Oxford University Press's Blog, page 954

April 20, 2013

Judge Learned Hand’s influence in the practice of law

While Judge Learned Hand never served on the Supreme Court, he is still considered one of the most influential judges in history. Highly regarded as an excellent writer, he corresponded with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Theodore Roosevelt, Walter Lippmann, Felix Frankfurter, Bernard Berenson, and many other prominent political and philosophical thinkers. We spoke with Constance Jordan, editor of Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand, on Hand’s engagement with the issues of the day and his influence on modern law.

How was Learned Hand influential in the practice of law?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How did Learned Hand differ from Justice Felix Frankfurter?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Did Learned Hand ever expect that his correspondences to be published?

Click here to view the embedded video.

How were you inspired to compile his correspondences?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Constance Jordan is Professor of English and Comparative Literature Emerita at Claremont Graduate University. Jordan has published many books and articles on the subject of literature and the law. She is editor of Reason and Imagination: The Selected Letters of Learned Hand and Learned Hand’s granddaughter.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Judge Learned Hand’s influence in the practice of law appeared first on OUPblog.

April 19, 2013

Post-Soviet Chechnya and the Caucasus

When the names and ethnic backgrounds of the two Boston Marathon bombing suspects were released on Friday, 19 April 2013, rumors immediately began flying over Chechnya, its people, and its role in the world. In order to provide some deeper perspective on the region after the fall of the Soviet Union, we present this brief extract from Thomas de Waal’s The Caucasus: An Introduction.

The Soviet legacy is stronger than it seems in the South Caucasus. Many things that people take for granted are a product of the Soviet Union. They include urban lifestyles, mass literacy, and strong secularism. All three countries still live with an authoritarian political culture in which most people expect that the boss or leader will take decisions on their behalf and that civic activism will have no effect. The media is stronger on polemic than fact-based argument. The economies are based on the patron-client networks that formed in Soviet times. Nostalgia for the more innocent times of the 1960s and 1970s still pervades films, books, and Internet debates. An engaging website of the former pupils who attended Class B in School No. 14 in Sukhumi in the early 1980s gathers the reminiscences of people now living in Abkhazia, Tbilisi, Moscow, Siberia, Israel, Ukraine, Israel, and Greece. The sepia photos of the children in red cravats suggest a multiethnic past in a closed world that has gone forever.

Different perceptions of the Soviet past also confuse the already complex relationship between the three newly independent countries and Russia. The end of the Soviet Union in 1991 meant the decoupling of Russia and the South Caucasus after an enforced union that had lasted two hundred years with one small interruption. The rupture was somewhat better managed than in 1918, but independence was again a traumatic experience. Two vital elements of statehood—economic planning and security—had been steered by Moscow, and it took the three republics at least a decade to reconstruct a functioning economy and law enforcement agencies.

In 1991, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia understandably based their legitimacy on the fact that they had been illegally annexed by the Bolsheviks and had the right to recover their independence. Georgia even readopted its 1921 Constitution. However, the Soviet Union had been not so much a Russian project as a multinational hybrid state with a strong Russian flavor. Besides, in 1991 Russia itself became a newly independent state, which raises the question what exactly the three new states in the South Caucasus were becoming independent from. On occasion, the new Russia would provide an answer, especially for Georgians, by behaving in a menacing, neoimperial fashion, but even Vladimir Putin’s Russia is a long way from being the heir to that of Stalin and Alexander I. The Russian Federation is still in the process of constructing a new post-Soviet identity for itself and deciding whether it is the direct heir of the Soviet Union, has been liberated from its captivity, or, in some undefined way, both.

Where Russia goes in its search for a new identity has a strong bearing on its relationship with its neighbors in the South Caucasus. No models from the past are useful: Russia has never had fully independent neighbors before. In 1992, the Russian government coined the phrase “near abroad” as a catchall term for the newly foreign status of the post-Soviet states. The phrase made sense to Russians, but to the other states it was faintly menacing, implying a less than full endorsement of their independence. Russians across the political spectrum have implied as much. In 1992, Andrei Kozyrev, Boris Yeltsin’s supposedly liberal foreign minister, visited Tbilisi; one of his Georgian hosts complained later that Kozyrev had stopped patronizingly outside the front door of the new foreign ministry and said, “So, you’ve already put a sign up.” This kind of attitude exudes an overbearing familiarity that grates on the Georgians. Consider also the fact that the three men who succeeded Kozyrev as Russian foreign minister all had connections with Tbilisi: Yevgeny Primakov grew up in the city, Igor Ivanov had a Georgian mother, and Sergei Lavrov’s father was a Tbilisi Armenian.

Current Russian policy is still overreliant on “hard power” in the South Caucasus. In the age of Putin and Medvedev, it employs as instruments its presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, its military alliance with Armenia, and its gas pipelines to all three countries. Moscow’s use of these tools and aggressive behavior in 2008 summon up some unwelcome ghosts from the past. But the paradoxical result, as in the Soviet era, is that Armenian and Azerbaijani (but no longer Georgian) leaders dutifully visit Moscow to pledge the importance of their alliance but simultaneously work to counterbalance the Russian influence and build up relationships with other international players, such as the European Union and NATO.

Russia has inherited abundant resources of “soft power” in the Caucasus that Europeans or Americans could only dream of, yet it conspicuously fails to use them. As many as two million Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians are working in Russia and sending remittances home—but they are generally regarded as marginal migrant workers rather than a friendly resource. There is also the Russian language, which is still widely spoken and was the lingua franca of the region for at least a century but is in rapid decline, in large part because the Russian government is doing almost nothing to support it. University libraries in Baku, Tbilisi, and Yerevan are full of Russian-language books that a younger generation of students cannot read. In 2002, the director of the cash-strapped public library in Tbilisi said he had received donations of books from all the foreign embassies in the city—except the Russian embassy. As a result of actions like these, the good achievements of the Soviet era are gathering dust, while the Russian imperial legacy looms larger over the region.

Thomas de Waal is a Senior Associate on the Caucasus at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is the author of The Caucasus: An Introduction, Black Garden, and co-author with Carlotta Gall of Chechnya.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Post-Soviet Chechnya and the Caucasus appeared first on OUPblog.

The need for a new first aid training model in a post-9/11 world

Immediately after two bombs rocked Boston Marathon bystanders and runners, medical volunteers, Medical Reserve Corp members, and law enforcement were seen running to aid victims. For those who suffered trauma, it is likely that these heroic and timely interventions saved lives and improved outcomes. Regrettably and realistically, most future terrorist targets will not have the benefit of a relatively large cadre of trained first aid responders who are standing by and ready to treat heat stroke and other running-related maladies. By all reports, Boston had taken adequate steps to meet the potential medical needs of the runners and to protect the public from a terrorist attack. Yet even with a pre-event sweep of the area for explosive devises and extra police presence on site, two explosions occurred.

Boston Marathon explosions. 16 April 2013. Photo by Aaron Tang. Creative Commons License. flickr.com/photos/hahatango/

It is well recognized that soft targets, such as races, outdoor concerts, and shopping malls, are much easier to attack than hard targets with a strong security presence, like airports and athletic events held in stadiums. Events or locales that are frequented by the public and not subject to security checks will always be at high risk. Given the likelihood of an increased volume of natural disasters, technological catastrophes, pandemics, and terrorist events it is time to reconsider our existing first aid training model. At present, non-profit agencies like the American Red Cross and the American Heart Association, routinely offer first aid training to first responders as well as to the general public. However, this approach is no longer enough. A key challenge is the small number of people who are trained to provide both medical and psychological intervention. Further compounding this dilemma is the shortage of trained first responders who can be deployed to assist survivors and communities in rural areas or in communities with limited resources. As a nation we would be better served by using an effective training model commonly implemented in public schools by local fire departments.

Across America, many fire departments provide fire safety training to upper grades in elementary schools. Students are taught basic fire safety that includes, but is not limited to verifying the presence of home smoke alarms, having an escape route, and knowing the steps to take should a fire occur. Because of this approach, we have been largely successful in creating a culture that recognizes and values fire preparedness and safety. Incorporating fire safety training into school curriculum makes sense and is easily justified because relative to other types of disasters, fire emergencies are high base-rate events.

Today most buildings are inspected by fire marshals and equipped with a variety of fire alarms, extinguishers, and sprinklers. Additionally, most communities have dedicated personnel, fire stations, and vehicles that are highly visible and ready to respond to emergencies. In marked contrast, it is likely that few people know the location of their local emergency operation center or disaster shelter, have an emergency plan, or own an adequately stocked to-go kit. Given the challenges in preparing for high impact but low base-rate disasters, it is imperative that we expand the model currently in place for fire safety to include first aid training.

A first aid training program should be incorporated into upper middle school curriculum with yearly recertification required. The proposed model should not be solely limited to medical first aid, but should also include training in psychological and mental health first aid. A basic premise of first aid is that appropriate, early intervention can mitigate functional impairment and reduce the potential for more serious and enduring health problems that require formal treatment. A comprehensive first aid program is critical as most natural and human-caused disasters result in a high incidence of psychological and not physical casualties. Just as medical first aid may save lives or offset more serious medical complications, psychological first aid has the potential to mitigate serious mental health consequences and build resilience. Moreover, delivery of psychological first aid in tandem with medical intervention would not only be feasible but highly desirable.

The proposed first aid training approach is appropriate for many types of crises, suitable for training both professional and laypeople, applicable to a broad range of disaster events, and incorporates evidence informed practices. We believe that adoption of the first aid training model described above would represent significant progress in fulfilling a key element of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006 mandate (PL 109-417). By training all students to use first aid techniques we take an important and much needed step toward preparing our citizenry to respond to all types of disasters.

Lisa Brown and Bruce Bongar are editors of Psychology of Terrorism with Larry E. Beutler, James N. Breckenridge and Philip G. Zimbardo. Lisa M. Brown, Ph.D. is a tenured, Associate Professor in the School of Aging Studies, College of Behavioral and Community Sciences, University of South Florida. Dr. Brown’s clinical and research focus is on aging, health, vulnerable populations, disasters, and long-term care. Since 2004, Dr. Brown has studied the short- and long-term psychosocial reactions and consequences of natural and human-caused disasters. In addition to her scholarly activities, she is also a Medical Reserve Corp volunteer. Bruce Bongar, Ph.D., ABPP, FAPM is the Calvin Professor of Psychology at the Pacific Graduate School of Psychology at Palo Alto University, and Consulting Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine. Dr. Bongar’s main research focus is on suicidal behavior, clinical emergencies, psychology of terrorism, and suicide terrorism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The need for a new first aid training model in a post-9/11 world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press at the BBC Proms 2013

Every year, around mid-April, music lovers await the news that the BBC proms schedule has been announced. We look forward to the old favourites, the new commissions, the excited atmosphere, and some of the best performers in the world. When summer arrives, scores of people—young and old alike—travel to London to visit the Royal Albert Hall and be part of this great British tradition.

Since 1895 the Proms have been running once a year with around 70 concerts per season. One of the great aspects of the Proms is the perfect juxtaposition of old and new repertoire; you could go to a baroque vocal recital, followed by a Wagner opera, and then end with some jazz. This is the magic of the Proms; it is this variety that keeps a loyal audience returning year after year.

As always, a selection of Oxford University Press titles will be performed, and the pieces selected are a microcosm of the Proms calendar as a whole. Prom 16 will include William Walton’s Death of Falstaff and Touch her soft lips, and part from his Henry V suite while excerpts from his Battle of Britain suite will be performed at Prom 65, the ‘Film Music Prom’.

By contrast, there is Gerald Barry’s No other people in the late night Prom 50. Originally performed in 2009 in Dublin, this will be its UK premiere, a contemporary work for a twenty-first century audience.

At this quintessentially British festival, Vaughan Williams is always a popular choice. Prom 71 includes the premiere of a new arrangement by Anthony Payne of Vaughan Williams’ Four Last Songs, a BBC commission, breathing new life into already established repertoire. The Last Night of the Proms, one of the most exciting evenings in classical music, will feature Nigel Kennedy playing the sublime Lark Ascending, arguably one of the most loved pieces of repertoire in Britain.

To get you in the mood, here’s a playlist of some of the pieces that we’re looking forward to hearing:

Lucy Allen is the Print and Web Marketing Assistant in Sheet Music at Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Oxford Sheet Music is distributed in the USA by Peters Edition

The post Oxford University Press at the BBC Proms 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey

15 April 2013 marked the fifth Jackie Robinson Day, commemorating the 66th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, an event which broke baseball’s racial barrier. In each game that is now played on 15 April, all players wear Jackie Robinson’s iconic #42 (also the title of a new film on Robinson). Thirty years ago, historian and ardent baseball fan Jules Tygiel proposed the first scholarly study of integration in baseball, shepherded by esteemed Oxford editor, Sheldon Meyer. was first published in 1983, and its 25th Anniversary was celebrated with a new edition in 2008. Though Dr. Tygiel passed away in 2008, this extract from his Afterword demonstrates our ongoing captivation with the Jackie Robinson story.

One of the more surprising elements of the recent lionization of Jackie Robinson has been the relative diminution of Branch Rickey in the saga. In the early retellings of the story, Rickey, not Robinson, played the dominant role. The flamboyant and publicity-savvy Dodger president, after all, had set the project in motion, bucking not just history but a hostile group of fellow owners. Rickey had scouted the Negro Leagues and Caribbean baseball, discovered and selected Robinson, and meticulously planned the strategies necessary to make his “great experiment” a success. Rickey had also, in many respects, shaped the prevailing master narrative of the path to integration: his dramatic 1945 meeting with Robinson; the restrictions placed on Robinson’s behavior; the suppression of the 1947 player revolt; and the 1949 liberation of Robinson allowing him to strike back at his tormentors. Although commentators constantly debated and questioned Rickey’s true motivations, in many accounts Robinson appeared as a puppet, with Rickey pulling the strings.

The image of a white, paternalistic Rickey masterminding the integration process and in Lincolnesque fashion emancipating black ballplayers fit well with the postwar liberal ethos. The rise of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the 1950s and 1960s, however, called for a Robinson who was less a martyr to a cause and more an active agent of change. I attempted to present the two more as partners in the endeavor, but as the story unfolded, it was Robinson, the dynamic, compelling man on the field who seized center stage, while Rickey, who left the Dodgers after the 1950 season, faded into the background.

Jackie Robinson swinging a bat in Dodgers uniform, 1954. Photo by Bob Sandberg. Published in LOOK, v. 19, no. 4, 1955 Feb. 22, p. 78.United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division.

Current literature reveals a similar trend. While studies of Robinson proliferate, volumes on Rickey, who even without the Robinson story would still be the most significant baseball executive of the twentieth century, have been rare. Murray Polner’s Branch Rickey: A Biography appeared at about the same time as Baseball’s Great Experiment. Not until 2007, when Lee Lowenfish’s authoritative Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman was published, did another Rickey biography appear. Lowenfish reminds us of the strong religious underpinnings for Rickey’s actions. He criticizes those who question Rickey’s motives as guilty of “erroneous simplification,” arguing that “by ridiculing Rickey’s pontificating style, the impatient ideologues have ignored his moral substance and the genuine paternal relationship he built with Robinson the athlete and family man.” But Lowenfish does not substantially revise the standard long-accepted storyline presented in Baseball’s Great Experiment and other works.

Several historians, however, have contributed a handful of additional insights into Rickey’s thinking that alter my original portrayal. John Thorn discovered a cache of photographs of Robinson taken by a Look photographer in 1945. This led John and me to revisit several documents in the Arthur Mann Papers and to conclude that Rickey’s original idea was not to announce the signing of just Robinson in October 1945 but several Negro League players at once. Political pressures forced Rickey to abandon this strategy and focused attention on Robinson alone as the standard-bearer of the campaign. Neil Lanctot has also shattered the longstanding myth that the United States League (USL), a new Negro League that took the field in 1945, was created largely as a smokescreen for Rickey’s integration initiative. Rickey, he shows, played a minimal role in the conception or operations of the USL. In a review of Baseball’s Great Experiment, Ron Story suggested that my analysis of Rickey’s actions had underplayed his lifelong pursuit of cheap labor, as embodied in his creation of the farm system, in analyzing his decision to sign black players. Following this lead, I addressed this aspect of Rickey’s career in a chapter in Past Time: Baseball As History, published in 2000.

If Rickey, however, has inspired relatively little new research, Robinson remains a popular subject. Thanks to several biographical studies, most notably, Arnold Rampersad’s magisterial Jackie Robinson: A Life, we have a more fully developed portrait of Robinson’s upbringing and his often controversial postbaseball experiences as businessman, civil rights leader, and political activist. Family memoirs by his wife, Rachel, and daughter, Sharon, have, along with Rampersad’s book, also offered a deeper perspective into Robinson’s personal life. In the quest for fresh things to say about Robinson’s baseball career, historians and journalists have begun to deconstruct it in minute detail. Thus we now have books focusing on Robinson’s first spring training in Florida in 1946 and his 1947 rookie season. Can studies of his 1949 Most Valuable Player year or his personal role in the 1951 heartbreak (both of which could actually be wonderful reads) be far behind?

Jules Tygiel, a native of Brooklyn, was Professor of History at San Francisco State University and founder of the Pacific Ghost League. He is the author of and The Great Los Angeles Swindle: Oil, Stocks, and Scandal During the Roaring Twenties. In this gripping account of one of the most important steps in the history of American desegregation, Jules Tygiel tells the story of Jackie Robinson’s crossing of baseball’s color line. Examining the social and historical context of Robinson’s introduction into white organized baseball, both on and off the field, Tygiel also tells the often neglected stories of other African-American players–such as Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron–who helped transform our national pastime into an integrated game.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sports articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey appeared first on OUPblog.

A day in the life of a London marathon runner

Pull on your lycra, tie up your shoelaces, pin your number on your vest, and join us as we run the Virgin London Marathon in blog form. While police and security have been stepping up after Boston, we have been trawling Oxford University Press’s online resources in order to bring you 26 miles and 375 yards of marathon goodness. Get ready to take your place on the starting line.

The reason that you’re about to run a heart-bursting 26 miles is the Greek legend of Phidippides, a soldier and messenger who ran from the Battle of Marathon to relay news of the Athenian triumph over the more numerous and powerful Persians. After he had passed on the message, Phidippides collapsed and died of exhaustion. In order to avoid the same sticky demise as Phidippides, it’s best that you do some running in preparation for your big day.

It’s not just about physical preparation though. You may have done exercises that grouped together would rival Sylvester Stallone in Rocky, but you need to be mentally strong too. Segmenting is a technique athletes use in order to make a long event less overwhelming. They might break a marathon up into mile-long segments, or set a goal for a certain part of the course, rather than think of the marathon in its entirety. This might have been useful for Jo Brand who said in 2005: “I’ve set myself a target. I’m going for less than eleven-and-a-half days.”

Eat healthy

Are carbs your best friend? No? Well it’s best to get acquainted and fast! Carbohydrate loading is a procedure followed by some athletes to raise the glycogen content of skeletal muscle artificially by following a special diet, usually combined with a special exercise regime. For a marathon runner, the procedure starts seven days before a race when the athlete depletes the muscle of glycogen by running a long distance, usually about 32 km (20 miles). For the next three days, the athlete eats a high protein, low carbohydrate diet, and continues exercising to ensure glycogen depletion and sensitization of the physiological processes that manufacture and store glycogen. For the final three days before the race, the athlete eats a high carbohydrate diet, and takes little or no exercise.

On the starting line

It is thanks to Christopher Brasher and John Disley that there is a starting line at all, as the pair organised the first London marathon in 1981 after running the New York marathon together in 1979. As Chris Brasher’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography explains:

“He was impressed with the scale of the race, and with the fact that it welcomed runners of all abilities, ages, and backgrounds, thus diluting the marathon’s élite sporting reputation and making it a civic, multicultural occasion. Returning to London, he wondered in his column in The Observer ‘whether London could stage such a festival.’”

London certainly could stage such a festival, and in 1981 thousands of people lined London’s streets to watch 6,255 runners finish the race. Since then the marathon has grown dramatically, with hundreds of thousands of people expected to watch over 35,000 runners take part in the race this year.

Now it’s your turn. You’re on the line and your knees are shaking. It’s time to channel the past greats of Marathon running to gain some much needed inspiration. Violet Piercy was a symbol of strength between 1926 and 1938 as the first British female long-distance runner. She ran long distances “to prove that a woman’s stamina can be just as remarkable as a man’s,” (South London Press, 2 April 1935), and is often credited as the inspirational figure behind modern female long-distance runners.

Or maybe it’s the modern greats of running that you need to draw inspiration from to stop your shaking legs? Almost as if they are acting on their own accord, your hands rise above your head and form a tea-pot-esque symbol. People are giving you strange looks but you don’t care, you’re doing the “Mo-bot” as you try to draw strength from British Olympic hero Mo Farah.

Running the marathon

London is a beautiful place to run and the many historical landmarks around the city punctuate your brave endeavour, providing some respite to that painful burning sensation in your legs. It’s akin to a touristy bus tour of London — without the bus — and you pass buildings such as Sir Christopher Wren’s St Paul’s Cathedral, as well as 10 Downing Street — home of Prime Minister David Cameron — and 30 St Mary’s Axe (also commonly referred to as the ‘Gherkin’), designed by the architect Norman Foster.

It’s not just the buildings that you should be paying attention to as you run. If you’re really fast, then you’ll be jostling for position with Paula Radcliffe, winner of the Women’s London Marathon in 2002, or Baroness Grey-Thompson, winner of the Women’s Paralympic London Marathon in 1992, 1994, 1996, 1998, 2001, and 2002. However, it’s more likely you’ll be rubbing shoulders with a number of the ‘Mass Start’ celebrities who frequently run the London Marathon such as the former Lord Mayor of London Nicholas Anstee, the cricket legend Sir Ian Botham, and the explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes.

Nearing the end

But you’re not finished yet! You’ve heard rumours but didn’t believe it could be true; the mythical beast known only as ‘the wall’. It normally affects runners around the 20 mile mark but when Jade Goody ran the Virgin London Marathon in 2006, it hit her around the 10 mile mark, and she subsequently dropped out. But it’s not just ‘the wall’ that affects marathon runners. You need to take on water as you go around the course but did you know you can actually drink too much water? A condition known as hyponatremia affects runners who lose salt through sweat but drink too much water to counteract this. Assuming you’ve drunk the right amount of water, you turn the corner past Buckingham palace, you lift a weary hand to wave at the Queen, and take the last few steps to the finish line…

After the race

You’ve done it! You’ve completed the London Marathon and finished in first place. Now you can kick off those running shoes and relax. But wait! A man in a white coat and a clipboard is approaching you. You don’t have the option of running away as muscles that you didn’t even know existed are cramping up. He takes you into a separate room and conducts a doping test. Apparently, setting a world record when you’re a ‘Mass Starter’ is a little bit odd. Don’t worry, you weren’t to know. After serious interrogation, you’re found not-guilty of doping and are free to pick up your medal. Looks like you won’t be appearing in Chris Cooper’s Run, Swim, Throw, Cheat after all.

You can find more about the online resources mentioned in this article with these links: Oxford Reference , Oxford Index , ODNB , Who’s Who , Oxford Dictionaries Online , and Oxford Medicine Online .

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. Photo by Martin Addison. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons (2) Mo Farah – Victory Parade. Photo by Bill. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons (3) Wilson Kipsang 2012 London Marathon. Photo by Tom Page. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons

The post A day in the life of a London marathon runner appeared first on OUPblog.

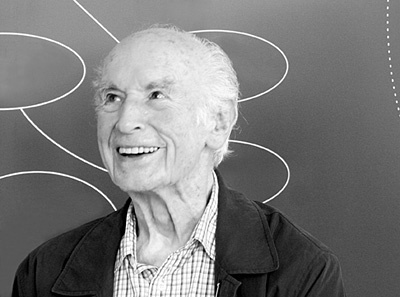

Celebrating Bicycle Day

Albert Hofmann was one of the most important scientists of our time, who through his famous discovery of LSD, crossed the bridge from the world of science into the spiritual realm, transforming social and political culture in his wake. He was both rationalist and mystic, chemist and visionary, and in this duality we find his true spirit.

In boyhood, he had experienced inexplicable, spontaneous transfigurations of nature while walking in the woods, which spurred him to investigate the nature of matter through chemistry. While researching ergot and its potential impact on blood circulation, he accidentally discovered a chemical key that unlocked a pathway to a profoundly altered state of consciousness, offering the potential for great insights into the workings of the mind and the cosmos.

After experiencing its power and its dangers first-hand on his infamous bicycle ride (70 years ago today, on 19 April 1943), Hofmann understood that LSD, if used correctly and with care, could be a vital tool for investigating human consciousness. In later research, he realised that the molecule had virtually the same chemical structure as those in plants used as sacraments for thousands of years by indigenous cultures around the world. He was also the first chemist to isolate the psychoactive compounds of psilocybin and psilocine, found in ‘magic’ mushrooms and the closely connected morning-glory seeds.

Following its discovery, LSD was acclaimed as a wonder-drug in psychiatry, speeding-up and deepening the healing process by accelerating access to psychological trauma. Between 1943 and 1970, it generated almost 10,000 scientific publications, leading to its description as ‘the most intensively researched pharmacological substance ever’.

It also had a broader and more profound effect on how science viewed the mind, changing the dominant view of mental illness from the psychoanalytical model to one understood by brain-chemistry and the role of neurotransmitters. The LSD-experience resembled looking through a microscope and becoming aware of a different reality — a manifest, mystical totality, normally filtered out and hidden from view.

Hofmann realised that a substance with such profound effects on perception was likely to arouse interest beyond the medical field — though he never expected it to find worldwide popularity as a recreational drug. But ‘the more its use as an inebriant was disseminated… the more LSD became a problem child’. These negative developments were not to Albert Hofmann’s liking. He was amazed that LSD had been adopted as the drug of choice by the mass counterculture, but once the genie was out of the bottle, the world could never be the same again.

Albert Hofmann during a discussion “about beauty” at the Zürich Helmhaus. Photo by Stefan Pangritz, Lörrach. Creative Commons License.

Harvard-Professor-turned-Pied-Piper Timothy Leary emerged as a messianic guru. The mass consumption of psychedelics that Leary advocated led to LSD’s prohibition in 1967, to the War on Drugs, and to the complete shutdown of all therapeutic use and scientific research involving the substance.

The legacy of LSD is as controversial as it is profound, and its effects on science, technology, politics, art, and music cannot be overestimated. Many creative pioneers of the era claim to have made their breakthroughs either under the influence of LSD, or as a result of insights gained from it. The IT revolution that grew into Silicon Valley is a prime example of this.

In recent years, despite huge obstacles, the experimental use of LSD is, very cautiously, beginning again. Earlier this year, the Beckley Foundation received the first ever permissions for a brain-imaging study of the effects of LSD on human participants, an undertaking that I promised Albert Hofmann I would carry out.

With other psychedelics, the renaissance in experimentation is well and truly underway. Projects have investigated the neural basis of the effects of psilocybin and MDMA, while other research in the USA and elsewhere has made vital first steps into uncovering the clinical efficacy of these drugs — for example, MDMA’s success as an aid to psychotherapy in treating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The Medical Research Council in the UK recently gave a £550,000 grant to investigate the efficacy of psilocybin in treating depression, marking the first time (as far as we are aware) that a government body has funded psychedelic research. There is thus reason for renewed optimism that, as Albert Hofmann hoped, if people could learn to use LSD more wisely, once again ‘this problem child would become a wonder child’.

Amanda Feilding is the Director of the Beckley Foundation, which studies the effects of psychoactive substances and promotes drug policy reform. She is the co-editor of LSD: My problem child by Albert Hoffman with ethnobotanist Jonathan Ott. The Psychedelic Science Conference 2013 will be held in California 18-23 April.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Bicycle Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Earth Day 2013: dating creation

Monday 22nd April is Earth Day 2013. To celebrate in advance, here’s an extract from The Earth: A Very Short Introduction.

By Martin Redfern

Attempts to calculate the age of the Earth came originally out of theology. It is only comparatively recently that so-called creationists have interpreted the Bible literally and therefore believe that Creation took just seven 24-hour days. St Augustine had argued in his commentary on Genesis that God’s vision is outside time and therefore that each of the days of Creation referred to in the Bible could have lasted a lot longer than 24 hours. Even the much quoted estimate in the 17th century by Irish Archbishop Ussher that the Earth was created in 4004 BC was only intended as a minimum age and was based on carefully researched historical records, notably of the generations of patriarchs and prophets referred to in the Bible.

The first serious attempt to estimate the age of the Earth on geological grounds was made in 1860 by John Phillips. He estimated current rates of sedimentation and the cumulative thickness of all known strata and came up with an age of nearly 96 million years. William Thompson, later Lord Kelvin, followed this with an estimate based on the time it would have taken the Earth to cool from an originally hot molten sphere. Remarkably, the first age he came up with was also very similar at 98 million years, though he later refined it downwards to 40. But such dates were considered too recent by uniformitarianists and by Charles Darwin, whose theory of evolution by natural selection required more time for the origin of species.

By the dawn of the 20th century, it had been realized that additional heat might come from radioactivity inside the Earth and so geological history, based on Kelvin’s idea, could be extended. In the end, however, it was an understanding of radioactivity that led to the increasingly accurate estimates of the age of the Earth that we have today. Many elements exist in different forms, or isotopes, some of which are radioactive. Each radioactive isotope has a characteristic half-life, a time over which half of any given sample of the isotope will have decayed. By itself, that’s not much use unless you know the precise number of atoms you start with. But, by measuring the ratios of different isotopes and their products it is possible to get surprisingly accurate dates. Early in the 20th century, Ernest Rutherford caused a sensation by announcing that a particular sample of a radioactive mineral called pitchblende was 700 million years old, far older than many people thought the Earth to be at that time. Later, Cambridge physicist R. J. Strutt showed, from the accumulation of helium gas from the decay of thorium, that a mineral sample from Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) was more than 2,400 million years old.

Uranium is a useful element for radio dating. It occurs naturally as two isotopes – forms of the same element that differ only in their number of neutrons and hence atomic weight. Uranium-238 decays via various intermediaries into lead-206 with a half-life of 4,510 million years, whilst uranium-235 decays to lead-207 with a 713-million-year lifetime. Analysis of the ratios of all four in rocks, together with the accumulation of helium that comes from the decay process, can give quite accurate ages and was used in 1913 by Arthur Holmes to produce the first good estimate of the ages of the geological periods of the past 600 million years.

The success of radio-dating techniques is due in no small way to the power of the mass spectrometer, an instrument which can virtually sort individual atoms by weight and so give isotope ratios on trace constituents in very small samples. But it is only as good as the assumptions that are made about the half-life, the original abundances of isotopes, and the possible subsequent escape of decay products. The half-life of uranium isotopes makes them good for dating the earliest rocks on Earth. Carbon 14 has a half-life of a mere 5,730 years. In the atmosphere it is constantly replenished by the action of cosmic rays. Once the carbon is taken up by plants and the plants die, the isotope is no longer replenished and the clock starts ticking as the carbon 14 decays. So it is very good for dating wood from archaeological sites, for example. However, it turns out that the amount of carbon 14 in the atmosphere has varied along with cosmic ray activity. It is only because it has been possible to build up an independent chronology by counting the annual growth rings in trees that this came to light and corrections to carbon dating of up to 2,000 years could be made.

Martin Redfern is a former science producer at the BBC Science Radio Unit and author of The Earth: A Very Short Introduction. He is now a freelance science writer.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with Very Short Introductions on Facebook, and OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only environmental and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A composite image of the Western hemisphere of the Earth, by NASA/ GSFC/ NOAA/ USGS [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Earth Day 2013: dating creation appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2013

MMR panic in Swansea and policing

I often think that we learn more from the experiences of those whose lives are different from our own than we do from those who share our experiences. Distance often confers clarity and gives a greater appreciation of context, enabling similarities and differences to become visible. This occurred to me recently as the news of the increasing measles epidemic in Swansea began to grow more alarming. What on earth, you might ask, has this to do with policing? Well, quite a lot.

The origin of this measles epidemic is widely attributed to a controversy that erupted in medicine in the late 1990s. Dr Andrew Wakefield published an article in the Lancet claiming to have found an association between the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine and autism. This initiated a media–hyped panic which prompted parents to become wary of having their children vaccinated. In due course, the panic abated, Dr Wakefield’s claims were investigated and refuted, and the Lancet article was retracted. However, what remained was a pool of unvaccinated children who were growing into adolescence and it is feared that it is the existence of this pool of vulnerable young people that has created the conditions in which the current epidemic has flourished.

On the face of it, this is a catastrophic failure. Dr Wakefield’s research was described as “fraudulent” by the British Medical Journal and the General Medical Council found him guilty of breaches of the code of medical ethics for which he was struck off the Medical Register in 2010. However, was the Lancet to blame for publishing research that turned out to be erroneous? Most definitely not!

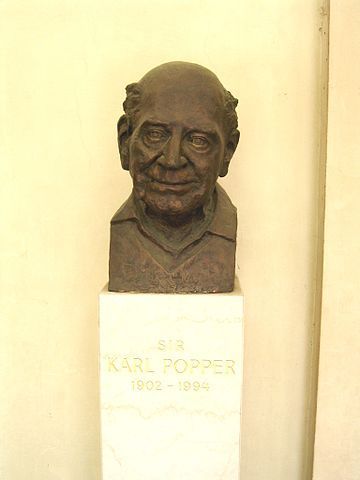

Bust of Sir Karl Raimund Popper, University of Vienna, Austria. Photo by Flor4U. Creative Commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The logic of scientific discovery, as the eminent philosopher of science — Sir Karl Popper — reminds us in his book with that title is one of conjecture and refutation. The whole point of science is that it advances by people making what appear to be wildly counter–intuitive, even outlandish, suggestions that resist all attempts to refute them. The history of science is littered with names now elevated to the status of secular sainthood, whose theories contradicted the verities of their age and disturbed and outraged informed opinion. Ignaz Semmelweishad the effrontery to suggest that patients were dying in hospital because doctors failed to wash their hands before touching them. For this he was hounded out of Vienna and eventually died an ignominious death. Semmelweis was right and his legacy is that device on the hospital wall that invites all visitors to clean their hands with antiseptic before entry. Because a hypothesis is unpopular does not mean that it is wrong.

The genuine problem for medicine is how it can remain open to controversial hypotheses — most of which will be wrong, but occasionally one of them will be correct and spark improvements in health care — whilst avoiding creating needless panic and the disastrous consequences that may continue to be felt decades afterwards.

This too is a problem for evidence-based policing, which is self–consciously, and correctly, modelled on scientific methods. Let us take an example: in good faith forensic scientists a hundred years ago asserted the infallibility of fingerprints as evidence of identification. On that basis, numerous criminals have been convicted and imprisoned; doubtless, some of them were executed. Now, and for some years past, the infallibility of fingerprint evidence has been questioned by, amongst others, Dr Itiel Dror at the University of Southampton Management School.

The grounds for his scepticism lie not in the biology of unique fingerprints, but in the psychological process of deciding whether two prints match, especially when one of them is a partial “latent” print found at the scene of a crime. He has conducted experiments in which forensic scientists are asked to match prints under varying conditions and his results are, to say the least, disturbing. If he is right, should we throw open the prison gates and allow out all those whose convictions rested on fingerprint evidence, especially if some of those are terrorists or serial murderers? Or should the scientific establishment seek to smother Dr Dror’s outrageous conjecture, taking their lead from the physicians of 19th century Vienna? It is a dilemma, just like the dilemma over Dr Wakefield’s hypothesis. Real lives may be at stake.

The criminal justice system is intolerant of error. It erects huge obstacles (the burden and standard of proof) to securing a verdict of “guilty”. When error is detected, scandal ensues, public confidence is damaged, scapegoats are paraded, reviews are initiated and revisions to procedures are made to ensure that no such calamity can be repeated. On the other hand, science thrives on error. It was the inability of Newtonian physics to fully explain the orbit of Mercury that prompted Einstein’s theory of relativity. Geneticists used to think that most DNA was “junk,” but latest developments have shown that, on the contrary, it is essential.

Could the shibboleths of our justice system withstand the scepticism of science? Could it survive in an environment in which truth was only ever asserted provisionally and remained open to refutation? Perhaps, like the physicians of Vienna, we must learn to do things differently. If so, that goes well beyond washing our hands!

Professor P.A.J. Waddington, BSc, MA, PhD is Professor of Social Policy, Director of the History and Governance Research Institute, The University of Wolverhampton. He is a general editor for Policing .

A leading policy and practice publication aimed at senior police officers, policy makers, and academics, Policing contains in-depth comment and critical analysis on a wide range of topics including current ACPO policy, police reform, political and legal developments, training and education, specialist operations, accountability, and human rights.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post MMR panic in Swansea and policing appeared first on OUPblog.

Our treaties, ourselves: the struggle over the Panama Canal

In March 1978, Ada Smith, a fifty-six-year old woman from Memphis, sat down at her typewriter and wrote an angry letter to Tennessee’s Republican Senator Howard Baker. She explained that until recently, she had always been proud of her country, and “its superiority in the world.” But now her pride had turned to fear: “After coming through that great fiasco Vietnam, which cost us billions in dollars and much more in American blood, we are now faced with another act of stupidity, which, in the years to come, could be even more costly. Why should we Americans give up our sons, husbands, and brothers, to fight for land that does not even belong to us, and then sit quietly by, and let you, whom we chose to represent us, give away something as important as the Panama Canal?”

Jimmy Carter and General Omar Torrijos shake hands after signing the Panama Canal Treaty, 7 September 1977. National Archives and Records Administration.

For a brief moment in the late 1970s, thousands of Americans became fixated on a place that most of them had never seen: the Panama Canal. In 1903, the ratification of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty (which took place one hundred and ten years ago last month) had given the United States exclusive jurisdiction over the yet-to-be-constructed Canal and the ten mile wide zone that surrounded it. In the years that followed, the Canal quickly emerged as a potent symbol of American military, economic, and political ascendancy on the world stage. It enabled the traversal of two oceans with one navy, opened trade routes to the global South and East, and constituted a feat of modern engineering. By the 1970s, however, U.S. policymakers had grown convinced that the 1903 treaty was an outdated imperial relic that no longer served the national interest. When he was elected president in 1976, Jimmy Carter placed the negotiation of a new Panama Canal Treaty at the center of a post-Vietnam U.S. foreign policy that would rely less on military force and more on consent, with the aim of restoring the nation’s damaged moral authority in the wake of military defeat. In April 1978, the Carter Administration appeared to get what it wanted: the Senate ratified a new treaty that ensured the gradual assumption by Panama of the management, operation, and control of the Canal.

The famous Culebra Cut of the Panama Canal, 1907.

It is not surprising that Carter’s victory incensed some politicians, who saw no need to “give away” what they believed to be a vital possession. But how do we explain the angry response of citizens like Ada Smith, who lived thousands of miles from the Canal and had no direct familial or economic ties to it? Why did she become so distressed when she thought about the replacement of one treaty with another? More broadly, how do particular places outside of the United States—whether nations, territories, cities, or built environments–become sites of emotional and psychological investment for Americans? As a cultural historian who has studied the increasingly polarized politics of the 1970s, I have long understood why some issues that surfaced during that era—like abortion, women’s rights, and gay liberation—struck such a deep chord that they compelled once apolitical people to engage in New Right grassroots organizing for the first time in their lives. But I was intrigued when I discovered that an ostensibly rarified foreign policy issue could have a similarly galvanizing effect. Yet it had: treaty opponents engaged in letter-writing campaigns, held political rallies, and raised money to buy radio time to air their opposition. And after the new treaty was ratified, conservative voters threatened moderate Republicans who had supported the treaty with political extinction. The threat was not hollow. In the elections of 1978 and 1980, eighteen pro-treaty senators (along with President Carter) went down in defeat. As New Right operative Richard Viguerie explained it, the canal fight had created a “voting map”; conservative voters could go to the polls, look for a pro-treaty candidate’s name on the ballot, and vote against him.

USS Missouri (BB-63) in the Miraflores Locks, Panama Canal, 13 October 1945, while en route from the Pacific to New York City to take part in Navy Day celebrations. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives.

The many letters, pamphlets, and position papers written by its opponents reveal that the treaty served as a proxy for a larger debate about the nation’s global position in the wake of Vietnam. While figures like Carter saw in the treaty a chance for the United States to replace the overt domination associated with empire with a more benign managerial role in its dealings with weaker states, critics perceived the treaties as symptomatic of the paralysis, confusion, and weakness that they believed had gripped policymakers after the failed intervention in Southeast Asia. In other words, they saw in the treaties a larger post-Vietnam pattern of defeatism and surrender, what one anti-treaty critic described as “the cowardly retreat of a tired, toothless paper tiger.” For the many men and women who were carving out a political space for themselves within the burgeoning New Right, this perception of weakness in the foreign policy realm was not unrelated to domestic fights over abortion, feminism, and homosexuality. Indeed, this weakness was seen as an extension of the moral decline they perceived in the realms of heterosexual marriage, gender relations, and the family. Treaty critics routinely portrayed Carter as effeminized and weak and contrasted him to Teddy Roosevelt, the president who had taken control of the Canal in 1903 and who in their view embodied the manliness and fortitude that had now gone missing from U.S. foreign policy.

One hundred and ten years after the signing of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty and thirty five years after the bitter fight over the treaty that replaced it, the struggle over the Canal reminds us that while scholars may draw tidy lines of demarcation between the “foreign” and the “domestic,” citizens themselves inhabit a political universe that is considerably messier, one in which the seemingly distinct worlds of policy-making and private life intersect. Thus when Americans become ideologically invested in a particular place beyond the boundaries of the nation (as they did in the Canal both in the early twentieth century and in the late 1970s), the answer to the question of “why” will almost certainly reside closer to home.

Natasha Zaretsky is an Associate Professor of History at Southern Illinois University. She is the author of “Restraint or Retreat? The Debate over the Panama Canal Treaties and U.S. Nationalism after Vietnam” in Diplomatic History, which is available to read for free for a limited time. She is the author of No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980, which was published by The University of North Carolina Press in 2007. Her writings have also appeared in The New Republic (on-line edition), Diplomatic History, Race, Nation, and Empire in American History (The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), and The World the Sixties Made (Temple University Press, 2003). Along with Mark Lawrence, she is the co-editor of the fourth edition of Major Problems in American History Since 1945 (forthcoming from Cengage-Wadsworth) and is currently working on a cultural history of the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island. In 2009, she was named a Top Young Historian by the History News Network.

As the principal journal devoted to the history of US diplomacy, foreign relations, and security issues, Diplomatic History examines issues from the colonial period to the present in a global and comparative context. The journal offers a variety of perspectives on the economic, strategic, cultural, racial, and ideological aspects of the United States in the world.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Our treaties, ourselves: the struggle over the Panama Canal appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers