remedies (Harrisburg, 1856). Image provided by Dr Owen Davies. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post The other Salem witch trials appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2013

Remembering Roger Ebert

The legendary film critic Roger Ebert passed away last Thursday at the age of 70, after a recurrence of cancer.

Ebert’s career in journalism spanned almost six decades, beginning when he was named the first movie reviewer for the Chicago Sun-Times in 1967. By 1975 he was a nationally recognized critic and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize. He also co-hosted a long-running television program–known first, in 1975, as Opening Soon at a Theater Near You, then Sneak Previews, then Siskel and Ebert At the Movies–that introduced him to a much broader audience and confirmed his status as one of the most celebrated American film critics, a distinction he shared with his on-air partner, Gene Siskel, Pauline Kael, and a handful of others. Much as he adapted the craft of criticism to television, Ebert later embraced Internet publishing, blogs, Twitter, and the younger generation of readers who encountered his reviews through digital and social media. Although his health had deteriorated in recent years, Ebert’s final blog post emphasized he had published more articles in 2012 than in any previous year (a total of 306 reviews, along with multiple blog posts and other essays each week).

Ebert was famous (and infamous) for subjecting trashy movies to the trash talk they deserved, and he later published a collection of his most negative reviews with the telling title (a quote from Ebert himself): I Hated, Hated, Hated this Movie. Ebert adopted an elevated tone when the film warranted a more complex analysis, though his persona and taste were usually more populist. In the best of his exchanges with Siskel, the critics alternated between one mode of talking about cinema (as entertainment, as popular culture, as commercial exploitation) and the other (as art, as an engagement with profound ideas and social problems visible on the screen). That flexibility is rare in critics focused on any medium and especially cinema, and Ebert’s success was due in large part to his ability and willingness to approach films with a seriousness commensurate with their ambition.

One explanation for the success of his television programs, a success that no show with a similar format has come close to matching, was their combination of entertaining and opinionated film reviews with a glimpse at the odd-couple friendship between Siskel and Ebert.

Anticipating the reality TV craze that began in the 1990s, At the Movies displayed the frequent clashes of cinematic taste and sensibility between two otherwise close friends, and in retrospect it reveals the limitations of subsequent programs that have foregrounded either personalities or content without finding an ideal balance between the two. Siskel and Ebert managed to highlight the best and worst qualities of the films they reviewed while also making the audience care about and identify with the critics (or, perhaps, to identify with one or the other and cherish their rivalry and the thrill of the debate). While some lamented the program’s reduction of criticism to a simple verdict–”thumbs up” or “thumbs down”–the program was not a direct translation of long-form journalism into television but a unique combination of personality-driven reality TV and informed observations about art and culture. That genre has been difficult to revive after Ebert’s retirement from the small screen.

One other legacy worth emphasizing is the dignity Ebert displayed during his struggle against cancer. When surgery on his jaw made it impossible to speak, eat, or drink, Ebert continued to participate in the fullest range of professional activities that his condition would permit. Aside from the frequent reviews and other writing, he founded a film festival and maintained a vigorous schedule of public appearances. Ebert wrote frequently about his battle with cancer and managed the deterioration of his health with a grace that one encounters only in the most profound movies, the films whose images never quite fade away and whose lessons remain with us long after the end.

Roger Ebert

18 June 1942 – 4 April 2013

James Tweedie is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and a member of the Cinema Studies faculty at the University of Washington. He is the author of the upcoming The Age of New Waves: Art Cinema and the Staging of Globalization.

Image credit: PARK CITY, UT – JANUARY 17: (FILE PHOTO) Film critic Roger Ebert is photographed on Main Street during the 2003 Sundance Film Festival on January 17, 2003 in Park City, Utah. Film critic Roger Ebert, 61, will undergo radiation treatment for cancer later this month for a cancerous tumor in Ebert’s salivary gland reported August 6, 2003. (Photo by Frazer Harrison) EdStock, iStockphoto

The post Remembering Roger Ebert appeared first on OUPblog.

Will boys be boys?

Within a year, two recent articles on the origin of the word boy have come to my attention. This is great news. Keeping a talent of such value under a bushel and withholding it from the rest of the world would be unforgivable. Nowadays, if a philological journal does not come as a reward for the membership in a popular society, its circulation is extremely low (seldom beyond a hundred subscribers, most of them being libraries), and I suspect that relatively few of our readers open every volume of Studia Anglica Posnaniensia (SAP, obviously, from Poznań, Poland) and Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics and Semiotic Analysis (IJGLSA, Berkeley, USA). However, I do, and it is my duty to enlighten the non-subscribers.

The publication in SAP by Boris Hlebec is probably a joke. The author derives the English nouns child, boy, and girl from Slavic. Since he is not aware of the many attempts to find the etymology of the words he set out to explain, the joke did not strike me as particularly funny, but I am afraid that someone with an insufficiently developed sense of humor may take the article seriously. The other piece, by Nigel T. Cousins (in IJGLSA), first struck me as another joke, but, as I went on reading, my initial resentment yielded to a good deal of sympathy.

Cousins dug up a fair number of obscure but disconcertingly suggestive words that may shed light on the history of boy. I will skip his references and cite only the most revealing nouns and adjectives. There is French boiel, an old word for “tube”, used obscenely for “the male member.” In the French dictionary, this word, glossed as “tube,” is explained with the help of boyau, which, among other things, means “sausage” and not unexpectedly “penis.” Next, Cousins remarks that bodkin, with its obsolete variant boidekin, may be part of the puzzle. Modern English-speakers remember the word thanks to Hamlet’s bare bodkin. It seems to have a diminutive suffix borrowed from Dutch (perhaps an illusion), but the root is impenetrable. Of course, boy-kin would have suited us better, but then everybody would have guessed that bodkin is a little boy (which it, at first sight, is not). A word meaning “dagger” can certainly acquire the sense “penis,” and here we have more than a conjecture because this transference of the name happened in French: poignard “dagger” is time-honored slang for “male organ.” (The use of poignard in public, in front of women—it was intended as a taunt for a fellow officer who had the habit of walking around with daggers adorning his Caucasian uniform—provoked the fateful duel between the great Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, 1814-1841, and Nikolay Martynov; in Russia, the language of high society and the drawing room was at that time French.)

Venus and Cupid. Lorenzo Lotto. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The unfamiliar English adjective boistous “full of vigor; thick, stiff” is a rather close synonym of boisterous, whose sexual implication comes clearly to the surface in Romeo and Juliet (I, 4: 25-26). Romeo: “Is love a tender thing? It is too rough/ Too rude, too boisterous; and it pricks like thorn.” Mercutio’s response is facetious, and much in it is made of pricking. Then we encounter the forgotten term poy (again of unknown etymology) “a punting pole” and “a float used to keep a sheep’s head above water” (thus, for all intents and purposes, a buoy). Those who read or have ever read Shakespeare aloud will remember that spirit in his verses should often be pronounced as sprit. From a historical point of view, sprit “a small pole or spar” has nothing to do with spirit, but mischievous phonetics resulted in regular ambiguities in Shakespeare’s texts, because sprit merged with spirit and could denote both “an erect penis” and “sperm”; hence the double entendre of the opening line in Sonnet 129: “The expense of spirit in a waste of shame/ Is lust in action.” Poy, it appears, became a synonym of sprit (in addition to being a synonym of buoy) and a near homonym of boy. Very old words are also boyne “to swell,” boine “swelling,” and boysid “swollen.” Boy could also mean “devil.” Cousins emphasizes the fact that devil and penis were often synonymous. Indeed, the image of the Devil turning men into the slaves of their sexual urge was common. Hence hell “vagina” in Elizabethan English and another double entendre in Sonnet 129 (the last two lines): “…yet none knows well/ To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.”

Boy emerged in Middle English with the sense “servant”; “male child” developed later (at least, such is the evidence of the extant texts). The beginning of the story is lost. Not improbably, boy is one of the numerous b- and p-words, from bug and bud to pug and puddle, that have something to do with swelling. Some of them are of unquestionable Germanic descent, others are certainly Romance. Many, whatever their country of origin, seem to be sound-imitative and refer to bursting and noise. It was not unusual for them to arise in Germanic, travel to French, and return “home.” Some were coined in France and came to England from there. Constant travels back and forth often make the question—Germanic or Romance?—almost unanswerable. This is especially true of slang and vulgar language carried from land to land by mercenaries, thieves, prostitutes, and all kinds of riffraff (ragtag and bobtail). The vocabulary of copulation has always been in the forefront of international slang (consider the universal spread of the English F-word, at one time probably borrowed from Low German but now a world celebrity).

Whatever the ultimate source of boy, in English it found itself surrounded by words that could designate “penis.” They probably formed a willing union. One aspect of the problem Cousins did not explore (and it is not clear how one can tackle it) is the frequency of the nouns and adjectives he discussed. It has been known for a long time that similar sounding words interact and influence one another. The path from “servant” to “male child” is not particularly circuitous, but the process may have been accelerated or even triggered by the word’s environment. Although boy will of necessity remain obscure (which is not tantamount to saying “origin unknown”), it will pay off to stop deriving it from some one well-defined word and considering the mission accomplished. Among the fringe benefits of Cousin’s research is the idea that bodkin, about which nobody knows anything definite, may have some connection with the circle of boy. Things bursting, sharp, and swollen surround us in our hunt for the etymology of boy on all sides. The plot thickens, and this is a good thing.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Will boys be boys? appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding the Muslim world

While interest in Islam has grown in recent years—both in the media and in educational institutions—there remains a persistent misunderstanding of the religion’s practices, beliefs, and adherents, who now number over one and half billion people. Addressing this problem is not simply an academic exercise, for the past decade especially has shown that our understanding of Islam can have enormous consequences on foreign and domestic policies, as well as on social relations. The growth of the Muslim community in the West, the continued American involvement in Muslim-majority countries, the burgeoning global economy, and the new opportunities at dialogue presented by the Arab Spring make understanding the Muslim world more important than ever.

Since its launch in 2007, Oxford Islamic Studies Online (OISO) has served as a hub for Oxford University Press (OUP)’s growing list of reference works, translations, and monographs related to the Muslim world. Updated multiple times a year, OISO includes over 5,000 articles, hundreds of maps and images, and a number of chaptered works, primary source documents, timelines, lesson plans, interviews, and editorials that are meant to promote a more informed understanding of Islam.

Oxford recently partnered with the American Library Association and the National Endowment of the Humanities to make OISO a centerpiece of the Muslim Journeys project, a public education initiative run by the two organizations. Muslim Journeys encourages students and scholars to explore the field by utilizing the most authoritative content available. Over 900 libraries, humanities councils, and community colleges applied to participate in the project, which provides a collection of books, films, and other resources to familiarize users with the Islamic world. Participating institutions will also receive a year’s subscription to OISO, which will vastly expand the number of subscribers to the site, giving OUP a unique opportunity to share this acclaimed learning tool with a wider audience.

To help the new subscribers get the most out of their experience, Oxford’s Product Specialists have been holding webinars to introduce users to the content available on OISO (you can see an example of a webinar). In addition, Oxford’s Marketing team has provided users with links to the content on the site that best highlights the core themes of the Muslim Journeys project:

American Stories: an exploration of Muslim communities in the United States, from colonial times to the present.

Connected Histories: a new way of understanding the relationship between the Muslim world and the West, showing the shared intellectual inheritance among the cultures.

Literary Reflections: a survey of the major works of fiction and poetry inspired by Islam.

Pathways of Faith: the spiritual experiences of the Islamic faith, from the stories of Prophet’s life to interpretations of the Qur’an to the mystical poetry of Rumi.

Points of View: personal narratives from the Muslim world, including the popular graphic novel Persepolis and the memoir In the Country of Men.

To highlight the history of American Islam in particular, Oxford has recruited Edward E. Curtis IV, author of Muslims in America (OUP, 2011), to edit a series of articles on topics such as Muslim politics, congregations, religious leaders, family life, and media perceptions in the United States (premiering in the fall of 2013), which will be supported by new primary source documents. Finally, the Muslim Journeys project coincides with a larger effort to revise and expand the content of the site. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World (originally published in 2009), which forms the bulk of OISO’s content, continues to grow with the addition of spinoff titles, such as the Encyclopedia of Islam and Women (Natana DeLong-Bas, editor), the Encyclopedia of Islam and Law (Jonathan Brown, editor), and the Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics (Emad Shahin, editor). The Arab Spring section of the site will continue to provide new essays on the unfolding revolutions taking place in the Middle East. Oxford will also reach out to participating colleges to commission new lesson plans, based on the subscribers’ experiences with the resources of the Muslim Journeys project.

We hope that together, OISO and Muslims Journeys will bring a greater understanding of the Muslim world.

Robert Repino is an Editor in the Reference department of Oxford University Press. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including The African American National Biography (2nd Edition), The Literary Review, The Coachella Review, Hobart, and JMWW. His debut novel is forthcoming from Soho Press in 2014.

Oxford Islamic Studies Online is an authoritative, dynamic resource that brings together the best current scholarship in the field for students, scholars, government officials, community groups, and librarians to foster a more accurate and informed understanding of the Islamic world. Oxford Islamic Studies Online features reference content and commentary by renowned scholars in areas such as global Islamic history, concepts, people, practices, politics, and culture, and is regularly updated as new content is commissioned and approved under the guidance of the Editor in Chief, John L. Esposito.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Understanding the Muslim world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers